Recording transitory factors, such as shocks to commodities prices, variations in housing prices or one-off transactions (e.g. privatisation), affects a country’s fiscal balance; this could give a distorted picture of its underlying fiscal position. Analysing indicators that are not influenced by temporary fluctuations helps policy makers identify the underlying trend of fiscal policies associated with long-term public finance sustainability. The structural fiscal balance aims to capture these trends in order to assess fiscal performance.

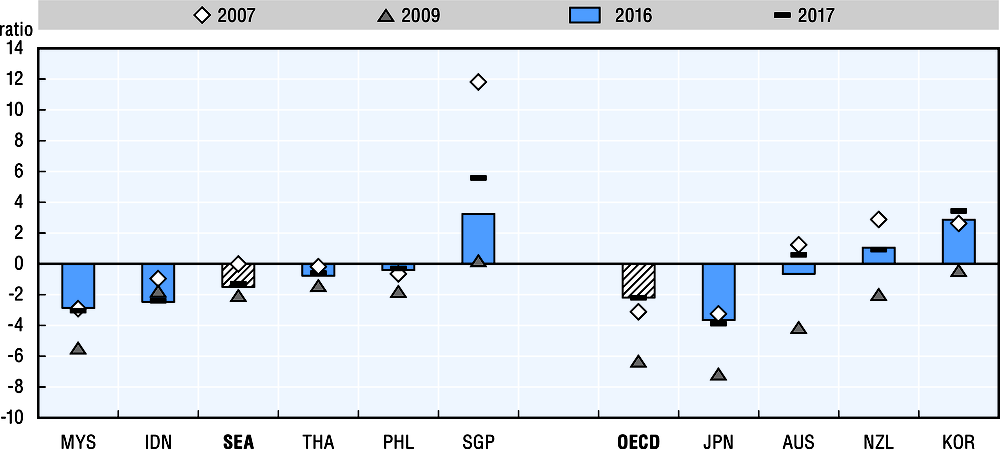

In 2016, SEA countries had an average structural deficit of 1.5% as a share of potential GDP. This decreased to 1.3% in 2017, signalling an overall improvement of the SEA region’s structural fiscal position in those 12 months. Australia and Korea also reported structural fiscal balance improvements. The difference between the average structural (1.5%) and current (1.8%) deficits in SEA signals that recording the current balance reflects the influence of temporary shocks, and explains the subsequent improvement of the structural fiscal position in 2017.

Since 2007, when average structural deficits in SEA countries were almost non-existent (i.e. at 0.01% of GDP), average deficits as a share of potential GDP have increased; Singapore alone has maintained a fiscal surplus. This reflects SEA countries’ public investment spending growing faster than the overall economy. It contrasts with OECD countries, where structural deficits have fallen from 3.1% of potential GDP in 2007 to 2.2% in 2017, after a peak of 6.3% in 2009. In OECD countries, most adjustment came from public spending cuts, including public investment – sinking on average by 0.73 p.p. in 2008-16 (see 2.8 on government investment spending).

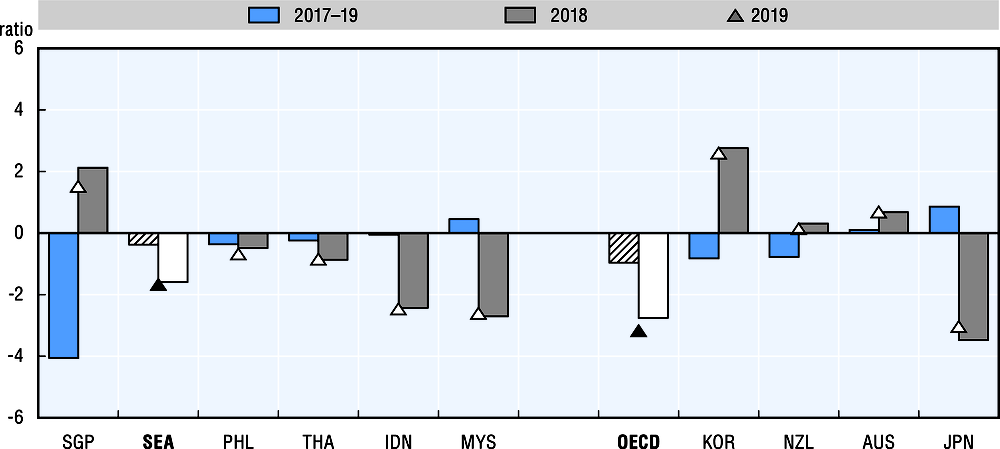

Structural balance projections as a share of GDP in the SEA region show average deficits of 1.6% in 2018, and 1.7% in 2019, as a share of potential GDP. These are less than for OECD countries (2.8% in 2018 and 3.2% in 2019). In 2017-19, structural primary balances are expected to fall in the region by an average of 0.4 p.p. as a share of potential GDP. These projections are based on expectations that in the near term, macroeconomic fundamentals in SEA countries will remain stable as growth remains strong, thanks to robust domestic private spending and planned infrastructure implementation.

However, projected changes vary, from a drop of 4.1 p.p. of potential GDP in Singapore to a rise of 0.5 p.p. in Malaysia. In 2016-17 Malaysia was the only country whose fiscal position worsened slightly, from a structural deficit of 2.9% of GDP up to 3.1%. Despite a commitment to fiscal consolidation, external uncertainties – plus a low revenue base and expenditure needs – challenge the country’s public finance sustainability. This indicates that Malaysia’s fiscal problems are structural and not due to temporary shocks, although the country is planning to improve its structural balance by 0.45 p.p. since 2017. Further prioritisation of short and medium-term expenditures, and more evaluation of programme effectiveness, could help improve Malaysia’s fiscal situation in the near term (OECD, 2016).

These developments imply that continued infrastructure spending is vital to maintain growth, but that good public expenditure decisions are needed to target investments and ensure that other public expenditures yield results.