The last decades have witnessed unprecedented growth in demand for raw materials, driven by the rapid industrialisation of emerging economies and continued high levels of material consumption in developing countries. Current trends of population and economic growth create strong strain on the earth’s natural resource and the environment. This has drawn increasing attention to issues relating to resource efficiency including to waste and material management policies as well as strategies promoting the circular economy. In June 2017, the resource efficiency dialogue was launched by G20 Heads of State and the “5-year Bologna Roadmap” was adopted in the G7 framework to advance common activities on resource efficiency.

Waste Management and the Circular Economy in Selected OECD Countries

Chapter 1. Main findings and conclusions

Abstract

“The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1.1. Introduction

The last decades have witnessed unprecedented growth in demand for raw materials, driven by the rapid industrialisation of emerging economies and continued high levels of material consumption in developing countries. Current trends of population and economic growth create strong strain on the earth’s natural resource and the environment. This has drawn increasing attention to issues relating to resource efficiency including to waste and material management policies as well as strategies promoting the circular economy. In June 2017, the resource efficiency dialogue was launched by G20 Heads of State and the “5-year Bologna Roadmap” was adopted in the G7 framework to advance common activities on resource efficiency.

The OECD has reviewed waste and materials management policy frameworks in 11 countries in the framework of its Environmental Performance Reviews since 2010. The focus countries listed below by the dates of their review benefited from in-depth chapters on waste, materials management and more recently the circular economy.

|

|

This report provides a cross-country review of waste and materials management policies in these focus countries, drawing on the evidence-based assessments of the OECD’s Environmental Performance Reviews. It presents the main achievements along with policy challenges as well as common trends to provide insights into the effectiveness and efficiency of waste management and circular economy policy frameworks. As the reviews were published over seven years, information for some countries may be more recent than others and some information may be outdated. Nevertheless, the policy recommendations emerging from the reviews may provide useful lessons for other OECD and partner countries.

Unless otherwise indicated, all information comes from the Environmental Performance Reviews. The report also considers relevant evidence from the other 13 OECD countries1 that have completed an Environmental Performance Review during the 2010-17 period. Moreover, recent data on waste and materials (and related indicators, such as gross domestic product [GDP]) are provided across all OECD countries where available.

1.2. Overall trends in materials consumption and waste generation

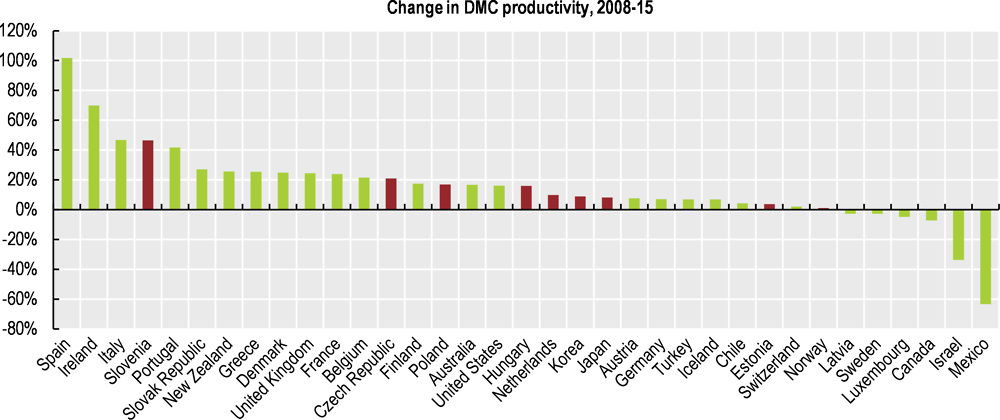

OECD-wide data show several positive trends in waste and materials management (these trends are presented in detail in Chapter 2 of this report). Since 2000, many OECD member countries have experienced improvements in material productivity (Figure 1.1). At the same time, levels of material productivity vary greatly across the OECD, due to differences in economic structures. Moreover, levels and trends in material productivity are influenced by a broad range of factors, including economic cycles, while the data are available for only a relatively short period of time: consequently, the improving trend is difficult to interpret.

Figure 1.1. Material productivity rose in most countries

Note: KOR: 2013 data for DMC productivity, 2010 data for DMC breakdown. Data refer to the indicated year or to the latest available year. They may include provisional figures and estimates. DMC equals the sum of domestic extraction of raw materials used by an economy and their physical trade balance (imports minus exports of raw materials and manufactured products). DMC productivity designates the amount of GDP generated per unit of materials used. GDP at 2010 prices and purchasing power parities. It should be born in mind that the data should be interpreted with caution and that the time series presented here may change in future as work on methodologies for Material Flow accounting progresses.

Source: Eurostat (2016), Material flows and resource productivity (database); OECD (2016), "Material resources", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

Many countries have seen a reduction in the level of municipal solid waste (MSW) generated per capita, and several focus countries decoupled economic growth from the generation of MSW. For a few countries, such as Korea, the Environmental Performance Reviews link these positive trends to specific policy actions. Overall, however, the generation of MSW is closely related to GDP; while a few of the focus countries appear to have decoupled the growth of MSW from that of GDP, it appears that challenges remain in this area.

Many OECD countries have increased the level of MSW recycling and recovery. The Environmental Performance have shown that most of the focus countries put in place policy objectives and instruments to raise their recycling and recovery levels.

1.3. Waste and materials management challenges in focus countries

The Environmental Performance Reviews covered countries with great differences in their economic, social and geographic conditions. These conditions can influence waste and materials management policy objectives, as well as legal and institutional frameworks, together with major policy trends. Box 1.1 below outlines challenges and issues for waste and resource efficiency policy found in the 11 focus countries.

Box 1.1. Waste and materials management challenges

Colombia

Significant challenges arise in the management of hazardous waste from the oil and mining sectors.

Lack of landfill capacity has been a problem, with landfills in some large cities reaching capacity. Plus, the environmental management of landfill sites was a concern: 30% of sites did not comply with standards.

The informal sector plays an important role in waste management, with half of all waste separation for recycling carried out by the sector, creating challenges for government measures to improve recycling rates.

Accession negotiations between the OECD and Colombia began in 2013, encouraging policy changes as OECD recommendations are taken-up.

Czech Republic

During the period up to 2005, the Czech Republic made significant improvements in the legal and policy framework for waste management, aligning legislation with EU requirements and investing in waste treatment facilities. However, co-ordination challenges have hampered further implementation and inconsistent data collection have impeded policy monitoring and waste management planning.

Waste generation rates (primary and municipal) in the Czech Republic are relatively low compared to other OECD countries, with the second lowest rate of MSW generation per capita in the OECD. Despite ongoing investments in recycling, landfilling retained a prominent role in waste treatment.

Construction materials and fossil fuels feature heavily in domestic material consumption (DMC), with construction waste representing around 40% of total waste. While use of fossil fuels, in particular coal, has fallen in recent years, construction material consumption and waste has rebounded since the recession.

Estonia

Accession to the European Union in 2004 has driven policy changes in waste management. Availability of EU funding led to increase in construction and demolition waste. Investments in incineration and mechanical biological treatment (MBT) have led to overcapacity in these waste treatment options.

The prominence of oil shale in Estonia’s energy supply creates significant challenges in terms of material consumption and waste management. Estonia’s material consumption has increased significantly since 2000, and continued reliance on oil shale would make improvements in material productivity challenging.

Most waste is generated by the mining (36.3%) and energy production (32.6%) sectors. 98% of hazardous waste is from oil shale.

Hungary

As in other new European Union Member States, accession to the European Union has led to reforms in waste management policy. Increased investments in infrastructure, particularly in motorways, led to increased consumption of construction materials.

Despite significant decreases in landfilling over the last decade, Hungary has a high rate of landfilling of waste, compared to other OECD EU countries, with 54% of MSW going to landfill in 2015.

Recent changes to the regulatory and institutional frameworks for municipal waste management have created challenges, particularly for municipalities as they seek to adjust to their changing roles in municipal waste management.

Recent industrial accidents and contaminated land discoveries, including the 2010 toxic sludge spill at Kolontár, have drawn public attention to compliance issues in waste management.

Israel

Israel faces significant waste management and resource efficiency challenges. Israel’s per capita waste generation rate is very high compared to the OECD average, and 82% of waste is landfilled. Hazardous waste generation has also grown in recent years.

Landfills are increasingly reaching maximum capacity, and there are challenges in securing new landfill sites due to potential impacts on water resources and local opposition.

There has been significant progress in preventing illegal dumping since the 1980s and 1990s, but remediation of a large number of contaminated sites remains a challenge.

Japan

Despite investments in waste treatment, landfill capacity for non-municipal waste remains a challenge.

These landfill capacity issues initially led to an emphasis on recycling and reducing final disposal, rather than waste prevention (reduction and reuse). However, the policy focus has shifted: reliance on imports of natural resources has brought attention to sustainable material consumption and circular economy goals.

Concerns about dioxin emissions has led to improvements in incineration technologies and past experiences of pollution problems have led to the adoption of a comprehensive legal framework for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB).

The earthquake and tsunami of 2011 created significant challenges in the management of solid waste, with resulting waste exceeding existing treatment and disposal capacity, particularly for radioactive contaminated waste. Large-scale efforts continue to be taken to decontaminate affected sites.

Korea

Korea has enjoyed rapid economic development over the last two decades, leading to growing household consumption and waste generation.

Its ICT and electronics sectors are reliant on external markets for energy and mineral resources. As the OECD’s most densely populated country, securing landfill space is challenging due to local opposition. These factors led to a focus on waste reduction and resource recovery in policy making.

Netherlands

There is an emphasis on incineration with energy recovery in the Netherlands’ waste management portfolio, with overcapacity in incineration.

Limited space in households can discourage waste separation, with lower rates in major cities.

Waste generation and economic growth were reported to be decoupled, based on national data. However, OECD data suggests that waste generation is still very much linked to economic growth. In addition, the 2008 economic crisis may have contributed to success in meeting targets. It may be difficult for the Netherlands to maintain progress during the recovery.

Norway

In the period to 2008, Norway saw considerable growth in household waste generation, due in part to a rising population but also to greater household materials consumption.

Other waste streams also grew in this period, including from some industries (e.g. food processing) as well as construction. Hazardous waste generation also grew, though this was due in part to changes in classification to include, among others, treated wood and asbestos fibre cement waste.

Poland

Recent major reforms to waste policy have been driven, at least in part, by Poland’s accession to the European Union.

Due to its relatively large mining and industrial sectors, Poland has relatively high materials consumption levels. Improvements were observed during 2000‑10, but threaten to be undermined by new construction activities in more recent years

Poland had the lowest per capita municipal waste generation in the OECD in 2014. Reforms to the management of MSW introduced in 2013 have improved service coverage and separate collection, however, provision of MSW services remains a challenge due to implementation challenges during the reform transition.

Slovenia

As in other new EU Member States, accession to the European Union has been the major driver in reforming the waste sector, which was previously poorly regulated. Prior to accession, almost all waste was landfilled or disposed of illegally.

Slovenia was in the process of putting in place the measures needed to support the implementation of EU waste legislation, including data collection systems for material flows and waste.

1.4. Institutional and policy frameworks

The drivers of waste and materials policies have varied across OECD countries. For many European countries, accession to the European Union or the influence of EU policy developments has played an important role. Several OECD countries put in place new measures to tackle problems with illegal waste disposal and shipments, as in Estonia and Spain. The Environmental Performance Reviews have highlighted limits to landfill capacity in countries with high population densities that have stimulated policy action: in Israel, for better waste regulation, in Japan for the circular economy.

Nearly all the countries reviewed had established a comprehensive legal structure for the management of solid waste, together with a process for the development of national waste plans that set out policy objectives and targets, identify actions to meet them and set out a process for monitoring implementation (some countries also developed waste plans at sub-national level).

Many countries demonstrated commitment to circular economy objectives, often expressed in a circular economy policy statement or as part of a broader environmental strategy. OECD countries have used various terms, including resource productivity and sustainable materials management, to refer to circular economy objectives. However, the supporting measures to support the transition to a circular economy have been missing in many cases. Environmental Policy Reviews have identified a wide range of policy instruments that can translate circular economy objectives into concrete action – including economic instruments, green public purchasing, public information and awareness-raising measures, and private sector initiatives, such as voluntary agreements. However, often these instruments are not implemented with circular economy objectives in mind. For example, the Environmental Performance Reviews found that resource taxes can be used to promote greater resource efficiency but are in some countries viewed as a revenue instrument potentially resulting in limitations in how the instrument is designed and implemented.

A key barrier to the implementation of a comprehensive and coherent circular economy policy mix can be the absence of an effective institutional framework. In order to develop and implement policies that support the move to a circular economy, OECD countries should seek to build broad government support and inter-ministerial co‑ordination for effective policies that address all stages of the materials life-cycle. This will address the challenge that action in this sphere goes beyond the remit of environment ministries: several Environmental Performance Reviews called for circular economy strategies or policies to be supported by institutional arrangements co-ordinating the activities of all relevant players, including ministries for economic development, and ensuring that circular economy objectives are integrated across all relevant policy areas. The OECD policy guidance on resource efficiency underlines that where these institutional arrangements are in place, the shift to a circular economy can be treated as a broader economic policy challenge and integrated across sectoral policies.

Only one country reviewed involved the private sector directly in waste management planning, the Netherlands. The extent of private sector involvement in planning and policy stages likely depends on overall public/private relations within a country. Several countries, however, have enlisted private sector co-operation to boost recycling, and a private sector role is likely to increase in the transition to a circular economy.

Most of the review countries use competitive tendering for MSW collection. A key need, seen in many countries, is to ensure adequate government capacity to manage tenders as well as waste management more generally: countries including Poland had programmes to strengthen capacity, notably at municipal level. Where local government have roles in overseeing MSW collection and management, OECD countries should ensure they have the adequate capacity to perform this role. Enabling inter-municipal co-operation can also assist in addressing capacity issues in local governments and help to ensure an efficient scale of management. A growing number of OECD countries have put in place kerbside collection of recyclable waste, and the Environmental Performance Reviews recommended others to do so.

1.5. Policy instruments

OECD countries have put in place a range of policy instruments for waste management. A key factor in their success is ensuring an effective mix appropriate to the policy challenges. For example, Korea addressed food waste, a policy priority, via a landfill ban, a volume‑based waste fee for MSW not going to recycling or composting, voluntary agreements with key sectors such as restaurants and hotels as well as public-private initiatives for awareness raising.

Most of the focus countries have established a comprehensive legal framework for waste management. These frameworks include regulatory instruments that set rules to govern priority waste streams, require authorisation for treatment facilities and standards for their operation according to best available techniques. Landfills bans have been a key regulatory instrument to promote recycling: the EU has established bans for specific waste streams, such as end-of-life tyres and batteries; countries such as the Netherlands have gone further, setting broad-based bans on landfilling.

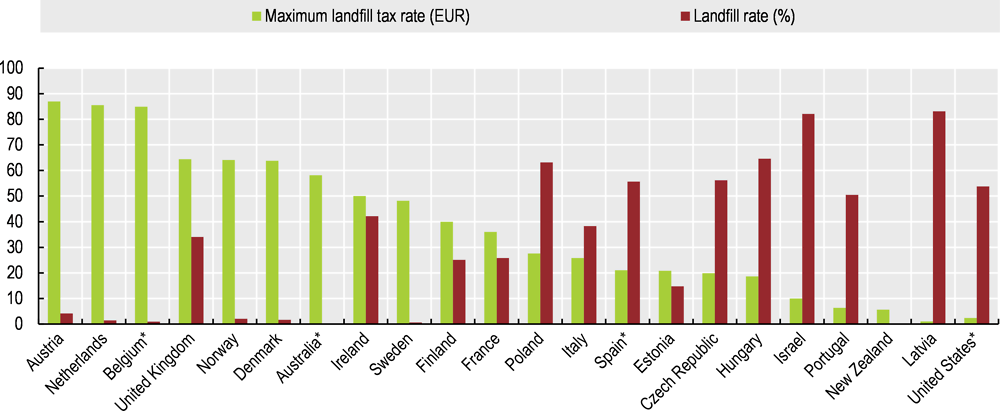

OECD countries have used economic instruments such as landfill and incineration taxes, which have been a key instrument to promote recycling. Ensuring full cost recovery for MSW services remains a challenge in many OECD countries, though this is in place in countries such as Estonia and the Netherlands. A few countries – including the Czech Republic, Korea and the Netherlands – have introduced volume-based pricing for households in at least part of their territories: public acceptance is needed to ensure its effective implementation. Economic instruments are likely to play a growing role in waste management policy in OECD countries. Tariffs should ensure cost recovery for waste management services. The growing use of pay-as-you-throw (or volume-based) pricing for MSW and other waste streams will also be an important element. Taxes on landfilling (Figure 1.2) and incineration can implement the polluter pays principle and encourage greater recycling, but care is needed in designing these taxes to ensure unintended consequences, such as overcapacity in certain treatment methods and weakened incentives for waste reduction are avoided.

Figure 1.2. Countries with high landfill taxes tend to have lower landfill rates

Note: *tax rates refer to Flanders for Belgium, to New South Wales for Australia, to Catalonia for Spain, and to New Jersey, North Carolina, Mississippi and Indiana for the United States.

Source: OECD (2016b), "Municipal waste", OECD Environment Statistics (database); OECD (2017a), "Environmental policy instruments", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

All the focus countries had established extended producer responsibility (EPR), which has been a key mechanism to promote recycling and waste reduction. In the focus countries EPR is particularly used for packaging waste, waste electrical and electronic equipment, and end-of-life batteries, tyres and vehicles. The Environmental Performance Reviews have highlighted the success of these schemes. Challenges in their governance have also been noted in several Environmental Performance Reviews, such as Estonia and Poland. These can include competition issues, achieving full cost recovery through producer fees, gaps in enforcement and in data, and free rider problems: OECD’s 2016 guidance on EPR addressed many of these problems. Where appropriate, OECD countries should consider opportunities for extending this instrument to further waste streams. Countries should also ensure that EPR schemes and producer responsibility organisations (PROs) work effectively and efficiently, by following OECD Guidance as well as the good practices and lessons learned identified in Environmental Performance Reviews.

Several OECD countries – including Korea, Netherlands and Norway – have used green public purchasing as an instrument to promote the use of recycled paper and other products. A further step is to introduce circular procurement, promoting repairable products that can be easily broken down into recyclable components.

Public awareness and support are key factors in changing behaviour and thus can be crucial for the success of waste policies. Communication campaigns need to use high-quality communication methods. In several countries including Colombia and Estonia, non‑governmental organisation (NGOs) have played an important role in organising clean‑up campaigns.

Accurate data is needed to improve the policy base for policy development, implementation and evaluation: several Environmental Performance Reviews identified a need for better data collection and quality assurance. In many countries, data sets are not complete. Inconsistencies in definitions and data collection methods make comparison across countries difficult. Often, data are not consistently recorded over time, with gaps in some years, making it difficult to monitor progress over time. In other cases, data are not available for all relevant indicators. In some countries, these issues have concerned specific sectors, as construction and demolition waste. Korea and Japan have led in the introduction of advanced IT systems for waste tracking. Where necessary, countries should address data gaps for specific waste streams, such as construction and demolition waste, as well as broader data needs.

The move towards the circular economy requires a stronger information base for the circular economy. Policy development is creating new data needs on material flows, to understand how materials are used within a country. Policy implementation needs to be supported by indicators, with material flow information systems in place to monitor progress. Environmental Performance Reviews for the focus countries have highlighted progress in the area: for example, the Netherlands has worked to develop statistics on materials embedded in imports. However, significant gaps remain, particularly in data on international material flows as well as materials consumption embedded in imports and exports. OECD countries should address these gaps by implementing the OECD Council Recommendations on Material Flows and Resource Productivity (2004 and 2008).

The reviews also show that enforcement and compliance promotion remain important challenges, even in OECD countries with advanced waste management. In many of the focus countries, multiple government bodies have roles for enforcement: several Environmental Performance Reviews identified a need for better co-ordination among enforcement bodies. Ensuring adequate capacity is another key step: dedicated bodies for enforcement, investigation and prosecution can play a key role – Norway’s Økokrim unit provides an example of a unit focused on environmental crime prosecution. Several OECD countries, including Korea, Norway and Poland, have established risk-based approaches to focus inspections on the most important facilities and activities. Compliance promotion, to ensure that economic actors are aware of requirements, is also an element in enforcement. Among OECD countries seeking to improve enforcement, key areas for attention include: better co-ordination among enforcement bodies, including police and customs; compliance promotion among key economic actors; the development of risk-based approaches to use enforcement resources efficiently; and adequate capacity to inspect, investigate and prosecute waste-related crimes.

1.6. Investment and financing

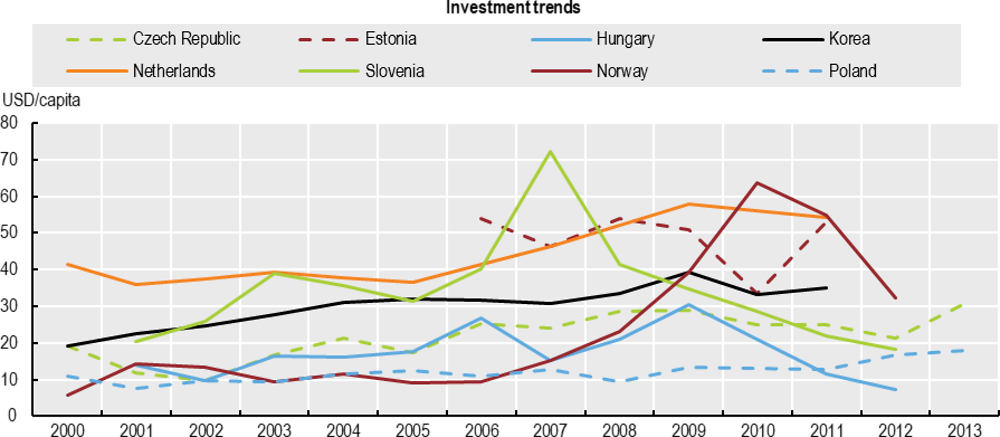

The Environmental Performance Reviews found that OECD countries have mobilised both government and private financing for investment: for many of the focus countries, the level of investment in waste management has increased since 2000 (Figure 1.3). Public financing, including via dedicated environmental funds, has played a key role in supporting waste investments in particular in EU countries such as Hungary and Poland. At the same time, several countries have experienced overcapacity in either incineration or MBT facilities or are at risk of overcapacity in the future. A number of factors may have contributed to these situations, including the promotion of separate collection and recycling, reducing the need for waste incineration and pre-treatment, and infrastructure planning failing to take into account waste treatment facilities in neighbouring countries. New EU Member States have had access to European grant financing, which can create incentives for over-investment, in particular in large facilities. These issues highlight the need for effective waste management planning that establishes appropriate policy mixes. Neighbouring countries, notably in the OECD Europe area, may need to co-ordinate their policies for waste management investments. Countries should follow OECD’s 2006 Council Recommendation on Good Practices for Public Environmental Expenditure Management.

Figure 1.3. Investment in waste management has increased since 2000

Source: OECD (2017), "Environmental protection expenditure and revenues", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

The clean-up of contaminated sites is a challenge in many OECD countries. Clear rules establishing strict liability for the clean-up of past problems are needed. Environmental Performance Reviews identified gaps in the legal frameworks of some focus countries. Another challenge occurs when a liable party goes bankrupt or cannot be identified; some OECD countries have overcome this challenge by establishing a public fund for remediation of contaminated sites. Understanding the nature and extent of contaminated site challenges is valuable in guiding remediation activities; several OECD countries have established a register of contaminated sites to plan remediation investments. Where a country faces a large number of legacy polluted sites, it can be important to prioritise remediation activities based on risk assessment: Norway, for example, identified priority sites for clean-up. Other countries facing a large number of legacy polluted sites should prioritise remediation activities based on health and environmental risks.

1.7. International co-operation

With regard to international instruments on transboundary waste movements, nearly all OECD countries have ratified the Basel Convention, and many have subscribed to its Ban Amendment; however, as yet few have signed or ratified the Liability Protocol. Moreover, as of mid-2017, only four of the 11 focus countries had designated “pre-consented recovery facilities” under the OECD Council Decision concerning the Control of Transboundary Movements of Wastes Destined for Recovery Operations (C(2001)107/FINAL). OECD countries should consider further attention to the ratification and implementation of international instruments.

Several Environmental Performance Reviews found extensive transboundary trade in hazardous and non-hazardous waste streams in the focus countries: trade allows specialised recovery; at the same time, it can arise when domestic waste policy creates inefficiencies, as seen in Estonia’s MSW imports for incineration, where capacity exceeds domestic needs. Countries need to address the dimension of international waste shipments, and the development of waste treatment and disposal sites in trading partners, in their waste management planning. Enforcement efforts need to be adequate to address the risks of illegal shipments.

The Environmental Performance Reviews highlighted initiatives to share knowledge and promote stronger waste and circular economy policies, undertaken for example by Japan and Korea. Countries should consider ways to expand international co-operation for the dissemination of policies and good practices for a circular economy.

References

OECD (2001), OECD Council Decision concerning the Control of Transboundary Movements of Wastes Destined for Recovery Operations, C(2001)107/FINAL, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/C(2001)107/FINAL/en/pdf.

OECD (2010), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Japan 2010, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264087873-en.

OECD (2011 a), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Israel 2011, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264117563-en.

OECD (2011b), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Norway 2011, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264098473-en.

OECD (2012), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Slovenia 2012, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264169265-en.

OECD/ECLAC (2014), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Colombia 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208292-en.

OECD (2015a), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: The Netherlands 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264240056-en.

OECD (2015b), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Poland 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264227385-en.

OECD (2017a), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Korea 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268265-en.

OECD (2017b), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Estonia 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268241-en.

OECD (2018a), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Hungary 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298613-en.

OECD (2018b), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Czech Republic 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264300958-en.

Note

← 1. The other 13 countries, in addition to the 11 whose Environmental Performance Reviews had an in-depth chapter on waste and materials, are: Portugal and the Slovak Republic (2011); Germany (2012); Mexico, Italy and Austria (2013); Iceland and Sweden (2014); Spain (2015); France and Chile (2016); Canada, New Zealand and Switzerland (2017).