Finland’s continuous learning system offers a wide range of learning opportunities for adults at all skill levels. Provision is typically public or quasi-public and comes free of charge or at little cost to the individual. While many adults take part in continuous learning, provision could be better calibrated to help adults keep abreast with the transformations of the labour market. This chapter describes the current structure of the continuous learning provision in Finland, as well as its alignment with the changing skill needs of the labour market. It highlights the key challenges facing the current system and makes recommendations on how to tackle these, based on international evidence.

Continuous Learning in Working Life in Finland

3. Making continuous learning provision fit for the future

Abstract

Introduction

There is no “one size fits all” approach when it comes to optimal adult learning provision. What kind of education and training opportunities should be made available to help adults keep abreast with the changes in the world of work depends on each country’s skill profiles and skill demand. Differences across countries call for tailored, country-specific solutions.

Yet, some basic desirable features of future-ready adult learning provision can be identified for all countries. First, provision should be broad enough to serve participants at all skill levels and should be relevant both to individual needs and to the labour market. Second, provision should be based on good quality and timely information on changing skill needs and dynamically adjusted to respond to these changes. Third, the system should offer learning opportunities that are flexible in modes and time of delivery and compatible with work and family obligations. Finally, for those in work, provision should offer shorter micro-modular learning opportunities to enable truly continuous learning, rather than requiring extended periods away from the labour market to gain a full formal qualification at once.

Finland already has a vast array of learning opportunities that meet many of these criteria, yet there is room for improvement. This chapter discusses the existing structure of adult learning provision in Finland, highlights its key challenges and draws out recommendations based on international good practice.

The current system

Structure of adult learning provision

Adult learning provision in Finland encompasses basic and general education; vocational education; higher education and adult liberal education. With the exception of basic and general education, there is little distinction between adult and youth education. All formal education qualifications are assigned a competence level within the Finnish Qualification Framework (FiNQF).

Basic and general upper secondary education gives adults the opportunity to obtain formal degrees, such as the matriculation examination or completing the lower secondary curriculum (Table 3.1). It also allows adults who have already obtained these formal degrees to re-take individual subjects to improve their grades. Teaching is provided in upper secondary schools for adults (Aikuislukio/ Vuxenutbildning), but adults can also study alongside young people in regular upper secondary schools (Lukio/ Gymnasiet) or folk high schools. Basic qualifications are referenced at Level 2 of the FiNQF, while general upper secondary qualifications are referenced at Level 4 (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2018[1]).

Table 3.1. Types of basic and general adult education provision in Finland

|

Types of provision |

Providers |

Duration |

Costs to participants |

FiNQF level |

Participants (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Basic education qualification (and subject studies) |

Upper Secondary Schools for Adults Vocational Schools Folk High Schools Adult Education Centres |

2‑4 years |

Free of charge; exception are subject studies which can be charged (typically EUR 20‑150 per year) |

Level 2 |

4 160 participants (full qualification) 1 334 participants (subject studies) |

|

General upper secondary qualification (and subject studies) |

Upper Secondary Schools for Adults General Upper Secondary Schools Folk High Schools |

1‑3 years |

Free of charge; exception are subject studies which can be charged (typically EUR 20‑150 per year) |

Level 4 |

6 915 participants (full qualification) 15 924 participants (subject studies) |

Note: Data refers to all participants following the curriculum for adults, irrespective of age (i.e. includes those below 25 years of age).

Source: OECD elaboration, all data Statistics Finland.

Vocational education encompasses a wide range of provision for adult learners (Table 3.2). Since the 2018 VET reform, there is no longer a distinction between youth and adult VET. Every individual follows the same path to access provision. Individuals can obtain initial vocational education (IVET), as well as continuing and specialised vocational qualifications. All qualifications are competence-based, which allows for the recognition of prior skills and knowledge and the development of individual learning paths. There are several forms of provision leading to a qualification:

IVET (ammatillinen perustutkinto / yrkesinriktad grundexamenis) is offered at upper secondary level and aims to equip individuals with the skills necessary to find employment, be a good member of society and pursue further studies. Learners can choose one of 43 vocational upper secondary qualifications. IVET has a typical duration of three years, although length can vary depending on prior skills and knowledge. The qualification is referenced at Level 4 of the FiNQF, at the same level as a general upper secondary degree.1

Further vocational qualifications (ammattitutkinto / yrkesexamina) serve the further development of individuals who are already in the workforce. Individuals typically take part in preparatory training for the competence test in one of 65 further qualifications. Training courses have varying length, but qualifications are awarded to people who can display more advanced or specialist skills than those required in IVET. In contrast to IVET qualifications, preparatory training only conveys vocational and no general skills. The qualification is referenced at Level 4 of the FiNQF.

Specialised vocational qualifications (erikoisammattitutkinto /specialyrkesexamina) are for individuals in working-life who hold highly advanced or multidisciplinary skills (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[2]). Individuals can take-part in preparatory training to take the competence test for one of 56 specialist vocational qualifications. These are referenced at Level 5 of the FiNQF, higher than IVET and further vocational qualifications.

Table 3.2. Types of adult vocational education in Finland

|

Types of provision |

Providers |

Duration |

Costs to participants |

FiNQF level |

Participants (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Initial vocational qualification |

Vocational institutions |

Depending on prior competence (typically 2‑3 years) |

Free of charge |

Level 4 |

84 428 adults |

|

Further vocational qualification |

Vocational institutions |

Depending on prior competence (typically 1‑1.5 years) |

Reasonable fees can be charged (typically < EUR 500) |

Level 4 |

47 551 adults |

|

Specialist vocational qualification |

Vocational institutions |

Depending on prior competence (typically 1‑1.5 years) |

Reasonable fees can be charged (typically < EUR 500) |

Level 5 |

24 758 adults |

|

Non-formal VET/ short-courses |

Vocational institutions |

Flexible |

Reasonable fees can be charged (typically < EUR 500) |

Not assigned |

53 247 participants* |

|

Labour market training |

Vocational institutions Universities, UAS Adult education centres Folk high schools Private providers |

Flexible |

Free of charge |

Not assigned |

Qualifications: 5 418 adults Courses not leading to qualifications: 30 142 participants* |

Note: Number of participants aged 25 and above; *all participants, including adults below the age of 25.

Source: OECD elaboration, all data Vipunen database and Statistics Finland.

In addition to these full qualifications, vocational education encompasses vocational training not leading to a qualification (non-formal). This includes learning in the context of labour market training for the unemployed, staff training ordered by employers, joint-purchase training ordered jointly by employers and the PES, and independent completion of modules or part-qualifications.

In VET, teaching takes place at VET providers run by (groups of) municipalities, state-owned institutions and foundations, which bring together municipalities and private organisations/companies. Providers require an authorisation licence to provide education and training by the MoEC. Provision can be school-based with dedicated blocks of on-the-job learning or delivered in the form of apprenticeship training. Apprenticeship training allows individuals to complete a qualification while working. Apprenticeship training is the more popular training option for adults over 25 years of age (Kumpulainen, 2016[3]).

Higher education institutions are in principle open to all learners, irrespective of age and experience. Exceptions are some Master courses at Universities of Applied Sciences, which require work experience to enter. Higher education institutions include Universities (yliopisto / universitet), of which they are 13 specified in the Universities Act (558/2009) and 23 Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS, ammattikorkeakoulu / yrkeshögskola), which hold an operating license by the MoEC. While education at universities is research-driven, UAS have a strong practice orientation and ties with working life. Work-placements constitute an integral part of UAS studies. A recent law change obliges universities to offer continuing learning opportunities. Adults can take part in higher education in four ways:

1. Entering regular bachelor’s and master’s degree studies, through which adults can take modules or full degree programmes free of charge. UAS in particular see adults as one of their key target groups. In total, 76 000 of adults aged 25 or above were registered in Bachelor and Master courses at Universities and 77 000 at UAS. Half of ‘adult’ Bachelor students at Universities had signed-up for the course before the age of 25, while one in four of ‘adult’ Master students did the same. It is likely that these are ‘initial’ rather than adult learners, although the exact share is difficult to assess.

2. Each University or UAS also runs courses via Open Studies, based on each’s institutions higher education syllabus. The aim of Open Studies is to provide individuals with opportunities to familiarise themselves with higher education, complement prior degrees or obtain new competencies (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[4]). Open Studies do not lead to qualifications, yet constitute parts of higher education degrees and offer an entryway into regular degree studies at Universities, typically after acquiring 60 credits under the European Credit Transfer system (ECTS) depending on the higher education institution. Traditionally the domain of adult learners, the lower age limit of 25 was abolished in the 1990s. This has led to an influx of mostly younger adults below the age of 30, who often participate with the intention to increase their chances of gaining a regular degree study place (Jauhiainen, Nori and Alho-Malmelin, 2007[5]; OECD, 2001[6]). Provision is modular, flexible and can be online. Participation is charged at a maximum of EUR 15 per ECTS credit.

3. Specialisation studies were introduced in 2015, as a new form of non-formal learning opportunities that are developed in cooperation with employers. Their purpose is to provide learning opportunities where there is no market-based offer (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[4]). Courses cover topics such as ‘Big Data Analytics’ or ‘Music Management’. They target working adults who hold a higher education degree or equivalent skill levels. These learning opportunities are longer programmes equivalent to a minimum of 30 ECTS credits. Individuals are charged EUR 120 per credit.

4. In-service training/continuing professional education, which is developed for specific employers and 100% covered through employer contributions.

The resulting qualifications from higher education are categories at Levels 6 (Bachelor’s degrees), 7 (Master’s degrees) and 8 (Doctorate, Licentiate and specialised medical degrees) of the FiNQF (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2018[1]). Open Studies, Specialisation Studies and In-service Training does not lead to qualifications.

Table 3.3. Types of adult higher education in Finland

|

Types of provision |

Providers |

Duration |

Cost to participants |

FiNQF level |

Participants (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

Universities, UAS |

3 years (University) 3.5‑4 years (UAS) |

Free of charge |

Level 6 |

U: 32 359 adults UAS: 64 651 adults |

|

Master’s degree |

Universities, UAS |

2 years (University) 1‑1.5 years (UAS) |

Free of charge |

Level 7 |

U: 43 690 adults UAS: 12 195 adults |

|

Open Studies |

Universities, UAS |

Flexible |

Max. EUR 15 / credit |

Not assigned |

U: 96 582 participants* UAS: 27 928 participants* |

|

Professional specialisation studies |

Universities, UAS |

Flexible, at least 30 ECTS |

Max. EUR 120 / credit |

Not assigned |

U: 5 450 participants* UAS: 1 071 adults |

|

In-service training |

Universities, UAS |

Flexible |

Free of charge, paid by employer |

Not assigned |

n/a |

Note: Number of participants aged 25 and above; *all participants, including adults below the age of 25.

Source: OECD elaboration, all data Vipunen database and Statistics Finland.

Adult Liberal Education has a strong tradition in Finland. The first institutions were founded in the 19th century as grassroots institutions free from governmental control. Since then, the links between these institutions and the government have strengthened, not least through significant amounts of public funding. The landscape of adult liberal education providers is diverse and includes Adult Education Centres (Kansalaisopisto), Folk High School (Kansanopisto), Study Centres (Opintokeskus) and Summer Universities (Kesayliopisto). The courses offered in these institutions are non-formal and typically related to recreation, citizenship and community development, although they increasingly include courses to develop basic and job-related skills for specific target groups. In 2018, Finnish liberal adult education was assigned the role of providing basic and literacy training for migrants. Participation in courses at adult liberal education institutions are recognised in the competence-based VET qualifications and validations of prior learning. Participants pay mostly small course fees, and specific target groups, e.g. migrants, receive training vouchers to participate in learning at adult liberal education institutions. While gross participation numbers in adult liberal education are around 1.5 million per year, it is estimated that the number of unique participants is 900 000.

Table 3.4. Types of adult liberal education in Finland

|

Providers |

Duration |

Cost to participants |

FiNQF level |

Participants (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adult Education Centres |

Flexible |

Small registration and participation fee, depending on municipality Folk high school: Average around EUR 1 500/semester, 3 000/year Summer University: average 65 EUR/credit |

Not assigned |

1 055 486 participants* |

|

Folk High Schools |

104 469 participants* |

|||

|

Summer Universities |

48 801 participants* |

|||

|

Study Centres |

218 112 participants* |

|||

|

Vocational institutes |

41 879 participants* |

Note: *all participants, including adults below the age of 25.

Source: OECD elaboration, all data Vipunen database and Statistics Finland.

Every year, more than 1 million adults in Finland take part in staff training subsidised by their employer, according to data from the Adult Education Survey. 83% of companies with staff of 10 people or more are offering training opportunities, according to CVTS data. Smaller companies are less likely to do so. Staff training is training provided by employers for the development of their employees, some of which overlaps with the public provision mentioned above, e.g. formal and non-formal vocational training, in-service training provided by universities. It can also be provided by in-house trainers or purchased in the open market. Employers are obliged by law to draw up personnel and training plans for their company (Ministry of Labour, 2007[7]; Ministry of the Interior, 2007[8]). In companies with more than 30 employees, this must include principles for the provision of job-related coaching or training (Ministry of Labour, 2007[7]).

A form of staff training specific to the Finnish context is Joint Purchase Training (Yhteishankintakoulutus/ Gemensam anskaffning av utbildning), which is organised jointly by the PES and individual or groups of employers. The MoEE estimates that 3000‑4000 people take part in training organised as joint-purchase training every year. Three types of training are available (OECD, 2017[9]; Eurofound, 2018[10]; OECD, 2019[11]):

Recruitment Training (RekryKoulutus/ RekryteringsUtbildning) is the most popular form of Joint Purchase Training. It is organised with employers who struggle to find employees with the right skills. The PES supports the employer(s) in developing tailored training programmes, selecting a training provider and recruiting participants. Training duration is typically between 3 and 9 months, with a minimum requirement of 10 days, and should lead to a qualification that allows the individual to perform the required job. Training-costs are co‑funded by the PES at a rate of 30%.

Tailored Training (TäsmäKoulutus/ PrecisionsUtbildning) supports employers who want to retrain staff in order to adapt their skills to a changing operational or technological context of the company. The minimum training duration is 10 days, which can take place during time of temporary lay-off. The PES supports the company in selecting the education provider and employees eligible for training. It also co‑funds the training by 50‑70% depending on company size.

Change Training (MuutosKoulutus/ OmställningsUtbildning) is organised in case of staff redundancies and supports workers to transition to new jobs. Training can last between 10 days and two years, with the view of obtaining a (partial) vocational degree. The PES co‑funds 80% of the training costs.

The incoming Rinne government has pledged to increase the number of joint purchased trainings in the 2019‑23 legislative period (Finnish Government, 2019[12]).

Table 3.5. Types of staff training in Finland

|

Types of provision |

Providers |

Duration |

Costs to participants |

FiNQF level |

Participants (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Courses commissioned by employers |

Vocational schools UAS Folk high schools Adult education centres Study circles Summer universities Private providers |

Flexible |

Free of charge |

Not assigned |

143 572 adults* |

|

Joint-purchase training |

Flexible |

Free of charge |

Not assigned |

3 000‑4 000 adults |

Notes: *public provision only, all participants, including adults below the age of 25, excludes provision at sports institutes.

Source: OECD elaboration, all data Vipunen database, data provided by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment.

Responsiveness of provision to labour market needs

In line with the Nordic tradition of adult education, adult learning in Finland aims to promote individual enjoyment and self-development according to individual interests and preferences, alongside developing competences in line with labour market needs (EAEA, 2011[13]).

Today, the vast majority of adults who participate in learning in Finland do so for job-related reasons such as to improve their career prospects or to improve their chances of finding a new job2. Various exercises exist to anticipate the skill needs of the labour market and align education provision with these skill needs.

Box 3.1. Training in the context of Active Labour Market Policies

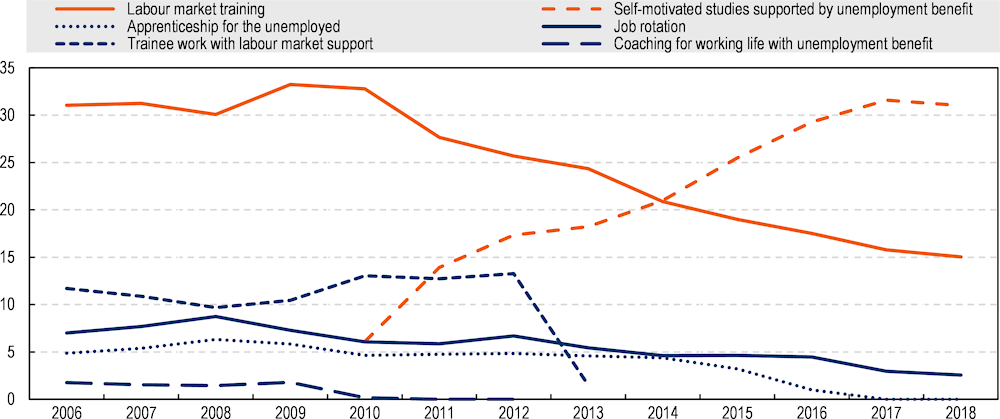

The type of training taken up by job seekers registered with the PES (TE in Finland) has changed considerably over the past decade. In the past, the majority of adults taking part in training-focused Active Labour Market policies (ALMPs) participated in labour market training (Figure 3.1). Labour market training encompasses a range of training such as vocational short courses; standard initial, further or specialist vocational qualifications; vocational qualification modules; and entrepreneurship training. Employment and Economic Development Offices purchase the training from education providers and companies. Participation is free for the individual.

Since its introduction in 2009, self-motivated studies have become an increasingly popular option for job seekers (Figure 3.1). Self-motivated studies allow job seekers above the age of 25 to pursue a degree at a regular education institution full-time, while they continue to receive unemployment benefits. Job seekers can take-up self-motivated studies if the TE office agrees on the need and relevance of the training to improve job seekers’ skills and employability. The unemployment benefit itself is paid by the Social Insurance Institution KELA or an unemployment fund.

These changes have led to an increased use of the regular adult learning system for training in the context of ALMPs. It implies a decrease in central control exerted by the Public Employment Services concerning the types of training that are made available to job seekers. In turn, individual caseworkers now make decisions on the admission to self-motivated studies on a case-by-case basis.

In recent years, both labour market training and self-motivated studies have increasingly been taken-up by migrants in the context of integration training.

Figure 3.1. Self-motivated studies are now dominating the ALMP training offer

Note: Data refers to participants, not new entrants to ALMP training. It should be noted that self-motivated studies are typically of longer duration than labour market training and can stretch over several years.

Source: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment.

Anticipating the skill needs of the labour market

Finland has a long tradition of anticipating the skill needs of the labour market to inform policy-making and has been generating quantitative skill forecasts since the 1950s (Berge, Berg and Holm, 2015[14]). A great wealth of anticipation tools and processes are employed throughout the country, focusing on different governance levels, using different methods and time-horizons (OECD, 2016[15]). The system has been criticised for being too fragmented in the past, although recent efforts have aimed to streamline some of the anticipation exercises (Arnkill, 2010[16]).

The National Foresight Network brings together public and private actors involved in the anticipation of the key challenges and opportunities Finland is facing. It is run by the Prime Minister’s Office and Sitra, the Finnish Innovation Fund (Nyyssölä, 2019[17]). Participants include regional councils, agencies, universities, researchers, companies, NGOS, as well as a range of different ministries, including the MOF, MoEE, MoEC and MHSA. These four ministries also finance the long-term structural forecast exercise conducted by the Government Institute for Economic research (VATT) using the VATTAGE general equilibrium model of the Finnish economy (Honkatukia, 2009[18]). Ministries use the results of this exercise as input to their own anticipation exercises.

At a national level, the Finnish National Agency of Education (EDUFIN), a subsidiary of the MoEC, uses the VATT structural forecast as basis of their education and skill anticipation exercise. The anticipation process is currently in transition, as it consolidates the previously separate qualitative (VOSE-model) and quantitative anticipation exercises (Mitenna-model) into one single ‘basic anticipation process’ (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. The new ‘Basic Anticipation Process’

Since 2017, the new National Forum for Skill Anticipation (Osaamisen ennakointifoorumi) serves as an expert body for skill anticipation and coordinates sector-specific anticipation groups. Nine anticipation groups are responsible for the anticipation of competence and skill needs in their specific sector, the development of recommendations to improve education and training and the conduct of further research. Each anticipation group is composed of the social partners, representatives of educational providers, trade unions of teaching staff, researchers and members of the education administration. The nine sectors covered are natural resources, food production and the environment; business and administration; education, culture and communications; transport and logistic; hospitality services; built environment; social, health and welfare services; technology industry and services; process industry and production. Anticipation groups draw on a wide range of experts in the anticipation process.

The anticipation process involves a series of five workshops, supported by preparatory exchanges on electronic platforms and a series of background studies. The VATT industry forecasts estimating workforce demand until 2035 is one of the key inputs to the exercise and is adjusted using qualitative information. Key outputs of the workshops are scenarios for the development of the employment, industrial and occupational structure, as well as competence, skill and educational needs arising from these. EDUFIN’s foresight unit translates these insights into quantitative estimates of educational needs. The first results of the ‘basic anticipation process’ were published in early 2019. In addition, EDUFIN supports regional anticipation exercises carried out by regional councils.

Source: Nyyssölä (2019[17]), “The Finnish Anticipation System”; Finnish National Agency for Education (2017[19]), “The anticipation plan of the National Forum for Skills Anticipation”; Finnish Board of Education (2019[20]), Osaaminen 2035 – Osaamisen ennakointifoorumin ensimmäisiä ennakointituloksia [Expertise 2035 – First Foresight Results from the Foresight Forum], www.oph.fi.

On the employment side, the MoEE publishes short-term labour market forecasts twice yearly in spring and autumn. The basis for these forecasts are labour market, demographic and national account statistics, the economic forecast by the Ministry of Finance, recruitment tracking data and regional economic surveys (Alatalo, Larja and Mähönen, 2019[21]). It provides forecasts for short-term overall labour demand, as well as demand in the broad sectors of the economy.

At a regional level, most regions carry out their own skill anticipation exercises bringing together different stakeholders in anticipation committees. Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY centres) and the Employment and Economic Development Offices (TE offices) play a key role in these processes. ELY centres have the responsibility for matching skill demand and supply and the anticipation of continuous learning needs. Skill anticipation exercises conducted by ELY centres are typically short-term. TE-offices also conduct employer surveys on behalf of ELY centres (Berge, Berg and Holm, 2015[14]). A key tool is the Occupational Barometer (ammattibarometri), which forecasts short-term occupational needs at the regional level. The barometer summarises the views of the TE offices about the employment prospects of 200 key occupations in the coming 6 months, based on employer visits and interviews with employer and employees. The results of this exercise are publicly available.3

In addition, vocational and higher educational institutions are required by law to conduct anticipation activities (Skills Panorama, 2017[22]). These exercises typically involve labour market representatives. Some institutions are making use of AI in these anticipation exercises (see Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Using artificial intelligence to anticipate skill needs

The Helsinki Metropolitan Universities of Applied Sciences1 collaborate with Headai Ltd., a for-profit organisation specialised in artificial intelligence (AI), to analyse the gap between the skill needs of the labour market and their education offer.

Headai uses AI (natural language processing algorithms) to analyse job advertisements and extract real-time information on the demand for skills in the labour market. This information is then compared to the skills conveyed in existing education programmes, extracted from curricula and study programmes using the same technology. Both skill demand and the skills supplied through existing education programmes are visualised in competence maps. These maps are also useful to compare the skill content of different education programmes.

The institutions aim to use this data to: i) Understand current and future skill demand; ii) Provide information and guidance to students on course selection and individual learning paths; iii) Shape curriculum development; iv) Make the education offer more competitive; and v) Develop competences of university staff.

Headai received the Ratkaisu 100 Challenge Price in 2017 for its innovative work on skill mapping, which was awarded by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra.

1. An alliance of the three Universities of Applied Sciences: Haaga-Helia, Laurea and Metropolia.

Source: Ketamo et al. (2019[23]), “Mapping the Future Curriculum: Adopting Artifical Intelligence and Analytics in Forecasting Competence Needs”, http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2019053117966; Headai (2019[24]), “Customer Story: Helsinki Metropolitan Universities of Applied Sciences”, https://medium.com/headai-customer-stories/customer-story-3amk-4f7944080344; Sitra (2019[25]), “How can we predict what expertise will be needed in the future? Artificial intelligence knows – Sitra”, https://www.sitra.fi/en/articles/can-predict-expertise-will-needed-future-artificial-intelligence-knows/; Sitra (2017[26]), “Artificial intelligence shows what Finland can do and a positive CV reveals the hidden talents of young people: The winners of Sitra's million-euro Ratkaisu 100 Challenge competition”, https://www.sitra.fi/en/news/artificial-intelligence-shows-finland-can-positive-cv-reveals-hidden-talents-young-people-winners-sitras-100-million-euro-ratkaisu-100-challenge-competition/.

Using anticipation information to shape adult learning provision

Skill anticipation information can be used to influence the behaviour of individuals, providers and employers to take-part in and offer learning opportunities in line with skill demands (OECD, 2019[11]). Typical instruments include information provision, setting adapted financial incentives and regulating the education and training provision in line with labour market needs.

Information from skill anticipation exercises is made available to the public through reports, websites and other communication tools. In theory, this information can be used by individuals to make informed choices about engaging in learning, which enables them to gain skills that are in demand in the labour market. In reality, policy-makers and professionals, such as career guidance staff in TE-centres, are the primary users of this information. There are ongoing initiatives within the MoEE and MoEC to make this information available online in a more user-friendly format.

Many countries use financial incentives to steer educational choices (OECD, 2017[9]). The Finnish tradition of public, universal and free or low-cost adult learning provision currently limits the instruments available to steer educational provision and take-up (see challenges below). Most adult learning provision is currently free of charge or available at low-cost to the individual. Course costs are not currently used to incentivise or dis-incentivise the take-up of adult learning opportunities in line with skill demand. An exception is the use of training vouchers for specific groups in adult liberal education, which pays for (part of) their training costs. However, the link to skill anticipation is limited, as the vouchers are typically not tied to specific education and training courses. Similarly, the availability of financial support to the livelihood of individuals during their studies (adult education allowance, scholarship for qualified employees, financial aid for students) is not tied to the labour-market relevance of the pursued training option. Exceptions are the financial support options provided to unemployed individuals who take up training (social assistance for the unemployed in training, self-study allowance), as TE-offices solely support labour-market relevant training for the unemployed. The judgement of labour-market relevance is typically based on a case-by-case decision of a career counsellor.

Skill anticipation information plays a role in the regulation of education and training provision. At a national level, results of the EDUFI anticipation exercises inform the planning of educational provision to some extent. In the past, forecast results have been used in the preparation of the Education Development plans (Berge, Berg and Holm, 2015[14]), yet no such plans were developed in recent years. When they existed, forecast results and targets set in development plans were never fully aligned (Hanhijoki et al., 2012[27]). The most recent anticipation exercise by the Skill Anticipation Forum suggests wide reaching reforms of the continuous learning system and that resources should be transferred from formal education to (non-formal) continuous education. It remains to be seen if and how the incoming government will implement these recommendations (Finnish National Agency of Education, 2019[28]).

More generally, skill anticipation exercises inform the quantity of educational provision as they are taken into account when setting admission targets for vocational education, granting operating licenses for VET and higher education providers and when negotiating the scope of educational provision with universities (Hanhijoki et al., 2012[27]). Results also influence the content of provision as EDUFI uses the results to develop qualifications, curricula and teaching contents for vocational qualifications. Beyond using skill anticipation information directly, recent reforms have strengthened the systemic mechanisms that align formal training with labour market needs. Funding for VET and higher education institutions is now tied to labour-market related indicators such as the employment rate of graduates.

At the regional level, the Occupational Barometer and other anticipation exercises by the ELY-centres and TE-offices are used by career guidance counsellors and in the commissioning of labour market training. Education providers increasingly use information from their own skill anticipation exercises to shape provision (Berge, Berg and Holm, 2015[14]).

Key challenges

Finland has a wide array of learning opportunities for adults. Yet, they could be better calibrated to help individuals gain the relevant skills for a changing labour market in a more efficient way. Key challenges relate to: greater incentives for participation in formal learning than non-formal learning; the existence of some specific gaps in the provision; and the limited alignment with labour market needs.

The existing structure favours formal over non-formal learning.

Formal qualifications are highly valued in the Finnish labour market and society. Finnish adults (25‑64) have the highest formal learning participation of any European country and are 2.5 times more likely to take part in formal education than the EU-average (14.2% vs. 5.8%). While formal learning participation has decreased in Europe over the past decade, it has significantly increased in Finland.

Some of this can be explained by prolonged initial education careers in Finland, but even older age groups are twice as likely to participate in formal learning as their European counter-parts. Finland’s existing adult learning provision promotes participation in formal learning: most formal education is open to adult learners; the completion of formal qualifications is generally free of charge; and financial support is available for those studying towards a qualification. By contrast, non-formal education offers are typically subject to a (small) fee and financial support to pursue them is more limited. It is perhaps unsurprising then that an increasing share of adults participate in formal education programmes that were initially conceived as initial education options for young people.

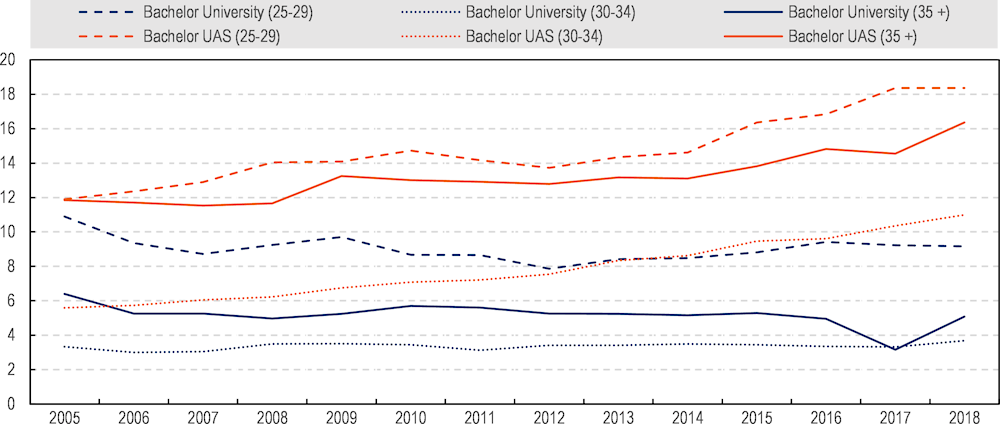

Bachelor’s degree programmes, for example, are relatively lengthy programmes (3‑4 years of full-time study) that are intended to allow individuals to gain a first academic qualification in a chosen field and access to the labour market. The share of adults aged 25+, who register for a Bachelor’s degree (‘new students’) at higher education institutions, has steadily increased over the past 15 years (Figure 3.2). Some of the new starters already hold bachelor’s degrees: this is the case for 18% of adults at UAS and 45% of adults at universities.

Figure 3.2. Adults increasingly pursue bachelor degrees at UAS

Note: New students refers to students registered for the first time with the institution as being present or absent in their degree programme. This includes students who are changing institution or course, i.e. are not new to higher education.

Source: Statistics Finland, Vipunen database.

Many adults have legitimate reasons to pursue a first tertiary degree later in life, because of, for example, not meeting entry criteria when they were younger or a lack of available study places. They may also want to acquire work experience first, before taking-up study towards a higher education degree. This is in particular the case for adults who take-up Bachelor degrees at UAS. However, the take-up of initial education opportunities by adults can point to in-efficiencies in the adult education system, particularly when adults obtain repeated formal degrees at the same level they already hold (e.g. repeated Bachelor degrees):

Pursuing a lengthy initial vocational or higher education degree can help some adults with professional reorientation, for example, when they can no longer work in their initial profession due to health reasons or when their initial occupation is subject to widespread automation. Yet, in the majority of cases, pursuing a three to four year initial degree is not a time and resource efficient way to keep abreast with the changing skill needs of the labour market. The high and increasing take-up of initial education opportunities may point to a lack of other formal, non-formal and informal opportunities more suited to adults’ needs.

The lack of a distinction between adult and youth education may also have negative effects on the education opportunities of young people. Recent general upper secondary graduates can face waiting times of several years to get access to the highly restricted university places. Taking as an example the cohort of those who graduated with general upper secondary education in 2011, 77% applied to higher education in the year of graduation, yet only 38% were able to enter higher education in that year. 5-years after graduation, only 81% of the cohort had studied in higher education while 94% had applied. In the meantime, many choose to take part in fee-based Open University provision, which can give access to degree programmes at regular universities. Research from 2007 suggests that around 40% of students in Open Universities might be young people aiming to get a degree by transferring to a regular study programmes (Jauhiainen, Nori and Alho-Malmelin, 2007[5]). Anecdotal evidence indicates that the share of young people participating in Open University Studies has increased since then.

There are some important gaps in the continuous learning provision.

Need for shorter non-formal learning opportunities that are labour-market relevant.

Most adults need shorter, labour-market relevant learning opportunities that they can pursue alongside their work and family responsibilities. These opportunities allow adults to become effectively continuous learners over the life-course, rather than learners that take out substantial blocks of time to pursue further formal qualifications a few times in their lives. By contrast, formal learning is time and resource intensive, has limited returns (see Box 3.4) and does not necessarily lead to upskilling, e.g. in the case of working towards several qualifications at the same level.

Currently, job-related non-formal learning opportunities include provision at open universities/UAS, non-formal vocational training at VET schools, some limited job-related training opportunities at Adult Education Centres and Folk High Schools (e.g. photoshop, basics of accounting), as well as training organised by TE-offices and employers themselves. While these programmes are short in comparison to formal education, they are often organised in modules that still require significant time investment of individuals. Employers are advocating the development of short courses that equip individuals with specific labour market specific skills. The expectation is that these courses would be even shorter than the modular provision that already exists in some parts of the adult learning system.

Further, where non-formal learning opportunities are available, employers or public employment services typically moderate access to them. Opportunities that can be accessed by individuals on their own initiative and at their own (potentially subsidised) cost are also limited.

Lack of opportunities to gain higher vocational skills.

The majority of initial and further vocational training in Finland takes place at Level 4 of the European Qualification Framework, i.e. at a level equivalent to general upper secondary qualification. Only specialist vocational qualifications are categorised at Level 5 of the European Qualification Framework, although the level of these qualifications is considered low. Given the limited higher vocational development opportunities for adults with vocational degree, many pursue Bachelor’s degrees at UAS to upskill. As described above, these are lengthy and may not be the most appropriate provision for adults with work-experience looking to qualify further.

Higher vocational post-secondary degrees have existed in Finland in the past, but disappeared when higher vocational colleges were transformed into polytechnics (later UAS). A key aim of the ‘polytechnic experiment’ of the 1990s was to channel the increasing demand for higher education to newly created polytechnics, rather than universities, and to diversify education provision (OECD, 2003[29]). At the same time, a reform of the university degree system introduced three-year Bachelor degrees at Polytechnics, which replaced shorter upper-secondary vocational degrees (OECD, 1999[30]).

These reforms upgraded the provision of many former higher vocational colleges to tertiary-level education, yet effectively abolished post-secondary non-tertiary education in Finland (with the exception of specialist vocational qualifications). Adults with vocational degrees now have limited options for up-skilling beyond taking three-year bachelor degrees and specialist vocational qualifications.

The use of skills anticipation information for the steering of education provision is limited.

Good information on skill needs is important both for steering the provision and take up of education and training. Finland has an abundance of skills anticipation exercises at all levels of governance, yet it has been argued that their link to policy-making could be stronger (Kaivo-Oja and Marttinen, 2008[31]; OECD, 2016[15]; Berge, Berg and Holm, 2015[14]). The exact mechanisms by which skills anticipation information feeds into policy design often remain unclear. Some stakeholders seem to believe that the information automatically translates into education provision, for example by virtue of the National Agency of Education being responsible for both skills anticipation and the formulation of qualifications and curricula. In reality, formal mechanisms to link both are often lacking. A notable exception are the training activities organised by the ELY-centres, which are designed to respond to the short-term skill needs identified in regional anticipation exercises.

Even where skills anticipation exercises are consulted, adult education providers have significant freedom to shape the quantity and content of the education offer. Following licencing and agreements with the MoEC, providers can transfer admission numbers between different fields if this stays within the overall numbers specified.

Perhaps most importantly, the public, universal and free nature of much adult learning provision constitutes a key challenge to the use of skill anticipation information in the steering of educational choices by individuals. While other countries use financial incentives to steer individual demand towards specific courses, e.g. by lowering tuition fees for university programmes for skills in demand, such mechanisms are not currently possible in the Finnish context of free adult education.

Box 3.4. Wage returns to training

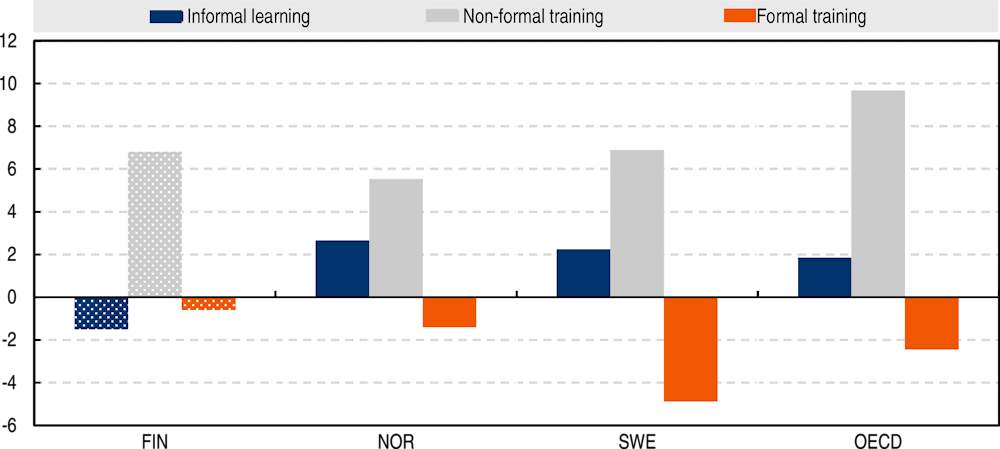

While participation in adult learning in Finland is high, there is only limited evidence that it leads to positive labour market outcomes. Recent evidence from OECD research suggests that the wage returns to learning participation are modest (Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, 2019[32]). In Finland, participation in non-formal learning is associated with 7% higher wages, while participation in informal and formal learning is associated with lower wages (-2% and ‑1% respectively). Other Nordic countries see similar returns to non-formal learning, but participation in informal learning is associated with higher wages. These effects are correlations and should not be interpreted as causal.

These findings are in line with national research on the effects of take-up of the education leave subsidy, which is used during long-absences from work for the purpose of obtaining formal qualifications (Kauhanen, 2018[33]). It finds that while participation substantially increases educational attainment, it has a negative effect on employment and earnings not only during the lock-in period, but also up to four years after take-up of the subsidy. An exception to these findings concerns participation in polytechnic education. Research suggests that adults aged 25+ who attend polytechnic education have significantly higher earnings and employment rates than comparable adults without a tertiary degree. Ten years after starting a polytechnic degree, earnings are close to EUR 4 000 per year higher than those of the comparison group (Böckerman, Haapanen and Jepsen, 2017[34]).

Figure 3.3. Participation in formal and informal adult learning are associated with lower wages

Note: Job-related formal and non-formal training are computed based on workers who report that the latest training activity was job-related.

Source: Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, (2019[32]), Returns to different forms of job-related training: Factoring in informal learning, https://doi.org/10.1787/1815199X, based on PIAAC (2012, 2015).

As returns are measured a relatively short time-period after training in Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer (2019[32]), further positive effects may occur later or may require a job-move to materialise. This is particularly true for Finland, a country with high wage compression and a high share of public sector workers. Results may also reflect differences in quality and labour-market relevance of training across countries, as well as shares of workplaces that apply High Performance Work-organisation Practices (HPWP) as these are typically associated with higher returns to training.

Policy recommendations and good practices

Recommendation

Before implementing any specific policy recommendations, Finland should develop an overarching vision for its continuous learning system. This would include how different types of provision contribute to the whole and a review of the linkages of the adult learning system and other policy areas, such as initial education, wage setting, health care or social security, as there are important interaction effects between them. This would help to prioritise the action that should be taken and identify complementary measures that would increase the effectiveness of the proposed policy reforms. Therefore, Finland may wish to:

1. Develop a joined-up strategy for a future-ready system of continuous learning.

To address the specific challenges identified above, Finland should consider: i) diversifying the training offer; ii) making the training offer more labour-market relevant; and iii) incentivising individuals to take part in the ‘right’ offer. In each of these areas, Finland could draw on international examples of good practice. This should be part of an overall vision for reform of Finland’s continuous learning system.

Diversify the training offer

Recommendations

Finland has a wide-range of well-utilised learning opportunities, but some gaps in the provision remain. In particular, the Finnish continuous learning system could benefit from:

1. An expansion of the non-formal training offer;

2. Re-introducing opportunities to gain higher vocational skills;

3. Exploring the introduction of short-cycle tertiary education.

Any diversification of the training offer must go hand-in-hand with a clear placement of new offers in the current Finnish qualification system and be implemented with the goal of keeping the qualification structure transparent for individuals.

Improving the market for non-formal training.

Giving individuals more access to non-formal training opportunities, addresses several key challenges of the Finnish system. Non-formal learning opportunities are specifically directed at (working) adults. If properly designed, funded and quality assured, they have the potential to ensure that adults do not crowd out initial training opportunities designed for young people. They also have the potential to be short and labour-market relevant, specifically when designed with the strong involvement of employers. These learning opportunities would enable adults to update their skills continuously over the life-course, while being compatible with their work and family responsibilities Shorter non-formal training would also reduce the payback time to make the investment in training worthwhile.

Improving the market for non-formal training options and incentivising the take-up of such options is a complex undertaking. The functioning of the current market for labour-market relevant short courses may require radical solutions to shift away from the status quo. The change requires rethinking the funding for non-formal provision and experimenting with more market-based solutions. In a qualification-driven education system such as Finland, it also necessitates the development of certification systems for non-formal short-courses and a determination of how these non-formal courses relate to formal qualifications, e.g. by constituting micro building blocks of formal qualifications.

It is likely that Finland will build on its tradition of open, universal and free or low-cost provision, when it comes to the expansion of non-formal training opportunities. Consideration must therefore be given to how public and, more importantly, private providers can be incentivised to offer non-formal training opportunities, while keeping costs low for individuals. The recent Working Group on Continuous Learning (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[35]) explored different funding options for continuous learning provision, without recommending a specific solution due to political differences. Key ways in which non-formal training provision could be expanded and made more market-based include:

Public procurement in open calls for tender: This involves the public funding of non-formal training provision, following a public procurement process and selection of public and/or private providers. Providers deliver education and training in line with a contractual agreement with the responsible ministries, which specify performance targets and related funding. Estonia, for example, has been offering short-term non-formal vocational courses free of charge since 2009. Since then, approximately 75 000 adults have taken part in these courses, which is approximately 10% of the Estonian adult population aged 25‑64. Courses provide training opportunities in line with labour market needs, comprise between 20 and 100 academic hours and are free of charge to the individual. Providers are currently vocational and higher professional education institutions, which are selected in yearly calls for tenders issued by the Ministry of Education. While the non-formal training offer has led to positive labour market outcomes for individuals (Leetma et al., 2015[36]), it should be noted that the state-funded provision has essentially crowded out private providers of non-formal learning. This could be addressed by opening the calls to private providers meeting specified quality criteria.

Voucher schemes cut out the governmental procurement process and directly link funding for providers to the training choices made by individuals. In the countries using vouchers, individuals are given vouchers by the responsible ministries that can be used to cover part or all of the direct training costs. Training providers receive funding when the individual signs-up and/or complete a training course. Vouchers schemes can be used for both public and private providers meeting certain quality criteria and hence can incentivise a market of non-formal training provision. In Germany, for example, training vouchers (Bildungsprämie) are available for employed individuals on low-incomes, as well as individuals who are on care leave (BMAS, 2019[37]). These vouchers can be used for job-related vocational or basic education, language and ICT training at education and training providers that meet specified quality criteria. The vouchers cover 50% of the training costs, up to EUR 500. Individuals must take part in career guidance counselling at one of 530 guidance centres before getting access to the voucher. Finland has experience of using a voucher-based approach for liberal adult education courses, yet these currently do not cover private providers and only cover very specific groups of adults.

Individual learning accounts link funding of providers to training choices made by individuals. Individuals can typically accumulate rights to training/resources in their account over time, which are then mobilised when training is undertaken (OECD, 2019[38]). Providers are paid when the individual takes up training and/or completes their course. The French Individual Learning Account Scheme (Compte Personnel de Formation) allows individuals aged 16+ to accumulate up to EUR 500 per year in ‘training rights’ in their individual account up to a ceiling of EUR 5 000. Thresholds for adults with low-skills (below ISCED 3) are higher with EUR 800 per year and EUR 8 000/overall. Credits are transferable between employers and are maintained if labour market status changes. Training rights can only be used towards recognised qualifications or basic skill training. A similar model could be implemented for the participation in non-formal training, if implemented alongside sufficient quality assurance mechanisms.

To make non-formal learning an attractive training choice for individuals, the training offer must be of high quality. Currently, public providers are responsible for ensuring the quality of their provision with the support of FINEEC. In the context of introducing more market-based mechanisms, more complex quality assurance mechanisms, such as accreditation of providers and the introduction of a certification system for non-formal short-courses, must be considered. Many countries are grappling with the issue of quality assurance of adult education. Austria introduced the national quality assurance system Ö-Cert in 2011 to improve transparency in the very heterogeneous market of an estimated 1 800 to 3 000 adult learning providers in Austria. While Finland would start from the opposite end of the spectrum with a limited number of adult learning providers, there are important lessons from the basic quality requirements set in Austria. To obtain the Ö-Cert certification, providers must meet basic requirements regarding: i) the corporate mission and responsibility; ii) their organisational structure and staff competences; iii) the nature of courses offered; iv) a commitment to ethical principles and democracy; and v) the existence of an approved quality management system. Quality is assessed by submitting a quality certificate by any of the Ö-Cert approved certification providers (EPALE, 2019[39]; Bundesministeriums für Bildung, 2017[40]).

Certification systems should be developed with strong employer involvement to achieve buy-in and labour-market relevance. One way to achieve this is by giving employer organisations the responsibility to certify non-formal training. In Germany, for example, the Chambers of Commerce and Industry (IHKs) are entrusted to certify shorter courses in their fields. An example from the retail industry is the Shop Manager Course, which covers higher level skills as it intends to train managers, but in a context that is closely related to a specific occupation and job role. Such courses are widely known and recognised by employers, therefore they provide pathways for career progression.

Re-introduce opportunities to develop higher vocational skills.

The transformation of higher vocational colleges into polytechnics and later Universities of Applied Sciences has left a gap in the provision for higher-level vocational skills (i.e. post-secondary, non-tertiary opportunities). Re-introducing such opportunities is critical in order to provide upskilling pathways for the approximately 40% of the Finnish population whose highest degree is a vocational degree and who wish to gain further vocational qualifications. In order to shift the entire skill distribution of the Finnish population upwards, it is essential that these opportunities allow people to upskill to higher levels, i.e. Level 5 and Level 6 of the National Qualification Framework, rather than solely obtaining further qualifications at the level already held. Diversifying the education and training offer at this level may also help to alleviate the pressure on the higher education system as the sole upskilling pathway after the upper secondary level.

Only a small number of countries offer higher vocational qualifications at EQF-level 6. These countries typically have strong dual VET systems, such as Austria, Germany and Switzerland. In Germany, advanced further training (Aufstiegsfortbildung) leads to ‘Master craftsmen’ qualifications. The pre-condition for participation is, similar to the specialist vocational qualifications in Finland, typically an initial vocational degree and work experience. It is not necessary to take part in an advanced further training to be admitted to take a ‘Master craftsmen’ qualification. The training qualifies individuals to take greater responsibility in the workplace and equips individuals with specific rights such as the right to open their own business or to train apprentices. Courses are provided by certified public or private education providers, as well as educational institutions of the Chambers of Commerce and Trade. The Chambers are also the responsible body for the award of the qualifications (Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz, 2016[41]; Bundesministerium für Justiz und Verbraucherschutz, 2005[42]). The social partners and professional organisations are key players in the design, implementation and quality assurance of further training courses.

Switzerland provides upskilling opportunities at EQF Level 6 through its Professional Education and Training System (PET, höhere Berufsbildung). Professional Education prepares individuals for demanding occupational fields and leadership positions. Similar to Finland’s dual tertiary sector with Universities and Universities of Applied Sciences, the PET sector constitutes a parallel tertiary sector (Tertiary level B) next to the higher education system (Tertiary level A). PET training institutions can be public or private, as well as run by the social partners. They include professional colleges (höhere Fachschulen) and preparatory courses for National PET examinations (Eidgenössische Berufsprüfung, höhere Fachprüfung) (Fazekas and Field, 2013[43]). The social partners, professional organisations, federal and cantonal governments are key players of the PET system. The federal government has the responsibility for the overall development and quality assurance of the system; it also approves examination regulations of PET qualifications. Professional organisations define the content of qualifications and assessment criteria; they also provide PET training opportunities. The cantonal governments are responsible for the supervision of professional colleges and to some extent preparatory courses of National PET examinations. Social partners contribute to the further development of the system (Staatssekretariat für Bildung, 2017[44]; Fazekas and Field, 2013[43]). These qualifications play a significant role in the Swiss qualification landscape. According to the Federal Office for Statistics Switzerland, approximately 27 000 people gained a tertiary qualification through the PET system in 2018, close to the number of people who gained Bachelor-level degrees at universities and universities of applied sciences in that year (31 500).

It may be argued that the Finnish vocational system does not follow the same tradition as the dual VET systems of Austria, Germany and Switzerland, making it difficult to transfer their practices. While some aspects are indeed embedded in their specific national contexts, it should be noted that Finland used to have a system of higher vocational qualifications in the past. With the former higher vocational colleges having been transformed, it is now worth considering which educational institutions could offer higher vocational programmes in the future. Most promising candidates are Vocational Schools, UAS or partnerships between both types of institutions. Key learning from good practices in other countries include: the leadership role of professional organisations in the design of these qualifications, the specification of added rights acquired through vocational upskilling (e.g. training apprentices), as well as the equivalent status of higher level vocational and academic Bachelor’s degrees at Level 6 of the EQF.

Explore the introduction of short-cycle tertiary education.

While taking entire Bachelor degrees might be relevant to some adults, it is unlikely that this provision is relevant to the upskilling and reskilling needs of the vast majority. It is therefore good practice across OECD countries that the tertiary education offer includes practical-based short-cycle degrees to provide opportunities for those who do not have the time or inclination to take part in three-year bachelor degree courses. Some commentators have gone so far as to describe short-cycle tertiary courses as “the missing link” between secondary and higher education in Europe (Kirsch and Beernaert, 2011[45]).

The majority of OECD economies have short-cycle tertiary education as part of their educational offer (Kirsch and Beernaert, 2011[45]; Cremonini, 2010[46]). This includes Finland’s Nordic neighbours Denmark and Norway. In Denmark, for example, nine Business and Technical Academies (erhvervsakademier, equivalent to UAS) offer short-cycle higher education programmes. These programmes are of 2-years duration (120 ECTS) and lead to the award of an academy professional degree (erhvervsakademigrad, AK). Graduates have the opportunity to convert this degree into a bachelor’s degree with an additional year (60 ECTS) of study, i.e. through participation in a Top-up Bachelor degree programme. In Denmark, 18% of first-time tertiary graduates graduate with a short-cycle degree. Short-cycle graduates benefit from somewhat higher employment rates and relative earnings compared to graduates of Bachelor’s degree programmes, likely due to their more practical orientation (OECD, 2018[47]).

Short-cycle tertiary education at ISCED Level 5 is defined as having a minimum 2-year duration (OECD, 2015[48]). However, some countries offer programmes of even shorter duration at tertiary level. The Higher National Certificate in the United Kingdom is a higher education qualification awarded after one year of full-time study. Study programmes aim to help individuals develop the skills required in a particular area of work. Higher National Certificates can constitute the first year of a two-year Higher National Diploma qualification, which itself can be expanded to a Bachelor’s degree qualification after a third year of study. Further education colleges or higher education institutions offer study programmes. Around 13% of first time tertiary graduates graduate with a short-cycle tertiary degree in the UK (OECD, 2018[49]).

Finland itself has experimented with short-cycle tertiary study programmes in recent years. Between 2013 and 2016, the JAMK University of Applied Sciences ran a pilot project on short-cycle tertiary education funded by the MoEC (JAMK, 2019[50]). JAMK UAS offered four study programmes,4 awarding a Diploma of Higher Education (Korkeakouludiplomi) after 1-year of full-time study (60 ECTS). As the programme was implemented in the context of Open UAS studies, participation did not lead to a degree, but could form the basis of a regular bachelor’s degree. It was also subject to the regular fees for Open UAS study. Research on the pilot found that around half of the participants took part in the new programme to improve the skills and knowledge for their current job, while the other half took part in the programme as a stepping stone into degree study or to a career change. The evidence also suggests that the employment and wage impact of participation was clearly limited, as no formal qualifications were acquired (Aittola and Ursin, 2019[51]).

Based on the national and international experience, Finland should consider the introduction of short-cycle tertiary learning opportunities with the view to incentivising take-up of tertiary education of groups that would traditionally not do so. This includes the large share of Finns with vocational qualifications at FiNQF Levels 4 and 5. The introduction of short-cycle tertiary education may also ease the pressure on the initial Bachelor’s degree education system, where individuals are solely looking to take tertiary-level courses rather than entire Bachelor’s degrees. Learning from good practice, it will be essential to i) implement pilots on the introduction of short-cycle tertiary degrees; ii) reflect on the subject areas in which short-cycle tertiary degrees can provide added value to students and the labour market; iii) test the desirability of these study options for individuals and employers and iv) design transition pathways from short-cycle to full-degree programmes.

Make the offer more labour-market relevant

Recommendations

Several of the key challenges of the Finnish continuous learning provision relate to its relatively weak labour-market relevance. To ensure a provision that is responsive to the skill needs of the labour market, Finland could benefit from:

1. Systematising the use of skill anticipation information for strategic planning;

2. Harnessing the capacity of employers to develop training programmes;

3. Setting incentives for providers to offer training in line with skill demand.

Systematise the use of skill anticipation information for strategic planning.

Finnish stakeholders conduct a plethora of skill anticipation exercises, yet the mechanisms to translate this information into skill strategy and policy are underdeveloped. The planned parliamentary reform on continuous learning (Finnish Government, 2019[12]) should be used as a forum to review current practices in this area and develop systematic mechanisms by which skill anticipation informs the strategic planning of continuous learning policy. This could include the reinstatement of strategic plans in the area of continuous learning and institutionalising their regular update based on skill anticipation information. Any strategic plan will need to allow flexibility to adapt national level strategy to local labour market needs.

Many OECD economies are thinking about how to better link skill anticipation and strategic planning and it is difficult to point to one single country as an example of good practice across the board. Among countries that are already implementing the use of skills anticipation information in strategy planning the following stand out:

Latvia has set a national strategic objective of increasing the share of students pursuing vocational upper secondary education to 50% by 2020 (compared to 39% in 2017/2018). The target is based on forecasts by the Ministry of Economics showing a shortage of workers with vocational degrees by 2025 (OECD, 2019[52]).

In Estonia, annual reports on changes in labour market developments, labour requirements and the trends driving those changes are prepared under the OSKA skill anticipation system (OSKA, 2019[53]; OSKA, 2018[54]). The Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund (Eesti Töötukassa) uses this information systematically to set training priorities in the context of active labour market policies.

Harness the capacity of employers to develop training programmes.

The role of employers in shaping the continuous learning provision in Finland is limited compared to their role in many other OECD economies and often primarily consultative, for example when anticipating skill needs or creating qualification requirements. Yet, employers have substantial knowledge on the skills needed in the labour market. Finland should harness the knowledge of employers to design labour-market relevant adult education and strengthen their involvement in the development of learning opportunities.

Employer involvement seems to already work relatively well at the local level, where employers develop training programmes in consultation with vocational or higher education providers. At the national level, the development of adult learning opportunities in Finland is strongly driven by public stakeholders, leaving limited space for more active involvement by employers. Other OECD countries give (groups of) employers stronger responsibility to shape training provision outside of governmental control and to share information about their training needs. In Ireland, for example, Skillnet Ireland is an agency that promotes and facilitates continuous learning in Ireland with the objective to increase learning participation in enterprises (Skillnet Ireland, 2019[55]). The agency supports more than 65 employer-led Skillnet Learning Networks representing specific sectors or regions throughout the country, which develop and deliver training. Networks are required to conduct a Learning Needs Assessment of their member enterprises to gather information about their skill development requirements. Skillnet Ireland operates a joint investment model, where government investment in on-the-job training (raised through training levys) is matched by contributions from businesses. In 2018, the networks delivered over EUR 36 million worth of education and training programmes to more than 56 000 individuals in Ireland. Currently, Skillnet Ireland has close to 16 500 member companies, 95% of which are small and medium enterprises and 56% are micro-enterprises with less than 10 employees (Skillnet Ireland, 2019[56]). Evaluations of Skillnet Ireland repeatedly show that companies perceive the training provided through the networks to be in line with labour market needs (Indecon, 2018[57]).

Iceland implements a different approach to involving employers in the development and implementation of adult learning. Its Education and Training Centre (Fræðslumiðstöð atvinnulífsins) is co‑owned by the Confederation of Labour, the Confederation of Iceland Employers, the Federation of State and Municipal Employers, the Ministry of Finance and the Association of Local Authorities in Iceland. The Centre is contracted by the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture and has a wide range of responsibilities, including the identification of education needs, development and supervision of education and training programmes, development of training for adult educators, as well as administering the Education Fund. The Education Fund is funded through training levies and functions as funding vehicle for individual learning accounts in Iceland (OECD, 2019[58]; Education and Training Centre, n.d.[59]). The co‑ownership of the centre through employer organisations is key to establish a true joint responsibility in the area of adult education and training.

Finland should consider how it can empower employers to more actively shape continuous learning provision at a national level. It should consider experimenting with employer-led approaches, for example in the development of labour-market relevant non-formal learning provision.

Incentivise providers to offer training in line with skill demand.

Funding for adult education and training providers is traditionally not tied to whether their training offer responds to the skill demands of the labour market or not. Some elements of ‘effectiveness funding’ have recently been introduced for vocational schools and universities, which induce mild incentives for adult learning provision to be more labour-market relevant. 15% of the funding for vocational education and training institutions will be based on indicators relating to graduates accessing employment or further studies following graduation (Ministry of Education and Culture/ Finnish National Agency for Education, 2018[60]). Along the same lines, 6% of funding for UAS and 4% of funding for Universities will be based on the number of employed graduates and the quality of their employment by 2021. Yet, the vast majority of funding continues to be dependent on the number of degrees awarded and student progression. It has been argued that such measures will have little impact on the alignment of the training offer with the skills need of the labour market, given that effectiveness funding is just a small share – and one of many – funding streams (OECD, 2017[9]).

Other OECD member economies use stronger incentives to steer adult learning provision in line with skill demand:

Variation of public funding depending on skill demand: Denmark, for example, implements a taximeter system in the area of education funding. In the broadest sense, funding follows the users of education provision, which creates incentives for user-friendly behaviour. The grant is calculated based on the number of people participating in different education programmes, but the rates received per individual vary between programmes and groups of participants. Setting of rates is a political decision and takes into account societal and economic needs, as well as the costs and characteristics of a programme. Institutions are then free to use the obtained funding as they see fit, within existing frameworks (OECD, 2017[9]; Undervisningsministeriet, 2018[61]). Similarly, several Australian regions use skill anticipation information to determine the level of funding for vocational qualifications. In Queensland, for example, ‘priority one’ training courses for occupations in critical demand are 100% subsidised, while ‘priority two and three’ trainings are subsidised at a rate of 88 and 75% respectively (OECD, 2018[62]).

Regulating the set-up of new programmes: Higher Vocational Education in Sweden (Yrkeshögskolan) aims to provide learning opportunities in line with labour market needs. Programmes have a typical duration of six months to two years. In the Swedish model, employers develop programme proposals together with education providers. They then back the funding application made to the Swedish National Agency for Higher Vocational Education. Funding can only be obtained when a programme proposal is employer backed and clearly outlines employer demand for the programme (OECD, 2017[9]; Tomaszewski, 2012[63]).

Finland should consider strengthening the link between the skill demands of the labour market and the funding of providers of continuous learning opportunities. Ensuring that the provision is in line with labour market needs is particularly relevant in Finland, as the options for steering individual choices for the take-up of provision are limited (see below).

Incentivise individuals to take part in the ‘right’ offer

Recommendations

Finland’s tradition of public, universal and free adult learning provision has helped build motivation and raised participation. Yet, it yields an incentive structure that increasingly pushes adults to take-up formal learning opportunities, which may not be in line with their upskilling and reskilling needs. It also lacks incentives for adults to take-part in learning opportunities that equip them with the skills needed in the labour market. To steer educational choices of individuals, Finland could benefit from:

1. Providing better information on the labour-market relevance of training;

2. Reviewing and calibrating financial incentives for individuals.