As part of the peer review of Austria, a team of examiners from Ireland and the Slovak Republic, together with the OECD, visited Kosovo in June 2019. The team met with Austria’s Ambassador in Kosovo and the Head of the Austrian Co-ordination Office, as well as with Austrian diplomatic and development co-operation professionals, public authorities in Kosovo, parliamentarians, security sector actors, other bilateral providers, multilateral agencies, and civil society and private sector organisations.

OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Austria 2020

Annex C. Field visit to Kosovo

Abstract

C.1. Development in Kosovo

Despite progress since the conflict, several structural challenges are constraining Kosovo’s development

Kosovo is situated in the Western Balkans, with a population of approximately 1.8 million. Frictions between ethnic Serbian and Albanian communities culminated in the Kosovo conflict of 1998 and 1999, which ended after the intervention of the United Nations and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008 and declared the end of a period of “supervised independence” in 2012 (United Nations, 2012[1]).

Kosovo ranks around 85th on the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index, among the lowest in the Western Balkans region (UNDP, 2016[2]). It has lower middle-income status.1 Life expectancy increased from 67 to 72 years between 1999 and 2017 (World Bank, n.d.[3]), and the poverty rate is 29.7% (UNDP, n.d.[4]). Kosovo has introduced some reforms since 2008, yet significant barriers to development remain. Informality, growing state capture and corruption are major constraints on public spending.2 Further challenges are a large infrastructure gap; an unreliable, coal-based energy supply; and low labour-force participation and high unemployment, particularly among young workers (IMF, 2018[5]).3 Female labour force participation is very low at just 11.5%, compared to 51% in the European Union (EUI, 2018[6]) and the Western Balkans average of 45% (Atoyan and Rahman, 2017[7]).

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 3.5% over 2009-17 (World Bank, 2018[8]) is strong by the region’s standards and driven largely by remittances, which fuel consumption, and high levels of public sector spending and investments.4 The domestic private sector is underdeveloped and dominated by micro-enterprises, and trade is characterised by a high share of imports (UNDP, 2016[2]). A well-trained labour force could offer a major resource for economic growth in Kosovo, given its young population, averaging 26 years (World Bank, 2018[9]). However, the mismatch between skills and labour market needs (IMF, 2018[5]), and Kosovo’s weak education system (OECD, 2015[10]) is a critical challenge.5 Political interference (e.g. non-merit based appointments) is a particular challenge for higher education,6 while corruption, an unreliable energy supply and burdensome administrative procedures are holding back private sector development (European Commission, 2019[11]).

Kosovo’s current status and efforts to support its European Union (EU) integration – Kosovo’s ‘European perspective’ – also shape its development trajectory and context. Kosovo signed a Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU in 2015 and in 2018 was named as one of six Western Balkan countries and territories able to join the EU once it meets the criteria to accede. Kosovo’s progress has been slow in critical areas, such as governance, the functioning of democratic institutions and tackling the informal economy (European Commission, 2019[11]). Challenges also remain in negotiating the normalisation of Serbia-Kosovo relations.7

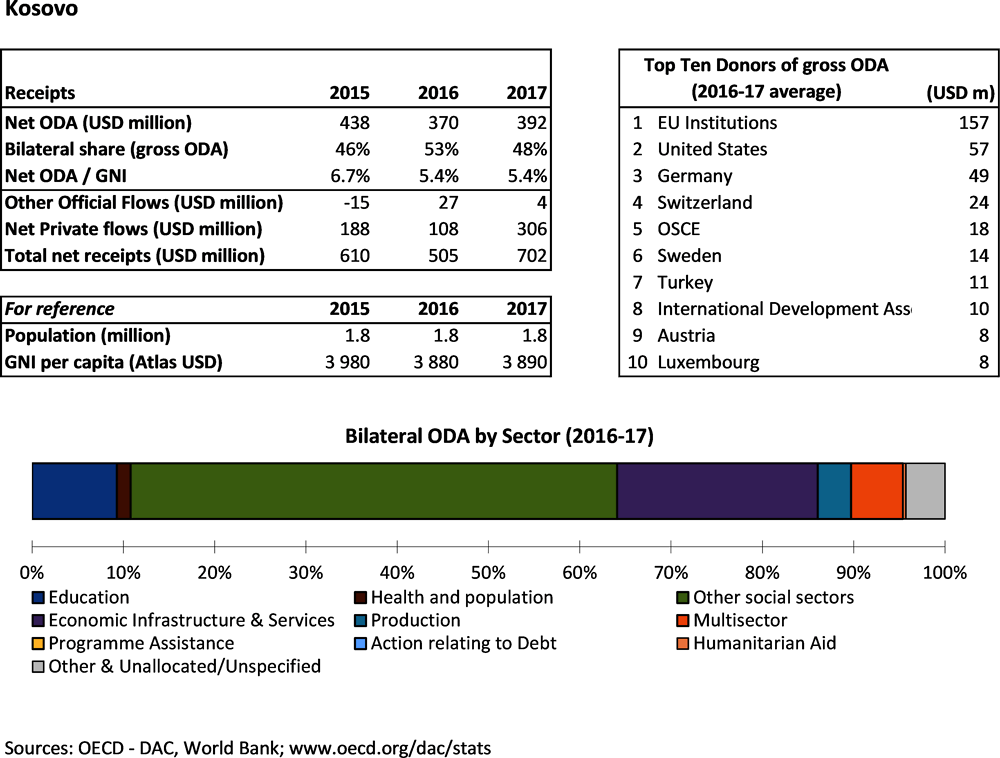

In 2017, official development assistance (ODA) accounted for 5.4% of Kosovo’s gross national income (OECD, 2018[12]). While this represents a decline in recent years, Kosovo continues to be one of the highest recipients of ODA per capita (OECD, CRS).8 The United States, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and Turkey were the biggest bilateral donors in 2017 (Figure C.1). The EU institutions remain by far the largest contributors, providing USD 156.5 million a year (averaged over 2016-17).

Figure C.1. Aid at a glance – Kosovo

Source: OECD (2019) Aid at a Glance Statistics, https://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/aid-at-a-glance.htm.

C.2. Towards a comprehensive Austrian development effort

Austria is a long-standing supporter of Kosovo’s state building, development and European perspective

Relations with the Balkan area are a core element of Austrian foreign policy. Austria has been involved in state building in Kosovo both bilaterally and via international efforts since the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Austria was also an early and long-standing supporter of Kosovo’s European perspective, including through bilateral institutional and cultural relations, notably around higher education (WUS Austria, 2007[13]).

Kosovo is one of 11 priority countries and territories in the current Three-Year Programme on Austrian Development Policy (MFA, 2019[14]). Austrian Development Cooperation (ADC) has worked through a liaison office in Pristina since 2003, and a Co‑Ordination Office since 2008, underpinned by a bilateral agreement between Austria and Kosovo. Austria’s Ambassador, resident in Pristina since 2009, is responsible for overall bilateral relations including economic, trade, cultural and security issues. In addition to the Ministry of Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs (hereafter, Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and Austrian Development Agency (ADA), the federal ministries of finance, the interior, defence, and education, science and research, the Federal Chancellery, and the Austrian Chamber of Commerce are all active in Kosovo and mostly keep the Embassy informed about their work (Government of Austria, 2019[15]). The Ministry of Interior is represented in Kosovo by a Police Attaché based at the Embassy, the Ministry of Defence by Austria’s representation on the NATO Kosovo Force (NATO-KFOR), and the Chamber of Commerce from its office in Slovenia. Austria continues to support and participate in the European Union Rule of Law Mission and the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK).9

Austria is well placed to bring about change in Kosovo

While the Kosovo Ministry for European Integration is responsible for donor co-ordination, primarily through an annual High-Level Forum, its capacity to steer donors is weak. Several European Union-funded aid‑management platforms have been ineffective and sector working group meetings are sporadic. Donors meet quarterly at an informal level and, in practice, tend to focus primarily on their own niche sectors.

Austria’s strong presence and its unique historical relationship with Kosovo is an opportunity to better align its political and development efforts. Austria engages in dialogue with Kosovo in its two priority sectors (education and economic development), and participates in sector working group meetings when they occur. However, given its valued, long-standing engagement in historically politicised sectors, such as higher education, and the regard in which it is held in Kosovo, Austria could strengthen its support to policy reform and do more to address underlying development challenges, such as growing state capture. This is particularly important given that the weak formal mechanisms for donor co-ordination in Kosovo are limiting the scope for donors to engage in dialogue with the public authorities and drive change.

C.3. Austria's policies, strategies and aid allocation

ADC’s engagement in Kosovo focuses on education and rural development

The current ADC strategy for Kosovo covers the period 2013-21 (ADC, 2013[16]).10 Its overall goals are poverty reduction through ecologically sustainable development; peace and human security through the strengthening of the rule of law, democratic institutions and respect for minority rights; and support for Kosovo’s European and regional integration. The strategy identifies two priority sectors: private sector development focusing on rural areas, and education, in particular higher education. It also includes governance as an additional cross-cutting theme; however, this theme is not yet well integrated into the two sectoral programmes (Kacapor-Dzihic, Hajdari and Van Caubergh, 2018[17]). More could be done to leverage Austria’s recognised work in these sectors and to address cross-cutting governance issues. For example, fighting corruption could feature more prominently in Austria’s education programmes, e.g. by integrating this issue into academic curricula and training.

Efforts to target specific issues within ADC’s priority sectors align with Kosovo’s development needs and Austria’s capacity to add value. The focus on higher education places emphasis on quality assurance and compliance with international and EU standards, and support for matching higher education to labour market needs. This reflects continuity in Austria’s long-term engagement, is appreciated and aligned with the needs expressed by Kosovo, and does not duplicate other actors’ efforts.11

Aid allocations reflect both Austria and Kosovo’s priorities

The long-standing and consistent nature of Austria’s engagement is widely recognised and appreciated by public authorities and local partners. In 2016-17, Austria was the sixth largest bilateral donor, providing USD 8.4 million to Kosovo in ODA on average a year (OECD, 2019[18]). Over 2013-17, it is estimated that Austria also channelled USD 3.9 million to Kosovo via multilateral channels (using imputed figures and 2017 constant prices) (CRS, OECD). While Austrian bilateral ODA to Kosovo has decreased in recent years, Austria is seen as a committed, longstanding and predictable partner by Kosovo, and overall awareness of Austria’s contributions – which does not distinguish between the efforts of ADC and the Embassy – in Kosovo goes well beyond its relatively small budget.

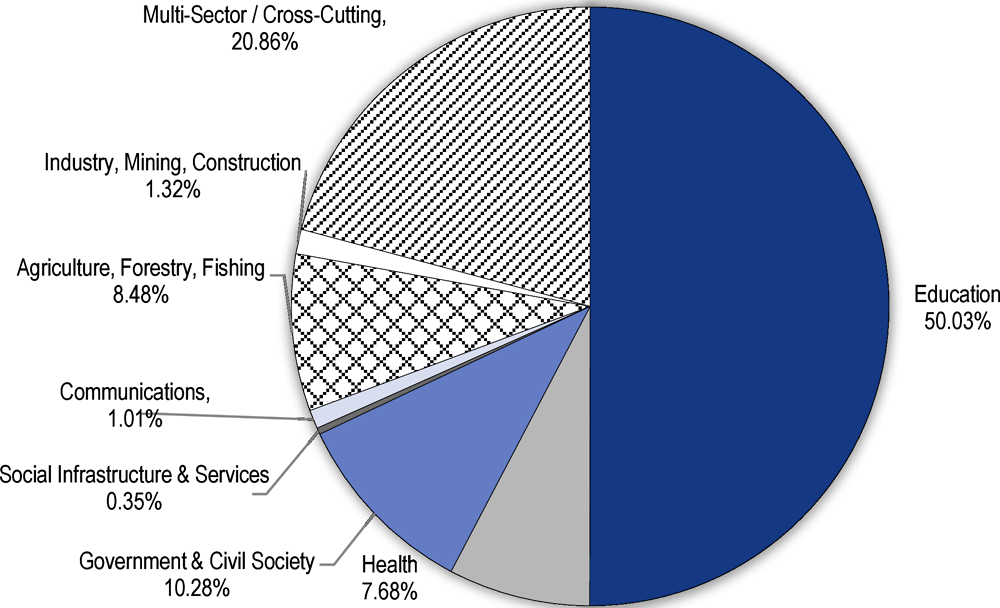

Austria also channels its bilateral development assistance to Kosovo in line with its sectoral priorities. Averaged over 2016‑17, half of Austria’s sector allocable ODA went to education in Kosovo. Around 10% was reported as targeting public authorities and civil society, and 8% as targeting agriculture, forestry and fishing (Figure C.2).

Kosovo is a recipient of Austria’s soft-loan programme, managed by the Oesterreichische Kontrollbank AG (OeKB) under the overall responsibility of the Ministry of Finance. This support (equalling USD 108 million in 2017), primarily targeting the water sector, is provided in the form of an interest subsidy, and is tied to Austrian businesses. Austria should consider whether this mode of funding is best suited to its objectives of poverty reduction, given that tying aid can raise costs and thereby undermine efficiency (Chapter 3).

Austria could work more with other bilateral partners to drive change

ADA is responsible for implementing the EU-funded Aligning Education with Labour Market Needs (ALLED) project, which supports the Kosovo Ministry of Education, Science and Technology in reforming the education system.12 Austria has few projects with other bilateral partners in Kosovo, reflecting the fact that few donors are active in each sector. While maintaining ADC’s strong sectoral focus, given its small budget and the challenging donor co-ordination environment, Austria could work more with other bilateral partners to scale up efforts and tackle underlying challenges in Kosovo. This is particularly important considering the significant contribution official transfers make to government revenues. To improve opportunities for partnership, Austria could also consider whether the limited possibility for it to commit funds over longer periods constrains its ability to enter into common arrangements with donors used to longer investments.

Figure C.2. Austrian ODA to Kosovo by sector, commitments, 2016-17 average

Source: Based on (OECD, 2019[18]), Creditor Reporting System (database) https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1.

Austria could better integrate fragility into its development co-operation

The stabilisation situation in Kosovo has significantly improved over the past 20 years. In addition to EU‑led processes aimed at normalising relations between Kosovo and Serbia, several international actors maintain a presence under the mandate of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 (1999), which Austria continues to support.13

The current ADC strategy recognises Kosovo as having aspects of fragility, and links these to Austrian development co-operation efforts on governance and institution building (ADC, 2013[16]). However, there is little evidence of governance being a strong priority (Kacapor-Dzihic, Hajdari and Van Caubergh, 2018[17]). At the same time, Austria remains the biggest non-NATO contributor of troops to Kosovo Force (400 members of the armed forces) and continues to support UNMIK with a Police Operation Liaison Officer. Austria stopped providing humanitarian assistance to Kosovo in 2015 (OECD, 2019[18]).14

Rising state capture and corruption are emerging as critical challenges in Kosovo today and are likely to pose a risk to stability. This requires a different set of tools and approaches to those used directly after the conflict in 1998 and 1999. In this regard, there remains significant room for Austria to better link its political, security and development co-operation efforts in addressing the challenges in Kosovo effectively. The use of regular political economy analysis, in addition to the ten-step process for developing ADC country strategies (Chapter 5), could usefully inform these efforts.

C.4. Organisation and management

Achieving a whole-of-government approach is proving challenging for Austria

Several Austrian stakeholders are engaged in Kosovo, contributing ODA and other official flows. For example, Austria’s contribution to private sector development includes ADA support to micro-enterprises via the Business Partnerships programme, the Chamber of Commerce’s support for Austrian companies, and potential larger investments by the Austrian Development Bank. While staff in the ADC Co-ordination Office seek complementarities across projects managed by ADA, this works less well with other actors. Given the need for Kosovo to build domestic productive capacity and increase foreign investment, and the range of support already provided by the Austrian system, there is a significant opportunity for Austria to achieve a more co-ordinated and mutually reinforcing approach to private sector development, to fill gaps, share knowledge and scale up results.

Partners also raised the need for greater coherence between ADA’s commitment to consider and address environmental challenges, and Austrian support for large infrastructure investments, citing environmental risks associated with a hydropower dam project. Full consideration of environmental and social risks may be facilitated by better linking the different parts of the Austrian system so as to improve learning and co‑ordination. Prioritising the activities pursued by all Austrian actors, including its multilateral, regional and bilateral co-operation, and other forms of financing, and presenting these in the next ADC Kosovo strategy would contribute to a more coherent whole-of-government approach. This would help to present a more comprehensive picture of Austria’s support to Kosovo, making it easier to communicate to stakeholders the breadth and depth of its activities.

This would also help identify possible domestic actions that could complement and support Austria’s long‑term and very significant development efforts in Kosovo (Chapter 1). This may include, for example, offering access to seasonal labour opportunities, and enhancing bilateral co-operation on social security.

The ADC Co-ordination Office has a good reputation, but capacity constraints bring risks

The ADC office in Pristina has four staff members, three of whom are locally engaged. These staff play a critical role in providing local context, maintaining close relationships with public authorities, implementing partners and local civil society, and ensuring institutional knowledge and memory. Staff efforts to monitor project implementation is a key strength of the ADC approach in Kosovo. In addition to managing bilateral projects, the office is also responsible for monitoring relevant projects pursued under ADC’s regional strategy for the Danube and Western Balkans area (ADC, 2016[19]).

ADC Co-ordination Offices have very limited authority, with decision making centralised in Vienna. While the office is responsible for identifying and proposing projects, approval is required by ADA; initiatives up to EUR 10 000 supported through the small projects fund can be approved in the field. Headquarters must approve all administrative expenditures for the procurement of goods above EUR 400. The limited budgetary resources available to offices also constrains their ability to offer competitive employment terms. In Kosovo, the small training budget, which has not been increased despite a rise in staffing levels, and the centralisation of official training, also limit professional development opportunities for local staff. Furthermore, each sectoral pillar being managed by just one person is a threat to operational continuity and institutional memory.

Following up on the ongoing strategic evaluation of ADA is a significant opportunity for Austria to address some of these challenges. For example, greater decentralisation of budgets to ADC Co-ordination Offices may increase flexibility in managing limited resources effectively.

ADC has strengthened its approach to some cross-cutting issues, but struggles with environment, governance and corruption risk management

Gender, environment and governance are defined in ADC’s Kosovo strategy as cross-cutting issues and themes. Gender equality and women’s empowerment are critical challenges in Kosovo, and ADC has taken especially clear action on gender. This includes institutionalising gender mainstreaming into project design, and facilitating engagement between implementing partners and gender experts through training by local organisations, such as the Kosovo Women’s Network. This has strengthened gender sensitivity among staff and contributed to the capacity building of local civil society.

As noted in the recent ADC Kosovo strategy mid-term evaluation, however, there is room to improve ADC’s approach to environment and governance (Kacapor-Dzihic, Hajdari and Van Caubergh, 2018[17]). While corruption is highlighted in the strategy as an important element of governance, this is not effectively followed up in practice. Under the rural economic development pillar of the Kosovo programme, for example, Austria provides agricultural grants to smallholder farmers via a Local Development Fund. This is an area of potentially high corruption risk in Kosovo, as highlighted by recent reports of the Kosovo National Audit Office (National Audit Office, 2019[20]), (National Audit Office, 2019[21]). Yet, during the visit, there was very little evidence that diagnostic resources such as these reports are being used by ADC staff when designing and implementing programmes. Austria should also consider whether creating parallel instruments, in this case a parallel grant instrument, is the most sustainable and constructive approach. Closer collaboration with national authorities and existing instruments is necessary to address prevailing issues and dysfunctionalities. Otherwise, parallel programmes run the risk of legitimising, albeit unwittingly, corrupt and dysfunctional processes and instruments. A more active and targeted effort to address underlying challenges around corruption, particularly in priority sectors, may be merited.

Translating the strong approach taken on gender to other cross-cutting issues, such as additional training and leveraging local expertise, could be a first step to increase staff understanding of and sensitivity to these issues. Ensuring timely training for local staff on the new Environment, Gender and Social Impact Management tool would support this approach. The planned roll out of a new risk management system by ADC will also be important to address the lack of systematic and ongoing risk management in activities, to facilitate staff abilities to better identify, assess and mitigate risks, in particular external contextual ones.

Ensuring guidance is proportionate to context-specific risks will be important.

The comprehensive programme management guidance developed by ADC is helping staff and partners in Kosovo to design and account for their activities. While implementing partners recognise that investment at the planning stage enhances project implementation, the detailed nature of ADC guidance adds to preparation time. Guidance and assessments should therefore be proportionate and targeted to context‑specific risks. The potential detrimental development impact of specific risks could also constitute important criteria when selecting areas of focus. Further, ADC guidance has been developed over extended periods, creating the risk of duplication and overlap. ADC should also ensure that all relevant guidance is translated into the working languages of the coordination offices.

C.5 Partnerships, results and accountability

Austria is seen as a flexible, constructive and reliable partner in Kosovo

Austria has built positive and productive relationships with its implementing partners in Kosovo, who appreciate the active and constructive collaboration shown by ADC staff in both Pristina and Vienna. Implementing partners also value Austria’s willingness to adapt to changes in context during project implementation, and to maintain support when partners raise controversial issues. Austria recognises the importance of engaging with and building the capacity of local civil society organisations. However, limits on the volume and duration of contracts with local organisations may be constraining this approach (Chapter 5).

ADC’s approach to evaluations and audit could be more proportionate

The recent meta-evaluation of ADA project and programme evaluations recommends revisiting guidelines, which require every project to be evaluated. A more proportionate approach, drawing on the results of monitoring by implementing partners, would enable ADC to make better use of scarce resources.

References

[19] ADC (2016), Danube Area-Western Balkans Region Regional Strategy, Austrian Development Co-operation, Vienna, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Publikationen/Strategien/Englisch/EN_Strategy_Danube_area_Western_Balkans.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[16] ADC (2013), Kosovo Country Strategy 2013-2020, Austrian Development Cooperation, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Publikationen/Landesstrategien/CS_Kosovo_2013-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[7] Atoyan, R. and J. Rahman (2017), “Western Balkans: Increasing Women’s Role in the Economy”, IMF Working Paper WP/17/194, International Monetary Fund, Washington, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/fileasset/misc/excerpts/western_balkans.pdf?redirect=true&redirect=true (accessed on 29 August 2019).

[6] EUI (2018), “Kosovo Economic Indicators at a Glance”, European University Institute, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2018/620196/EPRS_ATA(2018)620196_EN.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2019).

[11] European Commission (2019), Kosovo 2019 Report, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20190529-kosovo-report.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[25] European Commission (2016), Kosovo 2016 Report, European Commission, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/fr/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52016SC0363 (accessed on 6 September 2019).

[15] Government of Austria (2019), ODA Report 2017, Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Publikationen/ODA-Berichte/Englisch/ODA-Report_2017.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[24] Government of Kosovo (2018), Economic Reform Programme 2019-2021, Government of Kosovo, Ministry of Finance, https://mf.rks-gov.net/desk/inc/media/4FC9C8D0-8ADF-4DD1-97B8-BB2DD36150C3.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[22] Grieveson, R. (2017), Kosovo: Remittances to continue driving growth, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna, https://wiiw.ac.at/kosovo-remittances-to-continue-driving-growth-dlp-4174.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2019).

[5] IMF (2018), IMF Country Report No. 18/368: Republic of Kosovo: 2018 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/12/17/Republic-of-Kosovo-2018-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-46477.

[17] Kacapor-Dzihic, Z., R. Hajdari and A. Van Caubergh (2018), Evaluation Mid-Term Review of the Kosovo Country Strategy 2013-2020 Annexes (Volume 2), Austrian Development Agency, Vienna, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Evaluierung/Evaluierungsberichte/2017/Kosovo/Mid-Term_Review_CS_Kosovo_2013-2020_Vol_II.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[23] Kosova Democratic Institute (2019), Problematic Maintenance of Roads - Delays and Favoritism, http://kdi-kosova.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/04-Monitorimi-i-prokurimit-ne-ministrine-e-infrastruktures-Raport-ENG.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

[14] MFA (2019), Working together. For our world. Three-Year Programme on Austrian Development Policy 2019-2021, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Publikationen/3_JP/Englisch/3JP_2019-2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2019).

[21] National Audit Office (2019), Audit Report on the Municipality of Prishtina for the financial year ended 31 December 2018, National Audit Office Government of Kosovo, Pristina, http://www.zka-rks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Raporti-final-i-auditimit_2018_-Komuna-Prishtin%C3%ABs_-Eng.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2019).

[20] National Audit Office (2019), Performance Audit Report: Managing Process of Grants and Subsidies in the Agricultural Sector, National Audit Office, Government of Kosovo, http://www.zka-rks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019_05_07_Procesi_i_menaxhimit_te_granteve_dhe_subvencioneve_ne_bujqesi_ser-1.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2019).

[18] OECD (2019), International Development Statistics, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1 (accessed on 19 July 2019).

[12] OECD (2018), OECD-DAC Aid at a glance by recipient, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/aid-at-a-glance.htm (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[10] OECD (2015), Compare your country: PISA 2015 - Kosovo, https://www.compareyourcountry.org/pisa/country/kos?lg=en (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[26] UNDP (2018), Global Human Development Index, United Nations Development Programme, New York, http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[2] UNDP (2016), Kosovo Human Development Report 2016, United Nations Development Programme - Kosovo, Pristina, http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/kosovo-human-development-report-2016.

[4] UNDP (n.d.), UNDP in Kosovo, http://www.ks.undp.org/content/kosovo/en/home/countryinfo/#Challenges (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[1] United Nations (2012), Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (S/2012/818).

[8] World Bank (2018), Kosovo Overview, World Bank, Washington DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kosovo/overview#3 (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[9] World Bank (2018), The World Bank in Kosovo Country Snapshot, World Bank, Washington DC, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/423771524155944422/Kosovo-Snapshot-Spring2018.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

[28] World Bank (n.d.), Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP), World Bank, Washington DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?locations=BG-AL-BA-MK (accessed on 8 July 2019).

[27] World Bank (n.d.), Personal remittances, received (% of GDP), World Bank, Washington DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?most_recent_value_desc=true (accessed on 8 July 2019).

[3] World Bank (n.d.), World Bank Country Data - Kosovo, World Bank, Washington DC, https://data.worldbank.org/country/kosovo (accessed on 8 July 2019).

[13] WUS Austria (2007), Support to the Higher Education of Kosovo, University of Prishtina 2005-2007, WUS Austria, Graz, https://www.wus-austria.org/files/docs/Publications/Support_to_the_Higher_Education_in_Kosovo_University_of_Prishtina_2005_2007.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2019).

Notes

← 1. The 2016 Human Development Index (HDI) ranking shows that Kosovo’s HDI in 2016 was lower than that of Montenegro (0.802), Serbia (0.771) and North Macedonia, previously the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (0.747), and around equal to Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina (both ranked 85th) (UNDP, 2016[2]). Both Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina increased their positions in 2018. Kosovo was not included in the 2018 HDI ranking (UNDP, 2018[26]).

← 2. See recent reports by Transparency International and the Kosova Democratic Institute (Kosova Democratic Institute, 2019[23]) and by the European Commission (European Commission, 2019[11]).

← 3. Unemployment is the highest in the region at 32.9% in 2017 (EUI, 2018[6]), while the unemployment rate for youth (aged 15 to 24 years) is 52.7% (Government of Kosovo, 2018[24]).

← 4. In 2018, remittances accounted for 15.8% of GDP (World Bank, n.d.[27]). While around 60% of remittances come from Germany and Switzerland both of which have strong labour markets (Grieveson, 2017[22]), this remittance-driven consumption increases Kosovo’s vulnerability to external change. Foreign direct investment inflows were just 3%, below the regional average (World Bank, n.d.[28]). By comparison, foreign direct investment inflows to Albania in the same year were 8%, to North Macedonia 8.8%, Bulgaria 4.8%, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2.5%, and Serbia 8.1% (World Bank, n.d.[28]).

← 5. Kosovo’s scores in the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) were very low (the first year in which it participated in PISA, and the most recent year for which results are available).

← 6. For example, the 2016 European Commission Kosovo report noted “Kosovo needs to improve transparency in the operation of higher education institutions to address politicised recruitment” and that “Education remains a high risk sector for corruption and political influence, especially in higher education” (European Commission, 2016[25]). The most recent report indicated that political interference in higher education remains a challenge, blaming political interference on the Accreditation Agency for Higher Education’s exclusion from the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education. The report also stated that media and civil society organisations “continually expose cases of plagiarism and academic promotions based on political influence and nepotism rather than merit, often involving professors in senior management positions” and noted “A lack of transparency in recruiting teachers and managing staff remains an issue across all educational institutions” (European Commission, 2019[11]).

← 7. In April 2013, Serbia and Kosovo agreed to normalise their relations through EU-facilitated talks, which produced several subsequent agreements which the parties are currently implementing. Tensions between Kosovo-Albanians and Kosovo-Serbs remain in a limited number of areas (particularly in Mitrovicë/Mitrovica region); however the impact is mostly local (UNDP, n.d.[4]).

← 8. ODA as a share of gross national income was down from 13.6% in 2009. Over the period 2008 to 2017, Kosovo was the fourth largest recipient of official development assistance per capita among countries and territories with a population of 1 million or more (OECD, 2019[18]).

← 9. Austria supports NATO-KFOR with around 400 members of the armed forces, and the UN Mission in Kosovo with a Police Operation Liaison Officer. Information provided by the Government of Austria in the context of the peer review.

← 10. A decision was taken in 2019 to extend the current strategy, covering 2013 to 2020, for one additional year, to 2021.

← 11. Key projects include Higher Education, Research and Applied Science (HERAS) and the EU Aligning Education with Labour Market Needs (ALLED) project, which is now in its second phase.

← 12. For more information see the project website: http://www.alledkosovo.com/our-mission/.

← 13. This includes UNMIK, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which retains the status of UNMIK's pillar for institution building, and the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), which has operational responsibility in the area of rule of law. KFOR also derives its mandate from Security Council resolution 1244 (1999) as well as the Military-Technical Agreement between NATO, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia. While KFOR’s original objectives were to deter renewed hostilities, demilitarise the Kosovo Liberation Army, support the international humanitarian effort and co‑ordinate with the international civil presence, its current focus is on maintaining a safe and secure environment and freedom of movement.

← 14. In 2016-17, only Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States provided small amounts of humanitarian aid, totalling less than USD 1 million per year (OECD, 2019[18]).