The SME Policy Index 2020 contains scores at the level of dimensions and sub-dimensions and uses two separate scoring methodologies depending on the dimensions being assessed: one for the human capital dimensions (Pillar B – Entrepreneurial human capital) and another for the remaining dimensions. When relevant (e.g. at country profile level), the Index also shows 2020 scores according to 2016 methodology, to maintain comparability of the scores disregarding additions of new sub-dimensions, as described below. For more detailed information on the assessment framework and process, please refer to the chapter “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process”.

SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020

Annex A. Methodology for the Small Business Act assessment

Scoring methodology

Scoring methodology

For all other dimensions, the detailed questionnaires comprising approximately 500 questions, filled out by national governments and independent experts, have been used. These questionnaires allow more precise information to be obtained and cross-checked, in particular on the actual implementation of policies and measures.

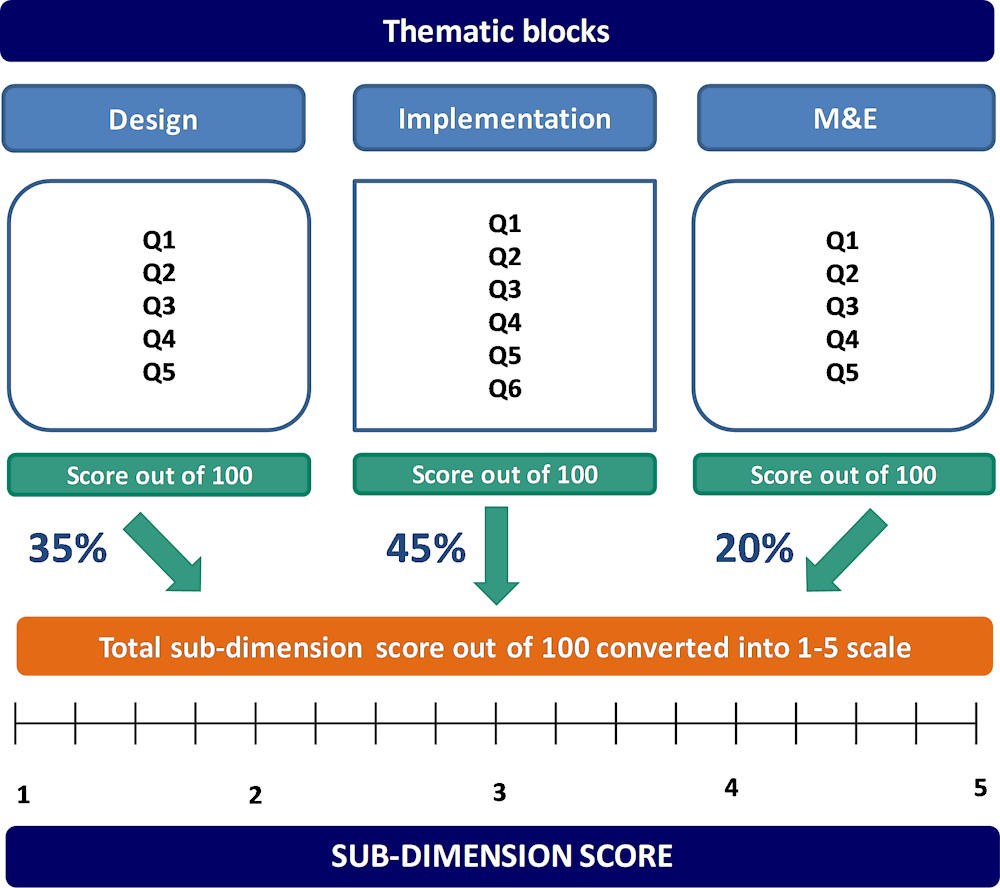

Like the 2016 assessment, the 2020 questionnaires have been structured by dimensions and sub-dimensions, the sub-dimensions having been divided into thematic blocks, each with their own set of questions (Table A.1). These thematic blocks are typically broken down into the three components or stages of the policy process (design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation), with some deviations in certain dimensions. This approach allows for better monitoring of policy progress and enhances the depth of policy recommendations, while addressing systemic policy issues in a more detailed manner.

Recent change in the methodology for the Entrepreneurial human capital dimensions

For this assessment, the methodology for the three human capital sub-dimensions – entrepreneurial learning, women’s entrepreneurship and enterprise skills – has been harmonised with the remaining dimensions. Previously, these dimensions were assessed using 5-level qualitative indicators. Moving to the questionnaire – with its binary (yes/no), multiple-choice and open questions – has harmonised the assessment methodology across all the SBA dimensions (the other dimensions were first assessed in this way in 2016). Thus, comparison of the scores on the human capital dimensions between the 2016 and 2020 assessments need to be made with caution because of this change.

Table A.1. Example of thematic blocks for the "Institutional framework" sub-dimension

|

Design |

Implementation |

Monitoring & evaluation |

|---|---|---|

|

Is there a multi-year SME strategy in place? |

Has budget been mobilised for the action plan? |

Are there any monitoring mechanisms in place for the implementation of the strategy? |

Each questionnaire contains two types of questions: 1) core questions to determine the assessment score; and 2) open questions to acquire further descriptive evidence.1 Each of the core questions (Q1, Q2, Q3, etc.) is scored equally within the thematic block. For binary questions, a "Yes" response is awarded full points and a "No" response receives zero points. For multiple choice questions, scores for the different options range between zero and full points, depending on the indicated level of policy development.

The core questions are scored individually and then added to provide a score for each thematic component. Scores are initially derived as percentages (0-100) and then converted into the 1-5 scale (Figure A.1). Scores for the thematic blocks are then aggregated to attain a score for the sub-dimension, with each component being assigned a weight based on expert consultation. In general terms, a 35-45-20 percentage split has been attributed to emphasise the importance of policy implementation. The sub-dimensions are then aggregated using expert-determined weightings (based on the relative significance of each policy area) to reach an overall 1-5 level per dimension (see below).

Figure A.1. Questionnaire scoring at the level of sub-dimensions

Since 2016, several dimensions in the assessment have been revised in order to assess a broader range of SME policies (e.g. promoting second chance, policy framework for non-technological innovation and diffusion of innovation) and address potential gaps in measurement (e.g. trade facilitation indicators) as well as to undertake a minor reorganisation and streamlining of the sub-dimensions. The weightings of the sub-dimensions have been adjusted to allow for these additions whilst maintaining comparability with the 2016 assessment as much as possible.

Moreover, the SME Policy Index 2020 comprises an additional set of scores based on the 2016 methodology in order to track progress countries would have made had the assessment framework not changed (i.e. had the new sub-dimensions not been added). These scores are shown in the respective country profiles and the “Overview” chapter. An. An overview of the changes to the dimensions is provided in Table A.2.

Table A.2. Overview of changes to the SBA assessment sub-dimensions

|

Dimension |

Changes introduced since the 2016 assessment |

|

Bankruptcy and second chance |

Sub-dimension on bankruptcy prevention measures added. |

|

Operational environment |

Sub-dimensions on business licencing and tax compliance procedures for SMEs introduced. The sub-dimension on digital government was expanded to take into account the introduction of e-government services. |

|

Access to finance |

Financial literacy sub-dimension expanded to encourage SMEs to improve financial reporting and IFRS adherence. OECD SME financing scoreboard data included to expand the core indicators assessing SME access to finance. |

|

Standards and technical regulations |

Overall co-ordination and general measures – previously a building block – is now a sub-dimension. Other existing building blocks were fully restructured into the new sub-dimension Approximation with the EU Acquis. Sub-dimension on SME access to standardisation was added. |

|

Innovation policy |

Policy framework for innovation expanded through the sub-dimension on policy framework for non-technological innovation. |

|

Internationalisation |

Sub-dimensions on trade facilitation measurement with the use of OECD indicators and on SME use of e-commerce added to better capture internationalisation of SMEs. |

Supplementary data

The 2020 SME Policy Index has also tried to supplement the formal assessment framework with additional data and statistics. While it was not incorporated into the scores (except for the Internationalisation Dimension, OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators), this information was used to support the policy narrative with additional details on policy outcomes and SME perceptions. Two types of additional data have been collected:

Structural business statistics and business demography data (on enterprise birth, death and survival rates) were requested from the six national statistics offices, along with statistics on policy outputs related to the SBA policy dimensions based on the EU SBA fact sheets, which benchmark EU countries based on the principles of the SBA. Remaining gaps in data collection and inconsistencies in data collection methodologies in the EaP countries prevent the regional comparison of statistics. However, structural and business demography statistics are included in the country profiles.

Data from international databases (e.g. World Bank’s Doing Business, World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index and Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index) were also instrumental in completing information gaps and assessment findings for the Level Playing Field pillar, in particular on the contract enforcement and dispute resolution, and business integrity dimensions.

In addition, the country profiles include an in-depth analysis of the key reforms achieved so far reflecting on the 2016 recommendations, key challenges still facing the SME sector, as well as detailed recommendations to help EaP countries implement and monitor reforms. Profiles do not only present the main findings of the SBA assessment, but also cover broader macroeconomic and business environment challenges affecting SMEs and SME policy making that may not be directly captured by the different SBA dimensions. Furthermore, the “Way forward” section of the country profiles includes a detailed reform roadmap outlining each country’s short-, medium- and long-term policy priorities.

Note

← 1. Core questions include: 1) binary or yes-no questions (e.g. “Does a legal definition of SMEs exist in your country?”); and 2) multiple choice questions (e.g. “Does a multi-year SME strategy exist?”, for which various responses are available, e.g. “Strategy is in the process of development”, “Draft strategy exists but yet not approved by the government”, “Strategy exists, has been approved by the government and is in the process of implementation”, or “There is no strategy in development”).

In either case, countries are requested to provide evidence (source and/or explanation) for the answers. Open questions (e.g. “What is the budget for the SME implementation agency?”; “How many people work in the agency?” or “How many ministries are represented in the governance board?”) are used to provide further details on the responses to the core questions, but are not directly scored.