This brief focuses on the contribution of migrant doctors and nurses to OECD health systems and how OECD countries have adapted the recognition of foreign credentials to mobilise additional doctors and nurses with foreign degrees in response to COVID‑19. It also highlights the potential impact on countries of origin, some of which were already facing severe shortages of skilled health workers before the COVID‑19 pandemic, and the need for a global response to the global health worker shortage.

Contribution of migrant doctors and nurses to tackling COVID-19 crisis in OECD countries

Abstract

Foreign doctors and nurses are key assets for health systems in many OECD countries

The availability of a sufficient number of skilled and motivated health workers is central to the performance of any health system, as illustrated once more by the current COVID‑19 pandemic. Along with bringing into the spotlight the important role and dedication of frontline health workers, the COVID‑19 crisis further highlights the deeply embedded challenge of staff shortages as well as the significant contribution that migrant doctors and nurses make to the health workforce in many OECD countries.

During the #COVID‑19 pandemic, many OECD countries have recognised #migrant health workers as key assets and introduced policies to help their arrival and the recognition of their qualifications

While the number of medical and nursing graduates has increased significantly in the majority of the OECD countries over the past two decades, the shares of foreign-trained or foreign-born doctors and nurses have also continued to rise (OECD, 2019[1]). As a result, across the OECD countries, nearly one‑quarter of all doctors are born abroad and close to one‑fifth are trained abroad. Among nurses, nearly 16% are foreign-born and more than 7% are foreign-trained (Table 1).

The share of foreign-trained doctors ranges from less than 3% in a number of OECD countries, to around 40% in Norway, Ireland, or New Zealand, and to nearly 60% in Israel. However, not all of these foreign-trained doctors are foreigners. In some of the main destination countries (e.g. Israel and Norway), a large number (more than half in the case of Norway) are people born in the country who went to study abroad before coming back (OECD, 2019[2]). In the majority of OECD countries, the share of foreign-trained nurses is below 5%, but in Australia, Switzerland, and New Zealand, this share goes up to around 20 to 25%.

As for doctors born abroad, their share ranges from less than 2% in the Slovak Republic to more than 50% in Australia and Luxembourg. The share of foreign-born among nurses is insignificant in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, but over 30% in Switzerland, Australia and Israel. In nearly all OECD countries, the number of doctors or nurses born abroad is higher than the number of those trained abroad, reflecting the fact that destination countries provide education to migrants who may have moved at an early age or to pursue their studies. Also, the migration of doctors and nurses takes place against a backdrop of larger migration trends, including increasing overall highly skilled migration. Indeed the share of migrants in the overall tertiary educated OECD population (15+) is on average about 20%, as compared to 24% for foreign-born physicians (d’Aiglepierre et al., 2020[3]).

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, many of the OECD countries already reliant on migrant health workers have further recognised them as key assets, and implemented additional policy measures to ease their entry and the recognition of their professional qualifications.

Migrants care for us – 16% of nurses in the OECD are foreign born

Table 1. Number and share of migrant doctors and nurses working in OECD countries

|

|

Migrant doctors |

Migrant nurses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

foreign-trained (of which natives)1 |

foreign-born |

foreign-trained (of which natives)1 |

foreign-born |

|||||

|

|

number |

% of total |

number |

% of total |

number |

% of total |

number |

% of total |

|

Australia |

29 000 (333) |

32.1 (0.4) |

47 154 |

53.9 |

52 860 (815) |

18.4 (0.3) |

104 272 |

35.3 |

|

Austria |

2282 (399) |

6.0 (1.0) |

5 2 251 |

14.2 |

.. |

.. |

18 779 |

19.6 |

|

Belgium |

8061 |

12.1 |

6 174 |

15.7 |

7889 |

3.7 |

15 281 |

11.2 |

|

Canada |

24 587 |

24.6 |

38 780 |

38.5 |

32 346 |

8.1 |

92 530 |

24.4 |

|

Chile |

11 038 (2030) |

22.7 (4.2) |

.. |

.. |

1135 (196) |

2.0 (0.4) |

9532 |

7.9 |

|

Czech Republic |

3232 |

7.4 |

4 110 |

9.7 |

.. |

.. |

2600 |

2.7 |

|

Denmark |

2111 |

9.2 |

3 904 |

21 |

1034 |

1.8 |

4 1732 |

6.7 |

|

Estonia |

262 |

3.9 |

742 |

14 |

20 |

0.1 |

1304 |

14.3 |

|

Finland |

.. |

.. |

1917 |

9.5 |

.. |

.. |

2722 |

3.6 |

|

France |

26 048 (715) |

11.5 (0.3) |

31 2271 |

15.7 |

20 757 |

2.9 |

40 329 |

6.6 |

|

Germany |

419 343 |

11.9 |

78 907 |

20.2 |

71 000 |

7.9 |

217 998 |

16.2 |

|

Greece |

836742 (7 832) |

12.8 (12.0) |

2 103 |

4.2 |

451 (416) |

2.5 (2.3) |

3221 |

6.1 |

|

Hungary |

2614 (400) |

8.0 (1.2) |

3 761 |

11.2 |

953 (17) |

1.5 (0.0) |

2238 |

4 |

|

Ireland |

9583 |

41.6 |

5 565 |

41.1 |

.. |

.. |

13 778 |

26.1 |

|

Israel |

17 133 (6 963) |

57.9 (23.5) |

13 753 |

48.7 |

5078 (2 125) |

9.3 (3.9) |

19 946 |

48 |

|

Italy |

3378 (1 443) |

0.8 (0.4) |

10 163 |

4.3 |

21 561 (458) |

4.8 (0.1) |

41 935 |

10.7 |

|

Latvia |

477 |

6 |

1 197 |

17.4 |

274 |

3.2 |

1334 |

16.6 |

|

Lithuania |

72 |

0.5 |

.. |

.. |

113 |

0.4 |

.. |

.. |

|

Luxembourg |

.. |

.. |

1 103 |

55 |

.. |

.. |

900 |

29.1 |

|

Netherlands |

1336 (483) |

2.2 (0.8) |

11 247 |

17.1 |

978 (249) |

0.5 (0.1) |

11 643 |

6.2 |

|

New Zealand |

7228 |

42.5 |

.. |

.. |

13 115 |

26.2 |

.. |

.. |

|

Norway |

10 248 (5 492) |

40.3 (21.6) |

5 082 |

22.7 |

6065 (1 121) |

8.7 (1.2) |

12 418 |

12.1 |

|

Poland |

2549 |

1.9 |

.. |

.. |

162 |

0.1 |

.. |

.. |

|

Portugal |

6229 (2 865) |

12.2 (5.6) |

3 508 |

9.9 |

1212 |

1.8 |

6637 |

10.8 |

|

Slovak Republic |

.. |

.. |

153 |

1.2 |

.. |

.. |

186 |

0.4 |

|

Slovenia |

1085 (147) |

16.9 (2.3) |

.. |

.. |

27 |

0.4 |

.. |

.. |

|

Spain |

.. |

.. |

25 8 751 |

13.7 |

.. |

.. |

10 302 |

4 |

|

Sweden |

14 195 (2 117) |

34.8 (5.2) |

15 372 |

30.5 |

3269 |

3 |

14 455 |

13.1 |

|

Switzerland |

12 570 |

34.1 |

23 438 |

47.1 |

18 403 (1 387) |

25.9 (2.0) |

32 264 |

31.6 |

|

Turkey |

262 (223) |

0.2 (0.2) |

.. |

.. |

456 (397) |

0.3 (0.3) |

.. |

.. |

|

United Kingdom |

51 115 |

29.2 |

86 866 |

33.1 |

104 365 (294) |

15.1 (0.0) |

151 815 |

21.9 |

|

United States |

215 630 |

25 |

289106 |

30.2 |

196 2303 |

6.7 |

691 134 |

16.4 |

|

OECD Total |

587 933 |

18.2 |

716 432 |

24.2 |

558 343 |

7.4 |

1523 726 |

15.8 |

|

27 countries |

26 countries |

22 countries |

27 countries |

|||||

Note: Most recent data is from 2017/18 (or nearest year) for foreign-trained and 2015/16 for foreign-born doctors/nurses. Doctors/nurses whose place of birth is unknown are excluded from the calculation. Foreign-trained doctors are defined as those who have completed at least their first medical degree abroad. 1. At present, only 14/11 OECD countries report data on the number of foreign-trained but native-born doctors/nurses. 2. Limited data coverage. 3. Data are based on estimates and refer only to registered nurses.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2019; DIOC 2015/16; LFS 2015/16.

Mobilising foreign trained doctors and nurses in response to COVID‑19

In response to COVID‑19, a number of OECD countries (or states and provinces in the United States and Canada, respectively) have taken action to enable migrant health professionals to help meet the surge in demand for health care. These actions may take the form of facilitating renewal of working authorisation or recruitment, temporary and/or restricted licensure, fast-track processing of recognition of foreign qualifications or access to some jobs in the health sector.

International mobility and recruitment of foreign health workers

In April 2020, the European Commission called on “Member States to facilitate the smooth border crossing for health professionals and allow them unhindered access to work in a healthcare facility in another Member State” C(2020) 2153.

Most OECD countries have exempted health professionals with a job offer from travel bans and some still process their visa applications (including the United States).

In the United Kingdom, doctors, nurses and paramedics with visas due to expire before 1 October 2020 will have them automatically extended for one year.

Work authorisations

In Chile, in health emergencies, the national health service can hire foreign health professionals even if they have not their qualification formally recognised.

In Australia, international nursing students can now work more than 40 hours every two weeks to alleviate pressure on the workforce.

In France, non-licensed foreign-trained health professionals can work as support staff in non-medical occupations.

Spanish ministries have launched urgent, coordinated action for the immediate hiring of foreign health workers willing to work in Spain. About 400 people have been recruited as of end April 2020.

Facilitating recognition of foreign qualifications

A number of OECD countries have decided to expedite current applications for the recognition of foreign qualifications of health professionals (e.g., Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg), or to facilitate procedures (e.g., reduced language test in Germany, no in person meeting in Lithuania, adopt fee waivers in Ireland).

In Canada, in the province of Ontario, international medical graduates (IMG) who have passed their exams to practise in Canada or have graduated from school in the past two years can apply for a supervised 30‑day medical licence (Supervised Short Duration Certificate) to help fight COVID‑19. In the province of British Columbia, IMG with at least two years of postgraduate training and who have completed Licentiate of the Medical Council of Canada qualifying exams can work as associate physicians under the supervision of a fully certified doctor.

Italy has adopted a decree that enable temporary licensing of foreign trained health professionals.

In Germany, in Bavaria, foreign doctors may be offered permission to work as assistants for one year. Saxony has also urged foreigners with a medical background to identify themselves but has not mobilised them so far.

In the United States, the State of New York gives access to IMG to a limited permit with one year of approved postgraduate training instead of three (EO 202.10). Physicians licensed in other states and Canada can practice (EO 202.18). Similar measures have been adopted by the State of Massachusetts (2 years of postgraduate resident medical training instead of 3) while New Jersey has created a pathway for foreign-licensed physicians to get a temporary emergency license to practice medicine. In Utah, foreign medical graduates do not have to repeat their residencies if they practiced in Australia, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, South Africa, Hong Kong, China, or Singapore. In other states such as California, Colorado or Nevada, authority has been delegated to the Chief of medical services to provide waivers regarding licensing of health professionals without specific mention of IMG (https://web.csg.org/covid19/executive-orders/).

OECD-WHO-ILO International Platform on Health Worker Mobility

Well before the COVID 19 pandemic, the UN Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth1 (ComHEEG) highlighted the projected global shortfall of 18 million health workers, primarily in low- and lower-middle income countries, by 2030. Their report emphasised that investment in health workers was one part of the broader objective of strengthening health systems and social protection and essentially constitutes the first line of defence against international health crises. By encouraging the creation of new jobs in the health sector globally, the report suggested a unique opportunity both to respond to the growing global demand for health workers and to address the projected shortages

The OECD-WHO-ILO “International Platform on Health Worker Mobility”, one of the immediate actions recommended in the ComHEEG report, aims at maximising benefits from international health worker mobility through advancing the understanding of the mobility and enhancing international dialogue on existing and innovative policy approaches to better and more ethically manage health worker migration. Only through better data and a well-informed multi-stakeholder dialogue, will it be possible to maximise the benefits and mitigate possible adverse effects from health labour mobility as well as to inform the domestic health workforce development plans designed to achieve a sustainable health workforce, which will be critical when the focus shifts to strengthening health systems to avoid future crises.

1. Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250047/9789241511308-eng.pdf?sequence=1

The main countries of origin of migrant doctors and nurses working in OECD countries vary considerably

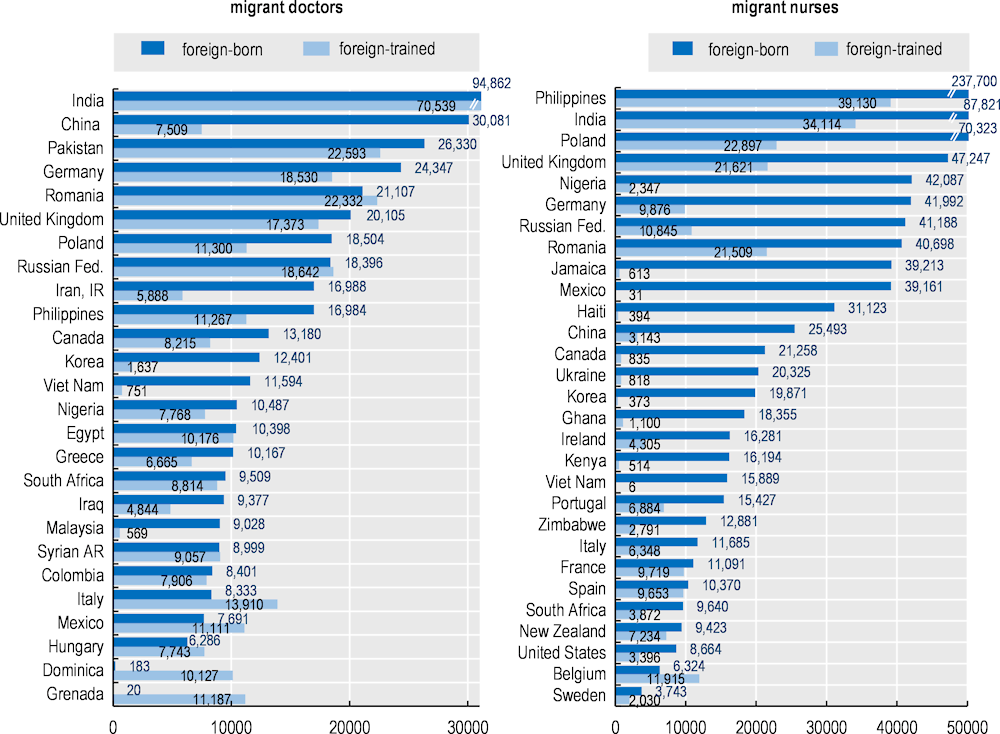

Regarding the countries of origin, around a third all foreign-born or foreign-trained doctors or nurses working in OECD countries originate from within the OECD area and another third from non-OECD upper-middle-income countries. The lower-middle-income countries account for around 30% and low-income countries for 3 to 6% of migrant doctors or nurses. The top 20 countries of origin comprise non-OECD as well as the OECD or EU countries, and represent all income levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Top 20 countries of origin for foreign-trained or foreign-born doctors and nurses working in the OECD area

Note: Most recent data is from 2017/18 (or nearest year) for foreign-trained and 2015/16 for foreign-born doctors/nurses. For some countries of origin, the number of home-trained nurses working in the OECD area might be underestimated due to data gaps in large countries of destination such as the United States, the United Kingdom, or Germany. Doctors/nurses whose place of birth is unknown are excluded from the calculation. Foreign-trained doctors are defined as those who have completed at least their first medical degree abroad.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2019, DIOC 2015/16 and LFS 2015/16.

Impact on countries of origin

Increasing international mobility and the emergence of shortages of health professionals in many OECD countries and worldwide have raised concerns about international interdependency in the management of health human resources. As OECD countries strive to respond to their own needs, there is indeed a risk for shortages to be exported within and beyond the OECD area, putting excessive burden on the poorest countries in the world (OECD, 2007[4]; OECD, 2008[5]; OECD, 2015[6]; OECD, 2016[7]).

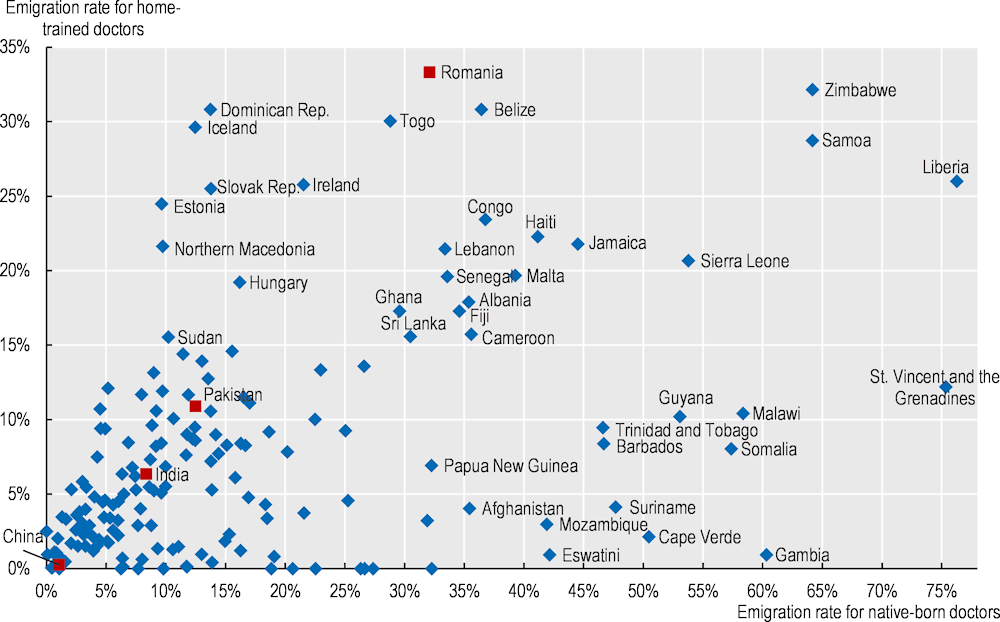

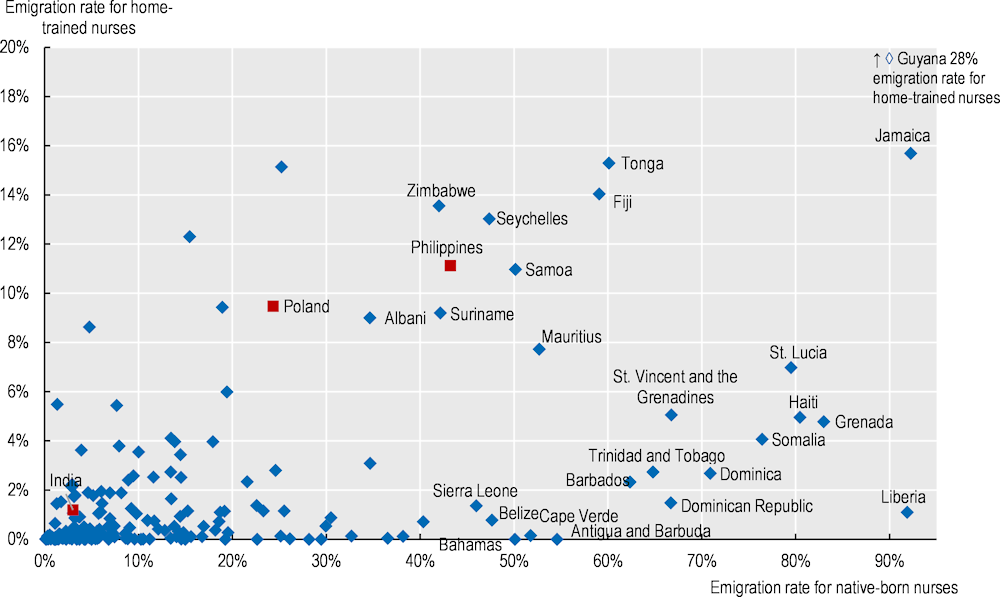

Emigration rates, defined as the number of doctors or nurses born or trained in a given country but working abroad to the total number of doctors or nurses originating from that country, illustrate the scope of the phenomenon. Generally, in the largest countries of origin, migration to (other) OECD countries remains moderate, but in some smaller countries, some of which have relatively weak health systems, emigration can be substantial (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Among the three main countries of origin for migrant doctors working in OECD countries, emigration rates for home-trained or native-born doctors are low (India) or very low (China), but not in Romania with an emigration rate of about one‑third of all home-trained and native-born doctors. Emigration rates of between one‑third and one‑half, for doctors either born or trained in a country, are found in 20 out of the 188 countries of origin, predominantly in Africa and Latin America, but also in Europe (e.g. in Malta and Albania), Middle East, and Western Pacific. Lower but still substantial emigration rates of around 20% to 30% for home-trained doctors are also found in a number of European countries such as Iceland, Ireland, the Slovak Republic and Estonia (Figure 2).

For 10 other countries of origin – again in Africa and Latin America – the emigration rates for native-born doctors exceed 50%, which means that more doctors born in these countries are working in the OECD area than in their country of origin. For a number of Caribbean countries (Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, as well as Saint Kitts and Nevis – all excluded from Figure 2), emigration rates for home-trained doctors are as high as 80 to 99%. However, these four countries are renowned international medical education hubs training predominantly fee-paying foreign students from the United States and Canada. Despite their small population, the size of their medical schools rivals and sometimes exceeds that of the largest medical schools in the United States.

Figure 2. Countries of origin – top 25 emigration rates for home-trained or native-born doctors

Note: Data for 188 countries of origin. Data on native-born doctors is from 2015/16. Data for home-trained doctors is from 2017/18 (or nearest year). Emigration rates are computed as follows: Xi = number of foreign-born or foreign-trained doctors working in OECD countries born in country i; Yi = number of doctors working in country i; emigration rate = Xi / (Xi + Yi).

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2019, DIOC 2015/16 and LFS 2015/16 for numbers of foreign-trained and foreign-born doctors; OECD Health Statistics 2019 and WHO Global Health Observatory 2019 for number of doctors working in countries of origin.

For most countries of origin, the emigration rate for home-trained or native-born nurses are generally much lower than for doctors (Figure 3). Among the three main countries of origin, the emigration rates are very low for India, but more significant for Poland and the Philippines, especially considering the native-born nurses. For some countries of origin, however, the emigration rates for foreign-trained nurses might be underestimated due to data gaps in large countries of destination such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Among other main countries of origin for migrant nurses, Jamaica stands out with the highest and second highest emigration rates for native-born and home-trained nurses, respectively.

Figure 3. Countries of origin – top 25 emigration rates for home-trained or native-born nurses

Note: Data for 188 countries of origin. Data on native-born nurses is from 2015/16. Data for home-trained nurses is from 2017/18 (or nearest year). Emigration rates are computed as follows: Xi = number of foreign-born or foreign-trained nurses working in OECD countries born in country i; Yi = number of nurses working in country i; emigration rate = Xi / (Xi + Yi). For some countries of origin, the emigration rates for foreign-trained nurses might be underestimated due to data gaps in large countries of destination such as the United States, the United Kingdom, or Germany.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2019, DIOC 2015/16 and LFS 2015/16 for numbers of foreign-trained and foreign-born nurses; OECD Health Statistics 2019 and WHO Global Health Observatory 2019 for number of nurses working in countries of origin.

For 20 out of the 188 countries – mostly in Africa and Latin America, the emigration rates for native-born nurses exceed 50%. Among these countries, Guyana stands out with the highest emigration rate (28%) also for home trained nurses. Emigration rates for native-born nurses of between one‑third and one‑half are found for another 10 countries of origin, in Africa, Latin America, Western Pacific, and Europe (Albania).

However, the low density of doctors and nurses in many low-income countries shows that the global health workforce crisis goes far beyond the migration issue. International migration is neither the main cause nor would its reduction be the solution to the worldwide health human resources crisis, although it exacerbates the acuteness of the problems in some countries.

While the international recruitment of foreign health workers has been considered as a quick fix to address skills shortages in some countries during the COVID‑19 crisis, it cannot be seen as an efficient or equitable solution. First, it does not address more structural imbalances between the supply of and the demand for health professionals. Moreover, given the global nature of the pandemic, it deprives sending countries – often characterised by weak health systems – with essential health workers when facing a major epidemic. A collective response is needed to address in a sustainable way the global shortage of health workers that the COVID‑19 pandemic has once again revealed.

Policy responses to the global health workforce shortage

Implement to its full scope the “WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel” https://www.who.int/hrh/migration/code/WHO_global_code_of_practice_EN.pdf.

Reinforce international co-operation to address the global shortage of health workers.

Increase training capacity in receiving countries and improve retention into the health workforce to reduce domestic shortages and misdistribution by geographic area or specialties, to avoid becoming dependent on international recruitments.

Ensure that migrant health workers have equal working conditions with other health workers and acknowledge their contribution to the functioning of national health systems, including in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Address the risk of “brain waste” by streamlining procedures for the recognition of foreign qualifications and reinforcing the offer for bridging courses where appropriate.

Recognise the opportunities associated with the internationalisation of medical education but align the number of internship and specialty training places to allow international students to complete their training.

Reinforce international co-operation, notably Overseas Development Assistance and technical assistance, to help less advanced countries build up a sufficient health workforce and to strengthen their health systems, thereby mitigating factors that are pushing health professionals to leave.

References

[3] d’Aiglepierre, R. et al. (2020), “A global profile of emigrants to OECD countries: Younger and more skilled migrants from more diverse countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 239, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0cb305d3-en.

[8] OECD (2020), “Beyond containment: Health systems responses to COVID-19 in the OECD”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (Covid-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/beyond-containment-health-systems-responses-to-covid-19-in-the-oecd-6ab740c0/.

[9] OECD (2020), “Flattening the COVID-19 peak: Containment and mitigation policies”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (Covid-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/flattening-the-covid-19-peak-containment-and-mitigation-policies-e96a4226/.

[10] OECD (2020), “Testing for COVID-19: A way to lift confinement restrictions”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (Covid-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/testing-for-covid-19-a-way-to-lift-confinement-restrictions-89756248/.

[1] OECD (2019), “Recent trends in international mobility of doctors and nurses”, in Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5ee49d97-en.

[2] OECD (2019), “Recent trends in internationalisation of medical education”, in Recent Trends in International Migration of Doctors, Nurses and Medical Students, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b74c678d-en.

[7] OECD (2016), “Trends and policies affecting the international migration of doctors and nurses to OECD countries”, in Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264239517-7-en.

[6] OECD (2015), “Changing patterns in the international migration of doctors and nurses to OECD countries”, in International Migration Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2015-6-en.

[5] OECD (2008), The Looming Crisis in the Health Workforce: How Can OECD Countries Respond?, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264050440-en.

[4] OECD (2007), International Migration Outlook 2007, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2007-en.

Contacts

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Jean-Christophe DUMONT (✉ jean-christophe.dumont@oecd.org)

Karolina SOCHA-DIETRICH (✉ karolina.socha-dietrich@oecd.org)