This chapter examines the legal frameworks for investment protection and dispute resolution that apply to investors in Indonesia. It focuses on several core investment policy issues – the non-discrimination principle, protections for investors’ property rights and mechanisms for resolving investment disputes – under Indonesian law and Indonesia’s investment treaties. It also addresses the government’s recent policy approaches to data protection and cybersecurity, tackling corruption and public sector reforms. It takes stock of recent achievements, identifies key remaining challenges and proposes recommendations to address them. In terms of investment treaty policy, this chapter provides an overview of Indonesia’s investment treaties, analyses the main substantive protections and investor-state dispute settlement provisions in these treaties and identifies considerations for possible policy reforms.

OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Indonesia 2020

4. Investment protection and dispute resolution

Abstract

Summary and main recommendations

Rules that create restrictions on establishing and operating a business in Indonesia, discussed in Chapter 3, are an important part of the broader legal framework affecting investors. Protections for property rights, contractual rights and other legal guarantees, as well as efficient enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms, are equally important elements.

Indonesian law provides a number of core protections to investors relating to non-discrimination, expropriation and free transfer of funds. Most of them are found in Law 25/2007 concerning Investment (the Investment Law) and have not changed significantly in recent years. These protections are generally in line with similar provisions found in other regional investment laws and provide clear rights that should instil investor confidence to the extent that enforcement mechanisms are also seen to be robust. Some incremental improvements may be possible to bring these provisions closer in line with international good practices, including further specification of the provisions on expropriation.

Clarifications may also improve the existing legal frameworks to protect investors’ intellectual property and land tenure rights, which are comprehensive in many respects. The government has not made significant updates to land laws in Indonesia in several decades. While foreigners are now able to own land, these rights are relatively limited and interactions between formal land laws and customary land rights remain complex and subject to interpretation. Initiatives to accelerate land registration and the use of electronic databases for land administration have yielded promising initial results but sustained momentum is needed for these changes to be durable in the long term. Investors also report some issues with the legal framework for intellectual property rights, notably with respect to restrictive patentability criteria, but in the main these laws are well-developed, have been periodically improved through amendments and comply with international standards in five core areas: trademarks, patents, industrial designs, copyrights and trade secrets. Some problems nonetheless persist in practice. Online piracy and counterfeiting are widespread, and efforts to implement and enforce laws is poor or inconsistent in several areas. The government is pursuing a range of different initiatives that seek to address these well-known shortcomings.

In terms of dispute resolution, the Indonesian courts have a reasonable record concerning the rule of law and contract enforcement when compared to similar economies. Despite important reforms to establish an independent judiciary and improve court services, however, some stakeholders still cite concerns with the lack of transparent and fair treatment in the Indonesian court system. The effectiveness of the courts is hampered by some long-standing negative perceptions. For these reasons, many firms prefer to use alternative dispute resolution rather than litigation to settle their disputes. Law 30/1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution provides a solid framework to support arbitration in Indonesia and works reasonably well in practice. The government is not considering any major reform proposals in this area but it may wish to investigate amending some provisions of the law to improve legal certainty.

Other areas attracting attention from the top levels of government are data protection and cybersecurity, the fight against corruption and public sector reforms. The government has taken significant strides towards making cybersecurity a national policy priority. It established a national cybersecurity agency in 2017 and stepped up its international engagement on these issues, but there is still no overarching regulatory framework in Indonesia for cybersecurity or data protection. Fighting corruption in all levels of society has also been a top priority for many years. The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has played a major role in building public awareness and trust through impressive results. A wide range of public sector reforms introduced in recent years to improve transparency, reduce bureaucracy, and encourage public engagement in the policy cycle will also contribute to strengthening public integrity. Enduring concerns regarding corruption are deep-rooted, however, and may only be overcome in the long term, which the government recognises and seeks to address.

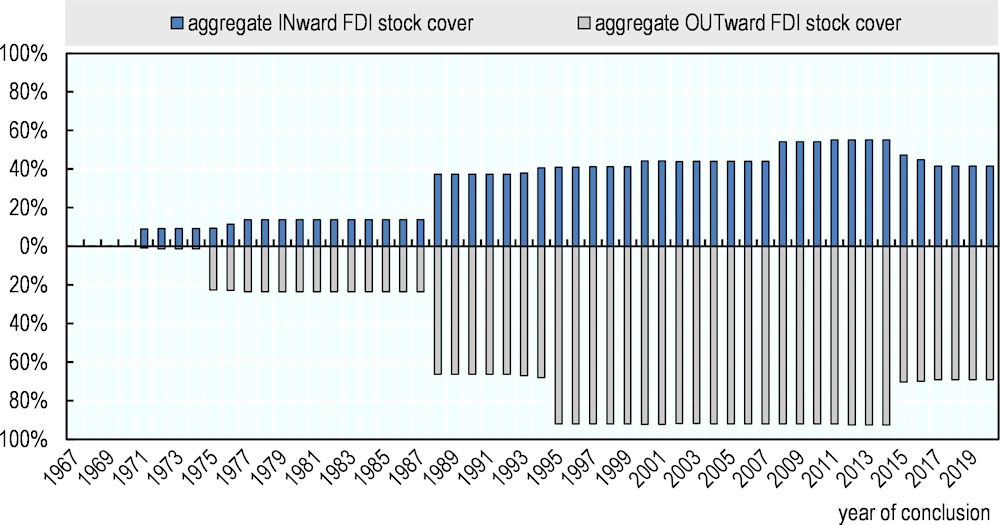

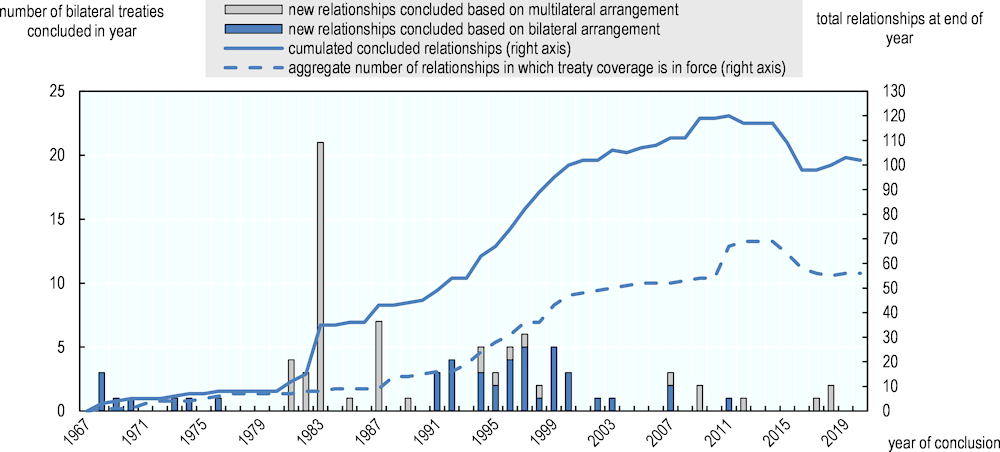

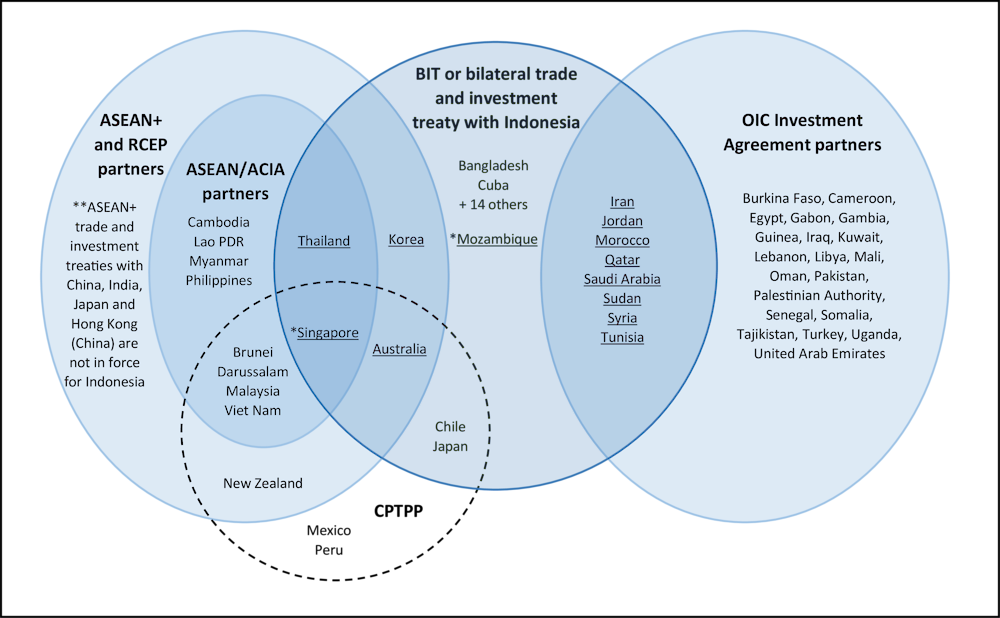

The government has also substantially revised its investment treaty policies in recent years. Indonesia’s investment treaties grant protections to certain foreign investors in addition to and independently from protections available under domestic law to all investors. Domestic investors are generally not covered by these treaties. Indonesia is a party to 37 investment treaties in force today. Like investment treaties signed by many other countries, these treaties typically protect investments made by treaty-covered investors against expropriation and discrimination. Provisions requiring “fair and equitable treatment” (FET) are also common, providing a floor below which government behaviour should not fall. While there are some significant recent exceptions, investment treaties often enforce these provisions through access to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms that allow covered investors access to impartial international arbitration that awards monetary damages in an effort to depoliticise such disputes.

Investment protection provided under investment treaties can play an important role in fostering a healthy regulatory climate for investment. Expropriation or discrimination by governments does occur. Investors need some assurance that any dispute with the government will be dealt with fairly and swiftly, particularly in countries where investors have concerns about the reliability and independence of domestic courts. Government acceptance of legitimate constraints on policies can provide investors with greater certainty and predictability, lowering unwarranted risk and the cost of capital. Investment treaties are also frequently promoted as a method of attracting FDI which is an important goal for many governments. Despite many studies, however, it has been difficult to establish strong evidence of impact in this regard (Pohl, 2018). Some studies suggest that treaties or instruments that reduce barriers and restrictions to foreign investments have more impact on FDI flows than bilateral investment treaties (BITs) focused only on post-establishment protection (Mistura et al., 2019). These assumptions continue to be investigated by a growing strand of empirical literature on the purposes of investment treaties and how well they are being achieved.

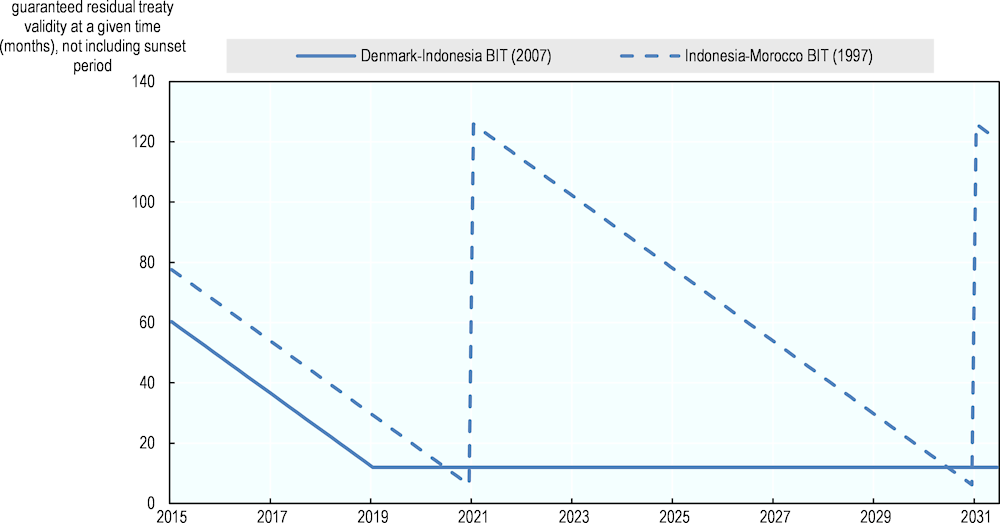

The government’s comprehensive review of its investment treaties in 2014-16 led to the termination of at least 23 of its older investment treaties. But like many other countries, Indonesia still has a significant number of older investment treaties in force with vague investment protections that may create unintended consequences. Many countries, including Indonesia, have substantially revised their investment treaty policies in recent years in response to these concerns as well as increased public questioning about the appropriate balance between investment protection and sovereign rights to regulate in the public interest and the costs and outcomes of ISDS. The government is well aware of these ongoing challenges. It is taking a leading role in multilateral discussions on ISDS reform in UNCITRAL’s Working Group III and updating its model investment treaty in light of recent treaty practices. Experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic may further shape how the government views key treaty provisions or interpretations and how it assesses the appropriate balance in investment treaties.

Notwithstanding the potential benefits of having signed international investment agreements, they should not be considered as a substitute for long-term improvements in the domestic business environment. Any active approach to international treaty making should be accompanied by measures to improve the capacity, efficiency and independence of the domestic court system, the quality of a country’s legal framework, and the strength of national institutions responsible for implementing and enforcing such legislation.

Main policy recommendations for the domestic legal framework

Amend Article 7 of the Investment Law to provide further specification on investor rights to protection from unlawful expropriation and the government’s right to regulate. Issues for possible clarification include whether investors are protected from indirect expropriation, exceptions to protect the government’s right to regulate in the public interest, and the valuation methodology for determining market value of expropriated property. This is not necessarily urgent but the government may wish to identify an appropriate opportunity to propose incremental improvements to this and other aspects of the Investment Law.

Consider updating and modernising existing land laws. Land policy is one of the few areas affecting investors where the government has not enacted significant new legislation in recent decades. The existing system for land tenure is based primarily on legislation enacted in 1960. New laws could clarify existing categories of land tenure rights and reduce conflicts between customary and formal laws. Efficient land administration services go hand-in-hand with clear legal rights. The government should also allocate sufficient funds, institutional capacity and political backing to consolidate on early successes for ongoing initiatives to achieve universal land registration, improve the quality of land data and expand digital solutions and online accessibility for land administration.

Continue to prioritise efforts to improve the regime for intellectual property (IP) rights, especially enforcement measures. Investors continue to report concerns with widespread online piracy and counterfeiting, long-standing market access issues for IP intensive sectors, high numbers of bad faith registrations of foreign trademarks by local companies and restrictive patentability criteria that make effective patent protection particularly challenging. The government is well aware of these concerns and designs initiatives to address them. Improvements in implementation and IP enforcement measures will help to build overall investor confidence in this area.

Rethink existing approaches to reforming the court system. The government and the Supreme Court have taken significant strides towards ensuring judicial independence, creating specialised courts and judges, establishing a system for legal aid and expanding e-court services. Bold thinking may be required to dismantle certain negative perceptions regarding the effectiveness of the courts and revitalise the core institutions. The government may wish to consider commissioning a thorough review of the existing civil procedure rules, redesigning the system for judicial appointments to ensure integrity and encouraging the Supreme Court to propose, in consultation with civil society organisations and other stakeholders, more wide-ranging initiatives to promote transparency and greater public scrutiny of court functions.

Evaluate potential amendments to Law 30/1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution. It may be prudent for the government to take stock of court decisions and user experiences under the law over the past two decades to assess the merits of potential amendments to improve legal certainty, user experiences and the attractiveness of arbitration in Indonesia. Areas for possible legislative clarification include the scope of the law vis-à-vis international arbitrations conducted in Indonesia, whether contract disputes involving claims based on tort or fraud are arbitrable and the public policy ground for refusing enforcement of an arbitral award under Article 66 of the law.

Maintain data protection and cybersecurity as a national policy priority. Comprehensive laws that draw on international good practices need to be enacted and effectively implemented in these areas. As with all legislation, the government should consult widely on the existing drafts of these laws and encourage input from business and civil society organisations. The government should also account for considerable, additional work once laws are in place to raise awareness among the private sector and other users, and nurture effective mechanisms to deal with security and data breaches.

Sustain momentum for building a culture of integrity in the public sector and throughout all levels of society. Among other initiatives, the KPK has made significant inroads into concerns regarding corruption through some impressive results, which have transformed it into an important symbol of the government’s commitment to fighting corruption. The government should continue to allocate sufficient resources to the KPK and other anti-corruption institutions and vigorously defend their independence.

Main policy recommendations for investment treaty policy

Continue to reassess and update priorities with respect to investment treaty policy. An important issue for period reassessment is how the government evaluates the appropriate balance between investor protections and the government’s right to regulate, and how to achieve that balance in practice. Indonesia’s model BIT, which the government is currently updating, should reflect the government’s current assessment of the appropriate balance and inform negotiations for new investment treaties. It is more difficult for governments to update their existing treaties to reflect current priorities. Depending on whether the parties wish to clarify original intent or revise a provision, it may be possible to clarify language through joint interpretations agreed with treaty partners. If revisions, rather than clarifications of original intent are desired, then treaty amendments may be required. Replacement of older investment treaties by consent – which appears to be the approach Indonesia has taken in respect of its newest BIT with Singapore – may also be appropriate in some cases.

Continue to participate actively in inter-governmental discussions on investment treaty reforms at the OECD and at UNCITRAL. Many governments, including major capital exporters, have substantially revised their policies in recent years to protect policy space or to ensure that their investment treaties create desirable incentives. Consideration of reforms and policy discussions on frequently-invoked provisions such as FET are of particular importance in current investment treaty policy. Emerging issues such as the possible role for trade and investment treaties in fostering responsible business conduct as well as ongoing discussions about treaties and sustainable development also merit close attention and consideration.

Conduct a gap analysis between Indonesia’s domestic laws and its obligations under investment treaties with respect to investment protections. There are differences between the Investment Law and Indonesia’s investment treaties in some areas. Identifying these differences and assessing their potential impact may allow policymakers to ensure that Indonesia’s investment treaties are consistent with domestic priorities.

Continue to develop ISDS dispute prevention and case management tools. Whatever approach the government adopts towards international investment agreements, complementary measures can help to ensure that treaties are consistent with domestic priorities and reduce the risk of disputes leading to international arbitration. The government should continue to participate actively in the work of UNCITRAL’s Working Group III, the OECD and other multilateral fora on these topics. It may also wish to consider ways to promote awareness-raising and inter-ministerial co-operation regarding the government’s investment treaty policy and the significance of investment treaty obligations for the day-to-day functions of line agencies. Developing written guidance manuals or handbooks for line agencies on these topics could encourage continuity of institutional knowledge as personnel changes occur over time.

Investor protections under the Investment Law

Indonesian law provides a number of core protections to investors in relation to expropriation, non-discrimination and free transfer of funds that have not changed significantly since the first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010). Most of these protections appear in Law 25/2007 concerning Investment (the Investment Law) which has since been supplemented by regulations issued at various levels of government including BKPM. These protections are generally in line with similar provisions found in other regional investment laws and provide clear rights that should instil investor confidence to the extent that enforcement mechanisms are also seen to be robust. The government proposed a number of amendments relating to investment liberalisation as part of the new Omnibus Law on Job Creation but none of these proposals affect the existing provisions on investment protection.

Like many other countries, Indonesia has enshrined in its domestic law a principle of non-discriminatory treatment as between foreign and domestic investors. The Investment Law establishes ten key principles that underpin the government’s objectives for the investment climate (Article 3) including legal certainty through the rule of law, transparency and non-discriminatory treatment as between foreign and domestic investors. In designing investment policies, the government is “to provide the same treatment to any domestic and foreign investors, by continuously considering the national interest” (Article 4(2)). Article 6 provides an express guarantee of “equitable treatment to all investors of any countries that carry out investment activities in Indonesia in accordance with provisions of laws and regulations.” These provisions establish Indonesia’s commitment to a level playing field for all investors and contribute to positive signals regarding an open investment policy, without prejudice to the possibility for the government to preserve its right to implement certain policies that are exempted from this broad equality guarantee.

Despite formal guarantees of non-discrimination, some stakeholders have reported concerns of de facto discrimination against foreign investors linked to economic protectionism (EuroCham, 2019b; US Department of State, 2019). These stakeholders indicate that economic nationalism and an oft-stated desire for self-sufficiency by the government continues to manifest itself through negotiations, policies, regulations and laws in ways that companies consider as eroding investor value. These include local content requirements, requirements to divest equity shares to Indonesian stakeholders and requirements to establish manufacturing or processing facilities in Indonesia. Political forces favouring the protection of certain segments of the local economy from foreign competition have been effective in countering those supporting more in-depth FDI reforms (discussed further in Chapter 3). Some foreign companies operating natural resources projects in Indonesia report growing sentiments that domestic interests should not have to pay prevailing market prices for domestic resources, which some fear may lead to adverse impacts for foreign investors established in this sector (US Department of State, 2019).

Another important legal protection for investors is the government’s guarantee of freedom from unlawful nationalisation or expropriation in Article 7 of the Investment Law. This provision requires the government to provide compensation to investors if it expropriates their property. Compensation should reflect the market value of the property. Disagreements regarding the valuation of expropriated property may be settled through arbitration, if the parties agree, or through domestic courts. While these provisions encapsulate the core building blocks for investor protection from expropriation, they are relatively simplistic alongside the expropriation regimes that Indonesia provides to some foreign investors under its investment treaties and expropriation regimes under investment laws in other countries. For example, Indonesia’s new trade and investment treaty with Australia, which entered into force in July 2020, contains a detailed set of provisions on expropriation including an annex on the interpretation of those provisions. This creates scope for amendments to Article 7 to provide further specification. Issues for possible clarification include:

whether investors are protected from indirect expropriation in the form of government measures that have an effect equivalent to direct expropriation without formal transfer of title or outright seizure and, if so, how indirect expropriation is defined and whether there are any exceptions (e.g. for non-discriminatory regulatory actions designed to achieve legitimate public welfare objectives);

general exceptions such as the government’s right to nationalise or expropriate property for public interest purposes in certain situations;

the valuation methodology for determining market value, including the valuation date, and whether any specific factors should be taken into account when determining this value such as the investor’s conduct, the reason for the expropriation or the profits made by the investor during the lifetime of investment;

whether compensation for expropriation includes interest and, if so, how that interest should be calculated; and

the distinction between compensable and non-compensable expropriations, if appropriate, to establish a minimum level of policy space for the government to implement public policy objectives without being constrained by obligations to compensate affected investors.

Aside from expropriation and non-discrimination, the Investment Law also guarantees that investors may freely transfer and repatriate in foreign currency funds associated with their investment activities including profits, interest, dividends and proceeds from the sale of their assets (Article 8). Repatriation is subject to reporting requirements and obligations to pay taxes, royalties and other government income associated with investment activities. The government and local courts may defer repatriation rights if there are pending claims against the investor (Article 9). Regulations issued by the central bank in recent years impose special reporting requirements on non-bank companies in Indonesia that borrow offshore in foreign currency and mandate the use of rupiah for domestic transactions in Indonesia with only a few limited exceptions, notably international commercial transactions.1

A range of investor obligations accompany the protections offered in the Investment Law. Investors must give precedence to Indonesian nationals wherever possible when addressing their labour needs even if foreign nationals are required for special expertise or management positions (Article 8). Investors must provide training for their local workforce and allow technology transfers to take place between foreign and Indonesian employees, the merits of which are discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 above. Investors are required to follow good practices on corporate governance and corporate social responsibility, fulfil certain reporting requirements, respect local cultural and business traditions and comply with domestic laws and regulations that apply to their activities (Article 15). The Investment Law also identifies a range of more general investor responsibilities regarding contributions to environmental sustainability, fair competition and workers’ rights (Article 16). It envisages further environmental recovery obligations in sectoral laws applicable to non-renewable mining and extractive industries (Article 17). Similar obligations appear in investment laws in other ASEAN countries (see e.g., Myanmar’s Investment Law No. 40/2016, Articles 65‑72). Although these efforts may have been limited by implementation challenges and some opposing views about their efficiency, they are a marker of Indonesia’s commitment to responsible business conduct and provide a good basis for continued efforts by the government in this area (see Chapter 5 on responsible business conduct).

Significant strides towards a reliable land administration system but more could be done to clarify ambiguities in land tenure rules

Secure rights for land tenure and an efficient, reliable system for land administration are indispensable for investors in many countries, including Indonesia. This requires a clear legal framework for acquiring, registering and disposing of land rights, as well as proactive land use plans at all levels of government.

Land tenure rules

The first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010) noted that land policy was one of the few areas of the investment climate where new legislation had not been drafted over the past decade, although a number of regulations had been enacted. This situation has not changed significantly since the first Review. While a new land law had been under preparation in 2010, the government has not enacted any significant new laws relating to land tenure and other land rights since the first Review. Renewed support from the highest levels of government may be needed to consolidate and clarify the system of land rights for investors that is still based primarily on a law enacted in 1960.

The two main laws dealing with land ownership in Indonesia are the Constitution and Law 5/1960 concerning the Basic Provisions concerning the Fundamentals of Agrarian Affairs (the BAL). The Constitution recognises that the state has the right to bestow rights to land. The BAL divides all land into either state land or certified land owned exclusively by natural persons with Indonesian citizenship. It envisages several types of land rights, including rights for ownership, use, construction, management and cultivation. The most extensive right to land in Indonesia is the Hak Milik (right of ownership) which is only available to Indonesian citizens, state companies, religious bodies recognised by the National Land Agency (the BPN) and social organisations recognised by the BPN. With the exception of forestry and mining, the BPN is responsible for all matters relating to Agrarian Law.

It was not possible for foreigners to own land in Indonesia until Government Regulation 41/1996 came into effect in 1996. This regulation introduced new rights for foreign nationals domiciled in Indonesia to own individual apartments or condominiums as strata title units. It also allowed foreign nationals to hold permits for secondary rights to use or develop land where the state holds the primary ownership right. The relevant permits include Hak Guna Bangunan (building rights for up to 50 years) and Hak Pakai (right of use for up to 70 years). These secondary rights can only be granted in relation to state-owned land. Foreigners wishing to acquire rights over privately-owned land must first negotiate with the land owner to relinquish its ownership rights to the state. Government Regulation 103/2015 updated these rules in 2015. The new regulation introduces a precondition for foreigners to hold a residential visa, removes a previous limit on the number of land rights that could be held simultaneously by foreigners and clarified the rights of Indonesian nationals married to foreigners. Article 144 of the Omnibus Law on Job Creation passed by parliament in October 2020 confirms these rights for foreigners. Ordinary long-term lease arrangements of up to 95 years are also possible for foreigners under Indonesian law. Nominee ownership structures, whereby an Indonesian national owns land on behalf of a foreign national, are illegal.

While the legal regime for land ownership is gradually becoming more transparent and liberal, some concerns remain. Many of these concerns stem from the complex system of land rights in the BAL, which sought to merge land rights granted during the Dutch colonial era, customary rights under Indonesia law (adat) and a new system for statutory land rights into a single legal regime that still applies today. The government’s commitment in Article 22 of the Investment Law to simplifying certain land acquisition procedures for investors has done little in practice to improve the situation. The complexity of the BAL continues to create problems for consistent interpretation. While adat, or Indonesian customary law, is declared a primary source of land law, it is simultaneously subjected to all restrictions of formal land law (Article 5 of the BAL). In practice, the implementation of the BAL regime has not always managed to resolve ambiguities in the interaction between customary adat, which varies widely across the archipelago, and new statutory rights. Some stakeholders have consistently urged the government to propose new land legislation to clarify existing categories of land tenure rights and reduce conflicts between customary and formal laws (USAID, 2013, 2019). Others have noted that administrative controls to protect public interests, including proper public announcement of land rights, community participation, protection of occupiers’ interests, and thorough examination of evidence to protect these rights are often bypassed in practice.

Land titling and administration

In order to provide for secure land tenure rights, land administration should be accessible, reliable and transparent. If properly undertaken, land rights registration can enhance land tenure security by recording individual and collective land tenure rights, thereby facilitating the transfer of land tenure rights and allowing investors to seek legal redress in cases of violation of their tenure rights.

As described in the first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010), a fragmented and incomplete land administration system has long hindered the management and governance of land and natural resources in Indonesia. The government has nevertheless taken significant strides towards improving the system for land registration. Since 1997, land holders have been required to register their land. Government Regulation 24/1997 concerning Land Registration identified ways to accelerate land registration, improve legal certainty and conduct programmes to raise public awareness about land laws and land registration. The government also established in 2006 a new Deputy for Land Dispute Resolution Affairs to improve the speedy resolution of land disputes.

Only around 35% of land in Indonesia has been registered to date, most of it in urban areas. Current estimates indicate that there are around 126 million available parcels of land in Indonesia, of which approximately 42 million were registered between 1960 and 2016. BPN statistics available on its website and updated regularly indicate as of May 2020 that this equates to nearly 40 million hectares of land that have been registered and almost 68 million land rights certificates issued. The number of land titles issued each year is also rising, which is a promising sign. Between 2010 and 2016, BPN registered between one and two million new titles annually, while this number has jumped to over eight million titles per year since 2018.

Problems still persist, however, in terms of the time and number of procedures needed to register property. Indonesia ranks 106 out of 190 countries in terms of registering property according to the 2020 edition of the Doing Business indicators, which suggests that there is still room for sustained, longer-term improvement. These indicators are based on firms operating in the Jakarta and Surabaya regions and hence may not be fully representative of the rest of the country. Other than the average time needed to register a land deed (28 days in Jakarta and 40 days in Surabaya), these regions rank below the average for countries in East Asia & Pacific regarding the number of procedures, the cost of registering and the quality of the land administration. Indonesia also ranks 76th out of 141 countries in terms of quality of land administration in the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Competitiveness Report.

Other concerns relate to the time, resources and data still needed to register all available land parcels in Indonesia. The BPN is able to register around one million new (i.e. previously unregistered) parcels of land each year. A study published in 2019 by the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning estimates that it would take another 85 years to record all unregistered land parcels at this rate (Wibowo, 2019). Data quality is another issue. Among the 42 million parcels that have been registered to date, the same study estimates that only 20 million of these parcels have been verified by a chartered surveyor and correctly plotted. These issues contribute to a lack of access to reliable land records and spatial data at the local government level where many resource planning and land registration functions are carried out under the current model for decentralised land administration. This can, in turn, inhibit infrastructure investments and create a lack of clarity and transparency in decision-making, spatial planning and resource allocation (World Bank, 2018b).

Stakeholders have also identified concerns with respect to the prevalence of land disputes between communities and large-scale land users, particularly on environmental matters (see Chapter 5 on responsible business conduct); a lack of clarity in relevant laws and regulations to support land authorities at the provincial level, particularly in relation to settling land conflicts (see Chapter 7 on investment policy and regional development); rising land prices and the effects of increased speculation for land acquisitions, including in relation to proposals to relocate the country’s capital to East Kalimantan; disempowerment of local landowners facing threats of displacement due to unclear land tenure arrangements and the ongoing gaps in registered land rights in some regions; and the disproportionate impacts for women as compared to men of land use conversion, industrial expansion and deforestation (World Bank, 2018b).

The government is aware of these various concerns and seeks to address them. Many initiatives in the past decade have prioritised efforts to register all available parcels of land. The 2011 Geospatial Information Law and the One Map Project (OMP) aim to establish a unified base set of geospatial data (i.e., topography, land use, and tenure) and the National Spatial Data Infrastructure to inform decision-making by land authorities (see Chapter 7 on investment policy and regional development for more information on the OMP). Efforts to accelerate the registration of unregistered land have been redoubled under the Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning and the Head of the National Land Agency 12/2017 concerning the Complete Systematic Land Registration Acceleration. This programme enjoys support from the highest levels of government. Under Presidential Instruction 2/2018, President Jokowi instructed relevant ministries to take all steps to achieve universal land registration by 2025. Promising results since 2018, whereby 8-10 million new parcels of land have been registered annually, indicate that the achievement of this goal is increasingly likely if the current momentum is sustained. Another positive development relates to funding. The government secured USD 200 million in funding between 2018 and 2023 from the World Bank to help to realise this project (World Bank, 2018b). All steps that can be taken to improve the quality of data collected in the national Electronic Land Administration System (eLand) during this project should be encouraged. In particular, the government should encourage BPN to explore digital solutions and online accessibility options that would increase transparency for land information, including through the development of web-based applications to record and publish land information online and improve the efficiency of data collection.

The Omnibus Law on Job Creation, passed by parliament in October 2020, seeks to simplify some land administration procedures and redefine the central government’s role in land policy. Chapter VIII of the law amends several existing laws to ease the requirements for public procurement of small land parcels, clarify procedures for compensation in cases of public land procurement and strengthen protections for land designated as sustainable agricultural land. The law also envisages a more prominent role for the central government in land policy. It establishes a Land Bank Agency under central government supervision to manage and distribute state-owned land and carry out a broad range of functions relating to land planning, acquisition, procurement, management, use and distribution (Article 125). The law introduces strict rules to discourage idle possession of land whereby land left unused or uncultivated for a period of at least two years can automatically revert to the Land Bank Agency (Article 180). The law also vests the central government with new powers to set spatial planning policy and determine environmental approvals under existing laws (Articles 13-20), as well as easing requirements for environmental approvals for some investment projects. It remains to be seen how these various legislative changes will impact investors on the ground. The BPN should make every effort to ensure that these proposed changes, once implemented in the future, lead to sustainable, long-term improvements for investors in their dealings with land administration authorities.

Further progress is needed to improve the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights

An effective regime for registering, protecting and enforcing intellectual property (IP) rights is a crucial concern for many investors. Strong IP rights provide investors with an incentive to invest in research and development (R&D) for innovative products and processes. These rights also instil confidence in investors sharing new technologies, for instance through joint ventures and licensing agreements. Successful innovations may be suffused within and across economies in this way, and contribute to elevating productivity and growth. At the same time, IP rights entitle their holders to the exclusive right to market their innovation for a certain period. The protection granted to intellectual property therefore needs to strike a balance between the need to foster innovation and society’s interest in having certain products, such as pharmaceutical products, priced affordably.

Indonesia has a relatively extensive legal framework for IP rights protection that generally complies with international standards in at least five main areas: trademarks, patents, industrial designs, copyrights and trade secrets. Laws in three of these areas have been amended since the first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010): Law 19/2014 Concerning Copyright (2014 revision); Law 13/2016 Concerning Patents (2018 and 2020 revisions); and Law 20/2016 Concerning Trademarks and Geographical Indications (2018 and 2020 revisions).

At the international level, Indonesia joined the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 1979 and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995. Indonesia is an active participant in the WTO Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Rights (TRIPS Council). It has also signed several key WIPO-administered IP treaties.2

Despite a relatively well-developed legal framework for IP rights protection in Indonesia, issues remain with the effectiveness of enforcement measures and the poor or inconsistent implementation of existing laws. Investors and other stakeholders routinely cite IP rights infringement issues as a principal problem in many ASEAN countries, including Indonesia (European Commission, 2020; EuroCham, 2019a; US Department of State, 2019; USTR, 2020b; IPR SME Helpdesk, 2016). These stakeholders report specific concerns with widespread online piracy and counterfeiting, long-standing market access issues for IP-intensive sectors, high numbers of bad faith registrations of foreign trademarks by local companies and restrictive patentability criteria that make effective patent protection particularly challenging for investors. USTR has urged the government to “develop and fully fund a robust and coordinated IP enforcement effort that includes deterrent-level penalties for IP infringement in physical markets and online” (USTR, 2020b). Many of these issues were identified as ongoing concerns and challenges for the government in the first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010).

These concerns are partly reflected in Indonesia’s international rankings in this area. Indonesia ranks 51st out of 141 countries in terms of IP Protection in the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Competitiveness Report; 85th out of 129 economies in the Global Innovation Index 2019 prepared by WIPO, INSEAD and Cornell University; and 46th out of 53 countries analysed in the 2020 US Chamber International IP Index, which benchmarks the IP framework in these economies on the basis of 45 different indicators. Indonesia remains a “Priority 2” country in the European Commission’s annual IP rights report on third countries based on limited progress made by the government in addressing systemic IP rights protection and enforcement issues identified in the report (European Commission, 2020). It is also listed on USTR’s “Priority Watch List” in its 2020 Special 301 Report (USTR, 2020b). This annual report identifies countries that the USTR considers to deny adequate and effective protection for intellectual property rights or deny fair and equitable market access for investors relying on intellectual property protection. USTR recently reiterated its concerns to the Indonesian government as part of an ongoing country review process for trade preferences that the US grants to Indonesia (USTR, 2020a).

The government is pursuing a range of different initiatives that seek to address these well-known shortcomings. European and US stakeholders have noted positive developments related to Indonesia’s efforts to address online piracy, such as the Infringing Website List (European Commission, 2020; USTR, 2020b). This initiative seeks to encourage advertising brokers and networks to avoid placing advertisements on websites that infringe copyrights on a commercial scale. The government has also issued administrative orders to block over 480 copyright-infringing websites in recent years while the Ministry of Finance has issued regulations clarifying its ex officio authority for border enforcement against pirated and counterfeit goods. The Directorate General for Intellectual Property reports steady increases in its numbers of investigators and other staff, which saw its capacity to conduct infringement investigations double from 16 in 2017 to 36 in 2018. Stakeholders have welcomed Indonesia’s accession to the Madrid Protocol for the Registration of Trademarks in 2017 and the government’s implementing regulation issued in 2018, which bring Indonesia’s trademarks regime closer to international standards.

The new Omnibus Law on Job Creation, which was passed by parliament in October 2020, is the government’s latest effort to improve laws in certain areas. The Law amends Law 20/2016 Concerning Trademarks and Geographical Indications to introduce stricter criteria for trademark registration aimed at stamping out bad faith registrations of foreign trademarks by local companies (Article 108). It also amends Law 13/2016 Concerning Patents to limit the scope of patents subject to compulsory licencing requirements and significantly reduce wait times for decisions on simple patent applications (Article 107). It remains to be seen whether the implementation of these amendments is successful in addressing stakeholder concerns, especially regarding compulsory licensing following Ministerial Regulation 39/2018 on Procedures of Imposition of Patent Compulsory Licences.

Despite these encouraging efforts, further progress is needed. The government should continue to prioritise efforts to strengthen its system for IP rights protections and enforcement as an important part of its goal to improve the overall investment climate. IP rights commitments in trade and investment agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) may be a way of focusing political will to improve the domestic framework. Stakeholders have also routinely encouraged the government to improve enforcement co-operation among agencies and improve the resources and capacities available to investigate IP rights infringements. The government should also develop roadmaps towards implementing additional international commitments, including the Geneva Act of the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs and the 1991 Act of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants. It should also recall the recommendations made in an OECD study published in 2014 on strengthening national innovation and growth through Indonesia’s IP rights regime, all of which remain relevant today (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Improving Indonesia’s IP rights regime in terms of contributions to innovation and economic development

An OECD study published in 2014 on “National Intellectual Property Systems, Innovation and Economic Development” considered the role of national systems of IP in the socio-economic development of emerging countries, notably through their impact on innovation. It presented a framework to identify the key mechanisms that enable IP systems to support emerging countries’ innovation and development objectives. The report includes a country study of Indonesia to identify strengths and weaknesses in the IP system from the perspective of contributions to national innovation performance. This work forms part of the OECD-World Bank Innovation Policy Platform project, a web-based, interactive space that provides access to open-data, learning resources and opportunities for collective learning on innovation policy.

The report identifies five concrete policy recommendations for policy makers in Indonesia in their efforts to strengthen national innovation and growth through IP:

Efforts aimed at standardising and automating procedures to increase the processing efficiency of IP applications should be a priority, as lengthy delays weaken incentives. Policy steps also have to be taken to avoid the potential exclusion of smaller entities, as well as businesses in remote geographic areas.

Policies should encourage the use of IP by national actors, including the launch of IP awareness and capacity-building initiatives. Incentive schemes should give researchers a stake in the returns from their inventions, by rewarding most those who commercialise inventions with high industrial applicability. This requires resolving legal uncertainties regarding the licensing of IP generated from public funding sources.

Embracing “new” types of IP, such as traditional knowledge, genetic resources, folklore and geographical indications, will be attractive for Indonesia, but these need to be used to generate value if they are to serve the innovation system. Indonesia’s IP policy should take further complementary steps to support commercialisation.

To achieve these objectives, the country’s IP policy has to undertake a more coherent approach involving the various actors of Indonesia’s innovation governance system.

Source: OECD (2014), National Intellectual Property Systems, Innovation and Economic Development with perspectives on Colombia and Indonesia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204485-en.

Some incremental reforms have improved the court system but bold action may be needed to address long-standing concerns

The ability to make and enforce contracts and resolve disputes efficiently is fundamental if markets are to function properly. Good enforcement procedures enhance predictability in commercial relationships by assuring investors that their contractual rights will be upheld promptly by local courts. When procedures for enforcing contracts are overly bureaucratic and cumbersome or when contract disputes cannot be resolved in a timely and cost effective manner, companies may restrict their activities. Uncertainty about the enforceability of lawful rights and obligations raises the cost of capital, thereby weakening firms’ competitiveness and reducing investment. It can also foster corruption in the court system.

The existing framework for domestic adjudication of civil disputes in Indonesia continues to suffer from a number of significant problems. Some of these issues seem to persist since the first OECD Investment Policy Review (OECD, 2010). Government initiatives in the past two decades have led to some improvements. The “one-roof” reforms introduced in 1999 and implemented by 2004 re-established an independent judicial branch in Indonesia headed by the Supreme Court. These reforms largely freed the judiciary from the political interference of the Justice Ministry that was endemic under the New Order government. However, reforms since then have been gradual rather than sweeping and have encountered some resistance. Some stakeholders continue to perceive the court system as costly, cumbersome, corrupt and dominated by cronyism (US Department of State, 2020; AustCham, 2020; EuroCham, 2019b; Overseas Development Institute, 2016). Some foreign investors also cite concerns with the lack of transparent and fair treatment in Indonesian courts, with judges not bound by precedent and many laws open to various interpretations (US Department of State, 2020).

Several global indicators identify the weaknesses in the justice system. Indonesia ranks, for instance, 59th of 126 countries in the 2020 edition of the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index. While this places Indonesia 5th of 30 other lower middle-income countries covered by the indicator, Indonesia’s performance is below the group median for the civil justice system indicator. When compared to 15 other countries in the East Asia & Pacific region, Indonesia ranks poorly in three indicators: civil justice, criminal justice and absence of corruption. Only Cambodia ranks lower than Indonesia among these other countries in the region in terms of absence of corruption (127th of 128). The World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 indicators also point to problems in the effectiveness of contract enforcement mechanisms in Indonesia, ranking the country 139th of 190 countries covered in the indicator (using data from Jakarta and Surabaya). Indonesia scores better in several other indicators in the World Bank’s report (see Chapter 6 on investment promotion and facilitation). But enforcing contracts through the courts was assessed on average as costing around 70% of the claim value, which is about 1.5 times the regional average (47.2%), taking around 14 months to complete and subject to a quality of judicial process close to the median scores for 25 countries in the East Asia & Pacific region.3

The government is well aware of these problems and seeks to address them. The Long-Term National Development Plan (2005-2025) (Law 17/2007), the National Medium-Term Development Plan (2015-2019) and the National Medium-Term Development Plan (2020-2024) all identify the importance of establishing criminal and civil justice systems that are efficient, effective, and accountable for justice seekers, supported by lower levels of corruption and professional law enforcement personnel with integrity and independence. The government’s development plans specifically link improvements in the legal system to Indonesia’s economic development challenges, acknowledging that investors and the private sector cannot operate without legal and regulatory certainty. In pursuit of this goal, three specific objectives are stated: improved transparency, accountability and speed in law enforcement; improved effectiveness or corruption prevention and eradication; and respect, protection and fulfilment of human rights.

The establishment of specialised judges and courts has improved some court services. The Supreme Court has established at least six specialised courts with dedicated judges trained in their respective fields: the Anti-Corruption Court; the Commercial Court; the Industrial Relations Court; the Fishery Court; and the Taxation Court. A large number of other courts have also been established under the supervision of the Supreme and Constitutional Courts including appeal courts (34), general courts (330), administrative courts (26), religious courts (343) and ad hoc military courts. A small claims court was established in 2019 to handle disputes under IDR 500 billion. Some investors have brought cases before the administrative courts with claims relating to licence revocations and other government decisions; licence disputes involving investors have also been heard in the general courts and even subject to judicial review in the Supreme Court on occasion. But this disparate system of courts with overlapping jurisdictions in some instances creates complexity for investors needing to rely on it.

Other important incremental reforms and improvements have been achieved in recent years. Law 16/2011 on Legal Aid, together with accompanying implementing regulations, established a legal framework for government funding of legal aid. Various Supreme Court regulations and circular letters have established small claims courts, a specialised chamber system within the Supreme Court, and templates for court documents and decisions that have improved efficiency. The Supreme Court has also initiated several e-court programmes to improve access to court judgments through online databases and increase the use of electronic forms of case management. If implemented effectively, the e-Court system set out in Supreme Court Regulations 3/2018 and 1/2019 has the potential to be a breakthrough reform that reduces scope for corruption, improves accuracy and processing times and increases access to the justice. As of March 2019, 36% of Indonesian courts across all jurisdictions had adopted the e-Court system and nearly 16 000 lawyers and other advocates had registered for e-Court services (Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Justice, 2019). An ethics committee within the Supreme Court has worked with the Judicial Commission on developing an Ethics Code and Judicial Conduct Guidelines and has punished many court staff for violating the code. Stakeholder contributions have been significant in achieving these reforms and increasing public pressure for better governance, including through local civil society organisations and partnerships with foreign governments such as the Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Justice since 2014.

Despite these developments, significant reforms are still needed. The Supreme Court’s 2010 Blueprint for Justice Reform (2010-2035), which was developed with the help of an external consulting company and a team of civil society organisations, identifies a number of important reforms that the government should continue to support. Some stakeholders consider, however, that the government will only be able to address the systemic issues that still hamper the Indonesian court system if it is prepared to rethink the core institutions, rules and attitudes that support it (Crouch, 2019; Lev, 2004). This would include a thorough review of the existing civil procedure rules, continual improvements to the system for judicial appointments and more wide-ranging initiatives to promote transparency and greater public scrutiny of court functions. Changes to legal education and public awareness are also key determinants in the success of any legal-institutional reforms and may be the only way to invert deep-seated attitudes regarding fairness and efficiency in the Indonesian justice system for future generations of judges, prosecutors, lawyers, police officials and, in some cases, members of parliament. Ongoing efforts by the National Development Planning Agency, the National Statistical Bureau and a consortium of civil society organizations and NGOs to develop a national Access to Justice Index should also be encouraged. Resources and technical expertise to implement the government’s justice reform plans is likely to be an enduring issue. The government should continue to seek opportunities to collaborate with international partners on justice reform projects and maintain ties with existing donors in this area including various United Nations agencies, USAID, the European Commission and the governments of Australia, Japan, the Netherlands and Norway.

And many investors continue to prefer arbitration and other forms of alternative dispute resolution to litigation

Commercial disputes may arise for investors with joint venture partners, employees, local suppliers or contractors, or government agencies. The cheapest and quickest way to resolve disputes is by negotiation or mediation whenever possible, but if the parties cannot reach an amicable settlement by these means, then they have no choice but to pursue the issue in the courts or arbitration. Arbitration is possible only if the parties agree to it in an underlying contract or after a dispute has arisen between them. Article 32 of the Investment Law envisages that investor can rely on court or arbitration proceedings to settle any disputes that may arise with the government. The default option for domestic investors is court proceedings while the default for foreign investors is international arbitration.

Law 30/1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution (the Arbitration Law) governs domestic and international arbitrations in Indonesia as well as the enforcement of foreign arbitral awards in line with the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the New York Convention). Unlike the arbitration laws in many other countries, the Arbitration Law is not based on the Model Law published by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) in 1985, which is designed to assist states in reforming and modernising their arbitration laws. It nonetheless provides a comprehensive framework for commercial arbitration and addresses the core topics covered in most arbitration laws on the constitution of arbitral tribunals, the role of the courts, arbitration procedures and enforcement of arbitral awards.

Stakeholders have reported relatively positive experiences with the Arbitration Law in practice and the government is not considering any major reform proposals at this time. However, the government may wish to consider amending the Law at an appropriate time in the future to clarify certain aspects of it. The Law does not expressly state that it applies to international arbitrations conducted in Indonesia even though in practice the Indonesia courts have interpreted it as covering both domestic and international arbitrations. Clarification of whether contract disputes involving claims based on tort or fraud fall within the definition of arbitrable disputes under Article 5 of the Law may also help to avoid unnecessary litigation on this issue. Some stakeholders have also reported difficulties in enforcing foreign arbitral awards against Indonesian debtors (US Department of State, 2020). Article 66 of the Law does not provide guidance on when the court should refuse to enforce an award that “conflict[s] with public order”. Guidance or clarification in the Law would help to reduce inconsistency in judicial interpretations and dissuade award debtors from filing frivolous defences to delay enforcement through costly and lengthy court procedures. Provisions allowing the enforcement of arbitral awards that grant interim relief or injunctive remedies might also be considered as the Law is silent on this issue.

A number of local institutions administer arbitrations and provide a range of alternative dispute resolution services. The Indonesian National Board of Arbitration (Badan Arbitrase Nasional Indonesia or BANI), established in 1977, is the oldest and most commonly used arbitration institution in Indonesia. BANI has its headquarters in Jakarta and regional offices in Bandung, Denpasar, Medan, Pontianak and Batam. It has administered more than 1000 cases to date. It maintains a roster of 150 arbitrators split equally between local and foreign arbitrators. Several other specialised arbitration institutions have also been established in recent years including the Capital Market Arbitration Board, the National Sharia Arbitration Board, the Arbitration and Mediation Board of Intellectual Property Rights and the Commodity Futures Trading Arbitration Board, among others. Many of the institutions also provide mediation and conciliation services, along with the dedicated National Mediation Centre. The Ministry of Public Works established the Construction Dispute Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution Institution (BADPSKI) in August 2014 but this institution is not yet operational. Notwithstanding the growth of local arbitration institutions, many foreign investors still prefer to refer their disputes to institutions based in regional arbitration hubs like Hong Kong (China) and Singapore.

Sustained momentum is needed to improve the regulatory climate supporting the digital economy

Indonesia is home to the largest and fastest growing internet economy in the region, estimated at USD 40 billion in 2019 (Bain & Company et al., 2019; McKinsey & Company, 2018). Starting with its 14th economic package in 2016, the government has pursued a range of initiatives to promote the country’s potential as a leading digital economy including the National e-Commerce Roadmap, the 2020 Go Digital Vision, the Digital Talent Scholarship programme and the Indonesia 4.0 strategy aimed at implementing new manufacturing technologies. President Jokowi’s address at the Indonesia Digital Economy Summit 2020 reiterated these ambitions and noted the important challenges being tackled to achieve them (Cabinet Secretariat, 2020a, 2020b). One of these challenges is in developing and implementing a comprehensive regulatory framework for cybersecurity and data protection.

Together with a strong framework for IP rights, these aspects of the regulatory environment are of increasing importance for all investors, not just digital services and new technology firms. The Indonesia Security Incident Response Team on Internet Infrastructure recorded more than 207 million cyber attacks in Indonesia between January and October in 2018 (DetikInet, 2018). Recent high-profile examples include the WannaCry ransomware attack in May 2017 where hackers encrypted data and demanded ransoms from victims all round the world including several hospitals in Indonesia. Digital security incidents can have far-reaching economic consequences for investors in terms of disruption of operations (e.g. through inability to provide services or sabotage), direct financial loss, litigation costs, reputational damage, loss of competitiveness (e.g. in case of theft of trade secrets) and loss of trust among customers, employees, shareholders and partners. These concerns are amplified for digital and new technology firms. While investors must develop their own risk management and data integrity strategies, governments are increasingly being called upon to support investor efforts in this area with institutions to monitor and protect against cyber threats (OECD, 2012, 2015, 2018a).

The government has taken significant strides towards making cybersecurity a national policy priority. It established a National Cybersecurity Agency (BSSN) in 2017 under Presidential Regulation 53/2017 (amended by Presidential Regulation 133/2017). BSSN manages national, regional and international co-operation in cyber security affairs. It is also responsible for financing and overseeing the activities of the Security Incident Response Team on Internet Infrastructure, which was initially established in 2010 under a regulation issued by the Minister of Communication and Information Technology (16/PER/M.KOMINFO/10/2010). This team carries out a range of enforcement activities including monitoring and early detection of cybercrime incidents, responding to reports of cybercrimes by consumers and monitoring evidence of internet transactions. Security for classified government information is overseen by the National Encryption Agency (Lembaga Sandi Negara), whose functions will soon be transferred to the BSSN when it becomes fully operational. Separate cybercrime units also exist within the Ministry of Defence, national police and national armed forces to support specific operations. The government is also participating in several bilateral and multilateral co-operation efforts in this area including with ASEAN partners, the UN Open-Ended Working Group on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security and bilateral dialogues on cybersecurity issues with Australia and Russia in 2017.

To date, however, there is still no overarching regulatory framework to co-ordinate these ad hoc initiatives. An existing law on Electronic Information and Transactions (Law 11/2008, amended by Law 19/2016) and a government regulation on the Organisation of Electronic Systems and Transactions (Regulation 71/2019) currently do not address cyber security issues. BSSN is leading efforts to complete a revised draft of a proposed Law on Cyber Security and Resilience by the end of 2020. The government included this project in the National Priority Legislation Program for 2020. The House of Representatives has considered earlier drafts of this law on several occasions since 2014. Ongoing revisions will reflect these discussions and comments received during public stakeholder consultations. Some stakeholders have suggested that further clarity is needed on the proposed functions and co-ordination between interagency institutions and safeguards to ensure respect for human rights, as well as a roadmap to building adequate institutional capacity and private sector engagement to implement the law effectively. BSSN is also preparing a draft presidential regulation on the protection of national critical information infrastructure and regulations affecting security audit powers and requirements for information security management systems that will apply to companies operating in Indonesia.

Progress in relation to personal data privacy regulation has been slower. Several existing laws and regulations address specific data protection issues for the financial, health and telecommunications sectors.4 But unlike over 120 countries around the world, including within ASEAN, Indonesia has not yet adopted comprehensive data protection and privacy laws. Such protections are becoming increasingly essential for protecting both personal and non-personal data and improving trust for consumers and investors. The government submitted a draft law to parliament in January 2020 but its progress has been hampered by the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The draft law is based primarily on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

Investors will no doubt follow with great interest the passage and eventual implementation of these proposed new laws, as well as provisions under the Omnibus Law on Job Creation to provide further clarity on technology transfer obligations for investors. The government should continue to prioritise these efforts and learn from recent good practices around the world to maximise the impact of these laws during the implementation phase. It should continue to engage transparently and actively with stakeholders from the private sector regarding the impacts for investors under the proposed laws. Establishing legal frameworks for cybersecurity and privacy is an essential first step but the government should also account for considerable, additional work once the laws are in place to raise awareness among the private sector and users alike and nurture effective mechanisms in practice to deal with security and data breaches. All of these efforts should be tackled with a view to increasing economic and social prosperity and not simply for furthering criminal or national security-related aspects.

Recent trade and investment treaties are another means by which the government is seeking to strengthen coherence on domestic laws affecting investors in this area. Indonesia’s new trade and investment treaty with Australia, which entered into force in July 2020, is a good example.5 It includes provisions that require the treaty parties to remove data localisation barriers, prohibit forced technology transfers, establish adequate domestic safeguards for data privacy and/or enforce online consumer protections; other provisions create general exceptions for non-discriminatory regulation in this area or exclude it from ISDS. It also expressly recognises the importance of “building and maintaining the capabilities of their national entities responsible for computer security incident response, including through exchange of best practices; and using existing collaboration mechanisms to co-operate to identify and mitigate malicious intrusions or dissemination of malicious code that affect the electronic networks of the Parties” (Article 13.3). Recent trade and investment agreements concluded by other countries require the treaty parties to take into account international guidelines and standards when developing their national laws such as the OECD Recommendation concerning Guidelines governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (2013) and the OECD Recommendation on Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity (2015).

Ongoing efforts to tackle corruption, reduce bureaucracy and improve the regulatory framework for investors

Corruption has been a long-standing concern for investors in Indonesia. Although it is more than two decades since the end of the New Order regime, which was associated with rampant corruption at the top levels of government, Indonesia still suffers from a negative international image in terms of corruption. Recent high-profile cases include criminal convictions in the United States, the United Kingdom and France relating to bribes paid to Indonesian government officials by a multinational telecommunications company, a multinational airline manufacturer and a consortium of foreign investors seeking to secure a multi-million dollar contract to develop a power plant project (US Department of Justice, 2020, 2019; UK Serious Fraud Office, 2020). Indonesian authorities have also prosecuted a range of charges in recent years against government officials who allegedly accepted bribes or kickbacks for granting permits or contracts to investors and, in some cases, judges who accepted bribes to fix court rulings. If prosecution efforts are unable to keep pace with the extent of the offences, however, firms that refuse to make such payments can be placed at a competitive disadvantage when compared to firms in the same field that engage in such practices.

International indicators in this area attest to the problem. Indonesia ranked 85th out of 198 countries surveyed for the perceived levels of public sector corruption in Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency International Indonesia, the national chapter of the international anti-corruption civil society organisation Transparency International, conducts the annual survey upon which Indonesia’s assessment in the Index is based. The Index is one of the official key indicators for the Long-Term 2012-25 National Strategy on Prevention and Eradication Corruption, and has therefore become one of the most important governance indicators used by policy makers and the private sector in Indonesia to inform their decisions. Transparency International reports that nearly 700 out of 1000 Indonesian nationals that took part in a 2016 survey said they thought that the level of corruption had worsened in the last 12 months (Transparency International, 2017). Aside from the Index, Indonesia ranks 77th out of 141 countries for corruption indicators in WEF’s 2019 Global Competitiveness Report. Foreign investors also routinely cite corruption among their top problems in others surveys about doing business in Indonesia (US Department of State, 2020; AustCham, 2020; EuroCham, 2019b; Overseas Development Institute, 2016).

The first OECD Investment Policy Review (2010) noted that the government had made fighting corruption a top priority. The government’s Long-Term National Development Plan (2005-2025) (Law No. 17 of 2007) identifies “abuse of power in the form of corruption, collusion, and nepotism” as among the key challenges for reforming the government bureaucracy. The first Review addressed in detail the policies, laws and institutions that the government had established by 2010 to promote integrity within government, investigate and prosecute corruption offences, raise public awareness and assess continuously the impact of anti-corruption strategies. These efforts have led to significant progress. Transparency International reports that 64% of Indonesian national that took part in a 206 survey considered that the government was doing well in terms of fighting corruption (Transparency International, 2017). Public optimism may be due to the government’s promotion of open government practices, improvement of institutional co-ordination for corruption prevention and empowerment of ombudspersons to investigate corruption, including at the subnational level.

Recent developments are also encouraging. The National Strategy of Corruption Prevention & Eradication Long-Term (2012-2025) provides a solid multi-stakeholder framework for monitoring and advancing integrity in government and society. It recognises that corruption is an important component of building the enabling environment for quality investment and responsible business conduct (see Chapter 5 on responsible business conduct). The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) plays a major role in building public awareness and confidence by steadfastly pursuing graft cases despite political backlashes. Many observers see KPK as a model of good practice by many countries, in particular because it does not shy away from difficult or sensitive cases (OECD, 2015b). The work of the KPK and the national anti-corruption courts has brought to light many high-profile cases, and they boast an impressive conviction rate – between 2003 and 2018, the KPK prosecuted and achieved a 100-percent conviction rate in 86 cases of bribery and graft related to government procurements and budgets. Presidential Regulation Nos. 13 and 54 of 2018 adopted the 2019-2020 Corruption Prevention Action Plan (which focuses on three areas – licenses, state finances and law enforcement reform) and introduced requirements for Indonesian companies in certain sectors to report beneficial ownership information as part of efforts to fight corruption and tax evasion. This information will be published in an electronic database accessible to the public by the end of 2020, which is hoped will improve transparency and encourage further policy input from civil society organisations and other stakeholders. This initiative is in line with the G20 Anti-Corruption Open Data Principles adopted in 2015.

The challenge for the government is to sustain momentum for building a culture of integrity in the public sector and throughout all levels of society. The National Strategy of Corruption Prevention & Eradication Long-Term (2012-2025) acknowledges that “[c]orruption is still massive and systematic”. Unseating corrupt schemes and changing deep-rooted attitudes may involve taking brave stances against incumbent elites in public and private spheres, which can be a tricky and incremental process. In this context, the government should continue to allocate sufficient resources to the KPK and vigorously defend its independence. However, a new law passed in October 2019 (Law No. 19 of 2019) raises serious concerns about KPK’s future (also discussed in Chapter 5 on responsible business conduct). Among other things, the new law creates a government committee to oversee KPK’s activities, revokes KPK’s authority to carry out independent audio surveillance of suspects, allows the government to place civil servants within KPK’s staff and requires KPK to discontinue investigations and prosecutions that have lapsed for more than two years. It remains to be seen whether these changes will affect the KPK’s effectiveness but investors are no doubt following these developments closely as a marker of the government’s commitment to eradicate corruption. Aside from the KPK, the government should consider reinforcing funding and capacity needed for other anti-corruption institutions like the national police and Attorney General’s Office that do not have the same resources or track-record as the KPK.