Access to medicines is a fundamental pillar of any functioning health system. In Latvia, the outpatient pharmaceutical sector is well-established and regulated, and while the necessary functions and institutions are in place, patient access remains impaired by high levels of out-of-pocket payments. While this may be attributed, in part, to a low level of public health spending overall, within the pharmaceutical sector there are a number of policy options that would enhance affordable access in the short and medium term, with only modest impact on public budgets. Nonetheless, the current level of public spending on health in general (and on medicines in particular) remains among the lowest within the OECD, and greater public investment in health will be needed to substantially improve affordable and sustainable access to outpatient medicines in the longer term.

OECD Reviews of Public Health: Latvia

4. Effective use of pharmaceuticals

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

Within the context of functioning health systems, essential medicines are those that should be available at all times, in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms and with assured quality, at prices both the individual and the society can afford (Quick et al., 2002[1]). The importance of access to essential medicines is recognised in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 3.8 mentions the importance of “access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all” as a core component of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) (WHO, 2017[2]).

Ensuring access to essential medicines can make an important contribution towards improving public health. In countries where access is not guaranteed, or where high out-of-pocket payments prevail, patients may forego or postpone filling prescriptions and purchasing medicines, or may be entirely unable to access care for financial reasons (Goldman, Joyce and Zheng, 2007[3]) (Niëns et al., 2010[4]). This can lead to more rapid progression of disease and poorer health outcomes. High out of pocket costs for medications are not limited to low- and middle-income countries, but have also been identified in some high-income countries in Europe, particularly in relation to the treatment of chronic diseases (Arsenijevic et al., 2016[5]).

In Latvia, the pharmaceutical sector has been at the centre of attention in recent years. It is broadly recognised that it has become costly both for patients and the public payer, impairing patient access to needed therapeutics, and generating substantial pressures on public finances. The objective of this chapter is to describe and analyse the current landscape of the pharmaceutical sector in Latvia and to propose policy options to address the ongoing challenges.

The chapter begins by describing the organisation of the Latvian pharmaceutical system, the institutions involved, and the general regulatory arrangements. It then describes how, despite a solid legal and organisational framework, the outpatient pharmaceutical sector presents significant issues of concern in Latvia. Discrepancies between current levels of medicines consumption and the epidemiological profile of the population have been observed, and despite increasing expenditure on medicines, Latvians face substantial difficulties in accessing needed medicines. Finally, the chapter outlines some policy options for enhancing patient access and providing better financial protection from the costs of ill health, while at the same time improving the efficiency of public spending on medicines.

4.2. General organisation of the Latvian pharmaceutical sector

The legislation and policies governing the pharmaceutical sector are well defined in Latvia. The pharmaceutical department of the Ministry of Health, the State Agency of Medicines (SAM) of Latvia, the National Health Service (NHS) and Health Inspectorate (HI) are the main institutions responsible for the development and implementation of pharmaceutical-related policies.

4.2.1. The State Agency of Medicines is responsible for all regulatory activities

In order for a pharmaceutical product to access the Latvian market, the SAM (or the European Medicines Agency for centrally-authorised products) must first have granted marketing authorisation that allows the medicine to be sold on the Latvian market. According to the Latvian Ministry of Health, as of 2018 4 252 medicines were registered in Latvia.

The SAM is the national regulatory authority for pharmaceutical products and is responsible for assessing the quality, safety and efficacy of human medicines. The SAM issues marketing authorisations, maintains the register of medicines, schedules medicinal products according their access status (prescription or over-the-counter), and is responsible for pharmacovigilance, including the collection of adverse event reports. It also issues licences to manufacturers and regulates pharmaceutical manufacturing, wholesaling, retailing and importing/exporting activities (Behmane D, 2019[6]).

Since 2019, the SAM has also had responsibility for Health Technology Assessment activities (see Box 4.1). This was previously a responsibility of the NHS, but the function was split in that year and some of the staff were transferred to the SAM. The NHS remains responsible for reimbursement decisions, usually relying on budget impact analysis (see the section below).

Box 4.1. Health Technology Assessment

Health technology assessment (HTA) is a multidisciplinary process that systematically assesses information not only on the clinical benefits, but also on the social, ethical and economic aspects of the use of health technologies and health care interventions. HTA aims to inform policy and decision-making in health care, with a focus on how best to allocate limited resources among health technologies and interventions. It is frequently used to determine the relative value-for-money provided by a new medicine compared to existing treatment options in order to prioritise the use of efficient and effective health technologies.

Many countries have established HTA systems to inform decision-making, but the extent to which HTA is used for coverage decisions varies. While some countries systematically apply HTA to all new medicines (e.g. Denmark, France and Poland), others only assess those causing particular concerns due to, for example, uncertain effectiveness, high prices or high budget impact (e.g. the United Kingdom).

In Latvia, HTA is undertaken for each drug proposed for reimbursement. The effectiveness of the new drug is compared with already reimbursed drugs or other reference products. Cost-effectiveness analysis and budget impact analysis are also part of the HTA process, but no explicit incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) threshold has been defined. The evaluation work is shared between the SAM and the NHS.

4.2.2. Reimbursement decisions are the responsibility of the NHS

The NHS is the responsible institution for decisions regarding the reimbursement of pharmaceuticals and the inclusion of products in the positive list (see Box 4.2). To have a product included in the positive list, a pharmaceutical company must submit an application to the NHS containing the opinion of the SAM, together with an assessment of comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the medicine for the intended patient group (see Box 4.3).

Box 4.2. Positive lists for reimbursement of medicines

A positive list, to which new medicines are added for reimbursement if they fulfil predefined criteria, is the main instrument used by most countries to manage their medicines benefit packages. Medicines included in a positive list may be dispensed at the full or partial expense of a third-party payer.

Some countries employ more than one positive list (Croatia, Slovenia), usually corresponding to different levels of reimbursement. Others have a single positive list that may be divided into different parts according to the different reimbursement and/or prescribing rules that apply.

Similar to the majority of EU countries, Latvia uses a positive list to define the basket of medicines publicly covered.

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[9]), “Medicines Reimbursement policies in Europe”.

Regulation No. 899 (on the Reimbursement of Expenditures for Medicinal Products and Medicinal Devices) determines the conditions for the reimbursement of outpatient medicines. The NHS evaluates applications on the basis of the information provided by companies and the results of HTA evaluations conducted by the SAM. It eventually makes a decision for or against the inclusion of a medicine in the positive list.

Clinical factors that are weighed in the evaluation include the burden of disease and the therapeutic value of the medicine. Economic criteria include the results of cost-effectiveness analyses and the expected budget impact of the reimbursement decision for public finances. The basis for the evaluation is the common Baltic guidelines for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals (see Box 4.3), which, with minor changes, have been adapted to each of the Baltic states’ national legislation.

Box 4.3. Common Baltic guidelines for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals

The common Baltic guidelines for economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals are a result of the very close collaboration the Baltic states have developed over years. Other examples include the joint procurement of vaccines under the Baltic Partnership Agreement.

While there are many scientific and methodologic guidelines available to support the economic evaluation of medicines, they cannot be generalised to every country, as economic circumstances and health care system structures may differ substantially. However, as the Baltic states share similar social and economic conditions, the three countries agreed to utilise pharmaco-economic analyses (including cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses) to inform drug reimbursement and other state funding decisions.

The common Baltic Guidelines for Economic Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals provide the basis for the pharmaco-economic analyses submitted as part of each application to include a new drug in the positive list for reimbursement. They are intended for use by all the institutions undertaking HTA activities in the Baltic States.

Using common principles facilitates co-operation between state institutions in the evaluation of applications and simplifies the application process for marketing authorisation holders.

Source: Mitenbergs et al. (2012[10]), “Latvia: Health system review”.

4.2.3. The positive list is divided into four categories

The list of publicly covered outpatient pharmaceuticals consists of four parts.

List A includes groups and sub-groups of interchangeable pharmaceutical products, for which the NHS reimburses at a single “reference” price. The groups may consist of products containing the same active ingredient, or groups of products within the same class considered therapeutically substitutable (e.g. ‘statins’, angiotensin II receptor antagonists).

List B consists of reimbursed products that cannot be substituted or interchanged.

List C contains high unit-cost pharmaceutical products with annual treatment costs exceeding EUR 4 300. The number of patients to be treated with list C medicines is defined on an annual basis. Prescription of a medicine included in list C must be requested by a group of specialists and is approved by the NHS on an individual basis.

List M contains pharmaceutical products for pregnant women, women up to 70 days post partum and children under 24 months.

Lists A and B comprise 1 727 products (corresponding to 424 different molecules or combinations of molecules) and list C comprises 33 (corresponding to a similar number of molecules). The limited numbers of products in lists B and C largely reflect budget constraints.

Medicines included in the positive list are also classified into one of three reimbursement categories (100%, 75%, and 50%, see Table 4.1). The reimbursement category depends on the indications for which a particular medicine has been approved (i.e. disease-specific eligibility, see Box 4.4) (Silins and Szkultecka-Dębek, 2017[7]).

As of 1 April 2020, retail pharmacies dispense the product with the lowest price (i.e. the reference price for the group). Where a patient refuses the medicine offered by the pharmacy and requests a different product within the reference group, the medicine is no longer eligible for reimbursement and the patient must pay the full price for all the medicines on the same prescription (see next section). In addition, a prescription fee of EUR 0.71 per item applies to any medicine reimbursed at 100% (with exemptions for selected patient groups, e.g. children and asylum seekers).

Table 4.1. Reimbursement categories for outpatient medicines

|

Reimbursement category |

Criteria |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Category I (100% reimbursement)* |

Full reimbursement of the reference price of medicines treating chronic, life-threatening diseases or a disease that results in a severe, irreversible disability, and the treatment of which requires the use of the respective medicinal products to maintain the patient’s vital functions. |

Cancers, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, etc. |

|

Category II (75% reimbursement) |

Reimbursement of 75% of the reference price of medicines for chronic diseases, the treatment of which without the administration of the respective medicinal products would complicate the maintenance of the patient’s vital functions, or a disease that results in a severe disability. |

Parkinson’s diseases, depression, hypertension, chronic ischaemic heart disease, stroke, heart failure, asthma, etc. |

|

Category III (50% reimbursement) |

Reimbursement of 50% of the reference price of medicines for chronic or acute diseases, the treatment of which requires administration of the medicinal product to maintain or improve the patient’s health condition. |

Osteoporosis, gastric ulcer, COPD, lipoprotein metabolic disorders, etc. |

Note: the three reimbursement categories apply to disease categories, not to drugs. This means that a same drug may be reimbursed at different levels, depending on the pathology it is intended to treat. * A prescription fee of EUR 0.71 per item applies to medicines reimbursed at 100%.

Source: Silins and Szkultecka-Dębek (2017[7]), “Drug Policy in Latvia”.

Prices for medicines in list A are updated quarterly (1 January, 1 April, 1 July and 1 October) by the NHS. Other changes to the lists of reimbursed medicines are made by the NHS on the first day of each month.

Box 4.4. Eligibility for coverage by third-party payers

Four arrangements can be described regarding eligibility for reimbursement.

Product-specific eligibility: A medicine is considered either reimbursable (its expenses are fully or partially paid for by a third-party payer) or non-reimbursable. The competent authority for pharmaceutical reimbursement or a third-party payer determines the reimbursement status of each medicine. The majority of European countries rely on such scheme (France, Spain, Italy, etc.).

Disease-specific eligibility: In this approach, the reimbursement status and the reimbursement rate of a medicine are linked to the disease to be treated. The same medicine may be reimbursed at different rates depending on the patient’s disease. Disease-specific reimbursement for outpatient medicines is the main scheme in Latvia and the other Baltic States as well as in Malta. Some other countries such as France use it as a supplementary scheme.

Population group-specific eligibility: Under this scheme, specific population groups are eligible for pharmaceutical reimbursement at 100%, or at a higher rate than the standard reimbursement rate. Eligible population groups may be based on conditions (e.g. chronic or infectious diseases, disability, pregnancy), age (e.g. children, the elderly), status (e.g. pensioners, war veterans) or means (e.g. people on low incomes, unemployed). Population group-specific reimbursement is a key scheme in, for example, Cyprus and Ireland. Several European countries, including Latvia, have adopted elements of the population group-specific eligibility approach to complement other key programs.

Consumption-based eligibility: With this approach, reimbursement coverage increases with increasing pharmaceutical consumption, as measured by an insured patient’s gross pharmaceutical expenditure within a specified time period (usually a year). Once a patient has reached a defined threshold of out-of-pocket payment (the so called “safety net”), the third-party payer fully or partially covers any additional pharmaceutical expenses incurred by the patient within the remaining time period. Consumption-based eligibility schemes protect patients that require more pharmaceutical care (such as the chronically ill) from excessive out-of-pocket payments. Consumption-based reimbursement in the outpatient sector is the predominant approach used in Denmark and Sweden.

In disease-specific reimbursement schemes, as currently in place in Latvia, the same medicine may be reimbursed at different levels depending on the patient’s condition. For example, a medicine treating asthma and COPD may either be reimbursed at 75% or 50% depending on the diagnosis. Latvia also reports some population group-specific eligibility, as some groups (e.g. asylum seekers, children under 18) benefit from a complete waiver of medicine co-payments.

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[9]), “Medicines Reimbursement policies in Europe”.

4.2.4. Prices are regulated at all levels of the distribution chain

Pricing policies are defined as “regulations and processes used by government authorities to set the price of medicines or to exercise price control” (Vogler and Zimmermann, 2016[11]). They are closely linked to reimbursement policies where a third-party payer covers the cost of the medicine. The price of a medicine is the sum of three elements: the ex-factory (or manufacturer’s) price (i.e. the price at which the manufacturer sells it), the distribution margins or mark-ups (wholesale and retail) and any taxes (e.g. VAT). Price regulation can be applied at any step of the distribution chain, for example through control of manufacturers’ prices or through the regulation of distribution margins and mark-ups. In Latvia prices are fully regulated for reimbursed medicines but only partially regulated for non-reimbursed products.

For medicines not included in the positive list the principles for the determination of prices are defined in Regulation N 803 “Regulation on pricing principles for medicinal products”. For these products, only the distribution chain margins are regulated, which means that for each non-reimbursed medicine the pharmacy prices are the same in any community pharmacy throughout the country. The regulation of the margins for non-reimbursed medicines is organised as follows:

The wholesale price is calculated by multiplying the price declared by the manufacturer by a percentage margin and adding an additional fixed margin and the VAT (see Table 4.2). The percentage and fixed margins are defined in the regulation and depend only on the price declared by the manufacturer.

The price at which a pharmacy sells a non-reimbursed medicine is determined by multiplying the procurement price (either the ex-factory or wholesaler’s price without VAT) with a percentage margin and adding a fixed margin and the VAT (see Table 4.3).

Marketing authorization holders declare ex-factory prices to the SAM twice a year (or when prices are changed or a new product is placed on the market). The retail prices are then calculated and published on the agency’s website for consumers and other interested parties.

Table 4.2. Levels of margins applied for the calculation of wholesaler’s prices of non-reimbursed medicines in 2020

|

Manufacturer’s price (EUR) |

Percentage margins |

Fixed margin (EUR) |

|---|---|---|

|

0 – 4.26 |

18% |

- |

|

4.27 – 14.22 |

15% |

0.13 |

|

14.23 and over |

10% |

0.84 |

Source: Republic of Latvia (2005[12]), Regulation of Cabinet of Ministers No. 803, 2005.

Table 4.3. Levels of margins applied for the calculation of pharmacy prices of non-reimbursed medicines in 2020

|

Procurement price (EUR) |

Percentage margins |

Fixed margin (EUR) |

|---|---|---|

|

up to 1.41 |

40% |

0.00 |

|

1.42 – 2.84 |

35% |

0.07 |

|

2.85 – 4.26 |

30% |

0.21 |

|

4.27 – 7.10 |

25% |

0.43 |

|

7.11 – 14.22 |

20% |

0.78 |

|

14.23 – 28.45 |

15% |

1.49 |

|

28.46 and over |

10% |

2.92 |

Source: Republic of Latvia (2005[12]), Regulation of Cabinet of Ministers No. 803, 2005.

For medicines in the positive list, manufacturers’ prices are negotiated between the NHS and the market authorization holder and distribution margins are defined in Regulation N°899 on “Procedures for reimbursement of expenses toward the purchase of medicinal products and medical devices for the outpatient care”.

Manufacturers’ prices are indirectly regulated by virtue of cost-effectiveness evaluations, and in parallel through external price referencing (EPR, see Box 4.5). Comparator countries are the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Hungary. The manufacturer’s price of a reimbursable medicinal product may not exceed that of the third lowest manufacturer price of the same medicinal product in the reference countries, and may also not exceed the manufacturer price in Estonia and Lithuania.

Box 4.5. External Price Referencing (EPR)

External Price Referencing is a key pricing mechanism often applied in the outpatient sector. It is the practice of using the prices of a medicine in one or more countries to derive a benchmark or reference price. This reference price can then be used to set or negotiate the price of the product in a given country.

Several countries (including Austria, Belgium, Estonia and Romania) apply external price referencing as a starting-point to set the list price for some medicines (typically new on-patent medicines). A second step involves negotiations between the third-party payer and the pharmaceutical manufacturer on the specific reimbursement price and conditions.

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[9]), “Medicines Reimbursement policies in Europe”.

After manufacturer’s prices are set, distribution margins for reimbursable medicines are also defined:

Wholesaler price is calculated by adding the wholesale margin to the ex-manufacturer’s price. Wholesalers’ margins are defined in Table 4.4.

The pharmacy retail price is defined by multiplying the wholesaler price with a percentage margin and by adding to it a fixed margin and the VAT. Margins for reimbursable medicines are presented in Table 4.5.

VAT for general goods is set at 21% but is 12% for both reimbursed and non-reimbursed medicines. Reduced rates of VAT for medicines are common in the EU, but at 12% Latvia’s rate remains higher than in several countries, e.g. 2.1% in France, 5% in Lithuania and Hungary.

Table 4.4. Levels of wholesaler margins for reimbursable medicines in 2020

|

Manufacturer’s price (euro) |

Percentage margins |

|---|---|

|

0.01 – 2.83 |

10% |

|

2.84 – 5.68 |

9% |

|

5.69 – 11.37 |

7% |

|

11.38 – 21.33 |

6% |

|

21.34 – 28.44 |

5% |

|

28.45 – 142.27 |

4% |

|

142.28 – 711.42 |

3% |

|

711.43 – 1 422.86 |

2% |

|

1 422.87 and more |

1% |

Source: Republic of Latvia (2006[13]), Regulations No 899 on "Outpatient Treatments And Medicines For The Purchase Of Medical Equipment For The Refund Order".

Table 4.5. Levels of margins applied for the calculation of pharmacy prices of reimbursed medicines in 2020

|

Wholesaler price (in euros) |

Percentage margins |

Fixed margin (euros) |

|---|---|---|

|

0.01 – 1.41 |

30% |

0.00 |

|

1.42 – 2.83 |

25% |

0.07 |

|

2.84 – 4.25 |

20% |

0.21 |

|

4.26 – 7.10 |

17% |

0.43 |

|

7.11 – 14.21 |

15% |

0.57 |

|

14.22 – 21.33 |

10% |

1.28 |

|

21.34 – 28.44 |

7% |

1.92 |

|

28.45 – 71.13 |

5% |

2.49 |

|

71.14 and more |

0% |

6.05 |

Source: Republic of Latvia (2006[13]), Regulations No 899 on "Outpatient Treatments And Medicines For The Purchase Of Medical Equipment For The Refund Order".

4.2.5. The pharmaceutical retail sector is quite concentrated

There are 86 wholesale companies in Latvia, albeit with the top ten accounting for 80% of the total market. This is a very high number for a rather small country like Latvia (just as a comparison, Australia has only three wholesale companies) and limits possible economies of scale. In the retail sector, pharmaceutical services may only be provided by municipal pharmacies (which are public entities), or by private community pharmacies operating under government licence. For private pharmacies, the law requires that at least 50% of the shares must be owned by a certified pharmacist, or at least half the board must consist of certified pharmacists.

The retail sector is quite concentrated, with a high degree of horizontal integration. Horizontal integration refers to a situation where a single person (or corporation) owns more than one community pharmacy. It may allow economies of scale, but it can also lead to limited competition and even monopolies when the same person or entity controls a significant share of the market through one or several chains of community pharmacies (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019[14]; OECD, 2014[15]). Based on information shared by the Ministry of Health, the Latvian pharmaceutical retail market is currently dominated by five chains, which represent 69% of the total market and account for a total value of around EUR 255 million. Only 20% of community pharmacies are owned by pharmacists, the rest belonging to one of the chains operating in the country. This situation is the consequence of changes to the regulation of community pharmacies introduced in 2010 which gave non-pharmacists the right to own pharmacies, and thus created the potential for large consortia to be established. It is also worth noting that only a limited public health role is devolved to pharmacists (see below).

4.3. Despite a solid legal framework, the outpatient pharmaceutical sector in Latvia has significant flaws

Despite the existence of a comprehensive and well-established legal and organisational framework, access to outpatient medicines remains sub-optimal in Latvia. There are significant inconsistencies between the levels of utilisation of certain medicines and those that may be expected given the epidemiological profile of the population. There are also important access issues for patients. These are driven by a number of factors:

Despite medicines representing a growing share of the health system’s budget, the magnitude of overall public expenditure on health is low, limiting the number of medicines publicly covered and requiring high out-of-pocket payments;

As a result, the current reimbursement system is not adequately protecting patients (and particularly vulnerable populations) from the costs of ill-health;

Widespread misconceptions around generic medicines give rise to significant inefficiencies; and

The extent of horizontal integration in the retail pharmaceutical sector limits competition.

4.3.1. Pharmaceutical consumption in Latvia is not commensurate with the burden of disease

Latvia has the third highest level of treatable mortality in the EU, with more than half of it attributable to cardiovascular diseases (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[16]). Pharmacotherapies play a key role in both primary and secondary prevention of such chronic diseases (Wald and Law, 2003[17]; Law, Wald and Rudnicka, 2003[18]; Law et al., 2003[19]).

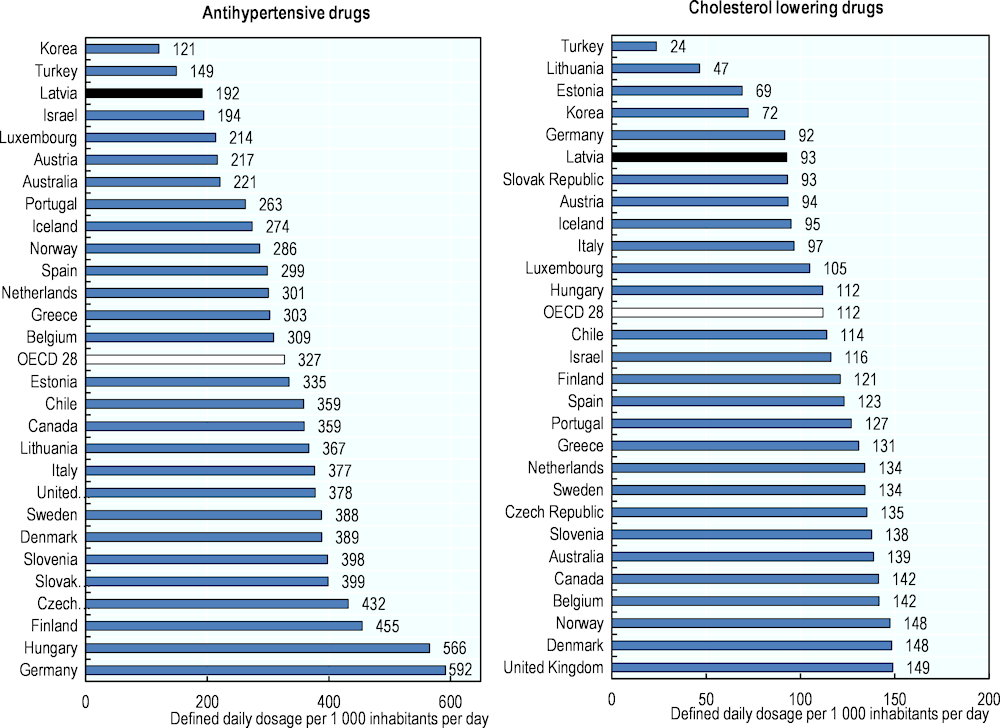

Figure 4.1. Antihypertensive (left panel) and cholesterol lowering (right panel) drugs consumption, 2019 (or nearest year)

Note: data on the left panel refer to the sum of the following classes: C02‑antihypertensives, C03‑diuretics, C07‑beta blocking agents, C08‑calcium channel blockers, C09‑agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system. For the right panel data refer to class C10‑lipid modifying agents.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

Despite this situation, cardiovascular drug consumption levels are among the lowest in the OECD. Consumption of antihypertensive drugs in Latvia, is particularly low (192 Defined Daily Doses per 1 000 inhabitants per day, see Box 4.6 and Figure 4.1) given the burden of cardiovascular diseases in the country but also in comparison with levels of consumption across the OECD (327 on average) and in the other Baltic States (335 in Estonia, 367 in Lithuania). Similarly, the use of cholesterol-lowering agents is low in Latvia (93 DDDs per 1 000 inhabitants per day), almost 20% below the OECD average (Figure 4.1).

Box 4.6. Defined Daily Dose

The defined daily dose (DDD) is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. DDDs are assigned to each active ingredient in a given therapeutic class by international expert consensus. For example, the DDD for atorvastatin is 20mg, which is the assumed maintenance daily dose to treat pain in adults. DDDs do not necessarily reflect the average daily dose actually used in a given country.

Source: OECD (2019[21]), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

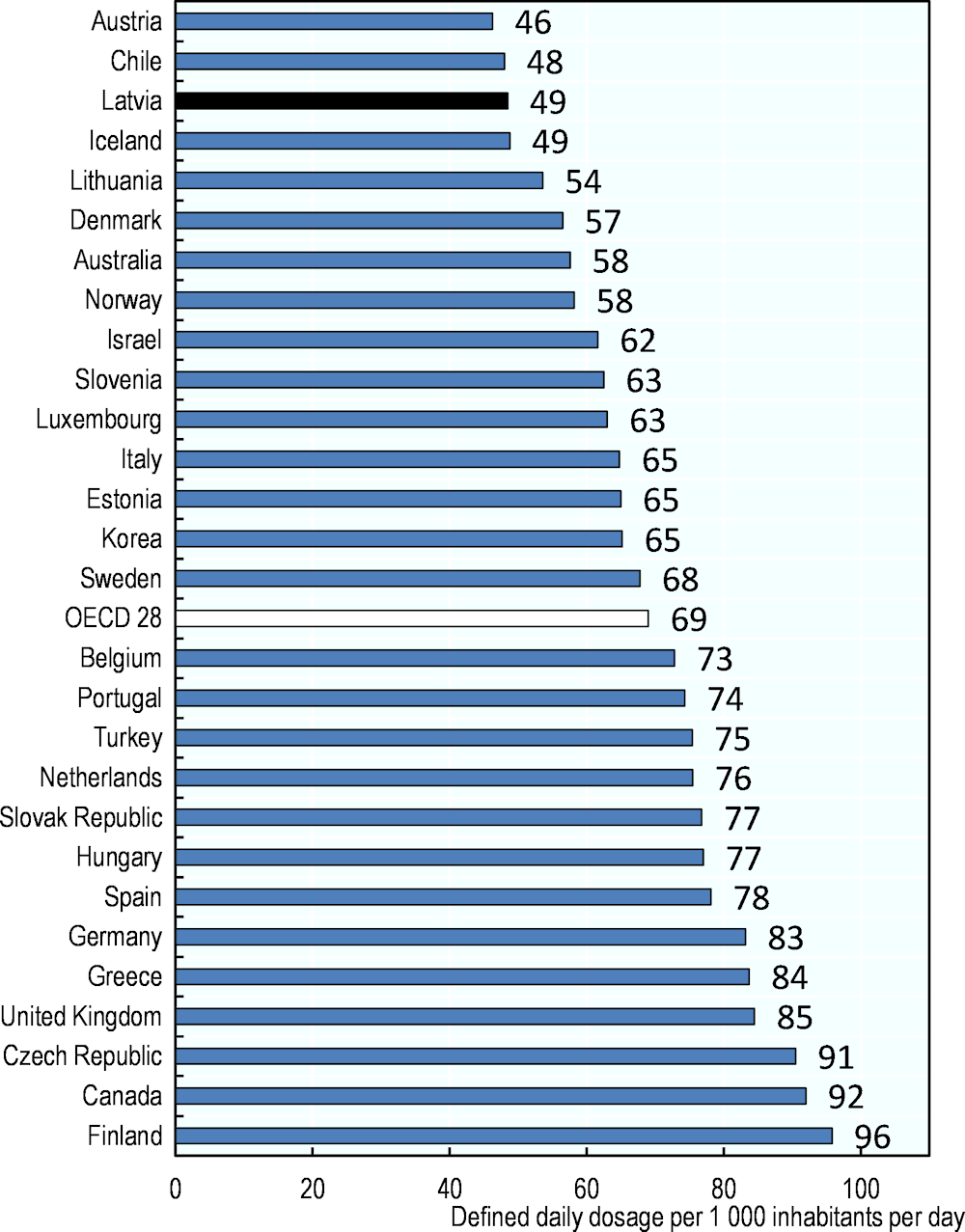

Diabetes is the fifth cause of death in Latvia and the mortality rate from this condition has increased by 50% between 2000 and 2016. The country also reports some of the highest mortality rates from this condition in the EU (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[16]). Yet, the use of anti-diabetic drugs in Latvia is among the lowest reported in the OECD (Figure 4.2). At 49 DDDs per 1 000 inhabitants per day it is nearly one‑third below the OECD average (69 DDDs per 1 000 inhabitants per day).

Figure 4.2. Oral antidiabetic drugs consumption, 2019 (or nearest year)

Note: Data refer to class A10.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

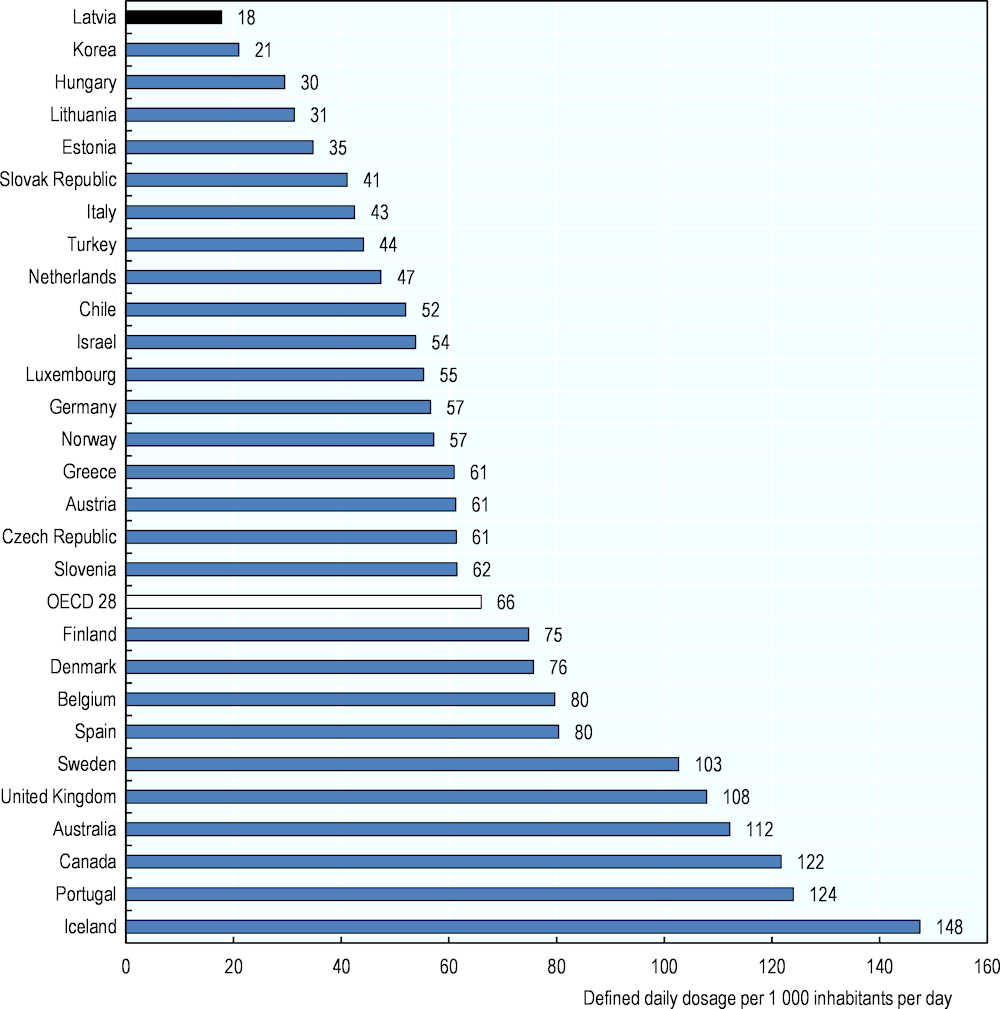

Mental health is also a major public health issue in Latvia. The country reports the second highest mortality rate from suicide in the EU (after Lithuania) and the fourth in OECD countries, with more than 18 deaths per 100 000 population in 2016 (OECD, 2019[21]). This is well above the OECD average (almost 12 per 100 000 inhabitants). Despite this, the level of anti-depressant consumption in Latvia is the lowest reported, 18 DDDs per 1 000 inhabitants per day, only one‑quarter of the OECD average and just over half of what is reported in Lithuania (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Antidepressant drugs consumption, 2019 (or nearest year)

Note: Data refer to class N06A-antidepressants.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

Analyses of the consumption figures of major groups of medicines in Latvia clearly show significant discrepancies with the actual burden of disease. This may be attributable in part to differences in medical practice or clinical guidelines, but is more likely to reflect financial and potentially other limitations in access to outpatient medicines for a substantial proportion of the population.

4.3.2. Spending on pharmaceuticals is low but represents a growing share of the health system’s budget

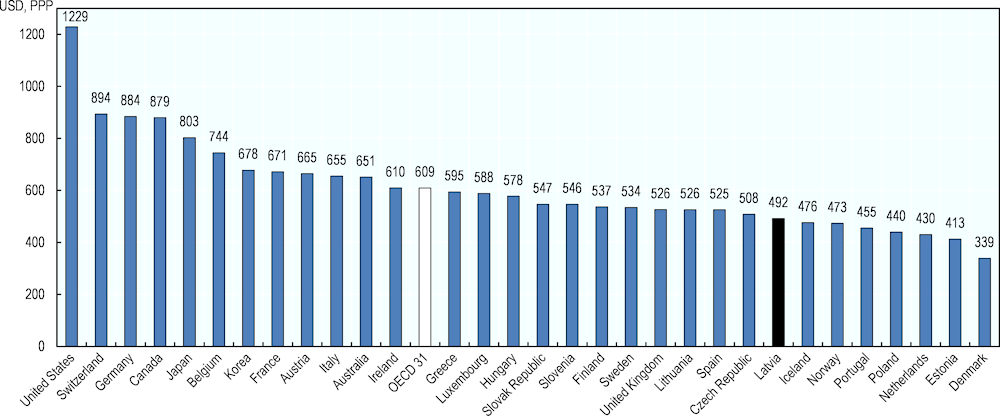

The low levels of medicines consumption in Latvia are linked to the low level of spending on medicines. In 2018, Latvia spent USD PPP 492 per capita on medicines (EUR 412, adjusted for purchasing power parity), among the lowest levels in the OECD (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Total spending on retail pharmaceuticals in USD per capita, 2018

Note: values are adjusted for Purchasing Power Parity.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

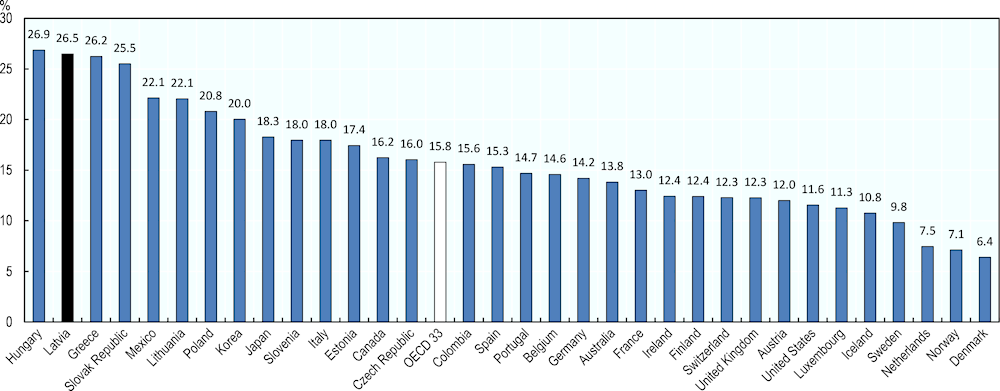

After inpatient and outpatient care, pharmaceuticals (excluding those used in hospitals) usually represent the third largest item of health care spending, accounting for 16% of health expenditure on average in OECD countries. Considering that demand for medicines is quite price inelastic, it is logical to expect that in countries with a smaller health care budget in absolute terms, pharma will absorb a more important share of their overall health budget. This explains in part why in Latvia outpatient medicines account for 27% of current expenditure in health (Figure 4.5), the second highest level in OECD countries after Hungary.

Figure 4.5. Retail pharmaceutical expenditure as a percentage of current expenditure on health, 2018

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

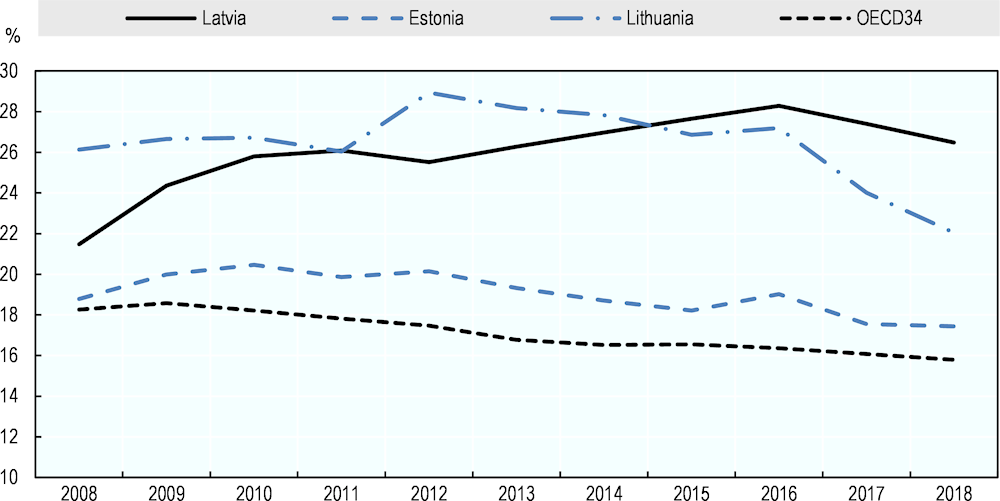

Over the past ten years, pharmaceuticals have represented a growing share of health expenditure in Latvia, accounting for 21% in 2008 and reaching 27% in 2017. This steady increase is striking when compared to the situation in the two other Baltic States, where the proportion of health expenditure on pharmaceuticals decreased or remained stable over the same period (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6. Evolution of retail pharmaceutical expenditure as a percentage of current expenditure on health

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

4.3.3. High out-of-pocket payments on outpatient medicines constitute a major barrier in access to care

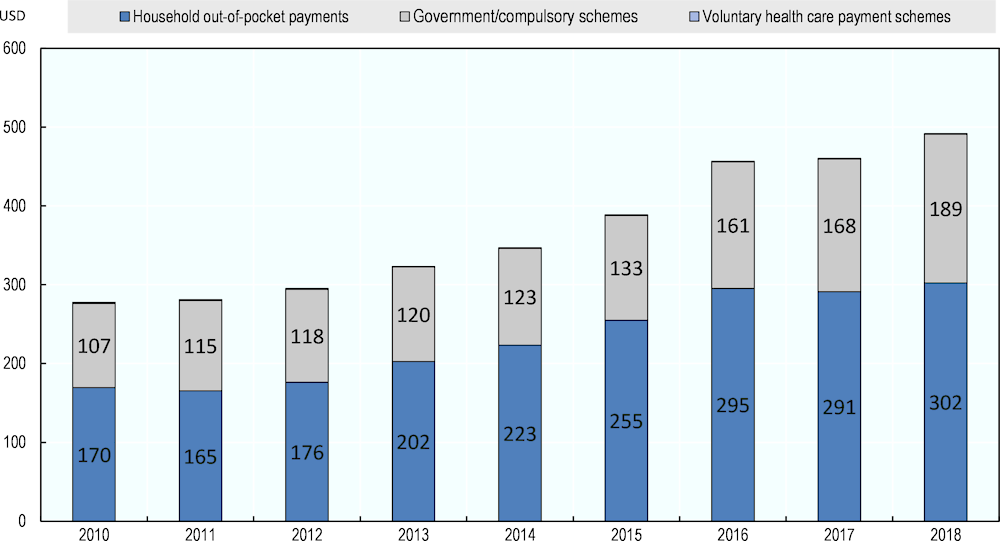

As shown in Figure 4.7, public expenditure on pharmaceuticals has increased at a slower pace than the overall growth in pharmaceutical spending, meaning that the proportion borne by patients increased over years. Out-of-pocket expenditure on pharmaceuticals accounted for 59% of total expenditure on medicines in 2011 (USD 165, EUR 176) and peaked at 65% (USD 255, EUR 213) in 2015.

Figure 4.7. Expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals by type of financing in Latvia, USD per capita

Note: contribution from voluntary health care payment schemes is marginal in Latvia and accounts for roughly USD 1 per capita each year.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

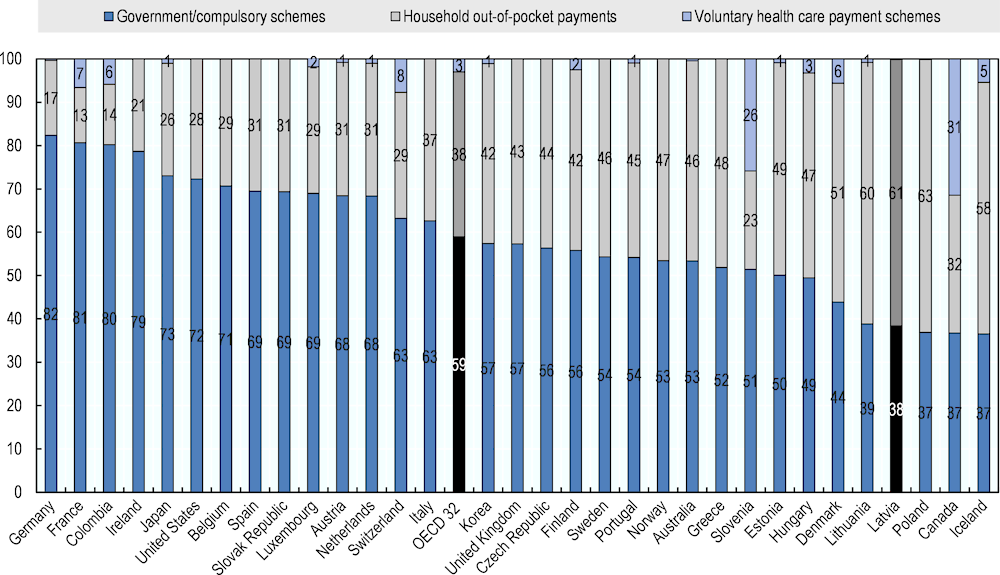

Across OECD countries, government programs and compulsory insurance schemes play the largest roles in pharmaceutical funding. On average, these mechanisms cover 59% of spending on pharmaceuticals. By contrast, in Latvia more than 60% of pharmaceutical spending is out-of-pocket payment, one of the highest proportions reported, and only 38% is publicly covered (Figure 4.8). This means that in Latvia the majority of the expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals is currently borne by patients themselves.

Figure 4.8. Expenditure on retail pharmaceuticals¹ by type of financing, 2018 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

Financial barriers in access to care are a frequently reported issue in Latvia. The proportion of the Latvian population reporting unmet needs for medical treatment is among the highest in Europe. In 2017, 6.2% of the population reported having foregone medical care due to costs, distance to travel, or waiting times – well above the EU average of 1.7%. Moreover, financial barriers to access disproportionately affect lower income groups. In 2017, Latvians in the lowest income quintile reported much higher levels of unmet needs for medical and dental care due to cost (9.9% and 25.5% respectively) than those in the highest income quintile (0.9% and 3.3% respectively) (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[16]).

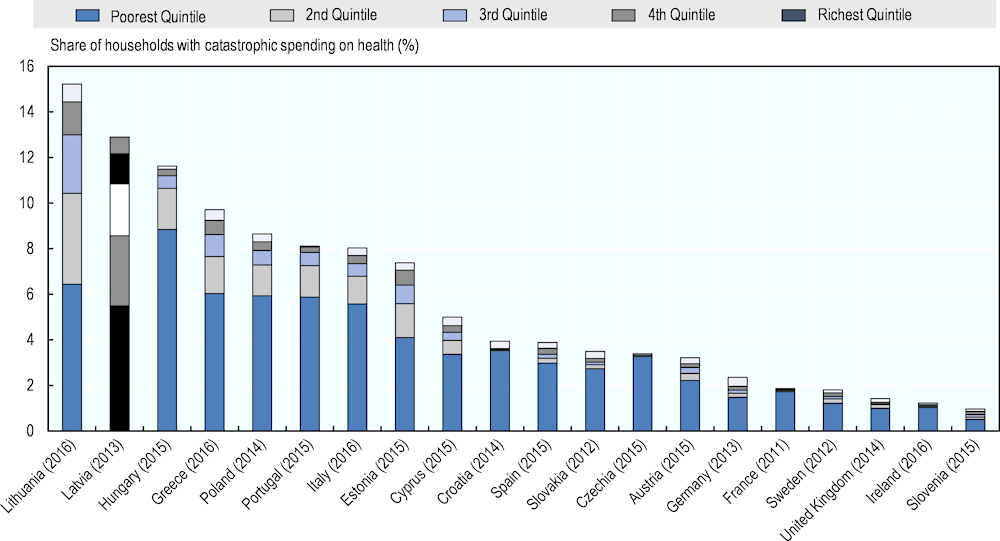

Difficulties in accessing care are closely related to the high levels of out-of-pocket spending in Latvia, reaching 39% of total health expenditure in 2018 (the second highest level in the EU) (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[16]). Such high levels of direct payments by patients are responsible for the high incidence of catastrophic health spending in Latvia. In 2013, almost 13% of the Latvian population experienced catastrophic health spending (see Box 4.7 and Figure 4.9), a major increase from the 2010 level of 10.6% and the second highest proportion documented in the EU. The incidence of catastrophic health spending is heavily concentrated among the poorest quintile of the population. Importantly, in all quintiles catastrophic spending was almost exclusively due to the costs of outpatient medicines. Outpatient medicines accounted for about 70% of all catastrophic out-of-pocket payments, rising to around 80% for the poorest quintiles (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018[8]).

Figure 4.9. Share of households with catastrophic spending on health by consumption quintile, latest year available

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[8]), “Can people afford to pay for healthcare? New evidence on financial protection in Latvia”.

Box 4.7. Catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditure

Also referred to as catastrophic spending on health, it is an indicator of inadequacy of financial protection and is defined as out-of-pocket expenditure exceeding 40% of a household’s capacity to pay for health care.

Catastrophic health spending includes:

Households that are impoverished: A household is considered impoverished if its total consumption was above the national or international poverty line or basic needs line before out-of-pocket payments and falls below the line after out-of-pocket payments.

Households that are further impoverished: A household is further impoverished if its total consumption is below the national or international poverty line or a basic needs line before out-of-pocket payments and if it then incurs out-of-pocket payments.

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[8]), “Can people afford to pay for healthcare? New evidence on financial protection in Latvia”.

Access to outpatient medicines accounts for half the total out-of-pocket payments reported by Latvian households. Several studies have shown that financial barriers to accessing necessary medicines are strongly correlated not only with poorer health outcomes but also increased use and cost of other health services (Goldman, Joyce and Zheng, 2007[3]; Kesselheim et al., 2015[22]). In the case of Latvia, the high levels of out-of-pocket payment on pharmaceuticals are related to the limited size of the public budget for health (government and compulsory health insurance schemes represent only 57% of the current expenditure on health as opposed to 79% in the EU on average) (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[16]) but also to the general arrangements of the reimbursement system.

Outpatient medicines are a key source of financial hardship because of the reliance on patient out-of-pocket payments (in this case, in the form of co-insurance, which is rather regressive1), the existence of a prescription fee, the exclusion of medicines from the annual cap on out-of-pocket payments and the rather limited size of the positive list (see below). In addition, the reimbursement system is structured around a reference price for each molecule, which creates the possibility of extra financial burden for patients (as they may have to paying an extra co-payment if the cheapest alternative is not available or entirely out of pocket if they choose not to accept it). The Ministry of Health estimates that in 2017, EUR 25 million were paid by patients because they were not provided with (or did not choose) the cheapest available alternative of a prescribed reimbursed medicine.

In order to improve access to outpatient medicines, in July 2019 the Latvian Government approved amendments to regulations on the reimbursement of medicines. The objective is to reduce the cost of medicines and patient co-payments for reimbursable medicines via better price control. In accordance with this new regulation, as of April 2020, the following measures are enforced:

The external reference pricing system will be revised and the basket of reference countries changed.

A price ceiling for medicines subject to reference pricing will be introduced (the most expensive alternative will have to be less than double the price of the cheapest one).

At least 70% of a doctor’s yearly prescriptions must be by International Non-proprietary Name (INN, see Box 4.8), which should improve the dispensing by pharmacists of least priced alternatives.

For medicines subject to internal reference pricing, it will be mandatory for pharmacies to keep stocks of the cheapest alternative.

Box 4.8. INN (International Non-proprietary Name) prescribing

INN prescribing refers to the requirement for prescribers to specify each medicine using its International Non-proprietary Name (INN) – i.e. the active ingredient name instead of the brand name – on a prescription. This enables the pharmacist to provide the patient with differently-priced alternatives for the same multi-source drug.

INN prescribing may be allowed (indicative INN prescribing in, for example, Germany, Ireland, Hungary) or required (mandatory/obligatory INN prescribing in, for example, France, Estonia, Lithuania, Italy).

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[9]), “Medicines Reimbursement policies in Europe”.

Another policy that partially explaining the high level of out-of-pocket payments for pharmaceuticals is the exclusion of outpatient medicines from the general cap on user charges. User charges per person per year for all publicly financed health services, except outpatient medicines, are capped at EUR 569 per year. This is a relatively large amount in Latvia, equal to one and a half month’s minimum wage, and is unlikely to offer protection for poorer households. Only a few population groups are exempt from cost-sharing for outpatient medicines: e.g. households with an income below EUR 128 per family member per month, asylum seekers, and patients under 18. While there is no overall cap on out-of-pocket payments for outpatient medicines or for other health services in the other Baltic states, reforms introduced in recent years in both Estonia and Lithuania have reduced the financial burden related to outpatient medicines, see Box 4.11 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018[8]).

The size and content of the positive list may also contribute to the high levels of out-of-pocket costs for medicines. Of the 4 252 products registered in Latvia, 1 760 (41%) are at least partially reimbursed by the NHS (i.e. products that are part of one of the reimbursement lists). However, some core essential medicines such as aspirin (anticoagulant), glibenclamide (anti-diabetic), penicillin and erythromycin (antibiotics) are currently not among the reimbursed products. The WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (World Health Organization, 2019[23]) serves as a guide for the development of national and institutional essential medicine lists and is updated and revised every two years by the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Medicines. The latest edition details the 433 drugs deemed essential for addressing the most important public health needs globally. A high-level comparison with the list of molecules reimbursed by the Latvian NHS reveals that only 165 of 433 (40%) of the molecules currently reimbursed in Latvia are also part of the WHO Model List. This figure implies two things: first, that some important medicines are not covered by the NHS (some of them are mentioned in the previous paragraph); second, that at the same time the NHS reimburses a large number of medicines molecules that do not necessarily constitute a priority. One example is fixed-dose combinations, which may reflect inefficient spending as they can often be more expensive than the aggregate costs of the constituent products2 (Hong, Wang and Tang, 2013[24]; Sacks et al., 2018[25]).

Overall, the current reimbursement system for outpatient medicines in Latvia does not provide adequate protection against the costs of ill-health. The co-insurance rate of 25% or 50% for many medicines (100% where the reference product is declined) associated with a reimbursement amount calculated on a reference price, disproportionately affects patients suffering from chronic diseases and those with conditions requiring more expensive medicines. Comprehensive exemption arrangements for co-payments on reimbursed outpatient medicines are also missing. While targeted exemption from co-payments applies to some population groups such as children under 18 years, vulnerable groups such as pensioners or patients suffering from chronic conditions do not receive any form of protection against the financial burden of the costs of their medicines.

Improving access to needed therapeutics in Latvia requires a major review of the reimbursement system, including an examination of how reimbursement decisions are made and motivated, but also an increase in the funds available, through both additional public investment and disbursement of savings achieved through improved efficiency.

4.3.4. Expenditure on pharmaceuticals is not very efficient

Many countries view generic and biosimilar markets as an opportunity to increase efficiency in pharmaceutical spending. In Latvia, the first prescription of a reimbursed medicine must in theory include its International Non-proprietary Name (INN), and for multi-source medicines, pharmacists are obliged to propose to patients the cheapest versions of the medicines prescribed. In addition, pharmacists are allowed to substitute pharmaceutical products prescribed by brand name with generics unless the prescribing doctor has expressly stated otherwise.

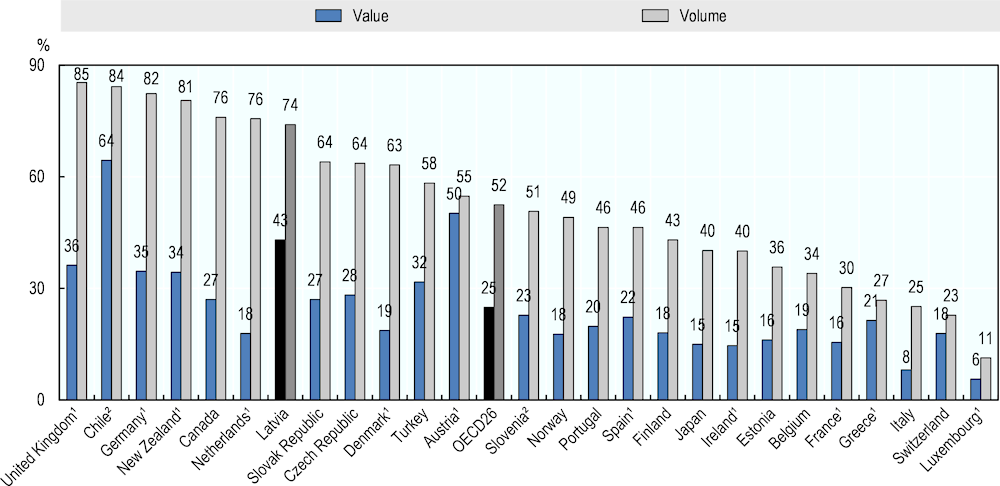

In Latvia, the market penetration of generic medicines is quite substantial. Generics represent 74% of the market by volume (see Figure 4.10), one of the highest levels in the OECD, and some 20 percentage points above the OECD average. In terms of value, generic medicines account for 43% of the total pharmaceutical market. This level is also high when compared with countries with similar levels of generic penetration by volume (Canada, the Netherlands) and may reflect higher prices of generics relative to other medicines (off-patent originators and on-patent medicines).

Figure 4.10. Share of generics in the total pharmaceutical market, 2017 (or nearest year)

Note: 1. Reimbursed pharmaceutical market. 2. Community pharmacy market.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

Despite the level of generic penetration, distrust in generic medicines is frequently reported among prescribers and patients in Latvia, which may limit further efficiency gains. Indeed, people’s preferences are an important obstacle in implementing effective generic policy. Several studies report that a high proportion of patients tend to believe that generic medicines are of lower quality and less effective than originator medicines, and as a result may feel negatively about policies promoting their utilisation (Colgan et al., 2015[26]). A recent study conducted in Latvia estimated that only 21% of the population would opt for generic medicines and that the opinion of a physician was the most important factor when choosing between generic and brand-name medicines (Salmane Kulikovska et al., 2019[27]). Such distrust towards generics may partly explain why, as previously noted, patients paid EUR 25 million out-of-pocket in addition to the statutory user charges in 2017, by choosing a more expensive alternative than the reference priced product. It is therefore important that both the authorities and health care professionals provide objective and unbiased information about generic medicines to patients to increase their acceptance.

Latvia should also do more to increase spending efficiency with generics. Many countries have implemented incentives for physicians and pharmacists to boost generic markets, which can lead to price reductions. Over the last decade, France and Hungary, for example, have introduced incentives for GPs to prescribe generics through pay-for-performance schemes. In Switzerland, pharmacists receive a fee for generic substitution; in France, pharmacies receive bonuses if their substitution rates are high, see Box 4.12 (OECD, 2019[21]). In Latvia, there are currently no financial incentives for doctors to prescribe more generics nor for pharmacists to dispense cheaper alternatives (since margins are the same for all the products, generics and originators). Possible options to consider are discussed in the next section but could for example include the introduction of incentives related to generic prescribing as part of general practitioners’ pay-for-performance program; the creation of a specific distribution margin system for generics for pharmacists or the application of a fixed retail distribution margin or mark-up for generics (i.e. an absolute value) at the same level as, or even higher than that of the originators. Indeed, current retail margins, which are linked to wholesale prices, make the selling of cheaper alternatives unattractive to pharmacists.

Facilitating the market entry and inclusion in the positive list of biosimilars could also lead to substantial savings on costly medicines. Biological medicines contain active substances from a biological source, such as living cells or organisms. When such medicines no longer have monopoly protection, “copies” (called biosimilars) of these products can be approved. Biosimilars can create price competition and improve affordability. A biosimilar is granted regulatory approval by demonstrating sufficient similarity to its reference biological product in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety and efficacy. In Latvia, the potential of biosimilars has not been fully realised. Indeed, regulatory arrangements dictate that an off-patent medicine may only be added to the positive list if the originator is already reimbursed. In the case of biosimilars, some originators are very expensive biological medicines that the authorities may have decided not to add to the reimbursement list for financial reasons, thus blocking the inclusion of any subsequent biosimilar version despite a more affordable price. Changing such arrangements could allow the introduction of biosimilars of reference products not yet reimbursed, which would improve patients’ access (see Box 4.9). Biosimilar uptake could be further increased using other incentives commonly in place in other countries (incentives for prescribers, substitution by pharmacists, etc.).

Box 4.9. Biosimilars increase price competition and foster patient access

The effects of biosimilar introduction on the concerned therapeutic areas has been evidenced in the literature. In the seven therapeutic areas with biosimilar competition, average list prices in European countries have reduced since the introduction of these products (e.g. ‑17% for anti-tumour necrosis factor, ‑6% for insulins). In addition, the correlation between biosimilar volume market share and price reduction is weak. In other words, substantial savings can be achieved even when the market share of the biosimilar remains low.

Lower prices can reduce pharmaceutical expenditure but can also foster patients’ access. For most concerned therapeutic classes, there has usually been a greater increase in consumption since biosimilar entry in countries that had low starting volumes. In classes where biosimilars have been on the European market for several years (e.g. erythropoietin), there are now many examples of countries where biosimilars account for 100% of the market share for some products. This is particularly true in countries where the reference product was not always available prior to the market entry of the biosimilar(s) (e.g. Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Poland), meaning that access to the biologic was only possible once biosimilars entered the market.

Source: QuintilesIMS (2017[28]), “The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe”, www.quintilesims.com.

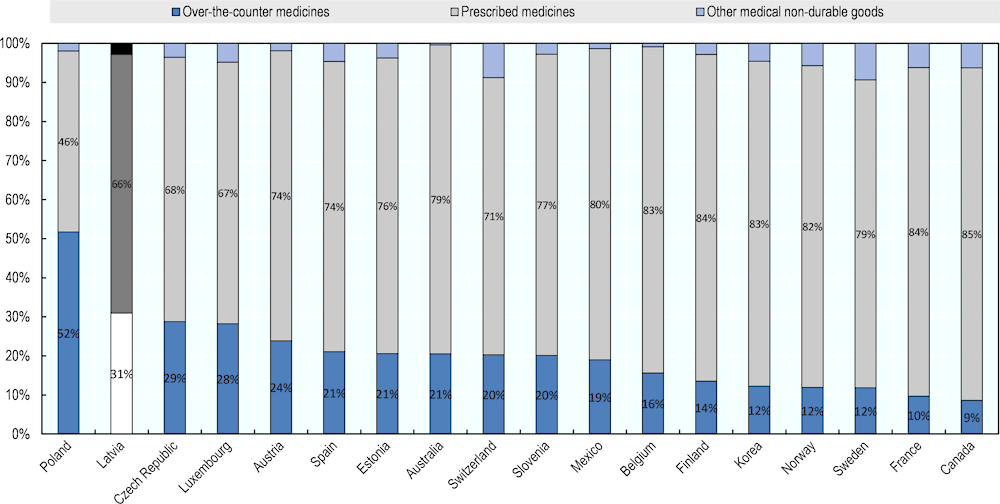

Finally, it is also important to note that in Latvia roughly one‑third of all pharmaceutical expenditure goes to over-the-counter medicines (Figure 4.11). The extent of use of non-prescription medicines is among the highest reported in OECD countries and further contributes to the high levels of out-of-pocket expenditure. One possible contributing factor may be the overall structure of the retail sector, where a very competitive environment may be encouraging community pharmacies to push sales to increase income. Clearly further investigation of this issue is warranted.

Figure 4.11. Retail pharmaceutical spending by type of product, 2018

Note: share of retail pharmaceutical spending by type of product.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), OECD Health Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9.

4.3.5. The current structure of the community pharmacy sector raises concerns

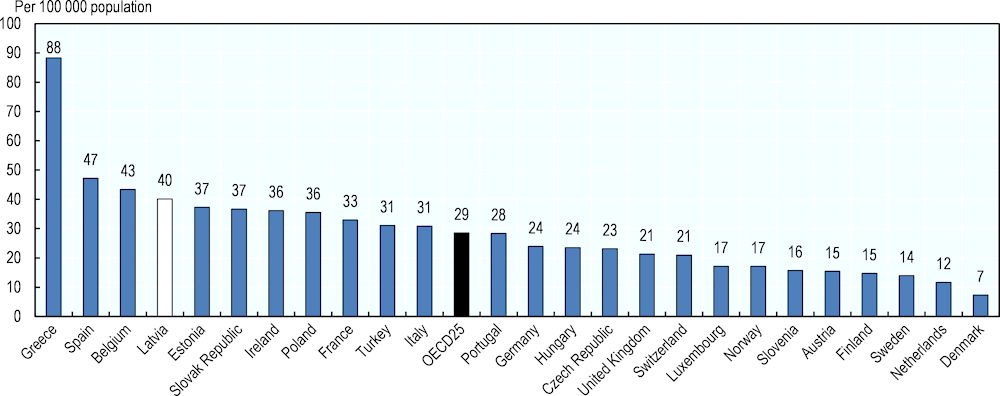

As previously noted, the retail pharmacy sector in Latvia reflects a high level of horizontal integration. In OECD countries, the number of community pharmacies per 100 000 population ranges from seven in Denmark to 88 in Greece; with an average of 29 (Figure 4.12). This variation can be explained in part by differences in common distribution channels (some countries relying also on hospital pharmacies to dispense medicines to outpatients while others, like the Netherlands, still have doctors dispensing medicines to their patients). Latvia reports 40 community pharmacies per 100 000 inhabitants, the fourth highest rate in the OECD.

Such a high figure may not necessarily be a problem unless the pharmacies are poorly distributed across the country. In fact, the density of pharmacies is extremely high in Riga and in the big urban centres, but much lower in rural areas. In addition, the high urban density of pharmacies may induce an increased degree of competition among them. As a result of an increasing trend towards horizontal and vertical integration in the Latvian retail pharmaceutical sector, many pharmacies are now owned by wholesalers who have an interest in supplying “their” pharmacies with the products they distribute. Financial pressure on pharmacies is high and they tend to carry minimal stocks, and this can impair patient access. A national poll released in August 2020 reported that almost two‑thirds of users of state-reimbursed medicines had experienced lack of availability of prescribed reimbursable medicines in retail pharmacies in the preceding months. In 29% of cases, the situation was resolved by purchasing medicines in another pharmacy. Increased competition also encourages pharmacists to sell more over-the-counter medicines and to dispense higher priced alternatives to patients to ensure their financial survival. Overall, the high density of pharmacies in Latvia constitutes an additional factor contributing to patients’ difficulties in access to and affordability of medicines.

Figure 4.12. Community pharmacies, 2017 (or nearest year)

Source: Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) Database 2017 or national sources.

In addition, the role of pharmacists as providers of public health services is not sufficiently recognised or valued in the country. Indeed, the role of the community pharmacist has changed over recent years in most OECD countries. The increasing burdens of chronic disease and multi-morbidity require them to tailor advice to the complex needs of individual patients, while the shift away from hospital care means pharmacists are increasingly providing other services, within community pharmacies or as part of integrated health care teams. Although their main function remains to dispense medications, community pharmacists are increasingly providing direct care to patients as well as medicine adherence support. In Latvia, no specific public health function is currently devolved to pharmacists, despite an expressed willingness to contribute more to the general public health effort. Their contribution could, for example, include more reviews of patients’ prescription regimens, vaccination services or monitoring of certain health metrics (e.g. HbA1c).

4.4. Reforming certain features of the Latvian pharmaceutical sector would improve patient access and safeguard public spending

This chapter has described the current situation of the outpatient pharmaceutical market in Latvia. Overall, the pharmaceutical system possesses solid and well-functioning institutions and the regulation of the sector is well-defined. Prices of all medicines are regulated and the reimbursement procedure and management of the positive list rely on objective principles.

However, outpatient medicines not only represent a growing challenge for public finances but at the same time patient access is becoming more and more difficult. Indeed, pharmaceuticals represent more than one‑quarter of current health expenditure, but Latvians still bear directly the costs of almost two‑thirds of pharmaceutical expenditure.

The current situation can be explained by a conjunction of various elements. First and foremost, the low level of public expenditure on health limits the number of medicines that may be publicly covered. Second, the current reimbursement system is not providing adequate protection for patients (and particularly vulnerable populations) from the costs of ill health. Third, the health system is not optimising the expenditure of current pharmaceutical budgets because some of its features (such as broad misconceptions around generic medicine and prescribing by brand name) lead to substantial inefficiencies. Finally, the configuration of the retail pharmaceutical market sector gives rise to misaligned competitive behaviours and does not foster access.

The policy options shown below have been developed based on these findings. They are organised around each of the functions of the pharmaceutical sector and are intended to improve patient access to outpatient medicines while at the same time supporting the authorities in their efforts to control the rising costs of this dimension of the health system. They are summarised in Table 4.6 together with the likely financial implications. However, it should be reiterated that increased public investment in health in general, and in pharmaceuticals in particular, is needed. Overall, Latvia spends much less on health per capita and as a share of GDP than most other OECD countries. Such low levels of public spending on health reflect the relatively small size of government (public spending represents 37% of GDP) but also the relatively low priority given to health, as less than 9% of overall public spending is allocated to this sector, compared with an average of 16% in the EU as a whole. Significant progress in access to medicines will remain extremely difficult if the level of resources invested in the system is not increased.

Table 4.6. Overview of the suggested policy actions

|

Low or limited financial implications |

Substantial financial implications |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Increase public investment on outpatient medicines |

√ |

||

|

Adjustments to the pricing system |

Establish distribution mark-ups more favourable to generic medicines |

√ |

|

|

Introduce a ceiling to wholesalers’ mark-ups |

√ |

||

|

Disconnect community pharmacy remuneration from the prices of medicines |

√ |

||

|

Revisions of the reimbursement arrangements |

Review and revise of reimbursement lists |

√ |

|

|

Include co-payments on medicines in the calculation of the general cap on out-of-pocket payments |

√ |

||

|

Increase the reimbursement rate of pharmaceuticals included in the lowest reimbursement category |

√ |

||

|

Exempt additional, vulnerable population groups from co-payments on outpatient medicines |

√ |

||

|

Efficiency gains on pharmaceutical expenditure |

Improve the knowledge and acceptance of generic medicines among both patients and health professionals through public awareness campaigns |

√ |

|

|

Incentivize physicians to prescribe more generics |

√ |

||

|

Facilitate the reimbursement of biosimilars |

√ |

||

|

Improve public health responsibilities of community pharmacists |

√ |

||

4.4.1. Adjustments to the pricing system should be considered

As mentioned above, the regulation of prices in Latvia is well-established. Manufacturers’ prices of reimbursed medicines are controlled through External Price Referencing and the authorities have already initiated a revision of the reference countries, which goes in the right direction since the previous list included countries either not regulating prices (Denmark) and/or having higher GDP per capita (e.g. Czech Republic, Hungary).

However, the control of the distribution margins presents various issues. First, two regulations coexist: one for reimbursed and one for non-reimbursed medicines, without any obvious reasons to justify the dichotomy. Second, for medicines there is no ceiling to wholesalers’ mark-ups (see Table 4.4). This arrangement can be extremely costly for the third-party payer and by extension, for patients. Third, there is no difference in the regulation of the distribution margins for generics and originators. A single scale, with margins based on value, necessarily encourages pharmacists to dispense more expensive alternatives to increase their income.

Removing the differences in the regulation of margins between reimbursed and non-reimbursed products and replacing them with a scheme favouring generics can increase generic uptake, which can lead to price reductions. Pharmacists also need to be remunerated in a way that encourages them to dispense the least expensive products. Instead of mark-ups that encourage dispensing of more expensive drugs, fixed fees per prescription or differentiated mark-ups (between originators and generics for instance) could lead pharmacists either to equipoise, or create and incentive to dispense generics, respectively. Some countries recently changed their policies to incentivise pharmacists to dispense generics. In 2012, Portugal changed pharmacists’ remuneration from fixed (flat rate regardless of price) to regressive margins (decreasing margins with increasing prices). Other countries have gone even further. In Switzerland and Belgium, for example, pharmacists receive an additional fee for generics substitution. France introduced a pay-for-performance scheme for pharmacists in 2012 with a bonus for achieving generic drug dispensing targets, see Box 4.12 (OECD, 2017[29]).

Introducing a ceiling on wholesalers’ mark-ups could contribute to containing public expenditure on pharmaceuticals and reduce patients’ out-of-pocket expenditure. Most OECD countries regulate wholesalers’ mark-ups, relying either on a regressive scheme (as in Latvia), or on a linear scheme (as in Italy, Spain and Poland). Frequently, countries also limit the maximum possible mark-up for wholesalers; it is capped at EUR 30 in France and EUR 7.54 in Spain. As reported in Table 4.2 and Table 4.4, there is no similar ceiling on wholesalers’ margins for non-reimbursed and reimbursed medicines in Latvia.

Disconnecting community pharmacists’ remuneration from the price of medicines is also an option for consideration. A substantial number of OECD countries have uncoupled the prices of medicines and the remuneration of community pharmacists. In France, distribution margins comprised 81% of the remuneration of community pharmacists in 2014. In 2019, with the progressive introduction of various dispensing fees, this had declined to 26% (LEEM, 2019[30]). This evolution also limits the impact of price reductions on pharmacy incomes. This is particularly relevant as the determination of medicine prices do not involve pharmacy representatives, although affects their remuneration if it relies on mark-ups. Various countries have introduced prescription fees to complement the mark-up remunerations (e.g. Denmark, France), while others have in some aspects almost entirely disconnected remuneration from mark-ups (e.g. Australia, New-Zealand, see Box 4.10). Uncoupling medicines prices and pharmacy remuneration in Latvia could facilitate better control of pharmaceutical expenditure while safeguarding pharmacy remuneration.

Box 4.10. Remuneration of pharmacists under the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

Remuneration of pharmacists for prescriptions subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia made up of two elements: dispensing fees and “administration, handling and infrastructure” (AHI) fees.

Dispensing fees for medicines reimbursed by the PBS depend on the nature of medicine concerned (e.g. ready-prepared, dangerous medicine, etc.).

AHI fees were introduced in 2015 to replace the former six‑tier pharmacy mark-up. The objective was to partially de-link pharmacy remuneration from the prices of medicines, so that changes in pricing policy would have less impact on pharmacy remuneration.

AHI fees vary according to the listed PBS prices of the medicines. If the price is

less than AUD 180 (USD 118), the AHI fee is AUD 3.54 per dispensing (USD 2.30);

between AUD 180 to 2 089.71, the AHI fee is AUD 3.54, plus 3.5% of the amount by which the price to pharmacy exceeds AUD 180 per dispensing;

more than AUD 2 089.71 (USD 1 365), the AHI fee is AUD 70 per dispensing (USD 46).

Source: Deloitte (2016[31]), Remuneration and regulation of community pharmacies.

4.4.2. The reimbursement system needs to be substantially revised

The structure of the reimbursement system is complex, and at times confusing. In particular, the rationale for the use of three levels of reimbursement is difficult to understand and the basis for the allocation to different levels is unclear. For example, a medicine that is reimbursed at 75% for an asthmatic patient may only be reimbursed at 50% for a patient with COPD.

Also, as demonstrated in the previous sections, the current features of the system do not provide adequate financial protection for patients. The range of medicines publicly covered is arguably insufficient, with several essential medicines missing from the reimbursement lists. There is also no cap on co-payments which disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, such as patients with chronic conditions.

Revising the current positive lists (list A; B, C and M) to add some current important therapeutic options not currently covered, specifically those targeting the biggest health issues in Latvia (cardiovascular disease, mental illness, diabetes), would improve patient access. As presented in the previous sections, of the 4 252 products registered in Latvia, 1 760 (41%) are at least partially reimbursed by the NHS (i.e. part of one of the positive lists). A comparison of the reimbursement lists with the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines showed that only 165 of 433 (40%) molecules on the EML were currently reimbursed in Latvia. This implies that some essential medicines are not covered by the NHS and that the NHS provide coverage of many medicines that may not necessarily constitute a priority (such as combination products). A revision of the content of the positive lists would enable better alignment of the benefit package with the burden of disease in the Latvian population. Further clarification of how these lists are reviewed and revised would also be helpful.

In addition, the overall level of out-of-pocket payments on outpatient medicines should be reduced through a combination of the following measures:

Include co-payments on medicines in the calculation of the general cap on out-of-pocket payments and lower the overall threshold of this cap to enhance the degree of financial protection.

Consider revising the reimbursement arrangements, starting with an increase in the reimbursement rate of pharmaceuticals included in the lowest reimbursement category (50% of the price of the cheapest alternative is reimbursed); a possible option could be to include all the medicines part of it into the current 75% reimbursement category.

Designate additional vulnerable populations from co-payments on outpatient medicines (for example, pensioners ).

As already reported, several publications have shown that financial barriers to accessing necessary medicines are not only strongly correlated with poorer health outcomes, but also with increased use of and expenditure on other health services. In the case of Latvia, outpatient medicines are the most important source of financial hardship because of the general structure of the reimbursement scheme: the reliance on co-insurance rather than flat co-payments, the existence of a prescription fee, and the exclusion of medicines from the annual cap on out-of-pocket costs. This system disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, such as people on low-incomes and those with chronic conditions. Co‑insurance payments – that is, co-payments set as percentage of the price - are inequitable, and shift financial risk from the payment agency to the patient, thereby exposing them to health system inefficiencies. Caps in overall out-of-pocket spending can protect people if they are applied to all patient contributions over time, rather than being focused on specific items or types of service. In the case of Latvia, excluding outpatient medicines from the general calculation of the cap on out-of-pocket payments weakens the protection the cap provides to patients, since the majority of out-of-pocket costs arise from outpatient medicines. The measures suggested above could transform the reimbursement arrangements in ways that would substantially improve the Latvian population’s protection from the costs of ill-health. The other Baltic states have made substantial progress on that direction in recent years and their experiences could inform system redesign (see Box 4.11).

Box 4.11. The other Baltic States have implemented successful policies to reduce out-of-pocket payments on medicines

Estonia

All patients in Estonia are required to make a co-payment for their outpatient medicines. Some vulnerable populations (e.g. people on low incomes, pensioners) can get these co-payments reimbursed but until 2018, the complexity of the system frequently prevented eligible people from claiming the reimbursements to which they were entitled. In 2018, the government reformed the system to enhance protection against high out-of-pocket costs. When a patient’s spending on prescriptions in one year exceeds EUR 100, the government immediately covers 50% of any further costs until the patient has spent EUR 300 in total, after which the government pays 90% of any subsequent costs. Unlike the preceding system, patients are not required to apply for this benefit and wait to be reimbursed, it is calculated automatically by the pharmacy’s information system.

As a result, out-of-pocket payments for prescription medicines have been significantly reduced in Estonia: in 2017, only 3 000 people benefited from additional reimbursement, but this rose to 134 000 in 2018. The number of people spending more than EUR 250 annually on outpatient prescriptions fell from 24 000 in 2017 (2.8% of the population) to 1 000 in 2018 (0.1%).

Lithuania

While there are no formal user charges for primary, outpatient and inpatient care, until recently, patients faced substantial co-payment for outpatient medicines in Lithuania. A number of measures have been taken since 2017 to decrease the level of out-of-pocket payments on pharmaceuticals. These include an increase in the reimbursement levels and caps on the price differences between the prices paid at pharmacy level and the reference reimbursement prices.

As a result, the average co-payment per prescription decreased from EUR 3.4 in 2017 to EUR 2.3 in 2019, and the share of OOP expenditure on reimbursable medicines decreased from 21.2% in 2016 to 6.8% in the first quarter of 2019.

Source: OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2019[16]), Latvia: Country Health Profile 2019, https://doi.org/10.1787/b9e65517-en. WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018[33]), Can people afford to pay for healthcare? New evidence on financial protection in Estonia.

4.4.3. While more public investment is required, some efficiency gains could be made

As mentioned above, some efficiency gains could be pursued that would support patient access while at the same time contributing to the control of the public spending on pharmaceuticals. The recent decisions of the authorities to have at least 70% of the prescriptions written using INNs is a step in the right direction, as is the introduction of a ceiling on the prices of reimbursed medicines. However, widespread misconceptions about generic medicines will remain an obstacle to any attempts to increase their uptake.

Improving the knowledge and acceptability of generic medicines among patients and health professionals is necessary. This could be achieved via new information campaigns and further efforts around initial and continuous professional education. Several countries have carried out information campaigns to promote the use of generics, explaining their equivalence and interchangeability with originator medicines (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain). While no formal evaluation is available, these policies, together with patent expiries of several blockbusters in recent years, have contributed to the significant increases in the market share of generics observed over the past decade in several countries (OECD, 2017[29]).

Physicians also need to be incentivised to prescribe by INN. They can be encouraged to prescribe cheaper products by creating explicit guidelines on the prescription of the cheapest alternative as first-intention medication or nudged by prescription software that highlights price differences for products which are therapeutically equivalent. Financial incentives can also be used to encourage them to prescribe generics. Several countries use financial incentives targeting prescribers. In Belgium, since 2005, physicians who issue at least 400 prescriptions annually are evaluated on whether they prescribe a certain required percentage of “cheap medicines”. The scheme, updated in 2015, has set between 16% and 65% target share of “cheap medicines” across different medical specialities, with an average of 42%. Germany uses similar target levels and has introduced financial penalties for physicians who do not reach them. In recent years, France (in 2009) and Hungary (in 2010) introduced incentives for GPs to prescribe generics through a pay-for-performance (P4P) scheme (see Box 4.12) (OECD, 2017[29]).

Box 4.12. Policies fostering generic uptake have led to substantial savings in France

Over the past two decades, France introduced a comprehensive set of policies to foster the utilisation of generics, which led to substantial savings.

Incentives towards pharmacists:

Three policy options have been introduced to encourage pharmacists to dispense generic medicines in France:

Since 1999, pharmacies’ mark-ups on generic medicines are generally the same as those of the originators (in absolute value).

A pay-for-performance scheme (Rémunération sur objectifs de santé Publique, ROSP) was created, rewarding pharmacists based on the rate of generic substitutions recorded in their pharmacies. For most molecules, the bonus begins at a substitution rate of about 75%, and increases up to a target substitution rate of 85%. In 2013, pharmacies earned an average of EUR 6 000 under the scheme (for a total cost to the national health insurance fund of EUR 135 million).

Discounts (also known as back margins) granted by pharmaceutical companies to pharmacists are regulated by the State. In order to further encourage generic dispensing, the maximum authorised discounts for generic drugs are higher than those for originators. In addition, since 2014, the gap between generics’ and originators’ authorised discounts has been increased to up to 40% of the generic list price (against 17% previously) compared with 2.5% for originators.

Incentives towards doctors:

For physicians, measures to increase generic uptake have primarily been targeted at modifying prescribing behaviour:

Physicians must be able to provide a clinical justification for any prescription for which they decline to permit generic substitution. The Health Insurance Fund can penalize a prescriber who cannot provide a clinical basis for his decision.

Since 2015, prescription by INN has been mandatory.

A pay-for-performance scheme (ROSP) also exists for physicians, and represents a substantial share of GP income (roughly 10%). Almost a quarter of the objectives defined of the scheme are aimed at increasing the share of prescriptions dispensed as generics.

Incentives towards patients:

The “third-party payer in exchange for generics” (tiers-payant contre génériques) system was implemented in July 2012. Under this system, third-party payment is granted only if a patient agrees to accept a generic instead of the originator (with the exception of those listed as non-substitutable on the prescription form). This means that if a patient still wants the originator, the reimbursement level will be the same as for the generic but the patient will have to pay for the entire prescription upfront and claim reimbursement afterwards instead of having to pay only the co-payment at point of sale.

Results