This chapter presents an overview of the education system in Scotland (United Kingdom) and introduces the background to the implementation of Curriculum for Excellence (CfE). It describes the framework and methodology used by the OECD team to assess the processes and progress made with the implementation of CfE in Broad General Education and the Senior Phase and to propose possible developments in the future. Finally, it takes stock of transversal tensions around CfE that inform the analysis in the following chapters.

Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence

1. The Scottish education system in context

Abstract

Introduction and methodology

In 2019, the Scottish Government invited the OECD to conduct an assessment to take stock of the implementation of its Curriculum for Excellence policy (CfE) and identify areas for potential development in the future to ensure that it contributes as effectively as possible to the education of young people in Scotland. This report presents the results of the assessment. It was developed as part of the OECD Implementing Education Policies programme (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. Implementing Education Policies: Supporting change in education

OECD’s Implementing Education Policies programme offers peer learning and tailored support for countries and jurisdictions to help them achieve success in the implementation of their education policies and reforms. Tailored support is provided on topics on which the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills has comparative expertise, including (but not limited to): introducing new curricula, developing schools as learning organisations, teacher policy, evaluation, assessment and accountability arrangements/education monitoring systems and building educational leadership capacity. The tailored support consists of three complementary strands of work that aim to target countries’ and jurisdictions’ needs to introduce policy reforms and impactful changes:

Policy assessments take stock of the selected policy and change strategy, analyse strengths and challenges and provide concrete recommendations for enhancing and ensuring effective implementation. They follow a concrete methodology: a desk study of policy documents, a three to five-day assessment visit, in which an OECD team of experts interviews a range of key stakeholders from various levels of the education system, and additional exchanges with a project steering or reference group.

Strategic advice is provided to education stakeholders and tailored to the needs of countries and jurisdictions. It can consist of reviewing policy documents (e.g. white papers or action plans), contributing to policy meetings or facilitating the development of tools that support the implementation of specific policies.

Implementation seminars can be organised to bring together education stakeholders involved in the reform or change process for them to discuss, engage and shape the development of policies and implementation strategies.

CfE is Scotland’s comprehensive curriculum policy, developed between 2004 and 2010 and first implemented in 2011. With more than 16 years since its inception, it is an opportunity to review its implementation with a focus on its future.

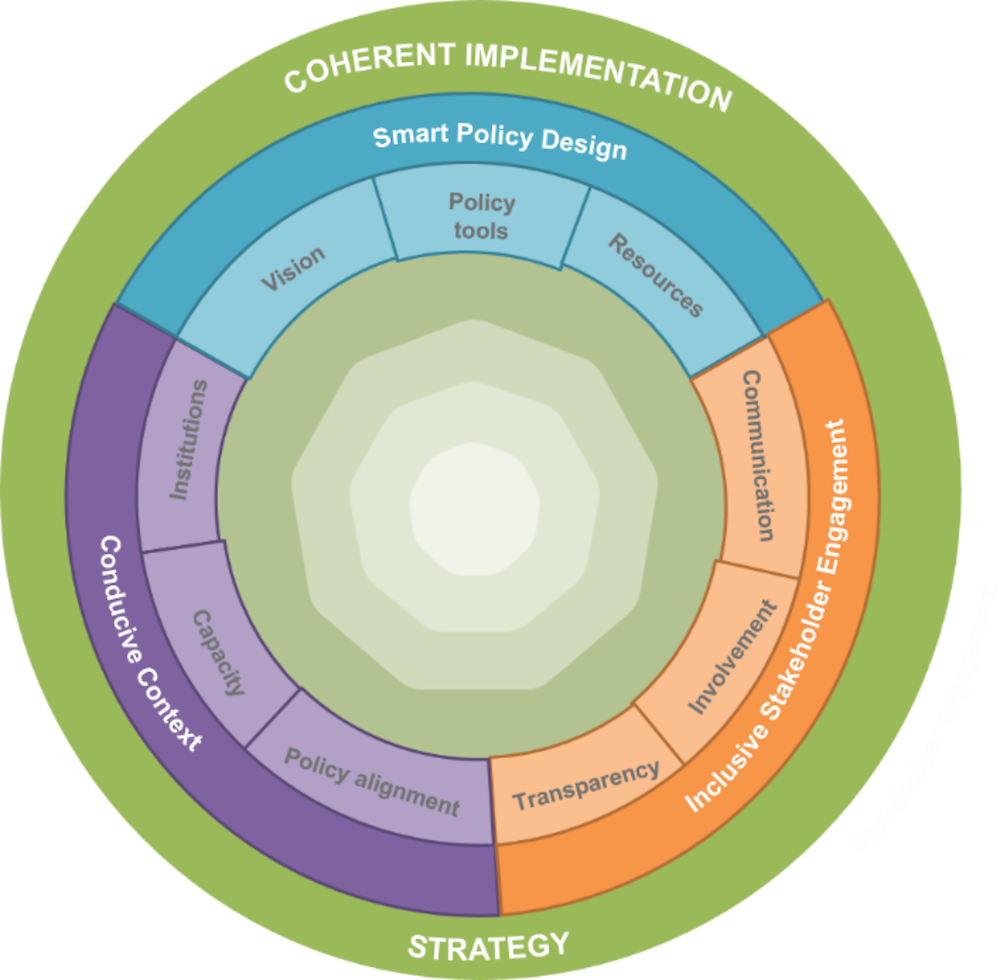

The OECD assessment focuses on CfE in the Broad General Education (BGE) and Senior Phase (upper‑secondary education). It uses the OECD Framework on Education Policy Implementation (Figure 1.1) to review how CfE has been implemented until 2020 and provides options to consider for next steps. The framework highlights that analysing the implementation of an education policy requires looking at the dimensions of policy design, stakeholder engagement, and policy context, and how they weave together to turn policy into reality (Viennet and Pont, 2017[1]; Gouëdard et al., 2020[2]).

Figure 1.1. The OECD Framework on Education Policy Implementation

Source: OECD, (2020[3]), An implementation framework for effective change in schools, https://doi.org/10.1787/4fd4113f-en.

To undertake this analysis, the OECD formed a team of OECD analysts and external experts of curriculum and assessment implementation (see Annex A), who are the authors of this report. The OECD team carried out a desk-based analysis of policy documents, evidence and research on CfE implementation. The sheer number of existing publications about CfE is a testament to the system’s commitment to continuous educational improvement. Key documents in the corpus included, but were not limited to:

A Building the Curriculum series and complementary policy documents developed at central and local levels.

A previous OECD review of the Scottish education system (OECD, 2015[4]).

Reports and evidence submitted to Scottish Parliament commissions.

Reports commissioned by the Scottish Government and CfE governance committees.

The initial evidence pack compiling information and case studies on key issues of CfE and its implementation. The Scottish Government produced the document with help from key stakeholders for the OECD assessment (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Published academic articles and ongoing research reports.

Position papers and studies carried out about CfE by major stakeholders in the system.

Against the rich backdrop of existing documentation of CfE and its implementation, the OECD team conducted a series of online group interviews and virtual school visits to gather primary data. The team undertook virtual policy and school visits, including interviews with key stakeholders from across the Scottish education system and with practitioners, learners and their parents to complement the evidence base.

The team met virtually with representatives of over 40 organisations, education researchers and stakeholder committees during the first week. Additional interviews with scholars were also conducted between October and November 2020. The second week of online visits was dedicated to visiting schools and meeting with additional practitioners, learners and their parents from across Scotland, resulting in discussions with stakeholders from 14 schools in total. School visits started with a review of their curriculum model before holding meetings with school leadership, teachers, parents and learners. The group interviews consisted of 75 minute long meetings with groups of four to eight practitioners, learners, and parents. A final stakeholder consultation event was held on line to discuss OECD preliminary findings on 16 March 2021. The detailed agenda for each mission week, additional scholar interviews and the final event can be found in Annex B.

All school visits and stakeholder interviews were conducted online due to the coronavirus (COVID‑19) crisis and travel restrictions, using secure online video-conferencing platforms and following the OECD’s policy on personal data protection. Although this setting prevented the collection of observational data in school classrooms, it allowed for qualitative group interviews with learners at various stages of education and with teachers and school leaders from schools located in ten different local authorities. The OECD team checked the evidence gathered from these interviews and virtual school visits for consistency against relevant research and findings from trusted sources when they already existed, which brought additional confirmation to this report’s findings.

Finally, the authors purposefully chose to analyse statistics and other quantitative data from years prior to 2020, to control for the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on Scotland’s education system since the focus of this report is on trends and processes that predate the pandemic. Unless the phenomenon analysed is directly linked to the crisis, the latest school year of reference used for data is 2018‑19.

This report presents the analysis and results of the OECD team analysis. It is structured as follows:

This chapter introduces the context of the assessment, provides an overview of the Scottish education system, its performance, policies and tensions, and provides a conclusion on issues to consider for CfE policy to adjust in the future. The following chapters then analyse the dimensions central to the implementation of CfE.

Chapter 2 analyses the design of CfE, current practices and considerations for CfE to be most effective for Scottish young people.

Chapter 3 analyses stakeholders’ engagement with CfE, how they have engaged as part of the implementation process, and how engagement could improve in the future.

Chapter 4 analyses the policy environment of CfE and how its contextual dimensions can contribute to, or hinder, progress with CfE.

Chapter 5 brings together the different dimensions to provide a coherent and actionable implementation perspective for the future of CfE.

The Scottish economic and social context

Scotland is a country of the United Kingdom, bordered to the south by England, to the east by the North Sea, and by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and north. Scotland has around 5.46 million people, including 1.03 million (19%) aged under 18. The Highlands, in the north and northwest of mainland Scotland, and the Borders, to the south, are sparsely populated, while the central belt accounts for the bulk of the population. Scotland also has a large number of islands, many off the west coast and with Orkney and Shetland to the north (OECD, 2015[4]). Scotland’s population is at a record high and has been growing steadily since the turn of the century. This has been driven mainly by net inward migration as opposed to births, and the population of children has declined slightly over this period (Scottish Government, 2021[5]). The ethnic minority population of Scotland has grown rapidly over the last decade, and diversity in Scottish schools is increasing as a result. Many languages such as Polish, Urdu and Punjabi are spoken in communities and schools alongside English, as well as the heritage languages of Gaelic and Scots.

The Scottish economy is structured as most advanced economies, with services accounting for most of its economic output (about 75% in 2016) and employment. Key sectors in Scotland include oil and gas; the food industry; energy, including a growing renewable energy sector; financial services; tourism; creative industries; and education. The Scottish economy was performing well before the COVID-19 crisis. Annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates remained positive, between 0.7% and 1.5% in 2016‑19, and unemployment was at historically low levels, at 3.5% in 2019 (Scottish Government, 2019[6]). By comparison, annual growth rates for the United Kingdom as a whole were slightly higher (between 1.2% and 2.2% in 2016‑19), while the overall unemployment rate remained slightly higher (3.8% in 2019), the country being affected by the uncertainty around Brexit negotiations.

The COVID-19 crisis provoked serious contractions to the Scottish economy, as in other economies, amounting to a 21.4% fall in GDP over the first half of 2020 (latest available data), in line with the 22.1% contraction in the United Kingdom’s economy overall. The impact on different economic sectors varied according to the extent of corresponding restrictions, but the fall in output was spread relatively evenly across sectors. By way of comparison, Scotland’s GDP fell around 4% over six quarters during the global financial crisis. The quarterly unemployment rate for May-July 2020 increased by 0.7% compared to the similar point the previous year (Scottish Government, 2020[7]). Around 19% (1 020 000 individuals) of the population of Scotland were in relative poverty in 2016‑19 (after housing costs). Over half of those in relative poverty were in poverty despite having at least one working adult in the household. This proportion increases for children, with almost a quarter (24%, around 230 000 children) (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

At the time of writing this report, two factors influenced the political context around Scotland’s education. First, parliamentary elections are planned for May 2021. As part of the United Kingdom, Scotland’s politics operate under the United Kingdom’s constitutional monarchy, through Scottish representation at the Parliament of the United Kingdom and within Scotland’s own legislative and executive institutions. Since the Scotland Act of 1998, the Scottish Parliament took full legislative responsibility for a range of devolved competencies, including education. The Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) are elected every five years, following which the leader of the party with majority support in Parliament is usually nominated candidate for First Minister and appointed by the Queen. The First Minister heads the Scottish Government, determines portfolios and appoints other ministers and cabinet secretaries with the approval of Parliament and the Queen. At the time of writing this report and before the Scottish elections planned for May 2021, the Scottish National Party (SNP) had been in power in Scotland since 2007 (including as a minority government since the 2016 Scottish elections) and had kept education as one of their top policy priorities during that time.

Second, the COVID-19 crisis. Like many countries, Scotland was hit by the COVID-19 crisis, which resulted in school closures, adaptations to the national qualification examination diets and other changes that could mark the education system for the long term. The COVID-19 pandemic was first declared to have spread in Scotland on 1 March 2020, after which schools closed on 20 March, along with several other sectors, and the 2020 national exam diet was cancelled. Scotland followed the rest of the United Kingdom into lockdown from 23 March until the end of May, when restrictions started easing. Education continued following a remote learning model until the summer, with a number of government initiatives aiming to guarantee that all students could have access to a computer and a reliable Internet connection. Schools opened again in August, with students allowed back into classrooms following safety protocols until the end of 2020. The analysis in this report focuses on CfE implementation before the COVID-19 crisis of 2020 but considers the opportunities created by key events of that year for future developments of CfE.

An overview of the Scottish education system

School education structure

The Scottish education system counts around 2 500 schools serving learners from four years old, with 96% in publicly funded local authority‐managed schools. Not all schools in Scotland offer early childhood education and care (ECEC, referred to as “early learning and childcare” in Scotland). As of May 2020, the publicly funded school system caters to 96 375 students in publicly funded ECEC; to 398 794 students in primary education; to 164 397 students in lower-secondary education; and 127 666 students in upper‑secondary education. The school system employs more than 49 000 teachers (Table 1.1). Operated by non-public entities, independent schools (about 100 in 2020) provide education for over 30 000 students. In 2019, 114 publicly funded schools for special education needs were also operating, serving 7 132 students, although the majority of the students with an additional support need recorded (more than 30% of all students) attend mainstream schools. The Scottish school system also includes Gaelic Medium Education (GME), which aims for young students to learn fluently in both Gaelic and English through primary and secondary education. There are 8 stand-alone GME primary schools (out of the 2 004 total primary schools), 52 primary schools with a GME and EME (English Medium Education) stream in the same school, and 32 secondary schools that offer GME subjects (out of 358 secondary schools in total).

Table 1.1. Number of students, schools and teachers by level of education in Scotland (United Kingdom), 2020

|

|

ECEC (Early learning and childcare), publicly funded |

Primary education |

Secondary education |

Independent schools |

Special schools |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

BGE1 |

Senior Phase |

|||

|

Number of students |

96 375 (September 2019) |

398 794 |

164 397 |

127 666 |

30 000 |

7 132 |

|

Number of schools (or ECEC centres) |

2 576 |

2 004 |

358 |

100 |

114 |

|

|

Number of teachers or qualified staff |

798 (September 2019) |

25 027 |

23 522 |

.. |

1 927 |

|

|

Student-teacher ratio |

.. |

15.9 |

12.4 |

.. |

3.7 |

|

|

Enrolment rates |

98% of eligible 3-4 year-olds |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

x |

|

Number of schools offering GME (either stand-alone or with EME) |

.. |

60 |

32 |

.. |

x |

|

1. BGE stands for Broad General Education, which encompasses early learning, primary and lower-secondary education levels.

.. = missing data; x = not applicable. All data are based on the latest published data as of May 2020.

Source: Scottish Government (2021[5]), Curriculum for Excellence 2020-2021 - OECD review: initial evidence pack, https://www.gov.scot/publications/oecd-independent-review-curriculum-excellence-2020-2021-initial-evidence-pack/ [accessed on 24 March 2021].

According to the Scottish Government’s classification of school locations, 31% of the students attending publicly funded schools went to a school in a large urban area, and 42% attend schools in smaller urban areas. The remaining 27% attend schools in accessible small towns (9%), remote small towns (5%), accessible rural areas (8%) and remote rural areas (4%) (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

The school system is organised in sequential levels summarised in Table 1.2. Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) caters for children aged 3 to 18 years, beyond the boundaries of compulsory education (ages 5‑16 in Scotland). ECEC is provided for those up to five years of age (International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED] 0), and while it is not compulsory, 98% of eligible children aged three and four are registered in 2020. Children aged three to four are entitled to 20 hours per week of unconditional free access to ECEC, which is fewer than most OECD countries (OECD, 2020[8]). At the time of drafting this report, the Scottish Government was phasing in an expansion that will almost double this hourly entitlement for early years, from 600 hours to 1 140 hours per year (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Primary education provides for children aged 5‑12 (ISCED 1) as the first part of what is commonly known as BGE (Broad General Education) under CfE. Starting at age five in Scotland, compulsory education starts earlier than in most OECD countries, where students are required to start primary education at the age of six or seven. The seven years of primary education place Scotland’s duration above OECD average, at the same length as in Australia, Denmark, Iceland and Norway (OECD, 2019[9]). Students usually complete primary education by age 11 or 12 (Table 1.2).

Secondary schools offer up to six years of education, similarly to the OECD average (OECD, 2019[9]). Lower-secondary education (ISCED 2) formally continues the BGE cycle with three years (S1 to S3). The following three years (S4 to S6) form the upper-secondary education cycle, known as the “Senior Phase” under CfE. Students typically prepare most of their qualifications during the Senior Phase, with S4 being the last year of compulsory education. Most learners continue studying beyond the compulsory age of 16 in upper-secondary education. In 2018/19, 11.9% of school leavers were in S4, 26.8% in S5, and 61.2% in S6 (Scottish Government, 2021[5]). Under Curriculum for Excellence, upper-secondary levels aim to offer a variety of educational pathways and lead to a broad range of qualifications to diversify students’ experience:

General upper-secondary education covers three years at ISCED 3 for ages 15 to 18. It is offered in secondary schools and is the stage aimed at preparing young people for moving to further education, higher education (ISCED 6‑8), training or into the workforce. Under CfE, schools can offer a wide variety of pathways to cater for learners’ career aspirations through the Senior Phase, which include an increasing number of vocational opportunities within general education, including modern apprenticeships, for instance, or additional courses taken in colleges.

Vocational educational pathways are also offered in colleges of further education (ISCED 3) with opportunities to continue on to professional studies and higher education (ISCED 5‑8).

Table 1.2. Structure of education provision in Scotland (United Kingdom)

|

Age (years) |

ISCED |

Education level |

Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2/3‑5 |

0 |

Early learning and childcare |

|

|

5‑12 |

1 |

Primary: Seven years, P1 to P7 (compulsory) |

Primary schools |

|

12‑15 |

2 |

Secondary: Three years, S1 to S3 (compulsory) |

Secondary schools: comprehensive and mostly co-educational |

|

15‑18 |

3 |

Upper-secondary: Three years, S4 (compulsory) and S5‑S6 (optional). Subjects studied at different levels for various qualifications including general and vocational |

Secondary schools, colleges of further education or independent training providers |

|

4 |

Further education (non-advanced courses: vocational and general studies, etc.) Higher education (advanced courses: Higher National Certificate, Higher National Diploma, etc.) |

Colleges |

|

|

17+ |

5 |

Higher education: Higher National Certificate, Higher National Diploma, professional training courses and postgraduate |

Higher education institutions (universities and colleges) |

Sources: OECD (2020[10]), “Diagram of the education system – United Kingdom”, https://gpseducation.oecd.org/Content/MapOfEducationSystem/GBR/GBR_2011_EN.pdf; European Commission (2020[11]), “United Kingdom – Scotland Overview”, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/united-kingdom-scotland_en [accessed on 22 March 2021].

There is no school-leaving certificate in Scotland. Students in upper-secondary education may take a number of qualifications and courses, including Scottish National Qualifications or Awards certificated by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA), Scotland's awarding body. Learners can enrol and pass a range of qualification subjects from National 1 to National 5, Higher, Advanced Higher courses, Skills for Work and Baccalaureate qualifications, and more (Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework, 2021[12]). These can be in areas such as English, Physics, Maths, Politics as well as in Technology, Creative Arts, Drama, Environmental Sciences or Food and Health, for example. Scottish National Qualifications – including National 2‑5, Higher and Advanced Higher – are single-subject qualifications that certify the achievement of a level of knowledge and skills in a range of subjects. They are referenced against the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF), which unifies all qualifications in Scotland and classifies them between its 12 levels (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Scotland has worked to promote and develop its vocational education since 2014, including strengthening partnerships between schools, colleges and employers to cater more efficiently to learners’ needs, linking with the economy's needs. Colleges offer vocationally oriented courses, with studies predominantly leading straight to employment within a specific industry. Regular qualification course levels include the Higher National Certificate (one year to complete) and Higher National Diploma (two years). Like the other qualifications, there is no specific age at which learners are supposed to take them. For students in the Senior Phase, schools work closely with colleges and often employers to increase the number of vocational opportunities available to learners and help them complete vocational courses alongside National Qualifications courses. Colleges also collaborate with local authorities and employers to deliver Modern Apprenticeships programmes for young people aged 16 or above who have left school and Foundation Apprenticeships for students still in full-time education. They also work in partnership with employers to prepare students for work and with universities to allow fast-track degree entry on some courses.

Scottish universities and colleges set their own entry requirements, often combining specific qualifications, subject, or grade, or a specific grade required in a subject relevant to the programmes applied for. Starting in 2020, courses at Scottish universities and colleges have two sets of requirements: standard and minimum. Minimum entry requirements apply for applicants who are considered to be “widening access” students, based on their merit, socio-economic background, school’s category as measured by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) and other criteria (UCAS, 2020[13]). Standard requirements can be stricter for competitive degrees, including requirements in terms of number of passes and minimum grades to obtain an SQA Highers and equivalent international qualifications.

Teachers and school leaders

In Scotland, all teachers need a graduate degree or equivalent, plus a teaching qualification to gain Qualified Teacher Status. Teaching qualifications include undergraduate degrees (Bachelor of Education, Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science; ISCED 6) and postgraduate qualifications (Professional Graduate Diploma in Education [PGDE]; ISCED 7). For all levels of education (pre-primary to upper-secondary), the minimum qualifications required for the Standard for Full Registration are a bachelor’s degree (ISCED 6) and a postgraduate teaching qualification (ISCED 7) or a bachelor’s degree in education (ISCED 6) (OECD, 2019[14]). The Standard for Provisional Registration (SPR) specifies what is expected of a student teacher at the end of initial teacher education seeking provisional registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS). Having gained the SPR, all provisionally registered teachers continue their professional learning journey by moving towards attaining the Standard for Full Registration (SFR). The SFR is the gateway to the profession and is the benchmark of teacher competence for all teachers (OECD, 2019[14]).

At lower-secondary level, teachers in Scotland spend 63% of their working time teaching, which is higher than the OECD average (43%). Scotland is among the only OECD education systems, along with countries such as Chile, Latvia and Spain, in which teachers spend at least 50% of their statutory working time teaching (OECD, 2019[9]). Regulations state that teachers at all levels of education have a working week of 35 hours, and they are expected to be in school 1 045 hours per year (OECD, 2019[14]). Five additional in-service days per year are reserved without class teaching. During their working time, teachers in most countries are required to perform various non-teaching tasks such as lesson planning/preparation, marking students’ work and communicating or co-operating with parents or guardians.

Scotland is one of few OECD education systems in which teachers are required to teach the same number of hours across levels of education. It is more common in OECD countries and economies to see teaching time decrease as the level of education increases. Teaching time has evolved in Scotland between 2000 and 2019: it dropped by 95 hours at pre-primary and primary levels, as part of a teachers’ agreement that introduced the 35-hour working week (A Teaching Profession for the 21st Century, 2001), resulting in a maximum of 22.5 hours of teaching per week for primary, secondary and special education teachers. Even with this decrease in net contact time, the maximum time that teachers at these levels can be required to teach is still longer than the OECD average (OECD, 2019[9]). Teachers are also expected to complete 35 hours of professional development per annum in Scotland. Professional development is excluded from statutory teaching time (OECD, 2019[14]).

In Scotland, guidelines on school leaders’ (known in Scotland as headteachers) working conditions do not detail their responsibilities and tasks. This is the case for about one-quarter of OECD countries with available information, including Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden. By comparison, regulations explicitly outline expectations for school leaders’ managerial and leadership roles in more than half of the OECD and partner countries with available data (OECD, 2020[8]). In 2018, the Scottish Government and local authorities agreed on a Headteachers’ Charter, committing local authorities to support school leaders as the drivers of school improvement and devolving greater responsibility to them in decision making and resource use.

Attainment

Among students leaving school education in Scotland in 2018/19, 95% entered a positive destination, according to the Government’s measures, the highest since 2009/10. Positive destinations include higher education, further education, employment, training, voluntary work and personal skills development, while other destinations include unemployed and seeking work, unemployed and not seeking work, and unknown. In general, after secondary education, learners mostly go on to higher education (40.3% in 2018/19), further education (27.3%) and into employment (22.9%). Out of the remaining 9.5%, half go to “other positive destinations” (4.5%) (Scottish Government, 2020[15]).

In addition, in 2019, Scotland’s Annual Participation Measure showed that 91.6% of 16‑19 year‑olds were participating, meaning they were in some form of education, employment or training and other personal development for most of the year. This ranged from 85.8% of young people in the most deprived areas to 96.3% in the least deprived areas. The gap (10.5 percentage points) has been narrowing over time as the proportion of young people from the most deprived areas who are participating has increased faster than has the proportion of young people from the least deprived areas (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).1

School leaver attainment statistics in Scotland are based on the range and level of National Qualifications a student has accumulated by the time he or she leaves school. Reporting is based on Scotland’s common qualifications framework, the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF). More than 60% of 2018/19 school leavers achieved one or more qualification passes at SCQF Level 6 or better (e.g. Higher); 85% had one or more passes at SCQF Level 5 or better (e.g. National 5); and 95.9% attained one or more passes at SCQF Level 4 or better (e.g. National 4).

These attainment statistics remained stable since 2014/15 and progressed since 2009/10 when 50.4% of school leavers achieved one or more passes at SCQF Level 6 or better; 77.1% had one or more passes at SCQF Level 5 or better; and 94.4% attained one or more passes at SCQF Level 4 or better. Attainment in terms of four and five passes at SCQF Level 6 also remained stable since 2014/15 and progressed since 2009/10.

The Scottish Government highlighted that recent changes to SCQF qualifications, including creating new vocationally oriented courses and changes to national courses, mean that comparison in attainment rates with years over a long period is complex and could be erroneous (Scottish Government, 2021[5]). In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the cancellation of National 5, Higher, and Advanced Higher exams and to the decision by the SQA not to collect nor mark coursework. Grades in these qualifications in 2020 were instead based on teacher estimates. The authors purposefully chose to analyse data from years before 2020 to control for the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on Scotland’s education system.

Student performance

15-year-olds’ levels in reading, mathematics and science

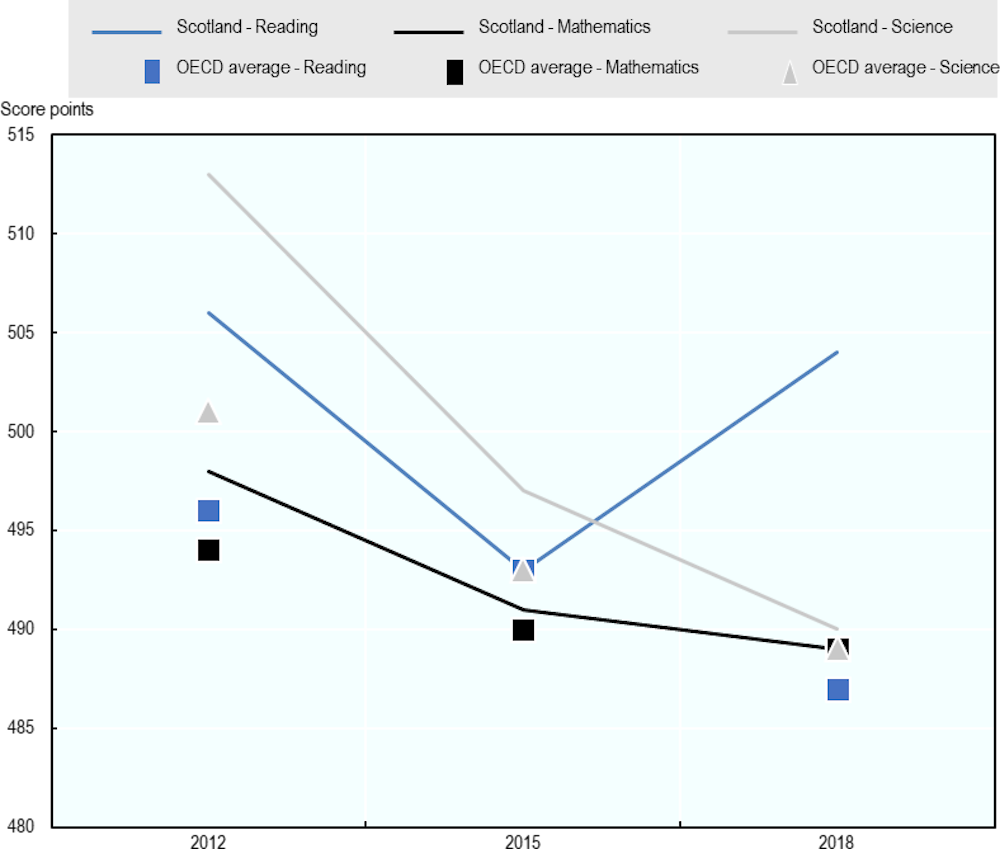

Scotland has ranked among higher-than-average country performers on international assessments such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), usually scoring at or above OECD average in mathematics, reading and science. Scotland’s average scores declined between 2009 and 2018, similarly to average OECD performance, and improved in reading and remained stable in mathematics and science between 2015 and 2018 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Average performance in reading, mathematics and science in Scotland (United Kingdom) and the OECD average, PISA 2012-18

Note: The data for this figure was collected before Costa Rica became an OECD member. In 2015 changes were made to the test design, administration, and scaling of PISA. These changes add statistical uncertainty to trend comparisons that should be taken into account when comparing 2015 results to those from prior years. Please see the Reader’s Guide and Annex A5 of PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education (OECD, 2016) for a detailed discussion of these changes.

Sources: OECD (2019[16]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en; OECD (2019[17]), “Results for regions within countries”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/bad603f0-en.

In 2018, Scotland’s average score on the PISA test in reading was 504 score points, representing an 11 score-point improvement on its 2015 score, almost on par with its 2012 performance, and higher performance than the OECD average. In mathematics, Scotland performed at OECD average with 489 score points, similar to its 2015 scores but lower than 2012. In science, Scotland scored at OECD average (490 score points), with similar scores to 2015 and declining since 2012 (OECD, 2019[17]; OECD, 2019[16]). Scotland’s performance on PISA 2018 relative to OECD countries and economies improved in reading (only 5 OECD countries and economies outperformed Scotland, compared to 13 in 2015); it stayed similar in science (outperformed by 13 OECD countries and economies); and declined in mathematics (outperformed by 18 OECD countries and economies, compared to 14 in 2015) (Scottish Government, 2019[18]; Scottish Government, 2016[19]).

In 2018, Scotland’s proportion of top performers in reading (10.3%) was higher than in 2015 and higher than the OECD average (8.7%), while the proportion of low performers (15.5%) was similar to 2015 and smaller than the OECD average (22.6%). Scotland’s proportions of top performers were slightly higher than the OECD average in science and close to average in mathematics (slightly over 10%), both similar to the respective proportions in 2015. The proportions of low performers were close to OECD averages in mathematics (23.5%) and science (21.1%), and also similar to the respective proportions in 2015 (OECD, 2019[16]).

Students’ progress in the system is assessed as part of ongoing learning and teaching, both periodically and at key transitions, with the first formal assessment for qualifications, including examinations taken around the age of 15 and at the end of the Senior Phase. BGE has five levels of progression (early, first, second, third and fourth) that approximately correspond to system levels of pre-school to lower-secondary education. Achievement of a level is based on teachers’ overall professional judgement and informed by a range of evidence, against the benchmarks defined for each curriculum level. The Senior Phase represents the sixth level of progression in CfE. Based on the annual assessment of achievement of CfE levels, 72% of P1, P4 and P7 learners (combined) achieved expected levels in literacy and 79% in numeracy. In secondary education, 88% of S3 learners achieved the expected level in literacy and 90% in numeracy (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

15-year-olds’ levels in global competences

PISA’s new global competence module aims to capture the capacity of 15‑year‑olds to examine local, global and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others, to engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development.

Scotland ranked among the top-performing countries in global competence. It scored higher (with a mean score of 534) than its expected outcomes based on its average results in reading, mathematics and science. Scotland was the fourth top-performing country, behind Singapore, Canada, and Hong Kong (China), with mean performance scores more than 50 points above the overall average (of 474 points). While differences in average performance across countries and economies were large, the gap between the highest performing and lowest performing students within each country was even larger. Scotland was among the countries and economies whose variations in performance scores between students were the largest, along with Canada, Israel, Malta, and Singapore, exceeding 100 score points, compared to an average of 91 points (OECD, 2020[20]).

Scotland was the third country with the largest proportion of students who scored at Level 5 (12%), behind Singapore (22%) and Canada (15%). This is significantly higher than the average of 4% of students. At Level 5, the highest level of proficiency in global competence, students can analyse and understand multiple perspectives. They can examine and evaluate large amounts of information without much support provided in the unit’s scenario. Students can effectively explain situations that require complex thinking and extrapolation and can build models of the situation described in the stimulus (OECD, 2020[20]).

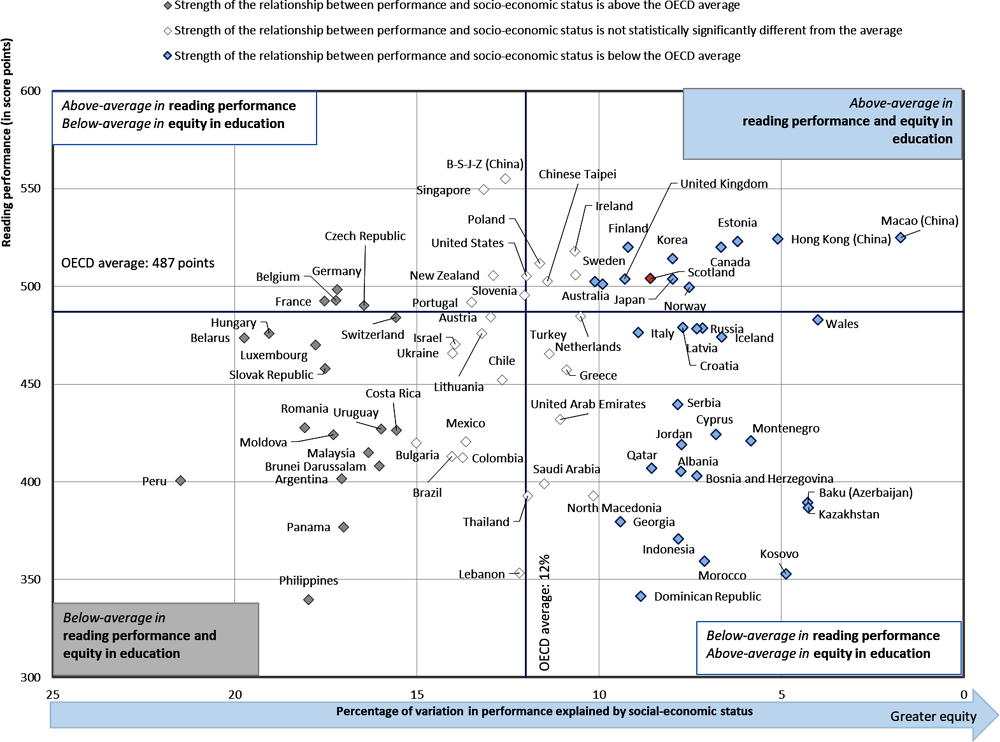

Equity

Students’ socio-economic status has a relatively small impact on their performance in Scotland, compared to other OECD countries and economies. The extent of socio-economic disparities in academic performance indicates whether an education system helps promote equality of opportunities. Figure 1.3 shows that in Scotland, students’ socio-economic status had relatively little impact on their reading performance than other OECD countries. In 2018, the socio-economic status as measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS) explained only 8.6% of the difference in performance between students from the most and least advantaged backgrounds in Scotland. This means students’ socio-economic status had a smaller impact on their performance in Scotland than on average across the OECD, where the ESCS explained 12% of the difference in performance. The impact of students’ socio‑economic status on their PISA performance in maths and science was also smaller in Scotland than on average in the OECD area, explaining 7.9% of the performance difference in maths, compared to 13.8% on average, and 10.1% of the performance difference in science compared to 12.8% on average (OECD, 2019[21]; OECD, 2020[22]).

Figure 1.3. Equity and reading performance, PISA 2018

Note: The data for this figure was collected before Costa Rica became an OECD member. B-S-J-Z (China) stands for Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang (China).

Source: OECD (2019[16]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en; OECD (2019[17]), “Results for regions within countries”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/bad603f0-en.

In 2018, the proportion of disadvantaged students who were academically resilient was higher in Scotland (13.9%) than on average across OECD countries and economies (11.3%). This marks the overall progress made on academic resilience since 2012, both in Scotland and on average. The difference in performance is significant (32 score points) between students at the top and bottom quarters of socio-economic status in Scotland, although still below the OECD average (37 score points) (OECD, 2019[21]).

PISA 2018 data suggest that the variation around Scotland’s mean reading score is largely explained by factors other than school characteristics. The average score-point variation in reading performance is largely due to within-school variation (84.8%, above the OECD average of 71%). Only a very small percentage is explained by between-school variations (8.1%, compared to 29% on average) (OECD, 2019[21]).

On PISA’s global competence module, the difference between advantaged and disadvantaged students’ scores in global competence was larger than 80 score points in Scotland but was not significant after taking into account students’ performance in reading, mathematics and science. The findings show that advantaged students (those in the top quarter of the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status) have access to more learning opportunities than disadvantaged students in Scotland, as is the case in 31 of 64 participating countries and economies.

At the system level, Scotland uses three indicators to measure the attainment gap between the proportion of school students from the most and least deprived areas of Scotland:

At SCQF Level 4 or better, 98.8% of students from the least deprived areas attained one pass or more in 2018/19. This compared to 92.1% among those from the most deprived areas. The attainment gap was therefore 6.7 percentage points, up from 6.1 percentage points in 2017/18 and down from 11.3 percentage points in 2009/10 (the first year for which comparable statistics are available).

At SCQF Level 5 or better, 94.6% of students from the least deprived areas attained one pass or more in 2018/19. This compared to 74.4% among those from the most deprived areas. The attainment gap was therefore 20.2 percentage points, down very slightly from 20.3 percentage points in 2017/18, with attainment having decreased among students from both the most deprived and least deprived areas. The attainment gap in 2009/10 was 33.3 percentage points.

At SCQF Level 6 or better, 79.3% of students from the least deprived areas attained one pass or more in 2018/19. This compared to 43.5% among those from the most deprived areas. The attainment gap was therefore 35.8 percentage points, down from 37.4 percentage points in 2017/18, with attainment having decreased among students from both the most deprived and least deprived areas. The attainment gap in 2009/10 was 45.6 percentage points.

Interestingly, learners in Scotland living in accessible rural areas are the most likely overall to achieve SCQF Level 6 or better (62.8%), while learners in remote rural areas are the most likely to achieve at SCQF Level 5 or better (87.9%) in 2018/19, compared with other areas. The least likely to achieve those levels are learners in remote small towns and urban areas classified as “other than large” (Scottish Government, 2020[15]).

School environment, health and well-being

Improving children and young people’s health and well-being is one of the Scottish Government’s key priorities. Students report more often being exposed to bullying in Scotland than on average across OECD countries and economies (index of 0.23 for a basis 0 on average). A larger share of students are bullied frequently (11.4% compared to 7.8%). The disciplinary climate in regular classes is similar in Scotland to the average climate across OECD countries and economies (index of 0.07). The large majority of students declare that situations that are unconducive to learning occur “never or hardly ever” or “in some lessons” only, including when students do not listen, when there is noise, or when students or teachers need to wait before class starts (OECD, 2019[23]; OECD, 2020[24]).

Competition between students seems to be slightly more common in Scotland than co-operation. In 2018, some 73% of students reported that it seemed “very” or “extremely true” to them that students were competing against each other, whereas only 61% said they observed co-operation among students. Students in Scotland also reported that their schoolmates seemed to value competition more than co‑operation (OECD, 2020[24]). This was in opposition with the attitude across OECD countries and economies, where competition between students was on average less observed (50%) than co-operation (62%) (OECD, 2019[23]).

Students in Scotland report slightly lower life satisfaction than the OECD average and more prevalent fear of failure than average. The sense of belonging to one’s school is slightly less strong in Scotland than on average across OECD countries and economies (OECD, 2020[24]). On a final note, students in Scotland display a growth mindset more often than on average across OECD countries and economies (OECD, 2019[23]).

Governance and funding

Scotland has a long tradition of organising its own education system and wields full legislative power and executive authority in all areas of education since the Scotland Act of 1998. In the current government, the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills is also the Deputy First Minister and has overall responsibility for Scottish education, in collaboration with supporting ministers sharing responsibilities in specific areas, and with support from relevant administrations, including the Learning Directorate. The Scottish Government, via the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, sets broad policy for all aspects of education in Scotland. Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) is the framework for curriculum policy set at the central level, upon which schools and practitioners build their own curriculum, adapted to the needs of their learners and their local context.

The Learning Directorate works with statutory agencies to implement policies, including Education Scotland (responsible for educational improvement and inspection), the Scottish Qualifications Authority, Skills Development Scotland (SDS) and the Scottish Funding Council (funding teaching and research in higher and further education). Since it was established in 2011, Education Scotland inherited the full range of functions to support educational quality and improvement, including the inspection and review functions formerly held by the independent Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education (HMIE). Education Scotland’s Chief Executive Officer also fulfils the responsibilities of Chief Inspector of Education with a view to linking quality assurance with educational improvement support. A dedicated strategic director has specific responsibility for inspection standards.

Her Majesty’s (HM) Inspectors of Education perform inspections and reviews all sectors of Scottish education to provide quality assurance of learning and educational standards, gather evidence to inform HMIE advice to ministers, and build capacity through the system by collaborating and sharing practices with practitioners. Schools perform self-evaluations based on Education Scotland’s guidance, with support from their local authority, which inform external school inspections performed on a sample of about 240 schools every year. Individual inspection reports and summaries of inspection findings are published on Education Scotland’s website along with recommendations for support, if needed, by the school’s local authority.

Responsibility for organising, operating and staffing the school system within the Scottish Government’s policy guidelines is decentralised. The 32 local authorities, run by councils elected every four years, deliver a wide array of services, including schools, housing and social work, and are committed to pursuing national educational objectives. The local authorities have direct responsibility for schools, hiring school staff, providing and financing most educational services and implementing Scottish Government policies in education. Local authorities help schools design and implement their curriculum based on the CfE framework.

In 2017, Scotland introduced a new layer of educational governance by establishing six Regional Improvement Collaboratives (RICs) across the country to bring local authorities together alongside the central administration, and collaborate more effectively for greater equity and quality in education. Each RIC provides an annual regional plan and work programme aligned to the National Improvement Framework (NIF). They are led by a regional improvement lead, appointed by a joint steering group made up of officials from both the Scottish Government and local authorities. The regional improvement lead is to be formally managed by the chief executive of the employing local authority while reporting to all collaborating local authorities and the HM Chief Inspector and Chief Executive of Education Scotland. This followed an OECD recommendation made in 2015 to “strengthen the professional leadership of CfE and the ‘middle’”. The recommendation invited Scotland to shift the system’s centre of gravity towards schools and their local communities, including by fostering mutual support and learning across local authorities and networks of schools, and giving them a more prominent role as part of a “reinforced middle” (OECD, 2015[4]).

Local authorities fund schools via local funding, except for specific funding of national programmes such as the pupil equity funding. Since 2007, education funding has been rolled into the local government settlement, leaving local authorities to prioritise funding and allocate budgets. The Scottish Government provides 70% of all local government revenue, while the remaining 30% are business rates and council tax levied on residents. In terms of gross revenue expenditure across pre-school, primary, secondary, special school and non-school funding in 2018/19, GBP 5.5 billion was spent in total on all education levels in Scotland, an increase of 4.9% in real terms since 2013/14. The Scottish Government allocates specific resources, including for CfE-related spending (GBP 12.3 million in 2019/20). Local authorities devolve the management of some expenditures to the school level, leaving school leaders to make decisions about the use of at least 80% of school-based funding. Devolved School Management Guidelines were revised in 2012 to empower school leaders to meet local needs and deliver the best possible outcomes for young learners, in line with several Scottish policy objectives of CfE, Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) and the Early Years Framework (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Schools are responsible for the quality of education they offer to their students and are accountable to their local authority, including publishing annual improvement plans based on objectives set with their local authority. Schools’ responsibility to ensure the quality of education and their ability to design their own curricula to meet learners’ needs increased with the implementation of education policies such as CfE and the Empowerment Agenda in Scotland. Based on the national CfE framework, individual schools develop their own “curriculum rationale”, which forms the basis of a school’s approach to addressing learning needs. Rationales are expected to be developed with staff, parents, carers, local partners and youth in the school community.

Education policies

Curriculum for Excellence

Curriculum for Excellence, introduced for its first phase of implementation in schools in 2010, caters for children aged 3 to 18 years, with what is commonly known in Scotland as Broad General Education (early learning, primary and lower-secondary levels) followed by the Senior Phase (three years of upper‑secondary education). The philosophy of CfE is that of a future-oriented education, aiming to help students develop into successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors (referred to as the “four capacities”).

CfE defines curriculum as all the learning planned for children and young people from early learning and childcare, through school and beyond. Learning aims to be holistic and centred on the learner, and students are expected to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes inherent to the four capacities. The CfE framework encompasses four contexts for learning: eight curriculum areas, interdisciplinary learning, ethos and life of the school, and opportunities for personal achievements. CfE enables school communities to design their curriculum, and teachers are encouraged to teach in the way they esteem best suited to their students’ needs. The conception of teacher as curriculum developer was relatively new when first implemented in Scottish schools. Schools and local authorities were encouraged from the beginning to innovate and find local approaches to planning and delivering the curriculum within the framework provided centrally.

Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence was a ground-breaking curriculum policy when it first took shape in the early 2000s. In 2000, the Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc. Act 2000 set the principles that education should be directed to the development of children’s and young persons’ personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential, and that youth’s views should be taken into account in decisions that significantly affect them. A national debate (2002) concluded that one educational priority was to align curriculum to these aspirations, and the first statement of intent for a new Curriculum for Excellence was subsequently published in 2004.

CfE was further shaped over several years: a Building the Curriculum series developed the parameters of CfE in collaboration with national and local partners until 2010. Changes to the national regime of qualifications and discussions around student assessment later aimed to align assessment and examination approaches with CfE, along with a number of additional policies developed subsequently. Scotland spent almost a decade preparing its implementation by schools in 2010, when it was mainstreamed across the country.

In 2015, an OECD review of Scotland’s Broad General Education concluded that CfE was a “watershed” moment for education in Scotland, widely supported and exemplified in some schools’ inspiring curriculum experience, but that it required ongoing efforts to turn it into a reality for all students in the system. At the time, the OECD review acknowledged that the foundations of CfE had been set, including curriculum building blocks, assessments and qualifications, and adjustments to teacher education, leadership and the support structure. The consensus around CfE was deeply rooted, and the teaching profession was progressively taking ownership. Challenges remained, however, including a lack of clarity in the nature of CfE (was it a curriculum or a reform package?) and a risk of adopting a “wait and see” approach that would hinder CfE and its development in schools. The review proposed a number of detailed recommendations. Those directly linked to CfE are summarised here (the detail can be found in the full report) (OECD, 2015[4]):

To ensure equity and quality, develop metrics that do justice to the full range of CfE capacities informing a bold understanding of quality and equity.

To strengthen decision making and governance, 1) create a new narrative for Curriculum for Excellence; 2) strengthen the professional leadership of CfE and the “middle”; and 3) simplify and clarify core guidance, including in the definitions of what constitutes Curriculum for Excellence.

To enhance schooling, teaching and leadership, focus on the quality of implementation of CfE in schools and communities and make this an evaluation priority.

To improve assessment and evaluation, strike a more even balance between the formative focus of assessment and developing a robust evidence base on learning outcomes and progression.

The Scottish Government received these recommendations and used them as input into further policy development of CfE. The main actions taken as a result are summarised below and are analysed to a larger extent in Chapters 2‑5 of this report:

The guidance framework for the BGE curriculum was updated (including the development of CfE Benchmarks and publication of a Statement for Practitioners in 2016), and a “refreshed curriculum narrative” was published in 2019 as a response to the call for a new CfE narrative and simplified guidance.

National oversight and management arrangements for the curriculum framework were adjusted in 2018/19 in an attempt for more collaborative and systemic implementation.

The quality and equity of CfE implementation in schools were made the focus of sampled inspection, and a number of tools, action plans and strategies were developed to enhance CfE implementation and to increase engagement in secondary schools.

The Scottish Attainment Challenge was developed in 2015, and the National Improvement Framework in 2016 to promote and monitor equity and quality across the education system.

Additional policy developments that go beyond the scope of CfE, but affect its environment, are reviewed in the following sections. This new OECD review provides the opportunity for an external assessment of progress in terms of its implementation in both BGE and the Senior Phase, in light of current experience and international evidence to adapt and update it for the future.

Main education policies and priorities around Curriculum for Excellence

Getting it right for every child

Getting it right for every child was introduced in 2006. It provides a framework for all professionals working with children and youth to enforce children’s rights and guarantee children’s well-being holistically and across services. The Scottish Government decided in 2019 that the best way to promote and embed GIRFEC further was in partnership with local delivery partners, through practical help, guidance and support, and not on a statutory basis. The Scottish Government is therefore refreshing GIRFEC policy with those partners and developing new practice guidance on the key components of GIRFEC. Along with CfE and Developing the Young Workforce: Scotland’s Youth Employment Strategy (DYW), GIRFEC is a pillar of Scotland’s commitment to inclusive education. GIRFEC policy has been undergoing revisions since 2019 (new guidance) to allow for more partnership work between local delivery partners and the Scottish Government.

Early childhood care and education

Realising the Ambition: Being Me was published in February 2020 as an update to national practice guidance for the ECEC sector (Building the Ambition, 2014 and Pre-birth to Three, 2010). The policy reflects CfE curriculum guidance for ECEC based on national and international research in early childhood. It provides pedagogy and practice guidance for practitioners working with young children, also in alignment with other policies (e.g. GIRFEC) (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Scottish Attainment Challenge

As part of the SNP’s programme for government in 2016, the First Minister set her government the mission “to close the poverty-related attainment gap between children and young people from the least and most disadvantaged communities.” The Scottish Attainment Challenge was developed to this end in 2015, with GBP 750 million over five years to support schools and local authorities in improving literacy, numeracy and health and well-being in a way that would “close the gap”. Following implementation of the Scottish Attainment Challenge, the Scottish Government provided some evidence of impact from several performance and evaluation reports published in 2019 (Scottish Government, 2021[5]):

The gaps between school leavers from the most deprived and least deprived areas achieving one pass or more at SCQF Levels 3 or better, 4 or better, 5 or better and 6 or better have reduced between 2009/10 and 2017/18.

Attainment among the most disadvantaged children and young people rose in numeracy at all stages and in reading and writing at P1, P4 and P7. The attainment gap between the most and least disadvantaged has narrowed on most indicators.

Some 88% of headteachers reported improvements in closing the poverty-related attainment gap due to interventions supported by the Attainment Scotland Fund, and 95% expect to see improvements over the next five years.

Developing the Young Workforce: Scotland’s Youth Employment Strategy

In 2014, Developing the Young Workforce: Scotland’s Youth Employment Strategy set out to reduce youth unemployment levels by 40% by 2021. The strategy aims to create a work-relevant, school-based curriculum offer for young people in Scotland, informed by the needs of current and anticipated job markets. This includes embedding career education for children aged 3 to 18 years, offering formal careers advice at an earlier point in school, embedding employer engagement in education, creating new work-based learning offers and widening learner pathway options for young people in their Senior Phase. New learner pathway options include a wider apprenticeship offer for young people with Foundation Apprenticeships (SCQF Level 6) and Graduate Level Apprenticeships in place and Levels 4 and 5 in development. Implementation of DYW required schools to include the strategy as part of their curriculum development, thus creating direct links with CfE (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Teacher policies

A review of teacher education published in 2010 (Donaldson, 2010[25]) concluded that the two most important and achievable ways in which school education can realise the high aspirations Scotland has for its young people are supporting and strengthening the quality of teaching and leadership. The publication, Teaching Scotland's Future, highlighted the importance of sustained teacher professional learning and development in improving outcomes for young people. It also emphasised the importance of career pathways in supporting teacher recruitment and retention. The review led to wider recognition of the importance of quality professional learning and good educational leadership while providing a basis for professional update. It also reinforced the place of masters studies for teachers, increasingly common at all levels of the profession. A wide range of new forms of initial teacher education programmes also appeared in Scotland towards the end of the decade, aimed at helping to address recruitment challenges for teachers in priority subjects and the remote and rural areas of Scotland. Work to develop teacher career pathway models was conducted from 2017 to 2020. It was delayed by the COVID-19 crisis and implementation originally scheduled for August 2021 might also be delayed (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

Leadership

The Scottish Government has prioritised developing teacher and school leadership in recent years, including developing a broader offer of professional learning and the new requirement for school leaders to hold the Standard for Headship, a new qualification. The mission to clarify and bring coherence to educational leadership in Scotland, previously held by the Scottish College for Education Leadership, was transferred to Education Scotland and its Professional Learning and Leadership Directorate in 2018. Education Scotland started an evaluation process to inform developments of the professional learning offer and committed to collaborating with Regional Improvement Collaboratives, local authorities and the Learning Directorate in this endeavour (Scottish Government, 2021[5]).

New national courses and revised national qualifications

The Scottish Qualifications Authority, in collaboration with stakeholders, designed new national qualifications in the attempt to align them with CfE and to support learners’ achievement in developing the four capacities and the skills for learning, life and work that underpin them. The new national courses and qualifications aim to provide high standards and a formal acknowledgement of learners’ achievements while ensuring at the same time continuity with the breadth and depth of learning sought at earlier levels of CfE. The new national courses were first introduced in 2013/14, then revised and implemented as the revised national qualifications between 2016 and 2019, following concerns that the new structure and practice of national courses resulted in an overload of assessment (Scottish Qualifications Authority, 2021[26]; Scottish Government, 2021[5]). The number of qualifications registered in the SCQF beyond those awarded by the SQA also grew due to the Scottish Government’s promotion of the diversification of possible pathways and qualifications for learners.

SQA qualifications at SCQF Level 5 include the National 5 Award, Skills for Work National 5, the National Certificate and the National Progression Award. Level 6 qualifications include the SQA’s national courses at Higher level, as well as Skills for Work Higher and other Awards and Certificates. At SCQF Level 7, SQA qualifications include Advanced Higher, the Scottish Baccalaureate, as well as Awards, Higher National and Advanced Certificates.

In broad terms, Higher qualifications are considered the Scottish equivalent to English A-Levels, but they are not identical. Some notable differences are that Scottish Highers are one-year courses, whereas A‑Levels take two years to complete; students in Scotland get a smaller range of subjects to choose from at Higher and Advanced Higher levels than in England for A-Levels; and students tend to take more Highers in Scotland than A-Levels in England if they plan to apply for higher education, and they have the option of taking Advanced Highers. The number of University and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) points awarded by each grade also differ between the two types of qualifications, the A-Levels’ grades A* and A corresponding to Scottish Advanced Higher Grades A and B, respectively (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3. Number of UCAS points awarded by qualifications, Scotland and England (United Kingdom)

|

|

Scottish Higher |

Scottish Advanced Higher |

English A-Levels |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Grade A* |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

56 points |

|

Grade A |

33 points |

56 points |

48 points |

|

Grade B |

27 points |

48 points |

40 points |

|

Grade C |

21 points |

40 points |

32 points |

|

Grade D |

15 points |

32 points |

24 points |

Source: UCAS (2021[27]), “Calculate your UCAS tariff points”, https://www.ucas.com/ucas/tariff-calculator [accessed on 27 April 2021].

The National Improvement Framework

The National Improvement Framework was developed in 2016 with the ambition to “make Scotland ‘the best place to grow up and learn’” and to complement the existing pillars of the Scottish education system: CfE, GIRFEC and DYW. The NIF aims to structure a system and collaborative approach to educational improvement to pursue two key targets: achieving excellence through raising attainment and achieving equity by ensuring that all children have the same opportunity to succeed. The NIF sets out a holistic view of the education system, bringing together evidence and information from all levels and on all aspects that impact performance.

A new national data collection system provides additional information at the school, local and national level about children’s progress in literacy and numeracy, based on teachers’ assessment of progress. To support teachers in making judgements, the Scottish Government has introduced benchmarks for greater clarity on national standards as well as expanding opportunities for professional dialogue around standards through the Regional Improvement Collaboratives.

In 2019, local authorities reported that teachers feel increasingly confident when assessing progress. From 2018, Scottish National Standardised Assessments provide an additional source of objective, nationally consistent evidence. These assessments occur in primary school (ages 5, 8 and 11) and lower‑secondary (age 14). Since 2016, attainment in the Achievement of Curriculum for Excellence levels has been published annually to provide key data regarding children’s literacy and numeracy progress (OECD, 2019[28]).

Tensions around Curriculum for Excellence that impact student learning

This OECD assessment aims primarily to understand how CfE is implemented in BGE and the Senior Phase and to what extent it contributes to an education of quality for all young people in Scotland. As the scope of the assessment was agreed upon, a number of issues cutting across the Scottish education system were raised by the Scottish Parliament and Government, as well as by the OECD team. These issues arise from the need to find a balance between many parameters in Scotland’s complex education system and have implications for how CfE is implemented in the current policy context. The issues are reviewed below as part of the broader context and provide a useful backdrop for the analysis presented in the following chapters:

Tensions found between local curriculum flexibility and the need for coherence to achieve system-wide objectives: By design, CfE enshrines the principle of local curriculum flexibility since it gives schools the autonomy to design their own curriculum to best respond to students’ needs. CfE committed to school empowerment in a system already characterised by strong policy leadership from the centre and assertive local governments. At the same time, concerns arise in the public debate about whether the variability that inevitably characterises schools’ curricula effectively provides an excellent education for all learners or if it might increase educational inequalities. This also touches upon the issue of what level and kind of support schools might need to design curricula of high quality while respecting teachers’ and school leaders’ working time.

Tensions in the understandings of breadth and depth of learning: Opposed in the public debate, breadth and depth of learning seem not to have the same definition for the various stakeholders. Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD team tended to reflect this tension in the opposition between Broad General Education and Senior Phase, but the lack of clarity around the concepts poses many questions. For instance: does breadth refer to the number of subjects taken by students, and depth to the time allocated to each; or do they both refer to specific pedagogical approaches; are they exclusive or can they be complementary, and many more.

Tensions in the conceptualisation of knowledge, skills and competencies: Although CfE was developed to promote the acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitudes, the public debate as observed by the OECD team in Scotland throughout discussions tends to oppose knowledge and skills. Some also observed that while BGE was focused on the combination, the Senior Phase may still be focused on disciplinary knowledge (defined as subject-specific concepts and detailed content (OECD, 2019[29])). The OECD’s Future of Education and Skills 2030 project describes the integration of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values (integrations referred to as “competencies”) that enables students to perform in ill-defined environments, thus allowing them to navigate a fast‑paced and uncertain world. The definition of competencies as integrative and with a broad performance orientation allows the debate to shift away from the traditional “knowledge versus skills” focus by acknowledging the importance of both in learning.

Tensions between curriculum, student assessment and evaluation: There is an apparent (mis)alignment between curriculum, assessment and evaluation policies, especially at the Senior Phase. This tension was raised throughout the meetings of the OECD team in Scotland as one of the key issues that needs to be reviewed for CfE to perform at its best. These policies have complex relationships across numerous education systems, requiring alignment in their design as well as their implementation (OECD, 2013[30]; Gouëdard et al., 2020[2]; OECD, 2020[31]).

Some of these tensions likely arose throughout the development and the ten years of implementing CfE due to a combination of the ambition of the policy and the principle of flexibility embedded in CfE. Yet, some of these are inherent in the design of CfE itself, as it allows for flexibility in the interpretation of the principles and actions to make CfE happen on the ground across Scotland.

These tensions may affect the learning experiences of students across the country. They may vary in terms of the curriculum, as teachers have great freedom and may be overloaded in terms of course choices in some places with much less offer in other regions. When learners move up to Senior Phase, they have different types of assessments in relation to the type of learning they are experiencing in Broad General Education. Finally, students may have challenges finding the right balance in developing their knowledge and broader competencies. To resolve these tensions, it is necessary for Scotland to pinpoint where it wants to be on each of these, for CfE to reach its full potential and allow Scottish education to offer an education of excellence to all its learners.

Conclusion

The variable progress made in different education outcomes indicators, ten years of experience with CfE in schools, and the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the society, economy and education provide a good opportunity to review how CfE was implemented and what can be done for it to continue to deliver quality learning for all students across Scotland. Education system performance in Scotland presents a variable picture: while PISA results had declined between 2009 and 2015 (following the OECD average), they improved in reading and remained stable in mathematics and science between 2015 and 2018. At the same time, Scottish students have been among the top performers in global competences, which measure their capacity to interpret worldviews, to engage effectively in interactions with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development. In addition, there has been an increase to 95% in the positive destinations of those leaving schools in 2019 (considered in Scotland in relation to higher and further education, employment and other positive destinations).

In terms of equity, there has been an apparent improvement for disadvantaged students. According to PISA, the impact of students’ socio-economic status on their performance in reading, maths and science is among the lowest across OECD countries. At the same time, there is a higher proportion of resilient students (students from disadvantaged backgrounds who perform at high levels). Scottish data show an improvement in the performance of disadvantaged students in SCQF Levels 4, 5 and 6, with lower performance for those living in small towns in relation to rural areas.

Student well-being at age 15 shows a mixed picture, with higher levels than OECD average in bullying, in competition and in anxiety, and lower student well-being. At the same time, students report they experience a higher-than-average growth mindset. It is important to note that students at age 16 take their national exams, which are high stakes in terms of their next educational steps.

To achieve these outcomes, the system is organised around a mostly public provision of education for 3 to 18 year‑olds. Education beyond lower-secondary levels offers a range of choice for students, both in schools, colleges of further education and other educational settings, which can be combined. Teachers appear high quality in terms of requirements for entry into the profession and availability of support and professional development. School leaders have new supports in place to exercise their roles.

Students are engaged in learning through Curriculum for Excellence, which was introduced in schools from 2010. CfE aims to provide a holistic approach to learning, to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes. To support CfE and the education system, the Scottish Government has introduced a range of policies and strategies for schools, for education professionals, and to drive system performance to higher levels.

After ten years since its first implementation across schools, a range of issues and tensions have become apparent, highlighted by the Scottish Parliament and Government and other education stakeholders. Indeed, policies need constant revision and adjustment, and this ten-year timeline is an opportunity to review CfE and its implementation from a student perspective: how students progress through the system, especially in the transition from lower-secondary into Senior Phase with CfE.

The ambitions of CfE are to enable each child or young person to be a successful learner, a confident individual, a responsible citizen and an effective contributor. With ten years of practice with CfE in schools, how do students live CfE and their learning as they progress through the system? The analysis undertaken in this report reflects on how CfE has and can deliver the best possible learning experience to prepare students for their future by looking at CfE and its change approach. To respond, the following chapters reflect on:

How has CfE been implemented from a student perspective? Is the CfE design working well for all students as they progress and transition through the system?

How have those shaping CfE been involved, and how can they engage most productively to continue delivering the best possible CfE?

How has the policy environment contributed to CfE reaching all schools consistently?

Has there been a clear and well-structured implementation strategy for CfE from its inception?

References

[25] Donaldson, G. (2010), Teaching Scotland’s Future, https://12f0e760-0d30-7463-594d-b8ce276384f7.filesusr.com/ugd/9502d7_2a1a11e5f9f1d3e835bda0e31833012f.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

[11] European Commission (2020), United Kingdom - Scotland Overview, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/united-kingdom-scotland_en (accessed on 22 March 2021).

[2] Gouëdard, P. et al. (2020), “Curriculum reform: A literature review to support effective implementation”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 239, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/efe8a48c-en.

[3] OECD (2020), “An implementation framework for effective change in schools”, OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No. 9, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4fd4113f-en.

[31] OECD (2020), Curriculum Overload: A Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/3081ceca-en.