Suman Barua

Reality Gives

Fernando Reimers

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Suman Barua

Reality Gives

Fernando Reimers

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Type of intervention: non-governmental (no public organisation in lead role)

Website: www.realitygives.com

Launched in 2009, Reality Gives is a community-based non-profit organisation providing children and youth from poor urban communities access to quality education in India. Its school and youth programmes reach over 1 000 young people living in the slums of Dharavi (Mumbai) and Sanjay Colony (New Delhi) every year.

The School Programme has 1 school leader and 30 teachers, and is aimed at children aged 3-10, from preschool up to 4th grade. The classrooms are child-centred, inclusive and apply an experiential pedagogy.

Reality Gives’ flagship programme – Youth Empowerment – gives youth aged 16-35 from the slums an opportunity to learn English in order to close the employability skills gap. In partnership with experts from the United Kingdom and local community champions, Reality Gives developed a curriculum through a cyclical process of identifying needs, comparing international standards, then bridging the gap given the local context.

Reality Gives’ management decided to close its centres as of 16 March 2020 to protect its students and staff. The project is based in the slum community of Dharavi, which is a hotspot for tourists, making the population more susceptible to contracting COVID-19.

When the government of India announced a nationwide lockdown on 24 March, it became clear to the programme team that their centres would remain closed for a long time. They also realised that they would need to innovate and come up with a new programme designed for online learning as their current curricula were designed for classroom teaching.

The team analysed the situation, taking stock of the available technology infrastructure, talking to students and testing prototypes. They finally found a suitable programme that could work for everyone in their context, using WhatsApp as a means to provide lessons – rather than live streaming options like Zoom or Facebook. After one month of distance learning, the students were satisfied and some hidden benefits emerged, such as more individual feedback for learners.

With the closure of Reality Gives’ centres and classes, English language learners were not able to practice and improve their language skills. Most of the students are first-generation English language learners, and their community sees little or no interest in the use of English. With classes disrupted, students might forget all they have learnt over many months.

Moreover, the students live in very small spaces in the slums, with anywhere between four and ten family members living together. This leaves little room for self-learning. COVID-19 exacerbated the situation, creating more stress and susceptibility to mental illnesses. Families that rarely spent time together because of their hectic lives in Mumbai were now forced to be with each other night and day.

Reality Gives realised that intellectual engagement, especially with a subject that students already enjoyed learning, might help to keep them busy and their minds healthy.

The team came up with the following features of the new programme design:

Simple to deliver. Given the limitation of how much time youth can spend learning on their phones, the information needed to be delivered in small, concise packets of knowledge.

Engaging. The classes have to be fun, interesting, attractive and useful for the learner.

Address needs. In addition to English, it should provide a platform supporting mental health.

Balance. It needs to have an equal combination of online stimuli and work for students to do offline to account for their different paces of learning.

Reality Gives analysed the resources it already had. There was a team of seven experienced English teachers; a comprehensive and contextual English as a second language curriculum, implemented for the past four years; staff, including managers and administrative assistants, in charge of co-ordinating activities; and partnerships with various organisations providing workshops that help students grow.

All students’ information was already registered in the organisation’s online monitoring and evaluation system, making it easy to connect with them.

Next, they had to evaluate the available technology. Over the past few years, India has benefited from extremely cheap data rates for mobile phones. Moreover, most of the targeted youth have their own smartphones. However, testing showed that there were issues with Internet connectivity and dropped calls. The team had to develop a pseudo-live programme instead of providing lessons in real time.

After considering Zoom and Facebook Live, the organisation chose WhatsApp to deliver lessons. Since everyone was already using it, it would take the least amount of time to learn how to use the different features.

Then, they had to decide how to structure the lessons. The current curricula were designed for two-hour in-person lessons a day. After studying the content, each level was broken up into 30 one-hour classes. To ensure that the classes did not go on for months, only the most vital components were kept. To allow for individual feedback, the classes were capped at ten students each (the limit of in-person class was set at 18).

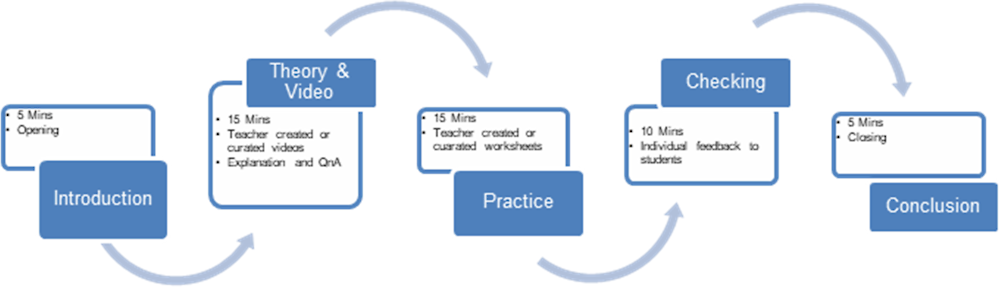

A new class flow was created that divided time between online and offline work.

Once the design was ready, the teachers began fitting the divided curriculum into the new, shorter modules.

In parallel, the managers provided feedback on the lessons, and spoke with their partners regarding possible workshops to support mental health needs, COVID-19 awareness, etc.

Students and teachers are participating in these daily one-hour WhatsApp classes, using text, voice notes, videos and a mark-up feature.

The students’ initial response to the digital delivery of lessons has been very positive. Students are asking a lot of questions and are receiving individual feedback. Teachers and students find that these lessons are a welcome change from their daily lives.

The organisation faced some initial challenges while setting up the programme.

Planning the lessons. The first challenge was converting two-hour in-class lessons into one-hour online ones. The team struggled to condense the lessons while keeping the same quality in terms of pace and opportunities for students to ask questions.

Technological challenges. Teachers and students initially struggled with Internet speeds, which were drastically slower than before the lockdown because of the increased number of people in the area. They also had to adjust to features on WhatsApp that they had not used before, such as audio notes and “mark-up”. Moreover, for the first time, teachers had to learn how to create and store lessons digitally.

Setting boundaries/privacy. Due to the urgency of the situation and in order to facilitate connecting teachers with students, teachers created WhatsApp groups using their personal phone numbers. This created a direct channel between the students and teachers. Although this was a way to build a positive relationship, it was challenging to maintain boundaries. Students were texting and asking for help anytime they liked, making teachers feel like they were working all the time. It was important for the team to implement rules for communication to avoid that.

Lack of motivation because of the lockdown. Another issue was that the staff, teachers and students were not as motivated due to the conditions imposed by the lockdown. The situation in Mumbai and Delhi was a slow, steady climb; the end of the situation was nowhere in sight. An overall feeling of “What’s the point?” developed. It is not a very tangible challenge, but nonetheless a real one.

Given the state of complete lockdown, the organisation prioritises engagement. Without the online programme, students will not be able to improve their level of English. With the programme, students can practice English from their homes. Thus far, the measures of success are flexible and focus on short-term goals.

Participation. How many students are participating in the online programme out of the number that would normally participate in in-person classes? An initial evaluation estimated about 80%. The organisation’s overall goal is to reach 100% of students, but the initial goal is to work towards achieving 80% consistently.

Completion. How many students are able to complete the short modules, and how does the completion rate compare to what would be normally achieved through in-person classes?

Student satisfaction. It is important for the students participating to be satisfied with the programme. Reality Gives will survey the students every other week to evaluate their satisfaction and their experience in order to improve the programme.

Reality Gives’ programme is transferable across many contexts: in an urban slum context for students from low-income backgrounds, and anywhere where data rates are inexpensive and everyone has a mobile phone. Students and teachers also need access to an app, such as WhatsApp or one that young people commonly use, as a means of communication.

It would work in organisations where teachers and staff are willing to try something new and take risks. They would need to adjust to new dimensions in their roles and be comfortable with being in direct contact with students and mature enough to handle young adults. The organisation should be well connected to community members and able to invest in the youth without being in physical contact.

Reality Gives’ solution is highly scalable in India. Once all lessons are ready, it will be a matter of a click‑and-send. The number of students that can participate depends on how many teachers are on board and how many hours they can devote to their students.

There is value in exploring this design after the COVID-19 crisis. Initial feedback shows that this programme might not be able to replace in-person classes as learning outcomes are better. However, online sessions could supplement actual class time to push students to a higher level and achieve their learning goals faster.

1. Before starting the process, take stock of resources – in terms of both tangible resources, such as technology, and more intangible ones, such as the staff’s skills, etc.

2. Given the situation, conveying a sense of urgency is fine, but do not compromise on compassion. No one knows how long the journey back to normalcy will be and staff need support in the long battle ahead.

3. Take stock of the percentage of students that will benefit from the programme. It does not have to be 100%. In the current situation, a majority of students participating is better than nothing.

4. Take advantage of the staff’s strengths. Maybe some of the teachers cannot type out the lessons, as they do not have a computer, so distribute the work to another teacher who has time and a computer.

5. Before the roll-out, try with just one batch of short modules in order to tweak the process before rolling the lessons out to all the students.

6. Management should check in regularly with the team that is working on the transition and implementation, and focus on the support they need.

7. Implement monitoring systems in the spirit of a learning rather than reporting activity. Initially, this will be an experiment, and it is fine to take some time to improve it.

Thank you to Ravi Kumar, Manager; Marchang Rangshingla, Manager; and Letizia De Martino, Executive Director, all from Reality Gives.