Ryoko Tsuneyoshi

University of Tokyo

How Learning Continued during the COVID-19 Pandemic

25. Japan: Tokkatsu, or student-led collaboration on line

Abstract

Type of intervention: governmental (municipal authority and municipal public school)

General description

The Japanese school curriculum includes both subjects and non-subjects as part of the official curriculum. Non-subject education includes a set of activities linked under the umbrella term “tokkatsu”. It is often led by children, is experiential, collaborative and interactive. Such activities encourage, for example, the development of social skills, empathy, discussion skills and the acquisition of basic living habits, integrated with the subjects. In ordinary circumstances, such non-subject education is promoted through extensive face-to-face interaction.

With the pandemic, schools shut down, then have restarted, but class hours were cut and students were behind in core subjects. Moreover, social distancing became the norm, making activities which required close physical contact difficult to practice. Thus, tokkatsu (children’s council activities, school lunch with lunch servers in small groups and school events, etc.) was not possible in its original face-to-face form in many schools. Some educators, however, have started to devise innovative ways in which to promote the non-subject education goals while avoiding the new 3 Cs (closed spaces, close-contact settings, crowded places). The Obiyama Nishi Elementary School, Kumamoto, Japan, provides an example of continuing efforts to promote tokkatsu using online techniques during school closures, and on line alongside face-to-face activities avoiding the 3Cs, after schools’ reopening.

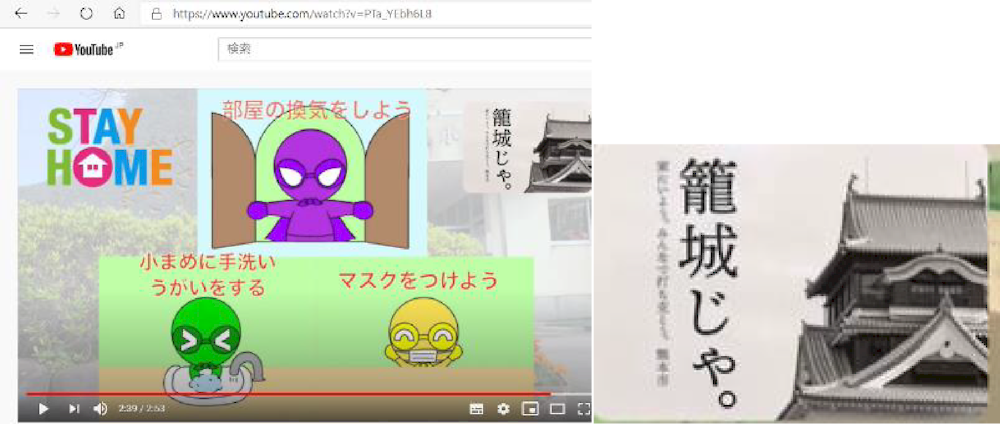

Figure 25.1. One of Obiyama’s YouTube videos on staying at home and overcoming the pandemic

Notes: This is one of Obiyama Nishi’s YouTube videos designed before Japan’s long vacation during the school closures, urging children to stay home and to ventilate, wash their hands, gurgle frequently and wear a mask. These messages would be non-subject learning which the school would have done face-to-face if schools had been open. “Let us stay home and overcome this pandemic together” was the message. The words beside Kumamoto’s ancient castle signify a method of fighting in which warriors stay inside the castle. The image on the right hand side zooms on the Kumamoto’s castle on the top right of the video. The three figures are the school mascots.

Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTa_YEbh6L8.

As soon as schools shut down in March 2020, Obiyama Nishi Elementary School in Kumamoto City started a YouTube video series, and posted one video every school day until school resumed. By 27 May, the school had made 32 YouTube videos. The teachers discussed what they thought the children needed to know during the school closure according to their grade. They made a study plan then developed and edited the videos. The children were given timetables by grade for the shutdown period. Every morning and every afternoon, schedules started with exercise activities or a dance (both provided on YouTube). Classes used LoiLoNote School, seen as helpful in conducting collaborative online interactive lessons; MetaMoJi ClassRoom, which allows collaboration in making newspapers; and Zoom for discussion.

Some of the videos were about non-subject education (see Figure 25.1). In addition, the school also conducted non-subject education, such as classroom discussion and children’s council activities on line.

Here is one example of the children’s council activities:

The principal and teachers decided that their goal was for children to be “excited about school”. They associated this with active learning, etc. The principal explained this goal to the 6th grade committee leaders on line, who then discussed among themselves “what exactly was a school that they would be excited about” and what the committees could do (using Zoom). They then started recruiting 5th graders.

When school reopened, 5th grade representatives of the children’s council joined a committee of their choice, and the children’s council activities started right away. A hybrid approach of online and in-person learning was taken after schools reopened in June. In line with the goals of the children’s council activities of student-led collaboration, children designed activities themselves.

The planning committee in the children’s council, for example, discussed on line what “fun” activities they could come up with without putting their peers at risk of the virus. They came up with a stone, scissors and paper (janken) tournament in which the children, social distancing in their classroom, competed on line with committee members who communicated with the classrooms on line; winners were interviewed Figure 25.2. Children videotaped, edited and posted the video of the activities on line. This was a learning opportunity for children to not only engage in student-led activities, but to learn how to avoid the 3Cs while having fun.

Figure 25.2. A blended model of stone, scissors and paper

Main problems addressed

The main problem addressed here is that the school closures are placing pressure on schools to focus on the subjects, while neglecting the holistic development of social skills, feelings toward others and habits one could learn collaboratively.

Even when schools restart, because COVID has not disappeared, children are asked to practice social distancing, avoiding direct close contact, stay apart instead of working together. This tends to create pressure to focus on subjects and learning which is basically teacher-led and individualised. It has been noted that the schools’ narrow focus on subject matter generally hurts the most vulnerable students who benefit the most from a holistic education.

The principal of Obiyama Nishi Elementary School observed that, with the shutdown, more children were emotionally unstable and worried about school than in previous years. The feeling of belonging, of positive social relationships, of community, lies at the basis of the school experience, helping children learn both academically and otherwise. And according to the principal, children from families which are not struggling economically proved as vulnerable as their more disadvantaged peers. Parents may be so worried about the pandemic that they may transmit their anxiety to their children. Thus, communicating and reassuring parents by email, telephone and in person has also become a concern for teachers.

Because the Japanese curriculum includes both the subjects and the non-subject experiential and collaborative activities, it is apparent to educators that a portion of the curriculum is not being adequately practiced because of the nature of the present pandemic. This has often pushed teachers to experiment with how the same goals that had been promoted through extensive face-to-face interaction could be arranged in a way that avoided the 3Cs. Although the structure of the Japanese curriculum may heighten the need for such learning that cannot be taught through the subject matter alone, the children’s need for social and emotional support, collaboration, bonding and linking with others is universal in itself.

The main feature of the present practice is to encourage children to design their own activities while preventing oneself and others from becoming infected, assuming it helps them understand the pandemic without letting it get in the way of having “fun” together and developing their socio-emotional skills in spite of social distancing.

Mobilising and developing resources

There were a few existing resources the school could mobilise, especially because the school had experienced a large earthquake.

Disasters, not just pandemics, often push educators to experiment with techniques they would otherwise not have used. The Kumamoto Earthquake in 2016 and the disruption of schooling it induced pushed the municipality to strengthen its online outreach. This online expansion was used during the COVID-19 school shutdown and the reopening period. On 15 April 2020, thanks to its prior online preparation, Kumamoto City was able to start online classes for all of its municipal schoolchildren from 3rd grade onward to junior high school in response to the shutdown of schools in Japan (the school year starts in April). Obiyama Nishi’s YouTube started earlier than this, in March.

New aspects also had to be developed for the particular COVID-19 context.

Kumamoto City was able to build on the online outreach put into place following the Kumamoto Earthquake. However, natural disasters hit, then things start to go back to normal as buildings are repaired, etc. Viruses are different: they seem to almost disappear, then suddenly reappear, and the cycle goes on and on. In addition, contrary to COVID-19, the earthquake never necessitated social distancing. The children could be asked to collaborate and work together in close contact to repair their school with the many volunteers and community members.

COVID-19 has brought about a totally new situation in which even when schools reopened, children could not socialise. The pandemic had made a large part of Japan’s curriculum (non-subject) difficult to conduct as usual, as it usually requires extensive face-to-face interaction.

In the example above, the children in the planning committee organised their “fun” activity while avoiding the 3Cs. Non-subject learning, such as classroom discussion, tends to focus on encouraging children to understand the meaning of why a certain behaviour (e.g. cleaning) is necessary. The children’s council, which as a learning tool encourages self-motivated behaviour, was now utilised during the pandemic for self-motivated behaviour change (e.g. social distancing).

Fostering effective use and learning

The Obiyama Nishi Elementary School’s daily timetable was such that it tried to continue the holistic framework which included both subjects and non-subjects even during the school closure. The school provided subject instruction on line, as well as non-subject education on line, such as children’s council activities. Obiyama Nishi’s council activities, first entirely on line during the shutdown, combined online and face-to-face interaction after schools reopened. In a pandemic that may continue for a long time, and given the fact that other global viruses are likely to emerge in the future, it is important for children to learn how to go on with their lives (having fun) while understanding how to control the possible threat. Encouraging the children’s council to lead and design some of the online and hybrid activities was a way to engage students more in their learning.

The shutdown lasted for three months. In a questionnaire given to 5th and 6th graders about whether they were able to spend their time meaningfully (a non-subject education goal) and to advance their studies (a subject education goal) in “a self-initiated manner” during the shutdown, 85% of pupils and 80% of parents answered positively. This was seen as an encouraging result by the school staff.

Implementation challenges

According to the principal of Obiyama Nishi Elementary School, the main implementation challenges were gaps regarding access to the Internet, and familiarity with the online applications used for teaching and learning (LioLoNote School, Zoom, MetaMoJi ClassRoom, Microsoft Teams).

As was mentioned above, Kumamoto City had allocated a number of tablets to each school in response to the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. However, when the present pandemic began, there were not enough tablets for all children, since until the pandemic, individualised usage was not necessary. Because of the way COVID-19 spread, children could not cluster together in front of one tablet, and the school checked which families were able to access online resources using their own devices. Smartphones were used by some families as well, using the LioLoNote smartphone software. Families that did not have Internet access were provided with tablets. The tablets are cellular models, considered easier for families without Wi-Fi.

The school used several types of software for different purposes. LoiLoNote was used for online interactive classes, combined with Zoom breakout sessions. This continued into the reopening period, since teachers were able to conduct collaborative activities without children physically clustering together. During the shutdown, teachers utilised YouTube, which was seen as especially effective for 1st graders. They also combined this with the usual telephone calls, and emails. Microsoft Teams was used among the teachers.

In the beginning, not all teachers were comfortable with the IT applications used. The school offered 30‑minute training sessions for teachers once a week since 2019 as the city strengthened its commitment to online learning. Zoom was used for the morning faculty meetings and the grade level faculty meetings, and Microsoft Teams was used to share information.

As for YouTube, it took about one hour to shoot the videos and another two hours to edit them. Teachers discussed by grade what they wanted the children to see then divided the labour among themselves.

Monitoring success

As this note reports a school initiative, there was no “monitoring” as such – beyond the traditional ways of monitoring that students do what they are asked to do. Most of the monitoring of the success was about making sure that stakeholders remained engaged in their learning, and about following up if that was not the case.

YouTube sessions that were subject-based included tasks that the children had to do. Should children not submit the requested tasks, teachers would call their home and talk to the child. Notice of the online classes was sent to children using LoiLoNote, and emails were used for parents. The school homepage was used as well. Teachers supported parents through telephone calls, and at times, parents would come in person to the school.

Adaptability to new contexts

The challenge to designing a holistic learning experience, which addresses the child’s learning in a holistic way, is universal. The pandemic and the social distancing it brings made the need for a holistic education even more tangible in many parts of the world. Each country has its social context which will influence what and how such education is possible.

Some key steps in the children’s council and committee activities in the present example are outlined below.

1. Children representatives from 4th to 6th grade form a children’s council. Various sub-committees which differ by the needs of the children and school are set (e.g. planning committee, beautifying the environment committee, the newspaper committee which issues school newsletters, etc.). Information was exchanged using LoiLoNote School.

2. The 6th graders (last year of elementary school in Japan) lead the sub-committees. The committee heads are briefed on some of the goals for the school for that year by the principal on line (Zoom). Then each committee discusses on line what they want to do for this school year. They then recruit the younger grades. The activities are child-led, with the teacher serving as a mediator. In this example, the breakout rooms function on Zoom was used.

3. The 5th graders chose the committee they wanted to join. Each committee started to organise their individual activities as seen in the example above.

Establishing such an organisation, even on a temporary basis when it does not already exist, is possible in any context – although it may pose some different challenges in terms of making the committees alive and functional. In any event, this is not an organisation that requires any particular resources beyond access to online resources and software applications.

Box 25.1. Key points to keep in mind for a successful adaptation

1. Identify the non-subject aspects of your curriculum and ensure they are part of your education continuity strategy.

2. Support students to understand what the health crisis means for them, and support their families as needed.

3. Establish a children’s council and ask students to lead activities that are both fun and make them understand and internalise new restrictions related to the COVID-19 crisis.

4. Remain in constant contact with students and their families and ensure they get used to communicating using online software.

5. Use online tools in a flexible manner, since the COVID-19 situation changes daily, and ensure that there is a smooth transition from one stage to another (e.g. from school closure to school reopening).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Mr. Osamu Hirano, Principal of Kumamoto City, Obiyama Nishi Elementary School and Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin, Senior Analyst at the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.