This chapter provides an overview of the country responses to the OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021, which asked countries to provide information on their priorities for tax policy and gender equality, information on implicit and explicit bias, data available for analysis of tax policy, inclusion of gender outcomes in the tax policy design process, tax administration and compliance, and priorities for future work.

Tax Policy and Gender Equality

3. Country approaches to tax policy and gender equity

3.1. Priorities for tax policy and gender equality, and links to the SDGs

The objective of improving gender equality is an international priority, notably as the fifth sustainable development goal (SDG 5), which calls on countries to achieve gender equality. Tax policy can be a tool to contribute to this objective, with various design considerations having the potential to increase gender equality. The SDGs call for countries to ensure that development and domestic resource mobilisation efforts, including tax policy interventions, do not negatively affect desired outcomes in the area of gender equality.

This chapter provides insights on country views on the role of tax policy design in supporting gender equality and domestic resource mobilisation.

3.1.1. Gender considerations in tax policy design

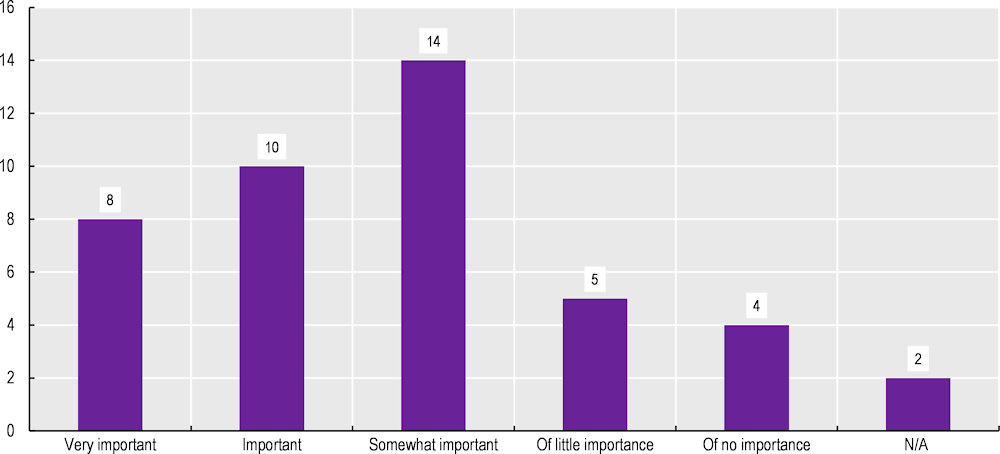

Gender considerations in tax policy design is considered to be at least somewhat important in two-thirds of the countries that replied. Thirty-two out of 43 countries (74%) reported this as "important" (from ‘somewhat important’ to ‘very important’) (Figure 3.1). Nine countries indicated that it was of little or no importance.

Figure 3.1. How prominent are gender considerations in tax policy design in your country?

Countries were asked whether the goal of tax policy should be to aim at gender neutrality, or to go beyond gender neutrality to consider using the tax system to compensate for existing gender distortions in society. Three-quarters of the countries that responded (32 countries or 74% of respondent countries) considered that the tax system should aim for gender neutrality. Among this group of countries, several countries indicated the importance of seeking to improve gender equality in society outside the tax system via other policy interventions, e.g. by reducing income inequalities or by social expenditure provisions (Estonia, Finland, Indonesia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Uruguay). Even when recognising that the tax system should be neutral, France noted that certain tax policy choices, including in the area of personal income taxation, could have an impact on resource allocation among individuals and therefore reduce existing distortions. The United States also noted that to the extent the tax system creates work disincentives for second earners and caregivers, the tax system should aim to reduce these distortions.

Five countries (Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica and Kenya) indicated that the tax system should aim to reduce or compensate for existing biases. Austria and Belgium noted that this falls within broader political strategies and goals to ensure the integration of differences between men’s and women’s circumstances are considered in policy design. Four countries (Iceland, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland) indicated that to some degree, the tax system could pursue both gender neutrality and reducing biases. Ireland indicated that the matter was currently under review by its Equality Budgeting Expert Advisory Group and an Interdepartmental Working Group. Spain mentioned that fiscal measures should be neutral in principle, and should try to correct inequalities where there is discrimination, acknowledging the differences in opportunities and economic outcomes for men and women.

Countries were also asked to report whether or not their tax mix has an impact on gender equality. Twenty-three countries (53%) reported that their tax mix was neutral.1 Germany and Italy noted that the primary impact of the tax system on gender outcomes was due to the design of taxes, rather than to the tax mix. Ireland noted that its Commission on Taxation and Welfare is considering the impact of the tax mix on a number of outcomes, including gender. In addition to these countries, Finland, Norway and Portugal noted that while the tax system is neutral, its interaction with elements of society may not be. In particular:

Finland indicated that while different tax types may have differential impacts, they result primarily from differences in underlying factors, e.g. income, noting that in Finland, the share of progressive income taxes in the tax mix is high, which can be beneficial for women.

Norway noted that the distribution of economic assets, primarily wealth, is skewed by gender, leading to potential implicit bias in that changes in the net wealth tax can affect men and women differently.

Portugal noted that gender equality cannot be dissociated from other social goals such as combating poverty. In that regard, Portugal considers that tax measures that have improved the progressivity of general tax system (namely in what concerns the tax rate structure, personal tax credits and value-added tax (VAT) rates applied to gas and electricity) had a significant indirect impact on gender equality.

Among the 17 countries (40% of total respondents) that consider the structure of their country’s tax mix affects gender equality,2 several different types of impacts were described:

Australia noted that their PIT system treats men and women in the same circumstances with the same taxable income consistently.

A few countries indicated that the tax mix could contribute to reducing gender inequality, including:

Indonesia, which noted that gender responsive policies have been integrated into some tax regulations e.g. a married woman can now choose to obtain her own Taxpayer Identification Number, working hours for male and female staff have been adjusted to encourage equitable engagement and increase productivity, women-friendly facilities such as a lactation room, priority parking, have been implemented.

South Africa indicated that its tax mix is informed by their high level of income inequality, resulting in reliance on direct taxes (which constitute about two-thirds of tax revenue). The South African PIT design is highly progressive and can be seen as correcting for gender biases in the labour market.

The United States noted that although the structure of the tax system does not treat women and men differently, it may impact gender equality through its interaction with gender differences in income, family structure and unpaid work. For example, the progressivity of the personal income tax and the refundable earned income tax credit are beneficial for women due to the gender income gap and the prevalence of female-headed single-parent households; whereas the adoption of the household as the unit of personal income taxation and the proportionality/regressivity of the SSC rate schedule may disadvantage women.

By contrast, several countries indicated that the impact of the tax mix could contribute to worsening gender bias:

Argentina indicated that VAT weighs relatively more heavily on women, who are over-represented in the lower income deciles. In Argentina, VAT and income taxes (both corporate and individual) represent more than 50% of tax revenues.

Estonia noted that while the exact impact of the tax mix is unclear, it is likely that the prevalence of male ownership of business and investment assets in the wealthiest income distribution group could lead to these men having a tax advantage, given that income from business ownership and investments bears a relatively lower tax burden compared to labour.

France indicated that tax policy can impact gender equality through labour participation, since taxation on a household basis can reduce the incentives for second earners to work – noting that in different-sex couples that are married or in civil partnerships, 78% of second earners are women (according to the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies)3 – although this impact of the tax system cannot be considered in isolation from social and family benefits and allowances applied on a household basis, as well as other policy measures such as those relating to childcare.

The Netherlands stated that the mix between individual and household taxes can affect the division of labour in the household.

The United Kingdom, stated that where women are more likely to be engaged in certain types of economic activities that are taxed differently or do not qualify for incentives, the overall impact of taxation may differ by gender, although the impact of the taxation of different sectors on women is not assessed. One example of this is that tax deductions for machinery-heavy businesses benefit men disproportionately.

Finally, two countries noted various avenues by which the tax mix might have a differing impact by gender, also emphasising that the design of each tax is important in determining the gender impact of the tax mix:

Mexico noted that while VAT is regressive when analysed alone, suggesting a bias against lower-income households (where women are over-represented), other features of VAT design contain elements which could reduce this bias. Similarly, elsewhere in the tax system benefits favour low-income households, which can generate implicit biases in favour of women.

In Uruguay, although the design of indirect taxes is explicitly neutral in the legislation, exemptions or reduced tax rates for certain goods and services may interact with differential consumption patterns between men and women in ways that can distort the gender neutrality of the tax mix.

Twenty-two out of 43 countries (51% of respondents) indicated that tax policies or reforms have been implemented with gender equity forming one of the main rationales for the policy decision (Table 3.1). Seventeen countries indicated that reforms have not been implemented with gender equity in mind, and four countries did not respond to this question.

Table 3.1. Have any tax policies/measures or reforms been implemented with gender equity forming one of the main rationales for the policy decision

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

22 |

51.2% |

Argentina; Belgium; Estonia; France, Iceland; Indonesia; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Kenya; Luxembourg; Mexico; Netherlands; Norway; Saudi Arabia; South Africa; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Ukraine; Uruguay; United States |

|

No |

17 |

40.5% |

Australia; Austria; Brazil; Canada; Costa Rica; Croatia; Finland; Germany; Greece, Hungary; Montenegro; New Zealand; Peru; Romania; San Marino; Tunisia; United Kingdom |

Note: Four countries (9.3%) did not reply to this question.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Among the countries that have implemented tax reforms where gender equity was a main rationale for the reform, countries noted several examples:

Belgium adopted a royal decree on 10 December 2017 introducing a reduced rate for feminine sanitary products. France enacted a similar measure as of 1 January 2016. Australia (from 2019), Mexico (from 1 January 2022) and South Africa also apply a zero-rate on sanitary products, which are also subject to reduced rates in Kenya (Kidwingira, Mshana, Okyere, 2011[1]) and Iceland.

Since 2017 in France, a single, divorced or separated parent living alone with at least one dependent child has benefited from an additional half share under household-based income tax rules (for the calculation of the family quotient, the basis of the French personal income tax system). This measure predominantly benefits women, who are overrepresented among single-parent families – France reported that in 2018, 83.2% of parents in single-parent families were women.

In Israel, the number of tax credit points for a child under five are equal for the mother and the father. The mother of a child aged 6-17 is entitled to one tax credit point every year and to half a tax credit point in the year the child turns 18. Additionally, women can decide to postpone one credit point from the child’s birth year to the following year. Women’s extra credit points are a means to address their lower earnings relative to men.

In Italy, following the “Gender Budget 2019” (Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2019[2]), the 2020 budget law enacted numerous equal opportunity measures, among which the renewal of temporary or pilot initiatives such as the birth allowance (‘baby bonus’), the ‘nursery bonus’, the women's early retirement loan, and the ‘women's option’ early retirement scheme.

In Norway, under the “tax class 2” (“skatteklasse 2”), partners or registered spouses could be taxed together, which was beneficial if one of the spouses or partners had income below a certain threshold. The removal of tax class 2 in 2019 was partially motivated by the need to improve work incentives for women.

In Saudi Arabia, the horizontal Vision 2030 plan aims to empower women and to increase their participation in the workforce. Among specific measures, a monthly allowance is paid to divorced women provided certain conditions are met, and a special transportation allowance is provided to women to help work commuting.

Spain mentioned the Organic Law 3-2007 for promoting effective equality of women and men with regard to access to employment, professional training and promotion, working conditions and access to goods and services and their supply. Since 1971, labour income has been taxed on an individual basis in Sweden. In addition, every year a general analysis of the effects on economic equality resulting from the government’s policy actions, including tax policy, is undertaken (Government of Sweden, 2020[3]).

In the United States, several reforms have been carried out with gender-related goals in mind. These include:

The amendment of a deduction for dependents that was able to be claimed only by a woman, widower or a husband with an incapacitated wife, to extend it to all eligible persons regardless of gender;

A secondary earner deduction in force between 1981 and 1986 was designed to reduce inequality between single-earner and dual-earner married couples;

A child and dependent care tax credit was introduced in 1976 to improve work incentives for families with children;

Over the last twenty years, a range of policies have been created to reduce taxation of married couples and the marginal effective tax rates for second earners, including an expansion of the earned income tax credit;

Several states are considering excluding feminine hygiene products from the sales tax base.

3.1.2. Targeted Measures

In the taxation of personal income, 27 of the respondent countries (i.e. 63% of total respondents) base taxation on an individual unit. Six countries (Belgium, France, Iceland, Indonesia, Switzerland and the United States) use a household unit and nine countries allow taxpayers to choose between the individual and household unit.

Table 3.2. Does your system apply individual or household-based income taxation?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Individual unit |

27 |

62.8% |

Argentina; Australia; Austria; Canada; Croatia; Costa Rica; Estonia; Finland; Greece; Hungary; Israel; Italy; Kenya; Latvia; Mexico; Montenegro; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Romania; San Marino; Slovak Republic; Slovenia; South Africa; Sweden; Tunisia; United Kingdom |

|

Household unit |

6 |

13.9% |

Belgium; France; Iceland; Indonesia; Switzerland; United States |

|

Optional between individual and household unit |

8 |

18.6% |

Brazil; Germany; Ireland; Luxembourg; Netherlands; Portugal; Spain; Ukraine |

Note: One country (2.3%) did not reply to this question. In addition, Saudi Arabia does not have a personal income tax and is therefore not included.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Most countries with individual taxation indicated that this unit of taxation results in encouraging female labour supply and improves equality. For Australia, individual taxation allows the second earner to have access to the tax-free threshold, which encourages work force participation. Austria notes that various studies have indicated that household-based income taxation entails negative work incentives for second earners, whereas individual-based income taxation is more neutral for gender equality. France, Mexico and the United Kingdom also highlight the detrimental impact of household taxation on gender equity via its impact on the marginal tax rates of second-earners and consequent negative labour supply effects for women. This can result in high marginal tax rates on second earners looking to enter work or to move from part-time to full-time work (OECD, 2019[4]) (Harding, Paturot and Simon, 2022 (forthcoming)[5]). In France, the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies estimated that because of household taxation women face a higher marginal tax rate, by 5.9 percentage points on average, compared to what it would be if they were taxed separately – even though other measures such as family allowances can incentivise the second earner’s labour participation. ( (INSEE, 2019[6])) In the United States, household taxation was enacted in 1948. (LaLumia, 2008[7]) estimated that this resulted in a decline of approximately 2 percentage points in the employment rate of married women, but had no impact on the labour force participation of married men.

Many countries tax personal income on an individual basis but apply tax credits or allowances on a household basis. For example, in Hungary, PIT is based on individual income, but a few measures (e.g. family allowances) can be shared among parents (not linked to marital status). Many other countries also have family-based tax credits or allowances that can lead to higher tax rates on second earners (OECD, 2016[8]). A few countries offer tax allowances or tax deductions for spouses that are not working or that have incomes below a certain limit. These spousal provisions can also have the impact of depressing second earner labour supply by providing incentives for second earners not to work or to remain under the salary threshold (e.g. by working part-time), as highlighted in (OECD, 2019[9]) in relation to the spousal deduction in Japan.

Other countries use an individual tax basis for income taxation, but a combined base for other taxes; for example, in Norway, for net wealth tax purposes, spouses are taxed together. In Greece, spouses file a joint return but each spouse is liable for the tax payable on his or her share of the joint income. In Hungary, the tax unit is, in all cases, the separate individual. However, in exceptional cases, the household can become subject to PIT, for instance in the case of benefits in kind. In the United Kingdom, the tax unit is the individual, but certain reliefs depend on family circumstances such as a marriage allowance which allows the transfer of 10% of an individual’s personal allowance to their husband, wife or civil partner. The allowance is restricted to couples where the higher earner is a basic rate taxpayer and is only beneficial if the lower earner has a tax liability below the personal allowance. The allowance has to be claimed and is given only to those who meet the eligibility criteria.

Countries that allow for some or all elements of personal taxation to apply on a household basis note that the use of household-based taxation may have other benefits for gender equality, particularly for low-income taxpayers. Iceland, which also uses a household-based system, noted that joint taxation “has been systematically reduced” to encourage labour participation of the lowest paid, usually women. The law allows single people living together to choose between individual and household taxation. It also treats single-parent households, more commonly women, in the same way as dual-income households at the same income level. The federal government is currently planning a wide-ranging tax reform that is expected to bring change to this aspect of the tax legislation. The government plans a comprehensive income tax reform for 2020 involving: 1) lower tax rates for minimum-wage earners; 2) a new indexation mechanism to strengthen stabilisation properties of income taxes; and 3) improved neutrality of the tax system with respect to gender and civil status.

Although using a household-based system, Belgium took action to reform its PIT towards a system based more on individual taxation over the period 2001-2004 (Orsini, 2005[10]). Further, in 2006 Belgium introduced a change to the dependent child regime to better accommodate separated couples, known as tax co-parenting. This provision was extended to include individuals over 18, in 2016 (Federal Public Service Finance of Belgium, 2021[11]). Belgium indicated that although several reforms have been approved to move towards greater individualisation of rights (in 1988 and 2001), there are still some provisions that are not individualised.

Several other countries allow the taxpayer to choose individual or household-based taxation depending on their circumstances. Luxembourg indicated that spouses and partners are taxed jointly on their income, although from 2018 onwards, there have been options to file separate tax returns for married couples and civil partners. Luxembourg therefore does not consider the taxpayer unit to have a direct impact on gender equality, although notes that it may provide indirect incentives for the labour participation of the second earner. Spain also allows family units to choose between individual or joint tax returns, and indicated that it considers this optionality to benefit individuals with lower incomes, thus reducing gender inequality. In Ireland, the report “Taxation, work and gender equality in Ireland” (Doorley, 2018[12]) investigated whether Ireland’s move from joint filing to partial individualisation of income tax had any effect on female labour supply and caring duties. The report, explaining the importance of removing barriers to work for all those who are willing and able to work, and exploring gender differences in labour market behaviour, found that the labour force participation rate of married women increased by 5-6 percentage points in the wake of the reform, hours of work increased by two hours per week and hours of unpaid childcare decreased by approximately the same margin. The Netherlands indicated that the Dutch tax system includes elements of both household and individual taxation. In principle, the unit of taxation in the PIT is the individual; however, if two people are partners for tax purposes, they can divide most deductions and some personal income components (including income from substantial interest, savings and investments) between them.

The majority of the countries surveyed (38 out of 43 – i.e. 88%) indicated that informal taxation – defined in (Olken, 2011[13]) as “a system of local public goods finance co-ordinated by public officials but enforced socially rather than through the formal legal system” – is not common or has very little presence in their country. Four countries – Kenya and Italy (very common), Argentina and Ukraine (to some degree) – indicated that informal taxation was present, and one country did not respond. Kenya indicated that the informal sector accounts for 30% of GDP and that it is considered to worsen gender bias.

3.1.3. Impact of COVID-19

Over two-thirds of the countries surveyed (30 out of 43 – 70%) indicated that COVID-19 did not necessarily worsen the risk of gender bias in the tax system. Some of these countries (Canada, Kenya and San Marino) noted that women have been impacted more than men during the COVID-19 crisis, but that this has had no, or very little, impact on the risk of gender bias in the tax system.

Nine countries indicated that COVID-19 had worsened the risk of gender bias in the tax system (Argentina, Australia, Iceland, Indonesia, Ireland, Mexico, Norway, Spain and the United Kingdom). Among these countries:

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the informal sector in Argentina. In particular, domestic services, which account for 25% of informal sector employment and 17% of employed women in Argentina, were severely affected, thus deepening the income and gender gaps (Ministerio de Economía, 2021[14]) (UNICEF and DNEIyG, 2021[15]).

Australia noted that under the Australian PIT system, a man and a woman with the same level and nature of taxable income will pay the same amount of tax. Therefore, COVID-19 will have only affected the gender distribution of tax paid to the extent it affected the underlying distribution of income between men and women in society more broadly.

In Iceland, the VAT refund system was reformed during the pandemic to allow temporary refunds of construction projects and car repairs, which is more likely to have benefited male-dominated sectors.

Spain indicated that over 50% of women's employment is concentrated in four sectors (commerce, tourism, education, health and social services) that were directly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the recovery of employment in Spain between the second and third quarter of 2020 was somewhat higher for men than for women, widening the gender gap. Spain also noted that unpaid care tasks increased, both in caring for children and for dependent and elderly people, also revealing gender inequalities (BBVA, 2020[16]). According to Eurostat-INE data, in Spain, 95% of women are involved in the care of their children on a daily basis, compared to 68% of men. The lack of equal responsibility means that a greater burden of childcare may be falling largely on women, hindering in most cases their labour force participation (Castellanos-Torres, Mateos and Chilet-Rosell, 2020[17]).

Eleven out of 43 countries (26% of respondents) (Argentina, Australia, Austria, Canada, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom) indicated that tax policy measures introduced in response to COVID-19 were assessed for their gender impacts.

Argentina implemented a number of measures specifically designed to protect women, non-binary employees and other vulnerable groups in the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of measures to promote the knowledge-based economy, a higher tax deduction was allowed for the employer SSC payments made for women, non-binary workers, those with disabilities, or long-term unemployed (80% compared to 70% for other workers; (Congress of Argentina, 2020[18])); higher deductions were introduced for the director or trustee fees of women or non-binary directors, as part of measures to introduce a gender-lens to corporate income taxation (Ministerio de Economía, 2021[19])) and an “Accompany” programme was put in place for people at risk of gender-based violence (Ministerio de Economía, 2021[20]).

Australia’s Treasury undertook a distributional analysis, including a gender analysis, of the impact of extending the LMITO (low and middle income tax offset) for the 2021-22 income year. Ireland published a study on 'The gender gap in income and the COVID-19 pandemic' (Doorley, O'Donoghue and Sologon, 2021[21]), which found that the gender gap is smaller after taxes. It notes that men’s market income remains higher than women’s, although they suffer slightly higher loss of employment, so men continue to pay systematically more tax than women. Prior to the pandemic, the tax-benefit system was reducing the gender income gap from 40% to 35%. However, this analysis shows that the cushioning effect of the tax and welfare systems has doubled during the pandemic.

Austria shared its willingness to contribute to impact measures targeted on the “Gender Equality goal” in the 2020 federal budget enabling the tax system to provide positive incentives to increase the employment rate.

In Canada, as required by the Canadian Gender Budgeting Act, all tax and resource allocation decisions must consider gender and diversity impacts. Canada has introduced a number of measures to support individuals and businesses through the COVID-19 pandemic (Government of Canada, 2020[22]).

In Spain, an assessment on gender impact is included in all regulatory projects including the measures taken in response to COVID-19.

3.2. Explicit bias

Explicit bias occurs when tax policy or tax administration settings differ for men and women, e.g. in the legislation, regulation, or other legal standards. It can include different tax rates or thresholds for men and women, explicit tax credits or taxes applying to only one gender, and tax administration arrangements that differ by gender (e.g. different access to information for men and women).

This chapter describes country responses to questions on examples of explicit bias that apply to either gender (including measures that advantage as well as disadvantage women, or where a different treatment is prescribed by gender, whatever the treatment), both currently and on a historic basis.

3.2.1. Explicit bias in current tax systems

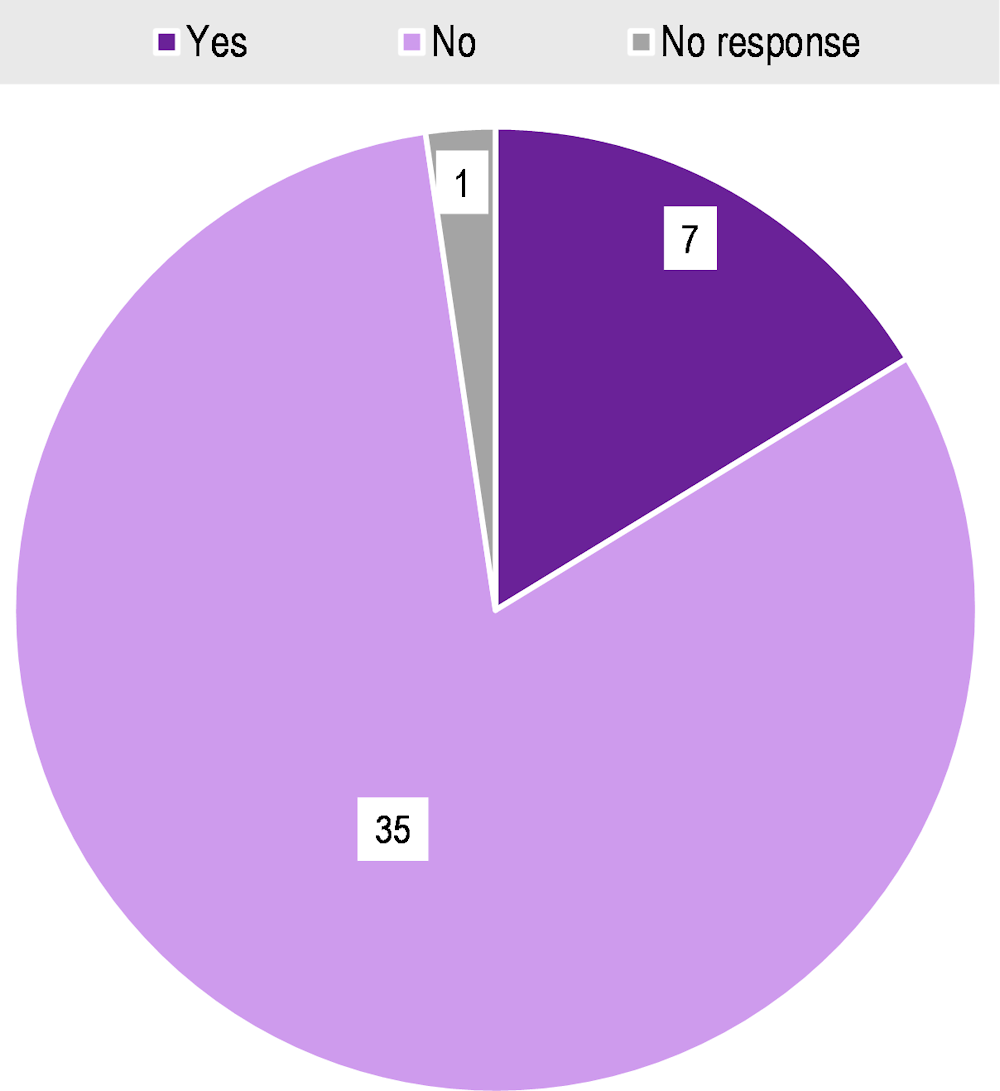

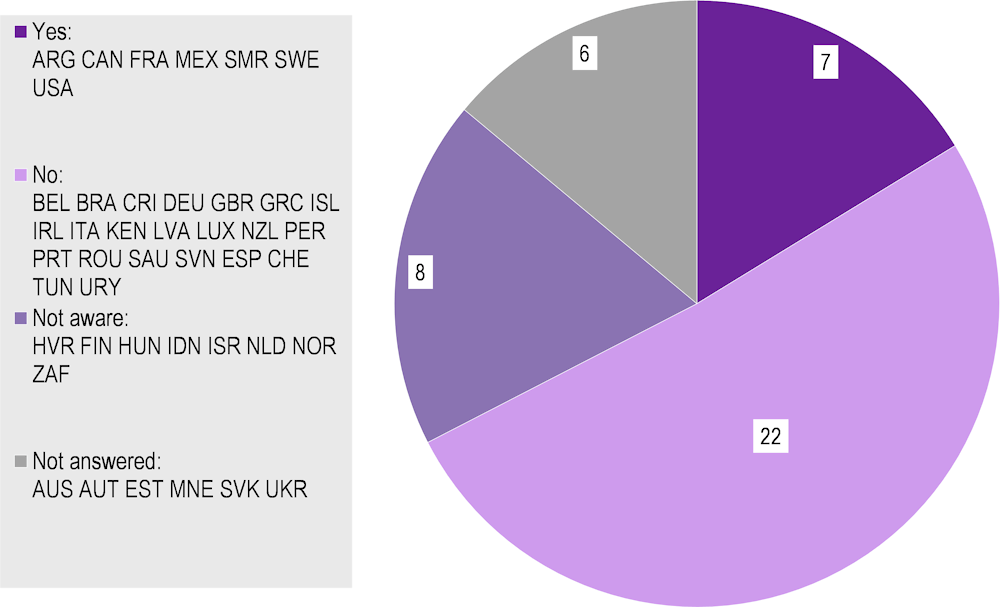

Very few countries (7 out of the 43 respondent countries) reported instances of explicit bias in their current tax systems (Argentina, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, South Africa, Spain and Switzerland).

Argentina, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Spain and Switzerland reported that explicit bias exists in their PIT system (allowances, tax credits, rates or thresholds). In particular:

In Argentina prior to the modification of the Civil Code in 2015, the assets of a married couple were attributed to the husband, with some exceptions (Article 18, Decreto 281/97 de la Administración Pública Nacional), which made women invisible as taxpayers with respect to these assets. On the other hand, Argentina also implemented measures with explicit biases to compensate for gender distortions, including to promote the inclusion of women and transgender people in the formal economy in certain regions, to implement deductions for the expenses of day-care and kindergartens for parents of children under three, and for family charges for cohabitating partners (instead of only for married couples).

In Hungary, since 2020, mothers with four or more children receive a special PIT allowance. This allowance is available only to mothers, whereas a general family tax allowance is available for both parents.

In Israel, the measure postponing tax credit points and offering extra credit points to women (as described in Chapter 3) is also an example of explicit bias.

The Spanish tax system also provides for a maternity deduction for children under three years of age of up to EUR 1 200 per year for each child born or adopted in Spain under Law 35/2006 on personal income tax.

Switzerland noted that its PIT rates include bias. In Switzerland, the subject of income taxation is the household (although only if the couple is married). Household taxation combined with a progressive rate schedule leads to poor incentives for a second earner to find employment, who is often the female partner. The Supreme Court noted in 1986 that the situation is unconstitutional; however, parliament has not yet agreed on a solution and the situation has been partially remedied by means of a second earner deduction. There remain a large number of households that are still facing a “marriage penalty” in federal income taxation. In addition, a (married) household is registered and filed under the husband’s name as the head of the household, regardless of who the main earner is.

In this area of social security contributions (SSCs), few countries reported examples of explicit bias. However, in Spain self-employed workers can apply a flat rate regime under certain circumstances. This regime is established for up to 30 years for men and up to 35 years for women, so that women have a time extension of the tax advantage.4 In addition, self-employed women have other explicit advantages such as aid for single pregnant women and for single women with a child, and 16 weeks of maternity leave – with an amount of the subsidy equivalent to 100% of the contribution base. Finally, Spain indicated that women that are victims of gender violence and who must suspend their professional activity to protect themselves can receive a 100% bonus in the “freelance fee” (Debitoor, 2021[23]). In Argentina, employer SSCs were reduced in 2020 to incentivise the hiring of women, transgender people, people with disabilities and the long-term unemployed.

South Africa reported that VAT/GST has explicit bias such as the zero-rating of sanitary products. Other countries also have preferential treatment for sanitary products. The United Kingdom announced that it will apply a zero-rate to feminine hygiene products as of 1 January 2021 (OECD, 2020[24]). In addition, Belgium’s federal government adopted a royal decree on 10 December 2017 introducing a reduced rate for sanitary products. In Kenya, a tax exemption was applied to sanitary products in 2004 and in 2019 Kenya was the first country in the world to create a national Menstrual Hygiene Management policy (Ministry of Health, 2019[25]) in order to provide women, girls, men and boys with information on menstruation. Iceland also provided, for menstrual products, a reduced VAT rate of 11% relative to the standard rate of 24% (see the Priorities for tax policy and gender equality section). Similarly, from 1 January 2022 a zero rate for these products applies in Mexico to promote gender equality.

Figure 3.2. Are there any examples of explicit bias in the current tax system of your country?

3.2.2. Historic explicit bias

Three countries noted that there had been examples of explicit bias in its tax system that had since been repealed. Argentina repealed the abovementioned PIT provision, whereby marital property was attributed to the husband unless the property had been acquired by the wife prior to marriage. This gender bias was eliminated in 2017 when it was made explicit that both spouses are taxed individually on their assets and on 50% of the marital assets. Between 1980 and 1999, Ireland operated a system of income splitting, whereby married couples could reduce their tax bill by sharing allowances and rate bands between partners. In 1993, Ireland removed the requirement for this joint filing to be done in the name of the husband (Stotsky, 1996[26]). This was accompanied by other reforms to reduce implicit incentives, including the partial income tax individualisation (of the standard rate income tax bands) in 2000 with the objective to increase incentives for second earners to work and to boost female labour force participation. A final reform took place in 2002 when the standard rate bands for singles and two-earner couples were increased by 10% more than the standard rate band for one-earner couples. Whilst individualisation is beneficial to single earners, it is less favourable to single income families whose income exceeds the married one-earner tax band (currently EUR 44 300). To redress this, a tapered home careers tax credit (HCC) was introduced and has been gradually increased and extended over time.

The United States noted an explicit bias in a deduction for the expenses of the care of certain dependents in section 214 of the Internal Revenue Code. This section allowed deductions to be claimed by “a woman or widower” or “a husband whose wife is incapacited or is institutionalized”. This section was amended from 1972 to allow for a broader eligibility regardless of gender.

In addition to the information provided by countries in their responses to the survey, (Stotsky, 1996[26]) noted a range of historic examples of explicit bias in the countries considered, which have since been reformed. Before 1983, in France, only the husband was required to sign a family return, whereas now both partners must do so; similarly in 1990, the United Kingdom moved from joint filing in the name of the husband to a separate assessment for both individuals. Both the Netherlands and South Africa historically imposed a higher tax burden on married women than on married men: in the Netherlands via a higher tax free allowance for married men (before 1984) and in South Africa via a higher rate schedule for single individuals and married women than for married men (reformed in 1995) (Stotsky, 1996[26]).

3.3. Implicit bias

Implicit gender bias occurs when, due to the gendered patterns of social arrangement, gender pay gaps and economic behaviour, the outcome of tax policy or administration has different implications for men than for women, and so impact on gender equity (for example in most countries the second earner in a household is likely to be female, the tax treatment of second earners may therefore impact gender equity). As with explicit bias, it can occur to the detriment of either gender.

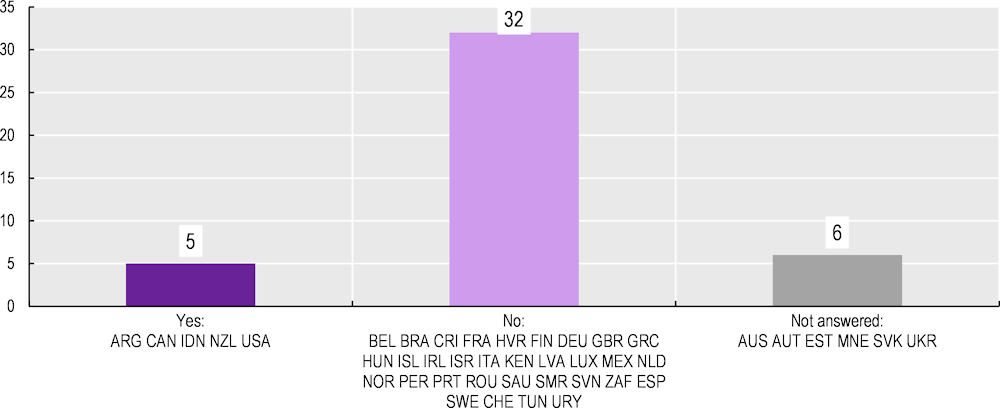

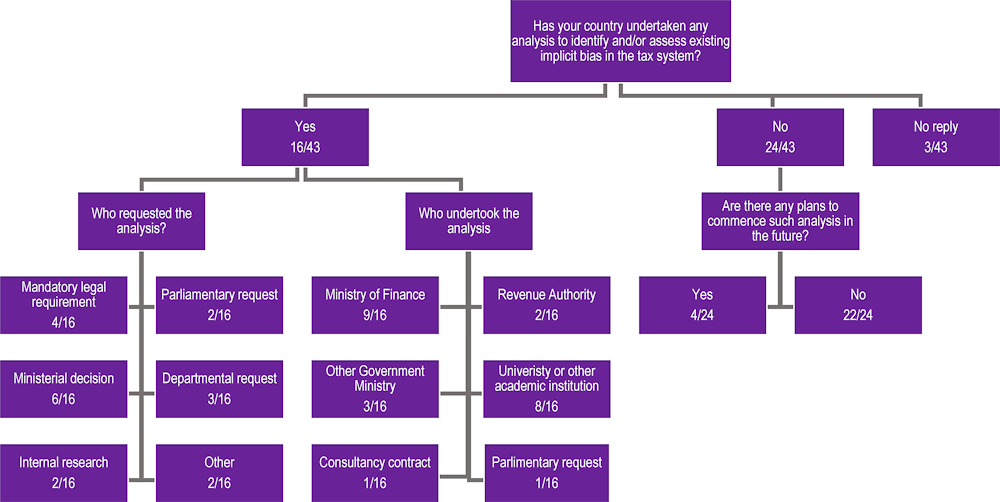

Almost two-thirds of the countries surveyed (25 out of 43 – 58%) indicated that they have not undertaken analysis to identify and/or assess existing implicit biases in their tax system. Among those countries, four (Germany, Indonesia, Montenegro and San Marino) plan to do so in the future. In addition, the United States also noted that studies on specific topics have touched on implicit bias (e.g. studies on tax rates for second earners and the earned income tax credit, including (Department of the Treasury, U.S., 2015[27]) (Lin and Tong, 2014[28]) (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2019[29])) although comprehensive examinations of implicit bias across the tax system are not available.

The limited number of countries that have assessed implicit bias may be explained by i) the fact that only half of countries consider that there is a risk of implicit bias in their tax system (23 out of 43), ii) the limited number of countries considering implicit bias questions in tax policy design (19 out of 43), iii) a general lack of guidance on how to consider or test for implicit bias in tax policy design.

The absence of guidance on how to consider or test for implicit bias in tax policy design is widespread as only five out of 43 countries surveyed reported having such a guidance (Austria, New Zealand, San Marino, Spain and Sweden). Some countries reported that they use general guidelines for assessing gender impact (Iceland), or have gender budgeting recommendations, albeit not targeted to tax policies (Ireland). In Spain, general guidance was implemented via a gender impact report in relation to the general budget, accompanied by practical implementation guidelines (Instituto de la Mujer, 2007[30]). This gender impact report has accompanied the state budgets since 2008. Since 2021, the report has been made using the “3-Rs Method” – the three "Rs" referring to "Reality", "Representation" and "Resources – Results”.

Table 3.3. Is there any guidance on how to consider/test for implicit bias in tax policy design?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

5 |

11.6% |

Austria; New Zealand; San Marino; Spain; Sweden |

|

No |

31 |

72.1% |

Argentina; Belgium; Brazil; Canada; Costa Rica; Croatia; Estonia; Finland; France; Hungary; Iceland; Indonesia; Iceland; Israel; Italy; Kenya; Latvia; Luxembourg; Mexico; Montenegro; Netherlands; Norway; Peru; Portugal; Romania; Slovenia; South Africa; Switzerland; Tunisia; Ukraine; United Kingdom |

Note: Seven countries (16.3%) did not reply to this question.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Among the countries surveyed, 16 out of 43 (37%) indicated that they have undertaken analysis to identify and/or assess existing implicit bias in the tax system.5 This analysis was either requested by a ministerial decision (six out of 16), the result of a mandatory legal requirement (four out of 16), or a departmental request (three out of 16). In Italy, this analysis followed a parliamentary request and also came from internal research. In Ireland, this analysis was undertaken at the initiative of an external research organisation, as in Uruguay where the University of the Republic initiated the analysis. In Belgium, Canada, Ireland and Italy, the request stemmed from several stakeholders.

Research into implicit bias in the tax system tends to focus on research within the personal income tax system, either due to family taxation or to the existence (or non-existence) of shared tax credits or tax allowances. For instance, in France, implicit bias risk was analysed at the request of the Parliament, leading to a 2014 report “On the Question of Women and the Tax System” (French National Assembly, 2014[31]), which examined the current tax treatment of couples, including the impacts of joint taxation and the family quotient, changes in family composition, the possibility of individualising taxation and the potential impact on women’s employment and promoting tax equity and the empowerment of women. Also, following an administrative circular issued by the French Prime Minister on 23 August 2012, the impact assessments that complement each legislative bill must include an analysis of the proposed measures’ impact on gender equality. Separately, personal tax credit or tax allowance (e.g. for child care), were identified as areas of risk of implicit tax biases by Argentina, who also note a risk for implicit bias given that the PIT exemption provided for financial income does not take into account the over-representation of men in the group of taxpayers reporting financial income. In the United States, although not routinely assessed, if a specific policy is expected to cause or worsen distortions, the gender impacts are considered during the policy development phase.

A few countries have also identified VAT systems as a potential source of bias, particularly in countries where VAT forms a large part of the tax base. Saudi Arabia indicated that VAT and tax treatment for micro-businesses could create similar risks, as more and more women are operating their own micro-businesses. Spain also identified VAT as an area at risk of implicit bias, together with PIT with regards to household taxation, progressivity and second income earners.

Among the 16 countries that undertook analysis to identify and/or assess existing implicit bias in their tax system, in almost half of the countries, universities or other academic institutions were involved in providing the analysis (Australia, Austria, Finland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Uruguay). In more than half of these 16 countries, the Ministry of Finance provided analysis (Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Iceland, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States). In Austria and Italy, other government ministries were also involved in providing analysis, and in Australia and Sweden, the revenue authorities were in charge of this analysis. In France, the Parliament undertook the analysis through a parliamentary inquiry. In the United States, scholars in academia and other policy analysts also undertake research in these areas. Box 3.1 provides a typology of the sources of implicit bias noted by the 22 countries that identified possible such biases in their tax systems.

In conclusion, analysis of gender implicit bias is not widespread among the countries surveyed. Analyses about this issue seem relatively rare and most countries that have not yet undertaken this type of analysis do not plan to do so in the near future, despite their importance in raising awareness of implicit gender bias. Support from universities and academic institutions can be useful in such analyses, as they already play an important role in many countries; as well as the role of the law in requesting or considering these analyses as a factor to take into account in the policy design.

Figure 3.3. Has your country undertaken any analysis to identify and/or assess existing implicit bias in the tax system?

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Box 3.1. Typology of implicit biases identified among the countries surveyed

Among the countries surveyed, 23 out of 43 (53%) identified possible implicit biases in their tax systems. This box groups these implicit biases to form a non-exhaustive typology.

Implicit biases due to differences in income levels between men and women

On average, men earn higher incomes than women. Therefore, if the PIT puts a high burden on low-income earners or is not progressive enough, there is a risk of bias in favour of men (noted by Argentina, Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, and Norway). Similarly, if VAT places a greater relative burden on individuals with low disposable income, there is risk of bias that disadvantages women (noted by Argentina, Austria and Kenya). Conversely, highly progressive tax systems, as well as refundable tax credits for lower-income earners contribute to reducing gender inequities (e.g. in the United States).

Implicit biases due to differences in nature of income between men and women

On average, men earn more capital income than women, so preferential taxation of capital can create a risk of bias in favour of men (noted by Argentina, Austria, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom).

Implicit biases due to fiscal unit consideration

Taxing households rather than individuals can create implicit biases. Joint filing taxation puts a high tax burden on the second earner within a household, the second earner being more likely to be a woman. Even if joint filing is optional, risks of bias against second earners still exist (noted by Belgium, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Luxembourg, Spain and the United States). Belgium, Canada, Iceland, the Netherlands and Tunisia reported that even when individual filing applies, tax credits or tax allowances are often designed at the household level. Households optimise the person who will benefit from the tax relief to pay fewer taxes. These tax reliefs are often more profitable when they apply to the highest income within the household, which could be detrimental for women who earn on average less than men (the Netherlands).

Implicit biases due to differences in consumption between men and women

Essential products, such as food, medicines and educational services, often benefit from preferential taxation under VAT or excise duties, which can create a risk of bias due to the different consumption profile between genders (noted by Brazil and Mexico). However, individual consumption patterns are not necessarily representative of the gender impact of consumption taxes, as the individual may be purchasing goods on behalf of the family, and the impacts of the taxes on intra-household consumption and income decisions are unclear (as described in a Finnish study on the effects of tax changes on gender between 1993 and 2012 (Riihelä, 2015[32]) and (International Development Research Centre, 2010[33])).

Implicit biases due to differences in social roles between men and women

Women tend to be more involved in childcare than men, leading to some tax provisions benefitting women more in practice For example, in Mexico, some PIT exemptions (alimony, income received for financing the payments to childcare centres and social security benefits related to maternity) benefit women more than men.

Source: Tax and Gender Survey, OECD 2021

3.4. Policy development process and gender budgeting

Understanding and improving the gender equality of the tax system relies on policy development processes which assess the impact of taxes on gender as a core element of policy design, including through gender budgeting. This section presents information on whether and how the impact of taxes on gender fits within the tax policy process in the respondent countries. This includes the process of developing and introducing new tax policies or tax expenditures, or changes to tax rates, bases, credits, allowances, or other tax expenditures.

3.4.1. Analysis of tax and gender under the scope of gender budgeting

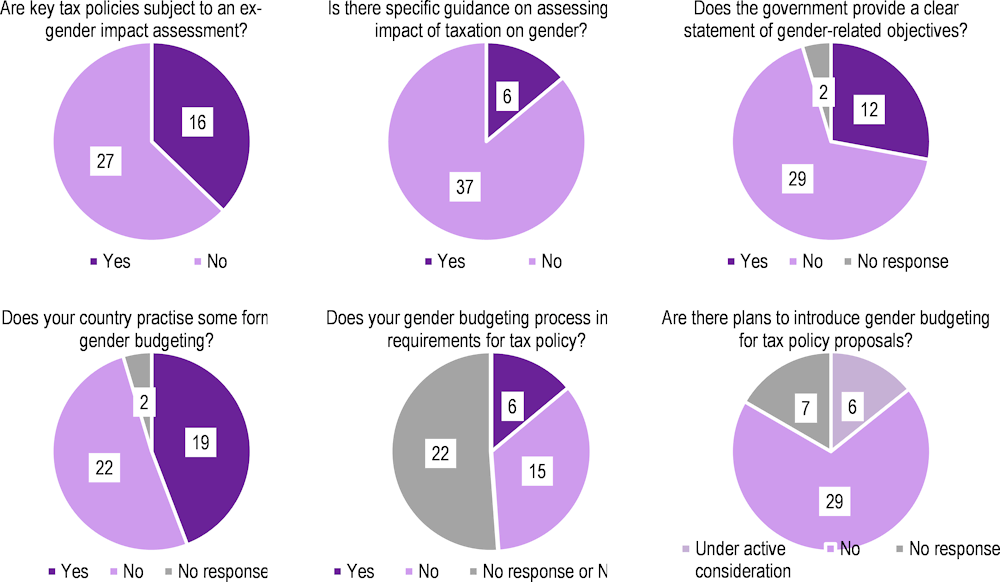

Sixteen out of 43 (37%) respondent countries indicated that key tax policies and programs proposed for inclusion in the budget or other legislative processes are subject to an ex-ante gender impact assessment. Of these, six countries have had the Ministry of Finance or the budget office issuing circulars or other directives that provide specific guidance on assessing the impact of taxation on gender (Argentina, Austria, Finland, Indonesia, Italy and Sweden).

Almost 50% of respondent countries have indicated using sex-disaggregated statistics and data when available across key policies and programs to inform tax policy decisions. However, 29 out of the 43 countries indicated their government does not provide a clear statement of gender-related objectives in relation to tax policy (i.e. a gender budget statement or gender responsive budget legislation). In this regard, work is in progress in France between the Directorate General of the Treasury and the Directorate General of Social Cohesion and four ministries (Agriculture and Food, Culture, Territorial Cohesion, and Solidarity and Health) to improve a horizontal policy document on gender equality policy. They are focusing on three areas: (i) analysing the budgetary expenditures to identify the impact on equality, (ii) developing gender equality performance indicators (when relevant and where data are available) and integrating them into a budget performance model, (iii) conducting awareness-raising and training actions to take into account the equality axis in expenditure. A pilot project at the end of 2019 confirmed the objective of implementing a budget gender equality study (le Budget intégrant l’égalité (BIE)) as part of budgetary procedures and in the evaluation of expenditure performance.

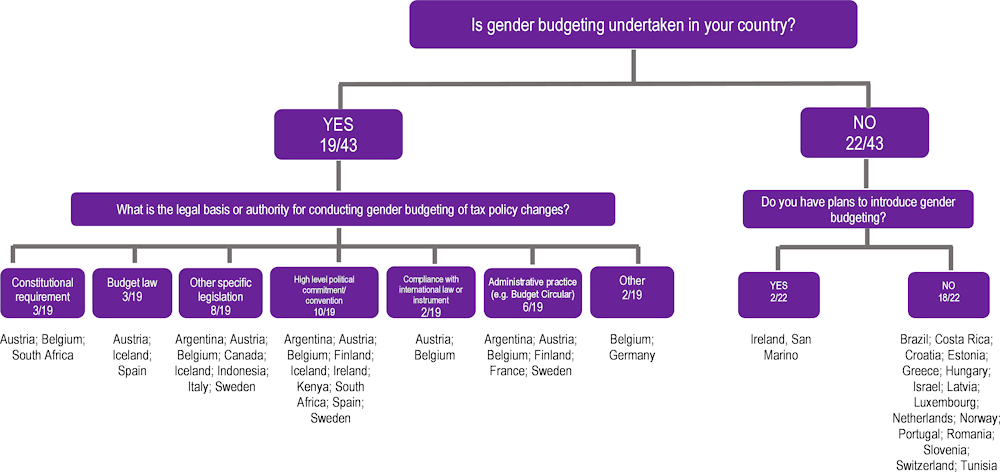

Nineteen out of 43 countries surveyed (i.e. 44%) practise some form of gender budgeting, although only five countries indicated that there was a specific requirement for gender budgeting in tax policy analysis (Table 3.4). Spain noted that Ministerial Departments send a report to the Secretary of State for Budgets and Expenditures analysing the gender impact of their spending programs. These reports form the basis for the formulation by the Secretary of State of the gender impact report (described in the section on implicit bias). Some countries that do not have specific gender budgeting requirements do consider the gender impact of all policies in other ways, including the impact of tax changes. For instance, Australia’s government does not provide a statement specifically in relation to tax policy, but more broadly, in May 2021, as part of the 2021-22 budget, the government released a Women’s Budget Statement (Government of Australia, 2021[34]). This statement includes analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on women, as well as an overview of key statistics relating to women’s safety, economic security, and health and wellbeing. It details relevant budget initiatives, analysis, trends and existing government approaches. Luxembourg noted that every draft law and/or draft regulation must be accompanied by an impact assessment, in which one required category is gender neutrality.

Table 3.4. Does your country practise some form of gender budgeting?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

19 |

44.2% |

Argentina; Austria; Belgium; Canada; Finland; France; Germany; Iceland; Indonesia; Ireland; Italy; Kenya; Mexico; Montenegro; Peru; South Africa; Spain; Sweden; Ukraine |

|

No |

22 |

51.1% |

Australia; Brazil; Costa Rica; Croatia; Estonia; Greece; Hungary; Israel; Latvia; Luxembourg; Netherlands, New Zealand; Norway; Portugal; Romania; San Marino; Saudi Arabia; Slovenia; Switzerland; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States |

Note: Countries in bold reported that their gender budgeting processes have specific requirements for tax policy.

Two countries (4.7%) did not reply to this question.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Figure 3.4. Use and legal basis or authority of gender budgeting of tax policy changes

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Among the countries that provided an answer regarding the legal basis for conducting gender budgeting of tax policy changes, Austria, Belgium and South Africa indicated that a constitutional requirement was the basis for this analysis. Austria indicated that men and women have equal rights under the Austrian Constitution. The state therefore promotes the actual implementation of equal rights for women and men and work towards the elimination of existing disadvantages. Belgium stated its introduction of a constitutional requirement in 2002. Despite some legal measures promoting gender equality since the 1980s, it was the first time the principle of equality between men and women had been explicitly affirmed (Article 10) (European Parliament, 2015[35]). In 1996, in South Africa, a commission of enquiry was established to ensure that the tax system supports the reduction of inequality and has no inherent bias against a specific group. Some countries do not consider that their constitution establishes a legal basis for conducting gender budgeting of tax policy changes but do consider that it helps to ensure gender equality. For instance, Kenya indicated that its Constitution recognises the rights of everyone and has entrenched Gender Equality as one of the key principle.

Eight other countries (Argentina,6 Austria, Belgium, Canada, Iceland, Italy, Spain and Sweden) note that the basis for gender budgeting exists in their budget law or other legal frameworks. For example:

Since 2013, the consideration of gender distortions in Austria has been embodied in the Budget Law, which ensures the implementation of the equality objectives in tax policy measures. Since that year, gender budgeting must be implemented at the federal level and the de facto equality between women and men must be considered in all stages of administrative action, from the formulation of objectives to their implementation and evaluation.

Belgium reported having implemented in 2013 a ‘gender test’ (Government of Belgium, 2013[36]) a regulatory impact analysis which assesses the impact of regulatory proposals on women and men via a series of questions for policymakers.

Canada enacted the Canada Gender Budgeting Act in 2018, enshrining the government’s commitment to budget decision-making that takes into consideration the impacts of policies on all Canadians. These priorities range from addressing the gender wage gap to promoting more equal parenting roles and are associated with a set of goals and indicators to benchmark progress in achieving gender equality and diversity.

In Germany, “gender mainstreaming” is included as a universal guiding principle in the Joint Rules of Procedure of the Federal Ministries, which state: ‘Equality between men and women is a consistent guiding principle and should be promoted by all political, legislative and administrative actions of the Federal Ministries in their respective areas (gender mainstreaming)’ (Government of Germany, 2020[37]).

In Iceland, gender mainstreaming in policy making is required by the Act on Equal Status and Equal Rights Irrespective of Gender, also known as the “Gender Equality Act” (Government of Iceland, 2021[38]). The aim of this Act is to prevent discrimination on the basis of gender and to maintain equal status and equal opportunities for women and men, thus promoting gender equality in all spheres of society.

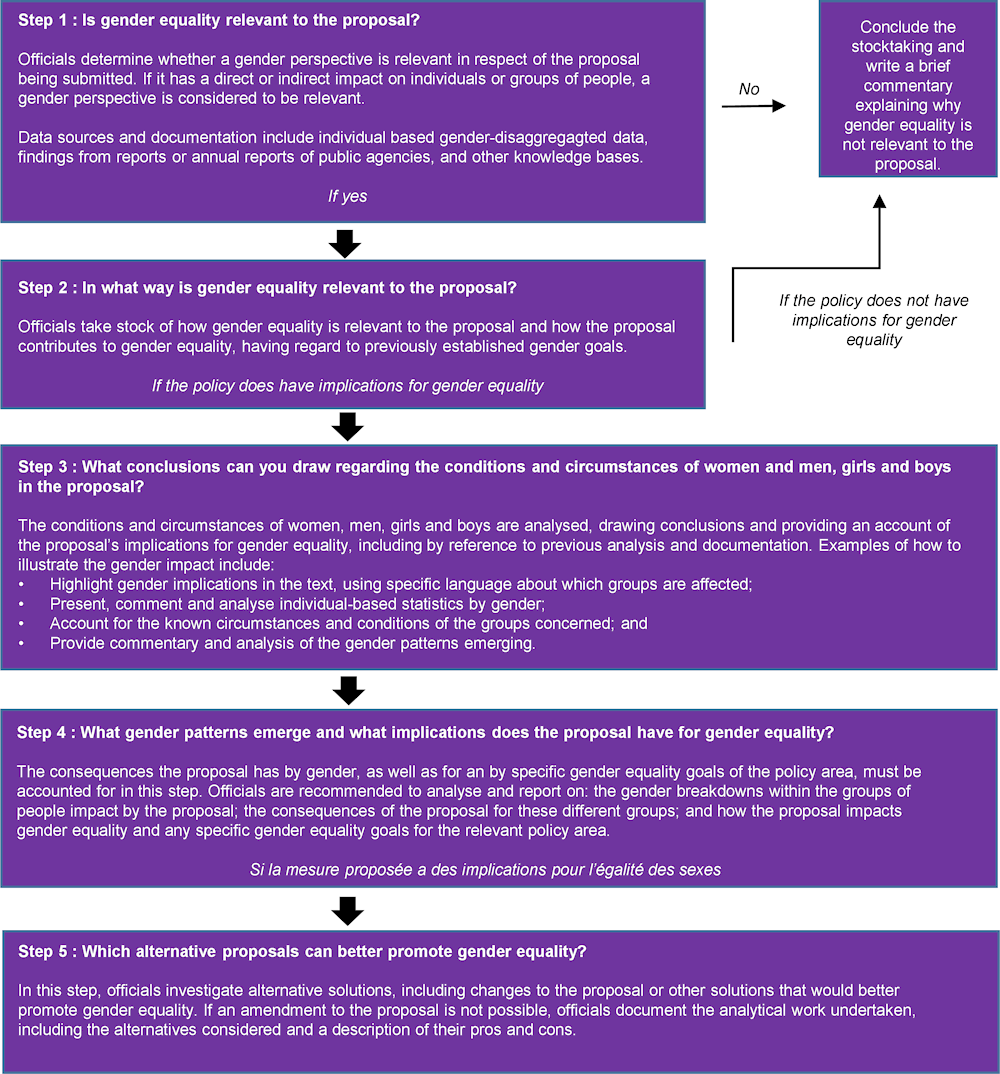

A summary of Sweden’s gender budgeting mainstreaming tool is set out in Box 3.2.

Box 3.2. Sweden’s BUDGe for Gender Equality

BUDGe is a Swedish budgeting tool, in place since the early 2000s, that brings gender equality into the budget development process. It is an analytical tool which aims to help officials to determine whether a gender perspective is relevant for budget proposals, to conduct a gender analysis where so, and to account for the proposal’s impact on gender equality.

The tool was developed within a broader government framework providing methods and models for gender mainstreaming. It was developed for the core activities of the Government Offices but has since been adapted to suit public agencies, municipalities and other organisations. It has five steps, as shown in the schematic below.

Austria and Belgium also indicated that compliance with international law or instruments constitute a legal basis or authority for conducting gender budgeting of tax policy changes.

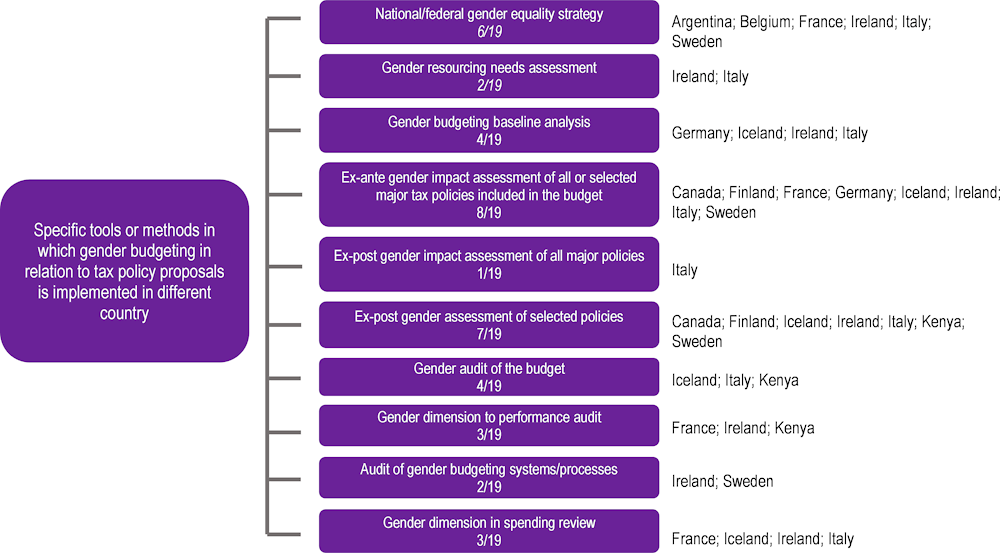

The following figure shows the specific tools integrated by the 19 countries that include a gender budgeting process.

Figure 3.5. Specific tools or methods in which gender budgeting in relation to tax policy proposals

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Planned implementation of gender budgeting in relation to tax proposals

Two of the 22 countries that do not currently undertake gender budgeting indicated that official plans to introduce gender budgeting for tax policy proposals in the future are under consideration (Ireland and San Marino). In Ireland, in line with the OECD recommendations on an Equality Budget (OECD, 2019[39]), the country is considering how best to implement a parallel equality budgeting progress in respect to taxation, and set out an equality budgeting agenda of its current government programme (Government of Ireland, 2021[40]). In San Marino, the gender impact of tax measures is assessed when the legislative text is first forwarded to the San Marino body on Equal Opportunities, a delegation generally assigned to the Ministry of Health. San Marino are actively considering the introduction of gender budgeting in the near future.

In the United States, the current Administration established a working group across government agencies to advance the goal of expanding and refining Federal government data sets, including tax return data, for the purpose of measuring and promoting equity, including gender equity.

Figure 3.6. Summary of policy development process and gender budgeting

3.5. Tax compliance and administration

Tax compliance and administration can be analysed through a gender perspective. Understanding the compliance patterns of men and women through data collection, or undertaking a reflection on the gender implications of tax administration processes with a view to adapting some of them; can be useful to improve the tax system in light of the objective of gender equality and to address some of the biases observed. This section describes the country practices in relation to tax compliance and administration and makes a link with other existing studies and initiatives.

3.5.1. Overview of country practices in tax compliance and administration

Analysis of gender implications of tax administration or compliance

The vast majority of the countries surveyed (34 out of 43, i.e. 79%) indicated that they did not undertake any analysis on the gender implications of tax administration or compliance.

Table 3.5. Has your country undertaken any analysis on the gender implications of tax administration and compliance?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

3 |

6.9% |

Indonesia; New Zealand; Sweden |

|

No |

34 |

79.1% |

Argentina; Belgium; Brazil; Canada; Costa Rica; Croatia; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Kenya; Latvia; Luxembourg; Mexico; Netherlands; Norway; Peru; Portugal; Romania; San Marino; Saudi Arabia; Slovenia; South Africa; Spain; Switzerland; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States; Uruguay |

Note: Six countries (13.9%) did not reply to this question.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Only three countries (7% of all respondents) indicated that they do undertake analysis on the gender implications of tax administration or compliance – Indonesia, New Zealand and Sweden:

In 2006, Sweden’s tax agency investigated the relationship between taxation and gender equality policy objectives, publishing a report in 2007 (Swedish Tax Agency, 2007[41]). The report describes policy measures that have an impact on gender equality, including joint taxation (Sweden adopted individual-based taxation, which was considered to have an income equalising effect), tax relief for domestic services (80% of these deductions were claimed by men), gross payroll deduction in exchange for tax-free benefit (more profitable to high earners, that are typically men). On compliance, it shows that since men are more likely to engage in business activities, they make more deductions from their earned income and declare higher capital gains than women, and thus make more errors in their declarations, and are therefore likely to be subject to tax audits, adjustments and penalties. The report concludes that the most effective measures are to simplify tax rules and to require gender-based analysis of these rules.

A report from New Zealand’s University of Wellington (González Cabral, Gemmell and Alinaghi, 2019[42]) examined patterns of non-compliance and under-reporting of income earned by self-employed individuals, indicating that there are gender differences in levels of non-compliance, and suggesting that males underreport more than females, which was observed consistently across income and expenditure variables.

Collection of gender-disaggregated data on tax compliance

The majority of countries surveyed do not collect gender-disaggregated data on tax compliance (22 out of 43, i.e. 51%). Eight countries (19%) indicated that they are “not aware” of whether such data are collected or not. Only seven countries (16%) responded that they do collect gender-disaggregated data: Argentina, Canada, France, Mexico, San Marino, Sweden and the United States.

Figure 3.7. Does your country collect gender-disaggregated data on tax compliance?

In 2020, Sweden published a report on tax reporting error (Swedish Tax Agency, 2021[43]), supplementing a report on the size and evolution of the tax gap and that contains gender-specific data on reporting error by types of taxes, based on the Swedish Tax Agency’s statistical database of tax return data. The report shows, for instance, that between 2018 and 2020, the tax error resulting from incorrect deductions applied to employment income in tax returns is estimated at SEK 2.9 billion, of which women account for SEK 1.0 billion and men for SEK 1.9 billion.

Canada also collects data on the number of returns by filing deadline and by gender, as well as on late-filing penalties assessed by gender. The data on late-filing show that the total and average penalties paid by men in 2017 are significantly higher than for women, whereas there are in total more tax returns submitted by women than men overall.

In Mexico, gender-disaggregated data is used to analyse the impact of the tax structure on each gender.

In the United States, data on gender and tax compliance are available but gender-specific compliance has not been assessed, although it may be included as a control variable in regression analyses.

Adjustments to tax administration processes in response to a specific gender’s needs

The vast majority of countries surveyed reported that they have not made any adjustments to tax administration processes to respond to the needs of a specific gender (33 out of 43, i.e. 77%). Only four countries (9%) indicated that they have done so – Argentina, France, Indonesia and Israel. In Argentina, the Federal Administration of Public Revenues (AFIP) launched the Protocol for the Improvement of Comprehensive Attention to Citizens with an inclusive, federal and gender-based approach. This initiative promotes several channels to guarantee the inclusion of vulnerable sectors of the population. This new tool incorporates a gender perspective and cultural diversity. France stated that following the 2019 introduction of a withholding tax for personal income tax purposes, it is possible for a married or civil-union couple to opt for individualised rates rather than the household rate – noting that this option may be appropriate when there is a significant difference in income within the couple.

Table 3.6. Has your country made adjustments to tax administration processes to respond to the needs of a specific gender?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

4 |

9.3% |

Argentina; France; Indonesia; Israel |

|

No |

33 |

76.7% |

Belgium; Brazil; Canada; Costa Rica; Croatia; Finland; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland; Italy; Kenya; Latvia; Luxembourg; Mexico; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Portugal; Romania; San Marino; Saudi Arabia; Slovenia; South Africa; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States; Uruguay |

Note: Six countries (13.9%) did not reply to this question

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

Gender-targeted taxpayer awareness campaigns

The vast majority of respondents reported that they have not designed any gender targeted taxpayer education or awareness campaigns (32 out of 43, i.e. 74%). In many of these countries, this may be due to the fact that awareness campaigns are typically directed at individual taxpayers more generally, although not specifically targeted at one gender, for example in Tunisia.

Five countries (12%) indicated that they have done so, although in most cases these campaigns are gender-neutral in their own right but the underlying service or programme is primarily used by one gender (Argentina, Canada, Indonesia, New Zealand and the United States). For example, Canada has put in place a programme to help modest-income individuals file their tax returns and access tax benefits (the “Community Volunteer Income Tax Program”), which, even if not targeted at women in particular, has been used by women in difficult situations. New Zealand also implemented an awareness campaign for a tax credit (“Best Start”) directed at families that have a new-born baby (Government of New Zealand, 2021[44]).

Figure 3.8. Has your country-designed gender targeted taxpayer education/awareness campaigns?

3.5.2. General observations on gender equity in tax compliance and administration

A clear trend is observed among the countries responding to the survey: the overwhelming majority indicated that they have not undertaken analyses on the gender impact of tax administration and compliance measures, and that they have not adjusted their tax administration processes in response to the needs of a specific gender, nor have they launched taxpayer awareness campaigns directed at a particular gender. However, the small number of countries that have implemented such initiatives and reported on them through the questionnaire have provided interesting data on their findings and analyses.

The answers provided by countries could reflect the lack of gender disaggregated data on tax compliance and administration, which appears to be confirmed by a vast majority of respondents – with 70% of the respondents indicating that they do not collect such data or are not aware if they do, which means in any case that they do not currently have access to it. As for other aspects of the tax and gender work, the lack of such data may be an obstacle to a deeper analysis. The answers could also mean that the analysis of tax compliance and administration by gender type has not yet emerged as an area of priority for many countries.

Going forward, further analysis of tax administration and compliance measures and their impact on gender could draw on additional and external sources to complement the information provided by countries. The activities and outcomes of the OECD Forum on Tax Administration’s Gender Balance Network may be useful in this regard (see Box 3). Several studies and reports suggest that women have higher levels of tax compliance than men globally (OECD, 2019[45]) (D'Attoma, Malézieux, Volintiru, 2020[46]) (Kangave, Sebaggala, Waiswa, 2021[47]),

Box 3.3. The OECD Forum on Tax Administration’s Gender Balance Network

The OECD’s Forum on Tax Administration (FTA) brings together Commissioners from over 53 advanced and emerging tax administrations. It has a broad work programme which looks to increase fairness and effectiveness of tax administration. Commissioners recognised that there was underrepresentation of women in senior executive roles in many FTA countries and female staff remain proportionally underrepresented in executive positions (see Fig. 9.9. of (OECD, 2021[48])).

In 2019, FTA Commissioners launched the Gender Balance Network, which aims to be a catalyst for positive institutional change to improve gender balance in tax administration leadership positions by developing mentoring and secondment programmes as well as exploring best practices across FTA member jurisdictions including through the study Advancing Gender Balance (OECD, 2020[49]), and through reflections on the impact of COVID-19 on Gender Balance (OECD, 2020[50]).

Source: OECD Forum on Tax Administration.

3.6. Data on gender and taxation available for use in analysis

Gender differentiated data and information is critical for policymaking as it facilitates the assessment and development of appropriate evidence-based responses and corrective actions. For governments to include the impact of taxes on gender as key dimensions in their tax policy, access to quality gender-disaggregated micro-data is needed.

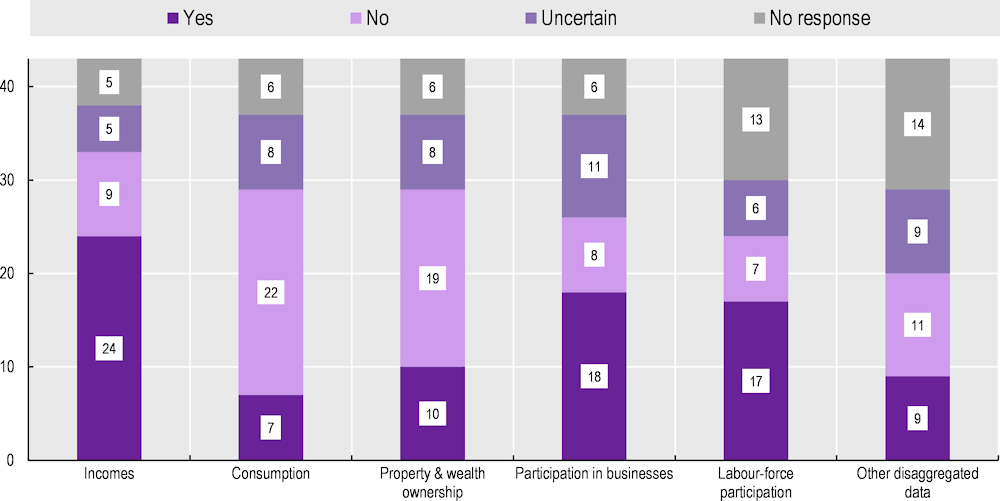

This section outlays the survey findings on the availability and quality of gender-differentiated data. The survey shows a mixed picture in terms of data availability. While most countries do have at least some disaggregated data available, availability of detailed micro-data on wealth, assets and property ownership and, micro-data on male and female consumption appears to be a particular challenge for many countries.

Twenty-five of the 43 countries, representing 58% of the respondents, had disaggregated data available for policy analysis. This data was available across various taxes, such as PIT, SSCs, VAT/GST, capital or property taxes. In Spain, gender-disaggregated data and statistics are available to the tax authority in relation to PIT (Ministerio de Hacienda, n.d.[51]), wealth taxes (Ministerio de Hacienda, n.d.[52]) (Agencia Tributaria, 2018[53]) and SSCs. In some countries, such as Croatia, gender disaggregated data is available in the main registry of taxpayers of the tax administration. In Ireland, gender is a recorded field on revenue administration systems and is used as a basis to report on tax returns for different genders (Acheson and Collins, 2020[54]). In Australia, gender disaggregated data is retrievable from the individual’s income, including private pension information. In numerous instances, data on gender could not be accessed from Corporate Income Taxes (CIT) and VAT/GST owing to the challenge of linking the large entities to individual owners. For few countries, for instance in Luxembourg, gender disaggregated data is not directly available. Some countries reported inferencing such data from the titles such as (Mr., Ms.). However, this form of referencing poses a limitation, as such titles do not directly map to a specific gender.

Table 3.7. Is gender-disaggregated data available from tax returns for use in policy analysis?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

25 |

58.1% |

Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium; Brazil; Canada; Finland; France; Greece; Hungary ; Iceland; Israel; Italy; Luxembourg; Mexico; Netherlands; Norway; San Marino; Slovenia; South Africa; Spain; Sweden; United Kingdom; United States; Uruguay |

|

No |

12 |

27.9% |

Costa Rica; Germany; Indonesia; Ireland; Kenya; Latvia; Peru; Portugal ; Romania; Saudi Arabia; Switzerland; Tunisia |

|

Other |

2 |

4.7% |

Croatia; New Zealand |

Note: In the United States, although gender information is not directly collected by tax returns, taxpayer identification numbers can be linked to other administrative data to draw conclusions on gender and income levels. Four countries (9.3%) did not reply to this question.

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.

The level of data disaggregation for 16 countries is at the individual level or individual micro-data. This is attributed to the fact that every form of data (from PIT, SSCs, tax registries) can be linked to the individual taxpayer allowing for the analysis of the tax framework across a range of dimensions, such as age, economic sectors, gender and income level.

For 14 of the 25 countries that have gender-disaggregated data, uptake of tax incentives and benefits can be measured on a gender basis in the areas of taxation where the data was available.

3.6.1. Access to gender-disaggregated non-tax data for policy analysis7

From the results obtained, countries had varying access to different forms of gender-disaggregated non-tax data. However, countries’ data availability clustered in some forms of data. For instance, information on male and female income was markedly more accessible than that on consumption or property and wealth ownership. While in no area was there uniform access to disaggregated data, these findings highlight the areas where differentiated data appears to be especially challenging to access, which are discussed further below. The main sources of the non-tax data were indicated to be the tax registries and specific government surveys.

Detailed micro-data on male and female incomes is available to 24 of the 43 respondent countries (56%), both separately and within households. Countries indicated a number of sources from which this detailed information is derived:

In Sweden, this data is accessible from tax data;

In Australia, household surveys such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Income and Housing (SIH), ABS Census of population of Housing and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey provide detailed information on household income;

In Luxembourg, even though this data is accessible, it is not directly available and, as such, is derived from inferencing;

In the United States, detailed microdata on male and female incomes, as well as participation in businesses, is available from the Current Population Survey.

In Spain, the data is available from the Survey on Living Conditions (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020[55]).

Figure 3.9. Do you have access to the following gender disaggregated non-tax data available for policy analysis?

In contrast, only six countries have access to detailed micro-data on male and female consumption. Most of the available data is from surveys, which collect information on household expenditure providing consumption by household but not on an individual level/individual microdata.

Only ten of the 43 countries have access to detailed microdata on male and female property and wealth ownership. It seems that such data is unavailable at microdata level but is present on household level.

Eighteen of the 43 countries have access to information on men’s and women’s participation in business. This data is available from a range of sources, including tax registries, labour force surveys and household surveys. In Australia, information from the ABS Labour Force Survey provides a detailed breakdown of labour force participation, which is available by industry sector and allows the identification of self-employed individuals. Additionally, household surveys allow identification of income from unincorporated businesses providing data on individual’s participation in business. Spain also has access to data on women’s employment and presence on companies’ boards of directors.

Seventeen of the 43 countries have access to information on male and female labour-force participation (hours worked, wages, unemployment, sectoral involvement) representing 40% of the total respondents. For instance, Spain noted that it has access to data related to the labour market as well as on education and culture, health, security and justice, social analysis and electoral processes.

3.7. Usability of gender-disaggregated data in practice

Even where data is available, there are concerns about its usability (Table 3.8). Only nine countries confirmed the data was fit for purpose, a further 16 indicated the data was useable with caveats or extrapolations, while five countries indicated while data was available; it was not fit for purpose.

Australia stated that the data listed is available for use within the Treasury for policy development and that much of this data is available to approved researchers in unit record data, or summarised in freely available publications.

Table 3.8. How usable is the available gender-disaggregated data in practice?

|

Answer |

Number |

Share |

Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Able to be used with caveats |

11 |

25.6% |

Austria; Finland; France; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Netherlands; New Zealand; Saudi Arabia; Sweden; United Kingdom |

|

Able to be used with caveats, extrapolations |

1 |

2.3% |

Belgium |

|

Extrapolations |

5 |

11.6% |

Croatia; Indonesia; Peru; Romania; San Marino |

|

Fit for purpose |

9 |

20.9% |

Canada; Iceland; Israel; Kenya; Mexico; Norway; South Africa, Spain; United States |

|

Not fit for purpose |

5 |

11.6% |

Brazil; Germany; Greece, Luxembourg; Slovenia |

Note: Twelve countries (28%) did not reply to this question.

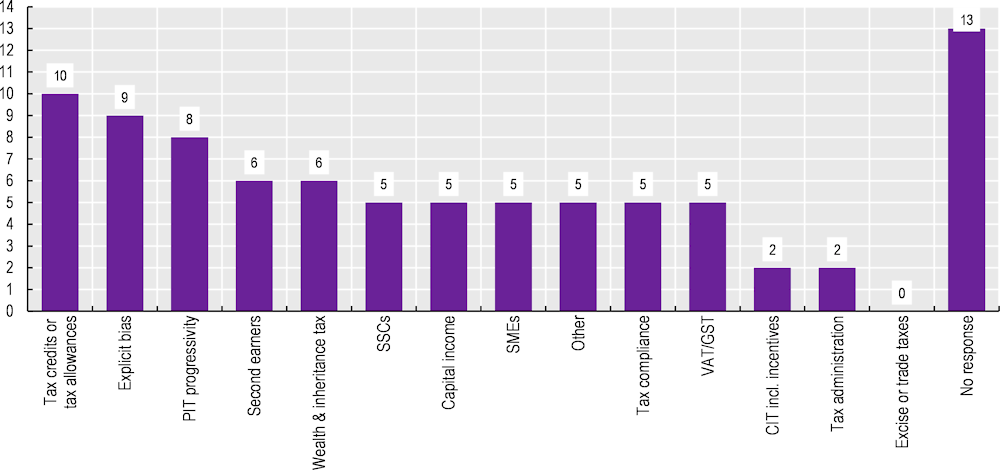

Source: OECD Tax & Gender Stocktaking Questionnaire 2021.