This section presents a range of options for embedding RIA within the rule-making process in Mauritius, based upon the strengths and challenges identified in the previous section. To do so, it also draws on lessons learned from RIA implementation in a range of countries and an initial benchmarking of RIA-related best practices and guidance material from various relevant jurisdictions.

Establishing Regulatory Impact Assessment in Mauritius

3. Preliminary options for establishing a RIA framework in Mauritius

Abstract

Key messages

There is a case for the Government of Mauritius to build upon current momentum and consider how it can ensure widespread political and stakeholder commitment for implementing a RIA framework.

Ongoing engagement with external stakeholders is a crucial factor, including publicity of the RIA process and adequate consultation on RIA drafts, which has been shown to enhance the quality of both the debate and the final RIA document.

RIA should not be considered in isolation. It needs to be fully integrated with other regulatory management tools throughout the policy cycle, and a functioning legislation planning system is needed.

Evidence shows that institutionalising regulatory oversight is crucial for effective RIA, as is a proportionate and well-timed approach. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, locating oversight functions close to the centre of government can contribute to their effectiveness. Although regulatory oversight functions do not need to be carried out by a single body, effective co-ordination between these functions is crucial for success.

Existing constraints, notably in terms of capacity and expertise, suggest that a gradual approach to RIA implementation would be better adapted to the current situation in Mauritius.

Providing adequate training to officials on RIA processes and methodologies is crucial; this report describes options for rolling out training and promoting widespread RIA awareness. It also presents international examples of how administrations promote accountability for RIA.

It is crucial to select a robust RIA methodology that can be implemented effectively within the administrative context and incentivises officials to integrate RIA into the early stages of the policy process for the formulation of new regulatory proposals. This methodology should remain simple and flexible, particularly at the start, and incorporate broad-based public consultation.

There is scope for Mauritius to use RIA to explore the use of alternatives to regulation (which tends to appear as the only possible course of action) in various policy areas.

It is essential that officials in charge of RIA identify all groups of stakeholders who would be impacted and how. They should consider all possible direct and indirect impacts to enable a meaningful comparison of alternative options that could in principle address the problem identified.

This section focuses on presenting the different options for embedding RIA within the rule-making process in Mauritius, based upon the strengths and challenges identified in the previous section. To do so, it also draws on lessons learned from RIA implementation in a range of countries and an initial benchmarking of RIA-related best practices and guidance material from various relevant jurisdictions.

As in the previous section, the reference framework for this section consists of the OECD’s RIA Best Practice Principles (see Annex B), as well as Principle No. 4 of the 2012 OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (see Annex A). This section follows the same basic structure of the RIA Best Practice Principles.

Political commitment and buy-in for RIA – how to ensure support?

In Section 2, it was noted that there is great interest and political momentum for developing a RIA framework in Mauritius. There is a case for the Government to build upon this momentum and consider how it can ensure widespread political commitment for implementing a new RIA framework within the administration and from key external stakeholders.

Ongoing engagement with external stakeholders is a crucial factor, including publicity of the RIA process and adequate consultation of RIA drafts, which has been shown to increase the quality of the debate and the final RIA document. In addition buy-in from external stakeholders creates demand for good RIA and provides mechanisms making policy makers and civil servants more accountable for their decisions to these stakeholders.

Developing a whole-of-government policy

Political commitment has always been an important factor for RIA to be successfully integrated into regulatory policy. International examples of countries implementing RIA have highlighted that a number of factors can militate against its use, including bureaucratic inertia, political need for speed, an appetite to adopt certain politically sensitive proposals without much scrutiny, etc. OECD best practice points to a number of key methods that governments can use to show their commitment towards RIA in the long run, although these are dependent on the nature of a country’s system of governance.

The vast majority of OECD countries have adopted an explicit regulatory policy promoting government-wide regulatory reform or regulatory quality and established dedicated bodies to support the implementation of regulatory policy. Almost all OECD countries have formal requirements for the production of RIA for the development of both primary laws and subordinate regulations. They also generally have a specific minister or high-level official who is accountable for promoting government-wide progress on regulatory reform.

There are a variety of examples of countries that have implemented RIA based on a law (Korea, Mexico); a Prime Ministerial decree or guidelines of the Prime Minister (Australia, Austria, Czech Republic, France, Italy, Netherlands); or a cabinet directive or cabinet decision (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, United Kingdom, Portugal) (OECD, 2004[1]). According to the World Bank, evidence from case studies in developing countries suggest that “there may be merit in capitalizing on the strong political commitment often enjoyed at the early stages of RIA reform by seeking a formal/legal integration of RIA in the policy-making process…they would send a credible signal and navigation point for relevant stakeholders”. (Ladegaard, Lundkvist and Kamkhaji, 2018[2]). However, the implementation of such an approach also depends on the historical background administrative culture and commitment of high-level officials of a given country.

The introduction of RIA also provides Governments with the opportunity to consider different types of outreach activities to clearly communicate the goals of RIA, both internally (ministries and agencies) and externally (stakeholders like Parliament, universities, think tanks, mass media…) and present it as a pivotal tool for enhancing regulatory quality. Importantly, regulatory policy could also help to link RIA more clearly with the Government’s policy overall priorities, thereby reinforcing its relevance to government officials and stakeholders.

Key options for Mauritius to consider for developing a whole-of-government policy include:

Which institutional setups have worked previously to drive progress in other policy areas; e.g. setting up an inter-ministerial committee, comprising ministers from key ministries to set the strategic guidelines for RIA implementation.

How Mauritius could establish a mandate on ministries to carry out RIA including using primary legislation or, alternatively, implementing RIA through administrative rules.

What methods could be applied to clearly communicate the goals of RIA, both internally and to external stakeholders. Enhancing stakeholder engagement to secure support for RIA.

Securing stakeholder support for RIA is essential to create consensus on a given RIA policy and secure support by key constituencies over time. In most of the countries that have successfully introduced RIA, the centre-of-government has been instrumental in convincing government officials of the need to draft high quality RIAs also by creating expectations among, and a constant dialogue with, external stakeholders. Governments should view stakeholders as beneficiaries of their policies and an integral part of regulatory policy. Stakeholder engagement, and regulatory policy more generally, should be predicated on the capacity of citizens to articulate problems and offer possible solutions.

Accordingly, the draft OECD Best Practice Principles on Stakeholder Engagement in Regulatory Policy (see Annex E) recommends close co-operation with stakeholders when defining the problem to be solved by a new policy proposal, setting its objectives, identifying various alternative solutions (including non-regulatory ones) and assessing potential impacts of these alternatives, as well as when designing potential implementation mechanisms.

Countries use a wide spectrum of instruments and tools to engage stakeholders in regulatory policy. There are ample examples of attempts to involve stakeholders both in the development of new laws and regulations and the review of regulatory stock, but there is less evidence of attempts to engage stakeholders in regulatory delivery. Box 3.1 provides some strong examples of stakeholder engagement practices from Canada, Mexico and the European Commission, each of whom has a clear stakeholder engagement policy and engages with stakeholders throughout the regulatory cycle using a variety of methods.

As discussed in Section 2, Mauritius possesses a culture of consensus, consultation and collaboration across ministries and agencies. Ministries tend to conduct consultations on new legislative measures at a relatively early stage of the process, giving stakeholders the opportunity to participate. However, the informal nature of this consultation leads to a risk of regulatory capture as the government may habitually consult with similar stakeholder groups during the policy making process. There also seems to be no standardised practice on how to conduct regulatory consultation, including its length, scope, timing, and underlying procedures.

There are a number of options for Mauritius should consider for how it can build upon its long-established experience of stakeholder consultation to drive transparency in the legislative process, including:

How to ensure that all stakeholders with an interest in rulemaking, in particular those who are usually least represented, can participate in the rule-making process.

How to effectively integrate stakeholder consultation within a new RIA policy, including mandating at what point(s) of the regulatory cycle new regulatory proposals should be consulted upon.

How to enhance transparency using stakeholder consultation.

How to use stakeholder feedback in the RIA process and how it should inform decision making.

Box 3.1. Examples of good practice in consultations on regulatory impact analysis

In Canada, a variety of methods are used to involve stakeholders in consultations on RIAs. They include the use of emails, phone calls, third party-facilitated sessions, roundtable meetings and online consultations before the RIA is drafted. Regulatory proposals and their accompanying RIA are then pre-published in the Canada Gazette for public consultation. Stakeholders can highlight concerns regarding methodology or distributional impacts (e.g. undue burden placed on one region or industry) or submit alternative analyses. Departments and agencies must summarise the comments received, explain how stakeholder concerns were addressed, and provide the rationale for the regulatory organisation's response in the final RIA.

In Mexico, stakeholders are invited to comment on draft regulatory proposals and the accompanying RIA after they are submitted to the National Commission for Regulatory Improvement (CONAMER) for scrutiny. The general public can comment through the CONAMER consultation portal or send comments via e-mail, fax or letters. Consultations must be open for at least 30 working days; in practice, much longer consultation periods are the norm. CONAMER also uses other means to consult with stakeholders. These include advisory groups, media and social networks to diffuse the regulatory proposals and promote participation. Stakeholder comments are published on CONAMER’s website and must be taken into account by CONAMER and the agency sponsoring the regulation.

The European Commission, in turn, attaches a great deal of importance to stakeholder consultation in the RIA process. Since 2015, Inception Impact Assessments, which contain an initial assessment of possible impacts and options to be considered, are prepared and consulted on for 4 weeks, before a full RIA is conducted. Following this initial feedback period, the Commission conducts public consultations of 12 weeks during the development of initiatives with an impact assessment. Legislative proposals and the accompanying full RIA are then published online for feedback for 8 weeks following approval of the proposal by the College of Commissioners. Draft subordinate legislation is consulted on publicly for 4 weeks.1 All impact assessments and the related opinions of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) are published online once the Commission has adopted the relevant proposal. Reports of evaluations and fitness checks and the related RSB opinions are also published online.

1 As reported in the 2018 OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook, other countries such as Iceland have also taken steps to enhance stakeholder engagement. This country launched a new public consultation website in February 2018 that provides citizens and stakeholders with a single portal to view all draft laws and provide comments electronically (p. 196).

Governance of RIA: getting system design and set-up right

Governance is another key element in the design of a successful RIA system. Making the right choices with respect to a number of governance-related aspects is essential to trigger virtuous dynamics and sufficient incentives inside government. Three key aspects are discussed in this sub-section:

The establishment of a regulatory oversight system, which involves allocating roles and responsibilities and defining tasks throughout the regulatory process, especially ensuring that regulatory management tools are used effectively.

Putting in place the right mechanisms to facilitate the co-ordination of the RIA process across ministries as well as its management.

Forward-planning of legislative activity – in the absence of which successful RIA implementation will be compromised.

Establishing regulatory oversight is crucial for effective RIA

Robust oversight is a cornerstone of effective regulatory policy, including tools such as RIA. The 2012 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance calls for countries to “establish mechanisms and institutions to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals, support and implement regulatory and thereby foster regulatory quality”. In the same vein, evidence from developing countries shows that the establishment of an oversight body and the formal integration of RIA procedures into the policy-making process are essential for successful implementation of RIA. (Ladegaard, Lundkvist and Kamkhaji, 2018[2])

Effective regulatory oversight mechanisms incentivise civil servants to use regulatory management tools and follow due process to produce high-quality regulations that achieve their objectives and are aligned with long-term policy goals. Oversight can also help foster a whole-of-government perspective towards regulation, and performs essential co-ordination activities to ensure a homogenous approach to regulatory policy across the public administration. Moreover, it helps governments to establish credible commitments, align the incentives of different actors to attain policy goals, minimise risks of regulatory capture and, more generally, produce an optimal level of regulation (i.e. avoid both over- and under-regulation).

Box 3.2. Regulatory Oversight according to the 2012 OECD Recommendation

Principle 3 of the 2012 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance calls for countries to “establish mechanisms and institutions to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals, support and implement regulatory policy and thereby foster regulatory quality”. The Recommendation highlights the importance of “a standing body charged with regulatory oversight (…) established close to the centre of government, to ensure that regulation serves whole‑of‑government policy” and outlines a wide range of institutional oversight functions and tasks to promote high quality evidence-based decision making and enhance the impact of regulatory policy.

In line with the Recommendation, a working definition of "regulatory oversight" has been employed in the 2018 Regulatory Policy Outlook, which adopts a mix between a functional and an institutional approach. "Regulatory oversight" is defined as the variety of functions and tasks carried out by bodies/entities in the executive or at arm’s length from the government in order to promote high-quality evidence-based regulatory decision making. These functions can be categorised in five areas, which however do not need to be carried out by a single institution or body. They are presented below.

|

Areas of regulatory oversight |

Key tasks |

|---|---|

|

Quality control (scrutiny of process) |

|

|

Identifying areas of policy where regulation can be made more effective(scrutiny of substance) |

|

|

Systematic improvement of regulatory policy (scrutiny of the system) |

|

|

Co-ordination (coherence of the approach in the administration) |

|

|

Guidance, advice and support (capacity building in the administration) |

|

Source: (OECD, 2018[6]).

As shown in Box 3.2, the OECD has defined five key functions of regulatory oversight. Of these, three are directly related to RIA: quality control, co-ordination, and guidance, and advice and support.

The function of quality control focuses on scrutiny of RIA and placing incentives on civil servants to conduct RIAs consistently and in a meaningful fashion. It concerns the respect of set procedures and methodological standards, consideration of relevant impacts as well as appropriate linkages with the rest of the policy cycle (including other regulatory policy tools, such as stakeholder consultation and ex post evaluation). Co-ordination, in turn, is essential to promote a whole of government, co-ordinated approach to regulatory quality as well as to ensure consistency in RIA implementation. The guidance, advice and support notably consists of providing appropriate guidance and helping to build RIA-related capacity.

To fulfil its role, a regulatory oversight body needs a consistent mandate, which entails a full range of powers to control, supervise and influence the activity of the ministries in charge of policy portfolios. In addition, the oversight body requires sufficient resources and attributions to carry out an active enforcement of activities, while overseeing the complete regulatory policy. Therefore, effective oversight bodies tend to encompass a core team that has a “cross-functional” nature, i.e. involving individuals with different backgrounds and skills, including economics, law, and political science.

The location of the oversight bodies is also an important consideration. The 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance highlights the importance of “a standing body charged with regulatory oversight (…) established close to the centre of government, to ensure that regulation serves whole-of-government policy”. It stresses, however, that the specific institutional solution “must be adapted to each system of governance”; e.g. level of administrative centralisation, power distribution between the central government and ministries/agencies, legal and cultural specificities, sociodemographic factors, etc.

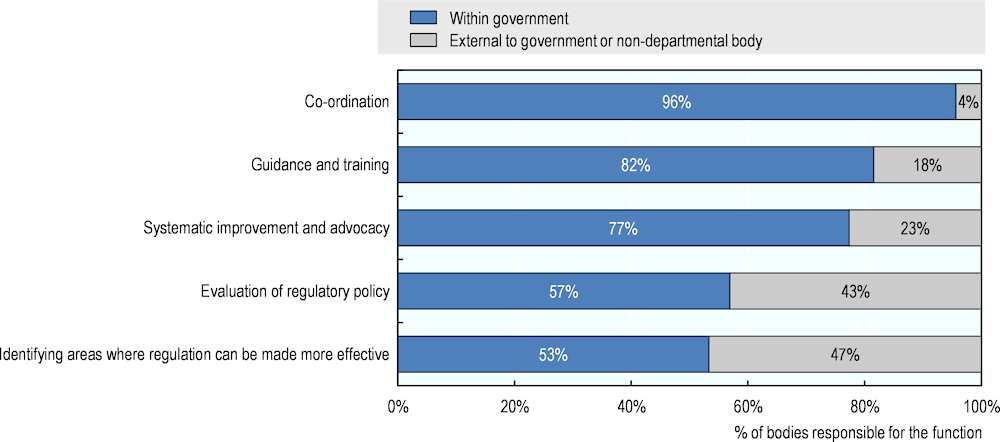

While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, institutionalising oversight bodies close to the centre of government can contribute to their effectiveness given the associated resource-intensive processes and the need for extensive co-ordination and information sharing across ministries, departments and agencies. Although the oversight functions do not need to be carried out by a single body, effective co-ordination between these functions is crucial for success. Here again, locating oversight functions close to the centre of government can help ensure appropriate co-ordination and dissemination of the necessary guidance and knowledge. Indeed, as shown in Figure 3.1, the co-ordination and guidance functions, which are crucial during the early stages of RIA development, are held by oversight bodies within government in the vast majority of reporting countries – whereas scrutiny functions are comparatively more often located outside of government or in non-departmental bodies.

Figure 3.1. Location of oversight functions

The Mauritian Government has a number of options for developing a strong regulatory oversight body. As mentioned above, a very important consideration will be where to locate the oversight body within the administration. At the beginning, it would be more effective for Mauritius to follow OECD best practice and establish its oversight body as close to the centre of government as possible, in a part of the administration with a strategic overview of government activity and the authority to drive change. It would be useful for the Government to consider what has worked effectively in the past to drive whole-of-government policy reform; e.g. the inter-ministerial committee and technical committees set up to drive forward the “Doing Business” reforms.

Potential locations include the Prime Minister’s Office, which would represent strong political symbol of the government’s commitment to RIA, although it was reported to the OECD team that the office faces capacity constraints and would have limited capability to run and enforce an oversight function. The Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development, in turn, possesses the strongest institutional levers to drive change across the Mauritian Government through its control of the budget process and possesses analytical experience, although this has been more narrowly focused on financial or budgetary impacts.

The Attorney General’s Office has a longstanding background in working across government on legislative drafting and ensuring that new laws are legal and constitutional. It also possesses a strategic view across the Legislature, Judiciary and the Executive. However, it has not had any role in policy development to date, nor does it possess sufficient analytical capacity.

There may also be a role to play for non-governmental public bodies. The Law Reform Commission has a strong record on working to improve regulatory quality through its function of reviewing and recommending changes to legislation. However, it also faces capacity constraints, including a lack of economic analysis expertise amongst its officials. The National Audit Office possesses a strong amount of analytical capacity, although they have had no role in policy development to date, and their work is predominantly ex post in nature.

Embedding a robust regulatory oversight system will require a gradual approach to developing the five oversight functions, which is adapted to the specificities of the Mauritian administration. The oversight functions that are more critical for the Government to implement in the short term would include co‑ordinating and promoting a whole-of-government, concerted approach to regulatory quality, and providing guidance, advice and support on the RIA process.

It is imperative, particularly in the longer run, that Mauritius seeks to strengthen regulatory oversight and scrutiny and ensures these functions are implemented effectively. It will be particularly important to ensure that the key roles and responsibilities are clearly understood, tasks are well defined and regulatory management tools are used effectively.

Co-ordination and management of RIA

An effective RIA system needs to be co-ordinated and carefully managed across the central ministries of government and other law-making institutions such as parastatal organisations. Different parts of the government need the right incentives to systemically share information and pool expertise and knowledge. It is important to ensure there is sufficient understanding of RIA as a long-term governance reform that has substantial resource implications. For example, according to the World Bank, Greece adopted an extremely ambitious RIA program in 2006 but “low implementation capacity and a lack of co-ordinating body resulted in low quality RIAs, if any”. (Ladegaard, Lundkvist and Kamkhaji, 2018[2])

If co-ordinating efforts are not instituted, officials involved in RIA will most probably be isolated from each other and not work in a concerted and efficient manner. It is therefore important to consider which mechanisms are necessary in order to facilitate the co-ordination of the RIA process across ministries. This sub-section briefly presents international examples that could serve as source of inspiration in that respect. Box 3.3, for instance, presents how UK and Mexican authorities encourage co‑ordination across government in their respective systems.

Box 3.3. Network of officials for regulatory policy, examples from OECD countries

In the United Kingdom, government departments with a responsibility for producing regulations in their respective policy areas and certain regulators have a Better Regulation Unit (BRU). A BRU consists of a team of civil servants that oversees the department’s processes for better regulation and advises on how to comply with these requirements. It is at the discretion of each department to determine the scope of the BRU’s role, its resourcing (i.e. staff numbers, composition of policy officials and analysts, and allocation of time on this agenda versus others) and position within the departmental structure. However, their functions generally include promoting the use and application of better regulation principles in policy making, advising policy teams on how to develop a RIA (or post-implementation review) including queries on methodology and analysis, and advising policy teams on the appropriate schedule to submit a RIA to the oversight body (the Regulatory Policy Committee) for scrutiny.

In Mexico, the heads of the entities and decentralised agencies of the federal public administration appoint officials who act as better regulation liaisons before CONAMER, and they are assigned specific tasks within the better regulation process. They are in charge of co-ordinating and enforcing this process within their own entities and agencies, submitting to CONAMER the better regulation programme related to the regulations and procedures they implement, as well as of signing and sending both drafts – regulations and procedures – that should be subject to the process of better regulation. These liaison officials should be deputy ministers or chief administrative officers, that is, hold the next level after the incumbents, which strengthens the process.

Source: (OECD, 2019[7]).

In addition, a number of OECD countries have implemented ICT solutions to facilitate the RIA process operation and interaction between the ministries and entities that issue regulations and the oversight body. For example, in the Czech Republic, the Legislative Rules of the Government (a government resolution) stipulate the regulation-making process, including how ministries are expected to consult with each other during the policy making process. RIA is part of the dossier sent around to all ministries and central agencies for consultations, including the RIA Unit of the Government Office. The dossier is circulated electronically via an automatised process. As a general rule, anyone can comment on the quality of RIA and this happens systematically in practice. The inter-ministerial consultation process is enforced by the Legal Department of the Government Office. Further examples of how ICT can be used to improve RIA‑related co-ordination are presented in Box 3.4.

Box 3.4. Selected examples of IT tools for RIA inter-ministerial co-ordination

Netherlands

Ministries can make use of a digital tool (toetsloket) to present a draft legislative proposal, including the accompanying RIA statement, to several scrutiny authorities throughout central government responsible for overseeing the quality of different aspects the RIA framework; e.g. the Ministry of Justice and Security provides scrutiny of legislative quality, whereas the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate scrutinises assessments of regulatory burdens on business. The scrutiny authority returns their comments on the draft through the portal, which the lead ministry also uses to responds to the comments. The discussion is ended with the approval (or otherwise) of the draft (including any modifications) via the portal.

Slovakia

All legislative drafts and their accompanying impact assessments are published on the government portal www.slov-lex.sk at the same time as they enter the inter-ministerial comment procedure. The portal provides a single access point to comment on legislative proposals and non-legislative drafts (e.g. concept notes, green or white papers). It seeks to ensure easier orientation and search in legislative materials to facilitate the inter-ministerial consultation process. Both public authorities and members of the general public can provide comments on the legislative drafts and the accompanying material. Accompanying impact assessments to the legislative proposal are updated on the basis of comments received. Any feedback provided is part of the dossier submitted to the government for discussion.

Korea

Korea has developed a clear and relevant set of criteria to highlight regulation that is likely to require a full and detailed analysis. It pays attention to competition and trade considerations, including departures from international standards. In addition, central ministries are required to outline the intended evaluation plan as part of each RIA. To increase the quality of RIA and lessen the burden of preparing RIA statements in Korea, e-RIA was launched in 2015. It is linked to the national statistical database and provides the public officials who prepare RIAs the possibility to automatically obtain the necessary data for cost-benefit analysis, and a sufficient amount of descriptions and examples for all fields. As all fields are mandatory, e-RIA also prevents users (regulators) from omitting important data and information. RIAs are produced automatically upon completion of all fields.

Establishing a forward planning system

The OECD recommend that programming government policy and legislative work is a fundamental building block of regulatory policy to support a continuous policy cycle for regulatory decision-making. Consultation will be more effective and the RIA process easier to manage if there is clear forward planning of legislation.

Successful implementation of RIA will be compromised in the absence of a functioning legislation planning system. This includes a system for providing a forward look for upcoming legislation, such as those detailed in Box 3.5. As discussed in Section 2, there is no equivalent as of this yet in Mauritius. A legislative programme is developed by ministries at the beginning of a parliament, but it does not provide a complete overview of legislative activity. It is not published and thus cannot be used to inform stakeholder consultation processes.

It is important to consider which mechanisms would be suitable for establishing a system of forward planning for legislation. This could involve requiring ministries to submit plans for upcoming primary and secondary legislation as a first step towards a more targeted RIA programme. This would enable the Government to carry out a quick preliminary analysis of the scope of the legislation, stakeholders that would be impacted and the magnitude of potential impacts. Based on this preliminary analysis, a decision could be made on the necessary depth of RIA. It would be even more effective if this list could be collated as a forward plan, published and made available to all stakeholders to alert them about upcoming legislation.

Box 3.5. Forward planning on regulatory measures

A number of OECD countries have established mechanisms for publishing details of the regulation they plan to prepare in the future. Forward planning has proven to be useful to improve transparency, predictability and co-ordination of regulations. It fosters the participation of interested parties as early as possible in the regulatory process and it can reduce transaction costs by giving more extended notice of forthcoming regulations. .

In Ireland, primary laws are subject to a public forward agenda. Indeed, the Office of the Chief Whip prepares the government legislative programme for primary legislation for the upcoming parliamentary session. It publishes, along with a press release, the programme on the website of the Department of Taoiseach (government department of the Head of Government) before each parliamentary session. The Government Legislation Committee (GLC), chaired by the Government Chief Whip, oversees the implementation of the programme in close co-operation with the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel to the Government (OPC). It makes recommendations to the government in relation to the level of priority that should be given to the drafting of each bill. The point of this procedure is to anticipate blockages that might occur in the process and recommend actions to avoid any delays in the drafting process.

In Sweden, work flows from the government’s political agenda, based on the coalition agreement at the start of each political term. The Prime minister’s Office submits a list of upcoming bill proposals twice a year to the parliament. The annual Budget Bill also indicates the direction of reforms. It gives significant information about priorities, including new legislation for the coming years. The government also informs the Riksdag annually about appointed Committees of Inquiry and their work (kommittéberättelsen, the Committee Report). These documents are available on the government’s website.

The Korean Futuristic Regulatory Map analyses and predicts the current and future trends of industrial convergence and technological development in the fields of emerging industry. Based on such analysis, the Futuristic Regulatory Map provides a forward-looking plan for regulatory reform. It provides a direction for future policy reforms, a plan for improvement of existing regulations. The Futuristic Regulatory Map is a specific project focused on one precise field; nevertheless, it illustrates a good practice of forward-planning based on the expected needs for regulatory improvement.

Source: (OECD, 2017[10]).

Targeted and appropriate RIA process and methodology – how to carry out RIA

If Mauritius is to use RIA in a systematic way, the government needs to carefully design the RIA process to be followed across the government that is targeted towards where it can add the greatest value and select an appropriate methodological approach in order to compare the costs and benefits of proposed regulations. This sub-section discusses some of the key aspects deserving consideration in this respect: key RIA steps; methodological choices available; practical application of the proportionality principle; and data collection and the evidence base.

Establishing a RIA process

The OECD RIA Best Practice Principles have set out the key elements that should be integrated into any effective RIA framework. However, it should be noted that RIA is an iterative process; therefore some of the steps might be performed repeatedly using inputs from the subsequent ones.

It is crucial that RIA is implemented effectively within the administrative context and incentivises officials to integrate RIA into the early stages of the policy process for the formulation of new regulatory proposals. No RIA can be successful without defining the policy context and objectives, in particular the systematic identification of the problem that provides the basis for action by government. Poor problem identification might lead to unjustified regulations and difficulties in monitoring and assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of these regulations.

As in many developing nations, the typical approach to regulatory interventions in Mauritius can leave little room for the use of non-regulatory alternatives to intervene and solve problems and regulations generally appear as the only possible way to intervene. Therefore there is scope for Mauritius to use RIA to explore the use of alternatives to regulation in various regulatory and policy fields.

The RIA process that Mauritius implements should be as simple and flexible as possible (particularly at the start), while encompassing certain key features. Being able to adapt to the needs of decision-makers (e.g. ministry officials and ministers) is key to maintaining the relevance of RIA. However, at a minimum, the Government should ensure that every process of RIA for Mauritius should follow the best practice steps summarised above.

Selecting a RIA Methodology

Various RIA methodologies can be used to compare positive and negative impacts of regulation, including qualitative and quantitative methods, cost-benefit analysis and multi-criteria methods, partial and general equilibrium analysis (see a summary of other methodologies available for RIA in Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Choosing the right methodology: Towards more sophisticated RIA methods?

One of the key challenges in performing RIA is the choice of the most appropriate methodology to assess the impacts and compare alternative regulatory options. A first important choice to be made is the choice of whether to perform a partial equilibrium analysis or a general equilibrium analysis. The latter typically requires modelling abilities, and as such can and should be chosen only when a number of specific conditions are met: in particular, indirect impacts have to appear significant, and spread across various sectors of the economy; in addition, there must be sufficient skills within the administration, or the possibility to commission a general equilibrium modelling analysis from a high-quality, reliable group of researchers inside or outside the administration.

General equilibrium analysis is preferred by many scholars for its ability to capture very dispersed indirect impacts of regulation. For the time being, however, it is likely that the overwhelming majority of administrations will continue to use partial equilibrium analysis in RIA. However, where a regulation will materially affect one or more closely related markets or will have diverse and far-reaching effects across the economy, a general equilibrium framework is required to assess these impacts. When performing partial equilibrium analysis, typically the methodological choices available to administrations are the following:

Least-cost analysis looks only at costs, in order to select the alternative option that entails the lowest cost. This method is typically chosen whenever benefits are fixed, and the administrations only needs to choose how to achieve them.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) entails that administrations quantify (not monetise) the benefits that would be generated by one USD of costs imposed on society. The typical method used to compare options is thus the so-called benefit-cost ratio, which means dividing the benefits by costs. This method is normally used to all expenditure programs, as it leads to identifying the “value for money” of various expenditure programs. A typical question that can be answered through cost-effectiveness analysis is “how many jobs will be created for every Dollar invested in this option?”; or, “how many lives are saved by every Euro spent on this option?”.

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) entails the monetisation of all (or the most important) costs and benefits related to all viable alternatives at hand. In its most recurrent form, it disregards distributional impacts and only focuses on the selection of the regulatory alternative that exhibits the highest societal net benefit. Accordingly, the most common methodology in cost-benefit analysis is the “net benefits” calculation, which differs from the “benefit/cost ratio” method that is typically used in cost-effectiveness analysis (being benefit minus costs, rather than benefits divided by costs).

Multi-criteria analysis allows a comparison of alternative policy options along a set of pre-determined criteria. For example, criteria chosen could include the impact on SMEs, the degree of protection of fundamental rights, consumer protection, etc. Multi-Criteria Analysis is particularly useful when Impact Assessment has to be reconciled with specific policy objectives, and as such is used as an instrument of policy coherence. This method is more likely to capture distributional impacts, although this crucially depends on the criteria chosen for evaluating options.

Source: (OECD, 2015[11]).

RIA methodologies should be tailored to the specific needs of each country. Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) is one methodology that has been applied successfully but the complexity of the methodology varies across and even within countries. Rather than always engaging in quantitative CBA, it is essential that the Mauritian officials in charge of RIA identify all groups of stakeholders who would be impacted and how they will be impacted. They should consider all possible direct and indirect impacts to enable a meaningful comparison of alternative regulatory options that could in principle address the problem identified.

There are a number of options for the Mauritian administration in implementing its RIA methodology. It could begin with a simpler RIA approach with single- or multi-criteria qualitative analysis, and then gradually move to more quantitative analysis (CBA or other). It has also been common for countries to start looking at administrative burdens or regulatory costs first before developing a whole-of-government approach that analyses all costs and benefits of proposed regulations. It could be a long-term goal for the Mauritian administration to move toward using full CBA in its RIA framework.

For example, the Government of Portugal has chosen a gradual approach to rolling out its system of RIA. When introduced in 2017, the Portuguese approach to RIA (named Legislative Impact Analysis) required policy makers to qualitatively describe benefits and to quantify the impact of new regulations on businesses. It also included an SME test and a competition impact assessment. The Technical Unit for Legislative Impact Assessment (UTAIL) was established to provide oversight and support for the new RIA. In 2018, ministries were required to assess legislative impacts on citizens and as of 2019 also impacts on public administration.

There are a number of options through which the Mauritian Government could develop a RIA methodology that follows international best practice. This programme of work could be overseen by the section (or sections) of government tasked with the new regulatory oversight function. The Mauritian Government may consider focusing the RIA methodology more narrowly at first, either by choosing a more qualitative approach to describing the impacts of regulation or assessing costs to business or administrative burdens, before broadening it out to analyse the wider societal costs and benefits of regulatory proposals. For proposals that are estimated to be high-impact, ministries should be required to conduct a more detailed quantitative RIA analysis (using the methodology set out in the new RIA manual). For lower-impact proposals, the RIA manual should state that less detailed analysis can be provided.

The proportionality principle: “don’t use a cannon to kill a fly!”

Many OECD countries have acknowledged that not every regulation or proposal needs the same level of scrutiny. In fact, the RIA process itself should pass a (rough) CBA – the costs and time to develop and analyse a regulatory proposal should be clearly outweighed by the positive effect that this has of improved policy decisions or regulatory quality. Therefore, it is important the resources used to develop a policy scale with the size of the problem and its solution.

Accordingly, many OECD countries and the EU have a tiered approach to RIA that uses proportionality and threshold tests. Some countries require lighter analysis (“light”, preliminary” or “small” RIA) for all regulations and a more thorough analysis for selected draft regulations with more significant impact. Regulations are exempt from a RIA in certain cases, such as national emergencies. In other cases, policymakers are required to undertake a full RIA if the proposal has a certain level of impact or meets certain qualitative criteria.

The OECD’s RIA Best Practice Principles have pointed to a number of options for sorting out which legislative proposals have to go through a certain level of analysis:

Setting quantitative thresholds (e.g. potential impacts over USD 100 million in the USA).

Introducing a set of criteria on issues such as the extent of the impact on competition, market openness, employment, productivity, innovation, investment as well the number of people affected by the proposed regulation.

Applying multi-criteria analysis.1

Setting a general principle of proportionate analysis (such as the one used by the European Commission). The choice of how deep the RIA should be can be left to the administration itself, based on the principle of proportionality. At the same time, such choice requires the scrutiny of an oversight body able to intervene and suggest a deeper analysis in case the proportionality principle has not been applied.

Box 3.7 presents a number of other relevant examples form selected jurisdictions illustrating how the proportionality principle is applied in practice.

Box 3.7. Selected examples of proportionate approaches of RIA

United States: A RIA is required for significant and economically significant regulatory actions as defined under Executive Order 12866 and Executive Order 13563. An economically significant regulatory action is one that:

is likely to impose costs, benefits, or transfers of $100 million or more in any given year;

adversely affects in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.

The United States defined “major” rules in 1981 as those which are likely to impose annual costs exceeding 100 million or those likely to impose major increases in costs for a specific sector or region, or have significant adverse effects on competition, employment, investment, productivity or innovation.

An RIA is required for economically significant regulations. In defining “economically significant,” OMB (2011a) states, “The 100 million threshold applies to the impact of the proposed or final regulation in any one year, and it includes benefits, costs or transfers.” The word “or” is important: the categories are considered separately, not summed, so 100 million in any of the three categories – annual benefits, or costs, or transfers – is sufficient.

For example, a regulation with USD 5 million in benefits, USD 60 million in costs, and USD 40 million in transfers is not economically significant. An RIA is also required for regulations deemed to be significant for other reasons and is an essential element of good regulatory practice.

United Kingdom: the UK addressed this issue by requiring a formal preliminary assessment to be undertaken, which provides a general understanding of the size of likely regulatory costs and forms the basis for determining what level of assessment will subsequently be required. An alternative approach is to provide only qualitative guidance as to the level of analysis of compliance costs (or other RIA elements) that is required. Where there is a requirement for compliance cost assessments to be assessed and approved by a regulatory reform body, this approach implies that actual practice will be determined to some extent by negotiation between this body and the ministry preparing the assessment.

In UK, impacts on business, charities and voluntary sector are considered in determining whether the RIA threshold has been crossed. Clearly, the welfare economics perspective underlying RIA would suggest that, whatever the threshold used, it should be assessed in terms of impact on any sector in society, rather than being limited to impact on certain sectors.

Mexico: Mexico specifies three levels of required RIA and distinguishes between them by a combination of both quantitative cost thresholds and qualitative judgments as to whether the regulation would have non-eligible impacts on employment or business productivity. For ordinary RIAs comes a second test – qualitative and quantitative – what Mexico calls a “calculator for impact differentiation”, where as a result of a 10 questions checklist, the regulation can be subject to a High Impact RIA or a Moderate Impact RIA, where the latter contains less details in the analysis.

South Korea: the Korean test requires quantitative RIA to be undertaken if it affects more than 1 million people and/or 10 million Won, there is a clear restriction on market competition or a clear departure from international standards.

Netherlands: the Netherlands approach to “filtering” regulation for RIA purposes is different again. It has long used a two-step RIA process, where the results of a preliminary RIA are assessed by the regulatory reform authority to determine whether a full RIA must be completed and which RIA tests must be applied to the proposal.

Australia: Preliminary Assessment determines whether a proposal requires a RIA (or a RIS, regulation impact statement as they call it) for both primary and subordinate regulation (as well as quasi-regulatory proposals where there is an expectation of compliance). A Regulation Impact Statement is required for all Cabinet submissions. This includes proposals of a minor or machinery nature and proposals with no regulatory impact on business, community organizations or individuals. A RIA is also mandatory for any non-Cabinet decision made by any Australian Government entity if that decision is likely to have a measurable impact on businesses, community organizations, individuals or any combination of them.

Belgium: applies a hybrid system. For example, of the 21 topics that are covered in the RIA, 17 consist of a quick qualitative test (positive/negative impact or no impact) based on indicators. The other 4 topics (gender, SMEs, administrative burdens, and policy coherence for development) consists of a more thorough and quantitative approach, including the nature and extent of positive and negative impacts.

Canada: applies RIA to all subordinate regulations, but employs a Triage System to decide the extent of the analysis. The Triage System underscores the Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management’s principle of proportionally, in order to focus the analysis where it is most needed. The development of a Triage Statement early in the development of the regulatory proposal determines whether the proposal will require a full or expedited RIA, based on costs and other factors:

Low impact: cost less than CAD 10 million present value over a 10-year period or less than CAD 1 million annually

Medium impact: Costs CAD 10 million to CAD 100 million present value or CAD 1 million to CAD 10 million annually

High impact: Costs greater than CAD 100 million present value or greater than CAD 10 million annually

New Zealand employs a qualitative test to decide whether to apply RIA to all types of regulation. Whenever draft regulation falls into both of the following categories, then RIA is required: i) the policy initiative is expected to lead to a Cabinet paper, and ii) the policy initiative considers options that involve creating, amending or repealing legislation (either primary legislation or disallowable instruments for the purposes of the Legislation Act 2012).

European Commission: a qualitative test is employed to decide whether to apply RIA for all types of regulation. Impact assessments are prepared for Commission initiatives expected to have significant economic, social or environmental impacts. The Commission Secretariat general decides whether or not this threshold is met on the basis of reasoned proposal made by the lead service. Results are published in a roadmap.

Source: (OECD, 2015[12]).

There are a number of mechanisms that the Government of Mauritius could consider for targeting RIA efforts, in order to allocate analytical resources to where they could potentially deliver the greatest added value.

Establishing a forward planning process (see sub-section on “Establishing a forward planning system”) as a first step towards a more targeted RIA programme.

Determining the depth of RIA analysis that should be carried out for legislative proposals that are classified as “low impact” and “higher impact” RIAs.

Defining a list and/or criteria of any regulatory proposals that will be exempted from RIA because they do not have any major impact on regulated parties.

The importance of data collection

Data quality, an essential element of proper analysis, has been recognised as one of the most challenging aspects of RIA because it can be time- and resource-consuming and requires a systematic and functional approach. A poor data collection strategy can mean that appropriate evidence to conduct good analysis is lacking.

For effective implementation of RIA, sound strategies on collecting and accessing data must be developed. Policy making should strive to utilise all potential sources of unbiased data (academics, institutes of statistics, etc.) in order to ensure that governments take the best possible course of action, based on the most complete information set available. This issue is becoming even more pertinent in the era of “big data”.

The availability of data is essential for each step of RIA, i.e. for a meaningful problem definition, for a careful analysis of the alternative solutions available, and for an estimation of the compliance and enforcement costs associated with each of the alternative policy options. It is increasingly important that policy makers rely on statistical institutes in order to ensure that they have a complete and constantly evolving data to draw upon when developing RIA.

The information that RIA requires can be collected in numerous ways. An important procedure to integrate data for RIA takes place during the consultation process. There are, however, other sources for data collection (see Table 3.1, which is also relevant for the sub-section on developing technical capacity for RIA later in this document). In addition, data collection can be classified as primary (collected for the purpose of RIA) or secondary (derived from data previously collected for other purposes). Exploiting all available secondary data helps to limit RIA-related costs and avoid stakeholder disaffection.

Table 3.1. Addressing skills and data requirements for RIA

|

Source |

Action |

|---|---|

|

1. In-house expertise of economists; lawyers and analysts |

1. Define problem; analyse its extent through in-house knowledge and expertise, and existing studies and information. |

|

2. Commission research and studies |

2. Commission statistics from national research institutes; statistics organisations or consultants, e.g. cost-benefit analyses. |

|

3. Dedicated RIA training |

3. Training in quantitative techniques and analysis is imperative, so as to develop a public sector capacity to conduct RIAs. |

|

4. Networking for RIA |

4. Establish a central network to provide mutual support for those conducting RIAs and also where “best practice” from international experience can be shared. |

|

5. International data and “best practice” |

5. Availability of EU sources – EUROSTAT data, and EUROBAROMETER surveys; and evidence in previous EU reports, studies and green papers. Other international material available from OECD and World Bank. |

Source: Ferris (2006), Good RIA Practices in Selected EU States, p. 6.

It is important to consider which mechanisms would be suitable for ensuring that relevant data are available for RIA, while considering how to use integrate the data from Statistics Mauritius (and other secondary sources) into the RIA process.

Developing technical capacity for RIA

This sub-section firstly discusses the main aspects that need to be considered to ensure the availability of the necessary skills and capacity for RIA, both from a methodological standpoint and in terms of building ownership of the RIA system over time. It then presents various options that can be considered for a gradual introduction of RIA in Mauritius – which is advisable given existing skills and capacity constraints.

How to strengthen RIA capacity in the government

As discussed in Section 2, there is presently insufficient technical capacity amongst officials within the Mauritian administration to prepare robust RIAs. Where any analytical capacity does exist at present, it is specific to the policy area, e.g. the Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development has analytical capacity in analysing the financial impact of new regulations, whilst the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development contains expertise in conducting Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental Assessments.

Ensuring that ministries are capable of complying with procedural requirements and meeting quality standards is a fundamental factor to increase the chances that RIA reforms in Mauritius last and perform on a sustained basis. Officials in ministries and regulatory bodies charged with carrying out RIAs, as well as those within the regulatory oversight function, must have the skills to prepare high-quality RIAs, including an understanding of the role of RIA in ensuring regulatory quality and an understanding of methodological requirements and data collection strategies. Training must therefore be provided to civil servants involved in RIA.

Beyond the technical need for training in RIA, training communicates the message to officials that RIA is an important issue, recognised as such by the administrative and political hierarchy. It can be seen as a measure of the political commitment to RIA principles. It also fosters a sense of ownership for reform initiatives, and enhances co-ordination and regulatory coherence.

According to the World Bank, the effectiveness of RIA training may be limited unless capacity-building efforts focus on clear targets and on-the-job requirements: “RIA reforms should focus less on broad and generic RIA training, but rather be targeted to specific RIA requirements of the country. It seems important that training efforts are well measured, anchored and led by the reforming country, and that experience and knowledge can feed into further developments and learning. Training will only become efficient and useful to motivate reluctant civil servants if they know they will be rewarded through their ability to master RIA in their daily work.” (Ladegaard, Lundkvist and Kamkhaji, 2018[2])

Key areas that should be covered by RIA training include techniques for problem definition, setting policy objectives, identifying alternative solution, impact assessment, stakeholder engagement, and implementation of RIA. Training should to the extent possible focus on real-life practical examples and case studies, and aim at developing capacity over time (i.e. not a one-off experience). Detailed guidance material on both the procedural requirements associated with RIA and the substantive aspects of RIA preparation should be published. An overview of key aspects to be considered with regard to the training of regulators in this area is provided in Box 3.8.

In addition, pilot projects can be used to make RIA training more targeted and relevant, which helps secure buy-in of the officials who are to implement RIA. These can range from the large-scale rolling out of RIA in selected government departments to very small-scale, half-day workshops to discuss a particular RIA with policy makers and stakeholders. (Adelle et al., 2015[13])

Box 3.8. “Train the regulators”

Regulators must have the skills to conduct high-quality RIA. They should clearly understand the methodological and data collection processes and the role RIA plays in assuring regulatory quality. The stringency of RIA requirements should be progressively increased as the skills and capacities of the regulating ministries improve.

It is particularly important to provide training in the early stages of a RIA programme, when both technical skills and the cultural acceptance of the use of RIA as a policy tool need to be cultivated.

However, a high level of investment must be maintained over time, to counter staff turnover and assist in developing the broader cultural changes that must be achieved across entire organizations.

One way to improve RIA is to incorporate RIA training into national training programmes for the public administration.

RIA manuals and other guidelines are important complements to training, but not a substitute for it. A guidance manual can be less effective if it is perceived as too legalistic, excessively detailed, or impractical. The best materials seem to be those that are simple and based on concrete examples or case studies, and provide straightforward, practical guidance on data collection and methodologies.

Published guidelines should be updated frequently to reflect changes in specific RIA requirements, especially in light of the need for RIA to gain progressively in rigour and scope as skills and experience accumulate within an administration. It is also important to ensure that published materials accurately reflect new learning about regulatory tools, methods and institutions.

Source: (OECD, 2005[14]).

Governments should publish detailed guidance material, typically covering both the procedural requirements associated with RIA and the substantive aspects of RIA preparation. In addition, guidance on various analytical techniques should be made available. Given the technical nature of RIA techniques (such as CBA), general RIA guidance documents sometimes refer readers to separate, more detailed guidance documents. More recently, a number of countries have developed software-based tools2 that can be used to assist in RIA development. These calculators are, in some countries, accessible also to stakeholders, who can calculate the costs of current, drafted or potential regulations or associated changes.

The OECD also recommend that accountability- and performance-oriented arrangements should be implemented in accordance with the legal and administrative system of a given country. These can include: i) making draft RIAs public and subject to public consultation; ii) specifying the name of the responsible person for every regulatory proposal that is tabled by government and published online; iii) including the evaluation of RIA work as an element in the evaluation of the performance and the determination of productivity of the civil servant; iv) specifying that skills in RIA are an element to be considered for career promotion to specific high-responsibility positions in the administration.

It is therefore crucial that a programme of capacity building is undertaken on RIA in Mauritius. Accordingly, the following aspects will need to be considered:

Ensure that sufficient financial and human resources are allocated that allow for the establishment of a dedicated RIA capacity within the oversight function and ministries – RIA is not a cost free activity and will require sustained investment.

Consider where to focus capacity building initiatives in the short and then longer term to ensure that sufficient technical capacity is built up.

Develop detailed guidance material covering both the procedural requirements associated with RIA and the substantive aspects of RIA preparation.

The Government should ensure that ministry officials preparing RIAs have a clear point of contact to approach for advice and training requests throughout the policy process.

Create informal mechanisms to share experiences and good practices among RIA experts at a technical level.

Consider what accountability- and performance-oriented arrangements could be implemented within the government.

Implementing RIA: at once or gradually?

Embedding RIA and building capacity within the Mauritian system will not be a sprint but a careful and thorough race that needs to sink into the culture of the public administration. OECD best practice suggests that Governments need to decide whether to implement RIA at once or gradually. Existing constraints, notably in terms of capacity and expertise, suggest that a gradual approach would be better adapted to the current situation in Mauritius. Once the above-mentioned preconditions are met, various possible paths can be considered for the gradual introduction of RIA:

A pilot phase, then the institutionalisation of RIA for all or all major regulations.

Starting with a simplified methodology, and then expanding it.

Starting from some institutions, and then expand RIA to others.

Starting from major regulatory proposals, and then lower the threshold to cover less significant regulations.

Starting with binding regulation and then moving to soft-law.

Starting with qualitative analysis, and then gradually moving to quantitative analysis (CBA or other).

From concentrated RIA expertise to more distributed responsibilities.

Mauritius is clearly at an early stage of its pathway to RIA. As part of this project to institute a RIA framework, the OECD has assisted the Mauritian administration in running one RIA pilot. This pilot has been carried out according to good practices and quality standards and it could be used to “sell” the benefits of deploying the tool. The sample of “proper RIAs” could be expanded over the years, as capacities and familiarity with the tool increase. It will be critical that the Mauritian Government considers how to ensure that the lessons learned from pilot RIAs are capitalised upon, taken forward and disseminated throughout the administration.

References

[13] Adelle, C. et al. (2015), “New development: Regulatory impact assessment in developing countries—tales from the road to good governance”, Public Money & Management, 35:3, 233-238, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.1027500.

[5] European Commission (2019), Regulatory Scrutiny Board, website accessed in November 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/regulatory-scrutiny-board_en (accessed on 14 November 2019).

[8] Government of the Netherlands (n.d.), Integral assessment framework for policy and regulations, https://www.kcwj.nl/kennisbank/integraal-afwegingskader-voor-beleid-en-regelgeving (website accessed in November 2019).

[2] Ladegaard, P., P. Lundkvist and J. Kamkhaji (2018), Giving Sisyphus a helping hand : pathways for sustainable RIA systems in developing countries, World Bank Group, Washington D.C, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/691961521463875777/Giving-Sisyphus-a-helping-hand-pathways-for-sustainable-RIA-systems-in-developing-countries.

[7] OECD (2019), Implementing Regulatory Impact Analysis in the Central Government of Peru: Case Studies 2014-16, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305786-en.

[6] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[10] OECD (2017), OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Chile Evaulation Report: Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/regulatory-impact-assessment-in-chile.htm.

[4] OECD (2017), Regulatory Policy in Korea: Towards Better Regulation, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264274600-en.

[3] OECD (2016), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Philippines 2016, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264254510-en.

[9] OECD (2016), Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

[12] OECD (2015), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

[11] OECD (2015), “Regulatory Impact Assessment and regulatory policy”, in Regulatory Policy in Perspective: A Reader’s Companion to the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241800-5-en.

[14] OECD (2005), Regulatory Impact Analysis in OECD Countries. Challenges for developing countries. South Asian-Third High Level Investment Roundtable., https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/35258511.pdf.

[1] OECD (2004), Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) Inventory, note prepared by the OECD Secretariat for the Public Governance Committee meeting, OECD, Paris, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Notes

← 1. For example in Switzerland, a more complex RIA is required when three criteria from a list of 10 are met.

← 2. In Mexico, a regulatory impact calculator was introduced in 2010, as part of a broader set of regulatory policy reforms, allowing regulators to identify potential impacts of their draft regulation. This is a software tool consisting of ten questions to determine the type of RIA to be conducted.