This chapter describes trends in assets under management by investors considering sustainability in portfolio selection, as well as asset manager sustainability-related engagement preferences. The chapter summarises the most commonly used sustainability reporting standards and presents their use by listed companies, including whether disclosed information is assured by a third party. It then analyses the market value of companies in industries where climate change is financially material. In addition, the chapter gives an overview of how the purpose of the corporation has been understood and the definition of directors’ fiduciary duties in selected jurisdictions. Finally it reviews how shareholders and stakeholders have been influencing management to incorporate climate‑related matters into their decision-making processes.

Climate Change and Corporate Governance

1. Trends

Abstract

1.1. Climate change and the Paris Agreement

Copious scientific evidence points to the fact that human-generated emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) such as CO2 and methane have caused approximately 1.0ºC of global warming above pre‑industrial levels (IPCC, 2021[1]). Moreover, research demonstrates that global warming is associated with more frequent flooding, loss of biodiversity, heat-related mortality, among other risks to human life, the environment and the economy. These risks are considered moderate or high in a scenario where global warming is 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels, which would mean that some adaptation in our societies, infrastructure and industrial systems would be needed to cope with global warming. However, risks become high or very high for average temperatures of 2ºC or higher above pre‑industrial levels, which would inflict severe impact on our societies with limited capacity to adapt (IPCC, 2018[2]). This is why 192 governments agreed to hold global warming to “well below 2ºC above pre‑industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels” (UN, 2015, p. 3[3]), in what is known as the “Paris Agreement”.

To limit global warming to 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels would effectively require CO2 emissions to decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero emissions around 2050 (IPCC, 2018[2]). The “net zero” means that CO2 emissions would still exist at low levels (including natural sources of CO2), but they would be compensated by the removal and storage of CO2 from the atmosphere (in this scenario, non-CO2 GHG emissions would be reduced but they would not reach zero globally). So far, 165 jurisdictions have presented a national plan on how they will reduce GHG emissions in line with the Paris Agreement (so-called “nationally determined contributions”), but their planned combined emissions reductions by 2030 still fall short of the level needed to limit global warming to 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels (UN, 2021[4]). In particular, the total level of global GHG emissions in the existing nationally determined contributions of Parties to the Paris Agreement is projected to be 15.9% higher in 2030 than in 2010 and 4.7% higher than in 2019 (UN, 2021[5]).

During COP26 in November 2021, governments agreed on the Glasgow Climate Pact to accelerate action on coal, deforestation, electric vehicles and methane, and they finalised the outstanding elements of the Paris Agreement, including the establishment of a new mechanism and standards for international carbon markets (UN, 2021[6]). In the Glasgow Climate Pact, governments agreed to revisit and strengthen their current GHG emissions targets to 2030 in 2022, instead of waiting another 5‑year period as established by the Paris Agreement. Likewise, 190 countries agreed to phase down unabated coal power, 137 countries committed to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, and over 100 countries pledged to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

There are many different pathways to net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, and a great number of possible energy and environmental policies to support them. These might include, for instance, mandating the phase‑out of coal-fired power stations, subsidies to renewable energy, financing technology innovation and emission trading systems for major polluters. A discussion of the advantages and drawbacks of each of those policies is outside of the scope of this report, but, as an example of the economic changes that lie ahead, the following are some of the transformations included in a global pathway to net zero emissions by 2050 set by the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2021[7]):

annual additions of 630 GW of solar photovoltaics and 390 GW of wind by 2030 (four times the record levels in 2020)

electric vehicles would represent more than 60% of car sales by 2030 (currently, they have a market-share of around 5%)

in 2050, almost half the GHG emissions reduction will come from technologies that are currently at the demonstration or prototype phase, including innovation related to batteries, hydrogen, and CO2 capture and storage

fossil fuels decline from almost four‑fifths of total energy supply today to slightly over one‑fifth by 2050

90% of heavy industrial production becomes low-emissions by 2050, including with the use of hydrogen and CO2 capture technologies.

The Paris Agreement also sets out that implementation will require economic and social transformation based on the best available science. The preamble to the Paris Agreement reflects the close links between climate action, sustainable development, and a just transition, with Parties “taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities” (UN, 2015, p. 2[3]).

1.2. Investors’ perspective

Asset owners such as pension funds and families have taken notice of the risks and opportunities that climate change and an expected transition to net zero emissions by 2050 (among other environmental and social trends) might represent for their investee assets. Consequently, the total assets under management by professional investors that consider ESG risk factors in portfolio selection and management has grown significantly. While the definition of sustainable investment varies between countries and over time, Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1 provide an indicative snapshot of the growing global importance of sustainable investing assets.1

Table 1.1. Snapshot of global sustainable investing assets

In USD billions

|

|

2016 |

2018 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

United States |

8 723 |

11 995 |

17 081 |

|

Europe |

12 040 |

14 075 |

12 017 |

|

Japan |

474 |

2 180 |

2 874 |

|

Canada |

1 086 |

1 699 |

2 423 |

|

Australia and New Zealand |

516 |

734 |

906 |

|

Total |

22 839 |

30 683 |

35 301 |

Note: Significant changes in the way sustainable investment is defined have been adopted in Australia, Europe and New Zealand, so direct comparisons across regions and time are not easily made.

Source: GSI Alliance (2021[8]), Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020, http://www.gsi-alliance.org/.

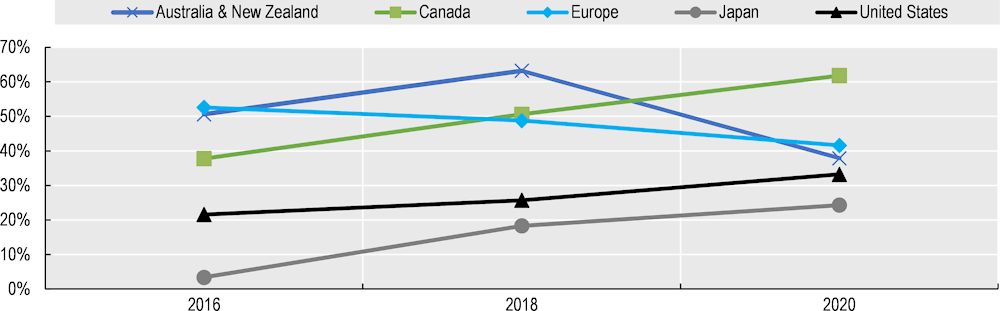

Figure 1.1. Proportion of sustainable investing assets relative to total managed assets

Note: Significant changes in the way sustainable investment is defined have been adopted in Australia, Europe and New Zealand, so direct comparisons between regions and years are not easily made.

Source: GSI Alliance (2021[8]), GSI Alliance, Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, http://www.gsi-alliance.org/.

Since most of the sustainable investing data rely on survey-based approaches, the large numbers above should be taken with caution because part of the value of sustainable investing assets may be attributed to asset managers who claim to adopt sustainable or ESG-conscious strategies but who do not necessarily contribute to more social and environmental sustainability. This could be either due to misleading investors when labelling a financial product (including so-called “greenwashing”) or because the mandated goals of an investor are not aligned with what the best scientific evidence would recommend. One clear conclusion can be extracted from the numbers above: asset owners such as pension funds and households in Canada, the United States and Japan have increasingly allocated their portfolios to investment vehicles that purport to be sustainable. In Europe, Australia and New Zealand, it is difficult to draw any conclusion on trends between 2016 and 2020 because of changes in the definition of sustainable investment during that period, but the proportion of sustainable investing assets relative to total managed assets in 2020 was high (above 37%) (GSI Alliance, 2021[8]).

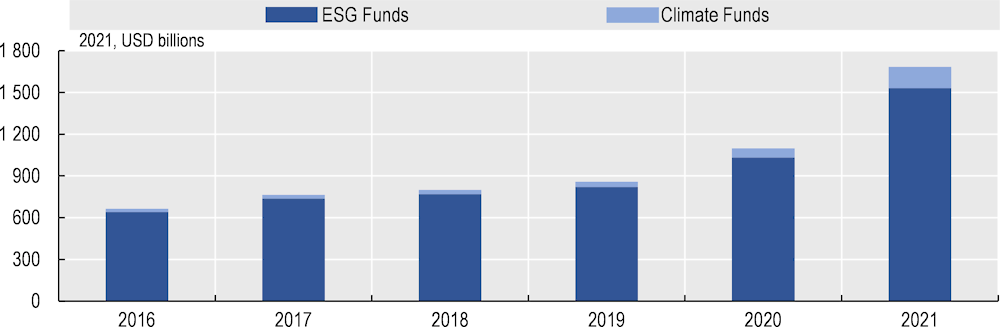

A relatively small subset of the sustainable investing universe is composed of investment funds that label themselves as ESG or sustainable funds – for instance by including “ESG” or “sustainable investing” terms in their names. Focussing only on investment funds, and using a different database than in Table 1.1, shows a strong growth in assets under management for these ESG funds2, which reached USD 1.7 trillion in 2021 (Figure 1.2). This was mainly the result of record net inflow amounts in 2020 and 2021 with USD 241 billion and USD 586 billion, respectively. While the value of assets under management by climate funds was very modest between 2016 and 2019, net inflows in 2020 and 2021 were 6 and 19 times that of the previous three year average (2017‑19), respectively.

Figure 1.2. Assets under management of funds labelled as or focusing on ESG and climate

Note: Funds retrieved from Reuters Funds Screen classified as Climate Funds or ESG Funds in the case their names contain, respectively, climate or ESG relevant acronyms and words such as ESG, sustainable, responsible, ethical, green and climate (and their translation in other languages). Funds without any asset value are excluded.

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon, Datastream, OECD calculations.

While the numbers in Table 1.2 involve the same challenges of categorisation previously mentioned, the following features of the current sustainable investing universe can still be identified:

the most significant strategy (with USD 25 trillion) is the integration by asset managers of ESG factors into their financial analysis;

strategies that often accept a tangible trade‑off between wealth creation and better ESG results (“Impact/community investing”) currently amount to USD 352 billion3 (only 1.4% when compared to the “ESG integration” strategy);

assets under management by investors who claim to employ shareholder power to influence corporate behaviour on ESG-related issues has reached a meaningful value of USD 10.5 trillion.4

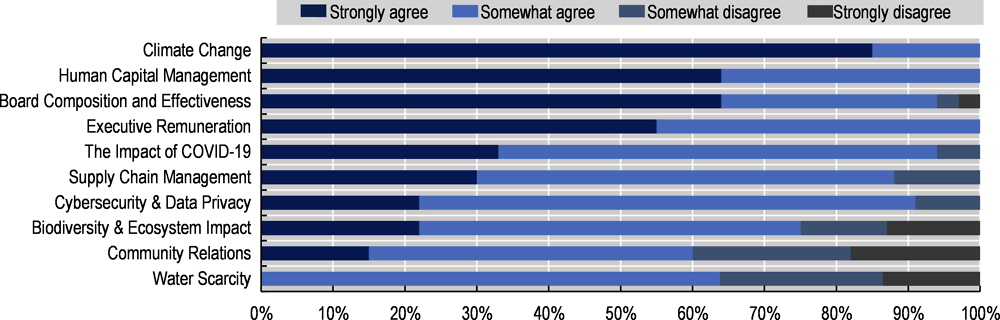

As acknowledged at the outset of this section, sustainable investing is a wide category that encompasses ESG issues of very different nature, from climate change to human rights. Figure 1.3 shows the current engagement preferences of a sample of institutional investors (investors not necessarily self-reported as “sustainable investors” with USD 29 trillion in assets under management). The sample (with some overrepresentation of UK-based investors) shows clearly that climate change and associated risks are the number one priority with respect to engagement with companies, followed by human capital management (a social issue), board composition and executive remuneration (governance issues).

Table 1.2. Sustainable investing assets by strategy in 2020

|

Sustainable investment strategy |

Definition |

Assets (USD billions) |

|---|---|---|

|

ESG integration |

The systematic and explicit inclusion by investment managers of ESG factors into financial analysis. |

25 195 |

|

Negative screening |

The exclusion from a portfolio of certain sectors, companies, countries or other issuers based on activities considered not investable (e.g. excluding tobacco companies). |

15 030 |

|

Corporate engagement and shareholder action |

Employing shareholder power to influence corporate behaviour, including through proxy voting that is guided by comprehensive ESG guidelines. |

10 504 |

|

Norm-based screening |

Screening of investments against minimum standards of business practice based on international norms such as those issued by the UN, ILO and OECD. |

4 140 |

|

Sustainability-themed investing |

Investing in themes or assets specifically contributing to sustainable solutions (e.g. sustainable agriculture and gender equity). |

1 948 |

|

Best-in-class screening |

Investment in sectors or companies selected for positive ESG performance relative to industry peers, and that achieve a rating above a defined threshold. |

1 384 |

|

Impact/community investing |

Investing to achieve positive social and environmental impact. |

352 |

Note: Asset managers may apply more than one strategy to a given pool of assets, so there is double‑counting if one adds all strategies above. For information on the total of sustainable investing assets in 2020, please see Table 1.1.

Source: GSI Alliance (2021[8]), Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020, http://www.gsi-alliance.org/.

Figure 1.3. Institutional investor engagement preferences in 2020

Note: 42 global institutional investors (not necessarily self-reported as “sustainable investors”) with USD 29 trillion in assets under management (with nearly two‑thirds of their portfolio in equity) participated in the survey. The geographical distribution of those investors was the following: UK (33%); the United States (17%); Europe excl-UK (12%); rest of the world (38%).

Source: Morrow Sodali (2021[9]), Institutional Investor Survey 2021, https://morrowsodali.com/insights/institutional-investor-survey-2021.

1.3. Financial stability

Financial stability supervisors currently also have climate change at the top of their sustainability agenda, since a great number of firms may become unable to pay their debt or their assets may quickly lose value depending on the consequences of climate change on their businesses and management’s capacity to grapple with climate‑related risks. Climate‑related risks are usually classified under two categories (TCFD, 2017, p. 62[10]): (i) physical risks, which result either from extreme weather events or long-term shifts in climate patterns (e.g. flooding and higher temperatures); (ii) transition risks, which are associated with changes in public policies, legal actions, a shift to low-carbon technologies, market responses to climate change and reputational considerations (e.g. carbon pricing policies and decrease in the sales of internal combustion engine vehicles).

The FSB, within its mandate to promote international financial stability, has been leading work on how climate‑related risks might impact the financial system. One of the most consequential outcomes of the FSB’s work was the establishment in 2015 of an industry‑led Task Force on Climate‑related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The initial goal of the TCFD was to develop a set of voluntary disclosure recommendations for use by companies in providing decision-useful information to investors, lenders and insurance underwriters about the climate‑related financial risks that companies face (the main recommendations issued in 2017 are summarised below).

Another initiative, among many others, is the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), which brings together 114 institutions and whose purpose is to contribute to the development of climate‑ and environment-related risk management and mobilise mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy. NGFS member jurisdictions cover more than 2/3 of the global systemically important banks and insurers. In 2019, the NGFS issued six recommendations to financial supervisors and relevant stakeholders to foster a greener financial system, including one related to “achieving robust and internationally consistent climate and environment‑related disclosure” (NGFS, 2019[11]).

1.4. Reporting frameworks and standards

Today, companies use a great number of frameworks and standards to disclose information on their climate‑related and other ESG performance, risks and strategy. Table 1.3 summarises the most frequently used frameworks and standards5 with respect to how detailed they are, their targeted audience, the issues they cover and the threshold they recommend for information to be disclosed (i.e. which issues would be material for the framework). Possible definitions of “materiality” are discussed in more detail further below, but, concisely, corporate disclosure is “financially material” if it could reasonably be expected to influence an investor or a lender’s analysis of a company’s future cash flows. A “double materiality” concept incorporates what is financially material, but it also includes within its scope information that would be relevant to the understanding of multiple stakeholders of a company’s effect on the environment, on people or on society (e.g. for consumers and employees).

Table 1.3. Climate‑related and other ESG reporting frameworks and standards

|

Institution |

System |

Level of detail |

Materiality |

Audience |

Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TCFD recommendations |

Principles-based1 |

Financially material |

Investors, lenders and insurance underwriters |

Climate‑related issues |

|

|

IFRS Foundation – International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB)2 |

IFRS Sustainability Standards2 |

Detailed information |

Financially material |

Investors |

Initial focus on climate‑related issues, but with a plan to cover a great number of ESG issues |

|

Value Reporting Foundation – SASB Standards Board3 |

SASB Standards |

Detailed information |

Financially material |

Investors |

A great number of ESG issues, with subset of standards in each of 77 industries |

|

Value Reporting Foundation – Integrated Reporting Framework Board3 |

Framework |

Principles-based |

Financially material |

Investors |

A great number of ESG issues |

|

GRI Standards |

Detailed information |

Double materiality |

Multiple stakeholders |

A great number of ESG issues, with a plan to have a subset of standards in each of 40 sectors |

|

|

GHG Protocol Corporate Standards |

Detailed information |

‑4 |

‑4 |

GHG emissions4 |

|

|

CDP (previously “Carbon Disclosure Project”) |

CDP’s questionnaires5 |

Detailed information |

‑5 |

Investors and customers |

Climate change, forests and water security5 |

|

CDSB Framework |

Principles-based |

Financially material and relevant7 |

Investors |

Climate and other environmental information |

Notes:

1: While TCFD’s recommendations (TCFD, 2017[10]) are indeed principles-based, the Task Force has published a number of documents providing detailed guidance on how to better comply with its recommendations, such as the report “Guidance on Scenario Analysis for Non-Financial Companies” (TCFD, 2020[12]). To some extent, therefore, this set of recommendations and guidance documents on how companies may disclose financially material information, preferably in mainstream financial filings, would together demand “detailed information” according to the classification in the third column of this table.

2: IFRS Foundation announced in November 2021 the formation of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which will sit alongside the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), to set IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. As a part of this, IFRS Foundation committed to consolidate with the Value Reporting Foundation Board and CDSB by June 2022. IFRS Foundation’s recently amended constitution provides that IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards “are intended to result in the provision of high-quality, transparent and comparable information […] in sustainability disclosures that is useful to investors and other participants in the world’s capital markets in making economic decisions” (item 2.a). Please see section 2.4 on ISSB’s goals and planned work.

3: SASB Standards Board and Integrated Reporting Framework Board ( Framework Board) merged in June 2021. Currently, both standard-setting boards are supervised by a newly created organisation called Value Reporting Foundation Board (VRF). In November 2021, the VRF committed to consolidate into the recently created ISSB by June 2022.

4: GHG Protocol’s corporate accounting and reporting standard provides requirements and guidance for companies preparing a corporate‑level GHG emissions inventory. It does not adopt a materiality concept, and other ESG reporting frameworks and standards will typically either require or allow GHG emissions to be disclosed according to GHG Protocol’s standard. In this standard, GHG emissions are classified under three categories: Scope 1 (direct emissions from a company’s own operations); Scope 2 (emissions from purchased or acquired electricity, steam, heat and cooling); Scope 3 (the entire chain of emissions impact from the goods the company purchases to the products it sells).

5: CDP’s questionnaires would not be considered a reporting framework or standard in the traditional sense, but the institution offers a widely used system for companies to answer to any of the following questionnaires: Climate Change; Forests; Water Security. The questionnaires are meant to be disclosed to (i) investors or to (ii) customers interested in assessing the environmental impact of their supply-chain. Corporate management is not supposed to make a materiality assessment of the information to disclose, because CDP offers a set of questions by economic sector and companies have strong incentives to answer all of them in order to receive better scores calculated by CDP’s system. Questionnaires are shortened only for companies with an annual revenue of less than EUR/USD 250 million and corporates answering the questionnaire for the first time.

6: In January 2022, the CDSB consolidated into the IFRS Foundation.

7: According to the CDSB Framework, environmental information should be disclosed if financially material or relevant. “Relevant” in this context would be information that might be financially material at some point, while the link between the information and future cash flows is not evident. In either case, GHG emissions shall be reported in all cases regardless of management’s assessment of their materiality or relevance (CDSB, 2019[13]).

Source: Standards, frameworks and websites of the institutions visited in July and November 2021 and January 2022; OECD elaboration.

For a company that is choosing which reporting framework to use or for a regulator that is considering whether to recommend or require a particular framework, a first question could be which broad issues are the most relevant to the company and to the market (last column in Table 1.3). For instance, TCFD recommendations cover climate‑related risks only, while the SASB Board and GSSB offer reporting standards on a full breadth of ESG issues. Therefore, for example, if climate‑related risks are the most material risks in a specific context, compliance with the TCFD recommendations might be more relevant to initially focus on, before considering whether to report on other environmental and social dimensions, using SASB or GRI reporting standards for instance.

Another question for companies and regulators assessing existing ESG reporting frameworks is who would be the primary users of the information to be disclosed (the fifth column in Table 1.3). A large majority of existing ESG reporting frameworks cite investors in equity and debt as their main audience with the notable exceptions of the GRI Standards, which aim at being used by shareholders and multiple stakeholders, and CDP’s questionnaires, which have both investors and supply chain customers as their audience. A focus on the information needs of existing and potential investors and lenders has been traditionally adopted by financial reporting standards (IASB, 2018[14]). However, as important as the definition of the main audience of the disclosure may be, the disclosed information might still be relevant to users that are not considered primary. For instance, CO2 emissions will likely be relevant to shareholders of an oil and gas company as primary users due to the potential cash flow impact of carbon pricing policies in the future, but it may also be of interest to consumers or environmentally conscious employees who would prefer to work in a low-carbon company.

The definition of materiality in an ESG disclosure framework or standard goes largely hand in hand with the profile of its primary users (fourth column in Table 1.3). If the primary users are investors, it is often assumed that they make investment and voting decisions mostly based on a company’s expected future cash flows and their timing. Only the CDSB Framework – which focuses only on environmental and climate change information and considers investors as the primary users – somewhat diverges from this general rule in two ways: (i) by requiring disclosure of information even if its impact on a company’s cash flows is not evident but could become relevant; (ii) by mandating transparency of GHG emissions in all cases regardless of management’s assessment of its materiality.

ESG reporting frameworks and standards summarised in Table 1.3 also vary with respect to the level of detail of their guidance and requirements (see third column). Some of them are principles-based, which allows for flexibility when implemented by companies with different characteristics and operating in different countries. Flexibility, however, makes consistency across time and comparability between companies more difficult, which is why some ESG reporting standards provide greater detail on how companies should account and report on sustainability information.

Two additional features of ESG reporting should be highlighted. First, companies may choose to report sustainability information based on two different standards with similar coverage of issues, as long as they clearly segment the disclosed information (for instance, according to SASB for investors and GRI standards for a wider public). Second, a principles-based framework may serve as the overall guidance to management when reporting sustainability information according to a more detailed standard (for instance, using the Framework when developing a sustainability report with information required by SASB Standards).

TCFD recommendations receive particular attention in this report because of their focus on climate‑related risks. The Task Force’s recommendations suggest the disclosure of financially material information, preferably in mainstream financial filings, around four thematic areas (TCFD, 2017[10]):

Governance – the organisation’s governance around climate‑related risks and opportunities

Strategy – the actual and potential impacts of climate‑related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy and financial planning. This would include impact analysis of different climate‑related scenarios, including a 2ºC or lower scenario in line with the Paris Agreement

Risk management – the processes used by the organisation to identify, assess and manage climate‑related risks

Metrics and targets – the metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate‑related risks and opportunities, including greenhouse gas emissions.

While TCFD recommendations are principles-based, the Task Force has published a number of documents providing detailed guidance on how to better comply with its recommendations, such as the report “Guidance on Scenario Analysis for Non-Financial Companies” (TCFD, 2020[12]). To some extent, therefore, these recommendations and guidance would together demand “detailed information” according to the classification in the third column of Table 1.3.

TCFD analysis of the implementation of its standard shows uneven progress to date. Its 2021 analysis of 1 651 public companies from 69 countries across eight industries particularly exposed to climate‑related risks6 over the previous three years assessed whether their reports included information that appeared to align with the Task Force’s 11 recommended disclosures, which are organised around the four thematic areas mentioned above (TCFD, 2021, pp. 28, 30[15]). Despite some recent progress, the conclusion of the analysis is that only 50% of companies reviewed disclosed information in alignment with at least three recommended disclosures. The information item most often disclosed by companies was “climate‑related risks and opportunities” (52% of companies in 2020) and the least disclosed item was “resilience of strategies under different climate‑related scenarios” (13% of companies in 2020). Among the four thematic areas, “governance” is the one with the smallest uptake: its two recommended disclosures are the second and third least disclosed. In 2020, Europe remained the leading region for TCFD-aligned disclosures (a company headquartered in Europe disclosed on average 50% of the 11 recommended disclosures), while the disclosure rate was 34% in the Asia Pacific, 26% in Latin America, 22% in the Middle East and Africa, and 20% in North America (TCFD, 2021, p. 34[15]).7

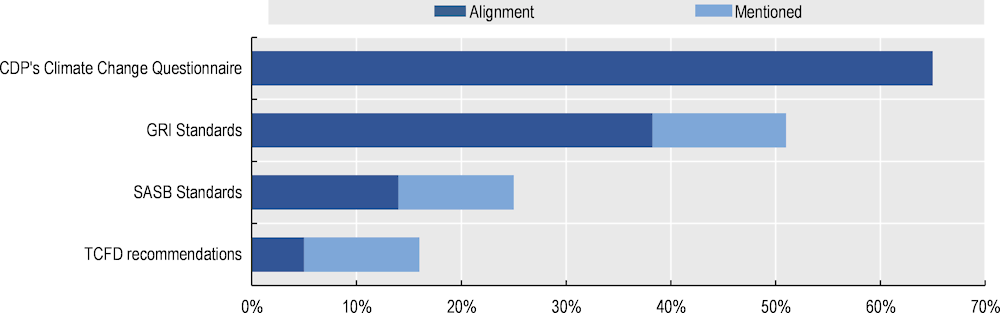

The multitude of existing standards and frameworks (seven in Table 1.3) raises the question of whether climate‑related information is comparable between companies that effectively disclose them. Figure 1.4 presents the use of four abovementioned ESG standards and frameworks by S&P 500 companies that published a sustainability report in 2019 (90% of the large‑cap index companies published such a report).

Figure 1.4. Use of ESG reporting standards by S&P 500 companies in 2019

Notes:

1: Use of ESG reporting standards and frameworks was classified in the analysis as purported “alignment” with the standard or simply as having “mentioned” the standard in the sustainability report.

2: Some sustainability reports from S&P 500 companies followed or mentioned more than one ESG reporting standard in their sustainability report. This is the reason why the percentages in this graph add up to more than 100%.

Source: G&A Institute (2020[16]), Trends on the sustainability reporting practices of S&P Index companies, https://www.ga-institute.com/research-reports/flash-reports/2020-sp-500-flash-report.html.

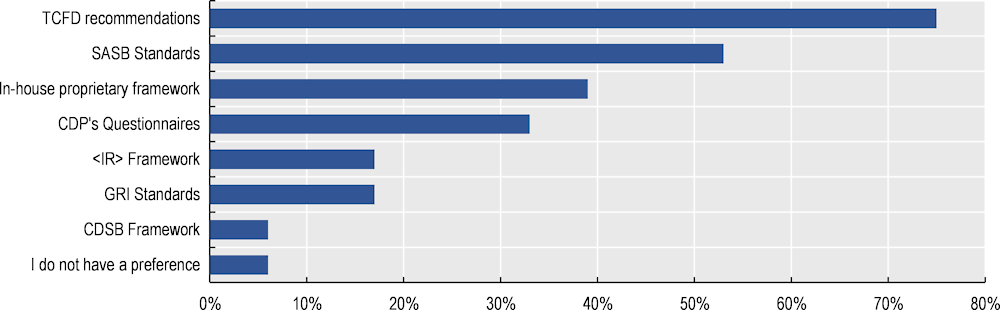

Conscious of the challenges posed by a multiplicity of ESG frameworks and standards, a majority of the institutions listed in Table 1.3 (SASB Standards Board, GSSB, Framework Board, CDSB and CDP) initiated in 2018 a project to achieve the highest possible alignment between their frameworks and standards with respect to climate‑related reporting, while recognising that those institutions may have different objectives (Corporate Reporting Dialogue, 2019[17]). The same group of institutions also published in 2020 a prototype for climate‑related financial disclosures building on their own reporting systems and TCFD recommendations, which is intended to be a starting point for the development of a harmonised global standard (2020[18]). While overlaps and conflicting requirements between ESG reporting standards and frameworks are not assessed in this report, Figure 1.5 shows that investors do have clear preferences for some ESG standards, which may suggest that existing standards are indeed significantly different.

Figure 1.5. Institutional investor ESG reporting preferences in 2020

Notes:

1: For information on respondents to the survey, see notes to Figure 1.3.

2: Respondents to the survey could choose more than one preferred ESG framework, what explains why the numbers in this figure add up to more than 100%. Specifically, the survey found that a number of institutional investors, including BlackRock, State Street Global Advisors and Vanguard, have called out TCFD recommendations and SASB Standards as the two ESG frameworks that listed companies should follow.

Source: Morrow Sodali (2021[9]), Institutional Investor Survey 2021, https://morrowsodali.com/insights/institutional-investor-survey-2021.

The use of multiple sustainability-related and ESG reporting standards and frameworks is not, however, the only barrier to greater consistency and comparability of corporate sustainability disclosure. If disclosed ESG information is not assured by a third-party based on robust methodologies (as financial reports of listed companies must typically be), it could undermine confidence in the information disclosed and the possibility to compare sustainability reports between companies. In 2019, only 29% of S&P 500 companies that reported on sustainability sought external assurance.8 Moreover, just 5% of those assurances were in relation to the entire sustainability report and in 40% of cases they certified only information on GHG emissions (G&A Institute, 2020[16]).

A global analysis of 1 400 large listed companies in 22 major jurisdictions9 found that 91% of companies reported some level of sustainability information, and that 51% of those that disclosed sustainability information in 2019 provided some level of assurance by a third party (44% for those based outside the EU). Eighty-three percent of these assurance engagements, however, resulted in only “limited” assurance reports. The remaining small minority offered a higher level of “moderate” or “reasonable” assurances (IFAC and AICPA, 2021[19]).

1.5. Companies’ perspective

Another important consideration is the number and market value of public companies in industries where either GHG emissions or the physical impacts of climate change are indeed financially material. One way of evaluating this is to identify listed companies that operate in industries where GHG emissions, energy management and the physical impacts of climate change are considered to be financially material according to the SASB Sustainable Industry Classification System® Taxonomy (SASB mapping),10 which is set by the SASB Board through a process of research and public consultation.11

In the SASB mapping, 51 out of 77 industries are considered to face financially material risks related to Scopes 1 and 2 GHG emissions12 (in the classification used in Table 1.4, “energy management” is closely related to GHG Scope 2 emission risks) as well as the physical impacts of climate change. The number of companies and their market capitalisation in those 51 industries (11 sectors encompass all those industries) are presented in Table 1.4.13

Table 1.4. Companies in sectors where GHG emissions, energy management and physical impacts of climate change are likely to be financially material in 2021

|

Sector |

Number of companies |

Market capitalisation (USD billion) |

|---|---|---|

|

Technology & Communications |

3 735 |

24 782 |

|

Resource Transformation |

5 637 |

11 732 |

|

Extractives & Minerals Processing |

3 859 |

9 934 |

|

Transportation |

1 634 |

9 326 |

|

Food & Beverage |

2 696 |

6 756 |

|

Consumer Goods |

1 967 |

6 683 |

|

Infrastructure |

2 365 |

5 031 |

|

Financials |

722 |

3 758 |

|

Health Care |

585 |

2 028 |

|

Services |

751 |

933 |

|

Renewable Resources & Alternative Energy |

406 |

914 |

|

Total |

24 357 |

81 878 |

Notes:

1: Sector classification is according to SASB mapping.

2: According to the SASB mapping, Physical Impacts of Climate Change is classified under the dimension of “Business Model & Innovation”.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Thomson Reuters Eikon, Bloomberg, SASB mapping and OECD calculations.

Table 1.5. Share of market capitalisation where selected risks are likely to be financially material by sustainability issues in 2021

|

Sustainability Issues |

Share of market capitalisation of industries where the risk is material (in total global market cap.) |

Number of industries where the risk is material (out of a total of 77) |

|---|---|---|

|

Energy Management |

47% |

33 |

|

GHG Emissions |

27% |

25 |

|

Water & Wastewater Management |

26% |

25 |

|

Waste & Hazardous Materials Management |

21% |

19 |

|

Air Quality |

15% |

17 |

|

Ecological Impacts |

9% |

14 |

|

Physical Impacts of Climate Change |

6% |

8 |

Note: Sector classification is according to SASB mapping.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Thomson Reuters Eikon, Bloomberg, SASB mapping and OECD calculations.

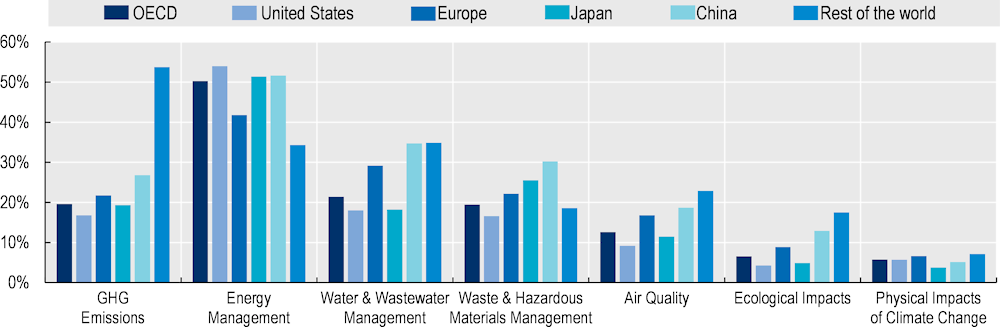

On top of GHG emissions, energy management and physical impacts of climate change, sustainability issues also relate to other environmental, social and governance topics.14 In order to have a broader perspective on the risks relating to the environment, Table 1.5 presents the share of market capitalisation of companies in sectors where environmental issues are likely to be financially material as a percentage of total global market capitalisation. The table also shows the corresponding number of industries according to the SASB mapping.

According to the SASB mapping, “energy management”, which is closely related to GHG Scope 2 emissions, is an environmental risk that is likely to be financially material for 33 out of 77 industries that account for half of the global market capitalisation in 2021. In addition, 25 industries that represent a quarter of the global market capitalisation are associated with GHG emissions (Scope 1) risks. On top of that, 6% of the global market capitalisation across eight industries are materially exposed to the physical impacts of climate change. Taking these three risks together, climate change is considered to be a financially material risk for listed companies that account for 65% of the global market capitalisation of all listed companies today.

Table 1.5 cannot be read as the market value adjusted for specific risks, which would depend on an individual assessment of each company’s financial exposure to these risks. For instance, a company with a sound strategy to navigate the transition to a low-carbon economy may face low risks despite the fact it is in a high climate‑related financial risk industry such as metals and mining. However, in the absence of disclosure of comparable value‑at-risk information by a representative sample of companies, the share of market capitalisation in Table 1.5 and in Figure 1.6 can serve as a reference to policy makers on how differences in economic sectors’ distribution among local listed companies may justify distinct priorities when supervising and regulating their capital markets.

In line with the global distribution of companies in terms of environmental risks, companies in sectors where energy management (Scope 2) is considered a financially material risk have the highest share of market capitalisation across jurisdictions (Figure 1.6) – in particular, more than 50% of the market capitalisation of the US, Japanese and Chinese markets. In absolute terms, the US listed corporate sector is also highly exposed to the rest of the selected sustainability risks, while their share by market capitalisation is among the lowest in comparison to other countries and regions shown in Figure 1.6. The opposite trend is true for the rest of the world: while the market capitalisation of companies in sectors likely to be exposed to the selected sustainability risks is relatively low, their share in relation to total market capitalisation is comparatively higher.

Figure 1.6. The share of market capitalisation by selected risks, 2021

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Thomson Reuters Eikon, Bloomberg, SASB mapping, and OECD calculations.

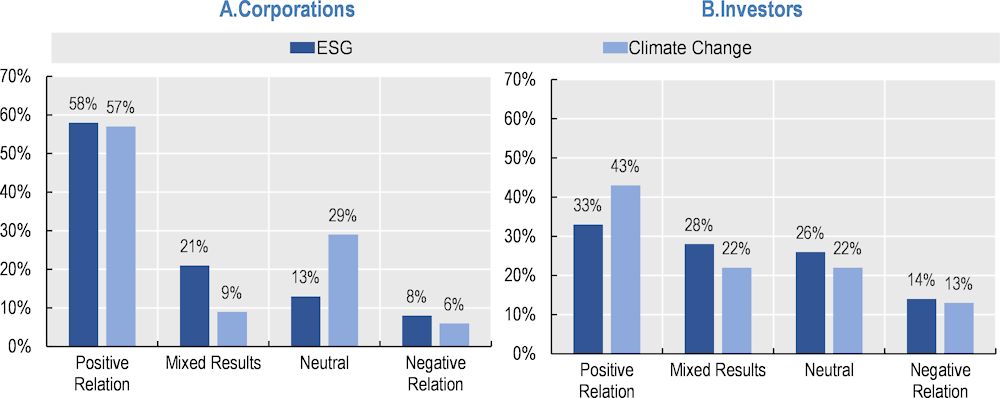

Another central question concerning corporate sustainability is whether better ESG practices could enhance financial performance and resilience, for instance through improved risk management and better strategy.

A large volume of research suggests that the better the level of company ESG practices, the higher their financial performance,15 albeit with some divergence in findings. A 2021 paper published by NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management reviewed the findings of 245 research papers issued between 2015 and 2020 (Wheelan et al.[20]). The review concludes that 58% of the papers found a positive correlation between ESG practices (such as suggested by high ESG ratings) and operational and financial metrics (such as return on equity, return on assets and stock prices). In 21% of the papers, there were mixed results (the same study found positive, neutral or negative results), 13% did not find a clear relationship and only 8% showed a negative relationship.16

The meta‑analysis found a weaker relation between investors’ focus on ESG risks and the performance of their portfolios. In reviewed studies looking from an investor’s perspective, 33% showed better performance for securities portfolios with a purported focus on ESG risks taking into account their risk-adjusted returns (such as a Sharpe ratio), in 28% the results were mixed, in 26% a clear relationship was not identified and 14% found negative results.

It is important to note that many of the studies reviewed faced methodological challenges such as the low standardisation of ESG data and lack of emphasis of some investment vehicles on financially material issues, which may limit the conclusiveness of their results (Wheelan et al., 2021[20]). Moreover, some other empirical evidence suggests that better financial and investment performance is also correlated with the governance aspect specifically – the G in ESG, company fundamentals, and the size and geographical location of the company (S&P Global, 2019[21]; Belsom and Lake, 2021[22]; Ratsimiveh et al., 2020[23]; Boffo and Patalano, 2020[24]).

Figure 1.7. Studies focussing on the relation between ESG and performance

Source: Wheelan et al. (2021[20]), ESG and Financial Performance, https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/NYU-RAM_ESG-Paper_2021%20Rev_0.pdf.

Firm size is one of the factors explaining the positive relation between ESG practices and the financial performance of companies (Ratsimiveh et al., 2020[23]). Larger firms tend to perform better financially, for instance due to economies of scale, and, because they have relatively more resources available, they may also adopt policies and practices that help them increase their ESG scores. Table 1.6 presents size and performance indicators of 7 801 listed companies around the world17 that have an ESG score from Refinitiv, with the median ESG score taken as a threshold to classify companies either as low or high scoring.

Table 1.6. Size and performance indicators for companies by ESG score

|

Average of 2017‑21 |

Low ESG scored companies |

High ESG scored companies |

|---|---|---|

|

ESG Score (out of 100) |

26 |

56 |

|

Market capitalisation (USD billion) |

1.2 |

4.4 |

|

ROE (%) |

3.6 |

4.6 |

|

ROA (%) |

8.7 |

10.6 |

Note: Companies without market capitalisation, ROE and ROA are excluded from the analysis. Indicators for each company are calculated as a 5‑year average whenever available. The values presented in the table are median of the indicators within each ESG scored category. ESG Score refers to Refinitiv ESG Score retrieved from Thomson Reuters Eikon public companies data. The score is calculated based on the methodology designed by Refinitiv and defined as an overall score based on the publicly reported information in the environmental, social, and corporate governance pillars. For more information on methodology, please see here.

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon, Datastream, OECD calculations.

As presented in Table 1.6, companies with higher ESG scores are on average larger in terms of market capitalisation than the ones with lower scores, both for the entire dataset and for individual sectors. This relation holds also with respect to performance indicators of return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) for the entire dataset, however, for some of the sectors, such as consumer non-cyclicals, financials, industrials and utilities, performance in terms of ROE does not seem to differ much between low and high ESG scored companies.

Despite some divergence in research findings about the business case for better ESG practices, companies’ attention to and disclosure on sustainability issues have become increasingly visible. This can be seen not only in the high number of companies that report on sustainability (as mentioned in Section 1.4), but also in the adoption of ESG metrics in executive compensation plans. While most of the components of executive remuneration plans are still linked to financial measures, companies have begun to integrate ESG-related metrics in their plans. Globally, executive compensation plans were linked to performance measures in 90% of the 9 000 largest companies with almost USD 104.5 trillion market capitalisation18 as of the end of 2021 (i.e. part of executives’ remuneration is variable). Thirty percent of companies with performance‑linked executive remuneration use ESG-linked performance measures in their plans. The data also shows a high correlation between the ESG scores of companies and the use of ESG performance measures.

Table 1.7. Executive compensation plans with ESG performance measures in 2021

|

ESG scores |

Companies with policy executive compensation plans (number of companies) |

share of ESG performance measures |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

with performance measures |

with ESG performance measures |

||

|

0‑25 |

1 545 |

182 |

12% |

|

25‑50 |

3 224 |

728 |

23% |

|

50‑75 |

2 650 |

1 081 |

41% |

|

75‑100 |

771 |

505 |

65% |

|

Total |

8 190 |

2 496 |

30% |

Note: ESG Score refers to Refinitiv ESG Score retrieved from Thomson Reuters Eikon public companies data. The score is calculated based on the methodology designed by Refinitiv and defined as an overall score based on the publicly reported information in the environmental, social, and corporate governance pillars. For more information on methodology, please see here.

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon, OECD calculations.

A more detailed analysis of company specific executive pay applications in terms of ESG metrics among FTSE 10019 companies shows that in around 30% of companies, targets relating to long-standing ESG metrics are integrated into executives’ compensation plans. Importantly, half of those ESG targets relate to risks that are not material to the company according to the risk classification of the SASB mapping. In only half of the FTSE 100 companies with ESG targets in their executives’ compensation plans, output measures are in the form of quantifiable goals such as GHG emission reductions or carbon emissions targets (Gosling et al., 2021[25]). This may explain why the UK Investment Association – which represents asset managers – wrote to the FTSE 350 Remuneration Committee chairs in November 2021, setting out that ESG factors in the company’s variable remuneration should be “quantifiable and clearly linked to company strategy” (The Investment Association, 2021[26]).

An additional initiative aimed at supporting companies’ efforts to put climate change objectives into practice through more specific GHG emission reduction targets is the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), supported by the CDP, the United Nations Global Compact and others to provide guidance to companies on how to set targets in line with what the latest climate science deems necessary to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. SBTi recommends a five‑step process: the company i) submits a letter establishing its intent to set a science‑based target; ii) develops an emissions reduction target in line with the SBTi’s criteria; iii) presents its target to the SBTi for official validation; iv) announces the validated target to its shareholders and stakeholders; v) discloses company-wide emissions in line with the GHG Protocol guidelines and tracks target progress annually (Science Based Targets Initiative, 2021[27]).

1.6. A corporation’s objective

A significant portion of the academic and public debate on corporations during the last 50 years has been largely based on two assumptions: (i) equity investors have the sole goal of maximising their financial returns relative to a risk they are willing to accept; (ii) companies’ stakeholders and society at large should have their well-being properly considered in contracts and statutes (e.g. employment contracts and environmental laws). If these assumptions hold in reality, the maximisation of long-term shareholder value would be the optimal purpose for corporations, namely because:

directors and key executives would be clearly accountable to the sole goal of maximising shareholders’ wealth within what is legally permissible;

society’s welfare would be maximised when a company increases its profits, assuming that market failures – including asymmetries of information – should have been corrected by the state.

The most famous formulation of the logic summarised in the paragraph above was Milton Friedman’s argument that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud” (Friedman, 1970[28]).

Nevertheless, at least since the Principles were first adopted in 1999, consideration of stakeholders’ interests has been featured as a relevant consideration, notably in relation to the recommendations contained in Chapter 4 of the Principles on the role of stakeholders in corporate governance. Moreover, the shift of general discourse in favour of broader consideration of non-financial goals has been accelerating in recent years. In 2019, the Business Roundtable released a statement where 181 CEOs of large US corporations declared they “shared a fundamental commitment to all [their] stakeholders”, including to the delivery of value to their customers, to investing in their employees, to dealing fairly with their suppliers, to supporting communities in which they work and to generating long-term value to shareholders (Business Roundtable, 2019[29]). In his 2020 annual letter, the CEO of BlackRock – the biggest asset management firm worldwide with over USD 9 trillion of assets under management – wrote to CEOs of its investee companies on corporate risks related to climate change and concluded that “companies must be deliberate and committed to embracing purpose and serving all stakeholders – your shareholders, customers, employees and the communities where you operate” (Fink, 2020[30]).

Clearly, a company’s commitment to all its stakeholders is not irreconcilable with its long-term profitability. After all, loyal customers, productive employees and supportive communities are essential for a company’s long-term capacity to create wealth for its shareholders. In any case, it should be noted that corporate law does not typically adhere fully to the “shareholder primacy” view, allowing companies to alternatively serve some stakeholders’ interests potentially at the expense of short or long-term profitability.

In Australia, Section 181 of the Corporations Act provides that directors must exercise their powers “in good faith in the best interest of the corporation” without equating the best interests of the company with those of its shareholders. In Sweden, while Chapter 3 of the Companies Act provides that a company’s “purpose is to generate a profit to be distributed among its shareholders”, the Act also allows companies to establish other purposes in their articles of association” (Skog, 2015, p. 565[31]). In France, legislation amended in 2019 goes further, establishing that “the corporation must be managed in the interest of the corporation itself, while considering the social and environmental stakes of its activity” (art. 1 833, Civil Code). In the United Kingdom, Section 172 of the Companies Act provides that “a director of a company must […] promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, and in doing so have regard (amongst other matters) to […] the long-term, the interests of the company’s employees, […] suppliers, customers, […], the impact of the company’s operations on the community and the environment […]”.

In Canada, the Supreme Court decided in 2008 that when considering what is in the best interests of a corporation, “directors may look to the interest of, inter alia, shareholders, employees, creditors, consumers, governments and the environment to inform their decisions” (BCE Inc. v. 1976 Debentureholders). In 2018, Section 122 of Canada’s Business Corporations Act was amended to codify mentioned jurisprudence with the following language: “when acting with a view to the best interests of the corporation […], the directors and officers of the corporation may consider, but are not limited to, the following factors: (a) the interests of shareholders, employees, retirees and pensioners, creditors, consumers, and governments; (b) the environment; and (c) the long-term interests of the corporation”.

In the US state of Delaware, jurisprudence ranges from an identified director’s duty to maximise shareholder profits (especially in some takeover cases, such as Revlon v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc.) to rulings that suggest that insufficient attention to stakeholders interests may be legally actionable (e.g. Marchand v. Barnhill). Likewise, in the Hobby Lobby case, the US Supreme Court explained that “while it is certainly true that a central objective of for-profit corporations is to make money, modern corporate law does not require for-profit corporations to pursue profit at the expense of everything else, and many do not do so” (Fisch and Davidoff Solomon, 2021[32]).

In any case, from a pragmatic perspective, even if an executive had a strictly defined “shareholder primacy” mandate, the business judgement rule principle20 adopted in many legal systems and statutes authorising companies to donate money would afford the corporate executive significant discretion to consider different stakeholders’ interests (Fisch and Davidoff Solomon, 2021[32]). Except for cases of conflicts of interest, it has been unlikely in practice that an executive would be held liable in court if he or she prioritised within reasonable limits a stakeholder interest at the expense of a company’s current profits. The judge would typically defer to the executive’s assessment of what would be likely best for the long-term profitability of the corporation.

1.7. Shareholders’ and stakeholders’ powers

With respect to a corporation’s objective and its responsiveness to climate change, shareholders and stakeholders commonly have three fora where they may influence or compel managers to incorporate climate change risks into their business decision-making processes: in direct dialogue with directors and key executives, in a shareholders’ meeting, and in courts.

Direct dialogue between stakeholders and management can take many forms. For instance, employees may express their views to management through elected representatives and consumers might boycott a company’s products if harmful environmental practices are exposed. These initiatives could either occur spontaneously (e.g. uncoordinated interactions in social media) or supported by workers unions and civil society groups. In the case of shareholders, the initial engagement would typically take place in private meetings and correspondence, but it could escalate to public letters, proxy contests, complaints to a securities regulator and lawsuits. An individual shareholder may engage independently with a company’s management (e.g. Norges Bank Investment Management follows a structured engagement process with a particular focus on climate change, water management and children’s rights21) or a shareholder may choose to co‑ordinate efforts with others (e.g. Climate Action 100+ mentioned in endnote 4 has regionally focused working groups).

Despite these differences in their engagement methods, climate change is currently a great concern both to stakeholders and investors. A 2021 survey found that 80% of people in 17 advanced economies in the Asia-Pacific, Europe and North America are willing to make at least some changes in how they live and work to help reduce the effects of climate change (Pew Research Center, 2021, p. 3[33]). As seen in Figure 1.3, climate change was the most relevant issue to prompt asset managers to seek engagement with companies in 2020. Better climate‑related corporate disclosure could, therefore, be of interest to a great number of stakeholders in their engagement with companies.

In shareholders’ meetings, shareholders may typically propose a resolution requiring a change in corporate policy, change the composition of the board or even alter a company’s articles of association.

By mid-February 2021, shareholders had filed 66 resolutions specifically concerned with climate change for the year’s US proxy season (in addition to 13 proposals about climate‑related lobbying). Twenty-five of those climate‑related proposals asked for the adoption of GHG emissions reduction targets in line with the Paris Agreement or, in a more indirect way, requested management to inform “if and how” the company plans to reduce emissions in line with the Agreement. In four proposals, investors asked for the establishment of annual advisory votes by shareholders on whether they approve or disapprove a company’s publicly available policies and strategies with respect to climate change – in one of those proposals, this “say on climate change” would be required by the company’s articles of association (As You Sow, 2021[34]).

While some of the abovementioned proposals were withdrawn (in some cases, because management took action before the annual shareholders meeting), others went to a vote and were eventually approved by a majority. For instance, 98% of votes were in favour of General Electric reporting on “if and how” it plans to achieve net zero Scope 3 GHG emissions in its supply chain by 2050, 58% in favour of Conoco Phillips adopting GHG emission goals (Scopes 1, 2 and 322) and 61% in favour of Chevron substantially reducing Scope 3 GHG emissions (As You Sow, 2021[35]). At Phillips 66, a proposal requesting the company to issue a report on whether its lobbying activities are consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement was also approved by a majority of votes (Ceres, 2021[36]). In a proxy campaign followed worldwide in June 2021, a small activist investor was able to find the necessary support from major institutional investors for the nomination of three directors to Exxon Mobil’s board with the main goal of moving the company’s strategy towards a lower carbon footprint (NY Times, 2021[37]).

Shareholders’ proposals are often focused on specific issues and they demand relatively short-term action from management such as developing a report or a strategy, however shareholders may also propose amendments to a company’s articles of association with broader and longer-term consequences. Applicable company law will evidently affect shareholders’ alternatives and needs, but, for instance, articles of association may require a long-term view from management or even explicitly allow executives’ consideration of non-shareholder interests irrespective of their effect on shareholders’ wealth. For example, Switzerland-based Nestlé’s articles of association provide the company “shall, in pursuing its business purpose, aim for long-term, sustainable value creation” (article two, item 3).

Meaningfully diverting a company from a profit-making goal would, however, create a number of challenges, some of which are further covered in this report. That is why some jurisdictions have amended their legislation with the aim to offer a legal structure fit for for-profit corporations willing to adopt objectives other than simply maximising long-term profits, while allowing shareholders to retain the same degree of control of corporate decision-making, such as electing directors and amending the articles of association. This is the case of public benefit corporations (PBC) in Delaware and sociétés à mission in France.

In Delaware, for-profit corporations may, since 2013, be incorporated as or be converted into PBCs, which represents a legal obligation to “be managed in a manner that balances the stockholders’ pecuniary interests, the best interests of those materially affected by the corporation’s conduct, and the public benefit or public benefits identified in its [articles of association]” (Delaware General Corporation Law, Chapter 1, subchapter XV). In addition to identifying one or more public benefits to be promoted by the corporation in its articles of association, PBCs also have the two following obligations: (i) in any stock certificate and in every notice of a shareholders meeting, they must clearly note they are a PBC; (ii) the board of directors should at least every two years report to shareholders on the promotion of the public benefits identified in the articles of association (these articles may also demand a third-party verification of the public interests’ fulfilment). Any action to enforce directors’ and key executives’ obligation to balance pecuniary, stakeholders’ and public interests may only be brought by plaintiffs owning 2% of the PBC’s outstanding shares (limited to USD 2 million in shares if the corporation is listed).

In 2020, Delaware statutory rules were amended in order to facilitate the conversion of conventional corporations into PBCs (Littenberg et al., 2020[38]). Nowadays, an existing conventional corporation needs the approval of only a majority of votes in a shareholders meeting (unless the articles of association provide otherwise) to convert, merge or consolidate with or into a PBC (the same threshold applies for a PBC becoming a conventional corporation). Originally, the threshold established by Delaware law was of 90% of the outstanding shares. Likewise, shareholders who opposed or did not vote for the conversion of a conventional corporation to a PBC no longer have a specific statutory appraisal right (i.e. the right to sell their shares back to the corporation at a fair price).

As of September 2021, 207 private PBCs incorporated in Delaware contained the words “public benefit corporation” or “PBC” in their business names.23 While the number of listed PBCs incorporated in Delaware is so far limited to seven24 (with market capitalisation ranging from approximately USD 700 million to USD 50 billion as of September 2021), it may be too soon to assess the impact of the recent changes to Delaware statutory rules to facilitate such conversions. Veeva Systems, a tech company which is the most valuable listed PBC incorporated in Delaware with USD 47.5 billion market value, states in its articles of association that the “specific public benefits to be promoted by the Corporation are to provide products and services that are intended to help make the industries we serve more productive, and to create high-quality employment opportunities in the communities in which we operate”.

In France, for-profit corporations may, since 2019, adopt social and environmental objectives in their articles of association and, therefore, register with the business name of société à mission (art. L.210, Commercial Code). There are three main conditions for a corporation to be registered with this name: (i) inclusion of social and environmental objectives into the articles of association; (ii) establishment of a committee – with the participation of at least one employee – responsible exclusively for verifying and reporting to the annual shareholders meeting whether the company fulfils its non-financial goals; (iii) verification by an accredited independent third-party of whether the company fulfilled its non-financial goals and report to the annual shareholders meeting. If a corporation does not comply with any of those requirements or the independent third-party concludes a non-financial goal was not fulfilled, public prosecutors or any interested party – which could arguably include stakeholders – may request the suppression of société à mission from the corporation’s business name.

As of the second quarter of 2021, there were 206 sociétés à mission of which just three are listed companies. A majority of sociétés à mission is private and employ less than 50 employees25 (L’Observatoire des Sociétés à Mission, 2021[39]). Among one of the early adopters of the société à mission designation, Danone amended its articles of association in June 2020 and included, among its social and environmental goals, to contribute “to the fight against climate change” and to develop “everyday products accessible to as many people as possible” (art. one, item III).

In some cases, stakeholders may decide a lawsuit is the best or only solution to a disagreement with a company’s management. It may be either because a company’s management was irresponsive to a legitimate request or due to the fact compensation for an irreversible damage is warranted. As a general rule, only shareholders have standing to sue with respect to the violation of directors’ fiduciary duties, but stakeholders may have a number of other grounds to bring a suit against a corporation or its managers (some examples below).

Corporations were defendants in 18 climate change‑related court cases filed globally between May 2020 and May 2021 (14 in the United States and 4 in other countries).26 Climate‑related corporate litigation has been traditionally focused on major carbon-emitters (there are 33 ongoing cases worldwide against the largest fossil fuel companies), and applicants have most commonly argued defendants were liable for past contributions to climate change (for instance, municipalities in the United States requesting damages to pay for climate change adaptation). An increasing number of claims, however, have also covered the current fulfilment of fiduciary duties and due diligence obligations by companies and their managers in industries other than oil and gas, and cement (notably pension funds, banks and asset managers as defendants), including claims of insufficient disclosure of climate‑related information, inconsistencies between discourse and action on climate change, and inadequate management of climate risks (Setzer J and Higham C, 2021[40]).

As an example of recent litigation strategies focused on the fulfilment of fiduciary and care duties, a member of an Australian pension fund claimed the fund was not disclosing and managing climate change risks as it would have been required according to broadly defined duties of care and transparency under company and superannuation industry laws. In a settlement in 2020, the fund agreed to report on climate in line with TCFD recommendations and to adopt a net zero 2050 goal (McVeigh v. REST). In another example, in 2021, the District Court of the Hague, answering to a suit brought by seven environmental NGOs and more than 17 000 citizens, ordered an oil and gas company based in the Netherlands to reduce its own emissions and its customers’ emissions in accordance with the goals of the Paris Agreement as an obligation derived from the standard of care laid down in the Dutch Civil Code (Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell) (LSE, 2020[41]). In establishing the duty of care for the concrete case, the court explicitly referenced the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, quoting the opening recommendation in the Environment chapter on taking “due account of the need to protect the environment” (OECD, 2011[42]).

Notes

← 1. It is acknowledged that ESG and sustainable investing encompass a wider range of issues than climate change and its associated risks. However, this report starts with these broader categories to provide an indication of the trends and magnitude of investor focus on ESG-related criteria, including climate change. With due consideration of the challenges involved in separating out data on climate‑related investing alone, complementary sources of data that are more specific to climate change are also considered in the report.

← 2. Funds retrieved from the Reuters Funds Screen were classified as Climate Funds or ESG Funds in cases where their names contain, respectively, climate or ESG relevant acronyms and words such as ESG, sustainable, responsible, ethical, green and climate (and their translation in other languages).

← 3. According to another estimate, the impact investing market size worldwide (including emerging markets) was equal to USD 715 billion at the end of 2019 (GIIN, 2020[98]).

← 4. With respect to environmental factors related to climate change, this value of assets under management might even be an underestimation, because some investors who do not have a clear sustainable investing mandate might nonetheless be concerned with their exposure to climate risks (and willing to engage with corporates to reduce their risks). For instance, 615 investors (including from emerging markets) with USD 60 trillion in assets under management have so far joined the Climate Action 100+, which is an initiative to ensure the world’s largest corporate GHG emitters (currently, 167 focus companies representing more than 80% of global industrial emissions) cut emissions to help achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement (Climate Action 100+, 2021[105]).

← 5. Companies sometimes make reference to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (the 2030 development agenda adopted by all UN members in 2015) and to the UN Global Compact (an engagement initiative with companies on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption) in their sustainability and mainstream filings. While relevant, they would not normally be considered as ESG accounting and reporting frameworks or standards per se.

← 6. The eight industries are: banking; insurance; energy; materials and buildings; transportation; agriculture, food, and forest products; technology and media; and consumer goods. Companies were selected based on 2019 company size thresholds: banks and insurance companies with more than, respectively, USD 10 billion and USD 1 billion in assets; all other companies with more than USD 1 billion in revenues. Companies were removed from the sample if they did not have annual reports in English for all the three years under analysis.

← 7. The difference between regions may be explained by different factors, but one to consider is the distribution by industries in each country. For instance, companies in the technology and media industry globally tend to report less often in line with TCFD recommendations (probably because the industry is seen as relatively less exposed to climate‑related risks), and the sample of North American companies was skewed toward the technology and media industry (TCFD, 2021, p. 36[15]).

← 8. IAASB defines “assurance engagement” as “an engagement in which a practitioner expresses a conclusion designed to enhance the degree of confidence of the intended users other than the responsible party about the outcome of the evaluation or measurement of a subject matter against criteria” (2000, pp. 6, 13[104]). It includes both the audit of financial statements and engagements on a wide range of subject matters such as climate‑related disclosure.

← 9. The 100 largest companies by market capitalisation in The People’s Republic of China, Germany, India, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, and the 50 largest in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, France, Italy, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, Australia, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Singapore and Korea.

← 10. © 2021 Value Reporting Foundation. All Rights Reserved. OECD licenses the SASB SICS Taxonomy.

← 11. SASB mapping serves as the organising structure for the SASB Standards. Each one of the 77 industries in the mapping has its own unique Standard, and the accounting metrics in each Standard are directly linked to the sustainability themes that were considered to be financially material to an industry in the mapping (SASB, 2017, pp. 16-17[107]). The changes in the SASB mapping and the SASB Standards are, therefore, intertwined in a structured standard-setting process. This process is based on evidence of both financial impact and investor interest, using both research by Value Reporting Foundation staff and consultation with companies and investors (SASB, 2017, pp. 13-16[106]). Any change in SASB Standards and its accompanying mapping goes through extensive due process, including being approved by a majority vote of the SASB Standards Board, which is composed of five to nine members with diverse backgrounds (e.g. experience and expertise in investing, corporate reporting, standard-setting and sustainability issues) (SASB, 2017, pp. 9-10[106]).

← 12. SASB mapping does not include a risk category for GHG Scope 3 emissions.

← 13. Classification in the table is made from a universe of listed companies consisting of 38 834 companies with a total market capitalisation accounting for almost 99% of all publicly listed companies worldwide. The universe covers all non-financial and financial companies and excludes all types of funds and investment vehicles including Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). The primary listing venue is taken into account when identifying the market where the company is listed. Secondary listings are not taken into account. The list of listed companies for each market contains only firms that trade ordinary shares and depositary receipts as their main security. Companies trading over-the‑counter and on non-regulated segments are excluded.

← 14. In the Annex of this document, a more comprehensive version of Table 1.5, including all sustainability issues from the SASB mapping, is presented.

← 15. In addition to the paper detailed in this paragraph, a meta‑analysis of 198 studies suggests that good sustainability practices likely increase a firm’s financial performance, especially in the long run (Lu and Taylor, 2016[99]). A study of 25 meta‑analyses found a highly significant, positive, robust and bilateral relation between sustainability and financial performances (Busch and Friede, 2018[100]).

← 16. A review of 59 papers focused on the relationship between climate‑related corporate results and corporate financial performance found a similar relationship as identified for ESG results more broadly: 57% arrived at a positive relationship, 9% mixed conclusions, 29% a neutral impact and 6% a negative impact (Wheelan et al., 2021, p. 2[20]).

← 17. The total market capitalisation of these 7 801 listed companies as of end 2021 account for almost 82% of all publicly listed companies worldwide.

← 18. The total market capitalisation of these companies account for almost 83% of all publicly listed companies.

← 19. The index of 100 large UK-listed companies.

← 20. The business judgement rule acts as a presumption that the board of directors fulfilled its duty of care unless plaintiffs can prove gross negligence or bad faith. Similarly, if a director had a conflict of interest, the court will not typically uphold the presumption.

← 22. For a definition of Scopes 1, 2 and 3 emissions according to the GHG Protocol, please see notes to Table 1.3.

← 23. Thomson Reuters Eikon, OECD calculations.

← 24. These seven listed PBCs are Zevia PBC, Mpower Financing Public Benefit Corp., Veeva Systems, Lemonade Inc, Vital Farms, Laureate Education Inc., and Appharvest Inc.

← 25. The three listed sociétés à mission are Danone, Voltalia, and Realites. They had, respectively, market capitalisations of USD 45 billion, USD 2.3 billion and USD 106 million as of September 2021.

← 26. 40 countries are included in the database (among others, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, most European countries, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Pakistan, South Africa and the US) and 13 regional or international jurisdictions. However, due to limitations in data collection (for instance, cases filed in US state courts are not covered), numbers may not include every climate case filed in all aforementioned jurisdictions.