Paula Garda

OECD

Jens Arnold

OECD

Paula Garda

OECD

Jens Arnold

OECD

Chile has developed one of the most comprehensive social protection systems in Latin America. However, after the social unrest in late 2019, the pandemic has highlighted significant gaps in social protection, in particularly among informal workers. A key lesson emerging from the pandemic is the need for developing a better social protection system that does not differentiate between formal and informal workers. Ensuring some basic social protection coverage for all, including in pensions, health and unemployment insurance, while simultaneously reducing the cost of formal employment, would reduce labour informality. Unifying social assistance programmes into a single cash benefit scheme while increasing coverage and benefits and providing incentives to take up formal employment will be key to tackle poverty and raise job quality. These reforms would raise productivity and decrease inequality, two priorities and long-standing challenges.

Chile has made remarkable progress in improving social outcomes such as poverty over the last three decades. Strong economic growth was one of the main factors explaining the social progress, in conjunction with the construction of a comprehensive social protection system. However, long-standing inequalities of opportunities and outcomes, economic insecurity, an unequal access to quality public services led to widespread social unrest at the end of 2019. Citizens' demands for better-quality social services such as health, pensions, and education, among others, were among the most frequently-voiced social demands. Inequalities of opportunities, including unequal access to high-quality public services, are not only an obstacle to social cohesion but also hold back productivity growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the strengths and weaknesses of current social protection policies. Chile has one of the most comprehensive social protection systems in Latin America, including a universal basic pension recently made available to all Chileans and universal access healthcare. Chile has also unemployment insurance and employment subsidies for formal-sector workers, and furlough and job retention schemes that were introduced during the pandemic. But informal workers, defined as those with no contributions to social security, account for almost 30% of the labour force, and have no similar protection to fall upon. Instead, they had to rely on emergency cash transfers put in place during the pandemic, whose roll-out suffered from significant implementation delays during the first months of the pandemic, given the previously patchy coverage of cash transfers. This led to high pressures on the authorities to approve extra-ordinary pension fund withdrawals and develop an almost universal cash transfer scheme in 2021. As a result, overall support overcompensated the loss of incomes during the pandemic and fuelled a temporary consumption boom and inflationary pressures. Although Chile did not have especially high mortality rates,, the pandemic was particularly deadly and infectious among vulnerable Chileans (Mena et al., 2021[1]; Villalobos Dintrans et al., 2021[2]; Gozzi et al., 2021[3]), suggesting that inequalities in living and health conditions and access to good-quality health services put these vulnerable groups at a significant disadvantage.

One key lesson that emerges from the pandemic is the need for developing a more effective social protection system, providing basic social benefits that do not differentiate between formal and informal workers. Effective social protection is key to protect workers against idiosyncratic shocks, such as job loss, and old-age poverty, but also to allow them to adapt to disruptions and changes. The pandemic has been the most visible example, but the digital transformation, climate change, population ageing, migration, and possible natural disasters are also likely to trigger adjustment processes whose social implications will need to be cushioned.

Improving social protection will also trigger substantial benefits for productivity and long-term growth (UNDP, 2021[4]). Effective social protection lays the grounds for enabling workers and their families to access better-quality jobs. At the same time, it helps low-income earners invest more in their health, their human capital and that of their children.

So far, the strategy to address the lack of coverage in social protection of informal workers and vulnerable people has been to develop non-contributory pillars in pensions and healthcare, in combination with cash transfers schemes that have helped to reduce poverty. However, these cash transfer programmes do not reach all of those in need and benefits are low. The healthcare system has achieved full coverage, but its financing encourages informality while access to high-quality services remains highly unequal. A recently established universal guaranteed minimum pension has helped to raise replacement rates, a long-standing challenge for Chile, although they continue to be low for women and middle-income workers, calling for further reforms.

The current dual architecture of social benefits generates disincentives for formal job creation, especially for low-income workers. Current formal-sector benefits are financed through social security contributions levied on formal labour. Although the causes for informality are multidimensional, including low quality education and other worker and household characteristics, deficient public transportation, and complex regulatory burden, social security contributions drive a wedge between the cost of formal and informal hiring, and price many low-productivity workers out of formal employment, leaving many workers insufficiently protected and in low-quality jobs. In some cases, imperfect enforcement of existing regulations can allow firms to avoid the costs of social insurance and hire salaried workers informally. Other times, low-income or self-employed workers may face high costs of formalisation and prefer to remain informal, which is reflected in the low social insurance coverage.

The long-term goal of achieving universal formalisation and universal social protection coverage will require reforms to social security and social assistance schemes, coupled with adjustments to labour market policies. One solution would be to provide a basic level of pension, healthcare and unemployment benefits to all Chileans that is not tied to formal employment financing these from general taxation revenues, while reducing social contributions for low-income workers. This basic protection could then be complemented by a more comprehensive set of contributory benefits financed by progressive contributions.

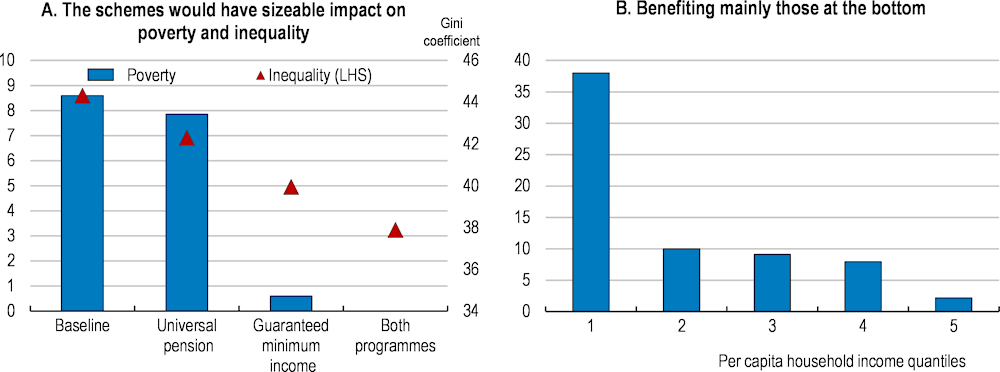

Poverty could be reduced more effectively by unifying current cash transfer programmes into a single conditional cash benefit scheme with increased coverage and benefit levels, designed carefully to maintain strong work incentives. To achieve this, benefits should remain significantly below potential labour incomes, but they should also be withdrawn only gradually upon taking up formal employment, as otherwise beneficiaries might be reluctant to take up formal work for fear of losing their benefit. Tying benefits to individual behaviour that promotes future employment outcomes such as school completion, training and participation in public employment services would also help families to graduate from social assistance.

The main benefit of such a reform package would be to initiate a virtuous cycle between reductions in poverty and inequality and better growth prospects. Workers in the bottom 60% of the income distribution would clearly benefit from the better formal job opportunities and take-home pay that such reforms could deliver. For many current formal workers, the effective tax burden would be reduced or not change much, as the reduced social contributions would only be partly substituted by increases in personal income taxes and possibly value-added taxes. For formal workers with relatively higher incomes, a more progressive income tax schedule would likely imply a higher tax burden than at present. In this sense, social protection reforms could go together with a tax reform to broaden the personal income tax base, and make the personal income taxes more progressive, as argued in Chapter 1, two long-standing challenges for Chile. Continuous efforts to improve the education and training system and to enhance labour and tax enforcement should complement improvements in formalisation incentives, among others.

Financing these reforms will require raising permanent additional resources of about 2.2% of GDP, which could be financed with the tax reform currently under discussion. This estimate is an upper bound, as the increased formalisation and growth, and resulting revenue collection that such a reform would deliver are not taken into account. This additional spending would bring benefits for social inclusion and growth, and given its low tax revenues by international standards, Chile has space to do this (see Chapter 1).

In many respects, the costs will be more of a political than an economic nature. The difficulties of finding the necessary political consensus for the reforms discussed in this chapter should not be underestimated. The political economy of the broad overhaul of existing institutions that Chile needs, together with the required fiscal reforms to secure additional revenues, is likely to be winded. However, Chile has demonstrated its capacity to implement deep reforms on many occasions, including the 2008 reform to the pension system or the 2016 educational reform. The experiences of the social unrest in late 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic make social protection reforms a matter of urgency to strengthen social cohesion. The broad reform agenda implemented or discussed since the beginning of the current legislature in March 2022 testify to this urgency.

This chapter analyses the strengths and challenges of the current social protection system and reviews policy options to achieve universal coverage of basic social protection while boosting formal employment. The benefits of reforming social protection would be amplified by simultaneous policy action in other policy areas, including reforms to boost the structurally low and stagnant productivity of firms and the low access to high quality education and training, as discussed in Chapter 1 and in previous Economic Surveys (OECD, 2018[5]; OECD, 2021[6]).

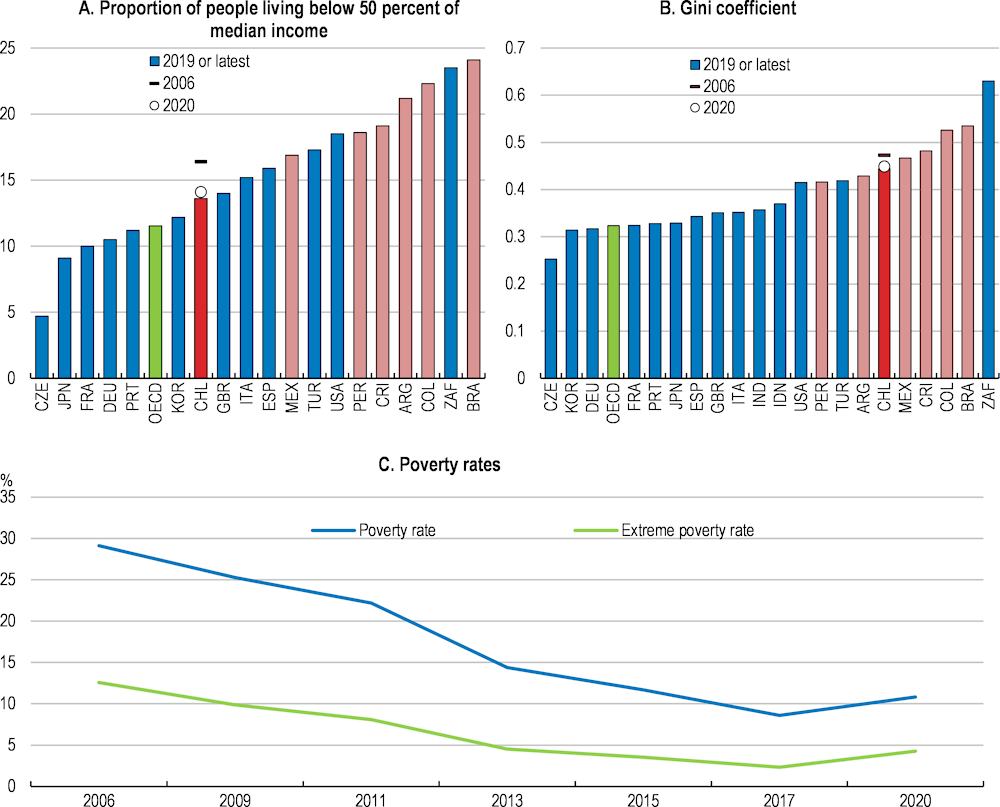

Chile has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty over the last 30 years. Before the pandemic the poverty rate was one of the lowest in Latin America (Figure 2.1). Inequality has also declined, although much more modestly. Moreover, the decline in inequality over the last two decades is called into question when adopting more sophisticated ways to account for capital income and undistributed corporate profits, which are typically underreported in household surveys (Flores et al., 2019[7]; Larrañaga, Echecopar and Grau, 2021[8]). Economic vulnerability, defined as the share of the population at risk of falling into poverty, has also decreased considerably, at the same time as Chile's middle class expanded rapidly (World Bank, 2021[9]). Despite this progress, poverty and inequality remain high by OECD standards.

Economic growth was the main driver of the fast reductions in poverty and vulnerability (Ricci and Hadzi-Vaskov, 2021[10]). The end of the commodity boom in 2014 and the concomitant growth slowdown explain why progress on equity stalled. While social policy and the tax system contributed to the decline in poverty, they had little impact on inequality (Repetto, 2016[11]).The redistributive impact of direct transfers is high in relation to other countries in Latin America, but low compared to more advanced countries (Lustig, 2016[12]). In-kind transfers, particularly education and healthcare services, have also contributed substantially to the reduction of inequality and poverty in the last decades (Martinez-Aguilar, Fuchs and Ortiz-Juarez, 2017[13]).

The Covid-19 pandemic had a profound impact on lives and livelihoods, like in many other countries, increasing poverty from 8.6% in 2017 to 10.8% in 2020. Many of these newly poor households suffered steep income declines and 540,000 people fell into poverty. Inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increased by 4 points during 2020. Massive losses of jobs and livelihoods, particularly among the vulnerable, were the main drivers of this increase in poverty and inequality in 2020 (Figure 2.2), despite a significant expansion of existing benefit programmes and the development of a new pandemic-related programme targeting informal workers that effectively mitigated the economic fallout of Covid-19.

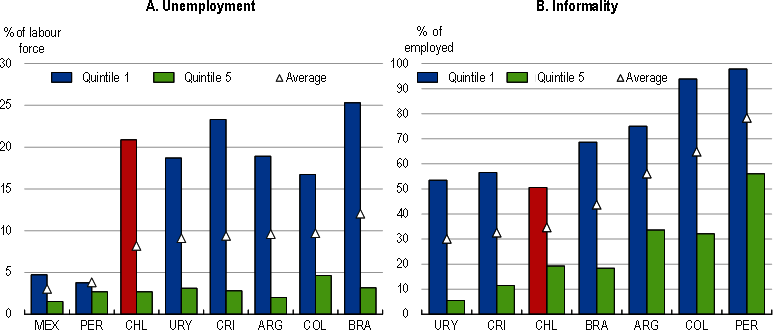

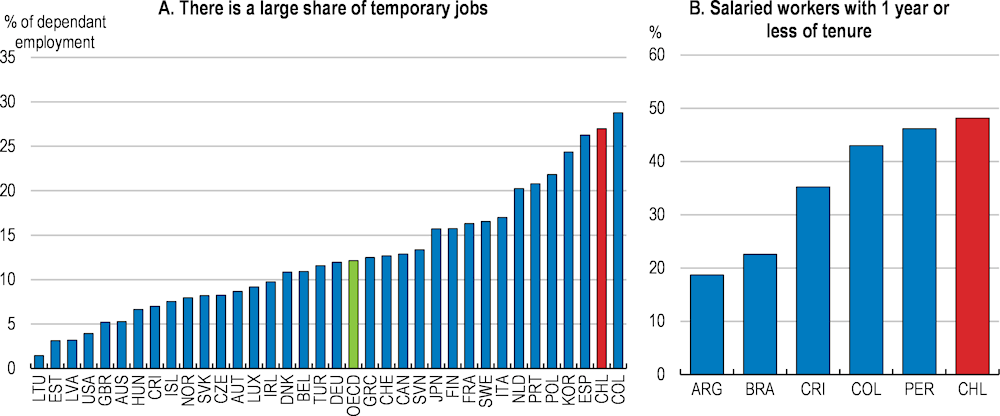

The strong socio-economic impact of the pandemic go back to pre-existing structural gaps and inequalities in the labour market, driven by a high share of informal jobs and unemployment that affect particularly the lowest part of the income distribution (Figure 2.5). One in every three workers in Chile has an informal job. Informality leaves workers, mainly in the lowest part of the income distribution, excluded from formal (contributory) social security – and hence inadequately protected by the social protection system (Box 2.1), with no access to training and unemployment insurance. Additionally, lower access of the least advantaged groups to digital technologies and education, longer commuting distances in public transportation, inability to quarantine due to lack of savings explain why these groups were disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

Note: In Panel A, poverty is defined as the share of people living in a household below the 50% of the median disposable household per capita income (or, in some cases, consumption expenditure). This poverty measure is different from the national definition of poverty by the Ministry of Social Development, which is used in Panel C. Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income after taxes and transfers (or, in some cases, consumption expenditure) among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. Panel C shows poverty using the national definition based on the calculation of the basic food consumption basket.

Source: World Bank, WDI; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia de Chile.

Before the pandemic, the labour market was showing signs of deterioration, implying that workers faced the recession caused by the pandemic from a rather weak starting position. The unemployment rate increased from 6.1% in 2013 to 7.2% in 2019. Job quality also deteriorated during this period, with self-employment, which is mostly informal, growing more strongly (on average, at 3.8% per year), while salaried employment grew by less than half in the same period (1.6%). A high share of temporary jobs and high job turnover is another structural factor explaining the large impact of COVID-19 on the labour market (Figure 2.6), as often these workers do not fulfil the requirements to access the unemployment insurance system in case of dismissal. Additionally, many jobs created in the last five years prior to the pandemic were concentrated in low-productivity sectors with high rates of informality, such as construction, hotels and restaurants and retail. These sectors were precisely the most affected by the pandemic (Villanueva and Espinoza, 2021[14]). The social protests in 2019 did not have a significant impact on total employment, but they accelerated informal job creation with more than 100 000 workers falling into informality, leaving more workers without social protection when the pandemic unfolded.

Informal workers suffered the most from the economic fallout of the pandemic, as job losses among informal workers were twice as high as among formal workers. This marks a break with past recessions when informality used to cushion the decline in employment and acted as a countercyclical buffer (OECD, 2010[15]). During the pandemic, the lockdowns and mobility restrictions forced many informal workers to stay at home and leave the labour force. While informal workers saw a 3% decline in their median labour income in 2020, median labour income decreased by only 1% for formal workers (Figure 2.7). Given the nature of informality, stimulus policies in the form of credits, wage subsidies or furlough schemes generally failed to reach informal workers. Moreover, as informal workers have usually no access to savings or any type of social protection, they depended on government cash transfers. During 2020, these compensated only partially for their lost income (Busso et al., 2020[16]).

There is no unique international definition for informal employment. However, a generally accepted way to define it is jobs that are not taxed, registered by the government or that do not comply with labour regulations. This chapter defines informal employment as all types of workers not contributing to social security, i.e. the pension system or the health system. Although there is not a perfect correlation, when a worker or his/her employer pay pension contributions then they typically pay for health contributions and comply with employment regulations. Labour informality is not always illegal, as sometimes some types of workers are not obliged to contribute to the pension or health systems. This is the case for many self-employed workers. In Chile, contributions by self-employed workers that issue invoices became mandatory only in 2019. Businesses can also be informal by not being registered with the tax administration and without formal accounting, which is usually correlated with not paying social security contributions for their workers.

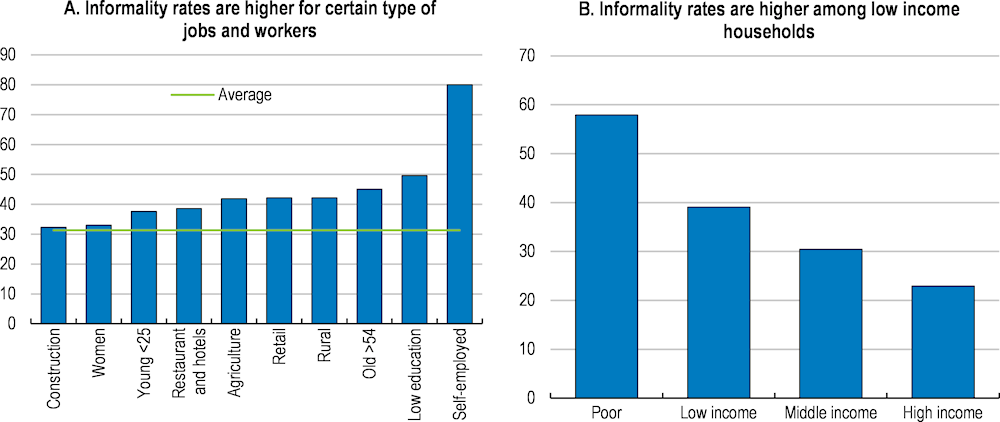

Chile has experienced a substantial reduction in its labour informality rate since 2010, with a fall from around 40% to around 30% of the total workforce in 2019. In comparison with other Latin American economies, this share is still comparatively low. Informality is higher among self-employed workers and among lower-income households (Figure 2.3). Informal workers tend to have lower and more unstable incomes. Many workers in Chile transit between formality and informality many times during their professional careers (OECD, 2018[5]). This implies that some workers, even when they contribute for some time, usually do not fulfil the requirements to access unemployment insurance, nor are they able to save much for pensions.

Informal employment is highly correlated with a few socioeconomic characteristics. Most rural workers regularly hold informal jobs, as do young and old workers, and low-skilled workers (Figure 2.4). The share of informal workers is slightly larger among women than among men. However, there exists a low female employment rate (55% in 2021 against 61.4% in the average OECD country). The agricultural sector, retail, hotels and restaurants and the construction sector concentrate many informal workers. Poverty rates are higher among workers in informal employment.

Note: CASEN 2017 is used as 2017 is the last pre-pandemic year available for household surveys. Year 2020 is an atypical year affected by the pandemic.

Source: (Morales and Olate, 2021[17]).

Note: Year 2017. Informality is defined as those not contributing to the pension system. In panel B: poor are those individuals in households with per household income below the poverty line; the low-income class comprises individuals in households with household income between the poverty line and 2.1 poverty lines; the middle-income class comprises individuals in households with household income between 2.1 and 3.3 poverty lines, the upper-income are individuals in households with income of more 5.6 poverty lines.

Source: OECD calculations based on Households Surveys, Casen 2017.

Digital transformation could intensify existing contributory gaps in the pensions and other social protection schemes because of more frequent job changes, more unemployment spells or the inherent nature of the digital jobs, such as digital platforms.

Note: Year 2019. Informal workers are defined as those not paying pension contributions.

Source: IADB Sims Database.

Note:Data refer to 2019 in panels A and B, except for AUS and USA, for which the data refer to 2017.

Source: OECD labour force statistics and IADB Sims Database.

Women and youth were more affected by the pandemic than men and older workers (Figure 2.8). Female labour force participation saw an unprecedented reduction during 2020. Growth in female labour force participation, which was already below the OECD country average, was set back by a decade by the pandemic, and as the economy rebounds, the recovery has been slower than for men. This is, at least partly, explained by school closures, which lasted for around 20 weeks in 2020, one of the longest closures in the region. Youths are more likely to have informal jobs or fixed term contracts and are hence less protected by the social security system. Moreover, with the economic and social effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, young Chileans have been experiencing growing concerns over their future income, mental health, education, employment, and ability to partake in public life. OECD evidence suggests that deteriorating opportunities for young people due to the COVID-19 crisis risk leaving long-lasting scars on their trust in government and satisfaction with democracy (OECD, 2022[20]).

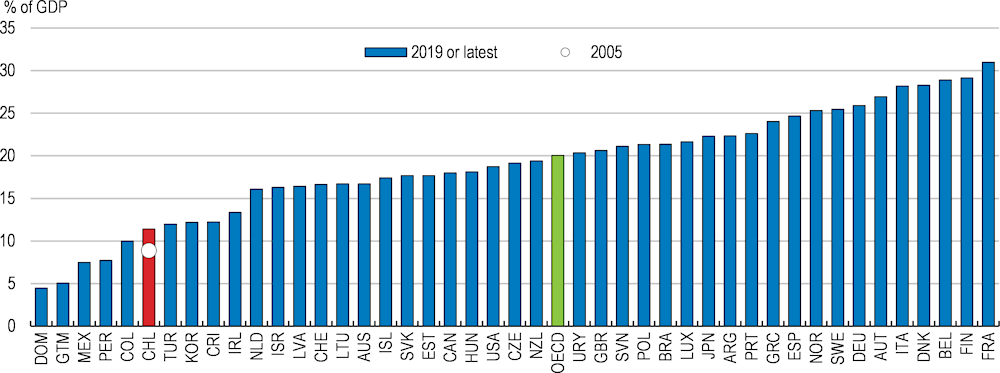

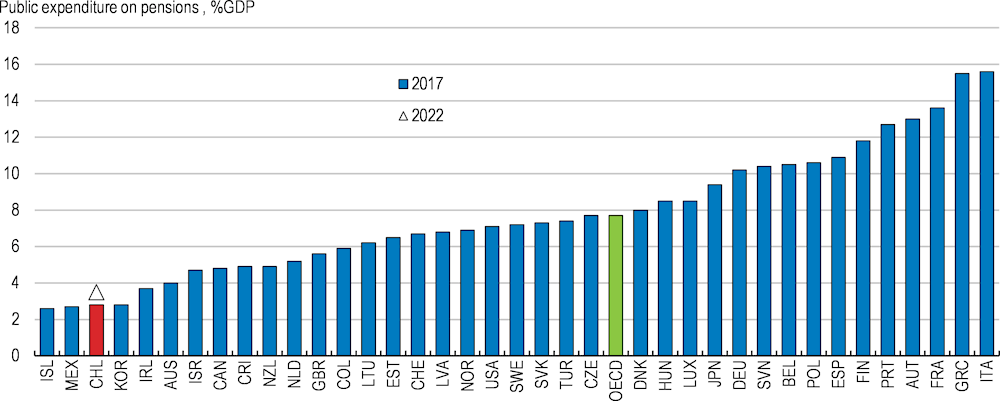

Chile has developed one of the most comprehensive social protection systems in Latin America (Box 2.2). Beginning in the early 2000s, a series of policy reforms expanded access to public services and income support programmes. This brought health, social assistance and, to a lesser degree and only more recently, education, closer towards universal coverage. In 2020 there were 469 social assistance programmes supervised by 12 ministries according to the Ministry of Social Development and the Family (MDSF) and the Budget Office (DIPRES). Although social spending has constantly increased over the last decade, at 11.4% of GDP it remains low compared to the OECD average in 2019 (Figure 2.9). Around 40% of social spending is allocated to the social protection system, according to the Budget Office. 50% of this social protection spending is allocated to pensions and less than 13% to social assistance programmes supporting the poor and the vulnerable.

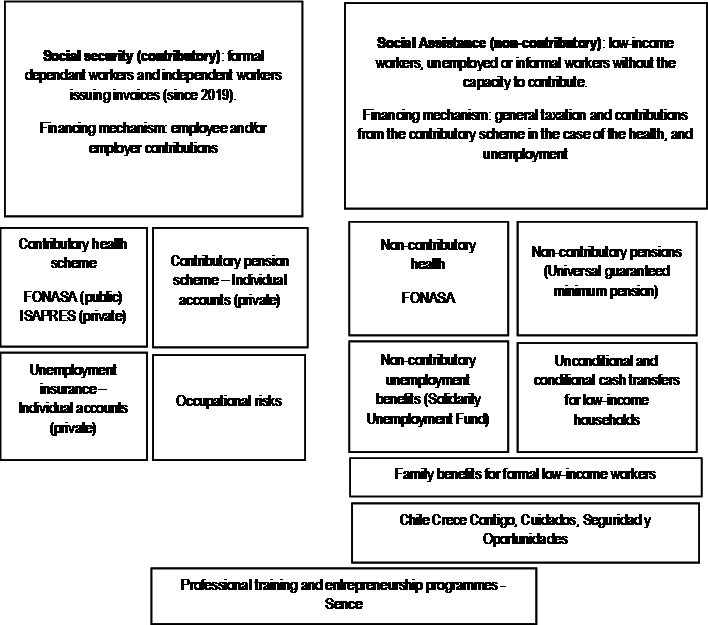

Access to social protection is mostly determined by the labour market status of the worker. The first component are social security benefits associated with formal work. These are financed mostly from employee and employer contributions that are proportional to worker salaries or wages (Table 2.1). Government top-ups complement workers’ or firms’ contributions to increase benefits of these formal workers. The second component of the social protection system is the social assistance system, which was created to provide insurance to those left out of the contributory social security system and is generally financed from general tax revenues. In this component, Chile has managed to achieve universal access to healthcare and pensions.

Note: Year 2019. Social expenditure comprises old-age, survivor, incapacity-related, health, family, unemployment, housing, active labour market support and other social policy areas. It comprises cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes.

Source: OECD Social expenditure database; CEPAL.

|

Dependent worker |

Self-employed |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Paid by the worker |

Paid by the employer |

||

|

Pensions |

10% |

10% |

|

|

Disability and Survivorship insurance |

1.85% |

1.85% |

|

|

Pension fund manager administration fee (market average) |

1.16% |

1.16% |

|

|

Health (private/public) |

7% |

7% |

|

|

Work-related accidents and occupational diseases insurance |

0.95% |

0.95% |

|

|

Unemployment insurance: open-ended [fixed-term] contracts |

0.6% [0%] |

2.4% [3%] |

- |

|

Medical leave for working parents of children with a serious health condition fund |

0.03% |

0.03% |

|

|

Total [fixed-term] |

18.76% [18.16%] |

5.23% [5.83% ] |

20.99% |

Note: For the self-employed workers these numbers do not apply completely as only in 2019 became mandatory the contribution for self-employed workers and will only cover 100% of taxable income in 2027.

Source: OECD calculations.

The Chilean social protection system is characterised by a large participation of private actors, such as private pension and unemployment funds, based on savings in individual accounts. The social assistance system and some other public social policies, such as education, health and housing, are targeted to the most poor households and are generally of lower quality than the more costly private services accessed by middle-income and high-income households (Repetto, 2016[11]).

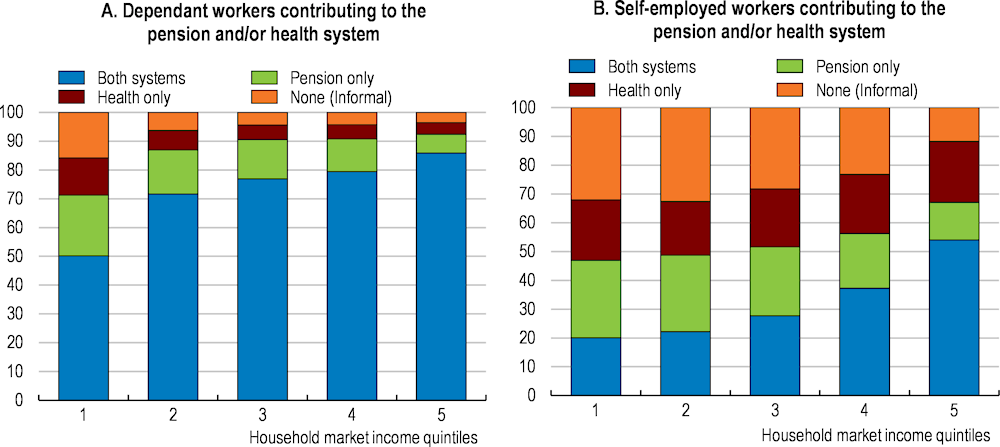

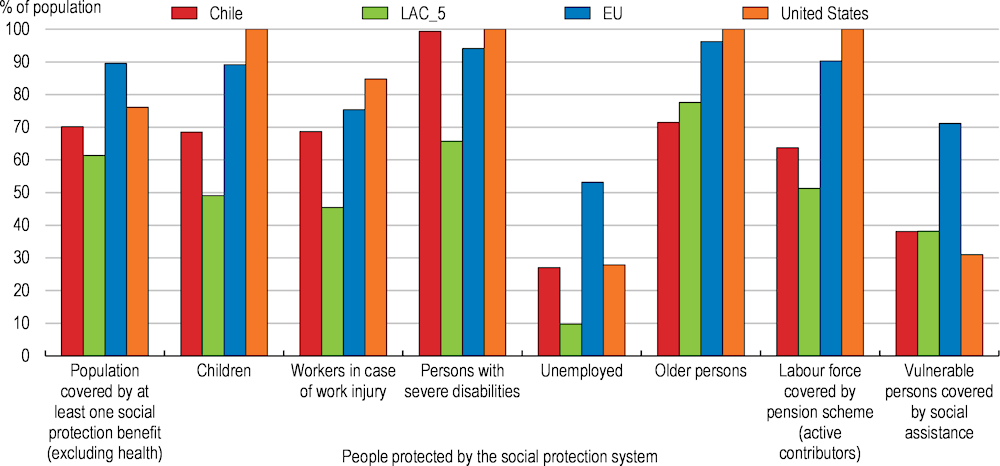

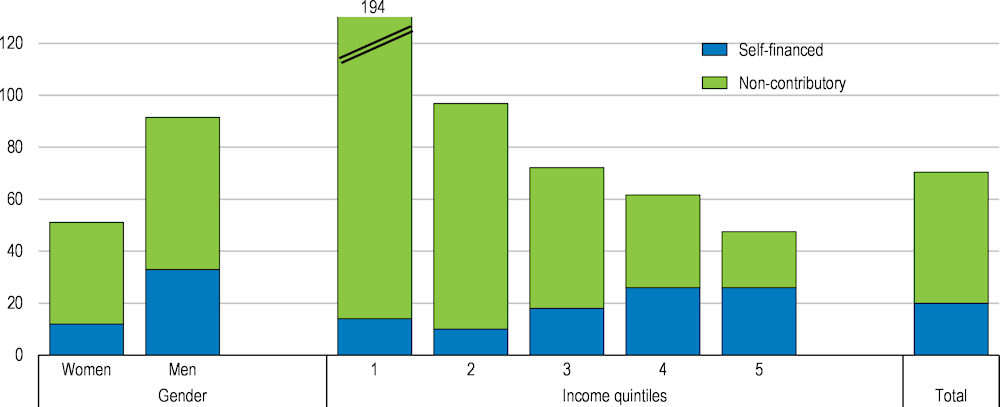

The result of this framework is a segmentation of the labour force into two categories: formal workers, covered by contributory programmes and minimum wage regulations, and informal workers, who are covered by universal access to healthcare and the universal guaranteed minimum pension and some of which have access to cash transfer assistance programmes. Many informal workers, however, have incomes above the poverty line, which generally precludes them from accessing cash transfer benefits or unemployment insurance. Informal workers have also less access to training and more unstable earnings. This duality has led to a low coverage of social protection (Figure 2.10), particularly among certain groups such as the unemployed, although social protection coverage is higher than in other Latin American countries.

The fragmented social protection system not only creates incentives for informality that foster inequality, but contributes to low productivity growth (Levy and Schady, 2013[21]; Levy and Maldonado, 2021[22]). When contributory benefits are not fully valued by workers, they tend to act as an implicit tax on formal employment. At the same time, non-contributory benefits can act as a subsidy to informality when they are perceived as similar to those enjoyed by formal workers, who pay for them. At the same time, firms tend to stay inefficiently small as they attempt to fly below the radar of labour market and tax inspections (Ulyssea, 2020[23]). Additionally, informality hinders worker mobility, productivity-enhancing resource reallocation and workers’ access to quality jobs and training (López-Calva and Lustig, 2010[24]; OECD, 2018[25]; OECD, 2019[26]).

Note: Year 2020 or latest available year. Vulnerable people are defined as all children plus adults not covered by contributory benefits and people above retirement age not receiving contributory benefits (pensions). LAC5 is the unweighted average of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico.

Source: ILO, World Social Protection Database, based on the SSI; ILOSTAT; national source.

The social protection system combines social insurance (contributory schemes) and social assistance system (non-contributory schemes).

The social security system comprises the contributory schemes in health, pension, disability and unemployment insurance, occupational risk coverage and family benefits (Figure 2.11). Workers covered by this system are also subject to regulations on employment protection and minimum wages. The level of mandatory contributions is the same for employees, self-employed or own-account workers, and amounts to around 22% of earnings. Only around 5 percentage points of these contributions are paid by the employer, which is a major difference in relation to most social security systems throughout the world. Self-employed, entrepreneurs and non-remunerated workers are not required to contribute to social security. Only in 2019 were contributions by self-employed workers who issue invoices made mandatory. The collection is done through the tax system as these workers are subject to VAT payments. The government also contributes to this system to ensure more adequate benefits.

The social assistance system or non-contributory schemes, financed through general taxation, includes a health scheme for low-income households; a non-contributory pension scheme and conditional cash transfer programmes (such as Subsidio Único Familiar and Ingreso Ético Familiar). Other welfare programmes include Chile Crece Contigo (Chile grows with you), an early childhood development subsystem; Seguridades y Oportunidades (Securities and Opportunities), a subsystem that coordinates the delivery of a range of social services and benefits provided by different government institutions to improve the wellbeing and social cohesion among Chile’s poorest vulnerable families and other specific priority groups; and Cuidados (Care), an inclusion subsystem providing protection to households with elderly or family members with any disability. The national training institution (Servicio Nacional de Capacitación y Empleo, SENCE) offers vocational and professional training and employment subsidies to vulnerable and poor households.

Source: OECD Secretariat.

Chile has performed better than other countries in Latin America on social programmes, with fighting poverty being the main focus. The number of families receiving income-support has increased in the last two decades to cover different needs during the life-cycle (for example children, the elderly, the disabled, the unemployed, women, youth). Although there are longstanding social programmes supporting low-income formal workers, social assistance programmes mostly aim at protecting those left behind by social security schemes, typically informal workers in poor households.

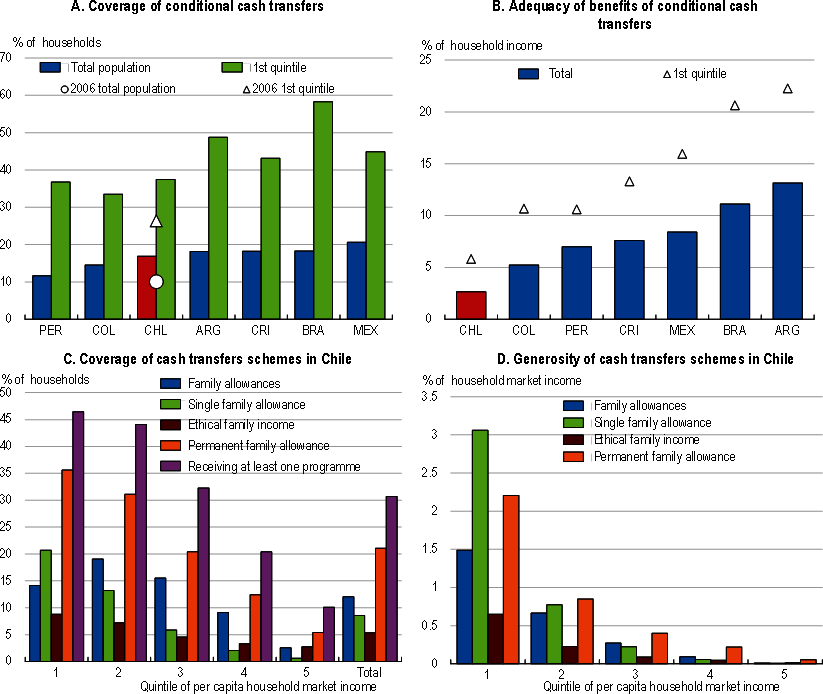

While cash transfer programmes have contributed to reduce poverty (Cecchini, Villatoro and Mancero, 2021[27]; Focus, 2016[28]) and coverage has increased in the last decades, the main cash transfer programmes (Box 2.3) have not reached all those in need and benefits are low even in regional comparison (Figure 2.12). Coverage reached 30.7% in 2017 for the main social assistance programmes, but only 51% of households in poverty were receiving at least one type of income support according to the household survey. Moreover, some households in the upper part of the income distribution were receiving cash transfers, to the detriment of public spending efficiency. Benefits levels are generally low (Figure 2.12, Panel B). On average, those in the first quintile of the income distribution received cash transfers for 9% of household market income, limiting the impact on poverty reduction.

Note: Data are for 2019, except 2017 for Chile. Family allowances=Asignaciones familiares, Single family allowance=Subsidio Único Familiar, Ethical Family Income=Ingreso Ético Familiar; Permanent family allowance=Aporte Familiar Permanente.

Source: OECD calculations based on CASEN 2017 and World Bank, Atlas of Social Protection: Indicators of Resilience and Equity (ASPIRE).

More than 95% of social assistance spending to reduce poverty and vulnerability is channelled through cash transfers programmes, while other programmes promote entrepreneurship, training or labour intermediation. Social assistance programmes are mainly family-oriented cash benefits (Table 2.2), which include mean-tested family allowances for formal workers (Asignación Familiar), a mean-tested conditional family cash transfer for low-income informal workers (Subsidio Unico Familiar), and a social assistance programme offering conditional and unconditional cash transfers for families and children in extreme poverty (Ingreso Ético Familiar). Other unconditional cash transfers are offered to all cash transfers recipients (such as Aporte Familiar Permanente).

|

Target population |

Benefit |

Duration of the programme |

Beneficiaries |

Fiscal cost, % of GDP in 2019 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Family allowances - Asignación familiar – AF |

Low-income formal workers (earning less than 2.5 minimum wages) with children or other dependent family members |

Between 2% and 11% of the poverty line per dependent family according to household income. |

Automatic access and continuity always that conditions are met. |

243 300 workers |

0.03% |

|

Single family allowance - Subsidio Único Familiar (SUF) |

Informal workers (not receiving family allowances) with children under 18 years of age, pregnant women and people with disabilities belonging to the 60% most socio-economically vulnerable |

Conditional cash transfer of equal benefit amount per dependent family member, conditional on children’s schooling and health. CLP 12 000 monthly per child (USD 17.6, 10% of the poverty line). |

Up to three years. |

2 million workers |

0.16% |

|

Ethical Family Income - Ingreso Ético Familiar (IEF) from Seguridad y Oportunidades system |

- Families in extreme poverty - People aged 65 and over who live in poverty - People living on the street - Minors whose responsible adult is deprived of liberty. Families participating in the programme can also receive other social assistance benefits, including the SUF |

Contains two blocks: one of intervention and the other of cash transfers. One unconditional cash transfer of the 85% of the difference between the family income and the extreme poverty line. The maximum benefit received monthly is USD 15.7 (9% of the poverty line). It is supplemented by conditional cash transfers related to children’s schooling and health, an employment subsidy to promote female formal employment, and conditional cash transfers rewarding school achievements. |

Time-limited graduation scheme: up to 24 months receiving cash transfers 48 months for the women's work subsidy. |

101,900 people |

0.02% |

|

Permanent family allowance - Aporte Familiar Permanente (AFP) |

Low income households receiving one of the benefits above |

Once a year unconditional cash transfer of CLP 49 000 for dependent family member (25% of the poverty line) |

Automatic access and continuity always that conditions are met. |

1.6 million workers |

0.08% |

|

Total |

0.3% of GDP |

Note: The programmes in this table represented 80% of income support of households on average of total income-support in 2017. Other benefits are related to old-age, incapacity, and the water subsidy.

Source: OECD elaboration based on DIPRES, Cepal, ChileAtiende, Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, IPS, SUCESO.

The Ingreso Etico Familiar programme tends to bring families closer to the poverty line rather than helping them to overcome poverty due to its focus on families living in extreme poverty and the low benefit levels (Fernández and Calcagni, 2015[29]). Moreover, although the programme’ progressivity is high, its redistributive impact is limited (Amarante and Brun, 2018[30]). The impact of this programme on education attainment is also mixed (Henoch and Troncoso, 2013[31]). The cash transfer linked to school attainment (Bono por Logro Escolar) has been harshly criticized as it does not contribute to poverty reduction and the fact that being among the top of the class does not depend exclusively on the effort of the students, and it puts usually more pressure on the women of the household (MDSF, 2021[32]).

Evidence on the impact of social programmes on labour force participation and informality is mixed with some studies showing no impact and others small positive effects (Galasso, 2011[33]; Larrañaga and Contreras, 2010[34]; UDD, 2014[35]; Focus, 2016[28]).

Cash transfer programmes are fragmented, with weak coordination among different managing institutions and a lack of consistency with regards to eligibility criteria. Over the years, increased coverage has mostly been achieved by creating new benefits operating alongside existing ones (World Bank, 2021[9]). Insufficient information about the eligibility criteria and available benefits have reduced benefit take-up among low-income families (Fernández and Calcagni, 2015[29]).

Enhancing regular monitoring and evaluation of social programmes would support social spending efficiency. Information on the performance and beneficiaries of social assistance is still incipient, as are evaluations of their results (Hernando and Ross, 2017[36]). There have been significant recent efforts to improve the monitoring and evaluation of social programmes. There is still scope for analysing the systemic relevance and effectiveness of the different programmes more regularly and checking for duplications and overlap.

Chile invested more than most other Latin American country in economic and social relief to address the crisis. Spending in social emergency programmes was stepped up by 1.4% of GDP in 2020 and by another 6.5% of GDP in 2021. Social assistance policies included a series of additional emergency cash transfers through the pre-existing social assistance programmes and a new programme (Emergency Family Income, IFE) (Table 2.3). By December 2021, total spending on direct transfers reached 10% of GDP, with 65% of that spent on the new cash transfer programme. Chile is second only to Brazil in Latin America when it comes to the breadth and sufficiency of its cash-transfer response to Covid-19 during 2020 and a clear leader during 2021, even relative to the ten most advanced countries (IMF, 2021[37]).

|

Date |

Beneficiaries |

Benefit levels |

Fiscal cost, % GDP |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bono Covid |

April 2020 |

Beneficiaries of the SUF and the SSyOO, and informal workers in the poorest 60% of households according to the Household Social Registry, and who do not benefit from any other social assistance programmes |

CLP 50 000 per household, equivalent to 20% of the poverty line in an average household. |

0.07% |

|

Ingreso Familiar de Emergenia (IFE) |

May - October 2020 |

Families belonging to the 60% most vulnerable according to the Household Social Registry, with informal incomes – 4.9 million people (1.9 million households) |

1.3% |

|

|

Bono clase Media 2020 |

August 2020 |

All workers who before the pandemic had formal incomes equal to or greater than CLP 400 000 and less than or equal to CLP 2 million and have experienced a 30% reduction in these incomes – 1.7 million beneficiaries. |

CLP 500 000 |

0.3% |

|

Bono Covid Navidad |

December 2020 |

Same as IFE (Only for departments in confinement) |

CLP 55 000 |

0.1% |

|

Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia (IFE) |

January - March 2021 |

Only for those departments in confinement |

0.4% |

|

|

Bono Clase Media 2021 |

April 2021 |

Workers with formal incomes between the minimum wage and CLP 408 125 with no income reduction requirement. Workers with formal incomes between CLP 408 125 and CLP 2 million with an income drop of at least 20%. 1.9 million beneficiaries |

CLP 500 000. |

0.4% |

|

Broaden IFE |

April - May 2021 |

80% of most vulnerable households. Coverage is extender to households with other incomes, in which case the IFE complements incomes. |

CLP 100 000 per person, 80% of the poverty line |

1.6% |

|

Universal IFE |

June - November 2021 |

100% of Household Social Registry with household income per capita below CLP 800 000 - 7,2 million households (16,7 million people) |

Household with 4 members receives CLP 500 000, 1.5 times the poverty line |

6.2% |

Source: Secretariat using different sources of data including Ministry of Finance reports https://reporte.hacienda.cl/

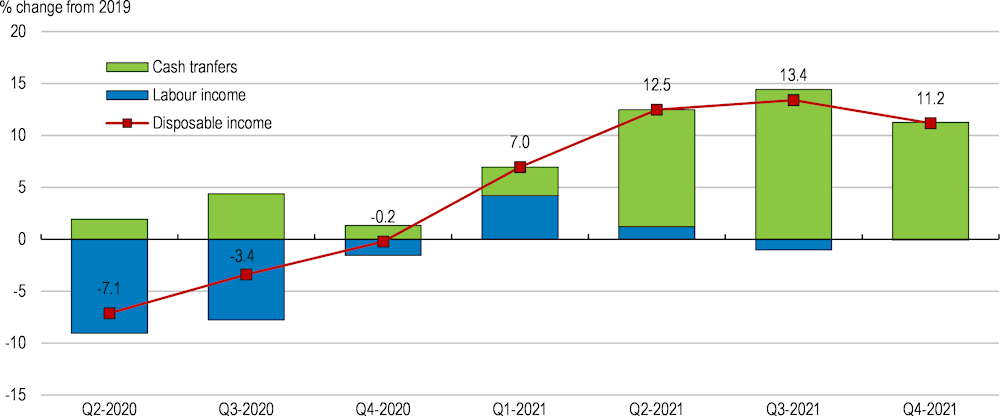

Cash transfers were well-targeted to the most vulnerable households in 2020 and managed to contain increases in poverty and inequality (Figure 2.13). However, cash transfers did not reach all those in need and failed to compensate for the fall in labour incomes (Figure 2.14), particularly among informal workers and vulnerable and middle-income households (CNEP, 2022[38]).

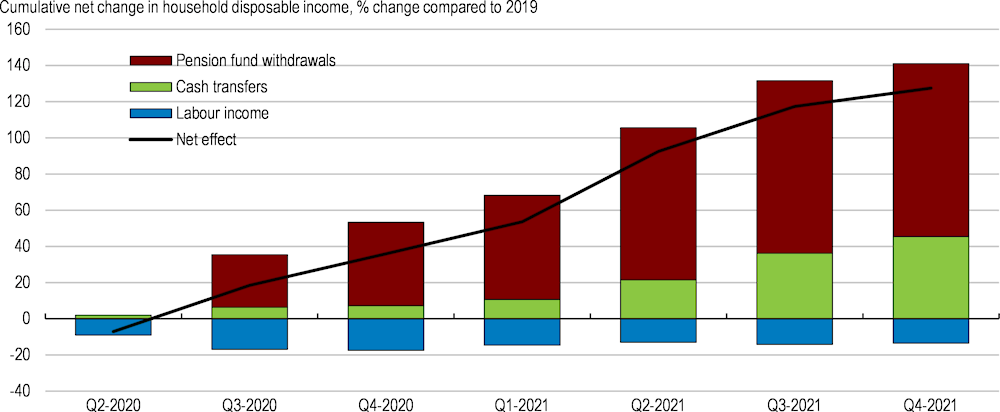

One clear lesson from the year 2020 is that more systematic measures to protect the economic security of the vulnerable population are needed. The initial implementation delay limited the ability to provide support in the early months of the crisis. Many workers received insufficient incomes or none at all during the first two months of the crisis. This delay also led to pressures on authorities to increase eligibility criteria and benefits during 2021, although the labour market was already recovering. This eventually led to an overcompensation of labour income losses, albeit too late (Figure 2.14). In addition, Congress introduced three constitutional reform bills over 2020-2021 that allowed all workers with positive balances in individual pension accounts to withdraw part of their pension funds overcompensating for the loss of incomes (Figure 2.15). These measures were not well targeted as they were not based on individuals’ specific and exceptional circumstances (OECD, 2020[39]), benefiting mostly the upper quintiles of the income distribution (Barrero et al., 2020[40]).

Year 2020

Overall, the large income support substantially mitigated poverty and inequality. Poverty was almost eliminated in 2021, mainly due to the rollout of the universal cash transfer programme (Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia, IFE). Inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, also dropped from 0.45 in 2020 to 0.39 in 2021. This improvement is likely to be temporary, as poverty (measured at USD 5.5 a day) and inequality are expected to increase to above pre-pandemic levels with the end of emergency transfers and the challenging macroeconomic conditions in 2022 (World Bank, 2022[42]).

Note: Changes in labour income relative to the same quarter of 2019 and based on total disposable income for that period. Estimates income changes for 21.III and 21.IV based on the central scenario of the Central Bank IPOM December 2021, while the amounts of income support are based on what is committed for quarters 21.III and 21.IV. Source: (CNEP, 2022[38]).

Note: Accumulated changes in labour income relative to the same quarter of 2019 and based on total disposable income for that period. Estimates show income changes for 21.III and 21.IV based on the central scenario of the Central Bank IPOM December 2021, while the amounts of income support are based on what is committed for quarters 21.III and 21.IV.

Source: (CNEP, 2022[38]).

The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic calls for a more comprehensive, flexible, and sustainable social protection system. Protection against poverty and income losses could be improved by unifying and integrating existing cash transfers into a single programme to fight poverty. One option would be to establish a single cash transfer for those aged below 65 living in poverty population that would top up incomes so as to guarantee a certain minimum income to all. This programme could also provide a backstop to those who lose their livelihoods temporarily in the case of dismissal. Unifying all income support into one programme would simplify the delivery of social benefits, reduce bureaucracy, increase transparency and improve spending efficiency.

In practice, this proposed benefit would function as a periodic cash transfer to every adult below 65 living in a poor or vulnerable household. The design of this cash benefit could be based on the experience of the successful Ingreso Ético Familiar and maintain its conditionalities on education and health. The size of the transfer would be contingent on household income before transfers (both from formal and informal jobs) and their assets. When children are part of the household, the cash transfer could be conditional on school attendance and health check-ups, as in the Ingreso Ético Familiar or Subsidio Familiar Único programme. This has proven effective in helping families to exit poverty. The cash transfer would decrease gradually as the household income increases, until eventually reaching zero. That would set the scheme apart from the existing cash transfers schemes that provide a fix amount of money to every household. Only Ingreso Ético Familiar takes the distance of household income from the poverty line into account. The new scheme would be financed from general tax revenues. The proposed scheme is different from a Universal Basic Income, which grants an identical amount to every citizen, regardless of their income (Box 2.4). A Universal Basic income would not be fiscally viable in Chile, nor would it be effective to fight poverty.

A universal basic income (UBI) is an unconditional cash transfer granted at regular intervals to all residents, regardless of their wealth, earnings or employment status. The main advantage of such a programme is that it is simple to implement as no conditions or requirements are applied.

The main disadvantage of an UBI is that it could be extremely costly. An unconditional payment to everyone at meaningful but fiscally realistic levels would require strong tax rises and possibly reductions in existing benefits, and would not often be an effective tool for reducing income poverty (OECD, 2017[43]). Some disadvantaged groups would lose out when existing benefits (usually all other social programmes) are replaced by a universal basic income, illustrating the downsides of social protection without any form of targeting at all.

As in most countries, the Universal Basic Income is fiscally unviable in Chile and can be controversial by guaranteeing transfers to high-income earners. Setting the monetary transfer to the extreme poverty line to every household member to assure that the most basic needs of all Chileans are satisfied even if no other income is available, would have a cost of 9.9% of GDP in 2017. This UBI level still would leave many households in poverty, especially those at old-age not receiving any pensions or the unemployed or inactive. If the transfer is set to the poverty line the cost would be 14.9% of GDP, almost three quarters of the tax revenues in Chile (20% of GDP in 2019).

A large body of evidence suggests that cash transfers can achieve significant reductions in poverty. These cash transfers can promote credit access, better eating habits, better school attendance, better academic results, better cognitive development, reduction of domestic violence, and female empowerment (Banerjee, Niehaus and Suri, 2019[44]). Evidence on the impact of cash transfers on labour participation and formal employment are mixed (OECD, 2011[45]). While some evidence suggests that cash transfers do not discourage - and in some cases even encourage - labour participation by beneficiaries (Banerjee et al., 2017[46]), other evidence from Latin America suggests that the exact design matters, as cash transfers can decrease incentives to participate in formal employment (Bergolo and Cruces, 2021[47]). This formal labour supply effect is usually linked to abrupt benefit withdrawals for beneficiaries who find a job and earn incomes above the benefit eligibility thresholds, which can imply high implicit tax rates.

To maintain incentives for formal work, graduation from cash transfers should be gradual. In particular, the value of the forgone transfer should always be smaller than the additional work income when a beneficiary moves into (formal) employment. Otherwise beneficiaries might be reluctant to take up work for fear of losing their benefit. The design could include a phase in which for every additional peso earned, only part of the self-declared additional earnings are taken into account to calculate the cash benefit, until gradually reaching benefit withdrawal. Tying benefits to individual behaviour that promotes future employment outcomes such as school completion, training and participation in public employment services would also help families to graduate from social assistance. Ex-ante and ex-post impact assessments should be systematically conducted to evaluate the effects on (formal) labour force participation and adjust the design if necessary.

The poverty line could be a useful benchmark for determining benefit levels. By calculating the cash transfer as the difference between the household income and the poverty line (taking into account household size), the programme would ensure that no household or individual is left in poverty. Benefit levels could consider specific household characteristics. One example is the Spanish guaranteed minimum income programme implemented in 2020, in which a certain amount is added to the benefit for each additional household member or for single-parent households. The programme was introduced in parallel with the gradual phase-out of the existing Child Benefit scheme.

While this cash transfer programme should not necessarily be limited in time, periodic reassessments should be undertaken. The programme should be accompanied by strengthening underlying information systems and verifying self-reported household information, to provide incentives for individuals to report their income and wealth truthfully. Penalties for providing inaccurate or false information could strengthen these incentives.

A related alternative to this cash transfer programme would be a negative income tax or earned income tax credit. Evidence shows that the Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States has raised labour force participation, particularly among single mothers (Hoynes and Patel, 2017[48]). There are also positive effects on poverty reduction, as the programme rewards work and supplements the income of low-wage workers. Similar programmes have also decreased informal employment in developing countries (Gunter, 2013[49]).

The salient distinction between the proposed cash transfer programme and the negative income tax is that the latter is financed directly through a progressive income tax. Another important difference is that in the case of the guaranteed minimum income part of the transfer can be conditional on educational and health behaviours. Finally, a network of social workers is in charge of verifying and constantly improving data on vulnerable households while raising awareness of available benefits.

Chile has accumulated almost 40 years of experience in the development and use of targeting instruments for the allocation of social benefits. The Social Household Register, the current social information system, has achieved a wide coverage of the population, about 75% in 2020, with a good coverage of most of the 40% vulnerable population, with 62% of households registered. Despite this coverage, there is significant heterogeneity at the local level, with communes with most vulnerable populations having lower coverage (CNEP, 2022[38]).

Efforts to increase coverage should continue with a view towards covering the whole population. This is key for providing better socioeconomic information for designing and implementing new social programmes and entitlements as well as for monitoring existing ones (Berner and Van Hemelryck, 2021[50]). Automatic registration of all citizens could help, as in the case of Uruguay, where an integrated information system gathers data and administrative records from more than thirty institutions.

The social information system needs to adapt to respond more quickly and efficiently to shocks faced by households. The relatively slow response during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic was partly due to the complexity of the registration and updating procedures within the social registry. Registration focused mainly on manual fact-checking of self-reported household information, rather than relying on background verification procedures based on available administrative data. As a result, the system was not able to reflect the new economic situation of households in a timely manner. There have been significant efforts to include administrative databases and make the registry more responsive.

Enhancing the capacity of social programmes to respond to crises would require improving the real-time nature of the database and developing a targeting instrument that captures short-term or sudden changes in individuals and households’ income status (Berner and Van Hemelryck, 2021[50]). For example, Brazil has used self-declared per capita household income to deliver Bolsa Familia benefits, its main cash transfer programme, and this has shown to be a good targeting instrument (WWP, 2017[51]). This requires fast cross-checks of income data with other data sources and a high interoperability between registries to reflect immediately changes in labour market status or household income. Doing so would enable social policy to protect those facing income shocks even if they do not live in structural poverty.

Sustained progress with the social registry could also be achieved by merging additional administrative databases and further increasing the interoperability among them. For example, Estonia uses advanced digital tools and designed a data exchange layer for whole-of-government called X-Road. The objective is to allow citizens, businesses and government entities to securely exchange data and access information maintained in various agencies’ databases over the internet.

Implementing a universal income tax declaration and merging it with the social registry would make more reliable information on income available and allow for better cross-checking of income data. Tax declarations are typically used in advanced OECD countries for the targeting and delivery of social benefits. Although many Chileans do not pay taxes, filling a tax declaration could increase awareness and help strengthen a culture of tax compliance.

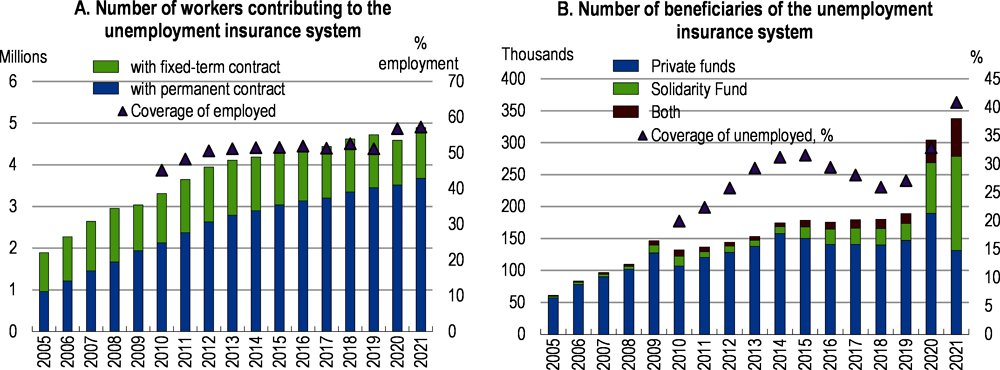

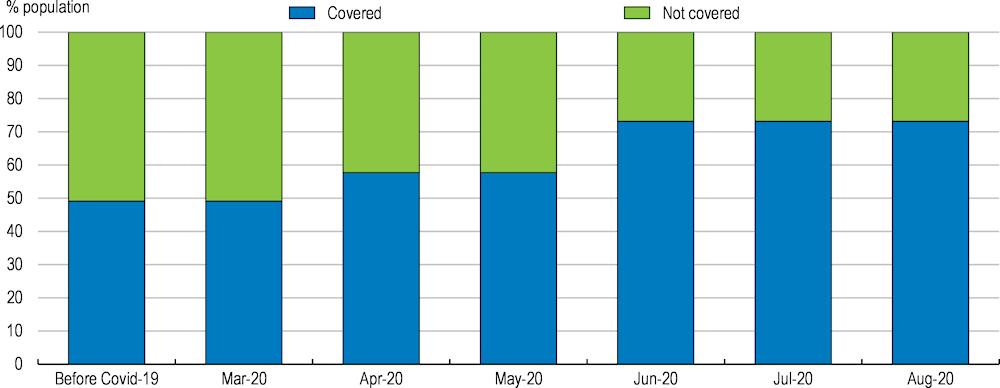

Chile is one of the few countries in Latin America with unemployment insurance for formal workers (Box 2.5). The number of affiliates and beneficiaries of the unemployment benefit system has increased constantly since its creation, but remains low (Figure 2.16). Between 2010 and 2020, the percentage of employed people who contributed and are covered increased from 50% to 60%, as a result of a decrease in informal and self-employment. Despite this increase in coverage, as of the first quarter of 2020, 31% of the employed had no coverage against unemployment and 13% were contributing to the system but did not meet the eligibility conditions (ILO, 2019[52]).

The low coverage reflects frequent informality and self-employed jobs, but also short duration of employment contracts and their high turnover (Huneeus, Leiva and Micco, 2012[53]; ILO, 2019[52]). Only 50% of employees that terminate a contract in a given year have enough contributions in their accounts to access benefits. Moreover, 50% of workers with fixed-term contracts had non-contributing periods lasting more than three months from the same employer in 2015, which impedes their access to the Solidarity Fund (Sehnbruch, Carranza and Prieto, 2019[54]). Hence, the unemployment benefit system protects workers with higher income levels and more stable jobs much better than it protects vulnerable workers, who are also much more likely to become unemployed (Sehnbruch, Carranza and Contreras, 2020[55]).

Source: Secretariat calculations using Superintendencia de Pensiones de Chile and INE data.

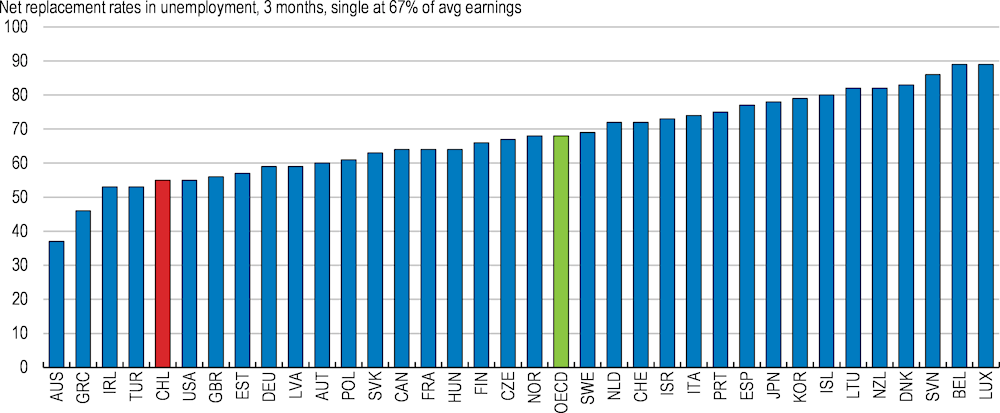

Benefit levels remains limited (Figure 2.17). While the unemployment insurance offers a replacement rate of 70% in the first month, it progressively declines to 30% from the sixth month, against an average of 61% after six months in OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2022), Benefits in unemployment, share of previous income (indicator). doi: 10.1787/0cc0d0e5-en.

The Chilean unemployment benefit system, in place since 2002, is based on individual accounts with complements from a solidarity fund. While individual accounts are financed through mandatory contributions from dependant workers and its employers, the solidarity fund is financed by employer’s contributions and complemented with general taxation. In this system, workers need to fulfil certain requirements to withdraw money from the unemployment individual savings accounts or accessing the solidarity fund related to number of months that they have been contributing (Table 2.4). Workers on permanent contracts have also the right to severance payments. The legal severance pay is an amount equal to one month of salary for each year worked, with a maximum of 11 months. The severance payments are relatively high with respect to the average OECD country, and also in Latin America (OECD, 2018[5]).

One advantage of individual unemployment savings accounts over other unemployment insurance systems is that they significantly limit the risk of moral hazard (ILO, 2019[52]; OECD, 2011[45]; OECD, 2018[56]). By allowing workers to run down their personal savings during periods of unemployment, workers internalise the cost of unemployment benefits, thus strengthening the incentives of the employed to prevent job loss and of the unemployed to return to work quickly. Individual unemployment savings accounts can also strengthen incentives for working formally since social security contributions are less perceived as a tax on labour and more as a delayed payment (OECD, 2018[57]). Additionally, contributions accumulated during the employment career are not withdrawn by the worker, any surplus could be credited in the form of pension entitlements upon retirement, which could be also perceived as savings for retirement. The disadvantage of individual unemployment savings account system is that generally individuals with lower contributory capacity, who also tend to have a higher risk of unemployment, tend to receive insufficient protection. This is partially addressed by the Solidarity Fund that can be accessed once the individual accounts have been exhausted and it is financed by worker’s contributions and general taxation.

|

Contract type |

Contributions to individual accounts |

Contribution to the Solidarity Fund |

Requirement for access when unemployed |

Benefits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

To individual accounts |

To the Solidarity Fund |

||||

|

Permanent contract |

Worker 0.6% of wages Employer 1.6% of wages For a maximum of 11 years |

0.8% of wages for all the duration of the contract |

12 continuous or discontinuous contributions in the last 24 months. Voluntary or involuntary termination of contract. |

12 contributions in the last 24 months. The last three contributions need to be done continuously and from the same employer. Having insufficient resources in individual account. Dismissal due to unforeseeable circumstances, force majeure or due to the needs of the company. |

In the first month, 70% of the average wage of the last 6 or 12 months. This percentage falls progressively to 30% from the sixth month onwards. Workers receiving the benefits from the individual accounts can collect benefits until their balance is exhausted. The Solidarity Fund covers up to the fifth month (if permanent worker) or third month (if fixed term worker). For fixed-term workers the replacement rate starts are 50%, 40% and 35%. The benefit received is in proportion of the average earnings of the last 12 months and has maximum and minimum caps. The benefits received from the Solidarity Fund are conditional on enrolment in public employment services. |

|

Fixed-term contract |

Employer 2.8% of wages |

0.2% of wages |

6 continuous or discontinuous contributions in the last 24 months. The last three contributions need to be done continuously and from the same employer. Proof of termination of contract. |

||

Source: OECD Secretariat.

To increase protection of formal workers, authorities increased coverage and benefits of the unemployment benefit system during the social unrest in late 2019, and then because of the pandemic. In April and again in September 2020, the replacement rate was raised to 55% from the third month of unemployment onward, and the minimum and maximum benefits were increased. Eligibility criteria were reduced to 6 months of contributions in the last 12 months. These changes were temporary until October 2021. Additionally, in 2020 a job retention scheme (the employment protection law -Ley de Protección del Empleo) which allowed firms and workers to agree on the suspension of employment contracts during lockdowns, enabling them access to the unemployment benefit system. It also introduced a short-time work scheme with the possibility of negotiating a 15-50% reduction in working time, while receiving income support from unemployment benefits. The job-retention and short-time work schemes benefitted around 1.1 million workers in formal jobs (around 18% of formal workers) up to December 2021, which mitigated formal job losses (CNEP, 2022[38]) and had a positive effect on workers returning to their jobs (Granados, Rivera and Villaseca, 2022[58]).

To fill the gaps of the unemployment insurance system and increase protection of informal workers, authorities implemented emergency cash transfers, as discussed in the previous section. However, at least during 2020, there was still a significant gap in the protection against income loss (Figure 2.18), which was mainly concentrated in informal and self-employed workers (Montt, Ordóñez and Silva, 2020[59]).

One clear lesson from the pandemic is that Chile, as many other countries with many vulnerable workers, cannot rely on unemployment insurance alone to protect workers from the fallout of an economic crisis or rapid changes in the labour market that generate unemployment. The unemployment benefit system need also to be linked to other social protection mechanisms to provide a minimum income-protection to workers with precarious jobs.

Note: Those covered includes those using the unemployment benefit system and the emergency cash transfers.

Source: (Montt, Ordóñez and Silva, 2020[59]).

Implementing the single cash benefit programme for the vulnerable, as discussed previously, could improve the income protection for dismissed workers from vulnerable backgrounds. As it provides a backstop for all those losing their job or income, regardless of the type of job (fixed-term or informal job), it could serve as universal pillar of protection in case of job displacement. This would allow to close the existing unemployment benefit insurance gaps systematically without the need of designing ad-hoc measures during emergencies or crisis, as evidenced during the pandemic. In practice, for workers earning the minimum wage, a cash benefit equivalent to the poverty line would imply a replacement rate of around 50%. To implement the single cash benefit programme, it will be crucial that the targeting system and the Household Social Registry become more agile and able to detect, or at least verify, changes in workers’ labour market status and income without long delays.

As the cash benefit scheme is designed to avoid poverty, a second contributory pillar, based on the existing unemployment insurance system, could top-up benefits to provide consumption smoothing and maintain living standards for higher-income dismissed workers. This second pillar would be financed from individual savings accumulated by workers.

Implementing reforms to the current unemployment benefit system would deliver better protection for workers during dismissals, for example by doing permanent some of the changes to the unemployment insurance system during the crisis, or, at least, automatically triggered when unemployment reaches certain thresholds. Reducing the required minimum contribution periods for fixed-term contract workers would improve coverage and benefits for jobseekers. The short-time work scheme—in which workers accept a temporary reduction in work hours and pay, and the government bridges some of the resulting income gap—could also be made permanent, as has shown to be a useful instrument during the pandemic. These schemes have been successfully used in many OECD countries even before the pandemic. Two good examples are the cases of Austria and Germany that have been successful protecting jobs when there was a temporary lack of labour demand (Balleer et al., 2016[60]).

There are several benefits to this approach. Most importantly, it would expand protection in the case of dismissal to all workers without distinguishing by type of workers, allowing informal and workers with contracts of short duration to access income support. Low-income informal workers or workers under short-term contracts that could not access the unemployment insurance system, even if they contributed for some time, would access income support through the single cash transfer programme during unemployment, while at the same allowing them to access for training or public employment services. Higher-income workers would receive the cash transfer and the top-up coming from the unemployment insurance system, which would allow for a more adequate replacement rate during unemployment. Secondly, it would allow reducing social contributions increasing the incentives for formality and guaranteeing coverage of the social protection. Third, it would also allow job seekers to look for jobs without the immediate concern for minimum survival. Doing so, the programme would increase the bargaining power of workers to obtain fair wages without relying on the minimum wage, which generates distortions against the generation of formal work.

Beneficiaries of the cash transfer programme and the unemployment insurance system would need to be automatically registered with the labour market intermediation services to support the search for employment and training. Strengthening the institutional capacity of the Public Employment Service is needed to improve the quality of services provided. Improving quality and relevance of the job training system will also be essential. In Chile, the skills gap is wide and the job training system doesn’t help to bridge this gap. Professional training is not always of good quality and is insufficiently aligned to the needs of the labour market (CNP, 2018[61]). Additionally, it does not reach those that need training the most, such as the unemployed or vulnerable workers (OECD, 2021[6]).

Moving towards an effective governance of the training system with a clear national regulatory framework and a clear national plan would help, as recommended in previous Economic Surveys of Chile (OECD, 2018[5]; OECD, 2021[6]). A full revision of the training system and better aligning training courses with labour market needs will be paramount for a well-functioning training system. The productivity commission has recommended redirecting all public resources for training, including those of the tax credit for training (Franquicia Tributaria), to a training fund (CNP, 2018[61]). The fund should focus on those that need training the most, unemployed, inactive and those working on non-standard contracts and vulnerable workers.

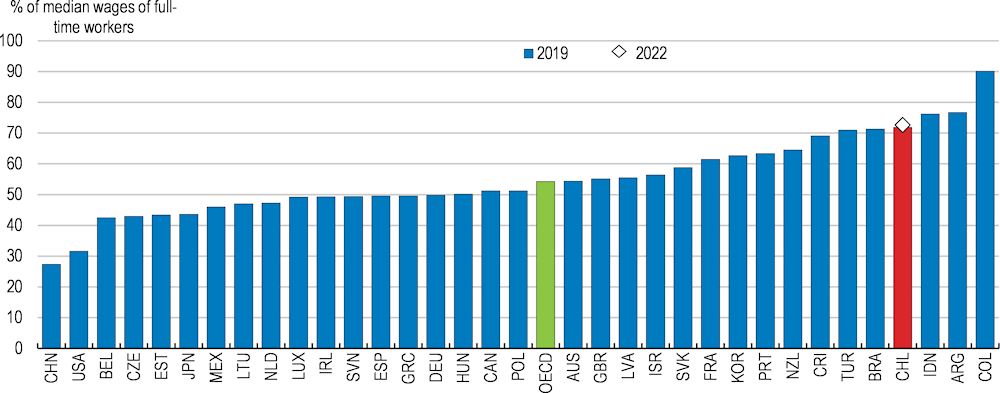

In relative terms, Chile’s minimum wage - at 72% of the median wage and 48% of the mean wage of full-time employees in 2019 - is high in comparison with other OECD countries (Figure 2.19). Authorities increased the minimum wage on two occasions during 2022, in May and August. This has lifted the minimum wage by a total of 18.7% relative to 2021, to CLP 400 000, more than offsetting high inflation, which stood at 14.1% year-on-year in August 2022.

Statutory minimum wages are usually the most direct policy lever governments have for influencing wage levels, especially at the bottom of the distribution. International evidence on the impact of minimum wages on employment is not conclusive (Broecke, Forti and Vandeweyer, 2017[62]). Based on a review of the evidence, OECD (2015[63]) concludes that the impact of moderate minimum-wage increases on employment tends to be small in both advanced and emerging economies, although effects on some vulnerable groups – such as youth – may be more negative. For developing countries characterised by the co-existence of formal and informal employment, minimum wages that are too high and not effectively enforced may cause employees to be displaced or shifted from formal to informal employment (Nataraj et al., 2013[64]; Del Carpio and Pabon, 2017[65]).

Ultimately, the impact of minimum wage increases depends on the current level relative to the wage distribution, but also how binding it is, the degree of compliance and enforcement, competition in labour and product markets and behavioural responses of employers (OECD, 2018[57]). For Chile, one study shows that minimum wage increases have had small and positive effects on formal wages, and non-significant effects on formal employment (Grau, Miranda and Puentes, 2018[66]). In the context of a relatively low minimum wage in Brazil in the early 2000s, one study finds no negative impact on overall formal employment in response to minimum wage increases, but the study does find negative impact for groups more exposed to the minimum wage (Saltiel and Urzúa, 2020[67]). Another study for Argentina finds that minimum wage increases have had a small impact on formal sector wages, but have increased wages in the informal economy (Khamis, 2013[68]). This may be explained by the “lighthouse effect”, i.e. a signal given by the minimum wage to workers and employers in the informal sector about socially acceptable minimum levels of pay. Some empirical studies show that minimum wage hikes tend to reduce wage inequality (Engbom and Moser, 2018[69]; Maurizio and Vázquez, 2016[70]). Still, there are limits to what minimum wages can achieve. When the minimum wage is set too high, it can cause significant job losses or shifts to informality and hence have undesirable distributional effects.

Further increases in the minimum wage in Chile will need to be carefully evaluated as they could potentially lower formal employment prospects, especially for low-skilled workers, and people located in rural and less developed regions. This is particularly relevant in the context of other reforms that could increase the labour costs of formal employment. This effect is somewhat mitigated by differentiated minimum wage provisions for youths and for the elderly, two groups with traditionally weak attachments to the labour market. The authorities have implemented temporary subsidies to help SMEs adjust to the recent increases in minimum wages and lower the risks of job displacement or informality. The subsidy covers around 50% of the minimum wage per worker, being more generous in the first months. Some countries, most notably France, have introduced sizeable reductions in employer social security contributions for workers at around the minimum wage, thereby lowering the ratio of minimum-to-median labour costs below that of the minimum-to-median wage. Other countries have also used targeted reductions in income taxes for low-wage workers (OECD, 2018[57]).

In the medium term, a permanent and independent commission could provide recommendations on setting minimum wage increases, as in other OECD countries (OECD, 2018[57]). For example, the process of setting minimum wages in Germany and the United Kingdom includes a systematic monitoring of its potential employment impact by specific independent bodies mandated to evaluate and provide recommendations (Low Pay Commission UK, 2018[71]; Eurofound, 2018[72]; Vacas-Soriano, 2019[73]). The Low Pay Commission in UK is formed by experts and academics, and is mandated to evaluate and advise the government on the impact of increasing the minimum wage. The commission conducts research and publishes annual reports to inform the debate on minimum wages and its impact on employment. This advice could then feed into the social dialogue and negotiations between social partners and authorities for setting the minimum wage.

Note: Median gross monthly earnings of full-time employees (working 30 or more actual hours per week on the main job). Exactly half of all workers have wages either below or above the median wage for the OECD countries. Data source median wages for Chile is CASEN adjusted by the nominal index of remuneration (IR-ICMO) from the National Statistics Institute. Year 2022 for Chile is an estimation considering the legislated minimum wage in August 2022 (CLP 400 000) and an increase of annual nominal median full-time workers wages of 13%. Percentage of minimum to average wage 2017 for China, Indonesia.

Source: OECD, OECD Employment Outlook Database; Chile: Ministry of Finance; China Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, National Bureau of Statistics; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios); International Labour Organisation (ILO) Database on Conditions of Work and Employment Laws; Ministry of Man Power and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia and Statistics Indonesia (BPS); National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina.

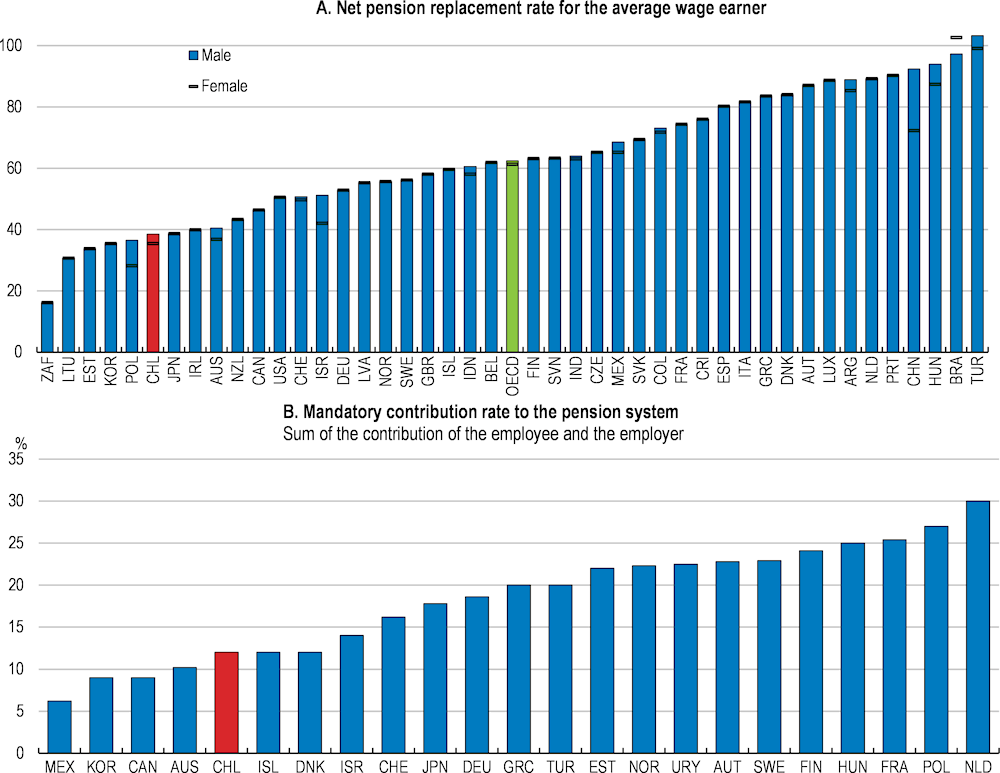

Chile was the first country to replace a traditional pay-as-you-go system with a mandatory fully funded individual capitalization pension system based on a defined contribution and private administration of the funds (Box 2.6). A public non-contributory pillar complements the private capitalization funds delivering better coverage and benefits for low-income workers and has been shown to reduce substantially old-age poverty (Centro UC, 2017[74]). However, the social unrest of 2019 made clear that many Chileans were facing inadequate pension benefits pushing the government to increase benefits of the non-contributory pensions and finally introduce a new universal guaranteed minimum pension in early 2022, increasing benefits and coverage. Nonetheless, political demand for further reforms of the current contributory pension system remain significant.

Chile was the first country to replace a traditional pay-as-you-go (PAYG) system that offered a defined benefit with a fully funded pension system based on a defined contribution that financed individual capital accounts managed by private fund managers in the early 1980s. A parallel PAYG system was kept for the police and armed forces. Early assessments linked the new pension system with growing private savings and with the development of the depth of local financial markets (Roldos, 2007[75]) supporting economic growth (Corbo and Schmidt-Hebbel, 2003[76]). The apparent success of the Chilean experience sparked a wave of pension reforms in Latin America and other emerging markets.

Probably the most important change to the pension system was the creation of the solidarity pillar in 2008, a non-contributory pension scheme providing a minimum benefit to those aged more than 65 that belong to the 60% more vulnerable population. It was composed by a minimum benefit for those who did not participate in the pension system (Pensión Básica Solidaria) and another benefit to retired workers whose monthly pensions financed by individual account assets did not reach certain thresholds (Aporte Previsional Solidario). Since then, the pension system consists of three components: a redistributive poverty-prevention tier, a mandatory individual account tier, and a voluntary savings tier.

At the beginning of 2022, the Government approved a new guaranteed universal pension for people over 65 years of age who do not belong to the richest 10% of the population. The new benefit replaces the solidarity pillar. The value of the benefit is almost one poverty line (CLP 193,000 – USD 231 a month) for those with self-financed pensions up to CLP 630 thousand (1.6 times the minimum wage at the end of 2022) and a decreasing supplement for persons with self-financed pension between CLP 630 thousand and CLP 1 million (2.5 times the minimum wage). Self-financed pensions are top-ups to this minimum floor, and, if any, voluntary savings would be added.

There is also a universal Grant per Child (Bono por Hijo) for women, where the mother is eligible for an additional supplement once she reaches 65 years old. The supplement is equivalent to 18 months of contributions at 10% over the minimum wage set in place at the time of birth for each child, plus the average net rate of return on defined contribution pension plans from the date of the birth until the benefit claim (about USD 12.70 in 2020 per month).

In the second tier, workers contribute 10% of their wage to an individual account and choose a private-sector Administradora de Fondos de Pensiones (AFP) with which to invest their pension contributions. Administrative fees, of around 1.16% of wages, are levied on top of the contribution rate (not out of the mandatory contribution). There is a ceiling on covered earnings, which in 2020 was equivalent to CLP 2 700 000 (around 7 times the minimum wage). Employers are not required to contribute to employees’ AFPs, although since 2008 employers have been required to pay the premiums for workers’ survivor and disability insurance, which are provided by private insurance companies. Upon retirement (65 for men and 60 for women), the worker may withdraw assets that have accumulated in the individual account as an immediate or deferred annuity or through programmed withdrawals. Coverage may become effective before that age if the person is declared disabled, being older than 17 and younger than 65 (disability pension). The third tier allows workers to supplement retirement income with voluntary, tax-favoured savings. Workers never lose their contributions because there is no minimum period required to qualify for a pension.

Early retirement is allowed at any age in the defined contribution scheme as long as the capital accumulated in the account is sufficient to finance a pension above certain thresholds. The first condition is that the benefit must be at least equal CLP 399 500 (close to the minimum wage in 2022). The second condition is that the pension must be at least equal to 70% of the average income in the ten years prior to claiming a pension. The normal retirement age is reduced by one or two years for each five years of work under arduous conditions in specific occupations. The maximum reduction of the normal retirement age is ten years.