Hyunjeong Hwang

Economics Department of the OECD

Axel Purwin

Economics Department of the OECD

Jon Pareliussen

Economics Department of the OECD

Hyunjeong Hwang

Economics Department of the OECD

Axel Purwin

Economics Department of the OECD

Jon Pareliussen

Economics Department of the OECD

Social protection in Korea is designed around traditional forms of employment, and excludes a substantial share of workers in non-standard employment. The resulting social protection gaps compound income inequality and undermine financial sustainability. Furthermore, Korea’s tax and benefit system may discourage taking up or returning to low-paid work from social assistance or unemployment benefits. Expanding the reach of employment insurance while redesigning the tax and benefit system could boost work incentives and reduce inequality and poverty. The elderly poverty rate is persistently high, partly because public pensions and social insurance were introduced relatively recently. Better targeting the means-tested Basic Pension could reduce elderly poverty considerably. Lengthening working lives is essential to ensure pension sustainability and adequate retirement income for future retirees. Shifting from a severance pay system to a corporate pension would help improve retirement income and lower employers’ incentives to push for early retirements. Reducing inequalities in health and long-term care will require expansion of primary care and affordable quality home-based care. This will also help address the overreliance on hospitals and cope with the surging demand for health and long-term care.

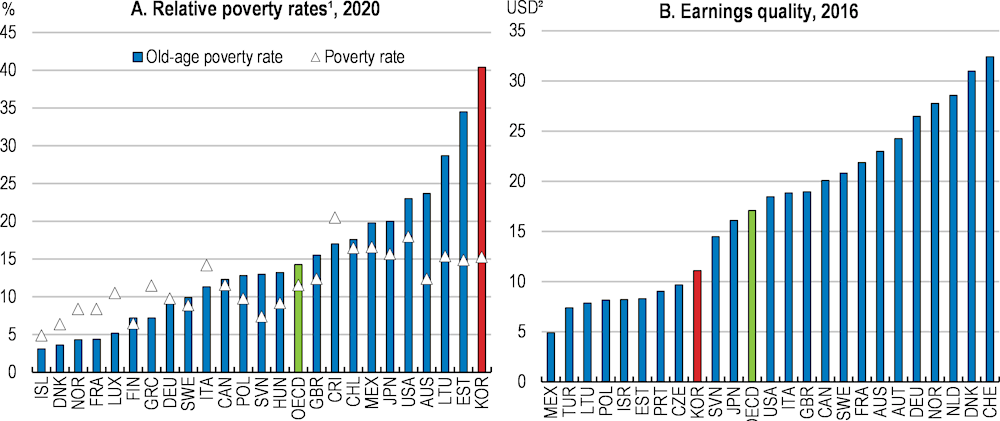

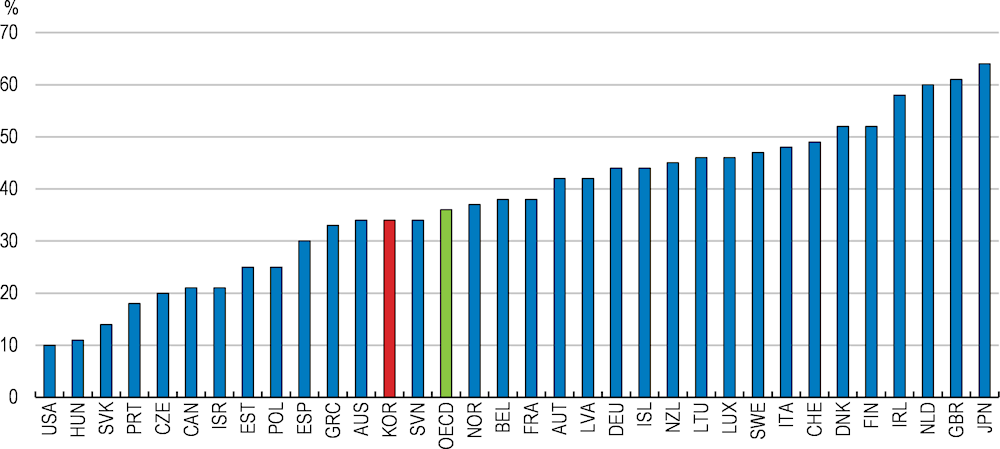

Korea’s income per capita (on a PPP basis) rose rapidly over the past decades, surpassing the OECD average in 2020, but social inclusion failed to keep pace with the economic take-off. Income inequality and relative poverty rose substantially after the 1997 Asian financial crisis and have remained persistently high in recent years, while many workers still struggle with jobs of poor quality (Figure 2.1, Panels A and B). Rapid technological progress and globalisation, coupled with labour market dualism and large productivity differentials between large companies and small and medium-sized enterprises, are further intensifying the pressures on inequality.

1. The poverty rate is the share of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population. 2019 data for Canada, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Slovenia, United Kingdom and USA, 2018 data for Australia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Japan and Poland and 2017 data for Iceland and Chile.

2. The earnings quality index adjusts gross hourly earnings in USD for inequality using Atkinson’s inequality index. This index captures the loss of welfare as a percentage of the arithmetic mean due to inequality in the earnings distribution. For details, see Chapter 3 in OECD Employment Outlook 2014.

Source: OECD (2022), Income distribution (database).

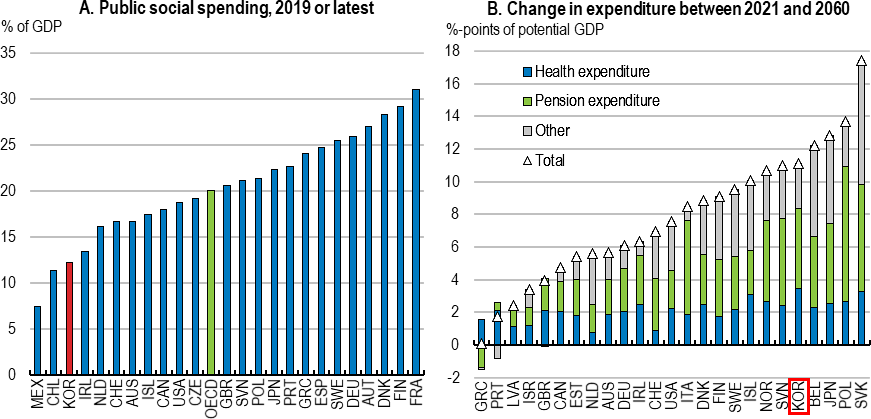

At the same time, Korea is facing spending pressures from a rapid demographic transition. Korea’s social spending is currently 12% of GDP, well below the OECD average, partly reflecting Korea’s still young population and small pension entitlements in a pension system that has been operational for less than 35 years. However, these factors are set to reverse in the coming years reflecting rapid population ageing. Under existing settings, public spending is expected to almost double by 2060 with the largest increases in spending related to ageing (Chapter 1).

Addressing inequality and poverty is high on the policy agenda. Old-age poverty in Korea is high, and gaps in income and social protection between regular and non-regular workers are large. The COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-regular workers, has further highlighted the importance of ensuring adequate social protection. Against this background, this chapter explores ways to improve the social safety net for both working-age and old-age people, with a view to identify cost-effective solutions and secure long-run financial sustainability. Some recommendations presented in the chapter will entail increased spending, while others, notably increasing the pensionable age, but also improving work incentives and promoting healthy ageing, can yield considerable fiscal savings (Chapter 1). On balance, the proposed package of measures is not expected to yield additional fiscal costs in the long term. However, timing matters. Proposals to boost eligibility to tax-financed benefits would increase net public spending. In contrast, expanding social insurance coverage would increase social insurance contributions immediately, while liabilities would build over time.

Dualism is deeply entrenched in Korea’s labour market. Regular workers receive high wages, social insurance coverage and strong employment protection. Other workers, including non-regular workers and self-employed, work in precarious jobs, earn lower incomes and are less likely to be covered by social insurance. Self-employed, for instance, mostly operate small-scale businesses with short life spans (around 70% of small businesses in operation in 2018 and 2019 were less than five years old) and their employment insurance coverage was only 0.6% in 2021 (KEIS, 2021; Statistics Korea, 2020). Tackling this situation will require a significant improvement in Korea’s main working-age benefits: i) employment insurance (EI); ii) Basic Livelihood Security Programme (BLSP); National Employment Support Programme (NESP); and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (Box 2.1).

The Korean safety net for the working-age population consists of four main benefits:

Employment insurance (고용 보험, EI): EI, an unemployment benefit scheme, provides income replacement benefits as well as vocational training and education support for workers who lose their job involuntarily. These benefits are financed by contributions. The unemployment benefit premium rate amounts to 1.8% of the worker’s gross wage and is shared equally by employee and employer. In addition, employers pay a premium of 0.25% – 0.85% for employment security and vocational development programmes. To qualify for unemployment benefits, the person must have worked at least 180 days in the past 18 months, and unemployment must be involuntary. The maximum duration of the benefit is 270 days.

Basic Livelihood Security Programme (기초생활보장제도, BLSP): BLSP is a means-tested social assistance programme providing in-kind and cash benefits to households in absolute poverty. The BLSP consists of four categories of benefits: livelihood, health, housing and education. The income threshold is 30% of the median for the livelihood benefit, 40% for health, 46% for housing, and 50% for education. To determine eligibility for the health benefit, the income of any children and parents is included in the means test. BLSP is co-funded by local governments (20%) and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (80%). In the case of Seoul, the programme is funded on a 50-50 basis. BLSP recipients able to work participate in self-sufficiency programmes to help them find employment or start a business.

National Employment Support Programme (국민취업지원제도, NESP): NESP is a tax-financed unemployment assistance for jobseekers who are entitled to neither EI nor BLSP. The support is targeted at low-income people, youth (aged from 18 to 34), and other groups at a disadvantage in the labour market, such as career-interrupted women and marriage-based immigrants. Those with an income below 60% of the median or youth with an income below 120% of the median can receive both an allowance (up to 500 000 won for a maximum of 6 months) and employment support services (e.g., training, counselling, and job search support). For those with an income between 60 and 100% of the median, youth with an income above 120% of the median, and other vulnerable people, only employment support services are available.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The purpose of the EITC is to alleviate the situation for the working poor and to strengthen work incentives. Similar to EITC systems in some other countries, the amount of tax refunded to the worker increases with income at the lower levels and then decreases again as the household approaches the eligibility limit. The eligibility limit and benefit size depend on the household type. The maximum amount of EITC, not including any Child Tax Credit (CTC), ranges from KRW 1.5 million per year for single households to KRW 3 million for two-earner households. The CTC is paid for up to three children in addition to the EITC. The maximum amount of CTC is KRW 0.7 million per child.

Note: KRW 1 million ≈ EUR 750.

Source: OECD, 2018a; Ministry of Labour.

A major weakness of Korea’s employment insurance is its low effective coverage. Like in the majority of OECD countries, unemployment benefits are insurance-based and aimed to limit net income loss in the case of unemployment (Box 2.2). This risk-sharing function is particularly important in Korea due to relatively frequent unemployment and high incidence of precarious employment, notably in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, self-employed have so far been exempt from compulsory employment insurance, and only 74% of non-regular employees were enrolled in 2020 compared to the over 90% share for regular employees, despite subsidised contributions for low-income workers (MOEL, 2021). Overall, only around half of the work force has access to an employment insurance benefit in the case of unemployment. Low employment insurance coverage, combined with frequent unemployment, makes matching people with jobs harder because uninsured jobseekers are compelled to accept any available job as quickly as possible, and thereby contributes to perpetuate poor quality jobs and labour market duality. The low effective coverage of employment insurance has negative spill-overs on gender gaps, as maternal and parental leave entitlements are based on employment insurance membership (see Chapter 1).

The most important social insurance schemes for the working-age population protect households against the loss of income due to job loss, sickness and disability. Unemployment benefits and related out-of-work support measures are in place for a number of interrelated objectives: to redistribute income and pool risks between different groups of workers, to maintain acceptable living standards during times of joblessness (“consumption smoothing”) and to facilitate efficient job allocation and reallocation by improving matching. From a macro-economic perspective, unemployment support also has a central role as an automatic stabiliser.

The market fails to provide efficient insurance against these adverse outcomes because people at high risk will sign up voluntarily, while people with low risk will not, and this drives up insurance premiums to a point where insurance does not pool risk according to its purpose (a phenomenon known as adverse selection). This is why the state obliges or otherwise encourages individuals to take out such insurance.

Social insurance schemes are often self-financed by social contributions paid by participants or their employers. This leads to trade-offs between work incentives (the “tax” wedge introduced by the social insurance contributions), adequacy (coverage and replacement rate), and sustainability (how well revenues match spending over the long term).

Source: Fall et al. (2014); Immervoll (2012); OECD, 2019a.

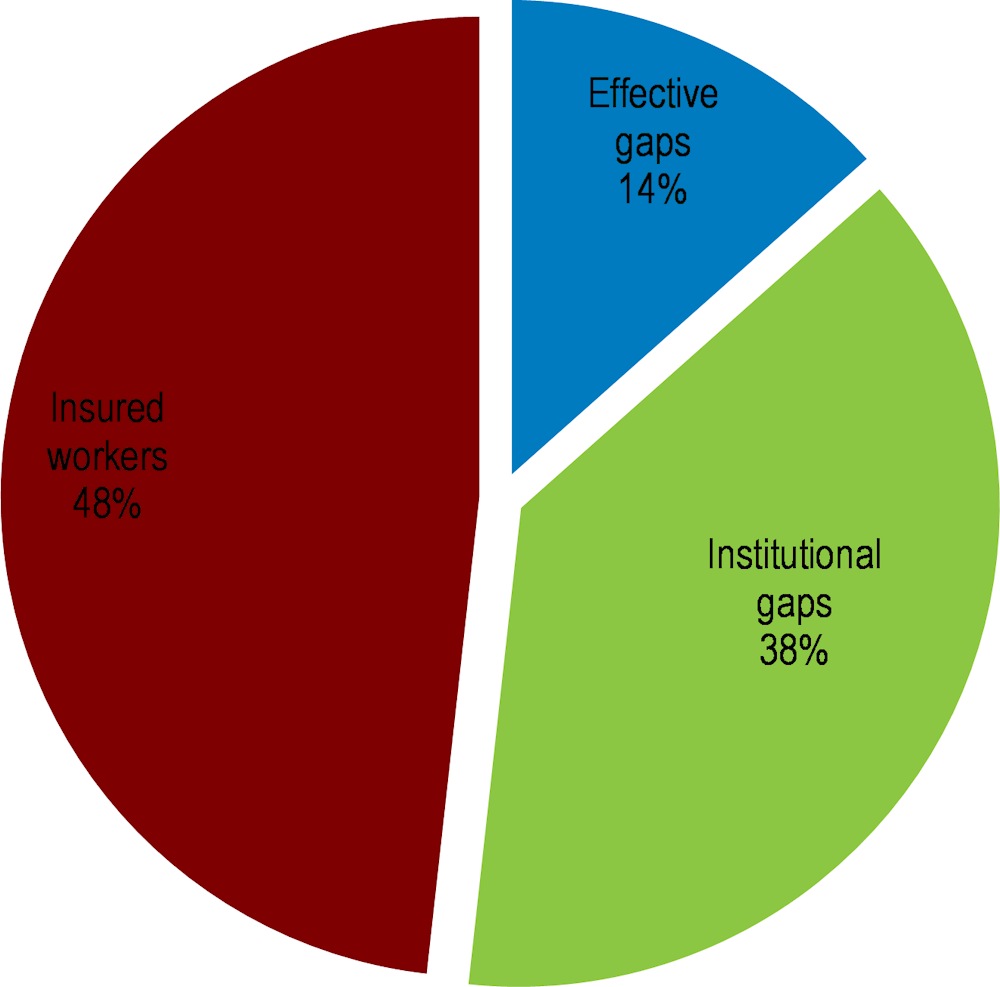

One main reason for the low coverage is that insurance programmes were not compulsory for non-wage or non-salaried workers, such as self-employed and platform workers, leading to a 38% “institutional gap” in coverage. A second main reason is that a sizeable share of employees do not contribute, despite their legal obligation to do so, leading to an additional 14% “effective gap” (Figure 2.2). Most un-covered workers are either self-employed or non-regular workers, including part-time and daily wage workers, most of whom are legally obliged to have employment insurance. The self-employed have been allowed to opt in voluntarily since 2006 but only 0.6% were insured in 2021 (as noted above).

According to the Roadmap for a Universal Employment Insurance, the government plans to expand the employment insurance coverage to all working people by 2025. As a part of this plan, workers hired under special contracts such as platform workers and after-school instructors were included in 2021-22. Discussion is underway to also expand the coverage for the self-employed. This is welcome, as self-employed are more exposed to unemployment risks than employees, and the voluntary system in place since 2006 has been unsuccessful in increasing coverage. Several OECD countries have mandatory unemployment insurance registration for self-employed workers, including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Greece (OECD, 2018a). Currently, the contribution rate for self-employed persons is equivalent to the employee’s and employer’s contribution rates combined, as in Iceland and Slovenia, and a part of the insurance premiums are subsidised for those with low-income or one-person businesses. Other countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Greece collect small-value contributions for the self-employed, for instance by reducing reference earnings or applying lower contribution rates.

Employment insurance status, % of total number of employed, 2019

Note: Institutional gaps include workers who are legally excluded from compulsory insurance programmes. Effective gaps include workers who do not contribute despite their legal obligation to do so.

Source: OECD calculations based on E. Jung (2020) and H. Jung (2020).

The government’s efforts to extend legal coverage should be accompanied by more effective enforcement measures. Employers are rarely sanctioned for not registering their workers in the Employment Insurance (EI) system. The government has used the Duru Nuri insurance subsidy to increase compliance for those with limited means, which has increased participation somewhat but at a high cost (OECD, 2020a). In response, the government has stopped paying premiums for existing subscribers from 2021 and only supports new subscribers. To strengthen compliance measures, the government increased the maximum fine for evading contributions from KRW 10 million (USD 7 900) to KRW 30 million in 2020. The higher maximum fine is a step in the right direction, but will not be effective unless the fines are actually applied.

A stronger system to monitor employment insurance registration would help increase compliance (OECD, 2018a). In 2011, the collection of social contributions was centralised under the National Health Insurance, which was an important step forward. However, this has not expanded the coverage as expected (Kim and Baek, 2020). Integrating social contributions and tax collection should be considered. Experiences in other countries suggest that this helps identify self-employed income and tackle evasion and under-reporting (Box 2.3). Integrating revenue functions is a multi-stage process that requires careful timelines and sequencing. Complementary and intermediate steps should also be considered, including mandating employers to report any change in working hours/working arrangements through an electronic system, like in Greece or Latvia, introducing an artificial intelligence-based fraud detection system, like in Canada, and/or allowing the tax administration to require platforms to provide information about any individual who has earned more than a certain amount via a platform, like in France (Mineva and Stefanov, 2018; and OECD, 2021a). The future of the Duru Nuri subsidies should also be considered after assessing the effect of the reform, given that the costly programme has not been effective in reaching its objectives.

A number of European countries, including the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, have integrated social contributions and tax collection.

An integrated revenue administration allows social security institutions and tax agencies to focus on their core competencies and often results in clear efficiency gains at a low short-term cost. Social security agencies continue to determine entitlements, manage assets and handle disbursements, whereas the tax agency collects revenues, scrutinizes declarations and identifies non-filers. Unified revenue collection thus eliminates duplication of tasks, thereby reducing administrative costs in the agencies as well as the compliance burden for employers and contributors. Simplified and rationalized revenue collection also reduces tax evasion, corruption and fraud. The main risk to integration is failing inter-agency cooperation and unclear division of responsibilities.

Evaluating the integration processes that were undertaken in many Eastern European countries in the 1990s, Barrand et al. (2004) and the World Bank (2008) identified the following success factors:

- The tax administration currently in place must have the capacity to take on the new responsibility for social contributions collection. In particular, the tax agency needs to be clearly structured and have an effective central revenue function, well-trained staff and competent management. Ideally, both tax and social insurance agencies are up-to-date and effective, so that agencies can focus on integrating and improving collection functions.

- The integration can only succeed if all parties involved endorse the merger. Stakeholders include not only social security and tax institutions but also labour unions, organized business and political parties.

- Integrating revenue functions is a multi-stage process that requires strong project management with careful timelines and sequencing. Given the complicated operational and legislative process in play, the full implication/implementation is likely to take at least two years. Transferring functions in small phases and in one single step have both yielded good outcomes.

- The tax agency should be financially compensated for its expanded responsibilities. In some countries, the social insurance agency has directly remunerated the tax agency for the costs of collection.

Source: International Monetary Fund (2004) and World Bank (2008).

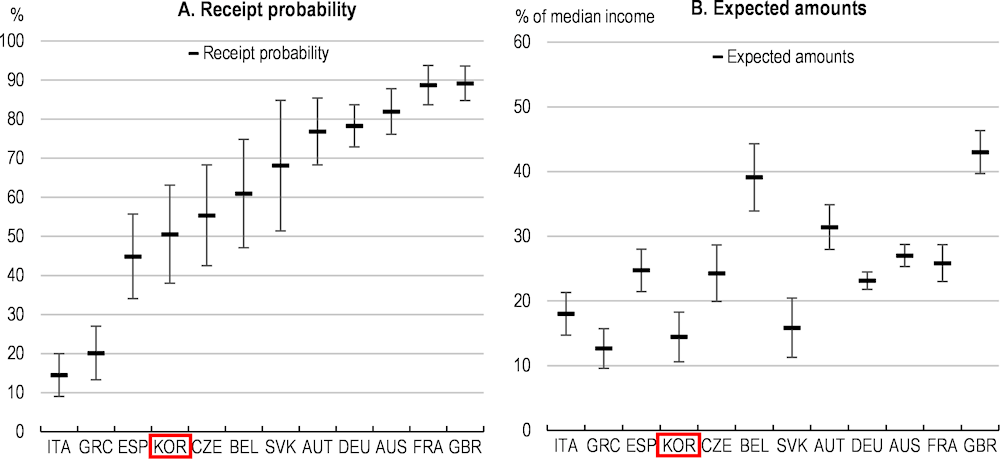

Non-contributory benefits are provided as a last-resort social safety net, but many poor working-age Koreans are not properly protected by the Basic Livelihood Security Programme (BLSP) and the National Employment Support Programme (NESP). OECD estimates based on household data across 12 OECD countries show that workless low-income households in Korea were the fourth least likely to receive non-contributory benefits (Figure 2.3, Panel A). Average benefit levels for those receiving support were the second lowest, with expected benefit levels below 15% of median household income (Panel B).

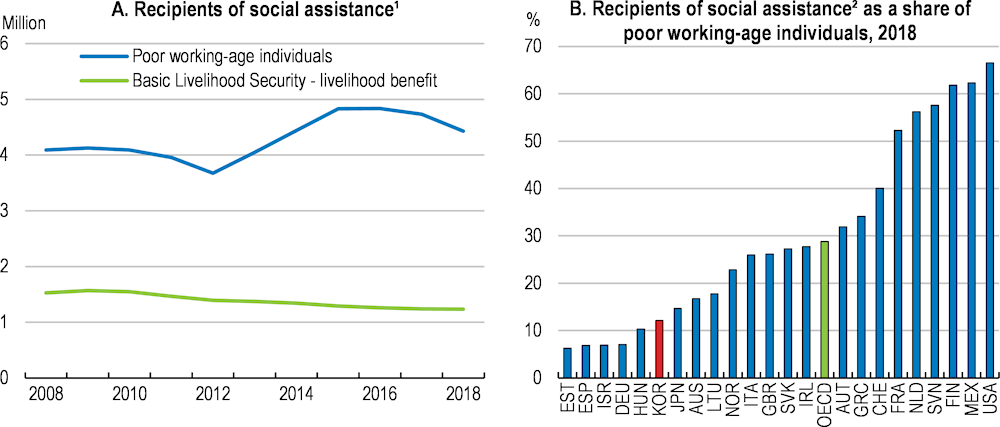

Coverage of BLSP social assistance remains relatively low (Figure 2.4), despite the important steps taken to expand eligibility. In 2015, the “all or nothing” nature of previous BLSP benefits was replaced by different income thresholds for livelihood, health, housing and education benefits (Box 2.1), reducing poverty risk. Over 2017-21, the family support obligation was gradually abolished for livelihood benefits, education benefits, and housing benefits (under this rule, many applicants could not receive benefits if they had a close family member capable of supporting them). This reform is expected to have increased the number of BLSP recipients by around 200 000 mainly older people, and the share of BLSP beneficiaries in the total population by 1.4 percentage points to 4.5% in 2021. The income criterion for the BLSP livelihood benefits (30% of median income) is still below the thresholds of 50% or 60% of median income that is commonly used to define relative poverty. The government plans to increase the income criterion to 35% for livelihood benefits, and 50% for housing benefits. Further extending the BLSP would significantly strengthen the safety net.

Note: Data refers to 2019 for Korea, and 2015 for other countries. Bars indicate 90% confidence intervals. Expected non-contributory benefit receipt for individuals living alone in the bottom 20% of the distribution of income from market sources and contributory benefits. In Korea and the United Kingdom, benefits include refundable means-tested tax credits.

Source: Hyee et al. (2020).

1. Poor population refers to individuals living in households whose equivalised disposable income is below 50% of the median disposable income of the country.

1. Most of these benefits are awarded at household level. Recipient numbers count the number of benefits paid (and not the number of people who directly or indirectly benefit from them). USA includes food stamps, GBR includes Universal Credit (In employment) which replaced Income support in 2013, DEU includes only Sozialhilfe and not the SGBII benefit which is considered as an unemployment benefit in OECD-SOCR.

Source: OECD-SOCR database; and OECD, Benefits, taxes and wages (database).

The BLSP has increased over the past few years, but the benefit level remains low by OECD standards. Estimates based on the OECD tax-and-benefit model show that a single person eligible for the living and housing benefits would receive about 32% of the median household income in Korea, four percentage points lower than the OECD average (Figure 2.5). Further increases should be considered, with due consideration of impacts on poverty among vulnerable groups and the fiscal cost.

Some additional policy interventions to improve take-up rates can also be considered. According to a survey of people who did not take up BLSP despite being eligible, 12% of respondents said it was because they were unaware of the system and 10% because of the complexity of the application process (Kim, 2020). These are also among the most common reasons invoked by people who do not claim benefits for which they are entitled in EU countries (Ko and Moffitt, 2022). Simplifying administrative procedures and raising awareness of the scheme would help address this issue (Hernanz, Malherbet and Pellizzari, 2004). For example, mailing recipients saying that they are eligible and explaining the scheme substantially increases take-up rates, particularly among those living in rural areas in Korea (Kim, 2020). If privacy issues arise, mass mailings of letters or media campaigns can also be considered. For example, Dickert-Conlin et al. (2021) found that in the United States, state-level outreach and media campaigns increased participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. However, such efforts would necessarily be more costly than mailing to eligible households only (Ko and Moffitt, 2022).

Social assistance, share of median disposable income, 2021

Note: 2020 for Australia, Canada, Israel, Korea, New Zealand and Switzerland.

Source: OECD, Benefits, taxes and wages (database).

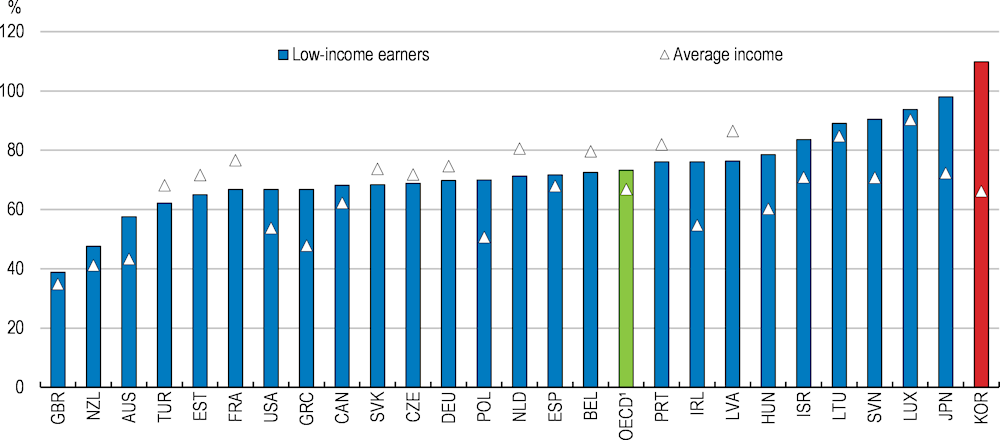

The National Employment Support Programme (NESP) (previously called Employment Success Package Programme) helps jobseekers and unemployed neither entitled to EI nor receiving BLSP but facing considerable disadvantages, especially in the form of low income. The assistance combines means-tested income support and targeted employment services (Box 2.1). Thanks to strong activation measures, participants’ employment rate hovered around 60% between 2016 and 2019, and about half had worked for more than a year (Figure 2.6, Panel A). In view of these positive employment outcomes, the threshold for the asset test associated with this allowance was raised from KRW 300 million to KRW 400 million in 2021, and young people were allowed to receive employment support regardless of their employment history. As a result, the number of participants nearly doubled (Panel B). Despite this strengthening, monthly income support is still only 14% of the average wage. This is relatively low compared with other OECD countries and less than one third of the lower limit on Employment Insurance benefits. This is the largest gap in the OECD (OECD, 2018a).

The rapid expansion of beneficiaries and resources should be accompanied by improved quality assurance. The government has taken some steps to cope with the growing caseload per counsellor. In 2021, special private providers dedicated to offering targeted employment support services to young people (23 offices) were introduced and the number of counsellors (+740) and employment centres (+32) were increased. As of 2021, half of the total number of clients received employment support services from private providers according to the Ministry of Employment and Labour. In a purchaser-provider model it is essential to ensure that only effective private providers delivering the highest-quality services can continue to operate. To monitor their performance, a stronger quality assurance framework could be implemented, for instance following the example of Australia's “Star Rating” assessment system (OECD, 2012).

Employment and work intensity are key determinants of poverty. Social assistance and unemployment benefits therefore need to encourage beneficiaries to take up or return to work. There is however a tension between work incentives, income protection and the affordability of the benefit system.

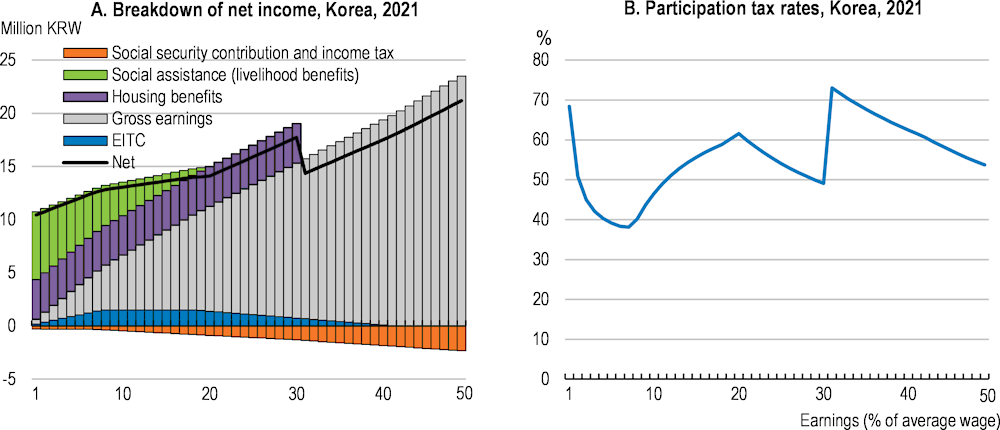

According to the OECD TaxBen model, the incentives to take up low-wage full-time employment are relatively low for jobless households receiving the BLSP. Participation tax rates, which measure the proportion of earnings taken up by taxes, social contributions, and benefit withdrawal when an individual takes up employment, were above the OECD average in 2020. For example, one adult in a jobless couple without children taking up a full-time job at the minimum wage would lose 54% in taxes, social contributions and lost benefits, 5 percentage points higher than the OECD average.

The relatively high participation tax rates are driven mainly by the rapid withdrawal of BLSP social assistance, together with a narrow targeting of the Earned Income Tax Credit (see below). BLSP recipients with earned income have their livelihood benefits withdrawn at higher rates as earnings increase and housing benefits disappear from a certain level (Figure 2.7, Panel A). In particular, the cliff-edge withdrawal of housing benefits leads to a participation tax rate of above 70% (Panel B). This provides weak financial incentives to take up low-paid employment despite the Earned Income Tax Credit. Indeed, only 16% of BLSP recipients assessed to be able to work participated in the Self-Sufficiency Programme, designed to help BLSP recipients to find jobs, and only 34% of the programme participants took up work in 2020 (Seo, 2021). A more gradual tapering of the BLSP will improve work incentives. It will also extend BLSP entitlements to a greater number of people with limited earnings, providing a type of in-work support and reducing their poverty risks.

Note: Participation tax rates refer to the fraction of income that is taxed away by the combined effect of taxes and benefit withdrawals when entering or returning to work. Calculations based on a single childless person.

Source: OECD TaxBen model. http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

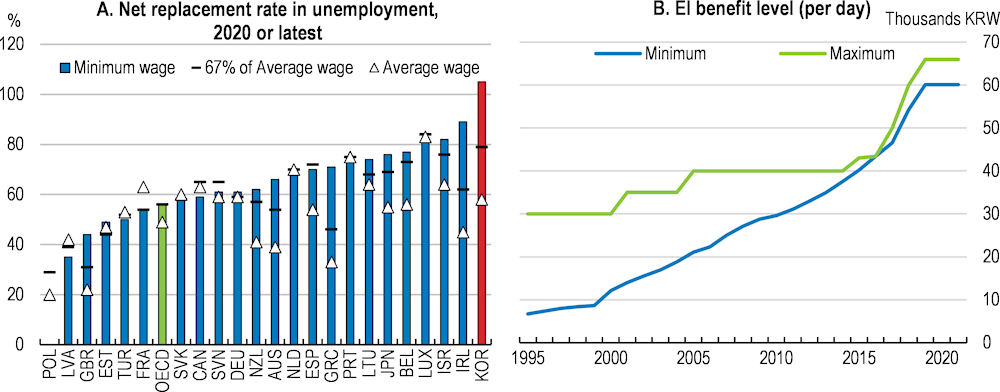

Employment insurance also blunts incentives to return to work for low-wage workers in particular. The participation tax rate for EI beneficiaries returning to work at the national average wage is 65%, which is comparable to the OECD average. However, EI beneficiaries returning to a minimum wage job face a participation tax rate of 110% (Figure 2.8). This means they lose KRW 1 for every KRW 10 earned by working due to the benefit withdrawal and taxation of in-work income while the unemployment insurance is not taxed. This is unique among OECD countries and can potentially trap EI recipients in unemployment, especially given that employment insurance eligibility was recently expanded to new groups of non-regular workers with lower average incomes. Disincentives are to an extent held at bay by the nine-month maximum benefit duration.

Participation tax rates, 2021

1. Unweighted average for the countries included in the figure.

Note: Participation tax rates refer to the fraction of income which is deducted by the combined effect of taxes and benefit withdrawals when entering or returning to work. Calculations based on a single, childless person, working full-time before unemployment. Low-income refers to minimum wage.

Source: OECD TaxBen model. http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

The weak work incentives reflect a high minimum benefit level (Figure 2.9, Panel A). The benefit floor has increased rapidly since the introduction of employment insurance, while the maximum EI payment has increased more slowly (Panel B). This is because the benefit floor is linked to 80% of the minimum wage, which has increased rapidly, while the maximum EI payment is determined by the government. As a result, unemployment benefits are effectively flat-rate, unlike in any other OECD country (OECD, 2018a). The ceiling is close to the OECD average, and broadly equivalent to ceilings in Sweden and Denmark (OECD, 2018a), whereas the high floor makes Korea the only country in the OECD where all unemployment benefit recipients gain more than their net minimum wage (Figure 2.9, Panel A). Reducing the EI floor to the OECD average level should be considered, for instance by capping it at a lower share of the minimum wage, while moderately increasing the maximum duration of the unemployment benefits which is relatively short by international standards (Immervoll et al., 2022 forthcoming). At the same time, a moderate increase in the ceiling can also be considered to enhance the insurance function of the system (Box 2.2).

Note: Panel A shows Net Replacement Rates (NRR) for a jobseeker after six months of unemployment. The net replacement rate measures the fraction of net income in work that is maintained when unemployed. It is defined as the ratio of net income while out of work divided by net income while in work.

Source: OECD Tax and Benefit Models; Ministry of Labour; and OECD calculations.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), introduced in 2008, aims to address in-work poverty and better support the large number of people who are unable to earn a decent living despite being employed. In 2019, the share of the working poor (defined as those earning less than 60% of the median income) among all workers was 19.4%, most of whom are non-regular workers (KIHASA, 2020). The government has continuously expanded the scope and coverage of the EITC. In 2012, the EITC was extended to childless households and some self-employed workers. In 2015, BLSP recipients were allowed to receive EITC. In 2019, the EITC was extended to workers under 30 without a spouse and/or dependent child, leading to a significant increase in the number of younger recipients (Chapter 3). In 2019, the maximum EITC benefit was raised, with increases ranging from KRW 500 000 to KRW 3 million for two-earner households and from KRW 650 000 to KRW 1.5 million for single-person households. In 2020-21, the income threshold for eligible households was raised. As a result, both the number of beneficiaries and total pay-out tripled between 2017 and 2020, with one in four households currently receiving EITC.

The impact of an EITC in terms of increasing labour supply and reducing unemployment is generally greater in countries with a wide earnings distribution, low tax rates on labour, and low benefits for the non-employed, indicating that it could be an effective instrument in Korea (OECD, 2013). Empirical analysis also suggests that EITC has some positive impact on employment and working hours, especially among those who do not receive BLSP (Park et al., 2021; Eom et al., 2014; Nam, 2017).

The new government is considering expanding the EITC further by raising the maximum benefit amount and the income threshold. Phasing out the EITC higher up the earnings scale and more slowly could be considered, as it would improve work incentives and reduce inequality and poverty, but would come at a fiscal cost. For example, EITC for a single person in Korea is fully phased out at around 40% of the average wage, compared to around 50% of the average wage in France, and well above the average wage in New Zealand (OECD, 2021b).

The poverty rate for those aged 65 and over is high in Korea. Rapid ageing is projected to transform Korea into one of the most aged societies in the OECD, with more than 20% of the population being seniors in 2050 (Chapter 1). The fact that people are living longer is an accomplishment in itself, but ageing also puts long-term fiscal sustainability at risk (Figure 2.10).

Note: Panel A: Social expenditure comprises cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes. To be considered "social", programmes have to involve either redistribution of resources across households or compulsory participation. Social benefits are classified as public when general government (that is central, state, and local governments, including social security funds) controls the relevant financial flows. Data from 2017 for Japan and Australia and from 2018 for Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, New Zealand and Switzerland.

Source: OECD (2022), Social spending (indicator), doi: 10.1787/7497563b-en; Guillemette and Turner (2021).

The Korean public pension system consists of four main components. The tax-based (Pillar 0) Basic Pension provides a KRW 300 000 maximum benefit (2021) to people aged 65+ below an income threshold. The (Pillar 1) National Pension Service (NPS) is a partially funded system with contributions from workers and employees. The pension benefit consists of two parts that are equally weighted: i) benefits based on individual earnings; and ii) benefits based on average earnings of the insured as a whole. The (Pillar 2) private corporate pension scheme gives employers the choice to convert the mandatory lump-sum severance payment (also called the retirement allowance), which requires employers to pay one month of wages for each year of employment to departing employees, to a tax-advantaged defined benefit or defined contribution pension plan with the consent of employees. This scheme introduced a portable individual retirement account (IRA) for workers who change jobs. The (Pillar 3) personal pension is a supplementary private pension scheme. The system as a whole fails to secure adequate pension income for many seniors, as the Basic Pension is low, beneficiaries of the NPS generally receive a low level of benefits (partly reflecting a short contributory period), both workers and employers prefer severance payments over pension annuities, and participation in the supplementary personal pension scheme is low. Against this background, the new government plans to reform the pension system, but details are not yet available.

An immediate priority to tackle elderly poverty in the short term is strengthening the Basic Pension. Together with the Basic Livelihood Security Programme discussed in the previous section, the Basic Pension is the main social welfare programme supporting today’s elderly. It is a tax-financed means-tested benefit for the elderly aged over 65.

Even though the Basic Pension is means-tested, a high income threshold means that around 70% of the elderly receive it. At the same time, the benefit level is among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.11) at 8% of gross average earnings. The new government plans to increase the Basic Pension level from KRW 300 000 to KRW 400 000. But this is still relatively low compared to the OECD average and insufficient to address high old-age poverty. Even doubling the current amount for low-income seniors would only reduce the old-age poverty rate by 11 percentage points to 33%, which is still high in OECD comparison (Lim, 2018).

Non-contributory first-tier benefits, share of gross average earnings, 2020

Most OECD countries means-test their non-contributory pensions, while some provide a minimum pension based on residency. There is a trade-off between targeting, pension level and fiscal cost, where at a given fiscal cost a more targeted Basic Pension is more effective in fighting poverty. At the same time, the total number of recipients will increase significantly with rapid population ageing and undermine affordability under current rules. The original objective of the basic old-age pension, introduced in 2008, was to provide partial support to the elderly who have not secured the national pension entitlement or paid contributions for a sufficient period, but more and more pensioners will have been able to build their own pension entitlements and sufficient contributory periods in a gradually maturing pension system (Jones and Urasawa, 2014). The share of the elderly who received the national pension has already increased by around 12 percentage points over the past six years, from 36% in 2015 to 48% in 2021. Better targeting, as recommended in previous surveys (e.g. the 2014 and 2020 OECD Economic Surveys of Korea), would leave room to increase the benefit level for the low-income elderly while maintaining an affordable system for the taxpayer. The government will set up a committee to review the pension system. In the context of this review and conditional on how a potential reform of the National Pension System addresses issues of old-age poverty, lowering the Basic Pension income threshold and increasing the benefit level to better target those with the highest needs should be considered.

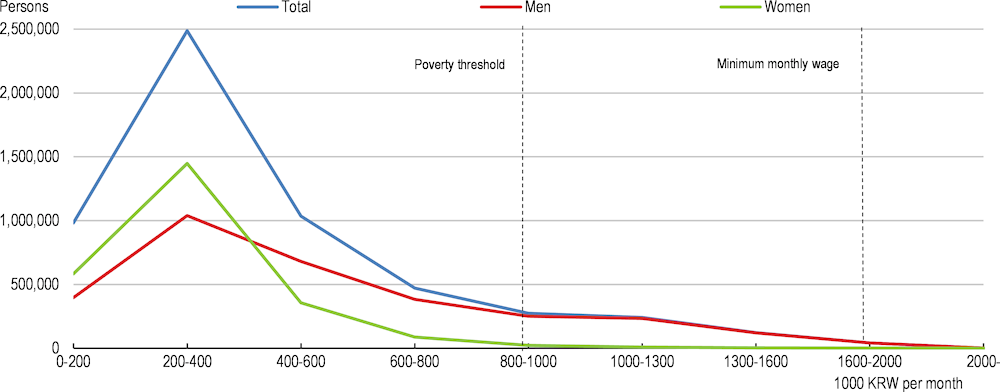

A second priority is to improve the contribution-based defined-benefit National Pension Service (NPS). The NPS faces a double challenge. One is raising low pensions. Currently, most national pensions are below the poverty line (Figure 2.12). The average amount in 2021 was only KRW 550 000, one-third of the minimum wage. This reflects the short contributory period (18.6 years on average for new pensioners in 2020) and relatively low replacement rates. Another is improving pension sustainability. Due to rapid population ageing, pension expenditure is set to more than triple by 2050 and the National Pension Fund (NPF) would be depleted by 2057 under the existing set-up (NPS, 2018). These two challenges are two sides of the same coin. Higher pensions may jeopardise sustainability, and if a pension system is unsustainable, sudden corrections in pension levels can be needed in the future (Reinhard, 2010). A balanced approach is therefore required.

Distribution of pensioners by pension amounts, 2021

Note: Pensions refer to all types of old-age pensions from the National Pension Service including full old-age pension (완전 노령 연금), early old-age pension (조기노령연금), reduced old-age pension (감액노령연금), and special old-age pension (특례 노령연금).

Source: National Pension Service; and OECD (2021d).

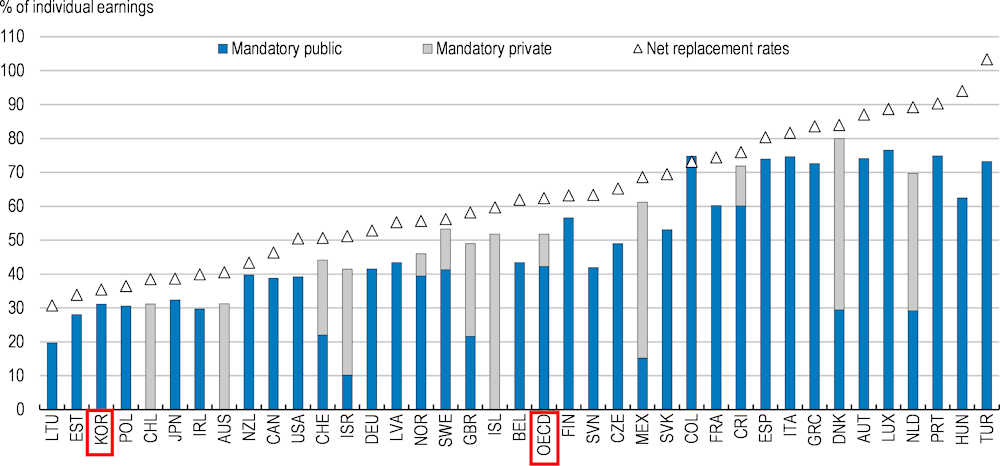

Overall, the gross replacement rate of a full-career worker with an average wage is 31%, 11 percentage points lower than the OECD average (Figure 2.13). According to national estimates, the gross replacement rates are nine percentage points higher (Box 2.4), but this is still low in international comparison. The net replacement rate, better reflecting disposable income in retirement, is 35%, reflecting that pension benefits are exempt from social security contributions in Korea, against a 62% OECD average. The low replacement rate contributes to the fact that only around 60% of the population aged 18-59 paid into to the NPS in 2020 despite the legal obligation for all workers to do so. Nearly half of those surveyed in 2012 expected that the NPS pension benefit would be insufficient to cover their basic living expenses in old age (Seok, 2021). With the targeted replacement rate falling from 70% to 40% in 30 years, trust in the NPS has faltered. A moderate increase in the replacement rate, together with more efficient collection of social contributions would help increase the coverage and reduce elderly poverty in the long run, as previous surveys recommended (e.g. the 2016 and 2020 OECD Economic Surveys of Korea).

Gross pension replacement rates from mandatory public and private pension schemes and total net replacement rate for entry into working life in 2020 at age 22

Note: Theoretical replacement rates for a full career worker.

Source: Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Assuming a full career with average earnings, the National Pension Service (NPS) estimates a replacement rate of 40% while the OECD estimates a 31% replacement rate. Similar differences exist in replacement rate calculations with different earnings and career assumptions, reflecting:

Different assumptions about average earnings: the OECD only considers the average earnings of regular workers, while the NPS considers the average earnings of all contributors, including the self-employed. Average earnings estimated by the NPS in 2020 were KRW 2.4 million, 37% lower than estimated by the OECD.

Different assumptions about the contribution period: the NPS assumes that a person contributes 40 years from age 18 until age 59, after which no entitlements are earned. 40 years is the maximum contribution period in Korea. In comparison, the OECD assumes that a person contributes 38 years from age 22 to 59.

Raising the pensionable age and preventing firms from forcing retirement before that age (so-called honorary retirement) can lengthen working lives and improve both adequacy and sustainability (Ebbinghuas, 2012) by reducing the number of retirees and boosting pension contributions and entitlements. Extending working lives in the face of ageing is also crucial to alleviate negative effects on growth and living standards.

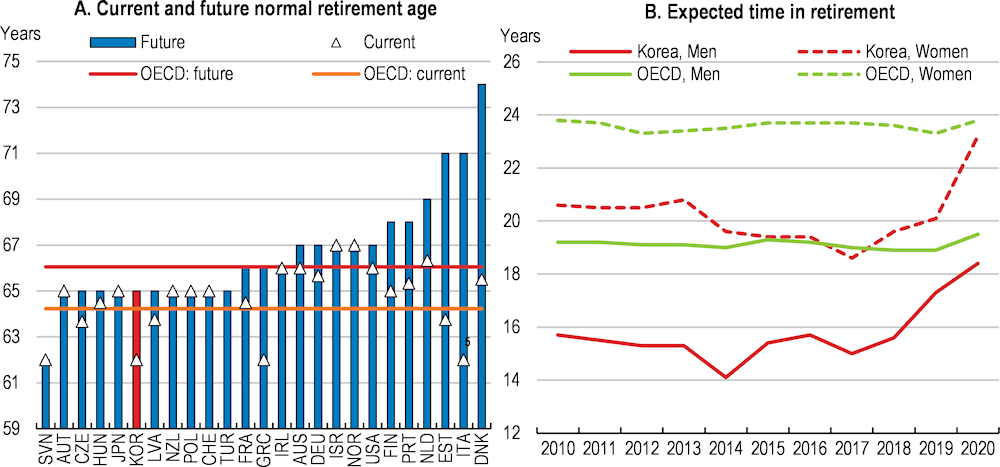

The pensionable age is currently 62, one of the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.14, Panel A). The pensionable age is set to gradually increase to 65 by 2034, but this is still low in international comparison (Panel A). The relatively slow increase of the pensionable age, combined with a rapid rise of life expectancy, leads to a sharp increase in the expected time in retirement (Panel B). However, the proportion of workers aged 55 to 64 who wish to extend their working lives has continued to grow, and their desired retirement age was 70.4 on average in 2019 (Kim, 2020). A number of OECD countries link the normal retirement age (the age at which employees are eligible to start receiving full retirement benefits) to life expectancy. In Finland and Portugal, the normal retirement age increases by two-thirds of the gains in life expectancy, while the relation is one to one in Denmark and Italy. In the case of Korea, applying two-thirds of the gains in life expectancy between 2022 and 2065 from the National Pension eligibility age of 65 in 2034 would give a normal retirement age of 67 for those retiring in 2065, around the OECD average (OECD, 2022 forthcoming). The automatic link of life expectancy and pensionable age would reconcile pension sustainability and adequacy in the context of population ageing. Consideration should also be given to accelerating the gradual shift to 65. Increasing the pensionable age should be accompanied by abolishing the gap between contribution age and pensionable age. Contributions currently stop at age 60, two years before pensionable age. This gap is unique in the OECD, and should be eliminated (OECD, 2022 forthcoming). Without reform, those entering employment at age 22 will continue to only make 38 years of contributions, despite the pensionable age increasing to 65 by 2034.

Note: For Panel A, current and future normal retirement ages for a man with a full career from age 22. Current and future refer to retiring 2020 and entering the labour market in 2020, respectively. Normal retirement age refers to the age at which employees are eligible to start receiving full retirement benefits.

Source: OECD (2021d), Pension at a glance; and OECD Social Protection and Well-being database.

Linking the pensionable age to life expectancy would not reinforce inequalities in Korea. Even though differences in life expectancy are persistent, gains in life expectancy have been broadly similar between different socio-economic groups over the past 15 years, as have gains in life expectancy in good health (Statistics Korea, 2019; and Yoon, 2022). The persistent inequalities in life expectancy should be addressed by health policies rather than the pension system (see below).

Many workers exit their career jobs around the age of 50 due to the practice of honorary retirements. Pension contributions over their second careers are often limited. Limiting the power of firms to force early retirement is essential to translate increases in the statutory retirement age into a higher effective retirement age. According to Statistics Korea, in 2021, around two thirds of those aged 55 to 64 left their career job before reaching pensionable age. Those who had retired were on average 49.3 years at the time of retirement, and the average length of tenure was only 12.8 years. 41% of the retirement in 2021 was involuntary (Park, 2022). Wage-setting is predominantly seniority-based in Korea (OECD, 2019b). Workers and trade unions support the system, as it provides workers with a guarantee that they will receive a relatively high income when they need to pay for their children's education (OECD, 2018b). This is a root cause of early retirement, as it creates a gap between wage and productivity, accentuated by a large generational gap in education and skills (OECD, 2020a). This creates a culture of forced early retirement either through “mandatory retirement”, by which firms lay off older workers below the statutory retirement age, or “honorary retirement”, by which firms encourage their older employees to voluntarily leave their job before reaching the mandatory retirement age against considerable compensation. The early retirement from career jobs, together with weak social protection, not only leads to a short contributory period but also creates the precarious employment situation of many older workers. It also encourages workers to take lump-sum severance pay which is often needed to create a small business, instead of pensions which are only available after the statutory retirement age.

Some measures have been taken to restrict forced early retirement, but problems remain. Subsidies for the wage peak system which freezes or gradually reduces the wages of older workers have been used since its introduction in 2006 to encourage employers to retain older workers. This has helped employers coping with the wage peak system, but only half of the large firms with more than 300 employees had introduced the scheme as of 2020, reflecting opposition from workers. Also, a law took effect in 2017 to prevent employers from setting mandatory retirement at ages lower than 60. Under this law, employers cannot force employees under the age of 60 to retire. This is significant progress, but will increase the gap between workers’ wage and labour productivity further in the current environment (OECD, 2018b). This increases firms’ incentives to encourage honorary retirement, and empirical analysis suggests that the 2016 reform increased the odds of early retirement through honorary retirement (Lee and Cho, 2022).

The ultimate objective should be a flexible wage system based on performance, job content and skills requirements as recommended by the 2020 OECD Economic Survey of Korea and recognised in the new government’s economic policy directions (MOEF, 2022). Introducing worker appraisal and wage-setting mechanisms that are less rigidly tied to individuals’ seniority and more weighted towards their actual skills, competencies and the demands of the particular role they fill, would benefit all economic stakeholders alike and help older workers retain their main jobs until effective retirement. It would also align Korea more closely with the norms in other OECD countries. Among the 10 largest corporations in Korea, LG Innotek was first to introduce the flexible wage system fully based on performance in 2016, after discussion and negotiation between unions over more than two years. To enhance the fairness of performance evaluation, a special committee was also formed in which employees and the employer participate together. Other large companies such as Hynix and Samsung have also been negotiating with their unions, but have not yet reached an agreement. To challenge the status quo, the government should also, in cooperation with social partners, promote mutually beneficial frameworks to align wages with job requirements and skills.

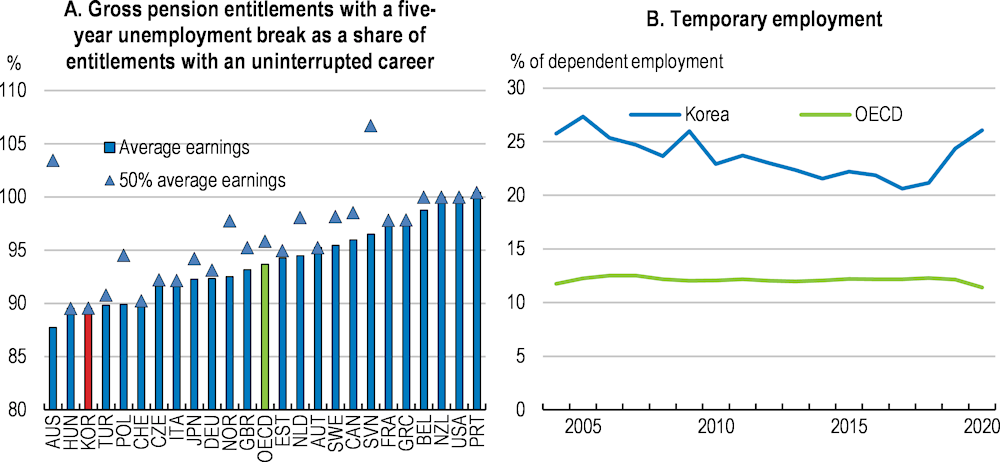

Limiting the loss of pension rights from career breaks would further reduce poverty risks. Compared with other OECD countries, unemployment spells lead to large pension losses in Korea (Figure 2.15, Panel A). Workers earning an average wage lose ten percentage points of their pension replacement rate following a five-year unemployment spell. This is because pension entitlements accrue based on the employment insurance (EI) benefit for a maximum of one year. This compounds the inequalities associated with a polarised labour market that features a high and increasing share of temporary workers who face more career interruptions (Panel B). Crediting longer periods of unemployment would reduce the risk of people with interrupted careers falling into poverty at old age (OECD, 2022 forthcoming).

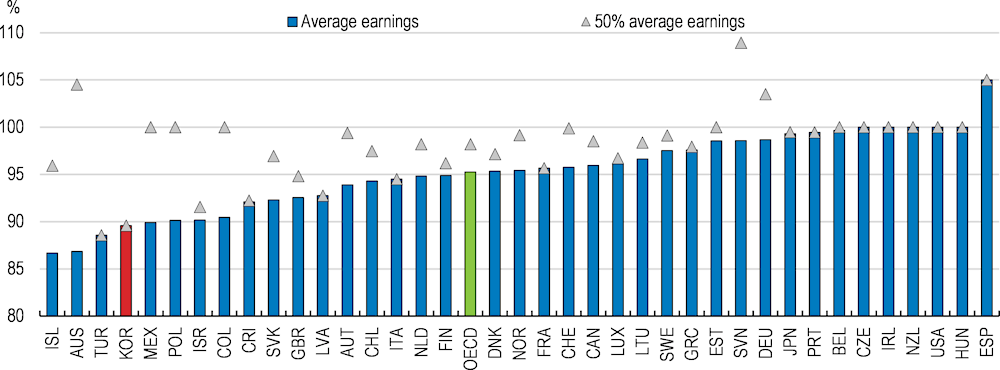

Childcare breaks also lead to a relatively high loss of pension entitlements (Figure 2.16). Korea is the only country in the OECD that does not provide a pension credit for the first child. A childcare pension credit is provided for a maximum of one year for the second child, and 18 months for the third and consecutive children, but with a ceiling of 50 months in total. Childcare pension credits are accumulated for at least two years per child in most OECD countries, and much longer in some countries like Germany (three years) and Sweden (four years) (OECD, 2022 forthcoming). Providing at least an 18 months pension credit for each child, including the first child, and scrapping the 50 months cap are warranted to reduce the risk that people with childcare duties fall into poverty in old age, and would be in line with the objective to support fertility. This is particularly important in Korea where the gender gap in old-age poverty is the second highest in the OECD at 4.4 percentage points (OECD, 2019b). According to national estimates, one additional year of childcare credit would increase monthly pensions by KRW 26 000 (Yoo and Kim, 2020), which is still low. Credits lasting at least two years per child would ensure that mothers’ pensions are not penalised (OECD, 2022 forthcoming).

Note: For Panel A, individuals are assumed to embark on their careers as full-time employees at 22, and to stop working during a break of up to five years from age 35 due to unemployment; they are then assumed to resume full-time work until normal retirement age. Low earners in Colombia, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia are at 66%, 60%, 53% and 55% of average earnings, respectively, to account for the minimum wage level.

Source: OECD (2021d), Pensions at a glance; and OECD employment database.

Gross pension entitlements with a 5-year childcare break, as a share of entitlements with an uninterrupted career

Note: Individuals enter the labour market at age 22 in 2020. Two children are born in 2028 and 2030 with the career break starting in 2028. Low earners in Colombia, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia are at 66%, 60%, 53% and 55% of average earnings, respectively, to account for the minimum wage level.

Source: OECD (2021d) Pensions at a Glance.

The contribution rate to the National Pension Service (NPS) is, at 9%, half of the OECD average and among the lowest in the OECD. Under the existing setup, the contribution rate would need to more than double to finance the current target replacement rate of 40% over the long term (National Pension Actuarial Projection Committee, 2018). The labour tax wedge is low at 23%, compared to an OECD average of 35%, suggesting room to increase contributions. In 2018, the government proposed to increase the contribution rate to 13% but this has been delayed several times, mainly due to resistance from current insured persons who have to pay it. Pension contributions should increase sooner rather than later, however, as delayed adjustment compounds the imbalance between pension contributions and liabilities, and will force tougher adjustments for future generations down the road (Chun, 2020).

At the same time, the government should consider more explicitly financing some redistributive components of the public pension system by general taxation. In Korea, 100% of the Basic Pension is already financed via general taxation. But around 70% of childcare pension credits and 75% of the unemployment pension credits are financed by social security contributions and there has not been any increase in contributions since those credits were introduced. Fully financing these elements via general taxation would strengthen the link between pension premiums and entitlements, and it would allow financing by taxes that are less distortive than income taxes and social security contributions. Japan, for instance, gradually raised the consumption tax by five percentage points between 2012 and 2019, mainly to finance rapidly increasing ageing-related costs including pensions. This approach can also be considered in Korea whose 10% VAT rate is well below the 19.2% OECD average (in 2020).

In addition, automatic adjustments of pension benefits to life expectancy could be introduced. This could help ensure financial sustainability, reduce the need for recurrent discretionary adjustments and improve the predictability of future pension entitlements. Several OECD countries use automatic adjustments. For example, Japan links pension entitlements to life expectancy, subject to the constraint that the replacement rate must not go below 50%. In Germany, which has a point-based pay-as-you-go system, the pension point value is linked to the ratio of contributors to pensioners; if the ratio increases, past contributions are uprated by more than average wage growth and vice versa though benefits are not allowed to fall in nominal terms.

Private pensions complement retirement income from public sources. Given the weak and immature public pension system and the ongoing demographic and fiscal pressures on public pensions, strengthening the role of quasi-mandatory occupational company and voluntary personal private pensions might be important for Korea, as recognised in the government’s economic policy directions (MOEF, 2022).

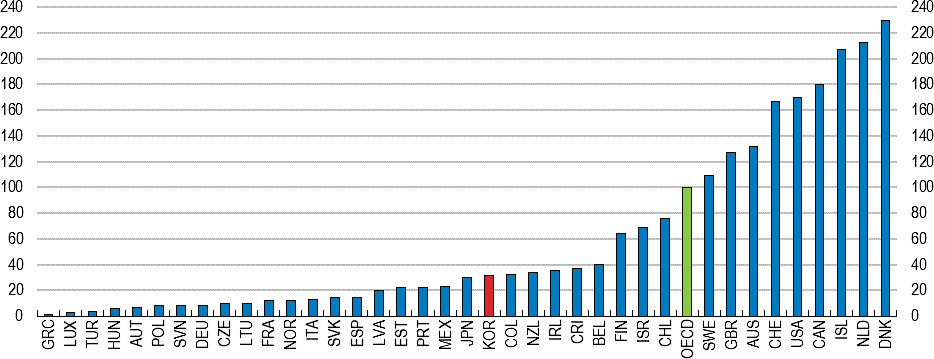

Private pension savings are low, reflecting the relatively short existence of the system, but also low participation and low yields from savings (Figure 2.17). Only 17% of the working-age population participated in occupational pension plans, one of the lowest shares in the OECD (OECD, 2021c). The participation in personal pension plans is also among the lowest of OECD countries, at around 14% of the working-age population. Participation is particularly low among low-income workers and the self-employed. According to the National Tax Service, the participation rate was only 3% for those who earned less than KRW 300 million (approximately 80% of the average wage) in 2018. Low participation partly reflects weak financial incentives. In Korea, both contributions and returns on investment are exempt from taxation while benefits are treated as taxable income upon withdrawal, as in many other OECD countries. According to OECD estimates, the overall tax advantage compared to a benchmark savings vehicle is 20% of the present value of contributions (8% for lower-income earners at 60% of average savings). This is at the lower end among those OECD countries providing tax advantages to encourage private retirement savings, and compares to a 30-50% tax advantage in Japan, the Netherlands and Israel (OECD, 2018c) (OECD, 2021d).

Total assets in retirement savings plans, % of GDP, 2020 or latest available year

Source: OECD (2021c), Pension Markets in Focus 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/pensions/pensionmarketsinfocus.htm.

Some measures should be considered to bolster participation in private pensions. One way is to introduce automatic enrolment for all workers with the possibility to opt out, an approach used in some OECD countries. In Lithuania, for instance, all workers younger than 40, irrespective of their employment status, are automatically enrolled into a pension fund by a public entity, with the possibility to opt out. Evidence suggests that automatic enrolment with the option to opt out increases participation compared to the option to opt in (Pereira and Afonso, 2020; and Beshears et al., 2013). At the same time, increasing tax advantages can encourage people to stay rather than opt out. The government plans to raise the savings limit for pension credits from the current KRW 4 million to KRW 6 million. Increasing the tax credit rate, which is currently relatively low, can also be considered. Another way is to make enrolment mandatory for the self-employed as in Sweden, Estonia, Israel, and Latvia. All employees are mandatorily enrolled in corporate pensions (see below), but the self-employed are enrolled in private pensions on a voluntary basis. Mandating self-employed to enrol in a private pension scheme, for example by means of individual retirement pension accounts, would help reduce gaps in retirement income between the self-employed and employees (OECD, 2020b).

Significant improvements in pension fund returns are also needed. Their investment strategy is very conservative, contributing to the low returns of private pensions (Figure 2.18, Panels A and B). This reflects that most subscribers choose very conservative products that guarantee the repayment of the principal and interest, even in a low-interest rate environment, presumably due to indifference and low financial literacy.

Introducing default life-cycle-based investment strategies, as planned, with substantially higher allocations to global stocks and high initial allocations to equities for young participants, lowered as the individual gets closer to retirement, can help improve performance. Reducing and regulating the choice of investment possibilities can help people make difficult investment decisions, especially if financial literacy is low. The investment limit for risky assets should also be reconsidered. Currently, investment in risky assets listed in law (e.g. debt securities and beneficiary certificates that meet requirements) is limited to a maximum of 70% of assets held in retirement pension plans. Listed equity and private equity funds are part of the eligible risky assets and therefore allowed (up to 70%) for occupational defined benefit plans, but are fully prohibited for defined contribution plans. This is relatively restrictive in international comparison. For instance, more than half of the OECD countries, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands and the United States, have no limits to investments in corporate bonds and equity (OECD, 2019c).

The retirement allowance was intended to support the unemployed and retirees in the absence of unemployment insurance and pensions. Most OECD countries do not have severance pay for retirement. Corporate pension systems allow firms to convert the mandatory severance pay into retirement schemes such as a defined benefit (DB) scheme, defined contribution (DC) scheme, or Individual Retirement Pension, subject to employee consent. However, most employees choose the severance lump-sum payment option (96% of those who are entitled to pensions in 2021) (MOEL, 2022a).

The lump-sum severance pay and the aforementioned honorary retirements reinforce each other in a vicious cycle. Workers prefer a lump-sum in part because of honorary retirement, as they are still fairly young, and starting an own business is a way to earn a retirement income. Also, the lump-sum severance pay can be used to finance their children’s education. Firms are inclined to carry out honorary retirements because the lump-sum is a multiple of the wage at the end of employment, which increases rapidly with seniority given the steep wage/seniority profile in Korea. Therefore, if they keep workers long on the payroll, the bill can become high when they eventually retire. Furthermore, the business sector’s resistance to the corporate pension system reflects in part the requirement that firms must entrust 100% of the funds to financial institutions. In contrast, the severance payment does not have to be funded outside the firm. Workers’ lump-sum benefit is thus at risk should the firm fail. Also, many people have difficulties turning the stock of wealth into a suitable flow of income.

Several steps have been taken to promote the corporate pension systems. In 2020, the government expanded the pension tax credit to make it more attractive relative to the retirement allowance, but the lump sum allowance is nonetheless taxed at rates lower than the income tax. In 2022, employees with retirement pension plans were required to transfer their retirement allowance to an Individual Retirement Pension. In the same year, retirement pension funds for small and medium-sized enterprises of up to 30 employees were introduced, with temporary subsidies to workers and their employers (MOEL, 2022b). However, the severance lump-sum payment option will still be allowed. Taxing the retirement allowance as income, and abolishing severance pay and turning it into a pure pension scheme should be considered.

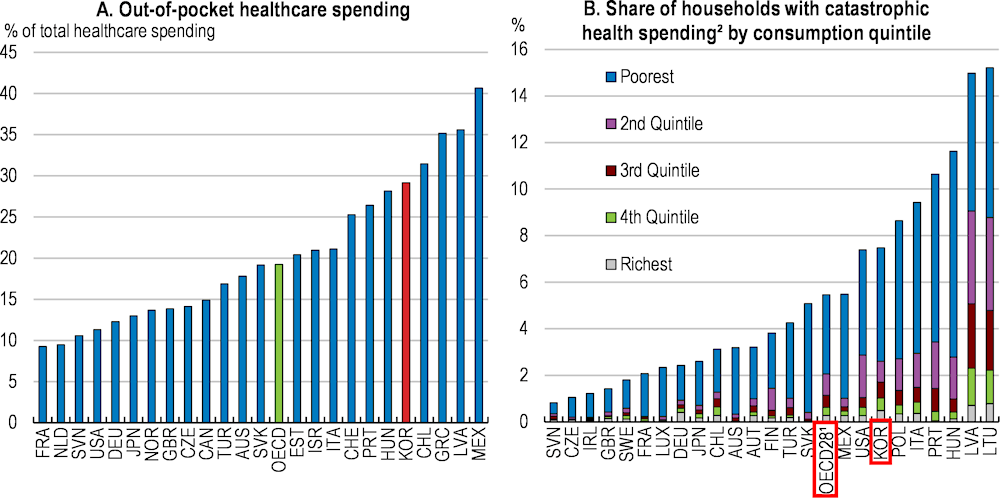

Korea has made rapid improvements in life expectancy and health outcomes, with life expectancy at birth increasing by more than 20 years from 1970 to 2019, twice the OECD average (OECD, 2021e). Korea’s health care system successfully managed the COVID-19 pandemic and led the way internationally with its systems for testing, tracking and isolation, as highlighted in the 2020 OECD Economic Survey of Korea. Korea has also achieved universal access to health insurance in a very short time span. Continuous efforts to make health care more accessible partly explain the 1.1 percentage points growth in public health care spending as a share of GDP between 2015 and 2019, the fastest growth in the OECD. However, Korea’s health care system still has a number of weaknesses, notably high out-of-pocket costs and an over-reliance on hospitals.

Out-of-pocket payments or co-payments are often used as tools to prevent moral hazard, but excessive out-of-pocket costs can reduce access to care and lead to financial hardship (OECD, 2021e). Out-of-pocket spending is relatively high in Korea, accounting for around 30% of health spending, 10 percentage points above the OECD average (Figure 2.19, Panel A). This partly explains why 7.5% of households are exposed to catastrophic health expenditure defined as out-of-pocket payments that exceed 40% of household income, which is two percentage points above the OECD average (Panel B). This also explains why the elderly report high unmet health care needs mainly due to costs (Kim et al., 2018). On the other hand, out-of-pocket health care costs account for only 20% of income for high-income elderly, suggesting inequity in health care access.

1. Unweighted average for the countries displayed in the figure and Belgium, Estonia, Greece and Spain.

2. Catastrophic health spending is defined as out-of-pocket payments that exceed 40% of household income.

Source: OECD Health at a Glance, 2021.

The government started in 2017 with an ambitious plan to expand insurance coverage to all health services except non-essential medical care such as cosmetic surgery by 2022 to reduce high out-of-pocket costs. This plan reflects that out-of-pocket costs for non-covered services have increased faster than for covered services. From 2017, coverage has been greatly expanded to include expensive services like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and ultrasound scans, which were essential for medical treatment but financially burdensome for patients. In addition, co-payment rates for many other health care services, including dental care, have been reduced. In 2018, the government introduced a financial assistance programme for catastrophic medical expenses, refunding 50% of co-payments exceeding KRW 1 million per year for low-income households earning less than 50% of the median income. In 2021, the refund was raised to 70-80%. As a result, out-of-pocket expenses (as a share of health care spending) fell by 3.3 percentage points between 2017 and 2020. The health insurance coverage rate, defined as the proportion of payments by health insurance out of a patient’s total medical expenses, was 65.3% in 2020. It increased only 2.6 percentage points from 2017, and still falls short of the target of 70% by 2022. The Ministry of Health and Welfare evaluates new medical technologies together with various stakeholders including patients, the government, and experts and determines health insurance coverage (Auraaen et al., 2016). The criteria include medical benefits and the cost-efficiency of new technologies. Beyond this, an effort is needed to assess their potential to trigger catastrophic health expenditures.

The social and economic costs of unequal access to health care among poor people should also be considered. A number of empirical studies suggest that poorer access to health care is associated with poorer productivity of workers and shorter healthy life expectancy (e.g. Hao et al., 2020; and Hosokawa et al., 2020). Therefore, another priority to improve health care access is to phase down the remaining family support obligation rule for Basic Livelihood Support Programme (BLSP) health benefits, with due consideration of the additional fiscal burden (see above). In 2017, only 3 % of the population had access to this benefit, well below the relative poverty rate of 17.5% (Choi and Ahn, 2019). This was primarily due to the family obligation rule (KIHASA, 2019 and Sohn, 2019). In 2020, about 50.1% (KRW 7 trillion out of KRW 13.6 trillion) of the total funds for BLSP were used for health benefits. If the family obligation rule for medical benefits is abolished, it is estimated that an additional budget of about KRW 4 trillion per year will be required.

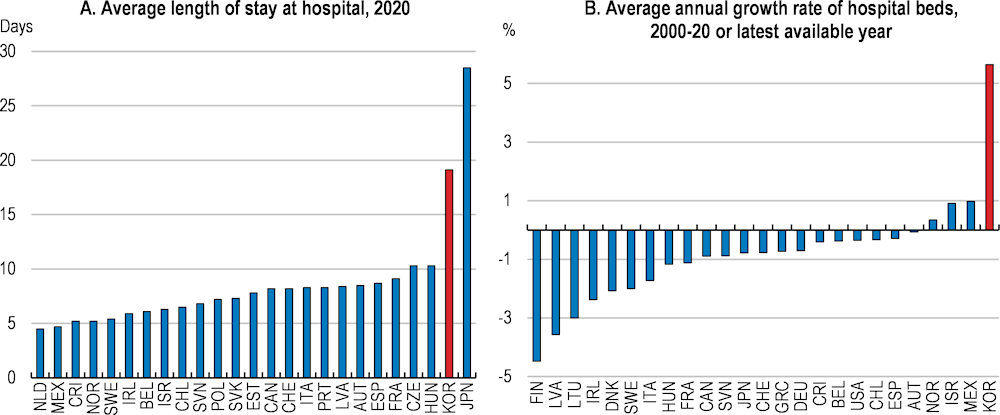

Overreliance on hospital care and specialists, as evidenced by long hospital stays, hinders cost-efficiency in health and long-term care (Figure 2.20, Panel A). After the fastest increase in the OECD over the past decades (Panel B), the number of hospital beds per capita is currently 12.4 per 1000 population, one of the highest in the OECD. The average length of stay in acute care is 7.3 days, above the OECD average of 6.6 days (OECD, 2021e). This high number of hospital beds did not allow Korea to avoid strains in the hospital sector during the COVID 19-pandemic. Like most OECD countries, Korea expanded ICU capacity to well above normal during the pandemic, but other countries with less reliance on hospital care at the start of the pandemic went further in this direction. For example, during the Delta wave, ICU hospitalisations peaked in Korea at just above 22 per million population in late December 2021, which was considered to be full capacity utilisation at the time. ICU hospitalisations during the Delta wave peaked at considerably higher levels in for example the United States (79 per million), Belgium (71), France (58) and Germany (59).

This over-reliance is largely due to weak primary care, that does not function well enough as a gatekeeper authorising specialist referrals and hospitalisation. Solid primary health care is associated with lower health inequalities (OECD, 2020c), as it can ensure access to vulnerable populations that would otherwise struggle to access medical services and specialised care. Indeed, low-income elderly tend to use public primary care services more in Korea than the population average (Sung et al., 2010). The fastest population ageing in the OECD means that a larger share of Korea’s population is likely to suffer from multiple chronic diseases (OECD, 2013). Primary health care with promising innovations and tele-medicine can boost the capacity of health systems to contain and manage future health crises and reduce unnecessary hospitalisation of people who can be effectively treated outside of hospitals (OECD, 2020c).

Note: Panel B: 2019 data for Greece and the United States.

Source: OECD Health statistics (database).

Korean primary care suffers from a shortage of general practitioners (GPs): they account for only 6% of the total number of doctors, far below the 23% OECD average (OECD, 2021e). The shortage of GPs is even more serious considering that the number of doctors per 1 000 inhabitants was 2.5 in 2019, well below the OECD average of 3.5. This shortage is likely to become more acute in the near future, with many GPs nearing retirement and a declining number of new graduates specialising as GPs. The number of admissions to medical school was downsized to 3 058 in 2006 and has remained unchanged so far. To increase the number of doctors, the government decided in 2020 to increase the number of admitted students in medical schools by 400 annually over the next 10 years. However, this has been delayed due to COVID-19 and opposition from doctors’ associations. This should be implemented without further delays, in light of rapid ageing. In addition, efforts are needed to increase the share of GPs among doctors.

Shifting away from the current fee-for-service payment scheme while blocking patients from bypassing GPs when accessing specialists and hospitals could increase the attractiveness of the GP profession and better meet the challenges posed by an ageing population and the rising burden of chronic conditions. User payments for pre-defined health services are the same whether performed by a GP, a specialist or in a hospital, incentivising people to choose specialists and hospitals, which cost the same as a GP, but with higher perceived quality. More fundamentally, a fee-for-service payment scheme may not be the best approach to fostering high-quality chronic care, which is increasingly needed with population ageing (OECD, 2013). Introducing pay-for-performance schemes with bonus payments to physicians who achieve pre-defined targets (e.g., lower obesity rate, smoking cessation, chronic disease management), as in many other OECD countries including the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, could improve quality while making the GP profession financially more attractive (OECD/EU, 2016; and Box 2.5) Studies suggest that the introduction of the pay-for-performance scheme in the United Kingdom is associated with higher retention of GPs, improved primary care quality, and increased job satisfaction.

The United Kingdom’s Quality and Outcome Framework promotes an evidence-based pay-for-performance scheme for primary care, through a rich information infrastructure and a large number of outcome indicators around the prevention and management of chronic diseases. The scheme operates by rewarding general practitioners for achievement against 135 clinical and non-clinical indicators, categorised into four domains: clinical (e.g., chronic kidney disease, heart failure, hypertension); public health (e.g., blood pressure, obesity, and smoking); organisational (e.g. information for patients; education and training); and patient care experience (e.g. length of consultations, access). About 2.4 million patients registered with a GP practice are surveyed twice a year around access, making appointments, quality of care, satisfaction with opening hours, and experience with out-of-hours services. Performance against each indicator attracts points that are used for payment (e.g. maximum 17 points for blood pressures ≤ 145/85 mm). The final payment is adjusted to take account of surgery workload, local demographics and the prevalence of chronic conditions in the practice's local area.

France and New Zealand also have pay-for-performance scheme for general practitioners. In France, for instance, GPs earn financial bonuses if they reach a target rate of 80% of women aged between 50 and 74 years having been screened for breast cancer in the past two years. New Zealand’s pay-for-performance scheme for primary care include clinical indicators (e.g., vaccinations for children and elderly, cervical smears, and breast cancer screening), process indicators (e.g., ensuring access for those with high needs), and financial indicators (e.g., pharmaceutical and laboratory expenditures). A maximum payment of NZD 6 per enrolee could be obtained if all targets were achieved.

Source: OECD (2017); and OECD (2016).

Korea is one of the few OECD countries with universal long-term care insurance coverage (LTCI) for the elderly aged 65 or above. The main objectives of LTCI are to ease the financial burden of the elderly and to reduce social admissions to acute care hospitals (WHO, 2015). However, long-term care is still not affordable for many elderly and there is still an over-reliance on hospital care. Lack of coordination between health care and LTC, weak primary care and a lack of affordable quality homecare stand in the way of the original goals of LTCI.

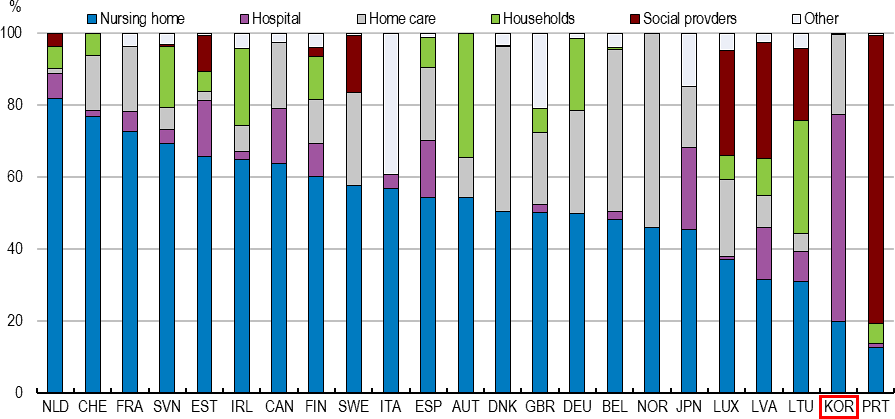

“Social admissions”, meaning that some beds in long-term care hospitals are devoted to social care, are very high in Korea. Long-term care hospitals are uncommon elsewhere in the OECD. In principle they deliver medical services, notably subacute care, palliative care, and rehabilitation services, for patients who need a longer hospital stay. The major priorities of long-term care hospitals are treating patients transferred from an intensive care unit and making them return home. However, many patients in long-term care hospitals do not need such medical care. According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the number of social admission inpatients was around 170 000 in 2019, accounting for around 40% of inpatients in long-term care hospitals. These are generally patients with cognitive impairment and physical dysfunctions who do not need hospitalisation and would receive better and more appropriate care in LTC facilities. Also, the average length of stay per patient in long-term care hospitals was 165 days in 2019, one of the longest in the OECD. This contributes to the fact that most of the long-term care spending goes to hospitals, unlike in any other OECD country (Figure 2.21). Social hospitalisation also leads to inefficient use of resources. Many patients who actually need medical services at the long-term care hospitals are unable to receive it because of a lack of available beds. According to the Ministry of Welfare and Health, around 30% of the elderly who stay in long-term care institutions need hospital care, but do not receive it (KCHA, 2020).

The high social admission rates in long-term care hospitals partly reflect that using hospitals is more financially attractive for care recipients than using LTC institutions or homecare. In Korea, long-term care hospitalisations are covered by the national health care insurance (NHI), whereas costs for long-term care institutions and home care are covered by LTCI. NHI and LTCI both exempt those earning less than 40% of the median income from co-payments, and when this threshold is exceeded, care recipients pay a fixed proportion of the total cost. However, NHI has co-payment ceilings depending on income levels, while LTCI does not. This incentivises many elderly to prefer long stays in hospitals (Kim and Kwon, 2021; and OECD/WHO, 2021). Harmonising the reimbursement scheme between LTCI and NHI by making co-payment ceilings dependent on income levels for LTCI, as is the case in Belgium and Japan (Colombo et al., 2011), would incentivise users to choose the best suited service for their needs. Imposing additional charges for those who remain in hospitals after their medical care has ended, like in Ireland, can also be considered.

Total long-term care spending, by provider, 2019

Note: 2018 data for Japan. Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Japan and Korea do not report social long-term care. The category "Social providers" then refers to providers where the primary focus is on help with instrumental activities of daily living or other social care.

Source: OECD Health Statistics (database).

Financial incentives faced by LTC hospitals also play a role in the high rates of social hospitalisation. In 2008, the reimbursement method for hospitals was changed from a fee-for-service system to a flat-rate per diem reimbursement for LTC hospitals only, given that relatively standardised treatment is provided over a long period of time. This payment model, which incentivises hospitals to cherry-pick low-cost patients with mild symptoms and let them stay for a long period, needs to change. In Japan, for example, case-mix-based payments, which allow adjustment of flat-rate per diem payments according to the severity of illness and types of patients, were introduced to reduce social hospitalisations. In Belgium and Canada, per diem payments are adjusted to incentivise treatment of more severely impaired patients (Colombo et al., 2011).

In addition to the financial incentives for both users and suppliers, the lower quality of LTC institutions and homecare also contributes to high LTC hospitalisation. There has been an excess supply of mostly private LTC institutions and home-based care, which results in wasteful competition with financially unsustainable price discounts rather than quality improvement (Seok, 2017). Korea has developed an LTC quality framework with legal regulations on LTC quality since 2009. Both the National Health Insurance Service and local governments are responsible for the quality monitoring of LTC facilities. Based on evaluation criteria, local governments have the authority to approve or close LTC providers, but they are not active in doing so. This partly reflects a need to improve the reliability of indicators for quality assessment (Yoon, 2021; and Pak, 2017). The United Kingdom and Portugal, for instance, developed a large number of outcome indicators around the management of LTC providers, not only on adverse health events and client satisfaction surveys, but also on the quality of life of LTC recipients (EC, 2019a; and OECD/EU, 2013). More systematic monitoring and quality evaluation based on reliable outcome indicators would help make informed choices about appropriate corrective actions and sanctions towards LTC providers.