Tariff policy and related regulatory framework have a major role among the modalities and incentives towards aggregation of water services in Estonia. While the framework in place is robust and essentially in line with the needs and policy priorities, some adjustments could be considered – in particular to the depreciation method for granted assets - to provide stronger incentives for utilities and municipalities to consider aggregation as a practical way forward. Other dimensions include benchmarking and information sharing on the performance and ambition of utilities.

Towards Sustainable Water Services in Estonia

6. Report on tariff regulatory framework

Abstract

6.1. Background and objectives

The Ministry of the Environment of Estonia jointly with other governmental authorities (the Ministry of Finance, the Minister of Public Administration), the European Commission – DG Reform, and the OECD are partnering to enhance the sustainability of water supply and sanitation services in Estonia. The Project will support the preparation of a roadmap for the consolidation of the water utility sector, a requisite for a sustainable and socially acceptable financing strategy and a broader water sector reform in Estonia. See the Detailed Project Description, for more information on background, scope and process.

The specific objectives of this Project are:

to support the initiatives of national authorities to design their reforms according to their priorities, taking into account initial conditions and expected socio-economic impacts

to support the efforts of national authorities to define and implement appropriate processes and methodologies by taking into account good practices of and lessons learned by other countries in addressing similar situations

to assist the national authorities and water utilities in enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of human-resource management, inter alia, by strengthening professional knowledge and skills and setting out clear responsibilities.

This report is focused on the tariff regulatory framework, and in line with this it considers the methodology and process used for tariff setting purposes. It is common, however, for economic regulators – as part of their assessment of the appropriateness of potential tariff setting decisions – to consider what utilities plan to, and have been, delivering while charging the relevant tariff level. This is of considerable significance because the approach to tariff setting can have a material bearing on decisions that may affect future performance, both in terms of the cost efficiency with which services are provided and the quality of those services. Given this, in addition to addressing a number of tariff methodology issues, this report highlights and recommends a number of ways in which broader incentive considerations can be incorporated into the regulatory framework, and treated as an integral feature of the tariff setting process.

The current arrangements, and potential options for further development, are considered and assessed below in the light of relevant international experience. The relevance of considering international experience is enhanced by the fact that the overall economic regulatory framework for WSS in Estonia shares a range of common features with those which apply in many other jurisdictions (for example, in terms of some of the responsibilities given to an economic regulator, and the broad (‘building blocks’) approach the regulator applies to tariff regulation).1 Also, the broad question of how to meet WSS-related environmental challenges in financially sustainable and socially acceptable ways can be understood as one that all jurisdictions have had to, and will continue to face to some extent.

At the same time, the feasibility and appropriateness of adopting different potential approaches will be heavily dependent on the specific circumstances that currently apply to WSS provision in Estonia, and on how those circumstances have emerged over time. Given this, the report does not seek to provide a broad overview of international experience, as there would be a significant risk of such an overview being unhelpfully generic and of limited value. Rather, the approach adopted below is to focus attention on circumstances that apply, and the current and emerging challenges faced, in WSS provision in Estonia, with international experience then drawn upon more selectively either to help highlight closely related experiences, or to illustrate potential options that look to merit particular attention.

The first section situates the prevailing approach for depreciation used by the CA to set WS tariffs vis-à-vis other options. It concludes the prevailing approach is suitable in the Estonian context, but could be more effective if the conditions to allow accelerated depreciation were clearly stated. Affordability and performance incentives are used as main criteria in the discussion.

The focus then shifts to the basis upon which price reviews are triggered, and potential adverse incentive effects associated with the current (voluntary) arrangements are highlighted. The potential for using periodic reviews, and regulatory commitments with respect to the scope of price reviews, to address these incentive issues is highlighted.

Another section presents different methods that can be used in Estonia to incentivise consolidation by using more systematic comparison of utilities performance and by challenging the level of ambition of development and investment plans. References are made to international experience, in particular Australia, England & Wales and Portugal. A final section captures the recommendations that derive from the analyses.

6.2. The tariff formula and how it is applied

The Competition Authority (CA) was established as the economic regulator of WSS companies in Estonia in November 2010, with responsibility for approving prices for WSS services2 in relation to wastewater collection areas with a population equivalent (PE) of 2000 or more. Before that time, all WSS prices were set by local governments, and local governments had continued to approve prices in relation to wastewater collection areas with less than 2000 PE up until the end of 2021. From the beginning of 2022 the CA has had responsibility for approving all public WSS charges (i.e. including those in relation to areas with less than 2000 PE).

The CA adopts a form ‘building block’ approach to determining allowed price levels that has been widely used internationally over many years. In particular, it approves prices based on its assessment of allowed revenues, which are made up of its assessment of a reasonable allowance for:

1. Operating expenditure (opex) requirements;

2. Depreciation; and,

3. A return on capital.

Based on the duties and powers it has under the Public Water Supply and Sewerage Act, the CA has issued:

The methodology it uses for calculating cost-based tariffs.

Two questionnaires (one more detailed, the other simplified) for companies to complete as part of the price approval process.

Guidelines to water companies on submitting price applications (i.e. how to fill out the questionnaires and what additional documents should be provided).

The CA’s view of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) that should be used when determining a reasonable allowance for a return on capital.

The broad ‘building block’ approach that the CA uses is well established, and provides a flexible framework that is well suited to addressing the range of issues it may face, with the application of this broad approach in different international contexts having included and been supplemented with a range of other regulatory initiatives (including in terms of the approaches that have been developed for cost assessment and recovery, and for incentivising aspects of service delivery).

The remainder of this section focuses on two issues related to the tariff formula and how it is applied that look to merit particularly careful attention:

The approach taken to cost assessment.

The approach to determining the allowances for depreciation/capital maintenance to be included in the tariff formula.

6.2.1. Cost assessment

The use of cost assessment approaches in the determination of allowed prices is central to the economic regulation of utilities. The use of these approaches can be highly relevant to consolidation incentives in Estonia because they can provide a basis for the CA to constrain the funds that companies are allowed to recover from their customers over time. The application of such constraints has the potential to incentivise companies to find ways of achieving efficiency improvements, including through consolidation approaches, in order to improve the financial position they face, and can expect to face in future years.

In its cost assessment work, the CA applies three broad approaches that have been widely used internationally:

1. The review of how cost levels have evolved (and are forecast to evolve) over time, including by reference to relevant available price indices (the CA considers movements relative to the Consumer Price Index).

2. Benchmarking approaches that involve the comparisons being made with relevant cost measured for other companies.

3. Detailed assessments of particular cost areas, and of the justification presented for the appropriateness of the associated actual and forecast cost levels.

Each of these approaches can be applied in a range of different ways at different levels of aggregation, and potentially serve a range of different purposes within the price review process given the specific circumstances under consideration. It is notable with respect to (1) above, that a focus on the relationship between the evolution of total (and/or average) costs and relevant price indices can be viewed as concentrating attention on the overall implications of cost levels for consumers (in line with the initial development of the RPI-X approach). At the same time, regulators typically also look at cost dynamics at a range of more disaggregated levels, with this potentially providing a basis upon which more detailed assessment work can be prioritised (e.g. with close attention paid to areas where costs are forecast to materially increase).

Regulators also often apply benchmarking approaches at different levels of aggregation that can include:

Totex benchmarking: i.e. the benchmarking of total opex + capex requirements.

The benchmarking of ‘base’ totex (or ‘Botex’): i.e. the benchmarking of total opex + capex, excluding expenditure on enhancements, such as the achievement of water quality improvements.

Opex benchmarking.

Totex, Botex or Opex benchmarking focused on particular business units/activities: e.g. water treatment, treated water distribution, wastewater collection, wastewater treatment.

The benchmarking of the costs associated with more narrowly defined activities: e.g. pipe replacement costs, billing and customer support costs, etc.

The CA looks to have adopted a pragmatic approach to its use of benchmarking to date, including through the grouping of companies for comparison purposes depending on their ratio of sales volume to length of pipe. International experience has highlighted some of the complexities that can be faced when seeking to develop reasonably robust benchmarking models, particularly when the implications of significant differences in density/sparsity conditions need to be taken into account, as is the case with Estonian WSS services.

A specific assessment concern that has been highlighted in the Estonian context is that some of the reference data that is available for benchmarking is too old, such that it does not provide an accurate and up-to-date reflection of relevant costs. Where cost conditions are relatively stable over time, older data may continue to provide a valuable input into benchmarking assessments in a relatively straightforward way. However, where cost conditions are subject to material changes, more careful consideration typically needs to be given to whether, and if so how, it is appropriate to use older cost data. In practice, much will depend on how straightforward it is to isolate what driven changes in conditions over time, and on the availability of adequate techniques for taking these drivers into account. For example, it may be possible to reflect some differences in cost conditions by references to available indices, either when considering costs are a relatively aggregated level (which broad measures of price movements, such as a consumer price index, may be helpful), or considering more specific areas such as labour or energy costs. Another underlying driver may be changes to the types and levels of activity that companies are undertaking over time, with this flowing through to material differences in the cost pressures that are faced (as may be the case, for example, where costs are higher because of the need to meet more stringent environmental requirements). Where there are considerable changes to cost conditions over time, and where it is not feasible to take them into account adequately through seeking to identify the effects of workload changes and broader cost pressures, then it may simply be that older cost data comes to be viewed as relatively uninformative, and it may be appropriate for benchmarking to focus primarily on the use of data that been gathered relatively recently.

The most appropriate way to develop the specific benchmarking practices that are to be applied will depend on a range of detailed and context specific matters that go well beyond the scope of this assessment. Also, importantly, the quality and sophistication of benchmarking (and of the information collection arrangements on which it is based) is typically something that evolves gradually over time, as potential detailed options are identified and tested, and experience with existing methods grows. A key broader consideration therefore concerns how effective this process through which benchmarking evolves over time is likely to be. Transparency and effective stakeholder engagement are typically key factors in this context. In particular, transparency in relation to relevant cost and cost driver information can help improve both the usefulness of, and the confidence that companies and other stakeholders have in, benchmarking models by allowing more open consultation and challenge processes to inform what is inevitably a difficult and approximate process. Further comments on transparency issues are provided in a later section in relation to performance incentives.

6.2.2. The determination of appropriate allowances for depreciation/capital maintenance

Under Estonian water law,3 the allowances for capital costs (the depreciation and return on capital allowances) that are included in the tariff formula should not cover:

Assets funded by connection charges paid by consumers; or

Assets financed by EU funds, by state or local governments or by other institutions to the extent of the value of financial assistance.

The exclusion of assets funded by connection charges from the Regulatory Asset Base (RAB), which companies receive a depreciation and return on capital allowance on the basis of, is a standard approach across many countries, and reflects the different basis upon which connection assets are typically funded. However, the treatment of assets funded from financial assistance raises some broader questions concerning the basis upon which it is appropriate to make provisions for depreciation, and associated questions concerning the funding of future capital maintenance requirements.

Allowances for depreciation/capital maintenance can be viewed as having both a backward and a forward-looking role:

The backward-looking role can be understood as concerned with the recovery of capital expenditure that was incurred in previous years.4 Under the standard building block approach (which, as noted above, the Estonian tariff formula broadly follows), capital expenditure is added to the Regulatory Asset Base (RAB) and recovered over time through depreciation of the RAB. Depreciation under this approach is sometimes referred to as the return of capital, as it can be understood as providing for the return of part of the stock of past capital expenditure that has yet to be recovered by investors (with a return on capital also provided for by applying the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) to the residual (as yet unrecovered) RAB in each given year).

The forward-looking role can be understood as more directly concerned with the financeability of future capital maintenance requirements. In particular, the depreciation allowance results in an additional cash income that can be earned from charges, and that additional cash income may affect the extent to which a company will be able to fund future capital maintenance requirements through revenues from customers, and its ability to (and terms upon which it can) raise external funds, typically through borrowing.

The approach adopted in Estonia of excluding the value of assets provided by EU funding when calculating a reasonable depreciation provision, can be viewed as clearly consistent with the backward-looking role referred to above. That is, the grant-based nature of the assistance means that this funding has not resulted in WSS companies facing outstanding accumulated amounts of past investment that stand to be recovered from consumers. Given this, one key question with respect to the regulatory treatment of this past funding looks to concern its implications for the financeabilty of future capital maintenance requirements (i.e. the forward-looking role referred to above).

We understand the approach adopted by the CA to this future capital maintenance financeabilty issue to be broadly as follows:

1. Future capital maintenance is treated in the same way as any other new capital expenditure: it is added to the RAB, and allowed for over time in the tariff formula through the allowances made for depreciation of the RAB, and for a return on the outstanding level of the RAB.

2. A company can identify financeability difficulties it may have under this approach as part of its price review application process, and the CA may be willing to allow for a more accelerated depreciation assumption to apply (than it would otherwise expect to use), where a compelling case has been made that such a change would be appropriate.

We consider that, in broad terms, this existing CA approach is likely to provide an appropriate basis upon which to determine the allowances provided for depreciation/capital maintenance within the tariff formula, because it can provide a pragmatic and flexible way of allowing financeability issues to be addressed where they have been shown to be material, while also guarding against the risk of WSS customers facing unduly high charges. We explain further why we consider this to be the case below, including by highlighting some of the limitations that may be associated with adopting potential alternative approaches. We also highlight some ways in which it might be desirable to develop the broad approach that we understand the CA to be currently applying.

Three further key factors that underpin our assessment of this issue are as follows:

Affordability considerations;

Efficiency incentives;

Intergenerational equity considerations.

These factors are highly relevant when one assesses the desirability of potential alternative approaches that could be adopted to the determination of allowances for depreciation/capital maintenance. Two alternative approaches that are used in a range of jurisdictions are: (a) a form of current cost depreciation (CCD) approach applied in relation to all relevant assets; and, (b) an infrastructure accounting approach that effectively treats capital maintenance as though it were opex (and so involves funding expected capital maintenance requirements directly through prevailing charge levels).

Limitations of a CCD based approach

Adopting a form of CCD approach would involve including a depreciation provision in relation to EU funded assets. The case for adopting such an approach can be viewed as relying heavily on the anticipated long-run average relationship between appropriately calculated depreciation requirements on the one hand, and future capital maintenance requirements on the other. Put differently, it relies on a depreciation approach being viewed as a ‘good enough’ estimate of likely long-run average capital maintenance requirements and – given this - of the contribution to (current or future) capital maintenance requirements that it is considered appropriate for the current cohort of consumers to make.

In practice, however, this kind of CCD approach looks to suffer from major limitations in relation to both affordability considerations and efficiency incentives. Affordability considerations are important as adopting the approach would result in a substantial increase in allowed WSS charges, other things equal. In principle, one could seek to dampen this effect through the use of some form of glidepath, such that there was a transition to this kind of CCD approach over time that took some account of affordability concerns. However, it is important to recognise the potential cash implications for utilities of adopting such an approach. There looks to be a significant risk that such an approach could provide a considerable over-estimate of likely capital maintenance requirements over at least the next few years, particularly given that many of the EU assets were installed relatively recently. Given this, the approach would likely result in companies effectively being funded for capital maintenance some years ahead of when spend requirements would actually arise

This could have the effect of materially relaxing the financial pressures that utilities might otherwise face, as the higher depreciation allowances would (in the absence of other regulatory protections) effectively provide additional financial headroom when costs are being managed. While - in principle - this financial headroom could be used to build up a financial provision for when higher capital maintenance levels are required, there may be a material risk that the headroom instead is effectively used to insulate the utility to some extent from the pressures for efficiency improvement that it may otherwise face. That is, there is a risk that the better financial position utilities would be in as a result of applying this kind of CCD approach would tend to allow a greater degree of deferral in relation to the achievement of efficiency improvements, because it effectively softens the efficiency improvement constraints that the regulator would otherwise be putting on the utility.

While it is sensible to take stock of how these points fit with intergenerational equity considerations, it is not obvious that such considerations should be viewed as particularly supportive of applying a CCD approach to EU funded assets. The application of the current tariff methodology would – without any change of treatment in relation to EU assets – tend towards the full application of a form of CCD approach over time (albeit perhaps quite a long time, given relevant asset lives), as EU assets are refurbished/replaced. The key intergenerational equity consideration therefore can be understood as concerned with how the benefits of EU funding should be shared between different cohorts of customers over time. The EU funding provides for significant flexibility in terms of what the profile of movement towards some kind of full CCD approach could look like. While different choices in relation to that profile will have different intergenerational implications, it seems important that decisions concerned with that choice of profile should be guided to a significant degree by efficiency and affordability considerations in the short- to medium-term, given in the central importance of efficiency improvements to the achievement of more affordable outcomes in the medium and longer-term.

Limitations of an infrastructure accounting-based approach

The infrastructure accounting approach that has been used for many years in England and Wales (and in different ways in a number of other jurisdictions and contexts) for a large category of long-lived assets (typically underground assets: pipes, sewers, etc.), provides a notable alternative to the use of a depreciation approach. Under this approach, the cost of infrastructure renewals is effectively expensed each year (i.e. treated as though it were opex) rather than added to the RAB. In line with this, it can be regarded as a form of ‘pay as you go’ approach to funding capital maintenance of a given set of assets. As such, the approach assumes that these capital maintenance requirements are funded directly from customer charges, and thus do not result in additional financeability challenges.

This approach would not be expected to have the same extent of adverse effect on efficiency incentives highlighted above as potentially arising under a CCD approach. Under the CCD approach, that incentive problem arises because funding decisions are effectively decoupled from specific future identified capital maintenance requirements, and are instead determined by reference to the value of past investments that were funded by external sources (and hence do not themselves give rise to ongoing financing costs). Under an infrastructure accounting based approach this decoupling issue does not arise, as attention is focused instead on estimating, and then fully funding, likely capital maintenance requirements in the next period. That said, the efficiency of the proposed approach to capital maintenance may itself be an important matter for the regulator to seek to test, and so the basis upon which funding for capital maintenance through charges can be secured may be important in terms of seeking to generate desirable efficiency incentives (discussed further below).

Beyond this, the limitations of adopting a ‘pay as you go’ approach can be expected to relate largely to affordability and bill volatility considerations. Affordability concerns can arise because under this approach, all relevant capital maintenance would be recovered through charges in (roughly) the same time period in which the costs are to be incurred, such that this approach may imply a steep upward movement in prices in the relatively short-term in order to fund capital maintenance requirements. Bill volatility concerns arise from the often lumpy nature of WSS capital maintenance requirements. The adoption of a depreciation-based approach can be understood as addressing this lumpiness through temporal smoothing, with customer charges including a provision for future capital maintenance requirements to be paid each year irrespective of actual capital maintenance requirements. The ‘pay as you go’ approach does not include this kind of explicit temporal smoothing, but where it is applied to relatively large regional water companies – as for example in England and Wales - considerable temporal smoothing is provided for indirectly, given the mixed age and condition profiles of the portfolios of assets across those companies. Applying a ‘pay as you go’ approach to a smaller company could imply considerable tariff instability, as overall capital maintenance requirements may be highly sensitive to lumpy requirements associated with a relatively small number of assets, with that then raising questions over its feasibility as an approach.

Allowing some scope for accelerated depreciation as a hybrid option

The CA’s current broad approach gives it scope to consider allowing some accelerated depreciation on a case-by-case basis. It is notable that, in principle, the use of accelerated deprecation could (in the extreme) deliver a pay as you go approach: that is, depreciation could be accelerated such that all of the relevant capital maintenance costs are allowed to be recovered in the year they are incurred. The CA’s approach can, therefore, be viewed as a form of hybrid option that allows movement towards a pay as you go approach, but only when – and to the extent that – a number of regulatory conditions are satisfied. There may be significant benefit in seeking to further formalise and articulate this regulatory approach – for example, through publishing guidance – so that there is greater clarity over the scope for utilities to seek accelerated depreciation provisions to help address financeability constraints they may face, or expect to face, and over the conditions that are likely to need to be satisfied in order for that accelerated depreciation to be allowed.

Those conditions could be developed in ways that take explicit account of the risk that providing more funding through charges may tend to dampen the efficiency incentives that might otherwise apply. In line with this, regulatory decisions on the extent to which accelerated depreciation should be allowed could take account of the utilities performance (including evidence on the efficiency of its operations), with this providing a means of guarding against the risk that the allowing of accelerated depreciation could act to ‘soften’ the budget constraints that utilities would otherwise be expected to face, and dampen efficiency improvement incentives. The CA could underpin this approach by identifying relevant cost and service performance criteria that it would expect companies to satisfy in order to qualify for potential access to accelerated depreciation provisions.

The approach could also be linked directly to the extent to which different forms of consolidation plans were being pursued, with greater scope for the acceleration of depreciation provided to utilities that develop such plans in a robust and credible manner.5 Some forms of consolidation may greatly enhance the scope for managing bill profiles over time as significant levels of capital maintenance come to be required in relation to what were EU funded assets. In particular, as well as potentially increasing the borrowing capacity of companies (and therefore their ability to fund future capital maintenance requirements without seeking additional revenues from customer charges through accelerated depreciation), consolidation can also allow for future capital maintenance and funding requirements to be managed across a larger and more diverse portfolio of assets, and thus allow for greater smoothing of associated work requirements and bill impacts.

6.3. The basis upon which price reviews are triggered

This section focuses on the specific issue of what triggers price reviews, and highlights some potential incentive issues associated with the current approach. It is proposed that consideration be given to the use of defined periodic review criteria such that companies can expect to face a price review every few years.

6.3.1. Potential incentive issues under the current arrangements

Under the current WSS arrangements in Estonia, price reviews are triggered by an application from the relevant water company. Once determined by the regulator, approved prices apply until the regulator determines a new price following a subsequent review triggered by a further application from the company.

These arrangements have the potential to result in a self-selecting asymmetry with respect to when companies apply for, and thus are subject to price reviews. That is, companies may face relatively strong incentives to apply for a price review when their current tariff levels are viewed as insufficient to cover their actual and/or forecast costs. By contrast, the incentive to apply for a price review might be expected to be relatively weak for companies that are able to cover their actual and/or forecast costs based on current tariff levels.

Given this, the current basis upon which price reviews are triggered could have a number of potential incentive implications for companies that are operating relatively successfully under their existing price control. For example, it is possible that:

If that company had managed to reduce its costs such that it could be viewed as earning a financial surplus at the current allowed tariff levels, then it would be unlikely to want to apply for a price review, as that review might be expected to result in a reduction in the allowed tariff levels (other things equal), and removal of the surplus (with the benefit of the cost savings it had made passed on to its customers).

Success in opex reduction might be associated with a tendency to seek to avoid other changes that may be expected to trigger a price review, and potentially result in a tougher control. This could potentially affect broader attitudes and decision making in a range of different ways including that:

The company may tend to prefer delaying investments that would require a price review to be triggered (i.e. the decision to undertake the investments may result in a requirement for additional funds from customer charges and thus a request for a tariff review)

The company may tend to prefer to avoid other changes - including potentially consolidation – that might be expected to trigger a price review, and remove financial headroom that the company might otherwise have: by providing ‘successful’ companies with a means of choosing to defer when its tariffs are subject to regulatory review, the current arrangements may tend to disincentivise companies from engaging in consolidation activities that may trigger a review at an earlier date.

The above points are presented in a relatively speculative manner, because they are based on identified possibilities under the current arrangements rather than on evidence that these possibilities have eventuated and resulted in harmful effects. However, it is important that consideration is given to the sorts of tendencies that might arise when regulatory frameworks are being developed and reviewed. The identification of the above possibilities is not intended to imply that any ‘wrongdoing’ is likely, or to suggest that avoiding the triggering of price reviews is likely to be a prominent motivation when investment and consolidation options are being contemplated. But at the same time it would be perfectly understandable if companies did give some weight – implicitly or otherwise – to the prospect of avoiding or deferring a price review, and there may be many good reasons for doing so, including that the review may generate unwanted distractions from and disturbances to ongoing service provision plans. As a matter of regulatory design, it is important to try to avoid the emergence of such tensions, as they can result in undesirable diversions of effort and attention, and to shift focus away from the kinds of improvements that are likely to be important for the future development of the WSS sector in Estonia.

It is also notable that the issues described above can be understood as forms of a broader type of regulatory incentive problem that can arise and that relates to what can be described as ‘ratchet effects’. Ratchet effects can arise because the regulatory conditions that a company faces are likely to be affected by new information that comes available. This can mean that there is a risk that – for a given company - the result of it engaging in successful efforts to deliver efficiency improvements may be a tougher operating environment than it would otherwise have faced. That is, having shown it can operate at lower cost, the extent to which it is allowed to recover costs through charges may be ‘ratcheted down’ by the regulator such that it is no better off. It is widely recognised that this kind of ratcheting approach can undermine improvement incentives. The underlying issue here concerns the extent to which companies that take steps to deliver efficiency benefits should be allowed to share in those benefits, in order to give them an incentive to identify and deliver them in the first place. Considering the underlying concerns noted above in relation to this broader regulatory issue of ratchet effects can help with the identification of potential policy responses which is considered below.

6.3.2. The use of periodic reviews and regulatory commitments

Two approaches that could help guard against problematic tendencies of the kind noted above arising are:

The use of periodic reviews; and,

The development of some relevant regulatory commitments/policy positions.

These are considered in turn below.

The use of periodic reviews

A standard way of seeking to address ratchet effect concerns is through the use of some form of ‘regulatory lag’, such that charges are only fully adjusted to reflect efficiency savings periodically. This can allow the company to benefit to some extent from lower costs ahead of that adjustment point. A common approach is for costs to be re-assessed, and prices re-determined, at regular defined intervals, with this providing scope for companies to benefit from savings they are able to make in the period between re-determinations.6 The use of pre-defined price review points would remove the scope for a relevant company to seek (implicitly or otherwise) to influence when a review would take place through its decision making. That is, it would remove the scope for a self-selection bias to arise in relation to when the relevant company is reviewed.

Using defined price review periods can, however, result in other potentially undesirable effects. Perhaps most notably, they can result in material divergences between allowed charges and underlying costs enduring for a significant amount of time ahead of the next review. The forecasts upon which a price control was set may end up significantly out of line with prevailing conditions, and this can itself become a material source of tension, including because the ongoing financeability of a company may be undermined because of divergences between regulatory forecasts and outturn conditions.

One important issue this raises is the extent to which it may be feasible and desirable to provide for prices to be adjusted automatically in between regulatory reviews by reference to movements in defined indices. In particular, where feasible it may be desirable for some input price risks (including potentially those associated with movements in energy prices – a source of significant current concern) to be managed through the use of some form of indexation, such that prices can better reflect prevailing conditions without the need for further regulatory review. The extent to which such approaches (which effectively involve allocating some relevant input price risks to water customers rather that to companies) are desirable is likely to depend on the degree to which companies may be better placed to manage the relevant risks (given the options they have available to them, including in terms of potential hedging strategies). Where input price movements are largely outside of the control of WSS providers, allowing for some automatic adjustments to prices between regulatory price reviews can provide an effective means of ensuring that water tariffs do not get too far out of line with relevant costs when circumstances change. This can help provide for a more robust price control arrangements, as it can avoid material changes in circumstances resulting in pressures for the price control to be ‘re-opened’ and another regulatory review to be initiated.

These forecasting issues also raise important questions over what duration it is likely to be appropriate to set a price control for. The use of longer defined price control periods is typically viewed as potentially providing for more high-powered incentives during the control period. However, where there is material uncertainty over the evolution of relevant variables, and where there are material limitations in the extent to which it is credible for companies to bear the risks associated with longer price control periods, there may be a strong case adopting a relatively modest defined price control period. While the use of 5-year controls is common in the water sector, if - and to the extent that - periodic reviews were to be used, a shorter time period - such as 3 years - may be more appropriate for consideration in Estonia while understanding of the risks that may associated with setting longer control periods is further considered and better understood.

The scope for using such a periodic review approach, though, is likely to be heavily affected by the context which the regulator currently faces in Estonia. Perhaps most importantly (and as was noted earlier), the CA now has responsibility for approving all WSS tariffs, and – given the fragmented nature of, and the number companies currently operating in, the WSS sector – the prospect of implementing periodic reviews of charges for across all companies may raise major practical and logistical challenges.

This raises an important question of prioritisation, and associated risk management considerations. Relevant factors here include the following:

There may be a strong proportionality-based case for focusing on larger companies, at least initially.

The ‘ratchet effect’ concern highlighted above was related, to a significant degree, to companies that may be relatively successful and in a position to contemplate consolidation with one or more currently less successful other companies. This may provide a further, policy-targeting based rationale for focusing on larger companies, at least in the first instance.

A further important consideration concerns the scope for coordination benefits. This may suggest some benefits from seeking to review companies – to some extent at least – in clusters. The development of clusters could take explicit account of the likely scope for efficiency benefits being secured through different forms of consolidation, such that – for example – WSS utilities in defined geographic regions could be reviewed together, with this providing an opportunity for companies to submit evidence and be challenged on their assessment of the scope for consolidation benefits to be achieved. Price control determinations in specific regions could be adapted to and reflect the consolidation plans that have been developed and presented, and in particular, assessments of the scale and timing of relevant consolidation costs and benefits.

In principle, this issue of the clustering of reviews could be treated as distinct from, and could be approached separately to, decisions over the extent to which defined, periodic reviews are to be used. For example, the adoption of a cluster-based approach might imply that, when reviewing a given ‘large’ company, it would be desirable to also undertake some form of price review for other smaller companies in the same broad geographic location. But this need not imply that that the same review approach be used, or that the same duration of price control be imposed. Rather, clustering could be used more selectively and separately, where identified as potentially beneficial. The broader point here is simply that there may be some benefit from reviewing tariffs in clusters, and so giving some consideration to the potential options for and benefits of adopting clustering approaches may be desirable when price reviews are being initiated.

The development of regulatory commitments

The above focuses attention largely on constraints over when price reviews take place (i.e. such that they may only be expected to take place at defined intervals). A different, and potentially complementary, approach would be to consider trying to identify constraints on how future price reviews would take place. In particular, if consolidation activity would be likely to generate a price review, then there may be significant benefit from seeking to define some principles that would be expected to guide how that price review was undertaken. For example, it may be that the scope of the price review that would be triggered by consolidation activity could be explicitly defined in a relatively narrow way, such that it was focused on determining what the forward-looking approach should be to the sharing of the benefits (and risks) associated with the proposed consolidation activity. This could involve identifying a principle that the price review process should not be seeking to re-open the price controls that had been set for the companies individually.

The approach taken to the assessment of water mergers in England provides an example of one form that this kind of assessment could take. That is, the merger assessment can be viewed as taking the prevailing price control arrangements as given, and as the starting point, and focusing on the question of whether any adjustments to those existing arrangements would be justified as a result of the scope for the merger to have other adverse effects. In the water sector in England, the key consideration is typically whether the merger can be expected to hinder the ability of the regulator to set appropriate controls given the loss of a comparator company that could otherwise be used in benchmarking assessments. However, this comparator loss issue looks highly unlikely to throw up significant concerns for some time in the Estonian WSS sector, given the extent of fragmentation at present. The broader relevance of this example, though, is that it illustrates the scope for limiting the assessment of pricing associated with consolidation proposals to a narrow set of issues, in order to try to avoid the act of consolidation triggering a more general pricing ‘reset’ (given that – as was above - that could potentially act as a deterrent to otherwise desirable behaviour).

6.4. Options for enhancing the incentive arrangements

The tariff formula currently provides a way of applying some incentives related to the management of cost levels. In particular, it provides a framework that can be used to underpin price reviews over time, and that can allow regulatory challenges and adjustments to charge level proposals to be identified and applied through a widely recognised structured approach (i.e. the assessment of the building blocks discussed above). This section focuses on three potential ways in which the existing incentive arrangements could be enhanced that look to be well suited the current Estonian context. In particular, the following options are considered:

Scope for greater use to be made of KPIs to generate desirable reputational incentives and transparency benefits; and,

The development of more targeted incentives to encourage the development of efficiency-enhancing consolidation plans.

Incentives that seek to guard against unduly limited considerations of potential consolidation options.

6.4.1. KPIs, reputational incentives and transparency benefits

Attention so far has been focused on performance in relation to costs. While this is central to economic regulation, regulators typically also put considerable effort into providing for broader performance assessments, and associated incentives. One reason for this is simply that there are a broader range of measurable aspects of performance that can be expected to have significant relevance for the overall outcomes that are delivered for customers and the environment. The monopoly nature of WSS services can mean that unduly limited attention would be given to these factors in the absence of some form of regulatory pressure, and that customers have limited access to information that can help them identify and compare the cost and quality of the services they are required to pay for. Where bill increase are required, this kind of lack of transparency and accountability can underpin significant customer acceptability problems, and make it more difficult to articulate – in credible ways – why bill increases should be viewed as justified, and as delivering demonstrable improvements.

An important additional consideration here concerns the risks of focusing incentive regulation on costs in a relatively narrow way. A standard concern in incentive regulation is that cost pressures may be resolved (deliberately or otherwise) through some form of ‘under-delivery’. That is, one way in which a company may be able to out-perform a price control settlement (or lessen the extent of financial underperformance that might otherwise result), is to simply deliver less. This could manifest itself is through cost savings being made in ways that tend to undermine some aspects of service quality, and the risk of this has tended to be an important factor in the attention regulators in wide range of jurisdictions and sectors have given to the identification of service quality measures that can then be monitored alongside (or as part of the mechanics of) price control arrangements.

The transparency of performance information is a key consideration here, and the approaches that are adopted to providing for transparency – and, more broadly, for stakeholder engagement – provide an important part of the way that regulators typically seek to encourage performance improvements and guard against the deterioration of performance. The following first sets out some of the different ways in which transparency can help generate better outcomes from regulatory processes, before describing a particular example – the approach used by ERSAR in Portugal – that looks well suited as a relevant reference point against which potential developments to the transparency arrangements in Estonia could be considered.

Recognising the scope of potential transparency benefits

Transparency requirements have been used as an important tool by many regulators internationally, and can help promote improvements in a wide range of ways, including by:

1. Improving company, and company owner, awareness of how performance compares with that of others in terms of those measures that are made available, and of what ‘good’ might look like.7 This may, in and of itself, help to motivate desirable change by ‘shining a light’ on relevant disparities in relation to features of performance that may otherwise be receiving relatively limited attention (given other prevailing company and company owner priorities).

2. Improving customer, and other stakeholder awareness of the comparisons that are made available. This can increase the scope for customers and other stakeholders to challenge companies, and local governments, on their performance in ways that may create desirable pressures for improvement.

3. Increasing the quality and sophistication of performance comparisons that can be made (which can in turn magnify the impact of (1) and (2)). Important underlying issues here typically include improvements to the development of standardised ways in which information must be compiled and made available. This can have a range of different dimensions, including because:

With more comparative information being made available, and/or information being shared in more accessible and prominent ways, companies can face strong incentives to seek to ensure that comparisons are made on a reasonable basis, in a context where observed performance differences for some measures may relate closely to differences in relevant underlying circumstances (such as the density of the population that different companies serve). That is, a context where there may be greater scope for undesirable inferences to be drawn from available comparative information can result in greater effort being put into refining the basis upon which it is viewed as reasonable to make such comparisons, which can provide a more robust basis for subsequent regulatory assessments. Importantly, it is to be expected that there will be significant divergences of interest between companies in terms of how comparisons are made, because a change in approach that improves the relative performance of one company can be expected to imply worse performance for some others. This can create for a tension between companies that a regulator can seek to use (by providing a forum in which evidence in relation to different approaches can be presented) to try to identify and test which comparison approaches may indeed be most appropriate.

Transparency arrangements typically raise important questions over how potentially complex and extensive information on different aspects of company performance can be communicated in more accessible ways. In line with this, regulators often put considerable effort into the development of standardised and streamlined performance reports that can provide a relatively simple means for customers and other stakeholders to get a high-level view of WSS company performance across some key areas of interest (further comments on how this might be done are included below in the discussion of the Portuguese ERSAR example).

4. Extending the ways and enhancing the effectiveness with which the regulator can seek to use comparative information in its price review determinations, and its associated development of incentive arrangements.

5. Improving customer and other stakeholder awareness and understanding of the trade-offs faced in relation to the sector, and improving the credibility of company and other communications related to those trade-offs (because those communications sit within a broader framework of information provision and challenge). This can provide a basis for better informed and more credible engagement with water customers in ways that can improve the likely acceptability of bill increases where that can be shown to be necessary for the delivery of valued improvements.

It is important to note that the information under discussion here concerns different aspects of the performance of monopoly public service providers. While there is likely to be some relevant performance information that it is appropriate to treat as confidential (for example, for security reasons), experience from other countries clearly shows that substantial levels of performance information can be made available while at the same time taking appropriate account of relevant confidentiality concerns. This is the case even where companies are privately owned (as in England), notwithstanding the potential for this to raise additional types of commercial confidentiality concerns.

Given the public service nature of WSS companies, and the broad range of benefits that can be associated with transparency requirements, there looks to be a strong case for adopting a presumption that the regulator is able to introduce transparency requirements, other than where companies are able to provide compelling reasons as to why that would not be appropriate.

In line with the above comments, there may be significant benefits associated with enhancing the transparency of – and the accessibility of, and prominence given to – WSS company performance information. There is currently a form of ‘traffic light’ approach used in Estonia that provides for public access to some WSS information that can be compared across municipalities.8 However, there looks to be scope to provide for much more effective communication of relative company performance, and – as a result – much sharper reputational incentives, through the development and prominent use of a dedicated set of WSS KPI ‘traffic light' comparisons. As is discussed further below, a key issue here is the extent to which performance comparisons can be viewed as concise, credible and easy to understand from the perspective of customers and other stakeholders, with these features underpinning the force that this form of information provision can have. The current WSS ‘traffic light’ information that is provided sits within a much broader set of municipality information, and while it provides some relevant information that can be compared across municipalities, it does little to inform the relevance of the information that is provided, or to provide confidence that consideration of the WSS information that is provided could be expected to provide reliable basis upon which to draw comparative inferences.

In large part these limitations stem from the inherent difficulties associated with developing benchmarking arrangements in a context where company circumstances can differ materially in a range of ways relevant to service provision. The current information that is provided can be viewed as a useful first step, but much more could be done to seek to improve and refine the set of KPIs that are presented, to develop ways of providing more meaningful benchmarking of performance between companies (including through comparisons within and between different clusters of companies that may share broadly similar operating conditions, at least in some important respects), and to communicate that information in more prominent and easier to understand ways. The intention here is not to say that there is an alternative and readily available better set of KPIs and benchmarking approaches that should be applied and more extensively communicated in place of the current approach, but rather to emphasise the potential benefits of putting policy effort into a developing a process that can be expected to improve the measurement, use and public awareness of relevant KPIs over time. ERSAR provides a useful example of what that kind of process for the enhancement of transparency might look like, and its performance benchmarking arrangements are summarised below.

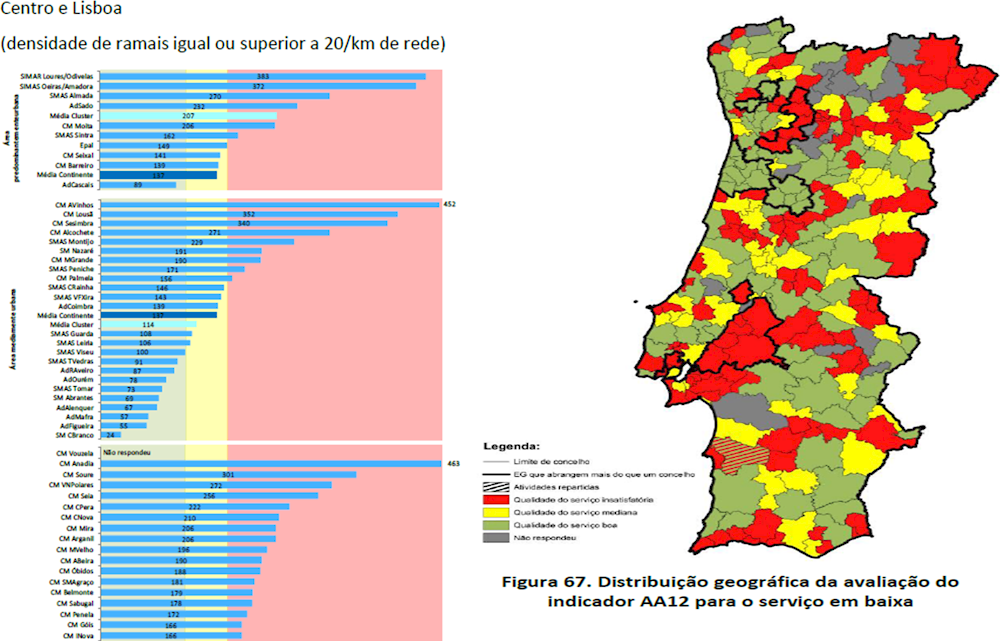

ERSAR as a helpful reference point

The approach to WSS quality of service regulation that has been developed and applied by ERSAR, the Water and Waste Services Regulation Authority in Portugal, looks to be particularly well suited as guide for considering ways in which it may be desirable for the Estonian service performance arrangements to be developed. It is notable, that the ERSAR quality of service arrangements are applied in a context where there are currently 263 water supply utilities, and 266 wastewater management utilities, all state or municipality owned.9 ERSAR has described the goals of its quality of service regulation as being to:

Protect the interests of users regarding the quality of service provided.

Compare results between entities through benchmarking.10

Guide entities towards efficiency and effectiveness; and,

Consolidate a culture of providing information that is: concise, credible and easy to understand.11

These goals look to fit well with the circumstances faced in Estonia, and the approach to quality of service regulation that ERSAR applies – which relies on the development of ‘soft’, reputation-based incentive – could provide a valuable complement to the CA’s current approach to regulating tariff levels, or to a refined version of that included some of the other framework refinement options referred to in this report. While it is notable that regulators in some other jurisdictions (including in England and Wales, and Scotland) have applied financial incentives to service performance metrics, the use of such approaches can generate further risks of unwanted effects arising, and the relatively limited regulatory use that has been made of such metrics to date in Estonia strongly suggests that the consideration of such approaches would be premature at present. In any event, experience strongly suggests reputation-based approaches, focused on the provision of concise, credible and easy to understand comparative information, can have powerful incentive effects.12

ERSAR operates an annual process that involves utilities submitting the required data, that data being validated and treated to provide for benchmarking, and utilities then getting a right of reply before the finalised data is then published and publicised (including through an App). The approach focuses on providing information on around 15 Key Performance Indicators for each service (i.e. water and wastewater), with indicators designed to reflect performance in relation to the protection of user interests, service provision sustainability and environmental sustainability.13 The specific KPIs to be used could, of course, be adapted to the Estonian context where appropriate, and it is notable that data related to many of the broad areas covered by ERSAR KPIs is already collected in Estonia.14

Also, it is notable that many of the KPIs used by ERSAR appear routinely in service performance assessments that are produced in a number of other jurisdictions, including, for example:

Service interruptions (water supply).

Mains failures (water supply).

Water losses (water supply).

Flooding incidents (wastewater).

Sewer collapses (wastewater).

Compliance with discharge permits (wastewater).

A customer complaints metric (water and wastewater).

An affordability metric (water and wastewater).

The notable features of the ERSAR approach, therefore, are less to do with the specific indicators that it provides for collection of (because, as above, it is common for similar types of indicators to be collected in other jurisdictions, including Estonia), and more to do with the processes and approach through which that performance information is presented and communicated in clear, concise and accessible ways. For each performance indicator, companies are ranked and compared with their peers through the use of clusters, based on the different regions in which they operate, and the characteristics of the area (e.g. rural vs urban).15 As can be seen in diagrams below, this is used to provide an easy to understand ‘traffic light’ based presentation of comparisons that allow for straightforward identification of those operators that are best performing, above and below average, and so on. The annual reports allow for comparison between expected and actual performance, and for performance levels to be monitored over time, with this assisting with the prioritisation of improvement opportunities.

Figure 6.1. Extracts from ERSAR service performance information

In line with the comments above, the purpose of highlighting the ERSAR approach here is not to present the specific methodologies that are used for to calculate and compare performance indicators as ones that should be considered for usage in Estonia. Rather, the ERSAR example is intended to provide a useful reference point when considering how WSS performance data can be communicated in ways that can enhance the scope for comparative, reputational pressures to highlight better and worse performing areas, and in doing so to help make more visible where improvements may be both possible and appropriate. The adoption of this kind of approach could be tailored to reflect the relevant circumstances in Estonia (including, for example, in terms of likely data quality), with a range of underlying choices being required in relation to matters including:

The specific KPIs that should be use

How data should be audited

How KPI information should be clustered and otherwise organised and adjusted when benchmarking results are being presented.

In line with the comments on cost assessment above, the most appropriate way to develop the specific performance benchmarking approaches that are to be applied will depend on a range of detailed and context specific matters that go well beyond the scope of this assessment, and is best viewed as something that would be expected to evolve over time. The ERSAR approach looks to provide a helpful reference point when considering the framework and processes within which benchmarking arrangements could be developed and applied. In particular, it focuses attention on trying to make available, and communicate, clear and easy to understand information on comparative performance. With this treated as an appropriate objective, attention can then be turned to the detailed and ongoing work that is likely to be needed to deliver on that. This is not a question of simply seeking to identify what the ‘right’ set of measures and underlying methodologies (e.g. for clustering municipalities) are as a stand-alone exercise. Rather, it is more a question of seeking to develop processes that can be expected to help provide ways of building and refining more appropriate approaches over time, recognising that this is challenging to do.

The challenges arise because there are different dimensions of performance that could be measured and compared in different ways, and decisions in relation to those dimensions and measurement and comparison techniques may imply materially different outcomes in terms of apparent relative performance. This tends to make the process through which methods are developed important, as that process can potentially help give legitimacy to the overall outcomes that result. A commitment to providing clear, concise and easy to understand performance information – one of the high-level goals that ERSAR identifies – is important here, because it makes it clear to stakeholders, including importantly WSS companies, that performance comparisons are going to be made and presented to the public in relatively simplified formats of the kind illustrated above.

Having made such a commitment, it then important to consider the processes through which the specific performance measurement and comparison methods will be determined on. But the context is then one in which all companies know that this kind information will be produced in one form or another, and they know that how they are shown as performing is likely to be affected by the specific methodology choices that are made. Company interests, though, will clearly differ in a range of important ways, as relative assessments will show some as performing well and others poorly by comparison. This difference of interests across companies provides a valuable source of information and input, and the tension it can create between companies can be used by the regulator to try to help improve the robustness and reasonableness of the measures being generated. Importantly, the role of the regulator in this kind of process can be understood as effectively ‘chairing’ a forum/process for the development of the transparency arrangements. That is, the regulator would not be expected to itself seek to identify and specify the set of KPIs to be used, and bases upon which they would be compared, but could instead focus its efforts on trying to promote improvements through encouraging the submission and testing of proposals from companies and other stakeholders. Again, the commitment to producing and publicising the comparative information is key as it can allow attention to focused on more productive questions concerning how that information should be developed, rather than on the question of whether it should be developed, where company interests may be more aligned, in that there may be a general preference for limiting the extent to which there is broader emphasis put on company performance levels.

6.4.2. Incentives to encourage the development of efficiency-enhancing consolidation plans

A number of regulators internationally – including the Essential Services Commission (ESC) in Australia,16 and Ofwat in England and Wales17 - have introduced forms of business plan incentives, typically to try to address concerns that companies may otherwise have an incentive to be unduly conservative in their planning, and to do too little to address the future challenges that are faced. Such approaches can be understood as effectively rewarding early movers for the information they provide in terms of the improvements that their plan presents as achievable. Where the company delivers on that more challenging plan, the outcomes can then form part of future benchmarking efforts that can increase the pressure on other companies to improve, while also providing a practical example of how that improvement may be achievable.

The PREMO framework

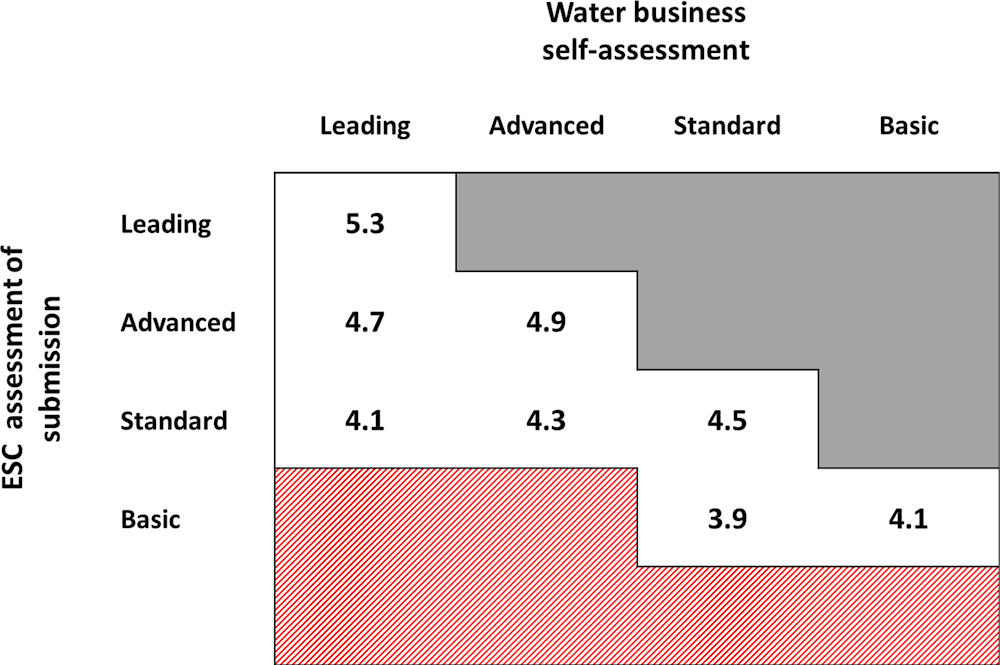

The approach developed by the ESC (the economic regulator of the Victoria water sector in Australia) is referred to as the PREMO18 framework, and provides a useful reference point. Under the PREMO framework, instead of applying a uniform weighted average cost of capital (WACC) across companies, the allowed return on equity is varied depending on the level of ‘ambition’ shown in the relevant company’s price submission. The diagram below illustrates how a higher return on equity is when setting allowed charges where the ESC identifies a plan as more efficient, with four different categories having been identified:

Basic: where the submission is identified as reflecting stagnating or declining performance the allowed return on equity would be set at a level commensurate with the benchmark real cost of debt.

Standard: where a slightly higher return on equity allowance is provided for to reflect that the submission is viewed as a good value proposition for customers but that represents a continuation of existing outcomes and cost efficiency targets.

Advanced: a more ambitious submission that will generally commit to improved outcomes in terms of services, prices or both, and would receive a higher equity return allowance.

Leading: where the proposals place the company as a sector leader on key aspects of performance.

Figure 6.2. Illustration of (real) return on equity allowances under the ESC’s PREMO approach

As can be seen in the diagram, the allowed return on equity is also made dependent on the company’s own assessment of the level of ambition of its plan, with this intended to encourage company’s to put forward their ‘best offer’. In particular, it is notable that - under the approach – a company gets a lower allowed return on equity if ESC judges it as having a lower level of ambition than had been presented in the company’s self-assessment. The ESC identifies the red shaded area as indicating where it reserves the discretion to adopt a different approach, such as setting a shorter control and/or requiring resubmission.

Some core features of business plan quality incentives

The PREMO approach provides an interesting example in part because of the clear and explicit way in which adjusts the return equity allowance depending on assessments of level of ambition. At the same time, it includes levels of complexity (including the use made of company self-assessments) that seem unlikely to be necessary or well suited in the current Estonian context. In practice, this kind of business plan quality incentive approach can be viewed as comprising of three core features:

1. Scope for identifying company business plans as falling into more than one quality category.

2. Identification of the criteria that would be used to determine which quality category a business plan should be identified as in.

3. Explicit and credible up-front identification of how companies will be treated differently when identified as falling in one quality category rather than another.

The following considers how each of these features might be applied in an Estonian WSS context.

Identifying categories of business plan quality

The PREMO approach involves the regulator having to determine which of four ‘quality’ categories a price submission falls into: basic, standard, advanced, leading. Ofwat (the economic regulator in England and Wales) also used four categories – significant scrutiny, slow-track, fast-track, exceptional – in its review of price controls for the 2020-25 period, although in practice only allocated companies to three of those categories (with no business plans categorised as ‘exceptional’). It is notable that in an earlier development of this kind of approach, the British energy regulator Ofgem applied a simpler categorisation that distinguished only between whether companies should treated as ‘fast-track’ - because their proposals had been identified as of ‘high’ quality and therefore appropriate to implement quickly - or ‘slow-track’ – because their proposals had been identified as of relatively lower quality and as requiring further, more detailed scrutiny. The use of four (rather than two) categories in the PREMO and Ofwat approaches can be viewed as a simple refinement of Ofgem’s approach, that allows a further subcategorization of the ‘high’ (fast-track) and ‘lower’ (slow-track) quality categories. It is not obvious, however, that this further refinement would be particularly helpful if such an approach were to be introduced in Estonia, at least in a first iteration. In particular, the use of additional categories increases complexity, and the burden that the regulator (in seeking to specify and apply the categories) and regulated companies (in seeking to understand and determine how to respond to the categories) can be expected to face, but may provide little additional benefit over a simpler two category approach.

Given this, the development of a two-category approach, where companies can explicitly expect more favourable treatment if categorised in the ‘high quality’ rather than in the lower quality category, looks likely to provide the most appropriate starting point for developing this kind of approach in Estonia. That said, there may be a case for explicitly identifying the possibility of using two separate ‘high quality’ categories (with only one lower quality category), if there are some sources of additional benefit – for example, additional support from EU funds – that may be available in some circumstances but not others. Where this is the case, access to the additional support could be made conditional on achieving ‘high quality’ status in the regulator’s business plan assessment, but would then involve some further hurdles having to be overcome.

Criteria for assessing which category a plan should be identified as in

For its review of 2020-25 business plans, Ofwat developed (ahead of company submission of business plans) a relatively extensive assessment framework that highlighted both the ‘test areas’ that were going be explicitly assessed, and what the characteristics of high quality, ambitious and innovative plans would be likely to be in each of those test areas.19 The test areas included a range of core priority matters such as securing costs efficiently, addressing affordability and vulnerability, and securing long-term resilience, and for each test area, Ofwat identified some questions it would be relevant to consider. For example, in relation to securing long-term resilience, the following questions were identified:

How well has the company used the best available evidence to objectively assess and prioritise the diverse range of risks and consequences of disruptions to its systems and services, and engaged effectively with customers on its assessment of these risks and consequences?

How well has the company objectively assessed the full range of mitigation options and selected the solutions that represent the best value for money over the long term, and have support from customers?

For a plan to be viewed as ‘high quality’, Ofwat identified that (among other things): the company will provide clear evidence that they have objectively considered and assessed the full range of resilience management options. For a plan to be viewed as ambitious and innovative, Ofwat identified that the company would need to present strong evidence that it has used robust, ambitious and innovative approaches to assess and mitigate risks to long-term resilience in the round.

Developing this kind of business plan inventive approach in Estonia would not require the extent of development – in terms of assessment criteria and questions - that Ofwat undertook. However, some up-front specification of what the key test areas would be, and what sorts of questions would be expected to guide the assessment in those areas, is likely to be helpful both because it can give greater clarity to companies on what they can expect, but also because the regulator plan and deliver the subsequent assessments (by making it clear what practical steps that is likely to involve). When seeking to specify how companies should be assessed, it can be helpful to distinguish between the following:

Hygiene factors: to what extent are there criteria should be viewed as a necessary condition for any company’s business plan to even be considered as potentially ‘high quality’ (such that the meeting of this criteria can be treated as a form of hygiene factor in the assessment process)? This may include reference to current performance levels and financial health.

Other differentiating factors: given its strategic importance for the Estonian WSS sector, it would be expected that consideration of other differentiating factors would be heavily focused on the extent to which companies are bringing forward new consolidation options, and the extent to which they are able demonstrate, robustly, that those consolidation options can be expected to be efficiency enhancing.

The relevance of different potential forms of consolidation is considered later in this section when some of the potential constraints to consolidation options emerging are considered.

The benefits of a plan being identified as of higher quality

Regulators have typically sought to provide for financial, reputational and procedural incentives to be associated with the identification of a company’s business plan as ‘high quality’ within this kind of assessment framework. In line with this, in Estonia, the development and submission of credible, efficiency enhancing consolidation plans could be encouraged in a number of different ways, including through:

The use of a higher WACC in the tariff setting methodology than would otherwise have been allowed for (as is explicitly provided for in the PREMO approach).

The explicit provision of some other form of financial reward: for example, access to grant funding or preferential borrowing opportunities.

Greater scope for support with respect to financeability using accelerated depreciation (where that can be shown to be consistent with bill affordability and acceptability issues being sufficiently addressed).

Scope for the price control to be determined for a longer period: in line with the comments earlier, this may be important in providing consolidating parties with an opportunity to share in the benefits of the plans they bring forward (particularly where there may be some time lag associated with the securing of those benefits).

Presentation of the outcomes of the assessment in a way that can be expected to provide material reputational benefits for those associated with successful companies: the regulator can actively seek to highlight and publicise its assessments of ‘high quality’ proposals, and then use the companies actions as a positive case study to promote further change.

Procedural benefits associated with less extensive review requirements, providing overall performance remains sufficiently ‘on-track’.

The importance and implications of credibility