This chapter analyses initiatives conducted by the University of São Paulo and the University of São Carlos to support entrepreneurship education, and knowledge transfer. It also studies the connections that the universities have generated with external stakeholders through these activities in the ecosystem of São Paulo, Brazil and beyond.

Innovative and Entrepreneurial Universities in Latin America

7. Case studies in Brazil

Abstract

University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil

Founded in 1934, the university has 5 000 faculty members, 90 000 students, 335 undergraduate and 264 graduate programmes, 42 schools, 4 incubators and 1 Technology Park. It has campuses in seven municipalities in the state of São Paulo, the biggest being the campus of São Paulo, followed by the São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto. The university has a very comprehensive outreach strategy, works with museums, research centres as well as hospitals to conduct research, including the country’s largest health complex Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo.

Entrepreneurship education

Entrepreneurship education varies from school to school. The physics institute does not offer entrepreneurship courses per se, but rather innovation courses at the undergraduate level. In other schools such as engineering, students follow entrepreneurship courses at an early stage. For graduate students, there is an entrepreneurship and innovation master’s programme in São Paulo and 25 different courses covering innovation and entrepreneurship.

The “residência em inovação” is a new programme for graduate students, akin to an internship through which students will benefit from mentoring and a place to work at the INOVA.USP Centre for Innovation, an arm of the innovation agency that aims to attract companies and investors. This programme has just started but is expected to be a success.

Connection with the ecosystem generated by entrepreneurship education

The university has four incubators, all in the state of São Paulo, with two in the city, Habits and Cytec. The university is an innovation hub as the number of companies incubated is quite high: 576, as well as 1 934 “DNA USP companies” (companies created by students) and seven unicorns created by former students.

The university also has a science and technology park that, unlike the incubator, is more generic and devoted to agri-business. Its aim is to create a strong ecosystem for students to connect with firms from the agri-business sector and develop their entrepreneurial ventures. The university does not run an acceleration programme but is now establishing a tighter relationship with investors for start-ups to have more support to scale up. There is also the innovation centre of the University of São Paulo (INNOVA.USP) that gathers all research activities throughout the university and fosters collaborative activities. Hackathons are organised by student associations and are supported by the innovation agency on annual basis (100 students).

Other initiatives include:

A conference for science-based start-ups: the last edition was held last June, and 77 technologies were presented to investors.

A pre-incubation programme in partnership with FAPESP, a public research agency of the state of São Paulo (before going to the incubator – six months to develop project funded by FAPESP through the Programa de Innovación Tecnológica en Pequeñas Empresas (PIPE) “Novos negocios N2”: 14 editions of this initiative; more 400 students; 90 start-ups in 30 countries.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship education

The impact of the pandemic was strong, courses shifted online, with success since many more students are taking courses. Three hundred students now attend the entrepreneurship courses.

Remaining challenges related to entrepreneurship education

The university had to create infra-legal norms for faculty members to create their own start-up or to licence a technology (as public employees are not allowed to do so). There is progress to be made as the legislation needs to further clarify the status of academics who both own a start-up and teach (to avoid conflict of interest).

Knowledge transfer strategy

The USP’s mission is to “promote knowledge through teaching and research, and to extend to social services that are linked to knowledge and teaching” (University of São Paulo, 2022[1]). The university also specifies its commitment to supporting “social, technical, and green innovation” through the sharing of knowledge, embedding knowledge transfer as a fundamental component of its teaching and research activities (University of São Paulo, 2022[1]).

The university has recently put in place an innovation policy (in December 2021) and is working to create a set of institutional incentives for professors to conduct more transfer activities. In addition, the USP is currently undergoing a change in administration, with the election of a new hierarchy with a new vice-rector of research. As such, the new administration wants to develop the social impact of innovation.

The agency INNOVA.USP is at the heart of the university’s knowledge transfer strategy. It was created four years ago in 2018 and is mandated to reach out to the private sector and be the recipient of private sector demands (from big companies and small- and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs]). In addition, the Department of Collaboration (departamentos de convenios), created in 2021, keeps track of all agreements signed by the university with external partners and is home to the university’s technology transfer office (TTO). There are also TTOs on the campuses of Piracicaba, Ribeirão Preto and São Carlos.

Connection with the ecosystem driven by knowledge transfer activities

The USP has four incubators in three different cities and in two of them; the institution has agreements with the city hall to promote the development of start-ups through the creation of science parks. In Ribeirão Preto, the USP campus has already set up a technological park (in a consortium with the city hall) and in the city (Piracicaba), the USP campus intends to have the technological park consolidated by the end of 2022.

The USP works with any company interested in innovation, particularly in the areas of energy, biotechnology and construction. For example, the USP has signed an agreement with the Brazilian Portland Cement Association (ABCP). The agreement is managed by the School of Engineering (Escola Politécnica) on the USP side and focuses on improving construction technologies. Since the ABCP is an association of industries, developments are dispersed throughout the industrial community. The USP also works with the Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo (FIESP) in a programme to improve SMEs but the lack of innovation culture in those companies is a problem most difficult to overcome.

The USP collaborates with the federal government to support knowledge transfer, particularly with the Brazilian Company of Research and Industrial Innovation (EMBRAPII), which has seven units within the USP, through which the universities conclude agreements with the companies on a specific subject.

Another form of collaboration includes industry involvement in education. In some business or engineering disciplines, business or industry representatives frequently give lectures and students work in industrial plant to develop activities. In some of the entrepreneurship courses, students are grouped into teams to develop and present a business plan and are given mentors from the business or venture capital community who participate in the final evaluation (and mentor the teams during the development of the project).

The USP is also making sure that the students benefit from their collaboration strategy. The university has developed a collaboration with FEA Angels (a network of former students of the Faculty of Business and Administration, created to foster entrepreneurship by mentoring and funding) and gathered 130 mentors to help the start-ups in the university’s incubators. As another example, construction company Tegra Incorporadora is supporting students developing start-ups in the construction business.

The USP is also drafting an “investment policy” to allow the university to invest in spin-offs to not only foster entrepreneurship but also improve knowledge exchange. For the start-ups to succeed, the help of mentors and venture capital is crucial.

Incentives for staff to engage in knowledge transfer activities

The USP is working to develop a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship as part of both teaching and research activities, through its innovation policy approved last year.

The university also recommends that innovation and entrepreneurship activities be valued for career advancement evaluations of faculty and technical and administrative staff (University of São Paulo, 2022[1]).

The document states that the USP will offer a new set of institutional incentives for its staff to develop innovation activities:

Scholarships to students (undergraduate or graduate) and post-doctoral fellows.

Awards to students, post-doctoral fellows, professors, technical and administrative personnel, collaborating researchers and spin-off companies.

Innovation grants for professors, technical and administrative workers, post-doctoral students, undergraduate and postgraduate students, and collaborating researchers to conduct research and development (R&D) projects developed in collaboration with for-profit or non-profit entities.

The university will also put a framework in place so that innovation and entrepreneurship activities are appraised in career advancement evaluations of faculty and technical and administrative staff (University of São Paulo, 2022[1]).

Remaining challenges related to knowledge transfer activities

As mentioned by other public universities, and as is the case of the USP, there is a barrier to the creation of start-ups and spin-offs by faculty members as it raises legal issues. Professors and university staff have a professional contract, which implies full commitment to university work, and, as such, they cannot dedicate any working time to developing other activities such as managing a start-up. The university should set up clear rules that allow professors to develop such activities as part of their professional responsibilities, as at present, professors (as the case in many countries) are bypassing the rule and starting their own business but in someone else’s name (a spouse or a family member).

Universities are a part of the innovative process, fundamental research is the basis of innovation, and the university should be ready to answer the demand (legal framework). There are still hurdles that hamper business-industry partnerships. As a large, long-standing university, the USP’s internal procedures to set up a partnership agreement with a company are lengthy and require many steps, which are perceived as an obstacle by the private sector. The Brazilian fiscal system is also time-consuming: companies spend a lot of time completing administrative procedures to pay taxes, which is a big problem for an SME or a young company.

Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), Brazil

The Federal University of São Paulo was created in 1968 and was the first higher education institution (HEI) to have settled in São Carlos in the state of São Paulo. It now has four campuses: Araras, Lagão do Sino, São Carlos and Sorocaba and more than 20 000 students. Twenty disciplines are related to the subject of innovation and entrepreneurship. The university’s main campus (city of São Carlos) benefits from a vibrant ecosystem: the University of São Paulo also has a campus there and 20% of the population is involved in academic activities. The university created the first incubator in Latin America and is supported by entrepreneurs, and federal and state agencies.

Entrepreneurship education

There are mandatory classes in entrepreneurship for engineering students. Undergraduate students of physics, chemistry, education and psychology have elective disciplines on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is taught transversally and students from different faculties can take these courses.

At the graduate level, the university has a special programme, ITI UFSCar, resulting from a partnership with the business sector and international researchers to offer students’ academic training that integrates the markets’ perspective. The programme has a Master in Business Administration (MBA) in Information Technology and Innovation.

The university also has a Master in Business Innovation (MBI) that was created six years ago by a professor who attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The MBI is focused on the entrepreneur’s human abilities (design thinking model, focused on business model creation).

In addition, all PhDs in innovation (which are partly co-financed by companies) have mandatory training on leadership and soft skills developed in partnership with EMBRAPII.

Connection with the ecosystem driven by entrepreneurship education

The university has issued 300 patents and 20 license agreements working on innovations such as the genetic modification of sugar cane. The university has received around BRL 6 million in royalties from intellectual property (IP) development in the period 2017-20. Its Innovation Agency is responsible for co‑ordinating activities and training to promote the culture of innovation and entrepreneurship within the university. The agency has also started registering companies founded by the university’s students, staff and researchers, created an innovation search portal and a Doctorate in Innovation. It is also in charge of IP transfers and thus operates as a sort of TTO. The agency produces a report on its annual activities (Relatório de Atividades da Agência de Inovação da UFSCar), tracking all activities it carries out, as well as key performance indicators on its knowledge transfer activities (number of patents, licence agreements).

The agency also conducts innovation challenges every year and problem-solving activities with companies, such as the “bike bus challenge”. The university has three technological parks and an innovation lab. There is an ecosystem surrounding the university with several FabLabs and several makers’ spaces.

Other activities within the community include:

Several extension activities, workshops for all levels of education, a young scientist programme as an initiation to science, as well as a programme called “small citizen”: food, clothing and robotics, science lessons and a partnership with several science museums (astronomical observatory). The university’s community library is a space to meet and exchange and is heavily used by the community.

A good relationship with the universities of São Paulo and Campinas, with an exchange of PhD students and graduate students.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship education

During the pandemic, all activities were carried out remotely, including lectures and lessons. The pandemic had a negative impact on student engagement: human interaction fosters innovation and entrepreneurship; hence, students were a little demotivated, giving up courses and reporting feelings of depression with a clear loss of engagement that impacted entrepreneurship education.

Remaining challenges related to entrepreneurship education

There are challenges regarding IP development, as one-third of the profit goes to the university and another third to the inventors. Regarding the involvement of professors in companies, the law authorises professors to be partners in companies: they can help students create a company but cannot be involved in it. Brazilian law is very complicated: the innovation law was revisited in 2018 but many universities are applying their own rules. Another issue is bureaucratic procedures for TTOs for patent development.

Knowledge transfer strategy

As stated in the most recent institutional development plan (2018-22), the university’s expansion into the state of São Paulo has enabled the institution to train researchers and local professionals, produce research and expand the dissemination of “knowledge, culture and art” (Ministry of Education/UFSCar, 2021[2]). The university has intensified its dialogue with society and all its teaching, research and transfer activities are articulated to respond to the social demands of the regions where the campuses are located. Knowledge transfer is as important as teaching and research and the university aims to make knowledge accessible. As stated in the UFSCar plan, “the university mission is to develop, teach and disseminate Science and Technology for free” and for that, the university is in permanent dialogue with different segments of society (Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), 2022[3]) . It receives its main funding from the federal government, through its annual federal law.

Connection with the ecosystem driven by knowledge transfer activities

The university has created links with several industries to provide teaching, research and extension activities. In the city of São Carlos, the university benefits from a rich ecosystem, as the city counts on the presence of other HEIs (such as the São Carlos School of Engineering) and Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) units. The city is an important technological and educational centre.

A salient feature of the university has been its ability to connect with actors in the ecosystem, which are not producers of high-technology goods or services but are at the heart of the country’s productive sector. It especially interacts with the food and agriculture industry (companies such as Magnesita), the metallurgic and mining sector (Alcao, CBMM, CSN, Vale), pulp and plastics (Surazo, Vetra), the oil industry (Petrobras) but also sugar and alcohol plants. It also works with other universities (University of São Paulo) and science parks (Parqtec).

As stated previously, the innovation agency has been a fundamental pillar of this knowledge transfer strategy as it deals with issues related to the protection of IP rights arising from research developed in house and any issues related to technology transfer. It also pays attention to connecting the dots within the university, trying to make students from different academic orientations connect and conduct research together.

The university is also invested in contributing to cultural activities and social projects, with a dedicated culture co‑ordination office, responsible for the university’s transfer activities related to the art and culture, carried out in partnership with external stakeholders. The university recently worked with the municipality of São Carlos, the University of São Paulo and a local NGO to organise a virtual music festival in memory of a local violinist (USP, 2021[4]).

The university has also contributed to supporting SMEs in partnership with the federal and state government. EMBRAPII, a federal agency that supports industrial innovation, has offices in UFSCar to develop research projects with local companies and SMEs in particular. EMBRAPII has a programme of innovation in small enterprises, with funding to create a new product or service. The São Paulo Research Foundation also has a programme to support innovation in SMEs Pesquisa Inovativa em Pequenas Empresas (PIPE). Often, SMEs are not aware of these programmes and the university plays an important role in presenting these programmes to local companies.

A major milestone achieved by UFSCar is that it has contributed to making the city of São Carlos an attractive city for graduates to stay after their studies. The city has suffered from brain drain in the past, with graduates with a high level of studies (often PhDs) leaving for other cities or countries. The university has doubled its efforts to build partnerships with companies and SMEs to disseminate knowledge and transfer. It has also increased the offer of courses in partnership with the industry, such as data science courses (in partnership with Santander), inviting professors from the industry to teach. As a result, their highly skilled graduates were more able to find a job suited to their qualifications or create their own venture.

The university sets its strategic plans in a very collegial manner, involving students and community members. The new development plan of the university sets extension and interaction with society as strategic priorities, in addition to inclusion and diversity (several grants are offered to students, which includes rent payment).

Incentives for staff to engage in knowledge transfer activities

UFSCar’s innovation policy also establishes that any internal personnel, professors, students and technical and administrative staff who contribute to the development of any IP that is licensed are rewarded with part of the royalties obtained from the license, according to their intellectual contribution to the invention. Usually, one-third of the royalties obtained go to the investor and the proceeds are allocated to the university and innovation agency. Furthermore, there are optional measures in place allowing UFSCar community members to receive resources in the form of scholarships, from projects funded by companies and other external institutions. UFSCar also invests in training for professors: for instance, it has developed a course on the use of digital information communication technology (TDIC). The university also encourages professors to undertake post-doctoral studies abroad, a way to incentivise training.

Remaining challenges related to knowledge transfer activities

Stakeholders during the interview reported that there is only one lawyer for the whole university (comprising four campuses); legal support for IP development is therefore limited. The contracts issued by the TTO need a number of months to be signed off by the legal officer. All projects that are financed by the government take time to put in place. The bureaucracy, as in many other countries, is a real barrier to knowledge transfer, whereby to access grants and state funding for research projects depends on the submission of a vast amount of paperwork. There is also a problem of reputation, as the university is often perceived as being bureaucratic by external stakeholders and companies in particular.

Ecosystem analysis of São Paulo and the role of the UFSCar and USP

As evidenced by the analysis carried by Global Ecosystem Dynamics, in collaboration with MIT D-Lab and supported by Santander Universidades on the innovation-driven entrepreneurial economic ecosystems of São Paulo, the UFSCar and USP play a role in it.

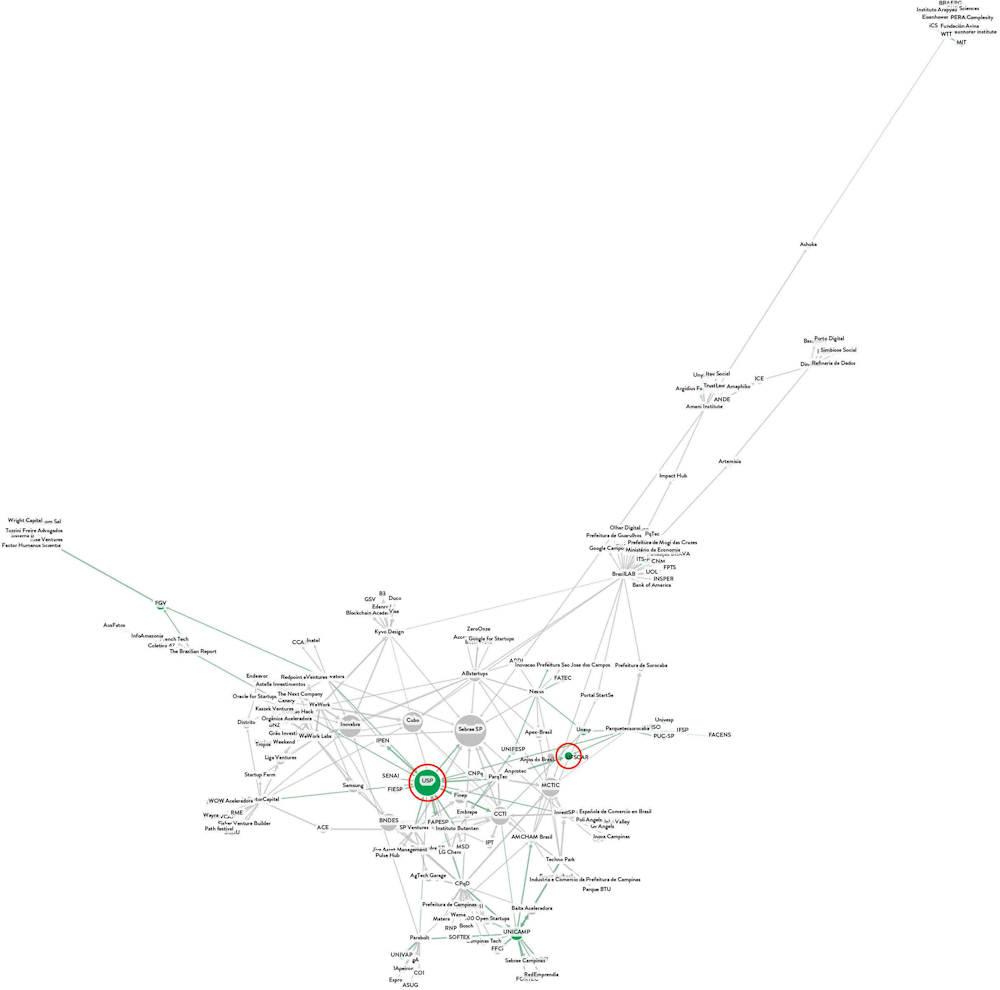

Figure 7.1. Ecosystem analysis of São Paulo and the role of the UFSCar and USP

Note: This figure provides a visualisation of the collaborations between actors of the economic ecosystem of São Paulo with a node size dependent on the number of mentions by other participants and the strength of said mentions (weighted in degree), highlighting in blue the universities categorised as Enablers, those focusing primarily on education and capacity building, and in green the universities categorised as Knowledge Generators, those focusing primarily on research and the development of new technologies. These visualisations, along with the interpretation of each node’s centrality metrics, allow for the analysis of the positioning of universities mentioned within their innovation-driven entrepreneurial economic ecosystem.

There could be a dissonance between what the university sees as its presence in the ecosystem and what this independent mapping exercise finds. Data collection for each ecosystem was conducted by first identifying as many actors as possible through desk research, which were in turn invited to attend a workshop on strengthening innovation-driven entrepreneurial economic ecosystems and fill an online survey regarding their social dynamics with other actors.

Source: (Tedesco, 2022[5])

In São Paulo’s ecosystem, seventeen universities were identified (Tedesco, 2022[5]). Of these, thirteen are knowledge generators and four enablers. It highlights that only the USP has a relevant positioning as a gravitational centre, having been mentioned by eleven actors from the total study participants.

On the other hand, UFSCar does not appear as a relevant actor from the point of view of ecosystem participants. Although the UFSCar was not part of the participating actors, this does not affect its weight and influence in the ecosystem, since the mathematical models and metrics represent the perspective of all participating actors of the ecosystem and not their own perspective.

References

[3] Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) (2022), University Status, https://www.soc.ufscar.br/arquivos/regimentos/estatutoufscar_alterado.pdf.

[2] Ministry of Education/UFSCar (2021), Institutional Development Plan (2018-2022), Ministry of Education of Brazil/Federal University of São Carlos.

[5] Tedesco, M. (2022), “How and why to study collaboration at the level of economic ecosystems”, D-Lab Working Papers: NDIR, MIT D-Lab.

[6] University of São Paulo (2022), Normas da Universidade de São Paulo, https://leginf.usp.br/?resolucao=consolidada-resolucao-no-3461-de-7-de-outubro-de-1988#t1.

[1] University of São Paulo (2022), University of São Paulo - Norms, University of São Paulo, Brazil, http://leginf.usp.br/?resolucao=resolucao-no-8152-de-02-de-dezembro-de-2021.

[4] USP (2021), ““Chorando Sem Parar” tera 12 horas de musica em ritmo de choro”, Jornal da USP, pp. University of São Paulo, Brazil.