Collaborating with external stakeholders to support innovation is gaining momentum in selected universities. Many HEIs have adopted a comprehensive knowledge transfer strategy ranging from consulting services for companies, applied research to life-long learning activities or services to surrounding communities. Next universities should look to build capacity to scale-up these activities.

Innovative and Entrepreneurial Universities in Latin America

3. Knowledge exchange and collaboration

Abstract

Across OECD economies, higher education institutions (HEIs) are experiencing a shift in their knowledge exchange activities from a narrow technology transfer perspective towards a much wider one that includes different forms of knowledge exchange. European and North American HEIs have been promoting and implementing a somewhat standardised model of technology transfer, resulting from years of common benchmarking and catering to international standards. With the consolidation of the knowledge economy, many of these are now revisiting their view of the role of HEIs in society and embarking on a transition. HEIs become agents of change beyond that of human capital formation and technology transfer, evolving into promoters of human interaction, social guidance and key facilitators of knowledge exchange and applied knowledge optimisation throughout society (Harrison and Turok, 2017[1]).

To guide such a transition, many OECD-based HEIs can benefit from the experiences of their Latin American counterparts. The wide variety of institutional contexts, including academic, legislative, historic and cultural differences across Latin American HEIs, together with the lesser weight of international standardisation, has led to the implementation of a rich diversity of knowledge exchange trajectories across HEIs in Latin America. As compared to many other OECD contexts that have chosen to standardise HEI knowledge exchange around similar notions and methods, the richness in the diversity of knowledge exchange in Latin America offers many alternatives and experiences that can inspire future development. In addition, many universities in the region have to deal with a less mature innovation system (with less public and private spending on research and development [R&D]) that directly influences their ability to patent or license technology.

This chapter presents the variety of knowledge exchange in Latin America, highlights the experiences, obstacles and alternative approaches to knowledge exchange and comments on the lessons to be learnt from the study of 11 Latin American HEIs.

Beyond technology transfer: Universities in the region have adopted a comprehensive knowledge exchange strategy

With the consolidation of knowledge over the last half-century as a primary factor of production (Romer, 1986[2]) and key aspects of social and economic development, the role of HEIs as generators and disseminators of knowledge has placed them at the forefront of many development strategies.

Although consensus is building around the principles of wider knowledge exchange for HEIs, the specifics of how HEIs can transition and implement measures in support of this new way of knowledge exchange are still undefined. As such, the richness of experiences coming from the Latin American HEIs analysed as part of this study offers many clues as to the multiplicity of approaches that can be used but also the obstacles that can hamper such efforts. Most institutions in this study generally implement the same general knowledge exchange axis that can also be found in HEIs throughout OECD countries: licensing, extension and entrepreneurship. However, the knowledge that is exchanged, the motivation stimulating this exchange, the partners involved in the exchange and the methods used to exchange this knowledge are varied and rich in lessons to be learnt. From Chile’s Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (PUC), which has a relatively orthodox but effective technology transfer structure and method; to Argentina’s Siglo 21 Business University (Siglo 21), where knowledge generation is strictly contextualised to include and cater to local specificities so that the HEI is the bridge between technology and the people; to Mexico’s Anahuac University, which has become a key player in the local “social transformation” of the economy as a result of the long-standing humanistic character present in all aspects of the university; to the Technological University of Uruguay (UTEC) that is dedicated to playing a role in changing the technology averse culture of the local ecosystem and convincing policy makers of the importance of investing in technological capacity building. The HEI cases under study all have different dominant approaches to knowledge exchange that differentiates them from the rest. Some of this differentiation will be highlighted in the remaining pages of this chapter.

Understanding knowledge exchange practices in selected case studies

Extension services

Most traditional knowledge exchange efforts undertaken by HEIs are unidirectional and are meant to get knowledge generated within the HEI out to society. As such, research publications are a method of transferring knowledge that is mostly unidirectional and typically only accessible to other academic practitioners. Teaching is also unidirectional in nature and, although it may have a somewhat wider potential audience of students, it remains limited in its transfer to core knowledge for undergraduate studies and rarely includes cutting-edge knowledge except in specialised or graduate pedagogy.

As explained in the first section of this chapter, greater volumes of advanced knowledge must reach society if the economic benefits of a Romer-style knowledge-based economy are to take hold (Romer, 1986[2]). This is one of the motivations that have led HEI institutions, encouraged by policy makers, to give much more priority to the promotion of technology transfer. The objective then became to push technology out of the HEI’s labs and off researchers’ desks into the economy.

Contrary to what happens in many OECD countries, the patenting and licensing of technologies produced by HEI labs are the exception rather than the norm in many of the Latin American universities studied. The institutional frameworks, formal rules and informal norms, that influence many Latin American universities, especially public ones, place significant constraints on the effective transfer of knowledge through patents and licensing agreements. This has made the entrepreneurial path a much more attractive alternative for “pushing” university-produced technologies and knowledge into the economy. Although knowledge transfer is happening through licensing agreements, with such licensing helping to diversify the revenue stream of much larger private HEIs such as the Tecnológico de Monterrey and Adolfo Ibáñez University (UAI), this is viewed as a much more complicated method of transfer than through university-backed start-ups. Additionally, whereas existing businesses need to adapt themselves to be able to incorporate effectively new knowledge and technology, the clean slate that entrepreneurial ventures offer makes them well suited to exploit commercially university-produced knowledge and innovations.

Although the entrepreneurial path for the transfer of technology is a valid method for HEIs to use when they prioritise new start-ups, they are excluding existing businesses as recipients of HEI-produced knowledge. Existing businesses must adapt to integrate new knowledge but are often better equipped in terms of market penetration, resources and capabilities to be able to optimise the implementation of the transferred knowledge. There is, then, a balance to be struck between reaping the potential social benefits of preserving employment and market stability through improving the competitiveness of existing businesses because of university-supplied technology transfers and capturing the efficiency of start-up-based transfers. Especially since new venture creation will tend to add output capacity and, therefore, competitive intensity in the market.

Hence, HEIs favouring the entrepreneurial path for the transfer of their technology should also develop an active extension service that connects and exchanges knowledge with the existing business community. For instance, although Colombia’s ICESI University is renowned for its entrepreneurship support, it has also developed very good connections with the local business community, which it uses to transfer research results and university-produced knowledge. The key is to attempt to unify both existing businesses and new ventures within the same networks and promotion efforts.

Entrepreneurship education as a means to support technology transfer

Not all entrepreneurship promotion done by HEIs is carried out with the purpose of knowledge and technology transfer. In fact, as set out in the previous chapter, much of entrepreneurship education and promotion by universities is based on capacity building and skills development. HEIs, such as Anahuac University, promote the entrepreneurial initiatives of students with internal and external business incubators and accelerators, but these initiatives are not necessarily exploiting university-developed technologies as the basis of their ventures. It can be argued in these cases that the knowledge transferred mostly comes from the entrepreneurship support technicians offer and therefore transfer their expertise over to these novice entrepreneurs. Colombia’s ICESI has developed a good reputation for its expertise in entrepreneurship support, which it offers to both the university’s students and faculty who want to initiate their own entrepreneurial ventures, irrespective of whether these ventures are based on opportunities from research results or not.

In order to increase the technology transfer outcome of their entrepreneurship support, some HEIs are specifically aiming their entrepreneurship promotion toward their faculty members and researchers. This often takes the form of training in business and entrepreneurship skills offered to faculty. ICESI has offered business and entrepreneurial training for its researchers but these courses are not always popular as researchers are not always attracted to entrepreneurial careers. Nevertheless, increasing business and entrepreneurial knowledge has been observed by HEIs such as Argentina’s S21 to go a long way in helping researchers to better understand and adapt their outputs to business needs, further facilitating its potential for transfer (more on this in the following section). Researchers at Anahuac University were originally found to have little interest in promoting entrepreneurial initiatives. This was in large part the vestige of past stereotypes existing in many OECD countries when it was once ill-viewed to personally benefit from the fruits of institutional research. However, a change in attitude at Anahuac University came about when researchers were put in charge of the incubation activities and entrepreneurship promotion. Greater involvement led to greater understanding and, subsequently, more interest.

An HEI that has been orienting part of its entrepreneurship promotion towards its faculty is USFCar. They observed how the conventional wisdom that academics are entrepreneurially averse is largely false in their case by witnessing increasing interest on the part of their faculty for the many training and venturing opportunities offered to their faculty members. The younger generations of researchers were especially likely to take advantage of these measures.

Another technique historically used to increase the technology transferred through the entrepreneurship support measures promoted by the HEIs is to focus these measures on populations and academic disciplines that are more likely to generate applied and transferable knowledge. For example, the PUC in Chile has developed and implemented a very entrepreneurship-oriented technology transfer strategy largely focused on its engineering school. The many innovations coming out of this school are commercialised through entrepreneurial ventures promoted by students and faculty, but also by external entrepreneurs.

Leveraging on interdisciplinary approaches

The interdisciplinary nature of technology and knowledge exchanges enriches the quality of its impact (Feng, Liu and Wang, 2022[3]). A more holistic involvement of all knowledge-generating departments of HEIs is a way to ensure not only that a greater proportion of the generated knowledge will reach society but also that a wider spectrum of knowledge and greater scope of beneficiaries from this knowledge can be reached. Historically, innovation and knowledge transfer efforts at the UAI were concentrated on the faculty of engineering. However, recent and ongoing reforms are working to spread these efforts across all areas of the university.

However, the key factor is not so much getting all departments individually involved in technology transfer activities. Rather the cross-disciplinary nature of the transfer efforts is what is often likely to have the greatest impact, as many sources of conceptual knowledge on their own carry very little commercial applicability warranting any transfer demand. Yet, when different disciplines and sources of knowledge are fused together around a coherent theme, their full potential and applicability can be realised. This cross-disciplinary collaboration, however, goes against the structure and culture of most HEIs.

In order to apply a more multidisciplinary technology transfer strategy, many HEIs have had to break down countless cultural “walls” within their organisation. Efforts taken by ICESI to try to introduce greater cross-disciplinarity within knowledge exchange initiatives have proven very difficult to implement and are not very popular amongst their own research community. Similar efforts carried out by the UFSCar, however, showed that despite initially being very difficult to get the different academic areas to communicate, with time, students and younger researchers took over the informal lead of these efforts, which made collaboration and exchange across disciplines at the university much easier.

A knowledge transfer strategy for multi-campus universities

Over recent decades the missions and activities of HEIs have become more complex and diversified. This is a general trend observed both in OECD countries and worldwide. The scope of higher education has become increasingly globalised, in both its influence and its markets. Many HEIs, both public and private, have seen significant changes in their sources of funding, often within a pressured budgetary context, leading many to search for improved economic performance. Simultaneously, HEIs have experienced greater levels of autonomy. As a result, HEIs across the world have been developing new organisational structures and formats, leading many smaller institutions to fuse and merge in attempts to gain greater market coverage, offer more diversified study options, reach critical masses and greater efficiency. Many others have internationalised by establishing satellite campuses in new countries, either on their own or through collaboration agreements, in order both to gain access to new promising student markets and be able to offer their existing students a differentiated offer of international study destinations.

The result is an often complex multi-campus structure which can be challenging from an administrative perspective. The novelty of this phenomenon in many OECD member countries means that there is a lack of clear guidelines and benchmarks upon which HEI administrations can adapt and build upon. This is especially apparent within the knowledge exchange strategies and policies of multi-campus HEIs. Indeed HEIs face the paradox between the proximity benefits of implementing a decentralised knowledge exchange strategy with a strong smart specialisation focus in each one of the individual campuses or the efficiency and control benefits of implementing a centralised knowledge exchange strategy that follows systematic procedures that offer a more holistic overview of the entire internal HEI system.

The study of Latin American HEIs and the many different approaches that they have turned to in the face of this multi-campus knowledge exchange policy paradox can offer important lessons for OECD HEIs. An exemplar that has had to confront this paradox much before it became an issue for most OECD HEIs is the Tecnológico de Monterrey (TEC). The institute is a huge university system that serves over 94 000 students across 29 different campuses in Mexico and 18 international branches and offices (TEC, n.d.[4]). There once was a much greater level of independence and intercampus competition. Now the culture has shifted to an organisational philosophy that “there is only one TEC”. In terms of structure for knowledge transfer, TEC implements a hybrid structure, which blends centralisation approaches in areas requiring consistency, and local differentiation, particularly in terms of relational capital building and adaptation. The university has a centralised offer throughout the TEC system, with the same general programmes. Programme design and administration are centralised but with a degree of local adaptation, that takes advantage of regional experts and capabilities. The knowledge exchange officers on each campus are encouraged to actively network with local players and agents such as local chambers of commerce, technological parks, incubators and accelerators to create proximity and establish a working relationship at the campus level. This way, TEC aims to better exploit the “potentialities” of each region. Notably, the talent management functions remain centralised mainly to maintain greater consistency and control.

The University of São Paulo (USP) is another of the largest HEI systems in Latin America (over 99 000 students) with one of the largest number of doctoral graduates in the world.1 It has a main campus but also counts on a network of 11 different satellite campuses. The USP is largely decentralised across campuses, with the exception of a number of unified official agreements and legal elements. Official technology transfer offices have recently been opened in all the USP’s academic departments. Prior to that, the centralised transfer agency which existed was not an active internal actor within the USP. The expectation is that the creation of the network of transfer offices will not only decentralise the universities’ knowledge exchange functions but will also facilitate engagement. From industry’s point of view, the decentralisation of the USP’s transfer offices facilitates accessibility and finding a local contact point to engage with. For its part, although the UFSCar agrees that greater decentralisation of its knowledge exchange function may be preferable, it stresses that the complexity of regulations and legal red tape forces it to maintain the centralisation of administrative function within its multi-campus system.

In contrast, the management of knowledge exchange at the PUC is centrally co‑ordinated for all faculties. All rules and procedures are unified. The structures of the knowledge transfer “units” are sometimes different across faculties but they connect in terms of policies. Each faculty has an innovation centre that acts as an umbrella organisation overseeing all transfer activities, which are centrally controlled. The Pontifical Xavierian University (Javeriana) in Colombia takes a different approach, whereby the internal knowledge exchange dynamics across campuses are centred on collaboration and balance, with some healthy competition over resources. Because of the strong smart specialisation focus implemented, which aims to focus resources on areas of competitive advantage, certain faculties sometimes feel left out. However, there is an increasing number of transversal cross-campus projects; the competition is therefore not across campuses but rather across researchers.

An interesting approach to multi-campus knowledge exchange policy and structure is implemented at UTEC. UTEC has 11 campuses that are geographically spread across Uruguay. They are a relatively small university system with just under 4 000 full-time students but are experiencing strong growth (UTEC, n.d.[5]). It has a central council with multi-campus participation; however, the management of each campus is decentralised. The UTEC system is not centralised, nor is it localised: it is networked. Intercampus collaborations are often required due to a need for critical mass. The advantage of such a networked structure is that there is a constant flow of resources and capabilities across the intercampus network. The disadvantage is that it is often difficult for actors to access and retain the added value generated by such a structure. The university has very strong links to the private sector leading them to be able to capitalise on the significant intercampus differences in order to capture the contrasts across the territory and ecosystem of each campus. Despite this independence, there are common indicators and goals set to help control and monitor the system. UTEC’s networked model, however, is not easily scalable. There is increasing use of digital platforms for cross-campus co‑ordination. These platforms help to align the actions of each campus. Uruguay has good digital connection capabilities, which contribute to the effectiveness of these platforms. These digital platforms were developed by the Centre for Digital Transformation with the assistance of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s Data Science Department.

Incentives systems implemented by case study universities to support knowledge transfer

Together with the bottom-up forces motivating institutional change, HEIs can also stimulate greater participation and collaboration of staff and faculty in technology transfer initiatives by reforming their evaluation and incentive policies. When the UAI embarked on reforms to transition toward transferable applied research, they triggered internal change by remodelling their academic evaluation criteria, in an effort to move from being “teaching-focused” to “research-focused”. The new evaluation criteria for professors/researchers at the university include extension services, which compensate and incentivise the consultancy and applied research contracts that professors can generate for the HEI. Professors then have a choice between which tracks they prefer to be evaluated upon research, teaching, extension or a mix.

However, in many instances, internal policy or external regulation inhibits HEI researchers from retaining property rights over the knowledge and technologies that they help generate. This tends to act as an important disincentive to the generation of transferable knowledge. In universities such as Anahuac University and ICESI, researchers are found to have little incentive for technology transfer activities and, as a result, are not necessarily oriented towards the business applications of their research.

To help to counter this, researchers at the Javeriana are incentivised based on three factors: publications, spin-offs and created intellectual property (patents). The university has found that establishing patent-based incentives based on a percentage of the revenues generated from the commercialisation of their innovations has been effective in aligning academic production with business needs. Bonuses on patents therefore depend not only on whether these are registered but on whether private demand emerges and effective transfer takes place. To facilitate this, researchers at the Javeriana are incentivised to be involved and participate in the entire transfer process.

The perspective adopted by Tecnológico de Monterrey in order to cater to the multiple roles of professors at the university was to develop four different faculty types: teaching, research, entrepreneurial and extension professors. Whereas the evaluation of teaching professors is mostly based on class hours and teaching evaluations, they are encouraged to be active in external “in-company” training. Research professors are evaluated according to their publications and production of intellectual property (IP). The utility of the patents created is taken into consideration with patents having commercial potential being prioritised. The entrepreneurial professor is a new figure at Tecnológico de Monterrey, meant to cater to those professors who want to exploit institute-generated knowledge through entrepreneurship. This category of professorship, however, is proving complicated to set up for both normative and conceptual reasons, resulting in very few Tecnológico de Monterrey members of faculty having yet adopted this path. Finally, extension professors are tasked as experts and consultants, engaging directly with organisations and corporations. Evaluation indicators for extension professors are based on the number of programmes initiated and the revenues that these programmes generate for the HEI. As an incentive, extension professors earn a monetary complement above their regular wages. As is the case in most HEIs with similar multi-path faculty trajectories, professors are left to choose the path they would like to adopt (being an entrepreneurial professor or following a more traditional path).

Universities like Tecnológico de Monterrey that are implementing greater extension services directed towards responding to corporate needs have seen this line of transfer activity generate significant revenues. For Tecnológico de Monterrey, the revenues generated by the extension activities have made their extension professors the university’s most “profitable” faculty members. The UFSCar is increasingly counting on extension revenues as a source of supplementary income. This HEI is using extension revenues to complement royalties from licensing to foster further innovation from its research departments.

However, consultancy-based extension is mostly focused on large companies and corporations, and public organisations. As a result, many academic disciplines as well as the wider business community and society may be left out from the extension most of the time. This is why universities such as Uruguay’s UTEC have adopted social indicators within the evaluation process of the collaboration activities of their faculty. At Anahuac University, social criteria are present in all aspects of the university including as an integral part of academic evaluations.

Adapting knowledge transfer to the needs of the ecosystem

Although HEIs are taking ever-greater steps to “push” into the economy the knowledge and technologies generated within their departments and research labs, the target markets may not be able or willing to absorb this knowledge. In general, researchers tend to engage in relatively time-consuming lines of research, with the aim of advancing the frontier of knowledge in specific areas, often disconnected from the market in an immediate or obvious way. Companies, on the other hand, are generally interested in the development of short-term marketable solutions, or the incremental but not radical improvement of their internal processes (OECD, 2021[6])

In response, some HEIs are adopting knowledge development strategies that are much more demand-driven to generate appropriate technologies that better fit the markets’ needs. In this way, HEI technologies are more likely to be “pulled” by businesses, which better ensures the proper transfer of this knowledge into the economy. Several HEIs in Latin America have been historically implementing such a “pull” strategy.2 UFSCar prides itself on the ability to adapt very rapidly teachings and programmes to match the changing needs of the industry and its demands. In the case of Siglo 21, knowledge generation is strictly contextualised to include and cater to local specificities and demands. Because it is not a research university, this Argentinian HEI has focused on practical knowledge with greater local applicability. Most knowledge transfer in their case is demand-based and done through pedagogy in the classrooms or in‑company, as well as through the publications of specialised reports and publications. Siglo 21-generated knowledge is also disseminated through events organised by the university and by having an active presence within the popular media and press.

Similarly, developing greater extension services on the part of HEIs is often very useful for building relational capital with the business community. In this way, universities get to understand better market needs in terms of knowledge and technology demands. For Tecnológico de Monterrey, extension services have allowed it to detect needs and be proactive as to the design of new programmes and training, especially those related to training linked to new technologies that are often unavailable in certain regions. The proximity and close exchanges that the HEI is nurturing with the business community are fundamental to being able to design and offer the very best services. They are at the origin of many (applied) innovations and research projects undertaken by Monterrey researchers. The multi-service extension strategy has become very successful for the HEI and is largely the consequence of the reinforcing loop created by the relational proximity derived from its extension services.

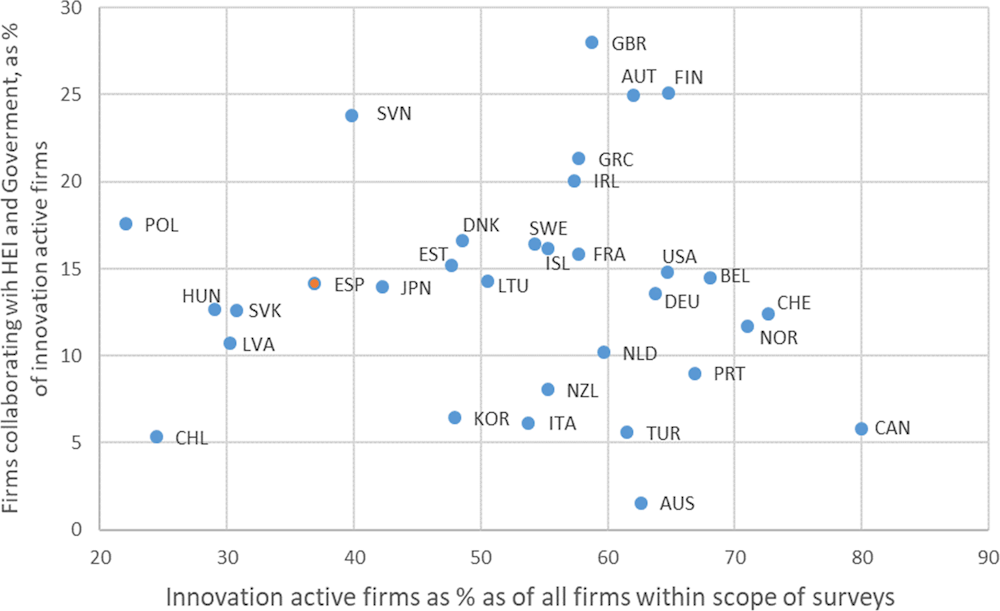

The relational capital of universities facilitates knowledge exchange

The relationship between universities and business is challenging, many Latin American ecosystems reflecting an international trend. Case study universities flagged that in many of their communities; businesses do not perceive universities as credible partners. However, this is not exclusive to Latin America and is a trait common across most OECD countries. Innovation surveys indicate that on average, OECD countries face low rates of collaboration between firms and HEIs in terms of knowledge transfers leading to innovation (Figure 3.1). Most firms manifest a lack of appreciation of the strategic importance of such transfers but also report other obstacles to collaboration with HEIs, including the lack of perceived openness and accessibility of universities. This is often both the cause and result, of a general lack of awareness and exchange across both these communities.

In relative terms, there has not been a historical tradition of collaboration between research and business in many OECD member countries. Lack of trust between the actors, due to lack of prior interaction, knowledge of each other’s activities and the use of different “languages” represent obvious barriers to transfer and collaboration (OECD, 2021[6]). From the perspective of the UAI, the innovation readiness of universities and businesses is not the same. Moreover, according to this university and as noted in the literature in this area, the incentives, agendas and timing of the different actors in the system are often not aligned (Bruneel, D’Este and Salter, 2010[7]). According to the Javeriana, the business community does not understand HEIs and HEIs often do not have sufficient time and resources to be able to cater adequately to local businesses.

The lack of mutual awareness contributes to the foregoing of numerous opportunities that could broaden horizons and strengthen knowledge exchange efforts and the innovation performance of firms. This in turn could increase the impacts of research carried out by HEIs. Siglo 21 tackles this lack of mutual awareness through a “constant interaction strategy” which involves nurturing connections with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), business associations and industry and responding to the specificities of local business communities through the development of partnerships.

Figure 3.1. Firms collaborating with HEIs and government in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2021[8]), OECD Business Innovation Statistics, https://oe.cd/innostats, accessed in May 2022.

Therefore, close ties with the community can become a source of strategic advantage guiding the HEIs’ research and knowledge transfer efforts. HEIs like Siglo 21, which have developed close relationships with local business communities, are positioned better to connect and contribute to updating local business knowledge, introducing them to new topics and new methods. Ultimately, this allows Siglo 21 to be more proactive and detect and introduce innovative issues to the local community. Frequent interactions and interrelations help to build trust and bridge the academic and business communities together. ICESI, for example, is capitalising on its business orientation and prioritising trust building with the local business community, which is fundamental for proper collaboration and connections to take hold. ICESI has reinforced these ties by naming the ex-president of the chambers of commerce as their new provost. For this HEI, close ties not only help transfers but are serving as a means of exchange that is making the university a much closer partner for businesses and a go-to outlet for solutions.

The road ahead from knowledge exchange to collaboration

The notion of knowledge exchange, as opposed to mere transfer, refers to relationships between HEIs and their ecosystem that are not unidirectional (neither “push” nor “pull”) or linear but rather interactive and collaborative. In such knowledge exchange relationships, it is not only universities that are relevant to the ecosystem but also the community that is an important source of knowledge for the HEIs. What is more, the co-creation of knowledge, where mixed teams of researchers from HEIs and industry engage in joint knowledge creation, is increasingly recognised as important for strong innovation performance (OECD, 2021[9]).

Connecting HEIs with their local ecosystem potentially benefits the promotion of mutual understanding about what is possible, or impossible, to achieve. Universities need to exchange with their local communities to achieve a place-responsive strategy and a tailored approach to respond to the specific needs of the local communities and avoid replicating models and “best practices”, in a spatially blind way (OECD, 2020[10]).3 A frequent practice within Latin American HEIs is to involve members of industry and representatives from the community to participate in joint orientation committees. Furthermore, the industry is often involved as a participant in curricular programming. More entrepreneurial-oriented HEIs tend to bring entrepreneurs into classes, whilst at the same time; professors in these HEIs are encouraged to get involved in entrepreneurship promotion activities.

Similarly, several HEIs in Latin America, as in many parts of the OECD, have been developing close ties with the private sector by establishing co-operative education programmes. These programmes are based on pedagogy alternating between academic classes and in-company student apprenticeships. Such programmes support the exchange of knowledge between the private sector and academia. Participating organisations benefit by having access to highly skilled labour, the opportunity to learn about the R&D being developed at the university and how this R&D could potentially be applied in their organisation. When a co-operative education student returns to their academic studies, they bring back an understanding of what is of interest to the industry. Professors and faculty hear discussions amongst students and during their courses. In many cases, professors and faculty apply the experience of co-operative education students to their courses and research (OECD, 2017[11]).

Tecnológico de Monterrey, UFSCar and ICESI encourage bidirectional learning and knowledge exchange through their extension services. These HEIs have observed significant research benefits from extension services, which give their researchers direct access to industry. As a result, improved empirical data and observations can be obtained for research whilst, at the same time, research topics tend to better capture and reflect business reality, needs and concerns. For ICESI, the close collaboration with its local ecosystem is helping to develop a needs-based research focus that is delivering more applicable knowledge outputs to local industry and businesses.

In the case of bidirectional knowledge exchange based on research collaboration and technology co‑creation between HEIs and private industry, Latin American examples exist but are still scarce. In the absence of strong collaboration, the innovations that come out of HEI labs usually need significant fine‑tuning to make them market-ready. The UFSCar sees significant differences between the level of preparedness of the technologies developed at the university and the level needed in order to be effectively commercialised and implemented by industry. Collaboration with industry and private businesses is necessary to mould HEI technologies into tradeable goods and services. However, dealing with the associated legal constraints and confidentiality restrictions is very time-consuming. Establishing a partnership agreement and abiding by the strict compliance norms imposed discourage collaboration with HEIs. This is found to be especially true of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and smaller entrepreneurial ventures. The very complicated legislation and internal bureaucracy needed to co-create with HEIs disincentivises SMEs since the process is often more expensive for them than the entire project budget. As a result, collaboration is often accessible only to large corporate groups with the time and resources to deal with the necessary due diligence and red tape. The incubators and accelerators however represent an alternative to connect with start-ups and SMEs to some degree. These facilities provide programmes for start-ups and SMEs, a form of partnership that has fewer legal constraints and confidentiality restrictions.

Co-creation efforts are also often marred in property rights issues. Private businesses that collaborated in technology development or those that develop the applicability of technologies in co‑operation with HEIs will require property rights over the technologies that they are adding value. However, the legal obstacles and bureaucracy required for this are often very complicated for private companies to face. According to the USP, business partners view the distribution of intellectual property on the results of potential research collaborations as a deterrent for research collaboration. New rules are therefore being implemented at this HEI that will attempt to bring clearer and more transparent terms regulating the intellectual property distribution when co-creation of innovation through university-industry research collaborations takes place.

Governmental organisations and public administrations also represent attractive knowledge collaborators for many Latin American HEIs. Despite its strong ties with the business community, ICESI admits that its favoured knowledge co-creation partners are public institutions, both from the local and national levels. For example, the university has developed a close relationship with a local hospital, which they report has contributed to the creation and dissemination of knowledge within the community. The disadvantage, however, highlighted by several HEIs collaborating with public administrations on R&D, is that these relationships are habitually affected by political issues.

In some cases, public sector collaborations can take place when there is a lack of demand for innovation transfer coming from the private sector. HEIs need to establish dynamic relationships between researchers and the external community for such research collaborations to take hold and this is very difficult. Both sides need help to get adequate contacts that will complement themselves and form synergies in their knowledge co-creation efforts. Too often, research collaborations with industry depend more on personal relationships between professors and industry partners, than systemised synergic matching. Many HEIs, such as Javeriana University, comment on the significant time and financial resources necessary to invest in suitably establishing the connections required for appropriate research-based knowledge exchange activities to take hold. There is a need for matchmaking, which creates an improved marketplace where both socio-economic problems and HEI-generated technology solutions can meet, but also where the agents from both sides can connect to work towards co-designing and developing new applied knowledge solutions. At Anahuac University, this has been largely solved by the establishment of networking associations that act as intermediates and facilitate matchmaking between research and industry.

Exchange intermediaries and lateral transfers

Case studies that have developed internal intermediaries of innovation

In an innovation environment in which business and research actors pursue seemingly different and often conflicting paradigms and goals, intermediaries play a crucial role in connecting actors and facilitating mutually beneficial knowledge exchange processes (Box 3.1) (OECD, 2021[9]).

Box 3.1. Knowledge intermediaries

In an innovation landscape characterised by low levels of collaboration between universities and firms, knowledge intermediaries play a crucial role in connecting these actors and facilitating knowledge exchange.

These intermediaries can take the form of:

Technology transfer offices, mainly attached to universities, created to facilitate the transfer of technology and knowledge from a university to the productive sector.

A consortium of technology transfer offices, with some technology transfer offices joining forces and mutualising their offer to the market.

Sciences parks, usually under the management of a public or private entity (whether the university, government or firms), with the goal of generating innovative knowledge to transfer to the market. In many countries such as Brazil, Mexico and Spain, science parks were created by public authorities as a tool to diversify the local economy and promote innovation. Many of these parks are located within the premises of the university campuses, provide support services, and dedicated spaces to host innovative start-ups.

Clusters or geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions (such as universities and researcher centres), linked by common technologies and skills.

Technological centres for R&D centres that provide research and technology services to companies and often collaborate with universities to translate research into practical application in professional settings.

Other intermediaries may exist: in Chile, for instance there is a non-for-profit organisation, the Integrated Piloting Centre of Mining Technologies (CIPTEMIN), which collaborates with universities to bring new research into the market. The centre provides a space to mature and test technologies developed by universities, and make them market ready.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2021[6]), “Improving knowledge transfer and collaboration between science and business in Spain”,

In order to facilitate and even instigate proper knowledge exchange and fruitful research collaborations between HEIs and their ecosystems, there need to be appropriate linkage and engagement networks. Knowledge intermediaries play very important roles in these networks. Technology centres, clusters, incubators, science and technology parks and specialised providers of professional services around the law, finance and intellectual property rights all represent likely examples of organisations that, under different settings and legal arrangements, help connect different actors and functions in the knowledge exchange system (OECD, 2021[6]).

In the case of much larger Latin American HEIs, these knowledge intermediation functions are often carried out in-house. Specific units within these universities are set up to carry out intermediary roles that help connect supply and demand for different types of knowledge. They also co‑ordinate the processes and bureaucracy associated with such exchange. Internal intermediary “centres” are a key presence at the UAI, as a connexion hub for external partners. Being distributed internally within each faculty, these centres are largely mono-disciplinary in nature and have developed into extension offices rather than true knowledge exchange intermediaries. As such, these centres act as a specialised consultancy that mainly push technology out of the UAI labs and facilitates the establishment of “spin-outs” based on UAI-developed technologies. Recent reforms, however, have been implemented to encourage more multidisciplinary collaborations and to make these centres more active facilitators of bidirectional exchange between the university’s researchers and external partners.

At the UFSCar, the points of connection between professors/researchers and external partners mostly originate out of the already existing relational capital of the people involved. Once the intention to collaborate is highlighted, the university’s internal knowledge intermediary agency must then be contacted to process the many required legal and administrative issues, such as confidentiality and property rights agreements. Each campus has its own innovation leader trying to link faculty members with the university’s centralised intermediary agency. Only on occasions when businesses do not have pre-established relationships with a professor will the HEI’s intermediation agency or innovation leaders act as a matchmaker. This is usually limited to larger corporate entities.

There are challenges facing internal intermediaries. Most often, there is a considerable gap between the state of the technology as developed by the HEI’s research labs and the level required to fit the needs of external partners. For legal reasons, a separate area at the UFSCar works with external partners on commercial adaptations. This area is legally and structurally separate from the departments where the technologies originated. As a result, true solution-based co-creation is unlikely and an internal intermediation figure is required to make the link between the different entities involved.

In contrast, the USP’s internal intermediary unit is much more active in bridging the university with its ecosystem. The role of their intermediaries across the university’s decentralised multi-campus network facilitates accessibility and provides multiple local points of contact for businesses to engage better with the university. As with most HEIs, these internal efforts are combined usually with external independent intermediaries under a wide range of configurations and services provided to both HEIs and businesses.

Case study universities collaborating with external intermediaries of innovation

External intermediaries come in many different forms and are likely to offer different types of services (Box 3.1). Some provide space to bring physically HEI researchers and their counterparts from the private sector together to co-work on joint innovation projects, whilst others rely more on their specialised staff to link both these parts together and offer assistance to help strengthen their exchanges. External intermediaries can have a generalist perspective (such as the Fraunhofer Institutes, see Box 3.2) or be limited in scope to only one specific sector of technology. In the same way, some offer a wide menu of services to both HEIs and the private sector, while others are more functionally specialised in aspects such as law, IP or finance and offer this expertise for the benefit of knowledge exchange initiatives.

Box 3.2. The Fraunhofer Institutes

The Fraunhofer-Gessellschaft based in Germany is one of the biggest applied research organisations. Founded in 1949, the organisation has 76 institutes throughout the country. The organisation turns scientific research and technologies into commercial products ready to be used by companies. It operates in key technology areas such as artificial intelligence and cybersecurity medicine. The institutes work closely with universities, with university professors being appointed as Fraunhofer institute directors to create ties and make sure that the results of university research are applied. The institutes also collaborate with universities for different acceleration and incubation programmes. For example, Fraunhofer has collaborated with UnternehmerTUM, the innovation centre of the Technical University of Munich, to provide support to spin-offs within the context of their FDays 12-week acceleration programme that acts as a stress test for market, team and technology. At the request of the federal government, the institute is working with a pool of companies and universities to push forward interdisciplinary research and transform it into application-oriented technology developments.

Source: Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft (2022[12]), Cooperation with Universities, https://www.fraunhofer.de/en/about-fraunhofer/profile-structure/structure-organization.html; OECD (2021[6]), “Improving knowledge transfer and collaboration between science and business in Spain”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4d787b35-en.

Some of the benefits of being external and set up as independent organisations – either for-profit private initiatives or non-profit associations and foundations – come from the added operational flexibility relative to the HEI’s internally governed intermediaries. External intermediaries also tend to act in greater proximity with the private sector, allowing them to better appreciate local concerns and capture the ecosystem’s knowledge needs. As a result, external intermediaries understand the level of adaptation required for the effective implementation of HEI-generated knowledge. This can potentially allow them to act as effective “translators” helping researchers and businesses to connect and reach common goals. External intermediaries also tend to sustain a number of simultaneous connections with different research entities, not being limited to a single HEI. This allows some of them to reach a critical mass that permits greater functional or disciplinary specialisation. Depending on their structure, external intermediaries are usually not aiming to “push” any existing HEI technologies onto the market, nor are they looking to simply solve business problems. Rather, they are in the business of setting connections and offering the services that will make these connections transform into impactful knowledge exchange.

In several OECD countries, however, the (over)abundance of these external intermediaries has generated calls for greater co-ordination in order to avoid frequent overlaps in the provision of services and the engendered confusion on the part of intended beneficiaries as to where to turn to for adequate assistance (OECD, 2021[6]). Co-ordinating the operations of diverse knowledge intermediation agents – including knowledge transfer services within universities as well as independent knowledge intermediaries such as technology centres, science and technology parks and clusters – has become a priority for effective knowledge exchange.

However, this phenomenon was not detected during the analysis of the Latin American knowledge exchange ecosystems. In fact, several ecosystems lacked the presence of external intermediaries or have intermediaries that suffered from insufficient resources and professional expertise to be able to reach satisfactorily the knowledge exchange goals that they set for themselves. On the other hand, some external intermediaries found in Latin America are very effective in their tasks and have become key players in orchestrating their entire knowledge exchange ecosystem.

Brazil’s ONOVOLAB is one of these transcendent external intermediaries that has become an essential knowledge exchange player in many parts of the country. As a private entity, ONOVOLAB is the largest independent innovation intermediary based in Brazil, promoting innovation, science, technology and entrepreneurship. They offer physical spaces for innovation and co-creation, as well as a range of professional services including venture capital intermediation, helping link technology spin-off projects to funding. They also host networking and dissemination events that serve to place ONOVOLAB as the critical hub connecting most parts of the knowledge exchange ecosystem to each other.

As a result of ONOVOLAB’s effectiveness, HEIs such as UFSCar have been outsourcing their matchmaking intermediary services. As noted in the previous section, the UFSCar internal intermediary agency mostly offers administrative support and facilitates internal connections but external bridging tasks are mostly delegated to external intermediaries. ONOVOLAB has developed a methodology for better matchmaking external needs with UFSCar knowledge creation. In general, businesses in UFSCar’s ecosystem are not prepared and oriented towards innovation. ONOVOLAB works to break down knowledge barriers limiting businesses and match them to knowledge. The intermediary is implementing a novel approach to innovation in an ecosystem with multiple players. This is helping to break down cultural innovation barriers and facilitate the effective exchange of knowledge between HEIs and their ecosystem.

Connect Bogotá is another significant external intermediary at the root of an effective knowledge exchange ecosystem. Connect Bogotá is a mission-based association of over 60 private, public, academic and government sector organisations aiming to develop, support and implement projects that promote science, technology, innovation and entrepreneurship in the region so as to support its socio-economic transformation. The Javeriana, together with other public and private organisations, is a member of this network. As such, they gain access to a set of benefits and services that can help the university enhance its innovation output, generate valuable connections and exchange with the business community, and strengthen its capacity to exercise collective leadership.

Despite the significant presence of Connect Bogotá within Javeriana University’s knowledge exchange ecosystem, interviews highlight that the HEI still believes that there remains a mismatch between external needs and HEI-supplied technologies, requiring a marketplace where both social/business problems and HEI-generated solutions can meet. External brokers are needed to help bring these parties together. To complement the actions of Connect Bogotá, the university is working on elaborating an inventory of external intermediaries and experts that could give visibility to these actors and help tie some problem-solution knots together.

In this vein, Anahuac University relies heavily on external networking associations to facilitate matchmaking. These associations “walk around” the local economic/industrial community to understand them better and predict the knowledge and recruitment needs of industries for the future. As such, through their prospective use of these external intermediaries, the university has developed a more proactive attitude towards knowledge exchange, with the intermediaries facilitating the bidirectional flow of knowledge that allows this forward-thinking exchange to happen.

In the case of Siglo 21, its “local” rather than “technological” knowledge exchange focus has meant that many external intermediaries present in its ecosystem did not align with the university’s output. Because technology is seldom understood by most in its targeted communities, the university has adopted a leadership role within its ecosystem and has emphasised the importance of vulgarising and adapting HEI-produced knowledge to optimise its value for local industry and the population. In this quest, Siglo 21 has teamed up with several community-based NGOs and business associations to promote knowledge exchange with its local ecosystem. The university has signed several collaboration agreements with these indirect local intermediaries. The close connection with these intermediaries is helping the HEI’s faculty members and students to better adapt themselves to the “language” and needs of local businesses and civil society.

Lateral exchange and co‑operation among Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) HEIs

Engagement and collaboration offer opportunities for networking among Latin American universities, helping reduce the fragmentation in higher education systems. A characteristic of the Latin American knowledge exchange system that stands out is the importance of lateral knowledge transfers. Although the phenomenon is also found in other OECD countries, the occurrence of collaborations across different HEIs as part of their knowledge exchange efforts was notable in the analysed Latin American innovation ecosystems. These collaborations go further than simple networking and the exchange of best practices. Often, they are partnerships aimed to either share resources and/or reach greater critical mass to be able to develop further services and establish more effective knowledge exchange ecosystems.

Many of these collaborations originated from resource or service deficiencies within their knowledge exchange ecosystem that HEIs compensated for by joining forces. In this way, when significant public support was removed in Mexico because of the federal administration’s change in priorities, Anahuac University merged its entrepreneurship promotion programmes with those of other HEIs in order not to lose the effectiveness of its outreach.

The Connect Bogotá platform highlights a different approach to lateral knowledge. It brings together a consortium of as many as 25 different HEIs joining forces in order to create synergies and generate a collective impact that could hardly be attained without such collaboration. As mentioned in the previous section, the consortium of HEIs works together with private and governmental representatives in order to “transform Bogotá into the most innovative and entrepreneurial region in Latin America” (Connect Bogota, 2022[13]).

Apart from the impact of the collective goals of such coalitions, there are benefits for each individual participating HEI. The Javeriana has been able to share both experiences and resources across other HEIs, efforts that have been reciprocated to the benefit of the university’s entrepreneurship promotion programmes and outreach. According to the Javeriana, the different universities that are part of Connect Bogotá tend to complement each other. This happens in an atmosphere of “co‑opetition”. Whereas the original stance across the different HEIs was one of competition within the region, through Connect Bogotá, it has evolved to set the stage for the collaboration, taking place today for the greater goal of the entire ecosystem. As such, the coalition has helped the Javeriana to establish conversations and facilitated both vertical and lateral connections.

Another common form of lateral collaboration and knowledge exchange among case study Latin American HEIs comes from bridging social capital with international HEIs. The innovation model developed by the Javeriana comes from the University of San Diego, which provided representatives of the Javeriana with insights into the workings behind the method that has been successful for the Californian HEI. The Javeriana not only implemented this method within its own campuses but it shared this knowledge with the other Connect Bogotá HEI members.

A similar dynamic is seen at Anahuac University, which helps public universities with fewer resources to set up knowledge exchange projects. The university uses its international relations and its capacity to develop international networks to tap into new sources of knowledge and bridge these back into the local ecosystem in the form of resources, techniques and methods that they then share with local public universities. A similar practice is found at Siglo 21, which describes itself as an importer and distributor of knowledge coming from afar, into the region. Tecnológico de Monterrey also has a policy of looking outwards and collaborating with other international universities in order to capture new knowledge from abroad that can then be shared nationally. At its origins, the Monterrey model was inspired by MIT and brought to Mexico. Over its history, Tecnológico de Monterrey has then duplicated this model across its different regional campuses spread out throughout the country.

Public policies and vehicles to foster knowledge exchange

Although the objective of the study presented in this report was not aimed specifically toward the analysis of public knowledge exchange support policy, HEI views of such policy were nevertheless captured. In this regard, there are important country-level, and sometimes regional, distinctions throughout Latin America that prevent any clear generalisation. Yet, there is a common perspective expressed by HEIs across Latin America that, often, public administrations (national and regional governments alike) are not the principal leaders of knowledge exchange efforts within ecosystems. This contrasts with many other public administrations throughout OECD member countries that are increasingly prioritising and emphasising the importance of knowledge exchange, not only through words but also through actions and leadership4 . It is true that it may sometimes be difficult for HEI to appreciate the impacts of public policy and measures whose scope may stretch further than the limited interests of the HEI. However, rarely did the HEIs under analysis identify local, regional or national public departments as prominent figures within their knowledge exchange ecosystem. More often than not, policy was perceived as a source of constraint rather than facilitation.

One clear and noteworthy exception to this, however, is Colombia’s General Royalties system Sistema General de Regalías (SGR) programme. The SGR is primarily a financial support programme, which originally served to compensate territories for the exploitation of non-renewable resources but has since taken on much wider social knowledge appropriation goals. The objectives of the most recent version of the programme5 are to:

Create conditions of equity in income distribution through saving for times of scarcity.

Distribute resources to the poorest population, generating greater social equity.

Promote regional development and competitiveness.

Incentivise mining and energy projects (both for small and medium industries and for artisanal mining).

Promote the integration of territorial entities in common projects.

Promote investment in the social and economic restoration of territories where exploration and exploitation activities are carried out.

This SGR programme complements existing financial transfers directed to research in Colombia. The SGR’s knowledge exchange impact is derived from its efforts to better link the knowledge and innovation created in HEIs with the socio-economic needs of the local ecosystem. On a practical level, regional development plans are developed through civic discussions and participation. HEIs and their research faculty then formulate research proposals that are evaluated and financed according to their contributions to the SGR objectives and the regional priorities as set in their development plan. Because of the amounts of transfers involved and the close co‑ordination of national policy, community priorities and HEI research efforts; this programme has had a noteworthy impact on steering the focus of HEI research and knowledge exchange towards applied topics of local importance. The resulting multidisciplinary knowledge output of HEIs has consequently become much more place-based and socially appropriable. Both ICESI and the Javeriana acknowledge that the SGR programme is in part responsible for influencing the greater social orientation of their institutional strategies.

In contrast to this, where access to public funding for HEIs and their researchers has become more constrained, innovation policy has largely shifted away from local social issues towards more revenue-generating corporate extension service delivery. This has been the experience of Tecnológico de Monterrey, which stated that because public funding for the HEI was disappearing, most of its financial resources now came from the private sector.

A public sector programme that was identified as having a positive contribution towards HEI knowledge exchange is Chile’s Production Development Corporation (CORFO) initiative called Engineering 2030, which sees particular engineering schools receive support to align their education and learning environment with societal grand challenges. This programme was identified as having a significant impact on the country’s engineering faculties in terms of both pedagogy and research. From the teaching aspect, the UAI took advantage of the programme to reform significantly its engineering curriculum. With the objective of modernising and transitioning from fundamentals to a more applied curriculum, greater innovation and entrepreneurial training was included in their engineering programmes. They also shortened the length of the HEI’s engineering programmes and developed greater co‑operation with external businesses for internships and practice. Executive programmes were added to complement their existing academic-oriented postgraduate engineering courses.

The UAI also took advantage of this programme to transition its engineering research focus by offering greater support for applied research. The PUC also benefitted from the Engineering 2030 support, which they used to team up with Federico Santa María Technical University to instigate internationally recognised research whilst ensuring that the HEI contributes to the social, environmental, political, and economic development of the country.6

The impact of the Engineering 2030 initiative was significant but limited to schools of engineering. Similar reform could amplify the knowledge exchange impact of HEIs by holistically making all disciplines and faculties include incentives to stimulate a more applied approach to higher education and research. Without abandoning fundamental research, introducing greater incentives and strategic orientation for applied research where they do not currently exist has been demonstrated to be an effective policy to stimulate greater knowledge exchange. This is a path that public policies should explore to assist HEIs in their knowledge exchange efforts.

Box 3.3. The Sexenium for Knowledge Transfer and Innovation in Spain: An effective economic incentive for researchers

The Sexenium for Knowledge Transfer and Innovation was introduced in Spain by the national public administration as a pilot in 2018, replicating the success model of the existing Sexenium for research. These are accredited merit recognitions (based on six-year contribution intervals) that encourage transfer activities between teaching and research staff in universities and public research centres. These lead to economic incentives and offer added recognition for career advancements and promotions. The number of applications in the first call far exceeded expectations, reflecting both the interest of the Spanish scientific community in this instrument and the fact that a broad definition of the concept of transfer was considered. This instrument, which has no international equivalent, is contributing to progressively promoting a greater transfer culture among researchers in Spain.

Source: OECD (2021[6]), “Improving knowledge transfer and collaboration between science and business in Spain”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4d787b35-en.

From the perspective of many case study HEIs in Latin America, there is a lack of incentives to adapt and transfer knowledge and connect research to innovation. The main constraints to technology transfer at the USP, from the researchers’ point of view, come from regulatory problems linked to contracts that demand exclusivity over property rights on generated knowledge. This means that much of the knowledge created within the HEI cannot be commercialised or “spun off” through entrepreneurial initiatives or collaborations. From the businesses’ point of view, the imposed distribution of intellectual property on the results of potential research collaborations detracts industry involvement. The big problem for innovation at the USP, therefore, is structure and incentives that are very academic-oriented; the same can be said for many public HEIs in Latin America.

Public legislation is not as much of a limiting factor as the institutionalised constraints implemented by many HEI administrations and regulatory bodies. The law is permissive according to the USFCar but it is very hard to internalise and change the institutional framework and norms to make things more agile and compatible with HEI-business collaborations and exchanges. Internal policy restraints and audits are counter-productive when it comes to promoting innovation, knowledge transfer and commercialisation. At the USP, significant effort and resources are dedicated to legal proofing all initiatives, which slows down procedures, diminishes motivation and disincentivises proactivity and innovation. Nevertheless, many USP faculty are involved in innovation even though no formal incentives are in place.

New policy, however, being brought in by the new management of the USP, is attempting to bring clearer and more transparent terms regulating intellectual property distribution when innovation co-creation through university-industry research collaborations take place. It is hoped that this will significantly change the attitudes towards knowledge exchange and transfer and remove some of the bureaucratic obstacles to HEI-business collaboration. As it stands, many HEI administrations in Latin America are not incentivised to stimulate change that could promote greater knowledge exchange. Internal resistance to change and the need for significant normative reforms means that they often run the strong risk of reprimand if they do not meet established expectations.

In Brazil, innovation legislation put in place in 2016 legally opened up the path for change. However, a larger factor in stimulating change in internal attitudes towards collaboration with industry and establishing a more agile technology transfer system at the USP has been the change in leadership. In response to pressure from students and faculty members pushing for change towards more innovation-adapted governance, the university’s new administration has made innovation its main priority. A new adjunct rector of innovation has been named and this position has been “constitutionalised” to assure permanence and resistance to political shift. Such senior backing is necessary to change and surmount the culturally embedded institutional obstacles to innovation that have set in over a long period. New leadership was required to direct the institution down a more knowledge exchange-friendly path. The USP administration is working to spread an innovation-compatible mentality to all departments. Similar scenarios are playing out throughout the Latin American HEI community.

Greater involvement from public administrations through cross-disciplinary initiatives such as Chile’s Engineering 2030, in conjunction with the HEI administrations, could have a significant impact on encouraging the transition of HEI to more exchange-compatible applied pedagogy and research in Latin America. This could help set clearer objectives and guidelines that would contribute to overcoming existing resistance still present in the internal culture and norms of many HEIs.

Although universities are seeking to improve and reform their internal regulations and norms to become more innovation-friendly, the fiscal system in many countries is also playing a role in disincentivising innovation. It is perceived by some HEIs that public audits and accounting have a public finance optimisation approach rather than one aimed towards maximising innovation output and exchange. From the HEIs’ perspective, both the fiscal legislation and the fiscal inspections and monitoring practices would benefit from public policy reforms that are more compatible with HEIs’ knowledge exchange practices.

At UTEC, they have made use of digital platforms to help co‑ordinate and homogenise this monitoring process. Despite the independence of its 11 different campuses, there are common indicators and goals set to help control and monitor the system. This allows for objective-based financing across strategic areas and permits UTEC to more easily present indicators that align with the governmental strategy and correspond to public monitoring criteria. This has contributed to diminishing the burden of fiscal audits and inspections and consequently has facilitated the acquisition of public funds.

HEIs’ role in promoting place-based capabilities and specialisations (smart specialisation)

The many examples of local adaptation on the part of HEIs to the specificities of their knowledge exchange ecosystem noted in this chapter bear witness to the role that HEIs can have in the promotion of smart specialisation within their territories. Smart specialisation is an approach to regional growth built around existing place-based capabilities. The goal of smart specialisation is not to make the economic structure of regions more specialised (i.e. less diversified) but instead to leverage existing strengths, identify hidden opportunities and generate novel platforms upon which regions can build competitive advantage in high-value-added activities (OECD, 2021[9]). Smart specialisation from the HEIs perspective focuses on building competitive advantage in research domains and sectors where regions possess strengths and leveraging those capabilities through diversification into related activities. A place-based, bottom-up smart specialisation for HEIs would lead it to focus on improving attributes that strengthen desired territorial processes (Capello and Kroll, 2016[14]).

Box 3.4. The Academy for Smart Specialisation in Sweden: Putting an HEI at the heart of a regional smart specialisation strategy

The region of Värmland, Sweden has joined forces with the University of Karlstad to create the Academy for Smart Specialisation in Värmland. The university is located in Karlstad, the main city of the region of Värmland, in North Middle Sweden. This initiative was part of the regional government of Värmland’s ambitious smart specialisation strategy to strengthen R&D capacity, support the diversification of the economy in new sectors, create new skills and revive a decaying industry of pulp and paper (Värmland’s Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation 2015-2020, VRIS3). Karlstad University and Region Värmland jointly run the Academy for Smart Specialisation. The purpose of the academy is to serve as a meeting place and co‑operation platform for researchers, companies, and financiers, the public sector and entrepreneurs. The Academy for Smart Specialisation hosts different research groups and projects. Most of these mirror the sectorial priorities as identified by the Värmland smart specialisation strategy (such as forest-based bioeconomy, digitalisation of welfare services, renewable energy, etc.).

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Evaluation of the Academy for Smart Specialisation, The Geography of Higher Education, OECD, Paris.

Several Latin American HEIs were deliberately implementing approaches that can be considered smart specialisation strategies, in connection with their knowledge exchange practices, whilst several others were following very similar models to smart specialisation without necessarily naming it as such. The Javeriana is following the principles of smart specialisation to guide its research and exchange orientations. Proximity is an important part of the Javeriana’s smart specialisation strategy. The areas of innovation that are encouraged within the HEI are those that fit the strengths and related capacity-building necessities of the ecosystem. This is reflected in the importance given to being place-based as part of the university’s development strategy.

Argentina’s Siglo 21 is a university with very a strong local orientation in all its activities. Knowledge generation is strictly contextualised to include and cater to local specificities. The focus at Siglo 21 is a community-based commitment rather than smart specialisation as such: they have developed an organisational culture and mind-set oriented towards the HEI’s ecosystem. As a result, the geographic impact of the HEI is widespread in all regions of Argentina where the university is active. Collaborations with community NGOs and the active participation of their students enable the university to reach out to all of the communities in which Siglo 21 students reside.

As part of the USP’s innovation orientation, the university is playing a much more influential role within the different local ecosystems where it has a presence. The university is now taking steps to become a much more active part of the place-based innovation processes of each locality. An example of this is InnovCity, which is a government initiative to transform a key part of the city of São Paulo into an innovation-driven community. The USP’s main campus is centrally located within this InnovCity and, as such, assumes a leading role in its conceptualisation and development.

For its part, UFSCar has had a clear role historically as part of the spatial development of its ecosystem. This has resulted from 50 years of efforts to “connect the dots” since the establishment of UFSCar. As a result of UFSCar teaching and knowledge exchange activities, a critical mass of qualified human capital and related technology industries were established in the region, creating a positive reinforcement loop which has helped to guide the territory’s development path. The demand for qualified human capital in the region has increased because of the profound change in the local ecosystem. The change was gradual and place-specific. The region now has a reputation for technology and not simply one type or source of technology but a mix and variety of knowledge creation and commercialisation. With a high number of technology start-ups being created today, UFSCar is rapidly seeking to adapt teachings and programmes to match the changing needs of the industry and its demands.

Universities in Latin America have an important role to play in helping societies adapt to global shifts