To fully align with the SDGs, and build resilience to future global shocks, financing must be both sustainable and equitable. As the cross-border impacts of climate, health, geopolitical, economic and social emergencies demonstrate, there can be no sustainability without equity. In developed countries, a recent boom in investment labelled as sustainable has increased the trillions of US dollars in financial assets seeking to mitigate environmental, social and governance risk and to preserve long-term value. Yet this finance is largely bypassing the countries that need it most, and access to sustainable finance remains inequitable. Little progress has been made to redirect finance in support of SDG impact, e.g. to address the risks of growing poverty and inequalities. Much remains to design SDG-aligned regulations, frameworks and standards, to build sustainable finance markets and to redirect financing all along the SDG value chain.

Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023

3. Sustainable Development Goal alignment for a just and sustainable recovery

Abstract

3.1. Sustainable Development Goal alignment for a just and sustainable recovery

The shocks induced by COVID-19 and Russia’s war in Ukraine are widening the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) financing gap and derailing progress to achieve the 2030 Agenda. Governments’ failure to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the early stages of the pandemic led to a crisis of global proportions that resulted in historic economic losses. The COVID-19 crisis is projected to have economic and health-related costs of up to 20% of 2019 GDP, or USD 18 trillion in 2020-22 (Congressional Research Service, 2021[1]). The systemic risk of the impact of a global health crisis on financing for sustainable development (FSD) was severely underestimated. While women were at the frontline of and among the hardest hit by the pandemic, few governments provided guidance to include gender equality in budget allocations (OECD/UN Women, 2021[2]). As Chapter 2 demonstrates, cascading effects across the FSD landscape have resulted in a 56% increase in the SDG financing gap in 2019-20, with USD 3.9 trillion now required annually to meet financing needs in developing countries. The pandemic lockdowns accelerated inequalities within countries, putting them at risk of a further slowdown in both economic recovery and progress towards the global goals. The war is adding to the strain of other economic, climate-related and social crises, particularly on the most vulnerable countries and marginalised population groups with the fewest resources to manage their impacts.

The need for collective action to promote the SDG alignment of financing for a greener, more inclusive and resilient future has never been more urgent. SDG alignment of finance remains a prime solution for shifting the trillions towards a better prevention and management of global risks, and the achievement of the 2030 Agenda. The heightened interdependence of nations is made visible by key issues such as climate, health, economics and social emergencies that require multilateral action. As globalisation of the flow of finance, people and goods accelerates, these flows can spread benefits as well as risks more rapidly across nations (Goldin, 2021[3]). As the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General warns, only seven years remain to achieve the 17 SDGs, and “rescuing the SDGs means rescuing developing economies around the world” (UN, 2022[4]). In other words, achieving the SDGs anywhere requires that they be achieved everywhere. However, as noted in Chapter 1, a Great Divergence between developed and developing countries is emerging for the first time in decades. Recent evidence suggests that OECD countries are not progressing towards SDG targets that focus on ensuring no one is left behind (OECD, 2022[5]).

The following subsection takes a closer look at the weaknesses in the FSD landscape that could increase the Great Divergence between developed and developing countries and threaten global resilience.

3.1.1. The pandemic amplified pre-existing imbalances in the global financial system

The commitment to mobilise “billions to trillions” has yet to bring the public and private sector closer to narrowing the SDG financing gap in developing countries (African Development Bank et al., 2015[6]). Official development assistance (ODA), totalling USD 179 billion in 2021, remains below the 0.7% ODA to gross national income commitment and represents a small share (4.6%) of the USD 3.9 trillion annual SDG financing gap. However, ODA has a special role to play as one of the only sources of external financing that has the main objective of supporting the sustainable economic development and welfare of developing countries and is provided at favourable market conditions.1 Nearly eight years ago, the Development Committee of the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund (IMF), seeking to better leverage scarce official development resources, called for public sector concessional financing to be used to de-risk and thereby mobilise additional trillions in private sector resources. The aim of bringing together public sector actors seeking development outcomes and private sector actors seeking profit has since faced challenges. These result from “competing and contradictory incentives, mandates and priorities”, and recent studies offer further evidence that financial de-risking can create perverse incentives and impede domestic ownership (European Parliament et al., 2020[7]). As Chapter 2 notes, private finance mobilised by official development finance interventions grew by 11% in 2020, from USD 46.4 billion to USD 51.3 billion in 2019-20, following a 4% drop in 2018-19. While it is not expected that these flows can fill the entire financing gap, amounts of private finance mobilised remain roughly 70 times lower than the annual SDG financing gap post-COVID-19. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda, adopted in 2015, recognises that all resources – public, private, domestic and international – are necessary to achieve the 2030 Agenda and that no single resource is sufficient.

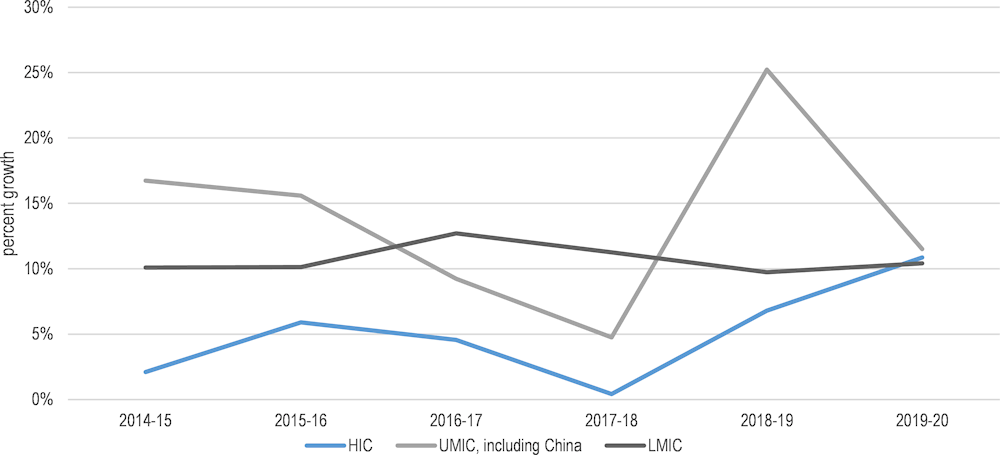

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the value of financial assets (stocks) held in developed countries increased. Monetary policy, including quantitative easing by major economies, contributed to an 11% increase in the value of global financial assets, from USD 423 trillion to USD 469 trillion, in 2019-20.2 Public sector actors in developed countries, including central banks and institutional investors, responded quickly to mobilise trillions of dollars in support of the short-term emergency response to COVID-19, as elaborated in Box 3.1. The annual growth rate of assets held in high-income countries (HICs) continued to increase after the outbreak of the pandemic (Figure 3.1). Thanks in part to the actions of central banks, the growth rate of assets held in HICs increased from 7% in 2018-19 to 11% in 2019-20, while growth in upper middle-income countries (UMICs) declined from 25% in 2018-19 to 12% in 2019-20. In addition, growth in lower middle-income countries (LMICs) remained at 10% in 2018-20. Developing countries held less than 20% of global financial assets, valued at USD 93 trillion in 2020, yet these countries represent 84% of the world’s population and 58% of global GDP. Only 5.7% of ODA-eligible countries (8 out of 140), none of which are low-income countries (LICs), are included in reporting on financial assets by the Financial Stability Board, evidence of a persistent barrier to deepening financial markets in these countries. A survey carried out by the OECD before the pandemic found that institutional investors were facing investment restrictions related to risk-based capital requirements that prevented resources from being allocated to developing countries or certain segments of the population. For example, the 36 pension funds that participated in the survey reported holding assets in developing countries worth USD 263.7 billion in 2017-18, representing just 8% of their total assets globally (OECD, 2021[8]).

Figure 3.1. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth rate of financial assets held in developing countries fell or remained stagnant while high-income countries registered significant growth

Note: The figure uses World Bank income categories.

Source: Authors based on Financial Stability Board (2021[9]), Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2021, https://www.fsb.org/2021/12/global-monitoring-report-on-non-bank-financial-intermediation-2021/.

Box 3.1. In response to the pandemic, central banks in developed countries increased the trillions of dollars of financial assets

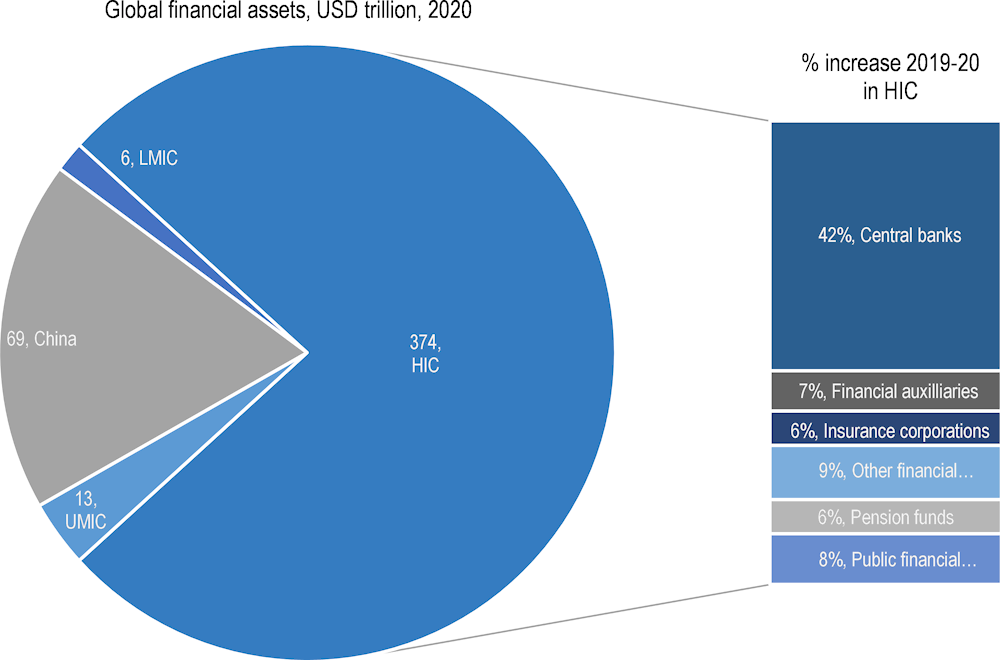

Financial assets held by central banks in HICs grew faster than assets held by other actors in the first year of the pandemic, increasing 42% from 2019 to 2020. The historic COVID-19 monetary response has demonstrated that public sector actors have tremendous influence over the allocation of global financial assets, with the value of financial assets held by central banks increasing by nearly USD 20 trillion in 2019-20 (Figure 3.2). To respond to COVID-19, central banks in major economies adopted a whatever-it-takes approach to monetary policy. For example, the euro system bought assets worth more than USD 1.85 trillion under the European Union (EU) pandemic emergency purchase programme alone through March 2022 (Schnabel, 2021[10]). The liquidity support provided by central banks kept interest rates low, reassuring markets, and buoyed the stock market rebound, benefitting nearly all other financial actors in 2019-20. Public pension funds that hold long-term patient capital were also called upon to go beyond their usual remit to disburse short-term emergency retirement funds or purchase COVID-19 bonds. Public financial institutions such as public development banks (PDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) also provided pandemic support. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean alone, PDBs channelled USD 90 billion in credit support for emergency economic relief (Finance in Common Coalition, 2021[11]).

Figure 3.2. Central bank asset purchases during the COVID-19 outbreak helped buoy asset valuation across financial sector actors

Note: Coverage includes all countries included in Financial Stability Board reporting.

Source: Authors based on Financial Stability Board, (2021[9]), Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2021, https://www.fsb.org/2021/12/global-monitoring-report-on-non-bank-financial-intermediation-2021/.

However, the trillions in recovery spending by developed countries could have unintended collateral effects, and exacerbate pre-existing macro financial vulnerabilities in developing countries. While USD 18.2 trillion was spent on COVID-19 economic relief by March 2022, just 20% of this amount was spent on long-term build back better recovery and less than 1% was spent in support of developing countries (i.e. USD 162.2 billion of bilateral ODA in 2020) ( (IEA, 2022[12]) (WBG, 2022[13])). Moreover, at least 14% of the total COVID-19 economic recovery spending in OECD, EU and key partner countries has mixed or negative impacts on the environment. The proportion could increase as fuel prices rise and governments implement consumption subsidies to protect the most vulnerable. The latest SDG Index developed by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network also shows that major economies are largely responsible for negative transboundary spillovers due to unsustainable trade and supply chains (Sachs et al., 2022[14]). While asset purchases by developed economies are being scaled back to avoid overheating and inflation, an abrupt slowdown could result in a stronger US dollar, weaken emerging market currencies and potentially drive further capital outflow from developing countries (Chapter 1). Consequently, countries furthest behind find themselves with even fewer resources than before the outbreak of the pandemic and even higher costs to achieve the global goals. The next subsection examines how to promote the SDG alignment of all sources of financing.

3.1.2. Sustainable finance can build global resilience and help to ensure no one is left behind.

The build back better agenda is an opportunity to finance global public goods more effectively and avoid costly setbacks in the future. Previous global crises have shown that political turmoil and economic deterioration in developing countries significantly affect financial stability globally. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the cost-effectiveness of investing in resilience and preparedness in developing countries became more apparent. Recognising the importance of financing to leave no one behind, Group of Seven (G7) leaders at the Carbis Bay Summit in 2021 set out a vision based on building back better to narrow the infrastructure investment gap in developing countries and address the impacts of the pandemic on climate change, health, digital connectivity, gender equality and equity. With its recent creation of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, the G7 seeks to mobilise private finance (USD 600 billion in total over the next five years) in support of infrastructure financing in developing countries. The Partnership should avoid the mistakes of the past (e.g. a lack of domestic ownership) but focus on helping build the local enabling environment, including by supporting local financial markets and technical assistance to secure a pipeline of sustainable and investable projects in developing countries (The White House, 2022[15]). (Section 3.4 outlines further actions.)

However, current crises could either strain or accelerate collective action to align finance in support of global agendas for sustainability. On one hand, unequal access to vaccines and the impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine have accelerated the fragmentation of the global economy, demonstrated by a growing number of trade and investment restrictions and diverging policy approaches that are being implemented unilaterally (OECD, 2021[16]). Developing countries are confronted with a vicious cycle of short-term emergencies (e.g. climate damage, biodiversity loss, rising food prices, debt distress, etc.) that simultaneously increase financing needs and decrease the availability of financing. For example, sovereign credit rating downgrades and higher debt service costs reduce available government revenues needed to invest in the SDGs over the long term. On the other, common interests such as energy security have moved higher on the political agenda of all countries and could accelerate action in support of net-zero commitments.

SDG alignment provides a two-pillar framework to ensure a sustainability equilibrium of finance and investment targeted across the global goals and to leave no one behind. As the 2021 FSD Global Outlook noted, SDG alignment provides a framework to assess financing across two pillars: 1) sustainability and 2) equity. Both are needed to build resilience. The two pillars complement one another and are equally important:

1. To be sustainable, resources should avoid zero-sum trade-offs across the SDGs and ensure a financial sustainability equilibrium. Investing in any one goal can represent an opportunity cost to invest in the other goals. Resources should aim to promote a triple bottom line within the sustainability equilibrium – that is, to leverage synergies across environmental, social and economic outcomes. Despite a 15% increase in sustainable finance in 2018-20, totalling USD 35 trillion, such financing lacks transparency and accountability for impact across the SDGs (i.e. SDG washing). Of the USD 1.8 trillion of so-called sustainable bond issuances since 2014, 56% focused on environmental goals of the SDGs while only 18% targeted social objectives in areas such as quality education, hunger, poverty and gender equality.3

2. Finance must be equitable to be sustainable and if unaddressed, financing gaps in the most vulnerable countries will widen and contribute to even greater setbacks globally. The “shift” in the trillions should reduce inequalities in access to sustainable finance across countries, allowing for more efficient management and prevention of global risks. The growing financing gap means developing countries will have insufficient resources to address future shocks, e.g. rising temperatures, value chain disruption, refugee influx, etc. Likewise, maximising positive transboundary spillovers can help all countries reach the SDGs more quickly, including by reducing the cost of progress at home. However, the sustainability boom is not yet benefitting HICs and developing countries equally. Without new efforts to help the latter tap into the opportunities, the sustainability boom could bypass the countries furthest behind, leaving significant market gaps globally, with knock-on effects on the SDG financing gap. (Section 3.3 discusses in greater detail the potential consequences if investments are not redirected in support of developing countries.)

Shifting just 1% of global financial assets would be sufficient to fill the SDG financing gap in developing countries but this would rely on engagement with all actors in the financial system. The 2021 Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development called for a new way to invest in support of people and planet (OECD, 2020[17]). A shared public-private commitment to shift 1% of the USD 469 trillion in the global financial system in support of SDG alignment in developing countries would be more than sufficient to fill their SDG financing gap. Driven by the pandemic and rising geopolitical uncertainty, public and private sector actors are increasingly recognising that it is in their mutual interest to protect the long-term value of assets and mitigate global risks. Achieving the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement will require collective action at home and in support of the poorest countries. But a clear framework is required to guide actions along the SDG value chain from countries of origin to financial intermediaries and on to countries at greatest risk of divergence.

The next section assesses progress in advancing the sustainability and equity pillars of SDG alignment.

3.2. The sustainability boom is underway, yet market gaps remain

The recent sustainable finance boom is a result of the increased convergence of public and private interests in the management of long-term risks. While corporate social responsibility, in its early forms, and green investing are not new, efforts to design a quantifiable framework that encompasses dimensions of environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk are at an early stage. The international community has made significant headway in mainstreaming sustainable finance. However, with a proliferation of new initiatives comes the need to ensure their transparency and accountability. The sustainable finance boom has generated new demand for financing that does no harm and contributes to positive impact for people and planet and for new supply of rating systems, financing instruments, labels, etc. The sustainable finance market can be strengthened to avoid distortions, segmentation and missed opportunities to finance sustainable development in countries with lesser market regulation capacities.

To deliver the SDG impact required to reach countries most in need, frameworks and standards, including ESG ratings, can be strengthened at the global level. Heightened interoperability of standards across capital markets is needed to mitigate cross-border risks. While ESG frameworks seek to mitigate risks to long-term financial performance, the SDG targets and indicators framework provides metrics to assess global progress across the SDGs. ESG frameworks alone will not succeed in directing finance to leave no one behind and could even create significant barriers to access for countries with shallow financial markets. The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are necessary to guide financing where needs are greatest and manage global, cross-border and long-term risks and spillover effects.

The next subsection provides orders of magnitude of the volume of sustainable finance, the drivers of recent growth, and remaining barriers to promote transparency, accountability and SDG impact of financing to leave no one behind.

3.2.1. Public and private interests are converging towards a fast-growing market for sustainable finance in developed countries

The supply of investment labelled “sustainable” has registered unprecedented growth since 2018. Total sustainable investment grew by 15% in just two years, increasing from USD 30.7 trillion in 2018 to USD 35.3 trillion in 2020 (Figure 3.3).4 Of the nearly USD 100 trillion total assets under management in 2020 from institutional investors, asset managers and asset owners, sustainable assets make up 35.9% (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2021[18]).Canada has the highest share of sustainable investment within its market, representing up to 60% of total assets under management. The EU and the United States hold 80% of total sustainable investments. Anti-greenwashing and rules for labelling finance are becoming priorities, driven by the EU’s preparation of a new anti-greenwashing rulebook and the European Securities and Markets Authority roadmap, released in early 2022. These initiatives have resulted in fund managers pre-emptively removing the ESG label from USD 2 trillion of assets under management in the EU, which explains the decline in sustainable investment in the EU between 2018 and 2020.

Figure 3.3. Global sustainable investment in developed countries reached a new high in 2020 despite the global recession (USD trillion)

Note: The figure is based on currency exchange using 2019 prices. A regional comparison of growth rates is challenging due to a significant change in the definition of sustainable investment such as the new EU anti-greenwashing rulebook. Global Sustainable Investment Alliance reporting on financial assets includes sustainable investments such as impact investing and positive, sustainability-themed, norms-based and negative screening, ESG integration, and corporate engagement and shareholder action.

Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2021[18]), Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020, http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GSIR-20201.pdf.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the transition to a new era of global sustainable finance regulation that seeks to manage a broader set of cross-border risks over the long term. Sustainability of business and finance has shifted from a niche concern (e.g. fair trade, impact investment, corporate social responsibility projects) to the mainstream. By recent estimates, ESG assets could exceed USD 53 trillion globally by 2025, more than double the 2020 level (Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2022[19]). Just over half of stock exchanges, or 67 of the 120 stock exchanges tracked by the Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative, had published ESG reporting guidance for their listed companies in 2021 (Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative, 2022[20]). COVID-19 served as a wake-up call to public and private actors about the important impact of non-financial risk (i.e. global health) on financial performance. The line between sustainability risks and financial risks is blurred. Investors recognise the need to avoid future sources of market volatility (e.g. climate change, social unrest, geopolitical instability, etc.) and to seize investment opportunities. The cost of failing to align investment to the SDGs is also significant: 10% of global GDP could be lost without investment in gender equality, with the same estimated cost to GDP of not investing in biodiversity loss or not investing in addressing violence and armed conflict (BlackRock, 2021[21]).

Governments are doing more to establish common rules for more efficient, impactful and, for example, SDG-aligned sustainable finance markets. Taxonomies developed by the public sector are crucial to classifying environmentally sustainable economic activities and establishing common definitions for public and private actors. The EU has taken the lead in establishing the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Framework and regulation on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial sector to improve sustainability measurement and reporting. The EU taxonomy, which includes mandatory reporting by investors, aims to strengthen the sustainable finance market and shift investments where they can have greatest impact in support of a low-carbon transition, social objectives and economic prosperity (Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2022[19]). Fiscal policies, including tax and subsidy reform and carbon pricing, present an emerging opportunity to mobilise domestic resources while promoting a green transition. To succeed, carbon pricing must be implemented on a global scale to avoid shifting to third countries. Subsection 3.4.2 outlines discusses recent efforts to advance carbon pricing globally in greater detail.

ESG integration serves as a key barometer for firms, issuers and investors to assess and quantify the extent to which investments generate financial returns over the long term, while doing no harm and promoting positive returns. The OECD defines ESG investing as an approach that “seeks to incorporate environmental, social and governance factors into asset allocation and risk decisions, so as to generate sustainable, long-term financial returns” (Boffo, 2020[22]). According to recent estimates, ESG integration (USD 25.2 trillion) and negative/exclusionary screening (USD 15.9 trillion) represent the largest categories of sustainable investment by volume in 2020 globally. Sustainability-themed investment had the highest compound annual growth rate (63%) over 2016-20 (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2021[18]). Further, ESG integration provides a risk mitigation framework to assess the positive and negative risks that a firm’s financing and actions have across ESG criteria. However, ESG integration is currently carried out at firm or country level, which raises concerns of cross-border risks (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Deeper integration of environmental, social and governance criteria in financing can lessen cross-border risks

Financing that integrates ESG criteria can help mitigate financing risks and strengthen long-term financial performance. However, recent evidence of a correlation between stronger financial performance and higher ESG ratings remains uncertain. Factors such as lack of data and comparability of metrics (e.g. indicators beyond gender equality or CO2 emissions) currently hinder the establishment of a direct link between ESG scores and real-world SDG impacts such as job creation and investment in human capital in developing countries, etc.

Moreover, ESG frameworks could benefit from integration of the SDGs, including the global dimensions of cross-border and long-term risks and spillover effects. Current ESG frameworks tend to focus on evaluating firm or country-level activities. However, the assessment, particularly of the social pillar of ESG, does not adequately account for potential risks of leaving the poorest and most vulnerable behind. Rating agencies also lack consistent indicators that reflect impact on social considerations (Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2022[19]). One survey of 64 asset owners found that 39% lack best practices for assessing impact and 78% consider a lack of capacity to collect impact data as the main challenge (Global Impact Investment Network, 2022[23]). The following target areas illustrate common measures of a firm’s ESG performance:

Environmental. Evaluating a company’s environmental policies, practices and performance including:

positive – efforts to protect the environment, improvement of waste disposal and recycling

negative – use of resources and negative environmental impact such as excessive carbon emissions, pollution and water usage.

Social. Evaluating a company’s policies and practices towards employees, suppliers, customers and communities including:

positive – supporting diversity, employment, community development and gender pay equality

negative – signalling human rights violations and poor labour conditions due to insufficient health, safety and quality standards.

Governance. Evaluating a company’s corporate policies and procedures including:

positive – promotion of diversity, board composition, business ethics and reputational issues

negative – low business ethics, including bribery or corruption, and evaluation of executive compensation.

Source: Author adapted from J. P. Morgan (2022[24]), Sustainable investing: Environmental, social and governance (webpage), https://privatebank.jpmorgan.com/gl/en/services/investing/sustainable-investing/esg-integration.

Several factors are motivating governments to create incentives to move from assessing ESG risks to assessing broader SDG impacts across borders for people and planet. As governments recognise the importance of establishing the right incentives for the private sector to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, fund managers in turn are anticipating upcoming sustainability regulations and mandatory disclosure laws. For example, the United States recently recommitted to the Paris Agreement and if legislation to fulfil commitments is implemented, this could result in the removal of US direct subsidies for oil and gas companies. In addition, the EU has adopted a climate law aiming to reduce CO2 emissions by 55% of 1990 levels by 2030, signalling forthcoming incentives for sustainable and low-carbon investments. Several additional trends reflect the convergence of public and private sector actors’ interests in support of common, mission-driven, rather than risk-averse, sustainability objectives.

Drivers from the perspective of policy makers:

1. One driver is the desire to avoid costly setbacks due to global crises by promoting a paradigm shift to increase the positive impact of cross-border spillovers. The pandemic turned future risk into present-day reality. All governments were struck by the urgency to respond to a global crisis. The potential costly impacts of future risks (e.g. cost of forced population displacements, climate-related natural disasters, health crises, etc.) were brought into focus and have since reinforced the need for investments that seek to both mitigate the risk of future crises and deliver positive impact in support of the global goals.

2. A second driver is recognition of the economic advantages of net-zero economies and the need to manage the risk of stranded assets. Climate-compatible policy packages can increase GDP in the long term by up to 4.7% on average across the Group of Twenty (G20) by 2050, including through savings from climate-related costs that are averted (OECD, 2017[25]). Renewable energy projects represent the largest share of energy investment and are less costly than developing fossil fuels. In recognition of the potential economic benefits, net-zero commitments to date cover roughly 70% of global GDP and carbon emissions, with nearly a quarter of such commitments taking the form of legally binding pledges (IEA, 2021[26]). However, as discussed in section 3.3, fossil fuel dependency in many developing countries presents the risk of stranding financial assets and contributing to further fiscal and monetary constraints.

Drivers from the perspective of investors:

1. Interest in investing to address and protect against systemic risks, including protecting against value chain and/or resource disruption such as food price hikes, water scarcity, travel restrictions, etc. Governments are developing new mandatory and legally binding frameworks to promote a common understanding of the activities and types of financing that are considered sustainable and the impacts these may have on society. For example, the US Securities and Exchange Commission set out draft rules for mandatory harmonised climate-related disclosure in 2022. The pandemic has further accelerated the use of social and sustainable bonds linking use of proceeds to addressing social and environmental issues. Subsection 3.3.1. examines the emergence of green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds.

2. New growth and investment opportunities from the net-zero transition. However, the recent spike in oil prices is testing markets. Investors seek to secure the long-term value of assets by mitigating non-financial risk, including through decarbonisation of portfolios to support the green transition. According to the UN Environment Programme (2021[27]), 20% of all major companies have made a net-zero pledge of some kind. Asset owners, who can play a particularly important role to direct capital in support of a low-carbon transition, are stepping up commitments to address the systemic risks from climate change. For example, the UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, which includes 73 investors with USD 10.7 trillion in investments, released a protocol for investors establishing short-term, net-zero targets.5 However, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and subsequent spike in oil prices,6 major asset managers have rolled back commitments to decarbonise. For example, the world’s largest asset owner, BlackRock, with assets valued at USD 9.57 trillion in 2022, took action following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic to integrate the SDGs into its fiduciary duty as a means to strengthen the long-term economic interests of its clients. With the increased price of oil, BlackRock indicated that it would scale back commitments to invest in companies that end fossil fuel production, challenging the integrity of the SDG alignment of its allocation strategy (Fink, 2022[28]).

Despite the increasing convergence between public and private interests in sustainable finance, the transparency, accountability and impact of the global sustainable finance market continue to face challenges. The global dimension of recent shocks requires a multilateral approach to co-ordinate and implement new cross-border solutions. While business has long operated across borders, governments are reaching a turning point for global harmonisation of regulations and rules governing the sustainability of finance. As noted in Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021, without alignment of all actors along the value chain, the effect of any single action or actor will be limited. Better policies, taxonomies and standards are needed to align activities of all stakeholders in support of the SDGs. The next subsection identifies improvements needed to measurement frameworks and improve disclosure by the private sector.

3.2.2. Barriers including incompatible standards and definitions continue to impede sustainable finance on a global scale and the move from an ESG to an SDG paradigm

Moving from ESG to SDGs is more than semantics: Promoting financial sector alignment to SDG targets will be crucial to strengthen interoperability and global resilience to future shocks. A key difference between ESG and SDG sustainability ambitions is to expand risk assessment from firm level to global level. While the increase in the number of sustainability initiatives demonstrates growing demand for sustainable finance, the next challenge is to ensure that these initiatives are contributing to impact. If sustainable investment does not lead to impact, markets will lose credibility. Investors require confidence that labels are genuinely reflecting a portfolio’s relation to sustainability.

The proliferation of sustainability definitions coupled with a lack of data impede transparency and accountability of the impact of resources. There is currently no universally agreed definition of sustainability in financial or capital markets. The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance estimates sustainable investments total as much as USD 35.3 trillion. However, the UN Conference on Trade and Development and others, using a much narrower definition of sustainability, identify only USD 5.2 trillion assets under management as sustainable investment in 2021, an increase of 63% from 2020 (UNCTAD, 2022[29]). The International Organization of Securities Commissions, the global standard setter for securities market regulation, warns there is a lack of clarity about what ratings or data products intend to measure and lack of transparency about the methods used to produce the ratings (Jackson, 2022[30]). The lack of clarity was demonstrated when Morningstar removed the ESG label from over USD 1 trillion in managed funds that it alleged was misleading investors (Schwartzkopff and Kishan, 2022[31]). Recent studies by the OECD also show that climate-related metrics are not as strongly correlated with the environment pillar of ESG as are factors not directly related to a climate-friendly transition, such as market capitalisation or financing for disclosure reporting (OECD, 2022[32]). In fact, a high score on environmental criteria from certain providers can be positively correlated with higher CO2 emissions (OECD, 2022[32]).About 25% of self-declared green funds have an exposure to fossil fuels of more than 5%, and in some cases nearly 20%, which calls into question the greenness of these funds (UNCTAD, 2022[29]).

In addition, reporting standards are not interoperable across borders, which creates confusion among international investors and regulators. Recent sustainability standards published by the G20 International Sustainability Standards Board and existing voluntary standards across countries and regions (such as China's Green Industry Guiding Catalogue) create a patchwork of guidance for reporting globally. Some of these standards do not assess a company’s direct impact on the environment or society. For example, a study of five regions found that not all sustainability taxonomies include social criteria within the definition (OECD, 2020[33]). The risk of global market failure increases when assessment and costs of negative externalities, including social dimensions, are not integrated and harmonised into sustainable finance taxonomies in a comparable manner. For example, while a country’s industrial classification system may be consistent with national statistical data, it often is not compatible with classifications systems used in other countries (Ehlers, Gao and Packer, 2021[34]). Without interoperability, activities deemed sustainable in one country may not be considered as such in another country. This increases transaction costs for investors.

The lack of sustainable finance markets in developing countries is a missed opportunity to move from an ESG to an SDG paradigm. The SDGs, by definition, are universal in that they encompass all countries, developed and developing. Moving to a universal SDG paradigm can help ESG risk mitigation strategies integrate potential transboundary impacts from countries where the needs are greatest. There is a heightened likelihood that sustainable finance will bypass countries most in need in the absence of significant efforts to improve reporting capacities in countries with shallow financial markets. China and South Africa are among the only developing countries to have developed an ESG taxonomy, and South Africa’s taxonomy was only adopted in April 2022. Just 25 of 60 developing countries’ stock exchanges require ESG reporting (IEA, 2021[35]). Subsection 3.3.2 explores in greater detail the roadblocks facing developing countries to access and participate in sustainable finance markets.

Most ESG reporting frameworks seek to assess and quantify a company's sustainability performance – that is, the risks that are material to financial performance for investors – rather than assessing how a company risks impacting external considerations (double materiality or SDG impact). The draft European Commission Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive proposed a social taxonomy, or subset of the EU Environmental Taxonomy, that would reinforce the social and governance dimensions of ESG criteria by setting minimum mandatory social safeguards to mitigate risks to social and human rights violations (Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2022[19]). The EU social taxonomy would link a country’s SDG achievement or lack thereof to its private sector’s contribution to the SDGs. Subsection 3.3.2 examines the trade-offs of sovereign ESG ratings that present challenges to ranking a country’s ESG dimensions.

SDG labelling requires a broad range of data, meaning it poses potentially greater risks of green or impact washing than ESG labels. Gathering the data needed to avoid SDG-washing across the goals, and particularly social objectives, remains a significant obstacle. The SDG targets and indicators were first designed for implementation by governments, not firms and asset managers. This is evidenced by the distribution of sustainable bond issuances since 2014. For instance, environmental goals related to CO2 emission reduction have more accessible data for reporting. In another study, 46% of the 347 institutional investors surveyed indicated that social dimensions of ESG criteria are the most challenging to integrate into investment strategies (BNP Paribas, 2019[36]).A recent OECD survey of blended finance indicates that only 1% of surveyed financial assets under management were dedicated to gender equality as the main objective (OECD, 2022[37]). The use of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms provides a new tool for investors to harness big data to align investment standards. For example, BNP Paribas introduced the use of a new AI tool to assess both ESG risks and SDG impact (BNP Paribas, 2021[38]). However, automatised portfolio allocations, which use AI, could exclude developing countries on the basis of a lack of quality data needed for sustainability reporting. Self-reporting schemas must be fine-tuned to avoid increasing existing inequalities or misleading investors.

The next section examines the equity pillar of SDG alignment. A sustainable recovery cannot be achieved without an equitable and just transition that leaves no one behind.

3.3. The equity pillar: No sustainability without equity

The recovery will be neither sustainable nor resilient if the poorest are left behind. No single country can achieve SDG alignment as long as the risk of negative spillovers (in terms of securing global value chains, limiting temperature increase, etc.) exists in other countries. Despite great strides to secure a more efficient and impactful sustainable finance market, advances are limited mainly to major economies. If finance is to be sustainable on a global scale, it must be equitable. And if equity is unaddressed, financing gaps in the most vulnerable countries will be amplified and ultimately contribute to even greater setbacks over the long term. The COVID-19 pandemic and looming climate and environmental emergencies make clear the interdependence of countries and the high price of failure to co-ordinate globally.

Failure to progress towards achieving the equity pillar will make the sustainable finance market a missed opportunity to address growing inequalities and could lead to additional diversion of financing away from those most in need. The sustainable finance boom in HICs could have unintended consequences in lower-income countries if the barriers to sustainable investment are not addressed (UNCTAD, 2021[39]) (Cattaneo, 2022[40]). Subsection 3.3.2 highlights factors that impede access to sustainable finance in the poorest countries, which confront a vicious cycle of short-term emergencies such as climate, food, health and migration among others. Such crises simultaneously increase financing needs and decrease the availability of financing in these countries to invest in the SDGs – for example, by lowering sovereign credit ratings and prompting tighter terms and conditions of financing. As a result, those countries furthest behind could find themselves with even fewer resources and even greater financing setbacks to achieve the global goals.

In an interdependent system, it is imperative to mobilise investment in developing countries to achieve sustainability at home. As the COVID-19 and climate crises have shown, the SDGs are interconnected, and performance of every individual country is dependent on the performance of others. Growing global inequalities thus will also lead to other crises by weakening economic and societal resilience to shocks. For example, global forced displacement (driven by the war in Ukraine, persecution and human rights abuses) reached a new historic high in 2022, with more than 100 million people displaced – more than double the number in 2012 (UNHCR, 2021[41]). As public development finance is shifted to address the growing refugee crises within donor countries’ borders, there is a risk that less financing will be available to advance the SDGs across borders, in the poorest countries, contributing to a widening of the sustainable finance divide and heightening inequalities between countries.

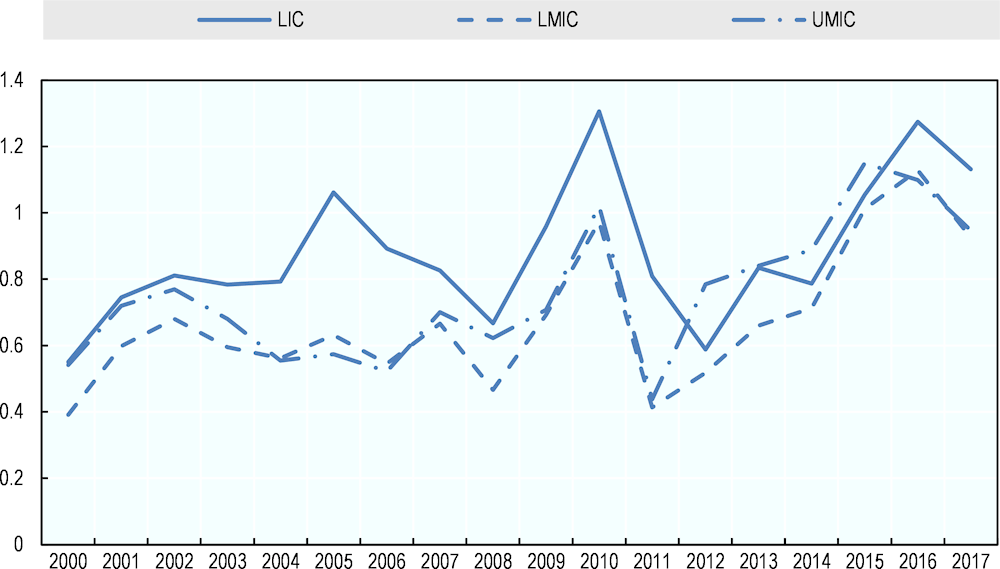

Avoiding future shocks, including the climate emergency, is not possible if major economies do not remove the barriers to access sustainable finance for those with the greatest climate and financial vulnerabilities. As many as 132 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty due to climate change by 2030 (Jafino et al., 2020[42]). Developing countries have contributed the least to climate change, yet they have lost 20-25% of cumulative GDP per capita since the turn of the 21st century due to temperature increase (de Brandt, Jacolin and Lemaire, 2021[43]). As shown in Figure 3.4, GDP per capita losses in LICs were on average 20% higher than in all middle-income countries. LICs have experienced the highest GDP per capita losses due to their geographical concentration in hotter climates, yet are the least prepared to carry out climate change adaptation and are the most vulnerable to climate-related shocks. Looking ahead, Russia’s war against Ukraine will magnify hunger and food insecurity in developing countries. This is particularly the case for LICs that are highly dependent on the agriculture sector, which is vulnerable to the impacts of temperature increase and biodiversity loss. Climate change adaptation financing will be increasingly needed in the poorest countries and population segments to avoid increasing pre-existing inequalities and poverty levels.

Figure 3.4. Low-income countries suffered the greatest economic losses due to temperature increase (percentage loss of GDP per capita annual growth)

Note: A sustained one-degree Celsius temperature increase lowers real GDP per capita annual growth by 0.74 to 1.52 percentage points, irrespective of levels of development. Country income groups are presented as an unweighted average of country-level data. Income categories correspond to 2019 World Bank classifications.

Source: Authors adapted from de Brandt, Jacolin and Lemaire (2021[43]), “Climate change in developing countries: Global warming effects, transmission channels and adaptation policies”, https://publications.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/wp822_0.pdf.

Achieving the 1.5°C limitation will not be possible if the world returns to pre-COVID-19 growth levels (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022[44]). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that, on its current trajectory, the world will exceed its carbon budget and warming could surpass 1.5°C by 2030. A country’s income per capita is an indicator of its greenhouse gas emissions per capita (Figure 3.5). Without decoupling CO2 emissions from economic growth and productive capacities and as developing countries grow, their CO2 emissions per capita could reach HIC levels in the next 70 years or by 2094.7 In 2094, developing countries could represent at least 84% of CO2 emissions, a doubling of current CO2 emissions per capita from 33 tonnes to 75 tonnes. To address the global CO2 imbalance and respective capacities to mitigate CO2 and adapt to climate change, a just transition should, according to recent estimates, allow the poorest nations an additional 20 years to reach net zero (Calverley and Anderson, 2022[45]). Developed countries must meet their CO2 reduction commitments in the short term and also deliver massive support to help promote sustainable growth paths in developing countries over the long term.

Figure 3.5. Based on current trajectories, the distribution of annual CO2 emissions per capita will shift significantly (percent share of global emissions)

Note: The figure shows annual CO2 emissions per person in HICs using the population in World Bank income categories in 2020. The scenario of no climate action estimates CO2 emissions per capita if all countries reach emission levels equivalent to those of HICs in 2020, but it does not account for other factors such as the current rate of emissions growth, population growth, new climate policies, technologies or mitigation strategies.

Source: Author adapted from Ritchie (2018[46]), Global Inequalities in CO₂ Emissions, https://ourworldindata.org/co2-by-income-region; Global Carbon Project (2022[47]), The Global Carbon Project (webpage), https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/; World Bank (2022[48]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

However, at current levels of external public financing, the low-carbon transition in developing countries will not be achieved. In 2020, total climate finance mobilised and provided by developed countries to developing countries amounted to USD 83.3 billion, an increase of 4% from 2019 (OECD, 2022[49]). This amount is less than the annual total of USD 150 billion required in 2020 to fill the gap left by potentially stranded assets in developing countries. Sub-Saharan Africa alone needs to mobilise USD 50 billion annually, or 30% of regional GDP in 2020, to address climate adaptation in agriculture, power and urban infrastructure (Tyson, 2021[50]). Access to climate or green funds by countries that need them most, such as small island developing states (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs), remains low at 2% and 17%, respectively between 2016 and 2020 (OECD, 2022[49]). Most climate development finance (80%) is spent on mitigation in middle-income countries in energy and transport infrastructure. Since the COVID-19 crisis, external financing by donors has been reallocated away from climate change adaptation in favour of domestic emergency response (Richmond et al., 2021[51]). African nations recently called for a tenfold increase in climate finance commitments, from USD 100 billion in public climate finance to USD 1.3 trillion in public and private finance annually, by 2030 (Rumney, 2021[52]). To achieve the equity pillar of SDG alignment, external public and private financing will be needed to narrow the growing climate financing gap for mitigation and adaptation, particularly in the poorest countries.

Short-term costs, if unbearable due to limited fiscal space or debt levels, could hinder spending in support of long-term benefits such as the guarantee of basic social protection. A paradox emerges as financing needs increase in developing countries. If developing countries were to raise the additional finance needed to achieve a low-carbon transition by 2060 exclusively through higher taxes and borrowing, household consumption in these countries could decline on average 5% per year, rendering developing country households around USD 2 trillion poorer each year between 2021 and 2060 (World Economic Forum, 2022[53]). In comparison, guaranteeing basic social protection across LICs, LMICs and UMICs is estimated to cost USD 1.1 trillion annually (Bierbaum and Schmitt, 2022[54]). While it is necessary for these countries to mobilise more resources to build back better and invest in long-term climate resilience, financing should not result in debt distress or reduced government expenditure in a “human-centred” and just recovery (such as investment in human capital) (International Labour Organization, 2021[55]). External financing solutions and instruments must be tailored to integrated national financing strategies – for example grants, debt swaps, domestic savings and investment among others – to ensure debt sustainability and long-term achievement of the SDGs. Options to provide technical assistance and ensure capacity building to access sustainable external financing solutions are further explored in section 3.4.

3.3.1. Opportunities for investment aligned to the Sustainable Development Goals in developing countries

The demand for sustainable investment in developing countries is on the rise. The COVID-19 crisis is driving progress in developing countries towards integration of sustainability initiatives and digitalisation to guide private investment (OECD, 2021[56]). The Indonesian G20 presidency identified GSSS bonds as crucial to mobilising resources for sustainability in developing countries (G20 Indonesia, 2022[57]). ESG investments in developing countries excluding China have tripled from 2020, amounting to USD 190 billion in 2021 (Gautam, Goel and Natalucci, 2022[58]). This growth underscores the need for increased transparency and accountability in the taxonomies and definitions underpinning the assessment and quantification of investments that qualify as sustainable. Ensuring operational guidance on sustainable finance classifications as a global public good and ensuring these are freely accessible is a first step to meeting the demand in developing countries while maintaining the integrity of sustainable finance markets globally (Imperial College Business School, 2021[59]).

Investment in renewable energy infrastructure represents a growing opportunity in emerging market economies. Investment in clean and renewable energy infrastructure is needed in developing countries. An estimated USD 4 trillion is required annually by 2030, with developing countries needing 40% of that amount and 70% invested by the private sector (IEA and Imperial College London, 2022[60]). Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an important source of renewable energy investments. It already accounts for 30% of new investments in renewable energy globally and will be especially important in developing countries where demand for energy is expected to grow most rapidly and where financing constraints are greatest (OECD, 2022[61]). In Africa, three countries – South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria – have reached levels of FDI in clean energy comparable to European peers and are likely to supersede them in the near future in terms of their market share. In terms of their share in global greenfield FDI stock in renewable energy, South Africa (1.8%), Egypt (1.9%) and Nigeria (1%) are comparable to France (1.7%), Canada (1.4%) and Italy (1%).

The cost efficiency gains of decarbonisation in developing countries provide further incentives for investors seeking to minimise environmental impacts. As portfolios shift in favour of low-carbon investments, the incentives for investors to allocate financing to markets where CO2 mitigation is least costly will increase in tandem. For example, the average cost of eliminating one tonne of carbon in developing countries is estimated to be about half that in advanced economies, thanks to new low-carbon projects and technologies that are less costly than retrofitting and adapting existing projects (IEA, 2021[35]). Investors seeking to reduce CO2 emissions at minimal cost can invest in developing countries where they benefit from such efficiency gains.

In addition to climate mitigation, private sector market creation for climate adaptation and resilience in the poorest and most vulnerable developing countries can generate tremendous savings. Financing for climate change adaptation and resilience can generate large returns in terms of avoided costs and social and environmental benefits: for instance, investments of USD 1.8 trillion for these purposes result in USD 7 trillion in savings (Tall et al., 2021[62]). However, mobilising such financing remains challenging in developing countries due to these projects’ small size and lower profitability (OECD, 2021[63]).Adaptation projects often require financing of public goods that generate low revenues and the use of loan-based instruments that require repayment (and thus create further debt risks). While investment in climate adaptation is trending upward, private sources currently provide less than 2% of adaptation finance, or about USD 500 million (Tall et al., 2021[62]). Better estimates of the quantitative value of climate risks and losses averted – that is, how to monetise the benefits generated by adaptation and resilience finance – are needed to incentivise private sector engagement.

More investment in a human-centred recovery, or social protection, could generate economic gains in the poorest countries. Less than half of the world’s population has access to social protection, meaning access to a guaranteed level of healthcare systems and income security needed to eradicate poverty and shield the poorest during economic downturns (Durán-Valverde et al., 2019[64]). The poorest countries have the lowest access to social protection. For example, old age pension funds have only 15% coverage rates in LICs but 90% coverage in UMICs (Durán-Valverde et al., 2020[65]). However, eight case studies in developing countries show that countries with lower GDP per capita generate higher rates of economic growth from the same investment in social protection. Investing 1% of GDP in social protection generates a multiplier effect on GDP of between 0.7 and 1.9 (International Trade Union Confederation, 2021[66]). Domestic resources in developing countries remain insufficient to generate the financing needed for such investments, despite the potential economic gains. Recent estimates show that the financing gap in 2020 to achieve universal coverage of social protection (including healthcare) was estimated at USD 1.9 trillion, or roughly 4% of GDP in the 134 developing countries and territories studied (Durán-Valverde et al., 2020[65]). Subsection 3.4.2 identifies options to raise external financing, including innovative financing instruments that increase fiscal space needed for social protection investments.

The following subsection identifies the roadblocks to tapping into growing investment opportunities in the sustainable finance market in developing countries.

3.3.2. Barriers to access sustainable finance in the poorest and most vulnerable countries could lock in the Great Divergence

A paradox has emerged with the profusion of sustainable finance, which ultimately is not needs based. While an increase in the number of actors and financing instruments aiming to support the SDGs provides opportunities to mobilise more financing, it also adds a layer of complexity and risk that add to difficulties of access to countries most in need of financing. Research by the OECD found that developing countries have more than 1 000 instruments to choose from to finance their development. These instruments imply varying terms, conditions and technical expertise, which can create barriers to access. For example, SIDS face many challenges to access vertical climate funds due to low return on investment for CO2 reduction and a lack of administrative and human resource capacities to apply for and carry out large projects (Morris, Cattaneo and Poensgen, 2018[67]). With small populations and limited skills and technical capacities to manage the projects adequately, SIDS’ access to green funds is slowed. For example, the Green Climate Fund disbursed commitments with a two- to four-year lag in SIDS. The Climate Investment Funds and the Global Environmental Facility had longer commitment delays of up to eight years (OECD, 2022[68]).

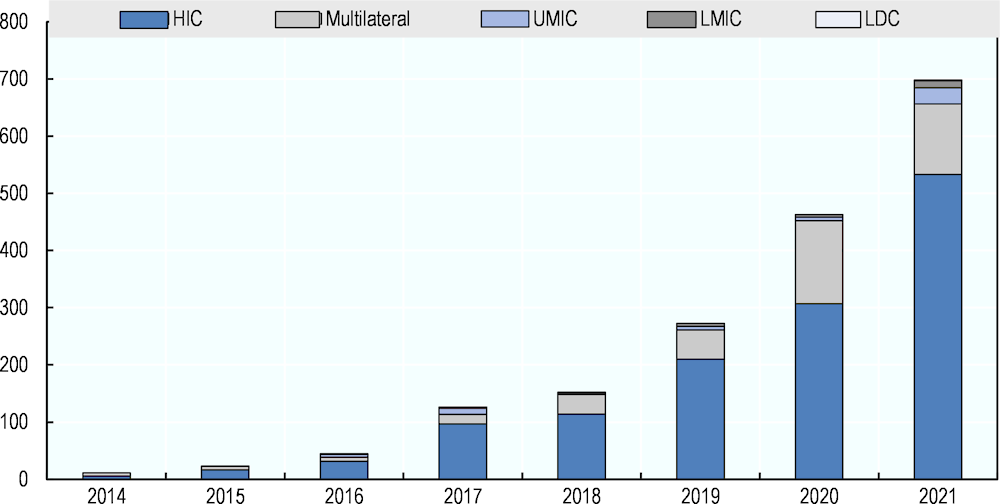

Many developing countries struggle to build a pipeline of bankable sustainable projects for environmental and social impact. Despite the growth in investments, 97% of the estimated USD 1.7 trillion in total sustainable investment funds are held in HICs (UNCTAD, 2021[69]). As shown in Figure 3.6, all ODA-eligible countries account for less than 7% and LDCs for less than 1% of cumulative total GSSS bonds issued since 2014. To date, there have been 16 green bond issuances in sub-Saharan Africa, representing 1.5% of total global bonds by number and less than 0.3% by value (Tyson, 2021[50]). Shallow financial sector development in the poorest countries, as noted previously, is one of the key factors hindering sustainable finance market creation. Additional factors related to the risk-return profile of developing countries, including financial and climate risk, create further impediments to access financing.

Figure 3.6. Green social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bond issuances by HIC and multilateral agencies have increased significantly (EUR billion)

Note: Country classifications are based on the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) ODA-eligibility list (2021).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Luxembourg Stock Exchange (2021[70]), DataHub, https://lgxhub-premium.bourse.lu. (OECD, 2022[71]).

A long-standing lack of data to report on the most basic sustainability criteria in developing countries – economic growth – increases the exclusionary risk. Relevant data to assess ESG criteria can be costly to compile and can require technical competencies to produce accurately. Without complete and timely data, developing countries face further exclusion and lower scores. For example, the World Bank found that about 90% of a country’s sovereign ESG score can be explained by a country’s national income. However, the base year for which GDP is calculated in many developing countries is not updated in a timely manner (at least every five years), which contributes to a lag in income level in the poorest countries. One example is Ghana: its GDP was under-reported by 60% until 2010, when the country changed its base year and transitioned from the low-income to lower middle-income category (Moss and Majerowicz, 2012[72]). Presently, it is estimated that 7% of the global economy is missing from GDP data, mainly for developing countries with low national statistical office capacities and large informal economies,8 such as those in sub-Saharan Africa (Ritchie, 2021[73]; OECD/ILO, 2019[74]).

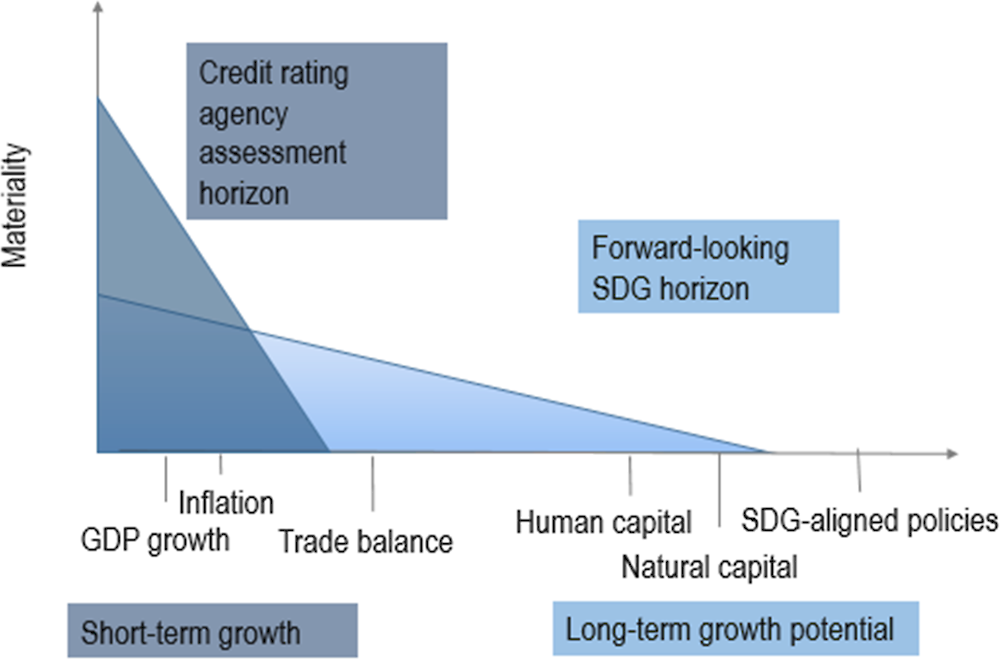

Recent crises demonstrate that sovereign credit ratings favour short-term financial risk assessment to the detriment of a country’s long-term efforts to mitigate ESG risks or achieve the SDGs. The incentives imposed by credit rating agencies (CRAs) can force developing countries to choose between investment grade credit scores and investment in sustainable development over the long term. While ESG ratings issuers often consider long-term risk mitigation strategies and growth potential, CRAs focus their evaluation mainly on short-term factors such as GDP, climate vulnerability, debt distress, inflation, etc. During the pandemic, several developing countries were penalised for heightened spending on public services, including for emergency health support, while other countries chose not to borrow for emergency relief to avoid credit downgrades. Sovereign credit rating downgrades increase borrowing costs and can contribute to economic recession. During COVID-19, developing countries, many of which were already rated non-investor grade (BB+ or lower), may have faced a perception premium or downgrades, despite having an improved economic outlook in the country prior to the COVID-19 crisis (Fofack, 2021[75]). While developed countries’ sovereign credit ratings remained stable throughout the crisis, more than 56% of rated African countries were downgraded in 2020, significantly above the global average of 31.8% (Fofack, 2021[75]). Of the seven sovereign defaults that occurred in 2020, three (Argentina, Lebanon and Zambia) were already rated in the lowest rating category of CCC/CC. Sri Lanka recently defaulted on debt owed to external creditors valued at roughly USD 50 billion due to rising inflation and energy prices. In addition, since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the credit scores of oil commodity-dependent countries improved as oil prices increased, creating further barriers to transition to low-carbon pathways.

Soaring energy prices raise the value of stranded assets and threaten setbacks to clean energy finance in developing countries. Commitments to divest from carbon-intensive sectors were accelerating before the war, including commitments to end public export guarantees for fossil fuel projects and DAC members’ commitment to end new ODA for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021 (OECD, 2021[76]). Divestment decreases the value of assets by signalling a decrease in demand. As a result, clean energy financing needs in developing countries by the end of the 2020s could increase from USD 150 billion to USD 1 trillion, particularly for coal-fired power plants.9 Developing countries hold 89% of the total capital globally at risk of being stranded.10 Nearly 50% of sub-Saharan Africa’s export value is composed of fossil fuels, or roughly USD 120 billion in 2019 (World Bank Group, 2020[77]). However, as energy prices increase due to the effects of the war, the value of energy assets also increases to the benefit of energy export-dependent countries. Promoting continued commitment to the clean energy transition will be challenging in countries that are currently benefitting from the increase in export value.

As developing countries’ access to international financial markets narrows, there is a greater risk of locking in pre-existing political and social instability. The drive to build markets for sustainable finance cannot succeed without sound governance and public institutions. Sound governance is needed to ensure quality regulatory policy, protect against corruption and to ensure rule of law. Financial intermediaries, such as CRAs, assesses sovereign credit ratings according to the World Bank Governance Indicators for political risk assessment, (Fitch Ratings, 2021[78]). However, LICs, since 2015, rank lowest across all indicators of sound governance. In the area of political stability, LICs even regressed (World Bank, 2022[48]). The mounting wave of global inequity, if left unaddressed, will lock in a Great Divergence that eliminates the possibility of achieving the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs.

A new paradigm is needed that ensures incentives to allocate and commit a greater share of sustainable financing in support of countries at greatest risk of SDG setbacks. Current capital market incentives are not optimal to addressing capital shortages in developing countries. Capital markets are weighted to direct flows towards countries with the least shortages: For example, 65% of the MSCI emerging market index is held by only 3 of 26 countries covered) (Principles for Responsible Investment, 2022[79]). The cost of borrowing in the poorest countries has increased significantly, while spending towards the SDGs remains constrained. Increased vulnerability due to recent shocks brought on by COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine has compounded pre-existing financial and climate risks. Delivering the equity pillar of SDG alignment will ultimately require that financing reaches the countries where it is most needed. A paradigm shift is required to create global incentives for investment to be directed to countries that seek to align financing to the SDGs, despite the risk-return profile.

3.4. Actions to avoid the Great Divergence

Collective action by actors in all countries is urgently needed to avoid the great SDG divergence and enforce the equity pillar of SDG alignment. The supply of and demand for sustainable finance and recovery spending have reached a record high in OECD countries. However, developing countries hardest hit by successive crises and where demand for sustainable finance is greatest are struggling to access the sustainable finance market and to mobilise domestic resources. Strengthening the market for sustainable finance requires a sustainable finance equilibrium that balances both pillars of SDG alignment – sustainability and equity. As the SDG financing gap increases in the poorest countries and short-term financing needs arise, the risks of beggar-thy-neighbour policies also rise, meaning policies in one country that rely on short-term solutions to resolve a domestic economic problem – deceleration of the low-carbon transition, for instance, or protectionism – could harm other countries’ economic welfare. Without swift action to finance the poorest and most vulnerable, the next waves of crises will be all the more harmful for people, planet and prosperity.

The war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic open a window of opportunity to “reset” market incentives in favour of the SDG paradigm (World Economic Forum, 2020[80]). The geopolitical shifts in the wake of the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine shook the global economic system. These shocks could be an impetus to set new rules in favour of a fairer economic system. Following the 2008-09 global financial crisis, multilateral groups such as the G20 took the lead to carry out major reforms to strengthen the stability of the international financial system and reduce future risks within it. One potential outcome of the pandemic and the war could be that common geopolitical and values-based interests align and result in a “great reset” of capitalism, led by governments to reduce strategic vulnerabilities and promote the social and environmental benefits of investment (e.g. moving from an ESG to SDG paradigm). For example, a new value system is emerging that could reroute trade and commerce to embed environmental and social concerns into global value chains that contribute to strengthening resilience to the benefit of a low-carbon transition and achievement of the SDGs in the poorest countries (OECD, 2021[16]; Lagarde, 2022[81]). Diversification of supply chains, including at the frontier in developing countries, provides a means to strengthen resilience to future shocks.

To save the SDGs, simultaneous actions are needed all along the SDG investment value chain from country of origin to financial intermediaries to countries at risk of divergence. The 2021 Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development and OECD-UNDP Framework for SDG Aligned Finance call for mutually reinforcing actions in support of alignment of all actors along the investment value chain (OECD/UNDP, 2020[82]). But, as noted here, new taxonomies and standards to define and assess sustainability are only effective and impactful if they are interoperable and enforceable across borders. For reforms by any one country or region to succeed, a global agenda is required to identify where the international community can take collective action to correct misalignment and avoid shifting of activities beyond borders (for instance, to avoid a race to the bottom). Action is needed along the value chain to guide all actors in countries at risk of divergence (e.g. strengthening domestic sustainable finance markets and strategies) and financial intermediaries (e.g. risk management and innovative instruments) as well as actors in countries of origin (e.g. coherence of policies and combatting SDG-washing).

The next subsection discusses measures to narrow the SDG financing divide and deliver the sustainability equilibrium for SDG alignment, focussing first on recommended actions in support of countries at risk of divergence (including how the international community can provide support) and then on support by countries of origin (e.g. promoting policy coherence) and by financial intermediaries.

3.4.1. Actions in support of countries at risk of divergence

Without external support from developed countries, developing countries will not benefit from the sustainable finance boom and the Great Divergence will accelerate. Faced with mounting, immediate financial and fiscal pressures due to the war in Ukraine and COVID-19, developing countries are unable to mobilise the resources needed to finance short-term emergency responses without sacrificing spending for long-term resilience. As a result, developing countries require external support to reinforce domestic sustainable finance markets, strengthen domestic revenue mobilisation and attract sustainable external finance. Burgeoning sustainable finance markets are largely concentrated in developed countries. For these markets to be sustainable, they must be equitable – that is, they must deliver sustainable financing in countries at greatest risk of falling behind. The following are recommendations for action in support of countries at risk of divergence.

Support domestic resource mobilisation to increase fiscal space in developing countries

Developed countries can invest in domestic resource mobilisation (DRM) to alleviate the fiscal and credit crunch in developing countries. In recent years, there has been growing concern about fiscal vulnerabilities as debt levels become unsustainable. As noted in Chapter 2, donors have made important strides towards the target of USD 441.1 million in ODA to support DRM that was set by the Addis Tax Initiative in 2015, and maintained in its 2025 Declaration. Bilateral and multilateral actors could deliver more and better technical assistance and capacity building for stronger global sustainable finance markets and tax systems in the poorest countries. One initiative that helps bring technical tax expertise to support DRM in developing countries is the joint OECD-UNDP initiative, Tax Inspectors Without Borders, which provides a mechanism to bring experienced serving tax officials from one country to work alongside officials in a developing country administration on live cases. To date, the initiative has resulted in over USD 1.7 billion in increased revenues in developing countries, with a return on investment of 127:1.

Donors can also align support to national strategies such as Medium-Term Revenue Strategies to ensure that DRM targets SDG alignment. Demand is growing for support in specific areas to collect more and better revenues, such as digitalisation of tax administrations and tax system reform to both address inequality, and for support related to specific SDGs (e.g. on health and social protection). DRM strategies, such as MTRS, enable donors to align support to country-owned plans, with clear priorities and sequencing for reforms. Ideally, DRM strategies will be a part of broader integrated national financing frameworks (see below) to ensure the DRM strategy is targeting SDG alignment. Major economies can help by providing peer learning and technical assistance to reap the benefits of DRM reform. A US Agency for International Development (2016[83]) case study found that by rebuilding basic infrastructure, restoring public service and introducing modern digital tax systems, development partners could support developing countries, including fragile contexts, to improve revenue-to-GDP ratios. An example cited in the study was Rwanda, which succeeded in increasing its revenue-to-GDP ratio from under 10 percentage points in 2000 to about 16% in 2016 with the support of the United Kingdom.

Developed countries can help developing countries implement country-led carbon pricing policies to generate additional domestic revenue aligned to a just and sustainable transition. While revenue potential varies across countries, developing countries on average could generate revenue equivalent to about 1% of GDP if they set carbon rates on fossil fuels equivalent to EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 (OECD, 2021[84]). In developing countries, where 70% of all employment is informal, carbon pricing is an important policy lever as direct taxes on personal or corporate income are more challenging to collect (OECD/ILO, 2019[74]). Peer-to-peer learning can help developing countries implement best practices to ensure that carbon pricing is part of a suite of climate actions and policies for equitable and long-term sustainable economic development. For example, Egypt has demonstrated successful fossil fuel subsidy reform that protects vulnerable households and encourages private sector development. Subsection 3.4.2 further explores the importance of policy coherence of actions by countries of origin and highlights the potential of a global framework for carbon pricing.

Developed countries can strengthen support for debt-to-SDG swaps. A long-standing sustainable finance option, debt-to-climate swaps allow bilateral and multilateral actors to carry out debt forgiveness or restructuring with developing countries, thus freeing up financing that can then be used for SDG action (Thomas and Theokritoff, 2021[85]). For example, a debt swap worth USD 2.9 million in 2012 was carried out between Italy and the Philippines, and the targets of the liberated financing included poverty reduction. However, this option is most effective in countries that are not in debt distress and are able to service their debt. A country that is unable to service its debt will also be unable to redirect such service costs to finance SDG action. Traditionally, such swap arrangements are carried out between official creditors and debtors. However, more recently, private sector actors have engaged in purchasing climate swaps. For example, Belize issued a debt-for-nature swap equivalent to its entire external commercial debt stock of USD 553 million, or 30% of its GDP, with the support of the Nature Conservancy; the US Development Finance Corporation, which provided insurance; and Credit Suisse, which secured an investment grade rating from Moody’s (Owen, 2022[86]). Future efforts could seek to engage the private sector in investing in climate change adaptation and mitigation debt swaps in exchange for carbon emission offsets.