This case study presents a practical example of international regulatory co‑operation by means of the OECD-based co-operation programme for chemical safety. The case study presents recent data from a cost-benefit analysis of the programme, showing a yearly annual net benefit of more than EUR 300 million for all participant countries.

International Regulatory Co-operation in Competition Law and Chemical Safety

2. OECD’s Environment, Health and Safety Programme

Abstract

Today, OECD governments have significant and comprehensive regulatory frameworks for preventing and/or minimising the health and environmental risks posed by chemicals. The objective of these frameworks is to ensure that chemical products already on the market are safe or managed in a safe way, and that new ones are properly assessed before being placed on the market. This is done by testing the chemicals, assessing the results, and taking appropriate action. Such a framework, while rigorous and comprehensive when implemented, is very resource-intensive and time-consuming for both governments and industry.

For instance, the cost for a pesticide company to test one new active ingredient for health and environmental effects is approximately EUR 21.5 million, and the resources needed for a government to review and assess the data is approximately 1.95 person-years (OECD, 2019[1]). As many of the same chemicals are produced in more than one OECD country (or are traded across countries), different national chemical control policies can lead to duplication in testing and government assessment, thereby wasting the resources of industry and government alike. Different national policies can also create non-tariff or technical barriers to trade (TBT) in chemicals.

The World Trade Organization has estimated that between 1998 and 2010, there have been approximately 32 environment-related TBT specific trade concerns: 10 deal with control of hazardous substances, chemicals and heavy metals (WTO, n.a.[2]).

In 2018, the OECD’s Trade and Agriculture Directorate issued a working paper demonstrating that, on average, the cost (ad valorem equivalent) of technical barriers in chemicals was 9.3% of the unit value (OECD, 2018[3]). As outlined in (OECD, 2019[1]), further preliminary evidence from OECD research indicates that trade agreements that include mutual recognition and harmonisation of TBT measures, including mutual recognition of TBT conformity assessment procedures, have a positive influence on chemical trade flows, presumably by reducing trade costs associated with these non-tariff measures. Over the period 2015-17, as much as 26% of specific trade concerns raised in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Technical Barriers to Trade Committee referred to measures citing environmental protection among their objectives. Of all the environment-related measures identified in notifications to the WTO between 2009 and 2016, 18% had to do with either “chemical, toxic and hazardous substances management” or “ozone layer protection”. Half of these were TBT measures. Therefore, there are opportunities to improve TBT issues related to chemicals.

While all countries have the right to set their own levels of environmental protection, consistent with international obligations, such differences in regulations and test standards may discourage research, innovation and growth – as new research and products may only be accepted in the country or countries which apply the same test standards – and they may increase the time it takes to introduce a new product onto the market. They can also, when inappropriately or inconsistently implemented, lead to inefficiencies for governments, because authorities cannot take full advantage of the work of others which would help reduce the resources needed for chemicals control.

OECD’s Environment, Health and Safety (EHS) Programme has been working for 50 years, through international regulatory co-operation, to harmonise chemical safety tools and policies across jurisdictions and to share work on chemical assessments and common problems with the aim of minimising risks posed by chemicals and reducing non-tariff barriers to trade. The development and implementation of the Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system – under which chemical safety data developed using OECD Test Guidelines and OECD principles of Good Laboratory Practice in one adhering country must be accepted in all adhering countries – underpins much of this work. The MAD system is the mechanism which provides the framework for regulatory co-operation and is the focus of this case study. Currently, there are seven non-OECD member countries that are full adherents to MAD: Argentina, Brazil, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa and Thailand.

Main characteristics of the IRC under consideration

Actors involved

The OECD’s Chemicals and Biotechnology Committee (and its 13 technical sub-bodies) carry out the work of the EHS Programme. In member countries, OECD government representatives (including the European Commission) from various ministries or agencies (health, labour, environment, agriculture, etc.) work on OECD projects at the national level. In addition, experts from the chemicals industry, academia, labour, environmental and animal welfare organisations, and several partner economies participate in projects and meetings. These include, in particular, provisional and full adherents to the Council Acts on MAD: Argentina, Brazil, India, Malaysia, South Africa, Singapore and Thailand. The OECD also co‑operates closely with other international organisations, most notably in the global effort to implement the recommendations of the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED, Rio de Janeiro, 1992) and the Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD, Johannesburg, 2002). The OECD participates, along with eight other UN organisations involved in chemical safety, in the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC):

The OECD co-ordinates with individual IOMC IGOs based on topics or interest and expertise. This can take the form of joint workshops, joint expert groups, or both organisations working together on a publication. In general, each organisation takes the lead when a topic falls within their specialised expertise (e.g. UNITAR and training). Joint work with UNEP includes, for example, the areas of green and sustainable chemistry or the risk management of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances. In addition, the OECD has a long-standing co-operation with the WHO in the field of human health hazard and risk assessment. Similarly, the OECD works jointly with FAO in the fields of pesticides, food safety and biotechnology, and partners with ILO and UNITAR on the implementation of the UN Globally Harmonised System of Classification and Labelling.

In addition, at times, the OECD work lays the initial groundwork for broader international consensus on chemicals management. For instance, in 1984, OECD countries agreed that when exporting a chemical considered hazardous from an OECD country, the importing country should be informed. This principle was laid down in the 1984 Council Recommendation, and eventually constituted the basis for UNEP and FAO to develop the Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Procedures in 1998 (SRC, 1998[4]).

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from chemicals that remain intact in the environment for long periods, become widely distributed geographically, bioaccumulate in humans and wildlife, and have adverse effects to human health or to the environment. Some per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) compounds have been restricted in the European Union, United States, Canada, Australia and other countries and several groups of PFAS chemicals have been included as new POPs under the Stockholm Convention. The OECD convenes a Global PFC Group to share regulatory approaches for management of PFAS substances, support a shift towards safer alternatives and improve technical understanding of PFAS issues. The group, which extends beyond the OECD member countries, in collaboration with UNEP, is also working to improve the outreach to developing countries where the production and use of PFAS has grown.

OECD’s EHS Programme is also actively involved in the implementation of the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) which bring together governments from more than 150 countries and many stakeholders to support the achievement of the goal agreed at the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development of ensuring that, by the year 2020, chemicals are produced and used in ways that minimise significant adverse impacts on the environment and human health. This goal was not met by 2020 and since 2017, the OECD is involved in the development of the successor to SAICM.

Intended objectives

The objectives of the MAD system are as follows:

By accepting the same test results OECD-wide, unnecessary duplication of testing is avoided, thereby saving resources for industry and society as a whole.

Non-tariff barriers to trade, which might be created by differing test methods required among countries, can be minimised.

The use and suffering of laboratory animals needed for toxicological tests is greatly reduced, which is a significant contribution to animal welfare.

By establishing the same quality requirements for tests throughout OECD, a level playing field for the industry is enabled.

The MAD system opens opportunities for countries to work together in the EHS Programme on issues of common concern. By using the results from the same test methods for making safety assessments, mutual understanding among countries about chemical safety assessment and resulting risk management is greatly increased. This allows countries to share work on assessing chemical safety and consider options for managing chemical risks.

Forms that the co-operation is taking:

The principal tools for harmonisation are a set of three OECD Council Acts which make up the OECD Mutual Acceptance of Data system, including its OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals and Principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP):

The 1981 Council Decision on MAD states that data generated in a Member country in accordance with OECD Test Guidelines and Principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) shall be accepted in other Member countries for assessment purposes and other uses relating to the protection of human health and the environment.

The 1989 Council Decision-Recommendation which requires the implementation of the characteristics of national compliance programmes for GLP also deals with the international aspects of GLP compliance monitoring. It requires designation of authorities for international liaison, exchange of information concerning monitoring procedures and establishes a system whereby information concerning compliance of a specific test facility can be sought by another Member country where good reason exists.

The 1997 Council Decision which sets out a step-wise procedure for non-OECD countries to take part as full members in this system.

The binding nature of these Acts, particularly the 1981 Council Decision, ensures that all countries abide by the requirements to accept data from other OECD members, and non-members who also adhere to these Acts. In general, most countries adopt the OECD Test Guidelines and OECD Principles of GLP into national regulations, either verbatim or with minor, non-substantive changes. With respect to national GLP compliance programmes, OECD’s programme of continuing periodic on-site evaluations of members provides for an on-site team, composed of inspectors from other OECD countries, to evaluate each Monitoring Programme every ten years. Following discussion in the Working Party on GLP on the results from the on-site evaluation, a final report, including the conclusions and any recommendations agreed by the Working Party, will be prepared for use by GLP Compliance Monitoring Programmes in member countries in the framework of MAD. Finally, industry is encouraged to notify the OECD Secretariat if one country rejects a study from another country, conducted under the MAD system. Industry has also been provided access to a password-protected site to describe issues of dis-harmonisation across countries in the way they implement the GLP Principles. The Working Party on GLP will evaluate these comments and suggest a path forward.

By making the system accessible to non-member countries who adopt the same test methods and quality standards for chemical safety testing as OECD countries, the same level of protection of health and the environment is able to be obtained. Access to markets is further enhanced by harmonisation and mutual recognition of standards for development of safety data. As a result of the MAD system, countries have confidence in the quality and rigour of the laboratories that generate the test data and the results from such testing, which is particularly important in many EHS activities (e.g. work on assessing the hazards of chemicals) in which countries work together to develop chemical assessments based on agreed data.

Functions being co-ordinated

The EHS Programme focuses on the following areas of co-ordination:

The MAD System

Harmonisation: implementation by OECD countries and additional adherent countries of the OECD’s Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) system – including the development and updating of OECD Test Guidelines and Principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP).

EHS work made possible because of the MAD system

Development of risk assessment methodologies: given the harmonisation of the test methods and GLP, countries can also collaborate on the development of hazard and exposure assessment methodologies, such as for assessing the risks of the combined exposure to multiple chemicals or the development of computer models to predict the toxicity or behaviour of chemicals.

Emerging policy issues: the application of OECD Test Guidelines is also the central tool for addressing the risks of new and emerging materials, such as nanomaterials and advanced materials. The EHS Programme is adapting the OECD Test Guidelines so that they are applicable to these kinds of new and innovative materials, thereby expanding the MAD system.

Harmonisation: Another role for the EHS Programme is to harmonise industry dossiers – based on chemical test data – and review reports for pesticides registration.

Exchanging technical and policy information: the EHS Programme acts as a forum for countries to exchange technical and policy information. By discussing their chemical control policies together, countries tend to develop similar policies and regulations and have greater confidence in each other’s systems. In this way, not only are government resources saved, but products can also be brought to market faster. Finally, governments have access to the experience of the many scientific and policy experts from governments, industry, non-governmental organisations and academia who participate in the work of the EHS Programme.

Outreach: the OECD’s share in world chemical production is decreasing as non-OECD economies – particularly Brazil, India, Indonesia, the People’s Republic of China, the Russian Federation and South Africa – develop their chemical sectors. Greater international co-operation is needed with these economies to build capacity, share information and ensure that new national chemical management systems do not lead to duplicative work or conflicting regulations and new trade barriers. The OECD’s EHS Programme has a proactive outreach strategy to encourage the participation of partner countries in the work of the programme and to allow them access to technical and policy discussions and documentation. Of particular importance is opening the MAD Council Acts to non-members who wish to adhere to the 1981 Council Decision.

Short history of the development of the IRC

Triggers

Over the last four decades, there have been four principal drivers for International Regulatory Co-operation by OECD in the field of chemical safety. One, the chemicals industry – which includes industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, biocides, food and feed additives and cosmetics – is one of the world’s largest industrial sectors and many chemicals are produced and traded internationally.1 Thus, international co‑operation on chemical safety was seen as a way to avoid non-tariff trade barriers due to varying regulatory requirements. As many of the same chemicals are produced in more than one OECD country (or are traded across countries), different national chemical control policies can lead to duplication in testing and government assessment, thereby wasting the resources of industry and government alike. Two, releases of chemicals during production and use can travel across national (and sometimes regional) borders and thus, international co-operation is essential for a more comprehensive management of risks. Three, OECD countries, in general, follow the same approach to the assessment of chemicals, and thus there are economic efficiencies if countries can work together on such assessments. Four, through OECD Council Acts there was a possibility to make commitments among countries which are legally (decisions) or politically (recommendations) binding. This level of political engagement that can be achieved through the OECD and the peer pressure that can be applied to help ensure implementation of agreements, are crucial instruments to make sure that countries will follow up on harmonisation arrangements.

OECD’s IRC work in the field of chemical safety began in 1971 with a focus on specific industrial chemicals known to pose health or environmental problems, such as mercury or CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons responsible for depleting the ozone layer). The purpose was to share information about the risks of these chemicals and to act jointly to reduce them. One of the important achievements of the early years was the 1973 OECD Council Decision to restrict the use of polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs). This was the first time concerted international action was used to control the risks of specific chemicals. By the mid-1970s, however, it became clear that concentrating on a few chemicals at a time would not be enough to protect human health and the environment. With thousands of new chemical products entering the global market every year, OECD countries agreed that a more comprehensive strategy was needed. The OECD therefore began developing harmonised, common tools that countries could use to test and assess the risks of new chemicals before they were manufactured and marketed. This led to a system of mutual acceptance of chemical safety data among OECD countries, a crucial step towards international harmonisation and reduction of trade barriers.

Time period, main landmarks

The adoption of the Council Act on Mutual Acceptance of Data in 1981, opened up many new opportunities for governments to work together to tackle chemical management issues, as the same data would be accepted across all OECD countries.

The safety aspects of new chemicals being introduced to the market were obviously a key issue that needed consideration and relevant policies. In 1982, at an OECD High Level Meeting on Chemicals, countries decided that, before new chemicals are marketed, governments should have enough information about them in order to ensure that a meaningful assessment of hazards can be carried out. This decision signalled a policy change from a “react and cure” mode to “anticipate and prevent”. As a result, most OECD countries began to set up notification systems for new chemicals. A Minimum Pre-Marketing set of Data (MPD) was agreed in an OECD Council Recommendation, which specifies the information needed in the notification. This data set includes detailed information regarding the toxicity of chemicals and their potential for accumulation and biodegradation in the environment.

Once member countries had established workable systems for managing the safety of new chemicals, their attention turned to so-called “existing chemicals”. These were the tens of thousands of chemicals already on the market before new chemicals notification schemes had been put in place in the early 1980s. Member countries agreed that the task of investigating the safety of this large number of existing chemicals was too big for one country. Co-operation among countries on the assessment of these chemicals was initiated by a new Council Decision. The MAD system provided an excellent starting point on which to build such work. In order to organise the large amount of work, a number of priorities had to be set. It was agreed to deal first with High Production Volume chemicals (HPVs) – chemicals produced or imported annually in quantities of greater than 1 000 tonnes in at least one OECD country or the European Union – because in most cases these would potentially lead to the largest exposures to man and the environment. Agreement was then reached on the information needed on the HPVs, which resembled to a large extent the MPD for new chemicals. This programme led to the development of initial assessment reports for about 1 200 chemicals.

To further facilitate work sharing, OECD governments turned their attention to harmonising industry dossiers for the registration of new pesticides, or re-registration of existing pesticides. By using the same format, once a company compiles a dossier for one country, the costs and time involved in developing dossiers for other countries would be significantly reduced. In 1998, OECD adopted a guidance document for applicants wishing to have particular active substances approved or plant protection products registered. It provides guidance with respect to the format and presentation of the documentation to be submitted. Similarly, OECD issued a guidance document on the format and presentation of the documentation to be prepared by the regulatory authorities (i.e. a pesticide monograph), in the context of applications for the registration of plant protection products. The aim of these two documents was to reduce the cost to industry of submitting dossiers and facilitate the exchange of monographs between OECD countries with a view to achieve a sharing of the work necessary for the evaluation of plant protection products and their active substances. The OECD also has developed an electronic standard for the submission of pesticide dossiers and work has started to harmonise this electronic standard with those used for industrial chemicals. This will save considerable resources for governments, and time for industry.

Similar efforts over the years to develop guidance documents, common formats and share assessments have since been applied in the EHS programme for biocides, chemical accidents, regulatory oversight of biotechnology, the safety of novel foods and feed, and manufactured nanomaterials. Around 20 OECD Council Acts deal specifically with chemical safety issues, many of which foster greater co-operation amongst countries.

Institutional set-up: who does what in the co-operation, at what level of government

The EHS Programme is implemented by the Chemicals and Biotechnology Committee and its thirteen technical sub-bodies. In general, Heads of Delegation to the Chemicals and Biotechnology Committee comprise the Directors or Heads of Environment, Health and Safety programmes in governments, and their staff participate in the technical sub‑bodies.

Most of the work involves the development of instruments, methods, guidance documents and databases which support the harmonisation of chemical programmes and facilitate work sharing. When the OECD addresses a new chemical safety issue, the starting point is often a survey of current practices in OECD countries. The analysis helps determine similarities and differences among national approaches, and also helps identify the areas where the OECD can add value. OECD countries may then agree on a programme of work with clear, practical objectives and specific timelines. Countries then work together towards the common objectives. They prepare proposals, technical guidance, recommendations and policy documents that are usually reviewed in meetings. After policies are adopted, the OECD plays a facilitator role and assists countries in the implementation of the decisions by developing high-quality tools and instruments and regularly reviewing the implementation in member countries. In many cases, one or more governments takes the lead on developing new instruments often based on existing material – such as existing national test guidelines with the intention of developing harmonised OECD Test Guidelines that can be used to generate data that will be accepted in all OECD countries. All of these products are freely available via the internet. Many member countries and the European Union have used these products directly as part of their regulations (for example the Test Guidelines and GLP as standards for testing), or they have used the EHS products as a basis for developing and implementing their regulations.

Typically, the staff of the EHS Division carries out the daily work, co‑ordinating efforts with the work among experts and policy makers and with other intergovernmental organisations. The staff reviews and revises the first drafts proposed by lead countries, incorporates comments from experts in documents, organises the necessary meetings and teleconferences and works to build consensus on documents among member countries. The Secretariat also looks carefully at emerging issues in the chemical safety arena and brings them to the attention of countries, through proposals for work to be undertaken at the OECD. From the beginning of the work, stakeholders beyond government have also contributed actively through their participation in meetings. Many of the methods which are developed to address chemical safety have to be used by industry, and therefore it has been of great value to include the expertise from the chemical industry in the development of such methods. Participation by stakeholders from organised labour, environmental NGOs and the animal welfare community has also been important in ensuring a wider acceptance of this work.

Next steps envisaged in the co-operation

The Programme of Work for 2021-24 calls for a continuation of current efforts to support international regulatory co-operation, but also particularly in new areas:

Greater outreach to non-members. Global shifts in patterns of production of chemicals will mean that more countries will consider it prudent to set up chemical safety policies. Given the experience of OECD – including its support of SAICM – further co-operation with selected partner countries in a global context could prove to be very useful. In addition, input to OECD work from non-member experts will contribute to increasing the quality of the products and making them more widely applicable.

Co-ordination with experts to develop new methods which can improve the efficiency of the chemical safety management and reduce the use of laboratory animals (e.g. test methods using cell cultures, mathematical approaches designed to find relationships between chemical structures and biological activities of studied chemicals or integrated approaches that combine results from different methods to conclude on the properties of chemicals).

Sharing information and develop tools to assist countries in managing the risks of chemicals, e.g. developing tools for evaluating the health effects of chemicals or exchanging experience on managing specific chemicals of concern, such as perfluorinated chemicals.

Assessment

Benefits

In 2019, an analysis was conducted to determine the net savings governments and industry accrue from their participation in the OECD EHS Programme (OECD, 2019a) (a similar analysis was conducted in 2010 and 1998). With respect to quantitative savings, the analysis focused on the benefits of harmonisation through the MAD system including reduction in repeat testing for industrial chemicals, pesticides and biocides, the use of computational approaches for prediction of properties of chemicals, which reduce testing particularly for industrial chemicals (supported by harmonised OECD tools and guidance) and the use of common formats.

Four surveys were conducted in April 2018 to collect data from OECD governments and the biocide, industrial chemicals and pesticide industries. Additional data were collected from the OECD’s Event Management System, which contains data on the number of OECD meetings held each day and the number of delegates registered for those meetings. Data from relevant reports in the literature have also been used to complement and confirm data collected via the surveys.

The annual savings are summarised in the top portion of Table 2.1 as follows:

Table 2.1. Net annual savings resulting from the OECD's EHS Programme

|

Savings |

|

|

From no repeat pesticide testing |

EUR 206 937 500 |

|

From no repeat new industrial chemical testing |

EUR 44 728 943 |

|

From no repeat biocide testing |

EUR 61 250 000 |

|

From no repeat existing chemical testing |

EUR 780 570 |

|

From harmonised pesticide monographs |

EUR 2 218 145 |

|

From harmonised pesticide dossiers |

EUR 1 951 125 |

|

Savings subtotal (rounded) |

EUR 317 870 000 |

|

Costs |

|

|

Country |

EUR 3 809 000 |

|

OECD Secretariat |

EUR 4 545 000 |

|

Costs subtotal (rounded) |

EUR 8 354 000 |

|

Net savings (rounded) |

EUR 309 516 000 |

|

Reduction in animals needed for testing new industrial chemicals |

32 702 |

Source: (OECD, 2019[1]).

In essence, the analysis compared two scenarios: one with the MAD system, sharing the burden activities, and use of common formats; and the other, without such approaches. For example, without the OECD MAD system, slightly different test methods and GLPs would have been developed by each country independently. Based on the results of the EHS surveys of the pesticide, biocide and industrial chemicals industries, it was estimated that, in the absence of the EHS Programme, Country B would not accept 30% of the test data for industrial chemicals nor 35% of test data for new pesticides or biocides emerging from Country A because of differing methods, and therefore, that testing would have to be repeated.

In developing the 2019 report, it was not possible to quantify all of the benefits of the EHS Programme’s work. However, these unquantified benefits are just as real, likely and important as the quantified benefits. Some examples of work which leads (or will lead) to non-quantified benefits for governments and industry are:

fostering safer nanomaterials by developing harmonised tools for testing and assessment;

harmonising the safety assessment methodologies for products of modern biotechnology;

providing harmonised tools to identify the risks of endocrine disrupters;

reducing the need for national government inspections of test facilities in other countries which test chemicals;

enhancing hazard assessment methods and limiting the use of animals in chemical testing;

facilitating the exchange of information on chemical accidents to support prevention, preparedness and response;

advancing harmonisation of biocides regulations and testing;

reducing repeat testing for new pharmaceuticals;

counteracting the illegal trade of pesticides and thus reducing the chance that unregulated, unsafe and ineffective products are used on crops.

Also excluded are the benefits to industry of avoiding delays in marketing new products. According to industry sources, these could represent similar amounts to those saved by avoiding duplicative testing (for example, delays in the registration of a pesticide might lead to missed sales for a full growing season). Also excluded are the added benefits to health and the environment of governments working together to be able to evaluate and manage more chemicals than they would if they worked independently. Finally, while pharmaceuticals were not the subject of this analysis, it is expected that due to the extensive non‑clinical testing required for such products, and because many of these test methods may fall within the MAD system, the benefits of the EHS Programme for these products could be extensive.

Costs

In the 2019 analysis, the costs of the EHS Programme were calculated based on i) Secretariat costs (OECD Secretariat support, including staff salaries, benefits and travel; consultants and invited experts; and general overhead); and ii) Country costs (the costs to governments, industry and other non‑governmental organisations (NGOs) of participating in and contributing to the work of the EHS Programme). These include both travel costs to attend OECD meetings and staff costs for developing and reviewing EHS documents and preparing for and attending EHS meetings.

The 2019 report estimated the annual costs of the EHS Programme as shown below (Table 2.2) and summarised in the bottom half of Table 2.1 above. From this, the net annual savings of the Programme (Table 2.2) were estimated to be EUR 309 035 000: Total savings [EUR 317 870 000] minus Costs [EUR 8 835 000].

Table 2.2. Estimated total annual costs of supporting the EHS Programme

|

Country costs |

|

|

Number of meetings |

42 |

|

Average length of meetings (days) |

2.11 |

|

Average number of participants |

1 239.50 |

|

Travel costs1 |

EUR 1 455 000 |

|

Country staff costs2 |

EUR 2 354 000 |

|

Total country costs |

EUR 3 809 000 |

|

Secretariat costs |

|

|

Expenditure on permanent staff and consultancy funds |

EUR 1 866 000 |

|

Extrabudgetary Chemicals Management Programme |

EUR 2 679 000 |

|

Total Secretariat costs |

EUR 4 545 000 |

|

Total costs (Secretariat + countries) |

EUR 8 354 000 |

1. Travel costs (rounded) = travel [weighted average cost of round-trip flight (EUR 532.64) x number of participants (1 239.50)] + expenses [length of meetings (2.11 days) x daily expenses (EUR 304) x number of participants (1 239.50)].

2. Country staff costs (rounded) = participation [length of meetings in hours (2.11 x 8 = 16.88) x number of participants (1 239.50) x staff costs per hour (EUR 45)] + preparation [(150% x 16.88 = 28.86) x number of participants (1 239.50) x staff costs per hour (EUR 45)].

Source: (OECD, 2010[5]), Cutting Costs in Chemicals Management: How OECD Helps Governments and Industry, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085930-enand (OECD, 2019[1]).

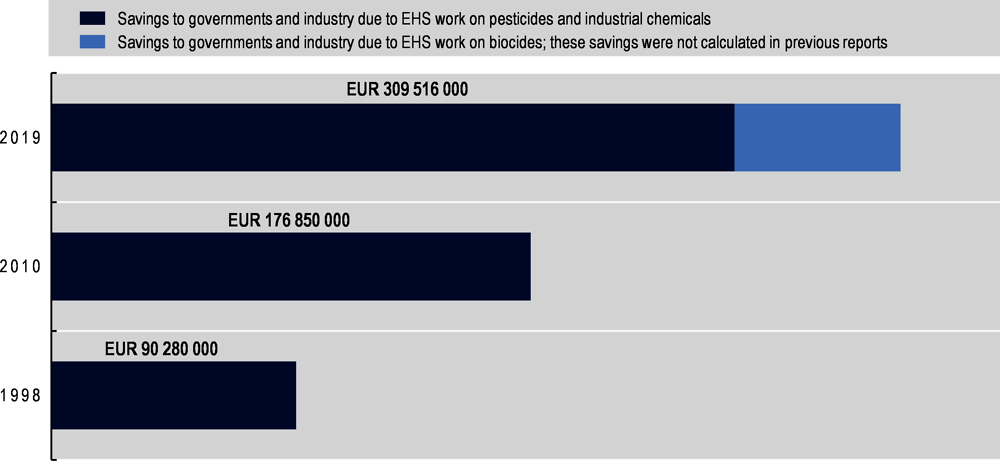

Evolution of the net savings

The 2019 report estimates that net savings attributable to the EHS Programme have grown by 75% since the last report and by over 240% since the initial report (Figure 2.1 shows the absolute growth). There are two reasons for the large increase in savings from the 2010 report. One, unlike the previous report, the current report includes the significant savings (around EUR 60 million per year) from tests on biocides (e.g. disinfectants) not being repeated due to MAD system. (The previous reports only included savings from industrial chemicals and pesticides.) Two, since 2010 there has been an increase in the number of OECD Member Adherents as well as non-OECD Member full Adherents to MAD. This means that the reduction in duplicative testing is now spread across more Adherents and hence the savings are greater.

Figure 2.1. Annual savings to governments and industry from the EHS Programme in 1998, 2010 and 2019

Challenges

Considering the work done so far in the EHS Programme and looking at expectations for future activities, the following challenges can be considered:

while the commitment of member countries and stakeholders to provide expertise and extra budgetary resources for work in the Programme is listed as one of its strengths, in times of budgetary constraints, this dependence on such commitments in order to be able to produce high quality results, could also turn into a weakness;

After years of working on chemical safety, many of the “easy” issues have been dealt with and while for the remaining tasks international harmonisation and work sharing will continue to be as necessary as before, the technical complexity (including advancements in science) will be increasing, which will make the relevance of continued work on chemical safety more difficult to explain to policy makers;

The shift in chemical production from OECD countries to non‑members can make the OECD less representative and less influential in the global setting when not enough attention is paid to outreach;

While obtaining consensus on methods and guidance is a necessity to ensure that these are also used in practice by all concerned, there is a risk that with the increasing complexity of issues and the increasing number of players involved, the process of obtaining consensus will become slower;

The difficulty of the monetary quantification of the effects of chemicals on human health and the environment, as well as of the impacts chemical safety policies have on avoiding such effects, can also result in a lower policy priority for chemical safety. Cost of inaction calculations, which have been politically influential in other areas of environmental policy, are difficult to carry out for chemical safety policies, although OECD is now working on this topic.

Factors of success

Trust building:

Development of networks and sharing of approaches;

Development of a common language / formats;

Alignment of testing methods and GLP;

Establishment of binding Council Acts on Mutual Acceptance of Data.

Focused initiative that grew progressively;

Strong industry buy-in and support.

Produces results in all of the three main outcome areas of IRC (as per OECD Best Practice Principles on International Regulatory Co-operation (OECD, 2021[6])):

Regulatory effectiveness – MAD and associated GLP ensures trust in data generated across MAD adherent countries, facilitating the use of data across regulatory programmes leading to more timely decision based on more consistent approaches;

Economic efficiency – MAD reduces economic burden across implicated industries and countries by re-use of test data and harmonised approaches with more than 35 times more quantified savings than associated costs (which also produce significant unquantified savings);

Administrative efficiency – Mutual recognition of Compliance Monitoring Programmes implementing GLP and the resulting studies under MAD is immensely more efficient than each country trying to determine the compliance of laboratories across countries and the quality of the resulting data.

References

[6] OECD (2021), OECD Best Practice Principles: International Regulatory Cooperation, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b28b589-en.

[1] OECD (2019), Saving Costs in Chemicals Management, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311718-en.

[3] OECD (2018), Estimating ad-valorem equivalent of non-tariff measures: Combining Price-Based and Quantity-Based Approaches, https://doi.org/10.1787/f3cd5bdc-en.

[5] OECD (2010), Cutting Costs in Chemicals Management: How OECD Helps Governments and Industry, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085930-en.

[4] SRC (1998), Secretariat of the Rotterdam Convention on the prior informed consent procedure for certain hazardous chemicals and pesticides in international trade, https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-14&chapter=27.

[2] WTO (n.a.), Environmental requirements and market access: preventing ‘green protectionism’, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/envir_req_e.htm (accessed on 9 21 2022).

Note

← 1. Global sales in 2017 amounted to over USD 5.6 trillion and are predicted to rise to over USD 21 trillion in 2060 (OECD, 2019[1]).