This chapter proposes a three-phase process for the development of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia, illustrated by insights generated by concrete interventions and research conducted as part of this project. In addition, it features a detailed review of practical engagements with four of the main RIS3 ecosystems: smart materials and photonics, smart mobility, bioeconomy and biomedicine.

The Public Governance of Anticipatory Innovation Ecosystems in Latvia

4. Towards a process for anticipatory innovation ecosystem development in Latvia

Abstract

Anticipatory Innovation Governance through innovation ecosystems: action research in Latvia

Through its RIS3 ecosystems, Latvia aims to leverage the collective intelligence of stakeholders from government, industry, academia and civil society to achieve two goals. First, to stimulate the exploration and discovery of opportunities for innovation in a rapidly changing and uncertain world. Second, to inform policy so that government can take timely action to enable these opportunities to be seized (Government of Latvia, 2021[1]). These joint objectives require the coordination of micro- and macro-governance processes so ecosystem partners and government can respond to the information and anticipatory knowledge they generate and maintain a necessary momentum of collaboration and action for innovation (Autio, 2021[2]).

As described in Chapter 2, this coordination and the structures that enable it are context dependent. This means that the identification of appropriate governance arrangements is best achieved through experimentation, rather than “adopting ideal models and best practices” (Guzzo and Gianelle, 2021[3]). The decision in Latvia to orient innovation ecosystems towards anticipatory innovation further necessitates experimentation to explore governance arrangements and processes that can enable the effective application of anticipatory approaches.

Over a two-year period from 2020-2022, the OECD worked closely with the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA) to explore how the development of innovation ecosystems in Latvia could be facilitated through effective anticipatory innovation governance. The programme of work consisted of three inter-related elements. First, analysis of theory and international case-studies to explore how an anticipatory focus for innovation ecosystems can be supported through public governance, and better understand the impact this might have on the anticipatory capacity of government (the resulting approach outlined in Chapter 2). Second, the assessment of Latvian stakeholders’ capacity for anticipatory innovation governance at the micro- and meso-levels to support innovation ecosystems and respond to the insights they generate. Third, testing and developing approaches based on this analysis, and the resulting model, through practical interventions with ecosystem stakeholders in Latvia. These interventions engaged actors in four ecosystems identified by LIAA: photonics and smart materials, biomedicine, bioeconomy, and smart mobility. Overall, more than 80 participants took part in seven workshops representing government, industry (incl. state-owned companies), research and academia, as well as other types of organisations.

This process of research and experimentation allowed the governance approach to be refined, revealing three phases of relevance to the public governance of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia: Initiation, Development and Maintenance, Exit. In addition, it demonstrated the potential of innovation ecosystems to generate rich and useful anticipatory insights to inform more proactive government action.

The three phases are distinguished by different types of activity undertaken by different types of stakeholders. The initiation phase demands meso-governance coordination to determine an overarching purpose for the government support of ecosystems and to identify the roles that government actors will play. During development and maintenance, activities to establish micro-governance processes among ecosystem partners are coordinated with meso-governance actions so that anticipatory knowledge is produced and acted upon by both ecosystems and government. The exit phase focuses on the approaches that government can use to determine the ongoing value of their support of an ecosystem and identify opportunities to withdraw.

Insights from practical interventions carried out with LIAA and Latvian stakeholders will be detailed throughout this chapter. In the first section examining three governance phases, a process for the development of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia will be proposed, illustrated by insights generated by concrete interventions and research as part of this project. The second section of this chapter will feature a more detailed review of practical engagements with four of the main RIS3 ecosystems: smart materials and photonics, smart mobility, bioeconomy and biomedicine. Each section will give an overview of the strategic insights and anticipatory knowledge generated. It will look at the ecosystems’ ambitions, trends and developments in their contextual environment, actions to improve ecosystem resilience and the challenges they face. These insights can serve as examples for the kind of knowledge that can be generated through the engagement with ecosystems to feed back into Latvia’s governance and policy systems.

Table 4.1. Overview of phases for the public governance of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia

|

Phase |

Objective |

Actions |

|---|---|---|

|

Initiation |

Determine a shared understanding of overarching programme objectives and logic |

Ensure that goals, priorities and expectations for the programme are discussed and agreed by relevant stakeholders at the meso-governance level, for example the Innovation and Research Governance Council. |

|

Provide government actors with information about anticipatory innovation governance innovation ecosystems and opportunities for discussion so that key stakeholders understand the benefits and limitations of the approach (Chapter 1 provides information on this). |

||

|

Collaboratively develop a programme-level theory of change with meso-governance stakeholders in order to identify key activities and roles they should play to support the programme, as well as gaps in capacity. |

||

|

Select and prioritise ecosystems for government support |

Choose a clear, evidence-based approach for the assessment, selection and prioritisation of ecosystems, for example foresight-based or quantitative (see Box 2.3). |

|

|

Build LIAA’s analytical capacity to assess the viability and needs of specific ecosystems. |

||

|

Provide political support to confirm and legitimise the selection of specific ecosystems. |

||

|

Establish roles for government stakeholders to facilitate coordination |

Relevant government actors can use the meso-governance framework (Chapter 2) at the initiation phase to discuss the roles they will play in relation to ecosystems and identify opportunities for coordination. |

|

|

Establish approaches for monitoring and evaluation |

Following agreement on programme level goals, identify approaches and indicators for the monitoring and evaluation of the programme and individual ecosystems. A combination of formative evaluation to support ongoing ecosystem development (see Box 2.9 and Annex A) and impact evaluation using indicators such as share of firms co-operating on innovation activities and turnover is valuable to generate a holistic understanding of ecosystem needs and potential. |

|

|

Development and maintenance |

Harvest information about ecosystems |

LIAA to gather information about ecosystem partners and their relationships through interviews and workshops in order to inform next steps of ecosystem engagement. |

|

Identify micro-governance processes to prioritise |

LIAA to apply the micro-governance framework (Chapter 2) to identify gaps and needs for each specific ecosystem. |

|

|

Plan, design and facilitate activities to develop micro-governance processes |

LIAA to use resources such as the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation toolkit navigator to identify and tailor appropriate methods to address the priority micro-governance processes. |

|

|

LIAA to create a detailed plan for how the methods should be delivered (online of offline), communicated, who should participate, how knowledge generated should be gathered, and what next steps should be. |

||

|

Harvest insights generated by ecosystem activities and reassess needs and priorities |

LIAA to collect, manage and analyse insights generated by ecosystem activities, and communicate them effectively to ecosystem partners. |

|

|

LIAA to support ecosystem partners to assess how new insights generated through ecosystem engagement can inform continued ecosystem activity. A theory of change can provide a useful framework to assess the relevance of new information to ecosystem goals and activities. |

||

|

Assess ecosystem needs and insights and coordinate government functions to provide support and influence policy |

LIAA to communicate needs and insights uncovered through ecosystem engagement to the Innovation and Research Governance Council and other relevant government actors. |

|

|

Innovation and Research Governance Council and other relevant government actors to apply the meso-governance framework to explore how government functions and policies can be aligned to ecosystem needs. |

||

|

Exit |

Identify opportunities to reduce or withdraw government support to ecosystems |

LIAA to use the formative evaluation toolkit (see Box 2.9 and Annex A) to monitor the development of micro-governance processes in each ecosystem and determine the potential for ecosystem partners to take on more responsibility for them. |

|

Innovation and Research Governance Council to gather information on the impact of ecosystem activities every three years using indicators such as share of firms co-operating on innovation activities and turnover to assess their effectiveness. This time-frame takes into account the time required to build ecosystem relationships. |

Phases for the public governance of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia

Phase 1: Initiation

The initiation phase is focused on establishing a robust meso-governance framework to ensure that there is legitimacy and support for anticipatory innovation ecosystems. In addition, it enables government to increase its capacity to leverage anticipatory knowledge generated by innovation ecosystems and align their activities towards policy priorities.

Determine a shared understanding of overarching programme objectives and logic

Setting clear scope and purpose is a key first step in establishing a successful programme for the development of multi-stakeholder initiatives such as anticipatory innovation ecosystems (Matti et al., 2022[4]). Without a shared understanding of the objectives and logic of a programme, expectations for it may be misaligned, leading to a lack of confidence in the process and challenges for coordination. In contrast, a clear scope and purpose enables stakeholders to determine their roles, coordinate activities and develop a sustainable strategy to support the development of anticipatory innovation ecosystems. Alignment of the programme to clear policy objectives across government departments enhances its legitimacy and facilitates further engagement from non-government stakeholders.

Latvia’s Guidelines for the National Industrial Policy 2021-2027 presents key details about the objectives and expectations for innovation ecosystems in Latvia (Government of Latvia, 2021[1]). However, interviews and collaboration with stakeholders in Latvia revealed a lack of clarity and shared understanding about how they could be achieved and monitored (Box 4.1), and scepticism about government’s support for ecosystems among ecosystem partners. For example, interviewees both within LIAA and in the private sector reported to the OECD that awareness at the political level of LIAA’s activities concerning ecosystems is not always particularly strong and that stakeholders often need to lobby for support for projects in order to obtain consistent funding, legitimacy and backing.

Key actions

Ensure that goals, priorities and expectations for the programme are discussed and agreed by relevant stakeholders at the meso-governance level, for example the Innovation and Research Governance Council.

Provide government actors with information about anticipatory innovation governance and innovation ecosystems and opportunities for discussion so that key stakeholders understand the benefits and limitations of the approach. For example, engaging diverse stakeholders to explore the future enables them to identify valuable identify opportunities for innovation, but this process can be time-consuming and challenging (see Chapter 1 for more detail).

Collaboratively develop a programme-level theory of change with key stakeholders (such as the Innovation and Research Governance Council) in order to identify key activities and roles they should play to support the programme, as well as gaps in capacity.

Box 4.1. Action-research in focus: Developing a programme-level theory of change

Latvia’s Guidelines for National Industrial Policy 2021-2027 document identifies the impact and outcomes that the government hopes to achieve through innovation ecosystems and existing challenges for collaboration and innovation in Latvia, focusing on increasing exports and R&D expenditure.

The document acknowledges the importance of taking environmental and climate issues into account for smart specialisation, as well as being responsive to future challenges. It sets out roles and responsibilities for government stakeholders and proposes a process for the development of long-term ecosystem strategies and regularly reviewed action plans. LIAA is identified as the coordinator for the development of strategies and action plans.

Over two participatory workshops in January and April 2022, the OECD supported LIAA to develop a programme-level theory of change in order to identify concrete outcomes and determine the activities and inputs that would be required to achieve these. In spite of the detail included in the Guidelines, discussion within the workshops revealed that expectations for the activities and outcomes anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia differed both within LIAA and among ministries, and that relevant measures to monitor ecosystem development were poorly understood. Furthermore, the roles of government stakeholders in supporting the programme were unclear, and LIAA did not have sufficient capacity or expertise to undertake the range of activities required to deliver the desired outcomes.

Select and prioritise ecosystems for government support

The OECD identifies five methods for governments to select and prioritise ecosystems for support: quantitative, mixed-methods, foresight-based, industry-led and grand challenge focused (see Box 2.3 in Chapter 2). Each of these methods aims to allow governments to determine the viability of innovation ecosystems by assessing their potential impact and whether there is a critical mass of stakeholders willing to collaborate. Their application requires capacities in information gathering, analysis and stakeholder coordination. Adopting a clear, evidence-based approach can help to address potential political tensions associated with selection. Nonetheless, political legitimacy is still important to promote engagement with and support of new ecosystems.

Latvia’s Guidelines for National Industrial Policy 2021-2027 identifies five broad areas for the development of RIS3 ecosystems: knowledge intensive bioeconomy, biomedicine, photonics and smart materials, smart energy and smart mobility and information and communication technologies (ICT). Prior work to support the development of ecosystems in the area of biomedicine, photonics and smart materials and smart mobility helped to ensure that each had a critical mass of stakeholders willing to engage in ecosystem activities, and that these activities could be tailored to their needs. However, interviews with stakeholders in Latvia (outlined in chapter 3) revealed that LIAA lacks the capacities to assess the viability of new ecosystems identified as priorities by government and the political legitimacy to galvanise engagement. Currently, LIAA attempts to support all ecosystems in parallel with a limited number of staff lacking time to engage with the specifics of each industry and group of stakeholders. Due to the lack of resources to analyse the macro-economic and policy context of each ecosystem, this work remains broad without clear priorities and focus. This in turn limits the ability to leverage ecosystem engagement to generate key insights for policy and governance that LIAA can feed back into the system.

Key actions

Choose a clear, evidence-based approach for the assessment, selection and prioritisation of ecosystems, for example foresight-based or quantitative (see Box 2.3).

Build LIAA’s analytical capacity to assess the viability and needs of specific ecosystems.

Provide political support to confirm and legitimise the selection of specific ecosystems.

Establish roles for government stakeholders

Coordinated meso-governance of anticipatory innovation ecosystems is necessary to ensure that their needs are addressed, policies to frame and support their actions complement rather than contradict each other and the knowledge they generate becomes actionable for government. The meso-governance functions framework described in Chapter 2 is a tool for government stakeholders to assess their complementarities and establish how they can coordinate their actions.

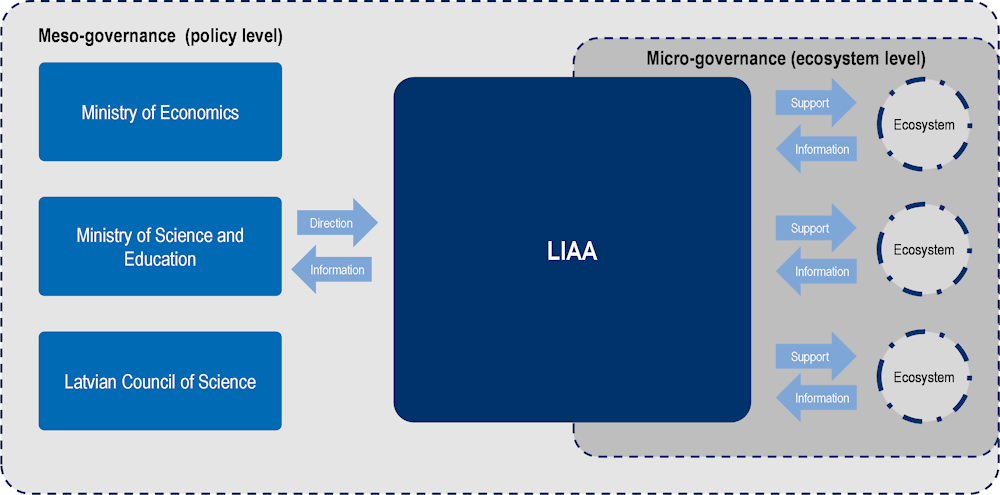

Interviews with stakeholders in Latvia revealed that the roles and responsibilities of ministries to ecosystems were sometimes poorly coordinated and unclear to ecosystem partners. For example, the Ministry of Agriculture oversees the bioeconomy domain and led on the development of a national bioeconomy strategy, but its involvement in the development and direction of the bioeconomy ecosystem is not yet defined. Interactive workshops with government actors and LIAA further identified that the development of anticipatory innovation ecosystems necessitates a shift in roles for ministries and agencies (Box 4.2), and that LIAA does not currently have sufficient capacity to undertake its expected roles (Box 4.1; Chapter 3). Figure 4.1 outlines a potential governance structure in which the Innovation and Research Governance Council coordinates meso-governance, with LIAA playing a key intermediary role to communicate policy direction to the innovation ecosystems and communicate insights generated by the ecosystems to the Innovation and Research Governance Council.

Key actions

Relevant government actors can use the meso-governance framework (Chapter 2) at the initiation phase to discuss the roles they will play in relation to ecosystems and identify opportunities for coordination.

Innovation and Research Governance Council to act as a platform for the coordination of meso-governance and the communication of policy priorities to innovation ecosystems through LIAA.

Box 4.2. Action-research in focus: exploring roles of government stakeholders to support ecosystems

In December 2021, the OECD and LIAA convened 18 representatives from LIAA, the Ministry of Education and Science, the Latvian Council of Science and the Ministry of Economics. Workshop participants were split into three groups to discuss the key benefits of innovation ecosystems in the Latvian context, and what roles government and agencies could play in developing successful ecosystems. An early version of the meso-governance functions framework was used to prompt discussion.

Participants found that the support requirements of ecosystems necessitated that institutions perform a variety of functions, reshaping usual expectations for their roles and functions. LIAA, for example, was understood as transitioning from Funding and Championing to increasingly Orchestrating stakeholders and potentially supporting the development of new approaches for Regulation. It was discussed that government could play a greater role in Providing infrastructure for innovation, such as testing infrastructure. Anticipatory innovation ecosystems were also understood as a valuable tool to generate knowledge identify improvements to policy and regulation.

The meso-governance functions framework prompted participants to discuss the importance of enhancing the government’s approach to regulation, improving the provision of public infrastructure to support testing and scaling, and better connecting ecosystems to funding opportunities in Latvia and beyond.

Figure 4.1. Proposed governance structure for anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia

Establish approaches to monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation of innovation ecosystems enables government stakeholders to determine the level and type of support they need, as well as their potential for successfully achieving their desired outcomes. Choosing appropriate methods and indicators for monitoring and evaluation at the meso‑governance level is important to ensure that ecosystems are not judged against unrealistic expectations, and that appropriate support can continue to be provided. As outlined in Chapter 2, ecosystems can benefit from setting their own outcome indicators. These may inform monitoring and evaluation at the meso‑governance level.

Formative evaluation

An anticipatory innovation ecosystem is characterised by dynamic, interacting processes which facilitate the engagement of diverse stakeholders, orientation around shared goals, collaboration and the ability to anticipate, learn and adapt. The sustainability and productivity of the ecosystem is dependent on its ability to maintain these processes in a changing environment. As a result, monitoring of ecosystem development should prioritise the assessment of each process with a view to identifying and undertaking required actions to enhance or adjust them. This is known as a formative or process evaluation.

As part of this project, the OECD worked with consultants to develop a formative evaluation toolkit that combines survey and interview approaches. The toolkit enables ecosystem partners’ perceptions on the relevance and usefulness of the workshops to be monitored and analysed with reference to the micro‑governance processes (see Box 2.9 and Annex A).

Impact evaluation

Attributing causal outcomes to anticipatory innovation ecosystems is a challenge, given the non-linear and emergent nature of innovation in an uncertain and complex environment. Mature micro-governance processes and relationships between stakeholders can take a number of years to develop (approximately two years according to Business Finland, meaning that short term analysis of their concrete impacts can cause it to appear as though ecosystems are ineffective. Nonetheless, regular assessment at the national and regional levels using common innovation indicators can allow governments to explore the broad effects of anticipatory innovation ecosystems. In addition, surveys and interviews with innovation ecosystem partners can support monitoring. The OECD Oslo Manual describes how these indicators can be selected and provides a guide on data collection.

Typically observed innovation metrics are reflected in compound scoreboards like the European Innovation Scoreboard (EC, 2021[5]), and the OECD’s Innovation Indicators. Relevant indicators for assessing the impact of innovation ecosystems are likely to focus on the “share of firms co-operating on innovation activities” with organisations across the Quadruple Helix; the OECD’s Business Innovation Statistics and Indicators list sets out seven such indicators (OECD, n.d.[6]). In assessing ecosystems in Finland, Business Finland, indicators include average turnover, employment, export growth, value added, R&D activity, number of new products, services and solutions developed (Box 4.3) (Piirainen et al., 2020[7]).

Key actions

Following agreement on programme level goals, identify approaches and indicators for the monitoring and evaluation of the programme and individual ecosystems. A combination of formative evaluation to support ongoing ecosystem development (see Box 2.9 and Annex A) and impact evaluation using indicators such as share of firms co-operating on innovation activities and turnover is valuable to generate a holistic understanding of ecosystem needs and potential.

Box 4.3. Business Finland: Monitoring and evaluation of innovation ecosystems

Business Finland provides funding to business ecosystems in order to promote innovation. It combines formal monitoring focusing on measurable indicators (e.g., export growth) and less formal engagement with the ecosystem to understand holistic development:

“When Business Finland provides funding, the companies have to report the costs. Business Finland has regular meetings with the ecosystems where they follow what has been done and how the costs occur. Business Finland might also propose some other Business Finland services, for example, export support. We try to see the ecosystems holistically, which requires monitoring and meeting companies regularly.” (Senior Director at Business Finland)

In the report Impact Study: World-class Ecosystems in the Finnish Economy, Business Finland provides a practical framework to monitor and evaluate innovation ecosystems in order to support the development of ecosystems. The framework has a two-fold approach:

Impact logic of ecosystems’ activities i.e., understanding the development of the funded ecosystems and assessing their evolution in the future.

Evaluation and assessment of Business Finland’s impact in supporting ecosystems.

The framework follows a theory of change structure. It monitors the Inputs (amount of financial and human resources); Activities (the types and amount of collaborative activities conducted by the ecosystem that entail joint efforts and build mutual trust); and Outputs which are structured per development phase i.e., emergence, startup, growth/expansion and maturity/renewal. Across these four development phases the outputs can pertain to setting up new collaborations (emergence), attracting and binding talent (start-up), entering new markets (growth/expansion), and market leadership (maturity/renewal).

Additionally, the framework monitors Outcomes which are the result of joint activities conducted by ecosystem members. These can be the development of new products, services and solutions. However, the outcomes can also be the result of gaining access to new markets through increased visibility and recognition as well as increased collaboration, dynamics and interdependence.

Finally, the Impacts generated by the ecosystem are those linked to Business Finland’s “impact goals of economic renewal and growth through new billion-euro ecosystems”. The indicators to measure impact goals are turnover, value added, employment, productivity, and export growth.

Nevertheless, the report highlights that there are challenges in measuring these indicators as “monitoring company level data does not yet reflect the development of the ecosystem as it is likely that (especially in large companies), only a fraction of their KPIs reflect the business relevant for the ecosystem. Therefore, these macro-level indicators should be supplemented with additional (qualitative) data”.

Source: OECD interview; Piirainen, K. et al. (2020[7]), Impact Study: World-class Ecosystems in the Finnish Economy, Part A – A New HoPE, https://www.businessfinland.fi/4aa4e1/globalassets/finnish-customers/news/news/2020/world-class-ecosystems-report-2020.pdf.

Phase 2: Development and maintenance

An anticipatory innovation ecosystem is a process through which diverse stakeholders explore uncertainties in the future in order to identify opportunities for collaboration and innovation. The process continually generates knowledge that can lead to better collective decisions by ecosystem partners and by government to facilitate anticipatory innovation.

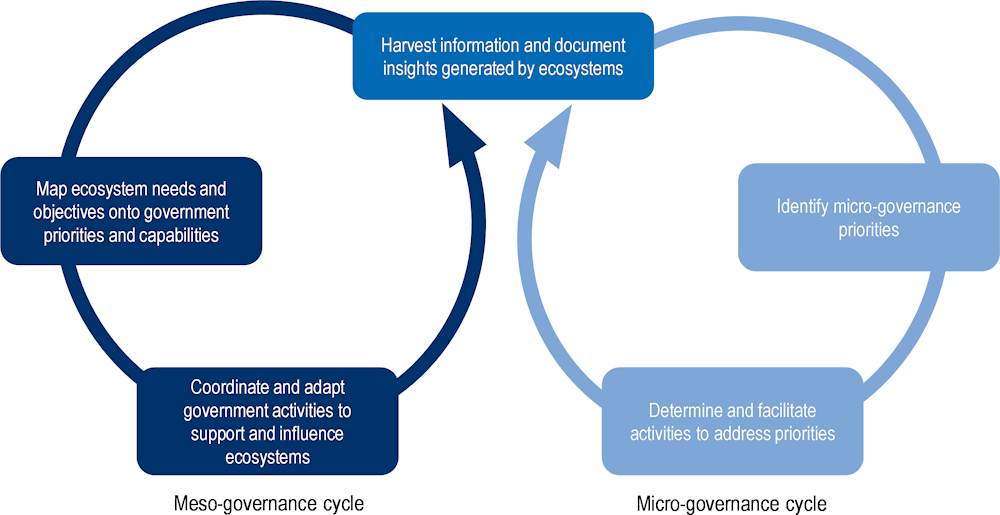

Figure 4.2. Governance cycles for the development and maintenance of anticipatory innovation ecosystems

The ‘development and maintenance’ phase describes how this process can be sustained through interlocking cycles of micro- and meso-governance activities, in which ecosystem level activities generate actionable knowledge about the future and ecosystem needs, and government actors make sense and act on it. For example, an online foresight workshop with members of the bioeconomy ecosystem in Latvia revealed tensions between objectives set out in the national bioeconomy strategy. Participants identified six key steps to address these and improve the ecosystem’s resilience in the face of future challenges, including and greater ministerial coordination.

Early stages of ecosystem development are likely to require intensive orchestration and knowledge management by ecosystem support teams to establish micro-governance processes, while meso‑governance must be responsive to ecosystem needs. As micro-governance processes are established and ecosystems mature, support teams may be able to reduce their inputs and activities while retaining their role as a knowledge broker between the micro- and meso-governance levels.

Micro-governance: Harvest information about ecosystems

Following the definition of overarching programme objectives and logic at the meso-governance level and the selection of ecosystems, focus can be placed on developing micro-governance processes. Each ecosystem is unique, and therefore requires individual assessment to determine which micro-governance processes should be prioritised at any one point.

To conduct an initial assessment, the ecosystem support team will need to collect and analyse information about ecosystem partners, their relationships to one another, and the environment in which they are operating. Engaging actors who regularly interact with ecosystem stakeholders, such as business incubator and science commercialisation support staff, can help to rapidly surface relevant information and identify knowledge gaps. This can be accomplished through interviews and workshops (Box 4.4). The micro‑governance framework can be applied to identify the types of information that are required.

Key actions

LIAA to gather information about ecosystem partners and their relationships through interviews and workshops in order to inform next steps of ecosystem engagement and the design and of appropriate activities.

Box 4.4. Action-research in focus: identifying opportunities for ecosystem partner engagement

In October 2021, the OECD facilitated an online workshop with eleven LIAA technology scouts and innovation ecosystem coordinators to consider the development potential and needs of three ecosystems in the areas of space innovation, forestry and 5G in healthcare. It revealed that LIAA would benefit from improving its capacities to collect and analyse information about emerging or potential ecosystems.

A series of online activities, structured around a digital ‘canvas’ were developed to enable the assessment of each potential ecosystem based on knowledge held by LIAA employees. Facilitators from the OECD guided participants to:

Identify potential ecosystem actors in the public sector, academia, industry and civil society, and categorise them as ‘key ecosystem decision-makers’, ‘stakeholders who can influence the ecosystem’ and ‘stakeholders affected by the ecosystem’.

Identify the influential actors in each ecosystem, and consider their motivations for participation.

Assess the existing foundations and challenges for the development of each ecosystem.

Identify desired outcomes for LIAA to achieve through ecosystem engagement.

Determine next steps to achieve the desired outcomes.

The workshop revealed knowledge gaps that LIAA would need to address before proposing activities with ecosystem partners, as well as specific challenges for the initiation of each ecosystem. These included:

Space ecosystem: Limited knowledge of potential ecosystem partners, and a lack of collaboration between research and industry.

Forestry ecosystem: Limited knowledge of potential ecosystem partners and their current relationships. No existing ecosystem structure.

5G and healthcare ecosystem: A need to engage SMEs and work with healthcare providers to build trust and establish test-beds. Challenges in getting information from biomedicine stakeholders in Latvia.

Micro-governance: Identify micro-governance processes to prioritise

Ecosystem partners and support organisations can map the micro-governance processes onto information about ecosystems to identify which processes to prioritise in subsequent activities. For example, by assessing an ecosystem’s relationships, rules, roles and resource management capabilities against the descriptions detailed under collaboration (Chapter 2), gaps and areas for development can be identified. Prioritisation helps ecosystem partners and support teams to select and tailor tools and methods to support the development of each ecosystem. Micro-governance processes are interrelated, meaning supporting the development of a particular process will have a beneficial impact on the others. For example, any activity which brings together ecosystem stakeholders is also likely to increase capacity for collaboration.

Practical work with LIAA revealed how prioritisation is dependent on good information about ecosystem stakeholders and their relationships (Box 4.5).

Key actions

LIAA to apply the micro-governance framework (Chapter 2) to identify gaps and needs for each specific ecosystem.

Box 4.5. Action-research in focus: prioritising micro-governance processes

LIAA chose to focus on testing approaches for anticipatory innovation ecosystems in the four areas of: smart materials and photonics, biomedicine, smart and green mobility, and bioeconomy. Drawing on information presented by LIAA, LIAA and the OECD collaborated to identify key micro-governance processes to prioritise for each area.

Smart materials and photonics: Anticipation, learning and adaptation, shared goal orientation.

Biomedicine: Anticipation, learning and adaptation, shared goal orientation.

Bioeconomy: Anticipation, learning and adaptation, engagement of diverse stakeholders.

Smart and green mobility: Anticipation, learning and adaptation, engagement of diverse stakeholders.

Developing the capacity of each ecosystem to collaborate was also considered important, but not as an immediate focus.

Subsequent workshops with ecosystem partners revealed that while the areas of prioritisation for smart materials and photonics, biomedicine and smart and green mobility were relevant, a greater focus should have been placed on enhancing the ecosystem partners’ capacity for collaboration within the bioeconomy ecosystem.

Micro-governance: Plan, design and facilitate activities to develop micro-governance processes

After choosing micro-governance processes to prioritise, ecosystem partners and support teams must identify and facilitate activities to support their development. Many toolkits exist that can help ecosystem partners and support organisations to select activities and methods which develop micro-governance processes. The Observatory of Public Sector Innovation Toolkit Navigator can enable the identification of appropriate methods. The capacity and knowledge to select and tailor tools and methods must be complemented by the ability to communicate their value to ecosystem partners, facilitate collaboration and analyse the insights that this generates. This may require subject matter expertise in the area of ecosystem development.

Following six workshops which engaged ecosystem stakeholders in Latvia, a formative evaluation revealed key considerations to ensure that activities are able to generate valuable insights and support further ecosystem development.

Communication

Invitations should be sent at least a month in advance to increase the chances of participation.

Goals and objectives of each activity should be clearly articulated to participants within invitations, and should focus on the overarching value of collaborating as part of innovation ecosystem.

It should be clearly communicated how each activity is expected to contribute to the broader goals for ecosystem development.

At the start of each activity, it is necessary to provide a clear agenda and re-iterate the value of participation.

Participation

The consistent participation of decision-makers from key organisations was identified as an important driver of trust and progress. Ecosystem support teams should invest in developing engagement plans which take into account the incentives and goals of key stakeholders.

Not every activity will be relevant for all stakeholders. Participants suggested that future workshops could be structured by distinct activities and tasks for different stakeholders.

Facilitation

Facilitation skills were seen as important to ensure that activities were well understood, and that all participants had an opportunity to speak and be heard.

Online workshops and tools

Online collaboration tools (for example, Padlet, Mural) are effective at enabling stakeholders to share information and opinions.

Online workshops are considered to be more useful for later stages of ecosystem activity when ecosystem partners know one another better.

In-person workshops

In-person workshops are effective at enabling stakeholders to meet each other and forge connections, and were considered to be particularly important in the early stages of ecosystem development.

One-day workshops are more likely to engage relevant stakeholders than longer two-day events (as occurred with the biomedicine ecosystem).

Knowledge management

A system for gathering and analysing information generated by the ecosystem is necessary to enable informed decision-making.

Each activity should be concluded with clear follow-up actions, and an indication of how the information it has generated will be used to further the development of the innovation ecosystem.

Key actions

LIAA to use resources such as the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation toolkit navigator to identify and tailor appropriate methods to address the priority micro-governance processes.

LIAA to create a detailed plan for how the methods should be delivered (online or offline), communicated, who should participate, how knowledge generated should be gathered, and what next steps should be.

Micro-governance: Harvest insights generated by ecosystem activities and reassess needs and priorities

The interactions between innovation ecosystem stakeholders and with others generate information that is useful both to the ecosystem and to the meso-governance level. Systems and capabilities to enable the capture, analysis and communication of this information enhance the capacity of the ecosystem to anticipate, learn and adapt and inform ongoing decision-making.

As discussed in Chapter 2, a collaboratively developed theory of change can be a valuable tool to for ecosystem partners and support teams to document assumptions and assess the continued relevance of objectives, the activities that are intended to achieve them, and the resources that they require. Where new information calls into question elements of the theory of change, ecosystem members and support organisations can use it to systematically explore how they might change their actions to continue moving towards desired goals. After this step, the micro-governance cycle re-starts at Identify micro-governance processes to prioritise.

Key actions

LIAA to collect, manage and analyse insights generated by ecosystem activities, and ensure that they are communicated to ecosystem partners effectively (Box 4.6). Summaries of action points for the ecosystem, responsibilities for those action points, and an implementation timeline can help to maintain ecosystem momentum and accountability.

LIAA to support ecosystem partners to assess how new insights generated through ecosystem engagement can inform continued ecosystem activity. A clear roadmap or theory of change for ecosystem development can help ecosystem partners to recognise how their activities contribute the objectives and development of the ecosystem and contextualise ongoing engagements.

Box 4.6. Action-research in focus: follow-up communications with ecosystem partners

Following each online workshop with ecosystems in Latvia, the OECD produced a short, visual report of approximately 10 pages to document key discussion points and insights generated through the participation of ecosystem stakeholders. This covered:

The objectives of the workshop.

A list of attendees.

A summary of workshop activities.

A summary of information generated through the workshop (e.g. trends and future changes, challenges to be addressed, goals).

Proposed next steps and objectives for ecosystem collaboration.

Examples of this content appears in the second half of this chapter. The formative evaluation identified a need for a more detailed summary of action points following each ecosystem activity.

Meso-governance: Assess ecosystem needs and insights and coordinate government functions to provide support and influence policy

Through interaction, ecosystem members identify challenges and needs that cannot be addressed entirely by ecosystem members. In addition, they generate valuable anticipatory knowledge that can help governments to become more proactive.

A collective approach to sense-making among relevant government stakeholders is valuable to enable a coordinated response to ecosystem needs and the identification of related policies and support mechanisms.

Key actions

LIAA to communicate needs and insights uncovered through ecosystem engagement to the Innovation and Research Governance Council and other relevant government actors.

Innovation and Research Governance Council and other relevant government actors to apply the meso-governance framework to explore how government functions and policies can be aligned to ecosystem needs.

Phase 3: Exit

As discussed under approaches to monitoring and evaluation, micro-governance processes provide a framework by which ecosystem development and needs can be monitored and assessed. Initiating these processes is likely to require a high level of coordination from an ecosystem support team, for example creating prototype agreements to develop the capacity to collaborate or establishing a knowledge management approach to develop the capacity for anticipation, learning and adaptation.

While the processes must be regularly reviewed and renewed in response to internal and external developments, ecosystem support teams may be able to progressively delegate this responsibility to other ecosystem partners. Doing so can allow them to reduce the level of their activity with and ecosystem and focus their attentions elsewhere. On the other hand, regular formative and impact evaluation activities may reveal that certain ecosystems are unable to develop in maturity or deliver value. In this case, government may wish to withdraw its support.

Given the value of ecosystems as mechanisms for the generation of knowledge about the future that can enable governments to become more anticipatory and proactive, it is of continued benefit for government stakeholders to play a role in the meso-governance of innovation ecosystems.

Key actions

LIAA to use the formative evaluation toolkit (see Box 2.9 and Annex A) to monitor the development of micro-governance processes in each ecosystem and determine the potential for ecosystem partners to take on more responsibility for them.

Innovation and Research Governance Council to gather information on the impact of ecosystem activities every three years using indicators such as share of firms co-operating on innovation activities and turnover to assess their effectiveness. This time-frame takes into account the time required to build ecosystem relationships.

Insights from action research and next steps for ecosystem development

Over seven workshops, the OECD and LIAA engaged actors in four ecosystems identified by LIAA: photonics and smart materials, biomedicine, bioeconomy, and smart mobility. Overall, more than 80 participants took part in the seven workshops representing government, industry (incl. state-owned companies), research and academia, as well as other types of organisations.

The rich insights they generated identify next steps for the development of each ecosystem, gaps and challenges to address through government intervention, and signals of future change that could help the government of Latvia to proactively address future challenges and opportunities in a range of areas. These are detailed in the ecosystem case studies below. Overall findings and priorities for future action are summarised at the end of the chapter.

Exploring and testing ambitions for the Smart Materials and Photonics innovation ecosystem

Representatives working with Photonics and Smart Materials participated in online workshops on 7 April 2021, 5 April 2022 and 16 June 2022. The workshops were designed and facilitated by the OECD to enable participants to apply anticipatory approaches to identify shared goals for the future, explore future changes that might affect the ecosystem, and set out next steps for ecosystem collaboration.

Findings

Ambitions for the Smart Materials and Photonics ecosystem

Participants in the workshop on 5 April 2022 were invited to propose ambitions for the ecosystem to achieve by 2030, using an online collaborative tool. These were plotted by participants against an axis of ‘Not at all challenging’ to ‘Extremely challenging’, before they voted on the most important ambitions. This revealed two priority ambitions: ‘Latvia has a powerful innovation system, and is an innovation leader in the EU’, and ‘There are sufficient STEM students to support the development of photonics and smart materials in Latvia’. On 6 June 2022, participants were asked to re-assess these ambitions, and agreed that they should still be prioritised.

Future changes that may impact the ecosystem

On 5 April 2022, participants were asked to identify possible future changes that may affect the ecosystem’s ability to achieve its ambitions. The outcomes of this horizon-scanning approach were structured under the PESTL framework.

Table 4.2. Horizon scanning: possible changes that may affect the Smart Materials and Photonics ecosystem

|

Category |

Possible future changes |

|---|---|

|

Political |

|

|

Economic |

|

|

Social |

|

|

Technological |

|

|

Legislative |

|

Note: Horizon scanning exercise conducted on 5 April 2022.

Actions to improve ecosystem resilience and achieve shared ambitions

In activities on 5 April 2022, and in the following workshop on 16 June 2022, participants identified concrete outputs to achieve and actions for ecosystem partners and LIAA to undertake in order to support ecosystem development and achieve shared ambitions in the face of the potential changes that were identified.

Table 4.3. Outputs and actions to strengthen the development of the Smart Materials and Photonics ecosystem

|

Outputs |

Actions |

|---|---|

|

Engage stakeholders through communication |

1. Create and maintain a list of ecosystem success stories for the general public, politics, industry, investors 2. Popularise STEM education through investment in a constant public relations channel |

|

Develop a shared action plan |

3. Prepare a shared ‘to-do’ list of complementary activities for different ecosystem actors 4. Develop clear guidelines on the directions for R&D that are important to Latvia 5. Map the strengths of different organisations in Latvia to inform coordinated actions |

|

Conduct regular foresight and analysis |

6. Regularly and jointly analyse the ecosystem’s SWOT and identify ‘low hanging fruit’ (every 1-2 years) 7. Develop and regularly update at least 3 different scenarios for future development of the ecosystem 8. Identify short- and medium-term focal points for the ecosystem |

|

Commit to national and international cooperation |

9. Identify and cooperate with other ecosystems nationally and internationally, for example the PhotonDelta ecosystem in the Netherlands 10. Facilitate a bottom-up approach for ecosystem management in which government is an active player |

Note: Actions identified on 5 April 2022.

In the June workshop, a stimulus of a list of actions undertaken by other ecosystems (identified through OECD research) was provided to prompt discussion and support decision-making. Participants identified key actions for achieving the ambitions of ‘Latvia has a powerful innovation system, and is an innovation leader in the EU’, and ‘There are sufficient STEM students to support the development of photonics and smart materials in Latvia’. These were:

Establish links with international ecosystems and value chains.

Establish graduate programmes.

Create living labs.

Hold Quadruple Helix workshops.

Functions and roles for ecosystem development

The discussions highlighted the need for ecosystem members to be more proactive and communicative, for LIAA to take on a more proactive role, and for increased engagement with civil society.

Table 4.4. Stakeholder functions and roles for ecosystem development.

|

Stakeholder |

Actions |

|---|---|

|

LIAA |

|

|

Industry |

|

|

Research |

|

|

Government |

|

Note: Exercise conducted on 16 June 2022.

Challenges to address for ecosystem development

Interviewees participating in the formative evaluation highlighted that an initial strategy for the Smart Materials and Photonics ecosystem was previously developed, including concrete short-term and long‑term action points. However, it appears this initial strategy is not known to all actors, neither are the principles for its development. As one interviewee stated:

“I don't think other ecosystem players know the existing strategy on smart materials [except the leading research organisation who was driving it]. [With respect to this process three years ago], it was not clear who was invited in the ecosystem formation, who was left out and why. There was no wider discussion on the focus of the ecosystem either.” (Representative of Smart Materials and Photonics ecosystem)

This highlights the need for a greater focus on knowledge management and clearly defined rules and processes for collaboration.

Proposed next steps

Meso-governance:

Orchestrating: There is a need to appoint at a minimum one full-time ecosystem coordinator, either within LIAA or externally funded. The coordinator or support team needs to level up ecosystem orchestration by ensuring regular engagement of partners through written communication and meetings. Ecosystem partners need regular input and opportunities to engage in order to stay invested in the ecosystem development, for example through a regular newsletter, online meetings and interactive workshops with a clearly defined purpose, agenda and follow-up.

Providing: The coordinator in collaboration with LIAA and the Council can also take steps to establish links with complementary ecosystems abroad, both in the Baltics and internationally. Given the clear need for skilled graduates to develop photonics and smart materials in Latvia, the Ministry of Education and Science and other government actors could support the ecosystem by orchestrating relationships with skills providers and championing opportunities for work within the smart materials and photonics ecosystem internationally. This could be designed as co-funded temporary work and research placements in relevant organisations abroad or could be setup as a regular exchange programme between graduates and young professionals in the photonics and smart materials field.

Micro-governance:

Engagement of diverse stakeholders: Discussions showed that the ecosystem partners see a particular need to engage more strategically with stakeholders in Latvia (government, research experts, universities) as well as internationally, in particular with other ecosystems and universities working on similar topics. To serve this need, the ecosystem coordinator can collect interests and contacts from ecosystem partners to undertake a stakeholder mapping and then define engagement forms for each of the groups. For example, this could include the preparation of materials for discussion at the Innovation and Research Council meetings as a form to engage with policymakers. To engage with substance experts, the ecosystem could organise networking events with organisations of relevance or substantive engagements with experts such as topical panel discussions, peer-learning sessions or disseminate analysis produced by the ecosystem in writing.

Shared goal orientation: While strategic priorities and practical actions (Table 4.2 and 4.3) have been defined by the ecosystem, there is no coherent connection between strategy and action. The theory of change approach could be leveraged to define priorities in an actionable yet flexible way (see Chapter 2 and Box 2.7). Ecosystem partners need to define which capabilities to leverage in what capacity in order to reach the desired objectives and attach time-bound, measurable goals to each priority. This could be done using a digital tool available to all ecosystem members in order to create transparency and ownership. Based on these key priorities, the ecosystem can proceed to define a shared action plan which also takes into account innovation goals for Latvia. LIAA could support the creation of this document by working with ecosystem partners to collaboratively develop a theory of change or roadmap. The agency needs to fulfil its role of feeding government priorities into the discussion based on objectives defined in the Council.

Exploring and testing ambitions for the Bioeconomy innovation ecosystem

On 12 April 2022, stakeholders in Latvia’s bioeconomy ecosystem participated in a strategic foresight workshop led by the OECD in order to support the development of micro-governance processes and stress-test the Latvian Bioeconomy Strategy 2030 (LIBRA) that was published in 2017 under the leadership of the Ministry of Agriculture and translated into English in 2018 (Government of Latvia, 2018[8]).

Participants were sent links to the LIBRA strategy in advance of the workshop. Within the workshop, they worked together to review the 2017 LIBRA strategy statement against potential future scenarios for the bioeconomy ecosystem. To elicit this reflection, participants were asked to:

1. Imagine: Describe a world in which the strategic vision, as outlined in the LIBRA strategy, has been achieved.

2. Assess: Work backwards from the future and identify what factors or assumptions contributed to the success of Latvia’s Bioeconomy strategy.

3. Stress-test: Explore how the strategy would be affected if key assumptions and factors underlying the strategy did not succeed as expected.

During the workshop, it became apparent that very few participants had reviewed the strategy, or knew how it had been developed. As a result, a representative of Ministry of Agriculture gave a short introduction. While the lack of engagement with the strategy challenged the initial objectives of the workshop, the interaction between participants generated useful insights for the future development of the ecosystem.

Findings

Trends and events create tensions between objectives for the Bioeconomy ecosystem

Participants recognised that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a crucial concern to consider before reflecting on a success story for the Bioeconomy’s strategy. As one participant pointed out: “life has changed after the 24th of February and we need to review our tactics and strategic agenda”. The conflict, and the uncertainties it generates, called into question assumptions in the LIBRA strategy and highlighted tensions between objectives and trends. For example:

Forestry and wood: Two strategic goals were identified by stakeholders as key for the development of forestry: increase in productivity of forest land and increasing the value of goods produced. It was highlighted that as southern regions are affected by climate change, Latvia could become a key player in the production of wood and innovative methods to increase its value. However, energy crises resulting from the conflict in Ukraine may encourage the continued production and export of low-value woodchips, limiting the availability of resources and the drive for innovation.

Food: Given the impact of the conflict on food markets, participants viewed that a success story for this sector in Latvia would mean exploring new markets, beyond the exports of grains. For example, one participant envisioned a world in which Latvian companies will be leading the production of protein goods from leguminous plants. A tension was identified between the need to increase food production, and a movement away from fertilizers and agrochemicals in order to promote biodiversity.

Actions to increase the resilience of the Bioeconomy ecosystem

Participants identified fragmentation at the meso-governance level and a lack of coordination between stakeholders as key challenges to stimulating innovation and addressing the tensions inherent in setting goals for the ecosystem. As a result, they identified six actions to promote ecosystem development through the four micro-governance processes.

Table 4.5. Actions to increase the resilience of the Bioeconomy ecosystem

|

Engagement of diverse stakeholders |

1. Build cooperation within scientific institutions |

|

Shared goal orientation |

2. Create clear action plans in line with the bioeconomy strategy with support from relevant ministries |

|

Collaboration |

3. Strengthen local value chains 4. Link projects for bioeconomy innovation in Latvia 5. Create coordination systems among ecosystem partners |

|

Anticipation, learning and adaptation |

6. Gather information and collaboratively make sense of new ways on how bioeconomy can promote practices for value creation in conjunction with biodiversity maintenance |

Note: Actions identified on 12 April 2022.

Challenges to address for ecosystem development

Interviews as part of the formative evaluation revealed that one of the main bottlenecks for the formation of Bioeconomy ecosystem is that these diverse organisations do not associate themselves as belonging to one ecosystem. Bioeconomy includes a wide range of industries representing food, feed, non-food and bioenergy sectors, each with their own drivers, challenges and outlooks for the future. It appears that the overarching term ‘bioeconomy’ does not describe clearly enough the focus for coherent ecosystem activities. Another important hindering factor is the noticeably lower drive and motivation for industry to think about innovation in these more traditional business sectors. As an interviewee acknowledged:

“I think ecosystem players do not fully understand the term ‘bioeconomy’ [where focus is placed on innovation in the traditional sectors], hence sometimes it is difficult to involve them in activities. It is also important to fully understand the readiness of bioeconomy industry to invest time, effort, and money in innovation. Industry is often very cautious how to scale research results and sometimes they simply lack ambition and motivation to work on more value-added products and new markets as they hold a certain local market share and find that sufficient.” (Representative of Bioeconomy ecosystem)

Linked to the lack of clear understanding about bioeconomy as a field of activity, also this domain of policy is fragmented in terms of strategy design and implementation. The issues with the national bioeconomy strategy were cited, which is the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture. The ministry oversees the bioeconomy domain at the national level, yet it is not monitoring any real strategy implementation activities. In the meantime, other organisations that implement R&I strategies and activities are frequently not even aware of the pre-existing strategic policy frameworks for bioeconomy development, hence real cross-sectoral and cross-institutional innovation initiatives are hampered.

Proposed next steps

Meso-governance:

Orchestrating: Currently, organisations do not have a strong sense of belonging to the ecosystem. There is a need for a dedicated support team to take on a series of activities to clarify which organisations want to engage, what their level of commitment is and what they can contribute to and gain from the ecosystem. This will only be possible with the help of an internal or external coordinator facilitating the ecosystem’s development on a continuous basis.

Framing: Strategic discussions may lead to a rethinking of the developed LIBRA strategy and may result in a new focus for ecosystem partners. The Innovation and Research Governance Council could work more closely with the Ministry of Agriculture to explore the ways in which they can coordinate to achieve objectives of the LIBRA strategy and identify priorities for ecosystem direction from among trade-offs and tensions discussed by ecosystem members. These can then be communicated back to the ecosystem.

Micro-governance:

Collaboration: Ecosystem members currently lack commitment to engage in joint activities and collaboration within the ecosystem. With the help of a dedicated coordinator, the ecosystem needs to identify which members want to stay engaged and which joint objectives form the basis of this commitment. Activities identified in the past will likely need to be re-examined to create a new basis for future collaboration. The ecosystem could start by undertaking activities to identify the current level of trust between ecosystem partners and determine how stronger relationships can be built. Further collaborative workshops employing approaches such as participatory system mapping may help ecosystem partners to recognise their interdependencies and lay the foundation for future coordination and collaboration.

Shared goal orientation: Once a core group of motivated ecosystem partners has been identified, the group needs to identify common objectives, also by reassessing components of the LIBRA strategy to adjust to present priorities of those organisations committed to future collaboration. Activities which facilitate a close, collective assessment of the revised strategy can help ecosystem stakeholders to better understand the roles they can play to achieve the objectives it sets out, identify synergies and tensions, and enable the development of a coherent roadmap of actions for the ecosystem. It will be important to match objectives with actions that the partners are committed to take so that progress can be measured going forward.

Exploring ambitions and future changes for the Smart Mobility innovation ecosystem in Latvia

Stakeholders in Latvia’s Smart Mobility ecosystem participated in an online strategic foresight workshop led by the OECD on 14 June 2022. Through structured online activities that combined discussion with individual work using the collaborative platform Padlet, participants worked together on three key questions about the future of the Smart Mobility Innovation Ecosystem in Latvia:

1. What does success for the ecosystem in the future look like?

2. What future changes and trends might affect the ecosystem?

3. How do we better prepare to achieve success?

Findings

Ambitions for the ecosystem

Participants identified eleven ambitions for ecosystem development within four categories.

Table 4.6. Ambitions for the Smart Mobility ecosystem

|

Category of ambition |

Possible future changes |

|---|---|

|

Social and environmental |

|

|

Technological |

|

|

Economic |

|

|

Ecosystem functioning |

|

Note: Ambitions identified on 14 June 2022.

Trends and potential changes that may impact the ecosystem

Participants participated in a horizon scanning exercise to share and collate trends and potential future changes.

Table 4.7 Trends and potential changes that may impact the Smart Mobility ecosystem in Latvia

|

Category |

Possible future changes |

|---|---|

|

Political |

|

|

Economic |

|

|

Social |

|

|

Technological |

|

|

Legislative |

|

|

Environmental |

|

Note: Trends identified on 14 June 2022.

Actions to improve ecosystem resilience and achieve shared ambitions

Participants proposed actions to increase the ecosystem’s chances for success in the face of three most impactful changes and trends they identified.

Table 4.8. Identified actions to improve the resilience of the Smart Mobility ecosystem in Latvia

|

Trend |

Actions to increase resilience |

|---|---|

|

Working for home continues in the long-term, and car use and ownership declines |

1. Increase engagement of civil society to understand their developing needs and design bottom-up solutions 2. Encourage active mobility (pedestrian and cycle infrastructure) in order to promote health benefits |

|

New financial crisis initiated by spiralling inflation |

3. Focus on increasing the accessibility of personal and public transport |

|

Testing of new technologies remains slow and bureaucratic, hampering innovation |

4. Foster capacities for agile project management and experimentation in government to facilitate the testing of new solutions 5. Aim to increase the number of smart city pilots 6. Simplify the authorisation process for the testing of new initiatives by facilitating vertical coordination in government 7. Develop new rules for government procurement to encourage the adoption and development of novel solutions |

Note: Actions identified on 14 June 2022.

Challenges for ecosystem development

According to interviews conducted as part of the formative evaluation, the Smart Mobility ecosystem appears to be already a well-knit collaboration network where actors know each other quite well and are receptive of the overall ecosystem building philosophy and mindset. The main stumbling blocks for this ecosystem formation are all practical ecosystem building aspects, including understanding of the mandate of the ecosystem initiative as a policy instrument, as well as the lack of knowledge of the most appropriate ecosystem governance, orchestration, and funding models. As an interviewee put it:

“For the ecosystems to function we need two things - power and money. Without a strong mandate, ecosystems for an untrained person will resemble simple associations or discussion groups without much value added. The other problem is funding. In Latvia we often have the cases that there are good ideas, but nothing happens beyond the proposal stage [due to missing discussion on impactful funding models].” (Representative of Smart Mobility ecosystem)

This highlights a need for more effective meso-governance to provide legitimacy to the ecosystem and develop funding channels.

Proposed next steps

Meso-governance:

Orchestrating: To advance ecosystem activities, there needs to be at least one full-time coordinator, either from LIAA or funded externally. The ecosystem needs to establish a collaborative structure which means for example defining the frequency and format of engagements, setting up writing communication formats, identifying digital platforms for information sharing and defining roles and responsibilities between the coordinator, LIAA and the ecosystem partners. The coordinator needs to develop a series of activities that allow to determine which ecosystem partners are committed to engage going forward and in what capacity they want to contribute to ecosystem development. Without clear ‘rules of the game’ the ecosystem will not be able to reach its innovative potential.

Funding: Once there is a clear commitment from ecosystem partners, the Innovation and Research Council can play an important role in helping the ecosystem to identify funding sources, both from public and private channels. For example, a Council meeting could be used for a strategic discussion on funding opportunities and what links can be made within government to give ecosystem partners the necessary support and access. It will be an important responsibility of the coordinator to identify opportunities, communicate them to ecosystem partners and help drafting proposals for funding bids.

Regulating: The Innovation and Research Council could work more closely with cities and regulators to develop opportunities for testing in controlled environments. This would give ecosystem partners a chance to try out new innovations and get direct feedback from users on a smaller scale before making further investments into any given idea.

Micro-governance:

Collaboration: The ecosystem currently lacks a basic structure of engagement. Ecosystem partners are not continuously engaged so there is a need to identify their expectations and needs in order to tailor activities accordingly. With the help of a coordinator, the ecosystem needs to bring partners together to identify a governance structure going forward, including regular written communication, in-person events to build relationships and workshops to start developing shared objectives. A dedicated workshop facilitated by LIAA to discuss different approaches to setting out rules, determining roles and managing resources is likely to be valuable. Case studies, such as the 6G Flagship (Box 2.4) and BioWin Health Cluster (Box 2.8) can provide concrete examples, and peer-exchange sessions with representatives of other ecosystems using online conferencing software can help the Smart Mobility ecosystem members to consider what governance structures and processes will work best in their context.

Exploring a vision, identifying changes and setting ambitions with the Biomedicine innovation ecosystem

On May 17 and 18 2022, around 25 representatives from industry and academia working in the field of biomedicine took part in a 1.5-day in-person workshop in Riga hosted by LIAA and facilitated by the OECD. The intervention took part at a relatively early stage of ecosystem development. It was designed to enable members of the ecosystem to strengthen collaboration, collectively explore uncertainties and change in the future and harness these insights to identify shared goals allowing to facilitate anticipatory innovation.

Findings

Harnessing insights about the Biomedicine ecosystem

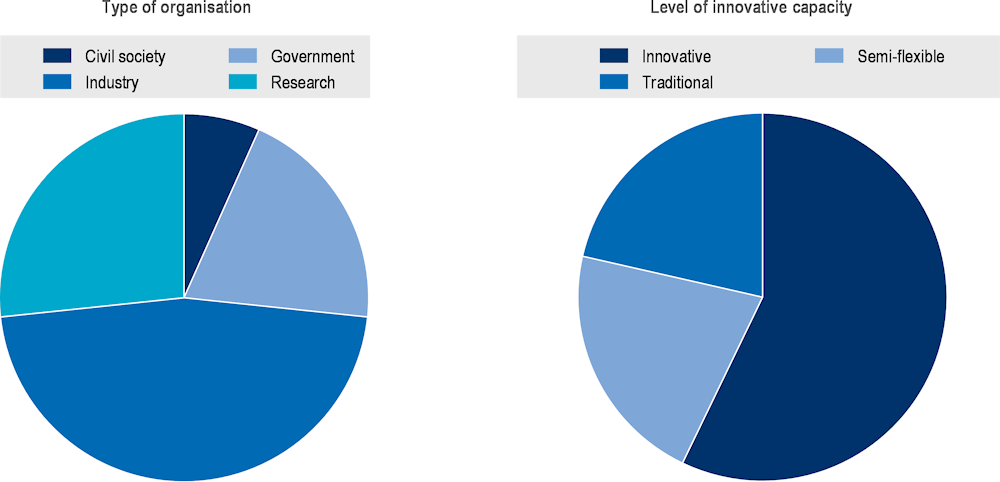

To harness diversity of stakeholders and strengthen a common understanding among participants, the group was invited to interview each other and identify characteristics about each organisation and where they currently stand regarding innovation. The below graphs show that most of the organisations that invested time in developing the ecosystem stem from the private sector. The majority of organisations in the ecosystem consider themselves as innovative. The exercise also revealed that mature organisations make up the dominant part of participants, with only a limited number of start-ups present.

In a subsequent activity, participants collectively identified the main resources and capabilities present in the ecosystem. This included listing the main partners of relevance to any potential ecosystem activity and innovative projects, as listed in Table 4.9.

The participants also listed a wide list of tools and infrastructure at their disposal, including massive gene sequencing infrastructure, medical technology accelerators or numerous valuable networks (Horizon 2020, clinics and doctors on national and international level, international research specialists).

In addition to existing resources, the activity also revealed some of the needs the ecosystem identified in order to effectively collaborate on biomedical projects. For example, participants discussed the need for guidelines on the use of data or frameworks for the safe use of open data tools in the field of medicine.

Figure 4.3. Types of organisations and innovation capacity in the Biomedicine ecosystem

Table 4.9. Relevant partners for the Biomedicine ecosystem

|

Main partners identified |

|

|---|---|

|

Distributors |

Laboratories |

|

Manufacturers |

Hospitals |

|

Small and medium enterprises |

Healthcare workers |

|

Start-ups |

Doctors |

|

Patient rights protection organisations |

LIAA |

|

Non-governmental organisations |

EEN |

|

Pharmaceutical companies |

State agencies |

|

Universities |

Research institutions |

|

Ministries |

|

These insights show what kind of targeted information ecosystem support can generate for the purpose of well-informed policymaking. The direct access to organisations can be an asset to better understanding Latvian industries and research organisations in the biomedicine field. This can allow to harness inputs for policymaking, develop target support mechanisms and generate a better understanding of the needs and priorities of stakeholders in the Latvian economy.

Future changes that may impact the ecosystem

Ahead of the in-person workshop, a number of participants took part in an online horizon scanning workshop on 22 February 2022 to identify potential future changes of relevance to the ecosystem based on the PESTLE framework (Table 4.10). These included societal factors such as resistance to new technologies by patients or doctors, rising mistrust in evidence and expertise in society at large, lack of skills (human capital, medical expertise, research). The group also identified economic factors such as potential funding gaps (lack of state investment, research funding, decreasing EU funds) as well as overall economic crises including a challenging climate in the pharma industry specifically. Regarding technology, participants discussed the potential of biology and engineering to increasingly merge into one field of bioengineering, the potential take-up of precision medicine for rare diseases or the overall rapid growth of the bioeconomics field. Furthermore, participants discussed environmental factors such as a lack of raw materials needed for biomedical research and commercial activities or increasing impacts of global warming on the industry at large. When it came to political factors, the group discussed the potential lack of regional cooperation between industry actors, both within Latvia and with neighbour crisis and the geopolitical context of, at the time, rising tensions in Russia and Ukraine.

The in-person workshop in Riga built on some of these potential changes, discussing the importance for the ecosystem to closely monitor changes in the digital health field, trends in medical technology, also coming from other sectors (such as large global technology corporations) and developments in pharmaceutical research and development.

Table 4.10. Horizon scanning: possible changes that may affect the Biomedicine ecosystem

|

Category |

Possible future changes |

|---|---|

|

Political |

|

|

Economic |

|

|

Social |

|

|

Technological |

|

|

Environmental |

|

Note: Identified on 22 February 2022.

Developing shared ambitions for the Biomedicine ecosystem

During the workshop in Riga, participants were invited to identify ambitions for the ecosystem, based on the individual and organisational objectives they brought into the group. The exercise guided them towards the development of a shared vision that would define priorities for actions in the coming months and years.

The group identified the importance of engaging key partners (Table 4.9) in an effort to harness their support. In particular, the collaboration with administrative authorities in order to solve policy and regulatory barriers was important. For example, this could include working with the Ministry of Justice to give input to the development of new laws regarding the use of patient data. Other priorities identified focused on internal collaboration within the ecosystem, communication and the exchange of resources, see Table 4.11.

Table 4.11. Shared ambitions for collaboration of the Biomedicine ecosystem

|

Ambitions for the organisation of the ecosystem

|

Note: Identified on 17 and 18 May 2022.

When discussing the ecosystem’s overall vision, the group identified the following priorities, looking at both internal governance as well as innovation ambitions:

Secure sustainable and strategic financing.

Make relevant data available for all ecosystem partners to use.

Ensure equal access to health care data.

Support a cross-ministerial working group to support ecosystem projects.

Develop well-being focused innovation, moving from treating illness to improving quality of life and well-being.

Building on these high-level ambitions, participants discussed concrete next steps for the ecosystem to take

1. Define the format and approach for ecosystem communication.

2. Develop approach to foster cooperation of decision makers, experts and makers.