This chapter explores challenges and opportunities for the development of anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia through a descriptive analysis of policy priorities, current governance structures, policy frameworks and systemic reforms in the field of research and innovation.

The Public Governance of Anticipatory Innovation Ecosystems in Latvia

3. The policy and governance context for anticipatory innovation ecosystems in Latvia

Abstract

This project has been driven by Latvia’s ambitions to work with ecosystems to stimulate the discovery of opportunities for innovation in a rapidly changing and uncertain world. To explore how anticipatory innovation ecosystems might be established and supported in the Latvian context, a desktop review of policy documents and assessments was combined with research interviews of key stakeholders from the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA), Ministry of Economics (MoE), Latvian Council of Science (LCS) and Riga Technical University (RTU).

The chapter intends to place the work on anticipatory innovation ecosystem into an overall context of Latvia’s activities in related fields. The first part will briefly describe the macroeconomic context of the Latvian Research and Innovation System and provide an overview of the relevant policy developments. It will then consider Latvia’s governance structure, policy framework, main support measures and recent reforms that have taken place. Further, the chapter will provide information about ongoing initiatives to support collaboration platforms including initiatives for ecosystem formation and draw conclusions on the synergies and consistencies among them. Lastly, the chapter will address the evolving role of LIAA in support of innovation ecosystems and its capacity to deliver on its mandate.

The economic context to Latvia’s innovation policy approach

Over the past decades, the Latvian economy has shown significant growth rates and enjoyed continuing catch-up in per capita incomes with the more affluent OECD countries (OECD, 2022[1]). Nonetheless, Latvia’s income level still stands at around 70% of the EU and OECD country average. (EC, 2022[2]; OECD, 2022[1]). In order to promote an increase of living standards, national policies have emphasised the pivotal role of the knowledge economy. The National Development Plan 2021-2027 stresses the role of people as most important national resource and the need to make use of existing knowledge and skills as an advantage for growth. The plan outlines the objective to channel the country’s limited resources into knowledge creation, acquisition and transfer (CSCC, 2012[3]). Building on this, Latvia defines the objective of its national research and innovation (R&I) framework as the promotion of economic transformation towards higher value-added activities (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[4]; Government of Latvia, 2021[5]).

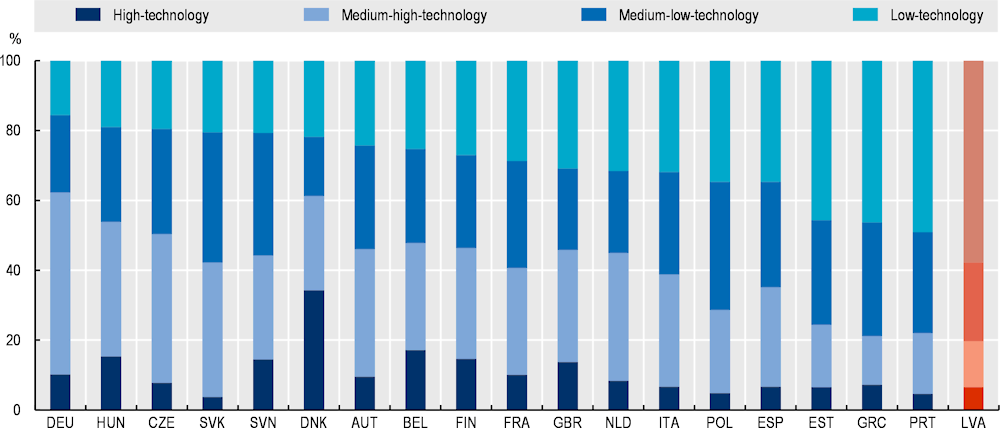

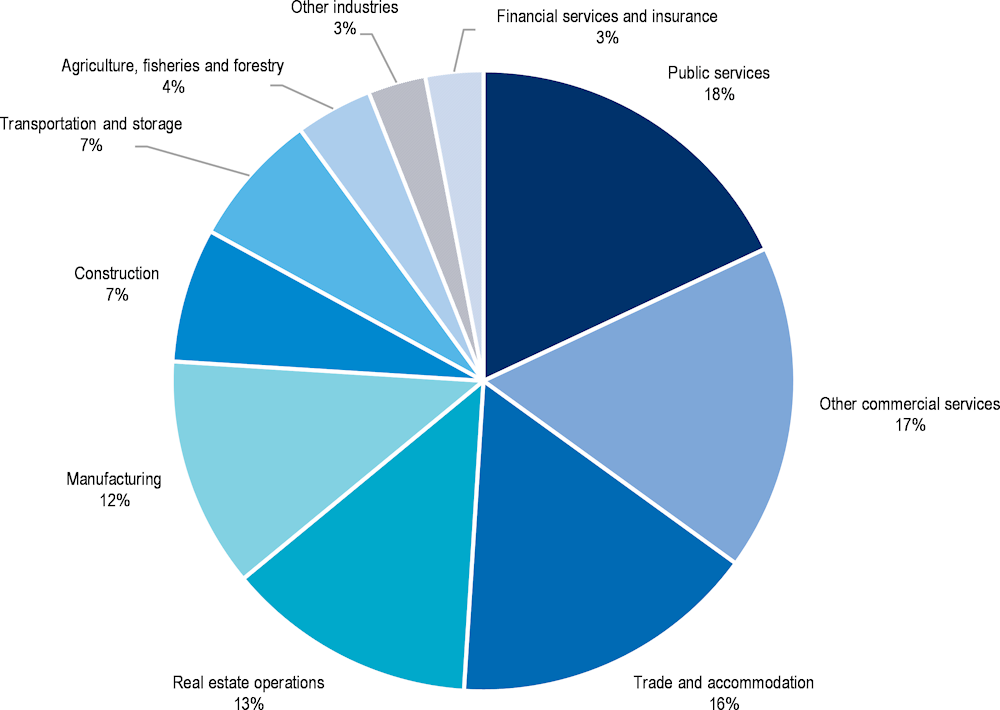

Regarding the overall economic structure, Latvia’s focus has been on moving towards higher value goods and services (meaning, usually but not always, higher technology). Currently, Latvia’s service sector generates the highest share of value-added (Figure 3.1). Tradable sectors, including agriculture, forestry, fisheries, manufacturing, and transport, constitute only 26% of the total economy, a decrease from 33% in 2010. Manufacturing and other industry comprise roughly 15% of the value-added activities. The share of high-tech manufacturing in 2020 was 8%, with medium-high-tech and medium-tech accounting for respectively 14% and 19%. Low technologies representing 58% of the overall sector dominate the manufacturing industry (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]).

While the relative share of high-tech manufacturing has increased since 2000, its impact on the overall productivity in Latvian economy is still insignificant. See Figure 3.2 for an overview of gross value-added in manufacturing by technological intensity compared to other OECD countries. It shows that high- and medium-high-tech still contribute only a minor share to the productivity growth due to their small share in output (Latvian Ministry of Economics, 2021[6]). Businesses in Latvia rely heavily on the acquisition of machinery for technological upgrading and export is predominantly based on low value-added products and services that is dependent on external demand. The dominance of low value-added sectors in Latvian economy is an important bottleneck for its structural transformation (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[4]).

Figure 3.1. Added-value structure of the Latvian Economy, 2020

Note: Based on Eurostat aggregation of the manufacturing industry according to technological intensity, based on NACE Rev.2.

Source: Eurostat.

Figure 3.2. Latvia's manufacturing by technological intensity, 2018

Source: Latvian Ministry of Economics (2021[6]), Latvia’s Macroeconomic Overview, https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/media/11553/download.

Innovation parameters in Latvia are below the EU and OECD average. Much of Latvian business’ competitiveness is driven by low labour costs with innovation playing only a minor role. While the share of technological equipment and intellectual property of GDP has slightly increased from pre-2008 crisis levels, it remains low compared to the EU average. Gross research and development spending as a share of GDP, at around 0.7%, makes up only about one quarter of the European average (OECD, 2022[1]). As a country moving towards high-income status, innovation will need to play an increasingly important role. In order to improve productivity and competitiveness, it will be essential for Latvia’s industry to engage more deeply in technological development as well as inward technology transfer. This implies focusing on knowledge- and not just efficiency-based growth and hence on making and using a greater investment in research and innovation (R&I) (OECD, 2022[1]).

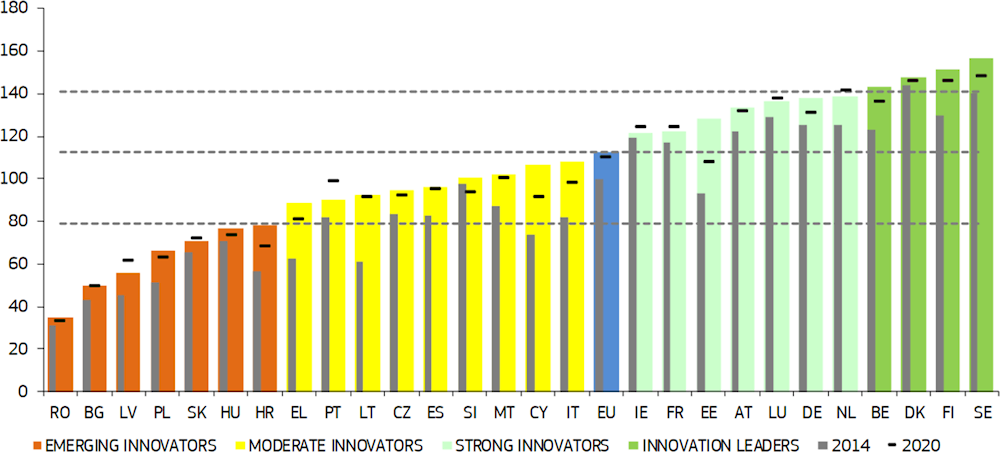

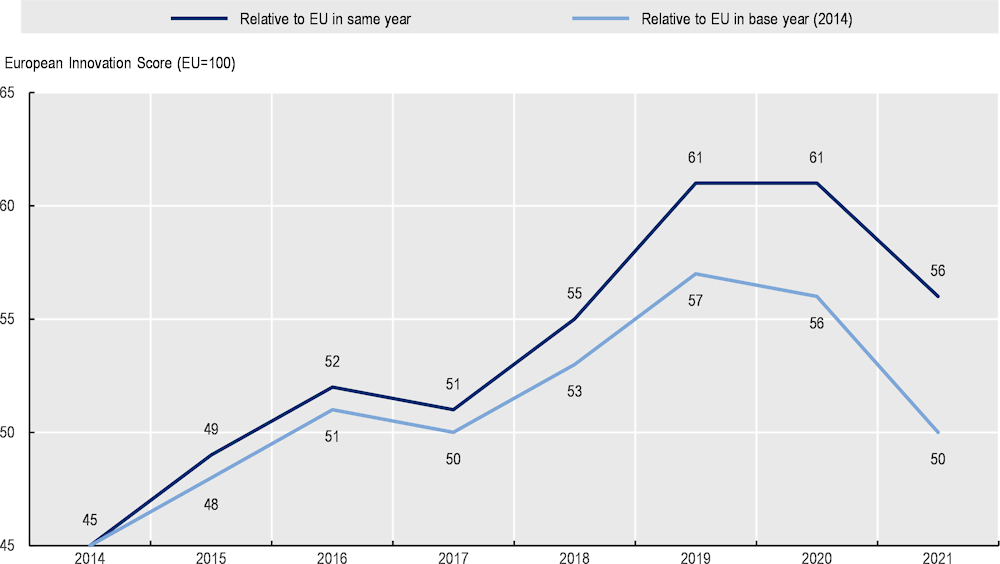

The European Union classifies Latvia as an emerging innovator country which means its performance is well below the EU average, currently at 50.8% (Figure 3.3) (EC, 2022[2]). Latvia showed a gradual, steady increase of innovation performance in the period 2014-2019 and a decline in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 3.4). In the European Innovation Scoreboard’s comparative perspective, the relative strengths of Latvian innovation performance include the levels of tertiary education, trademark applications and enterprises providing ICT training. The sharp decline in the innovation score between 2020 and 2021 is associated with a decrease of venture capital investment and development of environment-related technologies (EC, 2022[2]). Overall, start-up rates in Latvia are well above average of most OECD countries which speaks for its dynamic, entrepreneurial culture (OECD, 2022[7]). However, while Latvia has a growing number of knowledge-intensive start-ups with international reach, their aggregate contribution to the overall innovation performance is likely to remain small (OECD, 2022[1]). According to an OECD assessment, Latvian stakeholders perceive that innovation diffusion to SMEs and start-ups does not work well (OECD, 2022[1]). Lack of internal funding, limited access to affordable funding for smaller firms and high anticipated costs of innovating are among the innovation obstacles perceived by firms (OECD, 2022[1]). To improve innovation performance there will also need to be significant transformation within existing companies of which about 30% are government owned (EC, 2018[8]) . In addition, Latvian stakeholders, both with a policy and business background, acknowledge the importance of strengthening cooperation between business and academia (OECD, 2022[7]).

Figure 3.3. Performance of EU member states' innovation systems, 2015-21

Note: Coloured columns show countries’ performance in 2022, using the most recent data for 32 indicators, relative to that of the EU in 2015. The horizontal hyphens show performance in 2021, using the next most recent data, relative to that of the EU in 2015. Grey columns show countries’ performance in 2015 relative to that of the EU 2015. The dashed lines show the threshold values between the performance groups, where the threshold values of 70%, 100%, and 125% have been adjusted upward to reflect the performance increase of the EU between 2015 and 2022.

Source: EC (2021[9]), European Innovation Scoreboard 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/46013/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

Figure 3.4. Innovation performance of Latvia, 2014-21

Source: EC (2021[10]), European Innovation Scoreboard 2021 - Latvia, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/45922.

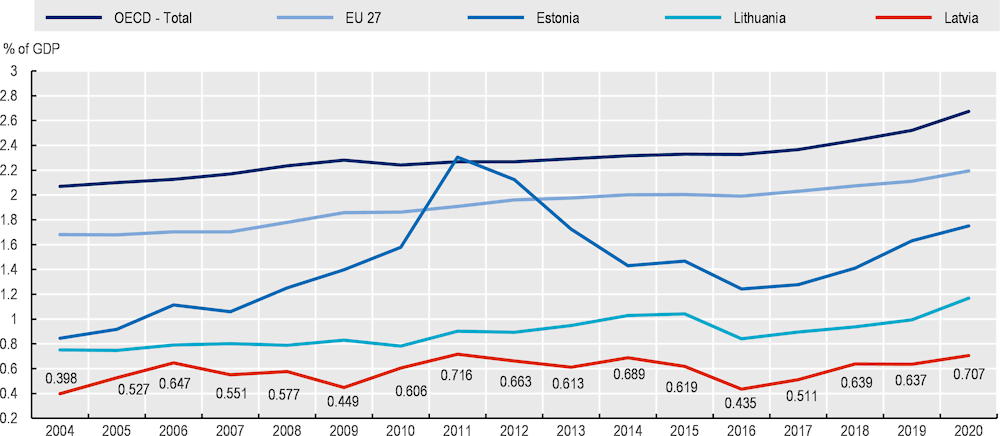

Over the course of the last decades the Latvian R&I system has suffered from underfunding and a range of systemic issues. As the country was among the European Member States worst affected by the financial crisis starting in 2008 which resulted in a significant decrease of state spending on R&I that has not returned to target levels since. The objective defined in the national strategic development documents was to increase R&I investments to 1.5% of GDP by 2020 (CSCC, 2012[3]) following the ambitious goals of the EU Lisbon Strategy.1 Latvia never accomplished this objective and until 2020 F&I spending has not exceeded the 0.71% threshold. Figure 3.5 plots the comparative levels of gross domestic spending on R&D in the three Baltic States and the average EU and OECD levels. It showcases that gross domestic spending on R&D in Latvia are not only three times lower than in the OECD and EU countries, but also significantly lags behind the investments made by the neighbouring Baltic countries – Lithuania and Estonia. Moreover, private Latvian R&D investment is significantly lower than in other OECD countries and stagnating (OECD, 2022[7]). In 2020, it was 0.22% of GDP, about the same as it had been 10 years earlier. This is well below the EU average of 1.53% of GDP (EC, 2022[2]).

Fiscal austerity measures of the financial crisis and insufficient national funding for R&I have led to a disproportionate reliance on the EU Structural Funds for the development of the Latvian R&I system (EC, 2018[8]). Due to budget restrictions, only few departments beyond the Ministry of Education and Science and the Ministry of the Economics developed and funded their own research strategies. Except during the planning phase of structural funds periods, collaboration on research and innovation across government agencies has been limited (with exceptions of recent State Research Programmes – see below). The importance of increasing the share of national investment in R&I has been raised in major external assessments of the Latvian R&I system.2 While more targeted policy efforts have resulted in a gradual increase of national R&I spending, this increase is relatively small and its impact remains limited. The target of reaching a R&I expenditure of 1.5% of GDP has been manifested in the national strategy documents as a target to be reached by 2027 (CSCC, 2020[11]).

Figure 3.5. Gross domestic spending on R&D, 2004-20

Source: OECD (n.d.[12]), Gross Domestic Spending on R&D, https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm.

The R&I sector in Latvia is part of the European Research Area, which means that national R&I policy needs to take into account not only national development priorities, but also European guidelines, global trends and challenges. The Guidelines for Research, Technology and Innovation 2021-2027 underline that innovative solutions are needed to address societal challenges regarding public health, inequality, quality food, access to clean and efficient energy, ensuring inclusive public services, secure and qualitative living environment (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[4]). National R&I strategies refer to seven societal challenges as outlined by the EU, namely areas with high potential benefit for citizens: health; demographic change and wellbeing; food security; sustainable agriculture and forestry; marine, maritime, inland water research and bio economy. Equally, the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals3 are recognised as important guidelines for steering national R&I efforts (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[4]). From this wide array of challenges, the National Development Plan of Latvia for 2021‑2027 singles out climate change, geopolitical shifts, inequalities, rapid technological development and increased migration as new challenges for the Latvian society and national security that require R&D investment (CSCC, 2020[11]).

Latvian research and innovation policy in the last decade

The following section will give an overview of Latvia’s approach to innovation over the course of the past years. It will examine the governance structure of research and innovation policy; describe the policy framework and ongoing policy measures in the field of innovation and research and take a lot at some recent reforms. This will give an overview of the main stakeholders involved decision-making, how Latvia’s innovation efforts have evolved over time and the current initiatives under way.

Governance structure of R&I policy in Latvia

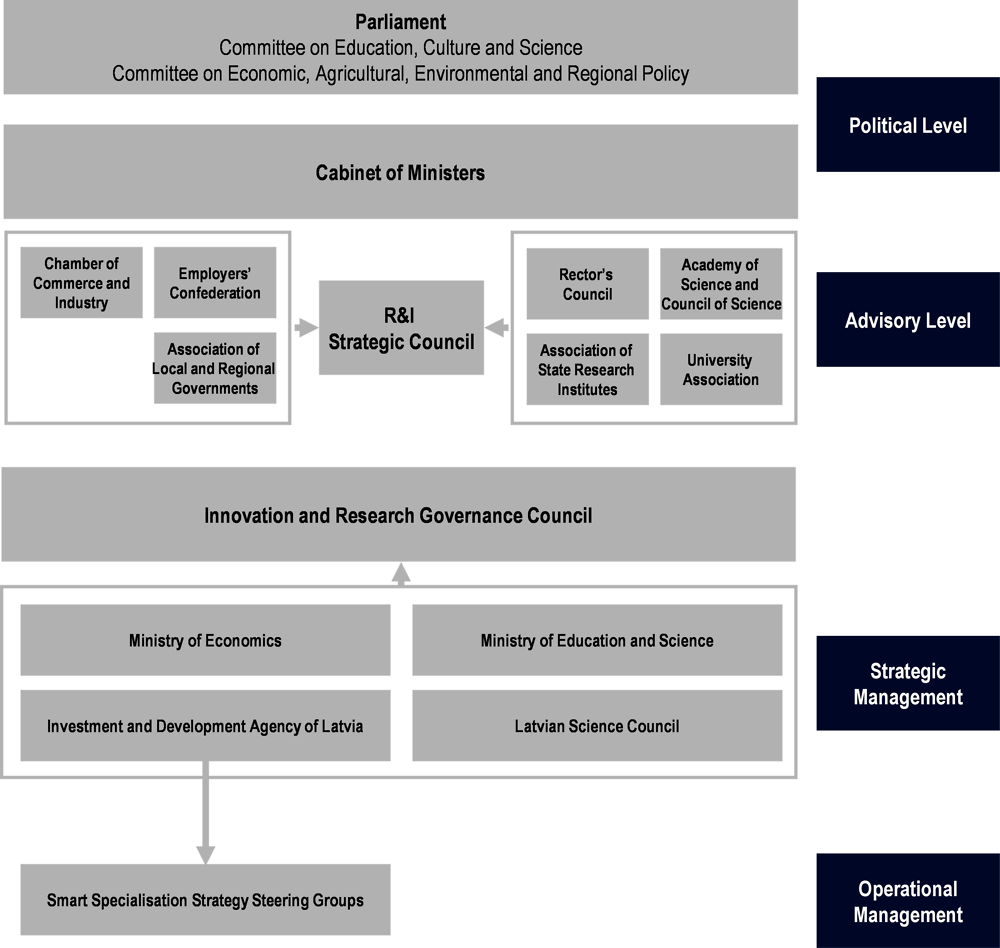

The governance structure of research and innovation policy in Latvia is comprised of a political layer responsible for high-level steering and oversight and a policy and administrative layer responsible for strategic management. Figure 3.6 illustrates this governance structure and the various bodies involved. At the political level, the Cabinet of Ministers and Parliament are the two institutions making high-level decisions on research and innovation policy, for example, the priority research directions and deciding the budget available for this policy area. Parliamentary committees may initiate discussions and invite ministers and civil servants to report on the progress in various research and innovation policy topics. The Cabinet of Ministers approves regulations related to the policy.

In 2014, Latvia established a Research and Innovation Strategic Council that provides advice to the Cabinet of Ministers and the Parliament. The Prime Minister chairs the Council and takes initiative to convene Council meetings bringing together a number of key research and innovation actors. Ministers participate according to the topics discussed. Higher education institutions, public research organisations, the Academy of Science and organisations representing businesses and local governments are also members of the Council (EC, 2019[13]). While the Council is designed as a strategic coordinating institution providing a platform for discussing major policy decisions, its actual activity has been minimal. Between 2018 and 2020, the Council did not hold any meetings. This shows that the body’s de facto influence in the innovation space is limited.

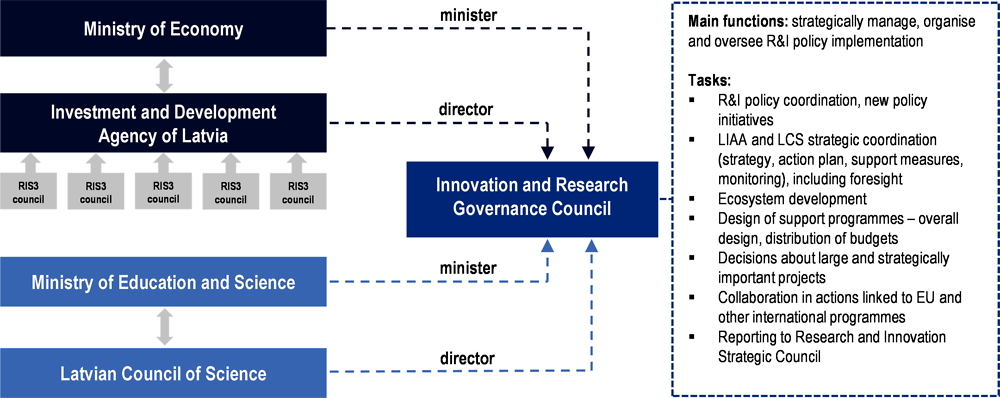

On the administrative level, there has been a recent change in Latvia’s governance structure. In 2022, Latvia created the Innovation and Research Governance Council to strengthen a collaborative management of the research and innovation system. The Council will support triple helix collaboration by identifying joint activities, facilitating information exchange and mobilising support mechanisms (Latvian Ministry of Economics, 2022[14]). The Council reports to the Research and Innovation Strategic Council and brings together two ministries that have been instrumental to Latvia’s R&I system, the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) and the Ministry of Economics (MoE), as well as two institutions: the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA) and the Latvian Council of Science. The Ministry of Education and Science leads research and higher education policy planning, designs key policy documents and coordinates the implementation of policy measures. Furthermore, the MoES designs and monitors the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) programmes for research support. The Ministry of Economics is responsible for the development of policies regarding business support and innovation. The departments of the MoE are working in close collaboration with the EU Structural Funds to design, introduce and supervise Structural Funds programmes and projects related to enterprise support and innovation. Due to a recent change, the formal responsibility of designing, implementing and monitoring the Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) lies in the hands of both Ministries – the MoES used to have a more pronounced role with the MoE supporting.

A subordinate institution to each ministry takes part in the Innovation and Research Government Council: the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA) (linked to the MoE) and the Latvian Council of Science (LCS) (linked to the MoES). LIAA facilitates foreign investment and promotes competitiveness and business development of Latvian entrepreneurs. In 2004, LIAA became one of the main funding agencies responsible for administering ESIF programmes and implementing state support programmes in entrepreneurship and innovation. In recent years, LIAA has taken on a stronger role in the innovation space, diffusing innovation and connecting stakeholders in business, academia and research. The Latvian Council of Science, since July 2020, has been an institution of direct administration under the supervision of the Minister for Education and Science. The LCS aims to implement the state science and technology development policy, and to ensure expertise, implementation and supervision of research programmes and projects financed from the state budget, as well as from the ESIF and other foreign financial instruments delegated in regulatory enactments (Latvian Cabinet of Ministers, 2020[15]).

Figure 3.6. Governance of Latvian R&I system as of September 2022

Latvia created the new Council (see overview in Figure 3.7) to strengthen a collaborative management approach of the research and innovation system. Compared to the R&I Council at advisory level, the Innovation and Research Governance Council will play a more operational role and aims to support collaboration between industry, academia and public sector institutions. This includes the identification and strategic coordination of joint activities, facilitating information exchange and mobilising relevant support. The Council will assist entrepreneurs in attracting funding; support Latvian businesses in increasing exports and enable collaboration between companies and researchers. The Council will also enable more targeted exchange of information between LIAA and LCS. For example, the Latvian Science Council will share insights into its work supporting research projects at low technology readiness levels with LIAA in order to identify potential commercialisation activities. Similarly, LIAA plans to gather intelligence on the research needs of businesses and feed it back to the LCS. Another topic the Council will oversee is LIAA’s work with innovation ecosystems; see more in the section below. Overall, the Council is a mechanism to channel needs identified on the ground, such as through ecosystem or academic collaboration, to the attention of policymakers. The de facto influence and level of engagement of the Council remain to manifest over time.

Figure 3.7. Structure and functions of the Innovation and Research Governance Council

Source: Based on Latvian Ministry of Economics/Ministry of Education and Science (n.d.[16]), “Presentation to the Research and Innovation Strategic Council”, https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/latvijas-petniecibas-un-inovacijas-strategiskas-padomes-sedes.

Alongside the governance of research and innovation policy, the promotion of innovation in the public sector is of increasing importance in Latvia. In 2018, the Latvian Innovation Laboratory was set up at the State Chancellery. The year 2023 marks the start of its third distinct phase of operation, providing mentoring and consulting services on innovative methodologies for public policy design, piloting and implementation. The Innovation Laboratory is the main driver for public administration innovation, seeking to build a user-centred mindset across the Latvian public sector innovation ecosystem and continuously upskill public administration on innovative methodologies for policymaking. It promotes cross-sectoral, cross-institutional and cross-departmental collaboration in development of policies and services.

A scan of the Innovation System of the Public Service of Latvia was carried out by the OECD in 2021 in collaboration with the Innovation Laboratory (OECD, 2021[17]). Based on the conclusions of the scan, as part of the Public Administration Modernisation Plan 2023-2027, the Innovation Laboratory will lead the development of public administration innovation policy in Latvia. In 2023, the Innovation Laboratory is undertaking a technical support instrument (TSI) project supported by the European Commission’s DG Reform to build innovative capacity in the public administration, capitalise on the existing infrastructure of the Innovation Laboratory and expand its impact to both national and municipal levels. A three-year Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF) financed project will focus on the development of a national innovation ecosystem of public administration, establishing fully fledged legal and operational infrastructures for innovation in public administration.

Policy framework and innovation and research initiatives

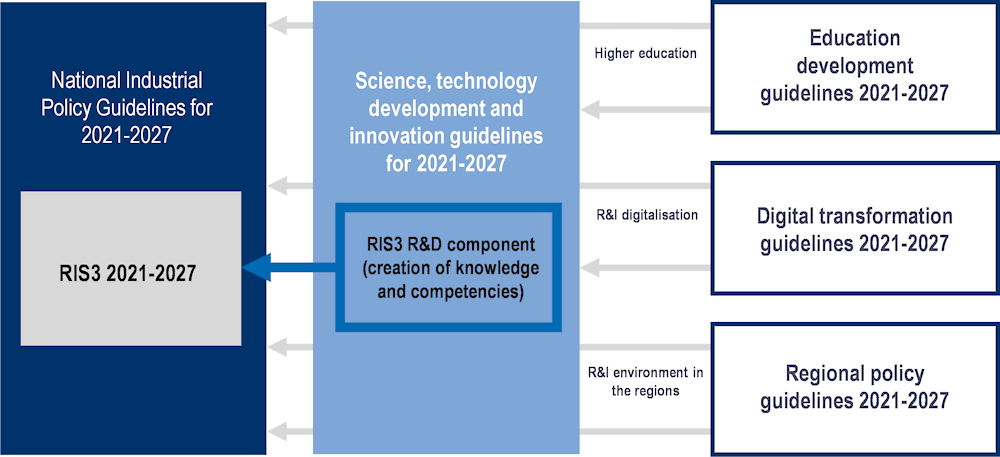

Both the Ministry of Education and Science and the Ministry of Economics set the direction of research and innovation policy in their respective policy fields in Latvia. Figure 3.8 shows the key policy planning documents comprising the framework that guides policy measures. Key documents are the National Industrial Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 developed by the Ministry of Economics and the Guidelines for Science, Technology and Innovation for 2021-2027 developed by the Ministry of Education and Science. Since the planning period of 2021, the National Industrial Policy Guidelines are the key document defining focus areas for research, development, and innovation funding related to Latvia’s Smart Specialisation Areas (RIS3). While the Ministry of Economics is the main responsible authority for their implementation, all line ministries are jointly responsible for ensuring the implementation of tasks related to their policy area as set out in the guidelines. Policy planning documents in higher education, digitalisation and regional development horizontally feed into R&I policymaking, and, where possible, the R&I policy framework incorporates dimensions from these policy areas.

The high-level policy framework (National Industrial Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027) emphasises that innovation ecosystems can play an important role in achieving R&I policy objectives. The guidelines describe the mechanisms for developing ecosystem strategy and assign new tasks to LIAA in coordinating the ecosystems. Nonetheless, the funding mix does not include dedicated resources to support these activities. International experts have pointed to the insufficient scale of programmes supporting research-industry links and missing support to explore industry needs in Latvia and beyond. They have made recommendations to better institutionalise collaboration with industry (Arnold, Knee and Vingre, 2021[18]). Among Latvian stakeholders, the need to strengthen cooperation between business and academia in order to achieve effective tech transfer and interconnection is widely acknowledge (OECD, 2022[7]) d.

Figure 3.8. Key policy planning documents providing policy framework

Source: Based on Latvian Ministry of Economics/Ministry of Education and Science (n.d.[16]), “Presentation to the Research and Innovation Strategic Council”, https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/latvijas-petniecibas-un-inovacijas-strategiskas-padomes-sedes.

Table 3.1 below lists the key R&I policy measures that have been agreed upon under the European Structural Investment Fund (ESIF) for the funding period of 2021-2027. The availability of funding varies from programme to programme – certain measures have budgets attached to them while others still need further development before a funding call can be launched. The ESIF sets specific requirements for projects to align with smart specialisation areas (RIS3). On the Latvian side, the Central Finance and Contracting Agency (CFCA) and the Development Finance Institution, ALTUM, manage the funding administration of several R&I ESIF programmes. They are not involved in any broader support activities (see more in section 2.3.), the strategic coordination lies with the Ministry of Education and Science or the Ministry of Economics and partly LIAA.

For Latvia’s work supporting innovation ecosystem, the listed measures represent the available pathways for ecosystem partners to secure government funding. Some measures target only individual beneficiaries (companies or research organisations), while some can be used to fund the development of collaborative projects such as the development of new products and technologies in RIS3 specialisation areas. The latter, thus, offer an opportunity to fund initiatives that ecosystem members collectively identified. However, none of the measures explicitly supports ecosystem development and orchestration activities, which appears to be the missing element in the overall R&I policy mix.

Table 3.1. Overview of key R&I policy measures in funding period 2021-27

|

Measure |

Responsible institutions |

Type of support |

|---|---|---|

|

Development of new products and technologies in RIS3 specialisation areas |

MoE and CFCA |

Grants to companies and research institutions for individual and collaborative R&D projects. |

|

Support for the development of entrepreneurship |

MoE and LIAA |

Incubators Training (mini-MBA) Support for export activities Innovation vouchers |

|

Acquisition of innovative equipment |

MoE and ALTUM |

Loans for purchase of equipment and training of employees to operate the equipment |

|

Loans for technology development |

MoE and ALTUM |

Loans to support risky technology development and prototyping |

|

Loans for transfer of modern technologies |

MoE and ALTUM |

Loans for purchase of modern technologies in RIS3 areas |

|

Guarantees and export guarantees |

MoE and ALTUM |

Guarantees (for investment loans, leasing) and export guarantees |

|

Loans for business start-ups |

MoE and ALTUM |

Loans for investment Business angels fund |

|

Support for venture capital funds |

MoE and ALTUM |

Investment in several venture capital funds to support growth of SMEs |

|

RIS3 research and innovation centres |

MoES |

Developing research infrastructure in RIS3 specialisation areas |

|

Practical research projects |

MoES |

Fundamental and applied research, experimental development, IP establishment |

|

Mobility, exchange of experience and cooperation activities to improve international competitiveness of science |

MoES |

Stipends and grants for experienced researchers and postdoctoral researchers in Latvia and diaspora |

|

Support for participation in HORIZON programme |

MoES |

Co-funding to HORIZON and functioning of National Contact Point |

|

Grants for students, doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers |

MoES |

Innovation programmes for students and research grants for doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers |

Recent systemic reforms in Latvia’s research and innovation system

Latvia implemented two types of reforms in the field of research and innovation over the past years – R&I governance reforms and research funding system reforms. The governance reforms affect both the system's 'research' and 'innovation' approaches while research funding system reforms have had a more significant effect on research institutions. The two nonetheless remain interlinked as performance of research institutions is crucial for successful industry-academia collaboration as an essential part of the R&I system. In recent years, there have not been any significant reforms of innovation policies.

R&I governance reforms

As described above, both the Ministry of Economics and the Ministry Education and Science are in charge of the R&I system. No single organisation or body was in charge of strategic steering and a systemic perspective in the past. This has partly changed due to the introduction of the RIS3, as the Commission requires Latvia to develop a systemic view on achieving defined goals as part of their funding efforts (EC, 2018[8]). It is expected that the creation of the Innovation and Research Governance Council in 2022, as described above, will additionally bring opportunities to better coordinate efforts, involving both the main institutions at policy-making level (the two ministries) as well as the ones at policy implementation level (LIAA and LCS).

The implementation of R&I policy is in the hands of various organisations. In addition to LIAA and LCS, the Central Finance and Contracting Agency (CFCA) manages several essential R&I ESIF programmes. This entails that CFCA organises funding calls, reviews submissions and organises contractual arrangements. At the same time, LIAA and LCS are in charge of building capacity of R&I stakeholders and creating links between industry and academia. LIAA is also responsible for coordinating the innovation ecosystems (see further information below). Thus, different institutions engage with R&I stakeholders for various purposes, and beneficiaries of policy efforts do not have a single contact point in government when needing assistance. In the perception of some stakeholders interviewed, dispersed responsibility can hinder Latvia’s ability to build institutional capacity to support R&I stakeholders and can be a barrier to providing high-quality funding opportunities to stakeholders.

Regarding the State Research Programmes, there have been efforts made to ensure a broader range of research initiatives. Sectoral ministries have the option and budget to launch their own programmes in their policy fields since 2018, when previously only the Ministry of Education and Science could plan and implement such programmes (EC, 2018[8]). Ministries make use of this opportunity to various degrees; some design their own State Research Programmes to support research in a particular area while others choose not to. For example, the Ministry of Economics designed a programme to fund energy research and the Ministry of Defence funds research on innovations in defence sector (Latvian Council of Science, 2022[19]).

Research funding system reforms

In 2014, an international assessment of Latvian research institutions and a World Bank evaluation of Latvia’s higher education funding model led to the initialisation of systemic reforms. Following World Bank recommendations, Latvia developed a new higher education financing model based on three pillars: Base financing, performance-based financing and innovation financing. This was designed to ensure a better balance between stability, performance, and innovation orientation (World Bank, 2014[20]). In addition, Latvia consolidated academic structures and streamlined governance structures in some institutions. The aim of the reforms was to promote the development of stable human capital in R&D by 2030, strengthen Latvia’s innovation capacity and to consolidate the science system (EC, 2018[8]).

The consolidation of research structures back in 2014 provided new mechanisms for allocating scientific funding. It increased the share of competitive research funding based on a set of performance criteria. This allowed allocating funding in a more selective way to those research institutions with the best results (EC, 2018[8]). The most recent international research assessment of research institutions4 found that the reform (and other developments) contributed to an overall improvement of research performance. This included an increase of publications in international journals, the extension of international collaboration networks, considerable investment in research infrastructure and better research management. Institutional mergers decreased the fragmentation of research activities with room for further improvements. The evaluation showed that the positive effects of merging of institutions as well as overall cultural shifts of the research field require significant time. For example, shifting the focus to internationally relevant research questions, building and sustaining international partnerships and shifting mindsets towards performance outcomes will still require future efforts (Arnold, Knee and Vingre, 2021[18]).

Latvia’s innovation ecosystem concept

The following section will examine a range of initiatives Latvia has launched in an effort to support collaborative innovation between Latvian stakeholders across industry, academia and the public sector. These include Latvia’s smart specialisation strategy and connected RIS3 ecosystems, collaboration platform initiatives such as clusters or competence centres, efforts to support mission-driven innovation and innovation ecosystem formation. The section will examine commonalities and differences between the approaches in order to identify potential synergies.

Smart Specialisation Strategy and RIS3 ecosystems

Developed as part of the reformed cohesion policy of the European Commission, Smart Specialisation is a strategy for economic transformation promoted by the European Union. It takes a place-based approach meaning that it aims to leverage assets available to regions and Member States. The strategy builds on the potential of ‘entrepreneurial discovery’ where the government allows for stakeholder involvement and empowers those actors most capable of realising their potential. The approach is designed to make more effective use of resources by identifying areas for regional research and innovation (R&I) specialisation.

Latvia first developed its RIS3 in 2014 as a response to the ex-ante conditionality for receiving the EU Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF). The main ambition of the European Commission for the RIS3 conditionality was to promote the concentration of public R&D investment in a selected number of R&I specialisation areas to create interregional comparative advantages for European regions. Latvian R&I policy makers also saw the necessity to use the EU Structural Funds available for the period 2014-2020 primarily to consolidate and strengthen the foundations of national research and innovation system and improve the R&I governance.

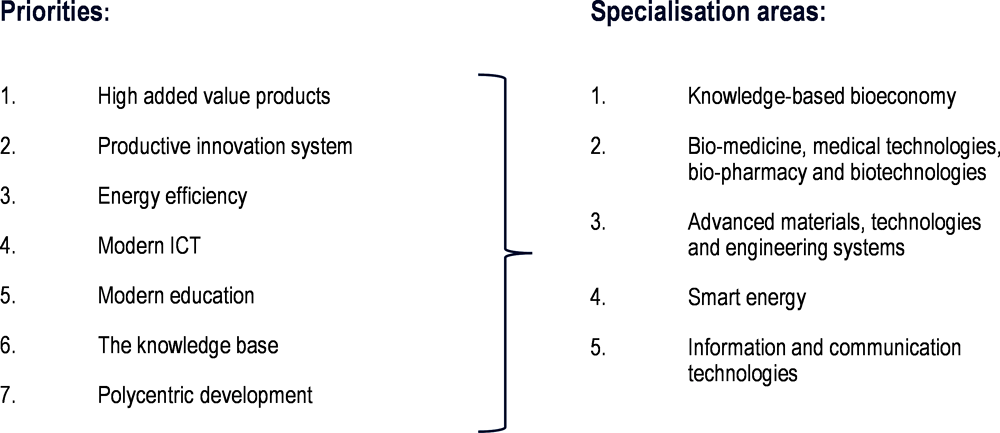

The Latvian RIS3 developed in 2014 presented a conceptually new and complex strategy providing a balanced and complementary support toolkit to strengthen the overall national innovation capacity. The Ministry of Education and Science led this initial strategy process. It involved a comprehensive analysis of sectoral export potential, assessment of knowledge capacity in Latvia and structured inputs from the stakeholder community as part of the Entrepreneurial Discovery Process (EDP). Latvia defined the objectives to initiative structural changes of production and export in traditional sectors, promote the growth in high added-value sectors (new products and services) and support sectors with horizontal impact and contribution to economic transformation. The strategy outlined seven investment priorities and five thematic specialisation areas as listed in Figure 3.9.

In 2015, the Latvian Ministry of Education and Science developed a more detailed description of the five thematic specialisation areas. This included the scale of each knowledge area, core challenges, existing public funds and regulations and most importantly the mapping of the main actors in each of the innovation ecosystems (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[21]). The Commission saw the five broad RIS3 thematic areas as vehicles for structuring ESIF and national R&I investments and in Latvia, they served as a point of reference of national strategic directions in research and innovation.

Figure 3.9. Priorities and specialisation areas of Latvian RIS3

Source: Latvian Ministry of Education and Science (2013[22]), About the Development of Smart Specialisation Strategy, https://www.izm.gov.lv/en/media/3748/download.

Up until 2020, Latvia’s implementation focus for the smart specialisation strategy was to strengthen scientific capacity of research institutions as well as enterprises and promote cooperation through various support programmes. This shifted with the second RIS3 Monitoring Report published in 2020. It concluded that although the EU Structural Funds in 2014-2020 and other R&I instruments had improved the innovative capacity of individual academic and industry institutions, the approach lacked an integrated approach to fostering innovation in the smart specialisation areas as a whole (Latvian Ministry of Education and Science, 2020[4]). This included promoting innovation by developing the physical, entrepreneurial, and legislative environment of the RIS3 areas to support innovation efforts (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]). The report called for more emphasis on strategic value chain development in the RIS3 niche areas through a structured dialogue with stakeholders and coordinated action plan, as well as changes in the RIS3 governance model.

From 2021 onwards, Latvia shifted the main responsibility for the RIS3 development, including the organisation of the Entrepreneurial Discovery Process, from the Ministry of Education and Science to the Ministry of Economics. This was a way to recognise the central role of the smart specialisation strategy in Latvia’s economic transformation. The Ministry of Education and Science retained its responsibility for matters related to scientific and educational capacity in RIS3 areas. This includes the development of and access to research infrastructure for technology transfer. Similar to the Ministry of Education and Science, other sectoral ministries remain involved in RIS3 development within the framework of their mandate.5 The National Industrial Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 also introduce the term 'RIS3 value chain ecosystem' and assigned responsibility for launching and coordinating these RIS3 ecosystems to LIAA. The guidelines explain that they are a collaboration between private, public and academic sectors in RIS3 specialisation areas and supplement or deliver key components to the products or services they provide, creating end product or service value (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]). The guidelines prescribe that each ecosystem defines and builds upon a jointly defined strategy. The ecosystem approach should build on:

A comprehensive mapping of the ecosystem and result in strategy development.

Coordination of joint activities for the ecosystem members.

In addition, the guidelines provide a draft outline of what each ecosystem strategy should include (e.g. R&D objectives, human resources objectives, internationalisation objectives, activities, performance indicators, etc.).

The Guidelines 2021-2027 confirmed the continued relevance of the five broad RIS3 areas, describing their importance for the Latvian economy as follows:

1. Knowledge intensive bio economy – Dominance of traditional industries in the national economy. The productivity and value-added per employee in agriculture, forestry, woodworking, food and drink industry in Latvia is below the EU average. To strengthen productivity and more resource intensive production, it is necessary to stimulate innovation in these sectors. Latvian research institutes have strong competences in multiple areas of bio economy, including sustainable and effective agriculture, innovative food and feed products, food safety, sustainable forestry and wood supply chains, research on bio resources, regional development.

2. Biomedicine, medical technologies, pharmaceuticals – Strong research potential as it is an important, competitive, and internationally recognised research field with rich tradition, scientific excellence and innovation activities. Thematically, biomedical research in Latvia covers both traditional medical research and clinical research, and increasingly digitalised healthcare.

3. Photonics and smart materials – Strong research potential with a particular importance for the transformation of the Latvian economy towards more value-added production. Topical thematic niches include implant materials, biomaterials, composite materials and polymers, think layers and coverages, machines, tools and systems, functional materials for photonics, electronics, nanotechnologies, nanocomposites and ceramics. The knowledge base in photonics and smart materials is mainly concentration in universities and state research institutions.

4. Smart energy and smart mobility – Efficient and user-cantered technologies and services, in particular in the areas of energy, transport and ICT, are a global trend and fundamental for sustainable economic activities and urban development. ICT and digital technologies are means to make cities more effective, accessible, and usable, simultaneously moving towards less CO2 emissions and adapting to climate change challenges.

5. Information and Communication Technologies – Horizontal impact on all other RIS3 areas. The impact of ICT sector on the national GDP is about 5%, a share that has significantly increased in the last 10 years. Latvian research potential in ICT lies in thematic niches such as electronics and robotics, algorithms and computer models, computer linguistics, data storage and transfer systems, earth observation, artificial intelligence and machine learning, education technologies and digitalisation, as well as cybersecurity. (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]). Since 2018, Latvia launched more targeted activities to develop strategic value chain ecosystems in RIS3 thematic areas through demonstration, piloting and testing activities. As part of a pilot project, the Ministry of Economics and LIAA developed three RIS3 ecosystem strategies in 2019-2020, feeding in expertise of other ministries and stakeholders. These ecosystems are:

Smart cities with a pilot theme smart mobility.

Smart materials with a pilot theme photonics.

Biomedicine with a pilot theme precision medicine.

The goal defined in the National Industrial Guidelines 2021-2027 is to select at least five strategic value chain ecosystems (one per RIS3 thematic area) placing emphasis on targeted ecosystem governance involving public, private and academic stakeholders. Latvia plans the implementation of its smart specialisation strategy through these ecosystems, building on synergies between scientific excellence and industrial needs. The ecosystem strategies shall serve as guidelines to ensure an integrated innovation approach: from identification and analysis of value chains to improvement of regulatory environment, internationalisation, attraction of investment, development of human resources and strategic governance. RIS3 ecosystem strategies are expected to map the existing competences and support tools complementing them with missing capabilities and functions. Forward-looking and foresight approaches will ensure the modelling of long-term development perspectives.

Latvia will develop annual action plans based on the ecosystem strategies and dynamically review them to account for emerging local and global developments and trends. LIAA is tasked with the development of the initial long-term RIS3 development strategies in each of the five specialisation areas. Dedicated RIS3 ecosystem strategic governance leader groups will develop annual action plans that will be coordinated with ecosystem partners. The National Industrial Guidelines 2021-2027 foresee two main activities as part of the RIS3 ecosystem value chain approach:

1. Mapping: analysis of the existing situation and strategy definition.

2. Coordination: involving a range of concrete and mutually connected activities.

Other collaboration platform initiatives

Latvia undertakes other initiatives that promote the development of collaboration platforms, similar to the ecosystem approach. Among these initiatives are

Competence centres.

Clusters.

Industry associations.

Regional initiatives of the Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) as part of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).

Table 3.2 provides a concise overview on distinctions between these initiatives. The following section will describe the work done in recent years under each of the programmes, their strategic direction and focus areas. This allows to identify synergies and differences between the various initiatives Latvia takes to enable collaboration platform initiatives. The insights described are derived from available government documents as well as a series of personal interview with key policymakers in the R&I landscape.

Table 3.2. Initiatives that promote links among innovation ecosystem actors

|

Programmes/initiatives |

Objectives |

Funding |

Responsible organisation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Competence centres |

Programme to increase the competitiveness of Latvian industry through fostering collaboration between research and businesses by supporting applied research projects for the development of new products and technologies. |

In the period 2014-2020, around EUR 80m of which 80% came from the European Structural Funds |

Ministry of Economics |

|

Cluster programme |

Programme promotes the creation of cooperation networks among industry, research organisations, higher education organisations and other entities that operate in the same sector, product or service niches or value chains to promote industrial competitiveness, export of higher added-value production. |

In the period 2014-2020, around EUR 6.2m of which 85% came from the European Structural Funds |

Ministry of Economics |

|

Industry associations |

Public, non-governmental organisations that join businesses in dedicated sectoral areas to help developing the industry by addressing sectoral challenges and representing the industry voice in policy-making initiatives and governance processes. |

Membership fees and other funding sources |

Independent |

|

EIT KIC Regional Innovation Scheme |

European programme aiming to build pan-European innovation ecosystems in thematic challenge areas through integration of the ‘knowledge triangle’ – business, research, education actors, as well as public administrations. |

Annual budgets awarded by individual KICs for implementation of defined activities |

Riga Technical University as key coordinator of the scheme in Latvia |

During the previous funding period, (2014-2020) the Ministry of Economics funded eight competence centres as an effort to increase the Latvian industry’s competitiveness. The programme fosters collaboration between research and businesses by implementing applied research projects for the development of new products and technologies. The overall programme budget amounted to EUR 80m, of which 80% came from the EU Structural Funds and 20% from private co-financing (Latvian Ministry of Economics, 2018[23]). The competence centres are in the areas of direct relevance to RIS3:

Forestry and woodworking.

Agriculture and food.

Biomedicine, medical technologies, biopharma and biotechnologies.

Smart materials.

Modern production technologies and engineering systems.

Machinery (electronics).

ICT.

Smart energy.

The competence centres have been an overall Latvian success story. A review of the R&I funding system in 2018 by the H2020 Policy Support Facility expert team assessed that they were the most successful instruments in Latvia so far in creating bridges between research centres and industry (EC, 2018[8]). In particular, the clear funding mechanisms and their orientation towards industry needs was fruitful. The centres work with almost all of Latvia’s largest and most active enterprises undertaking research and development activities. They also collaborate closely with the respective industry associations of each field. Through this interconnectedness they have de facto become an essential sectoral discussion platform allowing for exchange on R&I (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]).

Another support instrument connected to ecosystem formation is the cluster programme. From 2014-2020 Latvia implemented 14 cluster projects with a total budget of EUR 6.2m, 85% funded by EU Structural Funds. Cluster activities contribute to the realisation of RIS3 goals. The Ministry of Economics assessed that the clusters successfully implemented export promotion activities and accumulated the necessary administrative capacities for their realisation (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]). The expert assessment performed in the framework of Interreg Europe project CLUSTERS3 however pointed out that the structure of the programme lacked effective triple helix implementation in practice. In addition, large enterprises were not sufficiently engaged to ensure successful cluster operations. According to the experts, the cluster programme funding was insufficient to reach defined ambitions and objectives and cluster membership did not reach the critical mass (Latvian Ministry of Economics, 2018[24]).

A long-standing mechanism for industry collaboration networks in Latvia are sectoral industry associations, which foster collaboration between enterprises in concrete domains (based on NACE6 classification). Historically, the strongest associations existed in classical export-oriented economic sectors such as woodworking, metalworking, electronics and pharmaceuticals. This may evolve in the future. While industry associations play an important role in the work of competence centres, clusters and other innovation support programmes, there is not always an alignment of efforts. Each of the funding programmes has distinct goals and activities, which can create bottlenecks for technology transfer and knowledge absorption by industry. As a result, the Ministry of Economics recognised in the current funding period that there is a need to create a more holistic support mechanism to promote the achievement of RIS3 objectives (Government of Latvia, 2021[5]).

Latvia is also part of the pan-European innovation ecosystem building efforts through the association to the Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) of the European Institute for Innovation and Technology (EIT). Riga Technical University (RTU) has taken up an active lead as the main Latvian partner engaging with the outreach scheme of four KICs – EIT Climate-KIC, EIT Food, EIT Urban Mobility and EIT Raw Materials. The cooperation with the EIT started in 2016, when KICs launched partnership schemes dedicated specifically to modest and moderate innovator countries in Europe. Since then, the Innovation Ecosystem Development Unit of the RTU Knowledge and Innovation Centre has grown substantially in size and mandate. It is taking a hands-on approach to connecting Latvian innovation ecosystem partners with European counterparts. RTU has become a recognised partner for KICs and, in essence, performs the role of a central entry point for moderating networking, information on upcoming calls and support opportunities between KICs and Latvian R&I ecosystems.

Developing work on mission-oriented innovation

Another work stream that touches upon elements of ecosystem mobilisation and co-creation of several organisation relates to missions. The work on mission-oriented innovation in Latvia stems from another strand of work that LIAA was tasked with in 2021 – the development of Latvia’s national brand image. The working group in charge of ideation assessed that a state’s brand is closely associated with its actions, and less the result of communication efforts. Inspired by the mission-oriented innovation approach that gained popularity across European countries (in particular the work of Mazzucato (2018[25])), the working group concluded that goal orientation needed to be a priority. To improve Latvia’s international image as a small European country, the country needs to align stakeholders to solve societal challenges of local and global relevance. This mission-driven approach captures the essence of how various organisations and sectors can achieve strategic alignment in the name of an ambitious, inspiring and joint goal (Mazzucato, 2018[25]; OECD, 2021[26]).

Selecting a suitable mission to feed into the branding exercise took place in 2021 over a six-month period. The parameters of the mission theme were its local and global importance, involvement a wide range of diverse stakeholders and uptake of external knowledge in its implementation. The team sourced and crystallised ideas in the form of surveys, interviews, workshops and other discussion and deliberation platforms. Finally, they selected a mission on clean water, water innovation and technologies: mission Sea 2030, similar to the EU mission “Restore our Ocean and Waters by 2030”. Other potential ideas related to the EU Cancer mission or forestry, but these either faced the resistance of companies unwilling to take part in open innovation or had a potential negative image. “Mission Sea 2030” covers all types of water innovation, water resource preservation technologies and stresses the critical importance of clean water technologies for a sustainable future.

One year after LIAA adopted “Mission Sea 2030”, first signs indicate that the theme will gain traction. There is a notable progress in research achievements in related fields and some enterprises have adopted investment projects connected to the mission goals. In September 2022, the RIS3 Innovation Council plans to adopt more concrete mission KPIs to assess the achievements of the mission-oriented approach across various dimensions. The current mission implementation mechanism is a consistent and dedicated streamlining of mission objectives across policy initiatives, ecosystem objectives, and action plans of a wide range of stakeholders. LIAA is also preparing dedicated communication campaigns to ‘translate’ the core ideas of the mission approach for wider society. Similar deliberation activities will launch in the future to select one or two additional missions in other thematic areas. This would allow to engage a wider range of stakeholders and build on the momentum of this new model of collaboration.

Synergies and inconsistencies of ecosystem and other collaboration platform approaches

While the described programmes all have an element supporting collaborative innovation, they each exist in a different context and have their own programme logic. The main commonality between most approaches is Latvia’s commitment to its smart specialisation strategy:

The competence centre and cluster programme implemented in the period 2014-2020 targeted the five original RIS3 domains; hence, thematically there is some alignment between the broad smart specialisation areas and concrete collaboration platforms among the relevant actors. Competence centre and cluster initiatives have formed important links and connections that pre-date the start of the ecosystem initiatives.

Industry associations have a strong sectoral orientation and are recognised lobby organisations in economic and industrial policy deliberations. They are frequent go-to partners for consultations and gathering of stakeholder inputs, including for the RIS3 entrepreneurial discovery process. Nonetheless, it is unclear if they play a facilitating role in the formation of cross-sectoral initiatives or solely remain advocates of specific sectoral policy interests. The exact role could differ among the various organisations.

Contrary to the other programmes, the EIT KIC regional initiatives have rather limited connection to the RIS3 ecosystem approach. While the representatives of Riga Technical University are aware of all the existing innovation support instruments at national level, synergies between the EIT KICs and national RIS3 strategy have been almost non-existent. The innovation support instruments implemented by LIAA have distinct objectives rather than a focus on how the programme would support beneficiaries along the entire innovation journey from the idea to market rollout. The EIT KICs tackle this aspect well at European level. Due to the fragmentation of programme objectives, defined goals, criteria for application and other, local synergies with the KIC initiatives are hard to discern. Beneficiaries also recognise the substantial effort needed to apply to LIAA programmes noting that funding frequently remains insufficient (or does not cover a full prototype development process). Meanwhile, the RTU (Riga Technical University) Knowledge and Innovation Centre employs almost 60 people on a project basis and gradually accumulates competences in providing innovation support services. Through interactions with other KIC ecosystems, they bring a much-needed insight into European-level developments into the national R&I landscape. These can offer important macroeconomic knowledge for defining RIS3 strategic niches. At present, the interviewees share the impression that ministries do not sufficiently recognise the value generated by RTU networking and engagement activities for the formulation of RIS3 strategy. In large parts, this is due to the complexity of the EIT as an instrument that forges pan-European cross-sectoral innovation ecosystems tackling defined societal challenges.

Due to its recent initiation, interconnections between the missions-driven approach by LIAA and the smart specialisation strategy remain to be seen.

LIAA’s role in supporting innovation ecosystems

The following section looks at the role LIAA has played in supporting ecosystems to develop and flourish. It examines the reorganisation of the institution, its role in the R&I policy and implementation space and the steps taken to coordinate RIS3 ecosystems. The observations stem from continuous exchanges with LIAA, several joint activities with ecosystem partners and a series of interviews with key policymakers in the agency, other institutions and ministries.

The organisation’s evolving role in Latvia’s innovation policy landscape

LIAA has a mandate to increase export and competitiveness of Latvian companies, facilitate foreign investment and implement tourism development and innovation policies. In addition to its role in export and investment promotion, the agency is in charge of implementing ESIF programmes for business support since 2004. With the 2007-2013 funding period, the programmes became gradually more complex and started focusing on building links between key innovation institutions, industry and academia. The agency implemented new forms of funding instruments including support for competence centres and clusters, aimed to enable technology transfer. LIAA also started experimenting with various forms of funding instruments to support these programmes. These were the first instances in which the agency evolved from its role as a funding distributor to introducing new mechanisms to facilitate strategic collaboration in the innovation space. This continued in the ESIF funding period 2014-2020 when Latvia first launched its smart specialisation strategy in the RIS3 areas. Up until the current funding period, LIAA did not hold a strategic mandate to ensure meeting the RIS3 framework and objectives. While the agency did administer funding measures with a contribution to RIS3 targets, it was unable to undertake strategic planning and coordination of RIS3 activities.

As outlined above, along with planning the current policy and funding period (2021-2027), LIAA obtained a new role in coordinating the RIS3 ecosystems. The agency was assigned responsibility for granting support to ecosystems. This entails a comprehensive mapping of each ecosystem to feed into strategy development as well as the coordination of joint activities of ecosystem members.

For LIAA, this responsibility marked a turning point in the agency’s role within Latvia’s R&I system. LIAA is now responsible for what has been identified as an essential part of Latvia’s innovation approach: launching and coordinating RIS3 ecosystems, including the development of strategy and elements of orchestration.

LIAA’s current mandate and resources to fulfil its role

To fulfil its coordinating role, LIAA is trying to sustain ongoing dialogue between ecosystem members and mapping competencies, ideas and potential collaborations. LIAA also reviews the RIS3 strategies and aims to include specific activities to support the achievement of those activities in the organisation's activity plan. There is an understanding among LIAA leadership that the agency can work not only as an administrator of business support but can also have an active role in driving the development of large industrial projects. That includes an active role in seeking funding opportunities and promoting Latvian businesses internationally. However, this also requires the active support and participation of industry players representing the ecosystem. Based on consultations with LIAA, the Ministry of Economics and members of several ecosystems, it appears that the parties are still on their way to understanding their roles and working arrangements that would best deliver the objectives defined in the policy planning documents. This also includes the evolving relationship between the agency and the steering mechanism of its line ministry.

The National Industrial Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 delegate a complex and resource-intensive task to LIAA. LIAA plans to assign a team of five people to coordinate each ecosystem. However, only the core coordinator would work on this task full-time. The other four team members are representatives of LIAA technology scout and start-up units. However, these staff members have other daily responsibilities and contribution to RIS3 ecosystem coordination is only one of several tasks. Furthermore, LIAA plans to engage representatives from the Investment Department and Export Promotion Department. In addition to staff effort, LIAA has a budget of EUR 300 000 over five years to support ecosystem strategy development. LIAA can use this funding to digitalise coordination activities, collect data or perform other support activities.

Coordination or orchestration of innovation ecosystems is essential for any ecosystem to produce outputs and succeed. Ecosystem coordinators must align partners and identify joint value propositions, and this task requires specific competencies, skills and tools. Furthermore, ecosystem coordinators need to provide support to set a strategic direction and define priorities. In addition, the coordinators must understand the particular industry's national and international landscape and possess orchestration skills. Trust between ecosystem partners and coordinators has been identified as a crucial element in ecosystem success, and building trust takes time. LIAA as a public sector organisation has a different standing than a stakeholder from academia or the private sector who may have pre-existing relationships with ecosystem partners due to past collaborations. This may mean that LIAA needs to invest into building trust-based relationships in order to efficiently perform the coordinator role. Finally, policymakers also need to consider having an exit strategy for ecosystem support. That is currently not defined. The ecosystem coordination activities are linked to the six-year policy and funding planning period, but there is no clear strategy for what the role of LIAA will be after this period.

Based on consultations with policymakers, LIAA and ecosystem members, LIAA currently does not fully have the resources required to meet the expectations placed on the organisation by high-level policy objectives. In addition, LIAA is a public administration organisation with minimal options to recruit employees with the knowledge, skills and experience required to orchestrate innovation ecosystems successfully. Interview partners shared their concern that the renumeration that LIAA can offer is a barrier to attracting staff with the right profile to conduct the complex innovation ecosystem coordination task. The ambitious policy objectives in innovation ecosystem building currently are not supported by appropriate dedicated resources to support the policy implementation. If unchanged, the progress of innovation ecosystem development will be slow (or none), and thus it is unlikely innovation ecosystems will produce ecosystem outputs and benefits for their members.

Based on international experience, although the government has a significant role in innovation ecosystem initiation (by providing funding) and can be an active player in ecosystem orchestration, industry and academia usually lead the ecosystem work. Governments either provide funding to ecosystem members to support their orchestration efforts or hires external neutral service providers with expertise in the area. For example, Business Finland ecosystem funding beneficiaries work with specific industry associations that take the lead in ecosystem coordination. In addition, government funding for ecosystem coordination is linked to specific performance indicators that ecosystems must meet to receive ecosystem orchestration support. The role of the government innovation agencies (as LIAA) in these models is to ensure quality services are delivered to the ecosystems, monitor the ecosystem development progress, and facilitate peer exchange and learning between different ecosystems.

International reviews of innovation ecosystem orchestration also highlighted that government organisations recognise the role of innovation ecosystems in R&I development and act to initiate ecosystem creation and development. But the review did not find examples of ecosystems that government organisations coordinate. It takes specific skills and knowledge to orchestrate an innovation ecosystem. It is believed that industry needs-driven ecosystems should be orchestrated by organisations that possess the skills and knowledge and are R&I producers. For example, innovation agencies like Business Finland, Vinnova, and Innovate UK have the resources to recruit staff with the necessary expertise. Still, these organisations do not directly facilitate ecosystems but provide a framework, oversee, and monitor the process.

References

[18] Arnold, E., P. Knee and A. Vingre (2021), International Evaluation of Scientific Institutions Activity, https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/media/10721/download.

[11] CSCC (2020), Development Plan of Latvia for 2021-2027, Latvian Cross-Sectoral Coordination Center, https://www.pkc.gov.lv/sites/default/files/inline-files/NAP2027__ENG.pdf.

[3] CSCC (2012), National Development Plan of Latvia for 2014-2020, Latvian Cross-Sectoral Coordination Center, https://pkc.gov.lv/images/NAP2020%20dokumenti/NDP2020_English_Final.pdf.

[2] EC (2022), 2022 Country Report - Latvia - Accompanying the Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2022 National Reform Programme of Latvia and Delivering a Council Opinion on the 2022 Stability Programme of Latvia, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/system/files/2022-european-semester-country-report-latvia_en.pdf.

[9] EC (2021), European Innovation Scoreboard 2021, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/46013/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

[10] EC (2021), European Innovation Scoreboard 2021 - Latvia, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/45922.

[13] EC (2019), Specific Support on the Development of the Human Capital for Research and Innovation in Latvia: Background Report, Background Report, European Commission, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/264675.

[8] EC (2018), The Latvian Research Funding System: Specific Support to Latvia: Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility, European Commission, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/3392.

[27] European Council (2000), Presidency Conclusions - Lisbon European Council - 23 and 24 March 2000, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/00100-r1.en0.htm.

[5] Government of Latvia (2021), Guidelines for the National Industrial Policy for 2021-2027, Government of Latvia, https://m.likumi.lv/doc.php?id=321037#.

[15] Latvian Cabinet of Ministers (2020), Regulations of the Latvian Science Council, https://likumi.lv/ta/id/315785.

[19] Latvian Council of Science (2022), State Research Programmes, https://lzp.gov.lv/programmas/valsts-petijumu-programmas/ (accessed on 27 September 2022).

[14] Latvian Ministry of Economics (2022), “A council for management of innovation and research has been established”, https://www.em.gov.lv/en/article/council-management-innovation-and-research-has-been-established?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F.

[6] Latvian Ministry of Economics (2021), Latvia’s Macroeconomic Overview, https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/media/11553/download.

[24] Latvian Ministry of Economics (2018), CLUSTERS3 - Leveraging Cluster Policies for Successful Implementation of RIS3 - Action Plan, https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1530858025.pdf.

[23] Latvian Ministry of Economics (2018), “Kompetences centri turpina attīstīt jaunus produktus un tehnoloģijas”, https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/kompetences-centri-turpina-attistit-jaunus-produktus-un-tehnologijas.

[16] Latvian Ministry of Economics/Ministry of Education and Science (n.d.), “Presentation to the Research and Innovation Strategic Council”, https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/latvijas-petniecibas-un-inovacijas-strategiskas-padomes-sedes.

[21] Latvian Ministry of Education and Science (2020), Smart Specialisation Strategy, https://www.izm.gov.lv/en/smart-specialisation-strategy.

[4] Latvian Ministry of Education and Science (2020), Smart Specialisation Strategy Monitoring, Second Report, https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/media/5998/download.

[22] Latvian Ministry of Education and Science (2013), About the Development of Smart Specialisation Strategy, Informative Report, https://www.izm.gov.lv/en/media/3748/download.

[25] Mazzucato, M. (2018), Mission-oriented Research and Innovation in the European Union: A Problem-solving Approach to Fuel Innovation-led Growth, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/mazzucato_report_2018.pdf.

[7] OECD (2022), Innovation Diffusion in Latvia: A Regional Approach, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/Innovation-Diffusion-Latvia.pdf.

[1] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Surveys: Latvia 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c0113448-en.

[26] OECD (2021), Public Sector Innovation Facets: Mission-oriented Innovation, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/publications/facets-mission/.

[17] OECD (2021), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Latvia, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Country-Scan-of-Latvia.pdf.

[12] OECD (n.d.), Gross Domestic Spending on R&D, OECD, Paris, https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm.

[20] World Bank (2014), World Bank Support to Higher Education in Latvia: Volume 1 - System-Level Funding, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29740/125532-v1-WP-PUBLIC-P159642World-Bank-support-to-higher-education-in-Latvia.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Notes

← 1. The Lisbon Strategy was launched in 2000 by the EU heads of state pledging that by 2010 the European Union would become "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world". Leveraging investment in R&D became a key element of this strategy following the Barcelona European Council’s objective to raise overall R&D investment to 3% of GDP by 2010 (European Council, 2000[27]).

← 2. For instance, in European Semester Country Reports, EC Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility Expert Groups, International Research Assessment Exercises, OECD Country Reviews and others.

← 4. An International Evaluation of Scientific Institutions’ Activity undertaken for the Ministry of Education and Science.

← 5. For example, the Ministry of Agriculture with respect to bio economy, the Ministry of Health with respect to biomedicine, the Ministry of Environment and Regional Development for the application of RIS3 principles in regional planning, etc.

← 6. NACE is the ‘statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community “and is the subject of legislation at the European Union level, which imposes the use of the classification uniformly within all Member States, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5902521/KS-RA-07-015-EN.PDF.