Strong governance of skills data is essential for helping policy makers and stakeholders navigate the complexity and uncertainty associated with the design and implementation of skills policies. This chapter explains the importance of skills data governance in Luxembourg and provides an overview of current practices and performance. It then explores two opportunities for strengthening skills data governance in Luxembourg: improving the quality of Luxembourg’s skills data collection; and strengthening co‑ordination of, and synergies between, skills data within and beyond Luxembourg.

OECD Skills Strategy Luxembourg

5. Strengthening the governance of skills data in Luxembourg

Abstract

The importance of strengthening the governance of skills data

Strong skills data governance is essential for helping policy makers and stakeholders navigate the complexity and uncertainty associated with the design and implementation of skills policies. Skills policies are complex as they fall at the intersection of multiple policy fields, including education, labour market, innovation, industrial and migration policy. At the same time, skills policies are developed in the context of substantial uncertainty as they are significantly impacted by megatrends, such as globalisation, automation, digitalisation, demographic change and climate change (OECD, 2019[1]), many of the implications of which are being accelerated by the COVID‑19 pandemic. In the context of uncertainty and rapid change, strong skills data governance facilitates the provision of timely and relevant information, which is necessary for ensuring that governments and stakeholders can effectively design and implement skills policies and make informed choices leading to better skills outcomes. Such evidence-based policy making can also help to strategically target investments and generate higher returns on skills investments.

In this chapter, skills data is understood as all data relevant for skills policy making, most importantly, education and training data and labour market data. Strong governance of skills data refers to: 1) collecting skills data effectively and efficiently (i.e. collecting high-quality data and coordinating within government and with non-governmental stakeholders in the data collection process, respectively); and 2) facilitating the analysis, exchange and co‑ordination of skills data (e.g. via data interoperability, data exchange platforms, etc.). Using skills data (and information on education and training opportunities) effectively and efficiently for career guidance is explored in Chapter 3.

Strong skills data governance provides the foundation for the successful design and implementation of skills policies and programmes in all of Luxembourg’s skills policy priority areas described in this Skills Strategy. Skills data are important for better aligning the adult education and training offer to fast-changing labour market needs (see Chapter 2) and informing the design and implementation of guidance and financial incentives that help steer skills choices (see Chapter 3). In addition, skills data are necessary to generate information on current and future skills needs, which is key for recruiting the right foreign talent (see Chapter 4).

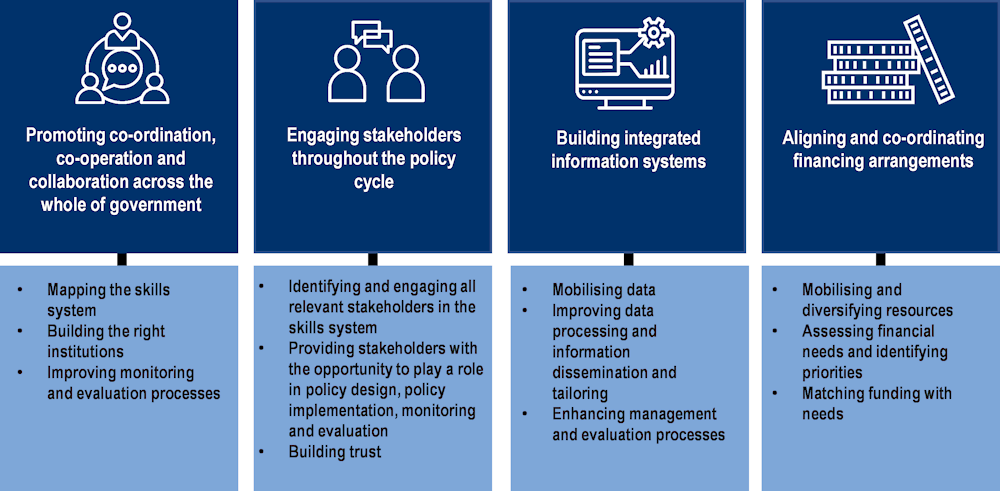

In the long run, strong skills data governance supports building integrated skills information systems (Figure 5.1),1as strong data governance helps mobilise data and enhance data management and evaluation processes. In Luxembourg, the importance of strong skills data governance is further underscored by the fact that relying solely on national skills data sources, in most cases, does not fully capture the complexity of Luxembourg’s skills system due to the high reliance on labour sourced from the Greater Region (see Chapter 4).

This chapter is structured as follows: the following section provides an overview of the current skills data governance practices in Luxembourg. The next section describes Luxembourg’s skills data governance performance. The last section conducts a detailed assessment and provides targeted policy recommendations in two opportunities for strengthening the governance of skills data in Luxembourg: improving the quality of Luxembourg’s skills data collection; and strengthening co‑ordination of, and synergies between, skills data within and beyond Luxembourg.

Figure 5.1. The four building blocks of strong skills system governance

Source: Adapted from OECD (2019[1]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264313835-en.

Overview and performance

Overview of Luxembourg’s current skills data governance practices

Collection of skills data in Luxembourg

Table 5.1. Key sources of administrative skills data in Luxembourg

|

Responsible institution |

Data type |

Description of key variables |

Frequency of updates |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Joint Social Security Centre (CCSS) |

Labour market (occupations, earnings) |

Data on occupations and workers (ISCO) at the moment of hiring, including information about the sector, occupation, contract type and duration, place of residence and earnings of residents and cross-border workers |

Rolling basis |

|

Agency for the Development of Employment (ADEM) |

Labour market (vacancies and job seekers) |

Data on vacancies by economic activity (NACE) and occupation (ROME); data on job seekers by gender, age, duration, resident status, education level, etc.; data on matching between job seekers and vacancies |

Rolling basis |

|

Sectoral institutions (e.g. ABBL, HORESCA Federation, etc.) |

Labour market (vacancies) |

Data on vacancies from sectoral institutions’ private job boards |

Rolling basis |

|

European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP) / Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER) |

Labour market (vacancies) |

Data on vacancies from private job portals by sector (NACE), occupation (ISCO), and specific skills requirements (ESCO/O*NET) |

Rolling basis |

|

Ministry of Higher Education and Research (MESR) |

Education and training (participation) |

Data on graduates (ISCED 2011 Level 5‑8) by gender, age, level of education and field of study |

Rolling basis |

|

Ministry of National Education, Children and Youth (MENJE) |

Education and training (participation) |

Data on graduates (ISCED 2011 Level 1-4) by gender, age, level of education and field of study Data on training participation of workers through the training co-financing requests of companies |

Rolling basis |

|

ADEM |

Education and training (participation) |

Data on job seeker training participation by broad training sector, level of education and duration of training |

Rolling basis |

|

Public and private education and training providers |

Education and training (participation) |

Data on participation in education and training (ISCED 2011 Level 1‑8, non-formal adult learning) by field of study/course type (among others) |

Rolling basis |

|

Training Observatory of the National Institute for the Development of Continuing Vocational Training (INFPC) |

Education and training (outcomes) |

Data on outcomes of IVET graduates by professional qualification (School – Active life transition or TEVA study) (OF, INFPC, 2019[2]) |

Every year |

|

Companies’ training practices |

Access to training and companies' training effort (OF, INFPC, 2022[3]) |

Every year |

|

|

University of Luxembourg (UoL) |

Education and training (outcomes) |

Data on outcomes (first and current employment collected through LinkedIn and graduates’ academic supervisors) of graduates (ISCED 2011 Level 7‑8) by field of study |

One-off |

Note: ABBL: Luxembourg Banker’s Association; HORESCA: National Federation of Hoteliers, Restaurateurs and Café Owners of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg; ISCO: International Standard Classification of Occupations; NACE: Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community; ROME: Operational Directory of Trades and Jobs; ESCO: European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations Classification; ISCED: International Standard Classification for Education; IVET: Initial vocational education and training.

The Joint Social Security Centre (CCSS) is Luxembourg’s key source of data for analysing the structure of its national labour market and its evolution. Employers are required to make a declaration to the Common Centre for Social Security when they wish to recruit a new employee. Data collected by CCSS include information on the employee’s occupation at the moment of hiring, sector, the type of contract and duration and the employee’s place of residence.

Luxembourg’s public employment service (ADEM) is its key data source on vacancies and job seekers. ADEM collects data on job vacancies by economic activity (NACE2) and occupation (ROME3), as well as on job seekers by gender, age, duration, resident status and education level. ADEM vacancy and job seeker data make it possible to analyse the jobs available and the occupations sought by job seekers, as well as the mismatch between the two. In addition, vacancy data are also collected by certain sectoral institutions in Luxembourg, such as the Luxembourg Banker’s Association (ABBL) (financial sector) and the HORESCA Federation, which run their own job boards. The job board of the HORESCA Federation also contains data on job seekers in the HORESCA (hospitality) sector. In addition, data on vacancies are contained on Luxembourg’s private job portals, which are web-scraped and centralised by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP)’s Skills-OVATE (online vacancy analysis tool for Europe) tool. Co‑ordination between Luxembourg and CEDEFOP is facilitated by the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER), serving as a national contact point for CEDEFOP.

Administrative data on participation in general education (ISCED 2011 Level 1‑8) are collected centrally by the Ministry of Education, Children and Youth (MENJE) and the Ministry of Higher Education and Research (MESR). These data also cover enrolment, new entrants and graduates and are reported to international institutions for the purpose of tracking data and indicators on education systems (OECD, 2021[4]). Data on adult education and training participation are collected in a decentralised manner by key public providers (e.g. the National Centre for Continuing Vocational Training [CNFPC], University of Luxembourg Competence Centre [ULCC], etc.), sectoral institutions providing training (e.g. ABBL, Chamber of Commerce [CC], Chamber of Skilled Trades and Crafts [CdM], Chamber of Employees [CSL], etc.), as well as private training providers. In addition, ADEM collects data on job seekers’ training participation.

Administrative data on education and training outcomes in Luxembourg are produced and collected, respectively, by the National Institute for the Development of Continuing Vocational Training (INFPC) and the University of Luxembourg (UoL). In addition, the Training Observatory of the INFPC regularly collects data on outcomes of initial vocational education and training (IVET) as part of the School – Active Life Transition (TEVA) annual study by linking data from MENJE, MESR and CCSS and on companies’ training practices.

At the higher education (HE) level, the UoL carried out a one-off graduate tracking exercise in 2021, which collected information on graduates’ first and current employment via LinkedIn and through graduates’ academic supervisors.

Luxembourg’s collection of administrative skills data (Table 5.1) is further complemented by skills data collected through surveys (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2. Key skills-related surveys in Luxembourg

|

Source |

Name |

Description of key variables |

Frequency of updates |

|---|---|---|---|

|

National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (STATEC) |

Labour Force Survey (STATEC (2022[5])) |

Employment status; occupation code (ISCO 4‑digit); education level; formal and non-formal education and training participation (except guided on-the-job training) of resident workers only in the last four weeks |

Every year |

|

Adult Education Survey (STATEC, (2022[6])) |

Formal and non-formal education and training and informal learning participation in the last 12 months; time spent on education and training; obstacles to participation, guidance and financial support |

Every 4‑5 years |

|

|

Firms' provision of continuing vocational training (job training, planned training, job rotation or training by exchanges with other services, study visits, self-directed learning, attendance at conferences, workshops, fairs and lectures), firms’ payments for training, etc. |

Every 5 years |

||

|

Structure of Earnings Survey (STATEC, (2022[8])) |

Occupation codes (ISCO 3-digit) of workers (including cross-border workers), including earnings |

Every 4 years |

|

|

Training Observatory of the National Institute for the Development of Continuing Vocational Training (INFPC) |

Training Offer (Observatoire de la formation and INFPC, (2021[9])) |

Adult learning offer and practices of adult learning providers |

Every 3 years |

|

Continuing Vocational Education and Training (CVET) studies |

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of CVET accessibility and participation of employees |

Ad hoc |

|

|

University of Luxembourg (UoL) |

Graduate Outcomes Survey |

Outcomes (self-reported employment status, earnings, perceived mismatch, use of skills on the job) of tertiary graduates by field of study, date of conclusion of studies, etc. |

Every year |

|

Luxembourg Banker’s Association (ABBL) |

Not specified |

Difficulties and duration of recruitment by job type in the financial sector |

One-off survey in 2018 |

|

Business Federation Luxembourg (FEDIL) |

Qualifications of tomorrow – in Industry (FEDIL, (2021[10])) / in ICT (FEDIL, (2018[11])) |

Future workforce and qualification needs in the manufacturing and ICT sector |

Every 2 years |

|

Competence Centres of the Building Services Engineering and Completion Engineering (CdC-GTB/PAR) |

Not specified |

Skills and training needs by level of education and by job type among employers in the construction sector |

Twice a year |

|

Chamber of Commerce (CC) |

Barometer of the Economy “Thematic Focus: Recruitment” (CC, (2019[12])) |

Skills shortages (occupational) and recruitment difficulties of firms across sectors |

One-off (2019) |

|

Barometer of the Economy “Thematic Focus: Skills and training (CC, (2021[13])) |

Provision of firm-based training across sectors |

One-off (2021) |

|

|

Chamber of Skilled Trades and Crafts (CdM) |

Survey on Firms in the Crafts Sector |

Future workforce needs and expected skills gaps of firms in the crafts sector |

One-off to date (2019) with a new version currently ongoing in 2022 |

|

Chamber of Employees (CSL) |

Quality of Work Index (CSL, (2021[14])) |

Quality of work and questions on participation in adult learning |

Every year |

The National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (STATEC) is in charge of administering Luxembourg’s household surveys relevant for the analysis of skills policies. The European Union Labour Force Survey (LFS), implemented in Luxembourg, collects, among others, information on respondents' (residents only) employment status (employed/unemployed/inactive), occupation (ISCO code), as well as participation in formal and non-formal education (except for guided on-the-job training) in the last four weeks. With the European Union (EU) Adult Education Survey (AES) implemented in Luxembourg, STATEC collects, among others, information on public participation in formal and non-formal education and training and informal learning in the last 12 months. Information on obstacles to training participation and time spent on education and training is also available via AES. STATEC is equally in charge of carrying out the Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS), which measures enterprises' activity in the provision of continuing vocational education and training (CVET), and the Structure of Earnings Survey (SES), which collects data on earnings of all firms with at least ten employees in all sectors by economic activity (NACE) and occupation (ISCO). Similarly to LFS and AES, both CVTS and SES are EU surveys, which STATEC implements in Luxembourg.

The Training Observatory of the INFPC collects data on the learning offer of adult learning providers through a regular survey and launched another survey in 2021 on the provision of CVET in small companies. In addition, the UoL conducts an annual survey of its graduates, collecting self-reported data on graduates’ education and training outcomes (e.g. employment status, earnings, perceived mismatch, use of skills on the job, etc.).

In addition to surveys administered by governmental actors, non-governmental and sectoral actors in Luxembourg actively collect data on workforce needs, recruitment challenges and firm-based training provision for some of the sectors of Luxembourg’s economy through their own surveys.

The ABBL conducted a one-off survey with member companies on the difficulties and duration of recruitment in the financial sector in 2018. The Competence Centre of the Building Services Engineering and Completion Engineering (GTB/PAR), which provides training to craft companies, conducts a survey twice a year to enquire about the skills/training needs among employers in the construction sector. The survey collects information on skills and training needs by level of education and by job type. In addition, the Business Federation Luxembourg (FEDIL) conducts a survey every two years on the manufacturing and information and communication technology (ICT) sectors’ future qualification needs.

The CC, in collaboration with the Luxembourg Institute for Social Research (Institut Luxembourgeois de Recherches Sociales, ILRES), a private survey company, carries out its annual Barometer of the Economy study that collects information on the key concerns among Luxembourgish employers. Each Barometer of the Economy has a different thematic edition. In 2019 and 2021, the thematic editions enquired about employers’ recruitment difficulties, and firm-based training provision, respectively. In addition, the CdM conducted a survey in 2019 on skilled labour needs and shortages in the crafts sector, supplemented by a qualitative analysis based on interviews with company managers from the various groups of craft activities. The survey was repeated in 2022.

Since 2013, the CSL, in collaboration with the UoL, has conducted the Quality of Work Index survey on an annual basis with questions on employees’ working conditions and the quality of work in Luxembourg. Topics cover work demands and workloads, working hours, co‑operation between colleagues, possibilities for further training and advancement, participation in decision making in businesses, and more.

Analysis, exchange and co‑ordination of skills data in Luxembourg

Several key institutions in Luxembourg engage in the analysis, exchange or co‑ordination of the collected skills data (as mentioned above). These institutions include ADEM, the General Inspectorate of Social Security (IGSS), INFPC, STATEC and the Labour Market and Employment Research Network (Réseau d’études sur le marché du travail et de l’emploi, RETEL). In addition, the “Trends” working group, established between ADEM and the Union of Luxembourg Companies (UEL), helps increase the transparency of existing skills data and to further consolidate and improve them.

ADEM publishes labour market analyses regularly, including analyses of vacancies reported to, and job seekers registered with, ADEM (ADEM, 2022[15]). In 2022, ADEM also elaborated sectoral studies, which analyse labour market trends across seven sectors in Luxembourg. Based on ADEM vacancy data, the sectoral studies were developed in collaboration with employers to provide information about Luxembourg’s growing, declining and emerging occupations, as well as labour shortages and surpluses, among others (ADEM, 2022[16]).

IGSS engages in the analysis and publication of labour market data. On a regular basis, IGSS publishes data on labour market trends in Luxembourg (including net employment creation trends by sector, age, gender, nationality, and place of residence, among others) (IGSS, 2022[17]). Every month, IGSS also publishes a snapshot of Luxembourg’s labour market situation (including the size of the labour force and labour force growth comparison with the preceding year, among others) (IGSS, 2022[18]).

INFPC’s Training Observatory conducts research in the field of education and training to support policy makers, employers and education and training providers in improving education and training policies and practices. The Training Observatory analyses employees' access to employer-sponsored training, firms' training activities and the state's financial contribution to firms' training plans, among others. The Training Observatory is a member of ReferNet, the European network of reference and expertise on vocational education and training (INFPC, 2021[19]).

STATEC carries out and publishes relevant analyses often (but not only) on the basis of the surveys it administers (see Table 5.2). For example, relevant publications have presented the results from the AES (STATEC, 2018[20]) and the CVTS (STATEC, 2018[21]) for Luxembourg.

Data exchange and collaboration between IGSS, ADEM and STATEC are supported via RETEL. RETEL was established to commission new, and centralise existing, labour market research in Luxembourg. RETEL aims to support the development of synergies between the work of various governmental entities and stakeholders engaged in Luxembourg’s primary labour market data collection and the analysis of labour market data. Through its work, RETEL seeks to foster an efficient and transparent approach to data-driven production of labour market information and evaluation of labour market policies in Luxembourg (Government of Luxembourg, 2018[22]).

MESR launched an initiative to set up a National Data Exchange Platform (NDEP) in Luxembourg to facilitate smoother data exchanges, covering data in various fields beyond skills. The NDEP project is developed in co‑operation with various other governmental institutions in Luxembourg (see more in Opportunity 2).

Finally, to increase the transparency of the existing skills data (as summarised in Table 5.1 and Table 5.2) and further consolidate and improve them, Luxembourg established the Trends working group within the framework of the long-term collaborative effort between ADEM and UEL (ADEM/UEL, 2021[23]). Apart from ADEM, the Trends working group includes various members of the UEL, including representatives of the ABBL, CC, CdM, Luxembourg Trade Confederation (CLC), Federation of Artisans (FDA), FEDIL, Competence Centre for Building Services Engineering (GTB) and the HORESCA Federation (ADEM/UEL, 2021[23]).

Luxembourg’s skills data governance performance

As foreshadowed at the beginning of this chapter, strong skills data governance requires that skills data collection processes are effective and efficient (i.e. skills data collection is well-coordinated, resulting in the generation of high-quality data) and that skills data exchanges are easily facilitated.

Skills data governance in Luxembourg could be strengthened on several fronts. First, there is room to improve the quality of Luxembourg’s skills data collection in terms of accuracy (i.e. the degree to which the data correctly estimate or describe the quantities or characteristics they are designed to measure) (OECD, 2011[24]), coverage (i.e. completeness of the data) and granularity (i.e. level of detail) (OECD, 2014[25]), as well as to expand the range of skills data collected.

Moreover, there is space to better facilitate skills data co‑ordination and exchanges both within the government and with relevant stakeholders in Luxembourg. With the labour market extending beyond national borders, Luxembourg could equally benefit from building stronger synergies with international data sources, especially to better understand the changing skills supply and demand in the Greater Region (see Chapters 1 and 4 for a discussion of the strategic importance of the Greater Region for Luxembourg).

The cross-border nature of Luxembourg’s labour market further complicates skills data governance processes. As almost half of Luxembourg’s labour force is constituted by cross-border workers (see Chapter 4), Luxembourg does not participate in the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, PIAAC). As a result, Luxembourg cannot benefit from the survey’s assessment of the literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills possessed by adults or how adults use their skills at home, at work and in the wider community. Similarly, other international surveys that Luxembourg takes part in (e.g. the EU LFS, AES, etc.), which, among others, provide information on the occupational distribution of Luxembourg’s workforce or participation in adult education and training, cover residents only. It is possible to include cross-border workers in the analysis of Luxembourg’s occupational distribution after combining variables in the LFS, but only with certain caveats (e.g. limited disaggregation is possible). A similar exercise is not possible in the context of the AES.

Existing skills data governance challenges affect Luxembourg’s skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) exercises.4 For example, given that ADEM’s sectoral studies (see above) were based solely on ADEM vacancy data, which themselves face important coverage challenges (due to the incomplete declaration of job vacancies by employers; see more in Opportunity 1), the results of the sectoral studies have to be interpreted with caveats, bearing in mind the limitations of the data sources used.

In addition, Luxembourg’s SAA exercises tend to be restricted to identifying current skills needs (e.g. by analysing skills demanded in job vacancies) and changing labour market conditions (e.g. growth or decline of certain occupations). However, little is done to anticipate Luxembourg’s future skills needs. Stakeholders have indicated that, to a large extent, the absence of skills anticipation exercises is linked to the quality and co‑ordination challenges of Luxembourg's existing skills data sources.

It is welcome that the recently established Trends working group led by ADEM and UEL (see above) has recognised many of the skills data challenges highlighted above and intends to work collaboratively on solving them. In addition, LISER has similarly made improving the “data infrastructure and, in particular, access to high-quality data in and for Luxembourg” one of its core objectives (LISER, 2020[26]).

Opportunities for strengthening the governance of skills data in Luxembourg

The performance of Luxembourg’s skills data governance arrangements reflects many factors. These include individual and institutional factors and broader socio-economic factors (i.e. Luxembourg’s heavy reliance on cross-border labour). However, two key opportunities for improvement have been identified based on a literature review, desk analysis and data, and input from officials and stakeholders consulted in conducting this OECD Skills Strategy.

The OECD considers that Luxembourg’s main opportunities for improvement in the area of skills data governance are:

1. improving the quality of Luxembourg’s skills data collection

2. strengthening co‑ordination of, and synergies between, skills data within and beyond Luxembourg.

Opportunity 1: Improving the quality of Luxembourg’s skills data collection

As foreshadowed earlier in this chapter, Luxembourg collects a wide variety of quantitative and qualitative data, which can be used to inform the design of skills policies, including labour market data and education and training data. These data sources, and their combination, can provide different types of insights essential for skills policy making.

Labour market data (e.g. social security data, vacancy data, etc.) are commonly used as proxies for the analysis of evolving skills needs because they allow for the observation of growth or decline in employment in specific occupations (OECD, 2016[27]). Vacancy data collected by public employment services (PES) can also provide valuable information on skills needs and shortages by facilitating the analysis of the changes in the number of declared and (un)filled vacancies and the duration of vacancy filling, among others (McGrath and Behan, 2017[28]). In addition, insights from employer surveys can be used to complement administrative data to assess skills needs and shortages by providing information not available in administrative datasets.

Education and training data (e.g. on attainment, participation, outcomes, expenditure, curricula, etc.) provide important information on the access, quality and relevance of the supply of education and training opportunities. This information helps policy makers identify challenges and opportunities in the skills system and target programmes and funding where the expected impacts will be highest.

To improve its quality, Luxembourg’s skills data collection could benefit from:

improving the accuracy, coverage and granularity of Luxembourg’s labour market data

expanding the range and strengthening the granularity of Luxembourg’s education and training data.

Improving the accuracy, coverage and granularity of Luxembourg’s labour market data

As shown in Table 5.1 and Table 5.2, Luxembourg collects a wealth of labour market data, which provides valuable information on the evolving skills needs in Luxembourg’s economy. However, to allow data users (both in and outside of the government) to unlock the full potential of Luxembourg’s labour market data, Luxembourg should work on addressing the accuracy, coverage and granularity challenges of certain labour market data sources.

Luxembourg’s social security data, collected by the CCSS, are Luxembourg’s only source of occupational data covering both Luxembourgish residents and cross-border workers. Given that cross-border workers account for 46% of Luxembourg’s labour market (see Chapter 4), the importance of CCSS data cannot be overstated. CCSS data can inform the assessment of the occupational distribution in Luxembourg’s labour market and serve as a proxy for assessing current skills needs by making it possible to observe growth or decline in specific occupations. Should Luxembourg consider developing exercises for anticipating future skills needs (as supported by stakeholders consulted in the context of this project), such as Canada’s Occupational Projection System (COPS) (Government of Canada, 2017[29]) or the United Kingdom’s Working Futures projections (Warwick Institute for Employment Research, n.d.[30]), CCSS data would be valuable for producing occupational projections (i.e. projections showing the expected future number of workers to be employed in different occupations, thereby producing insights about the future occupational growth or decline).

However, CCSS occupational data face important accuracy challenges due to incorrectly declared occupational codes by employers or their service providers (e.g. payroll managers or outsourced accounting firms). As mentioned above, each newly hired employee has to be reported to the CCSS (Government of Luxembourg, 2021[31]). When making the declaration to CCSS, the occupation of the new employee needs to be specified via a code defined in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). However, there is evidence suggesting that in many cases, companies’ payroll managers or accounting firms to whom payroll management can be outsourced input incorrect ISCO codes in the employment declarations (ADEM/UEL, 2021[23]), making CCSS data unusable for the analysis of Luxembourg’s labour market at the occupational level.

During a data check carried out in 2016, the IGSS found that the ISCO codes were entered correctly in about only 30% of cases. More specifically, IGSS found that a large share of occupations belonging to ISCO groups 1‑3 (managers, professionals, and technicians and associate professionals, respectively) were reported under ISCO group 4 (clerical support workers). In part, the reason for inputting incorrect ISCO codes stems from the French translation of the ISCO classification, where the name of ISCO group 4 is translated as “administrative employees” (employés administratifs), which does not fully reflect the meaning of the original English name “clerical support workers”.

In order to support employers and their service providers in declaring the correct ISCO codes, IGSS published an online guide in French, where the distinction between the ISCO groups was clearly delineated. IGSS also sent out a letter to employers to highlight the existence of the problem, underscoring the importance of correctly declaring the ISCO codes. Moreover, CCSS developed an occupational code search engine on its website, accessible in French, aiming to help identify the correct ISCO codes more easily. However, it was discussed in stakeholder consultations that in a recent data check, IGSS found that these communication efforts did not yet have the desired effect, as the share of ISCO codes declared correctly had not improved.

Occupational data (declared via ISCO codes) is used for purely analytical purposes in Luxembourg, which means that employers do not have a strong incentive to ensure that the declared ISCO codes are correct. Going forward, Luxembourg could incentivise employers to declare correct occupational codes by designing practical tools, which would have clear value-added for employers without increasing employers’ administrative burden. For example, based on the CCSS data, CCSS and IGSS could design an online occupations dashboard, where employers would log in and track the occupational structure and evolution within their company, together with additional features (e.g. employee salary distribution, age profiles, etc.). Such a dashboard could bring significant benefits, especially to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which tend to have constrained administrative capacity for human resources (HR) management. Furthermore, to increase the value-added of the dashboard, employers in Luxembourg could be, in the long term, asked to regularly update the declared ISCO codes, given that the codes are currently not being updated at all.

To further facilitate ISCO code declarations, CCSS could improve the search functions of the existing occupational code search engine. For example, the occupational coding tool developed by the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom features probability scores reflecting the perceived match between the keywords input into the tool and the suggested occupational codes, as well as descriptions of tasks of the occupations suggested to match one’s search, entry routes, associated qualifications and related (similar) job titles (Box 5.1). To support the user-friendliness of the occupational coding tool, CCSS could develop a chatbot allowing real-time responses to queries of employers or their service providers who might be unsure of which occupational code to declare. CCSS could also consider making the search engine accessible in English in addition to French, given the challenges related to correctly translating the ISCO codes from English to French highlighted above. In the long run, making the search engine accessible in German and Luxembourgish could also be considered, given the variety of languages used in Luxembourg and its labour market (see Chapter 4).

Box 5.1. Relevant international example: Occupational coding tool

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom (UK), the Warwick Institute for Employment Research at the University of Warwick developed the Computer Assisted Structured Coding Tool (“Cascot”) capable of occupational coding and industrial coding to the UK standards developed by the UK Office for National Statistics. The standards are the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC).

Cascot assigns a code to a piece of text and calculates the degree of certainty (denoted by a score from 1 to 100) of the assigned score being correct. When Cascot encounters text that does not allow it to clearly match it with any specific occupation or industry, it will attempt to suggest a code but will limit the assigned score to below 40 to signal the uncertainty associated with the suggestion made.

Cascot also features descriptions of tasks of the occupations suggested to match one’s search, entry routes, associated qualifications and related (similar) job titles. A multilingual version of Cascot (Cascot International) is available in 15 languages, including French and German. Cascot International facilitates occupational coding to the ISCO 08 classification and a relevant national occupational classification, where available.

Cascot has been evaluated by comparing the tool’s suggestions with a selection of manually coded data of high quality. The results showed that 80% of records received a score greater than 40, and of these, 80% were matched to manually coded data. The performance of Cascot is dependent on the quality of input data.

Source: Warwick Institute for Employment Research (2018[32]), Cascot: Computer Assisted Structured Coding Tool, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/software/cascot/details/; Warwick Institute for Employment Research (2018[33]), Cascot International, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/software/cascot/internat/.

While the existing awareness-raising activities mentioned above (i.e. developing an online guide, sending a letter to employers) undertaken by CCSS/IGSS are steps in the right direction, they could be further strengthened. Information on common mistakes in inputting ISCO codes, as well as an overview of the existing resources and tools for helping employers select the correct ISCO code (e.g. the proposed occupations dashboard, CCSS’ occupational code search engine, IGSS’ online guide, etc.) could be regularly distributed to employers and the existing guidance tools more prominently featured on IGSS/CCSS websites. CCSS/IGSS could expand their awareness-raising activities to include associations of human resources (HR) professionals (e.g. POG – HR Community of Luxembourg) and associations of payroll experts (e.g. Luxembourgish Association of Accounting and Tax Consultancies, ALCOMFI) to target actors directly in charge of employment entry declarations. Employer representatives (e.g. UEL) should equally play a key role, and promote the importance of, and existing support tools for, correctly declaring new hires to the CCSS among employers. In addition to undertaking efforts to strengthen the accuracy of CCSS data, IGSS and other stakeholders in Luxembourg should still make use of the data to the extent possible (e.g. for the analysis of general growth trends across occupations).

Beyond addressing accuracy issues with social security occupational data, there is space to improve the coverage and granularity of Luxembourg’s vacancy data. In Luxembourg, a legal obligation exists for employers to declare all job vacancies to ADEM. Employers can report vacancies online via guichet.lu (Luxembourg’s e-government platform) or by filling out a PDF form which needs to be sent to ADEM via email or post. A vacancy declaration can be completed in English, French or German (ADEM, 2021[34]). Despite these efforts, a comparison of the number of vacancies declared to ADEM to the number of actual recruitments (based on employment entry declarations to the CCSS) shows that the vacancies reported to ADEM cover less than 30% of all actual job creations in Luxembourg’s labour market (ADEM, 2021[35]). The number of declared vacancies also varies by sector. For example, while the estimated average share of job vacancies reported to ADEM was approximately 35% in the ICT sector between January 2020 and January 2021, the figure stood at 18% in the construction sector (ADEM, 2021[35]). While a certain degree of caution should be used when interpreting the results of the comparison of vacancy and recruitment data, since not every recruitment is preceded by a job posting, it can still provide a rough estimate of the coverage of the vacancy data. Given the relatively low number of vacancies reported to ADEM, it can be challenging to use ADEM vacancy data to reliably assess Luxembourg’s labour market needs and shortages.

Stakeholders have mentioned several potential reasons for the relatively low number of vacancies reported to ADEM. For example, employers, and especially SMEs, without a dedicated HR department might struggle to find the time and resources to report job vacancies. Stakeholders have also suggested that certain employers do not see great value in reporting vacancies to ADEM since the pool of candidates (registered job seekers) is often unlikely to match the exact requirements of the declared vacancy. Moreover, some recruitments are based on informal referrals rather than officially created and published job postings.

It should be noted that ADEM has taken a number of concrete steps to incentivise employers to improve job vacancy reporting rates. Penalties for enforcing the mandatory vacancy reporting obligation are not applied, and ADEM prefers to use positive incentives instead (Goffin, 2015[36]). For example, ADEM has simplified the vacancy reporting forms (Goffin, 2015[36]) and has been running awareness-raising campaigns for employers within the framework of the ADEM/UEL partnership, underscoring the fact that vacancy reporting is as important for analytical as for recruitment purposes. ADEM also sends its employer service staff to visit companies and highlight the added value of regular vacancy reporting (Goffin, 2015[36]). Moreover, ADEM has started offering the possibility to automatically import a vacancy from a company's job database to ADEM, which several large employers have already implemented. In addition, ADEM has begun creating partnerships with certain private local job portals to automatically import their online job advertisements (OJAs) into ADEM's job board. Finally, ADEM has been developing a range of new services, so it is more attractive for employers to approach ADEM. For example, in April 2021, ADEM’s job board was for the first time opened to job seekers who are not registered with ADEM (ADEM, 2021[37]). The results of such efforts are yet to be seen.

Data from OJAs, as already partly explored by ADEM, could serve as a useful additional source of vacancy data for Luxembourg, as OJA data capture even those vacancies not declared to ADEM, but that appear on private job portals. CEDEFOP’s Skills-OVATE tool uses web-scraping techniques to collect OJAs from private job portals, public employment service portals, recruitment agencies, online newspapers and corporate websites (CEDEFOP, 2021[38]). In addition, Skills-OVATE provides a granular view of skills most sought after by employers in their vacancies, classified according to the European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO) classification (see more below). While Skills-OVATE data for Luxembourg cover online private job boards, it does not include ADEM’s vacancy data. This is because Skills-OVATE only sources information from publicly accessible job boards, and ADEM’s job board was not public when the Skills-OVATE tool was designed. Since then, however, ADEM has agreed to publish its vacancies (with employers’ permission) on the publicly accessible European Employment Services (EURES) job board, with the view of supporting EU job mobility. Therefore, a large share of ADEM’s vacancies is now accessible on the EURES public job board and can be scraped by Skills-OVATE.

LISER, the national contact point for CEDEFOP, should thus consider reopening conversations with ADEM about including their vacancy data in the Skills-OVATE tool. This would allow for more comprehensive information on both occupational and skills needs trends in Luxembourg by having access to data from vacancies declared both to ADEM and at Luxembourg’s private job portals. As Skills-OVATE is updated four times a year, skills needs information could be obtained regularly. Partnering with CEDEFOP would equally help ensure that the data does not contain duplicate vacancies (i.e. vacancies declared both to ADEM and on private job boards) using the tools CEDEFOP had developed. Making greater use of OJA data could help improve both the coverage and granularity of Luxembourg’s vacancy data. Nonetheless, ADEM should still strive to increase the share of job postings created and declared by employers. As noted above, since not every recruitment is preceded by a job posting, even greater use of OJA data might not provide a comprehensive picture of Luxembourg’s labour market needs.

Going forward, ADEM could consider further expanding the range of support tools and services for employers to strengthen the incentives for employers to approach ADEM to declare job postings. For example, ADEM could develop an online vacancy dashboard for employers, similar to the occupations dashboard (see above), based on vacancy data reported to ADEM. Upon logging in, the vacancy dashboard could give the employer an overview of the vacancies (open and filled) over time within the company and how quickly different vacancies are being filled. In the future, consideration could be given to further developing the technical functions of the vacancy dashboard, for example, to calculate the “attractiveness scores” (i.e. probabilities of finding a suitable candidate for each vacancy based on ADEM’s job seekers database) of each vacancy. Stakeholders consulted in the context of this project agreed that employers, especially SMEs, would benefit from such an online vacancy dashboard. In addition, CCSS and ADEM could work on creating links between CCSS employment entry declarations and ADEM vacancy declarations (see more on ADEM vacancy declarations below) to make the reporting process more straightforward for employers. For example, a vacancy reported by an employer to ADEM could be assigned a unique identifier, which, once a suitable candidate has been found for the advertised job posting, could be used to pre-fill the CCSS employment entry declaration.

Evidence shows that the capacities of small employers to engage in formal recruitment, and thereby vacancy reporting, tend to be restricted the most owing to resource constraints or organisational culture (European Commission, 2018[39]). Therefore, to incentivise SMEs to approach ADEM and encourage higher vacancy reporting rates, ADEM could consider developing dedicated support services for SMEs. For example, ADEM could provide support to SMEs in drafting job postings according to their needs, on top of providing additional services (e.g. sign-posting the available reskilling/upskilling opportunities for SME employees). Box 5.2 details the recruitment and support services provided to SMEs in Germany by way of example.

Box 5.2. Relevant international example: Recruitment and support services for SMEs

Germany

In Germany, the public employment service (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) helps SMEs set up vacancies and recruit new personnel. Additionally, SMEs can receive financial support for new recruits who do not yet meet the competence standards for their work. The Bundesagentur also publishes “Faktor A”, a magazine and podcast targeted at SMEs with articles focused on recruitment and training, leadership development, as well as the future of work.

The parent organisation of the Bundesagentur, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales), provides the “Leveraging the human factor programme” (unternehemensWert: Mensch, uWM), a consulting service funded via the European Social Fund that supports SMEs in developing long-term human resource strategies. uWM’s consulting services focus on personnel management, skills development, equal opportunities and diversity. Government grants cover up to 80% of the consulting costs for companies with fewer than 10 employees, while companies with 10‑249 employees can receive grants for up to 50% of their costs.

In Berlin, the Organisation for Education and Participation (Gesellschaft für Bildung und Teilhabe mbH or GesBiT) and the Senate Department for Integration, Labour and Social Affairs (Senatsverwaltung für Integration, Arbeit und Soziales) maintain an Office for Qualification Consulting for SMEs. The consulting services offer SMEs advice on assessing companies’ skills needs, available reskilling/upskilling opportunities, as well as recruitment and funding opportunities of which they may be unaware.

Source: Investitionsbank Berlin (2021[40]), 2021/2022 Business Support Guide, www.businesslocationcenter.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Wirtschaftsstandort/files/foerderfibel-en.pdf; OECD (2020[41]), Preparing the Basque Country, Spain for the Future of Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/86616269-en.

Employer representatives in Luxembourg should equally play a role in encouraging higher vacancy reporting rates via active awareness-raising. Members of the UEL (including associations, federations and confederations and chambers of commerce) could raise awareness about the importance of vacancy reporting in their engagement activities with employers (e.g. information sessions, newsletters, prominent featuring on their respective websites, etc.).

In order to further improve the assessment of skills needs, Luxembourg’s vacancy data could be further enriched by insights on skills and workforce needs collected by directly surveying employers. As outlined above, several surveys of employers’ current and future workforce needs have been carried out by several non-governmental stakeholders (e.g. ABBL, CC, CdM, FEDIL, etc.) in Luxembourg in recent years. CdM and FEDIL implement employer surveys regularly. However, due to the varying structure of questions, sector coverage, frequency of implementation and definition of skills/workforce needs, each survey provides only a piece-meal picture of employers’ skills needs. In addition, stakeholders for this review mentioned that too many surveys risk creating “survey fatigue” among employers in Luxembourg, given the size of the country and the administrative and time burden associated with completing each survey.

Going forward, Luxembourg should review the existing employer surveys, in tandem with administrative data on skills needs (e.g. ADEM and Skills-OVATE vacancy data; see Recommendation 4.2) to identify information that: 1) would add value to Luxembourg’s labour market data collection but is currently not available in administrative datasets; and 2) is collected by existing employer surveys irregularly, inconsistently or not at all. For example, while Luxembourg’s administrative datasets currently do not hold information on future skills needs, CdM and FEDIL surveys collect such insights but only cover three sectors (crafts, industry and ICT). The review of administrative data and existing employer surveys would help Luxembourg assess the need to introduce a national, cross-sectoral employer survey of skills needs and/or gaps. Such a national survey should reduce the need for multiple employer surveys in the long run and mitigate against the risk of “survey fatigue” in Luxembourg. Box 5.3 describes how the United Kingdom implements a nationwide Employer Skills Survey. In developing such a national employer survey, Luxembourg could follow CEDEFOP’s (2013[42]) “User guide to developing an employer survey on skill needs”, where relevant.

Box 5.3. Relevant international example: Nationwide employer survey

United Kingdom

Since 2011, the United Kingdom has carried out large-scale, cross-sectoral surveys of employers’ skills needs. The United Kingdom’s employer survey is one of the largest employer surveys in the world. The survey is essential for the work of the Department for Education in England (UK) and its partners within national and local government.

The latest completed iteration of the survey was carried out in 2019 via telephone interviews and asked employers questions about: 1) recruitment difficulties and skills lacking from applicants; 2) skills lacking from existing employees; 3) underutilisation of employees’ skills; 4) anticipated needs for skill development in the next 12 months; 5) the nature and scale of training, including employers’ monetary investment; and 6) the relationship between working practices, business strategy, skill development and skill demand.

Across different sectors, the survey enquired about employers’ skills needs at the level of occupations as well as specific skills (e.g. management, leadership, digital, people or specialist job-related skills).

The success of the survey depends on the willingness of employers to participate. More than 81 000 randomly selected employers across England, Northern Ireland and Wales took part in the survey in 2019. The underlying datasets are available through the UK Data Service by special licence access.

The next iteration of the survey, to be published in 2023, was commissioned to three market research agencies by the Department for Education (DFE) in England, the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive, and covers England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Again, the survey will be conducted via telephone interviews. If selected, employers can choose the time of their interview. Each employer participating in the survey will be asked if they would like to receive a summary report with the survey findings once the survey has been completed.

The survey results will be published on the gov.uk website in 2023.

Source: Government of the United Kingdom (2020[43]), Employer Skills Survey 2019, www.gov.uk/government/collections/employer-skills-survey-2019; Department for Education (2022[44]), Employer Skills Survey 2022, www.skillssurvey.co.uk/index.htm.

Finally, to further improve the granularity of Luxembourg’s labour market data collection, Luxembourg could benefit from tools that make it possible to link the information on occupations in vacancies declared by employers to specific skills. In the future, ADEM plans to move towards skills-based matching, where job seekers would be matched with occupations best suited to their skills, which could facilitate a closer match. However, ADEM’s current job-matching system does not yet facilitate skills-based matching. At present, ADEM matches job seekers to vacancies by matching the occupation (ROME) code associated with a specific vacancy, with the occupation (ROME) code indicated to be of interest by a job seeker, as well as according to language or education requirements, among other criteria.

Several OECD countries make it possible to link occupations and skills by using skills-based occupational classifications. For example, O*NET in the United States is a database containing detailed information about the knowledge requirements of more than 800 occupations. In Canada, the National Occupational Classification describes the world of work and occupations, including the skills required by each of the 500 occupational unit groups (OECD, 2016[27]). In 2021, Australia launched its own comprehensive skills classification, identifying around 600 skills profiles for occupations in the Australian labour market based on the O*NET database (National Skills Commission, 2021[45]). In 2017, the European Commission introduced the ESCO classification, which links occupations and skills relevant for the EU labour market and education and training (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Relevant international example: Skills-based occupational classification

The European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations classification (ESCO)

The European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations classification (ESCO) is the European multilingual classification of skills, competences and occupations.

ESCO offers a “common language” on occupations and skills that can be used by a wide variety of stakeholders to help connect people with jobs, employers and education and training providers and promote job mobility across Europe.

ESCO works as a dictionary, describing, identifying, and classifying professional occupations and skills relevant for the EU labour market and education and training. As of 2022, ESCO provided descriptions of 3 008 occupations and 13 890 skills associated with these occupations, translated into all official EU languages, as well as Icelandic, Norwegian, Arabic and Ukrainian.

For each occupation, ESCO defines an occupational profile, listing (among others) the skills considered relevant for this occupation. With respect to skills, ESCO distinguishes between skills, competences and knowledge. Skills refer to the “ability to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems”; competences are understood as the “proven ability to use knowledge, skills and personal, social and/or methodological abilities, in work or study situations and in professional and personal development”; and knowledge is defined as “body of facts, principles, theories and practices that is related to a field of work or study”. For example, working as a civil airline pilot requires the competence to combine knowledge on emergency procedures and equipment malfunctions with skills on reading position coordinates and following the air route.

ESCO is free and available as linked open data.

Source: European Commission (2022[46]), What is ESCO, https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en/about-esco/what-esco; European Commission (2022[47]), ESCOpedia, https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en/about-esco/escopedia/escopedia.

In Luxembourg, no common, comprehensive skills classification is currently used. Links between occupations and specific skills in Luxembourg's labour market have been defined only for occupations in certain sectors and a non-coordinated manner. In some sectors, the content of occupations is described in collective agreements. For example, the collective agreement covering the banking sector describes the tasks, knowledge and technical skills, among others, required for occupations (ABBL, ALEBA, OGBL and LCBG-SEFS, 2018[48]). In addition, some sectors, such as crafts (CdM, n.d.[49]), have developed more detailed skills profiles for their occupations based on research carried out in working groups or through labour market monitoring (ADEM/UEL, 2021[23]). The limitation of the skills classifications developed at the sectoral level is that they are not linked to a recognised national or international occupational classification (e.g. ISCO), which confines their potential use to the internal needs of the sector. Moreover, the definition of “skills” used by the different classifications varies between sectors, while most sectors in Luxembourg have not developed skills classifications at all (ADEM/UEL, 2021[23]).

Stakeholders in Luxembourg have agreed that rather than developing its own common skills classification, ADEM should consider leveraging and adapting existing and internationally interoperable skills classification for classifying its own vacancy data. The ESCO classification (Box 5.4), designed to reflect the specificities of the EU labour market, might be particularly well-suited to Luxembourg's needs. The ESCO skills classification permits establishing direct links with occupational information classified according to the ISCO classification or indirect links with classifications that map onto ISCO (such as ROME), which are used in many EU member states (European Commission, 2021[50]), including Luxembourg.

ADEM would not be the first public employment service to adopt ESCO. In 2018, Iceland became the first country to adopt ESCO on a national level when the public employment service started using ESCO to revamp its job board (Box 5.5). To facilitate skills-based matching, ESCO is now being used by PES in seven countries (Albania, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel and Malaysia) (European Commission, n.d.[51]). Most recently, ESCO has been adopted by Greece (Box 5.5). Beyond adopting ESCO at ADEM to support skills-based matching, ESCO could be equally used to help systematically define learning outcomes of adult learning courses, which would have important benefits for Luxembourg’s education and training data collection (see the section below on education and training data; also see Recommendation 1.3 in Chapter 2).

Box 5.5. Relevant international example: Adopting the ESCO classification by a public employment service

Iceland

Iceland became one of the first countries to introduce the ESCO classification at a national level.

In 2018, ESCO started being used by the public employment service to revamp job platforms in the country, hitherto relying on the ISCO‑88 classification for job matching.

Using the ESCO classification has helped Iceland to more effectively link employers with the right job applicants. As a result, employers are able to better communicate their needs and job seekers better able to see what exactly employers are looking for in applicants.

The use of ESCO also facilitates that job vacancies are described more accurately, thanks to the provision of multilingual information on the knowledge, skills and competences required for the job. The multilingual feature of ESCO has been particularly useful for Iceland, given that more than 10% of Iceland’s labour force is foreign-born.

Greece

The Greek Public Employment Service, OAED (Manpower Employment Organisation), adopted ESCO in 2021. It is the first Greek organisation to adopt ESCO.

To adopt ESCO, OAED has implemented the “MATCHING” (Mapping Arrangements and Transcoding Change In Greece) project, co-funded by the European Programme for Employment and Social Innovation (EaSI). The project included training for OAED’s employment counsellors (among others), peer learning from other relevant national and European organisations, as well as undertaking awareness-raising activities about ESCO.

ESCO is intended for use by: 1) OAED’s staff members to analyse the profiles of job seekers and details of job vacancies through OAED’s Integrated Information System; and 2) OAED’s clients (job seekers and employers) through OAED’s e-Services. Job seekers will be able to annotate their curriculum vitaes (CVs) with ESCO skills, and employers will be able to more accurately describe their job offers.

Source: European Commission (2018[52]), How ESCO supports the Public Employment Service of Iceland, https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/video/I-162745; OAED (2021[53]), OAED adopts the new ESCO classification of occupations and skills, www.oaed.gr/storage/oaed-logo/enimerotiko-entipo-esco-matching-en.pdf; European Commission (2022[54]), The adoption of ESCO by the Greek Public Employment Service (OAED), https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en/news/adoption-esco-greek-public-employment-service-oaed.

However, certain caveats will need to be kept in mind. For example, stakeholders have expressed concerns about the extent to which ESCO accurately reflects the skills requirements of certain occupations (especially occupations heavily reliant on digital skills). Nonetheless, for comparison, the inclusion of digital skills in the O*NET classification is even more limited. In fact, digital skills covered by the O*NET classification are limited to: 1) knowledge of computers and electronics; and 2) programming skills (Lassébie et al., 2021[55]). Stakeholders in Luxembourg have broadly agreed that despite certain shortcomings, ESCO was the most suitable skills classification, which could be adapted for use in Luxembourg’s context.

Recommendations

4.1 Improve the accuracy of occupational social security data by creating targeted incentives for employers, strengthening existing guidance tools for identifying the correct occupational codes, and conducting targeted awareness raising. IGSS and CCSS could design an online occupations dashboard using CCSS data, where employers could track the occupational, salary and/or demographic structure and evolution within their company. CCSS and ADEM could also work on creating links between CCSS employment entry declarations and ADEM vacancy declarations, whereby parts of CCSS declarations could be automatically pre-filled based on ADEM declarations to make the reporting process more straightforward for employers. Further, CCSS should improve the search functions of the existing occupational code search engine (e.g. by including descriptions of tasks related to occupations, developing a chatbot for real-time responses to queries, etc.) and consider making the search engine accessible in English, in addition to French. IGSS and CCSS should feature the existing guidance tools (i.e. the proposed occupations dashboard, occupational code search engine, etc.) more prominently on their respective websites and, in collaboration with employer representatives (e.g. UEL), design a regular reminder outlining the “common mistakes” of, and existing guidance tools for, identifying the correct occupational codes. In addition, IGSS and CCSS could expand their awareness-raising activities to include associations of HR professionals or payroll experts to target actors directly in charge of employment entry declarations. In turn, employer representatives (e.g. members of the UEL) should equally underline the importance of correctly declaring new hires to the CCSS in their own engagement activities with employers. In addition to undertaking efforts to strengthen the accuracy of the CCSS data, IGSS and other stakeholders in Luxembourg should still make use of the data to the extent possible (e.g. for the analysis of general growth trends across occupations).

4.2. Explore the possibility of including ADEM’s vacancy data in CEDEFOP’s Skills-OVATE tool. With ADEM’s vacancy data now published on a publicly accessible job board, CEDEFOP (via LISER) should explore the possibility of including ADEM data in CEDEFOP’s Skills-OVATE tool. As a result, it would be possible to regularly obtain information on occupational and skills trends in Luxembourg based on vacancy data from both ADEM’s own job board and online private job boards. The risk of counting certain vacancies twice (i.e. vacancies declared both to ADEM and on private job boards) would be minimised through CEDEFOP tools developed specifically for such a purpose.

4.3. Increase the share of job postings created and reported by employers to ADEM, by designing targeted incentives and services for employers, especially SMEs, and through employer-led awareness raising. ADEM could develop an online vacancy dashboard based on vacancy data declared to ADEM, which could provide employers with an overview of their vacancies (open and filled) over time and how quickly they are being filled. ADEM could also consider developing dedicated support services for SMEs (e.g. support with drafting job postings according to SMEs’ needs, sign-posting the available reskilling/upskilling opportunities for SME employees, etc.), whose capacities to engage in vacancy reporting tend to be restricted the most. Employer representatives (e.g. members of the UEL) should also further raise awareness about reporting vacancies to ADEM in their engagement activities with employers, in addition to highlighting the importance of correctly declaring new hires to CCSS (see Recommendation 4.1).

4.4. Review existing employer surveys, together with administrative data on skills needs to help assess the need for a national employer survey. Luxembourg should review the existing employer surveys carried out by non-governmental actors, in tandem with reviewing administrative data on skills needs (e.g. ADEM and Skills-OVATE vacancy data; see Recommendation 4.2) to identify information which: 1) would add value to Luxembourg’s labour market data collection but is currently not available in administrative datasets; and 2) is collected by existing employer surveys irregularly, inconsistently or not at all. The review of administrative data and existing employer surveys would help Luxembourg assess the need for introducing a national, cross-sectoral employer survey of skills needs and/or gaps. Such a national survey should reduce the need for multiple employer surveys in the long run and mitigate against the risk of “survey fatigue” in Luxembourg.

4.5. Adopt a skills-based occupational classification to link occupations to skills. ADEM should adopt a comprehensive and internationally recognised skills classification to facilitate matching job seekers to vacancies. For this purpose, ADEM could consider the use of ESCO, which links occupations to specific skills. ESCO could be equally used to help systematically define learning outcomes of adult learning courses, which would have significant benefits for Luxembourg’s education and training data collection (see Recommendation 1.4 and Recommendation 4.8).

Expanding the range and strengthening the granularity of Luxembourg’s education and training data

Luxembourg’s skills data collection includes a variety of education and training data that provides valuable information on Luxembourg’s skills supply (see Table 5.1 and Table 5.2). Going forward, stakeholders consulted during this review agreed that Luxembourg’s education and training data collection could be further expanded, and the granularity of the existing data further strengthened.

Data on education and training outcomes help shed light on the alignment of the education and training offer and the demands of the labour market (OECD, 2016[27]), helping policy makers to better tailor the education and training offer to labour market needs while supporting individuals in making informed skills choices (see Chapter 3 for an extended discussion on guiding and incentivising skills choices in Luxembourg). The key opportunities for strengthening Luxembourg’s data on education and training outcomes exist at the levels of higher education (HE) and adult learning.

At the HE level, graduate tracking is overseen and implemented by the University of Luxembourg. UoL is Luxembourg’s only public HE institution, with the UoL student population representing 99% of the total student population in higher education in Luxembourg (Eurostat, n.d.[56]).5 Since 2018, UoL has been collecting data on graduates’ (former master's and bachelor’s students) outcomes. UoL uses a graduate survey, implemented six months after graduation, asking graduates about their employment status, earnings, perceived skills mismatch, and use of skills on the job, among others. The survey is extended to all graduates (former master's and bachelor’s students). Around 30% of contacted graduates typically respond. As of 2022, UoL planned to include PhD graduates in the survey as well.

In 2020, UoL expanded its graduate tracking exercise by conducting a one-off “employment study” of graduates’ employment pathways using LinkedIn data. Based on LinkedIn data and anecdotal evidence from graduates’ supervisors, UoL was able to collect information for approximately 55% of its graduates (former master's and PhD students) having graduated between 2015 and 2019. UoL assembled a team of consultants who manually checked graduates’ LinkedIn profiles, while academic supervisors provided insights on graduates' employment pathways based on their knowledge. The evidence from academic supervisors was checked via desk research and only used if validated. Information on bachelor’s students was not collected due to time and resource constraints.

While UoL’s graduate tracking efforts are steps in the right direction, more could be done. For example, current graduate tracking efforts do not make it possible to gather data on how long it takes HE students to find a job post-completion of their studies, which could be useful (not only) to better facilitate the transitions of former international students into the labour market (see Chapter 4). It is also important to note that UoL’s survey results rely on self-reported information by graduates, while the survey’s response rate could be further increased. Moreover, the use of LinkedIn data for the purposes of the employment study can impact the representativeness of the graduate tracking results. Evidence suggests that low‑income individuals and those outside of the workforce tend to be under-represented on LinkedIn, while LinkedIn tends to be used frequently by individuals in knowledge-intensive sectors such as management, marketing, HE and consulting (Blank and Lutz, 2017[57]; van Dijck, 2013[58]). In addition, via the employment study, UoL gathered information on graduates’ first and current job titles and employers through LinkedIn, missing out on collecting other valuable data, such as information on earnings. As of early 2022, UoL does not plan to repeat the employment study.

Going forward, UoL could consider using administrative data for the purposes of graduate tracking and combining it with existing survey data (OECD, 2019[59]). Administrative data can provide a longitudinal view of graduates’ outcomes and could provide evidence on the time graduates take to transition into the labour market. Box 5.6 details how England (United Kingdom) combines administrative and survey data in its graduate tracking of HE graduates. In Luxembourg, administrative data (e.g. CCSS data) could provide comprehensive information (e.g. on the employment status, sector and earnings of graduates),6 at least for graduates who have remained in Luxembourg following the completion of their studies.7

Presently, the use of administrative data for graduate tracking in Luxembourg is precluded by the lack of necessary legal basis, which is required under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). However, in the context of the development of the NDEP (see Opportunity 2), Luxembourg is aiming to grant the necessary legal basis to the NDEP, thereby making the use of administrative data possible for graduate tracking purposes.

Should NDEP be capable of establishing connections to administrative databases of other countries, especially in the Greater Region (see Recommendation 4.14), the collection of information about outcomes of HE students receiving financial aid from the Government of Luxembourg but studying outside Luxembourg8 or graduates who had studied in Luxembourg but left the country after the completion of their studies, could equally be facilitated.

To complement administrative data with information that is not available in administrative databases (e.g. how useful the university experience was in preparing graduates for the labour market, skills used on the job, etc.) (OECD, 2019[60]), UoL could link administrative data to its existing graduate survey by using unique identifiers. It could also consider expanding the survey to gather information from former international students about reasons for leaving Luxembourg post-completion of their studies in order to support efforts to better foster the transition of former international students into Luxembourg's labour market (see Chapter 4). LinkedIn data could be considered as an additional source of information to cross‑check the UoL graduate survey and administrative data and fill potential gaps in the latter two.

Box 5.6. Relevant international examples: Higher education graduate tracking

England (United Kingdom)

England tracks the outcomes of HE graduates by combining administrative and survey data.

The Longitudinal Employment Outcomes (LEO) dataset links school census, Further Education, Higher Education Statistics Agency and Her Majesty’s (HM) Revenues and Customs data to obtain information on graduates’ employment and earnings. From 2019/20, a Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS) of HE graduates was commissioned to complement LEO. LEO and GOS are linked via unique identifiers, creating a merged dataset.

Conducted 15 months after graduation, GOS is a census survey that complements LEO by collecting self-reported, qualitative information from graduates about their job roles (e.g. their duties and responsibilities) and the extent to which they use the skills developed during their studies. GOS is managed by the Higher Education Statistics Agency and is carried out by a combination of online and telephone interviews. Higher education institutions (HEIs) support GOS implementation by providing up-to-date contacts of their graduates.

GOS contains core and optional questions. The core questions cover: 1) job title and duties, including supervision responsibilities; 2) how the current job was found; 3) what further study have they conducted since graduation; 4) skills from their course that they are using in their work; and 5) current activities and future plans. HEIs can include optional questions in GOS for a fee.

HEIs can access the raw survey data for business planning purposes and to evaluate HEI teaching standards in the Teaching Excellence Framework in England.

Source: European Commission (2020[61]), Graduate tracking - A "how to do it well" guide, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5c71362f-a671-11ea-bb7a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search.

While there is space for improving Luxembourg’s data on education and training outcomes of HE graduates (see above), there are no measures in place for tracking the outcomes of graduates from adult learning, either publicly or privately provided.