This chapter introduces the definitions of child labour and forced labour, provides a general overview of the scale of the issue, and argues why businesses should care about human rights in the cocoa sector.

Business Handbook on Due Diligence in the Cocoa Sector

Child labour and forced labour in the cocoa sector

Abstract

Understanding child labour and forced labour

Child labour and forced labour are both a symptom and a consequence of systemic poverty. These complex challenges are not limited to the cocoa sector and have several root causes, including poverty, lack of access to quality essential services and infrastructure such as education, health care, social protection; challenges with enforcing legal and regulatory frameworks; a lack of decent employment opportunities; gender inequality; low levels of adult labour (often linked to low wages in a given sector); challenges with access to land tenure; and the availability of effective corporate due diligence programmes.

Definition of child labour

Not all work carried out by children is child labour. According to the ILO, children’s and adolescents’ participation in economic work that does not affect their health and personal development or interfere with or prejudice their schooling or their participation in vocational orientation or training programmes is generally regarded as positive and therefore acceptable child work/light work. Child/light work is work that is generally non-hazardous, performed for fewer than 14 hours per week and by children aged 13 or older, when permitted by local law (ILO/IOE, 2015[5]).

Two ILO Conventions define child labour:

The Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138) defines “child labour” as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to their physical or mental development including by interfering with their education by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. It also sets the minimum age for work at 15 years (13 years for light work), and 18 years for hazardous work (16 under certain strict conditions) (ILO, n.d.[6]).

The Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention 1999 (No. 182) defines four categories of the worst forms of child labour (ILO, n.d.[7]):

a) All forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale, trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict.

b) The use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of pornography or for pornographic performances.

c) The use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the production and trafficking of drugs as defined in the relevant international treaties.

d) “Hazardous work” which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children. The precise nature of those prohibited tasks is to be defined and reviewed by each country.

Categories a), b) and c) are known as unconditional forms of child labour, meaning they are prohibited without regard to the age of the child, the nature and the tasks executed, the conditions and circumstances in which those tasks are executed. Category d) is a conditional worst form of child labour, hence the need to be defined locally through a nationally defined list of hazardous activities.

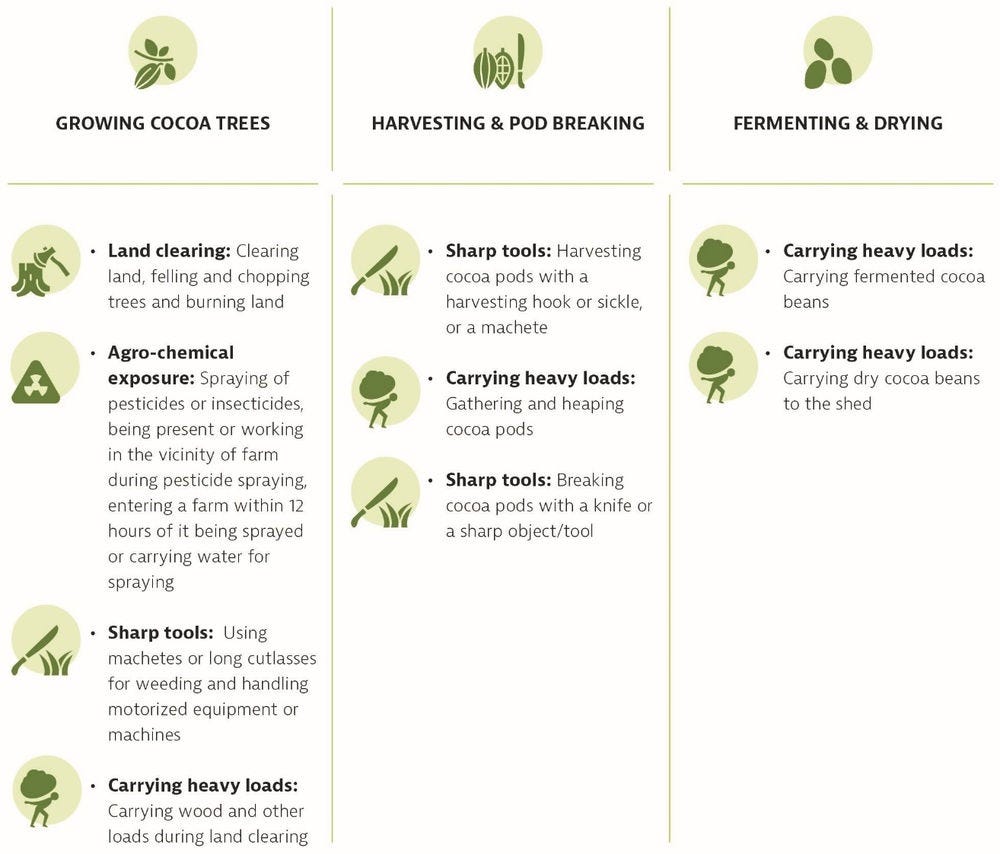

In the cocoa sector, a majority of children involved in child labour are undertaking hazardous work, including carrying heavy loads, using dangerous tools and being exposed to pesticides. A small percentage of these children are reported to be in forced labour situations.

In addition, the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) adopted in 1989, protects children from economic exploitation including the right to be protected from work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development; protects children from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse; and protects children from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse (UN, n.d.[8]).

Figure 1. Examples of hazardous child labour on cocoa farms

Source: Adapted from interviews conducted with farmers in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire and Sadhu (2020[9]), Assessing Progress in Reducing Child Labor in Cocoa Growing Areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Cocoa%20Report/NORC%202020%20Cocoa%20Report_English.pdf

Definition of forced labour

Forced labour is defined by ILO Convention No. 29 (1930) as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily” (ILO, n.d.[10]). “Menace of any penalty” refers to the means of coercion used to impose work on someone against that person’s will, during recruitment or once the person is working. “Involuntary work” refers to any work taking place without the free and informed consent of the worker. A forced labour situation is therefore determined by the nature of the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator and not by the type of activity performed. There must be both coercion and a lack of free and informed consent for work to be regarded as forced labour.

Forced labour can apply to both adults and children. Children are considered in forced labour when one or more of the following situations apply (ILO, 2018[11]):

Work performed for one or both parents who are themselves in a situation of forced labour.

Work performed under the menace of any penalty applied by a third party, either to the child directly or the child’s parents.

The child is performing work which can be classified under one of three types of the worst forms of child labour: a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, b) the use of a child for prostitution, production of pornography or for pornographic performances, c) the use of a child for illicit activities such as production and trafficking of drugs.

How prevalent is child labour and forced labour in the cocoa sector?

Cocoa is an important commodity in the agricultural sector, with cocoa beans being the major ingredient of chocolate. About 70% of the world’s cocoa originates from Africa, with Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana being the leading producers accounting respectively for 44% and 16% of global cocoa production in 2019‑20 (ICCO, 2022[12]). Southeast Asia and Oceania, and Latin America also contribute to global cocoa production at 6% and 19% respectively (ICCO, 2022[12]).

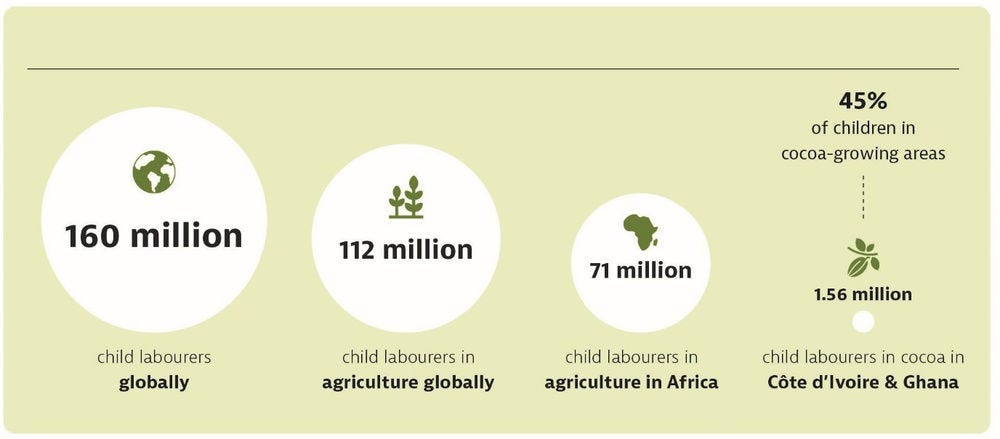

The international community has committed to “taking immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms” (Alliance 8.7, 2018[13]). However, the latest global estimates indicate that 160 million children were still in child labour across all sectors in 2020, with 70% of all children in child labour (representing 112 million children) working in the agriculture sector (ILO/UNICEF, 2021[14]). The US Department of Labour provides data on the prevalence of child labour and forced labour in specific countries.1

Figure 2. Scale of child labour in the cocoa sector

Source: ILO/UNICEF (2021[14]), Child Labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward, https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_797515/lang-en/index.htm; Sadhu (2020[9]), Assessing Progress in Reducing Child Labor in Cocoa Growing Areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Cocoa%20Report/NORC%202020%20Cocoa%20Report_English.pdf

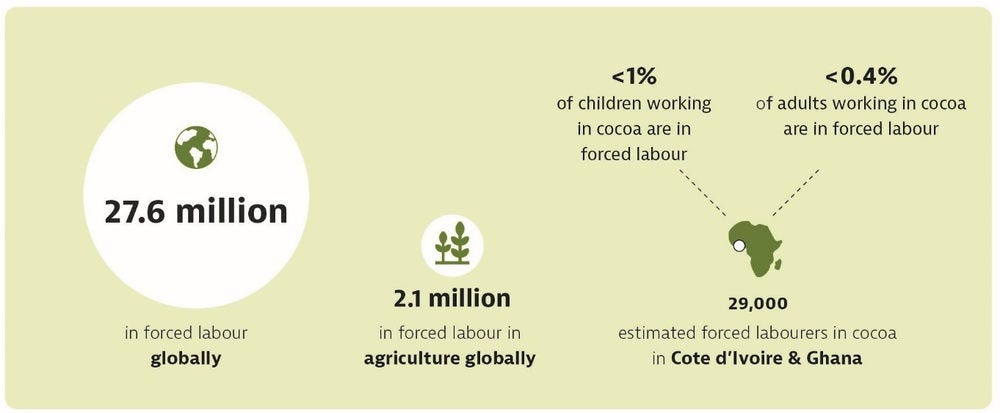

Figure 3. Scale of forced labour in the cocoa sector

Source: ILO/Walk Free/IOM (2022[15]), Global Estimates Of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour And Forced Marriage, https://www.walkfree.org/reports/global-estimates-of-modern-slavery-2022/; Sadhu (2020[9]), Assessing Progress in Reducing Child Labor in Cocoa Growing Areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Cocoa%20Report/NORC%202020%20Cocoa%20Report_English.pdf; Tulane University, Walk Free Foundation (2018[16]), The prevalence of forced labour and child labour in the cocoa sectors of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/walk-free-foundation-study-prevalence-forced-labour-and-child-labour-cocoa.

What are the characteristics of the cocoa supply chain and how do they impact company due diligence efforts?

Globally 90% of cocoa is produced by smallholder farms ranging from five hectares or less (ICCO, n.d.[17]), representing 5 to six million farmers (Kozicka M., Tacconi F. , Horna D. , Gotor E., 2018[18]). Cocoa beans change hands multiple times in the supply chain, moving from producers to aggregators, to traders and exchanges, and then onto processors. Processors are typically located overseas, in countries such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States. Over 36% of the annual cocoa bean harvest is ground in Europe and nearly 8% in the United States. Ground cocoa is sent on to chocolate/cocoa product manufacturers and brands, and thereafter to retailers (ICCO, 2022[19]).

In Ghana, farmers mainly sell their cocoa beans to community-based procurement clerks that are contracted by licensed buying companies regulated by the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) (Fairtrade Foundation, 2020[20]). In Côte d’Ivoire, farmers either sell their cocoa through a co‑operative, or through local traders known as pisteurs, who typically trade with approximately 25 to 30 farmers. Pisteurs deliver the cocoa beans to larger licensed traders (Fairtrade Foundation, 2020[20]).

More than 50% of cocoa farmers in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are reported to be not part of co‑operatives (up to 1.69 million people) and are thus a challenge for midstream and downstream companies to account for in their supply chain mapping and traceability efforts (Fairtrade Foundation, 2020[20]). While some companies have made progress in increasing transparency over their sourced cocoa, many are still lacking visibility over the origins and the conditions under which the beans were produced or harvested. Thus, implementing effective due diligence that identifies, prevents and addresses child labour and forced labour at scale remains a challenge for the sector.

Box 1. Why should businesses carry out due diligence?

When effectively applied, risk-based due diligence can help businesses identify and prevent adverse impacts on human rights, thus respecting international frameworks, demonstrating business efforts to investors and regulators, and contributing to the SDGs in a measurable way. Business carries out due diligence because of:

Commercial value: Due diligence provides businesses with clarity on where risks are in the supply chain, enabling them to pro‑actively get in front of problems, identify opportunities to meet customer and market needs and potentially build value. Integrating due diligence into corporate risk management systems helps strengthen the overall management of business and builds supplier and stakeholder engagement to increase business resilience. Increased transparency over the supply chain can also better position companies to access new capital and better financial terms.

Regulatory requirements: Governments are increasingly legislating to oblige enterprises to conduct due diligence to identify and address human rights and environmental risks in global supply chains. In 2022, the European Commission published a draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), intended to become a leading standard for responsible business conduct, as well as a proposal to ban products made with forced labour from the EU market. Several European countries, such as France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have introduced laws with different degrees of due diligence obligations for businesses. Outside Europe, similar legislative approaches have been adopted in Australia and the United States (UNICEF, 2022[21]).

Societal expectations: Consumers, buyers, employees, and citizens expect companies to respect human rights as a minimum standard of “doing business”. In the cocoa sector these expectations are especially high given the prevalence of child labour and the high rates of environmental degradation for a product which is considered as a “nice to have” or luxury item. Due diligence helps a company to “know and show” how it contributes positively to society, thereby helping protect its reputation.

Note

← 1. For further information, visit https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor