In line with Step 2 of the OECD due diligence framework, this chapter explains how companies can develop a complete picture of their cocoa supply chain to identify, assess and prioritise potential and actual adverse human rights impacts such as child labour and forced labour.

Business Handbook on Due Diligence in the Cocoa Sector

Step 2: Identify, assess and prioritise child labour and forced labour risks in the supply chain

Abstract

Strategic questions for enterprises to ask

Have you mapped your cocoa supply chain to identify your key business relationships?

Do you have a clear understanding of the conditions under which your cocoa beans/ground beans have been harvested, processed and transported?

Have you reviewed the risk management practices of suppliers in the cocoa supply chain at risk for child labour and forced labour?

For manufacturers, brands, retailers (and in some cases processors): Have you identified the “control points” in the cocoa supply chain? Are you able to engage with these control points to verify that they are conducting due diligence in according to OECD recommendations?

For processors (when applicable), traders, distributors, transporters, farms and co‑operatives: Do you know where your cocoa beans and raw materials are coming from – for example which countries, which farms, which intermediary enterprises beyond your immediate suppliers?

Following risk identification, is risk assessment and prioritisation of adverse impacts on human rights being done based on likelihood and severity rather than those that are easiest to fix?

Has your company engaged with relevant stakeholders to understand the local context and stakeholders’ role in identifying and assessing human rights risks, including child labour and forced labour?

Identify and assess actual and potential adverse human rights impacts associated with the enterprise’s operations, products or services

Map the supply chain

Companies should conduct a high-level mapping of the supply chain and systematically work towards a fuller picture. A high-level mapping requires identifying the various actors involved, including when relevant the names of immediate suppliers and business partners and the sites of operations.

Mapping can be complemented with data and information from certification and traceability schemes, company certifications, public summaries of audit reports and records of visits to cocoa production, transformation or storage sites. The extent of information collected by enterprises on business partners depends on the severity of the risks (in the case of child labour and forced labour risks this would be high) and how closely linked the enterprise is to the identified risk.

Upstream versus downstream: The OECD recommendations for supply chain due diligence generally group companies operating along supply chains into upstream and downstream companies. In the agriculture sector, companies in the production sector are considered upstream companies. As highlighted earlier, this covers farmers, including small to large family farms, farmer organisations, co‑operatives and private enterprises, as well as companies that invest in land and directly manage farms or plantations. All other companies – i.e. wholesalers, traders, transportation companies, manufacturers of food, feed and beverages, textile and biofuel producers and retailers and supermarkets are considered companies in the downstream segment of the supply chain.1 Such a differentiation might not strictly apply to all companies in the cocoa sector. While farmers and co‑operatives are generally considered as upstream actors, and manufacturers, brands and retailers as downstream actors, processors (refiners and grinders), traders, distributors and transporters could at times be allocated to either one of these categories depending on their business model and where they operate. In this Handbook, we have listed the specific types of companies to which a recommendation applies to.

Downstream companies (such as manufacturers, brands and retailers and in some cases processors), that are several tiers removed from the source of cocoa production may not be able to map all their suppliers and business partners initially. To do so may require working through the tier‑1 and sub-tier suppliers, as well as with multi-stakeholder or industry initiatives. Downstream companies should systematically work towards a complete picture of their business relationships over time, prioritising cocoa coming from countries, regions and communities that are at the highest risk of child labour and/or forced labour.

Farms and co‑operatives should be able to provide the name of the producer unit and/or co‑operative; address and site identification; contact details of the site manager; cocoa quantity, dates and methods of production; number of workers by age and gender; list of risk management practices; transportation routes; and risk assessments that have been undertaken.

Processors, transporters, traders and distributors could request the above information from producers while documenting similar information for their own operations. Where information is not available, efforts should be undertaken to collect it in collaboration with the farms and co‑operatives. Verification of information should be undertaken through on-site visits where possible. Several large cocoa traders use Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to identify farms and co‑operatives co‑ordinates in higher-risk countries. Once mapping is complete, this information can be used to help to identify more particular risk factors for child labour and forced labour, as well as other salient risks such as deforestation, at the regional and community level.

Manufacturers, brands and retailers should find out what information exists and is shared from their upstream business partners and incorporate this information into their supply chain mapping. Downstream companies are expected to identify and work with businesses operating at control points (also known as choke points) of the supply chain to verify that these entities are conducting due diligence in accordance with OECD recommendations.

Control points are businesses operating at key transformation points in the supply chain, such as processing, who have greater visibility and leverage over suppliers upstream in the supply chain.2 Control points are typically situated in the part of the supply chain with relatively few actors, that process a majority of a given commodity, and have a good level of visibility over the circumstances of production and trade of the upstream supply chain. Control points in the cocoa supply chain could include, for example, traders, grinders and cocoa exporters or importers.

Identify risks and impacts in each part of the supply chain

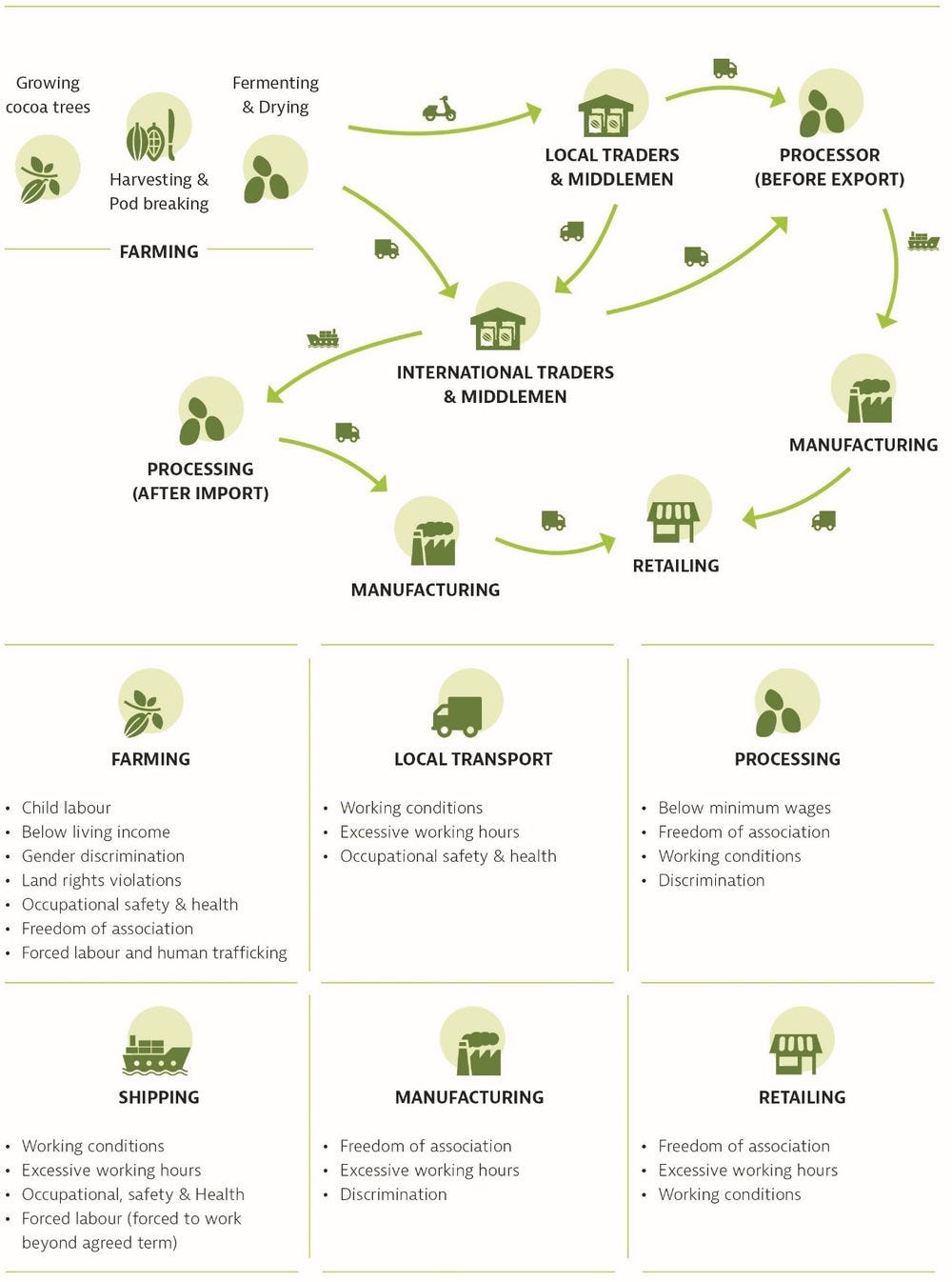

Once the supply chain is mapped, companies should identify the main human rights risks and impacts along the supply chain. Figure 6 provides a simplified schema of the cocoa supply chain and points in the chain where human rights risks, including that of child labour and forced labour, can typically be found.

This step of due diligence can be conducted using reports on the cocoa sector and supply chain, information from suppliers and industry associations, multi-stakeholder initiatives, investigative reports from NGOs and international organisations focused on child labour and forced labour impacts, as well as a company’s own research on the sector and prevalent human rights issues.

Figure 6. Human rights risks across the cocoa supply chain

Source: Adapted from UNICEF (2018[23]), Children’s Rights in the Cocoa-Growing Communities of Côte d’Ivoire: Synthesis Report, https://sites.unicef.org/csr/css/synthesis-report-children-rights-cocoa-communities-en.pdf; ICI (2020[24]), Cocoa Barometer 2020, https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/2020-cocoa-barometer.

Assess child labour and forced labour risks and impacts in cocoa supply chains

Once the overall risks and impacts along the supply chain are identified, companies can undertake a more detailed assessment of child labour and forced labour risks and impacts.

When completing a risk assessment, it is important to:

Regularly review each stage of production and trade, and consider new and emerging trends, including drivers of child labour and forced labour in the region, the type and size of farms as well as the policy, legal, economic, social or contextual causes that can lead to child labour and forced labour.

Collaborate with local authorities and stakeholders on the ground to support risk assessment and farm level monitoring.

Put in place systems such as Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS), to prevent, identify and address child labour and forced labour and report on results to the designated senior management.

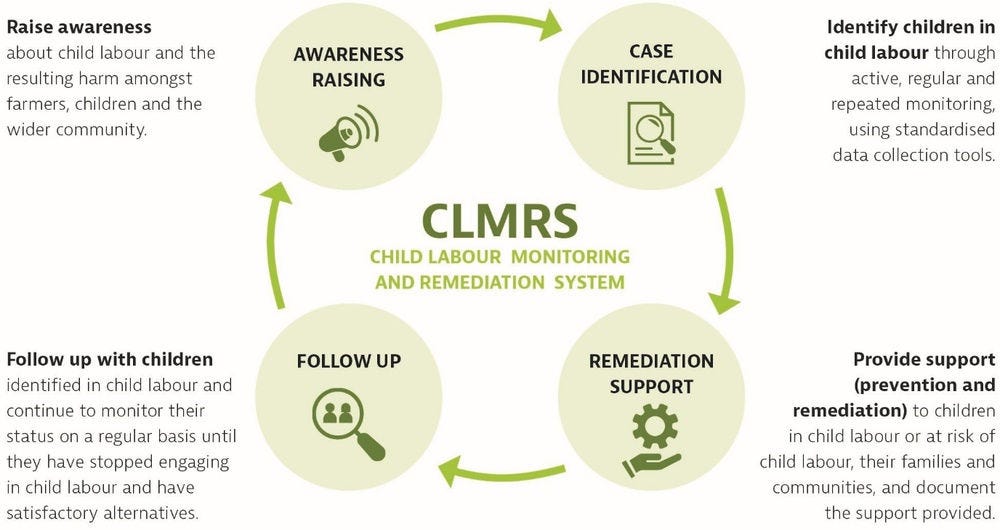

Companies operating in the cocoa sector will most likely have identified child labour and forced labour as severe human rights issues at the farming level. CLMRS is a tool that can help identify and assess risks in more detail (in addition to providing prevention and remediation support). CLMRS are built around community facilitators (often farmers themselves) who are connected to cocoa-farming co‑operatives. They visit households, raise awareness on the dangers of child labour, and identify children engaged in hazardous work. Box 4 provides more information about CLMRS.

Box 4. Where do Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS) fit into risk‑based due diligence?

CLMRS can be a way to undertake human rights due diligence in relation to child labour. The concept was initially developed by the ILO to monitor child labour in a wide variety of geographic contexts and across supply chains. In 2012, ICI adapted the CLMRS to the cocoa sector and today, CLMRS are used by many companies.

A recent benchmarking study defines that any effective CLMRS (ICI, 2021[25]) should be able to perform four core functions:

Raise awareness on child labour and resulting harm amongst farmers, children and members of the wider community

Identify children in child labour through an active monitoring process, using standardised data collection tools

Provide prevention and remediation support to children in child labour, and others at risk, and document the support provided

Follow-up with children identified in child labour to monitor their status on a regular basis until they have stopped engaging in child labour.

Figure 7. ICI’s Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS)

Note: For further details, see section on Reaching scale and impact to address child labour and forced labour through collaboration: Provide for or co‑operate in remediation when appropriate.

Source: Adapted from ICI (n.d.[26]), Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation Systems: Introduction, https://clmrs.cocoainitiative.org/introduction

Resources to help companies assess risks and impacts of child labour and forced labour

There are a number of useful resources available to help companies assess the risk and impacts of child labour and forced labour. Table 2 can be used as a guide to help businesses assess the level of risk of child labour and forced labour associated with specific indicators.

Table 2. Considerations and risk indicators for assessing child labour and forced labour in cocoa sourcing

|

Consideration |

Indicators |

Suggested Questions |

Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Development Context of the Country or Region related to Cocoa Sourcing |

Economic

Social and Contextual

|

|

|

|

International Framework (Legal and Policy Framework) |

|

|

|

|

National Regulatory Environment (Legal and Policy Framework) |

|

|

|

|

Child Labour Specific Risk Indicators |

Prevalence data on child labour is the best indicator of the likelihood of child labour. Where data on child labour prevalence is unavailable or not specific to the region, farmer group, or community, factors known to be correlated with higher child labour prevalence can help identify where risks may be higher. At community level:

At household level:

|

|

|

Source: ICI (2019[27]), Using community-level data to understand child labour risk in cocoa-growing areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana: Executive summary, https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/using-community-level-data-understand-child-labour-risk-infographic; ICI (n.d.[28]), Protective Community Index, https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/protective-community-index; ICI (n.d.[29]), Community Child Labour Risk Assessment – Data Collections Tools, https://www.cocoainitiative.org/knowledge-hub/resources/community-child-labour-risk-assessment-data-collections-tools; Sadhu (2020[9]), Assessing Progress in Reducing Child Labor in Cocoa Growing Areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Cocoa%20Report/NORC%202020%20Cocoa%20Report_English.pdf.

Identifying and assessing forced labour can be challenging since many forms of coercion and exploitation are hidden. Within the cocoa sector, victims may also be located in isolated areas and inaccessible to community monitors. ICI and Verité have worked together to examine how the ILO forced labour indicators can be used to identify cases of forced labour in the cocoa sector. Table 3 can be used as a guide to help businesses assess the level of risk associated with the different indicators. As a general rule, the presence of one indicator under “involuntariness” and one indicator under “menace of penalty” requires immediate action. Preventative action is recommended if at least one indicator exists under either “involuntariness” or “menace of penalty”. The second table shows common indicators for both “involuntariness” and “menace of penalty” in the cocoa sector.

Table 3. Operational-level forced labour indicators

|

Indicator of involuntariness |

Indicator of penalty / menace of penalty |

Forced labour |

Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

At least one |

At least one |

Yes |

Red case Action required |

|

At least one indicator |

None |

At risk |

Orange case Preventive action recommended |

|

None |

At least one indicator |

At risk |

Orange case Preventive action recommended |

|

None |

None |

No |

Green case No action required |

Source: Adapted by Verite and ICI, from ILO forced labour indicators.

Table 4. Common indicators for the cocoa sector

|

Indicators of involuntariness |

Indicators of menace of penalty |

|---|---|

|

|

Box 5. Considerations if you are a...

Farmer and co‑operative, trader, distributor, transporter or processor (when applicable):

Mapping the supply chain, identifying and assessing risks and impacts

Help co‑operatives generate and share credible, verifiable, reliable and up-to-date information on the extent of human rights risks and harms, including child labour and forced labour risks. If the data does not exist yet, local staff may be able to collect it, or, if needed, establish a dedicated assessment team to do so.

Ensure that effective and meaningful consultations with local communities and farmers are held to identify risk, as they are often a good source of information and alerts.

Use existing supply chain data (including the age and education level of the producer and their children, farm size, number of workers) to establish a risk model.1

Use methodologies such as CLMRS to identify children in and at risk of child labour. Specific vulnerability factors linked to the risk of forced labour of children can also be integrated into CLMRS.

Share the results of your company’s risk assessments with downstream enterprises, especially where these assessments identified risk or impacts of child labour and forced labour.

Manufacturer, brand, retailer and in some cases processor:

Mapping the supply chain

Work with your first-tier suppliers to get visibility on the source of cocoa, including identifying control points. Establish systems of control further upstream in the supply chain.

Consistently request and underline the importance of knowing the source of your cocoa and having visibility of the business relationships involved.

Support upstream companies or organisations who may have less capacity to map their supply chain by investing in building capacity and resources.

Identifying risks and assessing impacts

Review the due diligence measures put in place by your suppliers or directly assess their operations, for instance, by conducting visits to farms and their communities.

Seek information on both the suppliers’ systems and the volumes of products they are supplying.

Consider participating in industry-wide schemes and multi-stakeholder initiatives to obtain relevant information and support your own assessments.

Request documentation from upstream companies, such as evidence that the supply chain has been mapped and farms within the supply chain are identified, evidence of risk assessments and on-the‑ground monitoring, and stakeholder engagement reports at the community and farm level.

SME – upstream and downstream

Mapping the supply chain

Work in collaboration with other businesses, for example, through national cocoa platforms, industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives to increase leverage and demand for systems of control (including chain of custody and/or traceability) and supply chain transparency.

Engage with credible certification schemes aligned to OECD recommendations on due diligence to build greater transparency in your supply chain.

Identifying risks and assessing impacts

Make use of the wide range of resources from industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives and government agencies available as these can help provide up-to-date information to assist your company in evaluating risks. There are resources that help SMEs to carry out risk analyses for cocoa-growing countries with which they co‑operate.2

Some small chocolate producers buy cocoa directly from the farmers and have a very detailed knowledge of their supply chain. Purchasing cocoa directly from producers can also simplify the process of identifying and assessing risk as farmers have knowledge of the conditions under which the cocoa is grown and harvested.

1. To learn more about risk models, visit ICI’s website (ICI, 2021[30]).

2. To find more resources, visit German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa’s webpage (SÜDWIND e.V., 2021[31]).

Notes

← 1. See OECD-FAO Guidance (OECD/FAO, 2016[2]) p.20 Figure 1.1. on the various stages of agricultural supply chains and enterprises involved.

← 2. For further details, see Box 5. Engagement with business relationships operating at control points in the supply chain of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance (OECD, 2018[3]) and page 38 of the OECD-FAO Guidance (OECD/FAO, 2016[2]).