The government of Uzbekistan launched a wide-ranging programme of reforms in 2017 in order to accelerate the transition to an open, market-based economy. The country is now on a pathway to a sounder economic and fiscal footing, but the success of these strategic ambitions depends on the resolution of long-standing issues in the business climate. Addressing these issues is also critical to enabling the broader structural transformation of the country’s economy, which despite having started in the mid-1990s, remains at a relatively early stage.

Insights on the Business Climate in Uzbekistan

2. Transformation and structural change in Uzbekistan’s economy

Abstract

2.1. Private sector development amid stalled structural transformation

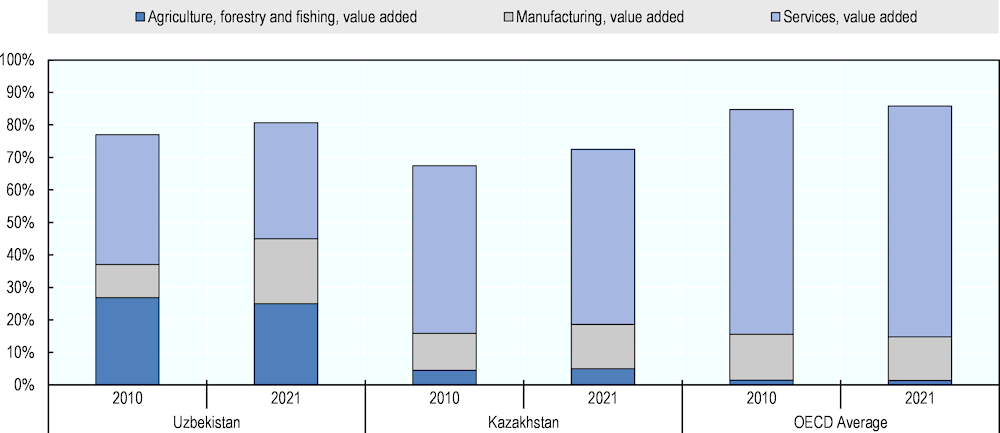

The structural transformation of Uzbekistan’s economy that began in 1991 remains at a relatively early stage. In large part, this stems from limited success in reorienting resources – human and capital – from historically important sectors characterised by low levels of job creation and productivity to newer, more productive uses. While the value added of agriculture as a percentage of GDP has decreased from 27% in 2010 to 25% in 2021, it remains the highest level in Central Asia, and significantly higher than Kazakhstan (5%) and the OECD average (1%). By contrast, the value added of manufacturing has doubled from 10% to 20% of GDP over the same period, higher than both Kazakhstan (14%) and the OECD average (13%) (Figure 2.1 )

Figure 2.1. Value added of the agricultural, manufacturing and service sectors (% GDP)

The weight of services in value creation remains limited. In 2021, the value added of the services sector amounted to 35.7%, the second lowest in Central Asia after Tajikistan (35.3%), and significantly below the OECD average of 71%. This is a lower level than the equivalent figure in 2010 (40%) and indicates a divergence with the other major Central Asian economy, Kazakhstan, where the services share grew from 52% to 54% over the same period. These figures indicate that, while recent efforts to liberalise the economy are significant and positive steps, there remains a great deal of work to do with the structural transformation of the country to one where more people are employed in higher rather than lower productivity sectors.

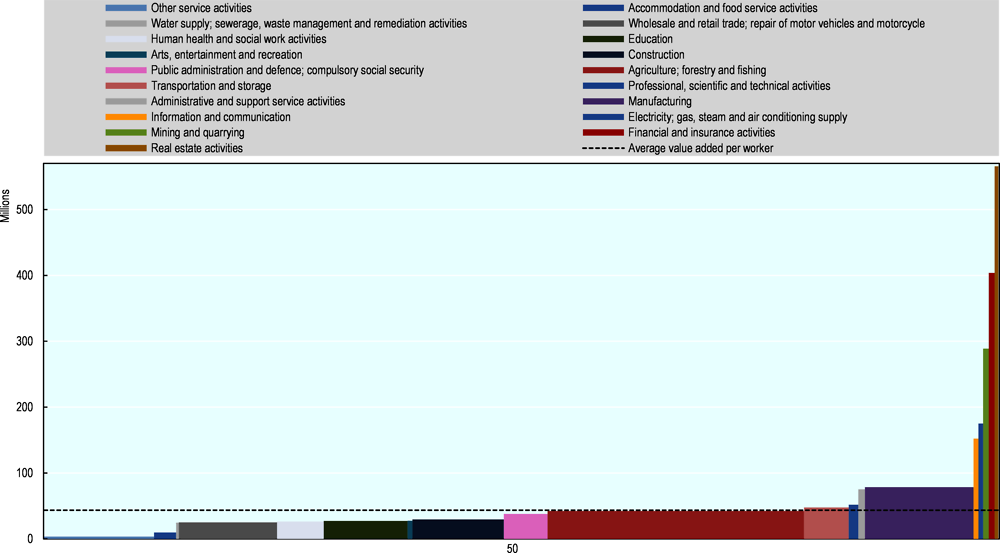

The distribution of employment similarly attests to challenges with structural change and difficulties in achieving growth that is inclusive. Over 80% of the population are employed in sectors where productivity is half or below half of the national average (Figure 2.2), though the high degree of economic informality in Uzbekistan – particularly in low productivity sectors such as trade and agriculture – that persists in the country may mean that there are in fact more workers in lower productivity activities than official data suggest. The agricultural sector accounts for 27% of total employment, with value added per worker averaging UZS 42.5 million (around USD 3780); the agricultural share in employment is the second highest in the region behind Tajikistan (46%) and significantly higher than the OECD average of 5%. At the same time, the sectors with the highest levels of productivity – real estate activities, financial and insurance services, mining, ICT – account for a very small proportion of employment. The challenge for policymakers is ensuring that the benefits of strong macroeconomic performance of the country are distributed throughout society in a way which is inclusive and underpins social cohesion.

Figure 2.2. Value added per worker and sectoral share of employment, 2020 (in UZS)

Note: Horizontal axis runs 0-100%. It is important to note that the chart does not show informal employment, which remains significant in Uzbekistan as in other countries in Central Asia.

Source: OECD calculations based (ILO, 2023[3]) and (UN, 2023[1])

As in other Central Asian economies, there is a link between the depth and resilience of structural change and diversification. To a significant extent, the expansion of Uzbekistan’s service sector – whether it is job creation in high-value services like finance or lower-value ones like retail and hospitality – has been driven by rents from the trade of minerals and migrant labour. This is not to diminish successes in creating high-quality service sector jobs in Uzbekistan, but to highlight the link between diversification and the resilience of the non-tradable sector.

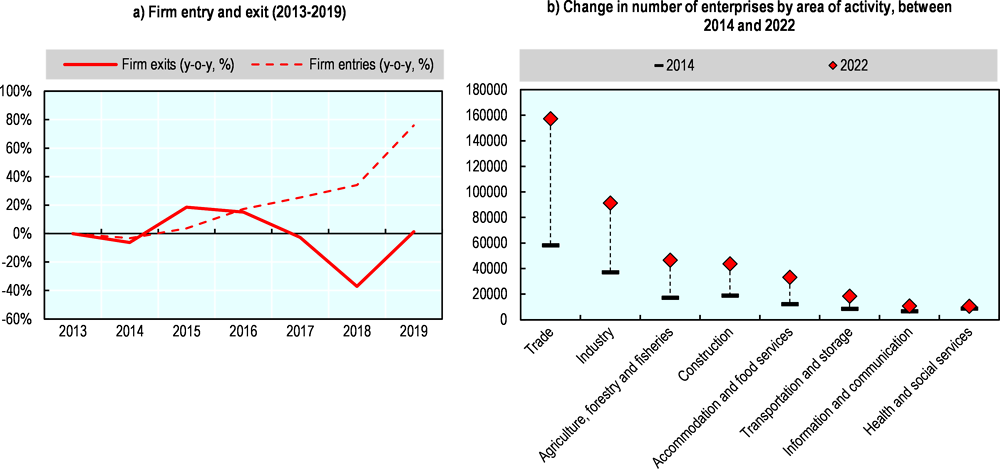

Since the government began a programme of market liberalisation in 2016/17, business dynamism has significantly increased. Following several years of relatively stagnant enterprise growth, the number of firm entries – the creation of new firms in the economy – grew rapidly from 2016, with a particular acceleration from 2018 onwards (Figure 2.3). At the same time, the number of firm exits – the liquidation or bankruptcy of previously active firms – fell markedly. Trends in firm growth were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the number of firms exiting the market growing precipitously in 2020-21, though the number of new firms continued to grow during this period. The industries in which the highest rates of firm creation have been observed are in (retail) trade, industry, and agriculture.

Figure 2.3. Business dynamism in Uzbekistan

Note: Data from 2020 and 2021 have been omitted from panel 1 due to the exceptional number rate of firm exits (enterprise liquidations) that occurred that year, though in actual terms firm entries (creations) still significantly exceeded exits; 2013 = 0. Panel 2 shows the change in the number of enterprises by economic activity, running left to right on the horizontal access based on the magnitude of change between 2014 and 2022; data for ‘other industries’ have been omitted.

Source: OECD calculations based on Uzbekistan’s enterprise data (The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, 2023[4])n.

High-growth firms (in particular start-ups) tend to be concentrated in service sectors, and it is precisely in a number of these sectors where the lowest rates of firm creation have been seen in Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, the generally positive trends in business dynamism take place in the context of an extensive programme of market liberalisation, a large part of which has focussed on making it easier to start and close a business. In addition to the regulatory environment, there are a number of factors that can affect business dynamism, many of which are relevant to both the BCA and to other areas of OECD work in the country: integration into global value chains (GVCs), access to finance, occupational standards and labour market regulation all play a role (OECD, 2021[5]).

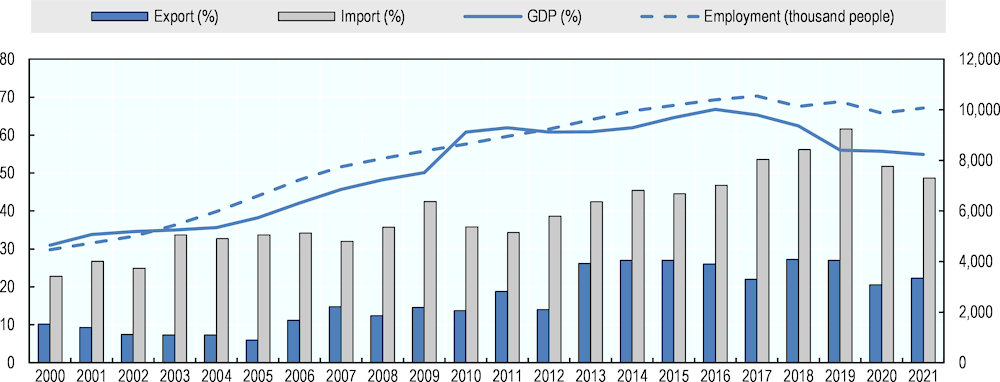

The weight of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and private entrepreneurship in the economy has increased since 2000. In 2000, 4.5 million workers were employed in SMEs, and SME output accounted for 31% of GDP. By 2021, SME employment had grown to 10.1 million, equal to 86% of total employment, and SME output accounted for 54.9% of GDP. Nevertheless, a burgeoning SME sector does not necessarily equate to private sector development, since many SMEs are in essence state-owned enterprises (SOEs), with the share of truly private firms difficult to ascertain from official statistics.

Figure 2.4. SME share in trade, GDP and employment (2000-2021)

Source: OECD calculations based on data from (The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, 2023[4])

The contribution of SMEs to trade is growing, but firm internationalisation is held back by productivity challenges. From 2000 to 2021, the share of SMEs in imports doubled from 22.8% to 48.7%, while their share of exports grew from 10.2% to 22.3% (Figure 2.4 ). This historical trade deficit may partly be explained by the sectoral distribution of SMEs in the economy and their productivity level, with many of Uzbekistan’s SMEs’ being concentrated in low-productivity sectors an impediment to trade (Melitz, 2003[6]). The widening deficit in recent years may also be a factor of firms importing larger amounts of capital goods to upgrade and modernise their capacities. As of 2023, there remains insufficient data on the extent of indirect exports to Russia, i.e., the share of trade with Russia where Uzbekistan acts as an intermediary between a third market and Russia. In 2022, 97.2% of all firms in agriculture were SMEs, while the figure for construction was 74.9%, with these two sectors being characterised by low levels of productivity. In contrast, the most significant sectoral share of newly registered SMEs in the first half of 2022 was trade (36.9%) and industry (18.9%), indicating a trend of positive firm growth in higher productivity, export-orientated sectors.

Uzbekistan is experiencing rapid demographic expansion, raising the importance of quality job creation and labour market inclusion. The economy creates around 280,000 new jobs per year on average, less than half of the 600,000 new jobs required to keep up with labour force expansion (World Bank, 2019[7]). Following the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Uzbekistan has also seen significant inflows of highly skilled Russian migrants (OECD, 2022[8]). In the absence of sufficient job creation, labour migration will likely persist. Remittances from labour migrants, amounting to 13.3% of GDP in 2021, remain an important driver of household consumption (particularly for food products), but their importance for consumption also raises the economic exposure of Uzbekistan to downswings in key external labour markets, such as Russia (OECD, 2022[8]). At the same time, levels of urbanisation in Uzbekistan remain low – this is something that the government acknowledges. A Presidential Decree from 2019 called for the rate of urbanisation to increase to 60% by 2030 (ILO, 2021[9]). People and capital generally gravitate to places of greater economic potential, but barriers to the reallocation of land (for example, to construct more affordable housing in urban centres, a major barrier for many looking to move to major cities), capital, and labour can all distort this process. The ongoing government consultation to remove the propiska system (a system of internal permissions for labour mobility, which has historically been an impediment to rural-urban internal migration) could significantly alleviate constraints on urban migration (Seitz, 2020[10]).

There is significant progress yet to be made on the process of the transformation of the state as from the primary producer of economic output to an enabler of it. The government is gradually beginning to refashion its role in economic development as an enabler of private sector development and investment, for example, by improving the framework conditions – skills, access to finance, infrastructure, etc. – necessary for entrepreneurship. Historically, however, industrialisation and growth have been overwhelmingly state-directed. The consequences of this model for current challenges facing private sector development are significant. For one, due to a policy focus before 2017 on self-sufficiency, economic development was promoted through state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which were generally protected from competition through regulatory exemptions and often were monopolies in their respective sectors. In the agricultural sector, the focus was extractive and did little to improve productivity. The authorities have begun a programme of corporatisation and privatisation, though this remains at an early stage of implementation.

The dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in historically important sectors – principally mineral extraction and agriculture – as well as in key network sectors, has been a major impediment to structural transformation. The output of Uzbekistan’s roughly 2,000 (SOEs) continue to account for around 50% of the country’s GDP, 18% of employment, and 20% of exports (World Bank, 2022[11]). The footprint of SOEs also varies significantly across regions, with the contribution of SOEs to regional output ranging from 26% in the Namangan region to 80% in Navoi and Karakalpakstan (Abdullaev, 2020[12]). Estimates for the true scale of the presence of the state vary, often upwards, owing in large part to difficulties with statistical collection and classifications (the authorities and statistical agencies only consider ‘state unitary enterprises’ with 100% state ownership to be SOEs, masking a vast number of companies with partial – often majority – state ownership, and thereby understating the true footprint of the state in the economy). A 2014 World Bank report, for example, calculated that 37% of the workforce were employed in SOEs, with another 34% self-employed, meaning that SOE employment accounted for over half of total wage employment in the country (World Bank, 2014[13]). The presence of SOEs in the banking sector is considerable, with state-owned banks holding 88% of all outstanding credit in the country at the end of 2020 (World Bank, 2022[11]). Despite the lack of clarity, there is a general consensus that the presence is large enough to force nascent market institutions to the margins of the economy, where their ability to shape the socio-economic direction of Uzbekistan will be limited (Abdullaev, 2020[12]).

The interaction between the pervasive presence of SOEs in the economy and structural transformation is complex and multifaceted. In a context where the government is actively seeking to foster the creation of high-quality jobs for a rapidly expanding labour force, the extensive presence of SOEs creates a myriad of challenges that will continue to frustrate private sector development: soft budgetary constraints on SOEs contribute to inefficiencies, poor governance of incumbents, subsidies to support below cost-recovery services and the impact on investment. Taken together, the extent of SOE presence in the economy, the poor governance and oversight of many of these enterprises, and the location of these SOEs in key network sectors, all contribute to make the playing field for business uneven, limiting the effectiveness of otherwise encouraging reform efforts to improve the business and investment climate in the country.

2.2. Growth, trade and investment: relevant economic trends for private sector development

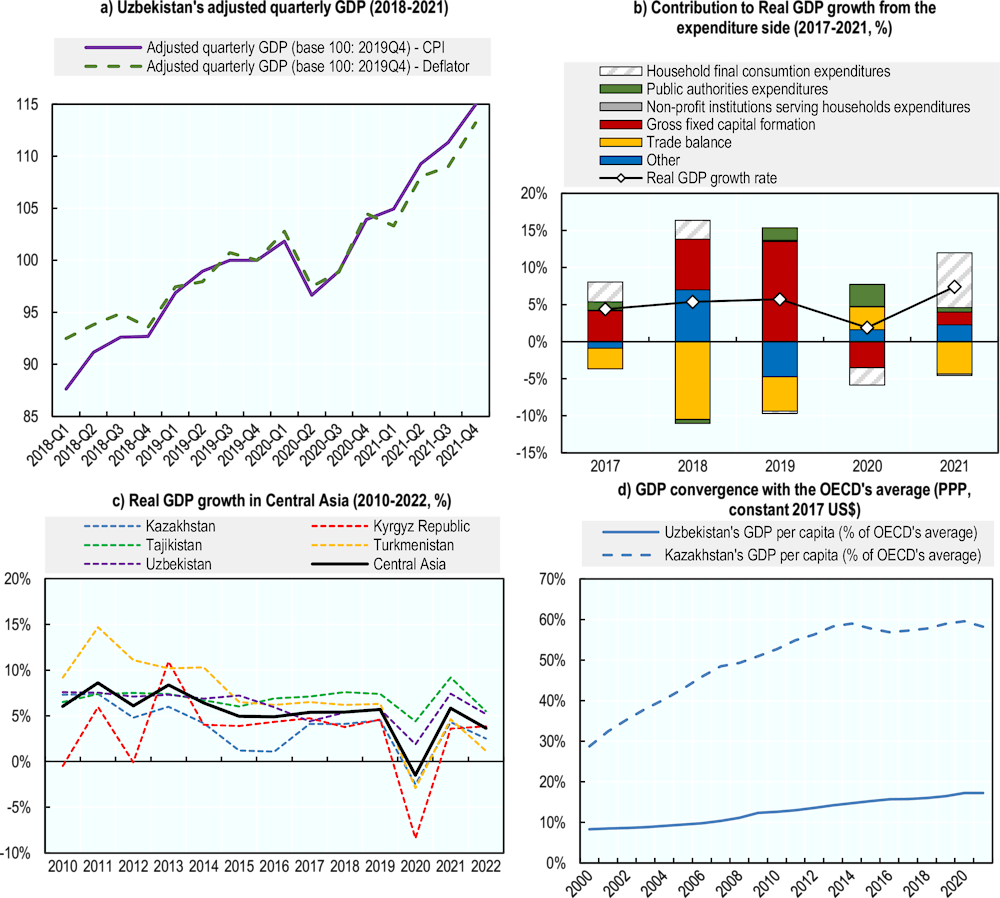

From a macroeconomic perspective, Uzbekistan has made significant progress since beginning its transition to a market economy in the early 1990s. Since Uzbekistan emerged from the post-transition recession in 1996, Uzbekistan’s real GDP has grown by an average annual rate of 5.9%, above the regional average of 5.3% (World Bank, 2023[2]). Gross FDI stocks in the last pre-pandemic year of 2019 equaled 16.6% GDP, an four-fold increase since 2000, while net inflows were equal to 3.9% GDP, an increase of 680% and 35% over the same period as above (UNCTAD, 2023[14]) (World Bank, 2023[2]). From 2010 to 2021, there was a sevenfold increase in labour productivity, measured in terms of value added per worker in million UZS, while levels of poverty, the reduction of which is a key ambition of the government, have fallen by 88% since 2000 (measured as the percentage of employed living on below USD 1.9 PPP per day). In 2021, unemployment fell from 10.5% to 9.4%, a level that Uzbekistan had generally sustained in the years preceding the pandemic. External debt reached 57.8% GDP in 2021, below the legal threshold of 60%, with this having expanded significantly in recent years (IMF, 2022[15]).

Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) has made a major contribution to growth in recent years (Fig. 2.4b). GFCF has primarily been driven by public investment, with levels of domestic private and foreign direct investment remaining low (IMF, 2022[15]). For the domestic private sector, access to finance remains a key challenge, in part due to the underdevelopment of the national banking sector and pervasive role of the state therein; for larger firms, the underdevelopment of local capital markets is an additional barrier. SMEs suffer from particularly difficult access to finance conditions, owing in large part to demanding collateralisation requirements and the high cost of credit, with some 64% of SMEs reliant on internal resources for investment (OECD, 2021[16]). Credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP has grown significantly since 2016, going from the lowest in Central Asia (11.8%) to the highest (35.7%), though this remains far below the OECD average of 160.7% GDP and has been accompanied by a rapid increase in non-performing loans (NPLs). An additional constraint is the difficulty in differentiating between lending growth to the real private sector and growth to enterprises with differing degrees of state control (World Bank, 2023[17]).

The collapse of investment – public and private – following the COVID-19 pandemic had an immediate and significant impact on real GDP growth, though trend growth remains positive (Figure 2.5 a). Since 2019, the contribution of GFCF to GDP growth remains subdued, and tighter global monetary conditions will make it more difficult for the state to remain the country’s lead investor, raising the importance of policy support for domestic lending and FDI attraction. At the same time, the role of household consumption as a contributor to growth has expanded significantly (Figure 2.5 b).

Figure 2.5. Real GDP growth and contributions to growth

Source: Panels A and B, OECD calculations based on national accounts data from State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics (The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, 2023[18]); Panels C and D OECD calculations based on World Bank data (World Bank, 2023[2]).

Whilst it is important not to diminish Uzbekistan’s economic performance, the country’s generally strong post-transition macroeconomic trends follow an established convergence trajectory. The economic development literature suggests that capital-scarce emerging economies grow faster than capital-rich developed countries because of diminishing marginal returns to investment, to which an early part of Uzbekistan’s economic performance may be attributable (Abramovitz, 1986[19]) (Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 2004[20]). Against this longer-term trend, the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine actually came on the back of a challenging decade. Buffeted by a series of powerful external shocks – the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09 and then the end of the commodity price boom in 2014-15, which affected the country through its deep trade and labour linkages with Russia – it appeared that the commodity-driven and cyclical growth paths that were prevalent throughout the region had begun to run out of steam: growth remained strong but was slowing (Figure 2.5 c), and convergence with OECD countries has begun to stagnate; the convergence gap with Kazakhstan has also continued to widen (Figure 2.5 d) (OECD, 2021[21]).

The reform process that started in Uzbekistan in 2017 was in part in response to the need to do things differently to achieve sustainable, inclusive, and resilient growth. The basic premise of these reforms was to enable the private sector to play a larger role in the economy, to diminish the role of the state in the economy, and to improve the country’s economic buffers. Early macroeconomic indicators suggest that these reforms may already have started to put the country’s economy on a sounder economic and fiscal footing. Between 2017 and 2019, Uzbekistan recorded average annual growth of 5.2%, slightly below the Central Asia average of 5.5%. Stronger fundamentals, good policy buffers – a low public debt to GDP ratio (though one that has risen significantly in recent years), strong international reserves, remittances, etc. – together with high gold prices (a key export) have enabled the country to mitigate the worst of the pandemic (IMF, 2022[15]) (OECD, 2021[21]). In 2022, the economy again appears to have performed relatively well in absorbing the shock of Russia’s war in Ukraine, with GDP growth in 2022 of 5.2%, though this in part may be due to certain one-off factors such as the rapid increase in household consumption.

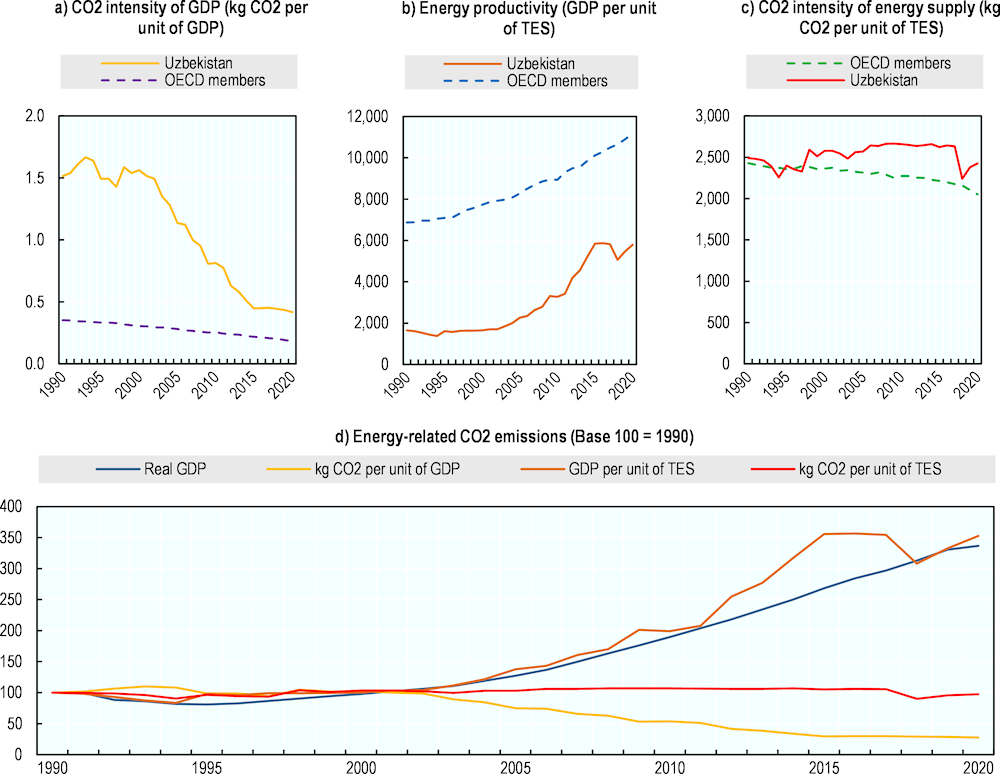

Although Uzbekistan has one of the most energy-intensive economies in the world, the country is increasing the productivity of emissions and energy consumption relative to growth. Uzbekistan’s CO2 intensity – the volume of CO2 required to produce 1 USD PPP of output – fell almost 75% between 2000 and 2020, but current levels (0.43kg CO2/USD PPP) remain 77% above the world average (Figure 2.6 a) (IEA, 2022[22]). At the same time, 1 tonne equivalent of oil (TOE) in Uzbekistan produced USD 5,524 of output in 2020, a level, whilst much higher than in 2000 (e.g., the same 1 TOE would have produced less output in 2000), remains far below the OECD average, where the equivalent TOE would produce twice as much output (Figure 2.6 b). The persistently high levels of CO2 emissions and energy required for Uzbekistan’s growth is due to a number of energy-intensive industries and the dominance of fossil fuels in the country’s energy supply (Figure 2.6 d). Nevertheless, the cost of inefficiency and emissions are profound for both the government and society of Uzbekistan. The OECD Environment Directorate estimates that Uzbekistan has by far the highest level of premature deaths due to particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure in Central Asian (around 800 per 1,000,000 inhabitants), and that the welfare costs of premature mortality due to exposure to PM2.5 pollution amount to around 10% GDP in 2019 (OECD, 2022[23]).

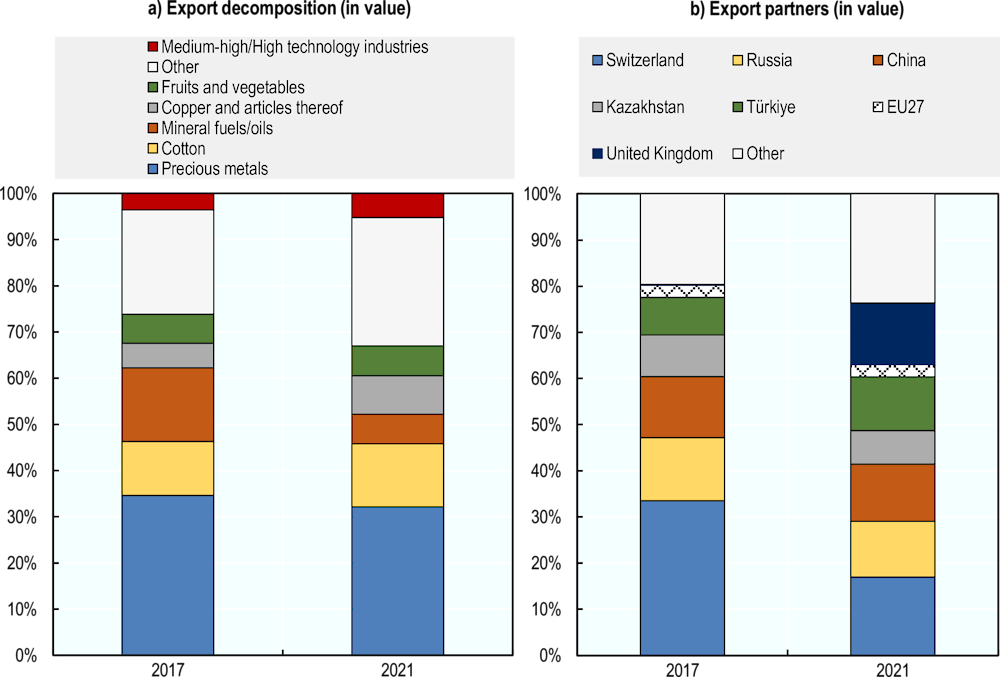

Figure 2.6. CO2 and energy intensity of Uzbekistan’s economy

Reforms to support international trade were a major component of the broader reform process that began in 2017, with the recent resumption of accession talks between Uzbekistan and the WTO a further indication of the country’s internationalisation. Since 2016, trade as a percentage of GDP has more than doubled from 29% of GDP – at that point the lowest level in Central Asia – to 64% in 2019, though part of this increase may be attributable to currency liberalisation reforms. The country continues to run a sizable trade deficit, one which in recent years may have widened due to the need to invest in capital goods to modernise and expand the industrial base. Exports are dominated by low-tech, largely primary goods: gold, cotton, and some additional mineral and fuel products account for the largest share of the country’s export basket (Figure 2.7). In contrast, medium- and high-tech products account for a very small share of exports, indicating either a low-level of export-orientation of these industries or a lack of the more knowledge- and technology-intensive capacities necessary to develop them.

Figure 2.7. Structure of trade: export basket and partners

Note: Medium-high/High technologies classification have been computed according to the ISIC REV.3 Technology Intensity Definition (OECD, 2011). Among the “Other” category, the top three exported products are textile, plastics and articles thereof and finally fertilizers.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from (UN Comtrade, 2023[25])

In 2021, Switzerland was Uzbekistan’s largest export market, accounting for 17% of the country’s exports. The significant share of Switzerland as a share of Uzbekistan’s export partners reflects the importance of the European country for the refining of gold, as well as the importance of gold in Uzbekistan’s exports, with 99.9% of Uzbekistan’s exports to the Swiss market accounted for by the precious metal. Other major export partners include the United Kingdom (13.3% of exports), China (12.4%), and Russia (12.1%). The composition of the country’s export basket varies significantly depending on the country, with exports to the United Kingdom, as with Switzerland, being almost entirely gold. In contrast, exports to other markets, such as China, Russia and Turkey, are more varied, though primary and low-technology content goods predominate. Given the connectivity penalty Uzbekistan suffers, it is unsurprising that its largest trading partners for lower value-to-weight goods are geographically proximate. The share of exports to the EU27 remains small (2.7%), though this figure may rise in the years ahead following the introduction of a Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP+) trade facilitation agreement between the EU and Uzbekistan in April 2021.

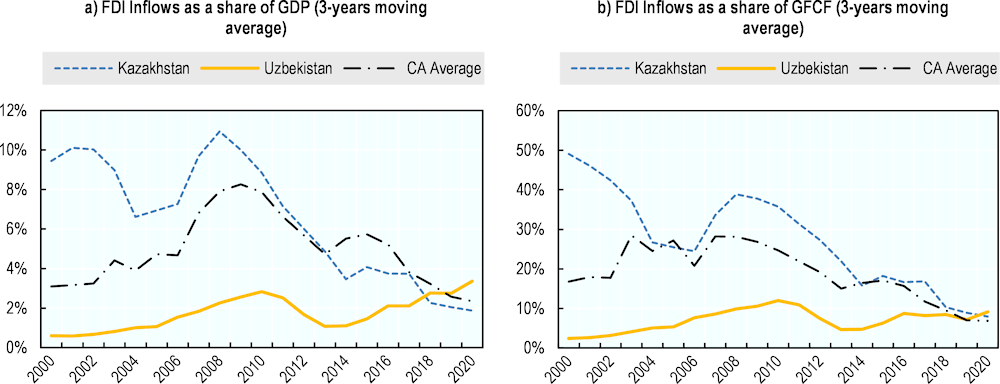

Owing in large part to a highly restrictive investment regulation, FDI levels in Uzbekistan have historically been much lower than other countries in Central Asia. Yet, since around 2014, FDI as a share of GDP and as a share of total GFCF have been trending upwards, whilst the reverse has been true of the broader region (Figure 2.8) This in part reflects the easing of strict investment and currency regulations that had deterred foreign investors from entering Uzbekistan, though it perhaps also is reflective of the types of opportunities available to investors in Uzbekistan relative to other regional economies, such as the size of the domestic market. Increasing the share of FDI in Uzbekistan’s GFCF is a key aim of the government, but success will depend both on addressing long-standing issues facing the domestic business climate as well as other regulatory and structural issues that are particularly challenging for international investors, such as the lack of a developed domestic capital market and a lack of co-financing vehicles such as public-private partnerships (PPPs).

Figure 2.8. Foreign direct investment in Uzbekistan

While Uzbekistan has so far managed the economic spillovers of Russia’s war in Ukraine relatively well, a prolonged conflict could pose serious challenges to socio-economic wellbeing in Uzbekistan remain substantial. Russia continues to account for over 20% of imports and 12% exports, while much of Uzbekistan’s external trade passes through Russia – underdeveloped trade connectivity between Uzbekistan and other regions means that external trade risks becoming more complicated and more expensive for the country (IMF, 2022[15]). Another important channel that affects Uzbekistan is remittances, levels of which remained close to 10% GDP in 2021 and of which almost 75% originated in Russia. One in six households in Uzbekistan relies upon remittances as the primary income source and account on average for 20% of household incomes (Ibid.). As in other areas of the world, rising commodity prices – notably food (wheat) and fuel) – may feed into inflation, which remained over 10% throughout 2022 (OECD, 2022[27]).

References

[12] Abdullaev, U. (2020), State-Owned Enterprises in Uzbekistan: Taking Stock and Some Reform Priorities, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. No. 1068, Asian Development Bank Institute, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/560601/adbi-wp1068.pdf.

[19] Abramovitz, M. (1986), Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind, The Journal of Economic History, No. Vol. 46, No. 2, Cambridge University Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2122171?seq=1.

[20] Barro, R. and X. Sala-i-Martin (2004), Economic Growth (2nd ed.), The MIT Press, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/BarroSalaIMartin2004Chap1-2.pdf.

[22] IEA (2022), Uzbekistan 2022: Energy Policy Review, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/0d00581c-dc3c-466f-b0c8-97d25112a6e0/Uzbekistan2022.pdf.

[3] ILO (2023), ILOSTAT, ILO, Geneva, https://ilostat.ilo.org/.

[9] ILO (2021), Towards Full and Productive Employment in Uzbekistan: Achievements and Challenges, Employment Country Reports Series, ILO, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---sro-moscow/documents/publication/wcms_782059.pdf.

[15] IMF (2022), Republic of Uzbekistan: 2022 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for the Republic of Uzbekistan, IMF, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/06/22/Republic-of-Uzbekistan-2022-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-519919.

[6] Melitz, M. (2003), The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity, Econometrica, No. Vol. 71, No. 6 (Nov. 2003), The Econometric Society, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1555536.

[24] OECD (2023), Green Growth Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GREEN_GROWTH.

[23] OECD (2022), Green Economy Transition in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia: Progress and Ways Forward, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/c410b82a-en.pdf?expires=1677162424&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=F2BCEEF95E86BA77A3ACBB7C97571F14.

[27] OECD (2022), Weathering Economic Storms in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/publications/weathering-economic-storms-in-central-asia-83348924-en.htm.

[8] OECD (2022), Weathering Economic Storms in Central Asia: Initial Impacts of the War in Ukraine, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/83348924-en.pdf?expires=1674661005&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=D702728E79EA5A3E54D1B3CA7ED454E9.

[21] OECD (2021), Beyond COVID-19: Prospects for Economic Recovery in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Beyond_COVID%2019_Central%20Asia.pdf.

[16] OECD (2021), Boosting the Internationalisation of Firms through better Export Promotion Policies in Uzbekistan, OECD Eurasia Policy Insights, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Monitoring_Review_Uzbekistan_ENG.pdf.

[5] OECD (2021), Understanding Firm Growth: Helping SMEs Scale Up, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fc60b04c-en.

[10] Seitz, W. (2020), Free Movement and Affordable Housing: Public Preferences for Reform in Uzbekistan, World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, No. No. 9107, World Bank, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/595891578495293475/pdf/Free-Movement-and-Affordable-Housing-Public-Preferences-for-Reform-in-Uzbekistan.pdf.

[18] The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics (2023), National Accounts, The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, Tashkent, https://stat.uz/en/official-statistics/national-accounts.

[4] The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics (2023), Small Business and Entrepreneurship, The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, Tashkent, https://stat.uz/en/official-statistics/small-business-and-entrepreneurship.

[1] UN (2023), Value added by industries at current prices (ISIC REV. 4), United Nations, New York, http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=SNA&f=group_code%3A204.

[25] UN Comtrade (2023), UN Comtrade Database, UN Comtrade, Geneva, https://comtrade.un.org/.

[26] UNCTAD (2023), Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual, UNCTAD, Geneva, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740.

[14] UNCTAD (2023), UNCTATStat, UNCTAD, Geneva, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

[17] World Bank (2023), Domestic credit to private sector (% GDP), World Bank, DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FS.AST.CGOV.GD.ZS?end=2020&locations=UZ-KG-TJ-KZ-OE&start=2011&view=chart.

[2] World Bank (2023), World Bank Development Indicators, World Bank, DC, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

[11] World Bank (2022), Uzbekistan: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic, World Bank, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/933471650320792872/pdf/Toward-a-Prosperous-and-Inclusive-Future-The-Second-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic-for-Uzbekistan.pdf.

[7] World Bank (2019), Toward a New Economy: Uzbekistan Country Economic Update Summer 2019, World Bank, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/866501562572675697/pdf/Uzbekistan-Toward-a-New-Economy-Country-Economic-Update.pdf.

[13] World Bank (2014), The Skills Road: Skills for Employability in Uzbekistan, World Bank, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/744581468230693258/pdf/910100WP0P14350d000Uzbekistan0Final.pdf.