The OECD recently carried out a Public Service Leadership and Capability (PSLC) Review of Brazil, which analyses the country’s public employment and management systems against the fourteen principles of the OECD PSLC Recommendation. This summary includes targeted recommendations to support a fit-for-purpose public service that embeds the flexibility needed to meet current and future public challenges.

Public Employment and Management 2023

4. OECD public service leadership and capability review of Brazil

Abstract

Brazil is taking important steps to update and modernise its well-established, professional public service made up of skilled and dedicated public servants (Box 4.1). For example, the government has been developing digital services and human resource management systems, putting in place more opportunities for workforce mobility, supporting ministries in undertaking better workforce planning, and creating more opportunities for leadership development. However, there remains scope to link up isolated policies and initiatives to improve their impact, and to simplify some of the legal and structural complexities of the public service career system. Many of the issues addressed in this project look at addressing rigidities in the public employment system, with a view to making it more flexible and able to meet the complex changes faced by Brazil’s public service.

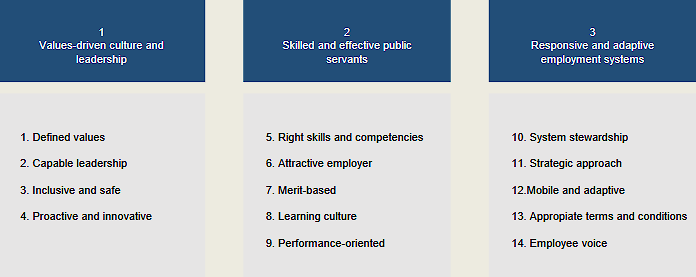

The OECD Review of Brazil’s Public Service Leadership and Capability is the first of its kind – a new approach to peer reviews structured around the 14 principles of the OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (Figure 4.3). The Review began with a scan of workforce management practices across all 14 principles of the OECD Recommendation, conducted in the autumn of 2022. This was followed by a deeper dive into three priority areas for reform: redesigning the career system for a modern and agile public sector, strengthening flexibility through better management of temporary contracts, and developing a mature performance management system. The process benefitted from peer input from representatives from France and Portugal, who shared their experience designing and implementing civil service reforms in these priority areas.

Box 4.1. The size and shape of public employment in Brazil

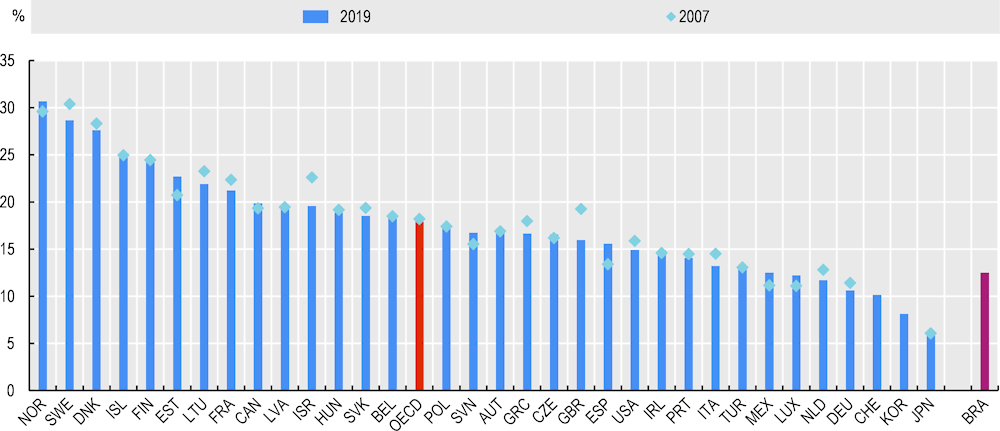

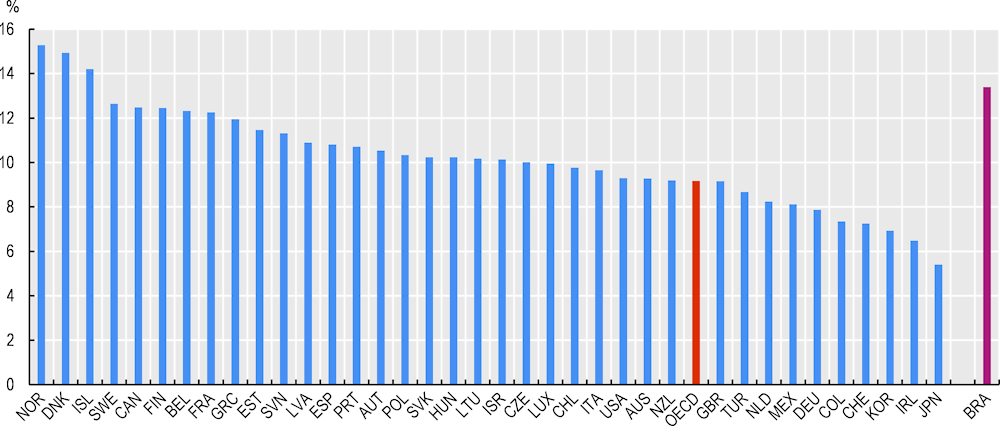

In Brazil, government employees represent 12.5% of total employment, slightly below the OECD average of 17.9%, but above the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) average of 11.9% (Figure 4.1) (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2021[2]). However, the expenditure in Brazil for compensation of public employees is relatively high. The compensation costs are 13.3% of GDP (public enterprises excluded), compared to the average for OECD member countries (9.2%) as well as LAC countries (8.9%) (Figure 4.2) (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2021[2]). Given this high investment in public employment, the public service should set out to achieve the most value from this investment to promote a professional, capable and responsive public service that is able to provide efficient public services responsive to the needs of citizens.

Figure 4.1. Employment in general government, 2007 and 2019

Note: Data for Australia and New Zealand are not available. Data for Korea and Switzerland are not included in the OECD average due to missing time-series. Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Luxembourg, Norway and Switzerland: 2018 rather than 2019. Japan: 2017 rather than 2019. Iceland and the United States: 2008 rather than 2007.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2021[2]).

Figure 4.2. Compensation of general government employees, 2019

Note: Data for Chile and Türkiye are not included in the OECD average because of missing time series or main non-financial government aggregates. Data for Japan, Brazil and Russia are for 2018 rather than 2019.

Source: OECD National Accounts Statistics (database). Data for Australia are based on a combination of National Accounts and Government finance statistics data provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Figure 4.3. OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability

Source: OECD (2019[3]), “OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability.htm.

The first pillar of the OECD PSLC Recommendation focuses on a values-driven culture and leadership. In this area, the scan finds that Brazil has taken some steps to strengthen the senior level public service by consolidating the system to better distinguish managerial roles throughout the hierarchy and introducing minimum criteria for appointment. The National School of Public Administration (ENAP) has worked with entities to develop a leadership pipeline and train future leaders. Furthermore, LA-BORA!gov (a learning and innovation lab in the Ministry of Public Management and Innovation) and ENAP have been crucial in putting forward innovative solutions to public policy challenges. However, the Review encourages Brazil to expand the implementation of these initiatives throughout the public service and embed them in a broader vision of the senior level public service in Brazil. The Review also identifies important gaps in the area of diversity and inclusion where there is a need to develop policies beyond quotas and collect better data.

The second pillar of the PSLC Recommendation centres on skilled and effective public servants. The Review recommends that Brazil systematically identify the changing skills needed and integrate skills development with learning opportunities. This is limited, in part, by the career systems which are not flexible enough to recruit and assess new skill sets. Recruitment processes are very transparent, but there is scope to introduce modern assessment methodologies of candidates’ competencies. More appropriate assessment methodologies could be identified, while also clarifying the role of private sector organisations in running the assessments. The Secretariat of Personnel Management and Performance (Secretaria de Gestão de Desempenho de Pessoal, SGP) could use the authorisation process of the opening of new recruitment competitions more strategically to underline the need for strategic future-oriented competencies.

The third pillar of the Recommendation highlights responsive and adaptive public employment systems. Within the public employment system of Brazil, the SGP has a broad mandate to set operational standards. The progress in the digital transformation of the public service provides an opportunity to delegate more strategic HR management tasks to the HR units as more operational tasks are automated. However, this needs to be accompanied by measures to build capacities within the HR units to take on more strategic people management. This should be reflected in a strategic approach to public employment which reinforces existing efforts for workforce planning to build a more forward-looking public service. Lastly, nascent efforts to measure and strengthen employee engagement could be followed-up with decisive actions to take steps towards a more open and engaging public sector culture.

Underpinning many of the challenges across the three pillars is a need to simplify the career system, which is the legal and structural foundation of Brazil’s public employment system. While the SGP has undertaken some efforts to reduce the numbers of the careers and harmonise the system, a broader reform process stands to improve public service efficiency.

While a full-scale reform of the career system likely requires a long-term perspective, and will depend on broad political support, various short- and medium-term steps can be undertaken to address the fragmentation, rigidity and inequities of the system. Specific recommendations include:

Simplify the career system by developing a vision of an ideal career system based on functions and transversal skills, and work towards that vision by reducing overlap of careers, combining careers with the same functions, harmonising employment conditions and developing common job profiles that include transversal and future-oriented skills.

Ensure salary equity by reviewing comparable functions across careers to set common basic salaries for new careers.

Establish common criteria for career progression which take into account professional development and performance, and work towards a career progression system where levels of responsibility and expertise increase as public servants move up the career ladder.

Strengthen workforce flexibility through improved mobility by developing common frameworks that underline the value of transversal competencies and skills; reducing barriers for public servants to change careers when warranted; building on and further promoting existing programmes for mobility; and considering mobility in promotions and performance reviews. As recommended in the OECD Centre of Government Review of Brazil (OECD, 2022[4]), this could also help to foster co-ordination between centre of government entities.

Flexibility can also be strengthened by improving the strategic use of temporary contracts. This may help to meet short-term and immediate needs as well as recruiting specific in-demand skills. In order to do so, Brazil could:

Update the conditions for hiring temporary employees. This would include a broad reflection among key stakeholders on the terms and conditions for temporary employees which should avoid creating a two-tiered system. Simplified recruitment could also be considered.

Explore measures and policies to better respond to surge capacity and punctual needs, such as improved mobility.

Mitigate the risk of abuse of the temporary scheme by limiting the amount of time temporary employees can be hired and rehired, ensuring conflict-of-interest policies are implemented and observed, and ensuring recruitment procedures meet a common high standard for merit and transparency.

Finally, reinforcing the performance management system stands to provide better incentives for public servants. Key recommendations to strengthen the performance management system are to:

Harmonise performance processes and modalities across careers to develop a standard that can be expected by all public servants. This includes giving responsibility of the assessment process to the host entity regardless of the career.

Simplify the performance rating system to a 3-point scale, and set the middle point (2) as the default score for all public servants.

Address underperformance by developing a mechanism to tackle underperformance through professional development and regulating performance-related dismissal as an option of last resort.

Align organisational and individual goals by strengthening ImpactaGOV, a strategic learning and development body, and further integrating the People Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento de Pessoas) and individual objectives.

Reinforce the capabilities of managers by providing better guidance, training and support on conducting performance assessments and dealing with underperformance.

Building on the insights and recommendations of these outputs, the OECD, in co-ordination with the SGP, developed guidelines for establishing or merging careers in the Brazilian public service. The guidelines put forward a common vision on structuring careers based on simplifying the career system, encouraging transversal careers across entities and promoting mobility. A simplified remuneration structure could facilitate the management of personnel expenses. The recognition of professional performance in career advancement and training opportunities can provide incentives for the continuous professional development of public servants.

The following parts of this chapter go deeper into each of the areas of analysis described above.

Designing the career system for a modern and agile public sector

The ‘career system’ in Brazil is the backbone of the public service. This means that developing a fit-for-purpose public service in Brazil is difficult without identifying and addressing the underlying the challenges presented by the career system.

The Brazilian career system is comprised of 117 careers (carreiras) and 43 ‘groups of jobs’ (Plano de cargos) with 87% of Brazilian public servants belonging to one of these careers. These careers and groups of jobs are narrowly defined occupational or professional job categories that are often attached to a specific entity. Many careers contain the same functions and job types, but for different entities. There is duplication and overlap among many careers and some careers no longer meet the needs of the public service. However, these types of careers cannot be abolished (‘extinguished’) as long as there are still serving public servants in that career. Overall, this results in a high degree of rigidity, fragmentation and inequality.

In recent decades, many OECD countries have analysed the set-up of their public administration and restructured job categories and career paths to better meet the needs of a modern public service. In general, public administrations restructure their job classification systems to reduce transaction costs by dealing (as far as possible) with collectives rather than individuals, meaning that they tend to structure the workforce into distinct categories. This may be done according to occupational grouping, i.e. the job performed, or professional corps (the profession to which an employee belongs). The most efficient approach is to ensure that common categories are used to the largest extent possible across as many organisations as possible. This simplifies the management of large workforces by applying common employment conditions and arrangements for as many employees as possible.

Efforts to increase flexibility in OECD countries have led to the creation of broader occupational groups and their transversal application across as many organisations within the public service as possible. This means that skills and competences are defined in a way that allows public servants to move more easily across occupational groups and organisations, strengthening flexibility. Examples of changes made to pay and grading systems in various countries include the replacement of incremental pay scales by broad salary bands, restructuring along the lines of job families, and the rationalisation of job classification systems.

In Brazil, there are no job classification standards or overarching competency frameworks for the public service. The employment conditions, including salary amounts and structures, differ significantly as each career negotiates specific changes to its legal statutes, often directly with Congress. This has led to a high degree of fragmentation and internal competition between careers regarding employment conditions.

Each career is defined in its own law. Therefore, this inflexibility is exacerbated by the fact that any new careers or changes to existing careers have to be passed by Congress. As a result, equipping the public service for the future by including new skills and capacities is a complex and long process, as is making any reforms or changes to existing careers. To address this, the SGP has been requiring entities to complete any request for the creation of a new career with an assessment how the new career aligns with the public service digitalisation agenda. This is a first step towards including new skillsets, although it does not help to reduce the overall number of careers.

The SGP has worked to exercise stronger control over the creation of new careers by routinely verifying if requests for new careers could be either used as an opportunity for merging already existing careers or creating more transversal careers (i.e. careers that exist in multiple entities, thereby standardising employment conditions). As a result, no new careers have been established in recent years. For example, when creating the National Nuclear Safety Authority in 2021, instead of creating a new specific career for the authority, an already existing career was expanded to be employed in this authority.

Making deep changes to the career system requires significant legal and constitutional reform which is difficult to accomplish in the short to medium term as this will depend on political consensus. However, there are opportunities for more short- and medium-term steps which do not depend on legal reforms.

To systematise the creation of new careers, the SGP could build on the guidelines for creating new careers proposed. \ These guidelines could be used to build a common understanding for the efforts undertaken to reduce fragmentation and rigidity of the career system. Training HR units according to those guidelines, discussing why specific criteria have been put forward and systematically using the guidelines as a checklist before submitting requests for career creation to the SGP, would facilitate the work of the SGP.

Building on this, the SGP could develop a strategy for grouping and organising functions in the public service, including how to identify and classify common job categories and positions within functions to avoid duplication and reduce the overall number of careers. There is risk that positions break away from their parent function as has happened before. So this would need to be managed carefully. By analysing the careers and the needed skills and competencies as well as any future skills needs, a competency framework could support the development of those skills. This could also include a reflection on transversal skills to promote flexibility of the workforce.

Promoting mobility can contribute to higher professionalisation and resilience of the public service. In Brazil, only a few careers are designed transversally – i.e. with posts in multiple ministries and agencies, for example the career of Specialist in Public Policy and Government Management (EPPGG). The only possibility to enter a career is through a competitive entry exam for the specific career enabling the hiring of public servants at the lowest grade of the career. This means that the career system is rather rigid and inflexible to anticipate or react to short-term needs as public servants cannot be assigned, permanently or temporarily, across careers. Mobility opportunities are limited as only moves within the career are possible and depend on senior level public servants providing these opportunities.

Underlining and valuing transversal skills can be a way to build a more flexible workforce that can respond to short-term needs. Mobility can foster learning and exchange of information as well as promoting co-ordination on cross-cutting priorities which was identified as a challenge in the Brazilian public sector in the OECD Centre of Government Review of Brazil report (OECD, 2022[4]). However, in Brazil, the skills and qualifications set out for careers do not consider transversal skills as a benefit given that careers are usually attached to a specific entity.

To promote a more flexible public service that values transversality, Brazil could prioritise new careers that are organised according to functions, span across entities and define transversal skills and attributes. Brazil should explore lower entry criteria for public servants to other careers as well as being able to join careers at higher career levels. Further efforts could be also invested in the mobility programme set out by the SGP in line with Ordinance Nº 282, of July 24, 2020. It is an encouraging step towards more mobility, however, it could be further promoted and scaled up throughout the public sector for additional entities to take advantage. The talent bank already in place could help to provide a platform for specific areas and in-demand skills by building a specific stream searching for those skills, e.g. innovation. Lastly, guidance could be offered to public servants, managers, and entities. Apart from general guidance, this could include for example, succession planning checklists, transfer checklists, onboarding sessions, risk assessment (for conflict of interest), and performance management guidance.

Regarding career advancement in the Brazilian public sector, the only form of progression possible in most careers is movement up the salary scale based on seniority or a combination of seniority and performance.) Depending on the career, the top of the scale may be reached in a relatively short time. For example, public employees belonging to the internal revenue service can be at the top level in 11 years. In comparison, it may take 20 years for a public servant belonging to the Special Jobs Plan of the Ministry of Finance (now Ministry of Economy). Furthermore, career progression in Brazil is not commonly associated with a higher demand for technical or managerial skills.

Brazil could consider reforming career progression. First, for those careers that will be newly created, career progression criteria should go beyond seniority and take into account additional factors, such as performance. Brazil could begin with three levels within the career – junior, standard, and senior. Junior positions could be the common starting point and be oriented towards learning. The standard category would be the biggest, while the senior positions would be reserved for those who have developed a deep specialisation and/or take on supervisory functions. In this kind of structure, career progression would be based on demonstration of skills and effectiveness, for example through selection process for promotion to provide better incentive structures. In the long-term, Brazil could also consider initiating a discussion to provide opportunities for public servants to enter other careers at higher levels and in this way provide career progression.

The salary structure in the Brazilian public service at federal level is complex, as each career has its own salary scale and allowances, resulting in more than 700 salary grids. The base pay represents approximately 40% to 60% of public servants’ remuneration, with the rest made up of a myriad of differentiated benefits (OECD, 2010[5]). There is a large difference between basic salaries of comparable functions given the fragmentation of careers.

Ultimately, Brazil will eventually need to redesign the wage structure to align with future needs, rather than those of the past. This should include standardising and consolidating the various salary components (base pay, bonus payments, etc) to make pay more transparent and easier to manage. This may be a challenging and long-term undertaking given the interests involved. However, the SGP could take steps towards reducing the inequity of salaries among comparable functions. To provide pay equity, the SGP could establish an average basic salary for each function, based on a review of pay for all jobs that conduct similar work across careers. This basic salary per function could be taken as a standard basic salary for any new careers to be created. In order to mitigate the risk of a politicisation of salary-setting, an independent commission or service could help focus on the situation of each career.

Strengthening flexibility through the increased use of temporary contracts

Temporary hiring in the public service can help to meet short-term and immediate needs and requirements as well as recruiting specific in-demand skills. Not only, but especially in the event of crisis, the public service has to deliver results quickly and needs public employees who can fill in to cover unexpected workload increases, employee illness, leave and departure. At the same time, temporary employees will need training and onboarding, though the knowledge and skills will be lost once the temporary employees finish their contract.

In Brazil, the hiring of temporary staff is subject to restrictive conditions to meet demands of exceptional public interest. All cases qualifying for this are specifically defined through a prescriptive list of special circumstances in Law Nº 8 745 of 1993. This includes for example assistance in a state of emergency or researchers to collect data for the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. The restrictions on hiring temporary staff make the Brazilian public sector inflexible to react to any short-term needs. It also means that almost all the hiring that takes place has considerable budgetary implications, given that it implies long-term commitment. This is reflected by the relative low percentage of temporary staff in the public sector in Brazil. In July 2022, 5% of all public employees of the Brazilian federal public service were employed under the temporary regime, while 87% of the Brazilian public servants had permanent contracts.

Increasing the use of temporary recruitment in Brazil would require a legal reform to change the conditions under which temporary staff could be hired. This should be preceded by an extensive stakeholder discussion to reflect on who needs civil service protection, what are core state activities which can only be undertaken by permanent public servants, and under which conditions temporary hiring should be used. In addition, Brazil could explore measures to build surge capacity by setting up a pool of public servants which could be mobilised on short-term notice and increasing short-term mobility opportunities.

There is a risk that short-term hiring mechanisms are used to address long-term resourcing needs. A two-tiered system of permanent public servants and temporary public employees who are contracted long-term and performing the same jobs must be avoided. To manage the risk of circumventing conditions for temporary hiring, managers need guidance from HR offices as well as increased monitoring on the uses of temporary employees. Otherwise, this may adversely affect equality of access, merit and transparency.

Transparent terms and condition should be introduced for temporary hiring across the public sector to ensure transparency and consistent application. These could include:

Type of functions/positions and circumstances: Set out which type of functions may be filled by temporary employees – and define those core state activities which should be reserved for public servants. Exceptions under certain circumstances, such as activities of distinctly short-term nature could be included. Part of the reflection would be if those set out in the current law are the right ones or need to be amended.

Recruitment: This could be a simplified procedure which allows for a short timeframe to recruit.

Compensation: This should be broadly in line with civil service salaries for similar function, while allowing for some flexibility to be able to attract sought-after skills.

Term length: Clear limits should be set, including specific criteria and limitations for contract renewals to ensure that temporary hiring is not used as means to undercut the civil service regime by hiring temporary employees long-term. Part of the reflection on these elements would include if the term lengths currently defined are appropriate and effectively implemented or need to be amended.

Cooling-off periods: Defining a period after which a temporary employee can be hired again by the public sector. Currently, this is set at 24 months. The reflection process around these elements would need to deliberate if this period is effective or should be amended.

Working conditions and ethical standards: These should be largely in line with the those of permanent public servants.

Performance evaluations: These should be similar to those for public servants in comparable functions and be taken into account if contract renewals are possible.

Temporary hiring often allows for more simplified recruitment procedures which means lengthy staffing processes are avoided making the contracting quicker and more flexible. In Brazil, the hiring of permanent public servants takes on average one year. For temporary employees, it takes around 255 days as the same steps need to be taken throughout the hiring process as for permanent employees. Only in the cases of emergency, this time can be reduced by avoiding a selection process. This means that the opportunity for temporary hiring does not provide any advantages of flexibility.

In the discussion on a legal reform, a simplified recruitment process could be considered. While this should not reduce minimum standards of transparency, fairness and merit throughout the recruitment process, the hiring process should be considerably shortened to allow for flexibility. This should also include procedures to manage conflict of interests during the recruitment process and measures to avoid political influence. The recruitment could be decentralised with entities conducting the processes directly and allowing for simplified recruitment processes based only on a job interview. Similarly, the administrative procedures should be analysed for time efficiencies, such as reducing the time currently needed for authorising temporary hiring requests. However, in the case of simplified recruitment systems, care must be taken to ensure that limits to the use of temporary hiring are well designed and respected, to avoid the temporary scheme becoming a backdoor into core public service jobs.

Developing a mature performance management system

In an ever more constrained environment, public administrations seek to optimise processes, increase efficiency and achieve objectives. This means emphasising the performance of both organisations and individuals. In this context, performance management systems can link performance and HR decisions, allowing to monitor and evaluate the performance of public administrations and servants. Across the OECD, performance management systems have traditionally been characterised by elaborate monitoring systems, explicit goals, performance measures and targets. performance management systems are used as development tools that can develop talent, lead to a greater alignment between individual and organisational goals, and address under-performance.

Brazil’s federal administration uses performance management with many of the objectives listed above, however the systems could be simplified, reorganised and better aligned to improve their impact. Performance assessments amount to a rating attributed by the immediate supervisor. The average performance grade given throughout the Brazilian federal public service is 98/100, which is significantly high, and raises questions about the significance and value of the current system.

The career system in place in Brazil also affects performance assessment as responsibility for the detailed design of the performance management process rests with the career of origin and the entity responsible for it, based on guidelines from the SGP.

Good performance and underperformance are hard to identify in the Brazilian federal administration, as the inflated ratings given do not accurately reflect employees’ performance. In this context, performance rewards fail as a motivational tool, as they are perceived as automatic rewards given by default. This also means that underperformance cannot be properly addressed, no matter the incentives put in place to tackle this challenge.

Brazil should consider the introduction of a 3-point system where all public servants by default receive a score of 2. A score of 3 would be limited to a small number of proven high-performers, and a score of one reserved for those with clear performance problems that must be addressed. At the beginning, it could be prudent to limit the awards for high performance to a certain percentage.

To make this as effective as possible, Brazil would also need to harmonise the performance assessment systems in each career, so that managers are working with one common system across their workforce. This could be done either by standardising the timing and approach across all careers, and/or by shifting the responsibility for performance management design from the careers to the individual entities.

In Brazil, good performance amounts almost exclusively to performance bonuses, with performance-related pay representing a variable share of total compensation in each career. Performance-related pay can represent in some cases between 50% and 70% of total pay. This high percentage could stand to create a positive incentive if the system were able to detect and reward performance effectively. However in Brazil it appears to create a system in which public servants almost always receive their full performance bonus and perceive it to be part of their basic fixed salary. Considering its importance, such high bonuses risk creating a disincentive for managers to give public servants any lower ratings that would threaten their pay. This likely contributes to the explanation of why ratings of public servants’ performance are so high. In line with a simplification of the performance system to the three-point scale suggested above, the existing performance pay could be integrated into the regular civil service pay (or leave it for those who score 2), and reserve a smaller pay bonus and/or non-financial award only for those who score 3, to realign awards with truly exception performance.

An efficient performance management system can help to identify underperformance and set up appropriate mechanisms to address it, such as informal counselling, verbal or written warning, mandatory training or even dismissal of public servants.

Underperformance is rarely addressed in Brazil. Although Article 247 of the Federal Constitution states that underperformance can lead to dismissal, no appropriate mechanism is in place. Brazil could regulate dismissal for underperformance as a last resort. However, this should be accompanied by an escalation mechanism that addresses underperformance through 1) counselling and support; 2) training opportunities; 3) reassignment; and 4) dismissal as last resort.

At the organisational level, performance agreements give a measuring framework for outputs and goals. Entities should be able to define and identify a handful of goals, around which performance can be measured and strengthened. Goals should then be cascaded to specific units or departments, with managers translating organisational objectives into individual ones.

In Brazil, the People Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento de Pessoas, PDP) developed by each entity aims to align the development necessities with the strategy of each entity, through clear organisational objectives. Concretely, the People Development Plan focuses on the skills needed and the ways to develop them. In order to guide entities, the SGP is currently developing an initiative called ImpactaGOV to assist entities in developing People Development Plans.

As the SGP continues to support entities in developing organisational performance targets, efforts could be taken to define individual goals which link to the People Development Plan. This would mean, among others, reinforcing the capacity of managers to do so and structure objectives around entities, departments, and individuals.

Finally, considering senior managers’ task and special position in public organisations, their performance is often evaluated differently. More than two thirds of OECD countries have a performance-management regime for senior managers, based in a majority of cases on outcome, output, organisational management indicators, and performance-related pay. In Brazil, formalised performance assessment is not mandatory for senior level public servants. This can hurt the legitimacy of performance management systems in the eye of public servants, and creates an accountability concern in the eye of citizens. As new senior level public servant careers are being defined and a specialised leadership competency framework is implemented, it could be beneficial to develop efficient performance mechanisms targeting this group.

Assessing the Brazilian public employment and management system against the Public Service Leadership and Capability Recommendation

While the first section focused on the priority areas, the following sections provide an analysis of how the public employment and management system in Brazil aligns with the other principles of the Public Service Leadership and Capability Recommendation not addressed as part of the priority areas.

Pillar 1: Values-driven culture and leadership

Defining the values of the public service and promoting values-based decision-making

Common values in public administrations are the basis for a common understanding of what is desirable, not only as an outcome (societal well-being and progress) but also in how that outcome is achieved (fairness, transparency, accountability, etc.). Common public values create the basis for a culture of trust, which, in turn, permits greater flexibility and innovation in organisations and individuals while still ensuring compliance and integrity. Building a values-driven culture in the public service requires a clear understanding of what these common values are, and how they can be transmitted through effective values-based leadership.

Various pieces of primary and secondary legislation articulate the values of Brazil’s public institutions and set out standards- or codes of conduct- for public servants. The Office of the Comptroller General (Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU) has established a set of core public values in co-operation with the OECD following a large consultation in 2021. These include: engagement; integrity, impartiality; kindness; justice; professionalism; and vocation (Controladoria-Geral da União, n.d.[6]).

The SGP could display stronger leadership in promoting and communicating these common values. The SGP could mainstream these values throughout public employment policies. The Ministry of Economy should ensure it models public values such as merit, transparency, results-based management (accountability), and user-focus, especially in the recruitment, promotion, and assessment of public servants.

Building leadership capability in the public service

Capable leadership is required if public administrations are to keep pace with an increasingly complex, volatile, and uncertain world. It is senior level public servants (SLPS) who are responsible for transforming policies into action. In order to be successful in these endeavours however, SLPS need to have both the right skills and institutional support to deploy them.

Recent reforms in Brazil have aimed to clarify and consolidate the senior level public service regime in Brazil by introducing the CCE/FCE regime. The new regime carries over some recent requirements from a previous 2019 Executive Order to establish minimum criteria for selection/appointment. To develop a pipeline of SLPS, the SGP and ENAP jointly developed and recently piloted a programme called LIDERAGOV, whereby a group of selected public servants participated in a leadership development programme, after which they were put forward for CCE/FCE positions.

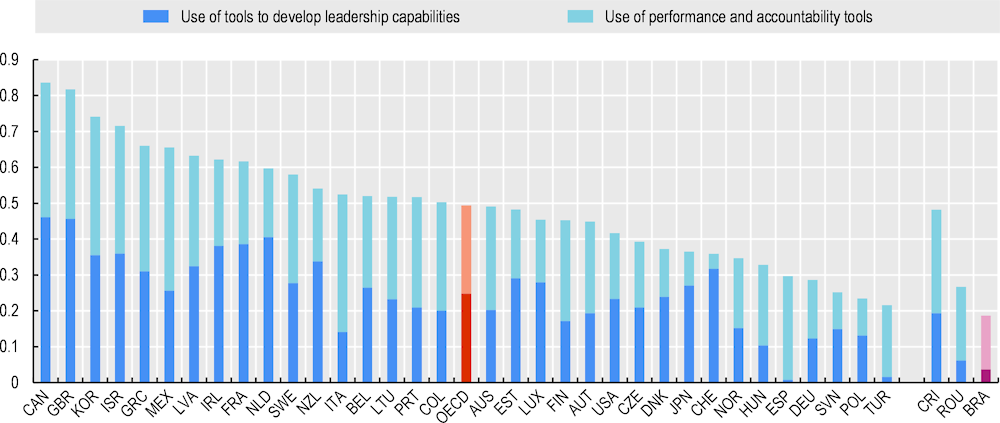

Despite these efforts, Brazil still has a long way to go towards developing a coherent senior level public service, accompanied by a broader strategy, and appropriate institutional support. Competitive selection processes remain the exception rather than the norm. Key dimensions of strengthening the senior level public service regime that still need to be developed include performance assessment criteria; learning and development; and open, transparent promotion opportunities. This is reflected in the OECD's pilot composite indicator on the management of the senior level public service.

Brazil should continue to strengthen the legal framework and institutional support for the senior level public service by building on the findings of the 2019 OECD report on innovation skills and leadership (OECD, 2019[7]) which recommended more specific minimum hiring criteria and expanding the use of competitive recruitment, among others. Furthermore, a dedicated team or unit to manage SLPS, monitor compliance with guidelines and set out a coherent learning and development strategy. Such a unit would help ensure the implementation of new policies, provide guidance and support to ministries, support strategic mobility of managers and leaders across departments, and serve to monitor progress over time.

Figure 4.4. Pilot index: Managing the senior level public service, 2020

Note: Data for Chile, Iceland and the Slovak Republic are not available. Data for the Slovak Republic are not available as the senior level public service is not a formalised group.

Source: OECD (2020), Survey on Public Service Leadership and Capability.

Ensure an inclusive and safe public service that reflects the diversity of the society it represents

An inclusive and representative workforce contributes is not only necessary to ensure fairness and equity, but also stands to improve efficiency and capability by broadening the range of skillsets and experience available in the workforce, boosting opportunities for innovation.

In Brazil, diversity in the public sector is not prioritised, particularly at management levels which where white men are greatly over-represented compared to the general population. In 2018, the share of women in the Brazilian public sector represented 44.8% (Fundação Escola Nacional de Administração Pública, 2018[8]). In senior management, only 16.8% are women and in middle management 35.1% of the positions are held by women, well below the OECD average of 37.1% for senior positions and 48.2% of middle management positions (OECD, 2021[2]). Furthermore, Brazil’s public service is predominantly white. Approximately 64% of all public servants are fully Caucasian, with this number growing to around 75% in management, compared to 43% of the Brazilian population reported white (IBGE, 2018[9]).

There are few policies in place to increase diversity, apart from quotas. Recourse mechanisms for employees who feel they have faced discrimination are limited, and those that do exist are reportedly not well known or actively promoted. In addition, data on the issue is, in many cases, not available. While information of ethnicity and gender is collected, other inclusions information seldom is. Further, the utilisation of data that exists does not currently appear to be widespread for purposes of measurement or monitoring.

To promote diversity and inclusion, more extensive policies should be introduced, including actively collecting data for monitoring and measurement. In addition, Brazil could conduct barrier analyses to address roadblocks to the public service for underrepresented groups. Evaluating attitudes about diversity within the administration could help to pinpoint areas of action. Lastly, creating recourse, watchdog or complaint mechanisms and processes would support employees in raising instances of discrimination.

Build a proactive and innovative public service that takes a long-term perspective in the design and implementation of policy and services

The public sector is facing increasingly complex and ever-changing challenges that demand innovation and forward-thinking mind sets. Initiatives to increase innovation in public sector contexts are often fuelled by the will and enthusiasm of committed public servants, working to change organisational cultures that emphasise stability and status quo.

In Brazil efforts have been made to promote innovation through several initiatives which aim to increase innovative processes and systems and the development of innovation competencies. These include LA-BORA!gov, a laboratory for innovation in people management, and pilot skill-development programmes within SGP. ENAP also acts as a hub and incubator for innovation-related projects.

Nevertheless, additional steps could be taken to consistently recognise and develop innovation as a value or core competency. Innovation is often viewed with high degrees of hesitancy due to repercussions of failure. The administration would benefit from a framework to help identify and foster the innovative skills and competencies needed in employees.

To incentivise innovation, Brazil should advance on the Recommendations of the OECD report ‘The Innovation System of the Public Service of Brazil’ (OECD, 2019[10]). Newly built competency frameworks could incorporate innovation skills, and embed them into HR management, career development, hiring and mobility strategies. Performance review systems could be used to realign incentives towards innovation. In addition, networks of innovators could be reinforced and rewarded to connect people working in innovative areas, thus creating support mechanisms, nurturing new ideas and working towards creating a culture of innovation.

Pillar 2: Skilled and effective public servants

Continuously identifying skills and competencies needed to transform political vision into services which deliver value to society

The complex and inter-connected nature of challenges facing governments means that they must be able to attract, recruit and develop many types of skills and competencies. Therefore, public administrations must take an in-depth look at what types and mix of skills and competencies are needed now and in the future.

In Brazil, strong efforts have been made to strengthen digitalisation of key services. However, entities struggle to identify and develop the needed competencies to support the digital agenda. One way to support this, is the mandatory development of the People Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento de Pessoas, PDP). Based on these assessments, the SGP, in co-ordination with ENAP, plans concrete capacity development training programmes to develop capacities across the public sector.

In addition, ENAP developed a classification of transversal competencies – a strong step toward mapping what skills and competencies are needed in the Brazilian public sector. This framework appears to be a first step at developing a common but flexible competency framework.

To reinforce the efforts taken to identify skills and competencies needed in the public service, the SGP could support entities further in their capacity to identify digital skills and transversal competencies related to the digital transformation of the public service. This could extend to skills on planning, co-ordination, and prioritisation to improve the effectiveness of the centre of government as recommended by the OECD Centre of Government Review (OECD, 2022[4]). The SGP could also facilitate discussions on changing skills requirements between entities and training providers such as ENAP. Lastly, the identified competencies should be integrated into people management processes, especially recruitment and learning and development.

Attract and retain employees with the skills and competencies required from the labour market

Public services increasingly require a wide variety of skill sets and professional backgrounds to address complex public challenges. This is why public services must be able to attract people with new and emerging skill-sets, as well as hard-to-recruit skill-sets (such as in the digital field) that are in demand by the private sector.

The Brazilian public sector is generally seen as an attractive employer but finds it hard to attract candidates with specific skill sets, in part due to the limitations of the career system as described above. At the same time, recruitment restrictions) have limited the ability of the Brazilian Federal Public Service to attract new talent. Furthermore, the distortions of the salary system mentioned previously can lead to a mismatch of supply and demand.

The SGP could deepen insights on what aspects of attractiveness appeal to specific groups and sought-after skills. It could also develop more proactive recruitment practices to compensate for the relative lack of new openings and ensure a better match between candidates and jobs on offer. This could include creating and systematising partnerships with universities to present career opportunities to students in areas of particular interest to the public service, communicating more strategically about public sector jobs opportunities (e.g. through social media), or supporting current employees to engage with a more diverse range of groups and backgrounds.

Recruit, select and promote candidates through transparent, open and merit-based processes, to guarantee fair and equal treatment

Recruitment and promotion processes should be fit for purpose to guarantee fair and equal treatment. Transparency is a core feature of recruitment processes in the Brazilian Federal public service. Recruitment competitions are advertised publicly and the list of successful candidates is published. While this transparency is welcome, it is important to make sure that the recruitment processes test relevant knowledge and skills as well. There is scope to identify ways to better assess skills (OECD, 2019[7]) in a systematic manner. This means making sure that candidates are tested through modern methods, and for competencies that align with job performance and long-term organisational goals.

Currently, most stages of the recruitment openings in Brazil are outsourced to private companies by the entity that is hiring. Outsourcing different aspects of the recruitment and selection process can enable entities to access more sophisticated ways of assessing candidates than are available in-house. However, the scale of outsourcing may also point to a lack of human resource skills and capability at entity level, which is an area to be explored further.

Brazil could analyse how new assessment methodologies could help to recruit candidates with future-oriented skills and competencies, while also better aligning authorisations for new recruitment competitions with strategic workforce planning needs across the Federal public service. Furthermore, the extent of the role, of private sector organisations in designing and running testing and assessment for public sector positions should be assessed and a strategic approach to their use developed.

Develop the necessary skills and competencies by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service

Learning and development is a core part of public sector capability. Learning is not just a tool or a product provided by human resource departments – it is an essential skill that public servants must acquire over the course of their careers.

While there are learning opportunities in the Brazilian Public Service, there is significant scope to take steps to move toward a more joined-up culture of learning. While ENAP has been supporting a culture of continual learning through re-framing its offer to entities in terms of solving business needs, there is a barrier to aligning the results of the People Development Plan at entity-level with the formats and content that ENAP proposes.

In Brazil, entities struggle to provide learning and development opportunities linked with long-term organisational goals. For example, participants to certain modules run by ENAP receive a certification, but when it comes to hiring or promotion decisions, that certification counts for relatively little. The burden is placed primarily on managers for encouraging learning and employees’ intrinsic motivation.

Mangers could be supported in their role of creating and incentivising a learning culture, for example as part of performance management. Entities could be supported by providing guidance on how to interlink the People Development Plan with the training offer by ENAP and how to integrate the learning outcomes at the organisational level.

Pillar 3: Responsive and adaptive employment systems

Clarify institutional responsibilities for people management

Within the public employment system, various institutions and entities have responsibilities for people management. Setting institutional responsibilities for designing, leading and implementing the elements for people management are fundamental to ensure the effectiveness of the public employment system.

In Brazil, the institutional responsibilities, mandate and capacities of its actors could be better aligned. The current structure is characterised by the SGP setting operational standards and relying on top-down regulations, while it does not have an operational mandate. Meanwhile, HR units are often overburdened with administrative tasks and have limited resources and capabilities for more strategic people management.

Conscious of this, the SGP is pushing towards a higher degree of automation of administrative tasks through the introduction of the electronic platform “Sou.gov”. It provides public employees their HR profile and opportunities to manage any administrative task through the platform, including searching for job opportunities. This facilitates the work of the HR units and has the potential to HRM staff to take on more strategic tasks.

To strengthen more strategic people management in the entities, the SGP in co-ordination with the HR units in the entities could assess which norms and regulations hinder flexibility and evaluate where specific responsibilities could be delegated to the HR units to allow for more innovative practices. The degree of delegation will have to be mirrored by an increase of capacities within the HR units. As HR professionals take on a new role, it could be considered to develop an HR career path building on the certification course to be offered in 2022 on ‘payroll’ and ‘workforce planning’.

Develop a long-term and strategic approach to people management

A long-term and strategic approach to people management in the public sector helps to get the right people in the right job or position at the right time. By assessing the skills needed and available in relation to strategic priorities and requirements, the public sector can better prepare its workforce for future needs.

The development of strategic approach to people management and availability of tools is rather limited in Brazil given the rigidity of the career system, with a focus on ensuring compliance with norms and regulations, controlling the size of organisations, limiting the number of new careers created and providing staff in policy priority areas. Meanwhile, a shared vision on public management could be further developed to advance a common understanding on the kind of public service envisioned.

This could be achieved by identifying the public employment goals set out in the Federal Development Strategy and breaking them further down into actionable items and what this means in practice for public employment and management. Evaluation efforts should also be introduced to measure progress on any goals set.

Implementing the strategic vision for the public service depends on the workforce and its capacities and skills to deliver services to the public. This makes it essential to plan workforce development. While the SGP has a good overview of the overall staff numbers and costs and can project the development of staff in the future, it could use these statistics in a more strategic manner. It currently mostly reacts to the entities’ indications of future hiring needs as new policy priorities arise. Conscious of this, the SGP has made some progress in recent years towards strategic workforce planning. In co-operation with the University of Brasilia Foundation, it has developed the Workforce Dimensioning Project. The project aims to develop and implement a reference model to support the definition of the ideal number of staff in each entity, identify needs in the workforce and anticipate change.

While this is a first step towards strategic workforce planning and developing a common understanding, the scope is very ambitious and may risk overcharging those responsible for implementation. It is therefore key to prioritise objectives and develop a scaled approach building on progress achieved. In addition to the approach at entity-level, the SGP could also work towards a workforce analysis of the current available skills and those needed in the future throughout entire public sector using the information provided by the Workforce Dimensioning Project where available.

Employees as partners in public service management issues

The effectiveness of the public service ultimately depends on the public servants providing those services. One key element to consider is the level of engagement of public employees. Enabling employee representation and entering into constructive social dialogue with them can be conducive to engaging public employees in public service management issues and involving them actively in improving the public service.

In order to provide opportunities for exchange, the SGP has set up a permanent institutional channel for exchange with unions through the Department of Labour Relations in the Public Service. This provides an opportunity for engaging in constructive dialogue with the unions. However, the discussions held are quite detached from the priorities developed within the SGP or the issues at entity-level with mostly unions raising issues they would like to address, but not vice-versa. There seems to be also no formal agreement on how issues debated are followed up on. In the public service, the right to strike is not formally regulated.

The SGP could strengthen the use of the institutional channel to build a constructive dialogue and proactively engage with the unions on changes and reforms. Brazil could also consider regulating the right to collective bargaining for employees of the public sector in order to enable more effective employee representation.

Beyond formal dialogue through unions, employee engagement may also be strengthened through specific tools within the entities. Employee engagement and perceptions should first be measured through government-wide employee surveys conducted at regular intervals (e.g. annually). The SGP has undertaken several efforts to measure employee engagement, for example through the OECD pilot module on employee engagement and a public sector wide survey in partnership with ‘Great Place To Work’, ENAP and the República Institute. While these are promising first steps towards establishing a baseline on employee engagement, no follow-up actions have been designed so far.

The SGP should develop an employee survey that aims to measure job engagement and its drivers, and conduct this survey at regular intervals to track changes over time. The SGP could then support leaders of entities to develop a number of actions to respond to survey results with a focus on improving scores and addressing challenges identified.

Lastly, channels for employees to report grievances and violations of integrity standards without fear of reprisals can be an effective measure to expose irregularities, mismanagement and corruption. In Brazil, various channels are available to public employees to report grievances or integrity violations. However, the establishment of these channels is only a first step. In order to make these effective, the public sector will need to foster a culture in which public officials feel confident in reporting misconduct and not fear retaliation for reporting.

Brazil could design awareness-raising campaigns on the reporting channels aimed at building trust and showcasing support for these channels from the leadership in a whole-of-government effort. In addition, the SGP could train leadership in building an open organisational culture and receiving and managing reports on misconduct in co-ordination with the CGU.

Guidelines for the creation or merging of new careers in the Brazilian public service

Building on the findings and recommendations of the OECD Public Service Leadership and Capability Review of Brazil, the OECD in co-ordination with the SGP proposes the following guidelines presenting criteria for the creation and merging of new careers in the Brazilian public service.

1. Simplification of the set of plans, careers and effective positions

The multiplicity of plans, careers and positions makes it difficult to manage the workforce, tends to increase personnel expenses and generates various asymmetries. It makes the public service inflexible by limiting opportunities for restructuring and reassigning personnel. It may also reduce the attractiveness of the civil service by proposing a restrictive career path with limited opportunities for mobility and variety. Reducing the overall numbers of careers and avoiding duplication of positions while also harmonising the main terms and conditions across careers and plans could help to overcome these issues, while allowing for the necessary diversity in the set of activities to be performed.

2. Expansion of the careers to multiple bodies instead of assigning careers to single bodies (autarchy model)

Currently, the underlying logic of the career system is that “each entity needs to have its career”. To simplify the career system and allow for more flexibility, careers would be structured according to the function performed, not according to the body or entity to which they are linked. This means that functions that are found in several bodies should be structured as a career with transversal attributions that can work in all those organisations that perform these functions. The career can be further broken down into specific job families, however, the main features related to career progression, key skills, and remuneration should remain comparable. The specifics of each organisation can be valued and managed in people management processes, such as selection, admission and development, without necessarily having a career of their own.

The existence of careers that compile functions common to different organisations brings several advantages for the public sector:

flexibility to manage the allocation of the workforce to meet needs that prove to be a priority over time

incentives for public servants seeking new professional challenges

wider learning and development opportunities for public servants

improved coherence across organisations and bursting of silos by creating a wider network of relationships between public servants, with the potential to support the implementation of new projects and programmes, in particular across organisations; among others.

A transversal model will ultimately contribute to improving the quality of public policies and public services delivered to citizens.

To strengthen flexibility of the public service, the transferability of positions, careers and plans needs to be a priority. This means new positions, careers and plans should be able to fit across entities and cluster where applicable several functions based on broad, transversal attributions. In this way, position, careers and plan are designed so they can be adapted to the needs of the public administration over time.

3. Personnel mobility mechanisms that ensure flexibility

The specific and narrow attributions for positions and careers which are enshrined in specific laws makes it difficult or prevents the mobility of servers. In addition, there is a culture of retaining people in the entities where they were initially allocated. To facilitate mobility, the public administration has some legal mobility mechanisms for the public servant to act in a horizontal, vertical, functional, internal, external, temporary or permanent dimension, among them: removal, redistribution, assignment, requisition and change of exercise for composition of workforce.

For the efficient and effective use of these personnel mobility mechanisms, it is necessary that new or altered plans and careers adopt criteria that encourage the application of these mechanisms, as well as provide for transversality elements, such as transversal skills and qualifications, that privilege a dynamic, agile, adaptive and flexible workforce, as required by the contemporary work context.

4. Promotion of greater equity between remunerations

Another characteristic of the multiplicity of plans and careers is the wide salary variation between positions with similar attributions within the scope of the federal Executive Power itself. It is suggested to seek a more equitable model while observing the necessary specificities of certain areas and activities. It is important that public servants when analysing the set of positions in the public administration, recognise their remuneration as fair. This means that equal work should be paid equally.

5. Simplification of the remuneration structure

Currently, there are a variety of bonuses, indemnities, incentives, remuneration, aid, additional and other instalments. This makes it difficult to properly manage personnel expenses, generates internal imbalances and distorts the original objective that motivated the creation of these specific remuneration components. The simplification of the remuneration structure, in addition to facilitating management, provides transparency to the servers themselves and to society and encourages isonomy in the remuneration policy.

6. Recognition of professional performance and development in career progression

Currently, most servants reach the highest career levels within a decade or two of service. This period does not correspond to the length of service required for retirement so the public servant can be “parked” for more than 20 years after reaching the top of his career until he retires. There are also difference between careers in how fast public servants can reach the top of the career. In addition, the current model of progression and promotion has shown to be a merely formal process, not based on the professional achievements of the public servant.

New or altered careers and plans need to aim for a harmonisation throughout the public service. They should provide public employees with opportunities for capacity development throughout their working life. Careers should also evaluate the progression and promotion rules and performance management tools, to create incentives for the continuous professional development of public servants to deliver results for society.

7. Prioritisation of strategic and complex activities

Hiring public servants is a long-term (financial) commitment by the public administration given the permanent nature of their contract. Considering the evolution of state action over time, it is necessary to design positions, careers and plans that not only correspond to current needs, but are also flexible to adapt to future needs. Meanwhile more ad-hoc, temporary functions may be better suited to be outsourced meaning the specific expertise can be hired for a determined time period.

In this context, priority for new careers should be given to designing positions more suited to the core state activities, concentrating efforts on final activities and giving space to the indirect contracting of services, whenever this solution proves to be more adequate to guarantee the focus of the direct action of the public administration.

References

[6] Controladoria-Geral da União (n.d.), Valores para Priorização, https://www.gov.br/cgu/pt-br/valores-do-servico-publico/priorizacao (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[8] Fundação Escola Nacional de Administração Pública (2018), Informe de Pessoal, https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/bitstream/1/3215/4/Informe%20de%20Pessoal%20-%20INFOGOV.pdf.

[9] IBGE (2018), Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua 2018, https://www.ibge.gov.br/en/statistics/social/population/26017-social-inequalities-due-to-color-or-race-in-brazil.html?=&t=resultados (accessed on 17 January 2022).

[4] OECD (2022), Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/33d996b2-en.

[2] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[1] OECD (2020), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/13130fbb-en.

[7] OECD (2019), Innovation Skills and Leadership in Brazil’s Public Sector: Towards a Senior Civil Service System, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ef660e75-en.

[3] OECD (2019), OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability.htm (accessed on 2 February 2022).

[10] OECD (2019), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Brazil: An Exploration of its Past, Present and Future Journey, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1b203de-en.

[5] OECD (2010), OECD Reviews of Human Resource Management in Government: Brazil 2010: Federal Government, OECD Reviews of Human Resource Management in Government, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264082229-en.