Wouter De Tavernier

Hervé Boulhol

Sandrine Cazes

Andrea Garnero

Wouter De Tavernier

Hervé Boulhol

Sandrine Cazes

Andrea Garnero

This chapter provides an overview of the work environment and of collective bargaining in long-term care. It shows that long-term care workers have somewhat shorter tenures than other employees. It reveals that the quality of the working environment in long-term care is rather poor, as the work is both physically and mentally arduous, often takes place at burdensome times, and that training opportunities and enforcement of labour regulations are limited for some groups of long-term care workers, in particular personal care workers providing home care. Finally, the chapter analyses collective bargaining in long-term care, revealing that in several countries workers’ representatives in the long-term care sector are not strong enough to negotiate tangible improvements in wages and working conditions.

Whether people want to work in a specific sector or occupation not only depends on the wages they are paid, but also on other working conditions. In addition to earnings levels analysed in Chapter 2, the OECD job quality framework includes the quality of the working environment and labour market security (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[1]). The quality of the working environment depends on a range of factors affecting the worker’s health and well-being including, among others, arduousness of work, working-time arrangements, and opportunities for adult learning. The economic uncertainty resulting from the risk of job loss, for instance in case of employment on fixed-term contracts, can be a reason for workers to look for another job.

Collective bargaining provides an important tool for workers and employers to improve job quality, including working conditions and the working environment. The European Commission presented the European Care Strategy in 2022, in which it stressed the essential role of collective bargaining to improve working conditions, wages and training opportunities for LTC workers (European Commission, 2022[2]). While workers need bargaining power to push for improvements in job quality, the LTC sector may be a difficult one to unionise. This is because many LTC workers work alone in people’s homes and because the share of immigrants working in the sector, who are less likely to be unionised (Gorodzeisky and Richards, 2013[3]; Kranendonk and de Beer, 2016[4]), is high in some countries (Chapter 4).

When data are available, indicators compare the LTC sector with both the overall economy and the healthcare sector. On the one hand, the healthcare sector is a good reference point to assess the job quality of LTC workers as it is the other major sector employing nurses and personal care workers. On the other hand, the much larger share of personal care workers in the LTC sector and reciprocally the larger share of nurses in the healthcare sector limit the full relevance of the comparison.

While in principle this report focuses on formal LTC work, most statistics in this chapter are based on survey data of people who reported to be in paid employment. The data may therefore include people performing undeclared work as their primary occupation to the extent that they are willing to say so when surveyed. The inclusion of undeclared LTC work may affect the findings in this chapter as undeclared LTC workers are more likely to face a poorer working environment and lower labour market security (Casanova, Lamura and Principi, 2017[5]). The issue of informal employment is briefly touched upon explicitly in the part on enforcement of labour regulations as some countries have implemented exceptions to labour regulations in order to formalise previously undeclared LTC work.

This chapter first sets the scene by presenting data on tenure, retention and labour market security of LTC workers. It then explores core aspects of the working environment. The final section analyses collective bargaining in the LTC sector and presents some international good practices with the aim of improving job quality of LTC workers.

LTC workers face very difficult working conditions. Physical and psychological arduousness as well as burdensome working times, such as night and week-end shifts, are part of the main drawbacks of the working environment in LTC. As a result, nurses and personal care workers are more often absent from work than other employees due to work-related health issues.

About three‑quarters of nurses and personal care workers are exposed to risks to their physical health, compared to 59% of all employees. The primary health risks care workers are exposed to are lifting people and providing care while being bent over, resulting in musculoskeletal problems. Abuse from care recipients and exposure to infectious diseases such as COVID‑19 may also be important risk factors.

About two‑thirds of nurses and personal care workers are exposed to risks to their mental health, compared to 43% of all employees. The primary mental health risks care workers are exposed to are a high workload and time pressure, and difficult care recipients.

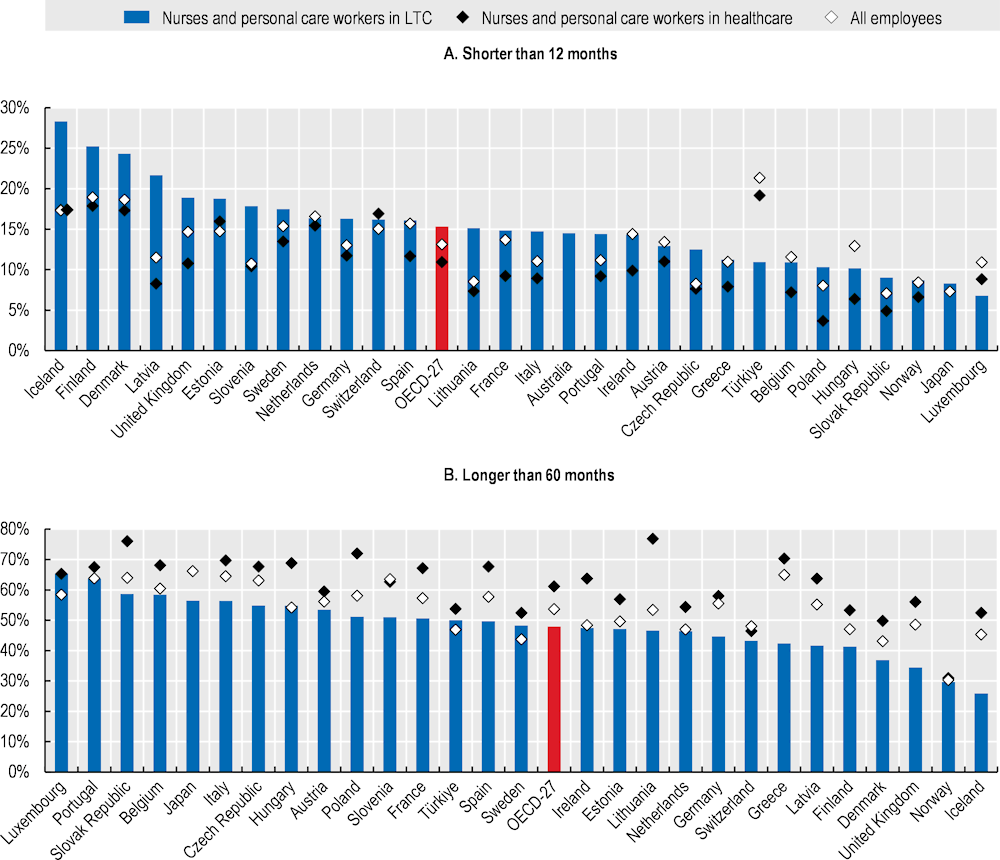

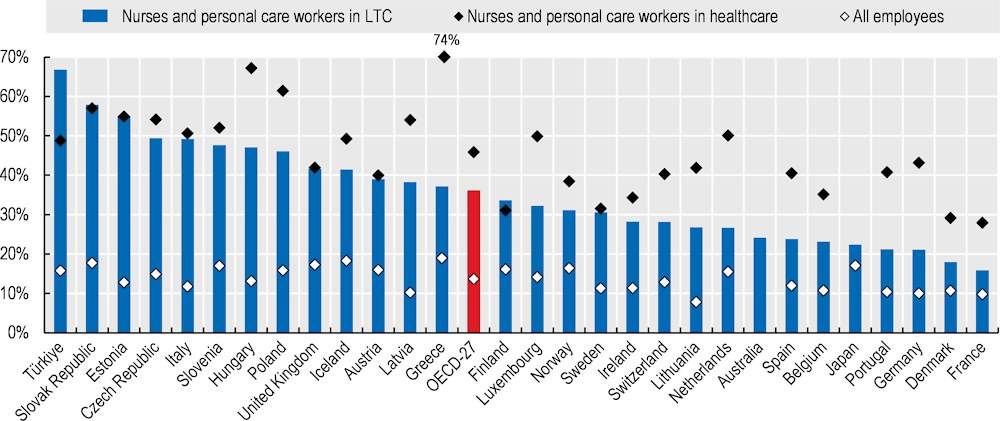

Nurses and personal care workers in the LTC sector have somewhat shorter tenures than workers in general, and much shorter tenures than nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector on average. For example, in the OECD on average, tenure is longer than 60 months for 48% of LTC workers, compared to 54% for all employees and 61% of nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector.

The share of LTC workers with fixed-term contracts is similar to that of other employees (12% vs 11%), but much higher than nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector (8%) on average in the OECD. Among workers on fixed-term contracts, a bigger share of surveyed workers report not wanting a permanent job in the LTC sector compared with all employees.

Part-time work is more common among LTC workers than among both healthcare workers and all employees. On average across the OECD, 32% of LTC workers are employed on a part-time basis, compared to 18% of all employees and 24% of nurses and personal care workers in healthcare. The difference in part-time incidence is especially large when the analysis is restricted to men. It is puzzling that even in some countries reporting a shortage of care workers, some LTC workers working part-time want to work more hours but cannot find a full-time job. Possible explanations include mismatches both geographical and between the times when people would be available to work extra hours and the times when care workers are most needed.

Participation in education and training is as common among LTC workers as in the general workforce, with 17% having received education or training in the four weeks prior to being surveyed, slightly below the share for nurses and personal care workers in healthcare, at 21%. Yet, there is a need for more education and training of LTC workers in some specific areas, in particular for those providing home care.

In most OECD countries, collective bargaining coverage of LTC workers employed in the formal sector tends to mirror the national average, but collective bargaining coverage of workers on paper is not sufficient to ensure good working conditions. In several countries, workers’ representatives in the LTC sector are not strong enough to negotiate tangible improvements in wages and working conditions; and even when they are, compliance is not guaranteed. Furthermore, several categories of LTC workers are underrepresented as they fall outside the scope of existing collective agreements because they work undeclared or as self-employed (including sometimes false self-employment).

There are local and national examples showing that collective bargaining and, more generally, social dialogue can help improve the working conditions, and wages in particular, of LTC workers. Whether to limit wage inequality or enhance job quality and workplace adaptation to the use of new technologies, collective bargaining and social dialogue remain unique tools enabling governments and social partners to find tailored and fair solutions, also in the LTC sector.

High turnover can be a sign of low job quality and a dissatisfied workforce. Insecure contracts contribute to poor job quality and can be a reason for people to leave an occupation if more economically secure jobs are available elsewhere in the economy. In turn, high turnover can undermine the quality of services provided as experienced staff leave the organisation and are replaced by staff requiring time to get acquainted with clients’ needs. Tenure and staff turnover are included as measures to assess LTC quality in several countries (OECD/European Union, 2013[6]). Moreover, to the extent that turnover leads to people leaving the sector, it entails a loss of experienced staff and requires training of new LTC workers (OECD, 2020[7]). This section first presents some figures on tenure and retention of LTC workers, and subsequently discusses labour market security in the LTC sector.

The frequency of short tenure among LTC workers is slightly higher than among other employees. On average in the OECD, tenure is shorter than 12 months for 15% of LTC workers, compared to 11% of nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector and 13% for all employees (Figure 3.1, Panel A). This is an example where differences between LTC and healthcare workers may partially be the consequence of their different composition: on average across the OECD, the LTC sector employs over 3 times as many personal care workers as nurses, whereas the exact opposite is the case for the healthcare sector.1

Around one‑quarter LTC workers have a tenure of less than 12 months in Denmark, Finland and Iceland, whereas it is about one‑tenth or less in Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Luxembourg Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Türkiye. A higher share of LTC workers have particularly short tenures compared with employees in general in the Baltic and the Nordic countries (except Sweden) as well as in Slovenia.

On average across countries, about half of LTC workers have tenure exceeding 60 months, slightly less than the share for all employees and well below the share among nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector (Panel B). About two‑thirds of LTC workers in Luxembourg and Portugal have tenures exceeding 60 months, while long tenures are least common in Denmark, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom, where the share is below 40%.

LTC workers are not more likely to be looking for another job than employees in general: across the OECD, 4% of LTC workers were looking for another job in the period 2019‑20, the same share as for all employees and 1 percentage point higher than for nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector.2 The above number for LTC workers is lower than some more alarming turnover intention rates in the LTC workforce reported in other studies. Gaudenz et al. (2019[8]) for instance report that more than half of care staff in Swiss nursing homes intend to leave their jobs. However, searching for another job is a much more accurate predictor of turnover of LTC workers than vaguer statements such as thinking about leaving or expecting to leave one’s job in the future (Castle et al., 2007[9]).

The turnover of LTC workers increases when the quality of the working environment is poor. The working environment of nurses and personal care workers in LTC is particularly poor in terms of workload and working times as discussed in greater detail below: their turnover has been linked to high workload and work-related stress due to staffing shortages (Halter et al., 2017[10]; Hayes et al., 2006[11]) and non-standard or unstable work schedules (Butler et al., 2014[12]; Castle et al., 2007[9]). One study comparing turnover intentions of nurses in nursing homes to those in home care finds that turnover intentions of the former were slightly higher as a result of somewhat higher time pressure and occurrence of social conflict (Rahnfeld et al., 2016[13]). Some other aspects of the working environment of nurses and personal care workers can mitigate high turnover rates, in particular support from colleagues, autonomy, and participative, motivational and supportive leadership (Butler et al., 2014[12]; Halter et al., 2017[10]; Hayes et al., 2006[11]; Radford, Shacklock and Bradley, 2015[14]). In addition, LTC workers’ attachment to care recipients and good care quality reduce the odds of LTC workers leaving the organisation (Castle et al., 2007[9]; Rajamohan, Porock and Chang, 2019[15]; Treuren and Frankish, 2014[16]).

Note: The OECD average refers to the average of countries for which data on all three data series are available, and does therefore not include Australia and Japan. Due to the number of LTC workers with tenures shorter than 12 months being below the number required to report exact numbers, data for the period 2020‑21 are used for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; 2019‑21 for Greece and Luxembourg; and 2018‑21 for Poland. Data only refer to 2016 for Australia, to 2020 for Türkiye, and to 2019 for the United Kingdom. For Japan, data refer to 2020 for LTC workers and to 2021 for all employees.

Source: EU-LFS; Australian data based on Mavromaras et al. (2017[17]), The Aged Care Workforce, 2016, https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/Workforce/The-Aged-Care-Workforce-2016.pdf, Japanese data from Care Work Foundation (2021[18]), 令和3年度介護労働実態調査: 介護労働者の就業実態と就業意識調査 結果報告書 [Survey on Long-Term Care Workers: Report on Employment Status and Employment Attitude Survey of Care Workers], http://www.kaigo-centre.or.jp/report/2022r01_chousa_01.html, and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2021[19]), 賃金構造基本統計調査 [Basic Survey on Wage Structure], https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/chinginkouzou.html.

Labour market security refers to the risk of job loss and the economic consequences for the worker. People employed on fixed-term contracts, and a fortiori those employed through temporary employment agencies, face a number of disadvantages in the labour market (OECD, 2017[20]; OECD, 2014[21]). They are less likely to be unionised and their voices are less likely to be taken into account within the organisation (see the last section of this Chapter). Employers are less likely to invest in the education or training of these employees. Overall, within similar occupations job quality is lower for workers on temporary contracts: beyond higher labour market insecurity and reduced education and training opportunities, they receive lower earnings on average, have less autonomy in their work and experience lower levels of support from their peers, while being more exposed to health risks.

There is a wide variation between countries in the use of fixed-term contracts in LTC, although this largely follows differences in the use of such contracts in the entire economy. In the OECD on average, LTC workers are about as likely to be employed on fixed-term contracts as employees in general, respectively 12% and 11%, while this is the case for only 8% of nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector (Figure 3.2). Over one‑quarter of LTC workers are on fixed-term contracts in Japan, Poland, Spain and Sweden, whereas this applies to less than 5% of the LTC workforce in Austria, the Baltic states, Ireland and Türkiye. LTC workers are much more likely to be hired on fixed-term contracts than employees in general in Denmark, Greece, Japan, Poland and Sweden, whereas the opposite is the case in Austria, Ireland, the Netherlands and Türkiye.

Note: The OECD average refers to the average of countries for which data on all three data series are available, and does therefore not include Japan. Data are not shown for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as the share of LTC workers concerned is below the number required to report exact numbers, although the exact share is used for the calculation of the OECD average. Extended reference periods for LTC workers are used for the following countries: data for the period 2017‑21 are used for Ireland; 2016‑21 for Estonia and Lithuania; and 2014‑21 for Latvia. Data only refer to 2020 for Japan and Türkiye, and to 2019 for the United Kingdom.

Source: EU-LFS; Japanese data from Care Work Foundation (2021[18]), 令和3年度介護労働実態調査: 介護労働者の就業実態と就業意識調査 結果報告書 [Survey on Long-Term Care Workers: Report on Employment Status and Employment Attitude Survey of Care Workers], http://www.kaigo-center.or.jp/report/2022r01_chousa_01.html and OECD (2022[22]), “Temporary employment” (indicator), https://www.doi.org/10.1787/75589b8a-en (accessed on 11 October 2022).

About 40% of LTC workers on fixed-term contracts indicate that they could not find a permanent job, which is somewhat lower than in the overall economy (Table 3.1). In addition, a higher share of LTC workers on fixed-term contracts state that they do not want a permanent job, at 17% compared to 10% among all employees. Overall, this still means that a large part of LTC workers on fixed-term contracts work on these contracts involuntarily, even though this is less of an issue in LTC than in the overall economy. LTC workers do not differ much from employees in general in terms of being on a fixed-term contract because that was the only option available for the job, for training purposes or for a probation period.

Share of employees on fixed-term contracts in OECD‑26 countries by reason for working on a fixed-term contract, 2020‑21

|

LTC workers |

All employees |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Could not find a permanent job |

39% |

44% |

|

This job is only available with a fixed-term contract |

11% |

10% |

|

Did not want a permanent job |

17% |

10% |

|

Apprentice, intern, trainee or other training programme |

17% |

15% |

|

Fixed-term probationary contract |

8% |

9% |

Note: Due to the number of LTC workers on temporary contracts being below the number required to report exact numbers in some countries, data for 2020 and 2021 are merged. The United Kingdom is not included as EU-LFS contains no data for the country for the years 2020 and 2021.

Source: EU-LFS.

The OECD work on the quality of the working environment is rooted in the job demands-resources model (OECD, 2017[20]).3

Job demands are aspects of a job that require sustained physical or psychological effort. Job demands typical in LTC include for instance lifting people, working with people with dementia and night work.

Job resources refer to aspects of a job that can help employees achieve work goals and stimulate their career development – and thus improve well-being. This includes among others skill variety, autonomy, opportunities to learn and support from peers.

At its core, the model contends that high job demands reduce workers’ physical and mental well-being, whereas job resources help workers meet demands at a lower cost to their well-being. The model was initially used to explain burnout, which entails emotional exhaustion and disengagement of the worker, but is now also extensively used for other outcomes such as worker health, absenteeism and job turnover.

In relation to LTC, the job demands-resources model has been used not only to analyse job quality but also to explain care‑related outcomes including quality, person-centredness and rationing of care,4 and safety, neglect and abuse of care recipients (Andela, Truchot and Huguenotte, 2021[23]; Ruotsalainen, Jantunen and Sinervo, 2020[24]; Seljemo, Viksveen and Ree, 2020[25]).

The OECD assesses job characteristics along six dimensions, identifying both job demands and job resources in each of these dimensions:5

The physical and social environment of work includes job demands such as physical demands and risk factors, and support from peers as a resource.

Job tasks include job demands such as work intensity and emotional demands, and autonomy as a resource.

Organisational characteristics include job resources such as good managerial practices, workplace participation and performance feedback.

Working-time arrangements include unsocial work schedules as a job demand, and flexibility of working hours as a resource.

Job prospects include perceptions of job insecurity as a job demand, and training and opportunities for career advancement as resources.

Intrinsic aspects of the job include opportunities for self-realisation and intrinsic rewards as job resources.

Studies have generally found evidence of the job demands-resources model applying to nurses and personal care workers across countries.6 Key job demands in these occupations include work overload, for instance linked to staffing shortages; working-time arrangements that infringe on workers’ work-life balance; and, emotional demands stemming among others from dealing with aggressive care recipients or with their death and functional decline. Some job demands and resources are especially important for nurses and personal care workers in the LTC sector compared to those in the hospital sector.7 For instance, nurses in LTC have lower workloads but higher levels of emotional exhaustion (Sarti, 2014[26]). Resources for LTC workers include a supportive environment, participatory leadership and recognition (Chapter 4). Specific resources help deal with specific impacts of job demands. For home‑care nurses, for instance, task autonomy reduces the effect of high workloads on burnout, whereas receiving support from the people around you helps buffer the impact of emotional demands (Vander Elst et al., 2016[27]).

This section explores core aspects of the quality of the working environment of LTC workers. First, it analyses the arduousness of LTC work, examining both physically and psychologically arduous aspects of the work. Then, working-time arrangements in LTC are examined. After briefly looking into opportunities for adult learning, enforcement of labour regulations in LTC work is discussed.

LTC work can be very taxing, both physically and mentally. Working in LTC has a stronger negative impact on health than working in other occupations (Rapp, Ronchetti and Sicsic, 2021[28]). LTC work requires physical abilities, in particular trunk and static strength (Chapter 2). Strength is necessary for lifting care recipients, which is an important risk factor for physical health (Dellve, Lagerström and Hagberg, 2003[29]). LTC-specific psychological health risks include exposure to aggression and abuse from care recipients and their families (Vasconcelos et al., 2016[30]) as well as emotional strain. While empathy is an important aspect of LTC work, it becomes a risk factor for stress and burnout. The emotional bond that can develop between the care recipient and the LTC worker due to the long periods over which they interact with one another (Khamisa, Peltzer and Oldenburg, 2013[31]) may result in the latter absorbing the care recipient’s emotional distress (Hunt, Denieffe and Gooney, 2017[32]; Singh et al., 2020[33]). The COVID‑19 pandemic exacerbated LTC workers’ exposure to physical and mental health risks due to shortages of protective gear such as face masks in the LTC sector and increasing workloads (Pelling, 2021[34]).

The arduousness of LTC occupations has been recognised in some countries through the access to social benefit entitlements. French nurse aids and care assistants employed in the public sector are allowed to retire five years earlier due to being exposed to multiple health risks, as they are exposed to relational (e.g. regular interpersonal tensions), organisational (e.g. high work pace, shortage of human resources), physical (e.g. straining posture), chemical and biological health risks (Anses, 2021[35]). In 2021, the social partners of the Dutch LTC sector agreed on the introduction of a scheme allowing LTC workers to retire up to three years earlier after a 45‑year career in the care sector, of which at least 20 years worked as a direct care provider. In Belgium, workers in the care sector have supplementary annual leave entitlements as of age 45 with the objective to facilitate working longer.

This sub-section provides an overview of absence from work and of the main risk factors and health problems that care workers face in terms of physical and mental health. The data in this section do not exclusively refer to LTC workers, but to all nurses and personal care workers in the sector of human health and social work activities collectively referred to in this sub-section as “care workers”, which hence also includes those working in healthcare (NACE sector Q).8

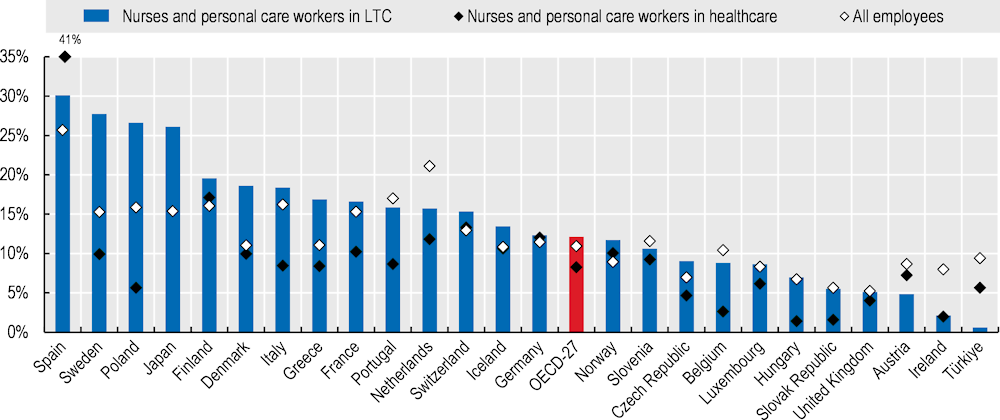

Consistent with higher exposure to health risks, care workers are more frequently absent from work than the overall employed population. In all OECD countries for which data are available, nurses and personal care workers are more absent, on average, due to a work-related health problem than all employees. On average, nurses and personal care workers were absent from work during 1.2 weeks over the last year as a result of a health problem that was either caused or exacerbated by their work, compared to 0.7 weeks for the average employee (Figure 3.3). For nurses and personal care workers, this ranges from over two weeks in Spain and Sweden to less than half a week in the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Ireland and Lithuania. COVID‑19 likely exacerbated the absence of LTC workers: in Canada, 71% of nursing homes experienced an increased absence of staff due to COVID‑19, compared to 56% of other residential care facilities for older people (Clarke, 2021[36]).

Note: “Nurses and personal care workers” includes people in occupations 222 (nursing and midwifery professionals), 322 (nursing and midwifery associate professionals) and 532 (personal care workers in health services) employed in NACE sector Q (human health and social work activities). Answer categories were transformed into weeks by assigning the value of the middle of the answer category (e.g. a person indicating to have been absent “At least one month but less than three months” is assumed to have been absent for two months). Periods of absence exceeding one year were topped off at one year.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS 2020 ad hoc module on accidents at work and other work-related health problems.

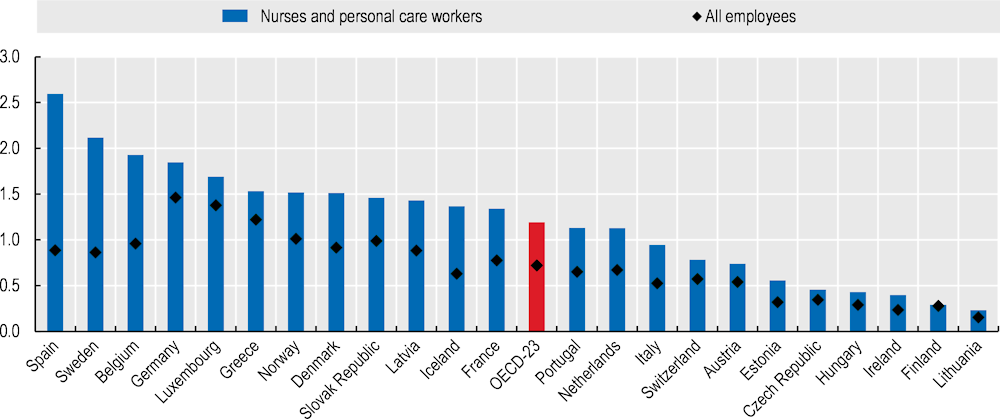

Nurses and personal care workers are much more exposed to physical health risks than other employees. Of all nurses and personal care workers employed in the broader sector of human health and social work activities in the OECD, 73% declare being exposed to some risk that can impact their physical health, compared to 59% of employees in general (Figure 3.4).

The primary risks to physical health of care workers are lifting people and providing care while being bent over, for instance to people lying in bed (OECD, 2020[7]). Handling heavy loads and holding tiring and painful positions are singled out as risk factors by respectively 28% and 18% of nurses and personal care workers (Figure 3.4). Increasing overweight and obesity among older people is a growing worry for LTC workers’ musculoskeletal health in some countries. By contrast, these percentages are 9% and 12%, respectively, for employees in general. Care workers do score lower than the average employee on all other specified risk factors, in particular on the requirement of strong visual concentration. However, 12% of care workers indicated that they face other risks to their physical health than the ones listed, compared to 3% of all employees. This may for instance include exposure to infectious diseases such as COVID‑19 or the risk of physical violence from care recipients and their families. Eurofound (2020[37]) reports that 12% of LTC workers have been exposed to physical violence during the month before being surveyed.

Note: The red bar indicates the total share of employees who are exposed to at least one physical health risk. The asterisks indicate the extent to which nurses and personal care workers differ significantly from all employees for each listed physical health risk (* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01). “Nurses and personal care workers” includes people in occupations 222 (nursing and midwifery professionals), 322 (nursing and midwifery associate professionals) and 532 (personal care workers in health services) employed in NACE sector Q (human health and social work activities).

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS 2020 ad hoc module on accidents at work and other work-related health problems.

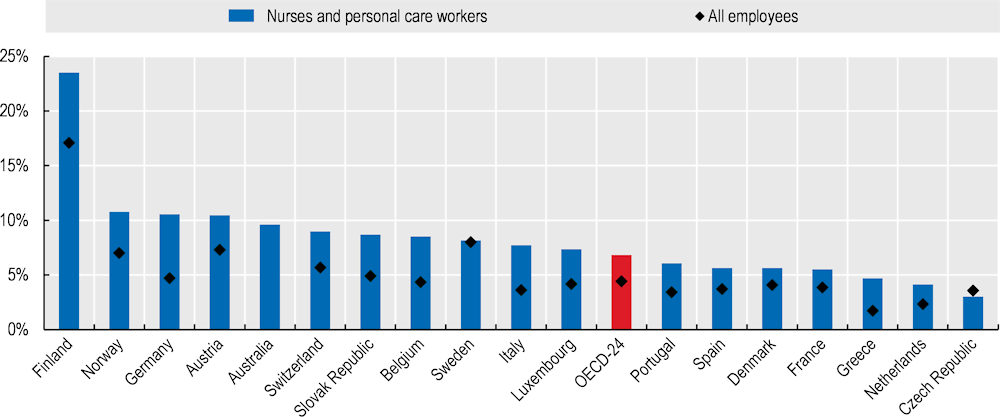

Nurses and personal care workers are more likely to have musculoskeletal problems either caused or exacerbated by working than the average employee. On average across 22 OECD countries for whom sufficient data are available in the EU-LFS dataset, 7% of nurses and personal care workers have a bone, joint or muscle problem as a result of work compared to 4% of all employees (Figure 3.5). In all countries except the Czech Republic and Sweden, care workers are more likely to report work-related musculoskeletal problems than the average employee. Finland is an absolute outlier, with 24% of care workers and 17% of employees reporting this type of health problem.9 Other countries where over 10% of nurses and personal care workers have work-related problems with their bones, joints or muscles are Austria, Germany and Norway.

Note: “Nurses and personal care workers” includes people in occupations 222 (nursing and midwifery professionals), 322 (nursing and midwifery associate professionals) and 532 (personal care workers in health services) employed in NACE sector Q (human health and social work activities). Data are not shown for Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia and Lithuania as the share of LTC workers concerned is below the number required to report exact numbers, although the exact share is used for the calculation of the OECD average. For Australia, the data refer to work-related fractures, chronic joint or muscle conditions, or sprain/strain. Data refer to 2016 for Australia.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS 2020 ad hoc module on accidents at work and other work-related health problems; Australian data based on Mavromaras et al. (2017[17]), The Aged Care Workforce, 2016, https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/Workforce/The-Aged-Care-Workforce-2016.pdf.

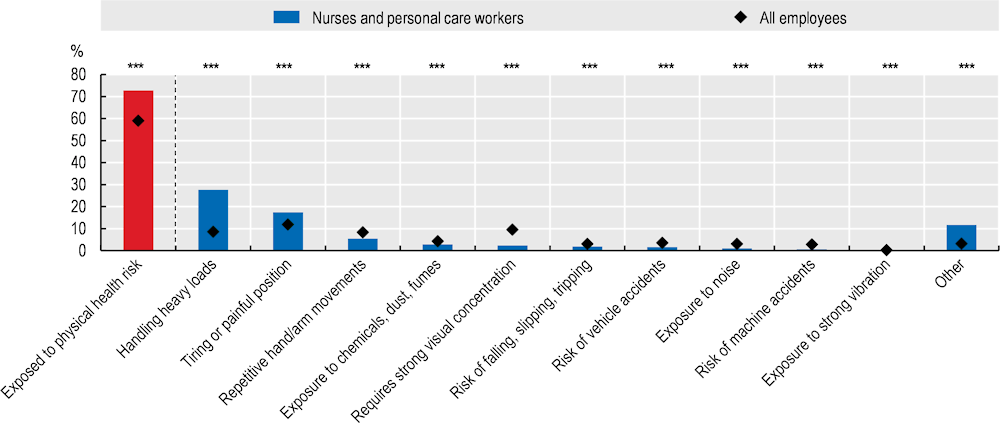

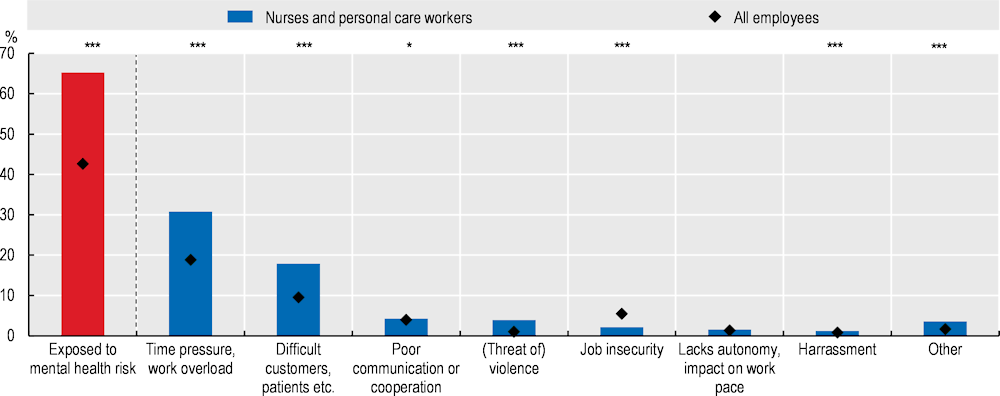

About two‑thirds of nurses and personal care workers report being exposed to mental health risks, much more than average employees at 43% (Figure 3.6). Workload and time pressure are the main source of mental health risk for 31% of nurses and personal care workers and 19% of employees in general. This feeling is often the result of high caseloads and administrative requirements leaving LTC workers frustrated about a lack of time to work with individual care recipients (OECD, 2020[7]). Work intensity is indeed higher in the LTC sector than it is in the overall economy (Eurofound, 2020[37]). Difficult customers or, in the case of care workers, patients and care recipients are a mental health risk for 18% of nurses and personal care workers and 10% of employees in general. While violence or the threat thereof was considered the main source of mental health risk by only 4% of nurses and personal care workers, the level was 4 times lower among employees, at 1%. At the same time, Eurofound reports that 26% of LTC workers have been exposed to verbal abuse, 11% declare to have been threatened and 8% to have been humiliated, bullied or harassed during the month before being surveyed (Eurofound, 2020[37]). Care workers are less likely than other employees to identify job insecurity as their main mental health risk, with respectively 2% and 5% reporting this to be a risk factor.

Note: The red bar indicates the total share of employees who are exposed to at least one mental health risk. The asterisks indicate the extent to which nurses and personal care workers differ significantly from all employees for each listed mental health risk (* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01). “Nurses and personal care workers” includes people in occupations 222 (nursing and midwifery professionals), 322 (nursing and midwifery associate professionals) and 532 (personal care workers in health services) employed in NACE sector Q (human health and social work activities).

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS 2020 ad hoc module on accidents at work and other work-related health problems.

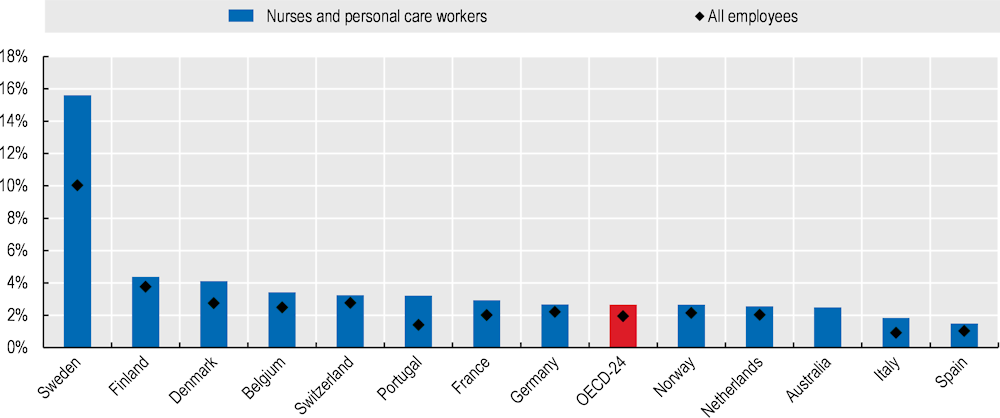

Nurses and personal care workers are slightly more likely to suffer from stress, depression or anxiety caused or worsened by work than employees in general. On average across the OECD countries analysed, 3% of care workers report suffering from stress, depression or anxiety, compared to 2% of employees (Figure 3.7). Sweden is an absolute outlier, with 16% of care workers and 10% of all employees reporting these mental health problems, although this may be the consequence of a questionnaire issue.10 In all other countries, the share remains below 5% for both employees in general and care workers specifically.

Note: “Nurses and personal care workers” includes people in occupations 222 (nursing and midwifery professionals), 322 (nursing and midwifery associate professionals) and 532 (personal care workers in health services) employed in NACE sector Q (human health and social work activities). Data are not shown for Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic as the share of LTC workers concerned is below the number required to report exact numbers, although the exact share is used for the calculation of the OECD average. Sweden’s position may be the consequence of a questionnaire issue.10 Data refer to 2016 for Australia.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU-LFS 2020 ad hoc module on accidents at work and other work-related health problems; Australian data based on Mavromaras et al. (2017[17]), The Aged Care Workforce, 2016, https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/Workforce/The-Aged-Care-Workforce-2016.pdf.

Long working hours, working at burdensome times and irregular work schedules are risk factors for physical and mental health, in particular when workers have little control over their working hours (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[1]). Non-standard working-time arrangements, such as night, weekend and holiday shifts, long shifts and overtime, are related to higher turnover intentions in nurses (Hayes et al., 2006[11]; Zeytinoglu et al., 2009[38]). In addition, part-time workers are somewhat disadvantaged in the labour market as they are less likely to be unionised, and as some managers may take working part-time as a signal of low career commitment. While part-time work has a number of disadvantages, in particular lower investment in education and training, limited career prospects and less autonomy, for some workers these disadvantages are partially compensated for by higher control over their working time and a better work-family balance (OECD, 2017[20]).

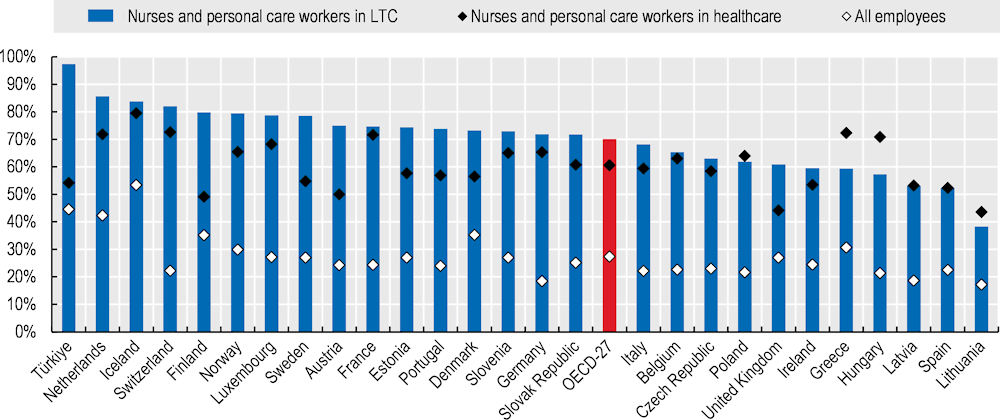

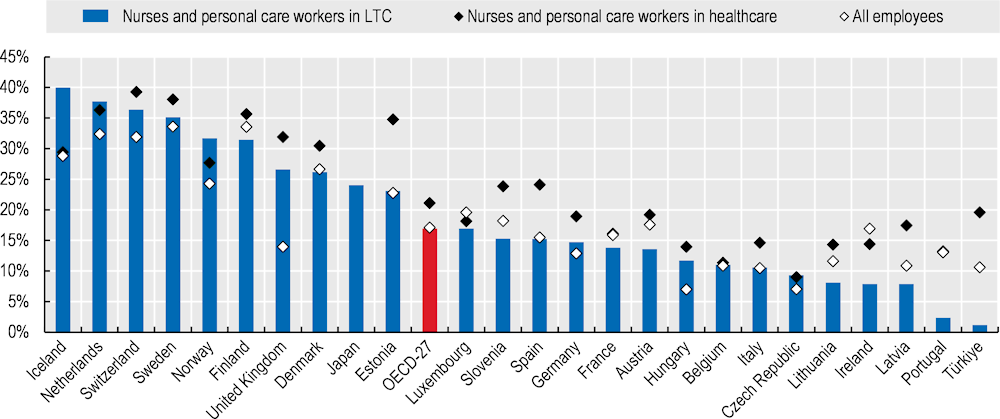

LTC workers are about 2.5 times as likely as the average employee to work at night. On average across the OECD, 36% of LTC workers sometimes or usually work at night, compared to only 14% of all employees (Figure 3.8). Yet, night work is less common for LTC workers than it is for nurses and personal care workers in the healthcare sector, 46% of whom sometimes or usually work at night. The share of LTC workers doing night work differs strongly across countries, ranging from 16% in France to 67% in Türkiye. This wide variety is in stark contrast to the share of all employees working at night, which fluctuates only between 8% in Lithuania and 19% in Greece. The high variation between countries in the prevalence of night work among LTC workers could among others be related to the extent to which LTC is provided by live‑in care workers who are available 24 hours per day, and how this is accounted for across countries. In Germany, for instance, a court ruled in 2021 that live‑in care workers who are available around the clock should also be paid at least at the minimum wage for the hours where they do not provide care but are standby (DW, 2021[39]), which may reduce the possibility for people to afford formal live‑in care. There is no assessment yet of the impact of the ruling on formal live‑in care provision.

Note: The OECD average refers to the average of countries for which data on all three data series are available, and does therefore not include Australia and Japan. Due to the number of LTC workers working at night being below the number required to report exact numbers in some countries, data for 2020 and 2021 are merged. Data only refer to 2016 for Australia, to 2020 for Japan and Türkiye, and to 2019 for the United Kingdom.

Source: EU-LFS; Australian data based on Mavromaras et al. (2017[17]), The Aged Care Workforce, 2016, https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/Workforce/The-Aged-Care-Workforce-2016.pdf; Japanese data from Care Work Foundation (2021[18]), 令和3年度介護労働実態調査: 介護労働者の就業実態と就業意識調査 結果報告書 [Survey on Long-Term Care Workers: Report on Employment Status and Employment Attitude Survey of Care Workers], http://www.kaigo-center.or.jp/report/2022r01_chousa_01.html and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2020[40]), 労働安全衛生調査(実態調査)[Occupational Health and Safety Survey (Fact-finding Survey)], https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/list46-50_an-ji.html.

Similarly, LTC workers are about 2.5 times as likely as the average employee to work on Sundays. Sundays, occasionally or usually, are part of the working schedules of 70% of LTC workers compared to 27% of employees and 61% of nurses and personal care workers in healthcare (Figure 3.9). LTC workers are more than three times as likely to work Sundays as employees in general in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Switzerland.11

Note: Due to the number of LTC workers working on Sundays being below the number required to report exact numbers in some countries, data for 2020 and 2021 are merged. Data only refer to 2020 for Australia and Türkiye and to 2019 for the United Kingdom.

Source: EU-LFS.

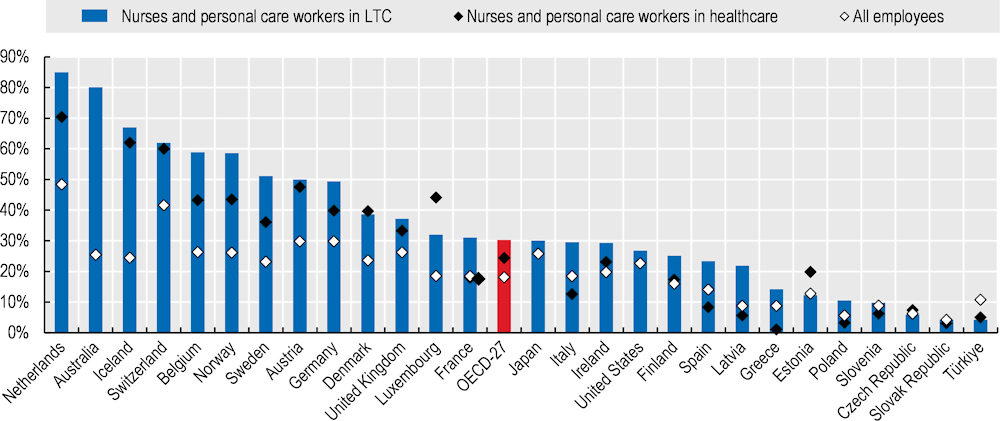

Part-time work is more common among LTC workers than it is in the total workforce. On average across the OECD, 32% of LTC workers are employed on a part-time basis, compared to 18% of employees and 24% of nurses and personal care workers in healthcare (Figure 3.10). However, there are big differences between countries: while 85% of LTC workers in the Netherlands, 80% in Australia and 67% in Iceland are employed part-time, this is the case for less than 5% in Hungary, Lithuania, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Türkiye. This variation between countries roughly follows country differences in the prevalence of part-time work in the full workforce, although it is more pronounced in the LTC sector. This large variation is partly the result of the large share of women in the sector, as cross-country variation in part-time work is typically higher for women than for men. A high share of LTC workers employed part-time is not an indication of a poor working environment in itself as it may fit the worker’s preferences, although it is problematic from a job quality perspective if part-time workers end up working fewer hours than they would prefer (see below).

Note: The OECD average refers to the average of countries for which data on all three data series are available, and does therefore not include Australia, Japan and the United States. Data are not shown for Hungary, Lithuania and Portugal as the share of LTC workers concerned is below the number required to report exact numbers, although the exact share is used for the calculation of the OECD average. Extended reference periods for LTC workers are used for the following countries: data for the period 2019‑21 are used for Estonia; 2018‑21 for Poland; 2016‑21 for Lithuania; and 2015‑19 for the United States. Data only refer to 2020 for Japan and Türkiye, and to 2019 for the United Kingdom. The data for the United States only include residential LTC workers.

Source: EU-LFS; data for Australia from Australian Government Department of Health (2021[41]), 2020 Aged Care Workforce Census Report, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/2020-aged-care-workforce-census, and OECD (2022[42]), Part-time employment rate (indicator), https://www.doi.org/10.1787/f2ad596c-en (accessed on 18 November 2022); data for Japan from Care Work Foundation (2021[18]), 令和3年度介護労働実態調査: 介護労働者の就業実態と就業意識調査 結果報告書 [Survey on Long-Term Care Workers: Report on Employment Status and Employment Attitude Survey of Care Workers], http://www.kaigo-center.or.jp/report/2022r01_chousa_01.html and OECD (2022[42]), Part-time employment rate (indicator), https://www.doi.org/10.1787/f2ad596c-en (accessed on 18 November 2022); data for the United States from Martinez Hickey, Sawo and Wolfe (2022[43]), “The state of the residential long-term care industry: A comprehensive look at employment levels, demographics, wages, benefits, and poverty rates of workers in the industry”, https://www.epi.org/publication/residential-long-term-care-workers/.

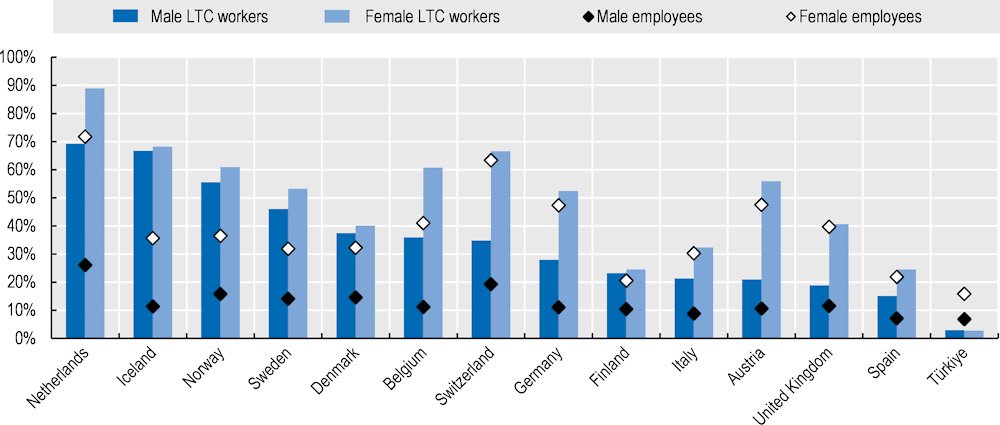

There is a sectoral pattern: the high share of women working in LTC explains only part of the high share of part-time work in LTC. Within LTC, women work part-time more than men, as in the overall economy (Figure 3.11). But even among men, working part-time is much more common in the LTC sector than in the economy as a whole. This is likely the result of care needs being particularly concentrated in the mornings and the evenings, when people need assistance with getting in and out of bed, with getting washed and dressed, and with eating (OECD, 2020[7]). Hence, care workers may opt to work part-time to avoid split shifts and to balance work and family life.

Note: Due to the number of LTC workers working part-time being below the number required to report exact numbers in some countries, data for 2019‑21 are merged. Data only refer to 2019‑20 for Türkiye and to 2019 for the United Kingdom.

Source: EU-LFS.

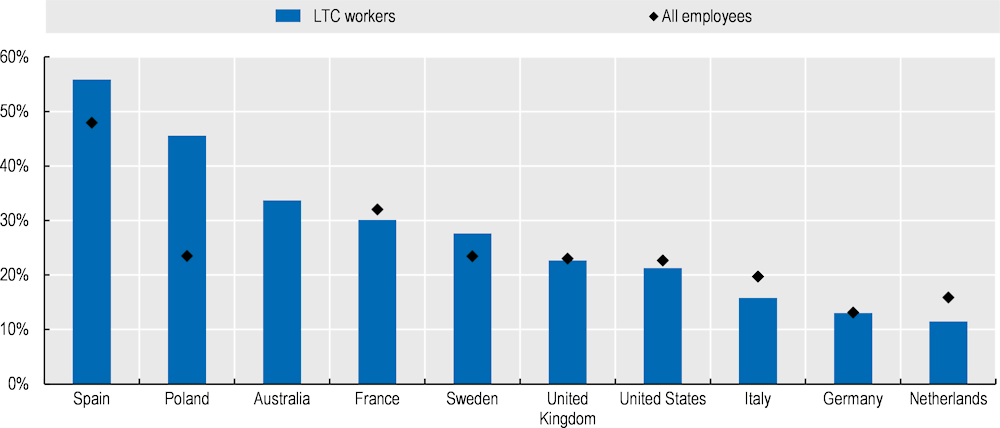

Some LTC workers who are currently working part-time would like to work more hours. This is also the case in some countries reporting a shortage of workers in LTC, where more than 10% of part-time workers in the sector indicate that they work part-time because they cannot find a full-time job (Eurofound, 2020[37]), which is puzzling. One possible explanation could be a mismatch between the times when people would be available to work extra hours and the times when care workers are most needed: LTC workers working part-time may want to work more hours through expanding their current shift, whereas the peaks in demand for care in the mornings and the evenings may mean that working more hours would entail a split shift. Geographical mismatches between care needs and care supply could be an alternative explanation, for instance if older people with unmet care needs particularly live in rural areas whereas the LTC workforce is mainly concentrated in and around towns and cities. Alternatively, LTC providers may be reluctant to offer full-time positions if full-time workers receive supplementary rights or entitlements. In the United States, for instance, nurses working part-time have more limited sick-leave entitlements than those working full-time (Denny-Brown et al., 2020[44]). While reasons for working part-time for the entire LTC sector are similar to those in the overall economy, in non-residential LTC a somewhat larger share of part-time workers indicates that they work part-time because they could not find a full-time job (Eurofound, 2020[37]).

In Poland and Spain, as much as around half of LTC workers working part-time would rather work more (Figure 3.12). In other countries, this is the case for between 10% and 30% of LTC workers on part-time contracts. In most countries for which data are available, the share of underemployed part-time LTC workers fluctuates around that of part-time workers in the full economy. In Australia, 34% of LTC workers would like to work more hours and the share of LTC workers who would like to work full-time is almost 1.3 times the share who effectively do so (Mavromaras et al., 2017[17]). In Japan, in contrast, 14% of care workers would like to work fewer hours, while only 9% would like to work more (Care Work Foundation, 2021[18]).

Note: The data refer to 2015‑21 for Poland and to 2015‑19 for the United States. Data refer to 2016 for Australia and to 2019 for the United Kingdom. The data for the United States only include residential LTC workers.

Source: EU-LFS; Australian data based on Mavromaras et al. (2017[17]), The Aged Care Workforce, 2016, https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/Workforce/The-Aged-Care-Workforce-2016.pdf; data for the United States from Martinez Hickey, Sawo and Wolfe (2022[43]), The state of the residential long-term care industry: A comprehensive look at employment levels, demographics, wages, benefits, and poverty rates of workers in the industry, https://epi.org/249221.

Education and training are important job resources to improve the quality of care, and therefore job satisfaction and the retention of LTC workers (Rajamohan, Porock and Chang, 2019[15]). In particular mentorship programmes for new LTC workers, needs-based training programmes for experienced workers and training on leadership and support for managers have reduced turnover intentions (Halter et al., 2017[45]). Training is a particularly important job resource in home care settings as home care workers often work alone meaning that little support is available (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007[46]). In addition, mastering care techniques is important to minimise physical strain on LTC workers, in particular in homes that often are not designed and equipped for LTC provision.

The share of LTC workers having received education or training in the four weeks before taking part in the LFS survey largely follows the average among all employees across countries, and the OECD average for both is at 17% (Figure 3.13). However, this is slightly below the share for nurses and personal care workers in healthcare, which is at 21%. In particular, in countries where following education and training is commonplace within the overall workforce, LTC workers are above‑average in terms of the likelihood of having participated in an education or training programme. This is the case in Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Likewise, in countries where participating in such programmes is less common, such as Ireland, Portugal and Türkiye, LTC workers are less likely to participate than the average employee.

The Australian 2020 Aged Care Workforce Census Report (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021[41]) provides some detailed statistics on participation in training programmes for LTC workers. Personal care workers completed fewer training opportunities than nurses – on average 3.4 trainings per year compared to 4.7 for nurses. Home care workers completed fewer training courses than those in residential care: a home care nurse on average completed 1.2 training programmes less per year compared to a nurse working in a residential care facility, whereas the difference for personal care workers equals 1.3 trainings per worker per year.12 The differences in training participation between nurses and personal care workers in Australia reflect the differences in their responsibilities to a large extent, although nurses partake in certain non-health-related trainings more than personal care workers. In both residential and home care settings, nurses are more likely than personal care workers to have completed training in wound care, palliative care and infection prevention and control (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021[41]). Among home care workers, personal care workers completed more trainings per worker in dementia care and diversity awareness compared to nurses, whereas nurses were somewhat more likely to have completed trainings in fall risk and elder abuse than personal care workers. In residential care settings, there is little difference between both groups regarding completion of these types of training. In contrast, medications-related training is much more common for nurses than for personal care workers in residential care, whereas there is little difference between both groups in a home care setting. With the exception of medications, differences in course completion between nurses and personal care workers are more pronounced in home care than in residential care.

Note: Data are not shown for Greece, Poland and the Slovak Republic as the share of LTC workers concerned is below the number required to report exact numbers, although the exact share is used for the calculation of the OECD average. Extended reference periods for LTC workers are used for the following countries: data for the period 2019‑21 are used for Portugal; 2018‑21 for Lithuania; 2017‑21 for Latvia; and 2014‑21 for Greece and Poland. Data only refer to 2020 for Japan and Türkiye, and to 2019 for the United Kingdom.

Source: EU-LFS; Japanese data based on Care Work Foundation (2021[18]), 令和3年度介護労働実態調査: 介護労働者の就業実態と就業意識調査 結果報告書 [Survey on Long-Term Care Workers: Report on Employment Status and Employment Attitude Survey of Care Workers], http://www.kaigo-center.or.jp/report/2022r01_chousa_01.html.

While in principle, LTC workers fall under the same labour regulations as other employees, labour regulations have been circumvented in several countries, in particular for live‑in care. Regulations limiting working hours or setting minimum wages make live‑in 24‑hour care provision expensive, making the sector vulnerable to the use of unpaid and undeclared or partially declared employment, often provided by immigrants. In addition, the enforcement of labour regulations can be complicated by contracting LTC workers through placement agencies posting workers from abroad.

Across the European Union, undeclared LTC work appears to occur in particular in countries where formal LTC wages are relatively high, where LTC is largely home‑based and where LTC entitlements of people with needs are either limited or consist of cash payments with little control on how they are used. Italy’s ‘badanti’, for instance, refer to workers providing personal care in people’s homes, often immigrants living in with the care recipient. While official statistics include around 400 000 personal care workers, estimates including undeclared workers range around 1 million, with a majority either not having a formal employment contract or working on a contract for fewer hours of caregiving than are effectively supplied (Facchini, 2022[47]; Pasquinelli and Pozzoli, 2021[48]).

In countries where LTC work is largely formal, such as in Denmark and France, it is not uncommon for workers to provide some additional hours of care undeclared according to Eurofound (2020[37]). In Austria, labour regulations applying to employees for live‑in LTC workers can be circumvented if these workers register as self-employed (Trukeschitz, Österle and Schneider, 2022[49]). Migrant care workers have been an important source of LTC since the 1990s in Austria, typically in an arrangement where two workers would rotate every two weeks to provide care for an older person. The practice became regularised in 2007 with the implementation of the 24‑hour care scheme, allowing these LTC workers to register as self-employed. In doing so, regulations on work schedules, maximum working hours and minimum wages were bypassed. In 2019, about 60 000 care workers took care of about 30 000 older people through this scheme. Similarly, LTC workers are sometimes hired as self-employed in the Netherlands even if they only provide services to a single person, resulting among others in fewer social security entitlements than would be the case if they were hired as employees (OECD, 2020[7]).

A report on compliance with labour protection regulations among home care workers providing publicly funded care in the United States shows that several states provide exceptions to maximum limits on working hours (Doty, Squillace and Kako, 2019[50]). States are responsible for determining limits to working hours for LTC workers, typically set between 40 and 50 hours per week, although 17 states provide exceptions to these limits. In California, for instance, the maximum limit on working hours is 66 hours per week (40 hours for a full-time worker, plus 26 hours overtime), but the limit is 70.75 hours for a live‑in LTC worker with a single care recipient; under some circumstances an LTC worker can ask for permission to work up to 90 hours per week caring for two or more people living in the same home.13 In total, 13 states provide exceptions to maximum working hours regulations for live‑in LTC workers, although some states have deliberately chosen not to allow this for publicly funded care to avoid any legal responsibility for having to pay out banked overtime hours plus penalties in case the care recipient did not cover overtime from the public funds received.

Collective bargaining and workers’ voice are key labour rights; they can also be enablers of inclusive labour markets (OECD, 2019[51]). Typically, collective bargaining and/or union coverage may provide better working conditions and standardised pay scales for workers: for instance, by comparing the earnings of care workers in the United States and 24 European countries, Ferragina and Parolin (2021[52]) find that differences in labour market and welfare state institutions14 explain most of the difference in the relative earnings of LTC workers across countries. In particular, higher rates of collective bargaining coverage as well as stronger employment protection and welfare state spending, are associated with higher earnings for care occupations.

Collective bargaining matters also for non-monetary aspects of job quality, such as occupational safety and health, working time, training and re‑skilling policies, management practices, and the prevention of workplace intimidation and discrimination.

Yet, the capacity of collective bargaining systems to deliver, in particular for workers in the service sector, is being increasingly challenged by the general weakening of labour relations in many OECD countries, the flourishing of new − often precarious – forms of employment and a tendency towards the individualisation of employment relationships. Since the 1980s, collective bargaining systems have been under increasing pressure in most OECD countries. Trade union density (the share of workers who are union members) has declined across OECD countries losing more than half of its reach from 38% on average in 1975 to 16% in 2019. Similarly, the share of workers covered by a collective agreement shrank to 32% on average in the OECD area in 2019 from 45% in 1985.

In all OECD countries, LTC workers and employers can associate to express their interests and concerns, as well as to bargain over the terms and conditions of employment.15 However, the actual degree of organisation and coverage differs significantly across countries. Even if de jure there are no restrictions to unionise and organise for LTC workers in any OECD country, the presence of many employees in non-standard forms of employment (i.e. without an open-ended contract) may de facto limit the ability to unionise, especially where trade unions are already less strong. Across OECD countries, on average, non-standard workers have a lower unionisation rate compared with standard ones (OECD, 2019[51]). Higher job turnover and shorter average job tenure, resulting in workers’ limited attachment to workplaces, could also reduce their incentives to join unions as well as their opportunities to do so.

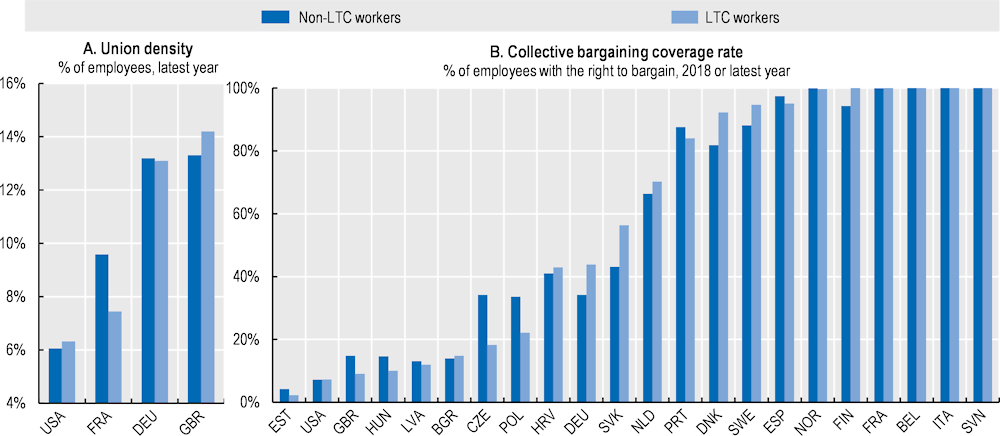

The available data suggest that unionisation and bargaining coverage among LTC workers working with an employment contract (i.e. employees, not self-employed or workers in the informal sector, hence providing a partial picture of the overall workforce in the sector) tend to mirror quite closely the degree of unionisation and coverage among the general employee population.

Among the four countries where microdata allow to measure trade union membership among specific occupations (Figure 3.14), France is the only country where trade union density is lower among LTC workers than among the rest of the workforce (7.4% of private‑sector LTC employees are unionised compared to 9.6% among the other workers). In Germany, the United Kingdom or the United States, trade union density among LTC workers is in line with the national average.

A similar pattern emerges when looking at collective bargaining coverage for which a larger number of countries can be covered by the data (see Box 3.1 about the measurement of bargaining coverage in the LTC sector). In the large majority of OECD countries in Figure 3.14, bargaining coverage among LTC workers is similar to that of the rest of the workforce. Only in the Czech Republic and Poland, does coverage among LTC workers appear to be significantly lower than among other employees; conversely, in Denmark, Germany and the Slovak Republic, coverage among LTC workers is higher than in the rest of the workforce.

Note: LTC workers are strictly defined as personal care workers in health services (ISCO‑08 code 532) and nurses (ISCO‑08 codes 222 and 322) working in residential nursing care activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code 871), residential care for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 873) and social work activities without accommodation for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 881). However, the figures presented in this Chart refer to approximate definitions, taking into account the level of detail of the industries and occupations available in the surveys and the national classifications of these two variables which may differ from international classifications (i.e. ISCO‑08 and ISIC Rev. 4). LTC workers refer to health professionals (ISCO‑08 code 22), health associate professionals (ISCO‑08 code 32) and personal care workers (ISCO‑08 code 53) working in human health and social work activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code Q) for France in Panel A and Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden in Panel B; to personal care workers in health services (ISCO‑08 code 532) and nurses (ISCO‑08 codes 222 and 322) working in human health and social work activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code Q) for Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Italy, Latvia, Norway, Poland and the Slovak Republic in Panel B; to personal care workers in health services (ISCO‑08 code 532) and nurses (ISCO‑08 codes 222 and 322) working in residential care activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code 87) and social work activities without accommodation (ISIC Rev. 4 code 88) for Germany in Panel A; to caring Personal Services (SOC2010 code 614) and nurses (SOC2010 codes 222) working in residential nursing care activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code 871), residential care for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 873) and social work activities without accommodation for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 881) for the United Kingdom (Panels A and B); and to personal care workers (2010 Census occupational codes 3600 3610, 3620, 3655 and 4610) and nurses (2010 Census occupational codes 3255, 3256, 3258, and 3500) working in nursing care facilities (2012 Census industry code 8270), residential care facilities, except skilled nursing facilities (2012 Census industry code 8 290), home healthcare services (2012 Census industry code 8170) and personal care workers working in individual and family services (2012 Census industry code 8370) as nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides (2010 Census occupational codes 3600) for the United States (Panels A and B). Luxembourg is not included due to data limitations, although in principle collective agreements are extended to all workers and firms in the sector.

In Panel A, figures refer to the average of the years 2013 and 2016 for France; 2015 and 2019 for Germany; and 2017 to 2019 for the United Kingdom and the United States. Figures for Norway in Panel B refer to the year 2014.

Source: OECD estimation of union densities (Panel A) based on the Enquête Statistiques sur les Ressources et Conditions de Vie (SRCV, 2013 and 2016) for France; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2015 and 2019) for Germany; the UK labour Force Survey (UKLFS, 2017, 2018 and 2019) for the United Kingdom; and the Current Population Survey (CPS, 2017, 2018 and 2019) for the United States. For the collective bargaining coverage rate (Panel B), OECD estimations based on the European Structure of Earnings Survey (SES, 2018) for all countries excepted the United Kingdom and the United States; the UK labour Force Survey (UKLFS) for the United Kingdom; and the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the United States.

Data on bargaining coverage usually come from the bargaining parties, collected through registration at the Labour or Employment Ministry, by national union or employers’ confederations or Mediation Boards, by statistical offices based on surveys, or research centres. However, only data from surveys allow a granular analysis at occupational level such as the one needed in this chapter. Survey data have the merit that it excludes double counting, refers only to valid agreements that apply during the reference period, and the data can be used for statistical analyses. However, there are also potentially significant drawbacks. First, this limits country coverage; second, respondents may not necessarily know that they are covered by an agreement; third, small firms are often excluded from the sample leading to an overestimation of coverage; fourth, the wording of the question matters for the final estimates: for instance, the EU Structure of Earnings Survey asks managers to identify the pay agreement covering at least 50% of the employees in the local unit (hence, excluding occupation-specific agreements that may apply only to some employees in the firm or non-wage agreements). Moreover, jobs in the LTC sector are defined at an occupational and sectoral level that is not always available in the microdata used to compute coverage (see notes below the figures). The data presented in this chapter should, therefore, be interpreted with caution.

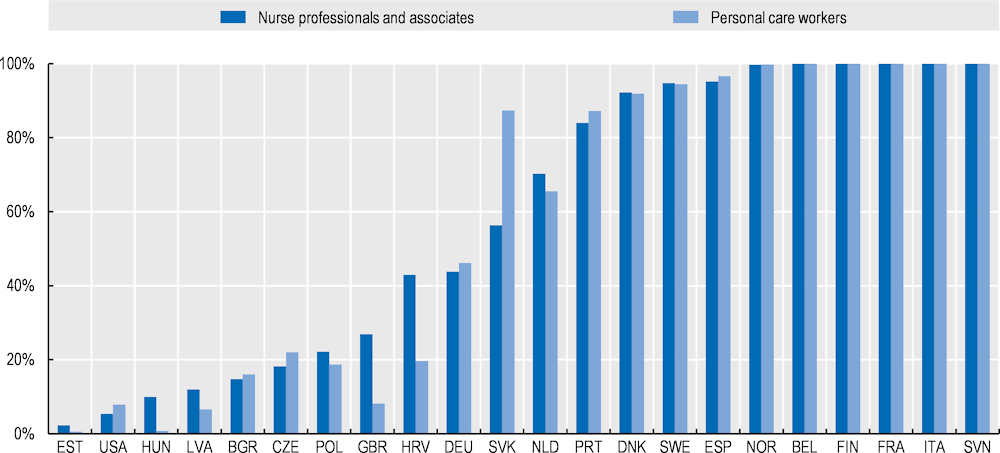

As discussed in Chapter 2, formal LTC workers comprise two main professional categories: nurses and personal care workers, with the first category including both nurse associates and nurse professionals. Depending on the functioning of the system and the design of collective agreements (some agreements may cover only specific occupations), bargaining coverage across the two professional categories may differ. Data for European Union countries (Figure 3.15) show, however, no major differences between the two professional categories. Except for Croatia and the Slovak Republic, bargaining coverage among nurses and personal care workers is quite similar even if not perfectly aligned (confirming that they may be covered by different agreements). Specific challenges concerning the category of LTC workers at home are discussed in detail in Box 3.2.

All in all, the analysis above suggests that LTC workers do not fare worse (or better) in terms of bargaining coverage than the average employee. Yet their working conditions are generally worse than the rest of the workforce in many dimensions. What could explain this apparent inconsistency? Beyond trade union density and collective bargaining coverage, there are other critical determinants of the effective workers’ bargaining power that are harder to measure. First, while high coverage is reached in some countries through administrative extensions of collective agreements concluded at sectoral level, unions do not systematically have the power to negotiate meaningful improvements to working conditions in all sectors. Second, in some countries, like Germany or Italy, the (de facto or de jure) possibility for companies to opt out from their own sectoral agreement matters a lot for the final bargaining outcomes.16 Third, in some cases, workers are still covered by collective agreements that have expired as a way to ensure some continuity of the system (the so-called “ultra‑activity”). In such case, while most provisions remain binding, wages are eroded in real terms, especially in times of soaring inflation.17 Finally, compliance with the provisions of collective agreements, even in the formal sector, is not necessarily perfect. There are no precise estimates of the extent of non-compliance among LTC workers but Garnero (2018[53]) shows that 8.2% of the employees in the healthcare sector in Italy in 2015 were paid less than their reference minimum wage. In conclusion, while being usually a useful proxy of the organisation of collective bargaining, high bargaining coverage per se is not a sufficient condition to ensure good working standards, in particular in a sector such as LTC where domestic work is common while undeclared work and false18 self-employed may also be widespread.

Many people in need of LTC care wish to remain in their homes for as long as possible. In response to these preferences and the high costs of LTC facilities, many OECD countries have promoted services to support home‑based care for older adults. This raises additional and specific challenges for extending social dialogue and collective bargaining to these workers.

First, many of these workers are informal. Promoting social dialogue and collective bargaining, hence, goes hand-in-hand with efforts to promote formalisation. In France, a universal service employment voucher provides families with a simplified hiring process and low costs to formalisation. This system comes together with a specific collective agreement (Convention collective de la branche du secteur des particuliers employeurs et de l’emploi à domicile) that regulates all aspects of the working relationship, starting from the minimum wage and that is regularly updated. The French system is relatively simple and extensively used by households. However, it is also very expensive for public finance and has a regressive feature – more than 60% of these tax deductions go to the richest 10% households according to Carbonnier and Morel (2015[54]).

Second, by working at home, these workers do not have a unified place of work where they can meet, discuss and organise. Gig and platform workers face a similar challenge and unions and workers’ organisations are making an effort to reach them online. This is more challenging for LTC workers at home who do not work online.

Third, an important barrier to social dialogue and collective bargaining that is specific to workers working at home is the difficulty in organising employers. In most OECD countries, employers (families) are not organised in associations, nor do they negotiate with trade unions or public authorities. Domestic workers face a similar challenge. At the EU level, two organisations represent personal and household services employers, EFFE and EFSI, from France and Italy, which are the two European countries with collective agreements for domestic workers. The current Spanish Government, for instance, is seeking to encourage social dialogue on domestic work, but cannot make progress without an organisation representing employers.

For a more in-depth discussion of the challenges related to LTC workers at home see a dedicated brief by the Global Deal (forthcomimg[55]).

Note: LTC workers are strictly defined as personal care workers in health services (ISCO‑08 code 532) and nurses (ISCO‑08 codes 222 and 322) working in residential nursing care activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code 871), residential care for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 873) and social work activities without accommodation for the elderly and disabled (ISIC Rev. 4 code 881). However, the figures presented in this Chart refer to approximate definitions, taking into account the level of detail of the industries and occupations available in the surveys and the national classifications of these two variables which may differ from international classifications (i.e. ISCO‑08 and ISIC Rev. 4). LTC workers refer to health professionals (ISCO‑08 code 22), health associate professionals (ISCO‑08 code 32) and personal care workers (ISCO‑08 code 53) working in human health and social work activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code Q) for Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden; to personal care workers in health services (ISCO‑08 code 532) and nurses (ISCO‑08 codes 222 and 322) working in human health and social work activities (ISIC Rev. 4 code Q) for Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Italy, Latvia, Norway, Poland and the Slovak Republic; and to personal care workers (2010 Census occupational codes 3600, 3610, 3620, 3655 and 4610) and nurses (2010 Census occupational codes 3255, 3256, 3258, and 3500) working in nursing care facilities (2012 Census industry code 8270), residential care facilities, except skilled nursing facilities (2012 Census industry code 8 290), home healthcare services (2012 Census industry code 8170) and personal care workers working in individual and family services (2012 Census industry code 8370) as nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides (2010 Census occupational codes 3600) for the United States. Luxembourg is not included due to data limitations, although in principle collective agreements are extended to all workers and firms in the sector.

Source: OECD estimations based on the European Structure of Earnings Survey (SES, 2018) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the United States.

Most of the cross-country differences in unionisation levels and bargaining coverage among LTC workers shown in Figure 3.14 and Figure 3.15 can be explained by national differences in the collective bargaining system itself: collective bargaining coverage has remained high and relatively stable only in countries where multi‑employer agreements (i.e. at sectoral or national level) are negotiated – more or less frequently – and where the share of firms that are members of an employer association is high, or where agreements are extended19 also to workers working in firms which are not members of a signatory employer association – see OECD (2019[51]) for a detailed characterisation of the functioning of the collective bargaining system in each OECD country. In several OECD countries, there is no system of sectoral bargaining in place and therefore LTC workers, like all other workers, can only negotiate at firm-level, if and where they manage to organise (Table 3.2).

|

Country |

Collective agreements in LTC |

|---|---|

|

Australia |

Australia does not have a system of sectoral collective agreements only company-level bargaining. Modern Awards, together with the legislated National Employment Standards, provide minimum employment standards for employees in the national industrial relations system. |

|

Austria |

Collective bargaining is common. Regional, single‑employer and specific types of care home (confessional) collective agreements. |

|

Belgium |

Collective bargaining is common at national, sectoral and company level. |

|

Canada |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Czech Republic |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Denmark |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. Only few private‑sector LTC workers are excluded. |

|

Estonia |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Finland |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

France |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Germany |

As of 1 September 2022, all long-term care services and nursing homes must pay their employees who work in the field of nursing and care support at the level of the regional collective agreements. |

|

Greece |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs mostly at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Hungary |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Ireland |

Collective bargaining occurs mostly at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Israel |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Italy |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Latvia |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Lithuania |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Luxembourg |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Netherlands |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Norway |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Poland |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Portugal |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Slovak Rep. |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

Slovenia |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. |

|

Spain |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral, local and company level. |

|

Sweden |

Collective bargaining is common at sectoral and company level. Only workers in small private companies may not always be covered. |

|

Switzerland |

Collective bargaining occurs mostly at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

United Kingdom |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

|

United States |

Collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at the level of the employer or workplace. |

Source: OECD questionnaire on long-term care and Eurofound (2020[37]), Long-term care workforce: Employment and working conditions, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/customised-report/2020/long-term-care-workforce-employment-and-working-conditions. Information on Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand and Türkiye not available.

In Austria, for instance, collective agreements in the LTC sector are regularly negotiated at company level between management and a work council, and annually at national level during negotiations between industry social partners (employers and trade unions). In 2019, the negotiation led to a 3.2% increase in wages for the whole workforce and to paid leave agreements (European Commission and Social Protection Committee, 2021[56]). In Spring 2020, private‑sector unions entered the annual collective bargaining round in the social economy sector with only one demand, to reduce working hours from 38 to 35 hours per week and waive a wage increase. A three‑year agreement between the social partners was reached in April 2020. The social partners agreed to wage increases for 2020 and 2021, and to reduce working time to 37 hours from 1 January 2022 (Allinger and Adam, 2022[57]).

In Germany, already before COVID‑19, various measures were introduced with the aim of raising pay in LTC, including provisions to make more home care service providers subject to collective agreements and introducing a legal basis to improve wage conditions for care workers. In addition, an obligation was introduced to pay wages at least at collective bargaining level to employees who work in the field of LTC (Gesundheitsversorgungsweiterentwicklungsgesetz). As of September 2022, the German statutory care insurance is only allowed to conclude supply contracts with residential and home care providers if they comply with this regulation. This new requirement is met if LTC facilities that are not bound by collective wage agreements either pay wages to their LTC workers at least at the level of the regionally applicable collective agreement or if they pay wages that correspond at least to the average payment level of care facilities that are bound to the collective agreement in the region.

Beyond the functioning of the collective bargaining system itself, other rules and procedures may provide incentives (or disincentives) to negotiate collective agreements. For instance, Sánchez-Mira, Olivares and Oto (2021[58]) argue that in Spain, despite an increasing decentralisation in collective bargaining in the LTC sector, the precedence given to sectoral agreements in the public procurement process has allowed preventing a move towards “disorganised decentralisation”.20 In fact, moderate decentralisation in Spain has favoured heterogeneity in pay and working conditions at regional and provincial levels but has also led to improvements in working standards with respect to the national collective agreement (Sánchez-Mira, Olivares and Oto, 2021[58]).

Even where collective bargaining in the private sector is rare and mostly confined to the company/workplace level, what is negotiated in the public sector can have an influence on the private sector. In the Czech Republic, for instance, where collective bargaining is rare and occurs only at company/workplace level, since 2017, wages in the care sector have increased substantially both in the public and private sector thanks to an agreement with social partners in the public sector.