Effective skills governance arrangements facilitate co‑ordination across the whole of government, support the effective engagement of stakeholders and enable the development of integrated information systems and co‑ordinated skills financing arrangements. This chapter reviews the current practices and performance of Bulgaria’s skills governance. It then explores three opportunities to strengthen the governance of Bulgaria’s skills policies: 1) developing a whole-of-government and stakeholder-inclusive approach to skills policies; 2) building and better utilising evidence in skills development and use; and 3) ensuring well-targeted and sustainable financing of skills policies.

OECD Skills Strategy Bulgaria

5. Improving the governance of the skills system in Bulgaria

Abstract

The importance of improving the governance of the skills system

A wide range of actors have an interest in and influence the success of policies to develop and use people’s skills. They include central government ministries and agencies, subnational authorities, such as municipalities, education and training institutions, workers and trade unions, employers and their associations, civil society organisations and more. As a result, skills systems are complex and multi-faceted and require effective co‑ordination between a wide variety of actors to design, implement, evaluate and fund skills policies.

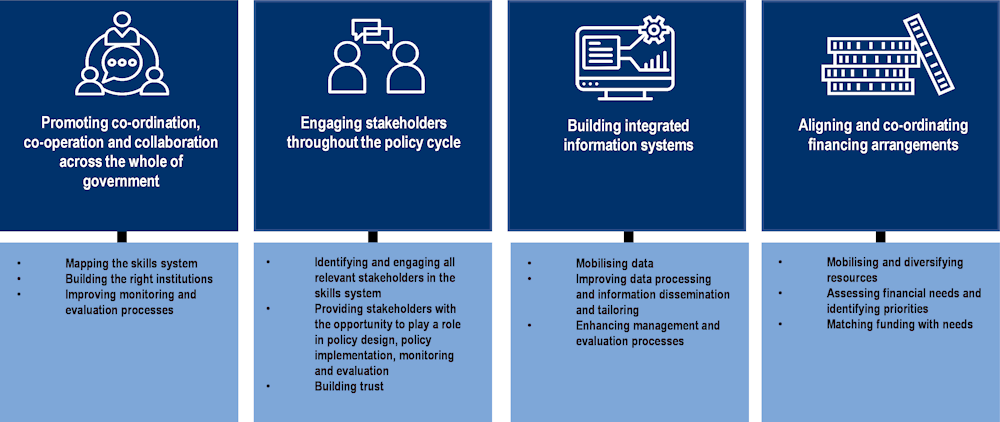

The OECD identifies four distinct but interconnected pillars central to developing an effective approach to skills governance. They include: promoting co‑ordination, co‑operation and collaboration across the whole of government; engaging stakeholders effectively throughout the policy cycle; building integrated information systems; and aligning and co‑ordinating financing arrangements (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Four pillars for strengthening the governance of skills policies

Source: OECD (2019[1]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264313835-en.

The first pillar emphasises the importance of co‑ordination across the whole of government (a “whole-of-government approach”). This includes horizontal co‑ordination between the ministries directly responsible for skills policies, and with those indirectly impacting skills policies (such as the ministries of finance via their roles in funding decisions). A whole-of-government approach also includes vertical co‑ordination between different levels of government, from central government to regional authorities and municipalities.

The second pillar emphasises the importance of stakeholder engagement in skills policies. Stakeholder engagement can occur during policy design, implementation and evaluation and ranges from stakeholders voicing their interests or concerns to taking responsibility for implementing skills policies. Effective engagement can provide important intelligence for policy makers and build stakeholders’ buy-in to reform, all of which help to ensure the success of skills policies.

The third pillar recognises that integrated information systems on skills needs and outcomes are necessary for the actors in the skills system to cope with the inherent complexity and uncertainty of skills investments. Such systems help governments develop evidence-based skills policies; learning institutions to provide relevant and responsive courses; employers to plan hiring and training; and individuals to make informed learning and career decisions.

The final pillar underscores the necessity of aligning and co‑ordinating financing arrangements within skills policy. This includes the need to respond to financial challenges, such as the potential reallocation of funding commitments across different elements of the skills system (e.g. between initial and adult vocational education and training [VET], higher education, active labour market policies [ALMPs], etc.), dedicated funding commitments for strategic goals, and making the most efficient use of external funding (e.g. the European Social Fund).

These four pillars of skills governance represent enabling conditions for developing and using people’s skills effectively, as discussed in Chapters 2, 3 and 4 of this report. For example, without integrated skills information systems informing the supply and demand for learning programmes, youth (Chapter 2) and adults (Chapter 3) may not develop the skills most needed in work and life, thereby perpetuating skills imbalances. Likewise, without effective stakeholder engagement to design tailored policies and targeted and sustainable funding arrangements, policies for activating the skills of out-of-work adults (Chapter 4) may be ineffective.

Overview and performance

Overview of Bulgaria’s current governance arrangements

Bulgaria’s two levels of government – national and municipal – have formal skills policy responsibilities (Table 5.1). At the national level, the management of education institutions and the formal education and training system overall comes under the Ministry of Education and Science (MES). The Ministry of Labour and Social Policy (MLSP) is responsible for the National Employment Agency (NEA) and its programmes, including the delivery of some VET programmes by education institutions for unemployed adults. Other ministries have more limited responsibilities and activities in the area of skills.

These ministries are responsible for a range of skills-related strategies (see Chapter 1), including the National Development Programme “Bulgaria 2030”, the Strategic Framework for the Development of Education, Training and Learning (2021‑2030), the National Strategy for Employment (2021‑2030), the Strategy for the Development of Higher Education (2021‑2030), the Innovative Strategy for Smart Specialisation (2021‑2027) and the National Strategy for Small and Medium Enterprises (2021‑2027), among others. Each ministry has distinct objectives and processes, key success indicators and timetables while also depending on other ministries and agencies to achieve its objectives. To help ensure the achievement of these strategies, MES will work with other ministries and stakeholders to develop an action plan for skills policy, with support from the Directorate-General for Structural Reform Support (DG REFORM) of the European Commission and the OECD (OECD, 2021[2]).

Beyond the national level, MES also has 28 regional departments of education (REDs) whose task is to create the conditions for implementing the state education policy. REDs provide a forum for co‑ordination between different education and training providers and stakeholders, and monitor compliance with the state educational standards, within regions (Eurydice). Furthermore, the constitution gives Bulgaria’s 265 municipalities a relatively broad set of powers and autonomy, including in skills policy. Municipalities have state-delegated competencies for primary and secondary education, and welfare and social protection, among others. However, most Bulgarian municipalities are financially dependent on fiscal transfers and policy direction from the central government as their own revenue sources and capacity are limited.

Table 5.1. Bulgaria’s main actors, roles and responsibilities related to skills governance

|

Actor |

Roles/responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

National authorities and agencies |

|

|

Ministry for Education and Science (MES) |

MES is responsible for Bulgaria’s education system, including vocational education and training (VET), lifelong learning and higher education. MES’ key skills-related activities include updating official lists of qualifications and competencies, funding educational institutions and overseeing key educational institutions. The National Development Programme “Bulgaria 2030” tasks MES with co‑ordinating all levels of education and training and creating a clear division of responsibilities between relevant national and/or regional authorities, providing analytical and administrative capacity at all levels for planning, monitoring and evaluating the policies in education and improving the system of higher education management (with a balance between academic autonomy and state and public interests). The Strategic Framework for the Development of Education, Training and Learning (2021‑2030) tasks MES to oversee data collection and reporting mechanisms, establish competencies for education institutions and develop sectoral clusters of VET schools. |

|

Ministry for Labour and Social Policy (MLSP) |

The MLSP is responsible for employment, welfare and social protection policy in Bulgaria, including active labour market policies (ALMPs). The ministry’s key skills-related activities include employment and skills forecasting and oversight of key agencies in Bulgaria’s skills ecosystem, including the National Employment Agency (NEA). The Partnership Agreement for European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) (2021-2030) tasks the MLSP with better anticipating employers’ workforce needs to improve matching between education, training and business; strengthening interaction between labour market institutions, education, training systems and employers; building the administrative capacity of the NEA to identify and meet the skills needs of the labour market; and improving the labour market matching services and quality of the NEA. |

|

Ministry for Innovation and Growth (MIG) |

MIG is responsible for innovation and economic growth policies at the national and local levels. The ministry’s key skills-related responsibilities include funding for innovation and research and development (R&D) activity; the development of industrial parks; and the designation of centres of excellence in VET and higher education. The Innovative Strategy for Smart Specialisation (2021-2027) tasks MIG with improving human capital; strengthening the relationship between higher education and labour market requirements; stimulating training in technical and engineering specialities; enhancing practical training in higher education; reforming vocational training and qualifications and promoting lifelong learning; promoting the internationalisation of innovations; improving the quality of research; and addressing the brain drain phenomenon. |

|

Ministry for Economy and Industry (MEI) |

The MEI is responsible for general economic policy in Bulgaria. The MEI’s key skills-related activities include implementing the digital transformation of Bulgarian industry (Industry 4.0) and implementing aspects of Bulgaria’s smart specialisation strategy. The MEI participates in the processes of updating, consulting and formulating educational policies in the context of economic development through involvement in the Consultative Council for Vocational Education and Training (CCVET) at the political level and involvement in the expert group supporting CCVET at the expert level. |

|

Ministry for Regional Development and Public Works (MRDPW) |

The MRDPW is responsible for local and regional (municipal level) government. More specifically, the MRDPW’s skills-related activities include responsibility for delivering some education, skills and employment activities at the local and regional levels, including policy delivery, funding and collecting key data on skills needs, the performance of programmes/institutions and stakeholder involvement. |

|

Ministry for Culture |

The Ministry for Culture is responsible for culture and arts overall, but in relation to the education and skills system, this includes arts schools in both the initial and continuing education and training system. |

|

Ministry for Youth and Sports |

The Ministry for Youth and Sports is responsible for youth issues and sports overall, but in relation to the education and skills system, this includes specialist sports schools in both the initial and continuing education and training system. |

|

Subnational authorities |

|

|

Regional departments of education (REDs) |

These 28 departments are regional administrative structures under the purview of MES and are located in each of the country’s 28 regions. They are responsible for implementing state education policy within their regions, including monitoring compliance with state educational standards and other national laws and regulations. In addition, REDs co‑ordinate between schools and other regional or local bodies, such as local governments and employers. |

|

Municipalities |

Municipalities are responsible for education and skills governance at the local level. Municipal education authorities implement local education policy, including conducting and supervising compulsory school education and overseeing enrolment, access to education and inclusion in the education system. Municipal educational institutions are funded through municipal budgets. |

|

Non-government stakeholders |

|

|

Education and training providers |

Education and training providers are responsible for imparting knowledge and skills over the life course. Education and training providers in Bulgaria include early childhood, primary and secondary schools; VET gymnasiums and colleges; universities and tertiary colleges; VET centres, community cultural centres (chitalishta), enterprises, trade unions and employers’ organisations. |

|

Employers and associations |

Employers engage with the larger Bulgarian skills system through the dual training system, in which employers and education and training providers partner to incorporate practical training for students in a real work setting and through providing or supporting training their employees. Some employers’ associations offer training or even operate centres for continuous education and training. |

|

Workers and trade unions |

Trade unions sometimes organise trainings or seminars for members, often on an ad hoc basis. A number of these trainings are also open to individuals who are not part of the trade union. |

Source: Government of Bulgaria (2022[3]), Responses to the OECD Questionnaire for the OECD Skills Strategy Bulgaria.

Bulgaria’s performance in skills governance

Whole-of-government co‑ordination and capacity

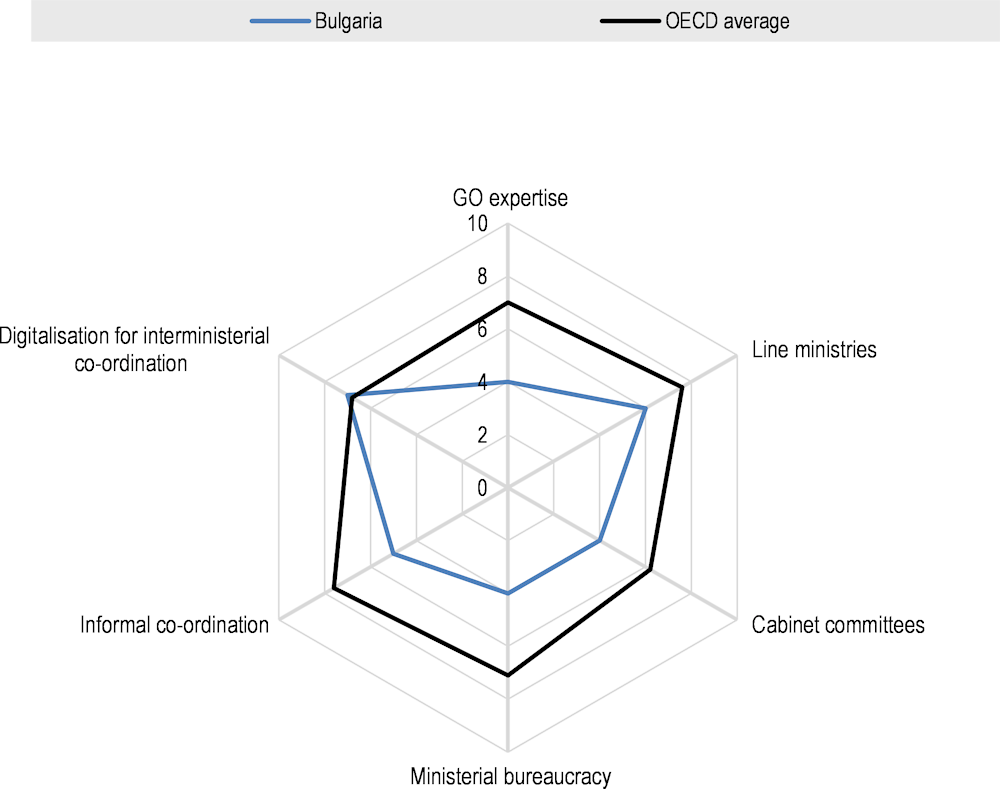

Bulgaria’s performance in horizontal co‑ordination between national ministries and agencies and in vertical co-ordination with subnational authorities is relatively low, including for skills policies. Project participants stated that policy design and delivery are often fragmented and poorly co‑ordinated. As noted in Chapter 1, while not limited to skills policy, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s 2022 Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) scores Bulgaria’s performance in inter-ministerial co‑ordination below the OECD average (Figure 5.2) and ranks it 37th of 41 countries (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]). This result reflects Bulgaria’s low performance in several domains, including the government office’s limited capacity to evaluate ministries’ policy proposals, the lack of formal cabinet or ministerial committees to co‑ordinate such proposals, and limited inter-ministerial co‑ordination by senior civil servants. Vertical co‑ordination with subnational actors (especially municipalities) is hampered by these actors’ limited capacity and the lack of a central institution to oversee the skills system and bring subnational actors to the table. More generally, public governance in Bulgaria, including of the skills system, has been hampered by instability arising from repeated short-lived coalitions and caretaker governments (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]).

Inter-ministerial co‑ordination is not effectively mitigating against complexity and fragmentation in Bulgaria’s skills system, or assuring effective strategic planning, implementation or monitoring of priorities. Project participants often raised these challenges, with some stating that ineffective inter-ministerial co‑ordination had led to a plethora of related projects being started by different ministries. Many of these have not been fully implemented or evaluated since the initial project funding expired. This “churn” in developing and introducing new policies and instruments is indicated by, for example, the estimated 27 amendments to the VET Act since 1999 (European Commission ESIF and World Bank, 2020[5]).

Figure 5.2. Bulgaria's performance in inter-ministerial co-ordination

Note: 0 is lowest, 10 is highest rating. Government office (GO) expertise: Does the government office/prime minister's office (GO/PMO) have the expertise to evaluate ministerial draft bills substantively? Line ministries: To what extent do line ministries involve the GO/PMO in the preparation of policy proposals? Cabinet committees: How effectively do ministerial or cabinet committees co-ordinate cabinet proposals? Ministerial bureaucracy: How effectively do ministry officials/civil servants co-ordinate policy proposals? Informal co-ordination: How effectively do informal co-ordination mechanisms complement formal mechanisms of inter-ministerial co-ordination? Digitalisation for inter-ministerial co‑ordination: How extensively and effectively are digital technologies used to support inter-ministerial co-ordination.

Source: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022[6]), Sustainable Governance Indicators, https://www.sgi-network.org/2022/Bulgaria.

Stakeholder engagement

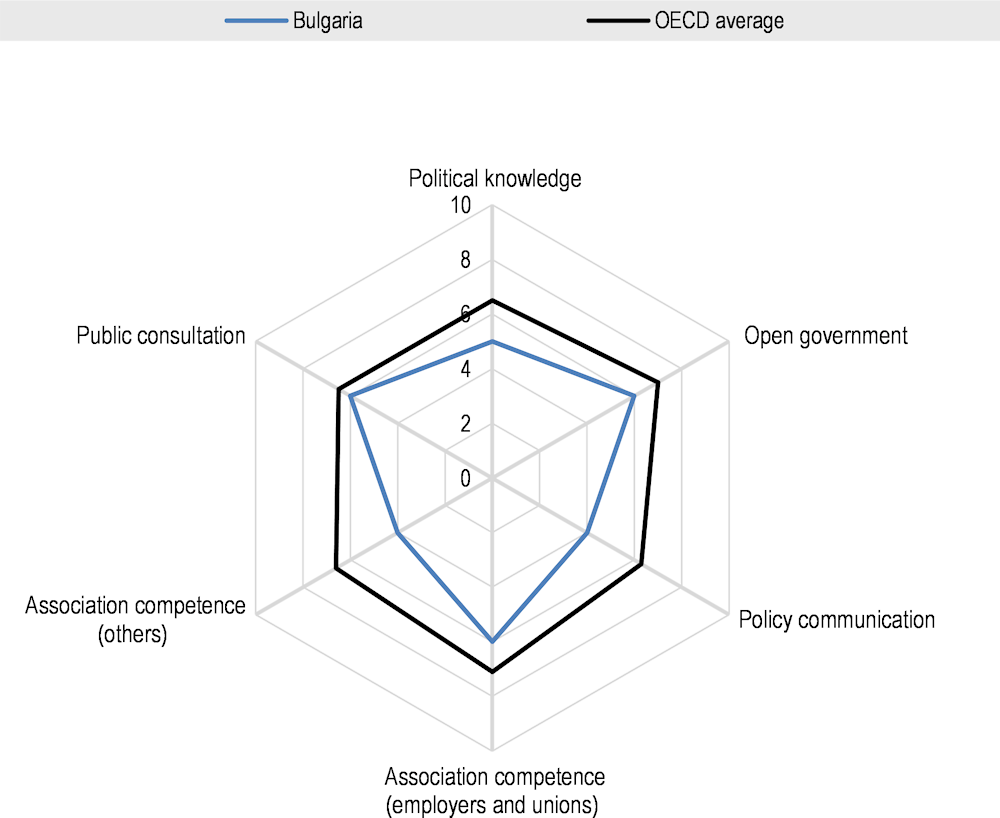

Bulgaria’s performance in stakeholder engagement is also relatively low, including for skills policies, but appears to be improving. Again, as noted in Chapter 1, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s 2022 SGI ranked Bulgaria’s performance in stakeholder engagement below the OECD average (Figure 5.3). On the positive side, various interests are represented in consultations in the policy-making process, including through the National Council for Tripartite Cooperation’s formal and expanding role and through Bulgaria’s 70+ advisory councils, which sometimes include academia and research institutes and cover skills topics. However, there is little systematic practice of publishing minutes of meetings and decisions taken by these various consultative bodies and working groups. This makes it difficult to assess these bodies’ effectiveness and to monitor the implementation of adopted decisions. In some cases, public consultations on policy proposals have often been short or altogether skipped. That said, government agencies are becoming more transparent about their deliberations, and in 2021, the government substantially increased the number of consultations (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]).

Figure 5.3. Bulgaria’s performance in stakeholder engagement

Note: 0 is lowest, 10 is highest rating. Public consultation: Does the government consult with economic and social actors in the course of policy preparation? Political knowledge: To what extent are citizens informed of public policies? Open government: Does the government publish data and information in a way that strengthens citizens' capacity to hold the government accountable? Equality of participation: What percentage of the people have voiced their opinion to a public official in the last month? Association competence: To what extent are economic interest associations (e.g. employers, industry, labour) capable of formulating relevant policies?

Source: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022[6]), Sustainable Governance Indicators, https://www.sgi-network.org/2022/Bulgaria.

Stakeholder engagement remains fragmented despite the growing number of mechanisms in place. Several recent studies suggest that ministries lack the capacity for effective engagement in VET (OECD, 2019[7]; Ganev, Popova and Bonker, 2020[8]) Officials and stakeholders consulted during this Skills Strategy project (hereafter, “project participants”) suggest this is a more generalised challenge for Bulgaria’s skills system as a whole.

Integrated skills information systems

Insufficient co‑ordination between ministries and with stakeholders appears to have contributed to, and been amplified by, fragmented and inconsistent collection and use of skills information and evidence. There are examples of good practices of data collection, evaluation and analysis within different ministries and agencies. For example, Bulgaria’s skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) activities include numerous activities, such as quantitative forecasts, assessments of workforce skillsets and needs, and surveys of employers and sectoral studies (Tividosheva, 2020[9]). However, skills data collection, evaluation and analysis are not comprehensive or systematically used in decision making. For example, the information generated by Bulgaria’s SAA activities sometimes lacks detail or relevance for end users, such as education and training providers seeking to update their programmes or counsellors seeking to provide advice and guidance to learners and workers. Moreover, unlike many European Union (EU) countries, Bulgaria has only recently made progress on developing a mechanism to track the labour market outcomes of VET programmes and graduates and lacks the capacity to rigorously and systematically analyse data and conduct research on VET (Bergseng, 2019[10]). While Bulgarian authorities generate a substantial and growing amount of data on skill needs and priorities at the national and local/regional levels, they could better co‑ordinate this information and use it more strategically in decision making (European Commission ESIF and World Bank, 2020[5]).

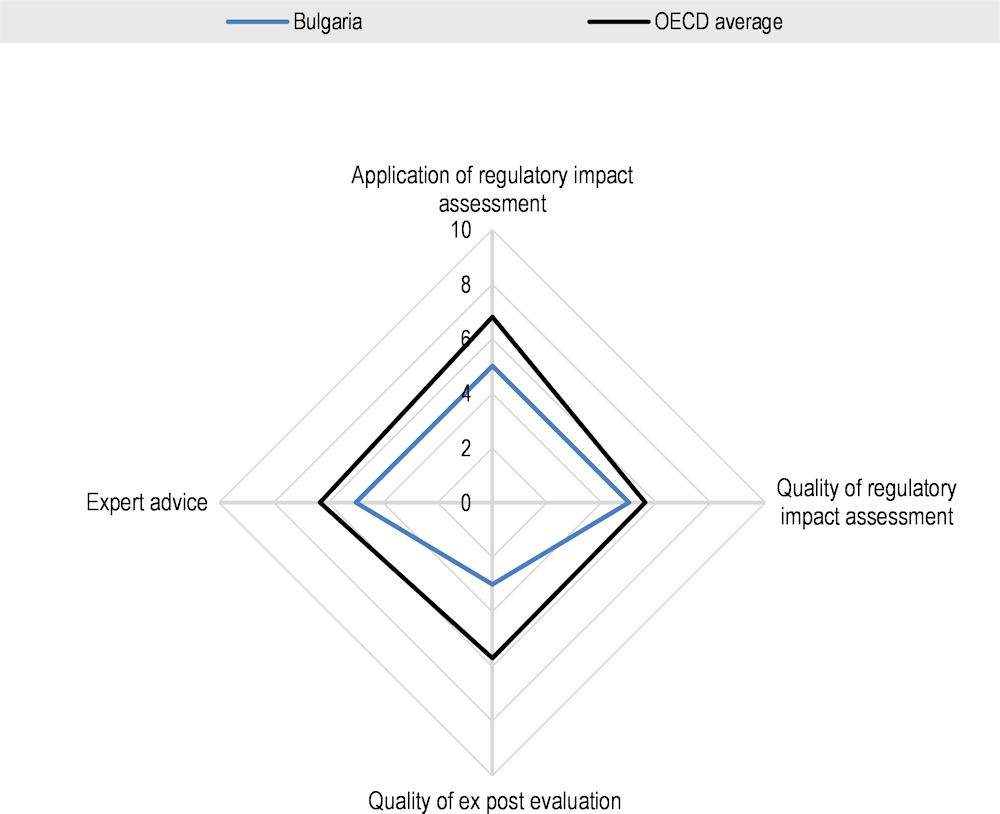

Bulgaria lacks a strong culture and practice of evidence-based skills policy making. Once again, as noted in Chapter 1, the Bertelsmann Foundation’s 2022 SGI ranked Bulgaria’s performance in key domains of overall evidence-based policy making below the OECD average (Figure 5.4). For example, Bulgaria is ranked 28th of 41 countries for the quality of ex post policy evaluations and the utilisation of expert advice (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]). The rules for impact assessments in Bulgaria, established in 2016, require an ex post evaluation of policies and their effects within five years of implementation. However, by the end of 2021, only two such evaluations had been published through the government’s public consultation portal. In addition to contracting experts to undertake evaluations, the government can consult experts for advice on policy evaluation via existing councils. However, representatives of academia and research institutes are usually included in policy consultation processes only on an ad hoc basis. It is unclear if or how often experts’ inputs in these processes are utilised.

Figure 5.4. Bulgaria’s performance in using evidence in policy making

Note: 0 is lowest, 10 is highest rating. Application of regulatory impact assessment: To what extent does the government assess the potential impacts of existing and prepared legal acts (regulatory impact assessments, RIA)? Quality of regulatory impact assessment: Does the RIA process ensure participation, transparency and quality evaluation? Quality of ex post evaluation: To what extent do government ministries regularly evaluate the effectiveness and/or efficiency of public policies and use results of evaluations for the revision of existing policies or development of new policies? Expert advice: Does the government regularly take into account advice from non-governmental experts during decision making?

Source: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022[6]), Sustainable Governance Indicators, https://www.sgi-network.org/2022/Bulgaria.

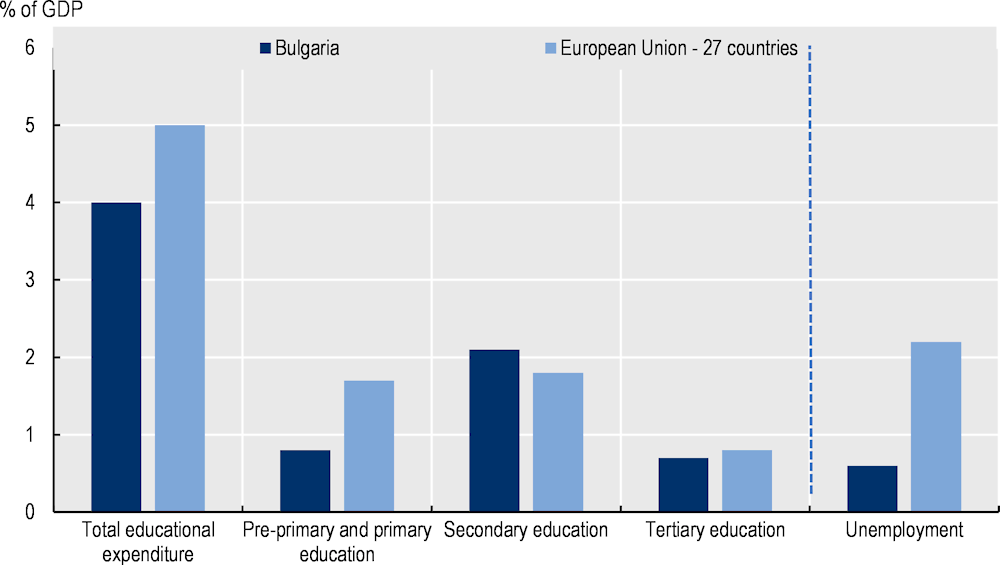

Financing arrangements

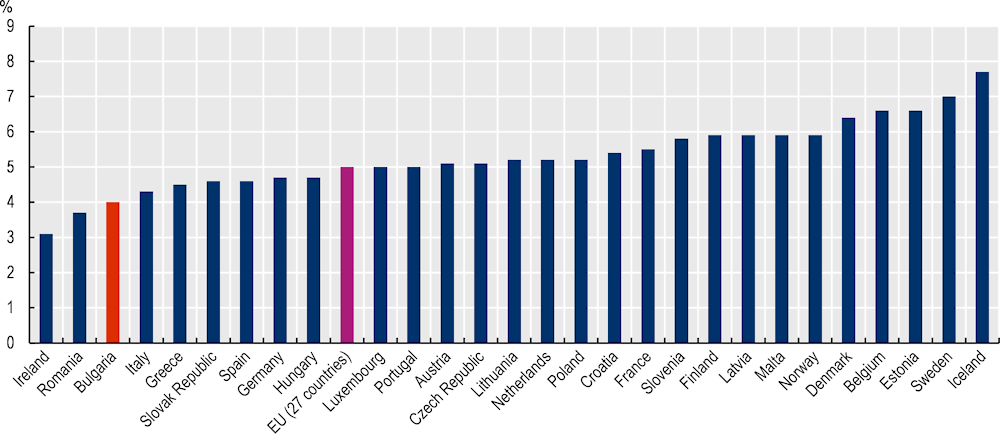

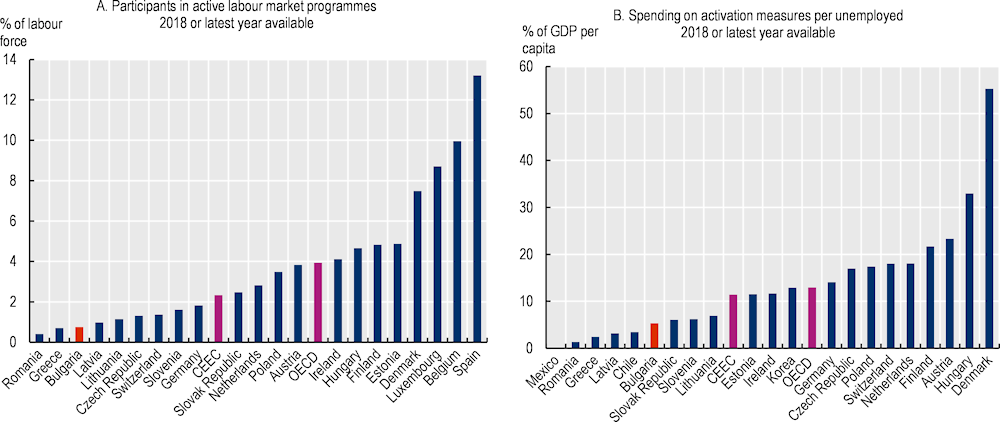

Bulgaria’s spending on skills development and use is relatively low (Figure 5.5). Total general government expenditure on education in Bulgaria was 4% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020, below the EU average of 5% (Eurostat, 2022[11]). Bulgaria’s expenditure was below the EU average at all levels of education except secondary education. Although data are sparse, public funding appears low in adult education and training, as indicated by low participation and frequent reports of financial barriers to training by individuals and enterprises (see Chapter 3). In terms of skills use, Bulgaria spends far less than the EU average on unemployment support. Spending on ALMPs for unemployed persons, in particular, is low and focused on direct employment creation programmes rather than employment incentives and training measures, which tend to be more effective (OECD, 2022[12]). Funding of skills programmes is often highly reliant on European Social Funds, which can limit the continuity of programmes as funding periods end or priorities change. In addition, there are limited cost-sharing arrangements for skills policies across ministries and with social partners.

Figure 5.5. General government expenditure on education and unemployment in Bulgaria and the European Union, 2020

Note: “Unemployment” includes: the provision of social protection in the form of cash benefits and benefits in kind to persons who are capable of work, available for work but are unable to find suitable employment; the administration, operation or support of such social protection schemes; and allowances to targeted groups for training schemes or vocational training, among other things.

Source: Eurostat, (2023[13]), General government expenditure by function (COFOG), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/gov_10a_exp$DV_578/default/table?lang=e).

Opportunities to improve the governance of the skills system

Bulgaria’s performance in governing its skills system reflects a range of institutional and system-level factors. However, three critical opportunities for improving Bulgaria’s performance have emerged based on a review of the literature, desktop research and analysis, and input from the project participants over the first half of 2022.

The three main opportunities for improving the governance of the skills systemin Bulgaria are:

1. developing a whole-of-government and stakeholder-inclusive approach to skills policies

2. building and better utilising evidence in skills development and use

3. ensuring well-targeted and sustainable financing of skills policies.

These opportunities for improvement are now considered in turn.

Opportunity 1: Developing a whole-of-government and stakeholder-inclusive approach to skills policies

Developing a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to skills policies can help Bulgaria improve its performance in developing the skills of young people (Chapter 2) and adults (Chapter 3) and in using these skills effectively (Chapter 4).

Project participants confirmed that promoting co‑ordination and co‑operation across the whole of government and with stakeholders will be critical for more effective and efficient skills policies in Bulgaria. Government engagement with stakeholders can help policy makers tap into “on-the-ground” expertise and foster support for skills policy objectives and reforms. This can also help increase collective capacity and expertise throughout the system. In addition, a whole-of-government approach to skills can create the conditions for improving and integrating skills information (see Opportunity 2) and better co‑ordinated financing (see Opportunity 3).

Strengthening inter-ministerial oversight bodies and bilateral relationships between ministries can be effective ways to strengthen whole-of-government co‑ordination on skills. Inter-ministerial bodies can be given a formal remit to supervise and guide the skills policies of different ministries to ensure overlaps and gaps are minimised and that policies complement each other. Identifying and prioritising key bilateral relationships between ministers, officials and agencies working on skills policies can facilitate formal and consistent collaboration across the policy cycle. It involves establishing clear protocols and processes for co‑operation, including in the form of partnerships, co-funding and other mechanisms. Without effective inter-ministerial oversight and relationships, skills policies risk being fragmented and ineffective.

Effectively engaging stakeholders in the skills policy-making process is critical because such a broad spectrum of stakeholders influences the outcomes of skills systems. Stakeholder engagement can occur during policy design, implementation and evaluation and ranges from stakeholders voicing their interests or concerns to taking responsibility for implementing skills policies. Effective engagement can provide important intelligence for policy makers and build stakeholders’ buy-in, all of which help to ensure the success of skills policies. For example, engaging employer representatives and trade unions during policy design and implementation, including the piloting of new initiatives, can help ensure programmes are fit for purpose for end users. Successful implementation of skills policies cannot be restricted to the government but requires co‑operation from stakeholders.

Developing a whole-of-government approach to skills policies

As noted earlier, there is evidence of fragmentation and weak co‑ordination between ministries and national agencies on skills policy development and implementation (OECD, 2019[7]; Tividosheva, 2020[9]; Ministry of Education and Science, 2021[14]; European Commission ESIF and World Bank, 2020[5]). Establishing a more effective whole-of-government approach to the skills system is therefore critical to improving co‑ordination and governance across the whole system (both horizontally and vertically).

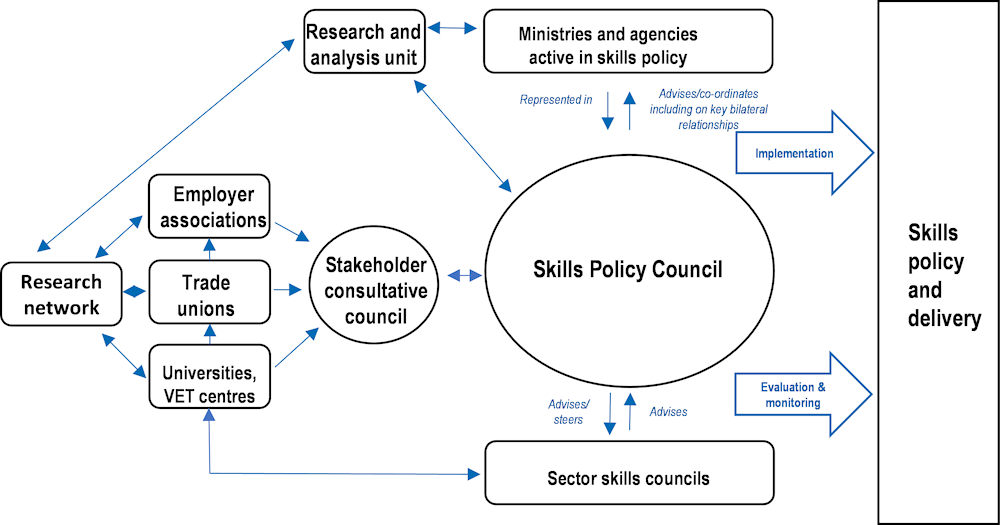

Project participants highlighted the need to develop a whole-of-government approach and shared vision for the Bulgarian skills system. At the national level, existing arrangements, such as the Council of Ministers and ad hoc bilateral co‑ordination between ministries and agencies, do not ensure that skills policies are coherent and complementary. To overcome these challenges, Bulgaria should consider forming an overarching Skills Policy Council, similar to the council introduced in Norway (Box 5.1). This council could lead and oversee policy design, implementation and evaluation across the entire skills system and help manage and co‑ordinate different actors and strategies, including those currently planned at the sector and local levels. The council could be chaired by a minister (as in Norway) or chaired by a senior official from the centre of government (as the OECD proposed for Lithuania; see OECD (2021[15])). Making it a permanent council would help to ensure continuing and much needed whole-of-government co-ordination on skills policies beyond the life of individual policies or programmes. A strengthened Consultative Council and experts should also support it (see Opportunity 2 below). Such a deliberate shift in organisational arrangements and oversight would send a clear signal within and beyond government that the effective governance of the skills system is an important priority for Bulgaria and help to increase the accountability of skills policy makers to each other and stakeholders.

Box 5.1. Relevant international examples: Developing a whole-of-government approach to skills policies

Norway: Skills Policy Council and Future Skills Needs Committee

As part of the Norwegian Strategy for Skills Policy 2017‑2021, a new governance structure was introduced in the country, at the centre of which sits the newly formed Skills Policy Council. The role of the council, established only for the duration of Norway’s current Skills Strategy, is twofold: to follow up on the strategy and to facilitate greater horizontal and vertical co‑ordination between stakeholders in Norway’s skills ecosystem. In practice, the council acts as a purely advisory body to the officials and stakeholders with responsibilities for skills, with the goal of co‑ordinating and improving existing and new skills policy measures, whether provided by government or non-government actors. The Minister of Education chairs the council, allowing council members to influence senior policy decisions.

To facilitate greater bilateral co‑ordination across ministries, the high-level discussions that take place through the Skills Policy Council (at the ministerial level or similar) are supplemented by working-level discussions at the technical level to discuss the details of concrete outputs. In particular, the Future Skills Needs Committee aims to “provide the best possible evidence-based assessment of Norway’s future skills needs, as a basis for national and regional planning, and for strategic decision making of both employers and individuals.” It undertakes short, medium and long-term skills needs assessments. In addition, the committee is expected to co‑ordinate and improve existing data creation and utilisation among all involved stakeholders and use a variety of qualitative and quantitative data sources. Future Skills Needs Committee members are representatives from social partners, the involved ministries and experts from universities.

Source: OECD (2020[16]), “Case study: Norway’s Skills Policy Council and Future Skills Needs Committee”, in Strengthening the Governance of Skills Systems: Lessons from Six OECD Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/d416bb6f-en.

Figure 5.6 sets out a potential model for configuring a Skills Policy Council in Bulgaria, including additional bodies recommended later in this chapter.

Figure 5.6. A potential model for a Bulgarian Skills Policy Council

Bulgaria should also seek to strengthen critical bilateral and/or multilateral relationships between ministries and agencies, where skills policies need to integrate with each other and related government priorities. One example of this would be the relationship between MES and the Ministry for Innovation and Growth (MIG), which could be improved to better foster the co‑ordination of strategies for skills with strategies for economic growth, innovation and research and development (R&D). Another example would be the relationship between MES and the MLSP, which could be improved to better foster the co‑ordination of policies for employment and activation (especially those aimed at minority groups and the un/under-qualified), as well as skills needs forecasting. While these examples are illustrative rather than exhaustive, the overall objective should be to increase formal co‑operation processes to facilitate a shared understanding of policy agendas and responsibilities between ministries.

Key bilateral relationships between ministries in the area of skills policy can be improved and formalised through various mechanisms. These include the creation of memoranda of understanding, jointly established and managed policy projects and delivery teams, partnership agreements between relevant delivery agencies and standing, bilateral meetings of ministers and officials, among others (OECD, 2018[17]). For example, MES and MIG could form joint project teams to design and implement skills policies supporting growth sectors and clusters. Strong bilateral relationships between ministries are likely to be (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]) more difficult and important when multi-party coalition governments appoint ministers from different political parties.

Recommendations for developing a whole-of-government approach to skills policies

Recommendations

4.1 Improve whole-of-government leadership, oversight and co‑ordination of the skills system by creating a permanent Skills Policy Council for Bulgaria. The Skills Policy Council should bring together ministries, agencies, regional and municipal representatives and key non-government actors with a stake in skills policies. The council should oversee the skills system and ensure the achievement of Bulgaria’s skills policy objectives, for example, by monitoring and reporting on skills policy implementation and outcomes. This should include oversight of existing skills bodies (e.g. the National Agency for Vocational Education and Training, NAVET) and those that are planned (e.g. sectoral skills councils). Finally, the Skills Policy Council should also oversee and publicly report on initiatives to improve stakeholder engagement (see Recommendations 4.3 and 4.4), skills needs information (see Recommendations 4.5 and 4.6), policy evidence (see Recommendation 4.7), resource allocation (see Recommendations 4.8 and 4.9) and cost sharing (see Recommendation 4.10), and any others that are defined in Bulgaria’s proposed Action Plan for Skills.

4.2 Identify and strengthen the most important bilateral inter-ministerial relationships for skills policies, including through joint projects and other formalised co-ordination actions. The Bulgarian government should identify bilateral inter-ministerial relationships critical for effective skills and related policies and seek to strengthen these relationships. This would include relationships between ministries, departments and agencies responsible for delivering whole-of-government priorities, such as boosting economic growth and productivity, managing the digital and green transitions and improving equity. These key bilateral relationships are likely to include, for example, the relationship between MES and MIG on innovation policies, and between MES and the MLSP on employment and skills forecasting. These ministries should engage in active co‑ordination measures, beginning with regular bilateral meetings at the minister and technical level, joint working groups and developing into joint projects and funding. The proposed Skills Policy Council should oversee, monitor and encourage stronger bilateral relationships between the ministries, departments and agencies involved in skills policy (see Recommendation 4.1 above).

Engaging stakeholders effectively for skills policy making

As noted earlier, Bulgaria has a growing number of consultative processes and advisory bodies for policy making that involve stakeholders and experts. These include, for example, the Council of Ministers’ portal for public consultations, as well as 70+ advisory councils (Stanchev, Popova and Brusis, 2022[4]), such as the National Council for Tripartite Cooperation, the National Employment Promotion Council and the National Council for Labour Migration and Labour Mobility (Council of Ministers, 2022[18]). Examples of stakeholders engaged through these processes include the Confederation of Trade Unions KNSB, the Confederation of Labour Podkrepa, DBBZ State Enterprise, Znánie Associations, the Association of Industrial Capital in Bulgaria, the Bulgarian Industrial Association, the Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce and the Chamber of Craft Trades, among others. Capacity and co‑operation with stakeholders has improved in some parts of the skills system in recent years, for example, in the area of SAA (CEDEFOP, 2020[19]).

However, project participants raised concerns that stakeholders are still not being fully engaged in the skills policy-making process, a challenge identified in other recent policy studies (OECD, 2019[7]). Effective co‑ordination mechanisms for involving stakeholders at all levels are still missing and/or slow to develop. In addition, research institutions and scientific/academic organisations should contribute more to SAA (CEDEFOP, 2020[19]). The government could thus better harness the insights and expertise of key stakeholders in governing the skills system.

Existing and planned advisory bodies and processes could be enhanced and/or broadened to strengthen stakeholder engagement. For example, the Consultative Council for Vocational Education and Training (CCVET) could be expanded to also cover skills development beyond school. The CCVET was established in 2018 by the Minister of Education and Science. It works on reforming and modernising VET curricula and attracting more students with high levels of skills and competencies to the VET system. The secretariat for the CCVET is the VET Directorate of MES. There is also an expert group, co‑ordinated by MES, that supports the CCVET (Box 5.2). The CCVET’s function and role could be extended to cover skills development more broadly (beyond secondary VET), for example, to include tertiary education and adult learning, including training for out-of-work adults. It could help increase capacity, evaluation and analysis across these parts of the skills system. An expanded Consultative Council could also support and advise the proposed Skills Policy Council (see Recommendation 4.1), for example, by providing research and analysis of skills issues, consolidating knowledge and data from social partners, and assisting with campaigns and communications on skills topics.

Planned sectoral skills councils could provide detailed sectoral skills insights from industry to government, including via the recommended Skills Policy Council. Bulgaria has started introducing sectoral skills councils, with a pilot in operation for manufacturing electric vehicles. Other sectors have been selected, and their key responsibilities established. Sectoral skills councils offer the opportunity to build the influence of sector-based voices in the skills policy-making and delivery process. Sectoral skills councils in Bulgaria also offer an important opportunity to better engage stakeholders at national and local levels in the design and delivery of skills policies and programmes (Box 5.2). However, ministry membership of sectoral skills councils is limited to MES, and their focus is on issues of formal VET, such as curriculum and qualifications. As with the CCVET, their remit and coverage could potentially be broadened. Poland has successfully utilised sectoral skills councils to this end, particularly in the finance sector (Box 5.3). Sectoral skills councils could report to the proposed Skills Policy Council on detailed sectoral issues, whereas an expanded Consultative Council could provide a horizontal “skills system” perspective Figure 5.6).

Box 5.2. Relevant national examples: Engaging stakeholders effectively for skills policy making

Bulgaria: Consultative Council for Vocational Education and Training

The Minister for Education and Science established a formal Consultative Council for Vocational Education and Training in September 2018. It advises on VET policy design and implementation. It also focuses on increasing demand for VET and dual training programmes in particular.

Key stakeholders at national and regional levels are represented, including other ministries, agencies, institutes and universities, non-governmental organisations, employer associations and trade unions, individual employers, local government and VET schools. A resource working group has also been established within the CCVET to carry out research and provide policy proposals. Overall, the focus is on: 1) developing a plan for VET at the secondary level; 2) developing an information and guidance model(s); 3) encouraging partnerships and developing demand for VET; 4) modernisation of VET systems, including standards; and 5) updating VET legislation.

Bulgaria: Plans for sectoral skills councils

The establishment of sectoral skills councils (SSCs) is planned in 2023 under the new Programme “Education” (2021‑2027) to be approved by the European Commission. Their key functions will include:

analysis and forecasts of labour market needs at sectoral and regional levels

updating the list of professions in VET (LPVET) and state educational standards (SES)

career guidance/consultation activities at sectoral and regional levels

supporting partnerships between vocational schools and employers

setting up training programmes and training delivery for teachers and/or mentors

monitoring the effectiveness of the VET system in meeting labour market needs.

The proposed pilot sectors for the establishment of the SSCs include: agriculture and food and drinks; textiles; wood, paper, rubber, plastics; metals and mining; mechanical engineering, electrical equipment and electric power; construction, waste management and water supply; trade; transport and storage; information and communications technology (ICT), telecommunications and creative activities; tourism; chemicals and pharmaceutical; business administration and professional services; and health and social care.

Source: CEDEFOP (2019[20]), Bulgaria: Consultative Council to lead VET reforms, www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/bulgaria-consultative-council-lead-vet-reforms; Tividosheva, V. (2020), Vocational education and training for the future of work, Cedefop ReferNet thematic perspectives series, https://doi.org/10.2801/24697

Box 5.3. Relevant international examples: Engaging stakeholders effectively for skills policy making

Poland: Sectoral skills councils

Sectoral skills councils (SSCs) in Poland were created in collaboration between the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) and business representatives in various sectors in 2016 in a variety of sectors, including health, construction, finance, tourism, fashion, ICT and automotive. The roles of SSCs include: identifying skills needs within the sector; facilitating dialogue between sectoral entities, such as employers’ organisations, trade unions, and training providers; developing strategies and plans to upskill workers and improve relevant adult education and training; determining funding priorities for sectoral training; and informing employers and employees on sector-level changes. While SSCs are responsible for co‑ordination within their respective sectors, the national Programme Council on Competences helps to co-ordinate work across the SSCs in Poland. The Council on Competences comprises 19 members, incorporating representatives from key ministries involved in Poland’s skills ecosystem.

SSCs in Poland also serve a role in implementing Poland’s national skills policy. For example, the Sectoral Human Capital Survey (an SAA survey administered to both employers and employees), which PARP, in collaboration with Jagiellonian University issues, is carried out in all sectors with the help of the sectoral skills councils. The 2016‑23 study of the survey findings includes a new sectoral perspective to understand skills needs at the sectoral level.

A particularly successful SSC in Poland is the Sectoral Council for Competencies in the Financial Sector (SSC for Finance). This SSC was initiated through a partnership between the Warsaw Banking Institute, the Polish Bank Association and the Polish Chamber of Insurance. In total, 35 entities are represented in the council, including commercial and co‑operative banks, industry organisations, higher education institutions and training companies. A representative of the Ministry of Finance participates as an observer.

The SSC for Finance is very active (and one of the most advanced among all Polish SSCs) in the implementation of the Sectoral Qualifications Framework and its inclusion in the Integrated Qualifications System, which will ensure that Polish sectoral qualifications are linked with the European market. The SSC for Finance also took an active part in the process of developing the Sectoral Human Capital Survey Report, which contains an analysis and forecast of the development trends and needs of the financial sector and a set of strategic recommendations.

Source: PARP (2018[21]), Evaluation of Sectoral Skills Councils, https://poir.parp.gov.pl/storage/publications/pdf/2018_POWER_ocena_sektorowych_rad.pdf; Fundacja Warszawski Instytut Bankowości (2018[22]), Sectoral Council for Competencies in the Financial Sector, http://rada.wib.org.pl/.

Recommendations for engaging stakeholders effectively for skills policy making

Recommendations

4.3 Strengthen and extend the Consultative Council for Vocational Education and Training to become a formal committee that works across and supports the whole skills system, reporting to and advising the Skills Policy Council. The broadened Consultative Council should include key social partners, academic experts and delivery institutions, and agencies from across the whole skills system. It should cover not only initial VET but also tertiary education and adult learning, including for out-of-work adults. The broadened Consultative Council should be responsible for supporting and advising the Skills Policy Council on policy development and implementation through information and evidence gathered from its members.

4.4 Ensure the planned sectoral skills councils include all relevant stakeholders and that they support the skills system as a whole. Bulgaria should expand the membership of SSCs to include not only MES but several ministries with responsibilities for skills. It should also consider expanding the remit of SSCs to cover issues other than VET, for example, tertiary education and adult learning, including for out-of-work adults. SSCs should be encouraged to articulate broader sectoral skills needs rather than focusing on narrower issues of curriculum, qualifications, etc. The proposed Skills Policy Council at the national level (see Recommendation 4.1) should oversee SSCs and involve them in Skills Policy Council meetings, to ensure their effective performance.

Opportunity 2: Building and better utilising evidence in skills development and use

Building and better utilising evidence in skills development and use will be integral to Bulgaria’s efforts to improve the governance and performance of its skills system. It is essential that skills policy makers, learning providers, learners and other stakeholders can make informed choices. For this, they require relevant, reliable and accessible data and information on current and future skills needs, as well as evidence on the performance of skills policies and programmes.

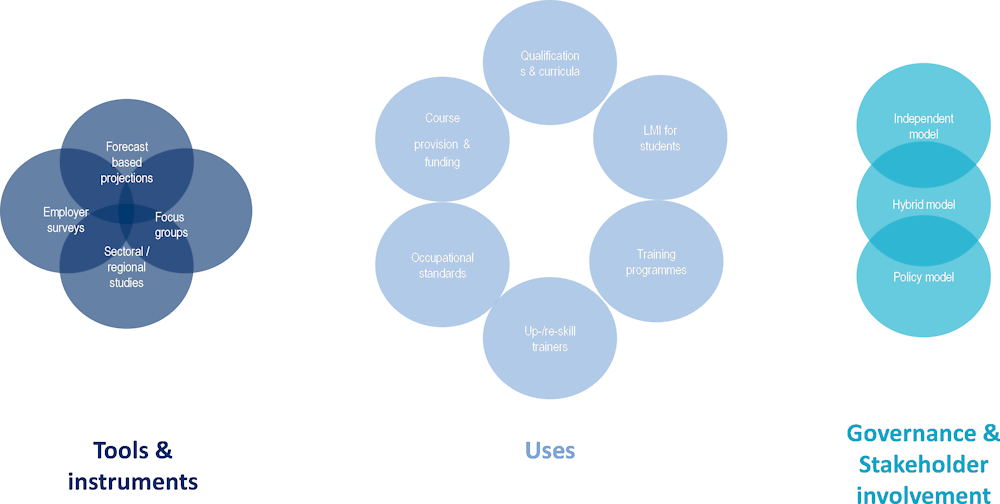

Comprehensive information on current and future skills needs is an essential building block of well-governed skills systems (OECD, 2019[1]). Effective skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) tools and arrangements are integral for producing skills needs data and information to guide decision making. Effective SAA systems typically draw on a variety of qualitative and quantitative data sources and methodologies (OECD, 2016[23]). For example, forecast-based projections and quantitative models at the national level can cover all economic sectors, ensure analytical consistency across time and sector, and are relatively transparent and objective. In addition, qualitative exercises, surveys and interviews can help policy makers collect information that is not available in datasets, while foresight exercises provide a framework for stakeholders to jointly think about future scenarios and actively shape policies to reach these scenarios.

High-quality evidence on the performance of skills policies and programmes is critical for enabling policy makers and service providers to allocate their limited resources where they will have the greatest impact. Generating evidence about what works in the skills system requires processes and capacity for evaluation and, ultimately, a culture of evaluation among policy makers (OECD, 2019[1]). Relevant, reliable and accessible skills data, information and evidence support a whole-of-government and stakeholder-inclusive approach to skills policies (see Opportunity 1), as well as targeted and sustainable skills financing (Opportunity 3). For example, a common data and evidence base can help different actors reach a shared understanding of skills challenges and opportunities. On the other hand, whole-of-government co‑ordination on skills can facilitate ministries’ identification and communication of their data needs and gaps.

Project participants expressed concerns that existing approaches for generating and utilising skills information and evidence are not performing well enough. While Bulgarian authorities generate substantial amounts of data and statistics, they could be better used to inform skill needs and priorities at both the national and local/regional levels (European Commission ESIF and World Bank, 2020[5]). More specifically, project participants and recent reports suggest that Bulgaria faces the challenges of a lack of co‑ordination of qualitative and quantitative information; limited subnational capacity to generate and utilise skills data; as well as partially outdated classifications of economic activities, professions, training courses and qualifications.

Improving the quality and use of skills needs information

Ensuring the quality and effective use of skills needs information requires effective SAA tools, instruments and governance that involve and meet the needs of diverse stakeholders (Figure 5.6). The tools and instruments used for skills anticipation in different countries vary in terms of the time span they consider, the frequency with which they are employed, the methods used to identify skill needs (i.e. quantitative or qualitative), and their national/regional/sectoral scope. The results of skills anticipation exercises can be used for a variety of purposes, including to improve labour market information for students, and inform the design and/or funding of qualifications and courses. Models for governing and involving stakeholders in skills assessment and anticipation exercises can include independent agencies such as statistical offices, universities or research institutes implementing skills assessment and anticipation exercises, public institutions doing this, or a hybrid combination of the two (OECD, 2016[23]).

SAA in Bulgaria is conducted through numerous activities, including regular the MLSP forecasts, skill assessment initiatives, employer surveys and privately funded sectoral studies (Tividosheva, 2020[9]). Central to this is the MLSP’s system for short- and long-term forecasting of employers’ demand for specific qualifications and skills based on a quantitative forecasting model and employer surveys (Box 5.4). This represents good practice in both the design of the SAA process and the analysis of SAA information.

Figure 5.7. Key components of skills anticipation systems

Source: Authors elaboration based on OECD (2016[23]), Getting Skills Right: Assessing and Anticipating Changing Skill Needs, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252073-en.

Box 5.4. Relevant national examples: Improving the quality and use of skills needs information

Bulgaria: Ministry for Labour and Social Policy employment forecasting

This exercise offers a combination of short-term and long-term forecasting of future employment levels by sector, region and occupation, based on a quantitative forecasting model and employer surveys. This forecasting practice began in 2013‑14 when the Labour Market Forecasting Model for Bulgaria was first created. The long-term model operates on an approximately 20-year period, and the shorter-term version for 2-year periods, covering 120 occupations, 35 economic activities, 28 provinces, 3 educational attainment levels, gender and 6 age groups. The current long-term forecasts apply to the 2008‑32 period and were prepared and published in 2019 by the Human Capital Partnership – consisting of Sigma Hat OOD, Global Metrics OOD and the Business Foundation for Education – on behalf of the MLSP. The forecasts are funded through the European Social Fund (ESF) and are planned to be updated annually.

This forecasting exercise has been established and offers important data and insight into future changes in the labour market. However, more should be done in future surveys and activities of this kind to support the skills system as a whole, e.g. more consideration for issues related to training, qualifications and competencies.

Source: Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, (2019[24]), Medium-Term and Long-Term Forecasts for the Development of the Labour Market in Bulgaria, www.mlsp.government.bg/uploads/24/politiki/zaetost/lmforecasts-report-en.pdf; CEDEFOP (2020[19]), Strengthening skills anticipation and matching in Bulgaria: Bridging education and the world of work through better co-ordination and skills intelligence, www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications/4188.

However, as noted earlier, skills data collection, evaluation and analysis are not comprehensive or systematically used in decision making. Bulgaria’s current forecasts are mainly designed for planning labour market policies. The information generated by existing SAA activities sometimes lacks detail or relevance for end users, such as education and training providers seeking to update their programmes or counsellors seeking to provide advice and guidance to learners and workers. For example, in VET, Bulgaria has only recently made progress on developing a mechanism to track the labour market outcomes of programmes and graduates and lacks the capacity to rigorously and systematically analyse data and conduct research on VET (Bergseng, 2019[10]). Overall, while Bulgarian authorities generate a substantial and growing amount of data on skill needs and priorities at the national and local/regional levels, they could better co‑ordinate this information and use it more strategically in decision making. Project participants largely confirmed this assessment of Bulgaria’s SAA activities.

A particular challenge for policy makers is how data on SAA is translated into the design and operation of career guidance and advisory services. Services that offer career advice to individuals – including both young people and adults (whether in work or unemployed) – and support services and advice to employers should be based on reliable, timely and relevant information on skills needs. All actors need such information to help ensure that people are able to develop skills that are in high demand.

Bulgaria could develop a more comprehensive and consolidated SAA system to serve the needs of all key stakeholders in the skills system. This would require different ministries and stakeholders to discuss and define the SAA data and information they need. The proposed Skills Policy Council, broadened CCVET and sectoral skills councils (see Recommendations 4.1, 4.3 and 4.4) could support this process. Based on this assessment, Bulgaria could improve its SAA methods and information, for example, by generating more sectoral, occupational, educational, demographic, regional and temporal insights on skills supply and demand, and utilising qualitative analysis and foresight techniques to garner insights from employers and other stakeholders. Such improved SAA information could feed into career guidance for youth (see Chapter 2) and adults (see Chapter 3). It could also be offered to employers to inform their decisions about training, hiring and other matters.

Ireland and Estonia have relatively well-developed SAA systems, which rely on a range of methodologies and sources, and produce SAA information for various users (Box 5.5). Ireland has a history of utilising qualitative and foresight techniques to test and deepen quantitative estimates of labour market needs. Estonia also has a mixed methodology approach and identifies policy implications from its SAA information as part of this approach.

Box 5.5. Relevant international examples: Improving the quality and use of skills needs information

Ireland: Skills Foresight

Ireland’s Expert Group on Future Skills Needs, established in 1997, provides strategic advice to the Irish Government on the economy’s current and future skills needs. It comprises business representatives, experts, trade unions and policy makers. In co‑operation with the SOLAS Skills and Labour Market Research Unit, it conducts its own research using a wide variety of quantitative and qualitative methods for skills anticipation. In addition, it carries out sector-specific foresight exercises using an approach that draws on interviews and focus groups with sectoral experts and actors involved in developing and using skills, including sectors such as green and digital economies.

For example, the Future Skills Needs for Enterprise within the Green Economy project explored sub-sectors of the “green economy” identified as having substantial export growth and employment potential. It aimed to provide information on the current size and skills profile of companies in the green economy; the economic, social and environmental drivers of change towards the green economy; future skills demands for occupational groups in these sectors; the adequacy of currently supplied skills; and the anticipation of future skills shortages and proactive actions required to ensure a sufficient future supply of skills. The project was based on a structured telephone survey, several workshop discussions with companies and a wider group of stakeholders, and in-depth case studies on specific companies (including company visits and structured face-to-face interviews on skill gaps and needs).

Estonia: Labour market and skills forecasting – the OSKA project

In 2014, the Estonian Qualification Authority launched the System of Labour Market Monitoring and Future Skills Forecasting (OSKA) project to map out skills provision based on labour market needs. OSKA uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to determine the skills that will be most relevant to Estonia’s future labour market. In addition to using available administrative data and quantitative forecasts to determine these skills, OSKA collects qualitative insights through sector-level surveys and expert panels to understand skills needs across five sectors. OSKA publishes annual reports on labour market trends and skills needs based on its quantitative and qualitative analyses. Beyond identifying future in-demand skills, OSKA is also involved in developing policy recommendations about how to meet the demand for these skills. OSKA is co-funded by the Estonian Qualification Authority and ESF. Non-governmental stakeholders, including education providers and business associations, are involved in the OSKA project through involvement on sectoral expert panels and/or on the OSKA Panel of Advisors, which is active in determining the methodological approach of OSKA to SAA.

Source: Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, (2019[24]), Medium-Term and Long-Term Forecasts for the Development of the Labour Market in Bulgaria, www.mlsp.government.bg/uploads/24/politiki/zaetost/lmforecasts-report-en.pdf; OECD and ILO (2018[25]), Approaches to anticipating skills for the future of work, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_646143.pdf; EGFSN (2010[26]), Future Skill Needs for Enterprise within the Green Economy, www.skillsireland.ie/media/egfsn101129-green_skills_report.pdf; EGFSN (2022[27]), About us, www.skillsireland.ie/about-us/; OECD (2020[28]), Strengthening the Governance of Skills Systems: Lessons from Six OECD countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/3a4bb6ea-en; OECD (2020[29]), OECD Skills Strategy Northern Ireland (United Kingdom): Assessment and Recommendations, https://doi.org/10.1787/1857c8af-en.

Recommendations for improving the quality and use of skills needs information

Recommendations

4.5 Develop a more comprehensive and consolidated skills assessment and anticipation approach for use by all key actors in the skills system. MES, the MLSP, the NEA, other relevant ministries and agencies, subnational authorities and social partners should collaborate to define which data and information they need from SAA initiatives. The proposed Skills Policy Council, strengthened and more broadly focused CCVET and sectoral skills councils (see Recommendations 4.1, 4.3 and 4.4) should support this process. Based on this assessment, these actors should commission experts to improve and consolidate Bulgaria’s SAA methods. For example, this should include expanding existing quantitative tools to provide more sectoral, occupational, educational, demographic, regional and temporal insights on skills supply and demand, as required by end users. It should also involve drawing on qualitative insights from consultation with employers and potentially from foresight techniques. Finally, Bulgaria should promote and monitor the use of improved SAA information by career guides/counsellors for youth in formal education (Chapter 2), adults in education and training (Chapter 3) and NEA caseworkers and unemployed adults (Chapter 4), as well as by advisors assessing enterprises’ skills and training needs (Chapter 3) and providing other business support services.

Improving the quality and use of performance data and evaluation evidence in skills policy

Related to improving SAA information, Bulgaria could also improve the quality and use of evidence on the performance of skills policies and programmes. As noted earlier, Bulgaria lacks a strong culture and practice of evidence-based skills policy making (Figure 5.4). Currently, Bulgaria has limited evidence on the outcomes achieved by its skills policies, programmes, institutions and agencies. It likely lacks the capacity and resources – human, organisational and financial – with which to collect, analyse and share such evidence (European Commission ESIF and World Bank, 2020[5]). This undermines efforts to build a shared understanding among different actors about challenges and priorities in the skills system.

Strengthening co‑ordination and leveraging analytical capacity could help Bulgaria to improve evidence on the performance of skills policies. For example, employers and trade unions currently engage in research and data collection among their members at national and regional levels. Sectoral skills councils will help increase capacity and evidence at the sector level. Furthermore, Bulgaria’s universities and various non-governmental organisations and consultancies have analytical and research capacity that could be better leveraged for skills policies. Bringing these actors and evidence together in a systematic way could enrich the skills policy-making process. Current examples of bringing skills data and capacity together are evident in the Bulgarian University Ranking System (BURS) and the Pilot Model for Tracking VET Graduates (Box 5.6). There are also examples of consortia and partnerships building evidence in the skills system, such as the Human Capital Partnership, which carried out labour market forecasts for the MLSP (Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, 2019[24]). Experts and partnerships could be leveraged in a more systematic way to build evidence and provide additional capacity for skills policy makers.

Box 5.6. Relevant national examples: Improving the quality and use of performance data and evaluation evidence in skills policy

Bulgaria: Tracking the outcomes of higher education and VET graduates

As noted in Chapter 2, the Bulgarian University Ranking System (BURS) and web portal allow users to compare and rank universities based on a range of indicators. These indicators are divided into six different categories that measure the quality of: the teaching and learning process; science and research; the teaching and learning environment; welfare and administrative services; prestige and regional importance of the universities; and graduates’ career realisation in the labour market. The Ministry of Education and the National Social Security Institute have an agreement for sharing information and regularly exchanging data to support analysis within the BURS (for labour market pathways of higher education graduates).

The same co‑operation has also helped develop a Pilot Model for Tracking VET Graduates, including the speed of labour market entry, their employment/unemployment status, their professional career, earnings (in terms of social security and tax income) and labour mobility. Administrative data and surveys are carried out in three pilot areas – Vratsa, Stara Zagora and Burgas – and cover all VET graduates in 2018. Though the VET graduate tracking survey remains a prototype, it is a promising step towards a more integrated skills information system.

Source: Bulgarian University Ranking System (2019[30]), Methodology, https://rsvu.mon.bg/rsvu4/#/methodology; Ministry of Education and Science, (2019[31]), Pilot Model for tracked VET graduates, https://mon.bg/upload/25859/model_VIREO_050421.pdf.

A potentially straightforward way for Bulgaria to improve the quality and use of evidence on the performance of skills policies and programmes would be to create a cross-government data and evidence centre. In this centre, all national and regional data, comparative country information and indicators (e.g. from international bodies such as the World Bank, the European Union, the OECD, the International Monetary Fund, the International Labour Organization and the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training [CEDEFOP]) and evaluation evidence could be collated and managed. Such a centre could be staffed with a small team that is supported with the secondments of officials and experts from across the skills system. The centre could support individual ministries and agencies, as well as the proposed Skills Policy Council (see Recommendation 4.1). The government could similarly formalise a network of experts to provide additional capacity in the skills system, building on the model of the CCVET and its resource working group (Box 5.2). The academics, consultants and stakeholders that currently collect and generate information and data on skills could be involved in such a formal network of experts and utilised to supplement the capacity of experts within the government. Denmark and Lithuania have created centres/agencies focused on improving data and evidence in the skills system, including by integrating and analysing skills data from diverse sources (Box 5.7).

Box 5.7. Relevant international examples: Improving the quality and use of performance data and evaluation evidence in skills policy

Denmark: The DREAM system

In Denmark, the DREAM project group acts as an “independent semi-governmental institution” to produce a set of simulation and projection models for the economy, from population demographics via education to the labour market. Making use of data sources available in Denmark, e.g. Danish population data, these models provide robust estimations of important development trends in the Danish economy. The microsimulation model SMILE (simulation model for individual lifecycle evaluation) is part of a set of models in the DREAM system. It draws on data from seven different data sources made available through Statistics Denmark, which allows for robust estimates on the trajectories of individual life courses, in particular, educational and employment decisions.

Being able to model these kinds of decisions enables policy makers to identify emerging skills shortages, e.g. in sectors or regions. It also helps policy makers design governance and financing frameworks in ways that ensure education institutions provide skills needed in the labour market. Finally, DREAM models also alert emerging inequalities that can inform policy responses.

Lithuania: The National Monitoring of Human Resources system and STRATA

In 2016, Lithuania launched the National Monitoring of Human Resources system, integrating existing administrative data from a variety of sources onto a singular platform, to be used for SAA. The data came from a variety of sources, including the State Social Insurance Fund, State Tax Inspectorate, Public Employment Service and Education Management Information System. In addition, the platform integrates two systems already in use in skills policy: the “qualification map”, which tracks VET and tertiary education graduate outcomes, and the “human resource monitoring and forecasting system”, which forecasts medium-term demand using Labour Force Survey data.

State authorities are obliged to use the system when making policy decisions related to education and the labour market. The platform is intended to be a tool used across ministries and other governmental bodies given that, in Lithuania, the Ministry of Education and Science, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour, the Ministry of Economy, and the Research and Higher Education Monitoring and Analysis Centre (MOSTA) are collectively responsible for SAA.

In 2017, Lithuania also restructured MOSTA into a new Government Strategic Analysis Centre (STRATA), directly reporting to the government. STRATA now fulfils general functions regarding evidence-informed policy making across all policy fields, as well as several tasks exclusive to the field of skills policy. First, its general function is to provide the government and all ministries and municipalities with support regarding evidence-informed policy making, including advice, methodological guidance, analytical support (e.g. to individual ministries as required), and evaluation. It also offers support in the preparation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of high-level planning documents (e.g. State Progress Strategy, National Progress Plan). Second, for skills policy, it provides all ministries with the information needed for evidence-informed decision making in education, science, innovation and human resource policies.

Source: DREAM (2019[32]), The Danish Institute for Economic Modelling and Forecasting, DREAM, www.dreammodel.dk/default_en.html; OECD (2021[15]), OECD Skills Strategy Lithuania, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/oecd-skills-strategy-lithuania_14deb088-en.

Recommendations for improving the quality and use of performance data and evaluation evidence in skills policy

Recommendations

4.6 Create a cross-government data and evidence centre responsible for collating and improving skills data and evaluation evidence. The government should create a centre to integrate, undertake and/or commission primary and secondary data collection, analysis and evaluation for skills policy. It should identify opportunities to improve information and evidence based on the needs defined by the government and non-government actors involved in skills policy (e.g. see Recommendation 4.5). The centre should be staffed with a small team that is supported with secondments from the ministries involved in skills policy. It should also establish formal and informal networks with experts from academia, research institutes, social partners, non-government organisations and the private sector. The centre should be governed by and report to the proposed Skills Policy Council (see Recommendation 4.1), potentially forming part of a secretariat for the council. Information and data collected and maintained by the centre should be relevant and accessible to the diverse actors with a stake in skills policy, including ministries and agencies in government, including the CCVET, the planned sectoral skills councils, municipal authorities and others (see Opportunity 1 above).

Opportunity 3: Ensuring well-targeted and sustainable financing of skills policies

Establishing financing arrangements for skills policy that are adequate, well-targeted and sustainable will be critical for improving Bulgaria’s skills performance. Project participants highlighted the importance of getting the distribution of funding right across different levels and sectors of education, ranging from general education schools, VET schools and centres, higher education and training for adults in and out of work. Given that the benefits of skills policies are most likely to be realised over the long term, funding arrangements should be sustainable over the long term.

Securing long-term funding for skills and efficiently and equitably allocating funding requires reliable and relevant evidence on current and future skills needs, the efficacy of different skills policies and programmes, and the needs of different groups of learners and workers in the population (see Recommendations 4.5 and 4.6). Allocating and targeting funding prudently (including from external sources such as EU structural funds) requires policy makers to prioritise projects that have proven particularly successful in evaluations over programmes or activities that have less impact or have become lower priority (OECD, 2019[7]). Reallocating funds is as important for system sustainability as increasing or seeking new funding.

Governments, employers and individuals play a key role in funding skills development and use. Sufficient funding for skills is essential to make societies resilient to external shocks (such as COVID‑19) and to adjust to technological and other structural changes that alter skill requirements. As individuals and employers tend to underinvest in skills for various market and behavioural reasons, governments are in a key position to sustain and steer skills development with financial incentives and long-term system co‑ordination (OECD, 2017[33]). Beyond public expenditure, policy literature also highlights many innovative mechanisms for raising the resources necessary for sustainable skills policy from non-government sources (OECD, 2019[1]). For example, cost-sharing mechanisms between the central government, employers and employees can help to meet short and longer-term costs.

Bulgaria will have significant financial capacity to invest in skills over the next decade from EU funds. Bulgaria is also set to receive substantial support from EU funds for investing in skills policies. For example, the current Partnership Agreement between the European Commission and Bulgaria allocates Cohesion Policy funds worth EUR 11 billion to the country in 2021‑27. As part of this, Bulgaria will invest EUR 2.6 billion from the ESF+ to improve access to employment, increase skills so that people can successfully navigate the digital and green transitions, and ensure equal access to quality and inclusive education and training (European Commission, 2022[34]). Bulgaria’s recovery and resilience plan allocated EUR 6.3 billion in grants under the European Commission’s Recovery and Resilience Facility. The education and skills component of this plan totals EUR 733.5 million and seeks to increase the quality and coverage of education and training and improve the skill set of the workforce to adapt to technological transformation in the labour market (European Commission, 2022[35]). Ensuring skills funding is used to its potential will require reliable skills information and evidence, and effective co‑ordination across government and with social partners.

Increasing and reallocating spending on skills development and use