Building on previous chapters’ findings, this section outlines some policy options that the Republic of Moldova (Moldova) could consider to accelerate digital business skills development, illustrated by good practice examples from OECD and EU countries. It is structured around three main objectives identified: 1) enhancing policy effectiveness through a well-defined NDS and a multi-stakeholder approach; 2) improving digital skills assessment and developing anticipation exercises; and 3) strengthening support for SMEs’ digital skills development.

Promoting Digital Business Skills in the Republic of Moldova

5. Way forward

Abstract

Objective 1: Enhance policy effectiveness through a well-defined NDS and an enhanced multi-stakeholder approach

Set clear objectives and measurable targets, and estimate costs for the new NDS

Moldova is currently preparing its new National Digital Strategy (NDS), the Digital Transformation Strategy 2023-2030, which sets the development of digital literacy as a key objective. Several actions are already foreseen, such as further improving digital skills in education systems, reducing digital divides and involving the diaspora in digital projects.

Drawing on the results of the previous NDS, Moldova could:

Broaden the scope of its approach to digital skills and include life-long learning opportunities for individuals to upskill/reskill to meet changing labour market demand. The OECD recently published a method for designing and assessing NDS (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[1]). The report lists the policy domains that such strategies should cover in order to be comprehensive, based on the OECD Going Digital Framework (see Box 3.1); these include, inter alia, SMEs, skills, labour markets, and entrepreneurship.

Moldova could also consider emphasising digital security (i.e. digital risk management and consumer protection): given the country’s shortcomings in this area, training and awareness raising could be useful for both citizens and businesses that need to develop their knowledge of these risks and their ability to manage them; ultimately, this can help build trust in digital technologies to encourage their uptake.

Finally, policy makers should keep in mind the fast-evolving environment and changes in new technologies, and therefore allow for enough flexibility for policies to be adaptable in that regard: in terms of education systems, for instance, curricula might need updates every couple of years, and schools might require new tools and equipment.

Set clear policy objectives associated with measurable targets and budgets in order to ensure effective implementation and avoid the caveats reported from the previous Strategy:

With regard to implementation, the strategy should define, for each measure, clear roles for stakeholders, as well as estimated costs, to help mobilise funding and prevent subsequent implementation failures. Box 5.1 provides guidelines for costing action plans and could help Moldova estimate the budget needed to implement the actions foreseen;

With regard to monitoring, outcome indicators should be included: for training, for instance, indicators should not only monitor the number of trainings or participants, or the volume of spending, but the extent to which the training fostered skills development. This could be done immediately after the training, e.g. through participants’ feedback or pre- and post-training assessments, and/or in the longer term, six or twelve months after completion of the training, which enables to better track if the programme helped participants get a new job, increased professional responsibilities, and/or a salary raise. This monitoring approach enables policy makers to assess not only the level of implementation, but also the concrete policy impact.

Box 5.1. Guidelines for costing of Action Plans

Definition

Costing consists of both estimating the costs involved with an Action plan’s activity and determining the financial sources needed to carry it out. It results in a costing table that compares the expenses of who and what has to be employed, commissioned, or purchased to the information on available financing. It entails the estimation of implementation costs and the planning of funding sources for each activity.

Table 5.1. Example of costing table with cost and funding categories

|

Activity |

Output target |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number and name of activity from the Action Plan |

Target indicator from the AP |

||||

|

Costs |

Salaries |

Goods and services |

Subsidies and transfers |

Capital expenditures |

TOTAL |

|

2021 |

|||||

|

Funding |

Budget |

Donor grants |

Specific loans |

Private sector |

TOTAL |

|

2021 |

|||||

|

Funding gap: |

Funding – costs |

||||

Most common costing methodologies

Bottom-up costing calculates the cost of an action by dissecting it into distinct sub-components, estimating costs of resources based on previous experience or preliminary calculations and summing them all up. This approach appears as the most sophisticated, but requires detailed knowledge of the intended activity and the unit cost for each item.

Top-down costing calculates the cost by analysing historical data and the most important technical aspects of previous identical actions. It is particularly relevant when individual cost components are unknown and cannot be estimated, but estimates are less accurate.

Analogy costing estimates the cost of an activity by taking the actual expenses of a similar activity and changing them to account for the special aspects of the intended action. Unlike top-down costing, it is based on one single, highly comparable activity.

The OECD’s guide on costing Action Plans in EaP countries suggests the bottom-up technique for estimating the cost of an activity when the necessary information is easily available. As a starting point, the cost assessment process may be divided into four parts:

1) As a first step, the activities and their respective output should be specified;

2) This allows to thereafter identify the inputs required to achieve each output;

3) Estimate the cost of each input;

4) Sum up the costs by cost categories.

Source: (OECD, 2020[2])

Broaden and strengthen participation of all relevant stakeholders in digital skills policy design and implementation

Moldova has already had successful experiences of co-operation between governmental and external stakeholders, such as ATIC, in designing and implementing digital skills policies. However, additional actors could be involved in the process – both public ones to enhance policy coherence and foster regional development, and non-governmental ones to tap into their expertise and ensure that policies meet the needs of the ultimate beneficiaries. To this end, Moldova could:

Build a whole-of-government approach. The crosscutting nature of digital skills policies demands such an all-encompassing policy approach. Considering the impact of new technologies on jobs, labour markets and social protection, digital skills policies should be designed in co-ordination and complementarity with labour market policies (OECD, 2019[3]). Moving forward, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection should therefore be more involved, to ensure synergies with the national employment strategy, for instance, and foster the reskilling/upskilling of incoming or returning migrants. The National Employment Agency could also play a role, e.g. by helping implement digital skills assessment and anticipation exercises (see below). Latvia for instance established in 2016 an Employment Council encompassing the Ministries of Economy, Education and Science, and Welfare (the latter being responsible for labour market policies and the National Employment Agency) to facilitate discussions and coordination between Ministries. This collegial and informal platform aims at promoting changes in the labour market and harmonising cross-institutional cooperation in the planning, development, implementation and monitoring of labour market reforms and skills labour market needs, and thereby reduce inconsistencies in the Latvian labour market. Moreover, bridging digital divides between urban and rural areas and spreading the benefits of digitalisation in regions is a goal linked to regional and local development policies, and thus requires the participation of regional and local authorities.

Strengthen the links with non-governmental stakeholders, who are crucial to shaping and supporting implementation of the NDS (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[1]). Policy makers need to plan consultations with actors directly affected by skills policies, i.e. employers for the private sector (OECD, 2020[4]) and teachers for education (OECD, 2019[3]). The latter can help shape policies by informing on what type of technology and related skills would be most useful, in which area(s) they would need additional training, and subsequently contribute to effective policy implementation. Indeed, the latest LMO’s survey revealed that 34% of employers deem closer co-operation with them as the priority for policy makers to gain a better understanding of the skills and competences needed to address skills gaps in the labour market (Labour Market Observatory, 2022[5]). The involvement of private sector employers can also be fostered by strengthening the co-operation with industry associations, including in non-IT sectors. The latter can share their experience to provide policy makers with a better understanding of the skills needed in the labour market and the ones young graduates tend to lack. Their involvement can be enhanced e.g. by developing Industry Expert Councils, which gather state representatives, industry associations and trade unions. Industry associations can also help implementing digital skills programmes, thereby maximising the programmes’ outreach, reducing human resources needed by the public administration, and fostering a learning culture within industries. Higher Education Institutions could also be more involved, as they can provide courses, including programmes to up-skill and re-skill workers (i.e. life-long learning); foster knowledge exchange and collaboration, e.g. via incubators and accelerators; and develop online training solutions, such as webinars and MOOCs (OECD, 2022[6]). Private training institutions can also contribute to the development of life-long learning opportunities.

Consider setting up a national digital skills coalition, in order to step up and formalise the involvement of these different stakeholders, and ensure co-ordination across the ecosystem for digital skills. The EU4Digital initiative has developed guidelines for EaP countries to establish such coalitions (see Box 5.2) and organised events around it. Moldova could build on this work and co-operation with the EU and on the willingness expressed by ATIC to launch such partnership, which would also bring the country closer to EU practices.

Box 5.2. National Digital Skills and Jobs Coalitions

Background

National digital skills and jobs coalitions were proposed by the European Commission in 2016, as part of the New Skills Agenda for Europe. These multi-stakeholder partnerships aim at helping address the increasing demand for digital skills in Europe by building a large digital talent pool and equipping individuals and businesses with relevant digital skills. To this end, they enable the facilitation of co-operation between public authorities, businesses, education, training and labour market stakeholders to shape and implement policies. Almost all EU countries have created one, usually led by an ICT business association or the Ministry in charge of innovation and digitalisation issues.

EU4Digital guidelines

The EU4Digital initiative developed actionable recommendations on how to implement such coalitions, to be established and managed in five steps:

1. Identify members;

2. Define objectives, which should be broad in scope and include digital skills policies for ICT professionals, the labour force, citizens in general, and in education systems;

3. Design an action plan, including the main objectives, key actions, related KPIs and communication plan;

4. Manage the national coalition, e.g. by remaining open to new stakeholders, sharing best practices, allocating resources to activities, and monitoring the coalition; and

5. Promote the national coalition through events, awareness raising activates at national, regional and local level, and experience sharing with other coalitions.

Members should include national, regional and local authorities, civil society representatives, education and training providers, ICT and ICT-using associations, public and private employment services, and local European office representatives. One stakeholder should be tasked with the co-ordinating role for policy planning – which could be, in the case of Moldova, the Deputy Prime Minister for Digitalisation and Ministry of Economic Development and Digitalisation, given its current leadership on digital skills policies. Alternatively, ATIC could also play this co-ordination role.

Armenia and Ukraine have already successfully implemented such coalitions, with goals in line with those of EU members.

Objective 2: Improve digital skills assessment and develop anticipation exercises

Complement existing assessments with dimensions on digital skills

Improve data collection on levels of digital skills: in order to get better insights into the current level of digital skills and the remaining gaps among individuals and firms, Moldova could widen the range of statistics collected as well as their granularity. Data on generic and complementary digital skills, especially among businesses, remain very scarce. Gathering such information, broken down by skills type, sex and firm size, would help inform policymaking and adjust both school curricula and training programmes to better meet the population’s needs. OECD and EU databases, such as the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) and Eurostat, offer useful examples of indicators that could be considered (Table 5.2). Adopting OECD methodology would also help bring the country closer to OECD and EU standards.

Table 5.2. List of selected digital skills indicators

|

Type of skills |

Indicator |

Unit of measure |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-requisite to digital skills development |

|||

|

Foundational |

Literacy |

Percentage of adults scoring high in literacy in the Survey of Adult Skills |

OECD PIAAC |

|

Foundational |

Numeracy |

Percentage of adults scoring high in numeracy in the Survey of Adult Skills |

OECD PIAAC |

|

Digital skills |

|||

|

Generic |

Adults with no computer experience |

Percentage of surveyed adults with no computer experience, by age group |

OECD PIAAC |

|

Generic |

Cloud Software Usage Skills |

Percentage of Individuals who have copied or moved files between folders, devices or on the cloud |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Installation |

Percentage of Individuals who downloaded or installed software or apps |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Software Manipulation |

Percentage of Individuals who changed the settings of software, app or device |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Video/Photo Editing |

Individuals who edited photos, video or audio files |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Individuals’ level of digital skills |

Percentage of Individuals with a certain Level of digital skills (Scale: no overall digital skills to basic or overall above basic overall digital skills) |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Usage of search engines |

Percentage of Individuals who have used a search engine to find information |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Creation of digital files |

Percentage of Individuals who have created files integrating elements such as text, pictures, tables, charts, animations or sound |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Text processing software skills |

Percentage of Individuals who used word processing software |

Eurostat |

|

Generic |

Spreadsheet processing software skills |

Percentage of Individuals who used spreadsheet software |

Eurostat |

|

Advanced |

Programming |

Percentage of Individuals who have written code in a programming language |

Eurostat |

|

Complementary |

Problem solving in technology rich environments |

Percentage of adults scoring at a given level in problem solving technology-rich environments in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) – Level 1 to 3 |

OECD PIAAC |

|

Complementary |

Fact-checking online-sources |

Percentage of Individuals who have checked the truthfulness of the information or content they found on the internet news sites or social media by checking the sources or finding other information on the internet |

Eurostat |

Source: (OECD, 2022[11]), (eurostat, 2021[12]).

Implement a digital skills framework to serve as a common reference: as highlighted above, one of the main challenges when assessing skills is the gap between formal credentials and labour market requirements (OECD, 2016[13]). Moldova has already designed a digital competence standard for students and teachers; developing such framework for digital skills tailored to labour market needs could help employers in recruiting staff and incentivise individuals to continue learning by offering them the opportunity to certify their skills (OECD, 2019[3]). This would also facilitate skills assessment by providing standards against which to evaluate competencies. The EU4Digital initiative has developed a Competence framework for SMEs in 2020, based on the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) and Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp1) (Box 5.3). Providing a dedicated methodology, guidelines on how SMEs can use the framework, and examples of job role profiles, this Framework offers a ready-to-use solution and would foster harmonisation with EU standards and across EaP countries.

Box 5.3. EU4Digital Competence Framework

Overview

This Framework has been developed in 2020 by the EU4Digital initiative to establish a common language for digital competences for SMEs. Based on EU standards, i.e. the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) and Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp), this framework entails three components:

1. a methodology to establish the Competence framework;

2. guidelines on how SMEs can use the Framework (e.g. how to develop job role profiles, recruiting advertisements, internal HR documents describing job role responsibilities and performance expectations, criteria to assess competences, and to set up competence-based learning programmes); and

3. four job role profiles (data expert, digital educator, digital transformation, and information security expert) to set an example and serve as guidelines in re-skilling and up-skilling individuals.

Objectives

Build a common understanding of competence and skills requirements, bridging the gap between education standards and labour market requirements;

Support the profiling of competence combinations and roles;

Help the assessment of competence requirements and competence gaps.

The Framework ultimately aims at supporting digital skills development among SMEs’ employees, from basic to advanced ones, and thereby to help SMEs improve their export potential, competitiveness, innovation and participation in the development of the digital market.

Source: (EU4Digital, 2020[14]), fact-finding exercises conducted in Q2 2022, including working group meetings.

Create a self-assessment tool for digital skills: self-assessment questionnaires appear as a very useful and affordable tool, not only to help respondents better understand where they stand and what they could improve, but also to provide data and insights on digital literacy levels for further analysis. Moldova has already implemented a comprehensive online self-assessment tool for SMEs to assess their level of digital maturity, including questions on their uptake and use of different digital technologies. A similar instrument could be developed for individuals, including SME managers and employees, to evaluate their digital skills and identify their needs for additional training. Several countries have implemented such tools. The Digital Skills Accelerator Online Assessment offers a good example in that regard: created by the European e-learning institute, the questionnaire covers basic and intermediate digital skills and benchmarks them against the DigComp standards. Its comprehensive and practical approach, entailing skills that are directly relevant in a professional environment, makes it relevant for both the labour force and in education systems. Box 5.4 below provides an overview of its main features and assets. Implementing such framework should be accompanied by awareness-raising activities to foster uptake. Such questionnaire is most useful when combined with tailored advice: the Digital Skills Accelerator Online Self-Assessment Tool for instance generates a list of suggested trainings depending on the respondent’s results. For firms more specifically, the assessment could be accompanied by tailored support on how to meet skills needs, to help non-digitalised businesses build a relevant strategy and navigate the training opportunities available.

Box 5.4. Digital Skills Accelerator Online Self-Assessment Tool

Overview

This online self-assessment enables users to evaluate their digital competences against the European DigComp framework, free of charge. Co-funded by the EU, it was launched in 2017 by European e-learning institute. It has since then partnered with several universities in EU member states to foster dissemination.

Features

The questions are broken down around the five DigComp competences areas, namely:

1. Information and data literacy: to articulate information needs, to locate, retrieve, store, manage and organise digital data and information;

2. Communication and collaboration: to exchange and collaborate via digital technologies, to manage one’s digital presence, identity and reputation;

3. Digital content and creation: to develop digital content and programming;

4. Safety: to understand digital security and privacy risks and threats, and act upon them;

5. Solving technical problems: to assess needs and identify, evaluate, select and use digital tools and possible technological responses to solve them.

Once all questions have been answered, the tool generates a radar chart highlighting the respondent’s strengths and weaknesses in each area. It also compares the performance with other students’ averages.

The user can then access the Learning Pathway Generator (LPG) to be provided with a list of modules/online resources most relevant to match their needs.

Strengthen skills needs anticipation practices

Further develop the labour market forecasting system to allow for more insights into digital skills, consistency, reliability, and longer-term projections: in order to strengthen its approach to skills assessment and needs anticipation, Moldova could build on its existing labour market forecasting system and on the section on skills most needed by employers introduced in the 2022 edition to gain insights into digital skills needs. In terms of methodology, the projections could go beyond the short term and entail a longer-term perspective (e.g. for the next 3, 5 and 10 years) to support multi-year policy planning. The pool of respondents could also be broadened and include a larger representation of small, medium, as well as micro firms. Moreover, replicating the methodology every year by asking the similar questions would help improve consistency and allow for comparability between years, which could ultimately feed into a quantitative forecasting model. With regard to content, the methodology could include additional layers of detail, i.e. asking questions about employers’ needs for generic and complementary digital skills, about the type of trainings firms are providing or intend to provide, and/or about foreseen investments in digital technologies. Finally, awareness of the results should be raised to ensure they are taken into account in policymaking. Latvia offers an interesting example of such a comprehensive labour market forecasting system (Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. Latvia’s labour market forecasting system

Content

Latvia’s system provides information on:

In the short-term: professions, industries, regions, and skills;

In the medium- and long-term: employment, demography, number of students, industries, education, and professions.

Structure

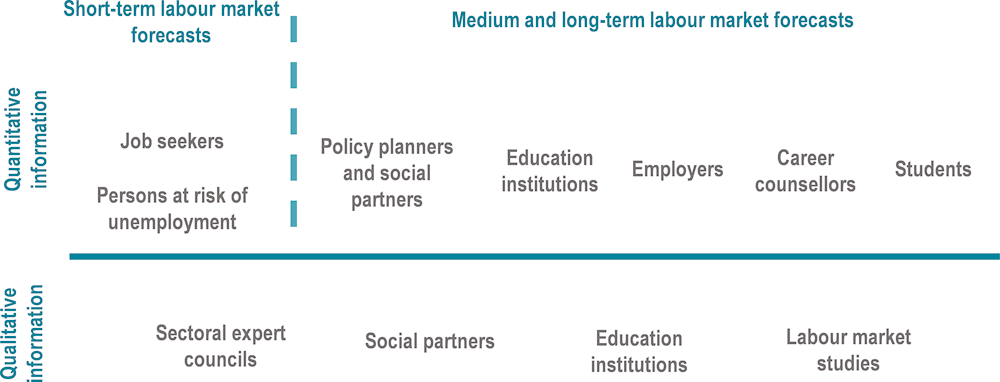

It relies on both quantitative and qualitative information: on the one hand, firms and other key stakeholders (see Figure 5.1) share their views via a dedicated form; on the other hand, the State Employment Agency of Latvia and the Ministry of Economics prepared short- and long-term quantitative labour forecasts, respectively.

Figure 5.1. Structure of Latvia’s labour market forecasting system

Source: Ministry of Economics of Latvia.

Impact

The forecasts serve as a basis for discussion between stakeholders, e.g. to adapt upskilling or reskilling initiatives. The detailed analyses produced are also disseminated on an online portal accessible by any individual: the short-term forecasts can for instance help unemployed people identify what skills they might need to develop to improve their chance of finding a job.

Source: Ministry of Economics of Latvia.

Conduct skills-need studies of selected sectors: in addition to the development of the labour market forecasting system and in view of developing skills-specific tools, Moldova could implement sectoral studies to gain insights into each sector’s specific needs for skills, including digital ones, with a common methodology applied to all sectors to avoid inconsistencies. These could take the form of skills surveys: compared to other options (see Table 3.2), surveys have the advantage of being relatively easy to develop and implement, and foster direct user/customer involvement. The approach could take inspiration from Estonia’s experience: OSKA, the Estonian anticipation and monitoring system for labour and skills demand, analyses the needs for labour and skills for the next ten years (Box 5.6). It has been conducting sectoral studies every year since 2016, for up to five sectors a year. It applies the similar methodology to all sectors, allowing for comparability, and relies on a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. One of its strengths lies in its public-private sectoral expert panels, which oversee and validate the survey results, and the follow-up on results and recommendations; this ensures that relevant measures are taken.

Box 5.6. OSKA Estonia sectoral studies of labour and skills needs

Overview

OSKA, the Estonian labour and skills forecasting system, develops projections of labour force and skills needs in all sectors of the country’s economy, and compares them to the education and training provisions available. To this end, OSKA has been conducting sectoral studies every year since 2016, for up to five sectors a year. They produce forecasts on the needs for labour and skills necessary for Estonia’s economic development for the next seven to ten years. The timeline can slightly vary from one sector to another, depending on the specificities (e.g. healthcare forecasts were produced for ten years, as the training process is longer than for other fields of study).

Process

The methodology, replicated to all sectors, is based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches – statistical data from various surveys (on labour force, education, the Population and Housing Census, sectoral surveys, etc.), and qualitative personal interviews and group discussions, respectively.

Sector-specific expert panels, composed on employers, educational institutions and policy makers and established at the Estonian Qualifications Authority, play a major role throughout the process: they oversee it, validate the results, and help ensure dissemination and follow-up.

Outcome

The results of the studies feed into policymaking: they help plan and adjust VET and university curricula, and design re-training and up-skilling projects best tailored to the working age population’s needs. For digital skills, OSKA results led, among others, to the development of financial support for digital skills development by the Ministry of Social Affairs; in-service training (over 400 different courses) on professional digital skills by the Ministry of Education; digital literacy training for employees in the industrial and healthcare sector; and software developer training courses.

Source: (OSKA, 2022[16]), fact-finding exercises conducted in Q2 2022.

Encourage skills assessment and needs anticipation at company-level: SMEs often lack awareness of the skills they need, including digital ones, and especially beyond the short-term (OECD, 2017[17]). While digitalisation programmes entailing training activities often offer preliminary assistance in identifying training needs, additional measures can help SME managers in developing internal capacity to perform such assessments. These can focus on building HR services, assessing the company’s needs, and/or improving management practices (OECD, 2021[18]). Self-assessment tools can help in that regard, but other instruments can directly incentivise SMEs to conduct regular skills needs evaluation: France, for instance, has implemented a programme for strategic workforce planning called GPEC (Forecast management agreement for jobs and skills) (Box 5.7). In place for over a decade, this instrument encourages SMEs to carry out diagnoses of their employees’ needs and to adapt their corporate strategies accordingly.

Box 5.7. France’s forward-looking management of jobs and skills (GPEC)

Embedded in the French Labour Code, this scheme called Gestion Prévisionnelle des Emplois et des Compétences was designed as a method to adapt, in the short and medium term, jobs, workforce and competences to firms’ strategies and needs.

At the company-level, it obliges firms to conduct a diagnosis of their employees’ skills every three-four years, e.g. through individual performance reviews, to encourage them to think in terms of skills rather than merely in terms of employment. The assessment is mandatory for businesses with more than 300 employees, while SMEs can benefit from state support to carry out the diagnosis.

As a result, the instrument helps managers understand the jobs required, the skills available, the gaps between jobs and skills, thereby feeding into the firm’s strategic choices, improving HR processes, and encouraging the qualification of employees. Indeed, it fosters changes within the company by helping it recruit individuals with the relevant skills; develop individual and/or collective skills (e.g. through the validation of professional experience acquired on the job (VAE) and/or training); adapt the organisation of work and production; manage the consequences of technological and economic changes; and improve career management.

Objective 3: Strengthen support for SMEs’ digital skills development

Step up training activities

Building on the considerable efforts provided by ODA and its partners over the past years, the following could increase the effectiveness of digital skills trainings:

Expand the range of topics covered by digital skills trainings: ODIMM’s (now ODA’s) previous digitalisation programme included five modules, mostly focused on helping SMEs adopt and improve e-commerce practices. The latter aims at building a basic understanding of e-commerce opportunities, but several aspects remain uncovered – such as how to connect with global value chains, how to ensure digital security, and how to be in line with the recently adopted e-commerce legislation. Training courses should not focus merely on technical skills, but should also teach participants how to implement these skills in daily routines and processes. More generally, training providers should gain a deeper understanding of SMEs’ needs (e.g. via the results of the digital maturity questionnaire, exchanges with business representatives of different sectors, as well as insights from the skills assessment and anticipation policy options outlined above) and subsequently identify priority areas for additional trainings. A sectoral approach could be considered, as SMEs show significant heterogeneity, with different tools and skills needs across sectors (OECD, 2021[20]). Training providers should also take into account the differences in skills needs between SME managers and employees when designing training offers: SME managers and entrepreneurs often lack knowledge of digital opportunities and therefore need help in designing a digitalisation strategy and identifying the most relevant digital tools, while employees lack skills to successfully implement new technologies. Complementary skills should not be overlooked, since soft skills, such as problem solving, teamwork, digital mind-set and resilience, are essential for a firm to undergo a digital transformation. Finally, access to trainings in the regions of Moldova could be further developed, as beneficiaries of current digitalisation support have been concentrated in Chișinău so far. This could be done e.g. via online trainings, or building on regional infrastructure, such as Tekwill’s upcoming regional centres.

Offer certification of competences acquired on the basis of a digital competence framework: upon completion of digital skills trainings, training providers could offer the opportunity for participants to certify the skills acquired. The digital competence framework suggested above, or the EU’s DigComp example, could serve as a basis for that. Such acknowledgment would help ensure the quality of the education received, while helping employers in recruiting qualified staff.

Ensure quality of training by strengthening monitoring and evaluation practices: in order to refine the assessment of the tools’ impact, additional outcome indicators could be considered to collect participants’ feedback on the trainings provided. This could be done via simple surveys after each training, asking the extent of skills improvements (none, partial, substantial). Alternatively, pre- and post-training assessments could be conducted to collect insights that are more objective. Following up with participants six or twelve months after completion of the training would help to capture the impact of trainings, if they helped them get a new job, additional tasks, a salary raise, and/or to perform better.

Help SMEs overcome barriers to digital skills development

Raise awareness of the range of trainings available: open and proactive communication between training providers and companies is essential to maximise the outreach and uptake, especially for SMEs, which often lack access to information. In addition to the trainings implemented by the different stakeholders, more could be done to improve the visibility of the support offered for digital skills development and to help firms and individuals navigate and select the programmes most appropriate for their needs. Various tools can be used to this end – e.g. a single information portal online, which can also help maximise the outreach in regions. Spain for instance has developed such a platform, the Acelera Pyme platform. A similar instrument could be implemented and managed by ODA, in co-operation with private sector stakeholders. Beyond trainings, the portal could gather information about digitalisation processes, sharing best practices and case studies, as well as the self-assessment tool suggested above. It could also offer the possibility to book a remote consultation with experts from ODA, which would help reach regions. Communication campaigns and/or dedicated awareness-raising events are additional options that could be envisaged to circulate information more efficiently.

Develop incentives to encourage on-the-job training: in order to help SMEs overcome their lack of internal capacity and financial means, and to foster continuous skills development, Moldova could develop support for on-the-job training. These take different forms and often rely on both financial and non-financial tools. Germany, for instance, has implemented the “Securing the skilled labour base: vocational training and education (CVET)” programme (Fachkräfte sichern: Weiterbilden und Gleichstellung fördern), which includes provisions to foster staff development and training capacity within small businesses (Box 5.8). Work-based learning is another common practice, which enable students to develop practical skills outside of school. Although these instruments do not target digital skills specifically, some of them could still be considered for future programmes to help SMEs improve their training capacity and gain a long-term strategy for human resources management and life-long skills development.

Box 5.8. Supporting on-the-job skills development: the example of Germany

Overview

The initiative “Securing the skilled labour base: vocational training and education (CVET)” programme (Fachkräfte sichern: Weiterbilden und Gleichstellung fördern) was launched in 2018 as part of the Federal government’s Strategy for security skilled workers, aiming at increasing labour force participation and better integrating women, older people and refugees in that regard. It is jointly implemented by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS), the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations, and the Confederation of German Trade Unions.

The project supports social partners and businesses in securing the supply of skilled labour by developing training structures and participation therein, staff development strategies, firms’ learning culture, as well as career advancement and opportunities.

Achievements

Benefitting from a EUR 130 mln budget, the initiative has already funded 93 projects, including ones focusing of digital skills development. Examples of conducted actions include:

Creating staff development structures: guidelines on staff development (e.g. qualification plans) and to promote learning in work processes, upgrading of managers’ skills;

Developing training advisory structures for SMEs and implementing in-house and inter-company training measures;

Fostering social dialogue on sectoral training needs and industry standards for future training and equality;

Strengthening the competences of operational actors to promote equal opportunities;

Establishing work time models and career pathway plans.

Build SMEs’ capacity and learning culture by fostering peer learning: in addition to above-mentioned training courses and advisory services, peer learning is another, non-financial means to help SME managers develop a learning culture and relevant skills beyond external trainings. Measures that combine peer learning and individual support services appear as most efficient to support investment in digital skills (OECD, 2021[18]). Moldova could therefore complement its current policy approach with initiatives to foster exchanges among managers and entrepreneurs, which could be implemented by ODA or business associations for instance. Box 5.9 provides examples from OECD countries that have delivered conclusive results. These foster direct communication between companies, but other digital tools can also be useful – an online platform to exchange virtually on learnings and ideas, such as Germany’s www.experimentierraeume.de, or an online manual of good practices promoting successful examples from selected companies, such as the cross-country project InnovaSouth.

Box 5.9. Examples of peer learning initiatives for skills development

Mentoring for International Growth programme (Italy – Turin Chamber of Commerce)

This programme, initially implemented by Turin Chamber of Commerce, fosters exchanges between entrepreneurs and managers by linking a mentor with +10 years management experience, originally from the region but living abroad and running a successful company, with a local entrepreneur (mentee), based in the country. The mentoring lasts eight months, follows ethical guidelines, and aims at improving the mentee’s firm internationalisation by sharing good practice experiences. Participation operates on a voluntary, non-paid basis, and starts with an in-person kick off meeting to ensure the right matching between participants.

The programme has encountered growing success, with the number of applicants almost doubling between the 1st and 3rd edition, and a 90% satisfaction rate. Participants reported improvements in business, marketing and communication strategies, organisational changes as well as extended networks. Such initiative could be replicated in Moldova, for the country benefits from a highly skilled diaspora.

Be the Business (United Kingdom)

Be the Business gathers large and small firms to exchange on how to improve business performance, share advice, tools and resources to increase productivity. It notably provides free business mentors and organises peer learning groups, and also offers online support and resources (stories, action plans, practical guides,…).

Another initiative, UK’s Peer Network programme, was successfully implemented in 2020-22. It organised peer learning and high impact group sessions where SME managers could exchange on their experience and identify practical solutions to tackle common challenges. Sessions were free and took place online, with experts facilitating the discussions.

Kickstart Digitalisering and coaching (Sweden)

This initiative focuses on digitalisation and bring together Swedish SMEs around a six-week series of workshops on how to go digital. It usually consists of three free-of-charge meetings during which about ten companies share experiences and ideas. It benefited 627 firms so far, of which three quarters of small firms and 70% operating in the manufacturing sector, and delivered conclusive results, with most companies starting a digitalisation project or increasing their investment in new technologies after the programme. This example has already been exported to several countries such as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

References

[24] Be the Business (2023), Be the Business, https://www.bethebusiness.com/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

[15] Digital Skills Accelerator (2021), Online self-assessment tool, https://www.digitalskillsaccelerator.eu/learning-portal/online-self-assessment-tool/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[14] EU4Digital (2020), Digital skills in the workplace: EU4Digital working on Digital Competence Framework for SMEs and microbusinesses, https://eufordigital.eu/digital-skills-in-the-workplace-eu4digital-working-on-digital-competence-framework-for-smes-and-microbusinesses/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

[7] EU4Digital (2020), eSkills: Guidelines for National Digital Skills Coalitions, https://eufordigital.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Guidelines_25052020.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

[9] European Commission (2022), National coalitions for digital skills and jobs, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/national-coalitions (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[8] European Commission (2016), Ten actions to help equip people in Europe with better skills, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_2039 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[12] eurostat (2021), Digital economy and society, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/database?p_p_id=NavTreeportletprod_WAR_NavTreeportletprod_INSTANCE_pgrsK5zx6I84&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view (accessed on 12 July 2022).

[21] Fachkräfte Sichern (2022), Initiative Fachkräfte Sichern: Home, https://www.initiative-fachkraefte-sichern.de/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

[1] Gierten, D. and M. Lesher (2022), “Assessing national digital strategies and their governance”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 324, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/baffceca-en.

[10] Horizon 2020 (2016), Commission launches Digital Skills and Jobs Coalition to help Europeans in their career and daily life, https://www.h2020.md/en/commission-launches-digital-skills-and-jobs-coalition-help-europeans-their-career-and-daily-life.

[5] Labour Market Observatory (2022), PROGNOZA PIEȚEI MUNCII PENTRU ANUL 2022 DIN PERSPECTIVA ANGAJATORILOR [LABOUR MARKET FORECAST FOR 2022 FROM THE EMPLOYERS’ PERSPECTIVE], https://anofm.md/view_document?nid=19888 (accessed on 8 June 2022).

[19] Ministry of Labour, Employment and Economic Inclusion (2021), Gestion prévisionnelle de l’emploi et des compétences (GPEC), https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/emploi-et-insertion/accompagnement-des-mutations-economiques/appui-aux-mutations-economiques/article/gestion-previsionnelle-de-l-emploi-et-des-competences-gpec (accessed on 28 April 2022).

[6] OECD (2022), Digital upskilling, reskilling and finding talent: The role of SME ecosystems. D4SME Knowledge event, 31 March 2022 - Background note.

[11] OECD (2022), PIAAC Design, https://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/piaacdesign/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

[18] OECD (2021), Incentives for SMEs to Invest in Skills: Lessons from European Good Practices, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1eb16dc7-en.

[20] OECD (2021), The Frontiers of Digital Learning: Bridging the SME digital skills gap, https://www.oecd.org/digital/sme/events/Frontiers%20of%20Digital%20Learning%20-%20Key%20Highlights%20-%20June%202021.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

[2] OECD (2020), Costing SME action plans in Eastern Partner Countries: A practical guide [Unpublished].

[4] OECD (2020), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bb167041-en.

[3] OECD (2019), OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/df80bc12-en.

[17] OECD (2017), Financial Incentives for Steering Education and Training, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272415-en.

[13] OECD (2016), Getting Skills Right: Assessing and Anticipating Changing Skill Needs, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252073-en.

[16] OSKA (2022), OSKA - Koolitused, https://oska.kutsekoda.ee/en/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

[23] Peer Networks (2022), Peer Networks, https://www.peernetworks.co.uk/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

[22] Turin Chamber of Commerce (2015), Mentoring for International Growth programme, https://www.to.camcom.it/sites/default/files/export-interna/28253_CCIAATO_2272015.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

Note

← 1. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens offers since 2013 a reference for digital competence initiatives, as well as a basis for framing digital skills policy. For more information, see https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcomp/digital-competence-framework_en.