This chapter provides an overview of the OECD approach to assessing open government in Member and Partner countries, based on the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government and the OECD Framework for Assessing the Openness of Governments. It then discusses the methodology followed by the present Open Government Review of Romania, including data collection methods, the peer review methodology and the structure of the document.

Open Government Review of Romania

3. Methodology: The OECD approach to assessing open government reforms in Romania

Abstract

The OECD approach to assessing open government

The OECD has been at the forefront of evidence-based analysis of open government reforms in Member and Partner countries for many years. The longstanding work to support countries in the adoption and implementation of access to information legislation, as well as the creation of supporting materials, such as the first OECD Handbook on Information, Consultation and Public Participation in Policy-Making (OECD, 2001[1]) as early as in 2001 are a testimony to this. With the growth of the global open government movement since the creation of the Open Government Partnership in 2011, the OECD’s work on open government and its principles got further impetus. Over the past decade, the OECD has established an ambitious programme to support Member and Partner countries that aim to foster open government through assessments and implementation assistance. Building on the OECD’s broad definition of open government (see Chapter 2), the OECD’s open government work has helped to move the global open government agenda to new frontiers by bringing a rigorous data-driven and evidence-based dimension to it.

Under the purview of the OECD Public Governance Committee, the OECD Working Party on Open Government, created in 2018, has been supporting countries around the world to strengthen their culture of open government by providing policy advice and recommendations on how to integrate its core principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation into public sector reform efforts. Over the past decade, the OECD has conducted more than 20 Open Government Reviews and Scans in Member and Partner countries, in addition to producing standard-setting reports, such as Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward (OECD, 2016[2]), Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave (OECD, 2020[3]) and The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment with International Standards and Guidance (OECD, 2022[4]).

The analytical framework for the assessment of open government policies and practices in OECD Member and Partner countries is provided by the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[5]) and specific assessment tools that are based on it, including the OECD Framework for Assessing the Openness of Governments (OECD, 2020[6]) and the OECD Openness Spectrum.

The OECD Recommendation on Open Government

On 14 December 2017, the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on Open Government (OECD, 2017[5]) (hereafter “the Recommendation”). The Recommendation presents the first and currently only international legal instrument in the field of open government. It provides governments at all levels with a comprehensive overview of the main tenets of open government strategies and initiatives to improve their implementation and impact on citizens’ lives, recognising that the principles of open government (i.e. transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation) are progressively changing the relationship between public officials and citizens all over the world.

The Recommendation responded to a growing call from countries to acknowledge the role of open government as a catalyst for good governance, democracy, trust, and inclusive growth. As data collected by the OECD revealed a diversity of definitions, objectives and implementation methodologies used to characterise open government strategies and initiatives (OECD, 2016[2]), the Recommendation responded to the need for the identification of a clear, actionable, evidence-based, and internationally recognised understanding of what open government strategies and initiatives entail.

The Recommendation contains ten provisions that cover all relevant elements of open government reforms and guide countries in their quest for more transparent, accountable, and participatory government (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. The 10 provisions of the OECD Recommendation on Open Government

RECOMMENDS that Adherents develop, adopt and implement open government strategies and initiatives that promote the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in designing and delivering public policies and services, in an open and inclusive manner. To this end, Adherents should:

1. Take measures, in all branches and at all levels of the government, to develop and implement open government strategies and initiatives in collaboration with stakeholders and to foster commitment from politicians, members of parliaments, senior public managers and public officials, to ensure successful implementation and prevent or overcome obstacles related to resistance to change.

2. Ensure the existence and implementation of the necessary open government legal and regulatory framework, including through the provision of supporting documents such as guidelines and manuals, while establishing adequate oversight mechanisms to ensure compliance.

3. Ensure the successful operationalisation and take-up of open government strategies and initiatives by: (i) Providing public officials with the mandate to design and implement successful open government strategies and initiatives, as well as the adequate human, financial, and technical resources, while promoting a supportive organisational culture; (ii) Promoting open government literacy in the administration, at all levels of government, and among stakeholders.

4. Co-ordinate, through the necessary institutional mechanisms, open government strategies and initiatives - horizontally and vertically - across all levels of government to ensure that they are aligned with and contribute to all relevant socio-economic objectives.

5. Develop and implement monitoring, evaluation and learning mechanisms for open government strategies and initiatives by: (i) Identifying institutional actors to be in charge of collecting and disseminating up-to-date and reliable information and data in an open format; (ii) Developing comparable indicators to measure processes, outputs, outcomes, and impact in collaboration with stakeholders; and (iii) Fostering a culture of monitoring, evaluation and learning among public officials by increasing their capacity to regularly conduct exercises for these purposes in collaboration with relevant stakeholders.

6. Actively communicate on open government strategies and initiatives, as well as on their outputs, outcomes and impacts, in order to ensure that they are well-known within and outside government, to favour their uptake, as well as to stimulate stakeholder buy-in.

7. Proactively make available clear, complete, timely, reliable and relevant public sector data and information that is free of cost, available in an open and non-proprietary machine-readable format, easy to find, understand, use and reuse, and disseminated through a multi-channel approach, to be prioritised in consultation with stakeholders.

8. Grant all stakeholders equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted and actively engage them in all phases of the policy cycle and service design and delivery. This should be done with adequate time and at minimal cost, while avoiding duplication to minimise consultation fatigue. Further, specific efforts should be dedicated to reaching out to the most relevant, vulnerable, underrepresented, or marginalised groups in society, while avoiding undue influence and policy capture.

9. Promote innovative ways to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions and seize the opportunities provided by digital government tools, including through the use of open government data, to support the achievement of the objectives of open government strategies and initiatives.

10. While recognising the roles, prerogatives, and overall independence of all concerned parties and according to their existing legal and institutional frameworks, explore the potential of moving from the concept of open government toward that of open state.

Source: OECD (2017[5]), “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government”, OECD legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0438, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438.

The OECD Framework for Assessing the Openness of Government

As the global open government movement has become more mature in recent years, an increasingly loud call for performance indicators to measure their contribution to broader policy goals such as trust in government and, more generally, to socio-economic outcomes has evolved. In this connection, the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government recognises “the need for establishing a clear, actionable, evidence-based, internationally recognised and comparable framework for open government, as well as its related process, output, outcome and impact indicators taking into account the diverse institutional and legal settings of the Members and non-Members” (OECD, 2017[5]).

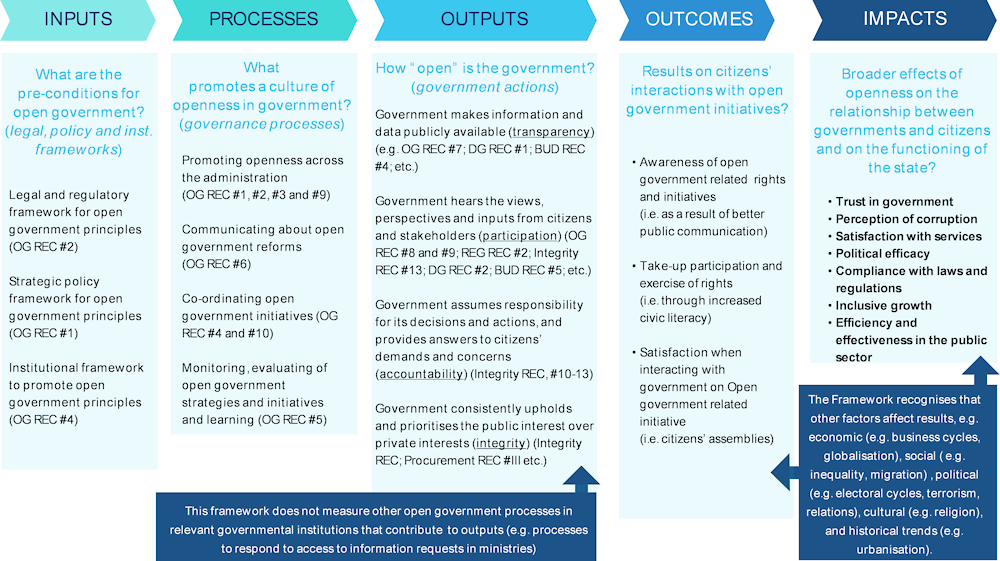

In response, the OECD Secretariat elaborated the OECD Framework for Assessing the Openness of Governments (OECD, 2020[6]), clarifying the interplays between all the elements necessary for an open government culture of governance and enabling a path towards the development of open government indicators. The result is a systematic overview of how the inputs of open government can lead to increased openness and in turn contribute to the achievement of broader policy goals, such as trust in government (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. The OECD Framework for Assessing the Openness of Government

The OECD Openness Spectrum

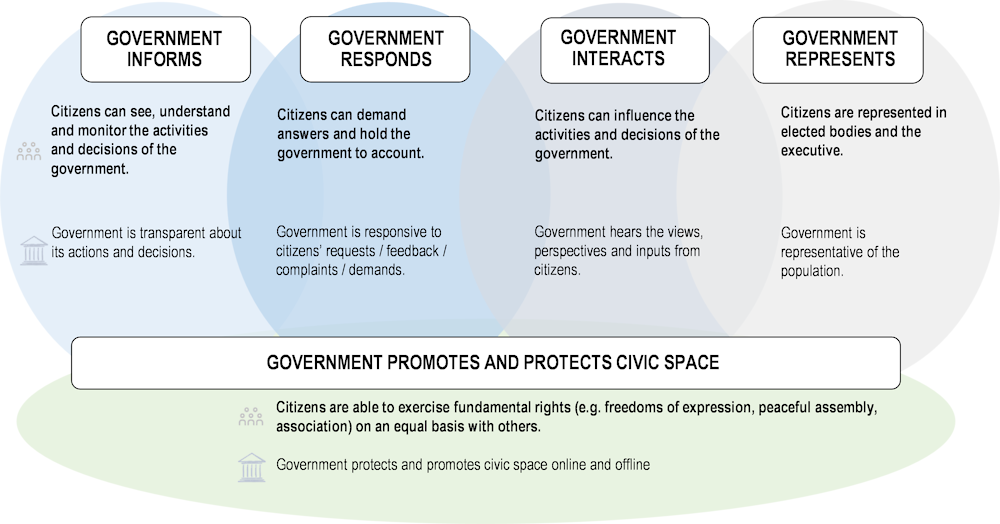

To further clarify the practical implications of the implementation of open government policies and practices (both from a government’s and from a citizen’s perspective) and to operationalise the OECD’s definition of open government (see Chapter 3), the OECD elaborated an Openness Spectrum in 2022. The Spectrum is based on five mutually reinforcing dimensions. Taken together these dimensions reflect the full breadth and depth of the concept of open government:

“How government informs” refers to the extent to which key information and data can be found, understood, used and re-used by citizens. It focuses on information that has a bearing on citizens trust in public institutions (e.g. budget information).

“How government responds” refers to key mechanisms for citizens to trigger a response from governments, whether to request public information, demand answerability on a specific public problem, or suggest a policy priority (e.g. petitions).

“How government interacts” refers to the actual interaction between governments and citizens in terms of availability, accessibility and impact of interaction mechanisms

“How government represents” refers to the representativeness of government in terms of the diversity in the composition of elected bodies and the civil service (e.g. diversity by gender, age, etc.).

“How government protects” refers to the extent to which governments protect and promote fundamental civic freedoms and political rights.

The five dimensions of the Openness Spectrum are aligned with pillar 2 on “participation, representation and openness” of the OECD’s ongoing Reinforcing Democracy Initiative (OECD, 2022[7]) and will ultimately constitute the basis for the forthcoming OECD Open, Participatory and Representative Government Index.

Figure 3.2. The OECD Openness Spectrum

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

The framework, scope and structure of the OECD Open Government Review of Romania

OECD Open Government Reviews (OGRs) support national and subnational governments in their efforts to build more open, participatory and accountable governments that can restore citizens’ trust and promote inclusive growth. OGRs are based on the ten provisions of the OECD Council Recommendation on Open Government (Box 3.1).

Open Government Reviews provide in-depth analyses of countries' open government policies and practices coupled with actionable recommendations to help embed the principles of open government in the policymaking cycle and to evaluate their impact. They usually cover multiple aspects of open government and benefit from different relevant areas of OECD work, including digital government, public sector innovation, public sector integrity, budgetary governance, territorial development, amongst others.

OGRs are developed in partnership with the requesting government and are tailored to its specific needs. Accordingly, OGRs are sensitive to the specific context, such as cultural, historical and legal specificities, and inclusive of all relevant actors outside and within government.

Box 3.2. Examples of past OECD Open Government Reviews and Scans

Open Government Scan of Lebanon

Successive Lebanese governments have taken various steps to implement reforms based on the open government principles and aligned with the OECD Recommendation on Open Government. This Scan supports the government’s efforts to build more transparent, participatory, and accountable institutions.

Open Government Review of Argentina

Argentina has undertaken an ambitious reform to move beyond open government to become an “open state”. Based on extensive data gathered from all branches and levels of government, as well as civil society, this Review assesses the progress made to date and highlights good practices. It also provides guidance on how Argentina can better align its public sector reform with the Recommendation to achieve its vision.

Open Government in Biscay

This Review is the first OECD Open Government Review carried out in a subnational government of an OECD member country. It assesses the province of Biscay’s initiatives regarding open government principles and how they impact the quality of public service delivery. This review has a focus on the implementation and the creation of a sound monitoring and evaluation system.

Open Government in Costa Rica

Costa Rica has been one of the first countries to involve the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the state in the design and implementation of its national open government agenda. This review supports the country in its efforts to build a more transparent, participatory, and accountable government as an essential element of its democracy. It includes a detailed and actionable set of recommendations to help the country achieve its goal of creating an open state.

Source: OECD (2020[8]), Open Government Scan of Lebanon; OECD (2019[9]), Open Government in Argentina; OECD (2019[10]), Open Government in Biscay; OECD (2016[11]), Open Government in Costa Rica.

A brief history of the co-operation between Romania and the OECD

Romania has been a longstanding partner of the OECD. The country has been co-operating with the OECD via thematic initiatives and a country-specific programme for many years. For example, Romania has been a participant of the OECD South East Europe regional programme since its inception in 2000 and became a Member of the OECD Development Centre in 2004 and acceded to the Nuclear Energy Agency in 2017. In recent years, Romania’s co-operation with the OECD has continued to deepen and broaden, including through greater participation in statistical reporting systems and benchmarking exercises (e.g. PISA). In 2022, the OECD Council invited Romania to start an Accession process to the Organisation.

In the area of public governance, Romania has been involved in numerous projects and Working Parties for some years. Notably, in 2016 the OECD conducted a Public Governance Scan of Romania (OECD, 2016[12]) to receive an assessment in five priority areas, namely centre of government; strategic human resources management; budgetary governance; open government; and digital government.

To achieve a more coherent, structured approach to the country’s public governance reform agenda, in 2021/2022, the Romanian government partnered with the OECD on the project Capacity building in the field of public governance - a co-ordinated approach of the Centre of the Government of Romania. The project, which is funded by the EEA/Norway grants, aims to develop public administration in five areas: co-ordination by the centre of government for SDGs, open government, digital government, public sector integrity and public sector innovation. The project aims at strengthening the capacity of public administration by providing an in-depth review of Romania’s public central administration, followed by targeted implementation support to strengthen its capacity in a sustainable manner. The present OECD Open Government Review of Romania is an integral part of this project.

Box 3.3. The OECD Public Governance Scan of Romania (2016)

The Government of Romania approached the OECD in the summer of 2016 to engage in a conversation on the country’s public governance performance and reform agenda. Five priority areas were jointly selected to analyse, namely centre of government; strategic human resources management; budgetary governance; open government; and digital government.

The primary objectives of the Public Governance Scan were to: record ongoing reform efforts; identify priorities for the near future; support and foster a national debate on sound public governance (reform).

Addressing different public governance areas, Romania’s Public Governance Scan identified specific challenges and priorities for each of the five areas. In addition, some cross-cutting challenges emerged from the Scan, notably:

the importance of considering the approval of a strategy and a legal framework in support of a specific reform initiative not as the ultimate goal, but rather as the starting point to focus on actual implementation; such a focus would also require further increased attention for soft skills related to change management, etc.

a gradual evolution towards evidence-based policymaking, including skills development in the area of policy formulation and policy evaluation

a sustained effort to connect specific reform projects (often benefiting from external funding, such as EU structural funds or others) with a broader strategy of organisational and institutional development

a logical approach to reform sequencing, optimising as such the use of the capacities and opportunities available on the ground; l appropriate institutional anchorage for organisations, coherent with their mandate and as such maximising their potential leverage

a proactive engagement of Parliament to stimulate (political) ownership of the reform agenda and foster accountability.

In terms of open government, the Scan noted “Whereas Romania possesses of some of the key legal documents (such as a Law no. 544/2001 on free access to information of public interest), as is the case in most OECD countries, it does not have an integrated open government national strategy (which is the case for about half of the OECD member countries), nor does it have a tradition of evaluating open government initiatives (which is also the case for about half of the OECD member countries). It does however have an open government co-ordination mechanism, including civil society representation”.

Source: OECD (2016[12]), Romania: Scan, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-governance-review-scan-romania.pdf.

The basis: Romania’s motivation to undergo an OECD Open Government Review

At the request of the Romanian government, the OECD Open Government Review of Romania assists the country in the implementation of more ambitious and innovative open government policies and practices. As part of the motivation to undergo the present Review, the government stressed the need for a comparative assessment of Romania’s current open government agenda and of the progress that has been reached so far in its implementation (Government of Romania, 2022[13]). Based on this assessment, the Romanian government aims to develop a strategic framework for open government. The government considers strengthening the strategic framework for open government as essential to improve the quality of open government practices, especially in regards to policy co-ordination and to the involvement of non-governmental stakeholders in public decision-making (Government of Romania, 2022[13]). Furthermore, the Romanian government requested an evidence-based assessment of past and present open government reforms to define indicators that enable the monitoring and data-driven evaluation of the impact of open government initiatives.

The scope of the OECD Open Government Review of Romania

The Review puts a particular focus on policies and practices at the level of the central government, aiming to support it in adopting, co-ordinating, implementing and monitoring and evaluating a more strategic open government agenda. Notwithstanding the focus on the central level, an open-state approach remains highly relevant to this (and all) OECD Open Government Review(s).1 All chapters take a holistic perspective on open government that – to the extent possible – includes all relevant public (and non-public) stakeholders. Therefore, the analyses make reference not only to the executive branch and its entities, but also Parliament, independent public institutions and others. Recognising that open government at the subnational/local level has its own dynamics, the Review further includes a dedicated chapter on Open State which highlights good practices from the local level, describes ways to foster the multi-level governance of open government and spotlights areas of opportunity for an Open Parliament.

The complementarity with other ongoing OECD reviews

Due to the ongoing Civic Space Review of Romania (OECD, 2023[14]), which is implemented in parallel, the present Review does not include a specific chapter on the protection and promotion of civic space. Rather, it includes cross-walks to the main findings of the Scan, whenever relevant. Ultimately, the Open Government Review and the Civic Space Review of Romania should be read in conjuncture as they provide an integrated assessment of the wider open government ecosystem in Romania. In particular, the Civic Space Review of Romania’s chapter on citizen and stakeholder participation (Chapter 6) has been co-drafted by two teams and should be seen as a key part of the present publication.

The Review further refers to the main findings and recommendations of other ongoing OECD policy reviews in Romania, including the OECD Digital Government Review, the OECD Innovation Scan and the OECD Integrity Review. For example, the Digital Government Review assists Romania in its digital transformation and covers issues related to open government data, while the Integrity Review discusses elements relating to asset disclosure, lobbying transparency, and whistle-blower protection which are also of relevance to the present Review.

The methodology and evidence of this Review

OECD Open Government Reviews are based on extensive data collection efforts and sharing of best practices from peer countries. They are presented to the OECD Working Party on Open Government and the OECD Public Governance Committee, thereby providing for peer review and contribution to endorsement of the recommendations by the OECD membership.

For the OGR of Romania, the OECD Secretariat benefitted from the following sources of evidence: extensive desktop research, the OECD peer review, questionnaires and surveys, as well as two fact-finding mission(s).

The involvement of OECD peer reviewers

OGRs involve peer reviewers from OECD Member and Partner countries that are experts in the field of open government. They share their experiences and enable a peer dialogue. Throughout the process, this Review benefitted from the input of peer reviewers from:

Chile: Ms Valeria Lübbert Álvarez, Executive Secretary of the Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency, Government of Chile.

Scotland: Ms Doreen Grove, Head of Open Government, Government of Scotland.

Spain: Ms Clara Mapelli, Director General for Public Governance, Government of Spain.

The OECD Secretariat and the GSG selected the peer reviewers in close co-ordination. The selection was based on the experiences Chile, Scotland and Spain had with respect to their countries’ open government agenda and the value added this experience presented to Romania. The concerned public officials kindly volunteered for their involvement.

The three peer reviewers were constantly engaged during the collection of evidence and the drafting of this Review. They actively participated during the interviews conducted during the fact-finding missions (see Interviews below) and provided feedback on findings and recommendations. With their comments, they enriched the present analysis from a practitioner’s perspective.

Questionnaires and surveys

The present Review benefitted from the data collected through different Surveys. First, it reflects Romania's answers to the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government – a questionnaire that monitors the implementation of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government and that was answered by over 50 countries. Secondly, the General Secretariat of the Government – based on a detailed qualitative questionnaire on open government policies and practices in Romania that was prepared by the OECD Secretariat – provided an extensive Background Report in March 2022. Additionally, three targeted surveys were sent out to different types of stakeholders (Table 3.1), namely:

Public institutions that are part of the executive branch.

Sub-national governments at both state and municipal levels.

Non-public stakeholders (academics, civil society, private sector, etc.).

Table 3.1. Surveys conducted for the Open Government Review of Romania

|

Type of stakeholder |

Data collection period |

Responding institutions |

|---|---|---|

|

Central government |

April – May 2022 |

1. Court of Accounts of Romania (Curtea de Conturi a României) 2. Ministry for Family, Youth and Equal Opportunities (Ministerul Familiei, Tineretului si Egalitatii de Sanse) 3. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Ministerul Agriculturii si Dezvoltarii Rurale) 4. Ministry of Culture (Ministerul Culturii) 5. Ministry of Defense (Ministerul Apararii Nationale) 6. Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration (Ministerul Dezvoltării, Lucrărilor Publice și Administrației) 7. Ministry of Economy (Ministerul Economiei) 8. Ministry of Education (Ministerul Educatiei) 9. Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Tourism (Ministerul Antreprenoriatului si Turismului) 10. Ministry of Environment (Miniaterul Mediului, Apelor și Pădurilor) 11. Ministry of Finance (Ministerul Finanțelor) 12. Ministry of Health (Ministerul Sanatatii) 13. Ministry of Interior (Ministerul Afacerilor Interne) 14. Ministry of Justice (Ministerul Justiţiei) 15. Ministry of Labor and Social Solidarity (Ministerul Muncii și Solidarităţii Sociale) 16. Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization (Ministerul Cercetării, Inovării şi Digitalizării) 17. Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure (Ministerul Transporturilor si Infrastructurii) 18. National Agency for Equal Opportunities for Women and Men (Agenția Națională pentru Egalitatea de Șanse între Femei și Bărbați) 19. National Agency for Public Procurement (Agenția Națională pentru Achiziții Publice) 20. National Institute of Statistics (Institutul National de Statistica) 21. National Supervisory Authority for the Processing of Personal Data (Autoritatea Națională de Supraveghere a Prelucrării Datelor cu Caracter Personal) 22. Permanent Electoral Authority (Autoritatea Electorală Permanentă) |

|

Subnational government |

April 2022 |

1. Municipality of Arad 2. Municipality of Bacau 3. Municipality of Botosani 4. Municipality of Brasov 5. Municipality of Buzau 6. Municipality of Calarasi 7. Municipality of Campia Turzii 8. Municipality of Campina 9. Municipality of Craiova 10. Municipality of Focsani 11. Municipality of Galati 12. Municipality of Hunedoara 13. Municipality of Municipality 14. Municipality of Piatra-Neamț 15. Municipality of Ploiesti 16. Municipality of Ramnicu Sarat 17. Municipality of Ramnicu Valcea 18. Municipality of Roman 19. Municipality of Sibiu 20. Municipality of Slatina 21. Municipality of Slobozia 22. Municipality of Suceava 23. Municipality of Targoviste 24. Municipality of Zalau |

|

Non-public stakeholders |

April – May 2022 |

1. Association for Liberty and Gender Equality (Asociația pentru Libertate și Egalitate de Gen) 2. Babeș-Bolyai University 3. Center for Independent Journalism (Centrul pentru Jurnalism Independent) 4. Center for Public Innovation (Centrul pentru Inovare Publică) 5. Centre for Education and Human Rights Association (Asociatia Centrul pentru Educatie si Drepturile Omului) 6. CIVICA Association (Asociatia CIVICA) 7. Făgăraș Research Institute (Institutul de Cercetare Făgăraș) 8. H.appyCIties 9. Independent expert, Anse Info 10. National Alliance of Romanian Student Organisations (Alianța Națională a Organizațiilor Studențești din România) 11. National Trade Union Confederation (Confederaţia Naţională Sindicală Cartel ALFA) 12. Reality Check Association 13. REPER Association for Management by Values (Asociația REPER pentru Management prin Valori) 14. Roma Education Fund (Fondul pentru educația romilor) 15. Romanian Business Leaders 16. Romanian Federation of Community Foundations (Federatia Fundatiile Comunitare Din Romania) 17. Save the Children Romania (Organizatia Salvati Copiii Romania) 18. The Future of Youth Association (Asociația Viitorul Tinerilor) 19. Smart City Association (Asociatia Smart City) 20. Transparency International Romania 21. University of Bucharest |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Interviews and fact-finding missions

As part of the Review-process, the OECD conducted two peer-driven fact-finding missions. The first mission took place from 4 to 8 July 2022 in Bucharest, while the second fact-finding mission was organised in a virtual setting and took place from 5 to 12 September 2022. All interviews were held under Chatham House rules. In total, the OECD conducted interviews with 30 stakeholders and with a length of 60-90 minutes each (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Fact-finding mission and follow-up interviews

|

Type of interviewee |

Name of affiliated institution |

|---|---|

|

Central government |

1. Authority for the Digitalization of Romania 2. Chancellery of the Prime Minister 3. Department for Information Technology and Digitalization, General Secretariat of the Government 4. Department of Relations with Public Authorities and Civil Society, Presidential Administration 5. Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration 6. Ministry of Finance 7. Ministry of Justice 8. National Agency of Civil Servants 9. National Institute of Administration (INA) 10. Officials in charge of participation in law-making selected Ministries: Ministry of Labor and Social Solidarity, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization 11. Open Government Service, General Secretariat of the Government 12. Service for Cooperation Policies with Civil Society, General Secretariat of the Government |

|

Subnational government |

1. Alba Iulia Municipality 2. Bucharest City Hall (Primarul General al Municipiului București) 3. Bucharest, Sector 2, City Hall 4. Cluj Municipality 5. Iasi Municipality 6. Timisoara Municipality |

|

Other public stakeholders |

1. Ombudsman (Avocatul Poporului) 2. Petitions and Hearings Department within the Registry and Archives Office, General Secretariat of the Chamber of Deputies 3. Public Relations Department in the Office for Public Information and Relations with Civil Society, General Secretariat of the Chamber of Deputies |

|

Non-public stakeholders |

1. Academic, University of Bucharest, and member of OGP Steering Committee 2. Funky Citizens 3. Institute for Public Policy 4. H.appy cities 5. Romanian Business leaders 6. Expert Forum Association 7. Center for Public Innovation 8. Academic, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj 9. Academic, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

The structure of the OECD Open Government Review of Romania

This Review reflects all Provisions of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government through its different chapters.

Chapter 1: Assessment and Recommendations provides an integrated overview of the main findings included in the Review. It presents key information further developed in the following chapters, and highlights the main recommendations for Romania to consider in the short, medium and long term to strengthen policies and practices in terms of transparency, accountability and citizen and stakeholder participation and, ultimately, reinforce democracy and build citizens’ trust in public institutions.

Chapter 2: Setting the scene: The context and drivers for open government in Romania provides an overview of the context and drivers that frame the implementation of open government policies and practices in Romania. It discusses socio-economic and political challenges, such as low levels of trust in government and frequent changes of government and presents the history of open government reforms in the country.

Chapter 3: Methodology: The OECD approach to open government reforms in Romania provides an overview of the OECD approach to assessing open government in Member and Partner countries. It then discusses the methodology followed for the Open Government Review of Romania, including its framework, scope and structure.

Chapter 4: Implementing the legal framework for open government: Towards a more transparent and participatory government in Romania discusses the main laws, regulations and international treaties underpinning open government reforms in Romania. In addition to outlining rights and obligations, it puts a particular focus on the implementation of the legislative framework in the areas of transparency and citizen/stakeholder participation.

Chapter 5: Creating an enabling environment for an Open Government Strategy in Romania supports Romania in the creation of governance structures and mechanisms that are suitable for a holistic and integrated open government agenda and that can facilitate the successful implementation of the country’s first holistic Open Government Strategy. The chapter starts by discussing Romania’s current institutional framework and co-ordination mechanisms for open government. It then focuses on ways to build an open government culture in the Romanian administration and in society and discusses means to foster public communications around open government policies and practices.

Chapter 6: Taking a strategic approach to open government in Romania: Towards an Open Government Strategy aims to support Romania in the process to design, implement, monitor, and evaluate its first holistic and integrated policy to foster the government-citizen nexus. Finding that there is a need for a more holistic and integrated approach to open government in Romania, the chapter provides targeted recommendations aiming to facilitate the preparation for the design and the process to draft an Open Government Strategy. It further discusses mechanisms that facilitate the operationalisation and implementation of the Strategy.

Chapter 7: Monitoring and evaluating openness: Towards stronger impact of open government reforms provides an assessment of Romania’s current efforts to monitor and evaluate open government policies and practices. The chapter provides recommendations to strengthen ongoing efforts and outlined an agenda to monitor and evaluate the upcoming Open Government Strategy, including through the design of an Open Government Index and/or an Open Government Maturity Model.

Chapter 8: Towards an Open State in Romania analyses Romania’s move towards an open state, i.e. the implementation and co-ordination of open government initiatives and strategies at all levels of government and in all branches of the state. It finds that some municipalities are championing open government at the subnational level, and that these efforts could be harnessed with a strategic framework and through additional support from the central level. The chapter also assesses the implementation of transparency and participatory initiatives in Parliament. It concludes with a roadmap to build an open state in Romania.

The chapters complement each other. While Chapters 4 and 5 mainly discuss existing inputs and processes for open government in Romania, Chapter 6 on the Open Government Strategy focuses on providing a roadmap moving forward. Chapter 7, in turn, outlines how a more integrated open government agenda could be monitored and evaluated, while Chapter 8 analyses how this agenda could involve the other branches of the state and all levels of government.

Definitions of key terms used in this Review

|

Access to information (ATI) |

Refers to the ability of an individual to seek, receive, impart, and use information effectively. In public administration, access to information refers to the existence of a robust system through which government information is made available to individuals and organisations. |

|

Accountability |

A relationship referring to the responsibility and duty of government, public entities, public officials, and decision makers to provide transparent information on, and be responsible for, their actions, activities and performance. It also includes the right and responsibility of citizens and stakeholders to have access to this information and have the ability to question the government and to reward/sanction performance through electoral, institutional, administrative, and social channels. |

|

Central/Federal government |

The central/federal government consists of all government units having a national sphere of competence, with the exception of social security units. The political authority of a country’s central government extends over the entire territory of the country. The central government can impose taxes on all resident institutional units and on non-resident units engaged in economic activities within the country. Central/federal government typically is responsible for providing collective services for the benefit of the community as a whole, such as national defence, relations with other countries, public order and safety, and for regulating the social and economic system of the country. In addition, it may incur expenditure on the provision of services, such as education or health, primarily for the benefit of individual households, and it may make transfers to other institutional units, including other levels of government. |

|

Citizen |

The term is meant in the larger sense of ‘an inhabitant of a particular place’, which can be in reference to a village, town, city, region, state, or country depending on the context. It is not meant in the more restrictive sense of ‘a legally recognised national of a state’. In this larger sense, it is equivalent to people. |

|

Citizen and stakeholder participation |

Includes all of the ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the policy cycle and in service design and delivery through information, consultation and engagement. |

|

Civic space |

The set of political, institutional and legal conditions necessary for citizens (see “citizen”) and civil society to access information (see “access to information”), speak, associate, organise and participate in public life. |

|

Civil Society Organization (CSO) |

Encompasses all non-market and non-state organisations outside of the family in which people organise themselves to pursue shared interests in the public domain. In general, CSOs share a number of common characteristics: they are organised (i.e. they possess some institutional structure); they are separate from government; they are non-profit-distributing; they are self-governing; and they are voluntary, at least in part (i.e. they involve some meaningful degree of voluntary participation, either in the actual conduct of the agency’s activities or in the management of its affairs). The term includes trade unions, charities, consumer groups, associations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), foundations, and other groups. Government representatives, legislators, think tanks, academia and media are not CSOs. |

|

Data |

The term refers to recorded information stored in structured or unstructured formats, which may include text, images, sound, and video. |

|

Effectiveness |

The extent to which the activity's stated objectives have been met. |

|

Efficiency |

Achieving maximum output from a given level of resources used to carry out an activity. |

|

Independent public institutions |

Refers to institutions that are mandated by national laws to oversee their correct implementation, especially by the central/federal government. These are de-jure independent from other state/public institutions (meaning that they can conduct their mandates without undue regard for the views of other state/public institutions). |

|

Levels of government |

Refers to central and sub-national levels of government |

|

Non-public stakeholder |

Any interested and/or affected party (see “stakeholder”) which is not from the government or any of its related public entities. Examples included in the survey are citizens, members of CSOs (see “CSOs”), journalists, citizens (see “citizen”), journalists, bloggers, members of political parties, members of the private sector or business associations, trade unionists, academics, human rights defenders, activists. |

|

Open government |

A culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth. |

|

Open government agenda |

The ensemble of open government strategies and initiatives in a country. |

|

Open government initiatives |

Actions undertaken by the government, or by a single public institution, to achieve specific objectives in the area of open government, ranging from the drafting of laws to the implementation of specific activities such as online consultations. |

|

Open government literacy |

The combination of awareness, knowledge, and skills that public officials and stakeholders require to engage successfully in open government strategies and initiatives; |

|

Open Government Partnership (OGP) |

An international partnership between governments and civil society to promote open government. Eligible national and subnational governments can become a member. More information is available here: www.opengovpartnership.org |

|

Open government policies |

Strategic documents that aim to promote open government principles. |

|

Open government principles/ principles of open government |

Refers to the principles of transparency (see ‘Transparency’), integrity (see ‘public integrity’), accountability (see ‘Accountability’, and stakeholder participation (see ‘Citizen and stakeholder participation’). |

|

Open government strategy |

A document that defines the open government agenda of the central government and/or of any of its sub-national levels, as well as that of a single public institution or thematic area, and that includes key open government initiatives, together with short, medium and long-term goals and indicators. |

|

Open state |

When the executive, legislature, judiciary, independent public institutions, and all levels of government - recognising their respective roles, prerogatives, and overall independence according to their existing legal and institutional frameworks - collaborate, exploit synergies, and share good practices and lessons learned among themselves and with other stakeholders to promote transparency, integrity, accountability, and stakeholder participation, in support of democracy and inclusive growth. |

|

Policy cycle |

The policy cycle includes 1) identifying policy priorities 2) drafting the actual policy document, 3) policy implementation; and 4) monitoring implementation and evaluation of the policy’s impacts. |

|

Policy document |

Refers to a document that outlines decisions, plans, and actions that are undertaken to achieve specific goals. An explicit policy can achieve several things: it defines a vision for the future which in turn helps to establish targets and points of reference for the short and medium term. It outlines priorities and the expected roles of different stakeholders; and it builds consensus and informs people. |

|

Public institutions |

Refers to all legislative, executive, administrative, and judicial bodies, and their public officials whether appointed or elected, paid or unpaid, in a permanent or temporary position at the central and subnational levels of government. It can include public corporations, state-owned enterprises and public-private partnerships and their officials, as well as officials and entities that deliver public services (e.g. health, education and public transport), which can be contracted out or privately funded in some countries. Together, these institutions form the public sector. |

|

Public sector integrity |

The consistent alignment of, and adherence to, shared ethical values, principles and norms for upholding and prioritising the public interest over private interests |

|

Public stakeholder |

Any interested and/or affected party (see “stakeholder”) from the government or any of its related public entities. |

|

Stakeholders |

Any interested and/or affected party, including: individuals, regardless of their age, gender, sexual orientation, religious and political affiliations; and institutions and organisations, whether governmental or non-governmental, from civil society, academia, the media or the private sector. |

|

Subnational government |

Includes both state and local governments.

|

|

Transparency |

The disclosure of relevant government data and information in a manner that is timely, accessible, understandable, and re-usable. |

References

[13] Government of Romania (2022), Background Report prepared for the OECD Open Government Review of Romania, (unpublished working paper).

[14] OECD (2023), Civic Space Review of Romania, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f11191be-en.

[7] OECD (2022), Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy: Preparing the Ground for Government Action, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/76972a4a-en.

[4] OECD (2022), The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment with International Standards and Guidance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d234e975-en.

[6] OECD (2020), A Roadmap for Assessing the Impact of Open Government Reform, Paper presented to the OECD Working Party on Open Government, GOV/PGC/OG(2020)5.

[3] OECD (2020), Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en.

[8] OECD (2020), Open Government Scan of Lebanon, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d7cce8c0-en.

[9] OECD (2019), Open Government in Argentina, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1988ccef-en.

[10] OECD (2019), Open Government in Biscay, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e4e1a40c-en.

[5] OECD (2017), “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government”, OECD legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0438, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438.

[11] OECD (2016), Open Government in Costa Rica, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265424-en.

[2] OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

[12] OECD (2016), Romania: Scan, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-governance-review-scan-romania.pdf.

[1] OECD (2001), Citizens as Partners: OECD Handbook on Information, Consultation and Public Participation in Policy-Making, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264195578-en.

Laws and regulations

Parliament of Romania (2001), “Law no. 544/2001 on free access to information of public interest”, OFFICIAL MONITOR no. 663 of October 23, 2001, https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/31413.

Note

← 1. The OECD defines an open state as “when the executive, legislature, judiciary, independent public institutions, and all levels of government - recognising their respective roles, prerogatives, and overall independence according to their existing legal and institutional frameworks - collaborate, exploit synergies, and share good practices and lessons learned among themselves and with other stakeholders to promote transparency, integrity, accountability, and stakeholder participation, in support of democracy and inclusive growth” (OECD, 2017[5]).