This chapter explores talent attraction and retention policies as a means for public authorities to meet regional labour and skills needs. It provides insights into effective strategies, emphasising the importance of tailoring approaches to specific territories and individual talent needs. Recognising the significance of non-work and non-pecuniary factors, it presents quantitative findings indicating that fast Internet speeds, affordable housing and hosting international students are effective levers for talent attraction and retention. Furthermore, it showcases examples of successful practices implemented at the subnational level that target specific talent groups, such as graduates and public servants. In conclusion, the chapter provides a six-step roadmap for regional governments to address co‑ordination gaps and strategically position their region for talent attraction and retention in an evolving global landscape.

Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in the New Global Environment

5. International talent attraction and retention

Abstract

Key messages

Public authorities are taking steps to help employers attract and retain talent

With accelerating labour and skills shortages in most parts of the economy, public authorities are increasingly investing in helping their employers attract and retain talent.

Talent, which includes more than the rich and highly educated, increasingly chooses to live in places that fit its personal perceptions of an attractive living environment.

Attraction and retention strategies should be tailored to places and people

Because all territories do not need the same talent, attractiveness and retention strategies should be place-specific.

Because all talent does not desire the same things, attractiveness and retention strategies should be people-specific.

The importance of retention strategies cannot be overstated, including as a lever to attract newcomers. People’s first experience of a place plays a significant role in determining longer-term stays and their willingness to spread the word to others, meaning that soft landing schemes are key.

Housing and broadband are of utmost importance to international talent

Regions with access to fast Internet speeds, affordable housing and that host a higher share of international students are more attractive to international talent. These factors are fundamental to a region’s development trajectory, showing that talent attractiveness strategies can be direct levers for regional development.

Regional governments can follow the OECD six-step roadmap to design and implement effective strategies to attract and retain talent in the new global environment.

What is shifting the regional playing field for talent attraction and retention?

Skills and labour shortages

Human capital is widely considered fundamental for economic growth. Broadly defined as the stock of knowledge, skills and other personal characteristics that make people productive, it is a prerequisite for the proper functioning of businesses and public services (Égert, de la Maisonneuve and Turner, 2022[1]). Past levels of regional human capital are found to be key in explaining current regional disparities in innovation and economic development (Diebolt and Hippe, 2022[2]; Gennaioli et al., 2012[3]). However, shortages of adequate human capital – also referred to as labour and skills shortages – were already a problem across many parts of the OECD before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has only made the shortages far more evident (Business Europe, 2022[4]). Therefore, when considering territories’ long-term resilience and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic compounded by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, besides energy, commodities and inputs, the lack of workers with the right skills is proving to be the next great challenge facing countries and regions (Causa et al., 2022[5]).

Declining and ageing populations lead to a number of challenges for regions, including labour and skill shortages. Over the coming decades, the population is expected to decline in half of all OECD countries (OECD, 2022[6]). Declines of 10% or more in the working-age population have been forecast in 1 out of 4 European Union (EU) regions (EC, 2023[7]). Obstacles to human mobility across countries also explain these shortages. In the European Union, the rate of increase in those emigrating has decelerated in recent years, partly because companies and workers face barriers in hiring/taking up employment across borders, including lengthy and costly legal procedures, and a lack of easily accessible information (Business Europe, 2022[4]).

Labour and skills shortages are felt globally but rural, remote and underserved areas are being hit the most (EC, 2023[8]). Therefore, in several cases, intranational inequalities in human capital are larger than international ones (Diebolt and Hippe, 2022[2]). In Germany for instance, the eastern states are more heavily affected by shortages than those in the west, due to a high exodus of workers since 1990. In 2021, 27.7% of companies in the east (including Berlin) reported to be suffering from skills shortages (Volk, 2021[9]). In France, future recruitment difficulties should be particularly acute in southern and western regions: Brittany (42% of employment under increasing pressure by 2030), Pays de la Loire (36%) and New Aquitaine (33%) (Dares/France Stratégie, 2023[10]). Conversely, the Île-de-France region has the lowest proportion of jobs under increasing pressure (11%) due to its younger population. Any exacerbation of these territorial inequalities, risks provoking important economic, social and political divides.

All sectors are impacted by labour force shortages, albeit to a different extent. The sectors most affected include construction, accommodation and food services, manufacturing, retail trade, transport/warehousing, as well as leisure and hospitality (ELA, 2021[11]). The healthcare sector is also not immune, with projections indicating a global shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030 (WHO, 2022[12]). In all cases, rural, remote and underserved areas are expected to experience the greatest shortages. In Canada, despite unemployment rates being historically low, many positions remain vacant, particularly in healthcare (Statistics Canada, 2022[13]). According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022[14]), employment opportunities for nurses are projected to grow at a faster rate (9%) than all other occupations from 2016 through 2026. In Germany, more than 35 000 healthcare positions were unfilled at the end of 2021 (+40% within a decade). Faced with these shortages, the use of foreign workers is extensive. One in five practising physicians in Germany was born abroad, while since 2004, the share of foreign nurses in the Belgium capital city of Brussels has more than doubled. In France, the government is considering implementing a new multi-year residence permit called “Talent – medical and pharmaceutical professions”1 to attract foreign doctors. Yet, the increasing reliance of foreign health workers may exacerbate health workforce shortfalls, particularly in poorer regions and as such precautions must be taken. In Greece for instance, where there is a shortage of health workers, many choose to go abroad or into the private sector (Stroobants et al., 2022[15]).

Labour shortages exist at all skill levels, albeit to a different extent, and must be filled to ensure the sustainable development of countries and regions. For labour markets to return to pre-pandemic strength will require new workers of all levels, skills and diplomas, in a variety of sectors with structural shortages and associated technicalities (tourism, hospitality, information technology [IT], health, logistics, etc.). A lack of workers with relevant skills in the construction, energy, manufacturing and transport sectors, to name a few, could also risk holding back the green transition in places that would then fall behind (Kleine-Rueschkamp, 2022[16]; OECD, 2023[17]). In Copenhagen, Denmark, talent attraction is now defined as the driving force behind the green transition.

Redefining “talent” is essential to address staffing problems at the regional level. Currently, in the migration schemes of most OECD countries, talent relates only to highly educated people or entrepreneurs. However, changes to who are considered talent, are emerging for instance in Japan and the European Union. OECD work on talent attractiveness at the national level has focused on national immigration policy reforms and differentiates between three types of talented migrants: highly educated workers, entrepreneurs and university students (OECD, 2023[18]). Definitions focusing on individual intrinsic features are useful but are not fit for purpose for this current OECD work on Rethinking Regional Attractiveness, which is focuses on overall regional resilient and inclusive development and is not limited to positions requiring highly educated candidates.

For the purposes of this activity, talent is defined as anyone with skills corresponding to the needs of public and private, place-specific economic and social development strategies (Flood et al., forthcoming[19]). This approach factors in the evolving global environment and specific territorial needs. It enables a break away from the binary approach that sees people as low- or high-skilled, with diplomas from universities of varying quality, with low or high salaries, and enables a greater focus on local labour markets and the needs of communities. People with basic skills are essential to the smooth running of any economy, as highlighted by the COVID-19 containment. The COVID-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine should be seen in this light as an opportunity, or a wake-up call, that may provide the required stimulus at the policy and research levels to investigate further how this new dimension of human capital can shape future regional development in Europe (Diebolt and Hippe, 2022[2]).

The need to attract international talent

Two main strategies must be combined to bring more people into the labour market and effectively address labour and skills gaps: first, by (re-)engaging and training people who find themselves on the sidelines of the labour market, such as women, retired individuals and others; second, by increasing the labour force through immigration. Given that growing labour market needs cannot be fulfilled in the long term by mobilising the domestic workforce alone, focusing on attracting and retaining talent from abroad is essential (EC, 2023[8]). While this report supports countries and regions in that regard, training and developing the skills of the local workforce is also crucial.

Local governments have a role to play in attracting and retaining people. Central governments are responsible for granting foreigners the right to participate in the labour market and, as such, many are amending their legislation to facilitate their entry and are investing in schemes to validate their professional and educational qualifications. At the same time, local authorities have responsibilities in key areas such as childcare, education and social housing (OECD, 2022[20]) that allow them to develop – and many do – effective strategies to attract and retain newcomers (OECD, 2018[21]).

What do effective talent attraction and retention strategies look like? Because not all territories need the same talent and not all talent has the same requirements, strategies should be place- and people-based. First, a place-based approach ensures strategies build on the specific regional assets and opportunities as well as actors of the territory they support. The heterogeneous location of labour and skill gaps, and the unique reasons for their existence, mean that a one-size-fits-all solution will not work (Eurochambres/Committee of the Regions/OECD, forthcoming[22]). Moreover, territorial instruments can help engage local actors – public sector as well as firms, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), civil society and residents alike – to identify and agree on the priorities to address and thus support better social cohesion and democracy by increasing ownership of policies and creating communities of common interest (EC, 2023[7]). This is key given that anti-immigration perceptions vary from one place to another (Charbit and Tharaux, 2021[23]) and have been found to drive away immigrants, including within the European Union (Di lasio and Wahba, 2021[24]) and that, overall, citizens increasingly question globalisation (OECD, 2022[25]). Second, a people-based approach will help policies focus on the needs of the talent the region would like to attract, identify under which conditions they are likely to relocate and propose tailored solutions. According to individual socio-demographic characteristics, the different components of attractiveness considered by the OECD will have different weights in localisation decisions. For instance, having good access to childcare services will be capital for families, while access to high-speed Internet will be decisive for remote workers.

Box 5.1 The role of culture in talent attraction

Culture and creative industries transform local economies and communities in various ways and foster talent attraction and retention. Cultural policies are thus increasingly being used to promote destinations and enhance the attractiveness of places. Culture can breathe new life into decaying neighbourhoods and culture-led investments have proliferated in cities and regions across the globe (OECD, 2022[26]). An often-cited example is that of the city of Bilbao, which experienced transformative regeneration after the Guggenheim Foundation opened a museum in the city (González, 2010[27]). Moreover, there is growing evidence that increased levels of cultural participation have positive effects on well-being and health as well as encourage social cohesion by supporting the integration and inclusion of marginalised groups (OECD, 2022[26]). Cultural hubs and policies to make culture accessible to all can therefore be decisive in attracting and retaining people – in particular women, students and highly educated people who tend to have higher levels of cultural participation (Schmutz, Stearns and Glennie, 2016[28]; Falk and Katz-Gerro, 2015[29]).

The city of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, is a promising case of a municipal-level initiative that supports arts and culture as a means of building more attractive and vibrant communities. Over the last decade, it has developed a strong cultural investment policy, recognising the important role that cultural activities and events can play in enhancing the quality of life for residents and attracting visitors to the city (City of St. Catharines, 2023[30]). While the town only has 140 000 inhabitants, it is home to several performing arts venues, various festivals and events and numerous public art installations that enhance the urban landscape. In 2023, the city launched its Culture Builds Community programme, designed to support local artists and cultural organisations, by providing funding for community-based arts and culture projects.

Source: OECD (2022[26]), The Culture Fix: Creative People, Places and Industries, https://doi.org/10.1787/991bb520-en; González, S. (2010[27]), “Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’. How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism”, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010374510; (Schmutz, Stearns and Glennie, 2016[28]). Falk, M. and T. Katz-Gerro (2015[29]), “Cultural participation in Europe: Can we identify common determinants?”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-015-9242-9; City of St. Catharines (2023[30]), Arts, Culture and Events.

Non-work and non-pecuniary factors, play an important role in attracting talent. In the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic and as developed countries increasingly rely on immigration as a source of workforce stability, there is a demand for a new assessment of the determinants of talent attraction, one that takes into account the evolving characteristics and aspirations of the global workforce that is more mobile and has more choice of where to locate (ICMPD, 2021[31]). The OECD has developed a tool presented in Chapter 3 to help regions identify the assets at their disposal to leverage for the purposes of talent attraction and retention. It considers more than 50 indicators to develop regional attractiveness profiles, covering 14 dimensions of attractiveness, across 6 domains (economic attraction, connectedness, visitor appeal, natural environment, resident well-being, land use and housing). Beyond the potential job opportunity itself, non-work and non-pecuniary drivers can be the deciding factors when considering employment options – particularly when job opportunities are equal. These drivers include access to high-speed Internet, affordable housing, natural capital, social cohesion but also the quality of public services (transport, health, and education), leisure activities and local cultural offerings (OECD, 2022[25]) (Box 6.1). Regions attractive to talent, visitors and investment appear to either host a higher share of international students or a top 500 university, suggesting a potential policy synergy between the internationalisation of education and attractiveness.

Moreover, the growth of teleworking in some professions is an opportunity for non-metropolitan territories with few job offers to attract new inhabitants. Indeed, increasing numbers of workers can live where they want, with companies like Airbnb, IBM, JP Morgan, PwC, Revolut, Salesforce, Siemens, Spotify, Walmart and Zillow, to name a few, having decided to go fully remote, thus making location decision less constrained by the workplace and mainly determined by regional well-being factors. Attracting teleworkers and their families will require significant investment in order to adapt to their needs, first and foremost to provide adequate digital infrastructures (e.g. broadband Internet and digital hubs) (OECD, 2023[32]).

The uneven impacts of climate change on regions can boost non-metropolitan territories’ attractiveness. Urban areas may become less attractive as places to live as they tend to be warmer than their surroundings due to high building concentration, reduced ventilation and lack of vegetated areas (OECD, 2022[6]), exposing residents to both higher temperatures and more intense heatwaves than their rural counterparts. The intensity of this urban heat island effect varies across cities across the OECD, depending on the population size and the climate zone. Built-up lands in urban areas with a population size higher than 250 000 inhabitants are already, on average, 3°C higher than their surrounding area, which is almost twice that for urban areas with less than 100 000 inhabitants. Given heatwaves have significant health impacts and will continue to grow in frequency, intensity and duration, they could increase the attractiveness of rural areas, as people strive to resettle to milder climates (Marcotullio, Keßler and Fekete, 2022[33]).

What works for talent attraction and retention

In response to a lack of depth in the local talent pool, many private and public actors have developed proactive plans to attract and retain talent, with a particular focus on talent from abroad. This section presents six levers used by subnational authorities to target specific talent groups: graduates, women, the diaspora, remote workers, families and public servants. Quite often, strategies tackle only one or two of the domains of attractiveness identified by the OECD as driving attraction and retention (connectedness, natural environment or others). Yet multifaceted approaches addressing the various factors that influence location decisions are needed for territories to become places where people want to work, live and play. Moreover, the focus is often only on attracting new people and efforts to ensure the smooth reception and integration of those that come are overlooked. Yet people’s first experience of the place plays an enormous role in their staying prospects and their willingness to spread the word to others. If they are happy, they will gladly communicate this to their peers, meaning that retention is becoming the new attraction (Andersson, 2023[34]).

Retaining graduates

Former international students are an important feeder of labour migration in many countries (OECD, 2022[35]). They benefit the local economy by starting businesses, taking on high-skilled jobs and adding to the talent pool. Over the last decade, OECD countries have implemented wide-ranging policies to retain international students after completion of their degree. In particular, international students can remain in the country upon graduation to look for a job in almost all OECD countries (OECD, 2022[36]). Some regions encourage students to stay after graduation by developing high-quality job opportunities, often in collaboration with other local actors. One such initiative is the Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTP) started by Dalarna University in Sweden in 2012 (OECD, 2023[37]). The KTP enable recent graduates to obtain one-two-year contracts with local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to carry out strategic development projects. It meets a real need since top reasons stated by international students for staying in Sweden after graduation are “long-term career opportunities” and “employment after graduation” (a high salary scores significantly low) (Future Place Leadership, 2022[38]). The programme is co-funded by the participating companies, the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (via the European Regional Development Fund, ERDF) and the region in which projects take place. Given that a vast majority of KTP contracts lead to full‑time recruitments, the programme has allowed to address labour shortages and to attract young talent to Dalarna County. The “Lombardia is research and innovation” law2 implemented by the Italian region also aims to facilitate the entry of young talent, particularly researchers, into employment through better co‑operation between companies that need innovation and the research sector, to prevent them from leaving the region (EU, 2018[39]). It should be noted that attracting students themselves is also a good way to establish a pipeline of talent to fill local needs following graduation.

Attracting and retaining women

It is critical to pay attention to the available levers to attract and retain women, considering their role in promoting the sustainable and inclusive development of places. In particular, recent OECD work has underlined their over-representation in jobs that are essential for societies to function smoothly. For instance, across OECD countries, over 70% of workers in education and over 75% in health and social work are women. This is particularly stark in long-term care, where women hold more than 90% of the jobs across OECD countries (OECD, 2023[40]). These “pink-collar” jobs proved vital during the pandemic but are often underpaid, undervalued and lack clear opportunities for career advancement. They face stark attractiveness challenges that must be tackled partly by focusing on quality-of-life aspects. In Europe, data reveal gender differences in out-migration trends from rural areas. More women leave rural areas to study in tertiary education compared to men and tend to not return (Șerban and Brazienė, 2021[41]).

To (re)attract and retain women, some non-metropolitan areas are taking steps to improve diversity and inclusivity, such as the city of Asheville, North Carolina, United States, which established a Women’s Roundtable that brings together female leaders from various sectors to identify and address issues affecting women in the community, such as sexual assault and domestic violence. Providing opportunities for social and civic engagement can also help foster the diversity of voices being heard. The region of South Karelia, Finland, has implemented a programme called Women’s Active Citizenship that provides training and support for women to participate in local government and decision-making. The city of Strasbourg in France has embarked on gender budgeting, with the aim of integrating this dimension into all policies in order to reduce gender inequalities. The approach is supported by the European Commission in the framework of a dedicated programme, in which Strasbourg participates, alongside five states and three Länder. The municipal administration is accompanied by international experts and financially supported for two years. In the field of citizen participation, the city has, for example, begun to offer childcare facilities at neighbourhood meetings, and has introduced equal opportunities to speak.

Attracting back the diaspora

Attracting members of the diaspora back to their home region can be critical for regional development and economic growth since people bring with them valuable skills, knowledge, experience and international connections. The implications are even more vital for rural areas. In Portugal, return migration has been found to increase the sustainable development of deprived areas through investments in the local/regional tourism industry (Santos, Castanho and Lousada, 2019[42]). Overall, historical patterns show that few people have moved to a new region they have no connection with, so targeting returnees might be the easiest way to bridge labour and skills shortages. Therefore, most of the world’s top migrant-sending countries and many subnational authorities have policies encouraging the return of the diaspora, making this group one of the most targeted by attraction policies. Policies vary from providing financial incentives to initiatives to build a sense of community. For instance, the Romanian Diaspora Start-up programme co‑financed by the European Social Fund provides grants to small-scale businesses registered by Romanians returning home (EC, 2023[8]). In co‑operation with news channels and broadcasters, the Polish government has launched the “We are 60 million” campaign, to disseminate, through social media, radio and television, information about the benefits of returning to the country (Paavola, Rasmussen and Kinnunen, 2020[43]).

In Spain, a national Return Plan was approved in 2019 by the Spanish government but several initiatives to attract returning citizens started and continue at the subnational level. The Castilla-La Mancha government launched the first of its kind in 2017: the Return of Talent programme. It includes a job-finding website, a team of mediators to facilitate the return and the following three key strands: subsidies for employers hiring people coming back to the country; subsidies for the start of entrepreneurial activity; and a “return” passport opening a right to a grant covering expenses associated with the transfer from abroad. The first two subsidies are 20% higher when carried out in certain municipalities and priority areas. About 40 regional officers are dedicated to this policy within the central co‑ordination team and in the employment offices of Castilla-La Mancha. Since its launch, 749 have applied, 332 have returned with a job and 18 with an entrepreneurial project. As for the Cantabria region, it engages and strengthens ties with its diaspora through Casas de Cantabria (Houses of Cantabria), whose multipurpose cultural spaces also organise exhibitions, concerts, film screenings, recreational activities and attend to any inquiries relating to the region (OECD, 2023[44]). In Italy, the Marche region is planning to support self-employment projects in the region conducted by returning talent and by offering incentives to businesses for hiring local-born workers living abroad.

Attracting remote workers

Attracting remote workers can have multiple benefits for regions. It can stimulate economic growth by bringing income into the area, increase diversity and the talent pool for employers and provide workers with a better work-life balance. Therefore, in 2022, 6 OECD countries and at least 22 non-OECD countries offered visas specifically for digital nomads (DNVs), which allow foreign workers to stay in the country and work remotely for a company abroad (OECD, 2022[35]). The growing flexibility to work and live from anywhere opens new opportunities for more rural communities to attract people sensitive to their assets (natural amenities, affordable housing, etc.) who might otherwise be deterred by a lack of jobs. For this to take place, the availability of high-speed Internet and/or coworking spaces is capital (OECD, 2023[32]).

Airbnb’s new functionality allowing hosts to test their Wi-Fi speed and add the results on their listing page is a good illustration of remote workers looking for connected places. If many top digital nomad destinations are still in big cities, “nomad villages” are now starting to emerge, usually formed via a collaboration between local governments and one or more entrepreneurial organisations. The island of Madeira in Portugal quickly adapted to the increased mobility of workers, to target remote workers. Since 2021, they can apply to the Digital Nomads Madeira programme, launched as a pilot project, and obtain the right to live and work in Madeira for up to one year. The pilot brings together the local government, local hotels, real estate, workspaces and car rental companies to offer newcomers a place to live, work and play. On the island, Digital Nomad Villages are being rolled out to serve as a one-stop-shop to help nomads settle. They get access to guidance on finding accommodation, free coworking spaces and join the social media group where events are posted every week. Since it opened, 4 670 nomads have arrived on the island. Algarve in another Portuguese region that has also been actively promoting itself as a remote work destination and has made related investments. However, the arrival of remote workers can lead to increased housing costs (as is the case in the city of Lisbon, for example), pressures on local infrastructure such as roads or public transport, and a weakening of the local culture leading to tensions between local residents and newcomers, and increased negative environmental impacts such as energy consumption, waste production and carbon emissions. There is therefore considerable interest in monitoring how newly implemented digital nomad visa schemes develop over time and assessing whether and how negative externalities should be mitigated by place-based policies.

Attracting and retaining families

An increasing number of attractiveness programmes focus on families that are a significant part of the economy, contributing to the labour force and consumer markets, creating job opportunities, expanding local tax bases and contributing to sustaining diverse communities, local events and volunteering. Families are also a direct way to maintain public services in a region suffering from out-migration since they tend to use a variety of available services (education, health including maternity, job services, etc.).

Jobs for spouses. OECD research confirms the importance of designing attractiveness and retention strategies that consider the needs of the whole family (OECD, 2023[45]). Large metropolitan areas are often more attractive to dual-career couples because of the greater number of job opportunities. To tackle this issue, in France, the Family Support Programme from the Ministry of Armed Forces offers, among other services, military spouses job opportunities in various public sectors as well as internships and professional training to acquire new skills and improve their employability, thereby alleviating some of the challenges and uncertainties faced by military families due to frequent moves and deployments, and improving their quality of life (OCDE, forthcoming[46]). In Sweden, similar regional initiatives are available. For example, In Dalarna, private and public sector employers have joined forces (Rekryteringslots) to make recruitments more lasting and offer “job matching” for the entire family of the originally recruited employee (OECD, 2023[37]). Similarly, the Job-for-Both project, launched by a local development company Samarkand2015, offers language courses to partners of new foreign recruits, as well as individual coaching to help them find a job or start a business, speed dating opportunities with employers, and assistance with inter-cultural communication, etc. (OECD, 2023[37]).

Safety for children. When thinking about moving somewhere, parents consider how safe and healthy the place is for their children. Therefore, regions and cities have implemented different programmes aimed at making communities safer for kids. The state of Oregon, United States, provides resources and funding to schools and communities to help them create safe and accessible routes for children to walk and bike to and from school.

Health for all. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, migrants may also put more emphasis on the resilience and performance of health systems in their decision-making process, in particular families. The Lisbon metropolitan area has been active in improving the population’s satisfaction with health by building new Family Health Units and upgrading primary healthcare infrastructures and equipment. These projects will benefit more than 300 000 users and were supported by the 2014-20 EU funds (OECD, 2023[47]). Most centres also offer other services such as nutrition or psychology consultations. The province of Ontario, Canada, has implemented the Healthy Kids Community Challenge, which encourages communities to develop programmes and initiatives that promote healthy eating, physical activity and other healthy behaviours among children.

Attracting public servants

Public servants are essential to the development and delivery of any public programme or service, and for well-informed policies to be designed and implemented. Having a sufficient number of public employees with the right skills is, therefore, the backbone of regional growth and well-being, and thus can influence the attractiveness of places to other target groups. However, attracting and retaining public sector employees with the right skills has become increasingly challenging for most OECD countries (OECD, 2023[48]). This trend has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting nearly all job categories. As a result, the Expert Group on Public Administration and Governance of the European Commission has identified the attractiveness of public administration as a top priority for 2023.

To prevent a lack of capacity that could compromise the delivery of services and regional attractiveness, many national and regional governments are taking action to attract and retain public sector workers. For instance, some governments are providing housing assistance, in the form of reserved housing, subsidised housing or down payment assistance to purchase a home. This can be particularly helpful in areas where the cost of living is high – e.g. South Korea, which has moved part of its administration outside of Seoul to reduce regional disparities and offers to house those who accept to relocate. In the United States, the city of San Francisco offers a programme called Teacher Next Door, which provides down payment assistance to public school teachers who agree to work in the city’s public schools. In the northernmost part of Norway, tax reductions and a write-down of student loans have been tested, with temporary results. From 1 August 2023, a new instrument of free kindergarten will be introduced to gauge its attractiveness to young families (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Rural Affairs, 2023[49]). The Valencian Community in Spain launched the GenT Plan to attract and retain top-level Valencian researchers living abroad or starting their careers; all nationalities are however welcome. Researchers receive financial support to develop their R&D projects in Valencia’s public universities and research centres, in addition to their wages. Since 2017, the region invested more than EUR 31 million and successfully attracted and retained 214 researchers (OECD, 2023[50]).

Aligning talent attraction and retention with regional development goals

The analysis presented in Chapter 3 reveals that regions with access to fast Internet speeds, affordable housing and home to a large share of international students are more attractive to foreign workers. These factors are also fundamental to a region’s development trajectory, showing that talent attractiveness strategies can be direct levers for regional development. By attracting and retaining talent, regions can create a virtuous circle of talent attraction, sustainable and inclusive economic growth, and quality of life for all residents. To do this, talent attraction and retention policies must be considered an integral part of regional development policies. “Talent proofing” can help ensure that all regional development policies are aligned with talent needs and realities.

Digitalisation: Access to broadband Internet

Talent is attracted to regions with fast Internet speed. Good Internet access facilitates teleworking, supports social connections, access to job opportunities, public and private goods and services, such as telemedicine, and human capital development (OECD, 2020[51]). The importance of access to Internet access to people’s localisation decisions is also indicative of the spreading trend of remote working culture, which slowly began before the pandemic and accelerated with COVID-19.

At the same time, fast Internet speed is important for regional development and leads to increased productivity and growth, helps create jobs and boosts the local economy. Regions with strong information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure can thus position themselves as attractive destinations to talent but also to firms, investors and visitors. This is why enabling access to quality and affordable digital infrastructure is increasingly important both for economic growth, attractiveness and retention (OECD, 2022[52]).

Since 2010, the share of households with high-speed Internet access has risen markedly in almost all OECD countries, with important differences within countries. In 2018, over 80% of households in 29 OECD countries had access to broadband Internet services. Inside countries, the differences in high-speed Internet access between urban and rural areas are often large, as well as between mountainous and non‑mountainous regions (see Chapter 3). Download speeds over fixed networks are thus, on average, 31 percentage points below the national average in rural areas and 21 percentage points above in cities (OECD, 2021[53]). The digital transition will continue to affect regions differently and rural areas could slip behind due to poor digital infrastructure, which may also lead to missed opportunities from teleworking.

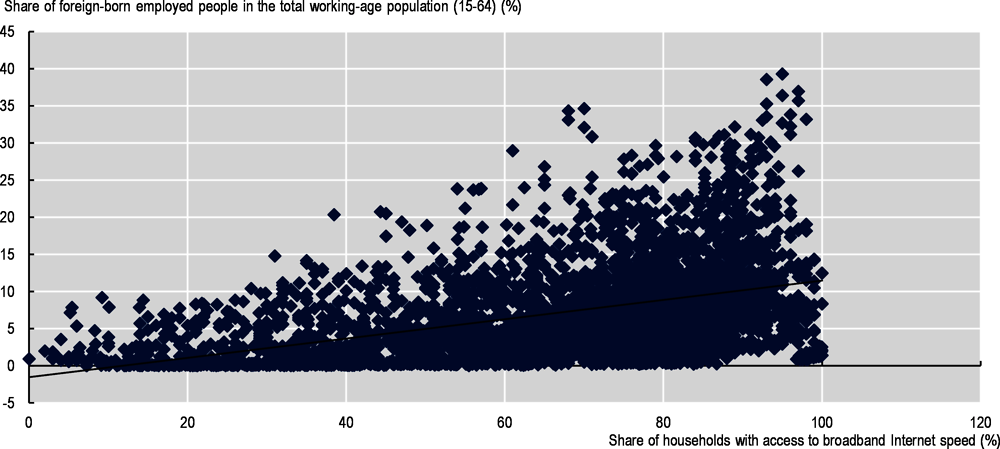

By investing in digital infrastructure and encouraging the adoption of digital tools, regions will position themselves for sustainable and inclusive development based on talent attractiveness and retention. Non‑metropolitan regions, on average less dynamic and most in need of newcomers to mitigate the impacts of demographic decline, have much to gain in this regard (OECD, 2022[6]). Indeed, as shown by Figure 5.1, there is a positive correlation between the share of households with access to broadband Internet speed and the share of foreign-born employed people in the total working population (talent). Digitalisation can be a significant driver for non-metropolitan development. Central governments have a responsibility in making sure the required infrastructure investments are made in all parts of their country.

Figure 5.1. Share of households with broadband Internet vs. share of international talent

Note: Time-series data were analysed spanning from 2003 to 2020.

Source: OECD (2022 or latest available) Regional Attractiveness Database.

Housing: Affordability

Affordable housing helps attract talent and has numerous benefits for residents and territories, yet it poses an increasing challenge. Housing offers security and protection, privacy, space and rest and determines one’s access to healthcare, education, digital infrastructure and labour market opportunities (OECD, 2021[54]). Housing markets have wide social, economic and environmental implications, including social cohesion, residential and intergenerational mobility and the transition to a low-carbon economy. However, housing has become less affordable over time in most OECD countries, particularly in urban areas where demand is high and supply is constrained (Bétin and Ziemann, 2019[55]). Those urban areas are often relatively attractive, meaning high housing prices mirror in some cases a region’s attractiveness, but, in time, start to form a bubble and potentially lead to a crowding-out effect. Inside countries, differences are wide. In Spain for instance, real house prices in 2019 were about 50% lower compared to 2007 in Navarra but only 15-20% lower in the Balearic Islands, Ceuta and Melilla (Fraisse and Pionnier, 2020[56]). Housing price heterogeneity may prevent the mobility of households to certain parts of countries and exacerbate existing inequalities. This calls for place-based solutions.

High housing costs in cities and assets of suburban areas are driving some people to places where land and housing are more affordable. As a result, physical urban space is growing faster than the population: the overall built-up area around the globe has increased 2.5 times over the last 40 years, while the population has increased 1.8 times (Moreno Monroy et al., 2020[57]). Such urban sprawl has a price. Rural areas may lose agricultural land to new housing, also affecting fragile ecosystems. People may have less access to public services and transport, and longer commutes to work by car, with implications for greenhouse gas emissions (OECD, 2018[58]). To ensure the sustainable and inclusive development and attractiveness of territories, governments must boost access to affordable, environmentally-friendly housing while keeping the consumption of resources (e.g. land, energy, water) low, for all to enjoy sufficient green space, safe transport and good amenities (Box 5.2).

Regions are best placed to design and implement housing policies. While national governments play a key role in providing the overarching legal framework, regions are better placed to understand and help forecast the needs of local governments, and hence identify local administrative and regulatory barriers, build synergies and monitor the impacts of housing policies which are local (they change where people choose to live, work and study). This underscores the need for regions to have the necessary financial and human means and for effective co‑ordination to exist across levels of government, as Chapter 7 will develop.

Box 5.2. Expanding housing supply without building more

Empty housing is a long-standing issue in OECD countries. Among those for which data are available, Hungary, Japan and Malta record the largest share of vacant dwellings, at over 12% (OECD, 2022[59]). Rural areas generally have more vacant dwellings than urban areas, except in Portugal where the difference is small. By co‑ordinating the right actors at the right scale, vacant properties can be made available without having to build more, thus reducing land use conflicts and negative environmental impacts. The Hej Hemby project launched by two municipalities in Norrbotten, Sweden, with the aim of creating livelier and more attractive village lives, successfully increased the housing occupancy rate through free support for houses and landowners, buyers and renters (OECD, 2023[45]). It also highlights the region’s assets by marketing the Arctic way of life in Sweden and abroad, partly by getting newcomers and locals to testify about quality-of-life stories. Introducing vacancy taxes on unoccupied buildings is another tool becoming increasingly popular among legislators to tackle housing shortages, with details varying.

These types of initiatives are particularly key to attracting and retaining youth. Instead of sticking around the places where they are born and raised, young people are often attracted to experience the “bright lights” of big cities. Several non-metropolitan EU regions thus face the intense departure of their young and skilled workforce (OECD, 2022[6]). Various structural challenges hamper youth attraction and retention in these areas, including scarcity of services, Internet connection, lack of transport and declining housing affordability in rental markets (Shucksmith et al., 2021[60]; Șerban and Brazienė, 2021[41]). With typically lower income and wealth and a greater likelihood of being employed in unstable or informal jobs than older groups, far fewer young households own their homes than their older counterparts, and are thus more exposed to rising prices (OECD, 2022[61]). Between 2005 and 2020, rent prices increased faster than general inflation in all but two OECD countries (Greece and Japan) and by more than a third faster than consumer price inflation in Estonia, Iceland and Ireland (OECD, 2022[62]). In response, countries and regions have developed plans to foster rural youth’s access to housing, for instance by offering grants to those looking for their first home, flagging affordable housing as a condition for the return of youth to their home regions or by giving specific loans for the construction and reconstruction of housing (Șerban and Brazienė, 2021[41]).

Source: OECD (2022[59]), Housing Stock and Construction, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HM1-1-Housing-stock-and-construction.pdf; OECD (2023[45]), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in the Norrbotten County of Sweden, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm; OECD (2022[6]), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022, https://doi.org/10.1787/14108660-en; Shucksmith, M. et al. (2021[60]), “Rural Lives: Understanding financial hardship and vulnerability in rural areas”, Rural Policy Centre; Șerban, A. and R. Brazienė (2021[41]), “Young people in rural areas: Diverse, ignored and unfulfilled”, European Union-Council of Europe Youth Partnership; OECD (2022[61]), Housing Taxation in OECD Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/03dfe007-en; OECD (2022[62]), “No home for the young?”, https://www.oecd.org/housing/no-home-for-the-young.pdf.

Education: International students in higher education

Finally, Chapter 3 suggests that foreign talent will be more open to locating in a region with an already substantial number of international talent – in this case, students. This might be the case because regions home to a large share of foreign students will likely have in place support structures and services for foreigners, and local communities with positive perceptions and attitudes towards foreigners, both of which facilitate their arrival and integration into the regional economy and society (OECD, 2018[21]). Furthermore, a higher share of foreign students can also create a network of contacts that foreign talent seeking to settle in the region can leverage when looking for housing, employment, etc. Therefore, universities play a magnetic role in the attraction of talent. This phenomenon seems to be particularly observed among knowledge workers who are highly mobile, tend to respond less to monetary incentives alone and value being surrounded by highly educated individuals (Florida, 1999[63]).

One instance highlighting the role of universities in attracting foreign talent is the Technical University of Cluj-Napoca in Romania, which is establishing a hub for scientific competitiveness and professional training in hydrogen technologies applied to electric transportation (ENIHEI, 2022[64]). Another example is Berlin, which has become a hub for start-ups and technology companies, partially due to the openness of its universities and their success in attracting international students and researchers. Finally, Luleå University of Technology in Northern Sweden is at the centre of the region’s green industrial revolution and plays a crucial role in attracting talented workers to the region through its various initiatives and collaborations including research opportunities, industry collaborations and networking events (OECD, 2023[45]).

However, it is important to note that high-speed Internet, housing and universities alone are not sufficient to attract and retain talent. The responsibility lies with institutions as well as companies in the region to provide opportunities and amenities that make an area appealing to talent in the long term. Without such opportunities and amenities, talent is less likely to arrive and more likely to leave a region.

A roadmap for regional talent attraction and retention

The OECD has developed a tool to clarify the main challenges affecting the ability of regions to attract and retain talent and to highlight best practices to address these challenges. It aims to support the dialogue between and the action of the different actors, across levels of government, who are involved in the design and implementation of regional attractiveness policies. It is, in effect, a roadmap to assess and respond to co‑ordination challenges for regional attractiveness based on dialogue between stakeholders.

Step 1 - Identify and understand target(s)

The first step is to identify the type of talent needed in the region, based on a data-driven approach, and to understand what it wants.

Tools and methods to address this challenge

Create information-sharing networks among employers (private and public) and the region to collect data on current and future labour and skills needs.

Support actors able to produce frequent local demographic forecasts (university research centres and statistical offices).

Interact with your target group, when possible, through surveys, to understand what drives their location decisions.

Examples of good practice: In the United Kingdom, the Working Futures quantitative assessment provides data on future labour and skills needs in the four UK nations and nine English regions, by industry, occupation, qualification level, gender and employment status, with the objective to inform policy development and strategy around skills, careers and employment. It is produced by the Warwick Institute for Employment Research and Cambridge Econometrics. In Quebec, Canada, the regional investment and development council, Quebec International, identifies companies’ needs. Sweden developed a new communication and brand strategy after surveying 7 000 international students in Sweden and discovering that the two main factors determining the choice of Sweden were the Swedish lifestyle and its education system.

Step 2 – Map assets and gaps

Once regional talent attractiveness needs are identified, it is necessary to examine how best to meet them. This requires conducting an analysis of the region’s strengths and weaknesses, which will serve as a common reference to draw up and monitor the various strategic documents involved in regional attractiveness.

Tools and methods to address this challenge: The OECD regional attractiveness compass serves as a powerful tool for diagnosing the attractiveness of a region to investors, talent and visitors (Chapter 3); (OECD, 2022[25]).

Example of good practice: The OECD compass has been successfully used by 25 regions.3 Ireland’s Regional Development Monitor4 collates a range of socio-eco-environmental indicators to present how each region performs in its objectives. The information and data visualisations are easily accessible and understandable, and regional stakeholders are encouraged to use them.

Step 3 – Identify stakeholders and improve co‑ordination

Once the most relevant sectors to invest in are established, identify stakeholders influencing regional attractiveness to talent, as well as their interactions with each other.

Tools and methods available to address this challenge: Institutional mapping of policies to attract talent across levels of government. The OECD provides a checklist for effective multi-level governance of attractiveness policies in Chapter 7.

Example of good practice: See OECD (2022[65]) for the Institutional Mapping of Talent Attractiveness Policies in France.

Step 4 – Identify and fund policies to attract talent in regions

Based on the identification of a region’s assets (Step 2), select policies most important to prospective employees (access to health services, affordable housing, etc.). Analyse the different available funding sources for each policy (European Union, national, regional, private, etc.)

Tools and methods available to address this challenge: Set up a Technical Committee on Attractiveness to select policies and funding sources (including EU funds experts when relevant).

Example of good practice: The North Sweden Green Deal is an initiative to attract new workers to northern Sweden to meet the extreme demand shocks caused by new industrial establishments (OECD, 2023[45]). The project is run by Region Norrbotten and Region Västerbotten and equips municipalities to attract and take care of potential immigrants.

Step 5 – Cohesive and consistent territorial marketing

How regions are perceived from the outside is important for attracting talent. However, while regional websites for attracting investors and visitors are numerous, those aimed at all foreign talent are rather non-existent. Moreover, marketing strategies are not only oriented towards external targets but also help strengthen the internal dialogue between regional development actors.

Tools and methods available to address this challenge: Bring together the local actors concerned so that they agree – on the basis of the regional assets identified (Step 2) – on a common identity and on a coherent brand to be put forward in a consistent manner on all communication channels.

Lexical semantics: agree on keywords to highlight the region’s main assets (access to nature, sense of community, etc).

Foreign language translation: agree on the languages in which to translate the websites (focus on target markets). Access to online information is a main gateway to the territory for foreign talent.

Visual identity (logo and slogans): branding allows public actors to promote their territory on a national and international scale. Territorial brands also help to create added value to locally produced goods and services.

Example of good practice: Copenhagen Region’s investment council (CopCap) talent attraction team’s digital branding strategy.

Step 6 – Monitor and evaluate

Select and track clear, robust and measurable indicators – ideally involving all regional stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector – to better understand the effects of talent attraction and retention strategies and adjust them as needed. Indicators should be aligned with broader regional development strategies that reflect the evolving requirements of firms and talent in today’s global environment.

Tools and methods available to address this challenge

Select, monitor and integrate indicators suggested by the OECD in relation to future strategies that are to be developed.

Integrate the economic, social and environmental impact indicators of these strategies to ensure that they contribute to the local, inclusive and sustainable development of the territories.

Example of good practice: See OECD (2022[65]) for indicators to monitor foreign talent and high-demand sector attractiveness policies.

References

[34] Andersson, M. (2023), 8 Place Attractiveness, Development and Marketing Trends for the Coming Years.

[55] Bétin, M. and V. Ziemann (2019), “How responsive are housing markets in the OECD? Regional level estimates”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1590, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1342258c-en.

[4] Business Europe (2022), “Labour force and skills shortages: How to tackle them?”, https://www.businesseurope.eu/publications/labour-force-and-skills-shortages-how-tackle-them-businesseurope-policy-orientation.

[5] Causa, O. et al. (2022), “The post-COVID-19 rise in labour shortages”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1721, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e60c2d1c-en.

[23] Charbit, C. and M. Tharaux (2021), “Differences in perception illustrate the need for placebased integration policies”, Anna Lindh Foundation.

[30] City of St. Catharines (2023), Arts, Culture and Events.

[10] Dares/France Stratégie (2023), Les Métiers en 2030 : Quelles perspectives de recrutement en région ?.

[24] Di lasio, V. and J. Wahba (2021), “Natives’ attitudes and immigration flows to Europe”, QuantMig.

[2] Diebolt, C. and R. Hippe (2022), “The long-run impact of human capital on innovation and economic growth in the regions of Europe”, in Human Capital and Regional Development in Europe, Frontiers in Economic History, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90858-4_5.

[7] EC (2023), Cohesion in Europe towards 2050, European Commission.

[8] EC (2023), “Harnessing talent in Europe’s regions”, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/communication/harnessing-talents/harnessing-talents-regions_en.pdf.

[1] Égert, B., C. de la Maisonneuve and D. Turner (2022), “A new macroeconomic measure of human capital exploiting PISA and PIAAC: Linking education policies to productivity”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1709, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1046e2e-en.

[11] ELA (2021), Report on Labour Shortages and Surpluses, European Labour Authority.

[64] ENIHEI (2022), 10 Recommendations and 1 Note on Innovation in European Higher Education, European Network of Innovative Higher Education Institutions, https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-11/ENIHEI-report-dec22.pdf.

[39] EU (2018), Addressing Brain Drain: The Local and Regional Dimension, European Union, https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/addressing-brain-drain/addressing-brain-drain.pdf.

[22] Eurochambres/Committee of the Regions/OECD (forthcoming), Public-private Cooperation for Better Local Refugee Inclusion.

[29] Falk, M. and T. Katz-Gerro (2015), “Cultural participation in Europe: Can we identify common determinants?”, Journal of Cultural Economics, Vol. 40/2, pp. 127-162, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-015-9242-9.

[19] Flood, M. et al. (forthcoming), “Addressing the left-behind problem”.

[63] Florida, R. (1999), “The role of the university: Leveraging talent, not technology”, Issues in Science and Technology.

[56] Fraisse, A. and P. Pionnier (2020), “Location, location, location – House price developments across and within OECD countries”.

[38] Future Place Leadership (2022), Switch to Sweden, Talent Map Report.

[3] Gennaioli, N. et al. (2012), “Human capital and regional development”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 128/1, pp. 105-164, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs050.

[27] González, S. (2010), “Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in motion’. How urban regeneration ‘models’ travel and mutate in the global flows of policy tourism”, Urban Studies, Vol. 48/7, pp. 1397-1418, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010374510.

[31] ICMPD (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 on talent attraction: An unexpected opportunity for the EU?”, International Centre for Migration Policy Development, https://www.icmpd.org/news/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-talent-attraction-an-unexpected-opportunity-for-the-eu.

[16] Kleine-Rueschkamp, L. (2022), “To deliver the green transition, we need more local green talent”, Business & Industry.

[33] Marcotullio, P., C. Keßler and B. Fekete (2022), “Global urban exposure projections to extreme heatwaves”, Frontiers in Built Environment, Vol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2022.947496.

[57] Moreno Monroy, A. et al. (2020), “Housing policies for sustainable and inclusive cities: How national governments can deliver affordable housing and compact urban development”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2020/03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d63e9434-en.

[49] Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Rural Affairs (2023), “Will introduce free kindergarten in the action zone in Nord-Troms and Finnmark”, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/distriktspolitikk/id2930594/.

[46] OCDE (forthcoming), Renforcer l’attractivité de la fonction publique d’État en région, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[32] OECD (2023), “A dialogue with Airbnb on the future of regions: Evolving attractiveness of non-metropolitan areas”, OECD, Paris.

[40] OECD (2023), “Beyond pink-collar jobs for women and the social economy”, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2023/7, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/44ba229e-en.

[17] OECD (2023), Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2023: Bridging the Great Green Divide, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/21db61c1-en.

[44] OECD (2023), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in Spain’s Cantabria Region, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm.

[50] OECD (2023), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in Spain’s Valencia Region, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm.

[37] OECD (2023), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in the Dalarna County of Sweden, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm.

[47] OECD (2023), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm.

[45] OECD (2023), Rethinking Regional Attractiveness in the Norrbotten County of Sweden, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm.

[48] OECD (2023), “Strengthening the attractiveness of the public service in France: Towards a territorial approach”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 28, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ab9ebe85-en.

[18] OECD (2023), “What is the best country for global talents in the OECD?”, Migration Policy Debates, No. 29, OECD, Paris.

[20] OECD (2022), “Allocation of competences in policy sectors key to migrant integration: In a sample of ten OECD countries”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 25, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dc4a71c5-en.

[36] OECD (2022), “Attraction, admission and retention policies for international students”, in International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ee801c11-en.

[59] OECD (2022), Housing Stock and Construction, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HM1-1-Housing-stock-and-construction.pdf.

[61] OECD (2022), Housing Taxation in OECD Countries, OECD Tax Policy Studies, No. 29, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/03dfe007-en.

[35] OECD (2022), International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/30fe16d2-en.

[25] OECD (2022), “Measuring the attractiveness of regions”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 36, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fbe44086-en.

[62] OECD (2022), “No home for the young?”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/housing/no-home-for-the-young.pdf.

[6] OECD (2022), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/14108660-en.

[26] OECD (2022), The Culture Fix: Creative People, Places and Industries, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/991bb520-en.

[65] OECD (2022), Toolkit for the Implementation of Recommendations for the Internationalisation and Attractiveness Strategies of French Regions, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regional/Internationalisation-Toolkit-EN.pdf.

[52] OECD (2022), Unlocking Rural Innovation, OECD Rural Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9044a961-en.

[54] OECD (2021), Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b453b043-en.

[53] OECD (2021), Implications of Remote Working Adoption on Place Based Policies: A Focus on G7 Countries, OECD Regional Development Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b12f6b85-en.

[51] OECD (2020), How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

[58] OECD (2018), Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264189881-en.

[21] OECD (2018), Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees, OECD Regional Development Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085350-en.

[43] Paavola, J., R. Rasmussen and A. Kinnunen (2020), “Talent attraction and work-related residence permit process models in comparison countries”, Finnish Prime Minister’s Office.

[42] Santos, R., R. Castanho and S. Lousada (2019), “Return migration and tourism sustainability in Portugal: Extracting opportunities for sustainable common planning in southern Europe”, Sustainability, Vol. 11/22, p. 6468, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226468.

[28] Schmutz, V., E. Stearns and E. Glennie (2016), “Cultural capital formation in adolescence: High schools and the gender gap in arts activity participation”, Poetics, Vol. 57, pp. 27-39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.04.003.

[41] Șerban, A. and R. Brazienė (2021), “Young people in rural areas: Diverse, ignored and unfulfilled”, European Union-Council of Europe Youth Partnership.

[60] Shucksmith, M. et al. (2021), “Rural Lives: Understanding financial hardship and vulnerability in rural areas”, Rural Policy Centre.

[13] Statistics Canada (2022), “Labour Force Survey, July 2022”, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220805/dq220805a-eng.htm.

[15] Stroobants, J. et al. (2022), “La grande pénurie de soignants est une réalité dans toute l’Europe”, Le Monde, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2022/07/27/crise-des-systemes-de-sante-en-europe-la-grande-penurie-de-soignants_6136283_3210.html.

[14] U.S. Employment and Training Administration (2022), “US Department of Labor announces $80M funding opportunity to help train, expand, diversify nursing workforce; address shortage of nurses”, https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/eta/eta20221003#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Bureau%20of%20Labor,occupations%20from%202016%20through%202026.

[9] Volk, C. (2021), “KfW-ifo Skilled Labour Barometer: Skills shortage in Germany worsened at the start of the year despite lockdown”, KfM, https://www.kfw.de/About-KfW/Newsroom/Latest-News/Pressemitteilungen-Details_634624.html#:~:text=Eastern%20Germany%20is%20more%20heavily,small%20towns%20or%20rural%20areas.

[12] WHO (2022), Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030: Reporting at Seventy-fifth World Health Assembly, World Health Organization.

Notes

← 3. The regional attractiveness case studies are available on the OECD Regions in Globalisation website (https://www.oecd.org/regional/globalisation.htm).