This chapter unpacks how the peer-to-peer learning embedded in Compliance Without Borders can help to strengthen SOEs’ risk management systems, management of individual risks and the corporate culture of integrity. It is backed with examples from the initial Compliance Without Borders pilot exchanges.

The Compliance Without Borders Handbook

2. Strengthening integrity in SOEs through Compliance Without Borders

Abstract

The Compliance Without Borders programme provides SOEs with support in strengthening their anti-corruption compliance regimes by bringing private sector compliance experts and SOEs together at no cost. Participants in the pilot phase of the programme have reported an increased understanding of existing anti-corruption and compliance trends and practices. They reported a greater familiarity with methods for establishing or strengthening anti-corruption compliance mechanisms as well as with existing resources available to strengthen their anti-corruption and compliance framework.

The programme supports SOEs in strengthening three notable areas: risk management systems, management of specific corruption risks and the culture of ethics. As SOEs face other risks that the programme is less suited to, for instance any challenges related to state ownership or politicisation of SOE boards, the programme focuses only on peer-to-peer learning in areas where SOEs and private firms find common ground. In the words of the Chief Compliance Officer of a participating SOE in a South American country’s transportation sector:

“The reality of individual SOEs is unique and should be fixed on particular risks – but structures are comparable [with the private sector]. It has been remarkable to identify opportunities to improve our ethics and compliance programme. Integrity has been incorporated as a value in our strategic plan; due diligence has been integrated permanently; the Code of Conduct is now applicable to third parties; our ethics culture is now being measured; and our consumer protection plan is being updated for new challenges” – Chief Compliance Officer of a state‑owned transportation company in Chile

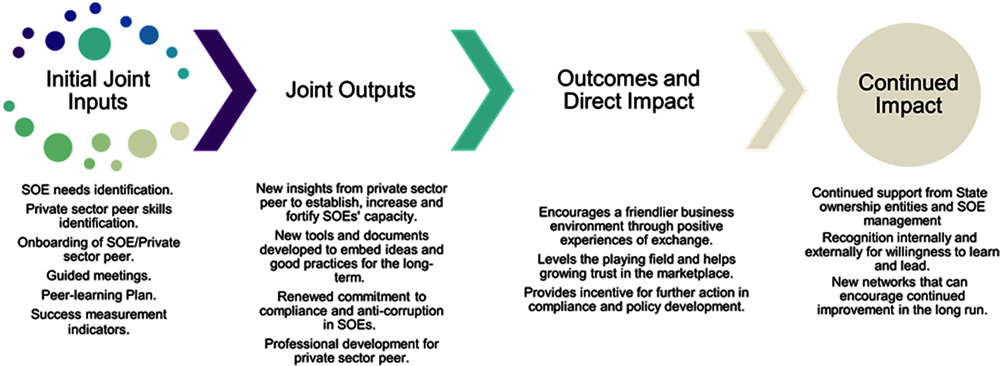

The individual “matches” between experts follow similar paths – or “theory of change” (see below) – that enables them to make concrete outputs and impact. The outputs of pilot programmes have included new insights and capacity, new tools and company-internal policy documents as well as renewed commitments to anti-corruption compliance. Chapter 3 provides more detail on the process itself.

Figure 2.1. Compliance Without Borders “Theory of Change”

Feedback from the first pilots has demonstrated individual achievements. Participants confirmed their intent to continue sharing the lessons learned and knowledge acquired during the exchange within their organisation, including branches or subsidiaries. This included: the knowledge acquired in preparing basic training programmes and tests on combating corruption for all employees in sensitive positions. They would go on to introduce new in-depth training programmes on the risks identified and elaborated on with the private sector peer for employees in sensitive or vulnerable positions. Other plans included updating their corruption risk management methodology, involving responsible employees in corruption risk assessment and risk mitigation planning and implementing of risk mitigation measures.

The theory of change for the programme implies that one catalyst of long-term success lies with the support and actions of the state owner. This is the case in Chile, for example, where the involvement of the state ownership entity has encouraged numerous SOEs to come forward (see below).

The value of support from the state owner

The OECD’s Guidelines on Anti-Corruption and Integrity in State‑Owned Enterprises call on state owners to encourage SOEs to adhere to high standards of integrity and to set expectations in the areas of ethics, internal control, risk management and compliance. SOE efforts to improve business integrity are more likely to be sustained when they are either encouraged or expected by the state owner.

Chile’s state ownership entity – El Sistema de Empresas (SEP) – sets expectations around internal and external audit, risk management and conflicts of interest through its Corporate Governance Guidelines for the SOEs that fall directly under its watch. SEP has been encouraging its SOEs to engage in Compliance Without Borders through its annual and bilateral meetings with SOE compliance officers. It has even spread the word beyond its portfolio to SOEs under the charge of other government entities. By disseminating news about the programme, SEP is providing its SOEs with opportunity and encouragement. Unsurprisingly, Chilean SOEs are reflecting the enthusiasm of their state owner. The owner sees that SOEs are responsive to opportunities to improve its integrity and corporate governance, and are willing to put in the time. SOEs too are encouraging their peers to get involved. As a result of joint efforts, one Chilean SOE is currently undertaking a peer exchange with a large multi-national, one has just been matched and four more are being onboarded into the programme.

Chile has in effect begun a “coalition of the willing” amongst the active and informed state owner and ambitious SOEs. The positive impact of one match is not confined to the SOE and private firms participating in a match. There is a spillover effect at the domestic level too where opportunities and actions of individual SOEs become the opportunities and actions of an entire portfolio. This bodes well for the longer-term goals of state owners and their SOEs to improve business integrity in the state‑owned sector more broadly.

The below sections go into further details about the benefits of strengthening anti-corruption compliance on the holistic level (e.g. improving risk management systems or strengthening a culture of integrity) and in issue‑specific areas (e.g. tackling conflicts of interest, developing codes of ethics), with examples of how Compliance Without Borders is catalysing those goals in participating SOEs.

2.1. Improving SOEs’ risk management systems

A risk management system is the pillar of corporate governance from which all company’s internal controls should be derived, monitored and adjusted. The ACI Guidelines outline minimum standards and good practices that could be considered by SOEs looking to build or strengthen their risk management system.

Good practice dictates that the risk management system should be integral to achieving an SOE’s objectives and strategy instead of simply mitigating possible sanctions for non-compliance with laws and regulations. This requires, inter alia, that the risk management system should be supported by the management and supervisory board, have adequate status, mandate, and resources to perform its function and rely on good communication and consultation of all levels of the organisation when conducting a risk assessment (OECD, 2020[9]).

The risk management system should be regularly monitored, reassessed, and adapted to each SOE’s operating environment and the emerging and changing corruption and integrity-related risks. In practice, the board should regularly discuss with senior management the state of the risk management system and provide oversight. It should challenge management and ask tough questions, as necessary, and consider the insights and findings of internal auditors and external auditors. Committees and sub-committees of the board can often assist the board in addressing some of these oversight activities.

A key component of an integrated risk management system is the risk assessment. Risk assessments are best conducted in a co‑ordinated manner to save time and money and avoid “risk assessment fatigue”. In practice, this mean that the assessment should: be conducted regularly and with inputs from across the company; be tailored; assess inherent and residual, internal, external risks; and consider interactions between SOE representatives and the ownership entity. Ideally, the risk assessment should be conducted at least annually to ensure it is up to date. SOEs may also want to consider triggering events such as entry into new markets, significant reorganisations, mergers, and acquisitions that offer opportunities and incentives for updating the risk assessment.

While it is a management responsibility to perform the risk assessment, report on the assessment to the board and implement risk mitigation action plans, the board should also play an active role, for instance by approving the results of the risk assessment and assigning the internal audit department, another designated person or an external party, to monitor and test the key controls identified to mitigate corruption risks. The following example provides a detailed overview of how the risk assessment was approached during one of the pilot programmes.

Compliance Without Borders examples: Improving SOEs’ risk management systems

Peers of one exchange between a state‑owned financial agency in Europe and a large multinational in the pharmaceutical industry initiated a change in the internal compliance procedure that enabled the compliance function to access the supervisory board directly. Until that point, the compliance function was only permitted to report to the management board. This change brings the SOE more in line with international good practice, including the relevant provisions of the OECD’s Guidelines on Anti-Corruption and Integrity in State‑Owned Enterprises.

Peers in another of the Compliance Without Borders pilots worked extensively on improving the SOE’s risk assessment methodology. Process and position assessments were discussed and solutions for enhancing future assessments were proposed by the private sector peer. The pair deduced that the private sector company’s corruption-risk impact assessment methodology could be largely applicable to the SOE, but the parties also looked into internationally recognised guidance for practical solutions. The peers stressed that the most significant insight in their analysis was the importance of keeping the risk methodology simple. This could be done “by changing risk probability and impact scale” and to align it with the United Nations’ “A Guide for Anti-Corruption Risk Assessment” assessment methodology (UN, 2013[10]).

2.2. Strengthening management of high-risk areas in SOEs

A strong system of risk management and control will provide for the identification and assessment of inherent internal, external and residual risks. It should enable companies to assess which risks are acceptable and whether controls should be established or adjusted. However, the OECD’s 2018 study found that one in ten SOEs had not considered corruption risks as part of its risk management process at all (OECD, 2018[3]). Those that consider corruption risks as part of the risk management process tend to classify them as compliance risks, as opposed to strategic risks. In some cases, this approach is reflective of the perception that corruption-risk management is solely a compliance exercise rather than a catalyst for the achievement of company objectives.

The ACI Guidelines encourage SOEs to ensure their suite of risk management and control processes adequately take into account risks arising from activities and arrangements that may be particularly vulnerable to corruption: human resource management; procurement of goods and services; board and senior/top management remuneration; conflict of interest; political contributions; facilitation payments, solicitation and extortion; favouritism, nepotism or cronyism; offering and accepting gifts; hospitality and entertainment; and charitable donations and sponsorships. This list is not exhaustive, and the risks of an SOE will naturally depend on their size, level of incorporation, degree of state ownership and the sector and country of operation, among other things.

Compliance Without Borders can help SOEs in ensuring that high-risk areas and corruption risks are identified upstream and iteratively (see Section 2.1), and that they are treated through the design of appropriate policies and controls. SOEs interested in Compliance Without Borders can request that a private sector peer support them in the process of identifying specific risks, or in establishing controls for risks they have confidently identified as needing treatment. See below for an example of how two pilot exchanges helped the participating SOEs to tackle high-risk areas.

Compliance Without Borders examples: targeting specific risk areas

In one European exchange, a compliance expert from Denmark working in the utilities sector supported a Latvian SOE in the transportation industry in developing a new Conflicts of Interest Policy. The pair relied on the support from the Compliance Without Borders co‑ordinators for advice on how to align their draft with international practices.

The programme has enabled another state‑owned transportation company in Latin America to make concrete changes to its third-party engagement, thanks to their exchange with an expert from a large multinational based in Switzerland. The SOE indicated an interest in tackling the risk of procurement and contract violations during the onboarding stage of the programme. This risk area subsequently featured as one of the subjects of the secondment. The SOE now confirms that, through the programme, due diligence has been integrated permanently into its processes, and its Code of Conduct is now applicable to third parties.

2.3. Developing a corporate culture of integrity in SOEs

The OECD’s 2018 report on corruption in SOEs highlighted that irregular practices in participating SOEs were more often caused by an override of controls than an absence of controls, or a combination of the two (OECD, 2018[3]). In other words, controls alone are not sufficient to ensure integrity in SOEs – they must coincide with a culture of integrity at the company and state ownership level.1

The OECD recommends a variety of measures to support an improved culture of integrity in SOEs. These elements include the promotion of: a “corporate culture of integrity”; a code of conduct, ethics or other similar policies; transparent and merit-based human resources policies that incorporate integrity requirements; maintenance of fair and accurate books, records accounts; channels for oversight and reporting, including internal audit, specialised board committees; measures to protect whistleblowers; ethics and integrity advice, guidance and training; and corporate investigative and disciplinary procedures to address violations.

The OECD’s Implementation Guide (OECD, 2020[9]), accompanying the ACI Guidelines, highlights some more ways in which senior leadership of an SOE can demonstrate its support. For instance, relevant individuals (a Chief Compliance Officer, for example) could be invited to board committees as well as to the management table, helping to solidify functional autonomy. Compliance professionals could be invited to provide input into management decisions or into the development of annual business plans.

Tip: Collective action can help strengthen the tone from the top. An increasing number of internationally recognised standards recommend engaging in collective action for its ability to increase enterprise compliance capacity in a practical, tailored and effective way. The OECD has explicitly recommended the use of collective action initiatives with private and public sector representatives to address corruption in its revised Recommendation on Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. Leadership backing for business integrity initiatives signals that it is important, and helps to make the outcomes of such initiatives more sustainable. This has been the experience of Compliance Without Borders.

Another key element of improving the corporate culture of integrity is to ensure its permeation at all levels of the company. This can be promoted inter alia through events, outreach and regular communications with all members of the corporate community, as well as through clear company standards that are developed and applied consistently – vertically and horizontally – throughout the corporate structure. Such activities will help individuals to internalise and understand the company’s suite of policies. One example of how Compliance Without Borders can support SOEs’ culture of integrity is discussed below.

Compliance Without Borders example: developing company standards

Codes of conduct typically help a company to elaborate and clarify its standards or rules. A Code of Ethics in turn typically identifies the principles that should guide behaviour and decision making. Good practice suggests combining the two. Such combinations find a balance between formulating general core values and offering a framework to support day-to-day decision-making (OECD, 2020[11]).

Peers in one of the Compliance Without Borders pilots analysed existing SOE Codes and identified how to strengthen their quality, for instance by pointing to a need to integrate rules regarding gifts and conflicts of interests. The peers moreover decided to draft an explicit and visible anti-corruption policy in line with international best practices.

Another match between the Head of Corporate Governance at a large state‑owned electricity firm in South America and the Head of Compliance in Latin America from a large multinational based in the US. The private sector peer has been keen to get involved from the beginning and came forward offering to support the SOE with its “compliance programme in the area of anti-bribery and anti-corruption risk management, with a focus on tone at the top compliance messaging, anti-bribery and anti-corruption training and communications and engagement with [the SOE’s] employees on establishing a culture of integrity.”

Note

← 1. Please refer to the OECD’s Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity as well as Recommendation II of the ACI Guidelines.