This chapter leads readers through the six-step risk-based due diligence framework, answering specific questions on how business can address environmental considerations under each of the steps.

Handbook on Environmental Due Diligence in Mineral Supply Chains

4. Six step due diligence approach

Abstract

Integrating environmental risk management into due diligence systems

This Handbook is addressed to all businesses in the minerals supply chain. However, as businesses have different responsibilities depending on their relationship to identified risks and impacts, they will use the information provided in this Chapter in different ways – depending on their position in the supply chain and on their size, where their most significant environmental risks lie, the nature, severity and likelihood of the impacts they face in practice and the nature of their business relationships.

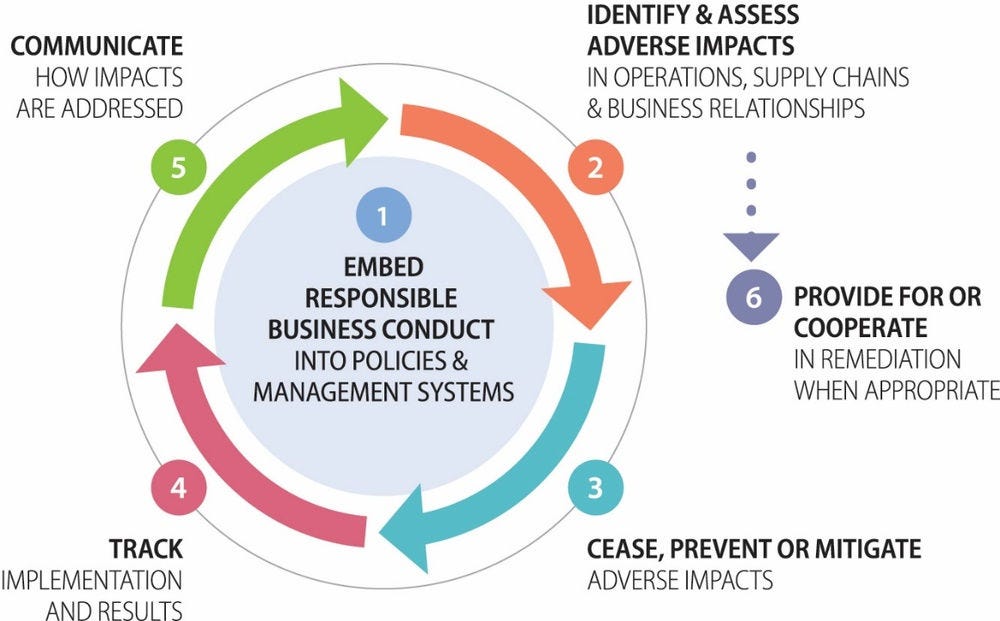

Figure 3. Due diligence process and supporting measures

Source: OECD (2018[15]), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due‑Diligence‑Guidance‑for-Responsible‑Business-Conduct.pdf.

Step 1: Embed RBC into policies and management systems

What do the RBC Guidance and Minerals Guidance say?

Devise, adopt and disseminate a policy – or combination of policies – on RBC issues that articulate the enterprise’s commitments to the principles and standards contained in the MNE Guidelines and its plans for implementing due diligence, for the enterprise’s own operations, its supply chain and other business relationships.

Embed the enterprise’s policies on RBC issues into oversight bodies and management systems so that they are implemented as part of the regular business processes, and incorporate RBC expectations and policies into engagement with suppliers and other business relationships.

Establish a system of controls and transparency over the mineral supply chain. This includes a chain of custody or a traceability system or the identification of upstream actors in the supply chain.

Key questions on how to integrate environmental risk considerations into Step 1:

1.1 How can an enterprise integrate environmental risk considerations into RBC policies and management systems?

1.2 How can an enterprise ensure that its RBC policies are fit for purpose and progressively tailor them to the enterprise’s most severe and likely risks (identified under Step 2)?

1.3 What is the relationship between existing environmental management systems (EMS) and environmental due diligence under OECD RBC standards?

1.1 How can an enterprise integrate environmental risk considerations into RBC policies and management systems?

The first step in integrating an enterprise’s most significant environmental risks into RBC policies and management systems is to identify and prioritise the broad categories of environmental risks the due diligence system will seek to manage and why.

Enterprises should review and update their existing policies to align with the principles and standards of the MNE Guidelines, and can consider developing specific policies on their most significant environmental risks –building on findings from their scoping, assessment and prioritisation processes under Step 2. They should also update their due diligence policy commitments as risks in the supply chain emerge and evolve. Table 2. provides an indicative non-exhaustive list of some environmental issues in upstream mineral supply chains that enterprises can consider integrating into their policies and management systems (and, where relevant, consider when reviewing a supplier’s own due diligence practices under Step 2).

As part of putting in place RBC due diligence policy and management systems, enterprises should also take proportionate, risk-based steps to:

Understand the enterprise’s own capacity, expertise and resources to collect information and embed due diligence effectively for priority environmental risk issues, with the aim of progressively improving systems and processes over time. For example, which internal and external stakeholders, including subject matter experts, are important to consult and engage with? For example, does the business have a presence in the country in which their supplier is operating that enables them to carry out regular and reliable monitoring of environmental risks and/or effective systems for meaningful supplier and stakeholder engagement, where appropriate?

Establish RBC policy goals in compliance with domestic laws and acknowledge the importance of applying the core principles of the mitigation hierarchy that prioritizes reducing or avoiding environmental impacts over restoration, compensation or offsetting measures when conducting risk management .1 Enterprises may also seek to be responsive to gender equality issues linked to environmental protection.2

Seek to understand and address barriers arising from the enterprise’s way of doing business that may impede the ability of suppliers to implement RBC policy expectations and/or contribute to adverse impacts in the supply chain (such as the enterprise’s purchasing practices, business and sourcing models and commercial incentives). Enterprises can also address the challenge of duplicative and conflicting supplier requirements through collaborating with other industry actors.

Embed expectations for suppliers on the enterprise’s most significant environmental risks. In addition to articulating expectations in RBC policies, enterprises can consider integrating due diligence expectations into pre‑qualification processes, bidding criteria or screening criteria for new suppliers.

Defining specific policy red lines. Enterprises may also choose to include detail on potential “red lines” in their RBC policies or in the expectations they set for new suppliers on environmental risks. Red lines may comprise situations that could –as a last resort –trigger disengagement from a supplier (e.g. where environmental risks or impacts are considered irremediable, where there is no reasonable prospect of change, or where severe impacts or risks are not immediately prevented or mitigated).

1.2 How can an enterprise ensure that its RBC policies are fit for purpose and progressively tailor them to the enterprise’s most severe and likely risks?

Environmental policies and management systems may often focus on technical aspects without taking into account the views of relevant stakeholders and experts.3 However, internal and external stakeholders and experts can play an important role in helping to ensure that RBC due diligence policy commitments are fit for purpose under OECD standards. Meaningful stakeholder engagement is a key component of the due diligence framework, although which stakeholders are relevant at a particular point in time and in a particular context will depend on the enterprise and its activities.4

Box 4. Meaningful stakeholder engagement

Meaningful stakeholder engagement is a key component of the due diligence process. In some cases, stakeholder engagement may also be a right in and of itself. Stakeholder engagement involves interactive processes of engagement with relevant stakeholders, through, for example, meetings, hearings or consultation proceedings. Relevant stakeholders are persons or groups, or their legitimate representatives, who have rights or interests related to the matters covered by the Guidelines that are or could be affected by adverse impacts associated with the enterprise’s operations, products or services. Enterprises can prioritise the most severely impacted or potentially impacted stakeholders for engagement. The degree of impact on stakeholders may inform the degree of engagement. Meaningful stakeholder engagement refers to ongoing engagement with stakeholders that is two-way, conducted in good faith by the participants on both sides and responsive to stakeholders’ views. To ensure stakeholder engagement is meaningful and effective, it is important to ensure that it is timely, accessible, appropriate and safe for stakeholders, and to identify and remove potential barriers to engaging with stakeholders in positions of vulnerability or marginalisation. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct and relevant OECD sector specific guidance includes practical support for enterprises on carrying out stakeholder engagement including as part of an enterprise’s due diligence process. This engagement is particularly important in the planning and decision-making concerning projects or other activities involving, for example, the intensive use of land or water, which could significantly affect local communities.

Source: Taken from the Commentary on Chapter II: General Policies of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD, 2023[16]), https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en.

Stakeholder engagement in mineral supply chains will play a particularly important role in tailoring due diligence due to the way environmental impacts in mineral supply chains may affect people. Extractive industry activities can degrade soil quality and contribute to air and water pollution threatening resources upon which people depend for subsistence. Besides directly engaging with stakeholders in connection with an enterprise’s operations, enterprises further downstream, as part of their own due diligence of supplier practices, could check to make sure stakeholder engagement takes place. When using stakeholder engagement as part of due diligence on environmental risks in mineral supply chains, enterprises should be aware of the nexus that often exists between environmental impacts and other RBC impacts addressed by the OECD Minerals Guidance like serious human rights abuses and corruption, with repression of environmental human rights defenders and different forms of corruption sometimes used to suppress community grievances or avoid accountability for environmental impacts.

When setting a policy on sourcing from small suppliers like ASM or associated small-scale processors, traders and smelters/refiners, attention should be paid to the limitations they may face in implementing corrective action plans in a timely and adequate manner. Consequently, policies still need to be set for small suppliers, but more flexibility should be allowed, with increasing stringency as the capacity of the supplier builds. For example, tailings management is important for ASM, but conformance with the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) may not be appropriate because of the limited capacity of ASM suppliers and lower risks associated with smaller tonnages of tailings.5

Appropriate allocation of resources is critical for understanding to what extent an enterprise policy is fit for purpose. Following consultation and policy finalisation, a budget and resourcing system could be developed to support implementation, that could include:

How the environmental and/or responsible sourcing management systems will be improved to support delivery on the policy’s commitments,

The parties responsible for policy implementation,

How staff will be trained in the new policy and improved management systems,

A communications and engagement plan defining how the policy will be communicated to customers and suppliers, and what and when new obligations will be included in new and existing contracts.

Finally, the monitoring of progress against RBC policy goals and specific targets and indicators under Step 4 helps enterprises to understand if its policies and management systems are addressing prioritised environmental risks and adverse impacts effectively. These type of feedback loops of lessons learned are important for continually improving processes and outcomes over time.

1.3 What is the relationship between existing environmental management systems (EMS) and environmental due diligence under OECD RBC standards?

Environmental management “involves carrying out risk-based due diligence with respect to adverse environmental impacts”, in line with the MNE Guidelines. In the context of the Guidelines, the term “environmental management” is interpreted in a broad sense, embodying “activities aimed at understanding environmental impacts and risks, avoiding and addressing environmental impacts related to an enterprise’s operations, products and services, taking into consideration the enterprise’s share of cumulative impacts and continually seeking to improve an enterprise’s environmental performance”.

Improving environmental performance requires a commitment to a systematic approach and to continuous improvement. An EMS provides the internal framework necessary to integrate environmental considerations into business operations. Having such a system in place should help to assure shareholders, workers, employees and communities and other relevant stakeholders that the enterprise is actively working to protect the environment from the impact of its activities. Table 3 illustrates related elements of an EMS (based on ISO 14001:2015) and corresponding due diligence under the MNE Guidelines and RBC Guidance.

In practice, however, traditional environmental management systems may differ in scope and purpose from the expectations set out under the MNE Guidelines. For example, they may be focused only on environmental impacts associated with an enterprise’s direct operations, rather than also taking into account risks and impacts across its supply chain and business relationships. They can entail a compliance‑based approach against specific environmental targets rather than a risk-based approach aimed at continuous improvement over time, and they may not sufficiently provide for meaningful stakeholder engagement.

As such, enterprises can take into consideration existing environmental management systems as one tool to support their due diligence whilst addressing gaps that may exist in existing systems as compared to the risk-based due diligence process recommended by the MNE Guidelines. For downstream enterprises this may entail evaluating the scope and relevance of suppliers’ environmental management systems and layering on their own due diligence.

Table 3. Integrating EMS into broader RBC considerations

|

Relevant step of the OECD Due Diligence Framework |

Corresponding elements of an Environmental Management System (based on ISO 14001:2015) |

|---|---|

|

Step 1: Embed RBC into policies and management systems |

Ensuring leadership and commitment of an enterprise’s top management, determining an environmental policy, organizational structures and processes for environmental management Ensuring necessary resources, competencies and adequate internal communication Understanding the context in which an enterprise operates, including the needs and expectations of its stakeholders and its legal requirements |

|

Step 2: Identify and assess adverse impacts in operations, supply chains and business relationships |

Identifying, assessing and internally communicating the environmental aspects and impacts and associated risks and opportunities Understanding the context in which an enterprise operates, including the needs and expectations of its stakeholders and its legal requirements |

|

Step 3: Cease, prevent or mitigate adverse impacts |

Establishing environmental objectives Planning and taking action |

|

Step 4: Track implementation and results |

Tracking implementation by evaluation of environmental performance and compliance Achieving continual improvement |

|

Step 5: Communicate how impacts are addressed |

Ensuring adequate external communication about the EMS and its outcomes |

|

Step 6: Provide for or cooperate in remediation when appropriate and Step 3: Cease, prevent or mitigate adverse impacts |

Address non-conformities and take corrective action. |

Source: ISO 14001:2015 Environmental management systems – Requirements with guidance for use.

Step 2: Identify and assess actual and potential adverse impacts associated with enterprise operations, products or services

What does the RBC Guidance say?

Carry out a broad scoping exercise to identify all areas of the business, across its operations and relationships, including in its supply chains, where RBC risks are most likely to be present and most significant.

Starting with the significant areas of risk identified above, map and carry out iterative and increasingly in-depth assessments of prioritised operations, suppliers and other business relationships in order to identify and assess specific actual and potential adverse RBC impacts.

Assess the enterprise’s involvement with the actual or potential adverse impacts identified to determine the appropriate responses. Specifically, assess whether the enterprise: caused, contributed to or was directly linked to the impact by a business relationship (or would cause, contribute to or be directly linked to a potential impact).

Drawing from the information obtained on actual and potential adverse impacts, where necessary, prioritise the most significant RBC risks and impacts for action based on severity and likelihood.

Key questions on how to integrate environmental risk considerations into this step:

2.1 What factors can an enterprise consider when scoping and prioritising environmental risks and impacts in its supply chain?

2.2 What types of information sources and tools can enterprises use to conduct in-depth assessments of prioritised suppliers on environmental risks and impacts?

2.3 What types of indicators may trigger enhanced due diligence?

2.4 What unique environmental risks and impacts can sourcing from secondary sources present?

2.5 When identifying and assessing climate impacts, what tools and resources are available for businesses to assess GHG hotspots in the supply chain?

2.6 How can an enterprise assess ASM involvement with actual or potential adverse environmental impacts?

2.7 How can an enterprise evaluate its involvement with identified environmental risks and adverse impacts in the supply chain?

2.1 What factors can an enterprise consider when scoping and prioritising environmental risks and impacts in its supply chain?

Enterprises should carry out an initial high-level scoping exercise across their own operations and business relationships to identify and prioritise the most severe and likely environmental risk areas, taking into consideration sector, product, geographic and enterprise‑level “risk factors”.6

Enterprises are expected to gather information from a range of sources for the purposes of the high-level scoping exercise, including information raised through early warning systems and grievance mechanisms and through engagement with relevant stakeholders and experts. The scoping should be updated with new information when the enterprise makes significant changes (e.g. operating in or sourcing from a new country; developing a new product or service line; engaging new forms of business relationship).

In the context of environmental impacts, some mining, smelting and refining processes have a greater environmental footprint than others and some geographies and biophysical environments are more sensitive than others. For example, businesses can consider the following factors:

Ecosystem type (terrestrial, marine and aquatic) and topography:

Where operations are located in biodiverse areas, such as forests, wetlands or littoral zones, heightened due diligence must be undertaken in relation to the risk of adverse environmental impacts occurring. For example, an increasing number of exploration licenses in tropical and sub-tropical forests has been observed, and a growth of mines in forest landscapes and in countries with weak governance for managing mining/forests interactions is expected.

While high biodiversity hotspots such as tropical forests deserve priority on the basis of biodiversity protection, in the context of mitigating climate impacts, the mining of peatlands, wetlands, grasslands and boreal forests is also highly destructive due to the carbon sequestration potential of the soils in these biomes, notwithstanding their own unique biodiversity.

Areas where there are surface water and groundwater resources that support important aquatic ecosystems and/or human uses such as for drinking water and subsistence or other traditional uses are also areas to note. Mining operations can impact water quality and quantity and the threshold for significant risks and impacts in areas of important aquatic and water resources may be lower than at other locations.

Moreover, where operations are located in areas prone to heavy rainfall, the impacts of seismic activity on dams’ integrity may be more consequential, with resulting increased risk for damage to physical operations (e.g. dam breaks resulting in uncontrolled acid and metalliferous drainage).

Type of mineral:

Some mineral deposit types have intrinsically higher risk, due to high concentrations of radioactive minerals, reactive minerals, acid generating minerals, metal leaching minerals or toxic elements that can be more challenging to manage. Mining, processing, smelting and refining wastes from these types of operations can pose a higher risk to people and nature during the operating life and for long time periods following closure of operations.

Increased risks are associated with the move to lower-grade ores, as they produce larger volumes of waste and require more energy, water and chemicals for processing.

Different commodities produce different environmental impact specificities. Some metals have high specific impact (potentials), but only small impact in absolute terms due to lower volumes and mass flows, while other metals (iron/steel) show high overall impacts mostly because of their larger volumes and mass flows. More information can be found in the OECD’s Global Material Resources Outlook to 2016 (OECD, 2019[17]).

Type of mining and processing:

The techniques and chemicals used to process the raw material may determine the likelihood of environmental risks and adverse impact. In general, refining and smelting tend to require high amounts of energy, which in many cases come from fossil fuels, that generate GHG emissions. Transport and handling tend to produce large amounts of dust, volatile organic compounds and GHGs and generate noise emissions (Garbarino et al., 2021[18]). Mineral storage tends to raise issues around safety (structural, physical and chemical stability), can produce emissions to soil, water and air (to a lesser extent), and have an impact on habitats.

Open pit mining may result in more land surface and air (dust) impacts than underground mining since the open pit land area and waste rock disposal areas take up more space as compared to underground mining. However, both underground and open pit mining can result in impacts to both water quality and quantity. Dewatering may be necessary during mine operations to keep mine workings dry and safe for miners, but this can impact water availability. Precipitation and runoff on and over mined surfaces and mining and processing wastes can result in mobilization of metals into adjacent lands, groundwater, and surface waters at both underground and open pit mines. Tailings impoundments can be a risk at many operations.

Identifying categories of materials, processes and ecosystems that may increase the severity and likelihood of environmental risks and impacts as part of an initial scoping exercise can provide indicators that inform a risk-based approach and enable the enterprise to carry out an initial prioritisation of the most significant risk areas for further assessment. Based on the prioritised risk issues, an enterprise can select individual higher-risk operations and business relationships for in-depth mapping and risk assessments to identify specific site‑level risks and adverse impacts.

Moreover, risks and impacts can occur during and following mine closure. For example, some operations may have tailings dams and impoundments that must be monitored and maintained far into the future to ensure stability and prevent leakage, potential pollution and failures. Some operations require long-term water management and monitoring since runoff and seepage that contact mine waste, tailings, pit and underground mine walls can remain a risk and potential source of impacts long after the mine closes. Post-closure environmental impacts can be as or more significant than risks during the mining operation itself if closure activities have not been implemented properly. In addition, there might be a higher probability that mitigation measures are not maintained or fail if the mining operator is no longer actively at the site and generating income to fund post-closure monitoring and maintenance.

2.2 What types of information sources and tools can enterprises use to conduct in-depth assessments of prioritised suppliers on environmental risks and impacts?

Enterprises are expected to carry out proportionate and risk-based assessments of prioritised suppliers to identify and assess specific environmental impacts. For most types of risks, assessments will broadly cover:

Actual or potential adverse impacts caused or contributed to by the supplier, including those associated with future projects or activities

The capacity and willingness of suppliers to carry out due diligence

The adequacy of the due diligence carried out, including measures to prevent, mitigate and remediate relevant environmental risks and impacts (Steps 3 and 6).

Seek to collect sufficient information to assess the nature and extent of actual and potential impacts linked to prioritised suppliers and identify information gaps or blind spots. They have a range of tools and sources of information at their disposal to evaluate different types of environmental risks and impacts (see Table 4).

The type of assessment and information sources that are appropriate in a specific context will depend, among other things, on the nature of the environmental risk, its severity and likelihood, where in the supply chain the risk is situated, and the position in the supply chain of each entity with a relationship to the risk or impact.

For example, where risks are situated in the furthest upstream segments of the supply chain, at or close to the point of extraction, downstream enterprises should obtain, when appropriate and feasible, information about business relationships beyond contractual suppliers and establish processes to assess the risk profile of more remote tiers of the supply chain. This can be done individually or collaboratively and can include reviewing existing supplier audits or other assessments, engaging with relevant mid-stream actors and/or control points (such as smelters, refiners and international concentrate traders) in the supply chain to assess the quality of their due diligence (see Figure 1), and consulting with relevant stakeholders.

The emphasis for downstream enterprises’ risk assessments in such a situation will generally be on assessing and improving the due diligence management systems of control points who tend to have greater visibility and leverage over other upstream segments. Alternatively, if a risk or adverse impact is situated at the control point itself, downstream enterprises’ risk assessments may focus on the control points’ own mitigation, prevention and remediation activities.

Table 4. Examples of indicators and sources of information for identifying and assessing key environmental risks in upstream supply chains lists some examples of generic sources of information for evaluating environmental risk or impact categories against possible indicators; Annex B provides more detail with examples of the types of organisations, tools and online resources.

Table 4. Examples of indicators and sources of information for identifying and assessing key environmental risks in upstream supply chains

|

Environmental issues |

Potential data and Indicators |

Non exhaustive list of potential sources of information and helpful tools |

|---|---|---|

|

Biodiversity loss (e.g. deforestation, coral reef degradation, species loss) and damage to protected areas |

Area taken up by operations Species at risk Measures of ecosystem health using biomonitoring data Ecosystem services impacted Proximity to key biodiversity areas Destroyed area of valuable habitats Disturbance of wildlife Area deforested % of key biodiversity areas that may be impacted by operations Information on physical hazards and toxicity from materials to human health and the environment during the handling, transport and use of these materials. |

EMS Environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs), including biodiversity management plans, biodiversity action plans, mine closure plans and biodiversity offset plans Academic, industry and non-governmental organisation (NGO) studies Ongoing monitoring data from government or the supplier Environmental and water management programme reports from government or the supplier National / regional guidelines and assessments on biodiversity assets and natural capital Earth observation tools and software International bodies such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) may have additional data available for certain regions. |

|

Climate change (e.g. GHG emissions , failure to adapt to physical risks of climate change) |

Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions Alignment with relevant targets and transition pathways |

The entity’s net-zero transition plan The entity’s climate change adaptation plan Sources of information related to the credibility of net-zero transition plans including e.g. Race to Zero Criteria, UNHLEG Integrity Matters report EMS ESIAs Environmental and Social Management Programmes (ESMPs) Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) GHG reporting frameworks Academic, industry and NGO studies and expert engagement Compliance with GHG emission standards Carbon Disclosure Project data |

|

Improper use and disposal of hazardous materials |

Amount and types of hazardous materials used Quantity of hazardous materials released into air or water sources Information on physical hazards and toxicity from materials to human health and the environment during the handling, transport and use of these materials |

EMS ESIAs ESMPs LCAs Academic, industry and NGO studies Safety Data Sheets |

|

Noise and vibration |

Intensity and frequency of noise generated Intensity and frequency of vibrations |

ESIAs EMS ESMPs Community monitoring systems Academic, industry and NGO studies |

|

Physical instability, soil erosion and land degradation |

Number and frequency of tailings storage facility breaches Number and frequency of slope failures Volume of potentially unstable material Earthquake risk Data on soil quality |

Feasibility stabilities Geotechnical studies Slope monitoring data Earthquake risk assessment Earthquake monitoring data EMS ESIAs ESMPs Geotechnical studies Participatory stakeholder monitoring |

|

Pollution (air, water etc) |

Air emissions (excluding GHGs) – amount and types Type and quantity of pollutants discharged Number of people living in the local area (watershed, airshed) Number of people dependent on local freshwater for domestic use Number of people dependent on local environment (e.g. rivers, lakes, forests and biodiversity) for food security and nutrition Number or people afflicted with pollution related illnesses Information on physical hazards and toxicity from materials to human health and the environment during the handling, transport and use of these materials. |

EMS ESIAs ESMPs LCAs Central and regional government monitoring networks Academic, industry and NGO studies Safety Data Sheets Census information for the local area Socioeconomic and ecosystem services baseline studies Participatory stakeholder monitoring |

|

Damage to aesthetics and cultural heritage sites |

Area taken up by operations Number of complaints about impacts on cultural heritage sites or visual aesthetics |

ESIAs ESMPs Academic, industry and NGO studies |

|

Waste mismanagement |

Waste generated (amount and type) Waste management system % of tailings with liners in place to minimise seepage Type of seepage management design implemented % of tailings storage facilities with closure cover % of waste rock dumps with closure covers, where required Information on physical hazards and toxicity from materials to human health and the environment during the handling, transport and use of these materials. |

EMS ESIAs ESMPs LCAs Academic, industry and NGO studies Safety Data Sheets |

|

Water depletion |

Water use Data on water scarcity Water shed balance incl. other uses Surface water streamflow Groundwater level Proximity to other mines Water shed balances Water Footprint (ISO 14046) |

Hydrology studies and models EMS ESIAs conducted in the area, ESMPs Academic, industry and NGO studies Community monitoring systems LCAs Reports on water depletion, impacts on water availability for users |

Note: This table corresponds to the table on environmental risks in Chapter 2 of this Handbook.

Other sources and types of information that enterprises may find relevant when evaluating environmental risks associated with suppliers include:

Details of relevant supplier’s RBC policies, business and sourcing models with specific regard to prioritised environmental risk issues

Details of existing EMS, including whether they have been verified by an independent third party.

Details of existing ESIAs, including whether undertaken by an independent party and the extent of engagement with local communities during research, drafting and finalisation, and other environmental assessments, permits authorisations and permissions (see Box 4).

Early warning systems established by suppliers, to identify and prevent environmental impacts. These include four key elements: risk knowledge, monitoring and warning system, communication and dissemination of warnings, and supplier response capability (UNISDR, 2008[19]).

Details on suppliers’ strategies to address environmental impacts, for example, improvements in efficiency (use of appropriate equipment, process optimizations, etc.), renewable energy deployment (on-site energy storage, electrification of vehicle fleet, etc.), energy intensity reduction and neutralization.

Locations of relevant operations and concession areas, including exposure to extreme natural events, water stress, proximity to sensitive areas such as water sources, protected areas and other high value biodiversity areas and natural resources and human settlements. World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas (World Resources Institute, 2021[20]) as well as Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool Alliance tools (IBAT Alliance, n.d.[21]) are available to determine water stress and biodiversity risk.

Information on land clearance and restoration (as % of total asset / concession land size) including deforestation and reforestation (as % of total asset / concession land size).

Closure plans, covering decommissioning, social closure plans and site rehabilitation and financial provisions for this purpose.

Box 5. Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs)

In most jurisdictions a supplier whose activities give rise to significant risks and impacts (such as a mining operator) will be required to conduct an ESIA. ESIAs generally take into consideration the sensitivity, quality, and values associated with the biophysical, cultural and social environment should a risk occur, and the capacity of the receiving environment and populations to cope with resulting impacts. It should also consider the extent (geographic extent/distance, magnitude, intensity, duration) and likely consequence of impacts arising from the risk (IAIA, n.d.[22])

In addition to be being part of due diligence, the content of an ESIA can be a source of information used in due diligence processes. However, the specific content will vary from one jurisdiction to another and depend on the nature of the proposed operation being assessed. The quality and credibility of the ESIA can vary according to, for example independence of the assessor or expert team, credibility, rigor and depth of information provided, level and quality of stakeholder engagement, and level of transparency, among other factors. Where doubts arise about the quality or independence of an ESIA, the enterprise should not rely on information in the ESIA for its due diligence process.

Downstream enterprises can furthermore consider gathering information for example through:

Information raised through supply chain grievance mechanisms and other monitoring platforms, including to evaluate the effectiveness of operational level grievance‑mechanisms.

Meaningful engagement with relevant stakeholders and/or experts, including stakeholders affected (or potentially affected) by adverse environmental impacts associated with the enterprise’s operations, products or services, or their legitimate representatives.

On-site inspections or assessments, where possible, at prioritised suppliers (including with a local expert to build an understanding of the supplier, its activities and production and due diligence processes).7

Existing assessments of prioritised suppliers, for example by multi-stakeholder, industry or government-run initiatives (“sustainability initiatives”’) (such as ISO14001 audits or assessments by the Copper Mark, Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM), Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), World Gold Council (WGC), Responsible Steel, Aluminium Stewardship Initiative (ASI), the International Tin Association’s Tin Code), and the Environmental Social Guidance Standard for Mineral Supply Chains of the Responsible Minerals Initiative/Responsible Business Alliance.

Other collaborative approaches with industry actors, for example in sensitive landscapes that host significant production of a specific mineral category, enterprises can cooperate and jointly finance a Strategic Environmental Assessment at the level of the landscape (to be defined by relevant stakeholders) as opposed to specific operations (European Union, 2021[23]), to achieve economies of scale, identify cumulative impacts and priority issues to inform their sourcing strategies, and cooperate in reducing the severity or likelihood of certain risks arising (see Box 3 for an example of collaborative approaches to assessing environmental risks). This could be done for example through an industry platform or multistakeholder initiative such as the Responsible Mineral Initiative (industry-led) or the European Partnership for Responsible Minerals and the Public Private Alliance for Responsible Minerals (multi-stakeholder).

Supplier reporting and disclosures, for example, sustainability reports, climate and biodiversity disclosures (See Annex B) or in industry benchmarking initiatives such as those established by third-parties, as well as credible public reports. Earth observation tools or other geospatial data providers can be used to monitor observable changes in the landscape around a supplier’s operations, if relevant.8

Checking for issues prevalent in the region or area where a supply chain actor operates (for example, if a supplier operates in a region where several spillages have taken place as a result of shipping incidents, which caused damage to marine ecosystems, and the integrity of local transport and logistics within the supply chain can be checked).

Importantly, enterprises retain ultimate responsibility for their own due diligence under international standards. If using findings or other information from an industry, government-run or multi-stakeholder initiative to support their due diligence, enterprises should review the information to ensure that it is credible, relevant and up-to-date.9

Information blind spots

Enterprises, particularly those at greater remove or separated by several tiers in the supply chain from where the risk or adverse impact is situated, will naturally identify areas where they lack information or independent data to assess environmental risks. In some cases, it may not be possible to gather the necessary information and in others, an enterprise may not have the right expertise to know which questions to ask or where to look. Another example of blind spots is information on issues that have not yet manifested, for example, environmental impacts that may take place after a mine or smelting plant closure.

In these cases and depending on context, engagement with joint buyers or other relevant suppliers, intermediaries and stakeholders can be particularly important (e.g. relevant local NGOs, workers or their representatives or other impacted or potentially impacted stakeholders). For example, engagement with traders is important for gathering information on risks associated with transport and logistics activities, which often receive limited attention and where environmental impacts can be significant. Efforts to increase leverage over relevant suppliers or control points can also be important where enterprises lack necessary information (see discussion on Step 3 below).

2.3 What types of conditions may trigger enhanced due diligence?

Indicators of potentially high risk can be relevant to the risk scoping and assessment process under Step 2 and trigger enhanced due diligence efforts. Table 5 sets out illustrative, non-exhaustive examples of conditions related to mining, processing, smelting, recycling or refining activities which enterprises may warrant enhanced due diligence, depending on the context and the outcomes of their Step 2 scoping exercise.

Table 5. Illustrative examples of conditions related to mining, processing, smelting, recycling or refining activities (according to risk type) that may warrant enhanced due diligence

|

Type of environmental risk |

Illustrative examples of conditions that may warrant enhanced due diligence |

|---|---|

|

Biodiversity loss (e.g. deforestation, coral reef degradation, species loss) and damage to protected areas |

|

|

Climate change (e.g. GHG emissions , failure to adapt to physical risks of climate change) |

|

|

Improper use and disposal of hazardous materials |

|

|

Noise and vibration |

|

|

Physical instability, soil erosion and land degradation |

|

|

Pollution (air, water, soil) |

|

|

Destruction of cultural heritage sites and damage to aesthetics |

|

|

Waste mismanagement |

|

|

Water depletion |

|

|

Other |

|

1. Enterprises operating at the boundaries of protected locations, or that have protected areas within their zone of influence, can have huge impacts on protected areas, and thus may also warrant enhanced due diligence.

2. See Annex II of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD, 2016[24]) for more detailed information on serious human rights abuses.

2.4 What unique environmental risks and impacts can sourcing secondary sources present?

While they offer the opportunity to avoid environmental harms linked to mining and mineral processing, secondary materials are not free of risks and adverse impacts and present unique challenges when conducting supply chain due diligence. For example, adverse impacts on people and nature have been documented for lead acid battery recycling (Lead Recycling Africa Project, 2016[25]) and electronics recycling (UNEP, 2022[26]; UNEP, n.d.[27]).

Risks associated with poorly managed recycling include:

Contamination of air, soil and water, related human health impacts and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in food chains.

Exposure of workers to hazardous materials and related health impacts.

Incomplete recovery and removal of hazardous substances during recycling, leading to contamination of products made from the recycled feedstock.

Additional land usage and occupation by (informal) landfills for remnants of incomplete recycled initial products.

Special care is necessary when sourcing secondary materials from opaque supply chains i.e. when the source of the secondary material is uncertain. For some metals, such as gold, if the recycled metal is not subjected to due diligence, it can enable the laundering of materials mined in a harmful and illicit manner, including those contributing to serious environmental issues, as well as conflict and human rights violations. Enterprises sourcing recycled metal can, as a first step, verify the material is indeed recycled, and not partially processed mined material being passed off as recycled.

The next step is to understand the risk profile of different minerals (e.g. what chemicals are used for extraction, what emissions are caused through the recycling process, are they commonly processed together with other materials that may cause environmental damage). As part of a risk-based approach, enterprises may also need to determine where the recycling takes place, as location can significantly influence risks. Enterprises should complete a broad risk assessment of the recycler’s sources of supply, identify any conditions that may warrant enhanced due diligence if/where necessary. In many cases the adverse impacts of secondary materials might be blind-spots, and enterprises might need to tailor their due diligence approach to identify those blind-spots and consider how to tackle them (see answer to question 2.2 on types of information sources and tools can enterprises use to conduct in-depth assessments of prioritised suppliers on environmental risks and impacts?).

2.5 When identifying and assessing climate impacts, what tools and resources are available for businesses to assess GHG hotspots in the supply chain?

Risk-based identification and assessment of emissions is the first and most crucial step towards emission reduction target setting and GHG mitigation. The GHG Protocol classifies an enterprise’s emissions into three scopes:

‘Scope 1’ – direct GHG emissions that are from sources owned or controlled by the reporting entity, such as those emissions from the production and transportation equipment owned by the entity.

‘Scope 2’ – indirect GHG emissions associated with the production of electricity, heat, or steam purchased by the reporting entity.

‘Scope 3’ – all other indirect emissions (for example, associated with the production of purchased materials, fuels, and services, including transport in vehicles not owned or controlled by the reporting entity, outsourced activities).

Enterprises should assess their Scope 1, 2 and, to the extent possible based on best available information, scope 3 GHG emissions in order to identify where their most severe and likely impacts lie. Upstream enterprise emissions primarily fall under Scope 3 and in many cases, the crushing of ore as well as the chemical processing stage of mineral supply chains (i.e. refining and smelting) is a hotspot for GHG emissions based on their sources of energy and chemicals usage. It is important to assess emissions against the latest available scientific evidence and as different national or industry specific transition pathways are developed and updated. It is crucial to collect information on emissions from upstream suppliers so this can be integrated into the Scope 3 assessment.

Useful frameworks for corporate GHG accounting are the GHG Protocol, Responsible Steel GHG Standard, and the EU Environmental Footprint Method. Other useful frameworks to identify the carbon footprint of products (rather than of an enterprise) include the Global Battery Alliance’s Battery Passport GHG Rulebook (under development), the International Zinc Association Carbon Footprint Guidance for Zinc Production (under development), RE100 Technical Criteria, GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance and ISO 14040, 14044, and 14067.

2.6 How to assess ASM involvement with actual or potential adverse environmental impacts?

When sourcing from ASM, the following questions may provide a useful framework for approaching environmental risk assessments on prioritised environmental issues. To answer the following questions, an enterprise may wish to work in collaboration with other actors who are also sourcing directly or indirectly from the region. As mentioned at the top of this Chapter, the relevance of these questions will vary according to the enterprise’s position in the supply chain and its involvement with the risk in question. See also Figure 1.

General risk profile:

What is ASM mining? How does production work? Is any part of the process mechanised?

How risk-aware are the owners, leaders, workers? How and how well are the miners already controlling risk? What incentives exist already for them to manage and minimise risk? What are the barriers to controlling risk (generally and specifically environmental risks)? What would need to change to improve that?

Is the organisation part of any sustainable development, government or community programme to tackle environmental or human rights issues, or supported by any local support organisations?

What would happen to the miners and their families if they could not mine or sell their product into formal supply chains? What else could/would they do and what would be the impact of those activities?

Environmental impacts:

Where is the mining happening? What is the ecological sensitivity of this location? What is its conservation status?

How is the mining and any processing done and how is waste managed? Are explosives, fuel and chemicals used?

Is there a Safety Data Sheet for the material?10 Is the Safety Data Sheet up to date (not older than 5 years)?

Where and how do miners live while they are mining? Consider impacts of housing, subsistence, transportation between home and mine, for example miners’ reliance on wild meat or bush meat for protein, timbering for struts and tools etc.

How does the miners’ presence stimulate others to act in ways that impact on the ecosystem? Economic stimulus through raising awareness of or access to previously remote places, for example agriculturalists, hunters, lumberjacks use footpaths to penetrate wilderness and exploit natural resources, etc.

How is the material transported to customers? Are there any organisms or environments (receptors) that could be negatively affected by the material or its transportation?

Where environmental impacts are cumulative in nature:

Is there a bioaccumulation risk11 or a chronic toxicity effect12 indicated on the Safety Data Sheet for the material?

How many other ASM organisations operate in the area?

What is the overall ASM population in the area?

If possible to determine over time, what capacity does your supplier have to meet due diligence expectations (for example, in terms of organisational competence, environmental awareness, nature of adverse impacts, quality of risk management)?

What other economic activities exist that may extend, deepen or magnify your supplier’s direct and indirect impacts?

What relationships exist between your supplier and these other actors that could be leveraged to organise a more landscape level approach to risk management?13 What relationships exist between you and other stakeholders to explore collective leverage to tackle issues at the landscape level?

Mine closure and post-mining: 14

What are the legal requirements and to what extent are these enforced?

What plan – if any – is in place to avoid damage to the land as a result of post-closure ASM? What approach is being used or will be used to rehabilitate or restore lands degraded by ASM? Who holds responsibility for this and how realistic is it that closure will be done at all or well? Is this approach economically affordable, socially acceptable and ecologically viable?

Who holds responsibilities in active mine closure? And in post-closure monitoring and maintenance? How are miners, landowners, communities and local authorities involved in closure and post-mining phases?

What is the planned end purpose for the closed land (for example forestry, agriculture, natural forest, etc.)? How does this account for economic, social and environmental sustainability, including contributions to helping nature thrive either directly or indirectly?

Step 3: Cease, prevent, and mitigate adverse impacts

What does the RBC Guidance say?

Stop (cease) activities that are causing or contributing to adverse environmental impacts.

Develop and implement plans to prevent or mitigate actual or potential adverse environmental impacts.

Appropriate responses to risks and impacts associated with business relationships can include:

build and use leverage, to the extent possible, to prompt the business relationship(s) to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts or risks;

continuation of the relationship throughout the course of risk mitigation efforts;

temporary suspension of the relationship while pursuing ongoing risk mitigation; or

disengagement with the business relationship either after failed attempts at preventing or mitigating severe impacts, when adverse impacts are irremediable, where there is no reasonable prospect of change, or when severe impacts or risks are identified and the entity causing the impact does not take immediate action to prevent or mitigate. Critically, disengagement is a measure of last resort. A decision to disengage should consider the potential adverse social and economic impacts of disengaging and be done responsibly.15

What additional mineral-specific recommendations are in the Minerals Guidance?

FOR UPSTREAM: Identify and track which suppliers respond to information requests and which do not. Follow up with suppliers and set corrective action plans. Escalate uncooperative suppliers to senior management.

FOR DOWNSTREAM: If the point of transformation for the mineral cannot be identified, adopt a risk management plan to be able to eventually demonstrate significant measurable improvements to your efforts to do so. If the point of transformation can be identified, work with suppliers to establish measurable risk-mitigation actions intended to promote progressive performance improvement within a reasonable timescale.

Key questions on how to integrate environmental risk considerations into this step:

3.1 How can an enterprise evaluate its involvement with identified environmental risks and adverse impacts in the supply chain?

3.2 What actions can enterprises take to address identified harms in the supply chain? How can enterprises use their leverage?

3.3 What types of prevention and mitigation measures can enterprises reasonably expect of suppliers that are causing or contributing to significant environmental impacts?

3.4 How does the interaction between environment and human rights affect enterprise action to cease, prevent, and mitigate adverse environmental impacts?

3.1 How can an enterprise evaluate its involvement with identified environmental risks and adverse impacts in the supply chain?

An entity’s involvement or relationship to impacts in the supply chain is important because it establishes where the primary responsibility for addressing the impact lies, and how the enterprise is expected to respond (see Figure 4). An enterprise’s relationship to adverse impacts is not static. It may change, for example as situations evolve and depending on the degree to which due diligence and steps taken to address identified risks and impacts decrease the risk of the impacts occurring. See discussion of Step 3 below.

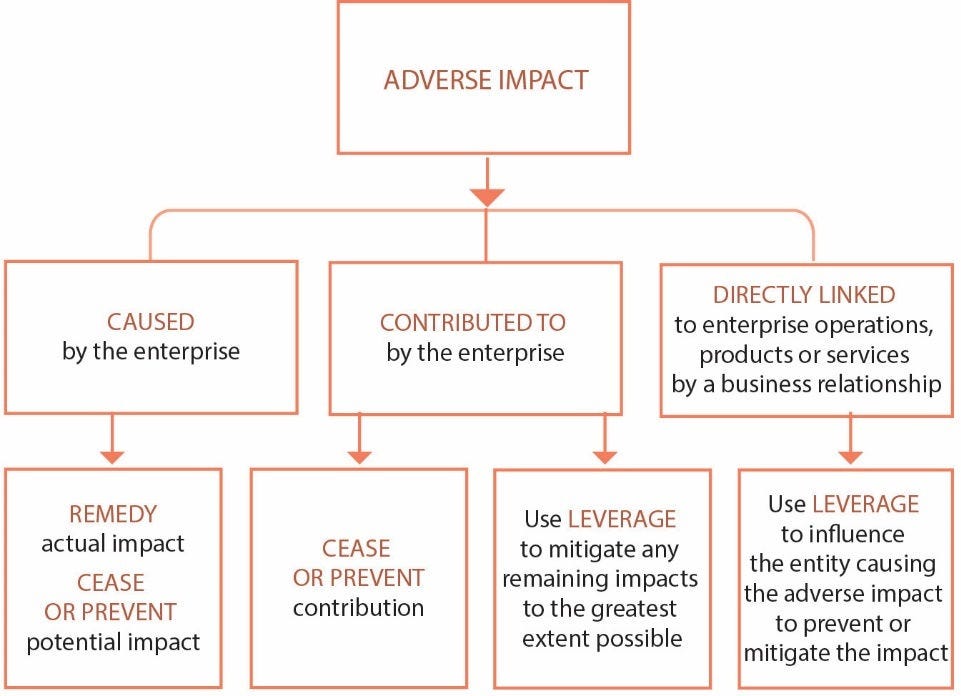

Figure 4. Addressing adverse impacts

Source: OECD (2018[15]), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due‑Diligence‑Guidance‑for-Responsible‑Business-Conduct.pdf.

An enterprise “causes” an adverse environmental impact if its activities on their own are sufficient to result in the adverse impact. An enterprise “contributes to” an adverse environmental impact if its activities, in combination with the activities of other entities cause the impact, or if the activities of the enterprise cause, facilitate or incentivise another entity to cause an adverse impact. Adverse environmental impacts can also be directly linked to an enterprise’s business operations, products or services by a business relationship, even if they do not contribute to those impacts.

3.2 What actions can enterprises take to address identified harms in the supply chain? How can enterprises use their leverage?

The risk-based due diligence approach is again integral to implementing Step 3. As it will often not be possible for enterprises to identify or respond to all identified risks and adverse impacts associated with their suppliers simultaneously, enterprises can prioritise specific risks and impacts for action on the basis of severity16 and likelihood. They should move on to address less severe impacts once prioritised impacts have been addressed. The same principles apply to how their suppliers should in turn prioritise risks and impacts for action.

As mentioned in Step 2, the enterprise’s relationship to an identified risk or impact determines the responsibility it has for addressing the impact. For example, where enterprises identify that they are causing or contributing to (or may cause or contribute to) environmental risks or impacts, they face heightened responsibilities, including to cease the activity contributing to harm and to provide remediation under Step 6 (see Figure 4). They are also expected to adopt prevention and mitigation measures, including through using and building leverage over other entities causing harm. Where enterprises identify that they are directly linked to an impact, they are expected to seek to prevent and mitigate impacts, including through using and building leverage (see also “What does the RBC Guidance say”, above).

Using leverage of suppliers is broadly understood and captures incentivising, supporting and otherwise effecting change in the behaviour of a business relationship (or other entity causing harm). How an enterprise chooses to support, incentivise or otherwise apply leverage over an individual business relationship will depend on the context –including the nature of its relationship, the degree of leverage it has, the nature of the risk or impact, and the supplier’s capacity to prevent, mitigate or remediate the impact.

Enterprises can consider adapting purchasing practices and business models or using leverage over their suppliers in a number of ways, for example by:

Using enterprise policies or codes of conduct, contracts, written agreements or market power. Building expectations around RBC and due diligence specifically into commercial contracts and linking business incentives – such as the commitment to long-term contracts and future orders – with performance on RBC. Clearly communicating the consequences if expectations around RBC are not respected (e.g. through meeting with management of the business relationship).

Supporting or collaborating with suppliers in developing fit-for-purpose plans for them to prevent or mitigate adverse environmental impacts (for example, net zero transition plans). In instances where suppliers may require guidance, capacity building or support on how to manage risks and prevent impacts occurring and address barriers or challenges, enterprises may support suppliers in reviewing the environmental risk controls in place, identifying gaps, and putting in place a corrective action plan. Suppliers may also require support and guidance on how to identify whether or not harm has occurred or may be imminent.

Supporting suppliers in the prevention or mitigation of adverse impacts or risks, e.g. through training, upgrading of facilities, or strengthening of their management systems: When sourcing from ASM, enterprises can work in partnership with the ASM cooperative or a specialist NGO that facilitates ASM cooperation, community representatives, local government, or multi-stakeholder ASM initiatives to support the ASM entity better manage its environmental corrective action plans. A helpful resource for ASM formalisation is the Code of Risk-mitigation for artisanal and small-scale mining engaging in Formal Trade (CRAFT Code), which is an open source tool for ASM and businesses potentially sourcing from the sector that sets progressive requirements for ASM. Ensuring that prevention and mitigation activities are appropriate requires collaboration with local stakeholders. To support the more systemic prevention and mitigation of environmental impacts over the long term, enterprises in the supply chain can play an important role in supporting the empowerment of local environmental NGOs and civil society organisations that work in collaboration with government and business, as well as local enforcement authorities.

Redesigning products to enable the substitution of materials or the use of secondary materials. Some minerals are substitutable within a product. Downstream enterprises may wish to make product design decisions based upon the relative environmental performance across candidate materials, such as the relative carbon footprint, water footprint, dependency on mining in forests or sensitive ecosystems, the toxicity of wastes and the efficiency of production. A full lifecycle analysis (cradle to grave) can support enterprises when making material substitution decisions, which can affect environmental performance of the product in its use and end-of-life phases.

Supply chain and public-private partnerships are one way large and small enterprises can work together to generate leverage, pool resources and conduct more efficient due diligence, especially when they do this visibly and with the ambition of leading the sector. For example, the Dutch Metals Agreement uses individual risk assessments of businesses to produce a collective heat-map showing industry risks (SER, n.d.[28]). These individual business risk assessments are submitted to the Secretariat of the Agreement which aggregates and anonymizes information to produce the heat map.

Other types of multi-stakeholder, industry-led and government-run initiatives can be a tool for enhancing collaboration across diverse industry players and their stakeholders, including by making joint statements to raise awareness about specific environmental concerns. Using a collective voice can also be helpful in co-creating solutions that can make environmental due diligence more feasible, more effective and thus more likely. There are also many industry initiatives that aim to develop global programs to assess, audit and improve sustainability practices within the industry’s supply chains.

There may be considerable variability in the capacity of enterprises to apply their leverage over suppliers and, in turn, the capacity of their suppliers to use their leverage over their sub-suppliers. Where an enterprise lacks leverage, it is expected to increase its leverage where possible, for example through modifying commercial incentives, engaging with industry peers, establishing longer-term relationships with suppliers or participating in collaborative industry, multi-stakeholder or government-run initiatives.

When sourcing from large refiners, smelters, recyclers or miners, downstream enterprises and control points like smelters or refiners may pay particular attention to the capacities, influence and resources the supplier may have to implement corrective actions and use their market leverage accordingly. Understanding if the supplier is participating in or assessed by industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives, for example, can orient the buyer on what influence may be exerted on the one hand (loss of market access through membership status) and what other resources or support may be available through the association (member services). As well as setting standards for enterprises, many initiatives offer tools, training or peer-to-peer learning opportunities for members and suppliers on specific challenges.

Box 6. Understanding and complying with a growing body of legislation that supports the Rights of Nature

Ecosystem services17 tend to be more protected by law than the intrinsic values of nature that are independent of human uses. However, jurisdictions are increasingly protecting the value of nature through ‘rights for nature’ laws (UN, 2022[29]) and a growing number of national and subnational governments and their courts have recognised legal personality of nature in recent years.

If a supplier is sourcing from a jurisdiction which acknowledges the rights of nature, work with the supplier to identify what additional risk management processes they have had to adopt to fulfil their responsibilities in this regard. If a supplier is not sourcing from a provenance that has afforded rights to nature, determine whether it would align with your business’ values to encourage suppliers to introduce measures that go beyond the consideration of how harm to the environment may manifest as harm to people, but also to nature.

3.2 What types of prevention and mitigation measures can enterprises reasonably expect of suppliers that are causing or contributing to significant environmental impacts?

The prevention and mitigation measures that are appropriate and proportionate in a particular situation will depend on a range of factors, including the nature, severity and likelihood of the environmental issue in question, the supplier’s involvement with the impact and, where it is contributing to an impact, the degree of leverage it has over other suppliers or entities causing harm. Table 6 provides examples of possible prevention and mitigation actions that suppliers can put in place where they have caused or contributed to significant environmental impacts.

Table 6. Examples of potential prevention and mitigation activities by suppliers for environmental risks

|

Environmental issue |

Possible corresponding prevention and mitigation actions |

|---|---|

|

Biodiversity loss (e.g. deforestation, coral reef degradation, species loss) and damage to protected areas |

In line with the Convention on Biological Diversity (UN, 1992[30]), suppliers may contribute to the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of their components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilisation of natural resources. Suppliers may also avoid and address land, marine and freshwater degradation, including deforestation, in line with objectives of UN SDGs notably 15.2, the UN Strategic Plan for Forests 2017‑2030 and the 2021 Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use which seek to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. Suppliers should prevent and mitigate adverse impacts on biodiversity in national parks, reserves and other protected areas, including UNESCO Natural World Heritage sites, areas protected in fulfilment of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and as defined in domestic law, as well as on protected species. This may include no further exploration, mining, smelting, refining or recycling-related activities in the aforementioned areas as well as environmentally responsible closure of existing exploration, mining, smelting, refining or recycling-related operations. Prevention actions • Suppliers may ensure that ESIA and ESMP are undertaken to international standards. • Where relevant, suppliers may develop a detailed biodiversity action plan to be integrated into management plans. • Suppliers may refer to the IFC guidance for PS6 (IFC, 2012[31]) to ensure:

• Suppliers and downstream enterprises may use earth observation tools to monitor land-use changes • In the context of deep-sea mining, suppliers may consider:

Mitigation actions • Immediately cease illegal activities. • Rehabilitate and restore affected areas. • Monitor, quantify and disclose management outcomes. • Efforts to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts on biodiversity should be guided by the biodiversity mitigation hierarchy, which recommends first seeking to avoid damage to biodiversity, reducing or minimising it where avoidance is not possible, and using offsets and restoration as a last resort for adverse impacts that cannot be avoided. Enterprises may plan and implement biodiversity offsetting to address any residual impacts that cannot be avoided and deliver no net loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services (including carbon storage) (OECD, 2016[32]). • Consider applying the World Bank’s Bolt-on Forest-Smart ASM Standard and Guidelines for sourcing from ASM in forest landscapes (World Bank, 2019[33]; World Bank, 2021[34]) and the World Bank’s Forest Smart Mining Guidance to applying nature‑based solutions in the large scale mining sector (World Bank, 2022[35]). |

|

Climate change (e.g. GHG emissions , failure to adapt to physical risks of climate change) |

Suppliers should prioritise eliminating or reducing sources of emissions over offsetting, compensation, or neutralization measures. Prevention actions • Immediately cease the expansion of any new operations in carbon sinks1 such as high carbon stock forests or peatlands. • Establish and implement a decarbonization plan in line with internationally agreed global temperature goals and best practices and adopt, implement, monitor and report on short, medium and long-term mitigation targets to ensure credibility and avoid greenwashing. • Establish and implement a climate change adaptation plan to limit the adverse impacts of their operations associated with current and future climate change impacts. Mitigation actions • Carbon credits, or offsets may be considered as a means to address unabated emissions as a last resort. Carbon credits or offsets should be of high environmental integrity and should not draw attention away from the need to reduce emissions and should not contribute to avoid locking-in GHG intensive processes and infrastructures. |

|

Improper use and disposal of hazardous materials |

The substitution of specific chemicals and materials used along the supply chain can lead to improvements in environmental performance. Substitution or alternatives may be adopted based on their comparative environmental risks, including impact on climate and circularity, life cycle analysis and stakeholder considerations. Prevention actions • Gold operations may only use cyanide where the operator is certified by the International Cyanide Management Code (The Cyanide Code, n.d.[36]). Mitigation actions • Gold operations can demonstrate progress towards the management and eventual elimination of mercury use by recovering and reusing it. • Gold operations may also participate in a national or local programme to implement the Minamata Convention (UN, 2013[37]) (in the case of ASM) and apply mercury emissions reduction measures in line with the US EPA Mercury Rule (US EPA, n.d.[38]) (in the case of large scale miners). |

|

Noise and vibration |

Noise and vibration can be prevented or mitigated by: • Establishing noise and vibration management plans. • Installing noise protection systems. • Improved planning and design of blasting activities. • Noise insulation of equipment and facilities. • Monitoring of noise emissions is a prerequisite for systematic management (EC Joint Research Center, 2021[39]). |

|

Physical and chemical instability |

Ensuring physical as well as chemical stability of all mine waste facilities are main long-term objectives of mine waste management to ensure safety of workers and the public as well as preventing leaching of long-term pollutants into the environment. (IGF, 2021[40]) Physical stability of mines can be addressed by: • Backfilling stabilized material into the excavated voids. • Monitoring of physical and chemical stability is a prerequisite to systematic management (EC Joint Research Center, 2021[39]) . |

|

Pollution (air, water, soil) |

Activities to prevent and mitigate pollution may include: • Modify facility design to eliminate pollution and the need for treatment of pollution beyond the post-closure monitoring period. • Reduce emissions at source (to the extent possible based on technical limitations). • Implement measures that control emissions related with secondary processing. • Work towards the implementation of appropriate health and safety measures. • Implement measures to capture and treat emissions that cannot be avoided. |

|

Soil erosion and land degradation |

Soil erosion and land degradation can be prevented or reduced by: • Establishing erosion and sediment control plans. • Soil management. • Soil conservation measures (EC Joint Research Center, 2021[39]). • Managing runoff with control fences and settling ponds (IGF, 2021[40]). |

|

Destruction of cultural heritage sites and damage of aesthetics |

Activities to prevent and mitigate damage to cultural heritage sites and natural aesthetics may include: • Undertaking an ESIA and ESMP to international standards. • Developing detailed plan to prevent harms to cultural heritage sites. • Anticipating that Indigenous Peoples may expect consultation seeking Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and that risks may be generated if such expectations are not met2. • Working toward no further exploration, mining, smelting, refining or recycling-related activities within sacred sites or that will irreversibly degrade such sites. • Developing inclusive compensation programmes in consultation with affected stakeholders. |

|

Waste mismanagement |

Activities to ensure environmentally responsible Waste management may include: • Working toward reducing and eliminating tailings disposal. • Remediating adverse impacts arising from past disposal of tailings. • Conform with requirements of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management for sites generating above a certain threshold of tailings per year. (Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management, 2020[41]). |

|

Water depletion |

Actions to prevent and mitigate water depletion may include: • Undertaking an ESIA and ESMP to international standards. • Modifying facility design to implement closed-loop approaches that reduce water consumption and increase water recycling and reuse. • Suppliers in water-stressed areas participating in public-private partnerships to manage water resources sustainably. • Prohibiting water depleting activities where there is high-risk of contributing to water scarcity/diminishing supply of water to cities/settlements. • Create new resources and/or access to ensure no net change in availability and quality of subsistence and traditional resources. |

|

Other |

Other activities to support the prevention and mitigation of environmental impacts may include: • Enterprises may demonstrate an anti-corruption policy with environmental protection in scope, and proof of implementation. • Operator may demonstrate progress with implementing a closure plan for mining activities that addresses sudden (unexpected) closure and closure at the end of life‑of-mine (including any required long-term maintenance and monitoring) within a reasonable timeframe, backed by adequate financial securities. |

1. A carbon sink is anything that absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases – for example, plants, the ocean and soil. https://www.clientearth.org/latest/latest-updates/stories/what-is-a-carbon-sink/#:~: text=A%20carbon%20sink%20is%20anything,fossil%20fuels%20or%20volcanic%20eruptions .

2. Enterprises should recognise that the process of seeking FPIC as iterative rather than a one‑off discussion. Continuous dialogue with the local community will lead to a trust relationship and a balanced agreement that will benefit the enterprise across all phases of the project.

Step 4: Track implementation and results

What does the RBC Guidance say?

Track the implementation and effectiveness of the enterprise’s due diligence activities, i.e. its measures to identify, prevent, mitigate and, where appropriate, support remediation of impacts, including with business relationships.

Use the lessons learned from tracking to improve due diligence processes in the future.

What additional mineral-specific recommendations are in the Minerals Guidance?

Monitor and track performance of risk mitigation efforts and report back to designated senior management.

Carry out independent third-party audit of supply chain due diligence at identified points in the supply chain. Companies at identified points (indicated in the Supplements) should have their due diligence practices audited by independent third parties.

Key questions on how to integrate environmental risk considerations into this step:

4.1 How can the tracking of implementation activities and results support the risk-based due diligence process and improve environmental outcomes?

4.2 How can an enterprise track the implementation and effectiveness of its own environmental due diligence activities and those of its suppliers? What type of information about environmental risks may be tracked?

4.1 How can the tracking of implementation activities and results support the risk-based due diligence process and improve environmental outcomes?

Enterprises are expected to carry out ongoing monitoring and track progress on the implementation and effectiveness of due diligence against appropriate outcome‑oriented and time‑bound indicators and targets. Tracking involves first and foremost assessing whether identified adverse impacts have been responded to effectively, prioritising those impacts the enterprise assessed to be most significant under Step 2 and took action to prevent or mitigate under Step 3. How an enterprise tracks the activities and outcomes of prioritised impacts, and how often, will vary according to the context (see question 4.2).