While some respondents feel that they have access to good-quality and affordable public services, particularly in the areas of education and public safety, many are dissatisfied with public services. They doubt the reliability of support from the government in the event of financial troubles. This is especially true for those who feel pinched by the cost-of-living crisis. On average, respondents are also sceptical about the adequacy of support for families with children and about the accessibility of long-term care for the elderly and people with disability.

Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey

2. Are governments doing enough?

2.1. Satisfaction tends to be highest for education, safety, and health, but respondents doubt that support is reliable

The worries about economic and social risks in RTM 2022 emerge off the back of negative health, income, and job shocks during the COVID‑19 crisis and subsequent inflation (OECD, 2021[6]). Many OECD governments came out of the COVID‑19 pandemic on their back foot.

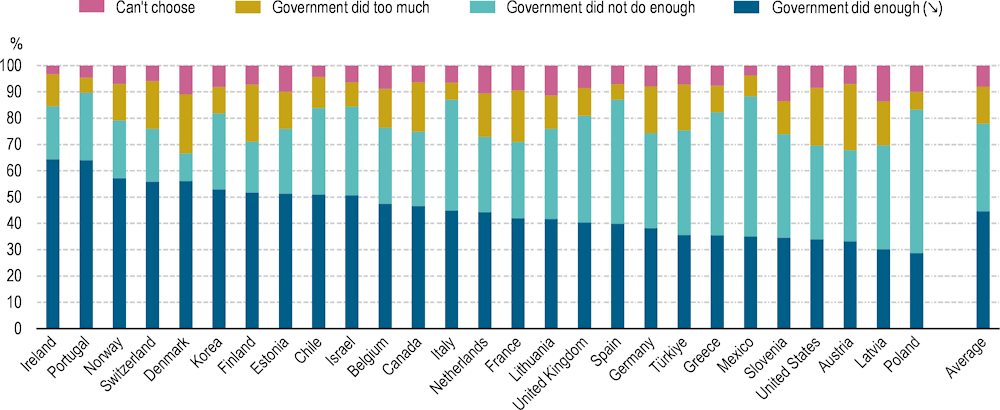

The 2022 RTM survey illustrates that many respondents are dissatisfied with their governments’ actions during the COVID‑19 pandemic. On average across countries, under half (45%) think that government did enough, while 33% think government did too much, and 14% think government did too little (Figure 2.1).

In eight countries a (slight) majority thinks the governments did enough, with rates highest in Ireland and Portugal, where 64% agree that government did enough to handle the pandemic. By contrast, the satisfied share is comparably small in Latvia (30%) and Poland (29%). Poland also has the largest share of respondents (55%) who do not think that the government did enough.

Respondents in only two countries (Denmark and Finland) are more likely to say that their governments did too much rather than too little to deal with the pandemic overall. Of course, in both of these countries, overall satisfaction levels with social protection (OECD, 2019[19]) and government (OECD, 2022[34]) are historically relatively high.

These figures on how well governments dealt with the pandemic are comparable to figures from the OECD 2021 Trust Survey, which asks about levels of trust in government. About four in ten respondents across countries report that they trust their government in general (OECD, 2022[34]).

Figure 2.1. Looking back, under half of respondents are happy with their government’s actions during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Overall, how do you think your government handled the COVID‑19 pandemic: Did the government do too much, the right amount, or not enough?”. Respondents could choose between: “Government did too much”; “Government did enough”; “Government did not do enough”; and “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”, and “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

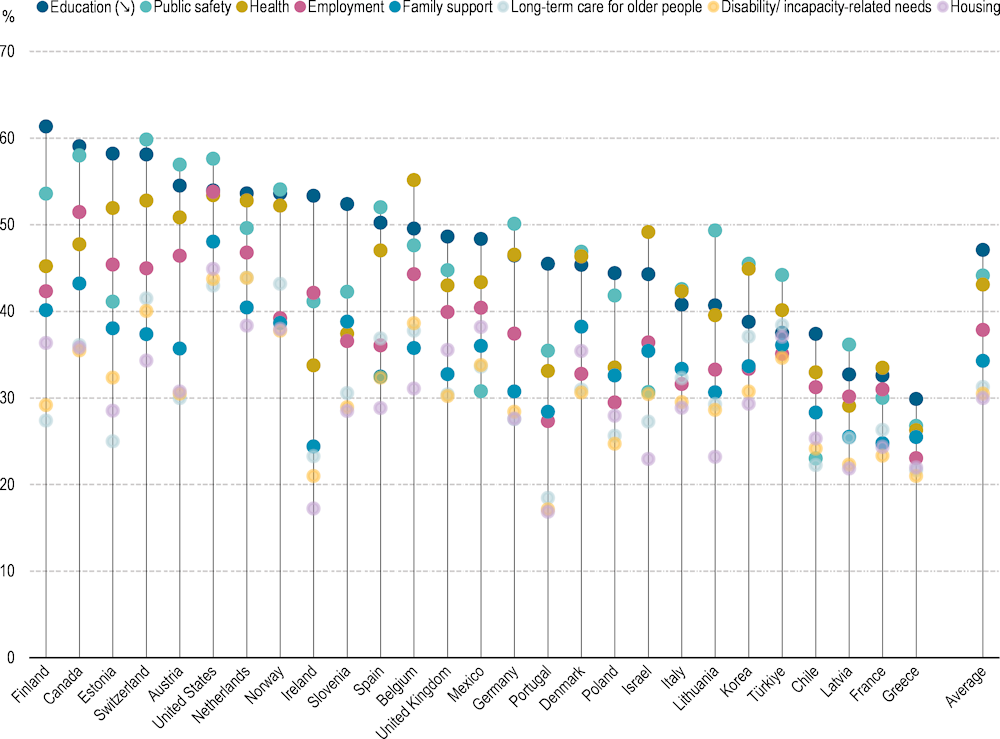

When looking at people’s satisfaction with specific social policy areas, fewer than half of respondents think that they would have good-quality and affordable access to any of the single public services in the areas of education, public safety, health, employment, family support, long-term care for older people, disability/incapacity-related needs, and housing.

Satisfaction with quality and affordability of public services tends to be highest in the areas of education, public safety, and health across countries, which is consistent with findings from the 2020 wave of Risks that Matter (OECD, 2021[2]). A majority of respondents are satisfied with their access to good-quality and affordable education in 11 countries (in descending order of satisfaction): Finland, Canada, Estonia, Switzerland, Austria, the United States, the Netherlands, Norway, Ireland, Slovenia and Spain.1 Some countries stand out in terms of certain policy areas, such as relatively high satisfaction with public health services in Belgium (55%) and Israel (49%). In both cases, worries about health are relatively less widespread than in many other countries (Chapter 1) (Figure 2.2).

By contrast, respondents are less satisfied with public housing, disability and incapacity-related services, and long-term care services for older people. For instance, very few respondents feel that they have access to good-quality and affordable public housing services in Portugal and Ireland (both at 17%). Portugal and Ireland also have among the lowest satisfaction with public disability, incapacity and long-term care services, along with Greece (Figure 2.2).

Satisfaction was low in the area of public housing services in the 2020 wave of RTM as well, even as governments took action during the COVID‑19 pandemic to help vulnerable households stay in their homes. However, the pertinence of housing affordability will only increase over the course of the current cost-of-living crisis. Facing current challenges after a period of structural problems with supply shortages and underinvestment, governments will need to take some concrete action to ensure sustainability of housing security for more households (OECD, 2021[33]).

Figure 2.2. Satisfaction tends to be higher for education, public safety, and health

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think that my household and I have/would have access to good quality and affordable public services in the area of […], if needed.” Family support (e.g. childcare, parenting support services, etc.)/Education (e.g. schools, universities, professional/vocational training, adult education, etc.)/Employment (e.g. job search supports, skills training supports, self-employment supports, etc.)/Housing (e.g. social housing, housing benefit, etc.)/Health (e.g. public medical care, subsidised health insurance, mental health support, etc.)/Disability/incapacity-related needs (e.g. disability benefits and services, long-term care services for persons with disability, community living resources, etc.)/Long-term care for older people (e.g. home, community-based and/or institutional care)/Public safety (e.g. policing)/Public transportation”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

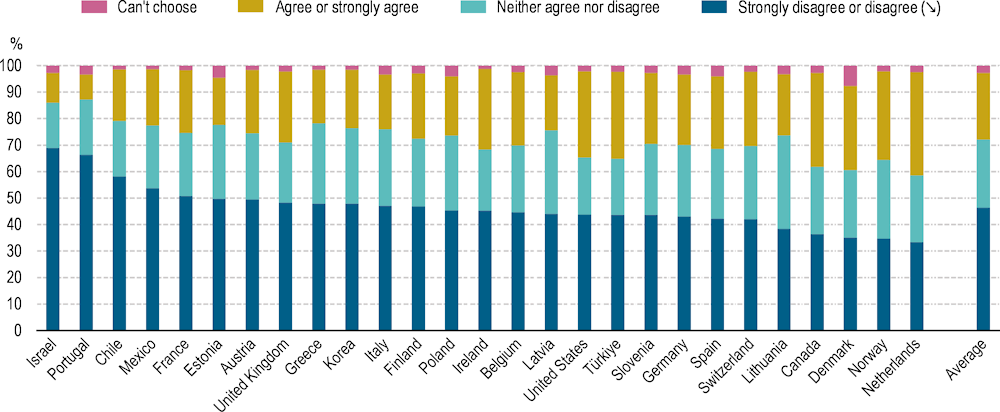

At the same time, access to public benefits is not perceived as straightforward. Close to half (46%) of respondents report that they don’t think they could easily receive public benefits if they needed them, and about one‑quarter (26%) say that they are ambivalent about whether they could receive benefits if needed (Figure 2.3). Accessing benefits is seen as particularly hard in countries like Israel and Portugal, while less so in countries like the Netherlands and Norway.

Figure 2.3. Few respondents feel that they could access public benefits in times of need

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement? If you currently are receiving services or benefits please answer these questions according to your experience. If you are not receiving them, please answer according to what you think your experience would be if you needed them: I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”, and “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

It is possible to zoom in on the reasons why benefit accessibility is perceived as low by focusing only on those who report thinking that benefits are inaccessible (the dark blue bars in Figure 2.3). Around three‑in-four (77%) of those who doubt they easily access benefits also doubt that the application process for benefits would be quick and easy (Table 2.1).

There could be various reasons for this perceived inaccessibility of benefits. For instance, benefit systems are often complex, and those eligible for benefits may have to apply to each benefit separately in order to receive them (Immervoll, Marianna and d’Ercole, 2004[35]; Hernanzi, Malherbeti and Pellizzari, 2004[36]). Enrolment and cross-enrolment are often only partially automatic, even if both of these can increase participation and simplify both the application process and the administrative costs for governments and agencies (Ambegaokar, Neuberger and Rosenbaum, 2017[37]). In addition, where digitalisation and automatic enrolment exist, inequalities in access can remain, with those not automatically included in the benefit system facing greater administrative burdens than others (Larsson, 2021[38]). Finally, even if social protection is relatively well developed in the most satisfied countries, the Netherlands and Norway (OECD, 2019[39]; OECD, 2019[40]; OECD, 2023[41]) – government communication of the availability and accessibility of benefits likely plays a role. Actual programme entitlements and eligibility do not always match up with perceived generosity in different countries (Frey, 2021[42]).

Among people sceptical of benefit access (Figure 2.3), over half (53%) doubt that their benefit claims would be fairly processed by the government office. This may be especially concerning if perceived discrimination means that some eligible benefit recipients do not apply to benefits because they do not think they would be accepted (Table 2.1). Perceived unfairness in claims processes is most common in Türkiye (78%) and Mexico (72%).

Table 2.1. Those who do not think they could easily access public benefits typically also think that the application process is complex

Proportion of respondents who report difficulties to access public benefits, among respondents who disagree or strongly disagree with the statement “I believe I could access public benefits if I needed them” (dark blue bars in Figure 2.3), by country, 2022

|

Country |

Do not feel confident they would qualify for public benefits (%) |

Would not know how to apply for public benefits (%) |

Do not think the application process for benefits would be simple and quick (%) |

Do not feel they would be treated fairly by the government office processing my claim (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

52 |

39 |

77 |

43 |

|

Belgium |

65 |

58 |

82 |

41 |

|

Canada |

64 |

56 |

76 |

45 |

|

Chile |

69 |

44 |

80 |

66 |

|

Denmark |

48 |

55 |

82 |

51 |

|

Estonia |

49 |

48 |

69 |

44 |

|

Finland |

48 |

32 |

82 |

40 |

|

France |

74 |

38 |

77 |

54 |

|

Germany |

49 |

42 |

85 |

46 |

|

Greece |

47 |

34 |

57 |

58 |

|

Ireland |

74 |

51 |

77 |

52 |

|

Israel |

67 |

58 |

83 |

59 |

|

Italy |

67 |

59 |

77 |

54 |

|

Korea |

43 |

55 |

75 |

46 |

|

Latvia |

65 |

42 |

65 |

43 |

|

Lithuania |

37 |

42 |

78 |

51 |

|

Mexico |

41 |

60 |

83 |

72 |

|

Netherlands |

56 |

38 |

74 |

40 |

|

Norway |

46 |

52 |

82 |

57 |

|

Poland |

55 |

44 |

79 |

63 |

|

Portugal |

64 |

57 |

86 |

66 |

|

Slovenia |

52 |

49 |

68 |

57 |

|

Spain |

61 |

50 |

80 |

55 |

|

Switzerland |

53 |

50 |

83 |

44 |

|

Türkiye |

42 |

38 |

77 |

78 |

|

United Kingdom |

75 |

57 |

81 |

56 |

|

United States |

78 |

56 |

82 |

53 |

|

Average |

57 |

48 |

77 |

53 |

Note: Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement? If you currently are receiving services or benefits please answer these questions according to your experience. If you are not receiving them, please answer according to what you think your experience would be if you needed them: I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them/I am confident I would qualify for public benefits/I know how to apply for public benefits/I think the application process for benefits would be simple and quick/I feel I would be treated fairly by the government office processing my claim. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, out of those who report that they could not easily receive public benefits if they needed them. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

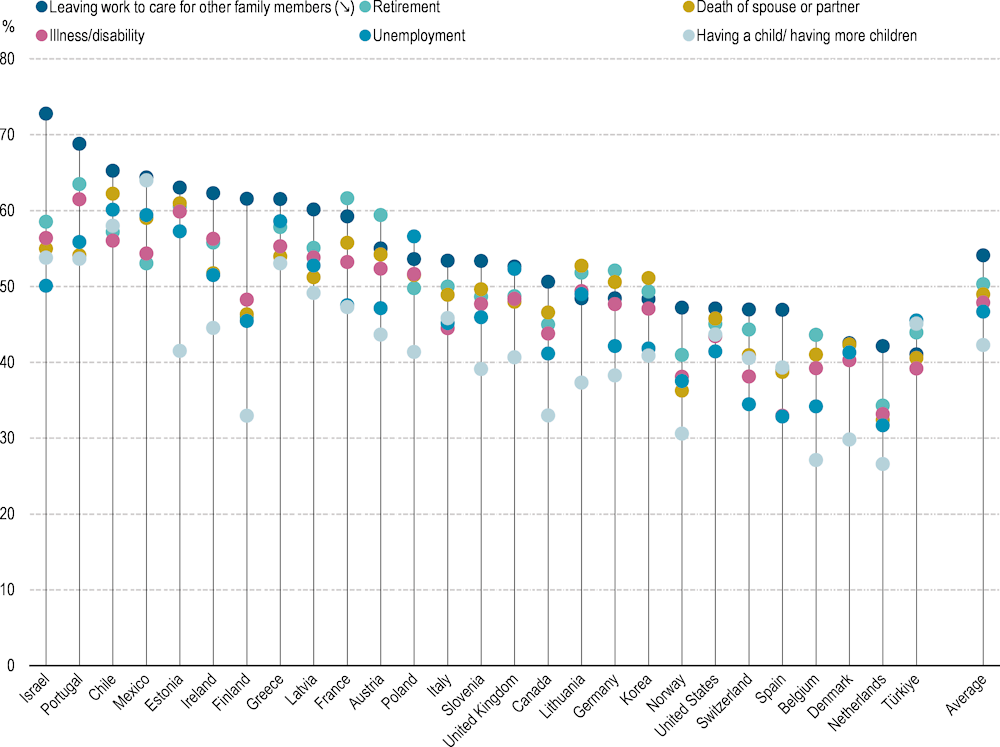

Even apart from the question of accessibility, respondents doubt that the level of income support would be (or is) high enough to support them through a period of income loss. The perceived lack of adequate income support often is similar across the six categories of circumstances listed: “leaving work to care for others”, “retirement”, “death of spouse or partner”, “illness/disability”, unemployment”, and “having a child/having more children” (Figure 2.4). In other words, where income support is seen as inadequate in one area, it is often seen as inadequate across the board.

An exception to this would be Finland, where only “leaving work to care for other family members” stands out in terms of perceived inadequacy while they are more content with the income support they would receive if they had a(nother) child.

Adequacy of income support is perceived to be slightly lower for circumstances that are related to older age, including “leaving work to care for other family members”, “retirement”, and “death of spouse or partner”. This is despite the fact that the RTM sample only includes working-age respondents aged 18‑64, so perhaps these issues would have received even more attention if RTM would have included older respondents as well. On the other hand, income support when having a child is perceived to be more adequate, although this differs across age and gender (Box 2.1).

Non-standard workers2 do not feel any less supported by government than other workers or those who are unemployed, despite being disproportionately likely to have experienced negative effects to their income and job during the COVID‑19 pandemic (OECD, 2021[43]). Controlling for factors like age, income level, and gender, non-standard and standard workers are similarly likely to think that they can easily access benefits and that income support from the government is adequate when it comes to circumstances like illness, unemployment, or retirement. This may be surprising since non-standard workers often stand outside of many contributory welfare safety nets. However, these findings are consistent with trends found in the 2018 wave of RTM (OECD, 2019[5]). It is worth noting that RTM does not ask workers how long they have been out of dependent employment, so for some workers, this may be a more transitory position and they may still have access to contributory social protection schemes.

Figure 2.4. Around half of respondents doubt they would receive enough replacement income support in given circumstances

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think that the government does/would provide my household and me with adequate income support in the case of income loss due to”: Unemployment/Illness/disability/Having a child/having more children/Leaving work to care for elderly family members or family members with disabilities/Retirement/Death of spouse or partner”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Data from the 2020 RTM survey show that there is almost no cross-national relationship between projected replacement rates for pensions and perceptions of government adequacy in old-age income support. It illustrates that countries with similar degrees of scepticism often have very different levels of actual pension generosity (OECD, 2021[2]). Similar patterns are seen in the 2022 wave of RTM. For instance, nearly half of respondents in Korea and Slovenia (49% each) are sceptical about the adequacy of income replacement in the case of retirement, even though the pension replacement rate for Korean men at average earnings is the lowest across the OECD, at 35%, compared to a replacement rate of 63% in Slovenia (Figure 2.4 (OECD, 2020[44]).3

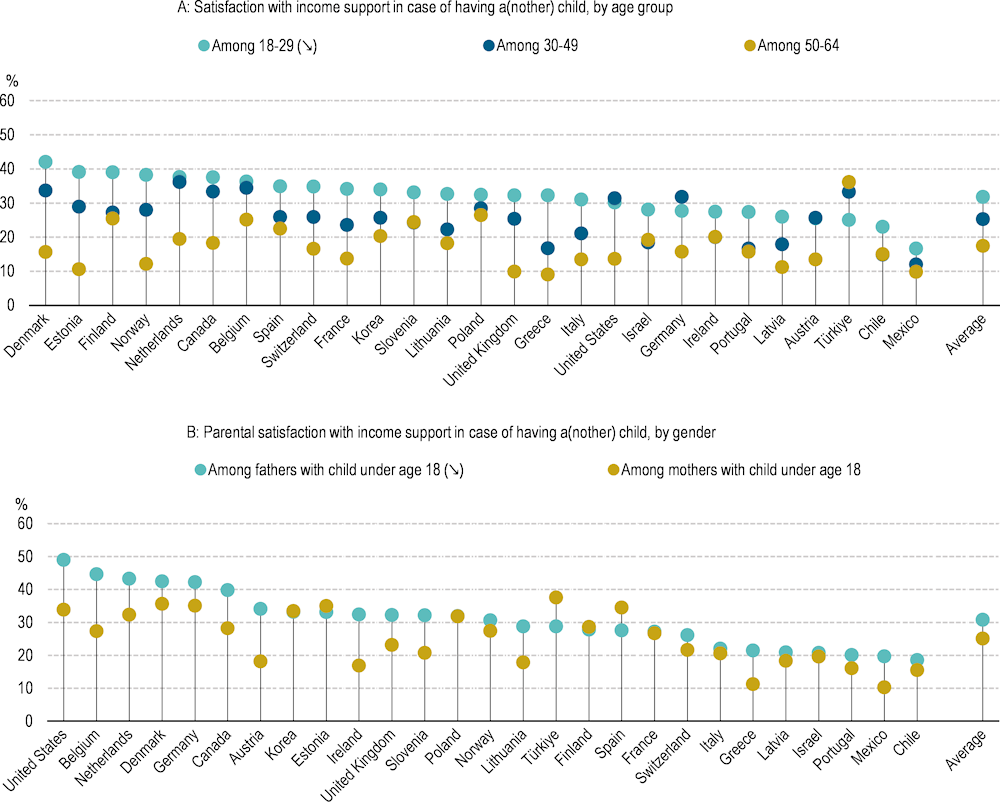

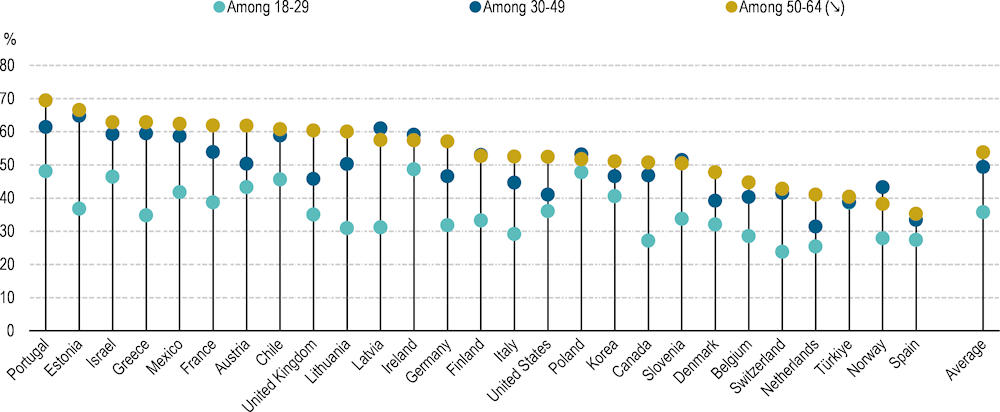

Box 2.1. Younger respondents and men tend to be more satisfied with parental income support

Respondents in general are sceptical of government income support for childrearing – only 24%, on average cross-nationally, agree or strongly agree that their government would/does provide them with adequate income support in the case of having a(nother) child. Yet younger respondents are almost twice as satisfied with this income support relative to the oldest age group: 32% of 18-29 year‑old respondents, on average across countries, think that child-related income support would be adequate, compared to only 25% of 30‑49 year‑olds and 17% of 50‑64 year‑olds (Figure 2.5, Panel A). In part, this might be because younger respondents consider recent increases in parental allowances and parental leave that have been implemented in many countries (OECD, 2022[45]), whereas older respondents may consider the conditions that were in place when they had children, years earlier.

Overall, parents tend to be more satisfied with income support than respondents who do not have children under the age of 18. Nearly 28% of parents are satisfied with the available support, while just 22% of those without children report this. In part, this may be because those who think that parental income support is sufficient may opt to have children or, alternatively, because perceptions change once children come along. In some cases, the perceptions of income support schemes might improve after people have children and familiarise themselves with available support schemes.

Fathers who have a child under age 18 are more satisfied than mothers with the income support provided by the government in the case of having an(other) child. In fact, fathers are on average 6 percentage points more likely than mothers to think that the government-provided income support when having a child is adequate (Figure 2.5, Panel B). It is unlikely that differences in knowledge about parental allowances between men and women are the reason for this gender gap in satisfaction since the gap is larger between mothers and fathers compared to men and women without children under the age of 18. The gender gap in satisfaction could be related to the fact that men are in general less worried about the household’s financial situation than women (Figure 1.11, Panel A). Somewhat surprisingly, satisfaction with the income support is only weakly related to the actual level of paid parental leave allowances across countries. Cross-country regressions show that for each additional week of paid paternal leave reserved for fathers (measured in full replacement equivalent weeks) (OECD, 2023[46]) men under the age of 34 years are 0.5 percentage points more likely to be satisfied with the available childbirth-related income support. However, their level of satisfaction does not depend on the extent of paid parental leave allowances available to the household as a whole. Furthermore, cross-country regressions also show that there is no relation between women’s satisfaction and the paid parental leave available to mothers or to the household.

Figure 2.5. Men and younger respondents are more confident than their counterparts in the adequacy of income support when having a(nother) child

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Panel A includes all respondents whereas Panel B includes only respondents who report that they have at least one child under the age of 18. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: ‘I think that the government does/would provide my household and me with adequate income support in the case of income loss due to having a child/having more children’. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “agree” or “strongly agree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18-64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

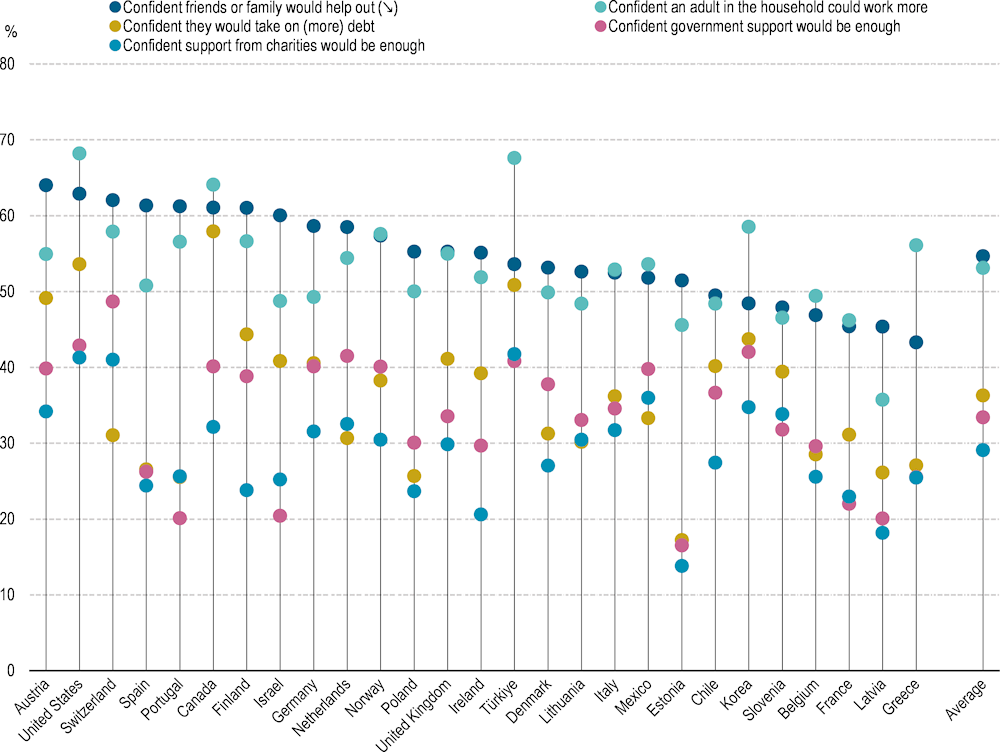

RTM 2022 asks respondents explicitly how they would cope in case they ran into financial trouble, such as not being able to cover their costs. As in previous years, respondents across countries are most likely to say they would rely on friends and family or take on more work in the event of financial trouble. On average across RTM countries, 55% of respondents report that they feel somewhat or very confident that a friend or family member would be able and willing to help out, and 53% of respondents report that they feel somewhat or very confident that another adult in their household could work more to bring in more money (Figure 2.6). There is a weak cross-national negative correlation between the proportion who say that they feel confident another adult could work more and the proportion of mothers in full-time employment in 2019 (OECD, 2019[47]). Only one‑third (33% for RTM 2022 (27 countries) and 34% for RTM 2020 (25 countries) say they feel confident that government would support them, a figure that is marginally lower than the corresponding 36% who say they would rely on government support mid-pandemic in 2020 (OECD, 2021[2]). Respondents are most positive about government support through financial troubles in Switzerland, where nearly half of respondents (49%) report confidence. Across countries, just 29% say they would count on support from charities.

Figure 2.6. It is more common to expect to work more and seek help from friends and family than to rely on government support in the event of financial difficulties

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “If you and your household were to experience financial trouble (such as not enough income or savings to pay the bills), how confident are you that: Another adult in your household could work more to bring in more money/A friend or family member would be able and willing to help out/Cash benefits and services provided by government would sufficiently support you through the financial difficulties/Cash benefits and services provided by charity or non-profit institutions would sufficiently support you through the financial difficulties/You would apply for a loan or take on (more) debt from a bank or financial institution”. Respondents could choose between: “Not at all confident”; “Not so confident”; “Somewhat confident”; “Very confident”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “somewhat confident” or “very confident”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

2.2. Respondents vulnerable to cost-of-living increases feel less financially supported by their government than others

As Chapter 1 shows, respondents are particularly worried both about paying their expenses and about access to good-quality healthcare. The remainder of this chapter takes a deep dive into the two top priority issues in Chapter 1: worries about making ends meet and accessing good-quality healthcare.

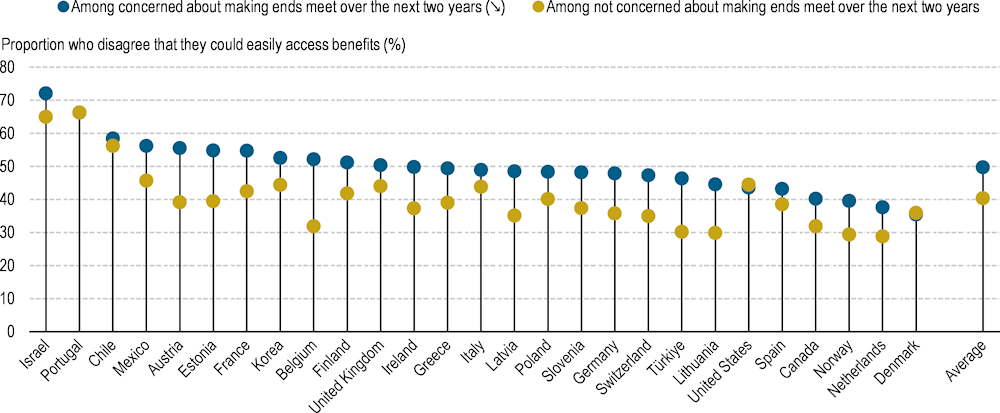

Respondents who report short-term financial worries about making ends meet tend to feel less supported by their governments than those who do not report being worried about short-term finances. Across countries, half (50%) of those reporting that they are concerned about paying all expenses and making ends meet also report that they do not think that they would easily receive public benefits if they needed them (Figure 2.5). This is about 10 percentage points less optimistic than people who are not worried about making ends meet.

The gap in perceived benefit access between those who are worried about making ends meet and those who are not worried about making ends meet is greatest in Belgium (20 percentage points), followed by Austria and Türkiye (both 16 percentage points) (Figure 2.5). By contrast, in some countries, including Portugal, the United States and Denmark, there is no statistically significant difference in perceived benefit access between those who are worried about their finances and those who are not.

Figure 2.7. Half of those worried about paying for expenses over the next two years feel that they would not easily access benefits if they needed them

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement? If you currently are receiving services or benefits please answer these questions according to your experience. If you are not receiving them, please answer according to what you think your experience would be if you needed them: “I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”. Respondents were also asked: “Thinking about the next year or two, how concerned are you about each of the following? Not being able to pay all expenses and make ends meet”. Respondents could choose between: “Not at all concerned”; “Not so concerned”; “Somewhat concerned”; “Very concerned”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned”, and “not all concerned” or “not so concerned”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

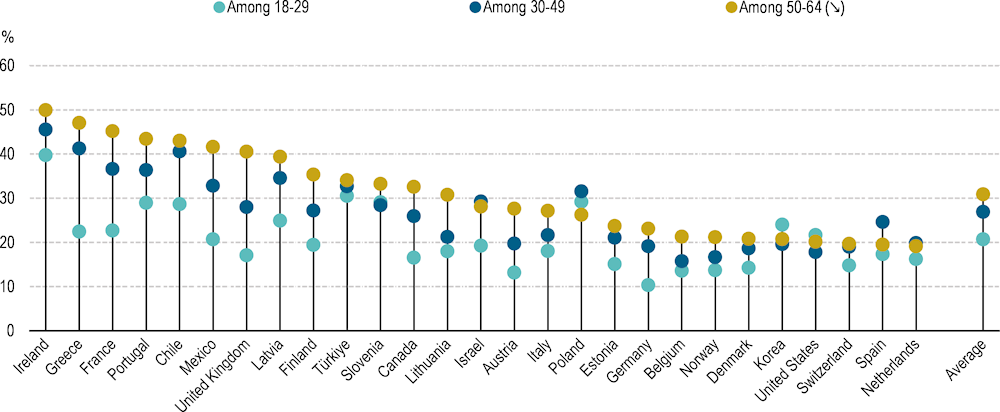

2.3. Perceived lack of access to healthcare is felt more keenly among older adults

Older adults are more likely to doubt that they could access good-quality and affordable healthcare than younger adults. On average across countries, 31% of 50‑64 year‑olds report that they do not think they would have access to good-quality and affordable public health services, compared with just 21% of 18‑29 year‑olds (Figure 2.8). The age gap is high in, for instance, Greece (25 percentage points), the United Kingdom (23 percentage points), and France (22 percentage points). Some countries have no statistically significant difference between older and younger adults, such as Korea, Switzerland, and the United States.

These age differences in perceived accessibility to healthcare also reflect the finding that older adults are more likely to report feeling worried about being able to access healthcare than younger adults. As seen in Chapter 1, 68% of 50‑64 year‑olds worry about accessing healthcare, compared with 60% of 18‑29 year‑olds. Widespread concerns about falling into ill health are also consistent with longer-term trends seen in previous waves of RTM (OECD, 2021[2]; OECD, 2019[5]).

Concerns about accessing healthcare may also have become more pertinent during and in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic. While health systems mobilised for COVID‑19, many other health services were disrupted, especially during periods of lockdown. Such disruptions included, for instance, screening and early detection services for cancer, elective and non-urgent surgery such as knee and hip replacement. This meant that waiting lists became longer, which could have contributed to more people feeling that they did not have good access to public health (OECD, 2022[48]). This will likely have directly affected older adults more than younger adults.

While fewer younger adults typically report disagreeing that they could access healthcare in RTM 2022, it is well-documented that young people in particular experienced deteriorations in mental health over the course of the pandemic (OECD, 2021[49]), which frequently coincided with more limited access to support services (OECD, 2022[48]).

Figure 2.8. Older respondents typically feel less confident that they could access good-quality and affordable healthcare compared to their younger counterparts

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think that my household and I have/would have access to good quality and affordable public services in the area of […], if needed.” Health (e.g. public medical care, subsidised health insurance, mental health support, etc.)”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Older adults also tend to be more worried than younger adults that the income support received from the government in case they fell ill would be enough. On average across participating countries, 54% of 50‑64 year‑olds feel their government would not provide them with sufficient income support when they are ill or have a disability (Figure 2.9). This can be compared to only 36% of 18‑29 year‑olds.4 There is substantial variation in age gaps across countries, with Estonia, Greece and Lithuania standing out at the upper end.

Figure 2.9. Similarly, older adults doubt that the income replacement from the government in case of bad health would be enough

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think that the government does/would provide my household and me with adequate income support in the case of income loss due to Illness/disability”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Notes

← 1. Education is described in the survey as “e.g. schools, universities, professional/vocational training, adult education.”

← 2. The Risks that Matter Survey (2022) defines non-standard workers as those in paid work (or temporarily away because of health reasons) either as self-employed or as an employee employed on a temporary contract or employed without a contract.

← 3. Pension replacement rates refer to indicators from Pensions at a Glance 2020. Data present net pension replacement rate from mandatory and voluntary contributions, for men at average wage in 2020.

← 4. Significant age differences remain even when controlling for other factors, such as gender, parental status, income level and work status in a logistic regression with country fixed effects.