RTM 2022 illustrates that governments are facing a dual challenge: they must deal both with the economic fallout from the ongoing cost-of-living crisis as well as the longer-term challenge of improving the access to and quality of healthcare services, including long-term care. While spending priorities line up with the key risks that respondents report in Chapter 1, governments should be careful to ensure that spending is put to effective use, with tangible and sustainable outcomes for target groups.

Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey

3. Dealing with immediate and long-running challenges

3.1. Respondents say that governments’ immediate priority should be to deal with the cost-of-living crisis

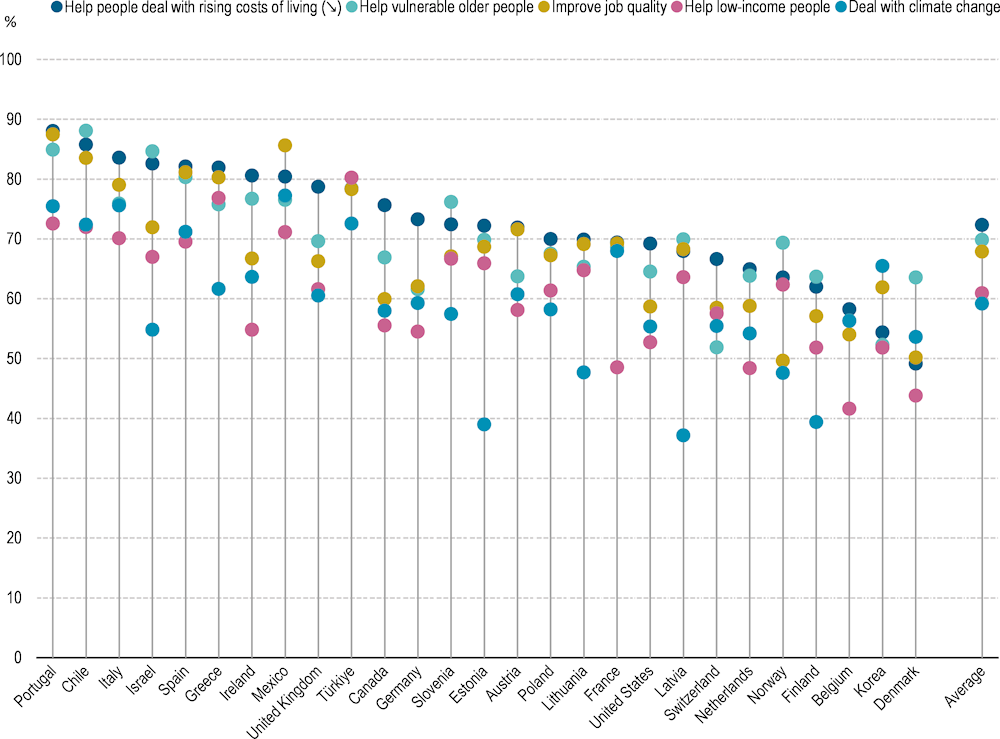

RTM 2022 asked respondents both about traditional spending priorities and urgent issues that governments should address today. When asked to think about urgent challenges faced by their countries today, a majority of respondents to RTM think governments should give a greater priority to helping people deal with the current cost-of-living crisis. 73% of respondents report that they think their government should prioritise “helping people deal with rising costs of living” more or much more in the coming year (Figure 3.1). Similarly, respondents also think that their government should prioritise supporting vulnerable older people and low-income people, groups which will have been disproportionately affected by the cost-of-living crisis.

By contrast, issues that are directly related to the COVID‑19 crisis, including addressing its longer-run mental and physical health effects, preventing or limiting new outbreaks of contagious illnesses, and helping parents adapt to their children’s fluctuating school and childcare situations, are less often considered areas of priority (excluded from the figure).

Figure 3.1. This year, respondents think that governments should prioritise helping people deal with the living cost crisis

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Data show the five categories of priorities that were the most commonly chosen on average across countries. Respondents were asked: “Thinking about global challenges today, to what degree should your government prioritise the following in the coming year: Improving job quality, e.g. by helping to improve wages or working conditions/Dealing with worker shortages/Preventing/limiting new outbreaks of contagious illnesses/Helping children recover from educational losses/Helping parents adapt to their children’s fluctuating school and childcare situations/Addressing the long-run mental and physical health effects of COVID‑19/Helping people deal with rising costs of living/Helping low-income people/Helping vulnerable older people/Dealing with climate change/Dealing with international security threats”. Respondents could choose between: “Prioritise much less”; “Prioritise less”; “Prioritise as it does now”; “Prioritise more; “Prioritise much more”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of responses who report “prioritise more” or “prioritise much more”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

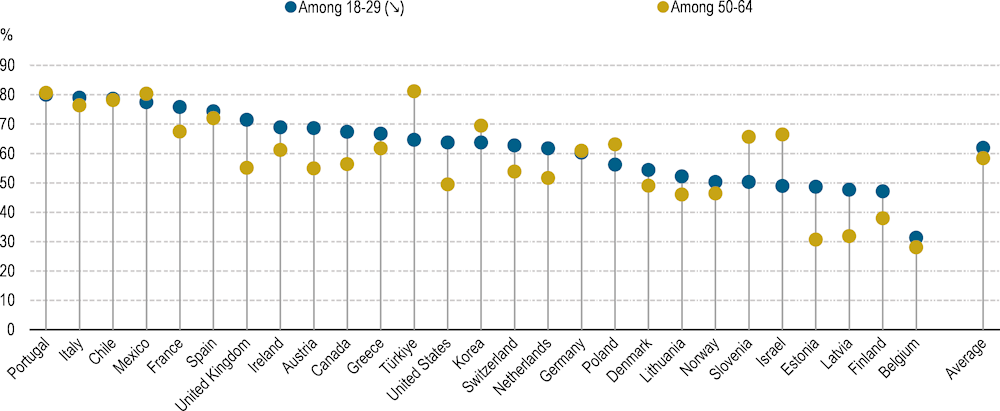

Box 3.1. Younger people think that the government should prioritise climate more than older people, but perhaps not by as much as would be expected

Climate change is seen as a high-priority policy area. In the RTM 2022 current events module, climate change is the fifth most commonly chosen area for higher government prioritisation, with 59% of respondents calling for government to prioritise the issue, on average across countries, which is comparable with findings from the OECD Trust Survey (OECD, 2022[34]). Women, people with tertiary-level education, and young people are more likely than their counterparts to think that climate is an important area for government to focus more attention on1. For instance, across countries, 62% of 18‑ to 29-year‑olds support more government action on climate, compared to the marginally lower 57% among 30‑ to 49-year‑olds and 58% among 50- to 64-year‑olds (Figure 3.2). Some countries, such as Estonia, Latvia, the United Kingdom and the United States have greater age gaps, while other have more older people reporting greater concerns than younger people. It is noteworthy that there is typically a consensus across age groups in countries where support is generally high, such as in Chile, Italy, Mexico and Portugal.

Nearly half (48%) of respondents on average across countries believe that their government is not doing enough to tackle climate change when bearing in mind the costs and benefits of climate change policies. A successful green transition will involve many policy areas across government departments and agencies, and social policy could play an important role in making sure that opportunities and challenges are shared across groups. In particular, social policy may play a key role in the long run to support those who may suffer losses from labour market friction and structural change caused by climate change mitigation and adaptation policies. Across countries, 62% of respondents worry about job losses in carbon-intensive industries and 88% of respondents are concerned about price increases for energy, food and other goods.

Figure 3.2. Younger adults think that the government should prioritise climate only marginally more than older adults

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Thinking about global challenges today, to what degree should your government prioritise the following in the coming year: Dealing with climate change. Respondents could choose between: “Prioritise much less”; “Prioritise less”; “Prioritise as it does now”; “Prioritise more”; “Prioritise much more”; “Can’t choose”. Data presents the share of respondents who chose “prioritise more” or “prioritise much more”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2020 and 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Notes: The statistics in the last paragraph of this box are based two questions. Respondents were asked: “Do you think that your government is doing enough, not enough, or too much to tackle climate change – bearing in mind the costs and benefits of policy action?” Respondents could choose between: “Not enough”; “Enough”; “Too much”; “Don’t know”. Respondents were also asked: “The government can take a number of environmental regulatory steps to reduce your country’s contribution to climate change, such as building up green infrastructure, emissions limits and carbon taxes. But these environmental measures to mitigate climate change can have social and economic consequences on people today. Keeping in mind the effects of different environmental policies to combat climate change, what degree are you concerned about the following possible economic outcomes in your country? Rising energy/fuel costs/Rising costs of food and other goods/A loss of jobs in industries that have negative environmental impacts, such as coal, mining and oil extraction/Having enough skilled workers to fill demand for green jobs/Housing relocation away from environmentally degraded spaces/Lower economic growth/Costs of (mandatory) climate‑neutral adaptation of heating and cooling systems (e.g. renewable energy systems, energy efficiency renovations)”. Respondents could choose between: “Not at all concerned”; “Not very concerned”; “Somewhat concerned”; “Very concerned”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned”. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

1. There is high support for prioritising climate more across groups. However, when controlling for various factors, women are a little more positive than men and those with tertiary-level education are a little more positive than others. Those working in sectors directly affected by the green transition (Agriculture, forestry and fishing; Mining and quarrying; Manufacturing; Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply) are marginally less likely to want government to do more in this area compared to those not working in directly impacted sectors.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

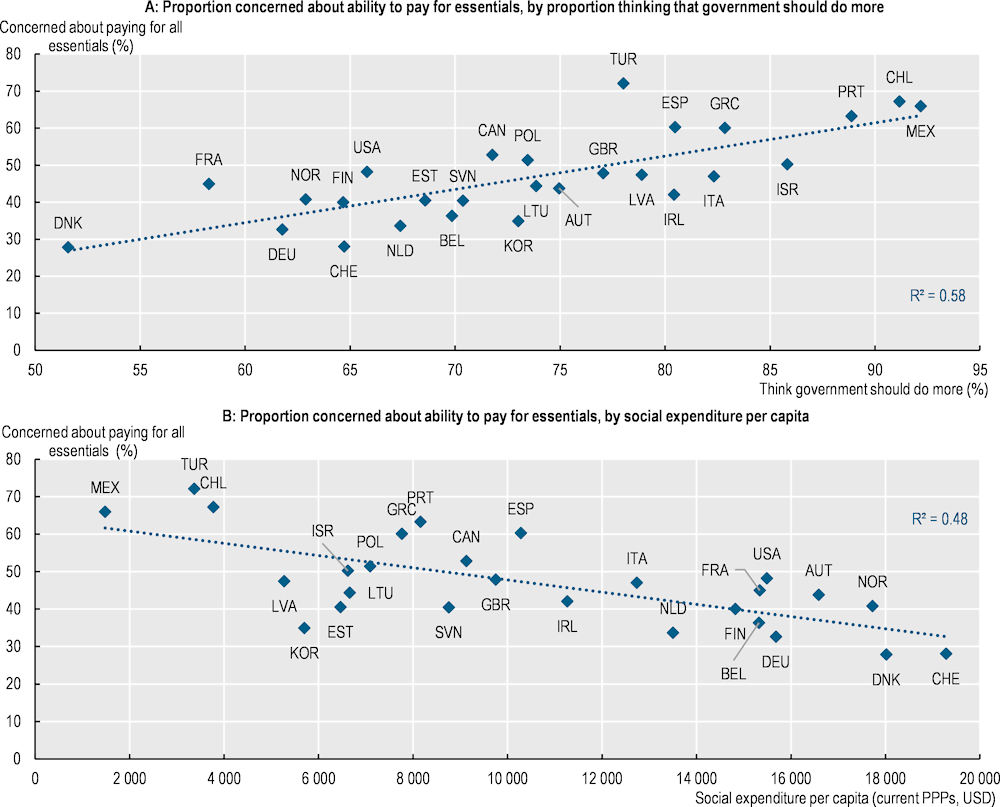

The desire for governments to do more to support respondents’ economic security is higher in countries with higher proportions of financially precarious respondents. Overall, 74% of respondents think that their government should be doing more or much more to ensure their economic and social security and well-being.1 Cross-nationally, where higher proportions of respondents want the government to do more to ensure their household’s social and economic security and well-being, higher proportions of respondents are concerned about paying for essentials (food, housing, energy, and paying down debt) (Figure 3.3, Panel A).

Similarly, more respondents are now worried about costs of living in countries where the social safety net was weaker in 2019. Fewer respondents report being worried about their household’s ability to afford essential spending on food, housing, energy and paying down debt where social expenditure (e.g. on health, income support, and family benefits) was high before the cost-of-living crisis (Figure 3.3, Panel B).

Figure 3.3. Where concerns about paying for essentials are widespread, so is the perceived need for more government intervention

Note: Social expenditure (Panel B) refers to the total of public and private mandatory contributions per country. Respondents were asked: “In thinking about costs of living in 2022, how worried are you about your household’s ability to pay for: Essential food products/Housing costs, i.e. rent or mortgage payments/Home energy costs, i.e. utility bills such as electricity and gas/Fuel for your personal vehicle (if you drive)/Public transportation costs, e.g. bus, trams, metros and trains (if you take public transit)/Rising costs of paying off/paying down debt/Cost of childcare or schooling (if relevant)”. Respondents could choose between: “Not at all concerned”; “Not so concerned”; “Somewhat concerned”; “Very concerned”; “Can’t choose”. For Panel A respondents were asked: “Do you think the government should be doing less, about the same, or more to ensure your economic and social security and well-being?”. Respondents could choose between: “Government should be doing much less”; “Government should be doing less”; “Government should be doing about the same as now”; “Government should be doing more”; “Government should be doing much more”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who indicated “somewhat concerned” or “very concerned” to all four of the response choices, food, housing, home energy and debt and the share of respondents who indicated that “government should be doing more” or “government should be doing much more”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Overall, Chapter 2 shows that respondents have little faith in government assistance and many report that they would cope with financial difficulties by seeking additional work or support from family and friends, taking on debt, or relying on social safety nets. These findings suggest that addressing financial insecurity should be a key component of social policy.

At the same time, the rapid increase in the price of essentials is a cost that governments, companies and individuals cannot absorb independently, but rather should be shared across actors (OECD, 2022[50]; OECD, 2022[1]). Balancing costs across actors can help the most vulnerable households cope with inflationary pressure. OECD governments have at least two relatively easily implementable social policy tools to help vulnerable households cope with inflationary pressure (OECD, 2023[4]; OECD, 2023[3]; OECD, 2022[21]; OECD, 2023[24]).

First, governments can assist the most vulnerable households cope with rising costs by ensuring that means-tested support and other transfers that support the most vulnerable are regularly adjusted to ensure that they keep operating as intended. This can help cushion inflationary impacts on households that have affordability concerns (OECD, 2022[21]; OECD, 2023[24]; OECD, 2023[4]).

Second, where governments already target cash transfers to lower-income groups, they can more easily provide ad hoc support to vulnerable households. Scaling up existing benefits is typically more effective – both in terms of poverty alleviation and inflation outcomes – than general cash transfers or price support measures (OECD, 2022[21]; OECD, 2023[4]).

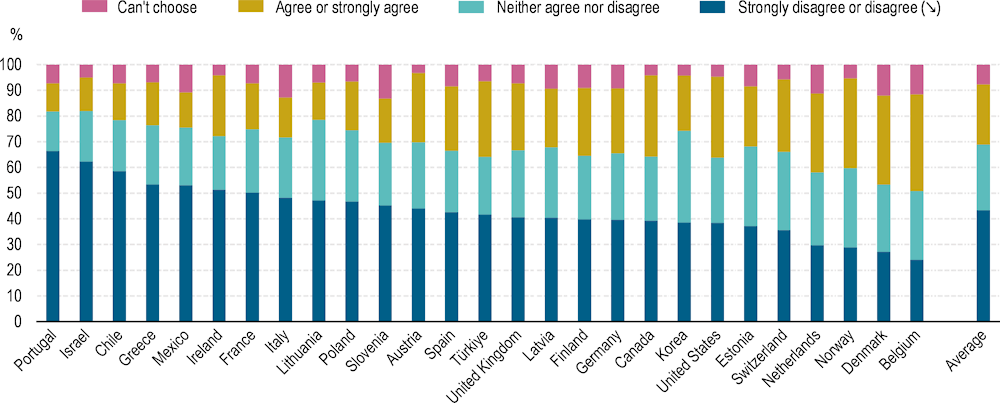

3.2. Few think they receive a fair share of benefits, with many thinking the rich should pay more

Across countries, around four in ten (43%) feel that they do not receive a fair share of public benefits, given the taxes and contributions they pay. One‑quarter (25%) is ambivalent and just under one‑quarter (23%) think that they are receiving a fair share. Dissatisfaction rates do not vary consistently by income quintiles, but there are significant differences across countries.

Dissatisfaction is strongest in Portugal and Israel where over 60% of respondents report not thinking that they get what they are due. At the other end of the spectrum, Belgium, Denmark and Norway have the highest proportions of satisfied respondents. For instance, in Belgium, 38% of respondents agree that they are getting their fair share.

Figure 3.4. About four in ten overall do not feel that they receive their fair share of public benefits

Notes: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I feel that I receive a fair share of public benefits, given the taxes and social contributions I pay and/or have paid in the past.” Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”, and “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Across countries, respondents want more redistributive government intervention. Overall, 60% of respondents say that they want their governments to tax the rich more than they currently do in order to support the poor (Figure 3.5). Across countries, older respondents are more likely to support more redistribution than their younger peers, with 64% of 50‑64 year‑olds reporting this, compared with 52% of 18‑29 year‑olds. While using words such as “rich” and “poor” is somewhat emotive and does not highlight to respondents whether they would practically fall into either of these categories, there is some evidence that respondents react to the situation in their country. The Main Findings report on Risks that Matter 2020 found that there is a slight positive correlation between the degree of income inequality in a country, measured by the Gini coefficient, and demands for more redistribution and more progressive taxation (OECD, 2021[2]). This suggests that people on average respond to inequality with a reported desire for more redistribution.

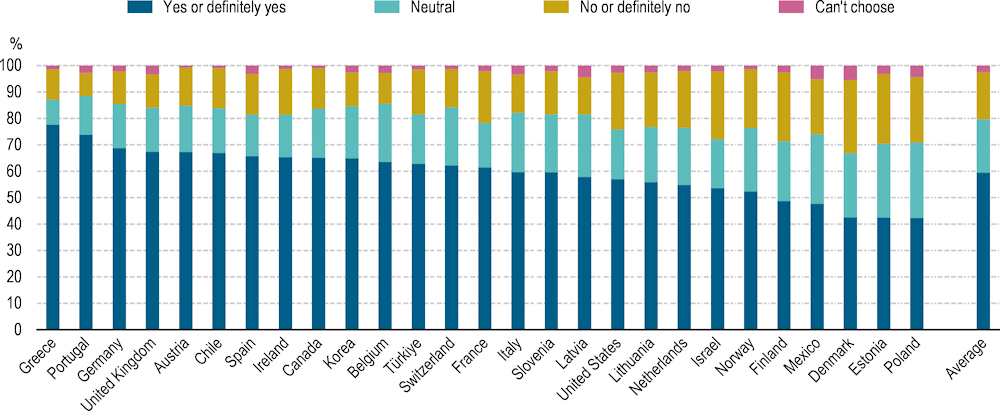

Figure 3.5. On average three in five support taxing the rich more

Notes: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Should the government tax the rich more than they currently do in order to support the poor?”. Respondents could choose between: “Definitely no”; “No”; “Neutral”; “Yes”; “Definitely yes”; “Can’t choose”. Data present share of respondents choosing “definitely no” or “no”, and “definitely yes” or “yes”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

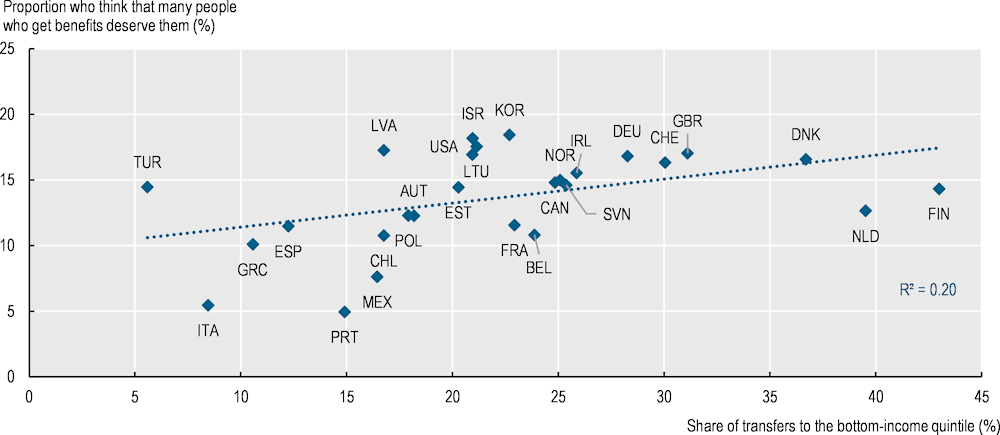

Targeted cash transfers can be a way for governments to redistribute money from the overall tax budget toward financially vulnerable households. Countries with more targeted transfers tend to have slightly larger shares of respondents who think benefits are fairly distributed (Figure 3.6). While there are other factors influencing the perception that people undeservedly receive benefits, potentially including perceptions about benefit fraud, corruption, and others, this may indicate that more redistributive transfers play a role in the overall satisfaction with the transfer and benefit system.

Figure 3.6. Countries with more targeted transfers have more people who think benefits are distributed fairly

Note: Data on cash transfers refer to those aged 18‑65. Data on cash benefits refer to 2019 or latest year. Transfers include all public social cash benefits. Incomes refer to equivalised disposable household income. Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “Many people receive public benefits without deserving them.” They could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

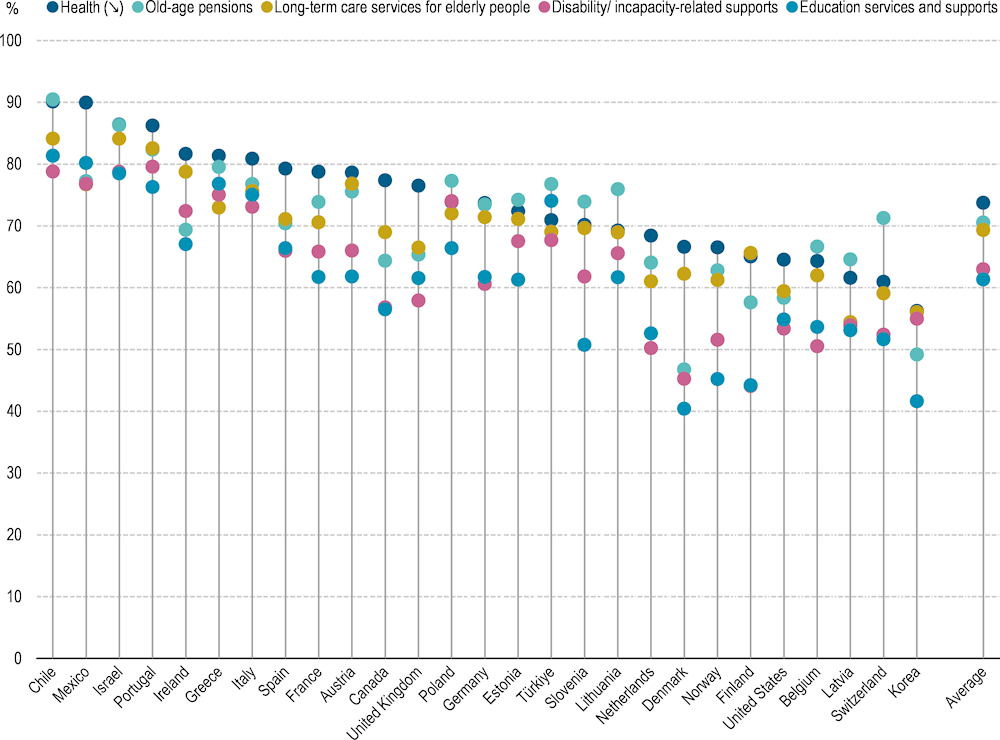

3.3. Spending should focus on healthcare and support for older adults

The 2022 Risks that Matter survey asks respondents specifically about their priorities for government spending, with and without putting a price tag on the cost. Respondents report similar priorities whether specific costs are mentioned or not, albeit overall support is slightly lower when a specific cost to the respondent and their family is mentioned. The top-three priorities for more government spending are health, old-age pensions and long-term care services for elderly people. These top-three priorities are consistent with the top perceived risks over the coming two years, which include the worry to not be able to access good-quality healthcare, falling ill or becoming disabled, and not being able to access long-term care for elderly family members (Chapter 1).

Support for more government spending on social policy areas remains high even when respondents are asked to take potential, but undefined, costs and benefits into account. When asked to think about the taxes they might have to pay and the benefits they might receive, 74% of respondents report that they think government should increase spending on health. This figure is 71% for old-age pension and 69% for long-term care services for older people (Figure 3.7). Support for more spending in these areas is greater in countries like Chile, Israel, and Mexico and lower in traditional welfare states like Denmark and Norway. Support is lowest in Korea, Latvia, and Switzerland (although Switzerland stands out with some support for more spending on pensions).

The desire for increased healthcare funding – not least in the long-term care sector – is part of a longer-term trend, as it emerges as a key priority in both the 2018 and the 2020 waves of the RTM survey (OECD, 2019[5]; OECD, 2021[2]). Ensuring adequate long-term care in particular is becoming increasingly important given the trend of ageing societies (OECD, 2023[51]).

More funding, higher wages, and better work conditions for staff can help support the necessary expansions of long-term care services. For example, dissatisfaction with long-term care services has been found to be negatively correlated with government spending per capita on long-term care (OECD, 2019[5]). Public investments should focus on providing adequate wages, a safe work environment, and promoting greater social recognition in order to support the long-term care sector to deal with ageing populations (OECD, 2023[20]).

Figure 3.7. When considering the taxes they might have to pay and the benefits they may receive, respondents want to see more spending on healthcare and support for older adults

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Data show the five policy areas that were the most commonly chosen on average across countries. The following areas are not included in the chart: public safety, housing supports, public transport, family supports, income supports, employment supports, unemployment supports. Respondents were asked: “Thinking about the taxes you and your family might have to pay and the benefits you and your family might receive, would you like to see the government spend less, spend the same, or spend more in each of the following areas? Family supports (e.g. parental leave, childcare benefits and services, child benefits, etc.)/Education services and supports (e.g. schools, universities, adult education services, etc.)/Employment supports (e.g. job search supports, skills training supports, better access to funds to start a business, etc.)/Unemployment supports (e.g. unemployment benefit, etc.)/Income supports (e.g. minimum-income benefits)/Housing supports (e.g. social housing, housing benefit, etc.)/Health (e.g. public hospitals, subsidised health insurance, mental health services, etc.)/Disability/incapacity-related supports (e.g. disability benefits and services, long-term care services for persons with disability, community living resources, etc.)/Old-age pensions/Long-term care services for elderly people (including e.g. home, community-based and/or institutional care)/Public safety (e.g. policing)/Public transport”. Respondents could choose between: “Spend much less”; “Spend a little less”; “Spend the same as now”; “Spend a little more”; “Spend much more”; “None”; “Can’t choose”. Data present share of respondents choosing “spend a little more” or “spend much more”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

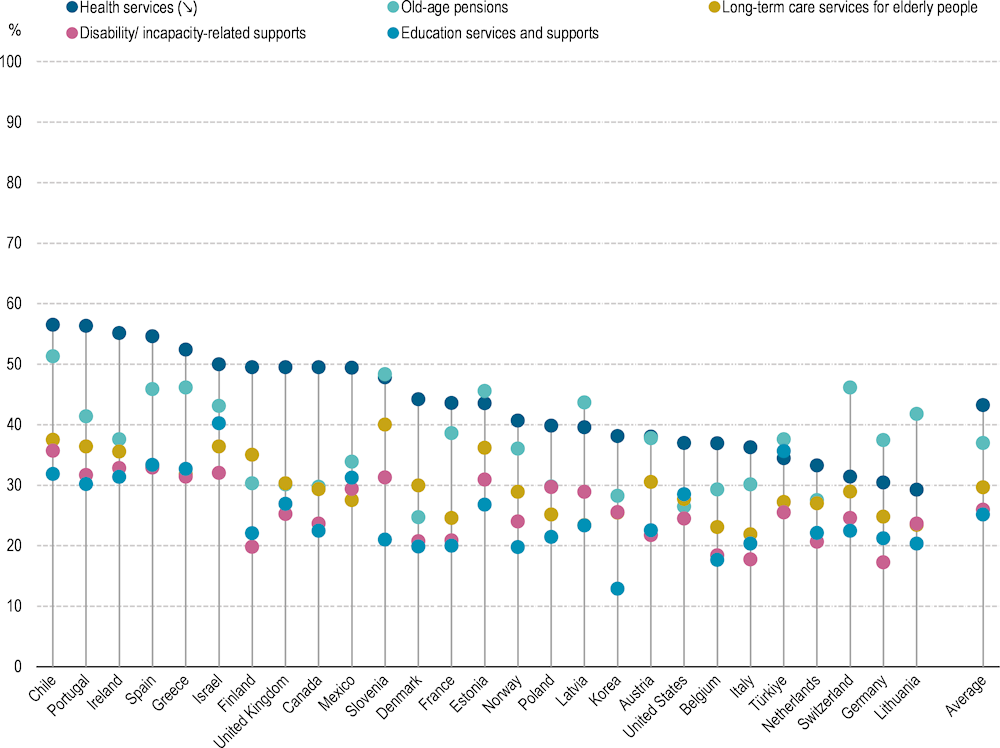

Support for social spending declines across all policy areas when respondents are primed to think about contributing an additional 2% of their own income, but the priority areas remain the same. Even when thinking about paying an additional 2% of their income, 43% of respondents say that they would spend some of their income in additional taxes for better provision and access to health services, whereas this figure is 37% for old-age pensions, and 30% for long-term services for older people (Figure 3.8). Improved access to health remains the most commonly selected policy area, with a majority of respondents reporting that they are willing to forgo 2% of their income for better healthcare in five countries: Chile, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain.

When looking at pensions, it is noteworthy that relatively large shares of respondents in Switzerland (and to a smaller extent, in Germany and Lithuania) support better provision and access to old-age pensions, when support for other social policy areas is relatively low. In Switzerland, the special focus on old-age pensions in RTM corresponds with relatively large income gaps in poverty rates among those aged 65 and over and working-age people (OECD, 2019[52]). Indeed, in Switzerland, 46% of respondents report being willing to pay an additional 2% of their income for better old-age pension provision, which is on par with support in Greece (46%), and only lower than support in two other RTM countries: Chile (51%) and Slovenia (48%) (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8. Support is lower, but the top five issues remain the same, when respondents are asked to make an increase of 2% of their income in tax and social contributions for better access

Note: Data is sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Data show the five policy areas that were the most commonly chosen on average across countries. The following areas are not included in the chart: public safety, family supports, housing supports, public transport, unemployment supports, income supports, employment supports, not willing to spend an extra 2% on any of these things. Respondents were asked: “Would you be willing to pay an additional 2% of your income in taxes/social contributions to benefit from better provision of and access to: Family supports (e.g. parental leave, childcare benefits and services, child benefits, etc.)/Education services and supports (e.g. schools, universities, adult education services, etc.)/Employment supports (e.g. job-search supports, skills training supports, better access to funds to start a business, etc.)/Unemployment supports (e.g. unemployment benefit, etc.)/Income supports (e.g. minimum-income benefits)/Housing supports (e.g. social housing, housing benefit, etc.)/Health services (e.g. public hospitals, subsidised health insurance, mental health services, etc.)/Disability/incapacity-related supports (e.g. disability benefits and services, long-term care services for persons with disability, community living resources, etc.)/Old-age pensions/Long-term care services for elderly people (including e.g. home, community-based and/or institutional care)/Public safety (e.g. policing)/Public transport/I would not be willing to spend an extra 2% on any of these things/Can’t choose/don’t know”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm.

Financial insecurity and health-related issues are key areas that respondents worry about and that they would like to see more government spending on, but averages hide differences across age groups that can be relevant for policy makes. Policies aimed at reducing the cost of living or increasing access to financial support may be particularly effective in addressing the concerns of young adults, who may be more vulnerable to economic shocks. By contrast, policies aimed at addressing healthcare access and affordability may be more relevant for older adults, who may be more likely to experience health-related expenses and have greater healthcare needs.

Gender differences in spending priorities are overall small and often non statistically significant. The largest average differences across countries can be seen for public transport and public safety, where more men report being supportive of spending more on this (by around 5 percentage points in both cases). Health services are the most commonly chosen area for further spending among both men and women when asked to contribute 2% in taxes. Slightly more women (45%) than men (41%) say that they would like this, with the differences being greatest in Finland (14%), Estonia (13%), and Denmark (13%).

3.4. It is not just about spending more, care should be taken to make sure investments are effective

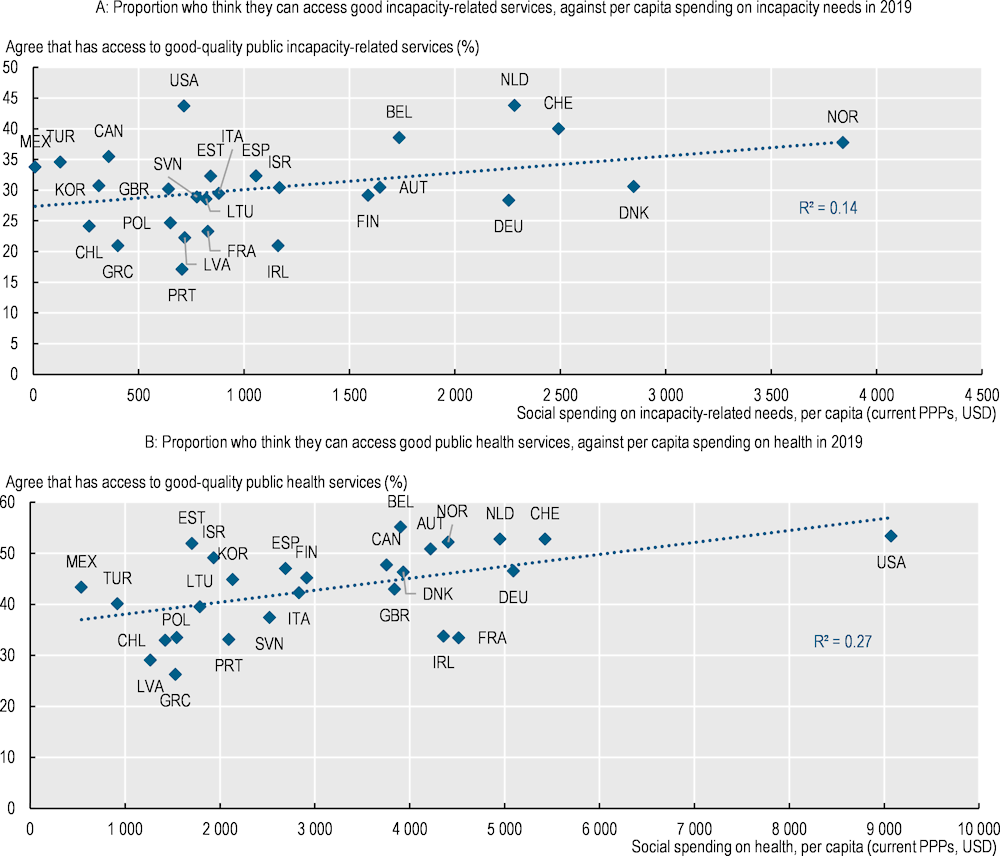

Even though the RTM survey asks respondents about areas where they would like to see more government investment, it is important that governments also consider how to ensure that their spending has maximum impact and is palpable to target populations. It is possible to match key areas of interest for respondents against actual social spending per capita in that area. Figure 3.9 considers respondent satisfaction with, and actual government spending on, the areas of incapacity-related services (Panel A) and public health services (Panel B). In relation to incapacity-related services in particular, the correlation between perceived accessibility/quality and actual spending is weak. This suggests that there are other important factors that impact whether government spending actually results in perceived quality of services.

Governments may consider making sure spending is effective, using appropriate methods of policy evaluation, to make sure interventions have the desired effect. For instance, in environments with high inflation, it is important to recognise that governments, companies and workers cannot absorb the costs of rising prices independently. Sharing costs fairly across these actors can help vulnerable households cope with inflationary pressure. One important social policy tool governments can use is inflation indexing. Regular adjustments of benefits to inflation, as recently introduced for minimum-income support in Latvia and for pensions in Spain, can help cushion the impacts of inflation on households with the greatest affordability concerns (OECD, 2023[4]).

Governments can also work to ensure that government interventions work for the target populations, they may consider integrating monitoring and evaluation methods in reforms to existing programmes or in the design of new ones. They should also consider whether new policy proposals are supported by a strong evidence base. It is usually possible to build in structures for robust evaluations in the implementation phase of interventions, to allow for rigorous conclusions to be drawn regarding effects on populations of interest.

Figure 3.9. Satisfaction levels are not just about spending

Note: Respondents were asked: “Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think that my household and I have/would have access to good quality and affordable public services in the area of Health (e.g. public medical care, subsidised health insurance, mental health support, etc.) […], if needed.” Health (e.g. public medical care, subsidised health insurance, mental health support, etc.)/Disability/incapacity-related needs (e.g. disability benefits and services, long-term care services for persons with disability, community living resources, etc.). Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: OECD Risks that Matter Survey 2022, http://oe.cd/rtm,

Note

← 1. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “Do you think the government should be doing less, about the same, or more to ensure your economic and social security and well-being?”. Respondents could choose between: “Government should be doing much less”; “Government should be doing less”; “Government should be doing about the same as now”; “Government should be doing more”; “Government should be doing much more”; “Can’t choose”. Data refer to the share of respondents who indicated that “government should be doing more” or “government should be doing much more”. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.