This chapter presents the rationale and building blocks for the Mining Strategy of Well-being for the Region of Antofagasta 2023-2050, which aims to address mining-specific challenges and opportunities in the region and support higher well-being standards for all people living in the Antofagasta region. The chapter first outlines the relevance of developing a regional mining strategy, especially with the ongoing decentralisation process in Chile. Second, it summarises the process of developing this strategy, its objectives and the timeframe of strategic projects. Finally, it provides guidance on a governance mechanism for the long-term continuity and monitoring of the strategy and describes the allocation of roles for regional stakeholders and funding sources.

Mining Regions and Cities in the Region of Antofagasta, Chile

4. Towards a Mining Strategy of Well-being for the Region of Antofagasta

Abstract

Policy takeaways

Assessment

Mining development has generated important wealth for Antofagasta and the country but these benefits have not been equally distributed across the region, leaving many communities behind across a wide range of well-being indicators (see Chapters 2 and 3). Despite public and private initiatives to better translate mining wealth into benefits for the communities, the region has lacked an integrated co‑ordination mechanism to align efforts and policies among levels of governments and companies and produce long-lasting changes in well-being standards. This has negatively impacted the region’s attractiveness for businesses and people raising families.

The ongoing decentralisation process in Chile provides a new opportunity for the region to attain a more sustainable and inclusive future. For the first time, the region benefits from a newly elected regional governor with new administrative and planning tools, whose responsibilities and mandate are to support the interests and aspirations of citizens from the region. In parallel, Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in the region have strengthened their voices and governance for more decision-making power and accountability. Against this backdrop, the mining sector is increasingly under international and local pressure to adapt to societal demands and global climate agreements to reduce its impact on the environment and improve local outcomes.

A long-term plan with formal co‑ordination and monitoring is needed to ensure that the region can materialise future investments in minerals and energy in a sustainable manner while ensuring greater well-being standards along social and environmental dimensions. The Mining Strategy of Well-being for the Region of Antofagasta 2023-2050 (hereafter the Mining Strategy) embodies this coherent long-term plan. For its elaboration, different parts of society were involved to reach common agreements and identify strategic objectives and projects. A multi-stakeholder governance mechanism is warranted to help monitor the implementation of this strategy and ensure its continuity beyond political cycles. Likewise, the national government and its national agencies in the region need to support the institutional capacity to implement this strategy successfully, in alignment with the national mining strategy and the sustainable development of Chile.

Takeaways

The recommendations below provide the building blocks of the Mining Strategy, with suggested long-term objectives and governance mechanisms. The construction of the strategy benefitted from more than 80 meetings with stakeholders in the region, including representatives from the private and public sectors, civil society and Indigenous communities, academia and local businesses, who provided their development priorities and feedback on the objectives, structure and governance of the Mining Strategy for the region of Antofagasta.

To improve the economic, social and environmental well-being standards in Antofagasta while promoting a more competitive and environmentally responsible mining sector, the regional government of Antofagasta needs to:

Formalise and implement the Mining Strategy with concrete objectives and a timeframe of strategic projects that involve and consider the needs of different regional stakeholders. To this end, the regional government should:

Recognise in the Mining Strategy the need for a new pact among communities and the private sector in the region of Antofagasta, to rebuild trust within the region and reach common agreements for improved development. This new pact would benefit from the recognition that more needs to be done to improve well-being standards in the communities where mining takes place but also that the mining sector plays a strategic role in the development of the region of Antofagasta.

Ensure the Mining Strategy is a regional government strategy with a long-term vision, common objectives and a clear timeframe for strategic projects. All of these elements should be based on the priorities provided by regional stakeholders. This involves:

Adopting a vision that sets the long-term and aspirational goal for the region with the aim of increasing well-being standards in economic, social and environmental dimensions. The vision can be accompanied by common agreements to reach compromises and align regional efforts.

Setting strategic objectives to address the main priorities identified across the region and reach the vision for the region in 2050. These objectives could be set across the five following areas:

Improve the well-being of local communities and Indigenous peoples.

Increase the participation of regional businesses in the mining value chain.

Strengthen skills and the regional knowledge ecosystem.

Improve governance for a more productive mining sector.

Rehabilitate the environment.

Implement short- and medium/long-term strategic projects to attain each of the objectives of the strategy. Several strategic projects have been identified throughout different multi-stakeholder meetings in the region.

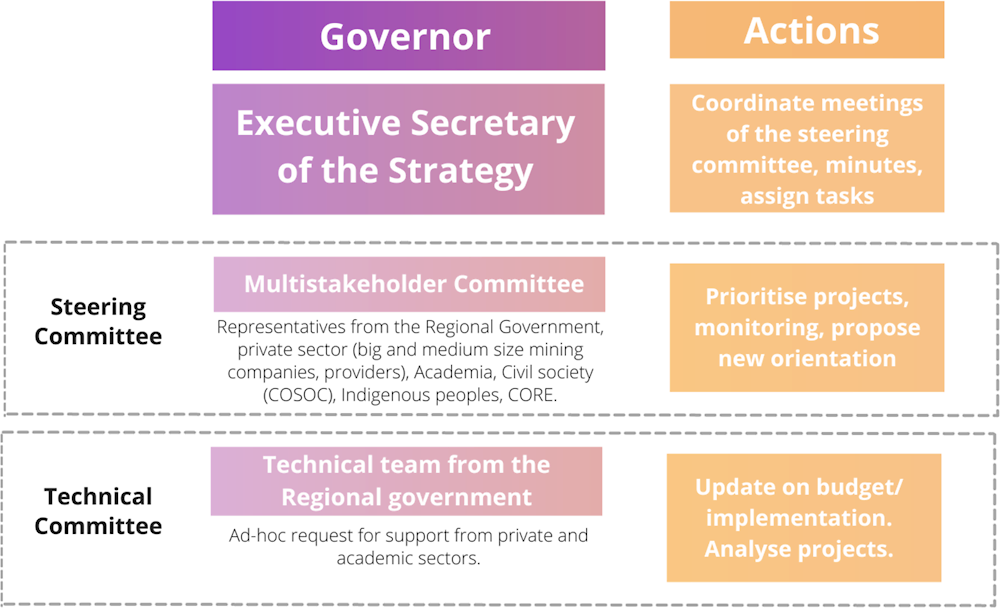

Establish a governance mechanism to monitor progress and ensure the sustainability of the Mining Strategy over the long run and beyond government cycles. This mechanism could benefit from the following elements:

A formal public official in the government co‑ordinating the strategy and ensuring its implementation and continuity, with a defined budget and a team for operation and co‑ordination.

A steering committee in charge of prioritising projects, rendering accounts of monitoring and evaluation, and proposing new orientations to the strategy. It should be composed of representatives of relevant actors in the region (private and public sector, civil society and Indigenous communities), with periodic rotation to expand possibilities of participation and representation (e.g. two years) and a consensus-based decision process.

A technical committee in charge of overseeing the projects, providing updates on the progress of the project and budget, and responding to other requests from the steering committee. This technical committee is made up of an executive secretary and a team of professionals in collaboration with personnel from academia and the private sector.

Ensure the Mining Strategy upholds Indigenous peoples’ rights and promotes meaningful participation in decision making and prior and informed consent in designing and implementing relevant strategic projects for these communities.

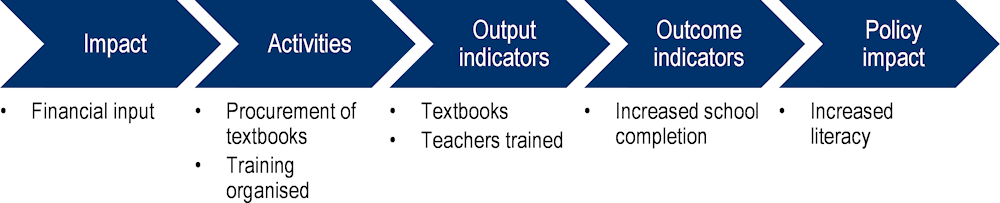

Define a monitoring framework with impact indicators to monitor the long-term policy impact of the Mining Strategy as well as outcome indicators to measure the attainment of objectives and output indicators to measure the implementation. This monitoring framework could also include horizontal performance indicators that can account for complementarity effects to co‑ordinate actions across different parts of the regional government and national agencies in the region.

Ensure a formal channel of communication and involvement of regional stakeholders on the construction, progress and changes of the Mining Strategy. This involves:

Including on the Mining Strategy webpage a summary of the process with different parts of society, agreed-upon objectives and strategic projects, with clear visualisation tools to show the progress of these projects.

Mapping and publicly reporting concrete information on the different environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) initiatives of mining companies in the region to improve transparency and co‑ordination.

Establishing annual public reports on the progress of the strategy via social media or public gatherings to reach the entire population.

Support the institutional modernisation and capacity of the national agencies operating at the regional level. The national government is crucial to help ensure the successful implementation of the regional Mining Strategy and maintain a competitive and sustainable mining sector that keeps contributing to national fiscal income and growth and helps attain national climate goals. To this end, the national government should:

Co‑ordinate with the regional government of Antofagasta to identify institutional needs in the region and define methods to increase the capacity and upgrade the Regional Ministerial Secretaries (SEREMIs) – especially the SEREMI of the Environment and the SEREMI of National Goods – and the Superintendence of the Environment.

Introduction

As depicted in the previous chapters, Antofagasta is a global player in the mining industry, especially in copper and lithium. Its traditional know-how in mining operations, presence of rich geological resources, a mature mining ecosystem composed of leading mining companies, suppliers, universities with mining expertise, organised civil society actors and a recently strengthened regulatory framework with greater regional decentralisation make Antofagasta highly attractive for ongoing and future mining activities.

The mining sector contributes to the bulk of Antofagasta’s gross domestic product (GDP, 72% in 2022), representing 90% of its exports. This sector has contributed to placing Antofagasta as the second Chilean region with the highest income per capita and highest foreign direct investment. The region is also a significant contributor to the national economy, accounting for 39.4% of Chile’s total exports and contributing to 8.8% of the national GDP despite its population representing only 2.2%.

This prosperity, however, has not reached everybody in the region and has not fully translated into greater quality of life for its inhabitants. There are a number of challenges that remain across various dimensions of well-being (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Well-being challenges in the Antofagasta region

|

Economy |

Higher unemployment rate (9.6% in 2021) than the national average (9.1%) and the OECD benchmark of mining regions (7%) |

|

Higher income inequality (Gini coefficient of 0.51 in 2019) than the national average (0.46) |

|

|

Social |

The lowest life expectancy (79.2 years) among Chile’s 16 regions |

|

The fifth lowest life satisfaction among Chilean regions and in the bottom 22% across all OECD regions |

|

|

Lack of parks and green areas for recreation and leisure activities |

|

|

Environment |

38% more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per unit of electricity generated than the OECD benchmark of mining regions |

|

Concerns and lack of information about mining impacts on inland water, air pollution and biodiversity |

The region of Antofagasta is currently undergoing a number of transitions that can reshape the effect of mining on regional development. First, the region is on the verge of a significant flow and interest of investment to modernise and expand existing mining operations, mainly copper, and to increase exploration and production of non-traditional minerals, such as lithium. Second, mining companies are increasingly adapting to the green and digital transitions, with projects to increase the use of renewable energy sources (solar and wind), desalinated water and automation for mining operations. Finally, the ongoing decentralisation process in Chile has allowed, for the first time in history, the democratic election of a regional governor with new administrative and strategic capabilities.

These transitions can bring new opportunities for local businesses and workers to participate and benefit from a more sustainable value chain. Nevertheless, without proactive planning, new developments and green mining initiatives can lead to few benefits locally, creating additional challenges, for example, in the co‑ordination of water desalination plans and land use for solar and wind energy projects.

A long-term plan with formal co‑ordination and monitoring is needed to ensure that the investments in the minerals and energy mining sector can materialise in a sustainable manner while ensuring greater well‑being standards along social and environmental dimensions. This chapter presents the rationale and the building blocks for the development of that long-term plan set up by the regional government, namely the Mining Strategy of Well-being for the Region of Antofagasta 2023-2050 (hereafter the Mining Strategy).

Why a Mining Strategy of Well-being for the region of Antofagasta?

Across other OECD mining regions, mining strategies are developed to meet multiple objectives, which go beyond improving the competitiveness of the mining sector itself and also look at improving the liveability of people in the region.

The region of Antofagasta has a particular opportunity to mobilise its mineral wealth and industrial base to benefit from the increasing global demand for minerals and support the development of renewable energy technologies in the next decades.

However, the expected development of the mining sector driven by the global demand for minerals in the coming years must ensure more sustained benefits to the people and economy in the region. This requires a different way of governing mining, with a guiding framework that supports the competitiveness of the regional mining sector but also ensures that the wealth of this industry generates jobs and new local businesses and – above all – improves the attractiveness of living in the communities of Antofagasta.

The Mining Strategy can be the roadmap to mobilise the regional assets and improve the competitiveness of the mining sector to make the most of the digital and green trasitions with the aim to deliver greater well‑being standards to its inhabitants. With this in mind, the following are the main reasons for developing a mining strategy for the region of Antofagasta.

Making the most of global megatrends and transformations affecting the mining sector

Global megatrends, including demographic change, climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy, as well as digitalisation and automation, are bringing new challenges and opportunities to the development of mining regions (Table 4.2). For example, technological change and digitalisation can increase productivity and sustainability in mining activities but might also affect demand for local workforce.

Table 4.2. Opportunities and challenges of megatrends for the mining industry and regions

|

Opportunities |

Challenges |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Changes in demographic trends (population ageing and migration) |

|

|

|

Climate change and environmental pressures |

|

|

|

Technological innovation (e.g. digitalisation, automation, decentralised energy) |

|

|

In this context, the mining sector itself is also undergoing transformations. On the one hand, the industry is under increased pressure to reduce its impact on the environment and GHG emissions to meet global climate agreements. On the other, mining companies face a context of increasing competition with decreasing qualities of ore that are more difficult to access. Facing both transitions requires mining companies to invest in new technologies and processes and collaborate with governments to agree on environmental plans.

Automation is advancing significantly in the region. For example, Antofagasta Minerals operates a mining pit at the Centinela mine with almost an entire fleet of autonomous trucks (11), for which it trained about 100 workers (e.g. former drivers) in tasks needed for the autonomous operation, including monitoring and maintenance of the trucks or Global Positioning System (GPS) site mapping. Likewise, BHP currently has 6 drilling rigs and 4 autonomous trucks in operation and expects to gradually incorporate 52 trucks with autonomous technology by 2025.

Antofagasta is uniquely positioned to emerge as a global leader in responsibly sourced minerals, crucial for a low-carbon future. The region benefits from abundant geological resources, with some of the critical minerals for the green transition such as copper and lithium, and a well-established mining ecosystem comprising top mining companies, knowledgeable suppliers, mining-focused universities and a young workforce.

While the demand for minerals like copper and lithium is set to skyrocket, consumers, civil society, governments and international organisations are increasingly asking for mineral production that is carried out in a more climate-responsible manner. Antofagasta can leverage its renewable energy potential and advance the infrastructure of water desalination to play a pivotal role in showing a more sustainable way to mine. This future, in turn, will contribute to Antofagasta’s continued development by creating long‑term demand for its mining products, technology and services.

However, the mining sector is facing increasing challenges in maintaining competitiveness and ensuring smooth operations. These challenges include:

Productivity and diminishing ore grades: Mining productivity in Chile and Antofagasta has been in decline, with mining becoming the largest drag on productivity at the national level for the past 20 years (Chapter 3).

Availability of skills: In mining-specific skills, there is a significant deficit both in terms of employees and competencies needed. For the period 2021-30, a 25 000-employee gap is foreseen due to the compound effects of the retirement of current workers and the expected creation of new jobs resulting from the increased sophistication of mining operations and processes (Chapter 3).

Complex and centralised land management system: An excessively centralised public land administration and management system and widespread mining property speculation make land scarce and difficult to obtain, for example to put to useful purposes downstream activities in mining processes.

Environmental matters: Concerns and doubt about the long-term effect of mining on the local environment are persistent and few coherent and systematic strategies have been put in place to clarify such concerns. These concerns include doubts about the long-term effects of marine water capture and desalinisation, the region’s significant carbon footprint derived from a combination of intensive use of energy and reliance on fossil fuels for energy generation.

Social concerns: The equitable allocation of benefits from the industry (both regionally and at the local community level) is also likely to prove challenging going forward, especially in the face of aforementioned changes that digitalisation is already causing in mining’s traditional shared-value proposition.

A well-set strategy has the potential to prepare the region to make the most of these megatrends and mitigate negative impacts locally. The impact of these megatrends on mining municipalities in the Antofagasta will depend on the long-term policy strategy to address changes and prepare firms and communities for the future.

Ensuring a sustained improvement of people’s well-being

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Antofagasta is the largest copper producer and among the top lithium producers in the world. The sector has historically represented most of Antofagasta’s GDP (53% in 2018) and exports (90%). The region stands out as the country’s second-largest recipient of foreign direct investment, only surpassed by Santiago Metropolitan Region (Atienza et al., 2015[1]).

This sector has also pivoted the Chilean economy in the last decade. During 2010-20, the sector represented almost 10% of the country’s GDP, contributed up to 56% of the national exports and generated 9.3% of tax revenue (Ministerio de Minería, 2020[2]). The participation of mining in the national GDP has grown from 8.1% in 2016 to 14.6% in 2021, and the contribution in tax revenue has gone from 2% to 13% in this same period.

However, while this natural wealth has fuelled Chile’s development and positioned it as one of the most developed countries in Latin American, it has not fully translated into a relatively greater quality of life for Antofagasta. This region faces important development bottlenecks across different dimensions of well‑being, with greater stagnation in some areas relative to other Chilean regions that did not benefit from such historic wealth.

Economically, the region exhibits a relatively high unemployment rate (9.6% in 2022) compared to the OECD benchmark of mining regions (7%) and relatively high economic volatility (Chapter 2). Furthermore, there is low participation of local companies in the mining value chain (15% of companies in the region in the World Class Supplier Program), with few forward linkages of the mining process (e.g. most copper is exported without a refining process) (Chapter 3).

In the social dimension, mining communities lack accessibility to quality education, childcare and specialised health. Children’s and public green parks are an existing concern in the communities.

In the environmental dimension, the region is one of the most arid in the world, the mining sector has increased the demand for continental water and some extraction process also augment the risk of pollution of water reservoirs. There is also a lack of assessment of the biodiversity of the region (e.g. fauna and flora), coupled with visual pollution and relatively high levels of air pollution (Chapter 2).

Materialising previous and current initiatives that aimed to translate mining wealth into greater well-being

Different polices and initiatives in Chile and Antofagasta have tried to better translate mining wealth into greater well-being locally. At the national level, mainly, the Ministry of Mines and the Production Development Corporation (CORFO) have encouraged policies and strategies to promote development in Antofagasta, mainly targeting the economic dimension in the region.

At the regional level, the Mining Cluster of Antofagasta was likely the first clear, coherent plan to sustainably improve the role and interaction of the local economy with the mining process. Private companies and state-owned copper mining company Codelco have also undertaken initiatives to improve the effect of mining in the local communities. Table 4.3 summarises a number of main initiatives that have aimed at improving the mining impact in Antofagasta’s development.

Table 4.3. Selected initiatives that have aimed at improving the effect of mining in Antofagasta’s development

|

Policy or initiative |

National or regional initiative |

Origin |

Description |

Main area of focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alta Ley Corporation |

National |

Created in 2015 as part of CORFO’s Smart Specialization Strategic Program. |

An organisation designed to articulate the existing capacities in public and private entities and organisations in the mining industry, with the purpose of promoting and fostering the development of the sector to improve the competitiveness and sustainability of the mining sector. |

Economic |

|

Mining Cluster of Antofagasta |

Regional (public-private) |

2019 alliance between Antofagasta Minerals, CORFO and the Antofagasta Regional Productive Development Committee. |

Brings together mining companies, government agencies and educational institutions around two strategic objectives: training human capital in the region and developing innovative suppliers. |

Economic |

|

Mining Cluster Program |

National-regional (public-private) |

In 2002, CORFO spearheaded the programme. |

Develops a mining cluster to increase territorial competitiveness through business synergy and integration. |

Economic |

|

World Class Supplier Program |

Regional (private) |

In 2015, private initiative of BHP, followed by Codelco. |

Develops innovations in domestic suppliers to provide technological solutions to specific problems detected by large firms and to sell them at a larger scale in international markets. |

Economic |

|

Creo Antofagasta |

Regional (public-private) |

In 2013, BHP Escondida and the local government initiated the strategy of gathering 11 companies around the city of Antofagasta and 2 universities. |

Establishes programme focused on seven areas of action: use of land and growth, transportation and mobility, public space and green areas, environmental sustainability, participation and civic society, economic diversification and identity and culture. |

Comprehensive (economic, social and environmental) |

|

Calama Plus |

Regional (public-private) |

In 2012, Codelco (main funder) together with the local and the regional government, established this initiative with a directive council. Another nine companies joint. |

Establishes a sustainable urban development plan for Calama to raise the standard of quality of life. |

Comprehensive (economic, social and environmental) |

Source: Based on Navarro, L. (2018[3]), “The World Class Supplier Program for mining in Chile: Assessment and perspectives”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.10.008; Devenin, V. (2021[4]), “Collaborative community development in mining regions: The Calama Plus and Creo Antofagasta programs in Chile”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.10.009.

At the regional level, the idea of a mining cluster was likely the first clear, coherent plan to sustainably improve the role and interaction of the local economy with the mining process. In 2000-06, the regional government put in place its mining cluster strategy, acknowledging that the regional businesses showed marginal participation in mining companies' secondary activities and there was low interaction between large and medium/small mining companies. This strategy was initially created in the 1990s due to the impact of the large investments that began during that decade. In the 2000s, it was recognised as one of the axes of the regional strategy of development for 2000-06, reflecting the need to consolidate a “mining, industrial and services productive complex” to take advantage of all of the potential and synergy associated with mining, and to support the growth and development of all other sectors of the regional economy. This policy goal has helped strengthen the linkages of regional businesses as providers of mining companies.

Yet, the mining cluster initiative in its different forms has not fulfilled the expectations, as few local businesses or the mining equipment, technology and services have grown internationally with a local market that is still fragmented and limited vertical knowledge transfer (Devenin, 2021[4]; Atienza et al., 2015[1]). This policy alone is not enough to address the increasing outsourcing trend of mining activity, which, together with changes in information and transportation technologies, has given rise to a process of relocation of production chains outside the regions of origin of the activity, both nationally and internationally (Atienza et al., 2015[1]).

Social and environmental aspects have been overseen in the different polices aiming at translating the mining wealth into the community. In particular, a reduced of attention to the social needs of mining communities (green areas, children’s parks, education linked to industrial needs or quality healthcare) has led to a enabling environment that struggles to retain and attract skilled workers and companies.

While different private companies and Codelco have individually issued programmes to improve liveability in local communities, those actions are dispersed, lacking co‑ordination among each other and scalability to create long-term solutions for the region. For example, the World Class Supplier Program successfully achieved its goals of creating technological solutions for large firms and developing supplier capacities. However, the scaling-up and internationalisation effects of the programme seemed small, given the low incentive from mining companies to collaborate in the scaling-up and internationalisation of providers (Navarro, 2018[3]).

An initiative worth mentioning and from which lessons can be learnt is Calama Plus. The Calama Plus Consortium resulted from a joint effort between Calama’s public and private sectors, with the aim of building a comprehensive vision to improve quality of life in the city (Box 4.1). Despite the thoughtful structure and process, the initiative did not manage to meet expectations and fell short in implementing most of the projects. This led Codelco and many other companies to withdraw as project funders. Part of the difficulty was to maintain trust throughout the project’s structuring and implementation as well as balancing project prioritisation and problem solving. Also, the lack of capacity of the municipal government to structure and implement projects undermined trust in the outcomes of the initiative. In Chile, many projects require approval from national agencies – e.g. acquiring land needs the approval of the Ministry of National Goods – and the municipal government struggled to meet the requirements of the project proposal or present a proposal on time.

Box 4.1. Lessons from the Calama Plus initiative

In 2012, Codelco, together with the local government, established the Calama Plus Consortium to set up a sustainable urban development plan to improve the city’s attractiveness and raise the standard of quality of life for its inhabitants. Codelco was the initial financer of the initiative, which gathered a total of ten private companies operating around the town, including the largest mining companies in Calama (e.g. Antofagasta Minerals, Freeport MacMoran, Glencore), mining suppliers (e.g. Komatsu) and retail companies (e.g. Sodimac Calama).

The initiative included a governance body made up of different local actors (mining companies, regional governments and municipalities) compiling a list of local priorities in various workshops and meetings with the participation of about 24 000 inhabitants. These meetings helped to identify main priorities and agree on a number of projects capable of improving the urban development of the city and, thus, quality of life.

However, from 2012 to 2019, few of the priority projects were implemented, which led to the community’s discontent and some companies’ decision to withdraw. By 2019, main funder Codelco also decided to leave the initiative and reallocate resources to other initiatives (e.g. mining cluster). Many factors were behind the difficulty in meeting expectations and outputs, including:

A governance body which lacked the capacity to reach a consensus and change the course of action and an unequal representation of members where the funding provider had greater decision-making weight.

Lack of capacity to come up with agreements and compromises across different levels of government (national and municipal) to speed up implementation of key projects.

Lack of capacity (human and technical) in the municipal government to structure, present and implement projects.

Source: Devenin, V. (2021[4]), “Collaborative community development in mining regions: The Calama Plus and Creo Antofagasta programs in Chile”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.10.009; CALAMATV (2020[5]), Pasado y futuro de Calama Plus, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4VycLVIvOI.

Different aspects might explain the challenges in producing structural well-being improvements in Antofagasta. They include a lack of long-term planning to support diversified economic activities, a historical market-oriented economic policy framework and a lack of co‑ordination between local and national governments to prioritise relevant projects for the social and environmental well-being of local communities.

Links with Chile’s National Mining Policy 2050

Most recently, in 2022, the Chilean Ministry of Mines, on behalf of the national government, issued the National Mining Policy 2050 (Ministerio de Minería, 2020[2]). This policy acknowledges that “the absence of a long-term national mining policy, with answers to the growing and complex transformations on a national and global scale, undermines the possibilities of sustainable development of the mining sector and of the country as a whole”. This policy has national objectives at the economic, social, environmental and institutional levels with a main national vision of the effect. It serves as a navigation chart for industry and the state, which was elaborated with a wider participation of citizens across the different regions of Chile (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Chile’s National Mining Policy 2050

The Ministry of Mining decided to develop a National Mining Policy 2050 in order to have effective governance, strengthen institutions, open opportunities for dialogue and collaboration, encourage competitiveness and promote innovation, safe and inclusive development and a state-of-the-art environmental management system.

The process of the policy involved the participation of more than 3 500 stakeholders in all elaboration phases, with 128 open roundtables that set up 128 initiatives throughout the country covering the challenges posed in the 9 transversal axes of the policy. This elaboration process included a territorial focus with 1 500 participants and 18 regional workshops.

The vision of this policy is to: “Maintain and strengthen our leadership by supplying the minerals the world needs by 2050 in the fight against global warming, addressing the consequences of climate change and generating value for the country” (Ministerio de Minería, 2020[2]).

The policy recognises different challenges related to the economic, social and environmental spheres, which are the basis for the main objectives.

Table 4.4. Objectives of the National Mining Policy 2050

|

Area |

Strategic objectives |

Particular goals (selected) |

|---|---|---|

|

Economy |

Become a world leader in the sustainable production of minerals, promoting a low-carbon economy and protecting the health of people and the environment. |

|

|

Generate a chain industry at the forefront of innovation and development. |

||

|

Increase the sustainable productivity and competitiveness of the mining industry. |

||

|

Social |

Have quality, inclusive jobs with high safety standards. |

|

|

Develop projects collaboratively with communities and Indigenous peoples. |

||

|

Generate value by reducing multi-dimensional poverty and safeguarding heritage in the territories where it is inserted. |

||

|

Environment |

Lead the circular economy model by reusing waste and efficiently using resources. |

|

|

Lead adaptation and mitigation to climate change, achieving carbon neutrality in the sector by 2040. |

||

|

Minimise environmental effects by harmonising the development of mining activity with the environment. |

||

|

Institutionally |

Have a modern, transparent institutional framework with efficient management, ensuring the industry benefits the country. |

|

|

Have a legal framework for the mining sector for sustainable development in the long term. |

||

|

Promote the social acceptability of mining. |

||

|

Strengthen the framework of the sustainability of small and medium-sized mining. |

||

|

Strengthen Codelco and Enami as state companies and international benchmarks. |

Source: Ministerio de Minería (2020[6]), Política Nacional Minera 2050 [National Mining Policy 2050], https://doi.org/www.doe.cl/alerta/28012023/2262175.

While this national policy set a good basis for the integration of mining and regional development, it fell short in adopting a place-based approach and conveying roles for regional and local governments in co‑ordinating and implementing projects of strategic interest for mining communities. The national mining strategy did promote main regional priorities across the country but did not establish action lines or objectives per region despite regions having different assets and challenges. Furthermore, while the National Mining Policy 2050 sets a good roadmap to improve the mining sector as a whole and its impact on Chilean society, it does not set clear strategies to unlock specific regional assets or address particular challenges in the different regions.

Supporting upcoming investments in the mining and energy sector and ensuring their linkages with the local economy

As of January 2023, Antofagasta is the second region in Chile with the highest investment projection for the next 5 years (24% of the total national investment in projects) (Oficina de Grandes Proyectos, 2023[7]). These investments are mainly driven by the mining sector (51% of the total), followed closely by those in the energy sector (44%). In total, the investments are estimated to create about 29 563 jobs during the construction process (7% of the employed population) and 15 000 during the operation process. The nature of the investment from mining is mostly brownfield (replacement or expansion of current operations or change of the production process) (Comision Chilena de Cobre, 2022[8]), while renewable energy investments tend to be linked to new operations. According to the Chilean Copper Commission (Comision Chilena de Cobre, 2022[8]), most mining-related investments in Antofagasta (until 2031) are related to copper mining (93%).

These productive investments add up to corporate social responsibility (CSP) projects in Antofagasta. They include drinking water and sewerage programmes (Antofagasta Minerals and Codelco), programmes to improve urban and recreational infrastructure (Antofagasta Minerals, BHP and Codelco), to improve digital skills of students and the working force and provide tertiary education opportunities (Antofagasta Minerals, BHP, Codelco, Glencore Sierra Gorda) or initiatives to support economic diversification (Albemarle and SQM).

All of these initiatives and investments would benefit from greater co‑ordination with each other and with public investments as well as visibility in the community. A government mining strategy should also help to maintain and scale up CSP projects, which are usually focused only on the communities surrounding the mines and prioritise initial investment rather than ongoing operations.

Capitalising on the ongoing decentralisation process in Chile

As well as the need for a coherent long-term vision for Antofagasta, a long-term strategy created at the regional level can benefit from the ongoing decentralisation process in Chile by relying on the new elected figure of regional governor, alongside regional government’s greater strategy implementation tools and accountability.

Chile has undertaken decentralisation efforts that provide regional government with greater responsability. Since 2021, regional governors in Chile can be elected by popular vote, based on Laws No. 20.990/2017 and No. 21.073/2018 that transformed the “mixed” regional system (both deconcentrated and decentralised) – in place since 1992 – into a full self-government system, with direct election of the regional executive (governors) by popular vote every four years (Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, 2021[9]). The regional government is constituted by a governor (the executive body of the region) and a regional council (the legislative body) that has the deliberative power. The members of the council have been directly elected every four years since 2014 (OECD/UCLG, 2022[10]).

Under this evolving framework, the governor has acquired new responsibilities, including developing investment strategies and land use planning (Box 4.3). This represents an important shift from the previous multilevel governance structure, where each region was governed by an intendent, a delegate appointed by the President of the Republic to administrate the resources and design the policies for the region.

These changes open up new opportunities for regional governors to design and define their regions’ development strategies and target strategic investment programmes. Furthermore, it creates a figure elected by public vote accountable for addressing the regional priorities of the population and implementing the strategic plans for development.

Box 4.3. New responsibilities of regional governments in Chile in an ongoing decentralisation

Since the late 2000s, the Chilean government has pursued important decentralisation and regionalisation reforms. Laws No. 20.990/2017 and No. 21.073/2018 allow governors to be elected by popular vote. The first 16 elected regional governors took office in July 2021 for a period of 4 years and with the possibility of re-election. In parallel, Law No. 21.074/2018 transferred from the national government to the new self-governing regions responsibilities on land use planning, economic and social development and culture.

The Inter-ministerial Committee of Decentralisation supports and advises the President of the Republic on the competencies to be transferred, which can result from presidential initiative or upon request from the regional government. The newly elected governor is accompanied by a presidential delegate who is appointed by the President of the Republic for each region and is in charge of the exercise of matters concerning internal government, public security, emergencies and co‑ordination, supervision and control of public services operating in each region.

The regional governor has, among others, the following duties:

Formulates development policies for the region, considering the respective community policies and plans.

Submits to the regional council the policies, strategies and projects of regional development plans and their modifications.

Submits to the regional council the proposed budget of the respective regional government.

Represents the regional government judicially and extrajudicially,

Appoints and removes the public officials in the regional government that the law determines.

Ensures compliance with the rules on administrative probity.

Promulgates, with the prior agreement of the regional council, the regional land use plan, the metropolitan, intercommunal, communal and sectional regulatory plans and the detailed plans of intercommunal regulatory plans.

Chairs the regional council.

Law No. 21.074/2018 also created a mechanism through which regions can ask for further competencies to be transferred to them, which is under discussion.

Source: OECD/UCLG (2022[10]), 2022 Country Profiles of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment, https://www.sng-wofi.org/country-profiles/; Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile (2021[9]), Elección democrática de gobernadores regionals, https://www.bcn.cl/portal/leyfacil/recurso/eleccion-democratica-de-gobernadores-regionales.

However, the match of responsibilities and resources for regional governments is still unclear. By 2020, grants and subsidies represented a significant (56.1%) and growing share of subnational revenues, slightly above the OECD average when only considering local governments (53.3%), reflecting the high level of dependency of municipalities with regard to the central government (OECD/UCLG, 2022[10]). The national government has a strategic role in implementing regional development plans.

The Ministerial Regional Secretaries (SEREMIs) – deconcentrated entities representing each ministry at the regional level – have responsibilities in environmental, land use or education policies, among others. Furthermore, auditing bodies like the Superintendence of the Environment are of particular importance to ensure mining activities do not affect the environment. In fact, meetings with regional stakeholders often referred to the low capacity of the Superintendence of the Environment (SMA) as one of the main bottlenecks to ensuring efficient environmental protection from mining and other activities in the region. For example, the SMA’s staff is relatively small compared to the number of mining operations and companies to monitor.

Furthermore, there is an imperative to streamline the approval process for local public projects by the SEREMIs in order to expedite actions that address the needs of local communities. For instance, the execution of local projects related to community or economic infrastructure in mining municipalities of Antofagasta, such as expanding health centres or creating parks, green spaces or industrial areas, need approval from the SEREMI of National Goods to access public land. This process is often characterised by bureaucracy and lacks flexibility, further complicating matters for local governments with limited institutional capacity and constrained by the four-year political cycle.

Likewise, local governments also find it difficult to propose projects that need to be accepted by the SEREMI of National Goods, e.g. developing or expanding health centres, a park, a green or an industrial area. This process is often characterised by bureaucracy and lacks flexibility, further complicating matters for local governments with limited institutional capacity and constrained by the four-year political cycle. Therefore, the national government should strengthen the SEREMI of National Goods to allow it to prioritise strategic projects for the well-being of mining communities in Antofagasta that have to deal with a high proportion of public lands and the large number of mining properties owned in the region. This could include improving the technical and human capacity of national institutions, with a particular focus on easing the public land administration and management system.

The definition of responsibilities and financial autonomy for regions is still under discussion in Chile and discussions on a mechanism through which regions can ask for further competencies and resources to be transferred to them are still ongoing. In fact, during the development of this study, the national government announced the entry of a draft law, known as Stronger Regions, for approval by congress, a bill whose objective is to provide greater regional autonomy and financial flexibility and establish better inter-territorial compensation mechanisms and safeguard sustainability and fiscal responsibility. This draft law goes in the right direction as it aims to guarantee better correspondence between the responsibilities and attributions that the law gives to the regional governments and the resources they have for their exercise.

It is worth noting that these discussions of devolving regional powers have occurred in the midst of political unrest that led in 2020 to a plebiscite in which Chileans voted in favour of a new constitution. While the final drafting proposal for the new constitution, presented on 5 July 2022, was rejected, discussions are ongoing to reach agreement on a new constitution.

Therefore, a regional mining strategy for Antofagasta can be that roadmap to strengthen Antofagasta’s mining sector and ensure that the mineral wealth provides a long-lasting increase in regional well-being. It will leverage a number of opportunities:

Improving well-being of communities and Indigenous peoples in the region of Antofagasta by helping address the main development priorities for the region.

Ensuring mining sector competitiveness and co‑ordinating its investments to ensure its role as an economic engine for the region/

Unifying regional actors around a single vision of the role of mining in regional development.

Making the most of the ongoing decentralisation process in Chile to improve the regional government capacity and raise the strategic capacity of SEREMIs for the region.

Improving co‑ordination with Chile’s national mining strategy to attain efficiencies in investment and programmes, and with other regional development policies, to unlock cross-sectoral synergies in the economy.

The Mining Strategy of Well-being for the Region of Antofagasta

Based on the potential benefits of an Antofagasta regional mining strategy, the next sub-sections describe the main components of this regional strategy, drawing from some best practice examples of national and regional mining strategies across the OECD.

Building the mining strategy for the well-being of Antofagasta

The experience across several OECD countries and regions has shown that strategic planning for extractive sectors is an important tool for economic growth, environmental protection and regional social improvements (reducing inequality and access to opportunities). A mining strategy connects the different actors across the mining value chain and promotes external networks by clarifying the role of mining for regional and national development. In a context where mining faces concerns from some parts of society, a well-designed strategy can help raise awareness among local communities of the opportunities and challenges involved in mining development and outline ways to better share the mining benefits.

A participatory process to legitimise and ensure alignment with local needs

Since October 2022, conducted as part of this study, the construction process of this regional strategy has involved more than 80 in-person meetings and focus groups, either with OECD representatives and peer reviewers of other member countries or organised directly by the regional government and the Catholic University of the North. Some of these meetings combined private and public sector representatives along with academia and civil society in an open discussion about the future of the region and the role of mining. Other meetings gathered specific groups of society to dive deeper into the main priorities and challenges for development. The regional government hast complemented these meetings by identifying ESG initiatives implemented by the different mining companies across the region and priorities informed by the different communities. This process is in line with other mining strategy construction processes in OECD countries (Box 4.4)

Box 4.4. Engagement strategy in the Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan

The Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan includes a vision, principles and strategic directions that governments, industry and stakeholders can pursue to drive industry competitiveness and long-term success. This generational initiative aims to raise Canadians’ awareness of the importance of the minerals and metals sector, respond to ongoing and emerging challenges and help position Canada for opportunities offered by an evolving economy.

This plan was informed by engaging with Indigenous peoples, innovation experts, private companies, industry associations, non-governmental organisations, young people, other stakeholders and partners, as well as Canadians from across the country.

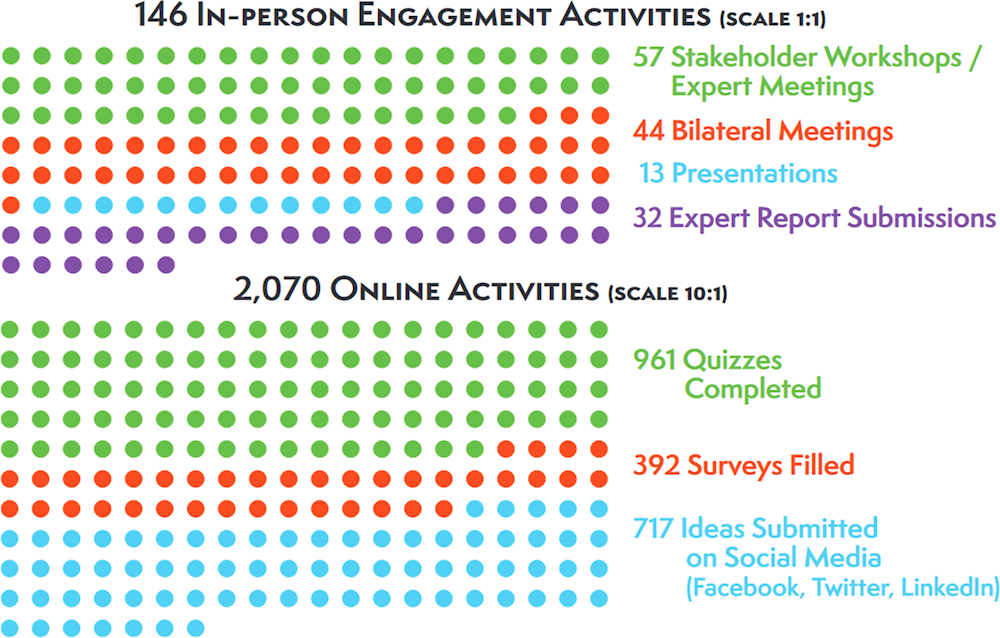

The government consulted with civil society to gather main concerns, ideas and suggestions to inform the plan. This engagement process included in-person activities with workshops, bilateral meetings and expert report submissions. It also adopted online activities through quizzes, surveys and ideas submitted through social media (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Analytics of the engagement strategy in the Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan

Source: Government of Canada (2019[11]), The Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/CMMP/CMMP_The_Plan-EN.pdf.

This strategy, its objectives and its implementation respect the the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169 adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) (ILO, 1989[12]) and approved by the Chilean congress on 15 September 2009 as part of Chilean legislation. In virtue of this agreement, the implementation of the actions emerging from this strategy needs to consider the active participation of Indigenous peoples by guaranteeing respect for its integrity.

This process can be continued, especially during the phases of monitoring and rebalancing of priorities. Priorities today may not be the same as those in the future and a continuous participation channel to identify priorities is needed to account for changes in local conditions. Building on the efforts already made, the continuous engagement process can go further and involve expert reports in thematic areas and differentiated strategies to reach various types of populations, like social media for youth or radio and mail surveys for the older population.

A long-term vision that moves from past and current concerns towards a path for the future

Setting a clear and ambitious goal in the strategy is useful to align efforts across different levels of government and other regional stakeholders to meet common goals, attract skilled workers and new investors and create partnerships with international actors that support the long-term plan of the region (OECD, 2020[13]). A region with clarity in its long-term goals and certainty in the actions needed to get there becomes attractive for investment and public support.

In Antofagasta, as in other mining regions, discussing the effects of mining on local well-being often times leads to extreme positions across the regional stakeholders. The mining sector benefits and uses the territory’s endemic natural resources, which disturb natural ecosystems, require natural resources like water and land and create visual, noise and air pollution. In Antofagasta, many mining operations occur in lands of Indigenous populations whose beliefs and ways of life can be disturbed by the mining activity. Moreover, in Antofagasta, there is a lack of information on the past and current impacts of mining on the environment and human health.

The strategy’s preparation and final output have been a catalyst to contrast the different views of development in the region, conveying main concerns from different parts of the population and reaching common priorities for future development. On the one hand, interviews with regional stakeholders underlined the need to recognise that mining governance in Antofagasta has not addressed the welfare needs of the communities where mining occurs. On the other, mining companies and businesses linked to them require institutional certainty for long-term investments in a sector that is increasingly competitive worldwide.

Despite these apparently different needs, meetings and survey responses from different regional stakeholders indicated that mining is perceived to be one of the engines of the region’s future development (Box 4.5). This common understating provides a good basis to build from, as in mining regions – where one single sector represents most of the economic growth – development strategies that are designed at the margin of this sector risk missing the core actors and dynamics for regional development. Therefore, the strategy’s vision needs to leverage regional mining assets, to attain greater objectives, such an improved well-being, that meet the expectations of other stakeholders and sectors in the region.

Box 4.5. A recent survey on the perception of mining in the development of Antofagasta

According to a survey of 700 inhabitants of Antofagasta conducted by the Catholic University of the North in April 2023, most people agreed with the development of the mining sector in the region (56%), while a lower share (13%) disagreed totally or partially with the activity. Disagreement against the sector has also decreased (19%) since 2021, with the undecided share increasing since then (from 15% to 30%).

However, the share of people agreeing with the mining activity in the region has decreased since 2021 (from 65% to 56%). Furthermore, when survey participants are asked to reply about how much mining contributes to the development of the region, the share of individuals considering that the sector contributes little or nothing has increased from 31% in 2021 to 46% in 2023.

When the survey asked interviewees which of the axes proposed by the regional government in the Mining Strategy they consider most important, most people ranked well-being and quality of life (36%) as the highest, followed by development in harmony with the environment.

Source: Catholic University of the North (2023[14]), Results Report Regional Barometer Survey of Antofagasta 2023, Institute of Public Policy, Catholic University of the North, Antofagasta.

This strategy needs to fulfil the expectations of the different parts of society to regain trust and establish a social agreement that manages to move towards a common goal. This common goal should be built on the recognition of the different priorities:

Recognising that mining communities in Antofagasta have been left behind in some well-being dimensions and that more needs to be done to ensure local development opportunities.

Recognising the strategic role of the mining sector in the development of Antofagasta.

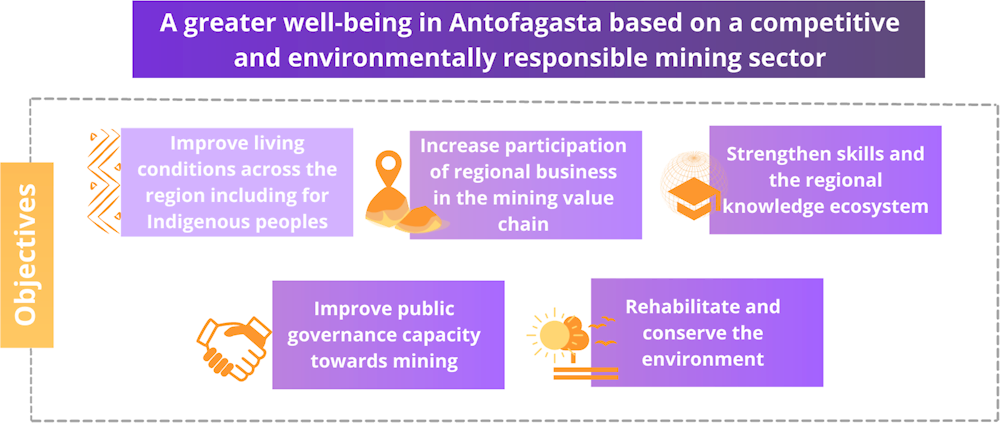

Based on this recognition, the long-term vision of the strategy should be one that sets a long-term and aspirational goal for the region: a greater economic and social well-being for mining communities with an internationally competitive mining sector that protects the environment. A well-managed vision becomes a slogan that helps different actors to work in the same direction. As a marketing slogan, the vision needs to be communicated and widely shared, and could translate as follows: “A greater well-being in Antofagasta built on a competitive and environmentally responsible mining sector”.

Mining Stragegy objectives helping to address Antofagasta’s development priorities

The objectives of the Mining Strategy need to address the main regional priorities that help ensure greater quality of life with a more environmentally sustainable and competitive mining sector (Chapters 2 and 3). These main priorities were already identified in the previous chapters of this report and align with those main concerns raised across the multiple meetings and information gatherings with regional stakeholders. Table 4.5 outlines these priorities and their relationship with long-term objectives to attain the vision of the strategy.

Table 4.5. Summary of main development priorities identified for Antofagasta

|

Area |

Priorities |

|---|---|

|

Institutional dimension |

Attain an efficient regulatory and institutional framework with the capacity and agility to process environmental permits, authorisation to access land for industrial purposes or monitor compliance with environmental regulations. |

|

Economic well-being |

Increase participation of local businesses in background and forward linkages of the mining value chain. |

|

Increase involvement of the local working force in high-value-added activities in the mining sector. This is especially relevant to adapting skills for the future demands of the industry in the face of an increasing trend of digitalisation of mining operations. |

|

|

Social and community well-being |

Improve access to quality education, health services or environmental amenities (green areas and parks) and drinking water. |

|

Environmental well-being |

Conduct an assessment of the mining effect on water systems and the biodiversity in the region and monitor the management of mine tailings and waste. |

According to the discussions with the different regional actors throughout the engagement activities and the priorities identified, the regional government should include at least five comprehensive, challenging but trackable objectives in its 2023-2050 strategy. In this strategy, well-being is a horizontal outcome that would emerge by attaining some of the different objectives and sub-objectives. Well-being, the ultimate goal of this strategy, is a multidimensional outcome compounded by the addition of greater economic, social and environmental factors.

This structure of objectives follows the SMART (specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic and time‑bound) model to define the length and formulation of objectives. While these objectives represent a clearer and longer-term goal, framed with basic statements, they also place the region on a challenging and concrete path relative to the strategies of other mining jurisdictions (Box 4.7).

Figure 4.2. Objectives of the Mining Strategy

Source: OECD based on meetings with regional stakeholders.

Box 4.6. Governance SMART model to define general objectives in a strategy

Objectives serve as the basis for creating the policy framework and are fundamental to monitoring and evaluating performance.

The suitability of objectives should be tested against the so-called SMART model. Objectives should be:

Specific: an objective must be concrete, describing the result to be achieved, and focused, contributing to the solution of the problem.

Measurable: an objective should be expressed numerically and quantitatively in relation to a specific benchmark and should allow the progress of implementation to be tracked.

Action-oriented/attainable/achievable: an objective should motivate action and should state what is to be improved, increased, strengthened, etc., but should also be reachable.

Realistic: an objective should be realistic in terms of time and available resources.

Time-bound: the realisation of the objective should be specified in terms of a time period.

The set of objectives should tell the “story” of the strategy in a logical and sequential way, so they should be logically connected. They should be connected to all of the defined and selected problems that require reform and – where multiple layers of objectives are used – should be linked to each other in order to provide a complete picture of the reforms envisaged.

Source: Vági, P. and E. Rimkute (2018[15]), “Toolkit for the preparation, implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of public administration reform and sector strategies: Guidance for SIGMA partners”, https://doi.org/10.1787/37e212e6-en.

Box 4.7. Different objectives of national and regional mining strategies across the OECD

Most mining strategies across OECD jurisdictions have a limited number of objectives, less than six, covering most of the challenges of mining regions and addressing transformation brought by megatrends, including climate change and digitalisation.

Table 4.6. Strategic objectives from selected regional mining strategies across the OECD

|

Strategy |

Objectives |

|---|---|

|

Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy |

1. Supporting economic growth, competitiveness and job creation. 2. Promoting climate action and environmental protection. 3. Advancing reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. 4. Fostering diverse and inclusive workforces and communities. 5. Enhancing global security and partnerships with allies. |

|

Ontario, Canada: Critical Mineral Strategy |

1. Enhancing geoscience information and supporting critical minerals exploration. 2. Growing domestic processing and creating resilient local supply chains. 3. Improving Ontario’s regulatory framework. 4. Investing in innovation, research and development. 5. Building economic development opportunities with Indigenous partners. 6. Growing labour supply and developing a skilled labour force. |

|

Western Australia’s Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Strategy 2021 |

1. A leading global destination for exploration investment. 2. An environmentally and socially responsible industry. 3. An industry that is efficiently and effectively regulated. 4. An evolving industry. 5. An innovative industry. 6. Maximising benefits for all Western Australians. |

Source: Geological Survey of Finland (2010[16]), Finland’s Mineral Strategy, http://projects.gtk.fi/export/sites/projects/mineraalistrategia/documents/FinlandsMineralsStrategy_2.pdf.

The objectives in this strategy require specific goals to measure their success, framed as impact indicators. The specific level to be attained by these indicators in 2030 and 2050 needs to be agreed upon with the main stakeholders in the region. Agreeing on these indicators will be the process of forming regional agreements for the future development of the region. Table 4.7 depicts a suggestion of indicators in a way that is legible and easy to monitor for everyone.

Table 4.7. Impact indicators of strategic objectives

|

Objective |

Impact indicator (examples) |

|---|---|

|

Improve the well-being of local communities and Indigenous peoples |

Increased life expectancy in the region |

|

A greater share of health centres with specialise attention |

|

|

Greater share of parks and recreation facilities |

|

|

Increase the participation of regional businesses in the mining value chain |

Greater share of local companies that are providers of mining operations |

|

Greater share of companies in the circular mining economy |

|

|

Strengthen skills and the regional knowledge ecosystem |

Greater share of the workforce with technical or tertiary education |

|

Increased investment in innovation (R&D and social) around the green transition in mining |

|

|

Improve governance for a more productive mining sector |

Lower time to process and issue decisions of environmental permits and monitoring |

|

Lower time to process and issue decisions on land permits |

|

|

Rehabilitate the environment |

Lower GHG emissions in the region |

|

Reduced use of continental water for mining operations |

|

|

More specific measures to mitigate the impact of mining on the environment |

This vision and these objectives can also help establish common agreements with regional stakeholders to achieve a shared development target. The government of Antofagasta has reached several common agreements with the private sector and communities to establish concrete commitments from all segments of society to fulfil the goals and vision outlined in this regional strategy. Annex 4.A outlines the commitments that different segments of society have envisaged to agree upon to support the strategy.

Materialising long-term objectives through strategic projects

Attaining the objectives requires specific actions that build trust in the strategy in the short term and ensure a long-term continuous implementation. To this end, a timeframe of strategic projects should be put in place by indicating the projects that are a priority and feasible to implement in the next few years (e.g. 2024‑27) and those inscribed on a longer timeline (2030-50).

Selected projects are set to meet the most pressing priorities in the region. These projects have been identified from three types of sources: i) more than 80 meetings with regional stakeholders for the preparation of this strategy, conducted by the regional government and the OECD; ii) direct information provided to the regional government since October 2022 by key stakeholders; iii) assessment conducted by this OECD study (Chapter 2) and the regional priorities already identified by two flagship regional strategies: the regional development plan and the innovation strategy (see next section). Table 4.8 presents a suggested timeframe of strategic projects to attain the five objectives of the strategy.

Table 4.8. Timeframe of strategic project per the objective of the Mining Strategy

|

Timeframe/ objectives |

Improve the well-being of local communities and Indigenous peoples |

Increase the participation of regional businesses in the mining value chain |

Strengthen skills and the regional knowledge ecosystem |

Improve governance for a more productive mining sector |

Rehabilitate the environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short term (2023-27) |

Improve drinking water and sewerage systems in mining communities |

Measure the participation of regional companies in the mining value chain and establish a roadmap of opportunities |

Support the Lithium Institute to set a roadmap of innovative projects in lithium (e.g. water management) |

Improve the capacity of environmental institutions in the region (e.g. Superintendence of the Environment) |

Support civic environmental monitoring |

|

Facilitate the upgrade or installation of quality health centres |

Expand the participation of local businesses in mining companies’ programmes to upscale providers |

Promote apprenticeships in mining across regional schools |

Facilitate approval of industrial land (in collaboration with SEREMI of NAtional Goods) |

Reduce air pollution from mining operations |

|

|

Expand the number of recreational and green infrastructure and public lighting |

Promote synergies among mining companies’ programmes on local procurement |

Complement workforce training programmes of mining companies to make the most of the automation of operations |

Improve collaboration between large and medium/small mining companies |

Reduce mining waste generation and facilitate its valorisation |

|

|

Medium-long term (2030-50) |

Fund/structure to support the creation of Indigenous businesses |

Support technology transfer to regional companies |

Adapt basic education to prepare students for the mining automation process |

Enhance the capacity of local governments to structure, submit and approve projects |

Reduce to a minimum the use of inland water for mining activities |

|

Fund/structure to promote economic diversification (e.g. agriculture in the dessert, artisanal fishing) |

Internationalise the regional mining providers |

Support a network of research centres for the mining of the future |

Ensure that processes for metal recovery or extraction (e.g. oxide leaching) are achieved on time and with high environmental standards |

Evaluate the mechanisms to return water rights to the communities |

|

|

Improve tertiary roads and broadband infrastructure |

Support local entrepreneurs/small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to work circular economy activities in mining (recycling of lithium) |

Support professional development |

Promote greater use of renewable energies in mining operations (e.g. speeding up permits for interconnection and generation) |

Produce an environmental diagnosis of the region |

The short-term projects already identified for the strategy are part of the pipeline of projects to be developed in the regional plans or linked to the mining companies’ CSR plans. These short-term projects can help create local alliances to work towards a unified vision and rebuild trust at the regional level by demonstrating that change.

The long-term projects are not described in detail in this document but aim to outline the main priorities identified in the region. For example, the creation of a fund to support Indigenous businesses emerged from the need of entrepreneurs and SMEs in mining communities to make business plans marketing strategies, use technological solutions and access financing. This project can get inspiration from the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (n.d.[17]).

Table 4.9. Short-term projects of the Mining Strategy

|

Objectives of the strategy |

Short-term strategic project 2027 |

Objectives and description |

|---|---|---|

|

Improve the well-being of local communities and Indigenous peoples |

Improve drinking water and sewerage systems in mining communities |

Leverage existing programmes of mining companies (e.g. AMSA or BHP) to ensure mining companies improve the network of drinking water (and add public points) and the sewerage infrastructure. |

|

Facilitate the upgrade or installation of quality health centres |

Partner with mining companies to establish health centres, particularly outside the city of Antofagasta. Some needs include centres of preventive community care and cancer diagnostics. |

|

|

Upgrade current centres with missing specialities e.g. mammography. |

||

|

Expand the number of recreational, green and cultural infrastructure |

Collaborate with mining companies to expand recreational, green and cultural in mining communities, with government support to ensure their operation in the long run. |

|

|

Increase the participation of regional businesses in the mining value chain |

Measure the participation of regional companies in the mining value chain and establish a roadmap of opportunities |

Clearly measure the share of companies registered in Antofagasta that are direct providers of mining companies. |

|

Identify future needs of mining companies to procure locally. |

||

|

Expand the participation of local businesses in mining companies’ programmes to upscale providers |

Improve the innovative capacity of regional companies. |

|

|

Promote synergies among mining companies’ programmes on local procurement |

Map and make visible ongoing programmes and their results. |

|

|

Help solve challenges to involve more local businesses. |

||

|

Strengthen skills and the regional knowledge ecosystem |

Promote apprenticeships in mining across regional schools |

Improve the skills of basic education students to get involved in mining processes with high-added value. |

|

Support the Lithium Institute to set a roadmap of innovative projects in lithium (e.g. water management) |

Ensuring that the decision-making board includes various stakeholders. |

|

|

Support the definition of research lines with concrete objectives (e.g. improvement of water use processes). |

||

|

Complementing workforce training programmes of mining companies to make the most of the automation of operations |

Map and provide visibility to the mining companies’ workforce training programmes. |

|

|

Promote involvement of universities, embedding part of the programmes in educational supply. |

||

|

Improve governance for a more productive mining sector |

Improve the capacity of institutions in charge of environmental monitoring and environmental permitting in the region (e.g. SEREMIs, The Superintendence of the Environment) |

Establish a joint agreement with the national government to improve the staff and technical capacity of the SEREMI of the Environment. |

|

Improve collaboration between large and small/medium mining companies |

Improve business opportunities for small/medium mining companies with the collaboration of large mining companies. |

|

|

Facilitate approval of industrial land (in collaboration with SEREMI of National Goods) |

Establish an agreement of understanding with the SEREMI of National Goods to speed up priorities of land approval. |

|

|

Rehabilitate the environment |

Encourage civic environmental monitoring |

Provide communities with equipment and capacities to carry out independent environmental monitoring (learning from experiences of Albermarle and SQM). |

|

Support the transfer of monitoring stations from mining companies to the Ministry of the Environment and partner with the ministry to involve citizens and create clear information. |

||

|

Reduce mining waste generation and facilitate its valorisation |

Support monitoring and quantification of mining waste generation. |

|

|

Facilitate alliances with national or international companies to valorise waste mining and create new business opportunities. |

||

|

Reduce air pollution from mining operations |

Incentivise and support companies’ initiatives to reduce air pollution from mining operations, e.g. improving belt covering road wetting. |

|

|

Share good practices among companies. |

Many of the strategic projects consist of creating better alliances with mining companies or universities to give continuity and scale to the projects already in the pipeline. An important action is related to giving visibility in a unified way to all of the projects that mining companies are carrying out. Mining companies initiate and continue workforce training, sewerage improvement or street lighting programmes. However, given their atomisation, the population is not aware of these private initiatives, their impact and their investment. The Mining Strategy website must fulfil this task of diffusion.

Links with other regional development strategies

This Mining Strategy cannot replace the regional development plan but it can contribute to attaining long‑term regional development objectives and create synergies with other sectoral plans. The weight of the mining activity in Antofagasta makes it a sector with links across various areas of development and, if well-managed, a potential engine for other economic sectors in the region, such as tourism, agriculture or manufacturing. This Mining Strategy comes at the end of the first development plan (2021-24) built by a democratically elected government. Thus, it can leverage the development objectives of that plan and maintain the efforts in implementing some of the unfinished projects.