This chapter provides a brief overview of the OECD’s general approach to assessing civic space. It reviews how the methodology was adapted for the Portuguese context to focus on utilising civic space for public service reforms with an emphasis on empowering citizens and unleashing the power of digital government. It also discusses the methods and tools used for the Review.

Civic Space Review of Portugal

2. Leveraging civic space to advance public service reforms in Portugal

Abstract

2.1. An introduction to the OECD’s approach to assessing civic space

Under the purview of the OECD’s Public Governance Committee and the Working Party on Open Government, the OECD has been supporting countries around the world to strengthen their culture of open government by providing policy advice and recommendations on how to integrate its core principles of transparency, accountability and stakeholder participation into public sector reform efforts. The OECD’s work on civic space is a continuation of this effort, recognising that civic space is an enabler of open government reforms, collaboration with non-governmental actors and effective citizen participation. As a key contributor to an open government ecosystem, civic space is thus fully integrated into the OECD’s open government work in support of the OECD Recommendation on Open Government (OECD, 2017[1]).

The OECD Observatory of Civic Space was established in November 2019 to support member and partner countries to protect and promote civic space. Its work is guided by an Advisory Group comprised of experts, funders and world-renowned leaders on the protection of civic space. The Observatory was established within the Open and Innovative Government Division of the Public Governance Directorate in light of a recognition that while many countries were making significant progress in furthering their open government agendas, civic space – which facilitates and underpins open government reforms – was under pressure in different ways in many of the same countries. There is also a well-documented decline in the protection of civic space globally (OECD, 2022[2]).

The OECD approach to assessing civic space, developed in 2020, is articulated in the Civic Space Scan analytical framework in the area of open government (OECD, 2020[3]). The starting point for this work is the OECD’s working definition of civic space:

“Civic space is understood as the set of legal, policy, institutional and practical conditions that are necessary for non-governmental actors to access information, express themselves, associate, organise and participate in public life”.

As this suggests, the OECD approach to civic space is informed by its long-standing focus and expertise on good governance and open government, in addition to its constructive relationship with civil society actors. From a good governance perspective, the work aims to evaluate how existing legal, policy and institutional frameworks, as well as the public sector’s capacities and management practices, shape and affect civic space. The open government focus addresses how these frameworks translate into participatory practices and accountability mechanisms or how civic space can be transformed into a vehicle for effective participation of non-governmental actors in policymaking, decision making, and service design and delivery to contribute to enhancing democratic governance. The intent is that this unique government perspective will support a better understanding of civic space vitality, progress, opportunities, constraints and outcomes at both the national and global levels.

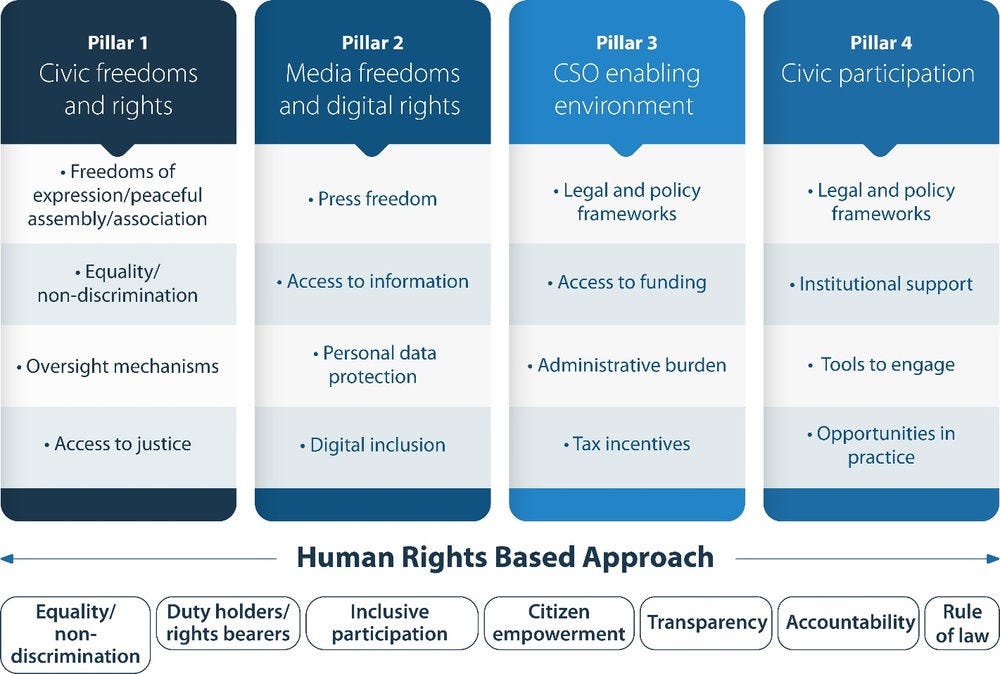

Civic space Reviews (formerly “Scans”) focus on four key thematic areas (Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2):

civic freedoms and rights

media freedoms and digital rights

the enabling operational environment for civil society organisations (CSOs) to operate in

stakeholder and CSO participation in policy and decision making.

Numerous cross-cutting principles – including equality and non-discrimination, inclusion, accessibility, rule of law, citizen empowerment and the impact of COVID-19 – as well as the open government principles of transparency, accountability, and citizen and stakeholder participation are mainstreamed throughout the reports.

Figure 2.1. The OECD’s four pillars of civic space

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Civic Space Reviews provide in-depth qualitative assessments of both theory (de jure conditions) and practice (de facto conditions). The data-gathering process is based on a partnership with the reviewed country. In all cases, the analytical framework is used as a guide, and the precise issues discussed in each Review are determined at the country level (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. The OECD’s analytical framework on civic space anchored in the 2017 Recommendation on Open Government

The OECD’s approach to assessing civic space is anchored in its work on open government. The OECD has been supporting countries around the world to strengthen their culture of open government for years by providing policy advice and recommendations on how to integrate the core principles of transparency, accountability and stakeholder participation into public sector reform efforts. This work culminated in the OECD Recommendation on Open Government in 2017, which defined open government as “a culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth” (OECD, 2017[1]).

Provision 1 of the Recommendation – the only legal standard of its kind on open government – notes the importance of taking measures “in all branches and at all levels of the government, to develop and implement open government strategies and initiatives in collaboration with stakeholders”. Provision 2 focuses on the need to ensure the “existence and implementation of the necessary open government legal and regulatory framework”, while establishing adequate oversight mechanisms (OECD, 2017[1]). Provision 8 recognises the need to grant people “equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted” on governance issues and for them to be actively engaged in all phases of public sector decision making and service design and delivery. Furthermore, the Recommendation advocates for specific efforts to reach out to “the most relevant, vulnerable, under-represented or marginalised groups in society”, while avoiding undue influence and policy capture and for promoting innovative ways “to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions and seize the opportunities provided by digital government tools” (Provisions 8 and 9) (OECD, 2017[1]).

The OECD’s work on civic space is anchored in the recommendation as a facilitator of open government principles and reforms and good governance more broadly. To achieve their full potential, it is essential for open government reforms to be embedded in an enabling environment (OECD, 2016[4]), with clear policies and legal frameworks setting out the rules of engagement between citizens and the state; framing boundaries; and introducing rights and obligations for governments, CSOs and citizens alike (OECD, 2016[4]).

Sources: OECD (2017[1]), “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government”, https://www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Open-Government-Approved-Council-141217.pdf; OECD (2016[4]), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

2.2. Civic space for public services: Adapting the OECD’s Civic Space assessment methodology to the Portuguese context

The OECD’s methodology for assessing civic space has been adapted to Portugal’s particular request to focus on civic space for public service reforms. The overall aim of the Review is thus to support the Portuguese administration in its quest to utilise civic space more effectively to further its ambitious reform agenda of developing more people-centred public services, with a focus on the implementation of its newly developed Guiding Principles for a Human Rights Based Approach on Public Services (Government of Portugal, 2021[5]) (Box 2.2). The Guiding Principles were developed in 2020 during Portugal’s Presidency of the European Union and were in part motivated by a desire to commemorate victims of the Holocaust by embedding human rights in the fabric of government activity.

In line with Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2, the Review analyses the legal frameworks, institutions and practices that support civic space in Portugal, zoning in on how these could currently, or potentially, impact, access to services and service delivery and design. It then analyses two particular services, chosen by the Portuguese administration, in separate case studies, on the basis of which it draws conclusions and makes recommendations on public service reforms more generally.

The two case studies are the Digital Mobile Key (Chave Móvel Digital, CMD) and the Family Benefit for Children and Young People (Abono de Família). The CMD is a means of authentication and digital signature certified by the Portuguese state which allows the user to access several public or private portals and sign digital documents with a single personal identification number (PIN). Any Portuguese citizen with a passport or foreigner with the necessary residency documentation can request a CMD. The Family Benefit is a social security payment in support of children and young people from birth to the age of 24. It can be applied for by parents or legal representatives of a child or young person in their care, or the young person themself if they are over 18. The child or young person and the legal representatives must have a Social Security Identification Number to access the funds.

The analysis of the case studies focuses on exploring how the Guiding Principles are reflected in decision-making and design choices of the service teams responsible for the CMD and the Family Benefit. It seeks to identify opportunities for these services to benefit from civic space in Portugal and in turn, contribute back to its health and vitality (Section 5.4 in Chapter 5).

Box 2.2. A rights-based approach embedded in the OECD’s analytical framework on civic space

A human rights-based approach is a method used to review policies, legal frameworks and initiatives through the lens of human rights and the state’s obligation to ensure them. It is usually based on international human rights standards but can be adapted to an institution’s own standards, depending on the purpose of the evaluation, as in the case of Portugal’s Guiding Principles for a Human Rights Based Approach on Public Services (Government of Portugal, 2021[5]).

A human rights-based approach identifies rights-holders (citizens and stakeholders), duty-bearers (governments) and the civic freedoms that people are entitled to under relevant legal frameworks. It essentially empowers rights-holders to claim their rights and duty-bearers to meet their obligations (OHCHR et al., n.d.[6]; United Nations Development Group, 2003[7]; European Commission, 2014[8]). Accountability and the rule of law are embedded in the approach. Similarly, equality and non‑discrimination and the principles of inclusion (focusing on marginalised and under-represented groups), participation (as a means and a goal) and empowerment are also fundamental components.

As Figure 2.1 illustrates, a focus on rights (e.g. freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly) and a human rights-based approach more broadly, is firmly embedded in the OECD’s analytical framework on civic space (Box 2.1). Indeed, recognising the similarities between Portugal’s approach to service reforms (most notably its Guiding Principles) and the OECD’s human rights-based approach to civic space led the government of Portugal to request that the OECD undertake this Review (Government of Portugal, 2021[5]) (Box 1.2).

Sources: Government of Portugal (2021[5]), Guiding Principles for a Human Rights Based Approach on Public Services, https://www.portugal.gov.pt/en/gc22/communication/document?i=guiding-principles-for-a-human-rights-based-approach-on-public-services; OHCHR et al. (n.d.[6]), Summary Reflection Guide on a Human-Rights Based Approach to Health, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/RGuide_HealthPolicyMakers.pdf; United Nation’s Development Group (2003[7]), The Human Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation: Towards a Common Understanding Among UN Agencies, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/human-rights-based-approach-development-cooperation-towards-common-understanding-among-un; European Commission (2014[8]), Commission Staff Working Document Toolbox: A Rights Based Approach, Encompassing All Human Rights for EU Development Cooperation, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST%209489%202014%20INIT/EN/pdf.

2.2.1. Using civic space to empower and engage citizens and stakeholders

The OECD’s approach to service design and delivery recognises that a diverse range of actors is involved in any democratic society.1 The chain of different actors includes politicians, line ministries and front-line public service providers (including CSOs and the private sector). Public sector accountability is thus based on the relationship between citizens (rights-holders) and public institutions (duty-bearers). Within this framework, citizens are key players in the service delivery relationship as rights holders and the state provides services for the public good as a duty holder. In return, citizens can demand information about performance from public sector institutions and based on this performance, they can enforce accountability, including through formal political mechanisms, such as elections, or informal mechanisms, such as interest groups, protests and public assemblies.

Table 2.1 provides a summary of the intersection between the OECD’s four pillars of civic space and public service design and delivery. When civic space is protected, citizens and stakeholders can be active participants in the services they receive. This participation ranges from setting priorities to planning, tracking budgets and expenditures, contributing to design and delivery, monitoring and evaluating results, providing general oversight, and demanding accountability for public spending. This, in turn, allows governments to form strategic partnerships with civil society and align services and related policies to societal needs, facilitated by protected rights that permit individuals to inform themselves and express their opinions on how services are conceptualised, budgeted and delivered; how efficient and effective they are; as well as the outcomes achieved. Such collaboration is facilitated by protected legal rights (e.g. in constitutions and legislation), access to information (e.g. provided across the public sector and by a free press), effective oversight (e.g. via national human rights institutions, an effective court system and ombudsman offices), relevant institutions (e.g. committees, advisory groups) and practices that respect fundamental rights (e.g. facilitated public protests, access to information offices, public consultations, participatory budgeting exercises and feedback mechanisms on individual services).

Table 2.1. Intersection between the OECD’s pillars of civic space and the public service delivery cycle

|

Civic space pillar |

Intersection with the public service delivery cycle |

|---|---|

|

Civic freedoms and rights |

|

|

Media freedoms and digital rights |

|

|

CSO enabling environment |

|

|

Participation |

|

Source: Based on Jelenic (2021[9]), Background note: Concepts and methods, service delivery and civic space.

Engaging citizens and CSOs as partners in the design, delivery and oversight of services can lead to higher user satisfaction and, potentially, cost reductions. Indeed, such an approach – as outlined in the OECD Serving Citizens Framework (Table 2.2) – can support governments in delivering high-performing public services that are grounded in a people-centric perspective by engaging with end-users and improving: access (e.g. affordability, proximity and accessibility); responsiveness (e.g. treatment, special needs being met and timeliness); and the quality and outcomes of delivery (e.g. effectiveness, consistency and security) (Baredes, 2022[10]). Engaging them as partners in the production and delivery of services also allows for a shift in power between service providers and users. This challenges existing organisational values and practices in the public sector and has real implications for accountability as citizens better understand what government (whether central or local) is doing and use this information to hold policymakers and service providers to account.

Table 2.2. The OECD Serving Citizens Framework

|

Access |

Responsiveness |

Quality |

|---|---|---|

|

Affordability |

Courtesy and treatment |

Effective delivery of services and outcomes |

|

Geographic proximity |

Match of services to special needs |

Consistency in service delivery and outcomes |

|

Accessibility of information |

Timeliness |

Security (safety) |

Source: Baredes (2022[10]), “Serving citizens: Measuring the performance of services for a better user experience”, https://doi.org/10.1787/65223af7-en.

2.2.2. Unleashing the power of digital government to transform public services and protect civic space

The digital transformation of Portugal’s public sector is yielding immense opportunities not only in the design and delivery of public services, but also for the protection and promotion of online civic space more broadly. Digital transformation and the evolution of digital technologies are providing new ways to exercise civic freedoms, access to information and press freedom. Digital tools and technologies are transformational for public services, whether by improving their quality, increasing their availability or simplifying users’ access to them. Moreover, there are opportunities to use quantitative data to anticipate and understand the changing needs of society and to develop tools, platforms and methodologies that more readily source qualitative data and real-time feedback. Overall, digital transformation has helped to create more dynamic and inclusive civic spaces, supporting increased activism and engagement. It has also contributed to opening new online civic spaces, enabling a globally connected civil society to mobilise and advance causes across borders.

Nevertheless, it is also important to recognise the risks and uncertainties associated with digital change, particularly in relation to the public’s trust in the way governments are using technologies and data. This requires governments to be mindful of the unintended consequences of digital innovations and to leverage technologies in ways that ensure citizens and CSOs can fully benefit from them.

The consequences of digital transformation for civic freedoms and civic space are particularly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, given the widespread deployment of digital tools to respond to the global health crisis (OECD, 2022[2]). Tracking technology played a critical role in monitoring people with symptoms and the disease progressed, for example. However, this technology is at the same time raising concerns about personal privacy and civil liberties in the context of mass surveillance. Concerns and challenges to civic freedoms are also arising as a result of other applications, including the role of artificial intelligence in automated decision making and the handling of informed consent for the sharing or reuse of personal data (OECD, 2022[2]; 2020[11]).

Digital technologies and data make it possible for governments to better respond to the needs of their users and to place their needs at the core of policy and service design. This user-centric approach places an emphasis on reflecting and capturing citizens’ demands with greater accuracy, thereby increasing public trust and satisfaction and enabling public participation, all of which can help governments to design and deliver services that work best for users.

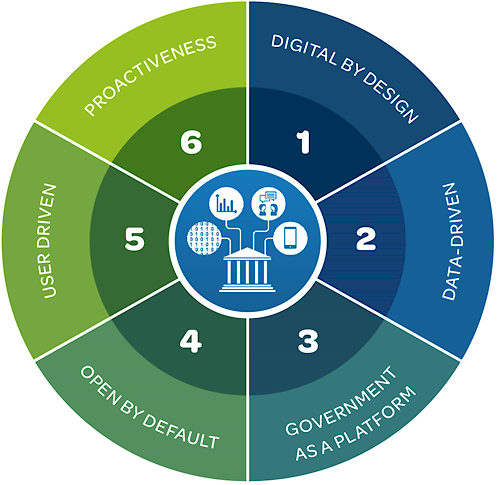

Building on the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[12]), the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework guides governments in their efforts to achieve digital maturity to unleash the potential of digital technologies and data within government. Its six dimensions – digital by design, data-driven, Government as a Platform, open-by-default, user-driven and proactiveness – define a fully digital government (Figure 2.2). Portugal currently ranks tenth among 33 participating countries (29 OECD Members and 4 non-Members) and third among 19 EU countries in the OECD Digital Government Index, which applies the Digital Government Policy Framework to measure countries’ digital government maturity (OECD, 2020[13]; 2020[14]).

Figure 2.2. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework

Source: OECD (2020[13]), “The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a digital government”, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

The Digital Government Policy Framework and the Digital Government Index are mechanisms for understanding the maturity of digital government in general. The effectiveness of these digital government practices can also reflect the health of civic space and, in turn, contribute to protecting, encouraging and enhancing more inclusive, accessible, citizen-centric outcomes. For example, while digital-by-design is the area of the framework concentrating on the structures for organisational governance, the most mature governments are those in which “digital” is a transformational element in the practice of government, allowing for public processes to be rethought and re-engineered so that the needs of all citizens are met. The most digitally mature governments are building the trust and confidence of society through more participatory, inclusive, open and responsive approaches to data, infrastructure and seamless service outcomes (OECD, 2020[13]; 2020[14]).

Chapters 3 and 5 of the Review discuss the relevance of Portugal’s performance in the Digital Government Index in shaping the context within which public service design and delivery is taking place and its associated relationship with civic space.

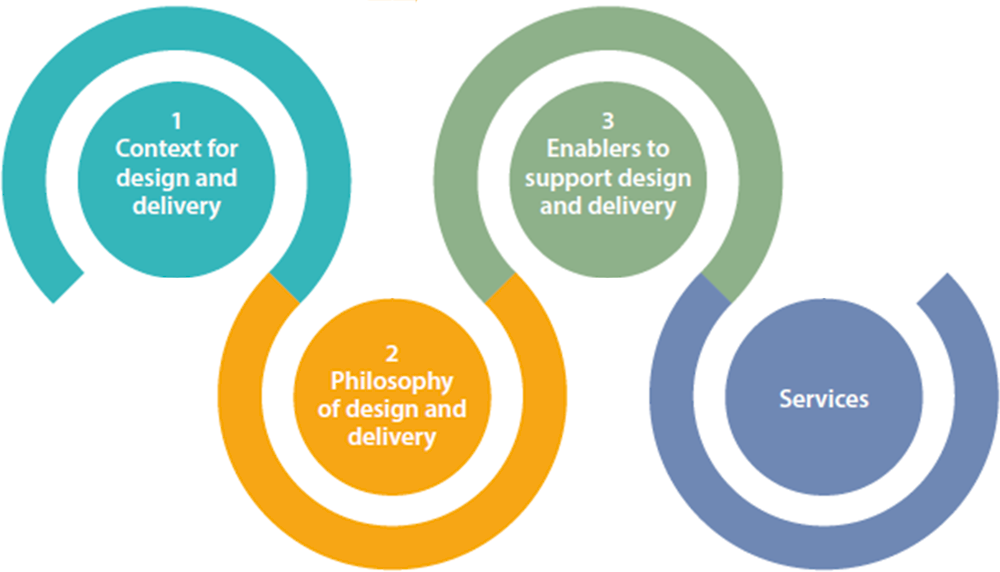

Designing and delivering services that are accountable, inclusive and accessible for all is fundamental to empowering 21st century societies and effectively meeting their needs. As discussed in the previous section, there are several connections between the life cycle of public services and civic space that allow citizens and stakeholders to contribute to those services. In considering the transformation of public services, the OECD Framework for Service Design and Delivery (Figure 2.3) focuses on the country-specific context and philosophy underpinning services, in addition to the availability of enabling resources to analyse the quality of service design and delivery outcomes.

Figure 2.3. OECD Framework for Service Design and Delivery

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government in Chile – Improving Public Service Design and Delivery, https://doi.org/10.1787/b94582e8-en.

The framework consists of multiple elements within each of these pillars but, for the purposes of this Review, the most important elements of the above analytical lens are the following, all of which are discussed in more detail in Section 5.3 in chapter 5.

1. The context for public service design and delivery

The context for service design and delivery related to civic space is shaped by two elements: leadership; and demographics.

Leadership of public services involves the elected political leaders of the country as well as appointed, administrative and operational leaders within individual organisations (OECD, 2020[15]). This includes shaping openness to user participation, determining the nature of delivery channels and influencing a culture of iterating services on an ongoing basis. Clear country leadership that protects civic space and systematically involves CSOs is consistent with efforts to create inclusive, people-centred public services based on the lived experience of users (Baredes, 2022[10]).

In designing and considering access to services and information as well as creating opportunities for citizens and civil society to participate in, and contribute to, service design and delivery, it is essential for providers to consider a variety of different experiences and needs, including people living in urban and rural areas, different generations and people whose lives are shaped by any other demographic characteristic, especially marginalised or vulnerable groups (OECD, 2020[15]).

2. The philosophy of public service design and delivery

The philosophy for public service design and delivery reflects on the behaviour and attitudes that contribute to the wider outcomes experienced by users.

The first question to consider is the extent to which governments understand and respond to whole problems across organisational boundaries and throughout the lives of users. User research helps identify user groups, understand those users’ circumstances and map their journeys through different parts of government until their need is resolved. To design public services that fully respond to users’ needs, it is critical to map and understand the existing landscape of public service provision; the interactions, information and data flows among public sector organisations; and the experience of citizens and stakeholders, including marginalised or under-represented groups. Achieving transformation means addressing whole problems, across all relevant actors and channels, rather than focusing only on discrete or siloed elements of a problem (OECD, 2020[15]). A healthy civic space is important for gaining insights into citizens’ lived experiences based on their feedback, and for encouraging public servants to seek and understand the context of different groups of users. Consultation and feedback mechanisms are valuable tools for understanding the landscape from the users’ perspective and to better address their needs.

A second element is designing public service experiences from end-to-end. After understanding the boundaries of an entire problem, the most effective services solve a problem from start to finish. Public services should be easy to navigate, simple to complete and use data to anticipate and proactively address users’ needs without requiring an unnecessary effort on their part. Regardless of how a government is configured internally, service design should ensure a smooth transition between physical, off line and digital elements of a service to give users access at any point in the process of meeting their needs through their preferred channel, while also simplifying internal processes managed by public servants (OECD, 2020[15]; Welby and Tan, 2022[16]). This approach reflects the need for holistic thinking that goes beyond technological solutions and considers the role of different actors, organisations and tools in responding to society’s needs, taking into account the needs of individuals and their communities.

Third, citizens and stakeholders should be involved as early and as often as possible, in support of the ideas espoused through both the OECD Recommendation on Open Government and the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2017[1]; 2014[12]). Recognising and understanding the users of public services implies not only being aware of the characteristics of society but also creating spaces where people can be brought together to openly share their experiences. To solve whole problems on an end-to-end basis in a proactive and user-driven way, it is critical to identify and work with the potential users of a service. This involves incorporating the views, needs and aspirations of the public from the outset, as well as being open to receiving and acting on feedback on an ongoing basis (OECD, 2020[15]).

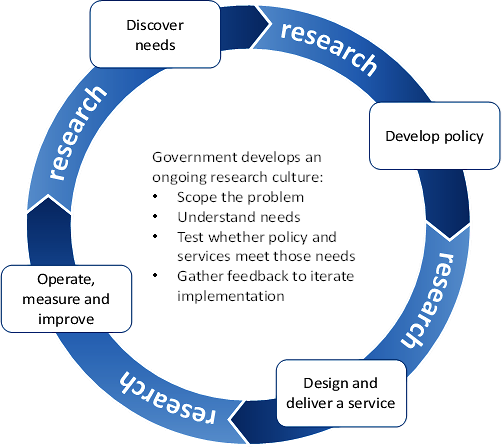

Fourth, governments’ delivery methodology needs to be agile and iterative in order to improve over time. The use of qualitative and quantitative research is an important upfront element in identifying needs and planning for interventions. As Figure 2.4 shows, this process needs to continue throughout the service lifecycle to inform improvements, make changes and ensure that public services continue to meet the needs of their users over time.

Figure 2.4. An agile approach to the interaction between government and the public during policymaking, service delivery and ongoing operations

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government in Chile – Improving Public Service Design and Delivery, https://doi.org/10.1787/b94582e8-en.

3. Key enablers to support public service design and delivery

The enabling tools and resources that governments develop, curate and endorse can help teams to respond more effectively to needs throughout the design and delivery of services. Governing and assuring the quality of digital government design making and service design carried out by public sector organisations is a foundational enabler. The governance of digital government investments involves business case processes, controls on spending and oversight bodies that evaluate proposals before being funded (OECD, 2020[15]; 2021[17]). The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies recognises that business cases are critical for achieving sustainable digital government (OECD, 2014[12]). They can be used to incentivise behaviours such as co-design by offering additional funds, or setting requirements on teams to demonstrate how they will work in ways that are iterative, agile and user-driven in meeting whole problems. They can also help central government actors to build a cross‑government view and identify opportunities to co-ordinate and collaborate across organisational boundaries and avoid operational silos. To ensure that activities are in line with expectations, service standards such as those incorporated into the OECD Good Practice Principles for Service Design and Delivery in the Digital Age are needed, with delivery assessed against those standards, and coaching or consulting provided to support the capacity building of delivery teams (OECD, 2020[15]; 2022[18]). The combination of these measures help central government bodies to reinforce inclusive approaches to service design and delivery that support civic space.

A second area to consider is digital inclusion. Although digital technology and data have the potential to transform the experience of services and enable citizens to engage with government, it is important to recognise that not everyone has equal access to the Internet or the necessary digital skills (OECD, 2020[15]; 2021[19]). To ensure that digital government and data approaches benefit everyone, it is essential to focus on connectivity, digital literacy and accessibility. This is especially important because digital divides can exacerbate existing inequalities (OECD, 2018[20]). The level of connectivity available in a country is also important in achieving digital inclusion. It includes factors such as the availability of high-speed Internet, the extent of mobile data coverage and the cost of data connections. The protection of civic spaces and the quality of service design and delivery are both shaped by access to an open Internet, data protection online and off line, as well as developing digital literacy in society.

Finally, the relationship between a healthy civic space and the design and delivery of public services is influenced by the channels through which services are made available. Public services can be provided by central, regional or local governments and involve dealing with multiple organisations and channels, which can lead to user journeys that switch among phone calls, face-to-face exchanges or online transactions. While citizens can often access public services via this “multi-channel” approach, websites, call centres, self-service kiosks or physical locations often behave as separate silos such that interactions begun online cannot be completed in-person and vice versa. A clear omni-channel strategy can address the confusion and ensure that regardless of the channel a user chooses, they will always be able to seamlessly access a consistent, joined-up, high-quality service (OECD, 2020[15]; Welby and Tan, 2022[16]). When governments consider the needs of all members of society, this includes retaining in-person service channels to complement those interactions that can be handled online or by phone.

The following chapters of the Review assess the core legal and institutional frameworks that protect civic space, analyse the enabling environment for civil society and then consider the specific experience of two public services to understand how civic space can be used more effectively to empower and engage citizens and stakeholders and, with the opportunities offered by digital government, support the transformation of public services in Portugal.

2.3. Methods and tools used

This Review was conducted electronically due to COVID-19. It is based on qualitative and quantitative data gathered using the following methods and tools:

Government background report. The Administrative Modernization Agency (AMA) responded to a questionnaire from the Observatory of Civic Space in February 2021. The detailed questionnaire included 27 questions covering a range of issues on the policy and legal context, Portugal’s strategic vision for civic space, related achievements, challenges in protecting civic space, key actors, oversight mechanisms and related public funding.

Fact-finding mission. Following the official launch of the Review in October 2021, the OECD’s virtual fact‑finding mission took place from November 2021 to February 2022, with some additional interviews taking place between March and May 2022. Interviews were held with 39 separate entities, with public officials from 24 ministries and public institutions, in addition to 15 CSOs. Interviews were frequently followed up by email with requests for information and clarifications and findings from the mission were fully integrated into the report. The team undertaking the Review presented its preliminary findings to AMA in March 2022.

Literature review. The OECD conducted an extensive review of legal texts, government policy and strategy documents, think-tank and academic reports, and government websites both in English and Portuguese.

Legal analysis. As part of a partnership with the OECD, the Library of Congress prepared a background report on Portugal’s legal frameworks governing civic space (Soares and Grozescu, 2021[21]). The report provides an overview of the fundamental rights that are constitutionally protected in Portugal such as the right to access information; freedom of the press; freedom of expression, assembly and association; the right to privacy and data protection; and protection from discrimination. It also provides an overview of laws that further regulate these guarantees, such as on an open Internet, data protection, CSOs and civic participation, in addition to limitations on civic freedoms.

Public consultation. The Observatory of Civic Space held an online public consultation from October 2021 to February 2022, inviting submissions from non-governmental actors on four issues:

1. How can Portugal strengthen its commitment to civic space?

2. How can Portugal strengthen the enabling environment for civil society?

3. How can Portugal strengthen its commitment to citizen participation in public governance?

4. How can Portugal better plan, design, deliver and evaluate public services that respond to citizens’ needs?

The consultation was advertised on the OECD website, the OECD public consultation platform, the OECD Newsletter, the AMA website and on social media. Twenty-seven contributions were received and have been incorporated into the Review.2

Service blueprints. AMA engaged a private contractor to produce detailed service blueprints of the two services examined in detail in the Review (Section 5.4.1 in Chapter 5). To analyse civic space considerations for each service, the objective of the blueprints was to understand the process, institutions, actors and mechanisms underpinning the service delivery chain by mapping the “status quo” of how services are currently rendered. The aim was to consider where citizens may face restrictions in terms of access, inclusion or participation and to identify opportunities throughout the service delivery cycle to promote a more inclusive, accessible and people-centred approach.

Survey on Open Government. The Review includes comparative data from the OECD’s 2020 Survey on Open Government, which included a detailed section on the protection of civic space (OECD, 2022[2]).

Peer review process. Estonia and the United Kingdom participated in the Civic Space Country Review of Portugal as peer reviewers. Following the fact-finding mission and a debrief on the preliminary findings from the OECD team, the peer reviewers provided analytical inputs and shared examples of good practices from their administrations (Boxes 3.5, 3.8 in Chapter 3; and Boxes 4.1, 4.2 in Chapter 4), in addition to reviewing and commenting on the draft Review.

Fact-checking and transparency. The draft Review was sent to the Portuguese government for fact-checking in October 2022. Substantive feedback was received in March 2023 and fully incorporated into the report.

References

[10] Baredes, B. (2022), “Serving citizens: Measuring the performance of services for a better user experience”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 52, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/65223af7-en.

[8] European Commission (2014), Commission Staff Working Document Toolbox: A Rights Based Approach, Encompassing All Human Rights for EU Development Cooperation, European Commission, Brussels, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST%209489%202014%20INIT/EN/pdf.

[5] Government of Portugal (2021), Guiding Principles for a Human Rights Based Approach on Public Services, Ministry of Modernization of the State and Public Administration, Agency for Administration Modernization, Lisbon, https://www.portugal.gov.pt/en/gc22/communication/document?i=guiding-principles-for-a-human-rights-based-approach-on-public-services.

[9] Jelenic, M. (2021), “Backround note: Concepts and methods, service delivery and civic space”, unpublished.

[18] OECD (2022), “OECD Good Practice Principles for Public Service Design and Delivery in the Digital Age”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 23, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2ade500b-en.

[2] OECD (2022), The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d234e975-en.

[17] OECD (2021), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

[19] OECD (2021), “The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 45, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

[3] OECD (2020), “Civic Space Scan analytical framework in the area of open government”, OECD, Paris, unpublished.

[15] OECD (2020), Digital Government in Chile: Improving Public Service Design and Delivery, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b94582e8-en.

[14] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 3, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[11] OECD (2020), “Digital transformation and the futures of civic space to 2030”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 29, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/79b34d37-en.

[13] OECD (2020), “The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a digital government”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

[20] OECD (2018), Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf.

[1] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Open-Government-Approved-Council-141217.pdf.

[4] OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

[12] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

[6] OHCHR et al. (n.d.), Summary Reflection Guide on a Human-Rights Based Approach to Health, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Geneva, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/RGuide_HealthPolicyMakers.pdf.

[21] Soares, E. and G. Grozescu (2021), Civic Space Legal Framework: Portugal (April 2021), Romania (November 2021), Law Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021687420.

[7] United Nations Development Group (2003), The Human Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation: Towards a Common Understanding Among UN Agencies, United Nations Development Group, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/human-rights-based-approach-development-cooperation-towards-common-understanding-among-un.

[16] Welby, B. and E. Tan (2022), “Designing and delivering public services in the digital age”, Going Digital Toolkit Note, No. 22, OECD, Paris, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/data/notes/No22_ToolkitNote_DigitalGovernment.pdf.