The risk of economic insecurity is ever-present in European OECD countries – as individuals often face employment changes and income shocks and may lack sufficient liquid assets to cope with them. The burden of economic insecurity falls heavily on those who are disadvantaged and in a precarious position – people on low incomes, the unemployed and insecure workers – but the consequences are felt more broadly across society. Governments have a role in reducing people’s exposure to adverse economic events and enhancing their ability to manage risk. Social benefits, in particular, play an important role in reducing income instability – notably when they are responsive to changes in people’s circumstances, which can vary dramatically from month to month. In addition, policies that support financial literacy and help people to build their savings and manage debt are important for financial resilience and well‑being, especially in constrained fiscal environments. More broadly, policies should work in concert to reduce the risks of economic insecurity.

On Shaky Ground? Income Instability and Economic Insecurity in Europe

3. Policies to reduce economic insecurity

Abstract

3.1. How can policies address economic insecurity?

The preceding chapters revealed the extent and negative consequences of economic insecurity on individuals, their families and society at large. Nearly one in six people in working-age households face economic insecurity, with the burden falling disproportionately on the unemployed and insecure workers – the very people who often rely on social protection and other government support. Governments should ensure that their policies and programmes are tailored to the needs and circumstances of people who experience or are vulnerable to economic insecurity – noting that people’s circumstances and needs can change suddenly and frequently, as demonstrated throughout this report.

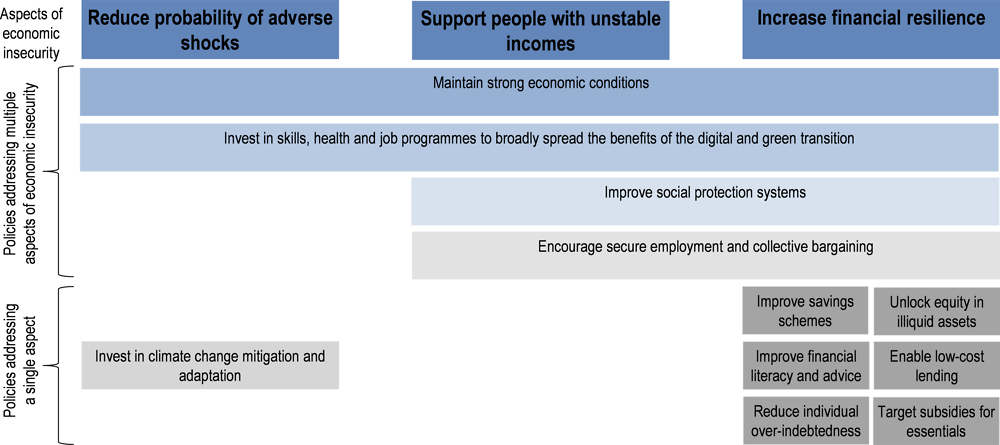

Policies should address people’s exposure to negative shocks and help them to better manage risk. Government policies may directly target a single aspect of economic insecurity (for instance policies that seek to boost individuals’ capacity to acquire financial resources, or policies that supplement incomes during unemployment). Alternatively, some policies act on multiple aspects of economic security by reducing the risk of negative economic effects and smoothing incomes, which in turn set the conditions for individuals to build financial buffers. Figure 3.1 depicts a suite of policies that can address (aspects of) economic insecurity. The policies are grouped by what they aim for: ensuring general economic stability, developing conditions for more secure and higher-paying jobs, supplementing incomes when individuals experience a shock, assisting individuals in generating wealth, or maintaining individuals’ consumption of essential goods and services as prices rise (see the columns in Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Policy options for addressing different aspects of economic insecurity

This is not an exhaustive list – nor an indication of the relative sizes of the policy impacts – but rather an illustration of the wide variety of policies that can be used to tackle economic insecurity. For example, governments can:

promote strong economic conditions to maintain price stability and foster quality job creation and income growth that benefits all segments of the population;

encourage people to invest in skills development to improve their job prospects, particularly for people working in occupations, industries or geographic areas facing structural change;

provide financial support (social protection) to people experiencing financial hardship or unemployment; and

introduce regulation to enable low‑cost lenders such as credit unions and to limit predatory lending practices.

The effects of these policies will depend on the contexts in which they are implemented, including how they function within the broader suite of policies. They are, however, all important and should work in concert as a policy package to mitigate economic insecurity (Sologon and O’Donoghue, 2014[1]).

Rather than discussing each of these policy areas, this chapter focuses on ways to improve policies based on the findings in the previous chapters that monthly income changes are a key driver of economic insecurity and that many of those on highly unstable incomes have limited financial buffers. As such, this chapter focuses on the timeliness of social protection payments (Section 3.2) and programmes aimed at strengthening people’s financial well-being and resilience by boosting their savings, improving their financial literacy and increasing their access to low-cost financial services and debt relief (Section 3.3). While social protection is the primary way to reduce income instability for lower-income earners, policies to increase financial literacy, resilience and well-being are becoming more important, as countries face a limited scope for future public spending given the large-scale fiscal responses to COVID-19 and the subsequent cost‑of‑living crisis. The stocktaking of policies includes non‑European OECD countries and is informed by desk research and validated by national administrations. A high-level overview of policy options and programmes for a selection of OECD countries (i.e. Germany, Greece, France, Ireland, Latvia, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States) covering policies up to July 2022 is provided in Annex 3.A.

3.2. Making social protection more timely

While social protection systems have traditionally been designed to provide a safety net, their role in reducing economic insecurity is increasingly recognised given labour-market digitalisation (OECD, 2019[2]). People who experience economic insecurity face the greatest risk from automation and have fewer opportunities to benefit from artificial intelligence technologies than people in occupations that face a lower risk of economic insecurity (Chapter 2). Those who experience economic insecurity are also more likely to lack job security (i.e. to be on temporary or no employment contracts), which makes them vulnerable to falling through the cracks of social protection systems that have not adapted to modern labour markets (OECD, 2019[2]). Prior to COVID‑19, two‑thirds of job seekers in the OECD did not receive unemployment benefits because they were ineligible – as they were self-employed, temporary workers who did not meet minimum contribution durations, or unemployed for so long they went over the maximum duration of benefits (OECD, 2023[3]). COVID‑19 exposed the gaps in social protection systems, and some countries including Italy, Germany, France and South Korea, are considering extending income protection to those who have not typically been eligible (OECD, 2023[3]).

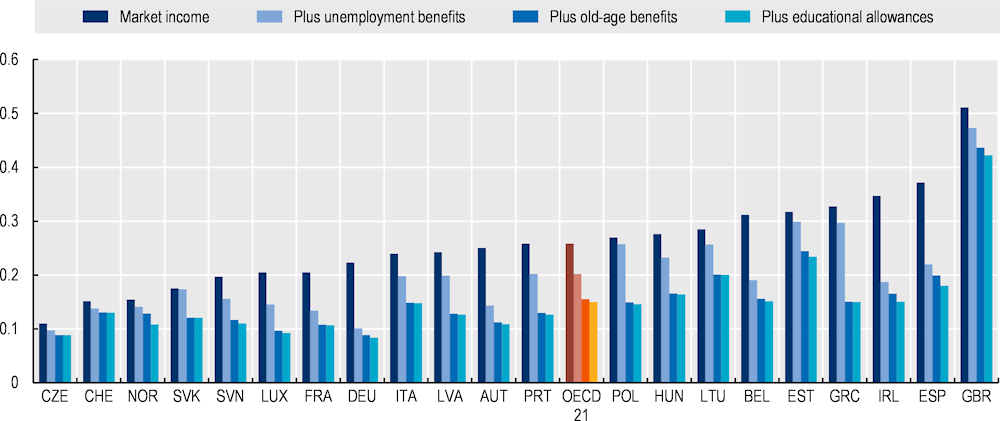

Even with the gaps in coverage, social protection systems play an incredibly important role in reducing income instability, and thereby the risk of economic insecurity (Salgado et al., 2014[4]). Unemployment benefits, old-age pensions and education allowances reduce income instability in total by 42% on average in the European OECD countries covered in the analysis (Figure 3.2). The total effect of social protection systems on income instability is likely to be even higher, as important benefits, such as child allowances and disability pensions, could not be incorporated into this analysis, because they are difficult to attribute to individuals’ employment patterns.1

The size of the effect of social protection on income instability differs widely across countries (Figure 3.2) (Rohde, Tang and Prasada Rao, 2014[5]). Social benefits reduce income instability by more than half in Germany (63% reduction), Ireland, Austria, Luxembourg, Greece, Spain, Belgium and Portugal. The reductions in social protection are more modest (less than 20%) in the Czech Republic and Switzerland, which have low levels of instability, and in the United Kingdom, which has the highest level of income instability among the countries studied. Indeed, even once social benefits are accounted for, the level of income instability in the United Kingdom is still higher than the level of instability unadjusted for social benefits in all other countries. And while unemployment benefits make the largest contribution to the reduction in instability in most countries, old-age pensions have a relatively larger effect on instability in Greece, Portugal, Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, Lithuania and Estonia. Education allowances play a minimal role in smoothing incomes in all countries (as illustrated by the negligible difference between the third and fourth bars in Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Social benefits reduce instability by 40% on average across European OECD countries

Note: Income instability is measured by the average squared coefficient of variation of monthly equivalised household income over 48 months. The dark blue bars measure instability before accounting for social benefits by using the market incomes constructed in Chapter 1. The light blue bars add unemployment benefits to market incomes to measure instability after accounting for unemployment benefits. Next, the third set of bars adds old-age benefits to market incomes and unemployment benefits. The final set of bars adds in educational allowances and thus represents the total measurable effect of social benefits on instability. However, the total measurable effect does not include all social benefits, such as child allowances. See Chapter 1 for more information. The analysis is carried out only on households with stable composition over 48 months and whose main employment income earner is aged between 18 and 59. The unit of reference is the individual.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU‑SILC), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions.

Box 3.1. Policy measures to reduce economic insecurity during economic crises

Governments use various fiscal policy measures to smooth incomes and maintain real living standards during periods of heightened economic uncertainty. For instance, in response to the recent cost-of‑living crisis, many governments introduced inflation relief measures to reduce prices (such as energy price caps and lower taxes on energy) and/or boost household incomes via transfers and tax credits. However, due to difficulties in identifying energy users most in need of support, more than three-quarters of measures were untargeted. Consequently, this worsened economy-wide inflationary pressures and entailed a high total gross fiscal cost of 0.7% of GDP in 2022 and 0.8% in 2023 in the median OECD country, and in excess of 3% of GDP in Greece, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Italy, France, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic (Hemmerlé et al., 2023[6]). Further, energy price measures may reduce incentives to save energy and switch to low-carbon alternatives (although some countries, including Germany, Italy and France, rolled out energy-saving campaigns as well) (Hemmerlé et al., 2023[6]).

Coupled with measures to reduce the burden of price increases, governments raised minimum wages to boost the incomes of vulnerable households. These measures were targeted to those most in need of assistance and were often linked to consumer price changes. Almost all OECD countries raised their minimum wages between January 2021 and September 2022, but most increases were too modest to maintain the real minimum wage rate. In some countries, such as Latvia, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Lithuania, France, Ireland and the United Kingdom, increases in minimum wages were almost entirely cancelled out by the withdrawal of social benefits or higher income taxes – highlighting the importance of the interactions between minimum wages, taxation and social protection (OECD, 2022[7]).

However, some countries are adapting their social protection systems in light of recent labour market developments and to be more responsive to economic crises. For example, in France, the duration of unemployment benefits now depends on macroeconomic conditions, such as the strength of the labour market. Greece is considering similar changes. Moreover, Italy, Germany and France are considering permanently extending social protection to people not traditionally covered – including non-standard workers and the self-employed – following the expansion of their social protection systems during COVID-19. Germany is also removing sanctions in the first six months of an unemployment spell to improve incentives to train or find better jobs rather than take the first available job (OECD, 2023[3]).

Finally, governments expanded or introduced short-term work schemes to stabilise incomes and maintain people’s employment connections during COVID-19, given their success in preventing unemployment in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (Kopp and Siegenthaler, 2021[8]; Christl et al., 2022[9]). All European countries except Malta and Finland had short-term work schemes that subsidised companies to maintain their workforces (European Training Foundation, 2021[10]). Pre‑existing schemes were adapted in several ways: softening eligibility rules and extending coverage to include atypical employment and the self-employed, as well as other sectors not previously covered.

Given the income-smoothing effects of social protection systems, it is crucial that they operate in ways that are responsive to the needs and circumstances of people experiencing, or at risk of, economic insecurity. There are large differences in the design of social protection systems in OECD countries in terms of the types of benefits and tax credits, the amounts recipients receive, their duration, the accessibility requirements and the take‑up rates.2 Many governments have also introduced inflation relief, raised minimum wages and designed short-term work schemes that operate alongside social protection systems to support people at risk of economic insecurity, particularly during economic crises (Box 3.1). These are all important considerations when designing social protection systems, and they may all have implications for economic insecurity – especially the size of payments, the interactions with work incentives and payment take‑up rates. However, this chapter focuses on an often overlooked design feature that affects people with unstable incomes – the timeliness of social protection payments.

The frequency of benefits and tax credits can affect people’s financial stability

The frequency of unemployment and other benefit payments differs across countries, typically in line with how often people are paid when they have a job – weekly (e.g. in New Zealand), fortnightly (e.g. in Australia and Norway) or monthly (in most OECD countries) (Summers and Young, 2020[11]). Matching the frequency of social protection payments to the employment payment cycle can help people maintain a familiar routine for managing household expenses. However, the lengthier the frequency, the more difficult it can be for people to budget, particularly if they have low incomes or are liquidity constrained. Having difficulty managing household expenses due to infrequent social protection payments is associated with a range of negative well‑being effects, including stress and feelings of lack of control (Scottish Government, 2021[12]), electricity service disconnection and bill-related debt (Barrage et al., 2019[13]), increased hospital admissions and mortality (Seligman et al., 2014[14]) and food insecurity. Anecdotally, in the United States, food banks stock extra supplies at the end of the month to meet the surge in demand from people whose social benefits have run out (Seligman et al., 2014[14]). Indeed, one American study found that increasing the frequency of unemployment benefit payments produces a similarly sized effect as raising the payment amount, without materially increasing administrative costs for governments (Zhang, 2021[15]).

Like unemployment and other social protection payments, the frequency of tax credits for people in work (but on low incomes) can have a marked effect on well‑being. When tax credits are calculated and delivered on an annual basis, they may fail to be responsive to changes in people’s circumstances. For instance, the annual lump-sum payment of the Earned Income Tax Credit in the United States increases income volatility (Maag, Congdon and Yau, 2021[16]), while, based on small-scale demonstration projects in Chicago and in Colorado in 2013 and 2014, periodic payments can improve households’ financial stability and help with keeping up with bills, paying down debts, covering essential expenditures such as food, and decreasing borrowing (both formal and informal) (Maag, Congdon and Yau, 2021[16]; Bellisle and Marzahl, 2015[17]; Kramer et al., 2019[18]; Greenlee et al., 2021[19]). Some emerging research on the recent temporary expansion of Child Tax Credits under the America Rescue Plan Act also indicates that periodic payments reduce material hardship, particularly in relation to food insecurity (Perez-Lopez, 2021[20]; Roll et al., 2021[21]; Parolin et al., 2021[22]).

Striking the right balance with waiting times for benefits

Another key factor affecting the timeliness of social protection is how long it takes to receive the first payment after applying. About half of OECD countries have waiting periods, and many others have long processing periods. While it takes on average two weeks for people in OECD countries to receive unemployment benefits after they apply, in some countries people can wait up to five weeks, as payments are made monthly in arrears.

Waiting periods are used to review applications, to reduce administrative costs (by deterring people from making claims for short periods of unemployment) and to promote job stability by disincentivising people from alternating between temporary jobs and unemployment (OECD, 2018[23]). However, waiting many weeks for a first payment can cause severe financial distress and is associated with increased food bank use and a heightened risk of falling into poverty (Cooper and Hills, 2021[24]; O’Campo et al., 2015[25]). In the United States, the first payment takes place about two weeks after an application (Greig et al., 2022[26]), whereas in Canada it can be up to 28 days before claimants receive the first payment, for instance in Ontario (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2022[27]). In the United Kingdom, Universal Credit is paid monthly in arrears, resulting in a five-week wait for the initial payment. Recipients can request advance payments from the government, which are then paid back as deductions from the benefits received.

Some countries tailor their waiting periods to people’s circumstances. In order to prevent economically insecure people from waiting too long for their first payment, the United Kingdom and France waive waiting periods for those who have long or repeated spells of unemployment (Carter, Bédard and Bista, 2013[28]). Conversely, people who leave their jobs voluntarily face a prolonged waiting period in a number of countries: an extra three weeks in Denmark, twelve weeks in Germany and Norway, three months in Japan and New Zealand, and four months in France (Carter, Bédard and Bista, 2013[28]).

Reducing delays due to means testing and having payments that reflect people’s current circumstances

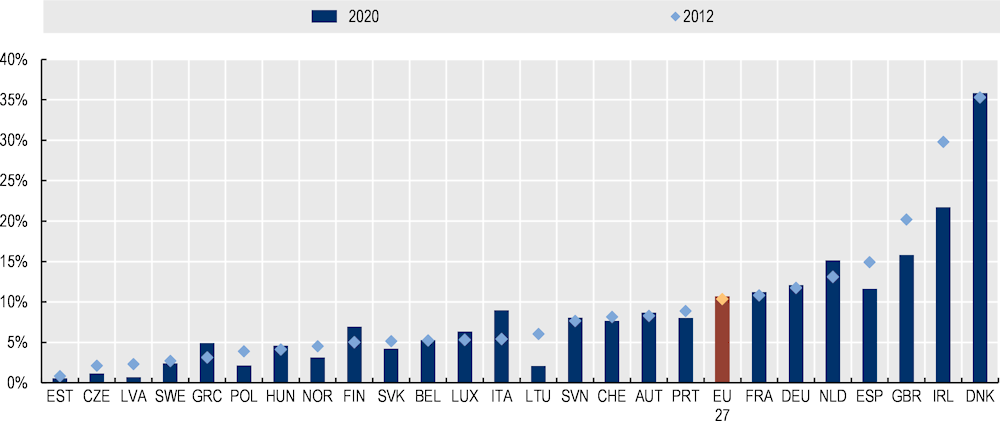

Many European countries do not means test their unemployment benefits – as they are based on individual contributions to insurance schemes – although they use means testing to allocate family and housing benefits. Over the past decade, 11% of all social benefit expenditure has been means tested in Europe on average, although the range spans from 36% in Denmark and 20% in Ireland to only 1% in the Czech Republic, Poland and the Baltic countries (Figure 3.3). However, the shares may have fallen in 2022, as many European governments introduced temporary measures to combat rising inflation that were predominately untargeted (including non-means-tested benefits (Hemmerlé et al., 2023[6]).

Figure 3.3. The share of means-tested benefits varies widely across European OECD countries

Note: The most recent data point for the United Kingdom is 2018.

Source: Eurostat Social Protection Statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/social-protection/data.

Means testing helps to target social protection to those most in need; however, it can also make application processes more complicated and time-consuming, which can discourage people from taking up benefits and tax credits (Eurofound, 2015[29]). In France, the Prime Pour l’Emploi tax credit had complex arrangements and was paid up to 18 months after individuals became eligible, which obscured the link between individuals’ behaviour and financial reward and constrained take-up (Immervoll and Pearson, 2009[30]). In addition, long waits can translate to payments that do not reflect people’s current circumstances, which may undermine households’ financial security (Millar and Whiteford, 2020[31]) On the other hand, if income assessment periods are too short, people with highly unstable incomes may be penalised (OECD, 2019[2]). For households that have fluctuating incomes in the short-term (say for example because their employment changes seasonally) but who can smooth consumption over time, a longer time frame would give a more accurate assessment of their financial welfare.

Some countries use automatic enrolment and have redesigned their means-testing arrangements to make it easier for people to access all payments for which they are eligible (Ambegaokar, Neuberger and Rosenbaum, 2017[32]). For instance, in Canada, citizens who file tax reports are automatically reviewed for their eligibility for the Canadian Work Benefit tax credit. Canadians are paid quarterly in advance (max 50% of the entitlement) based on their estimated income, while the remaining part of the award is paid following the yearly tax assessment. This approach incorporates both individuals’ current circumstances and their average circumstances over the longer term – thereby comprising the benefits of both short- and long-term assessment periods. As the scheme can be modified in different provinces, some have also opted to increase the responsiveness of the system by introducing quarterly assessments (Kesselman and Petit, 2020[33]).

3.3. Government programmes to build financial literacy and resilience

In contrast to social protection (which provides financial support to people with low, unstable incomes), government‑backed saving, advice and financial literacy strategies aim to enhance people’s financial resilience to shocks. This includes providing incentives for building up financial buffers or equipping people with the knowledge and skills to improve their financial well-being.

Improving the targeting of savings incentives

A range of schemes have been developed to help boost people’s savings, including:

tax incentives such as removing tax on the interest earned on savings;

matching people’s savings;

index-linked bonds or guaranteed minimum interest rates; and

prize‑linked savings accounts, whereby higher interest rates, cash prizes or in‑kind benefits are randomly distributed to savers.

Tax-incentives and index-linked bonds are the most popular schemes in the selected OECD countries studied, although all countries use a mix of schemes to encourage savings among lower-income people or for particular purposes, such as retirement – see Annex 3.A, (OECD, 2019[34]). Schemes that encourage people to save cushion them from negative shocks and have been shown to benefit employment, earnings, family stability, physical health and psychological well-being (Bynner and Paxton, 2001[35]; Sherraden, 2009[36]; McKnight, 2011[37]). The protective effect on subjective financial well‑being from savings appears to be larger than other forms of liquidity – such as credit card use (Bufe et al., 2022[38]).

However, the effectiveness of these schemes depends on their design, as some tend to lead to asset reallocation rather than to new savings, and they are under‑subscribed by people on low incomes – those most at risk of economic insecurity. There is a strong consensus among researchers that tax incentives lead to a reallocation of assets, particularly for voluntary schemes (Breunig and Sobeck, 2020[39]; OECD, 2018[40]; Fadejeva and Tkacevs, 2022[41]). Further, people on low incomes have lower take‑up rates of tax incentives than higher‑income people, because they pay less tax and thus have a smaller incentive than higher‑income people to participate in tax‑advantaged savings schemes.

People on low incomes are more likely to use prize-linked schemes, matched savings schemes and index‑linked schemes than tax-based schemes. Studies have shown that, unlike tax‑based schemes, programmes that encourage savings through financial incentives such as contributions from governments or more attractive interest rates are popular among people on lower incomes, particularly those with little savings. These schemes have been shown to increase savings for people on low incomes, build savings habits among people with little history of savings, bring forward home ownership and the purchase of household durables, increase educational investments, encourage people to start small businesses, and have broader social benefits, such as reducing spending on lotteries (Atalay et al., 2012[42]; Kearney et al., 2011[43]; Schreiner, 2004[44]; Harvey et al., 2007[45]; Azzolini, McKernan and Martinchek, 2020[46]). In the case of index-linked schemes, there are other benefits, including hedging inflation risks, which is especially important in the context of a cost-of-living crisis where non-indexed savings accounts can be eroded by inflation (OECD, 2022[47]).

When designing savings schemes, governments should consider how features interact, and what other supports can encourage savings by targeted groups. For instance, evidence suggests that the matching threshold (the point at which co‑contributions cut out) is more important than the contribution rate in influencing how much people save (Madrian, 2012[48]). The threshold acts as a natural reference point for savers and may be interpreted as a recommended savings level (Madrian, 2012[48]). As discussed below, savings schemes could also include reminders and smartphone notifications to prompt people to make a deposit; automatic deposits or other commitment devices; planning aids; and automatic enrolment, alongside coaching and financial education (Madrian, 2012[48]).

Finally, matching schemes should be tailored to people’s circumstances, such as by linking thresholds and contribution rates to individual income and by only opening the scheme for people on low incomes. This would attract more people on low incomes, and in turn, make the schemes more progressive (Azzolini, McKernan and Martinchek, 2020[46]). For example, the United Kingdom’s Help to Save scheme is open only to people who receive social protection benefits, such as the Working Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit and Universal Credit. People who open savings accounts through the scheme can receive a 50% bonus payment of up to GBP 1 200 over four years. Three-quarters of participants were not regular savers before they opened an account as part of the scheme, and 86% are saving more than they previously did (HM Treasury, 2023[49]). However, participants only save a modest amount through the scheme, GBP 48 per month, which indicates that savings schemes for low‑income people are unlikely to fully address financial precarity, nor vastly improve their savings capacity. As such, these schemes should be seen as complements, rather than substitutes, to well‑functioning social protection systems (McKnight and Rucci, 2020[50]).

Improving financial literacy

Financial literacy is an essential life skill that gives people the awareness, knowledge, skills and confidence to make sound financial decisions and ultimately improve their material conditions and opportunities (OECD, 2020[51]) This can involve building and managing wealth, avoiding high-cost lenders and using new technologies to find the best financial offers (French and McKillop, 2016[52]; European Union/OECD, 2022[53]; Blanc et al., 2015[54]). Unfortunately, there is a dearth of financial literacy skills.Three-quarters of people surveyed from 26 OECD and non-OECD countries could not answer questions about simple and compound interest correctly, and less than half met the minimum targets for financial attitudes and behaviours, such as saving, planning for the future and keeping control of personal finances (OECD, 2020[55]) . These consequences are more pronounced in people who are at risk of economic insecurity, as they tend to have lower levels of financial literacy than people with higher incomes (Collins, 2012[56]).

Governments have developed national financial literacy strategies and implemented a plethora of financial education programmes, in a range of settings such as schools, universities and workplaces, and as part of targeted savings schemes, active labour market programmes and debt counselling services (OECD, 2015[57]; McKnight, 2018[58]; OECD, 2022[59]). Evaluations of financial education programmes have found that they are most effective when tailored to people’s specific needs – such as individualised financial counselling, programmes designed for target groups, including young people and those with low incomes, or programmes delivered when people are making key financial decisions like retiring (Miller et al., 2015[60]; Kaiser and Menkhoff, 2017[61]; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014[62]; Goyal and Kumar, 2020[63]; OECD, 2020[51]; OECD, 2017[64]). Many effective financial education programmes are underpinned by holistic national financial literacy strategies, which promote a long-term, co-ordinated approach to financial literacy (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Characteristics of successful national financial literacy strategies

Over the past decade, many countries have developed comprehensive national strategies, which have been guided by the OECD International Network for Financial Education (OECD/INFE) (OECD, 2022[65]; 2013[66]; 2012[67]; 2020[51]; 2017[64]). The keys to successful national financial education strategies include:

recognising the importance of financial literacy – through legislation where appropriate;

coherence with strategies for fostering economic and social prosperity;

cooperation with relevant stakeholders and identification of a national leader or coordinating body; evidence-based roadmaps or action plans to achieve objectives within set timeframes;

guidance on implementing individual programmes;

monitoring and evaluation to assess the progress of the strategy and propose improvements;

earmarking sustained funding for financial literacy programmes;

instituting flexible governance structures that involve public, private and civil society stakeholders;

providing information to the public in different ways such as interactive web-based tools and awareness campaigns;

tailoring programmes to the needs, circumstances and contexts of the audience through life‑cycle approaches and leveraging trusted intermediaries and learning environments (such as workplaces and schools); and

empowering people to engage in the programmes and apply what they learn by using the insights of behavioural economics and social marketing (OECD, 2015[57]).

National strategies for financial literacy are complex, multi-year, multi-stakeholder public policy projects that can strongly benefit from comprehensive evaluation designs. Recent OECD/INFE work (2022[65]) has focused on monitoring and evaluating the national strategies of 29 jurisdictions and shows that one-fifth of countries do not have an evaluation plan, and a quarter articulate aspirational goals that are not linked to quantitative measures, which makes it difficult to assess strategy effectiveness.

Countries that have evaluated their national strategies and used the results to inform the development of successive strategies have found that evaluation needs to be embedded from the outset. This is based on the design of indicators, the collection of data and transparency with stakeholders – which enhances stakeholder trust and “buy-in” (OECD, 2022[65]). In turn, these ingredients build confidence in the results of the evaluation and in the subsequent adjustments made to the strategies.

Increasing access to high-quality financial advice

Financial advice is an important enabler of financial literacy, but often people on low incomes and other vulnerable consumers face barriers to accessing high-quality advisory services (Collins, 2012[56]; OECD, 2022[68]). Individuals with higher income, education and financial literacy levels are more likely to receive financial advice, which boosts their confidence in engaging with financial services and improves their investment performance (von Gaudecker, 2015[69]; Collins, 2012[56]; Lusardi, Michaud and Mitchell, 2017[70]). In contrast, low-income households find financial advice too costly or do not have the financial knowledge to seek out support (Lusardi, Michaud and Mitchell, 2017[70]). As such, those on lower incomes and with lower financial literacy rely, to a greater extent, on social networks and family rather than on professionals for financial advice (Lu and Lim, 2022[71]). Taken together, disparities in access to financial advice, and to financial knowledge more generally, contribute to wealth inequalities (Lusardi, Michaud and Mitchell, 2017[70]).

To increase the availability of high‑quality financial advice, governments have made regulatory changes to reduce fees for advice, remove conflicts of interest such as commission‑based advice and encourage new digital advice options (Financial Conduct Authority, 2020[72]; OECD, 2017[64]). While these measures have improved the quality of advice, the cost of advice is still prohibitive for people on low incomes, and they are still unlikely to use advisory services for financial planning or to make investments (Burke and Hung, 2015[73]; Krishnamurti et al., 2022[74]; Financial Conduct Authority, 2020[72]).

Targeted financial support, such as rebates for people with low incomes or wealth, could expand their access to financial advice (Krishnamurti et al., 2022[74]). Indeed, one area where people with low incomes use advisory services is in relation to debt – where public funding and provision are more common. Debt advice can assist people with low incomes to manage their finances and reduce debt (Eurofound, 2020[75]; Hartfree and Collard, 2014[76]; Orton, 2010[77]). These services can help people identify the causes and extent of their debt problems, maximise their income, minimise expenses, prioritise debts, exercise their consumer rights and make realistic repayment plans with creditors (Stamp, 2012[78]). Debt advice can be particularly important for addressing economic insecurity, as people with limited financial buffers often rely on borrowing to meet their living expenses. In the absence of debt advice, low-income people may be unable to pay off their debts (resulting in delinquency) or rely on loans from high‑cost lenders – putting them at a greater risk of over‑indebtedness.

Many countries provide publicly funded debt advice services for people with low incomes. For example, Norway offers free advice on individuals’ financial situation, debt settlement and debt write-offs through financial advisors at their local Labour and Welfare Administration office (NAV, 2023[79]). Effective programmes provide personalised advice from trained advisers, who build trusted relationships with customers, creditors and authorities. In addition, debt advisory services can be especially effective when paired with other social services typically used by people with low incomes or those experiencing poverty, including mental health care, employment and welfare services (Eurofound, 2020[75]; Stamp, 2012[78]). These holistic services can help with early intervention and increase people’s awareness of available debt solutions, which are often lacking.

While debt advisory services alleviate pressing debt problems for people with low income, they do not address the underlying causes of over‑indebtedness, which include job loss, poor health or the absence of low‑cost financial products (Stamp, 2012[78]). A different, complementary suite of policies is needed to target the deeper causes of indebtedness, some of which are discussed in the next section.

Ending the cycle of over-indebtedness and debt delinquency

The past two decades have witnessed an increase in household debt and over-indebtedness (with debt levels over three times households’ disposable income) in the United States and Western Europe (Angel and Heitzmann, 2015[80]; Fligstein and Goldstein, 2015[81]; Jappelli, Pagano and Di Maggio, 2013[82]; OECD, 2021[83]). Over-indebtedness levels are highest amongst people with low incomes, but the middle class is increasingly at risk, particularly during times of economic crises, given its high rates of financial fragility (see Chapter 2 and OECD (2021[83])).3 The cost-of-living crisis is likely to be pushing even more households into over-indebtedness – and increasing its severity for already-over-indebted households – as monetary policy tightening pushes up borrowing costs relative to incomes.

Some countries, such as Poland, have introduced temporary mortgage moratoria to help households struggling to make their repayments in a tight monetary policy environment. Households in Poland could suspend their mortgage repayments for four months in 2022 and another four months in 2023 (Ptak, 2022[84]). This effort comes off the back of Poland’s loan repayment holiday during COVID-19, which enabled households and businesses to pause their payments for three to six months so long as they could document that they were in financial stress (Hogan Lovells, 2021[85]). Other European countries4 also introduced loan repayment holidays to respond to COVID‑19, including Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom (Hogan Lovells, 2021[85]). Countries’ schemes were designed for their individual contexts and so varied considerably in terms of the duration of the payment pause and the types of debts and groups covered: low‑income debtors, all consumers and/or businesses (Hogan Lovells, 2021[85]). In some countries, banks agreed to loan repayment holidays without the force of legislation.

While governments and banks introduce loan repayment holidays during times of crisis, it is not the first line of defense against over-indebtedness. People experiencing, or at risk of, economic insecurity may struggle to access low‑cost financial services and resort to high‑cost options such as payday lending to purchase essential goods and services or to pay down existing debts (OECD, 2022[68]). High‑cost borrowing options keep people on low incomes in a vicious cycle of debt, as large proportions of their income go towards paying their debts. This in turn makes it difficult for them to meet their basic costs of living without resorting to more debt and to fully participate in the economy and live without financial stress.

In an attempt to break the debt cycle, governments have regulated the financial system by limiting the supply of high‑cost lenders or capping interest rates. For instance, The EU Directive on Consumer Credit (Directive 2008/48/EC amended in 2011, 2014, 2016 and 2019) has provided a broad framework for member states to implement their own legislation on consumer credit. The Directive has focused on “unfair terms in consumer contracts”, online marketing and misleading advertising. Proposals for further amendments of the directive include extending its scope to cover loans below EUR 200 (common threshold for payday loans), interest‑free credit, all overdraft facilities and all leasing agreements, credit agreements concluded through peer-to-peer lending platforms as well as prohibition of the unsolicited sale of credit products and establishment of the obligation to set caps on interest rates.

There are, however, risks to limiting access to high-cost borrowing. Bans on high‑cost credit services in the United States shifted customers to other high‑cost alternatives that use emerging digital technologies (Friedline and Kepple, 2017[86]; Bhutta, Goldin and Homonoff, 2016[87]). Similarly, interest rate caps often result in limiting access to finance, particularly for younger and poorer segments of the population, as high‑risk borrowers end up being excluded from the formal financial system (Ferrari, Masetti and Ren, 2018[88]; Ellison and Forster, 2006[89]; Madeira, 2019[90]; Financial Conduct Authority, 2017[91]). Other side effects are increases in non‑interest fees and commissions (which reduce price transparency and complicate the system), as well as reductions in the number of lending institutions and branch density.

Nevertheless, regulation can play an important redistributive and inclusive role by increasing access to financial services for people at risk of economic insecurity (Ferretti and Vandone, 2019[92]). Access to low- or no-cost bank accounts and formal and regulated credit opportunities are essential to avoid the increased risks and vulnerabilities associated with informal borrowing (Eurofound, 2013[93]). Indeed, governments should create regulatory environments that promote an inclusive financial system, which is amenable to low‑cost banking options such as credit unions, cooperative banks and non‑profit microfinancing (OECD, 2022[68]). For instance, legislative changes in the United Kingdom enabled credit unions and cooperative banks to offer a wide range of products to low‑income people and use dormant assets to support community economic development (United Kingdom Government, 2021[94]; Fair4All Finance, 2022[95]). In the United States, credit unions are now eligible for government grants and can seek regulatory exemptions on lending caps if their customers are predominantly low income.

Beyond regulation, governments can consider various debt relief and settlement policies (including on debts to public authorities) to assist people who are over‑indebted. All OECD countries have debt relief policies – usually requiring people to sell specified assets, remit income above a threshold, or pay instalments for a specific period before the remainder of the debt is waived. Debt relief schemes are typically designed to allow people to have a basic standard of living. This is usually determined with reference to people’s circumstances (such as having children), but in some cases, is based on countries’ wages policy and benefits (Eurofound, 2020[75]). In France, the income threshold is re-calculated on a monthly basis to keep up with changes in individual circumstances, while changes to Sweden’s scheme in 2016 gave more relief to people with children (Eurofound, 2020[75]). The United Kingdom, Ireland and New Zealand have more generous low-fee schemes for low-income people (Ramsay, 2020[96]). For example, the United Kingdom launched a debt respite scheme in 2021 that pauses enforcement action and freezes interest and charges for 60 days (Money and Pensions Service, 2022[97]).

However, debt relief schemes tend to offer only short-lived benefits and do not fundamentally address the underlying drivers of debt problems (Ramsay, 2017[98]). Strict application criteria and high administrative costs represent barriers to access for people on low incomes. In some countries, costs have increased over time – for instance, the 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act increased the financial and time cost of filing in the United States. While in European Union member states, there has been a trend to make debt relief more available and accessible, the extent to which debtors can get a fresh start depends on the types of debts they have accrued. People with debts to public authorities, student loans, tax arrears, fines, healthcare costs or debts resulting from informal borrowing are often excluded from debt relief schemes, even though these represent a large share of low-income individuals’ debts (Eurofound, 2020[75]); see also Box 3.3.

Box 3.3. Debts to public bodies

Debts to public bodies – such as tax arrears, fines, overpayments of benefits, and healthcare costs – are often excluded from debt settlement procedures, even though they are becoming a growing concern (Eurofound, 2020[75]). In the United Kingdom, complaints about debts to public bodies have increased from 21% of all debt problems in 2010-11 to 42% in 2018-19 (Evans, Bennett and Browning, 2020[99]). Indeed, the IMF (2015[100]) has identified the exclusion of public debts from debt relief schemes as a challenge to countries’ personal insolvency regimes because it prevents people from making a fresh start. Further, the exclusion of public debt creates incentives for debtors to pay their public debts instead of those owed to other creditors, which gives creditors a disincentive to agree to restructure debt.

In countries with specific measures for low-income, low-asset debtors, debts related to taxes, benefit overpayments and service charges owed to local authorities can be discharged in certain circumstances. Examples include the No Asset Procedure in New Zealand and the Debt Relief Order in the United Kingdom, while for Debt Relief Notices in Ireland, such debts fall among those which are “excludable” but can be discharged upon agreement with creditors.

While these measures are important, governments should also consider ways to prevent vulnerable households from accruing debts with public bodies and to improve engagement between governments and debtors before commencing enforcement measures. Work on debt management in relation to tax debt has produced cross-country comparisons to highlight best practices and successful strategies, such as using data-mining techniques to identify people at risk of getting into debt with public bodies (OECD, 2019[101]). Other key recommendations involve reforming government affordability assessments, establishing a common framework across different public bodies and implementing changes to benefit deductions, which are often unaffordable and cause substantial hardship. For example, government departments in the United Kingdom now have to take steps to improve debt collection practices, such as by offering tailored payment plans and additional support (Evans, Bennett and Browning, 2020[99]).

While governments should pursue opportunities to improve access to low‑cost credit providers and debt relief policies, they should also consider ways to prevent people from becoming over‑indebted in the first instance. Data mining and predictive models can be used to identify people at risk of getting into debt, direct services to those who are most vulnerable, and develop payment plans (OECD, 2019[101]). For example, artificial intelligence has been shown to accurately identify households at risk of indebtedness across the income distribution (Ferreira et al., 2021[102]). When trained on Portuguese households, artificial intelligence techniques found three main at-risk groups:

those on low incomes who are at risk of over-indebtedness at all times, even during periods of economic stability;

higher-income households with large personal and credit card debts; and

households that are vulnerable to economic crises (generally due to facing heightened risks of unemployment).

These groups have very different characteristics and experience over-indebtedness for different reasons, which indicates the need for a range of financial resilience and social protection policies. Indeed, these findings reiterate the main takeaways from this chapter: a suite of policies is needed to address economic insecurity, as it is a multi-faceted problem. When designing policies, governments should ensure they respond to people’s changing needs and circumstances, as frequent changes make it difficult for people to set themselves up for the future by escaping over-indebtedness, building their financial literacy, smoothing their incomes, and saving. The following Annex provides more detail on the policies reviewed in this chapter for a selection of countries.

References

[32] Ambegaokar, S., Z. Neuberger and D. Rosenbaum (2017), Opportunities to Streamline Enrollment Across Public Benefit Programs, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC.

[80] Angel, S. and K. Heitzmann (2015), “Over-indebtedness in Europe: The relevance of country-level variables for the over-indebtedness of private households”, Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 25/3, pp. 331-351, https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928715588711.

[42] Atalay, K. et al. (2012), Savings and Prize-Linked Savings Accounts, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:iza:izadps:dp6927.

[46] Azzolini, D., S. McKernan and K. Martinchek (2020), Households with Low Incomes Can Save: Evidence and Lessons from Matched Savings Programs in the US and Italy, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103290/households-with-low-incomes-can-save-evidence-and-lessons-from-matched-savings-programs-in-the-us-and-italy.pdf.

[13] Barrage, L. et al. (2019), “The impact of bill receipt timing among low-income households: New evidence from administrative electricity bill data”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, https://www.nber.org/programs-projects/projects-and-centers/retirement-and-disability-research-center/center-papers/nb19-09.

[17] Bellisle, D. and D. Marzahl (2015), Restructuring the EITC: a credit for the modern worker, Center for Economic Progress, Washington, D.C.

[87] Bhutta, N., J. Goldin and T. Homonoff (2016), “Consumer Borrowing after Payday Loan Bans”, Journal of Law and Economics, University of Chicago Press, Vol. 59/1, pp. 225-259, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/686033.

[54] Blanc, J. et al. (2015), Household Saving Behaviour and Credit Constraints in the Euro Area, European Central Bank.

[39] Breunig, R. and K. Sobeck (2020), The Impact of Government Funded Retirement Contributions (Matching) on the Retirement Savings Behaviour of Low and Middle Income Individuals, https://taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/uploads/taxstudies_crawford_anu_edu_au/2021-08/retirement_contributions_final_report_2020.pdf.

[38] Bufe, S. et al. (2022), “Financial shocks and financial well-being: What builds resiliency in lower-income households?”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 161, pp. 379-407, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-021-02828-y.

[73] Burke, J. and A. Hung (2015), Financial Advice Markets: A Cross-Country Comparison, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1269.html.

[35] Bynner, J. and W. Paxton (2001), The Asset-Effect, IPPR, London.

[28] Carter, C., M. Bédard and P. Bista (2013), Comparative Review of Unemployment and Employment Insurance Experiences in Asia and Worldwide. Promoting and Building Unemployment Insurance and Employment Services in ASEAN, ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_229985.pdf.

[9] Christl, M. et al. (2022), The Role of Short-Time Work and Discretionary Policy Measures in Mitigating the Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis in Germany, International Tax and Public Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-022-09738-w.

[56] Collins, J. (2012), “Financial advice: A substitute for financial literacy?”, Financial Services Review, Vol. 21/4, pp. 307-322, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2046227.

[24] Cooper, K. and J. Hills (2021), The Conservative Governments’ Record on Social Security: Policies, Spending and Outcomes, May 2015 to pre-COVID 2020, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (LSE), https://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/CASE/_new/publications/abstract/?index=7765.

[89] Ellison, A. and R. Forster (2006), The Impact of Interest Rate Ceilings: The Evidence from International Experience and the Implications for Regulation and Consumer Protection in the Credit Market in Australia, United Kingdom, Policis Publications.

[27] Employment and Social Development Canada (2022), EI Regular Benefits, Government of Canada, https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/ei/ei-regular-benefit/after-applying.html.

[75] Eurofound (2020), Addressing household over-indebtedness, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[29] Eurofound (2015), Access to Social Benefits: Reducing Non-Take-Up, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[93] Eurofound (2013), Household Over-Indebtedness in the EU: The Role of Informal Debts, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[103] European Banking Authority (2021), Guidelines on Legislative and Non-Legislative Moratoria on Loan Repayments Applied in the Light of the COVID-19 Crisis, https://www.eba.europa.eu/regulation-and-policy/credit-risk/guidelines-legislative-and-non-legislative-moratoria-loan-repayments-applied-light-covid-19-crisis.

[10] European Training Foundation (2021), Mapping Innovative Practices in the Field of Active Labour Market Policies During the Covid-19 Crisis, European Union, Turin.

[53] European Union/OECD (2022), Financial Competence Framework for Adults in the European Union, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/220111-financial-competence-framework-adults_en.pdf.

[99] Evans, J., O. Bennett and S. Browning (2020), Debts to Public Bodies: Are Government Debt Collection Practices Outdated?, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9007/.

[41] Fadejeva, L. and O. Tkacevs (2022), “The effectiveness of tax incentives to encourage private savings”, Baltic Journal of Economics, Vol. 22/2, pp. 110-125, https://doi.org/10.1080/1406099X.2022.2109555.

[95] Fair4All Finance (2022), About Us, https://fair4allfinance.org.uk/about-fair4all/ (accessed on 2 September 2022).

[88] Ferrari, A., O. Masetti and J. Ren (2018), Interest Rate Caps: The Theory and The Practice, World Bank, Washington.

[102] Ferreira, M. et al. (2021), “Using artificial intelligence to overcome over-indebtedness and fight poverty”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 131, pp. 411-425, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.035.

[92] Ferretti, F. and D. Vandone (2019), “Introduction”, in Ferretti, F. and D. Vandone (eds.), Personal Debt in Europe: The EU Financial Market and Consumer Insolvency, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[72] Financial Conduct Authority (2020), Evaluation of the Impact of the Retail Distribution Review and the Financial Advice Market Review, Financial Conduct Authority, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/corporate/evaluation-of-the-impact-of-the-rdr-and-famr.pdf.

[91] Financial Conduct Authority (2017), Price Cap Research Main Report, Financial Conduct Authority, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research/price-cap-research.pdf.

[81] Fligstein, N. and A. Goldstein (2015), “The emergence of a finance culture in American households, 1989–2007”, Socio-Economic Review, Vol. 13/3, pp. 575-601, https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/MWU035.

[52] French, D. and D. McKillop (2016), “Financial literacy and over-indebtedness in low-income households”, International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 48, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IRFA.2016.08.004.

[86] Friedline, T. and N. Kepple (2017), “Does community access to alternative financial services relate to individuals’ use of these services? Beyond individual explanations”, Journal of Consumer Policy, Vol. 40, pp. 51-79.

[100] Fund, I. (2015), Spain’s Insolvency Regime: Reforms and Impact, IMF, Washington.

[63] Goyal, K. and S. Kumar (2020), “Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 45/1, pp. 80-105, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12605.

[19] Greenlee, A. et al. (2021), “Financial instability in the earned income tax credit program: Can advanced periodic payments ameliorate systemic stressors?”, Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 57/6, pp. 1626-1655, https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087420921527.

[26] Greig, F. et al. (2022), Lessons Learned from the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Program During COVID-19, JPMorgan Chase Institute, Washington, D.C.

[76] Hartfree, Y. and S. Collard (2014), Poverty, Debt and Credit: An Expert-Led Review. Final Report, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

[45] Harvey, P. et al. (2007), Final Evaluation of the Saving Gateway 2 Pilot: Main Report, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/savings_gateway_evaluation_report.pdf.

[6] Hemmerlé, Y. et al. (2023), “Aiming better: Government support for households and firms during the energy crisis”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 32, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/839e3ae1-en.

[49] HM Treasury (2023), Help to Save Reform: Consultation, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1153552/April_2023_HMT_Template_-_Help_to_Save_Consultation_Publication_2.pdf.

[85] Hogan Lovells (2021), COVID-19: Summary of National Payment Moratoria Measures in Europe, https://www.engage.hoganlovells.com/knowledgeservices/news/covid-19-summary-of-national-payment-moratoria-measures-in-europe.

[30] Immervoll, H. and M. Pearson (2009), “A Good Time for Making Work Pay? Taking Stock of In-Work Benefits and Related Measures across the OECD”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 81, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/225442803245.

[82] Jappelli, T., M. Pagano and M. Di Maggio (2013), “Households’ indebtedness and financial fragility”, Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 1, pp. 23-46.

[61] Kaiser, T. and L. Menkhoff (2017), “Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when?”, The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 31/3, pp. 611-630, https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhx018.

[43] Kearney, M. et al. (2011), “Making savers winners: An overview of prize-linked saving products”, in O.S., M. and L. A. (eds.), Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

[33] Kesselman, J. and G. Petit (2020), Earnings Supplementation for British Columbia: Pros, Cons, and Structure, University Library of Munich, Germany.

[8] Kopp, D. and M. Siegenthaler (2021), “Short-Time work and unemployment in and after the Great Recession”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 19/4, pp. 2283-2321, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvab003.

[18] Kramer, K. et al. (2019), “Periodic Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Payment, Financial Stress and Wellbeing: A Longitudinal Study”, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Vol. 40, pp. 511-523.

[74] Krishnamurti, C. et al. (2022), The Impact of Cost and Access to Financial Advice for Lower Socio-economic Consumer Groups, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11296.46089.

[71] Lu, F. and H. Lim (2022), “Cognitive abilities and seeking financial advice: Differences in advice sources”, Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Vol. 33/1, pp. 97-114, https://doi.org/10.1891/JFCP.33.1.

[70] Lusardi, A., P. Michaud and O. Mitchell (2017), “Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality”, Journal of Political Economy, doi: 10.1086/690950, pp. 431-477, https://doi.org/10.1086/690950.

[62] Lusardi, A. and O. Mitchell (2014), “The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 52/1, pp. 5-44, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.52.1.5.

[16] Maag, E., W. Congdon and E. Yau (2021), The Earned Income Tax Credit: Program Outcomes, Payment Timing, and Next Steps for Research, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US. Department of Health and Human Services.

[90] Madeira, C. (2019), “The impact of interest rate ceilings on households’ credit access: Evidence from a 2013 Chilean legislation”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 106, pp. 166-179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.06.011.

[48] Madrian, B. (2012), Matching Contributions and Savings Outcomes: A Behavioral Economics Perspective, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w18220/w18220.pdf.

[58] McKnight, A. (2018), Financial Resilience Among EU Households: New Estimates by Household Characteristics and a Review of Policy Options, https://doi.org/10.2767/472697.

[37] McKnight, A. (2011), Estimates of the Asset-Effect: The Search for a Causal Effect of Assets on Adult Health and Employment Outcomes, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science.

[50] McKnight, A. and M. Rucci (2020), “The financial resilience of households: 22 country study with new estimates, breakdowns by household characteristics and a review of policy options”, CASE Papers, No. 219, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, LSE, https://ideas.repec.org/p/cep/sticas/-219.html.

[31] Millar, J. and P. Whiteford (2020), “Timing it right or timing it wrong: How should income-tested benefits deal with changes in circumstances?”, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, Vol. 28/1, pp. 3-20, https://doi.org/10.1332/175982719X15723525915871.

[60] Miller, M. et al. (2015), “Can you help someone become financially capable? A meta-analysis of the literature”, The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 30/2, pp. 220-246, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkv009.

[97] Money and Pensions Service (2022), Breathing Space, https://moneyandpensionsservice.org.uk/our-debt-work/breathing-space/#:~:text=Process%20improvement-,What%20is%20Breathing%20Space%3F,and%20charges%20on%20their%20debts. (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[79] NAV (2023), Need Financial Advice and Debt Counselling?, https://www.nav.no/okonomi-gjeld/en (accessed on 31 July 2023).

[25] O’Campo, P. et al. (2015), “Social welfare matters: a realist review of when, how, and why unemployment insurance impacts poverty and health”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 132, pp. 88-94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.025.

[3] OECD (2023), Income Support for Jobseekers: Trade-Offs and Current Reforms, https://www.oecd.org/employment/Income-support-for-jobseekers-Trade-offs-and-current-reforms.pdf.

[68] OECD (2022), Draft Revised Recommendation of the Council on High-level Principles on Financial Consumer Protection, https://one.oecd.org/document/C(2022)195/en/pdf.

[65] OECD (2022), Evaluation of National Strategies for Financial Literacy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education/Evaluations-of-National-Strategies-for-Financial-Education.pdf.

[7] OECD (2022), Minimum Wages in Times of Rising Inflation, https://www.oecd.org/employment/Minimum-wages-in-times-of-rising-inflation.pdf.

[47] OECD (2022), OECD Pensions Outlook: 2022, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/20c7f443-en.

[59] OECD (2022), “Policy handbook on financial education in the workplace”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 07, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b211112e-en.

[83] OECD (2021), “Inequalities in household wealth and financial insecurity of households”, OECD Policy Insights on Well-being, Inclusion and Equal Opportunity, No. 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b60226a0-en.

[55] OECD (2020), OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy, https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/oecd-infe-2020-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy.pdf.

[51] OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on Financial Literacy, OECD/LEGAL/0461, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0461.

[34] OECD (2019), Financial Incentives for Funded Private Pension Plans: OECD Country Profiles, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/Financial-Incentives-for-Funded-Pension-Plans-in-OECD-Countries-2019.pdf.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

[101] OECD (2019), Successful Tax Debt Management: Measuring Maturity and Supporting Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/successful-tax-debt-management-measuring-maturity-and-supporting-change.pdf.

[23] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[40] OECD (2018), Taxation of Household Savings, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264289536-en.

[64] OECD (2017), G20/OECD INFE Report on Adult Financial Literacy in G20 Countries, https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/G20-OECD-INFE-report-adult-financial-literacy-in-G20-countries.pdf.

[57] OECD (2015), National Strategies for Financial Education, OECD/INFE Policy Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[66] OECD (2013), Advancing National Strategies for Financial Education, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education/advancing-national-strategies-for-financial-education.htm.

[67] OECD (2012), OECD/INFE High-level Principles on National Strategies for Financial Education, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/OECD-INFE-Principles-National-Strategies-Financial-Education.pdf.

[77] Orton, M. (2010), The Long-Term Impact of Debt Advice on Low Income Households: The Year 3 Report, Warwick Institute for Employment Research and Friends Provident Foundation, Warwick.

[22] Parolin, Z. et al. (2021), The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship, National Bureau of Economic Research.

[20] Perez-Lopez, D. (2021), Economic Hardship Declined in Households with Children as Child Tax Credit Payments Arrived, United States Census Bureau.

[84] Ptak, A. (2022), Polish Parliament Approves Law to Suspend Mortgage Repayments, https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/07/08/polish-parliament-approves-law-to-suspend-mortgage-repayments/ (accessed on 28 August 2023).

[96] Ramsay, I. (2020), “The new poor person’s bankruptcy: Comparative perspectives”, International Insolvency Review, Vol. 29/S1, pp. S4-S24, https://doi.org/10.1002/iir.1357.

[98] Ramsay, I. (2017), “Towards an international paradigm of personal insolvency law? A critical view”, QUT Law Review, Vol. 17/1, pp. 15-39, https://doi.org/10.5204/qutlr.v17i1.713.

[5] Rohde, N., K. Tang and D. Prasada Rao (2014), “Distributional characteristics of income insecurity in the US, Germany, and Britain”, Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 60, pp. S159-176, https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12089.

[21] Roll, S. et al. (2021), How are American Families Using Their Child Tax Credit Payments? Evidence from Census data, Social Policy Institute Research.

[4] Salgado, M. et al. (2014), “Welfare compensation for unemployment in the Great Recession”, Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 60, pp. S177-204, https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12035.

[44] Schreiner, M. (2004), Match Rates, Individual Development Accounts, and Saving by the Poor, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1278&context=csd_research.

[12] Scottish Government (2021), Evaluation of Universal Credit Scottish Choices, Equality and Welfare, Scottish Government.

[14] Seligman, H. et al. (2014), “Exhaustion of food budgets at month’s end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia”, Health Affairs, Vol. 33/1, pp. 116-123, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0096.

[36] Sherraden, M. (2009), “Individual development accounts and asset-building policy: Lessons and directions”, in Blank, R. and M. Barr (eds.), Insufficient Funds: Savings, Assets, Credit and Banking among Low-Income Households, Russel Sage Foundation, New York.

[1] Sologon, D. and C. O’Donoghue (2014), “Shaping earnings insecurity: Labor market policy and institutional factors”, Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 60, pp. S205-232, https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12105.

[78] Stamp, S. (2012), “The impact of debt advice as a response to financial difficulties in Ireland”, Social Policy and Society, Vol. 11/1, pp. 93-104, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746411000443.

[11] Summers, K. and D. Young (2020), “Universal simplicity? The alleged simplicity of Universal Credit from administrative and claimant perspectives”, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, Vol. 28/2, pp. 169-186, https://doi.org/10.1332/175982720X15791324318339.

[94] United Kingdom Government (2021), Factsheet Two: Policy Context and Background, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dormant-assets-bill-factsheets/factsheet-two-policy-context-and-background (accessed on 2 September 2022).

[69] von Gaudecker, H. (2015), “How does household portfolio diversification vary with financial literacy and financial advice?”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 70/2, pp. 489-507, https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12231.

[15] Zhang, G. (2021), “The effect of unemployment benefit pay frequency on UI claimants’ job search behaviors”, Saint Louis University Sinquefield Center for Applied Economic Research, https://www.slu.edu/research/sinquefield-center-for-applied-economic-research/working-paper-21-03.pdf.

Annex 3.A. Review of policies and interventions targeting economic insecurity in selected OECD countries

Annex Table 3.A.1. Timeliness of unemployment benefits, tax credits and other national social benefits

|

France |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

Greece |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

Latvia |

|

|

Spain |

|

|

Sweden |

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

Annex Table 3.A.2. Savings schemes and other efforts to support households’ financial capacity

|

France |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

Greece |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

Latvia |

|

|

Spain |

|

|

Sweden |

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

United States |

|

Annex Table 3.A.3. Improving financial literacy and access to high-quality financial advice

|

France |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

Greece |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

Latvia |

|

|

Spain |

|

|

Sweden |

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

United States |

|

Annex Table 3.A.4. Implementing protective and rehabilitating measures

|

France |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

Greece |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

Latvia |

|

|

Spain |

|

|

Sweden |

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

United States |

|

Notes

← 1. Some benefits play a role in smoothing income instability, but their effects cannot be reliably estimated, because it is difficult to attribute to changes in an individual’s employment intensity (in the case of disability benefits) or they are paid at the level of the household rather than the individual (in the case of child allowances). See Chapter 1 for more information on the allocation of social benefits to individual income.

← 2. For example, in the United States, Norway, Israel and Canada, social protection is primarily an insurance scheme that people pay into while they are employed and draw down on when they are unemployed. The amount they draw down is usually based on the amount they contributed. In contrast, in Australia people do not contribute to an unemployment insurance scheme, but receive an allowance for as long as they are unemployed so long as they meet means and activity tests. In addition, some countries have guaranteed minimum incomes for people who are unable to work and tax credits that supplement employment earnings. However, there are differences in the purposes of tax credits. In anglophone countries, tax credits are primarily aimed at poverty alleviaiton, while in continental European countries, they have a stronger employment focus.

← 3. The share of over-indebted and/or financially fragile middle-income households increased in previous economic crises. During the Global Financial Crisis, 2.6 million of the roughly 10 million households in Portugal were over-indebted, and financial fragility dramatically increased in Greece, Ireland and Spain (Ferreira et al., 2021[102]).

← 4. In addition, the European Banking Authority (2021[103]) published guidelines on legislative and non-legislative loan repayment moratoria to respond to the COVID-19 crisis.