This chapter examines recent progress and remaining challenges in trade facilitation across Central Asia as governments look to reduce trade costs and promote regional and international integration, contributing to economic growth and stability in the region. It evaluates advances in trade facilitation performance by country over time and compares them to international peers. It then highlights the areas of improvement and identifies specific areas where progress is needed, before providing recommendations centred on inclusive feedback mechanisms and trade community involvement, regional standardisation and harmonisation, and cross-border co-ordination, co-operation, and collaboration.

Trade Facilitation in Central Asia

2. Regional overview

Abstract

Central Asia has made progress in trade facilitation in recent years, but the region remains below its potential

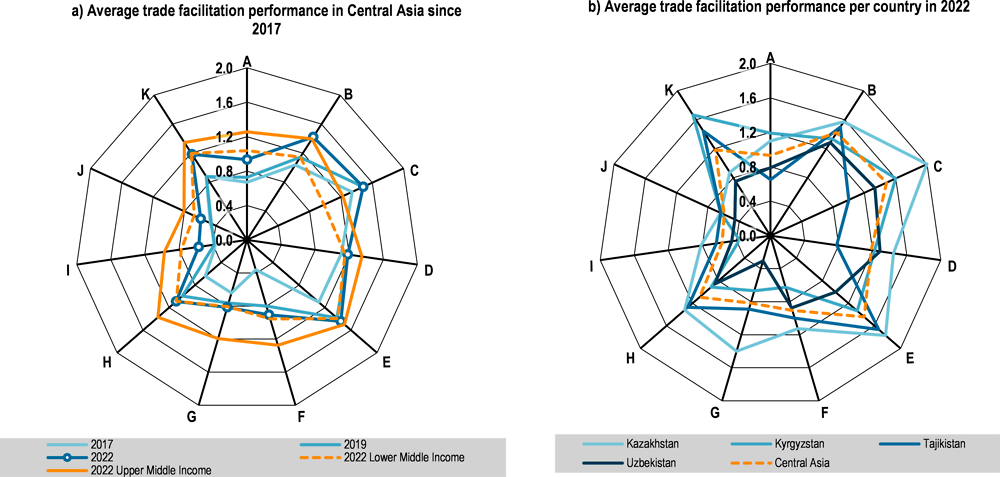

The governments of Central Asia have reaped the rewards of trade facilitation reforms, as TFI performance has improved significantly for all economies in 20221 (Figure 2.1). Uzbekistan achieved the largest relative performance improvement compared to the latest OECD TFI update in 2019, with the average TFI score rising by 0.141 (19.8%). However, Kazakhstan leads Central Asia in the absolute performance increase: 0.166 (15.0%) and the highest average TFI score. Across the areas covered by the TFIs, governance and impartiality, and the involvement of the trade community, are the greatest elements of improvement since 2019, followed by information availability, internal and external border agency co-operation, and simplification and harmonisation of trade-related documents.

Figure 2.1. Central Asia’s trade facilitation performance since 2017

Note: 2 is the maximum performance to be achieved. Central Asia includes information for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Legend: A - Information availability, B - Involvement of the trade community, C - Advance rulings, D - Appeal procedures, E - Fees and charges, F - Documents, G - Automation, H - Procedures, I - Internal border agency co-operation, J - External border agency co-operation, K - Governance and impartiality.

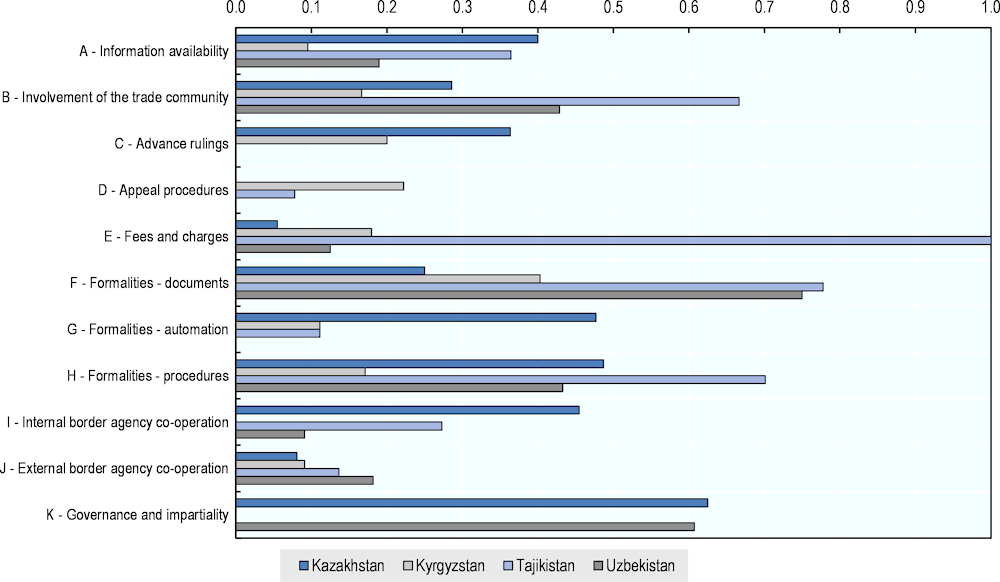

There is disparity in performance improvement on certain dimensions in recent years, contributing to heterogeneity (Figure 2.2). For instance, Kazakhstan’s strong performance since 2017 in automation of procedures compared to little progress in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and no progress in Uzbekistan resulted in large disparities in scores on this dimension (Figure 2.1). The strides made by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan on governance and impartiality since 2019 bring their performance closer to that of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan on this dimension, though further efforts are warranted. All countries can benefit from stronger international collaboration to co-ordinate their initiatives and facilitate trade in a collaborative manner, though the countries in Central Asia especially stand to benefit due to their geographic constraints.

Figure 2.2. TFI performance improvement per country and dimension in 2022 compared to 2017

Note: the graph depicts the absolute change in TFI score in 2022 compared to 2017: the higher the score, the greater the performance increase.

Source: OECD TFIs database, 2022.

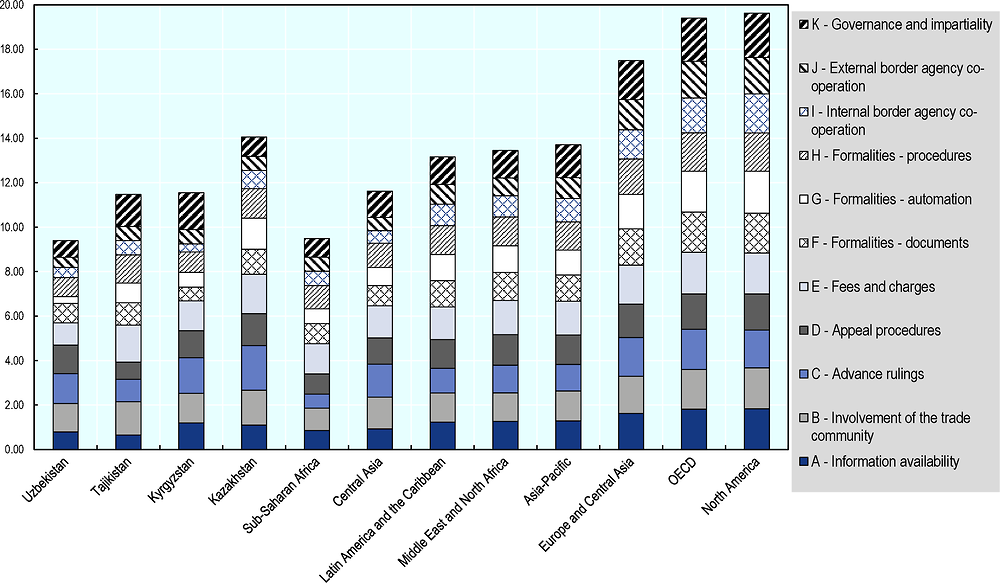

Central Asia’s performance in trade facilitation falls behind most of the regions covered by the dataset. The relative gap with other regions’ performance is the most striking in advance rulings, appeal procedures, automation of border processes, domestic border agency co-operation, and cross-border agency co-operation (Figure 2.3). For instance, public authorities rarely conduct reviews to simplify trade-related documents, while the time burden of completing complex documentation and the need to send original copies hamper trade activity for SMEs. This is exacerbated by insufficiently adequate computer systems for border management and limited implementation of digital certificates and signatures and electronic payment systems. Domestic and cross-border agency co-operation are two other dimensions which are challenging in terms of progress and implementation, showcasing the need for countries to co-operate at the regional level.

Figure 2.3. Trade facilitation performance in Central Asia compared to other regions, 2022

Note: 2 is the maximum performance to be achieved. Central Asia includes information for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Source: OECD TFIs database, 2022.

Though heterogeneity in trade facilitation performance across TFI dimensions is high within Central Asia, it is both an incentive for countries to improve and a potential area of collaboration for regional integration. As all five countries are now working with the OECD on trade facilitation, governments have shown their desire to improve their overall performance. More significantly, the indicators show which trade facilitation dimensions to prioritise based on regional or income-level groupings to improve economies’ competitiveness.

Poor agency co-operation and limited information availability pose significant barriers

Challenge 2.1: despite recent improvements, trade-related legislation is often ambiguous and inconsistent, while information is not sufficiently well disseminated

Government bodies in Central Asia have increasingly incorporated summary guides to key import and export processes in customs websites or recently established trade information portals, while required trade-related documentation is also gradually made available to download. For instance, Kazakhstan has enhanced information on trade agreements, appeal procedures, and enquiry points, while also publishing user manuals for new systems. Uzbekistan has increased the quantity and user-friendliness of information regarding duties, trade procedures, trade-related legislation, and documentary requirements. It has also provided user manuals for new border systems and better access to information on trade agreements. Tajikistan has improved information provision on export/import procedures, trade documents, enquiry points, and advance publication on regulations, with a focus on user manuals for new border systems.

Governments have been developing feedback mechanisms for customs and other border agencies on trade-related matters, as well as in publishing legislation in advance of its entry into force. For instance, Kyrgyzstan has focused on online feedback, increasing publication-to-enforcement time, and improving trade procedure information through a newly modernised Single Window Information System (SWIS). In general, each government in Central Asia has made strides in developing its own Single Window. Notably, the region has started to make progress in developing a regional platform through the launch of the Info Trade Central Asia Gateway in 2023 (Box 2.1). The International Trade Centre has developed the Gateway as part of its four-year Ready4Trade in Central Asia project. The Ready4Trade project aims to help develop intra-regional and international trade by promoting soft measures on trade facilitation, administrative management, training, and support to exporting SMEs. The project also aims to enhance the transparency of cross-border requirements, remove regulatory and procedural barriers, and strengthen businesses’ ability to comply with trade formalities and standards.

Box 2.1. The Info Trade Central Asia Gateway

Developed by the International Trade Centre (ITC) and funded by the European Union’s Ready4Trade Central Asia (R4TCA) project, the Info Trade Central Asia Gateway (Central Asia Gateway) aims to provide greater transparency in cross-border trade and reduce regulatory and procedural barriers.

Launched in 2023, the Central Asia Gateway provides direct access to step-by-step guides on licenses, pre-clearance permits and clearance formalities for most traded goods within, to and from Central Asia. The Central Asia Gateway automatically extracts information from national trade facilitation portals in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, that presents national export, import and transit formalities step-by-step by mode of transport by road, rail, sea, or air. From each step, the Central Asia Gateway informs users on where to go, whom to meet, what documents to bring, what forms to fill, what costs to pay, what law justifies the step, and where to complain in case of problems.

ITC has designed free courses that it provides for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in each participating country to encourage regional and international trade. The courses vary from global trade rules to export procedures, transit routes, quality and compliance standards, and EU market standards.

The Central Asia Gateway also links to partner helpdesks (i.e., European Union, United States, China, ASEAN) as well as the trade capacity-building and knowledge training websites of each of the five countries, thereby bringing relevant trade information into a single point of contact.

Guidelines and procedures have been established to govern public consultation processes, with a growing emphasis on involving the trade community in the design of border-related policies. Increasingly, drafts of rules are made available prior to their implementation, allowing for feedback and comments. Governments have developed transparent frameworks for notice-and-comment procedures, ensuring accountability for public comments on draft regulations. Furthermore, there have been notable efforts to expand the range of stakeholders engaged in consultation processes, promoting inclusivity and transparency.

Though significant progress has been achieved with respect to the availability of trade-related information, further efforts are needed to improve regional performance. Specific measures relate to the availability of comprehensive, up-to-date, and user-friendly information on penalty provisions, appeal procedures, judicial decisions, and trade agreements. Governments can consider additional efforts in making up-to-date trade-related legislation on all sectors available online. In particular, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan could consider harmonising the advance publication of trade-related regulations before entry into force, which today appears to cover only selected trade-related procedures.

Challenge 2.2: digitalisation and automation of trade-related procedures is lagging

Automation remains one of the most challenging areas for Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, notwithstanding significant progress across the region. All governments have implemented systems supporting Electronic Data Interchange, while public agencies are continuously incorporating electronic payment of duties, taxes, fees, and charges collected upon importation, exportation, and transit. Governments are increasingly making pre-arrival processing available to traders through the possibility of lodging documents in advance in electronic format, while they have made progress in establishing national online trade Single Windows. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have improved pre-arrival processing, treatment of perishable goods, and the harmonisation of trade-related documents. Kazakhstan has simplified documentation requirements by accepting copies of trade-related documents, reducing their number and complexity. In 2021, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan opened green lanes for transit using the TIR Carnet road permit system (Silk Road Briefing, 2022[3]).

Central Asian governments are increasingly participating in international agreements facilitating transit trade and and implementing customs automation tools. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have ratified the TIR Convention (Transports Internationaux Routiers), which enables the simplification of customs procedures in transit countries for road cargo transport, while Turkmenistan is in the process of implementing it. The UNCTAD Automated System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) is an integrated customs management system for international trade and transport operations that aims to accelerate customs clearance via computerisation and simplified procedures. In 2023, ASYCUDA systems are running or being implemented in 102 countries and territories, including Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have expressed their willingness to explore ASYCUDA adoption, but have not yet implemented the system (UNCTAD, 2019[4]; UNCTAD, 2022[5]; Central Asia News, 2021[6]; Embassy of Uzbekistan, 2020[7]).

Since the entry into force of the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have improved their national trade Single Windows. They have operationalised the customs administration risk management system and improved the treatment of perishable goods, notably in terms of inspections at the border. As its WTO accession process is still ongoing, Uzbekistan has not yet formally ratified the WTO FTA, but it has focused on the establishment of a trade Single Window, post-clearance audits, and the treatment of perishable goods. Kazakhstan and other countries have taken important steps towards implementing an Authorised Operators (AOs) programme, while pre-shipment inspection certificates are no longer required on most commodities for any customs-related matter in most countries. Moreover, average release times are increasingly being published in a consistent manner for major customs offices, though the authorities are not yet conducting Time Release Studies across ports of entry to support this implementation.

Challenge 2.3: all countries face deficiencies in domestic and international border agency co-operation

Central Asian governments face challenges in domestic and cross-border agency co-operation, with these two areas recording the lowest average TFI performance for the region. Nevertheless, there are heightened levels of domestic co-ordination and harmonisation of data requirements and documentary controls among trade agencies, notably through institutionalised mechanisms to support inter-agency co-ordination. For instance, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have established inter-agency mechanisms to support domestic border agency co-operation while Uzbekistan has also strengthened its own mechanisms, leading to co-ordination of data requirements, documentary controls, and inspections. All governments have established National Committees for Trade Facilitation, which together with well-functioning mechanisms for consultations with traders, are contributing to better public-private co-operation for trade facilitation. Increased availability of information in real time (i.e., sharing results of inspections and controls) among domestic agencies enhances day-to-day co-operation between border agencies.

Operationalising co-operation between border agencies of Central Asian countries as well as their co-operation with neighbouring economies and trading partners has improved external border agency co-operation. Regular meetings, co-ordination of procedures, and shared infrastructure contribute to improved co-operation. Governments have increased their readiness in advancing mechanisms for cross-border agency co-operation, particularly in co-ordinating data requirements and documentary controls as well as aligning border formalities, working days, and national legislation. Nevertheless, TFI performance on this dimension across Central Asia is poor.

Central Asia should improve the availability of trade information, simplify processes, and enhance border agency co-operation

Recommendation 2.1: Governments can prioritise trade community feedback in improving information provision and streamlining procedures

Central Asian economies should intensify private sector awareness-raising, capacity-building, and consultation. They could exploit the progress achieved in consultations with stakeholders to introduce more dissemination campaigns, training, and private sector feedback focused on SMEs. This could help inform firms about the trade facilitation tools available, such as Single Windows, pre-arrival processing, advance rulings, Authorised Operators (AOs), and post-clearance audits. As the advance rulings systems remain in the early stages of implementation across most of the region, border authorities should prioritise implementing the system and support its wider use by traders. The efficiency of advance rulings issuance will become easier to assess when more requests from traders will be received on advance rulings and more advance rulings will be issued to traders in response. Trade-related public consultations could be targeted towards the availability of notice-and-comment procedures and on the processes explaining how public comments have been considered. This highlights the importance of increasing work with the private sector, including through training and business engagement programmes to improve the trading community’s knowledge of border-related requirements, the ability to input data without errors, and the importance of pre-arrival declarations.

Governments can improve trade-related information and accessibility. The relevant authorities should increase the user-friendliness of customs websites or trade information portals, the timeliness of enquiry points, and the transparency of policymaking in trade-related regulations. This would enhance awareness, increase uptake, and better involve the trade community across Central Asia. For instance, countries should consider collaborating within the Ready4Trade project framework to improve their Single Windows and facilitate information access and exchange. Experience in other regions points to the effectiveness – and challenges – of developing and implementing a regional Single Window, which can be considered as the next step for authorities in the region beyond the Info Trade Central Asia Gateway (see Box 2.2).

Countries can improve the overall efficiency of appeal procedures. In particular, governments can make continued progress in information availability, as more comprehensive and user-friendly information made available to traders and other stakeholders can help avoid administrative or judicial appeals.

The trade facilitation policy environment can be improved by streamlining fees across border agencies, centralising them in a common database, and improving information availability. Fees are also charged for answering enquiries and providing required forms and documents, while in some economies specific fees are charged during normal working hours. These could be further reduced and streamlined, while additional efforts are needed to reduce the overall variety of fees and charges applied.

Governments can build upon the information published online and on Single Windows to set up a central database where businesses can access data on all applicable fees. Economies in the region that made important progress in the streamlining of fees and charges, such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, could provide useful models for their neighbours.

Box 2.2. Setting the basis for a regional Single Window: The experience of ASEAN

In 2005, ASEAN agreed to implement the ASEAN Single Window (ASW) to fully integrate the National Single Windows (NSWs) of individual ASEAN member economies, drawing on internationally accepted standards, procedures, documents, technical details, and formalities.

The ASW involves direct exchanges of data between ASEAN Member States which are then synchronised across the region. This allows data and information to be submitted only once and avoids duplicative decision-making for Customs. The ASW is composed of three networks: the regional (or central) domain, which allows communication among NSWs, supports the secure electronic transfer of information and tracks transaction statistics; the national domain, which represents the network infrastructure hosted by each individual economy; and the external networks used by the trading community, which only have direct access to national domains to preserve data confidentiality. While data is directly exchanged between NSWs, it is not retained centrally.

The ASW is overseen by the ASW Steering Committee (ASWSC), which reports directly to ASEAN Directors General of Customs and ASEAN Senior Officials. The ASWSC is assisted by technical (TWG) and legal (LWG) working groups. These groups consulted the private sector on the development of the ASW and on the priorities for data exchange and studied options for the governance, business model and financial sustainability of the ASW. The TWG and LWG also undertook awareness raising and capacity building at the regional level on business process analysis, data harmonisation and legal aspects, and at the national level on the use of software applications.

In 2011, a pilot evaluation and cost-benefit analysis was launched with seven ASEAN economies. It tested the technical architecture and sought to streamline and standardise data, explore efficient business processes, strengthen partnerships with stakeholders and raise public awareness. The ASW web portal was launched in 2013 upon successful completion of the pilot, which had seen over a million messages exchanged. A Legal Framework agreement regulating the cross-border exchange of electronic data was concluded in 2015.

Countries focused the first efforts on integrating the ASEAN preferential certificate of origin, which was important to the private sector, raised no confidentiality issues, and for which a standard operating procedure was already in place. Countries initiated bilateral pilots on certificate exchanges before a broader pilot involved more ASEAN economies. The objective remains to incorporate commercial and transport documents for goods, as well as documents required for the release and clearance of goods. It will also progressively analyse other government-to-government data, such as phytosanitary, veterinary and health certificates, as well as business-to-business data, such as bills of lading, air waybills, packing lists and invoices with a view to their inclusion.

Benefits of the ASW include improved risk management and compliance, enhanced track-and-trace capabilities, smoother pre-arrival clearance and better supply chain integration. The creation of the ASW has also generated significant impetus for the creation and improvement of NSWs. It has also spurred efforts to harmonise data and procedures among members, including beyond those required for the ASW, thereby supporting broader policy harmonisation efforts.

Since February 2022, Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand have exchanged the ACDD, while the remaining AMS joined in 2022. Following these successes, the exchange of additional electronic trade documents on the electronic Phytosanitary (e-Phyto) certificate and Animal Health (e-AH) certificate is under discussion.

Source: OECD TFIs repository.

Recommendation 2.2: Digitalising and harmonising regional standards and documentation requirements could reduce the time and cost of cross-border trade

While the analysis highlights progress in reducing the number of documents requested, additional work could focus on streamlining documentation requirements and further develop electronic clearance procedures. Customs documentation and procedures, including clearance and inspections, negatively affect the internationalisation of firms, reducing the development of intra-regional trade (López González and Sorescu, 2019[8]). Additional documentation-related efforts could focus on increasing the proportion of supporting documents for import, export and transit formalities for which copies are accepted and aligning inconsistent documentation requirements between different entry/exit ports.

Continued progress in developing automation tools has the potential to support efforts to streamline documentary requirements and border processes, as well as domestic border agency co-operation. Further advancing the gradual implementation of electronic exchange of data could accelerate and simplify border procedures. In general, digitalisation goes in parallel with the automation of procedures, and the standardisation of customs documents that could be centralised on a single digital platform. In the short-to-medium term, governments could focus on the clearance of export and import declarations electronically and on increasing the share of procedures that allow for electronic processing, though this needs to be backed by appropriate IT equipment and systems. The coexistence of different e-customs systems across the region – mainly the e-TIR and the UN ASYCUDA systems – challenges a straightforward implementation of electronic exchange of data between user countries (OECD, forthcoming[9]). In the longer term, the economies of Central Asia could work towards the full implementation of an electronic payment system for duties, taxes, fees, and charges collected upon importation, exportation, and transit.

Further efforts are warranted to improve operational border practices. These should include a greater number of trade transactions that can receive pre-arrival processing and separation of release from clearance. Particular attention could be targeted towards improving the efficiency of border processes that concern perishable goods, in terms of streamlining inspections and increasing the share of transactions covered by separation of release from clearance. OECD private sector survey respondents underlined the need for simplified and standardised documents and procedures, as well as a streamlining of border regulations for greater consistency, to eventually reduce border crossing times and traffic congestion (OECD, forthcoming[9]).

Policies and guidelines need to be improved to ensure the conduct of post-clearance audits and implementation of AO programmes in a transparent and risk-based manner. Additional initiatives could target the increase in the coverage of AO programmes (i.e., in terms of the share of traders covered, SMEs included, and trade transactions covered). Conducting Time Release Studies could further highlight ways forward for expanding the reach of AO programmes and help promote the programme with stakeholders.

Though customs agencies in the region are gradually employing more modern risk management techniques, they could expand the use of automated systems in particular. These have the potential to be adopted more broadly by other border agencies in addition to customs authorities and could be co-ordinated centrally. This area could also be supported by enhanced regional border agency co-ordination (Box 2.3). In the long run, governments could aim to fully implement an automated risk management system.

Box 2.3. Enhancing risk management systems in the European Union

On 1 January 2022, the EU started the operation of the new Customs Risk Management System (CRMS2), building on efforts during the past decade to improve risk management systems and risk profiling across EU Member States. In August 2014, the European Commission adopted a Communication on the EU Strategy and Action Plan for customs risk management “Tackling risks, strengthening supply chain security and facilitating trade”. The strategy comprised seven objectives:

improving data quality and filing arrangements;

ensuring availability of supply chain data and sharing of risk-relevant information among customs authorities;

implementing control and risk mitigation measures where required;

strengthening capacities of border agencies across Member States;

promoting inter-agency co-operation and information sharing between customs and other authorities at the Member State and EU level;

promoting trade facilitation; and

tapping the potential of international customs co-operation.

In April 2020, the European Council adopted new rules that would make it easier for freight transport companies to provide information to authorities in digital form and create a uniform legal framework for electronic freight transport information for all transport modes. All relevant public authorities are required to accept information provided electronically on certified platforms whenever firms choose to use such a format to provide information as proof of compliance.

To better identify non-compliant traders and improve the quality of data for risk analysis, interconnections between databases are being undertaken. One example is the implementation of postal parcels analysis in the national risk profiling system as well as making improvements to the national risk profiling system and other IT systems to strengthen anti-smuggling measures. Another example is the enhancing of risk management systems to enable users to connect and search a variety of data sources to which they have authorised access and bring those results directly into intelligence analysis.

Co-ordination also includes agreements for co-operation and co-operation centres for customs, police, and border guards on the borders to neighbouring Member States, which exchange information on customs and tax inspections. Participation in joint operations has increased the effectiveness of detecting irregularities through the use and application of acquired knowledge and exchange of experience on the methods of risk analysis used.

Improved integration and use of risk profiles and information is possible due to developments in automatic links between issued digital certificates and customs declaration, one-stop shops in ports, and a common repository of documents where the economic operator can include the information required for issuing the certificates and all the authorities that have access.

Progress in several EU economies includes a fully operational system as well for exchanging certificate data in the frame of the national customs Single Window. This would also gradually allow the co-ordination of controls and risk analysis through customs pre-declaration prior to the arrival of the goods, thus providing involved authorities with better information in advance.

Source: OECD TFIs repository.

Recommendation 2.3: Systemic border agency co-operation mechanisms could boost regional co-ordination and collaboration

TFI scores in Central Asia highlight the potential to enhance co-operation between border agencies in areas of risk management and inspections. This also suggests a need to delegate selected border agencies’ controls to customs. Training and empowering customs agents to act on behalf of certain border agencies in specific contexts could reduce clearance times and costs for traders (Box 2.4). Making annual customs and other border agencies’ reports with Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) available online would boost transparency and impartiality.

Governments should consider improving the ways inter-agency co-ordination platforms operate in practice. Inter-agency coordination, including through the already established National Trade Facilitation Committees (NTFCs), needs to be supported by steering committees to monitor the implementation of decisions and by publishing meeting summaries and decisions on a dedicated webpage. Governments should develop domestic mechanisms to support inter-agency co-ordination with a mandate establishing its terms of reference and activities. A permanent technical secretariat should be set up with clear provisions on how it will publish its decisions and make available its recommendations. Governments should elaborate on how its activities are financed, as sufficient financing and clarity of inter-agency platforms and NTFCs activities are required to ensure the continuity and sustainability of their activities. Creating an inter-agency steering committee including at least two-thirds of relevant border agencies would be a helpful step towards the monitoring of the implementation of decisions. By strengthening the institutional framework for domestic border agency co-operation, governments can consolidate mechanisms for both strategic coordination as well as day-to-day, on-the-ground collaboration.

The domestic mechanisms for co-ordination can provide important support to further enhance border agency co-operation at the regional level, as well as with other trading partners. Border agencies part of NTFCs should consider setting up a platform for NTFCs in the region to regularly meet and discuss with the private sector. Governments could also implement the necessary regulatory frameworks for their relevant border agencies (e.g., sanitary and phytosanitary agencies, health agencies, environmental agencies etc.) to delegate control of certain activities to customs agencies and enhance more broadly internal risk management co-operation between border agencies, drawing for instance on the experiences within the EU context (Box 2.3).

Central Asia could benefit from different mechanisms to harmonise data requirements and documentary controls, co-ordinate different border agencies’ computer systems and work towards the interoperability of national trade Single Windows. Developing and sharing common facilities at border posts can provide the hard and soft infrastructure to share border control results to improve risk analysis and risk management co-operation. The experience of Switzerland and its EU neighbours, could provide useful insights, for instance (Box 2.4). Governments could look to exchange staff and hold training programmes for border agency officials at a regional level to develop interoperability and competencies and reduce performance gaps. As countries gradually implement AO programmes domestically, they could move to implementing Mutual Recognition Agreements / Arrangements on AOs at a regional level and with other trading partners. This would require co-ordination with respect to the benefits granted to AOs as well as criteria for the AO certification process.

Box 2.4. Cross-border agency co-operation in practice: Switzerland and its EU neighbours

Switzerland’s customs agency, Swiss Customs, works closely with other agencies involved in border inspections and even undertakes inspections on behalf of other entities, easing domestic co-ordination. The government has established an extensive cross-border co-operation programme with its EU neighbours across all areas in Article 8.2 of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). The programme draws extensively on the strong legal framework within which Swiss Customs operates, including international trade agreements, a series of bilateral agreements with the EU, and individual bilateral agreements with EU countries bordering Switzerland.

The programme’s success is attributed in part to the use of standard trade facilitation systems and adherence to global conventions such as the World Customs Organization’s Revised Kyoto Convention, which enables the use of similar processes at the borders between Switzerland and the EU. Using international data standards for trade documentation and data exchange has facilitated interoperability for transit procedures.

The use of risk management and Swiss-EU collaboration in defining security risk profiles results in a low level of documentation-related or physical controls of goods crossing the border. In addition, the existence of a common security zone between Switzerland and the EU reduces the number of necessary checks. The advanced level of customs automation and the use of juxtaposed customs offices at main border crossings with shared facilities and co-ordinated procedures minimises the amount of time trucks spend at the border.

Source: OECD TFIs repository.

References

[6] Central Asia News (2021), ASYCUDA presented in Kyrgyzstan, https://centralasia.news/9010-asycuda-presented-in-kyrgyzstan.html (accessed on 4 October 2023).

[7] Embassy of Uzbekistan (2020), UNCTAD to create new opportunities for Uzbekistan entrepreneurs, https://uzbekembassy.com.my/eng/news_press/unctad_to_create_new_opportunities_for_uzbekistan_entrepreneurs.html (accessed on 4 October 2023).

[2] Info Trade Central Asia (2023), Central Asia Gateway, https://infotradecentralasia.org/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

[1] ITC (2023), Central Asia reaches milestones in connecting small businesses to European markets, facilitating international trade, https://intracen.org/news-and-events/news/central-asia-reaches-milestones-in-connecting-small-businesses-to-european (accessed on 22 August 2023).

[8] López González, J. and S. Sorescu (2019), Helping SMEs internationalise through trade facilitation, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 229, OECD Publishing, Paris,, https://doi.org/10.1787/2050e6b0-en.

[9] OECD (forthcoming), Realising the Potential of the Middle Corridor, OECD Publishing.

[3] Silk Road Briefing (2022), Kazakhstan Benefitting From Middle Corridor Haulage, https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2022/10/13/kazakhstan-benefitting-from-middle-corridor-haulage/. (accessed on 12 September 2023).

[5] UNCTAD (2022), UNCTAD ASYCUDA Customs Transit Solutions, https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/MTW06_EN-Dmitry_GODUNOV.pdf.

[4] UNCTAD (2019), “Kazakhstan rolls out a single window to boost trade”, UNCTAD, https://unctad.org/news/kazakhstan-rolls-out-single-window-boost-trade.

Note

← 1. Turkmenistan’s TFI collection is an ongoing process; there are not yet any full-fledged scores.