This chapter provides a comprehensive analysis of the public finances of the Brussels-Capital Region and its municipalities. After examining the evolution of fiscal federalism in Belgium and the Brussels-Capital Region over the past decades, this chapter presents a thorough examination of the key public finance challenges and puts forth a range of policy recommendations to tackle these issues, ultimately working toward bolstering fiscal sustainability.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium

4. Financing the Brussels-Capital Region and its municipalities

Abstract

The institutional structure of the Brussels-Capital Region has become increasingly complex due to successive state reforms, leading to the devolution of many competencies from the federal to the subnational levels of government, in particular the regional one (see Chapter 3). While the sixth state reform aimed to enhance fiscal regional autonomy, imbalances between decentralised expenditures and revenues persist, exacerbated by the post-COVID crisis and current inflationary pressures.

In addition, as seen in Chapter 3, the Brussels-Capital Region faces similar but also unique metropolitan and urban challenges due to its specific characteristics. On the one hand, as in many metropolitan areas across OECD countries, the Brussels-Capital Region’s economic activity and commuting flows extend well beyond its administrative borders, with one in two workers in the Brussels-Capital Region coming from outside its borders (Actiris, 2023[1]). On the other, as the Brussels-Capital Region includes the Belgian and European capital, it plays a vital role, which brings both benefits and constraints, including increased charges, such as centrality-related costs and metropolitan infrastructure investment needs. The issue of fairly compensating the Brussels-Capital Region for the costs it incurs while contributing to the country’s wealth remains a contentious topic that is closely tied to the institutional framework that allocates powers, responsibilities and resources to Belgium’s different regions, communities and local governments.

At the local level, municipalities are also grappling with rising expenditures, resulting in over half of them facing budget deficits, which is not permitted by law. While the “golden rule” has helped limit municipal debt, the escalating pension costs of statutory and contractual personnel pose a significant concern for future years.

After examining the evolution of fiscal federalism in Belgium and the Brussels-Capital Region over the past decades, this chapter provides a comprehensive assessment of public finance challenges in the Brussels‑Capital Region and its municipalities and proposes policy recommendations and actions to address them under the current governance framework.

The evolution of fiscal federalism in Belgium and the Brussels-Capital Region

With its three main levels of government (federal, regional, community and local), Belgium has often sought to reform its institutional framework since its inception. Over time, six state reforms (in 1970, 1980, 1988‑89, 1993, 2001 and 2011) have gradually transformed Belgium from a unitary to a federated state (see Chapter 3). The sixth state reform devolved more powers and competencies from the federal to the regional and community levels and further enhanced the fiscal autonomy of the federated entities by introducing regional personal income tax (PIT) and enhancing budgetary autonomy (Table 4.1).

As mentioned in the previous section, there is no hierarchical relationship among the Federal Authority, the regions and the communities. All three are considered equal from a legal perspective, each being granted specific powers and responsibilities in various areas. Importantly, institutional reforms have been accompanied by funding and financing legislation changes, mainly the Special Law of the Funding of Regions and Communities. Table 4.1 offers an insight into the most important fiscal measures taken throughout the different reforms.

Table 4.1. The main legislative changes in financing prior to the sixth state reform

|

Reforms |

Main legislative changes in financing |

|---|---|

|

1970 |

|

|

1980 |

|

|

1988-89 |

|

|

1993 |

|

|

2001 |

|

Source: Based on OECD/UCLG (2022[2]), 2022 Country Profiles of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment, https://dev.mediactive-studio.com/maquettes/OCDE/menu.html; Wong, Y. (2023[3]), “Fiscal federalism in Belgium: Challenges in restoring fiscal sustainability”, https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400235511.018; Bayenet, B. and G. Pagano (2013[4]), “Le financement des entités fédérées dans l’accord de réformes institutionnelles du 11 octobre 2011”, https://doi.org/10.3917/cris.2180.0005.

The Special Law enacted on 6 January 2014, which substantially amended the SFA, marked a significant turning point in the realm of regional fiscal autonomy within the framework of the sixth state reform. This legislative reform resulted in a substantial increase in main public finance indicators, especially compared to OECD country averages, and more in line with other OECD federations (Box 4.1).

A primary facet of this transformation involved a greater number of decentralised funding mechanisms with, for example, an increase in tax autonomy, providing regions with the authority to levy additional contributions to PIT. This sought to effectively link the economic and employment policies of regions to their budgetary revenues, which enhanced fiscal autonomy and fostered greater control but simultaneously rendered regions more susceptible to the ebb and flow of economic fluctuations. In addition, the reform facilitated the allocation of tax reductions based on individual expenditures pertinent to regional material powers. The legislative overhaul also mandated partial refinancing adjustments for the Brussels-Capital Region, either from the federal budget acknowledging its role as a national and international capital or from the budgets of the other two regions. Moreover, regions assumed a triple responsibility encompassing pensions, greenhouse gas emission reductions and employment initiatives. This reshaping of financial responsibilities corresponded with broader efforts towards budgetary consolidation and addressing the challenges posed by an ageing population. Notably, a transition mechanism was instituted, ensuring each federated entity a guaranteed nominal amount in alignment with the Special Act of 1989 for a decade, followed by a gradual decline in the guarantee. This mechanism, the National Solidarity Mechanism, is expected to expire in 2025 (see below). Amidst these changes, adherence to principles of federal loyalty, prevention of unfair tax competition, avoidance of double taxation and alignment with European economic and monetary norms formed integral components of the reformed fiscal landscape (CEJG, 2017[5]).

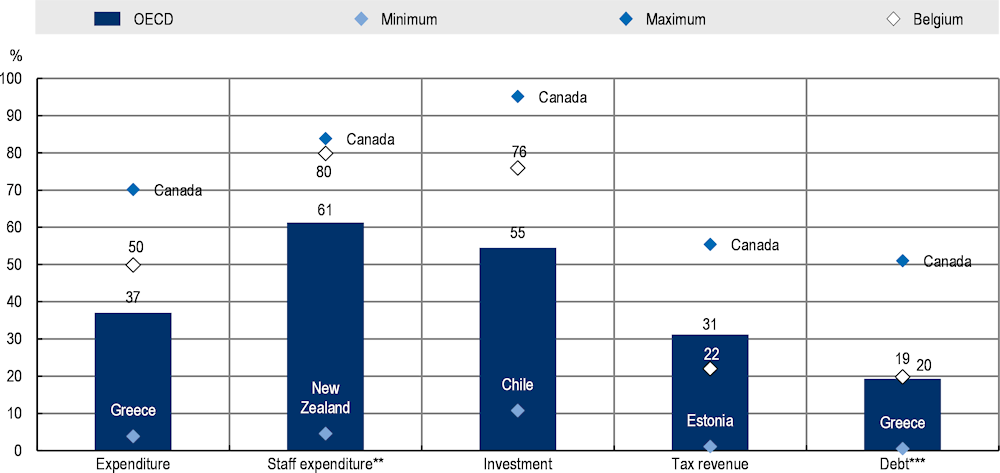

Box 4.1. A comparison of Belgium’s subnational public finance indicators with OECD averages

In the wake of federalisation and fiscal decentralisation, subnational governments have taken on a significant role in Belgium’s public expenditure landscape. In 2021, they contributed 49.9% to public spending, equivalent to 27.6% of gross domestic product (GDP), a notable surge from the 38.5% of public expenditure and 20.2% of GDP recorded in 1995. This growth has propelled Belgium’s subnational government shares beyond the OECD average for federal countries, registering at 44.3% and 20.0% for public spending and GDP respectively, in 2021. Within this framework, regions and communities shoulder the primary load of subnational government expenditure, constituting 75% of the total and 37.3% of overall public expenditure. In contrast, while still substantial, local government spending occupies a relatively smaller space, contributing 25.2% to subnational government expenditure and 12.6% to total public spending.

These subnational entities have become vital not only in shaping the public expenditure landscape but also in employment, engaging 79.8% of the total public workforce spending, surpassing the 76.0% seen in OECD federal countries. Municipalities and provinces stand as significant employers too, allocating over half of their budgets to staff expenditure and encompassing 40.3% of subnational government staff spending. This financial commitment to staff is intertwined with the rising expenses tied to funding statutory officials’ pensions, which presents a distinct fiscal challenge.

Figure 4.1. Subnational governments as a percentage of general government, 2021

* 2013 data for Colombia for all indicators except debt (2014).

** No data for Australia and Chile.

*** Debt OECD definition, i.e. including insurance reserves and other accounts payable. No data for Chile, Mexico and New Zealand

Source: OECD (2023[6]), Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data (brochure), OECD, Paris.

Belgian subnational governments are also major public investors, contributing to 75.9% of public investment, surpassing figures of 61.4% in OECD federal countries and 55% in OECD countries. Among these subnational entities, regions and communities exhibit prominent significance, accounting for 68% of the overall subnational government investment in 2021. Their investment focus predominantly revolves around economic affairs and transportation, constituting 34% of the subnational government investment in 2021, followed closely by general services at 29%, and subsequently encompassing education, recreation, culture and religion.

As for revenue, the composition of subnational government revenue out of total public revenue increased by 8%, rising from 43.8% in 2013 to 51.9% in 2021, which can be attributed to the impacts of the sixth state reform. Notably, regions and communities contribute to nearly three-quarters of the subnational government revenue, while local governments account for 27%. However, the ability to finance expenditure through own-source revenue remains limited for regions and almost non-existent for communities whose competencies lack distinct territorial bases. Despite the sixth state reform, the largest part of combined subnational government revenue continues to stem from grants and subsidies, composing 58.2%. Comparatively, subnational government tax revenue, standing at 25.6% of the total revenue in 2021, falls notably below averages of 42.7% for OECD federal countries and 31.2% for OECD countries. This trend persists when considering the proportions of subnational government tax revenue in Belgium’s GDP and public tax revenue, with respective figures of 6.6% and 22.0%, which lag behind the OECD federations (9.3% of GDP and 42.7% of public tax revenue on average) and the OECD countries (7.2% and 31.2%).

Finally, subnational debt in Belgium accounts for 19.8% of the overall public debt and 25.6% of GDP. These figures slightly surpass the OECD average of 19.3% of total public debt and 25.5% of GDP, yet they remain below the average for OECD federal countries, where subnational debt represents 25.2% of total public debt and 32.5% of GDP.

Source: Based on OECD (2023[6]), Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data (brochure), OECD, Paris; OECD/European Commission (2020[7]), Pilot Database on Regional Government Finance and Investment: Key Findings, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/REGOFI_Report.pdf.

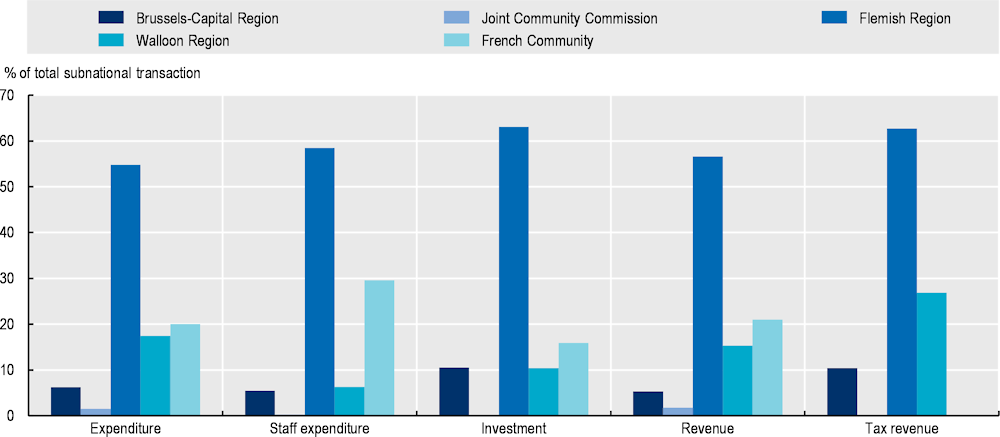

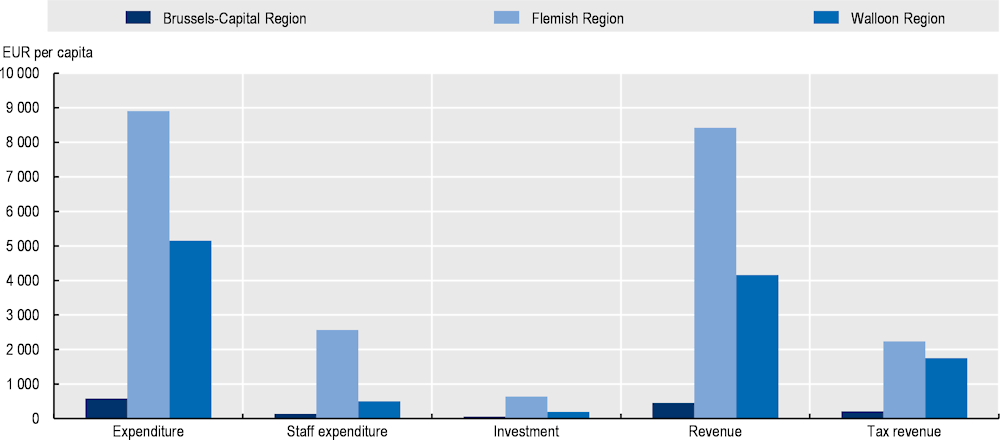

After the sixth state reform, a comparison among federated entities unveils some striking inter-regional disparities (Figures 4.2 and 4.3). Whether measured as a percentage of total subnational transactions or in per capita terms, the indicators for the Brussels-Capital Region consistently lag behind those of other regions, often significantly so. Out of all subnational expenditure in Belgium, only 6.2% takes place within the Brussels-Capital Region (around 7.7% if the Joint Community Commission is taken into account). This starkly contrasts with the Flemish Region, which accounts for 54.8% of the country’s subnational spending. The French and Walloon Regions jointly reach 37.3% of subnational expenditure. This disparity is particularly significant in per capita terms, where the Flemish Community and the Walloon Region allocate EUR 8 094 and EUR 5 154 per capita compared to the Brussels-Capital Region’s EUR 585. Similar dynamics extend to other subnational finance indicators. For instance, 58.4% of total subnational staff expenditure in Belgium is attributed to the Flemish Region, roughly over EUR 2 500 per capita, compared to 5.4% and EUR 137 respectively for the Brussels-Capital Region.

Similarly, subnational investment is much higher as a proportion of total subnational investment in the Flemish Region (63.1%), while the French Community, the Brussels-Capital Region and the Walloon Region each allocate 15.9%, 10.5% and 10.4% respectively. In per capita terms, subnational direct investment ranges from EUR 643 in the Flemish Region to only EUR 62 per capita in the Brussels‑Capital Region, i.e. over ten times more. This low level of subnational investment per capita in the Brussels-Capital Region is notably linked to the revenue trends observed, encompassing both total revenue and tax revenue exclusively. The share for the Brussels-Capital Region accounts for merely 5.3% of total subnational revenue and 10.4% of subnational tax revenue. In per capita terms, the Brussels-Capital Region receives over 18 times less revenue than the Flemish Region and 9 times less than the Walloon Region, amounting to EUR 8 420, EUR 4 160 and EUR 456 per capita respectively. This raises significant questions on the adequate funding of the Brussels-Capital Region, particularly considering its substantial investment needs in regional, inter-regional, urban and metropolitan infrastructure in the forthcoming years to align with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the objectives outlined in the digital and green transition strategies.

Figure 4.2. Main indicators on subnational finance across federated entities, 2021

Note: Data from 2021. Note that data for the Flemish and French Community Commissions are not included in the Plan’s Federal Bureau, hence their absence in this figure.

Source: Plan’s Federal Bureau (2023[8]), Annexe statistique HERMREG: 1995-2028.

Figure 4.3. Main indicators on subnational finance across regions per capita

Note: Data from 2021. Only regions are considered as official population data are only provided at the regional level, not the community level.

Source: Plan’s Federal Bureau (2023[8]), Annexe statistique HERMREG: 1995-2028.

Assessment of public finances in the Brussels-Capital Region

The decentralisation trend in Belgium has resulted in the transfer of numerous competencies to the regions, communities and municipalities, a process that gained significant impetus with the sixth state reform (see Chapter 3). This section provides an assessment of essential public finance indicators in the Brussels‑Capital Region, encompassing expenditure, investment, revenue and debt, both at the regional and municipal levels. Evaluating the current status and trends of public finances lays the foundation for recognising challenges and, in the next section, formulating evidence-based recommendations.

Increasing expenditures have been accompanied mostly by tax revenue, yet the budget balance has continued to deteriorate

Staff costs and transfers to municipalities have grown substantially over the last decade

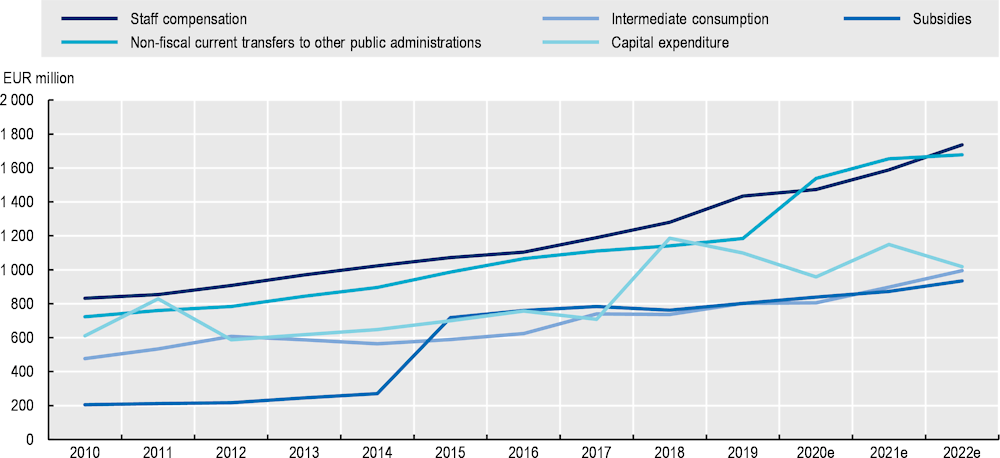

Total expenditures in the Brussels-Capital Region amounted to EUR 7.4 billion in 2022, representing a 123% increase from 2010, and are expected to reach 7.8 billion in 2023 (Figure 4.4). This rise in expenditures has been recently aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery policies as well as the inflationary pressures on energy prices, among others, stemming from the effects of Russia’s large-scale war of aggression against Ukraine.

Most of the Brussels-Capital Region’s expenditure is current expenditure, dedicated to two main items: staff salaries (32.5% of total current expenditure in 2022) and current transfers to other public administration services (namely municipalities, accounting for 31.4% of total Brussels-Capital Region’s current expenditure). Current transfers to municipalities have been intensified especially from 2019, following the reallocation of competencies to the local level with the sixth state reform and have continued to increase amidst the COVID-19 crisis. This aims to match newly allocated competencies at the local level with sufficient and adequate resources at the local level, thereby avoiding the emergence of under- or unfunded mandates, a phenomenon that has been shown to put a drag on economic growth and development (Rodríguez-Pose and Vidal-Bover, 2022[9]).

Figure 4.4. The Brussels-Capital Region’s expenditure by economic classification

Note: In nominal terms. Years followed by an “e” show estimated values.

Source: IBSA/BISA (2023[10]), Finances publiques, https://ibsa.brussels/themes/finances-publiques (accessed on 31 July 2023).

Regarding investment, Figure 4.4 shows that Brussels-Capital Region’s capital expenditure has substantially fluctuated but has overall increased throughout the decade to account for 16.0% of the region’s total expenditure in 2022. Importantly, since 2016, some of these investments have been labelled as “strategic investments” by the government of the Brussels-Capital Region (Box 4.2). Indeed, the latter considers that certain investments have a particular strategic value linked to the green and digital transitions. The government is thus willing to finance those investments with public debt, which has grown substantially over the years.

Box 4.2. Financing strategic investments in the Brussels-Capital Region

Strategic investments were introduced in 2018 as highly targeted capital expenditures focused on essential infrastructure projects for the region. The primary focus areas include expanding and renovating the metro system, as well as upgrading architectural structures like tunnels and viaducts. Additionally, there was an emphasis on improving security measures following the Brussels attacks in 2016.

The government of the Brussels-Capital Region has considered these investments to have a neutral impact on the budget, most importantly because these investments are seen as key to accelerating the green and digital transitions and securing long-term economic development. Yet, as seen below, debt levels have increased substantially since the introduction of these investments.

In 2018, a budget of EUR 360 million was allocated to strategic investments, of which 96% was finally executed. In 2019, the projects associated with the strategic investments, which had been initiated in 2018, gradually progressed, leading to a budget increase of EUR 472 million, which increased to almost EUR 500 million for 2021. To cover the financial deficit, the initial consolidation plan for 2020, following a similar approach to previous years, relied on the projected amortisations for 2020 (EUR 206 million) and the approved volume of strategic investments (EUR 500 million). In early 2020, the 2020 consolidation plan was increased by an additional EUR 300 million to lower the high floating debt from 2019. Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly EUR 1 billion was allocated for baseline consolidations in 2020. Notably, much of this was covered in 2019 through a “consolidations” strategy that raised EUR 414 million and forward-start financing of EUR 95 million.

Examples of strategic investments include the renovation (not the maintenance) of some tunnels, such as the Annie Cordy Tunnel, which is being financed through a public-private partnership where the public investment is labelled as a strategic one. Strategic investments also include the financing of a new metro project, the extension of certain tramlines, the electrification of the bus fleet, the purchase of a new stock of buses, etc.

Source: Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (2022[11]), Exposé général du budget pour 2023 - Algemene toelichting bij de begroting 2023; OECD (2023[12]), “Questionnaire to the Brussels-Capital Region”, OECD, Paris.

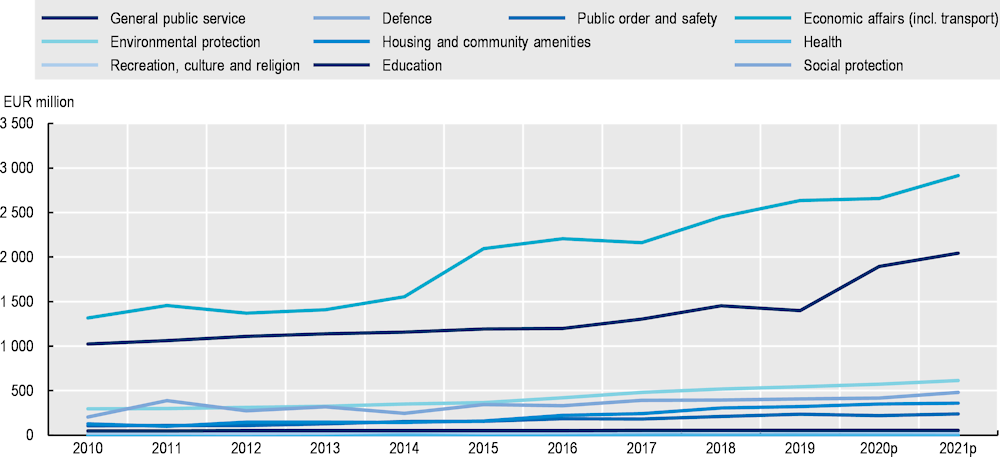

Economic affairs (including transport) and general public services (administrative costs and debt service) are by far the largest regional expenses (Figure 4.5). Urban development expenditures have also been significant since 2016 as the Brussels-Capital Region has launched seven Urban Renovation Contracts, amounting to a total of EUR 154 million. Moreover, the Brussels-Capital Region has also co‑financed 2 operational programmes for urban development with European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) funds since 2010 (EUR 115 million from 2007 to 2013 and EUR 200 million from 2014 to 2020). For the new operational programme 2021-27, the Brussels-Capital Region will co-finance urban development projects amounting to a total of EUR 300 million. Environmental expenditure has also slowly but steadily increased by 48% over a decade.

Figure 4.5. Brussels-Capital Region expenditure by functional classification

Note: In nominal terms. Years followed by a “p” show provisional values.

Source: IBSA/BISA (2023[10]), Finances publiques, https://ibsa.brussels/themes/finances-publiques (accessed on 31 July 2023).

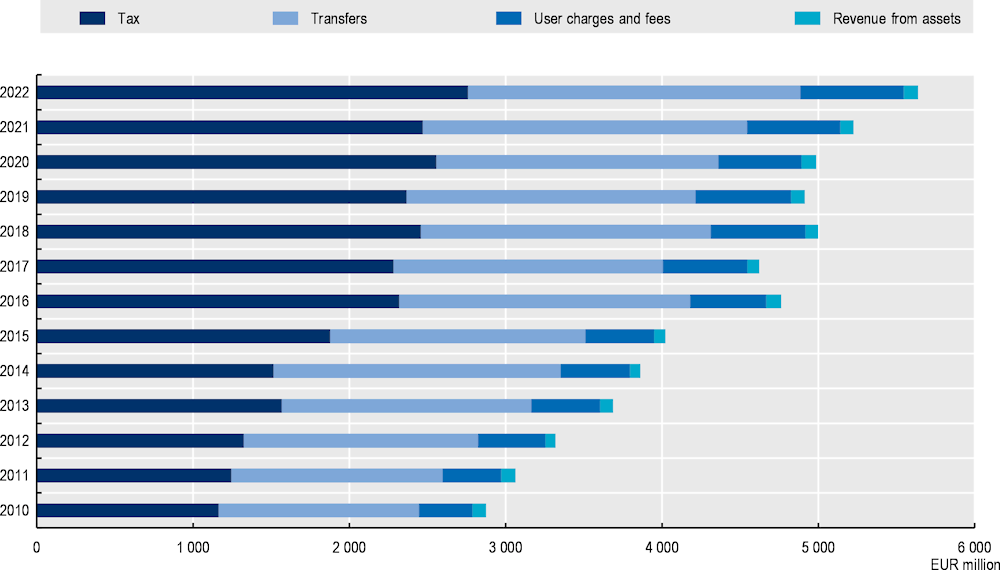

Since 2010, tax revenue has increased significantly, 70% more than transfers

The revenues for the Brussels-Capital Region amounted to a total of EUR 5.6 billion for 2022, representing a 7.3% increase in nominal terms compared to the previous year’s budget in 2021 and a 49.7% increase since 2010 in nominal terms (Plan's Federal Bureau, 2023[8]).

Tax revenues accounted for 47.0% of the Brussels-Capital Region’s revenues, making them by far the primary source of regional revenues (Figure 4.6). Between 2010 and 2022, tax revenue witnessed a notable growth of 136% in nominal terms, reaching a total of EUR 2 758 million, while transfers only increased by 66%, also in nominal terms. Comparatively, transfers stand at 39.5%, while fees and assets both represent 11.3% and 1.6% of the total budget. The prevalence of tax revenue in relative terms within the Brussels-Capital Region’s budget may be pointing to insufficient transfers to cover the additional expenditures which the region incurs, including those that aim to compensate for the Brussels-Capital Region’s specificities (see Figure 4.8 below). Nevertheless, tax revenue in the Brussels-Capital Region represents 10% of total subnational tax revenue in Belgium, thus a significantly lower amount relative to the rest of the regions, as a total and in per capita terms (see Figures 4.2 and 4.3 above).

Tax revenue in the Brussels-Capital Region is composed of various sources. First, the region sets the tax base and rate of 11 regional taxes, including registration, inheritance or circulation taxes, as listed in Article 3 of the Special Federal Law of 16 January 1989 on the Funding of the Regions and Communities.1 These taxes have been decentralised from the Federal Authority to the regions, granting them the authority to regulate the rate or tax base, subject to certain limitations.2

Second, regions and municipalities in Belgium also possess the authority to introduce new taxes and determine their rates, provided that a bill meeting the principles of taxation (as described in Articles 170 to 173 of the constitution) is adopted by their respective democratic councils while adhering to the aforementioned principles. Consequently, the Brussels-Capital Region imposes several taxes that are distinct from the regional taxes mentioned in the special law above.3 The Brussels-Capital Region also collects the taxes falling pertaining to the Brussels Agglomeration.4

Figure 4.6. The evolution of revenue streams at the regional level

Moreover, following the sixth state reform, the previous system in which the Federal Authority established a base rate and distributed a share of income tax revenue to the regions underwent modification. Even though the Brussels-Capital Region and the other regions and communities are generally prohibited from creating taxes, levying “cents” (i.e. surcharges) or granting discounts in matters that have already been subject to imposition by the Federal Authority, this is not the case for PIT. For this particular tax, the regions have the flexibility to levy a surtax or even reduce the base rate originally set by the Federal Authority. As a result, total revenues from PIT are separated in the budget into tax revenue and transfers: the funds stemming from the base rate put in place by the Federal Authority are accounted for as transfers to the Brussels-Capital Region, whereas those collected through the surtax on PIT are accounted for as tax revenue. In 2021, revenue from PIT accounted for 38.6% of total revenue. More precisely, revenue from PIT represented 36.2% of total tax revenue and 58.6% of total transfers received by the Brussels-Capital Region. Both streams of funding are equally non-earmarked revenue to be spent at the discretion of the Brussels-Capital Region’s government. This shows that the Brussels-Capital Region retains considerable freedom to shape its tax policies and optimise its revenue streams within the parameters set forth by the Federal Authority. Its tax autonomy is thus significant relative to other European counterparts (OECD/UCLG, 2022[2]).

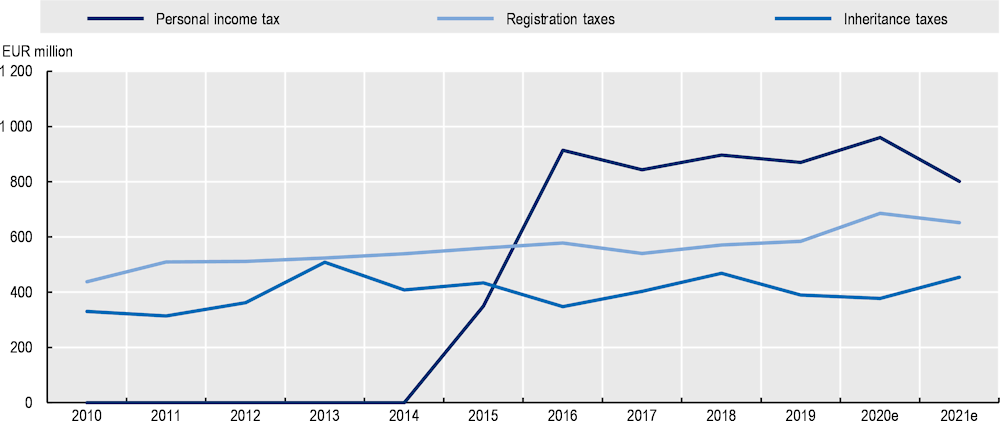

Figure 4.7 shows how the different sources of tax revenue have evolved over the last decade. The revenues from the surtax on personal income tax levied by the Brussels-Capital Region soared between 2014 and 2016 since this was incorporated in the funding system following the sixth state reform, accounting now for 32.4% of the Brussels-Capital Region tax revenues in 2021 (IBSA/BISA, 2023[10]). Registration taxes and inheritance taxes come second and third respectively, as sources of revenue, increasing by 33% and 27% since 2010.

Figure 4.7. Evolution of main tax revenue sources in the Brussels-Capital Region

Note: Years followed by an “e” show estimated values.

Source: IBSA/BISA (2023[10]), Finances publiques, https://ibsa.brussels/themes/finances-publiques (accessed on 31 July 2023).

Mechanisms to compensate for the Brussels-Capital Region’s special circumstances in place may be insufficient or discontinued in the coming years

In the Brussels-Capital Region, there are several transfers, most of which come from the Federal Authority. In the adjusted 2022 budget, transfers from the Federal Authority represent 33.6% of the total revenue of the Brussels-Capital Region. Out of these transfers, 35.0% account for the transfers from PIT’s base rate set and collected by the Federal Authority to be transferred later to the Brussels-Capital Region. This has been the case since the sixth state reform in order to finance the newly devolved competencies to the region. Other transfers from other institutions to the region are those from the Brussels Agglomeration (EUR 255 million), the European Union (totalling EUR 142.1 million) and finance.brussels (EUR 8.9 million) (Voglaire et al., 2022[13]).

Two other types of transfers coming from the Federal Authority are worth highlighting, given the specific circumstances of the Brussels-Capital Region: compensation transfers and equalisation transfers. These are both key for the region. Considering the international role and capital function of the City of Brussels, the Brussels-Capital Region faces distinct challenges that are not encountered by other federated entities. While this presents opportunities for the Brussels-Capital Region, it also places a financial burden on it. For instance, the fact that one in two workers are commuters leads to revenue losses (see Chapter 1) whereas the security needs incurred both by the region and the municipalities in the Brussels-Capital Region push expenditure up substantially (Verdonck, 2023[14]). Moreover, past studies have quantified the costs and revenue losses stemming from the substantial commuter population, estimating approximately EUR 490 million per year in 2003 (Van Wynsberghe et al., 2009[15]).

In the initial stages of the existence of the Brussels-Capital Region, there were no specific mechanisms to compensate for the additional costs that the region faced. An exception to this rule was the signature of the co-operation agreement giving birth to the Beliris funds. These funds were designed to finance joint initiatives between the Federal Authority and the Brussels-Capital Region, ensuring that the region can finance and exploit its role as an international capital. Although these funds are useful to carry out important investments in the Brussels-Capital Region, over time, the allocation criteria have become less transparent. The increasing use of Beliris to fund expenses beyond its legally defined scope raises questions about transparency in the allocation of Beliris-related funds and, above all, represents a symptom of underfunding in the Brussels-Capital Region, calling for the implementation of more targeted financing mechanisms (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Financing the Brussels-Capital Region as host of the capital of Belgium and the European Union through Beliris

The Federal Authority and the Brussels-Capital Region concluded a co-operation agreement on 15 September 1993, aimed at promoting the City of Brussels’ international role and function as capital city, which subsequently created two funds known as Beliris I and Beliris II. This agreement entails joint initiatives between the Federal Authority and the Brussels-Capital Region, ensuring that the region can fully embrace its role as an international capital. Over time, several amendments have been made to this agreement through the Cooperation Committee.

The underlying principle of Beliris is that promoting the City of Brussels’ international role benefits the entire country and should not be the sole responsibility of the Brussels-Capital Region. The initiatives covered in the agreement mainly pertain to mobility, strategic area development, public buildings and spaces, land acquisition, priority zone development, neighbourhood revitalisation and cultural, scientific and heritage investments.

Initially, the initiatives focused on serving all Belgians, with projects like the Belliard Tunnel catering to commuters leaving the Brussels-Capital Region. As time passed, the initiatives became more oriented towards the residents of the Brussels-Capital Region, including neighbourhood contracts (contrats de quartier/wijkcontracten), metro station renovations, the elevator works at Place Poelaert and the restoration of parks and pools. Nevertheless, the international role of the Brussels-Capital Region was not forgotten, as seen through projects like the Atomium’s renovation and the development of the Square exhibition and conference centre.

To further finance the Brussels-Capital Region’s international role and capital function, the law of 10 August 2001 created a fund specifically for this purpose, divided into two sub-funds: the “Fund for financing the international role and the function of the Capital of Brussels” (known as Beliris I) and the “Fund for financing certain expenses incurred which are linked to security arising from the organisation of European summits in Brussels, as well as security and prevention expenses in relation to the function of national capital and Brussels International” (Beliris II). The Cooperation Committee decides on the means to use this fund.

Despite the positive impact of this co-operation agreement, some questions arise regarding its nature. The Beliris funds are not direct financial means allocated to the Brussels-Capital Region. In fact, the Brussels-Capital Region does not exercise any budgetary or technical control over the funds but only participates in the negotiation of allocations that it does not set alone, except in cases where it provides complementary sources of financing. In the end, it seems that the Beliris funds may be aiming to cover specific federal expenses located within the Brussels-Capital Region.

Beliris appears to have a certain coherence within a federal state, as financing important initiatives for the function of the capital and the international role of Brussels seem fully justified for all components of the Belgian federal state. However, Beliris has also financed neighbourhood projects or the renovation of social housing, which may not align well with the limits of intervention specified in Article 43 of the Special Law of 12 January 1989 relating to Brussels institutions. The growing utilisation of Beliris funds for purposes outside its officially designated boundaries raises concerns regarding the transparency of Beliris-related fund allocation. Moreover, it may point to an inadequate funding system of the Brussels-Capital Region, thereby emphasising the need to establish more precise and targeted financing mechanisms.

Source: Peiffer, Q. (2021[16]), “Les spécificités institutionnelles de la région bruxelloise”, https://doi.org/10.3917/CRIS.2510.0005; Beliris (2023[17]), Beliris - Qui sommes-nous ?, https://www.beliris.be/qui-sommes-nous/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

In addition to Beliris, various mechanisms have been established to finance policies that benefit all components of the Belgian federal state. However, these mechanisms are a relatively early addition and the Brussels-Capital Region has historically experienced structural underfunding, both before its establishment and after 1989.

The sixth state reform sought to address the lack of actual compensation transfers by adopting the Special Law of 19 July 2012, “Ensuring fair funding for Brussels institutions”. Four main ideas informed this legislation. First, the crucial role played by the Brussels-Capital Region in the development of Belgium and the other two regions. Second, the recognition that fiscal capacity using the metric of PIT fails to reflect the region’s contribution to wealth creation due to the omission of income from many individuals working within its territory. Third, the revenue loss experienced by the Brussels-Capital Region due to the presence of international and national institutions led to the exemption of numerous properties from real estate taxation. Lastly, there are additional responsibilities imposed on the City of Brussels as a national and international capital, including bilingualism, mobility, education and security (Peiffer, 2021[16]).

Therefore, following the sixth state reform, the Special law of 16 January 1989 concerning the financing of the communities and regions currently acknowledges the unique case of the Brussels-Capital Region and encompasses the following new provisions (Peiffer, 2021[16]):

Compensation for mortmain, which entails granting credits through the Brussels-Capital Region to municipalities where properties, such as Federal Authority buildings or embassies, are exempt from property tax.

The provision of a special endowment to the City of Brussels.

The allocation of a special endowment to the Brussels-Capital Region for mobility policies.

The allocation of a deduction from the proceeds of PIT to the Fund for the International Role and Capital Function of the City of Brussels, intended to cover all security and prevention expenses related to Brussels’ national and international capital functions.

An annual allocation of resources to the Brussels-Capital Region to partially compensate for the loss of income resulting from the presence of international civil servants.

An annual allocation of resources to the Brussels-Capital Region to partially compensate for the loss of income due to commuter flows.

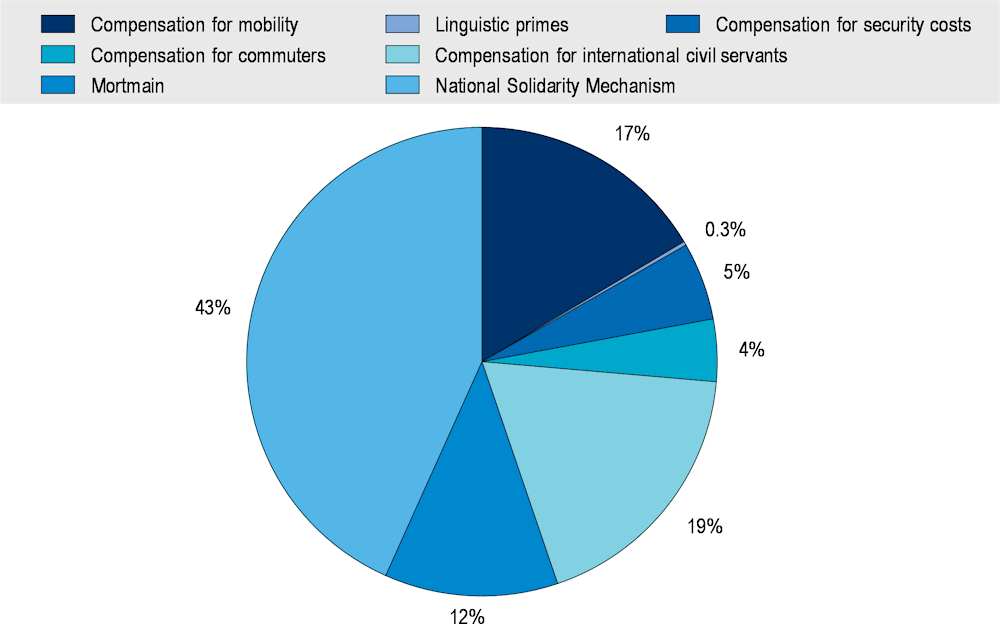

According to the Brussels-Capital Region’s budget for 2022, the Brussels-Capital Region received over EUR 1 billion from different compensation and equalisation mechanisms, each representing 57% and 43% of the total (Figure 4.8). In terms of compensation transfers, compensation for the presence of international civil servants and mobility issues represent 19% and 17% of these transfers, with other lower amounts related to mortmain, security costs, the presence of commuters and linguistic premiums. When compared to the total revenues of the region, compensation (including mortmain) and equalisation transfers account for 11.1% and 9.1% respectively. In other words, 21.0% of the Brussels‑Capital Region’s revenues come from compensation or equalisation transfers.

Apart from the compensation transfers that the Brussels-Capital Region receives, the National Solidarity Mechanism is Belgium’s equalisation instrument and it involves an annual deduction from the proceeds of federal PIT. This system facilitates a vertical transfer of funds from the federal level to the regions. It aims to address disparities by applying the mechanism of national solidarity to regions with a lower share in federal PIT than their share of the population. The calculation of the amount for a specific budget year and region involves multiplying the base amount for that year by 80% of the absolute difference between the region’s percentage in the total revenues of federal PIT and its percentage of the total population of Belgium.

Figure 4.8. Equalisation and compensation allocations in 2022

Note: Adjusted budget for 2022.

Source: Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (2022[11]), Exposé général du budget pour 2023 - Algemene toelichting bij de begroting 2023; Voglaire, J. et al. (2022[13]), “Les perspectives budgétaires de la Région Bruxelles-Capitale de 2022 à 2027”, Centre for Research in Regional Economics and Economic Policy.

Nevertheless, although the National Solidarity Mechanism is projected to increase by EUR 100 million between 2022 and 2024, it is to be discontinued in 2025. This would see one of the main mechanisms for equalisation disappear in Belgium, which is already of limited size compared to other OECD federal countries (Box 4.4). This raises significant uncertainties about how the Brussels-Capital Region will be compensated for this funding gap and effectively prevents long-term strategic planning of key capital investments or current expenditures. Currently, there are discussions that could point the way to two potential solutions. The first involves revising the distribution of national personal income taxes, which is part of a broader political dialogue involving the other two regions. The second option under consideration is the different modalities of implementation of the SmartMove tax, which would generate additional revenue for the Brussels-Capital Region from non-residents who commute into the region for work while simultaneously replacing the road tax and first vehicle registration tax for residents. However, regarding the SmartMove tax, this instrument was not conceived to replace any transfers and was mainly a mechanism to reduce congestion and improve quality of life (see Chapter 2). These discussions are being held in collaboration with the Flemish and Walloon Regions to find suitable and equitable solutions for all parties involved (S&P, 2023[18]).

Box 4.4. Equalisation mechanisms in Belgium and other OECD countries

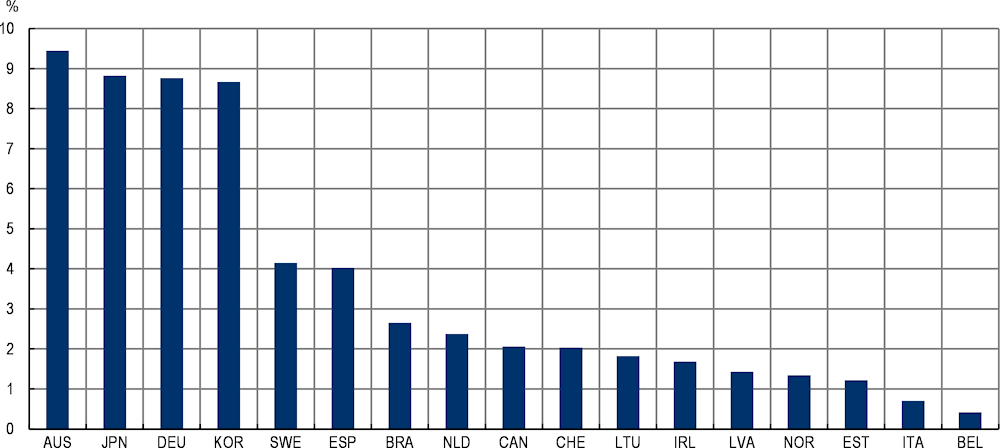

Equalisation mechanisms are most often in place and widely diverse across the OECD. OECD research shows that the size of Belgium’s fiscal equalisation system is relatively small compared to other OECD countries, among countries with the smallest size of equalisation systems. Figure 4.9 depicts the scale of equalising transfers as a percentage of total government expenditure across all levels for 16 OECD countries. With an average of equalising transfers at 3.6% of government expenditure, Belgium has the smallest transfers as a share of total government expenditure (0.6%), whereas Australia has the largest (9.9%). Note that OECD federal countries have a higher average (4.6%) in contrast to Belgium’s score.

Figure 4.9. Equalising transfers as a percentage of total government expenditure across a selected sample of OECD countries

Source: OECD (2021[19]), Fiscal Federalism 2022: Making Decentralisation Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/201c75b6-en.

Equalisation is even more frequent and sizeable in federal countries, where solidarity among the federated states as well as across levels of government is often a constitutional principle. For example, Canada’s fiscal equalisation system, initiated in 1957 and later enshrined in the 1982 constitution, addresses the revenue disparities between provinces by offering unconditional transfers from the federal government to the provinces based on their respective fiscal capacities. At the moment, five provinces benefit from these equalisation payments: Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec. In the 2021/22 fiscal year, equalisation is projected to be the most substantial source of federal transfer payments for each of these provinces, making up over 10% of their total provincial revenues.

Equalisation systems are also subject to modifications. In 2020, the German parliament enacted new regulations and constitutional amendments to reform the intergovernmental fiscal relations between the federal state and the Länder, aiming to increase the federal government’s role. The key aspect of this reform was the elimination of the horizontal equalisation mechanism among the Länder. Instead, the focus now lies on two main categories of grants and equalisation mechanisms: i) the distribution of the Länder’s share of VAT revenue, which takes into account their respective fiscal capacities through surcharges and deductions, and ii) vertical equalisation, involving additional transfers to the economically disadvantaged states, particularly the former East Germany. The latter received “supplementary grants for special needs” for infrastructure until 2019. Additionally, a new provision, Article 143d, was added to the Basic Law, stipulating annual transfers of EUR 400 million from the federal state to Bremen and the Saarland, to support them in adhering to the debt brake regulation for an indefinite period.

Source: OECD/UCLG (2022[2]), 2022 Country Profiles of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment, https://dev.mediactive-studio.com/maquettes/OCDE/menu.html.

Regarding other compensation transfers, the allocations for international civil servants (EUR 189 million in 2022) and commuters (EUR 44 million) have remained stable over time and are projected to continue doing so over the following years (Voglaire et al., 2022[13]). In fact, the amount allocated for commuters is not expected to change, regardless of fluctuations in parameters such as inflation rate or growth rate, which tend to vary from year to year (Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region, 2022[11]). When considering the socio-economic characteristics and investment needs of the Brussels-Capital Region and its municipalities, these allocations appear relatively low when examined in isolation. If past studies, which estimated the costs of a commuter population at approximately EUR 490 million per year in 2003, are to be believed, today, these compensation mechanisms seem insufficient (Van Wynsberghe et al., 2009[15]).

It is worth highlighting that the compensation for commuters is financed proportionally by the Flemish and Walloon Regions, based on their respective shares in commuter flows towards the Brussels‑Capital Region.5 This compensation recognises the territorial specificity of the latter and aims to address the absence of a joint budget or fund for metropolitan endeavours. However, the size of this compensation remains modest.

Increasing costs and modest revenues have led to a significant deterioration of budget balances and debt levels in the Brussels-Capital Region

The regions of Belgium are allowed to run fiscal deficits and incur debt, as well as for current expenditure. While existing fiscal rules in the country cover the Federal Authority, the social security sector as well as the local authorities, this is not the case for the regions, despite the regions’ high share in general government expenditure (EC, 2023[20]). The only instance of fiscal rules at the regional level can be found in the Flemish Region’s multiannual budget, which factored in the implementation of a spending norm for the first time.

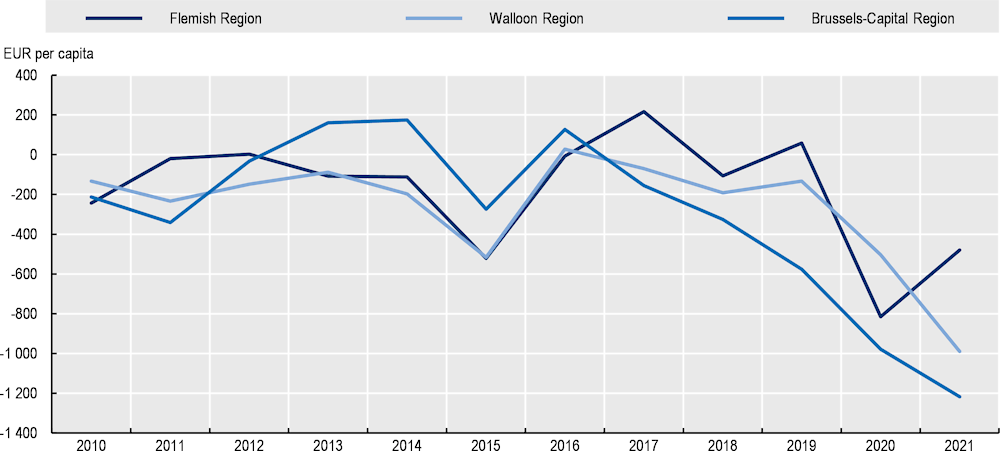

In the Brussels-Capital Region, the absence of sound fiscal rules and rising expenditure costs have led to a steep and persistent deterioration of the budget balance. In fact, the deficit has widened to a substantial EUR 1.6 billion in 2022. When measured per capita, the Brussels-Capital Region has recorded the largest deficits among the rest of the regions since 2017, showing that revenues have struggled to keep up with expenditures (Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10. Budget balance per capita by region

Source: NBB (2022[21]), Public Finance - Non-Financial Account of the Government, https://stat.nbb.be/index.aspx?DatasetCode=NFGOV.

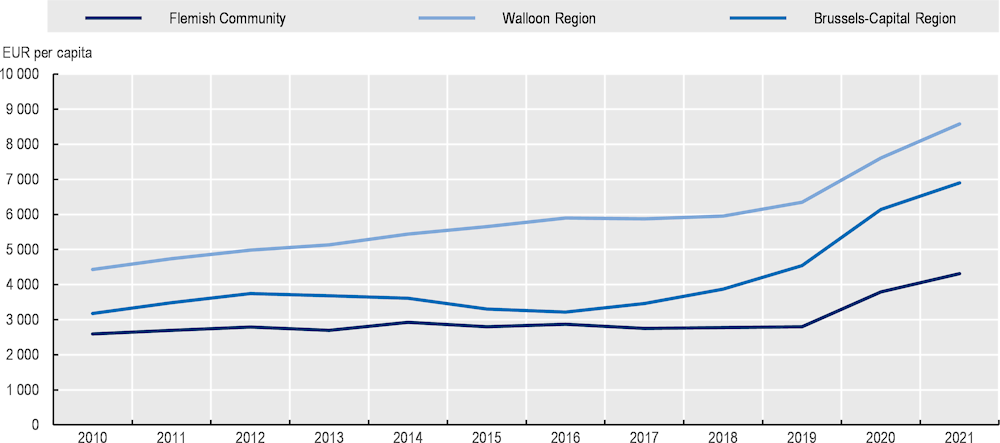

In regard to debt, strategic investments have had a profound impact on the regional trajectory of debt since 2018. Direct debt6 has more than doubled in recent years since 2016, from EUR 2.6 billion to over EUR 7 billion in 2021 (NBB, 2022[21]). Debt per capita has followed the upward trend as well, with the Brussels-Capital Region located between the debt per capita values of the Flemish Region and the Walloon Region (Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.11. Debt per capita by region

Source: NBB (2022[21]), Public Finance - Non-Financial Account of the Government, https://stat.nbb.be/index.aspx?DatasetCode=NFGOV.

On 26 March 2021, the credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s downgraded the long-term rating of the Brussels-Capital Region from “AA” to “AA-” with a stable outlook.7 This downgrade was primarily due to the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and strategic investments, which significantly increased the region’s debt and impacted its revenues and expenses. Despite the increase in debt, Standard and Poor’s noted that the debt service remains relatively stable and the Brussels-Capital Region has solid access to capital markets thanks to proactive and efficient debt and liquidity management. Nevertheless, the credit rating agency maintained in 2022 the long-term rating at “AA-” on 23 September but revised the outlook from stable to negative. According to the agency, the negative outlook reflects the opinion that the reduction of deficits in the Brussels-Capital Region may take longer than expected due to extraordinary costs such as those related to inflation, as well as other operational and investment expenses, particularly in mobility infrastructure, which ultimately increase debt. The deterioration of budgetary performance since late 2019, particularly worsened by the health crisis, was the main reason for the rating downgrade.

The lack of co-ordination of public investment among levels of government risks leading to duplication and inefficiency

Unlike other European Union (EU) countries, Belgium has a unique approach to public investment management, which is primarily overseen by the communities, regions and local authorities, with limited federal government involvement. Historically, investment project selection and monitoring at the federal level have followed procedures similar to other budgetary spending items. However, significant reforms are underway in response to the Recovery and Resilience Facility and other investment packages. These include the introduction of a multi-year investment plan, detailed monitoring mechanisms and the establishment of a high council for public investments.

In the Brussels-Capital Region, investment planning is conducted at the sectoral and sub-sectoral levels, encompassing general public services, housing, community amenities and economic affairs. For strategic investments, particularly in the transportation system (STIB-MVIB), standardised appraisal procedures are applied, accounting for 70% of growth-fostering investments and 30% of all investments in the region. Forward capital estimates are provided for major investment expenditures, like transportation and social housing, which are closely monitored and adjusted as needed due to factors such as permit delays. Capital and current expenditures follow distinct approval processes, with budgets generally including appropriate amounts for standard maintenance. Monitoring STIB-MVIB projects involves a joint committee comprising representatives from the ministry-president, Ministry of Finance and Budget, Ministry for Mobility, Brussels Mobility and the STIB-MIVB. Monthly and quarterly implementation reports are published to ensure transparency and accountability in the process.

Nevertheless, Belgium still faces challenges in effectively governing public investment. Major investment projects often lack systematic monitoring and comprehensive ex ante evaluations, as they are not overseen by a specialised authority. This issue extends across all federal departments and various levels of government, revealing a lack of co-ordination and a common investment strategy among different authorities.

Three primary challenges hinder the multi-level governance of public investment: co-ordination challenges, requiring collaboration between sectors, jurisdictions and government levels, which can be challenging in practice due to the diverse interests of the involved actors; capacity challenges, where weak capacities to design and implement investment strategies may hinder the achievement of policy objectives; framework condition challenges, as good practices in budgeting, procurement and regulatory quality are essential for successful investment but may not consistently exist across government levels (OECD, 2019[22]; 2023[23]).

The main reason budgetary co-ordination in Belgium and in the Brussels-Capital Region has not achieved its desired level of effectiveness is that the 2013 co-operation agreement on budgetary co‑ordination has not been implemented in full. All federated entities and the Federal Authority signed the agreement. However, the concertation committee merely “took note” of the overall fiscal trajectory presented in the 2019 Stability Programme, including the postponement of the fiscal target achievement to 2021 by all government levels. The lack of formal approval has resulted in a lack of agreement on investment targets at each government level.

Therefore, although the 2013 co-operation agreement entrusted the High Council of Finance (HCF) with the responsibility to advise and supervise all government levels on their budget trajectories in alignment with the European Union’s Fiscal Compact, the partial implementation of the agreement undermines its co-ordination role as well as the viability of the overall trajectory towards the medium‑term objective and hampers the monitoring of compliance with fiscal targets by the public sector borrowing requirements section of the HCF. Although the establishment of an Experts Committee of Public Investment at the federal level as of March 2023 must be recognised as a step in the right direction, the effectiveness of the HCF’s co-ordination role will depend on the full implementation of the 2013 co-operation agreement.

Municipal finances are also experiencing expenditure increases and substantial fiscal disparities among them

Municipalities within the Brussels-Capital Region wield significant competencies, including the execution of policies stemming from higher tiers of government (see Chapter 3). This section offers a comprehensive overview of local public finance indicators within the Brussels-Capital Region, focusing particularly on the growing expenses due to the pension and security cost burdens and fiscal disparities among municipalities.

The gradual growth of staff expenditure has driven overall expenditure higher, particularly due to the burden of pensions and security expenses

Expenditure has increased significantly since 2010. Current expenditure amounted to EUR 2.7 billion (that is EUR 2 218 per capita), which represents a 6.0% increase compared to 2021 ordinary expenditures (Belfius, 2022[24]). This sharp rise from one year to another is mainly due to high inflation rates as well as the high energy costs that municipalities – some more than others – face.

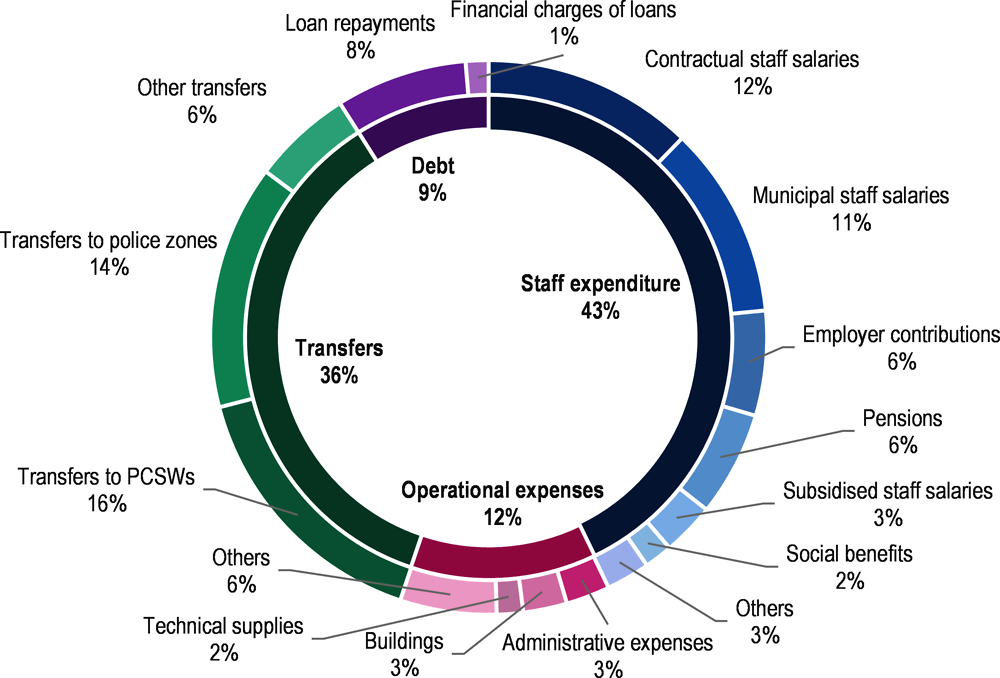

Staff remuneration is the main expenditure item for municipalities, amounting to 38% of total municipal expenditure in 2021 (Figure 4.12) and 43% in 2022 (Figure 4.13) on an unweighted average (Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region, 2022[11]). Transfers make up 36% of the ordinary expenses, slightly surpassing the proportion seen in other regions. A significant portion – 90% of these transfer expenses – is directed towards other local public authorities, fulfilling the municipalities’ obligation to cover the deficits of Public Centres for Social Welfare (PCSWs), police zones, hospitals, religious entities, etc. Transfers to PCSWs and police zones are proportionally higher in per capita terms in the municipalities located at the centre of the Brussels Agglomeration (first ring and canal area), especially in the City of Brussels, when compared to the more residential municipalities (second ring).

Figure 4.12. Evolution of local expenditure by economic classification

Source: NBB (2021[25]), Breakdown of Local Government, National Bank of Belgium, https://stat.nbb.be/.

Staff expenditure by the Brussels-Capital Region’s municipalities increased by 7.4% in 2022 compared to the previous year. This growth was primarily driven by the implementation of the sectoral agreement protocol aimed at upgrading the salaries of local public servants by indexing them to inflation. Energy costs may have also influenced the rise in staff expenditure. According to the social security bureau (ONSS), as of the end of 2021, the number of full-time personnel in the Brussels municipal administrations, including agencies, slightly increased by 0.3% compared to the previous year, totalling 17 531 staff members. Statutory personnel now represent 36.4% of the total municipal personnel, which is significantly higher than in the other regions (24.5% in the Flemish Region and 22.0% in the Walloon Region). It is worth noting that the proportion of statutory personnel varies greatly among the 19 municipalities, with a minimum rate of 20% and a maximum rate of 50% (Belfius, 2022[24]).

Figure 4.13. Current expenditure by category and sub-category for the municipalities

Source: Adapted from Belfius (2022[24]), Les finances des pouvoirs locaux de la région bruxelloise, https://research.belfius.be/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Finances-des-pouvoirs-locaux-de-la-R%C3%A9gion-bruxelloise-2022.pdf.

Pensions are also following an upward trend and are projected to continue doing so. Together with the gradual ageing of a considerable percentage of the Brussels-Capital Region’s population (Comité d’Étude sur le Vieillissement, 2023[26]), this evolution is concerning because the pensions of statutory personnel at the local and provincial levels are covered entirely by their budgets, without intervention from the Federal Authority. Since a legal reform in 2018, the municipalities are also responsible for creating a pension fund for municipal contractual staff. Even though the Solidarity Pension Fund and the double-contribution mechanism should, in principle, suffice to cover all pension expenses without deteriorating the budget balances of municipalities, in reality, this does not seem to apply: since the reform, the Federal Authority has had to intervene in the form of additional transfers amounting to EUR 140 million in 2 years to the municipalities most affected, with the Brussels-Capital Region intervening only minorly. The projected evolution of this expense item is nearly exponential: the contribution rates are expected to increase from EUR 44.6 million in 2019 to EUR 107.2 million in 2025 (Belfius, 2022[24]).

Over a third of municipal expenditures (36%) are undertaken in the form of transfers to other local administrations, including the PCSWs (16%) and the police zones (14%). Municipalities must ensure that these institutions do not have negative budget balances while they deliver the necessary public services. For example, 99.5% of the funding for police zones in 2022 came from transfers from other levels of government, out of which 64.2% came from municipalities, 28.4% from the Federal Authority and 2.6% from the Brussels-Capital Region, on average (Verdonck, 2023[14]). Therefore, security costs weigh heavily on municipal budgets despite the transfers from the Federal Authority.

As for investment, capital expenditure has shown a steady increase since 2017, although there was a noticeable drop in 2021, likely due to the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Despite this setback, investment expenses in Brussels-Capital Region municipalities have rebounded, reaching almost EUR 916 million, indicating a considerable surge of nearly 40% compared to the previous year. However, it is important to contextualise this growth at the regional level, as it is primarily driven by a large-scale investment project undertaken by the Brussels-Capital Region (Belfius, 2022[24]). The primary areas of investment for Brussels-Capital Region’s municipalities include general administration (such as administrative buildings), urban development and housing, sports and cultural infrastructure, education (i.e. school buildings) and, to a lesser extent, road infrastructure. Regarding financing, a significant portion of investments (approximately 74%) is secured through borrowing, while the region plays a crucial role by providing capital subsidies, accounting for about 22% of the funding (Belfius, 2022[24]).

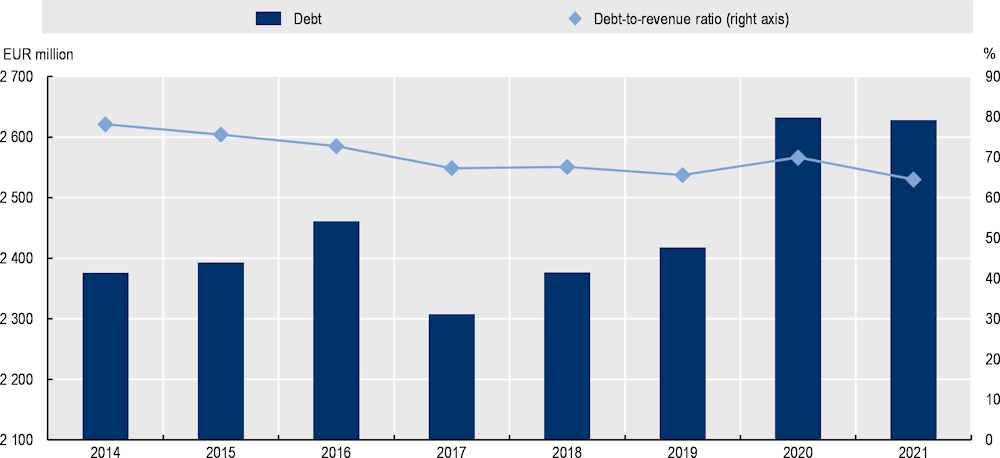

Finally, debt is not particularly worrying for municipalities subject to the golden rule (i.e. they are allowed to borrow for capital expenditures only). The debt-to-revenue ratio has evolved downward since 2014 with the exception of 2020 due to the pandemic crisis (Figure 4.14). However, the reduction of debt levels may stop or even be reversed if pension contributions start growing too big on municipalities’ budgets and the golden rule is lifted to finance them. This would only contribute to further endangering the fiscal sustainability of municipalities, placing a heavier burden on future generations.

Figure 4.14. Average debt level of municipalities

Source: NBB (2021[25]), Breakdown of Local Government, National Bank of Belgium, https://stat.nbb.be/.

The uneven distribution of tax revenue and transfers reveals fiscal and income disparities among municipalities

Based on the initial budgets for 2022, municipalities in the Brussels-Capital Region show levels of ordinary revenues to the amount of EUR 2.7 billion, reflecting a notable 6% increase from the previous year’s figures. This increase can be attributed to two primary factors: first, the introduction of new regional subsidies as part of the financing for the local personnel’s remuneration enhancement agreement, pushing transfer revenues upward by 14%, and second, a substantial rise in revenues from parking fees.

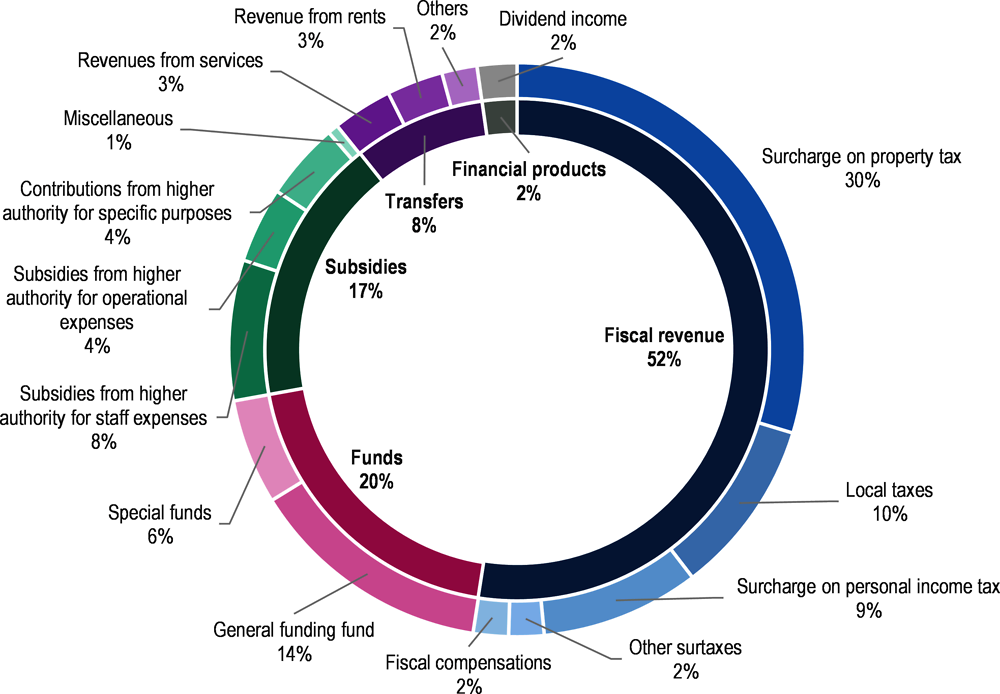

Municipalities receive their revenues from different sources (Figure 4.15). In 2022, over half of municipal revenues (52%) are tax revenues, which can be broadly classified into two main categories: municipal surtaxes and own-source municipal taxes. Municipalities can apply a surtax on property tax, personal income tax, traffic tax and the regional tax on tourist accommodation establishments. Surcharges on property tax and PIT account for 39% of all municipal revenues on an unweighted average. For municipal surtaxes, municipalities can determine the rate (although not the base) and the basic levying authority is responsible for the establishment and collection. In practice, however, the possibilities for creating new taxes are limited, as most taxable matters are already taxed by some level of government.

Own-source municipal taxes refer to a range of activities such as taxes on administrative services, public hygiene services, as well as industrial, commercial and agricultural undertakings. Municipalities have a larger margin of manoeuvre to determine the tax base, rate and eventual exoneration criteria. Despite having larger autonomy, they represent on unweighted average of 10% of total revenues as of 2022.

Figure 4.15. Revenue streams by category and sub-category for the municipalities

Source: Adapted from Belfius (2022[24]), Les finances des pouvoirs locaux de la région bruxelloise, https://research.belfius.be/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Finances-des-pouvoirs-locaux-de-la-R%C3%A9gion-bruxelloise-2022.pdf.

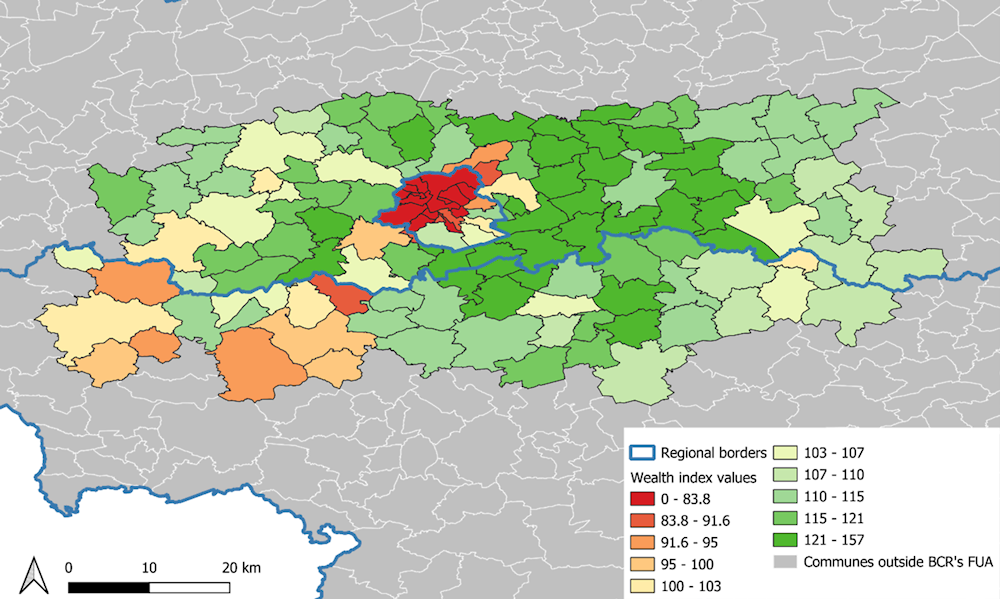

It is essential to highlight that the relative significance of each revenue source varies across municipalities based on their socio-economic characteristics. Figure 4.16 displays the wealth index value for all 138 municipalities in the Brussels functional area. A score below 100 indicates that the value is below the national average. An analysis of the map reveals two main findings. First, most municipalities located within Brussels-Capital Region have scores below 83 points, with a few municipalities in the southeastern regions having higher scores. Second, most of the Brussels-Capital Region’s neighbouring municipalities present high values above the national average, particularly the municipalities located to the east in both Flemish and Walloon territories.

This highlights the presence of territorial inequalities, where the population in Brussels-Capital Region is disproportionally disadvantaged with low levels of income compared to the wealthier populations living outside but, to a large extent, working in the Brussels-Capital Region. Commuters thus travel from the neighbouring municipalities to work in the Brussels-Capital Region (thereby reaping the benefits of Brussels-Capital Region’s infrastructure investments) but do not contribute to its finances through their tax payments on PIT or property tax, as they live outside the Brussels-Capital Region’s administrative boundaries. There are also intra-regional inequalities among municipalities, with the southern and southeast municipalities showing a higher level of income than those in the rest of the municipalities, especially the ones in the north (see Chapters 1 and 2). This also translates into different needs and preferences at the local level, for example, in terms of social welfare allocations.

Figure 4.16. Wealth index values for Brussels functional urban area at the municipality level

Source: Statbel (2020[27]), Revenus fiscaux, https://statbel.fgov.be/fr/themes/menages/revenus-fiscaux#figures.

To provide some context, in 2021, there were a total of 754 287 jobs in the Brussels-Capital Region, with 50.5% held by Brussels-Capital Region residents and 49.5% held by commuters (Actiris, 2023[1]). Essentially, approximately one out of every two jobs in the Brussels-Capital Region are occupied by a commuter (see Chapter 1). Around 300 000 commuters are employed by or within Brussels-based enterprises but cannot be taxed based on their income due to their residence status or the tax exemptions granted to EU civil servants. However, these workers benefit from the capital investments made by the Brussels-Capital Region. Simultaneously, the population within the Brussels-Capital Region is gradually experiencing increased poverty, leading to reduced revenue for the region. This situation leads to the structural underfunding of the region, wherein the available funds are insufficient to meet the growing demands for public services and investments in the region.

Wealth inequalities have significant implications for both expenditures and revenues at the local and, by extension, regional levels. On the expenditure side, municipalities with lower levels of wealth often require additional funding to provide essential public services such as healthcare and social welfare assistance through their PCSWs. Moreover, they may face challenges in implementing necessary infrastructure investments, such as building adaptations and environmental initiatives. In terms of revenue, the combination of a less affluent population and the inability to levy taxes on both commuters and international civil servants results in insufficient tax revenues, notably income tax. This shortfall in tax income makes it difficult to cover the costs associated with public services and infrastructure that are utilised by both residents and non-taxable individuals (i.e. commuters and international civil servants).

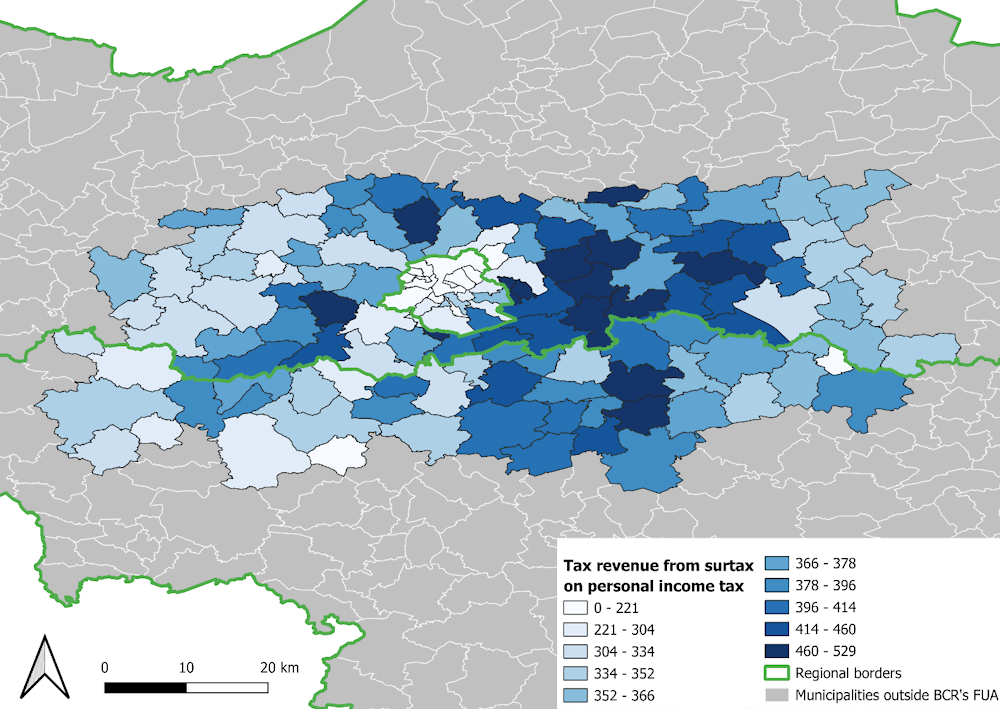

Figure 4.17. Surtax on PIT by municipality in the Brussels functional urban area

Note: In million EUR.

Source: Based on data from Statbel (2020[27]), Revenus fiscaux, https://statbel.fgov.be/fr/themes/menages/revenus-fiscaux#figures.

Although total tax revenue is higher in most of Brussels-Capital Region than in the rest of the metropolitan area, the surtax on PIT is practically insignificant in the less affluent municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region (Figure 4.17). Indeed, while taxation remains the primary financing source, its proportion in the total revenues fluctuates between 45% for the northern municipalities and 65% for the residential municipalities of the southeast, where higher income levels and, consequently, higher taxable bases are prevalent. This fiscal variation can be explained, at least partly, by the socio-economic characteristics of each municipalities’ tax bases.

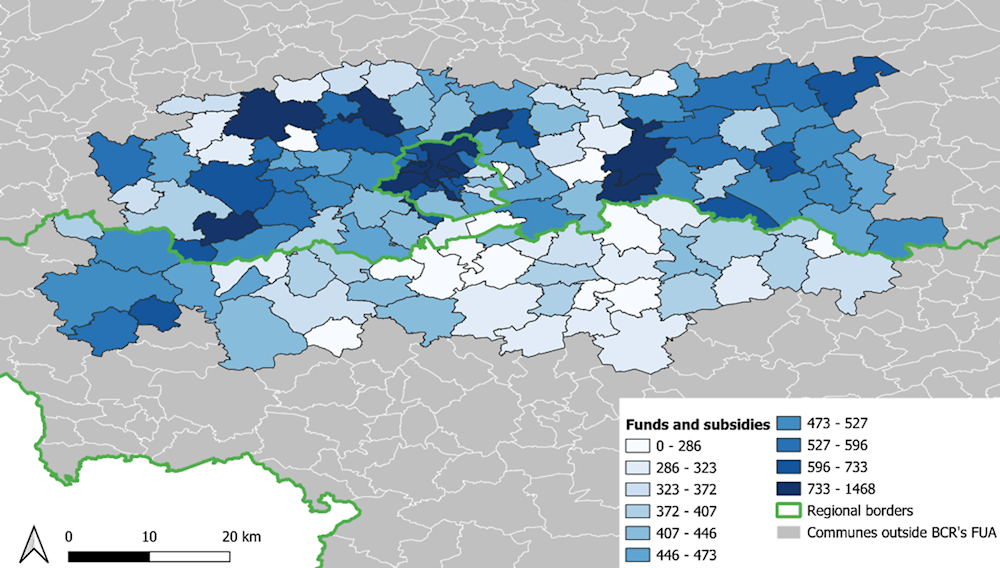

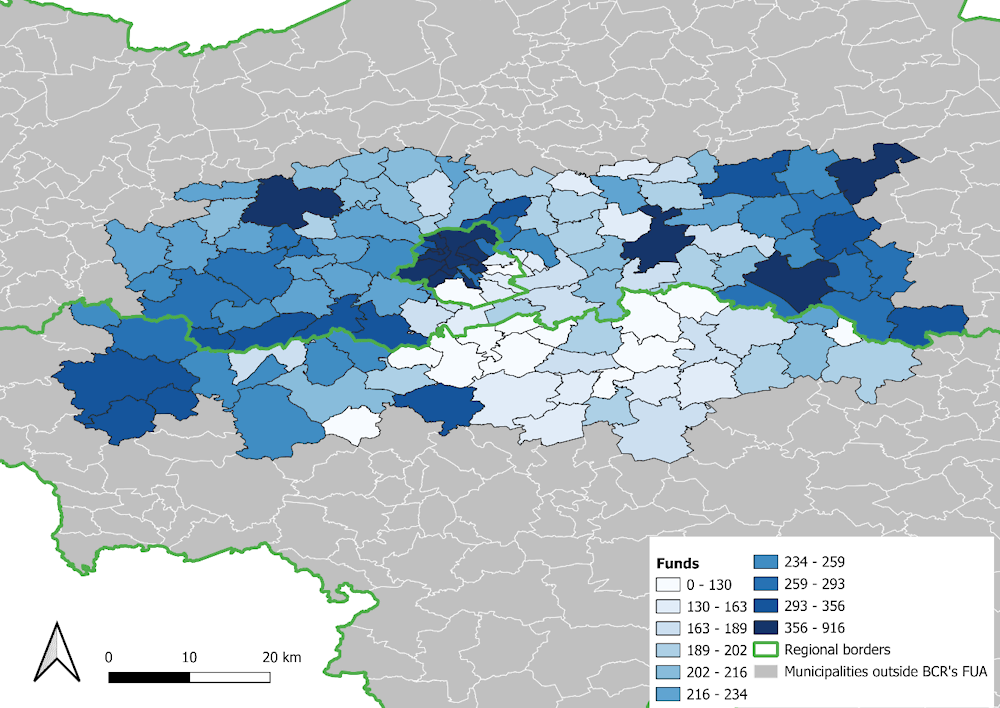

On the other hand, the General Grant to the Municipalities (GGM) plays a crucial role in fiscal equalisation, accounting for 26% of all revenues in the northern municipalities while comprising only 8% in the residential municipalities of the southeast. Apart from general and special funds, operating subsidies have also registered a sizeable increase in order to finance the sectoral agreement (as well as adapting to inflation depending on the type of subsidy). Figure 4.18 shows the uneven geographic distribution of aggregated revenue from subsidies and funds. When separated, funds are practically inexistent in the southeastern municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region (Figure 4.19).

The uneven increase in the size of transfers for funding expenses across municipalities underlines the importance of equalising mechanisms such as the GGM, whose allocation criteria are being discussed to better account for the fiscal potential of each municipality (Box 4.5).

Figure 4.18. Revenue from funds and subsidies by municipality in the Brussels functional urban area

Note: In million EUR.

Source: Based on data from Statbel (2020[27]), Revenus fiscaux, https://statbel.fgov.be/fr/themes/menages/revenus-fiscaux#figures.

Figure 4.19. Revenue from funds by municipality in the Brussels functional urban area

Note: In million EUR.

Source: Based on data from Statbel (2020[27]), Revenus fiscaux, https://statbel.fgov.be/fr/themes/menages/revenus-fiscaux#figures.

Box 4.5. Towards a new General Grant to the Municipalities (GGM)?

The GGM is a system of financial transfers from the federal government to the municipalities in the Brussels-Capital Region. It intends to provide the municipalities with financial support for their administrative and operational expenses. The sixth state reform brought about several changes to this system:

Increase in its amount: The sixth state reform involved the transfer of additional responsibilities from the federal government to the regions and municipalities. With these new responsibilities came additional financial burdens. As a result, the dotation system was modified to account for the increased funding requirements associated with these transferred responsibilities.

Differentiated allocation criteria: The reform introduced changes in the allocation criteria for the general grant. Factors such as population size, poverty factors, specific challenges faced by the municipalities and demographic considerations were taken into account in determining the allocation of funds.

Greater regional autonomy: The changes to the general grant system also aimed to provide the Brussels-Capital Region with increased fiscal autonomy. This allowed the region to have more control over the allocation and management of the funds received through the general grant system.

The GGM represents around 55% of the total amount for transfers to municipalities. It is also the second funding source after the surtaxes on property tax.

The financial support to the municipalities has been significantly enhanced through several key measures. First, an additional transfer of EUR 30 million has been allocated to bolster their funding. Furthermore, a separate transfer of EUR 3 million has been specifically earmarked for the Joint Community Commission to support the financing of the PCSWs. These initiatives have resulted in a substantial increase in the overall budgetary mass, with a structural growth of 12%. Additionally, to ensure the sustainability of this increased support, the budget has been indexed annually by 2%.

Source: Belfius (2022[24]), Les finances des pouvoirs locaux de la région bruxelloise, https://research.belfius.be/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Finances-des-pouvoirs-locaux-de-la-R%C3%A9gion-bruxelloise-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023); OECD (2023[12]), “Questionnaire to the Brussels-Capital Region”, OECD, Paris.

Growing expenditure and insufficient revenue have placed 10 out of the 19 municipalities in a negative budget balance

According to law, municipalities cannot incur a deficit. However, with expenditures increasingly higher, in practice, several municipalities have moved into deficits. When that happens, the Brussels Regional Fund for Refinancing Local Treasuries (BRFRLT) acts as the regional agency responsible for redressing the deficits of municipalities. The BRFRLT is entrusted with three essential missions. First, it can grant loans to support the financial recovery of local authorities within a financial recovery plan. Second, it actively intervenes as a “financial co-ordination centre” with local authorities to assist them in their financial endeavours. Lastly, the BRFRLT plays a crucial role in providing long-term loans for financing municipal investments. These missions underscore the vital role of the BRFRLT in contributing to the development and financial stability of the local authorities in the region.

Municipalities that no longer comply with the budgetary balance rule and face structural cash flow difficulties can seek assistance from the BRFRLT, which then grants potentially non-repayable loans. The financial recovery plan for local authorities undertaken by the BRFRLT encompasses all operations related to financing local authorities experiencing financial difficulties. Additionally, the BRFRLT contributes to the rationalisation and better co-ordination of the activities of local authorities. The main objective of the financial recovery plan is for the municipality to rebound and re-establish its budgetary balance without needing any more assistance in the future.

Since 1993, the fund has intervened in 11 municipalities with such financial recovery plans. Recently, there have been 10 (and soon 11) municipalities under a financial recovery plan. Loans from the BRFRLT can be used for specific projects and offer valuable assistance and, if they adhere to the plan, municipalities are exempt from repaying the debt. Among the ten municipalities under a financial recovery plan, some are in a healthier situation than others.

The major problem of these financial recovery plans has been that municipalities benefitting from them have successfully restored budgetary balance for a short period but have often fallen back into deficits soon after the financial aid from the BRFRLT stopped. The possibility of going from one financial recovery plan to another may have fostered the perception among municipalities that the budget balance rule is a soft fiscal rule and that the BRFRLT can act as a safety net every time they incur in a deficit.

Enhancing public finance in the Brussels-Capital Region at the regional, local and metropolitan levels

Considering the assessment provided in the section above, the following section delves into the primary challenges confronted by the Brussels-Capital Regions’ municipalities and presents four policy recommendations. Each recommendation is introduced by a brief summary of the main challenges justifying the rationale for said recommendation and is accompanied by a series of policy actions, following the model already used in Chapter 3.

Policy recommendation 1: Better cover the additional costs in the Brussels-Capital Region

Challenges

Over the past decade, the Brussels-Capital Region has experienced a substantial increase in its expenditures. This upward trend has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery policies as well as the inflationary pressures stemming from the effects of Russia’s large-scale war of aggression against Ukraine on energy prices, among others. Consequently, the region has faced a rapid deterioration of its budget balance and a surge in debt levels, especially since 2016. Similar to the other Belgian regions as well as other EU regions, the population aged 65 or more in Brussels is expected to increase by 11.8% between 2020 and 2030, and to continue doing so at least until 2070, a year when this segment of the population will have grown by 82% compared to 2020. This increase is already manifesting itself unevenly across municipalities, with those with the largest shares of elderly people also being in a more precarious fiscal state. The expected increase in people aged 65 or more will push social expenditure and the demand for public services for the elderly (e.g. care homes) upward, unequally across municipalities (Observatory of Health and Social Affairs in Brussels, 2023[28]). These challenges present a significant obstacle to maintaining long-term fiscal sustainability at the regional and local levels.

Although tax revenue has shown a gradual increase in nominal terms since 2010, compensation transfers, including those related to the National Solidarity Mechanism, the allocation for the presence of commuters and the allocation for the presence of international civil servants, appear to fall short of covering the region’s growing expenses. These expenses are primarily linked to staff remuneration, pension obligations and transfers to municipalities.

Furthermore, while Belgium already stands out as a federal country with a relatively small equalisation transfer system, the impending disappearance of the National Solidarity Mechanism by 2025 further exacerbates this challenge as it deprives the Brussels-Capital Region of the budget certainty required to commit to much-needed investment projects.

Policy actions

To ensure better funding of the increasing expenditures of the Brussels-Capital Region, there are a few policy actions can be undertaken.

To start with, the Brussels-Capital Region should actively initiate and advocate for the organisation of a Federal Conference on the Additional Financing of the Brussels-Capital Region that would bring together all of the key governmental stakeholders as well as technical staff to discuss the funding system of the Brussels-Capital Region. The primary objective of this conference would be to collaboratively explore and devise innovative approaches to address the escalating financial needs of the Brussels-Capital Region. By engaging all relevant actors (i.e. the Federal Authority, the regions and the municipalities, among others), this conference would, first, provide a strong message that it is in the interest of all parties to ensure the vibrancy and sustainability of the Brussels-Capital Region and its metropolitan area. The conference could facilitate discussions and knowledge-sharing on new financial models, fiscal policies and revenue-generation strategies that can sustainably cover the region’s increasing costs with the co‑operation of other relevant governmental actors. This forum should foster constructive dialogue and encourage the adoption of co-ordinated financial solutions. If the outcomes of this body are successful, this could be maintained as a regular platform for exchange, ensuring that there is no duplication with other institutions, such as the High Council of Finance or the ones mentioned in Chapter 3.

Within this conference or outside its framework, the Federal Authority and the regions should design a system of long-term compensation transfers rooted in a shared diagnostic analysis providing a consolidated view of the region’s financial challenges and should incorporate agreed-upon indicators to assess the financial health and sustainability of the Brussels-Capital Region. These indicators may include, broadly, population growth, economic development as well as infrastructure needs. The compensation transfers should be designed to ensure a fair and equitable distribution of funds from the federal government as well as the regions, taking into account the benefits they gain from their proximity to an economically dynamic region such as the Brussels-Capital Region.

Complementing existing or new funding sources with spending reviews can help better monitor and rationalise expenses, thus maintaining a steady budget trajectory. Formally embedding spending reviews in the budget process with the preparation of the budget ordinance for the upcoming fiscal years, as is expected to happen in the coming years, would ensure a critical appraisal of public expenditure and identification of areas of inefficiency while enhancing transparency and accountability. This would be an especially useful exercise in the context of the high level of public spending in Belgium and taking account of the necessary consolidation of public finances in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis. Spending reviews can also help adapt expenditure priorities to changing economic conditions or emerging challenges, and contribute to detecting risks to the fiscal sustainability of the region, such as long-term care and population ageing, shedding light upon evidence-based plans to tackle them (Comité d’Étude sur le Vieillissement, 2023[26]; EC, 2023[20]).

In terms of data management, all institutions within the Brussels-Capital Region should join and establish a centralised hub for public finance. This hub should serve as a single point of access where regions, communities and, ideally, all municipalities can collaborate in sharing and synchronising their data. Such an approach would facilitate a comprehensive understanding of financial trends across diverse regional contexts and would mitigate any redundancy in data collection and analysis efforts.