Economic regulators play an important role in the achievement of social, economic and environmental goals in utility sectors. Their work helps ensure the efficient delivery of essential services such as energy, e-communications, transport and water. They bring stability, predictability and confidence to markets that are constantly evolving, and occupy a unique position among consumers, operators and government. Often set up as independent bodies, their governance is extremely important, including their resourcing. Staff and budget arrangements can make or break economic regulators’ performance and affect their autonomy, agility, accountability, transparency, ability and capacity.

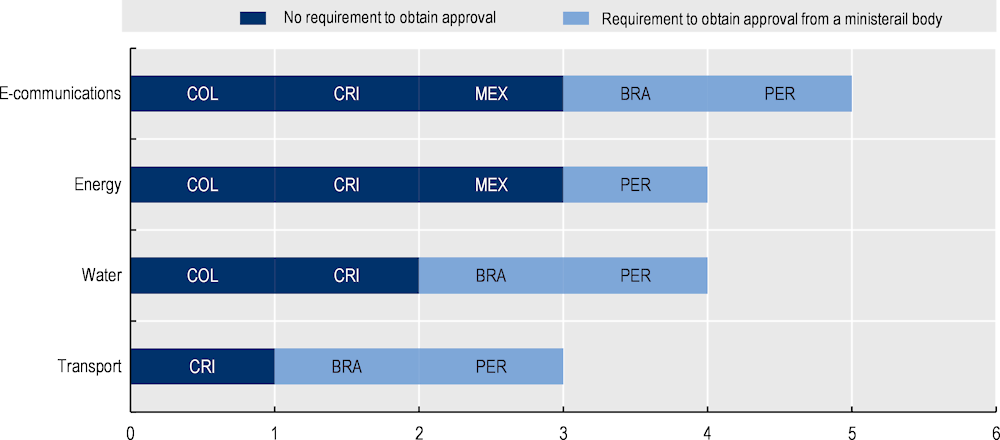

Economic regulators rely on the expertise and skills of their staff to provide evidence-based analyses to underpin their regulatory decisions. They need to recruit the right staff to respond to changing expectations and roles, as digital and energy transitions and crises transform utility sectors. However, in practice, economic regulators may face constraints on their ability to recruit staff autonomously (OECD, 2022). Seven out of the 16 economic regulators surveyed in Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries (44%) need to obtain approval from a ministerial body prior to hiring (Figure 5.12). This could potentially complicate their work, especially if such requirements prevent a regulator from hiring the staff numbers required to fulfil all functions or if they make it more difficult to fill positions in a timely way.

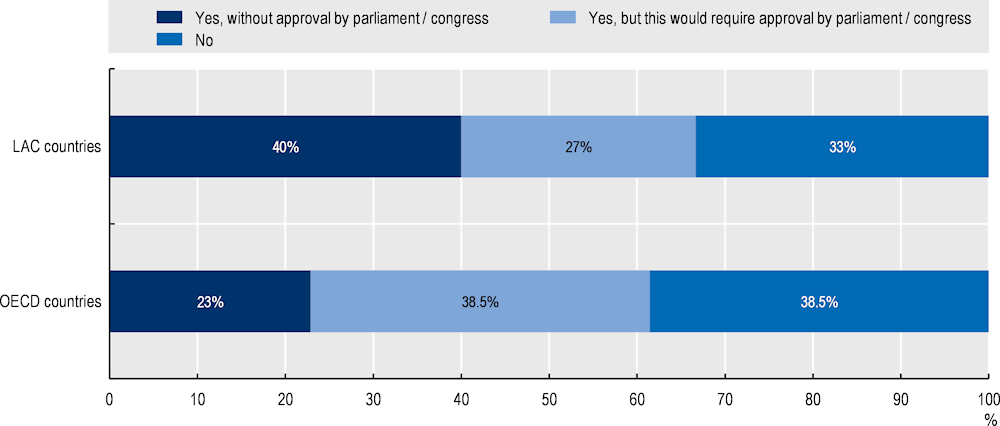

Predictable funding allows economic regulators to plan ahead and safeguard their independence. The budget appropriation process is one place where undue influence may be present. Secure multi-year funding arrangements can contribute to the independence of a regulator by protecting it from politically-motived budget cuts in reaction to unpopular decisions (OECD, 2014). For most economic regulators, changes to their budget after initial approval are not allowed or require approval from the legislature. Among OECD countries, the executive can make such changes under certain circumstances without oversight by the legislature for only 23% of the surveyed regulators. The share is higher in LAC countries, where 6 out of the 15 surveyed regulators (40%) face potential changes to their approved budget without the approval from the legislature (Figure 5.13). Insufficient checks and balances on changes to the economic regulator’s budget could threaten the sufficiency of funding and thereby reduce the regulator’s capacity.

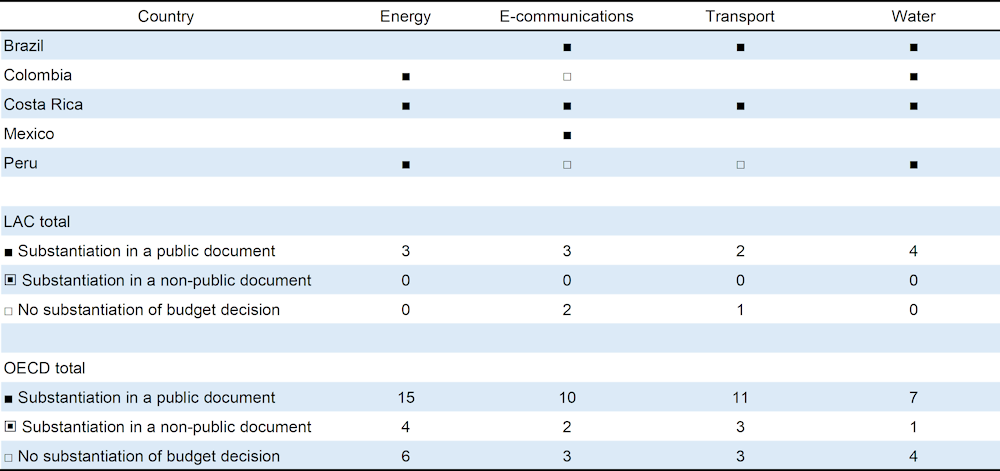

Transparency over the allocation and use of public resources can empower society to hold public bodies to account. Such information can increase confidence that funds are being spent in the right way to deliver value for money. LAC countries frequently show good practice, supporting accountability by explaining decisions about economic regulators’ budgets. For 12 out of the 15 surveyed economic regulators in LAC countries (80%), the public body that sets the regulator’s budget explains the decision on the budget allocation. This is the case for only 62% of regulators in OECD countries (Table 5.2).