Valerie Frey

Modernising Access to Social Protection

1. Modernising access to social protection for the challenges ahead

Abstract

This chapter presents the motivation and findings of the report Modernising Access to Social Protection: Strategies, Technologies and Data Advances in OECD Countries. Many OECD countries face challenges in identifying everyone in need of social programmes, enrolling them in the appropriate programmes, and delivering the support they need. Complex entitlement rules, cumbersome application processes and information gaps have led to high rates of non-take up in key social programmes even when they are statutorily well-designed and adequately funded. This chapter presents an overview of coverage gaps and the challenge of non-take-up in OECD countries, and discusses how ongoing advances in digital technologies and data are helping to make social protection more accessible to those who need it.

Key findings of the report

Many OECD countries face challenges in identifying households in need of social benefits and services, enrolling them in the appropriate programmes, and delivering the support they need. Complex entitlement rules, information gaps and cumbersome application processes can lead to high rates of non-take‑up in key social programmes even when these programmes are well-designed and adequately funded. Well-executed advances in digital technologies and data can go a long way towards making social protection more accessible for everyone who needs it.

Social programme coverage gaps and non-take‑up are problematic across OECD countries

Government and academic research illustrate gaps in coverage and take‑up of social programmes. In France, for example, around 34% of households eligible for the minimum income benefit, Revenu de solidarité active (RSA), do not receive it each quarter, and in the United States, around 20% of eligible families do not benefit from the Earned Income Tax Credit – the country’s largest poverty alleviation programme for families with children. These are sizeable gaps in take‑up, with potentially large financial implications for households. Importantly, people with low resources are the least likely to respond to simple behavioural interventions encouraging them to enrol in social programmes (Chapter 2).

OECD governments are investing in national strategies to identify and reach those in need

Data‑informed, national strategies against poverty or social exclusion aim to increase the reach of social protection for vulnerable groups. These strategies often include an explicit target of minimising non-take‑up among likely potential beneficiaries (Chapter 3).

National strategies take a range of approaches. Many countries, including Ireland and Spain, apply what might be considered a more traditional approach to identifying vulnerable groups and regions in need of social programmes, based on probabilistic estimates of (usually de‑identified) survey and administrative data. Once coverage gaps are identified, the policy response casts a wide net, including better communication and investment in new programmes. Public outreach and communication campaigns frequently target a particular benefit, a specific disadvantaged group or geographic area. This approach is particularly useful for reaching people whose personal data may not be known by the state, such as undocumented residents, informal workers or people experiencing homelessness (Chapter 3).

A few countries, including Belgium, Chile, Estonia and France, are increasingly linking administrative data to enable the identification of social benefit eligibility at the individual level. Spain is also taking a step in this direction with the roll-out of its Digital Social Card. Data linking usually happens with a unique personal identifier across different agencies or through a social registry (Chapter 3).

Countries are leveraging advances in technology and data to improve coverage and delivery

Better data and the smarter use of data sit at the heart of governments’ increased reliance on technology to improve policies and services. Particularly noteworthy are linked administrative databases, shared across agencies, which can 1) be used to measure non-take‑up; 2) help close information gaps (e.g. eligible households can be directly encouraged to apply) and 3) lower the administrative burden on users (e.g. by pre‑filling information from administrative sources). In a handful of programmes, such as child benefits in a few countries, linked data are being used to enrol users automatically into programmes (Chapters 3 and 4).

Digitalised benefit systems are changing the nature of the relationship between the state and individuals. Most services are now available online. While this presents barriers for some users, it should also enable agencies to focus human resources on people who find it difficult to access automated systems – often people with complex needs, or those with limited access to (or familiarity with) digital resources, such as older people.

In some ways, OECD governments are only at the beginning of digital transformation in social protection. Advanced uses of technology and data are less common in the public sector than in the private sector, and less common in social policy than, for example, in the healthcare sector. While government agencies are increasingly making use of administrative data, they are yet to exploit, in a systematic way, the value of data from sources outside government to understand and shape social policy and services.

Many uses of advanced technology, including intelligence (AI), continue to be small, ad hoc test cases to determine feasibility, functionality and scope for deployment. Countries are thinking carefully about how to take advantage of new technologies and proceeding with caution, implementing and evaluating small-scale projects before determining whether to take them to scale. Several countries, however, are implementing comprehensive change programmes that involve modernising their technology platforms, changing operating models and ensuring the necessary cultural shifts to revolutionise how public services are provided.

The use of AI in social protection remains limited, apart from the use of AI-powered chatbots that provide information to clients, automating back-office processes, and fraud detection. Thus far, other methods remain more common in automated decision-making and data analytics. Several countries are exploring the scope of AI for the future of social protection, including for assessing eligibility for social programmes, providing information to users, adjusting benefits, and monitoring benefit delivery (Chapter 4).

Modernising social protection – with guard rails

Leveraging advances in technology and data comes with challenges and risks. Challenges include ensuring the foundations that underpin and enable technological improvements are in place, that there is sufficient cross-governmental collaboration, and that people’s privacy is protected when using their data. Governments must also manage the risks associated with discriminatory biases being built into automated processes and decision making, which have the potential to reinforce or create new sources of exclusion and disadvantage.

These challenges require risk mitigation with instruments like legal and regulatory frameworks. Governments are also going beyond these instruments, implementing initiatives that improve their overall interactions with individuals and communities, enhance public trust and confidence, and modernise the way they do business. This includes offering services through multiple channels, involving service users in design, achieving incremental improvements through agile working methods, and encouraging innovative technology and data cultures (Chapter 6).

1.1. The need for accessible and responsive social protection systems

In the face of major sociodemographic, labour market and climate‑related megatrends, social protection systems in OECD countries are well prepared in some ways, but less prepared in others. OECD countries spend more on social protection than most countries in the world, with relatively high coverage, and social protection is generally designed to support people through their entire life course. This has resulted in relatively low poverty rates in the OECD in global perspective, ranging from 6‑7% of the population (in Czechia, Denmark and Finland) to 18‑21% (in the United States and Costa Rica) (OECD, 2024[1]), as well as relatively high life expectancy (80.3 years at birth) on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2023[2]).

At the same time, OECD countries face longstanding structural challenges that contribute to gaps in social protection. These include strained government budgets, the continued exclusion of some groups (such as many non-standard and undocumented workers) from statutory access to social protection, and – in many cases – poor accessibility to, and delivery of, social benefits and services among those who are eligible.

Gaps in social protection coverage weaken the ability of governments to provide timely and well-targeted support to people in need, including those experiencing income instability, persistent poverty or social exclusion. These challenges also hinder governments’ ability to adjust support to changing macroeconomic conditions; for example, providing work incentives and activation support is more important, and effective, in tight labour markets. The experience of the COVID‑19 pandemic shows that broadly accessible social protection programmes can be insufficiently responsive to needs on the ground, and responsive programmes can be inaccessible.

This report explores how governments can better identify people who may need support, and how to use technology and improved data collection, analysis and linking to ensure that social programmes (services and benefits) are adequately accessible and responsive.

This report focuses on three primary challenges in social protection systems, within the broader goal of improving social protection coverage:

The identification of the population (potentially) in need of benefits or services, using probabilistic estimates derived from surveys or administrative data held by government (Chapters 2, 3);

Improving the take‑up of social protection, i.e. the enrolment of beneficiaries to receive services and benefits for which they are eligible (Chapters 2, 3, 4);

Improving the delivery of services and benefits, i.e. facilitating the observed coverage and transfer of social benefits and/or services to eligible beneficiaries, with a particular focus on new sources of data and the use of digital tools (Chapter 4).

These policy findings accompany a discussion of the measurement and causes of non-take‑up of social programmes (Chapter 2). The report concludes with a discussion of the risks and benefits of new digital and data approaches to improve access to social protection, including artificial intelligence (Chapter 5).

1.2. Coverage gaps persist in social protection

Many people in OECD countries are not receiving the social benefits or services they need. The reasons are layered and sometimes overlapping:

Gaps in social protection coverage can emerge from the stringency of de jure eligibility criteria. People who do not meet certain income, age, residency, family size, or (prior) contribution thresholds, for example, may not be eligible for specific benefits or services.

People who are eligible by statutory socio-economic rules may be excluded (or see their benefits or services reduced or suspended) because they do not meet the behavioural conditions required to receive a service or a benefit. For example, in most countries, unemployed workers seeking unemployment benefits or a space in public childcare are required to demonstrate that they are looking for a job. Minimum income cash transfers are sometimes conditional on parents ensuring their child’s regular school attendance or participation in regular health check-ups. While sanctions are a design feature of many targeted social protection programmes, and are often important for meeting policy objectives, behavioural requirements that are overly harsh or poorly aligned with potential recipient groups may unduly harm coverage.

Not all social programmes in OECD countries are rights-based, and a lack of adequate funding may mean that individuals cannot access the benefit or service despite being eligible. They may be encouraged to re‑apply later or be waitlisted, as is the case in some means-tested social housing programmes or childcare programmes.

Finally, even when potential beneficiaries are eligible, they meet conditionality requirements, and funding is sufficient, people may not apply for programmes or re‑enroll in them. Barriers to take‑up include unclear or complex information, “hassle costs” around applying, stigma around receiving a public benefit or service, and low expected benefits (Chapter 2).

Poorly designed programme applications and benefit/service delivery can reduce coverage by making it harder for people to take up benefits or services. Applications and renewals may be unwieldy, time‑intensive, and require a high degree of knowledge. Claiming benefits may involve in-person appointments that require time off from work or may be difficult to reach by claimants with mobility constraints. On-line claims may similarly be inaccessible for those who lack online access or digital skills.

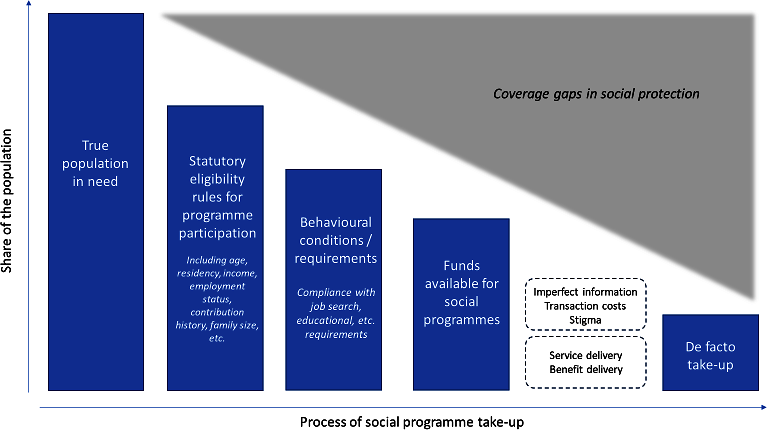

These compounding, structural barriers are outlined in Figure 1.1. This simple illustration shows how the share of the population covered by social protection decreases at various stages due to statutory eligibility rules, behavioural conditions, adequacy of funding, and enrollment processes. Even in more universalistic programmes – i.e. programmes available to everyone within a given jurisdiction – potential beneficiaries can be missed.

Figure 1.1. Social protection coverage gaps emerge due to eligibility criteria, budget constraints, barriers to enrolment and ineffective service delivery

Stylised model of barriers to social programme enrolment contributing to coverage gaps in the population in need

Source: OECD Secretariat, 2024.

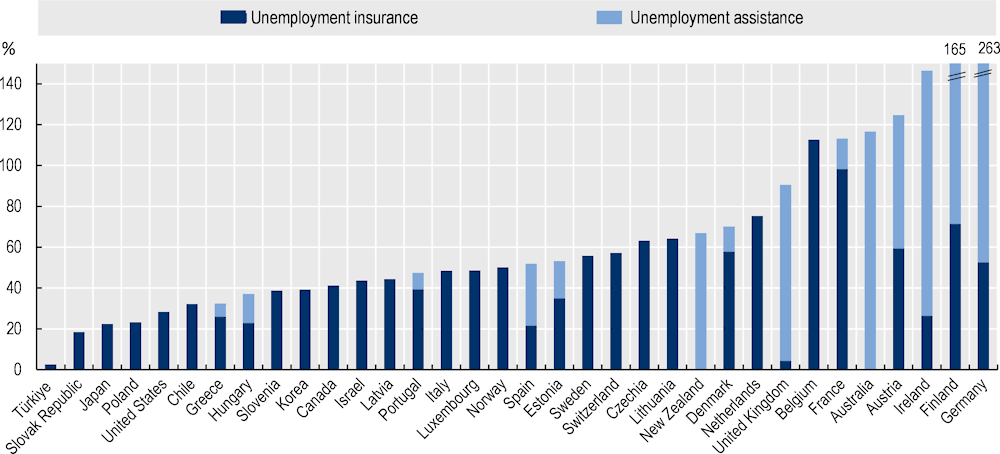

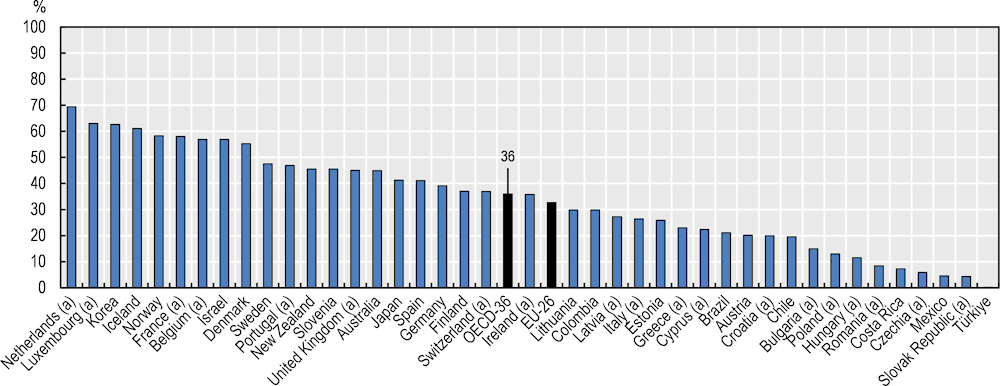

Descriptive evidence illustrates some of the challenges around social protection coverage. Cross-national estimates suggest that in many OECD countries, only half of all jobseekers receive unemployment support (Figure 1.2), and fewer than four in ten young children are enrolled in formal early childhood education and care (Figure 1.3), even as care obligations represent a significant barrier to parents’ (particularly mothers’) labour force participation.

1.2.1. The coverage of unemployment benefits

In most OECD countries, a significant share of unemployed workers do not receive unemployment benefits. Figure 1.2 shows pseudo-coverage rates of unemployment insurance and unemployment assistance payments, defined as the recipients of unemployment insurance and assistance from administrative data (numerator) as a share of the unemployed (jobless, available for work and actively looking for a job in the denominator) from labour force surveys. These pseudo-coverage rates are an approximation because recipients of unemployment benefits are not necessarily unemployed according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) definition. For example, they may not be actively looking for a job (e.g. discouraged workers), or they may not be available for work because they are waiting to be recalled by a former employer. This also explains why the pseudo coverage rates can exceed 100% (OECD, 2018[3]).

Pseudo-coverage rates range from below 30% in Türkiye, the Slovak Republic, Japan, Poland and the United States to 80% and over in the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Australia, Austria, Ireland, Finland and Germany. Contribution-based unemployment insurance programmes can be inaccessible for labour market entrants and for those with patchy employment histories, as well as for the long-term unemployed as they are typically time‑limited. Indeed, countries that only provide means-tested job-seeker assistance (e.g. Australia), as well as those that combine insurance‑based benefits with means-tested support, such as the United Kingdom, Finland or Germany, reach higher coverage (Figure 1.2). However, Belgium also achieves a high coverage rate with an exclusively contribution-based system, although unemployment benefits are not time limited in Belgium.

Figure 1.2. Unemployment benefit coverage is low in some countries

Recipient numbers of unemployment insurance and assistance payments from administrative sources, in percentage of ILO unemployed workers, 2018

Note: The numerator is the number of beneficiaries of unemployment insurance and assistance benefits from administrative sources. The denominator is the number of ILO unemployed workers (jobless, available for work and actively looking for a job). These rates are commonly referred to as “pseudo” coverage rates as the population in the numerator and denominator may not fully overlap. For instance, in some countries, significant numbers of people who are not ILO unemployed may be able to claim benefits categorised under the unemployment heading in SOCR data provided by countries. As a result, pseudo-coverage rates can exceed 100% (e.g. Australia, Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, and Ireland). On the other hand, some unemployed are not entitled or do not claim unemployment benefits.

Source: OECD SOCR Database (http://oe.cd/socr); see www.oecd.org/social/recipients.htm for full notes.

1.2.2. Availability of public childcare

The availability of public childcare also illustrates the challenge of providing sufficient coverage to reach economic and societal goals like full employment and gender equality. A good supply of high-quality, affordable childcare is crucial to enable parents to engage in labour markets – especially mothers, who tend to shoulder higher unpaid care obligations. On average across 27 EU countries, 26% of inactive women aged 25‑to 54 years report that their main reason for not seeking work is to care for children or adults with disability;1 among men, 4% point to care obligations as the main reason for inactivity. In the same sample, 26% of women (and 6% of men) working part-time report that they work part-time to care for children or adults with a disability (Eurostat, 2022[4]).

Yet fewer than four in ten young children (under the age of three) are enrolled in formal early childhood education and care (ECEC) across OECD countries. Figure 1.3 includes children in both public and private childcare; looking only at public provision would produce even lower estimates of participation. These gaps happen even as some countries (e.g. Germany) offer a legal entitlement to parents to receive a childcare space.

To note, these are imprecise estimates of unmet demand. Not every parent wants their child under age three in formal childcare, and the value of enrollment would unlikely reach 100% even if there were adequate supply.

Figure 1.3. Fewer than four in ten young children are enrolled in early childhood education and care

Percent of children enrolled in early childhood education and care services (ISCED 0 and other registered ECEC services), 0‑ to 2‑year‑olds, 2020 or latest available

Notes:

a. Data for Belgium, Czechia, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, and the United Kingdom are OECD estimates for 2020 based on information from EU-SILC. Data refer to children using centre‑based services (e.g. nurseries or day care centres and pre‑schools, both public and private), organised family day care, and care services provided by (paid) professional childminders, regardless of whether or not the service is registered or ISCED-recognised.

Data generally include children enrolled in early childhood education services (ISCED 2011 level 0) and other registered ECEC services (ECEC services outside the scope of ISCED 0, because they are not in adherence with all ISCED 2011 criteria). Data for Costa Rica, Iceland and the United Kingdom refers to 2018, for Japan to 2019. Potential mismatches between the enrolment data and the coverage of the population data (in terms of geographic coverage and/or the reference dates used) may affect enrolment rates. For details on the ISCED 2011 level 0 criteria and how services are mapped and classified, see OECD Education at a Glance 2022, Indicator B2 (www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance-19991487.htm). For Japan, data refer to children using centre‑based services (e.g. nurseries or daycare centres and pre‑schools, both public and private), organised family day care, and care services provided by (paid) professional childminders, regardless of whether or not the service is registered or ISCED-recognised.

Source: OECD Family Database, Indicator PF3.2 (www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm).

1.3. Barriers to take‑up persist

This report focuses on improving the identification of groups in need, the take‑up of social programmes by potential beneficiaries (given statutory rules of benefit eligibility), and how modernising social protection systems can improve access to benefits and services.

The formidable issues of gaps in social protection related to de jure exclusion and insufficient funding are not analysed here. While these will continue to present significant challenges in the years ahead, there is much that OECD governments can do now to improve coverage for people who should already be enrolled in social programmes, based on eligibility criteria.

In France, for example, around 34% of households eligible for the national minimum income benefit, Revenu de solidarité active (RSA), do not receive it each quarter. In the United States, around 20% of eligible families do not benefit from the Earned Income Tax Credit, the country’s largest poverty alleviation programme for families with children; this is driven by non-filers and by not claiming (via additional documents) among those who do file. These are sizeable gaps with potentially large financial implications for households. Unclear or complex information, high hassle costs, stigma around receiving a public benefit or service, and low expected benefits are well-recognised barriers to social programme take‑up (Chapter 2).

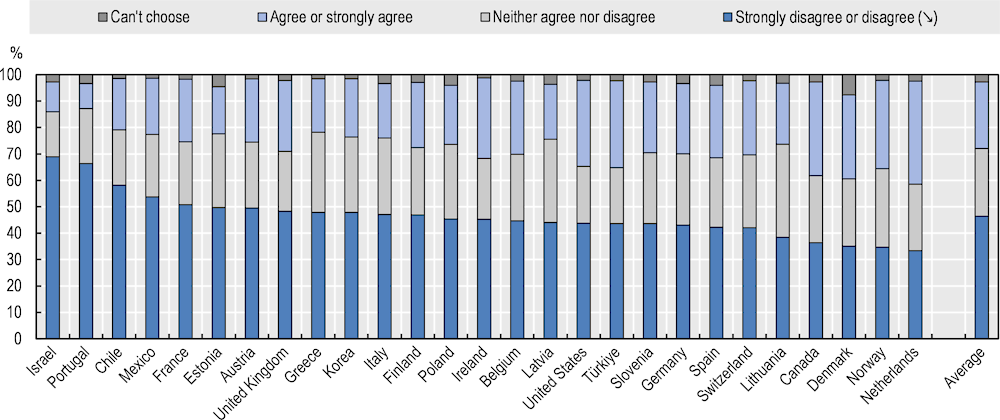

These low take‑up rates, and the well-recognised barriers to take‑up, correspond with public perceptions of access to social protection. Across OECD countries there is widely-held skepticism around the ease of applying for – and obtaining – public benefits. On average across 27 OECD countries in the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter (RTM) survey, nearly half of respondents (46%) do not think that they could easily receive benefits in time of need. Even in the most optimistic country – the Netherlands – only 39% of respondents say that they could easily receive public benefits if needed (Figure 1.4). Skepticism is even higher among those who feel economically vulnerable (Figure 2.7 in (OECD, 2023[5])).

Figure 1.4. Fewer than half feel they could easily receive public benefits if they needed them

Proportion of respondents who agree or disagree with the statement: “I feel that I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them”, by country, 2022

Note: Data are sorted by the variable marked with an arrow (↘) in the direction of the arrow. Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement? If you currently are receiving services or benefits, please answer these questions according to your experience. If you are not receiving them, please answer according to what you think your experience would be if you needed them: I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly agree” or “agree”, and “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, respectively. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: (OECD, 2023[5]), Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey, https://doi.org/10.1787/70aea928-en.

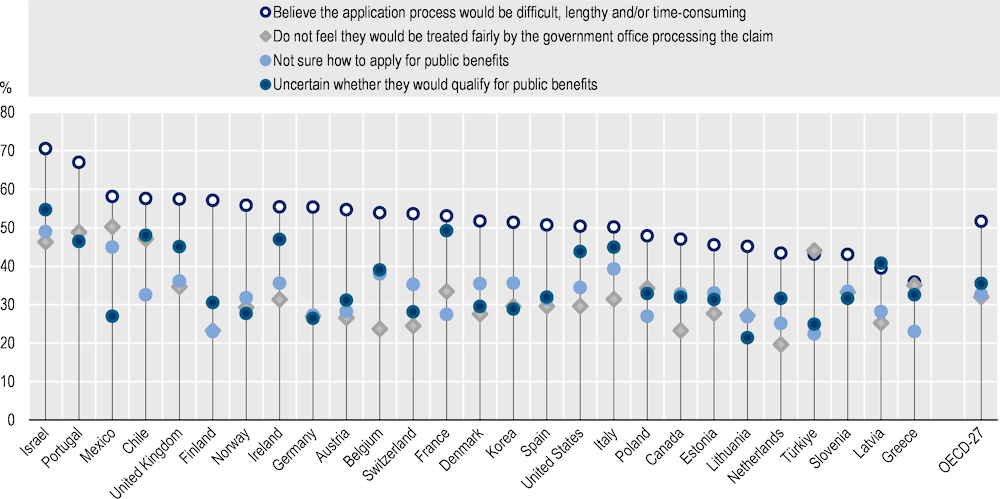

Related to these concerns around accessibility, people are also pessimistic about the ease of applying for social programmes. 52% of respondents to RTM 2022 say they believe the application process for public benefits would be difficult and lengthy (Figure 1.5). 36% are uncertain that they would qualify for benefits, 33% are not sure how to apply, and 32% feel they would not be treated fairly by the government office processing their claim, on average across countries. These concerns correspond closely with barriers to take‑up identified in the extensive literature on this topic (Chapter 2).

Figure 1.5. Many find it difficult to apply for and access benefits

Share of respondents indicating the selected response to perceptions of public benefit accessibility, 2022

Note: Respondents were asked whether they strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree, or can’t choose with the following statements, bearing in mind their own experience with accessing benefits or services or their expectation if they have never accessed benefits or services: a.) “I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them.” b.) “I am confident I would quality for public benefits;” “I know how to apply for public benefits;” “I think the application process for benefits would be simple and quick;” “I feel I would be treated fairly by the government office processing my claim.”

Source: (OECD, 2023[5]), Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey, https://doi.org/10.1787/70aea928-en.

To note, the subset of respondents who feel they could not receive benefits in time of need also perceives application processes as far more difficult than other respondents. Around three-in-four of those who doubt they could easily access benefits also doubt that the application process for benefits would be quick and easy, and over half (53%) doubt that their benefit claims would be fairly processed by the government office (Annex Table 1.A.1).

1.4. The path forward: Modernising access to social protection

Significant coverage gaps persist in key social programmes in many countries. At the same time, many governments are collecting new and better data, analysing data in more sophisticated ways, linking data across different sources with unique personal identifiers, and digitalising access to social protection with the goal of improving take‑up and service and benefit delivery. The following recommendations emerge from this report.

1.4.1. Strengthen national strategies to identify people in need and integrate them into social programmes

An important foundation of any effort to improve social protection coverage and delivery is the identification of those who need – and are likely eligible for – social programmes. At least 29 OECD countries have implemented national frameworks to expand the coverage of benefits and services through better identification of potential beneficiaries (Chapter 3).

OECD governments should pursue a two‑pronged approach that enables both the identification of groups in need and facilitates the identification of those not taking up benefits for which they are likely eligible:

Linked data from different sources – e.g. on income earned and benefits received – are useful for estimating non-take‑up (Chapter 2), identifying potential beneficiaries, informing people of their entitlements, and sometimes even automatically enrolling users into programmes. Belgium, Estonia and France, among others, are making good efforts in this space (Chapters 2‑4). However, linking administrative data sources requires appropriate legal frameworks, cross-agency collaboration and data processing capabilities that not all countries possess. This is a capacity that should be strengthened.

Probabilistic estimates of need – based on survey and administrative data – therefore remain very useful for identifying vulnerable groups and regions that can be targeted by outreach campaigns. Most OECD countries, including Ireland and Spain, apply this approach (Chapter 3).

1.4.2. Explore the feasibility of automatic enrolment in social programmes

Automatic enrolment in social programmes – using personally-identified, linked administrative data – is an exceptionally promising new tool for increasing the take‑up of benefits. It relieves recipients from the burden of finding the appropriate information about benefit eligibility and applying to receive the benefit.

Automatic enrolment can also make income support benefits more responsive to evolving needs. Recent crises, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, have shown that income support needs can emerge suddenly, and overwhelm benefit infrastructures based on careful assessments of current incomes or prior contribution histories. High frequency data on income that is linked to the agencies administering benefits can also enable close‑to-real-time benefit adjustments according to claimants’ fluctuating income. This can reduce the frequency of over- and underpayments, and link income support more closely to labour supply. Low-income households are typically liquidity-constrained and may not respond to work incentives if benefit pay-outs are too far in the future, especially if taking up work/increasing working hours is associated with costs, such as transport or childcare (Hyee and Immervoll, 2022[6]).

However, to date, automatic enrollment is limited to benefits with very simple entitlement criteria, such as the birth of a child in Estonia, Norway and the Slovak Republic (Chapter 4). Social registries, too – which combine administrative data with information provided by individuals using a personal identifier (Chapter 3‑4) – have the potential to offer similar solutions, though at the moment they are mostly used for informing users about benefits for which they might be eligible, based on linked administrative data.

1.4.3. Apply lessons from behavioural research to the digital transformation

The four well-identified barriers to programme take‑up are insufficient, unclear or complex information; “hassle costs” (cumbersome application procedures); stigma; and low expected benefits. In randomised control trials (RCTs), treatment interventions of simplified information and support in programme applications usually have positive effects on applications and eventual enrolment, at least among people who are already connected to the state in some way (e.g. through tax returns) (Chapter 2).

Automatic enrolment based on linked data would resolve many of these barriers to take up, but most countries have not yet implemented these approaches. Sending prompts or clear information about likely eligibility – for example, based on linked administrative data – can also help.

To reduce “hassle” and save time for clients and civil servants, OECD countries should continue to develop websites, portals and applications to simplify programme application and renewal processes to make it easier for people to learn about, apply for and interact with government services.

At the same time, simply “going online” is not sufficient to improve social programme take‑up. Modern communication technology can present challenges even for those well-versed in it, and even higher barriers for those without regular access to (or familiarity with) mobile phones or computers, such as older people. The digital transformation of social service/benefit enrolment and delivery must be accompanied by handrails (Chapter 5).

Governments should continue to trial carefully the use of artificial intelligence (AI). At the moment AI is principally used either to provide automated support (e.g. chatbots) to answer users’ questions; to automate back-office processes (e.g. processing large amounts of data from traditional databases and unstructured text and images from scanned paper media); and occasionally, to detect fraud (Box 1.1).

1.4.4. Ensure an inclusive digital transformation of social protection

Maintaining low-barrier in-person support is particularly important for the most disadvantaged who may lack the means to access services digitally. Access to (and the use of) digital infrastructure and tools is uneven, and the digital divide is even starker when viewed from the lens of age, gender, poverty and location. Across the OECD, for example, 22% of 55‑74 year‑olds state that they do not use the internet, and in Mexico and Türkiye the rate is over 50% (Chapter 4).

It is important not to overemphasise digital interfaces at the expense of in-person presence, especially considering that people with limited digital access are also key priority groups for social protection measures. The people who are least connected to state institutions – such as people living in situations of homelessness, non-citizens, or workers who do not file income taxes – are already the least likely to take up social programmes, even when prompted about eligibility. The informational, psychological, “hassle” and other barriers are simply too high (Chapter 2).

This reinforces the continued need for targeted offers (to inform about benefits and assist the application process), as well as individualised, personal outreach, for example by community groups or social workers who can help with applications (Castell et al., 2022[7]; Finkelstein and Notowidigdo, 2019[8]).

To address this challenge, governments should include explicit provisions in their digital social protection strategies to promote digital inclusion for those more likely to miss out. Good practices include combining digital offers with call centre and in-person options (and using these measures as an opportunity to transition those who are interested to digital services), working on language and communication improvements, creating intuitive user interfaces, and providing training, intermediation and/or subsidies for devices. The digitalisation of social protection can take lessons from the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies, which offers general recommendations on the development and implementation of digital strategies that bring governments closer to all citizens.

Box 1.1. Artificial intelligence and the future of social protection

Advances in data and technology have improved the accessibility and coverage of social protection in OECD countries. In practice, the most significant advances in recent years centre around linking data across administrative sources to improve enrolment in social programmes. By linking datasets across personal identifiers – for example, by linking tax records with income benefits – governments have been able to streamline application and renewal processes, inform potential beneficiaries of their eligibility for benefits, and (in limited cases) automatically enrol users in programmes.

Data linking across government, combined with longstanding algorithms that determine statutory benefit eligibility, has the potential to transform social protection coverage. It can remove sizeable burdens of time, energy and knowledge around eligibility verification and enrolment. More OECD countries should invest in data governance that enables linked data and more efficient enrolment processes.

Social affairs ministries are using AI for chatbots, back-office processes and (rarely) fraud detection

Despite its potential as a transformative technology, artificial intelligence (AI) has – as of early 2024 – been little used by social affairs ministries. In short, governments are proceeding with caution to manage the potential risks. The most common use of AI in social protection is chatbots and virtual assistants that provide support to individuals. Countries as diverse as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Finland, Korea and Norway – among others – use AI-powered chatbots for customer support such as answering questions and providing copies of administrative documents (Chapter 4).

AI has also been used to automate back-office processes in social affairs agencies, such as through natural language processing of free‑text comments on employment records (Canada), document recognition (Finland), and voice recognition to support call centres (Austria), among others.

In some cases, such as in Korea and the United Kingdom, AI is being used for fraud detection and finding anomalies in benefit claims, which are then reviewed by a human civil servant (Chapter 4).

Looking ahead: How will AI be used in social protection?

AI has the potential to transform the identification and enrolment of social programme users, enhance user support, and improve the efficiency and timeliness of benefit and service delivery in response to changing needs (both at the macro and household level). The most likely uses – in the short run – appear to be the following:

As in the private sector, AI will likely increasingly be used to automate routine tasks, including data entry and document processing – thereby saving time for civil servants.

AI could carry out predictive analytics in big data, for example by identifying recurring risks and vulnerabilities to target social programme interventions to individuals or communities. Depending on the data available, this could usefully take a preventative approach.

AI could speed up the automation of benefit decisions based on longstanding, pre‑defined statutory eligibility rules – which should then be reviewed by human civil servants.

Social ministries are likely to continue to advance the current uses mentioned above: chatbots, automating back-office processes, and improving fraud detection.

Significant opportunities come with significant risks and challenges when deploying AI in social protection. Governments are proceeding with caution to ensure that the correct legal, regulatory and accountability frameworks are in place; that investments have been made in modern infrastructure; to involve service users in design; to develop an appropriately skilled workplace; and, importantly, mitigate the risks of further entrenching bias, discrimination and exclusion through the use of AI (Chapter 5).

1.4.5. Use personal data safely and respectfully

As countries increasingly collect, link and share data, they must take steps to mitigate the risks involved. Unintended data breaches harm not only the individual(s) involved but also damage public trust and confidence. Governments are finding themselves managing data breaches more frequently, which again can result in substantial consequences for victims as well as erode public confidence in government agencies. OECD member countries, and an estimated 71% of countries around the world, have laws in place to protect (sensitive) data and privacy (OECD, 2023[9]). Countries should continue to explore and adopt measures to both prevent and manage data breaches from occurring and design protocol for managing them when they do, including protective security frameworks, staff training, data loss prevention tools, access controls and guidance for handling personal information security breaches. These efforts should be supported by a public office, such as a privacy or information commissioner.

While critically important, complex laws, regulations, rules and conventions can cause confusion, making it challenging for agencies to act safely and effectively. A few countries have taken steps to create simple guidance to help agencies, as well as non-government service providers, navigate regulatory frameworks and other measures to ensure the safer use of people’s personal information. New Zealand, for example, has developed such guidelines (Chapter 5).

Greater use of online services, digital tools and digitalised processes in social protection creates the risk of reinforcing or creating new sources of exclusion and disadvantage. Increased digitalisation can exclude those individuals who have limited access and/or ability to engage with digital services which is a particular challenge when people with limited digital access are also key priority groups for social protection measures. This risk of exclusion extends to linked datasets that governments increasingly use to determine eligibility for services and benefits. Canada, for example, reports facing challenges regarding its ability to include indigenous populations in their linked databases that provide the foundation for benefit eligibility.

1.4.6. Accountability frameworks and procedures to avoid embedding disadvantage

Several high-profile cases have highlighted the risk of discrimination, stigmatisation and exclusion resulting from the use of predictive models and automated decision-support tools in governance. Already disadvantaged groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities, seem more likely to be impacted than others. Errors and biases in models and automated systems can be hard to detect, which is a serious issue given they can, for example, make someone appear ineligible for a benefit for which they are legally entitled.

Governments must have in place appropriate accountability frameworks and transparent procedures to prevent and address such errors and/or biases in automated systems. Without them, technology and data-driven innovations risk disempowering and disengaging people and eroding public trust and confidence in governments’ use of advanced technology and data solutions.

Governments must additionally commit to transparency, “explainability,” and meaningful human involvement, particularly when automated decisions can potentially significantly impact people’s lives. Transparency involves disclosing when automated systems are being used (e.g. to make a prediction, recommendation or decision, with disclosure being proportionate to the importance of the interaction). “Explainability” is the idea that an automated system or algorithm and its output can be explained in a way that “makes sense” to users, enabling those who have been adversely affected by an output to understand and challenge it. There should always be a degree of human involvement in automated decision-making (see for example Principle 1.2(b) of the OECD’s AI principles).

The right to review an automated decision or output is an important feature of an accountability framework. Those negatively impacted by automated decision-making (which includes a person missing out on a benefit for which they may be legally entitled to) should be able to appeal a decision and know how to do that. Some people may not be aware or have the resources to address an issue. Complaint processes should account for this with public agencies ensuring that marginalised and excluded groups are supported in making any application for a review of a decision. Staff need to be able to explain how a decision was reached and provide information about how that decision can be reviewed which requires them to be appropriately trained and for there to be adequate complaint processes in place.

References

[7] Castell, L. et al. (2022), Take-up of social benefits: Experimental evidence from France.

[4] Eurostat (2022), Inactive population not seeking employment by sex, age and main reason.

[8] Finkelstein, A. and M. Notowidigdo (2019), “Take-Up and Targeting: Experimental Evidence from SNAP”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 134/3, pp. 1505-1556, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz013.

[6] Hyee, R. and H. Immervoll (2022), The new work incentive for Spain’s national Minimum Income Benefit. Policy issues and incentives in the international comparison, https://www.oecd.org/social/benefits-and-wages/Note-on-the-new-work-incentive-Spain.pdf.

[1] OECD (2024), Poverty rate (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/0fe1315d-en.

[9] OECD (2023), “Executive summary”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/34f4cc8d-en.

[2] OECD (2023), Health at a Glance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en.

[5] OECD (2023), Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/70aea928-en.

[3] OECD (2018), OECD Employment Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2018-en.

Annex 1.A. Many individuals feel they cannot access benefits easily in times of need

Annex Table 1.A.1. People who do not think they could easily access public benefits typically also think that the application process is complex

Proportion of respondents who report perceived difficulties in accessing public benefits, among respondents who disagree or strongly disagree with the statement “I believe I could access public benefits if I needed them”, by country, 2022

|

Country |

Do not feel confident they would qualify for public benefits (%) |

Would not know how to apply for public benefits (%) |

Do not think the application process for benefits would be simple and quick (%) |

Do not feel they would be treated fairly by the government office processing my claim (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

52 |

39 |

77 |

43 |

|

Belgium |

65 |

58 |

82 |

41 |

|

Canada |

64 |

56 |

76 |

45 |

|

Chile |

69 |

44 |

80 |

66 |

|

Denmark |

48 |

55 |

82 |

51 |

|

Estonia |

49 |

48 |

69 |

44 |

|

Finland |

48 |

32 |

82 |

40 |

|

France |

74 |

38 |

77 |

54 |

|

Germany |

49 |

42 |

85 |

46 |

|

Greece |

47 |

34 |

57 |

58 |

|

Ireland |

74 |

51 |

77 |

52 |

|

Israel |

67 |

58 |

83 |

59 |

|

Italy |

67 |

59 |

77 |

54 |

|

Korea |

43 |

55 |

75 |

46 |

|

Latvia |

65 |

42 |

65 |

43 |

|

Lithuania |

37 |

42 |

78 |

51 |

|

Mexico |

41 |

60 |

83 |

72 |

|

Netherlands |

56 |

38 |

74 |

40 |

|

Norway |

46 |

52 |

82 |

57 |

|

Poland |

55 |

44 |

79 |

63 |

|

Portugal |

64 |

57 |

86 |

66 |

|

Slovenia |

52 |

49 |

68 |

57 |

|

Spain |

61 |

50 |

80 |

55 |

|

Switzerland |

53 |

50 |

83 |

44 |

|

Türkiye |

42 |

38 |

77 |

78 |

|

United Kingdom |

75 |

57 |

81 |

56 |

|

United States |

78 |

56 |

82 |

53 |

|

Average |

57 |

48 |

77 |

53 |

Note: Average refers to the unweighted average of the 27 OECD countries for which data are available. Respondents were asked: “To what degree do you agree or disagree with the following statement? If you currently are receiving services or benefits please answer these questions according to your experience. If you are not receiving them, please answer according to what you think your experience would be if you needed them: I feel I could easily receive public benefits if I needed them/I am confident I would qualify for public benefits/I know how to apply for public benefits/I think the application process for benefits would be simple and quick/I feel I would be treated fairly by the government office processing my claim”. Respondents could choose between: “Strongly disagree”; “Disagree”; “Neither agree nor disagree”; “Agree”; “Strongly agree”; “Can’t choose”. Data present the share of respondents who report “strongly disagree” or “disagree”, out of those who report that they could not easily receive public benefits if they needed them. RTM data include respondents aged 18‑64.

Source: (OECD, 2023[5]), Main Findings from the 2022 OECD Risks that Matter Survey, https://doi.org/10.1787/70aea928-en.

Note

← 1. These two groups – adults with disability and children – are aggregated within one survey response and it is not possible to disentangle results for them separately.