This chapter highlights the challenges that Chile must meet in order to improve the transparency of the information disclosed on lobbying activities. First, the chapter suggests ways to ensure that comprehensive and pertinent information on who is lobbying, on what issues and how, is disclosed. The sharing of responsibilities for transparency between lobbyists and public officials is also discussed. The chapter also discusses how to provide a convenient electronic registration and report-filing system for both public officials and lobbyists and suggests ways to improve the content and granularity of the information declared through common technical specifications, guidance and assistance provided throughout the disclosure process as well as easy-to-fill sections connected to relevant databases. Lastly, the chapter provides recommendations on centralising lobbying information to enable stakeholders to easily grasp the scope and depth of these activities.

The Regulation of Lobbying and Influence in Chile

3. Enabling effective transparency on lobbying in Chile

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

A critical element for enhancing transparency in public decision-making is to provide mechanisms through which public officials, business and civil society can obtain sufficient information regarding who has had access to public decision-making processes and on what issues. Such mechanisms should ensure that sufficient, pertinent information on key aspects of lobbying activities is disclosed in a timely manner, with the ultimate aim of enabling public scrutiny (OECD, 2010[1])

Transparency can be ensured by various means which can be complementary (Table 3.1). The transparency measures introduced by OECD countries generally assign the burden of disclosure to lobbyists through a lobbying registry. Chile has chosen an alternative approach and assigns this responsibility to public officials targeted by lobbying activities, requiring them to disclose information about their meetings with lobbyists (i.e., lobbyists and managers of private interests as defined in the Lobbying Act), through a registry, even if lobbyists are still required to register online in order to request these meetings.

Table 3.1. Tools for ensuring transparency in lobbying

|

Lobbying registers |

Voluntary or mandatory public registers in which lobbyists and/or public officials must disclose information about their interactions. The information disclosed may include the purpose of lobbying, its beneficiaries and the specific activities conducted. |

|

Public agendas |

The obligation for certain categories of public officials to publish their agenda online, including their meetings with external organisations and interest groups. |

|

Public decision-making footprint |

Documentation that details the stakeholders who sought to influence the decision or were consulted in its development, and shows what inputs into the particular public decision-making process were submitted and what steps were taken to ensure inclusiveness of stakeholders in the development of the regulation. |

Source: (OECD, 2021[2]; OECD, 2010[1])

To ensure the effectiveness of lobbying transparency frameworks, a second critical element is to facilitate the disclosure of lobbying information through convenient electronic registration and report-filing systems. This includes designing tools and mechanisms for the collection and management of information on lobbying practices, building the technical capacities underlying the registers and maximising the use of information technology to reduce the administrative burden of registration.

In Chile, the disclosure regime is specified in Title II of the Act (“On public registers”). The Lobbying Act specifies that lobbying information must be disclosed in “public agenda registers”, which are defined in Article 2 §3 as registers of a public nature, in which passive subjects must enter the information set out in in the Act:

Public registers must be created and kept by the body or service to which passive subjects in Article 3 (central state administration), Article 4 §1 (regional and communal administration), Article 4-4 (armed forces and public order and security forces) and Article 4 §7 (members of special Councils and expert panels) belong (Article 7 §1). The regulation for the publication of these registers was established by the SEGPRES (Decreto 71 – Regula el lobby y las gestiones que representen intereses particulares ante las autoridades y funcionarios de la administración del estado) (Library of the National Congress of Chile, 2014[3]). The information contained in all the registers must be published and updated, at least once a month according to the provisions specified in Article 7 of Law No. 20.285 on access to public information.

The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic, the Central Bank, the Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Commissions of the National Congress, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Administrative Corporation of the Judiciary must establish their own regulation for the publication of their public agenda register. These regulations also clarify the information that they will transmit to the Transparency Council for the establishment of a list of lobbyists and managers of private interests (Articles 9 and10). The information from these registers is published on the electronic websites established in the rules of active transparency that govern them (Article 9). In particular:

The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic keeps a public register for activities targeting the Comptroller General and Deputy Comptroller General (Article 7 §2). The regulation for this register was approved by resolution of the Comptroller General and published in the Official Gazette.

The Central Bank keeps a public register for activities targeting its President, Vice-President and Directors (Article 7 §3). The rules governing this register were established by means of a resolution of its Council, published in the Official Gazette.

Two registers, each created and kept by the respective Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Commissions, in which the information must be entered by passive subjects in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (Article 7 §4). The rules governing the registers of the National Congress were approved by the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, at the proposal of their respective Ethics and Parliamentary Transparency Commissions.

A register to be kept by the Public Prosecutor's Office for activities targeting the National Prosecutor and regional prosecutors (Article 7 §5). The regulation for this register was approved by resolution of the National Prosecutor of the Public Prosecutor's Office and published in the Official Gazette.

A register to be kept by the Administrative Corporation of the Judiciary, in which the information must be entered by its Director (Article 7 §6). The rules governing this register were adopted by the High Council of the Judiciary.

Concretely, to meet public officials, lobbyists and managers of private interests must register through the six platforms listed above, each of which has its own technical specifications. In particular, the regulation of each of these six registers specifies the information to be included in the register, the date of updating, the manner of publication, the background information required to request hearings and meetings and other aspects necessary for the operation and publication of the registers (Article 10). Decree 71, which governs the register of the central state administration, the regional and communal administration, the armed forces and public order and security forces, and members of special Councils and expert panels, indicates that passive subjects must respond within a maximum period of three business days to requests submitted by active subjects (Decree 71, Article 10). They can accept and schedule the meeting, reject their demand, or pass the request to another passive subject. Passive subjects must then disclose information on the register and update the information on the first business day of each month (Decree 71, Article 9). The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic, the Central Bank, the Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Commissions of the National Congress, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Administrative Corporation of the Judiciary have established their own rules for the publication of information in their registers.

In addition to their Public Agenda Registers, the SEGPRES, the Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic, the Central Bank, the Parliamentary Ethics and Transparency Commissions of the National Congress, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Administrative Corporation of the Judiciary must also establish their Public Register of Lobbyists and Managers of Private Interests (Article 13). The information in these registers is generated automatically from the requests filed by lobbyists and managers of private interests, and thus do not require any additional disclosures from them. The above-mentioned regulations establish the procedures, deadlines, background information and information required for entries in the public register of lobbyists and managers of private interests.

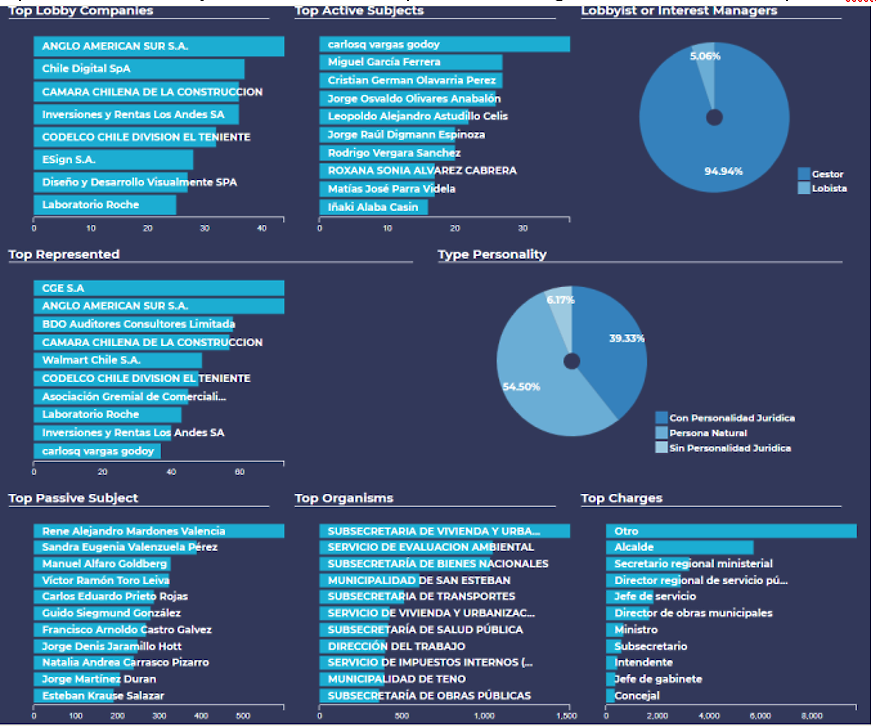

The Transparency Council then centralises the information from the public agenda registers and makes them available to the public on a single online platform www.infolobby.cl (Central Register of hearings, travels and gifts). In particular, on a quarterly basis, the Transparency Council must make available to the public a register containing a systematised list of persons, natural or legal, Chilean or foreign, who in that period have held meetings and hearings with the passive subjects listed in Article 3 (central state administration), Article 4 §1 (regional and communal administration), Article 4 §4 (Armed Forces and Public Order and Security Forces) and Article 4 §7 (Members of special Councils and expert panels), the purpose of which is lobbying or the management of private interests with respect to the decisions referred to in Article 5 (“List of Lobbyists”). This list must identify the person, organisation or entity with which the passive subject held the hearing or meeting, stating:

On behalf of whom the private interests were managed.

The individualisation of the attendees or persons present.

Whether remuneration was received for such management.

The place, date and time of each meeting or hearing held.

The specific subject matter dealt with.

The passive subjects of the regulated authorities listed in numbers §2, §3, §5, §6 and §8 of Article 4 must send to the Transparency Council the information agreed in the agreements they enter into, for the purposes of publishing it on the Central Register of hearings, travels and gifts and the List of lobbyists.

While these elements are comprehensive and provide a strong level of transparency on the official meetings held between active subjects and public officials, the disclosure regime currently only covers meetings and hearings between public officials and active subjects, leaving an important part of lobbying in the shadows. As a result, not all activities covered by the definition of “lobbying” and “management of private interests” provided in the Lobbying Act are covered by transparency requirements. In addition, while public officials have the prime responsibility to demonstrate and ensure the transparency of the decision-making process, the proposed approach in this law may result unbalanced as it lays on them all the responsibility of recording lobbying activities. Lobbyists and their clients also share an obligation to ensure that they avoid exercising illicit influence and comply with professional standards in their relations with public officials, with other lobbyists and their clients, and with the public (OECD, 2010[1]).

Lastly, the absence of a unique one-stop-shop registration and transparency platform for lobbying has emerged as one of the law's biggest challenges. For example, several private sector representatives met for the purpose of this report highlighted the absence of a single online form with harmonised registration forms for requesting hearings and meetings, which increases online procedures and thus the burden of compliance for lobbyists. In addition, information on the functioning of the law is accessible on several websites (for example, SEGPRES' www.LeyLobby.gob.cl does not cover autonomous bodies), which does not facilitate the overall understanding of the system by citizens, public officials and lobbyists.

As such, to improve transparency of lobbying activities and facilitate disclosure of lobbying information, this chapter provides recommendations on the following core themes:

Providing sufficient and pertinent information on who is lobbying, on what issues, and how.

The disclosure regime for lobbyists and public officials through convenient electronic registration and report-filing systems.

The content of disclosures and innovative tools to enhance their quality.

The transparency portal to make publicly available online, in an open data format, that is reusable for public scrutiny and allows for cross-checking with other relevant databases, information on lobbying activities disclosed in the registers.

3.2. Providing comprehensive and pertinent information on who is lobbying, on what issues and how

3.2.1. Disclosure obligations for public authorities and officials could be expanded beyond meetings that occurred to cover all meetings that were requested, so as to fully reflect the lobbying and influence taking place in practice

According to Article 8 of the Lobbying Act, the public agenda registers must include the following information:

Hearings and meetings held for the purpose of lobbying or the management for private interests in respect of the decisions referred to in Article 5. The information must indicate:

the person, organisation or entity with whom the hearing or meeting was held

on whose behalf the particular interests are pursued

the identity of the attendees or persons present at the hearing or meeting

whether any remuneration is received for such representations

the place and date of such representations

the specific subject matter discussed.

Trips made by any of the passive subjects established in the law, in the exercise of their functions. The information must indicate:

the destination of the trip

its purpose

the total cost

the legal or natural person who financed it.

Official and protocol donations, and those authorised by custom as manifestations of courtesy and good manners, received by the passive subjects established in the law, on the occasion of the exercise of their functions. The registers must identify:

the gift or donation received

the date and occasion of its receipt

the individualisation of the natural or legal person from whom it was received.

Each public institution referred to in Article 3, Article 4 §1, 4 §4 and 4 §7 with passive subjects have a dedicated lobbying institutional webpage. The technical specifications are the same for each institutional webpage as they are all hosted on the platform “Plataforma Ley del Lobby” www.leylobby.gob.cl developed by SEGPRES (Figure 3.1). In this platform, each institutional body must nominate an “institutional administrator” in charge of creating accounts for designated public officials, publishing and updating the list of the body’s designated public officials, assigning disclosure permissions, correcting and validating disclosures made by designated public officials, and co-ordinating trainings on the lobbying regulation for public officials. These public officials also have the possibility to designate “technical assistants” to respond to requests on their behalf and register information in the portal.

Figure 3.1. Standardised lobbying institutional webpages in Chile

Notes: the screen shot displays the standardised lobbying webpage and registration portals used in Chile. It includes the following sections: (i) designated public officials (“passive subjects” / “sujetos pasivos”), which links to a list of designated public officials and an online form for newly elected or nominated designated public officials to request their inclusion in the list; (ii) lobbyists (“lobbistas y gestores de intereses particulares”), which includes a form for lobbyists to register, which is a pre-requisite in order to solicit a meeting with a designated public official, and a list of lobbyists; (iii) audiences and meetings (“audiencias y reuniones”), which links to the register of audiences and meetings, and forms for lobbyists to solicit an audience/meeting; (iv) registers of travels and gifts (“viajes”, “donativos”); (v) information on the law.

Source: Lobbying institutional webpage of the Health Ministry in Chile

This two-level approach can facilitate the disclosure of meetings, as institutional bodies are better placed to manage and update their list of designated public officials, track and centralise their communications and meetings with lobbyists, and ensure that these communications are registered properly and on time. The administrator can also ensure that specific meetings or communications are not published twice in the register. For example, if a specific meeting attended by more than one passive subject is disclosed several times, the administrator can ensure that the information is centralised and published in a coherent way, avoiding duplications.

As such, the current system of publication of hearings and meetings is a good practice and should be maintained but could be generalised to all the passive subjects referred to in Article 3 and 4. Enabling such a change will require assigning responsibilities for administering the Registers to an independent body. This will be further discussed in Chapter 5.

In addition, Article 9 of the Lobbying Act could be amended so that the information disclosed is extended to unplanned communications with lobbyists, such as written communications (email exchanges, WhatsApp messages), meetings and hearings requested by lobbyists that were rejected, as well as meetings requested by passive subjects with active subjects and in which lobbying activities occurred. These additional registration requirements will enable the register to fully reflect the lobbying and influence actually taking place, as the action of requesting a meeting is in itself an act of lobbying, even if the meeting was refused or did not happen in the end. Currently, the registers only include hearings and meetings that were accepted and that occurred. In addition, this additional layer of transparency would enable greater public scrutiny on the principle of equity enshrined in Article 11 of the Lobbying Act. According to this principle, passive subjects must treat all meeting requests with equity, and cannot refuse a meeting with an interest group on a specific subject if they accepted a meeting on the same topic with another interest group. Enabling transparency on meetings that were refused will enable citizens and other interested stakeholders to make comparisons between accepted requests and rejected requests, allowing for the detection of possible violations of Article 11.

Lastly, the Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency is of the opinion that meetings between public authorities should also be published. To that end, the Commission has made proposals to establish a duty to publish meetings between high-level State authorities, such as ministers, deputies and senators, and ministers of the High Courts of Justice.

While this proposal is in line with best practices in OECD countries, however, it should be noted that meetings between public authorities do not constitute lobbying, and this should be clearly indicated and differentiated from meetings and hearings that do constitute lobbying. This aspect is further explained in the following section.

3.2.2. Information in the public agenda registers could be further clarified to clearly differentiate activities that are strictly related to lobbying and influence from other information related to passive subjects’ official agendas, travels and gifts

In transparency platforms, it is crucial to clearly differentiate activities that are related to lobbying and influence activities from other information that are not related to lobbying. For example, information disclosed regarding travels and gifts could be clarified. Indeed, the registers currently include trips made by any of the passive subjects in the exercise of their functions, as well as official and protocol donations, and those authorised by custom as manifestations of courtesy and good manners, in the exercise of their functions. While this information is useful for general transparency purposes, official travel and protocol gifts do not constitute lobbying and as such may not be as relevant to understand lobbying and influence practices taking place. Municipal representatives interviewed for this report confirmed that the register of travels and donations may contain information that is not as useful and that does not relate to any lobbying activity, such as technical trips and protocol donations.

Instead, the registers could be refocused on gifts, invitations, hospitalities and other benefits offered and paid for by active subjects, including by “professionals and researchers from non-profit associations, corporations, foundations, universities, study centres and any other similar entity” specified in Article 6 §6. These could include for example invitations to participate in a conference organised by a research centre or corporation, paid travel and other benefits provided by these entities.

Protocol gifts and trips that are carried out in the exercise of public functions could instead be registered in different platforms in the context of the broader integrity system for certain categories of public officials, and through a specific regulation, or in other sections of the registers. Such platforms could host, for example:

The public agendas of certain senior public officials covering their meetings where lobbying and influence activities are not involved. This would include, for example, meetings with other public authorities, meetings with external individuals (journalists), as well as official engagements and trips.

A register of protocol and customary gifts above a certain threshold, in line with either a gift policy enshrined in the legal framework or the specific gift policies of governments institutions.

A register of official travels, which would include official trips made by certain categories of public officials as part of their duties.

The declarations of assets and interests of certain categories of public officials, where applicable and in line with the relevant regulation.

In any case, regardless of the approach chosen, it should be clearly differentiated whether a gift comes from an active subject, or whether it is a protocol gift offered by another public authority. Similarly, the information published would make it clear whether a trip was offered and covered for by an active subject, or whether it was a travel undertaken as part of a public official’s official duties.

3.2.3. The public agenda registers could be complemented by a Register of Lobbyists where registration could be a pre-requisite to conducting lobbying activities and requesting meetings, and in which active subjects would face additional disclosure requirements

As emphasised throughout this report, the focus of the current legal framework is on the public official. This aspect is also one of the most recurrent criticisms of Law No. 20.730, as active subjects currently have limited disclosure obligations, with the exception of registering online to request hearings and meetings. Consequently, there is a lack of information about and from lobbyists beyond the information they disclose when requesting a meeting or hearing. In addition, the fact that the law only provides for the transparency of meetings and hearings means that there is a very large section of lobbying activities for which there is no information available.

As such, the current lobbying framework could also be complemented by a Register of Lobbyists, in which active subjects covered by the Law would be required to register all the activities covered by the Lobbying Act’s definition of “lobbying” and “management of private interests”. Registration could be made a pre-requisite for engaging in lobbying activities, including for requesting official hearings and meetings with passive subjects. This implies that entities and individuals wishing to engage in lobbying activities would register at the stage of intending to engage in such activities, and not after they have done so, or within a limited time frame after having conducted a lobbying activity. For example, registration could be made mandatory no later than ten days after the day on which the lobbyist begins to conduct lobbying activities. While this allows more flexibility for lobbyists, careful consideration should be given to the length of the registration deadline, to ensure it does not become an obstacle to the objective of transparency and timely access to lobbying information, or a source of confusion for some passive subjects who may wish to verify a lobbyist's registration before entering into communication with him or her.

In addition, lobbyists could be required to submit information regularly on the lobbying activities they conducted in practice. By providing an additional avenue for transparency through a separate mechanism to report all influence efforts, this register would be a complementary tool to the existing framework and also address the inherent weakness of the Act. Several OECD countries have adopted this approach with disclosure obligations for both public officials and lobbyists, including Slovenia and Lithuania (OECD, 2021[2]).

In countries that combine both approaches, cross-checking of lobbying agendas and registers provides an opportunity to cross-check information and analyse who tried to influence public officials and how. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists regularly cross-checks registered lobbyists with Ministerial open agendas (that are limited to the meetings of Ministers with external organisations), to monitor and enforce compliance with the requirements set out in the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014 (OECD, 2021[2]).

The rationale behind this additional layer of disclosures is that there are certain lobbying activities that can only be registered by the lobbyists themselves, and not public officials. Indeed, as emphasised in Section 2.2.3, a key feature of the 21st century lobbying context is that lobbyists increasingly engage in indirect forms of influence, including influence activities with clear strategies to hide the origin of the influence, in the absence of any regulatory framework to make these activities transparent. As such, only lobbyists would be able to disclose, for example, social media campaigns conducted in favour or against a specific bill being discussed in Parliament or partnering with a think tank or a research centre to produce studies and evidence supporting or opposing a specific position, as passive subjects would not be aware that such influence practices are taking place.

Good practice from other countries has found that requiring regular disclosures by lobbyists on their lobbying activities can strengthen transparency. To that end, the proposed Register of Lobbyists could require lobbyists to disclose their activities on a quarterly or semestrial basis, as in Ireland or the United States (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Frequency of lobbying disclosures by lobbyists in the United States and Ireland

|

Ireland |

United States |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Registration |

Initial registration |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Lobbyists can register after commencing lobbying, provided that they register and submit a return of lobbying activity within 21 days of the end of the first “relevant period” in which they begin lobbying (i.e., the four months ending on the last day of April, August and December each year). |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Registration is required within 45 days: (i) of the date the lobbyist is employed or retained to make a lobbying contact on behalf of a client; (ii) of the date an in-house lobbyist makes a second lobbying contact. |

|

Subsequent registration |

The 'returns' of lobbying activities are made at the end of each 'relevant period', every four months. They are published as soon as they are submitted. |

Lobbyists must file quarterly reports on lobbying activities and semi-annual reports on political contributions. |

|

|

Content of disclosures |

Initial registration |

“Applications”: 1. The person’s name. 2. The address at which the person carries on business. 3. The person’s business or main activities. 4. Any e-mail address, telephone number or website address relating to the person’s business or main activities. 5. Any registration number issued by the Companies Registration Office. 6. (if a company) the person’s registered office. The application shall contain a statement by the person by whom it is made that the information contained in it is correct. |

1. Contact details, information on clients (one registration per client) and/or the employer. 2. Information on the intended subjects of their lobbying activities. 3. Estimation of payment received or expenditures incurred for lobbying activities. |

|

Subsequent registration |

“Returns” made at the end of each relevant period (3 months), covering activities made during the relevant period: 1. Information relating to the client (name, address, main activities, contact details, registration number). 2. The designated public officials (DPO) to whom the communications were made and the body to which they employed. 3. The relevant matter of those communications and the results they were intended to secure. 4. The type and extent of the lobbying activities, including any “grassroots communications”, where an organisation instructs its members or supporters to contact DPOs on a particular matter. 5. The name of the individual who had primary responsibility for carrying on the lobbying activities. 6. The name of each person who is or has been a designated public official employed by, or providing services to, the registered person and who was engaged in carrying on lobbying activities. |

Quarterly reports on lobbying activities (LD-2), including: 1. General lobbying issue area code(s). 2. Specific issues on which the lobbyist(s) engaged in lobbying activities. 3. Houses of Congress and specific Federal Agencies contacted. 4. Disclosing the lobbyists who had any activity in the general issue area. Semi-annual reports on certain contributions detailing political contributions and attesting to their compliance with Congress’ Code of Conduct as regards to gifts. |

|

Source: (OECD, 2021[2])

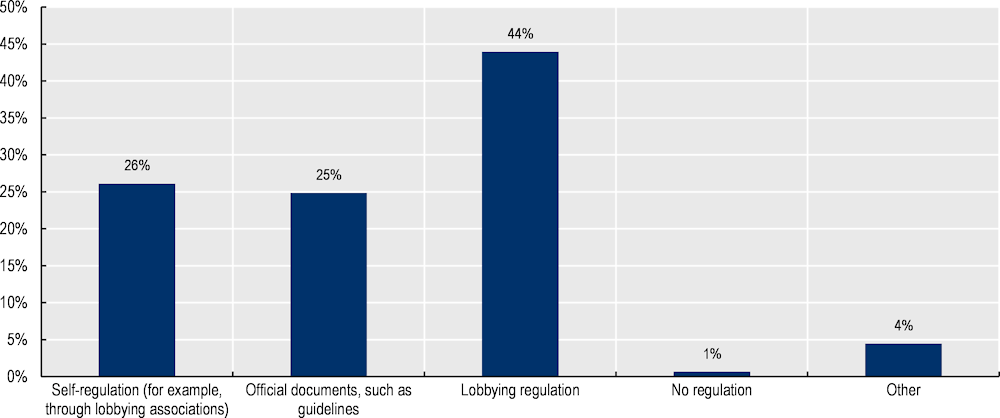

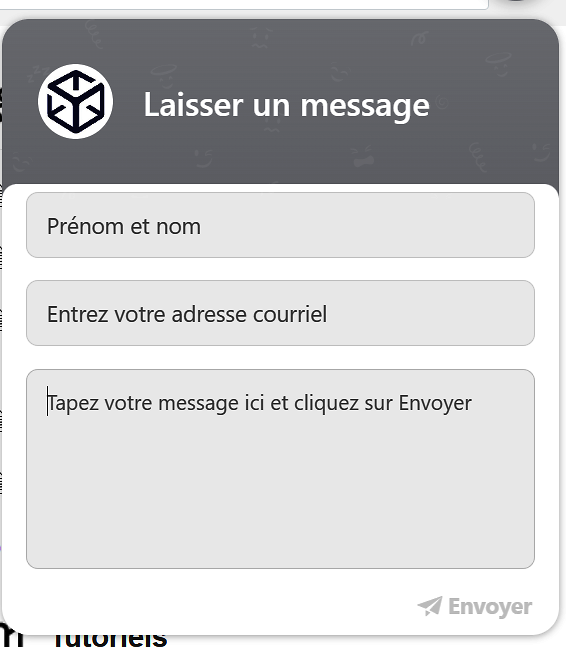

While it is generally assumed that professional lobbyists oppose the creation of lobbying registers and the public disclosure of their lobbying activities, none of the private sector representatives interviewed in Chile for this report opposed the proposal to create a complementary “Register of Lobbyists”. Some even expressed strong support for this proposal. In general, the OECD's interviews with various stakeholders revealed a consensus on the need to supplement the information currently reported in the registry, particularly on the targets of lobbying and their objective. This is line with OECD findings from a survey conducted in 2020, in which lobbyists expressed a willingness to participate in a mandatory lobbying registry, and many felt that this was necessary to protect the integrity of the profession (Figure 3.2). The same lobbyists surveyed by the OECD in 2020 were 57% of the opinion that the policy, piece of legislation targeted by the lobbying action should be made transparent by lobbyists. These attitudes reflect a commitment to integrity in public decision making and the importance of maintaining public trust.

Figure 3.2. Best means for regulating lobbying, according to lobbyists

Respondents were asked the following question: “In your opinion, which is the best means for regulating lobbying activities?”

3.2.4. The Lobbying Act could include clear criteria for withholding the disclosure of information related to national security or protected commercial information

In Chile, exceptions to transparency obligations including meetings, hearings and trips are included in the Lobbying Act when their publicity would compromise the general interest of the Nation or national security (Article 8). To that end, an annual account of these must be submitted, in a confidential manner, to the Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic, for passive subjects referred to in Article 3 and in Article 4 §1, §2, §4 and §7. For other passive subjects, the report must be submitted to the person with the power to impose penalties, in accordance with the rules of Title III, discussed in Chapter 5.

While the reasoning behind exempting this type of information is sound, and a similar provision can be found in many lobbying regulations, the Lobbying Act or its related regulations could provide clearer criteria to guide the Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic’s determination for when to withhold certain information and on what grounds.

In addition, the provision could be strengthened to add the possibility for lobbyists to request the withholding of the disclosure of certain information related to sensitive commercial information. Such requests could be made to an independent oversight entity, with clear criteria to guide determination.

3.3. Providing a convenient electronic registration and report-filing system for both public officials and lobbyists

3.3.1. While remaining separate, the two proposed registers – for lobbyists and for public officials – could be hosted on a single central registration and disclosure portal so as to facilitate registration and enable greater public scrutiny through cross-checking of information

To facilitate disclosures, the OECD recommends avoiding a “distributed” form of lobbying registers – e.g., every institution having its own register hosted on different platforms with different technical specifications – which can undermine interoperability and reliability.

To that end, the registration and disclosure platform of all registers – for public officials and active subjects – could be hosted on the same platform. This will enable greater interoperability between both registers. For example, lobbyists and managers of private interests disclosing information would be able to select passive subjects from a list based on the list of passive subjects kept up to date in the current public agenda registers by public authorities. Similarly, public officials disclosing their relevant communications in the public agenda registers could be able to select the names of active subjects from a search bar connected to the list of lobbyists and managers of private interests registered in the Register of Lobbyists.

3.3.2. The technical specifications of the registration system developed by SEGPRES for the public agenda registers could be used and generalised to all government entities

Given that most of the passive subjects defined in the Law belong to the central state administration and the regional and communal administration, the majority of the lobbying registrations published by the Transparency Council on the centralised transparency platform “InfoLobby” www.infolobby.cl come from the lobbying registration platform designed and managed by SEPGRES. As described in Section 3.2.1, this system of a unique lobbying registration portal – “Plataforma Ley del Lobby” www.leylobby.gob.cl – leading the user to different institutional webpages with the same technical specifications is a good practice that could be maintained. Over 700 government organisations – including ministries, undersecretaries, public services, regional governments, presidential delegations, municipalities, municipal corporations, among others – currently use the system to manage and consolidate the lobbying information that is then transferred to InfoLobby for publication and visualisation.

Thus, the registration system currently developed by SEGPRES could in the future be used to build a unique registration platform that would be used by all passive subjects referred to in Articles 3 and 4 of the Lobbying Act.

3.3.3. The Register of Lobbyists could place the obligation to register on entities through a unique identifier and a collaborative space per organisation, while clarifying the responsibilities of designated individuals in the registration of information

To facilitate disclosures, and later to make it easier to find accurate information about entities in the Register of Lobbyists, the Lobbying Act could focus the framework on corporate and institutional accountability, and place the registration requirement on entities rather than on individuals, as entities are the ultimate beneficiaries of lobbying activities. Currently, when searching the list of registered lobbyists generated automatically, the pieces of information that appear most clearly are natural persons conducting lobbying, even though these natural persons are usually employed by the entity which they represent, or work within a professional lobbying firm. Very few entities appear in the list of active subjects. In addition, no further information other than the name of the person or entity, whether they are lobbyists or managers of interest, a natural and legal person, appear in the list of lobbyists (for legal persons, the national identifier of the legal entity is also visible). This makes it difficult to understand which interests are the ones being represented.

It is therefore recommended that the proposed Register of Lobbyists places the obligation to register on entities – through a unique identifier – instead of individuals. Concretely, the Register of Lobbyists would display clearly:

The name of the legal entities who conduct lobbying on their own behalf (i.e., companies, civil society organisations, etc. with in-house lobbyists).

The name of the legal entities who conduct lobbying on behalf of clients (i.e., lobbying firms, law firms), and the list of their clients.

The name of self-employed lobbyists (natural persons) who conduct lobbying on behalf of clients, and the list of their clients.

To register, entities that are lobbying would be able to designate one or more registrars to register the entity, as well as to consolidate, harmonise and report on the lobbying activities of the entity. When requesting meetings with passive subjects, the entity would still be required to disclose the names of the individual lobbyists who would attend the meeting. Similarly, when disclosing lobbying activities, entities would be required to disclose the names of all individuals employed in the entity who have engaged in lobbying activities.

In Quebec for example, each entity has its own “Collective space”, which contains all the lobbying activities conducted by the entity by one or several lobbyists. Lobbyists who have been tasked by the entity to register information in that “Collective Space” can create their own individual professional account and connect this account to the Collective space of the entity. Similarly, in France, the online registration portal is designed as a workspace for legal entities, each of which has a “collaborative space”, which enables them to communicate lobbying information to the High Authority for transparency in public life (HATVP) in the best possible conditions. Individual lobbyists lobbying on behalf of a legal entity can create their own individual accounts and ask to join the collaborative space of that entity. The collaborative space is managed by an “operational contact” designated by the entity; he or she manages the rights of every individual registered in the collaborative space (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3. Responsibilities to register lobbying information in Ireland, France and Quebec (Canada)

|

Disclosure responsibilities |

|

|---|---|

|

France |

It is up to the legal representative of the organisation to create and manage the organisation's collective space on the registration portal or to designate a person, internal or external to the organisation, as the “operational contact” to carry out these procedures. |

|

Ireland |

Legal entities designate “administrators” with responsibilities to register and publish lobbying information. |

|

Quebec, Canada |

The most senior executive of an entity and the “Administrator” designated by the entity have the responsibility to manage the members of their Collective Space and their roles, as well as the information relating to the entity registered in the Collective Space. Lobbyists who conduct lobbying activities on behalf of the entity must be registered and members of the Collective Space. All members of a Collective space hold the de facto role of “Editor-Reader” (ER). This allows them to contribute to the drafting of lobbying returns. However, only the most senior executive of the entity – or a designated representative – has the responsibility of validating the disclosure or modification of lobbying returns. |

Source: www.lobbying.ie (Ireland); Registering in Carrefour Lobby Québec, https://lobbyisme.quebec/en/lobbyists-registry/registering-in-the-registry/ (Quebec, Canada); HATVP (2023) Répertoire des représentants d’intérêts, Bilan des déclarations d’activités 2022, https://www.hatvp.fr/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/HATVP_BILAN_RRI-2022_VF.pdf (France)

A similar system could be implemented in Chile, in which every entity – whether lobbying on its own behalf or on behalf of clients – would be required to register as an entity with a “collaborative space” in the registration portal. One or several representatives of this entity would be designated as the registrar(s) and manager(s) of this collaborative space and assign responsibilities to individuals for the registration of lobbying activities. The registrar and any person designated by the registrar to register information would have their own individual accounts and contribute to the collaborative space.

Such a system has several advantages. First, assigning clear disclosure responsibilities to certain individuals can help these entities to track and centralise internally their lobbying activities. Second, it also ensures that the lobbying information is published in a harmonised and therefore more coherent and intelligible way, as designated individuals are already trained to use the disclosure platform. Lastly, placing the responsibility for registration on entities and not individuals can help avoid the stigmatisation of individual lobbyists while also allow an entity to be held accountable for potential breaches of the Lobbying Act.

3.4. Enhancing the quality of the information disclosed by active and passive subjects

3.4.1. The centralised lobbying registration and disclosure portal could serve as a one-stop-shop for lobbyists and public officials on how to register and disclose information

To ensure compliance with registration requirements, and to deter and detect breaches, the lobbying oversight function should raise awareness of expected rules and standards and enhance skills and understanding of how to apply them (OECD, 2010[1]).

The Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency has made available on the portal www.leylobby.gob.cl information and guidance documents, but the latter are limited to a citizen handbook and a legal handbook on the Lobbying Act. In addition, the Commission provides technical assistance and trainings to passive subjects referred to in Article 3, Article 4 §1, 4 §4 and 4 §7. It relies on an internal “Register of technical assistance” in order to monitor needs of technical assistance by public officials. Information is then published in a report on “Monitoring, reporting and support reports”, made available online.

In the future, in the event that broader disclosure obligations for both public officials and active subjects are put in place, the guidance and assistance provided to lobbyists / managers of private interests and public officials could be strengthened. Local elected representatives interviewed for this report particularly insisted on the need for more guidance, guidelines and manuals on the Lobbying Act due to a lack of knowledge and awareness of the law at the local level. This aspect was further confirmed by the Transparency Council, which pointed that some mayors believed that every hearing and meeting with an external actor constituted lobbying, and therefore tended to register meetings that did not constitute lobbying. Based on international best practices, guidance and assistance may include, among others:

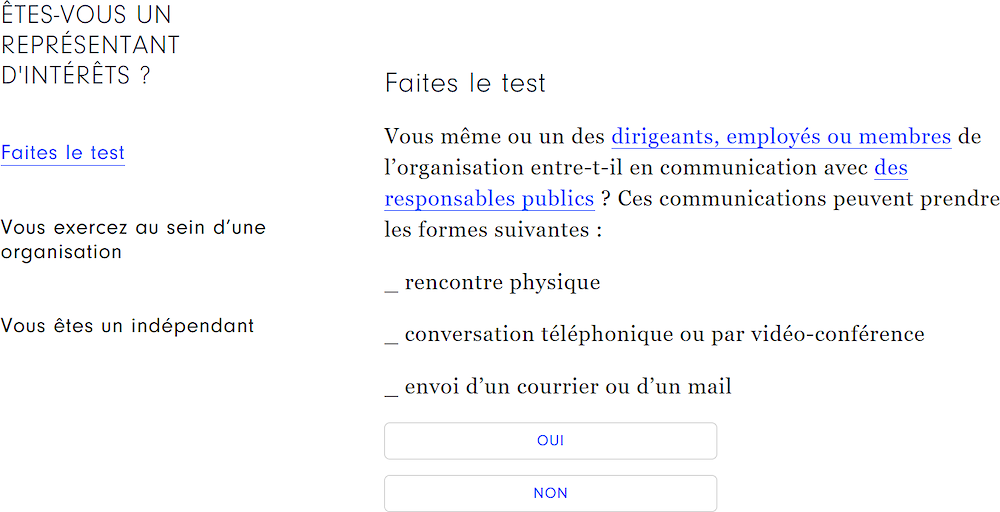

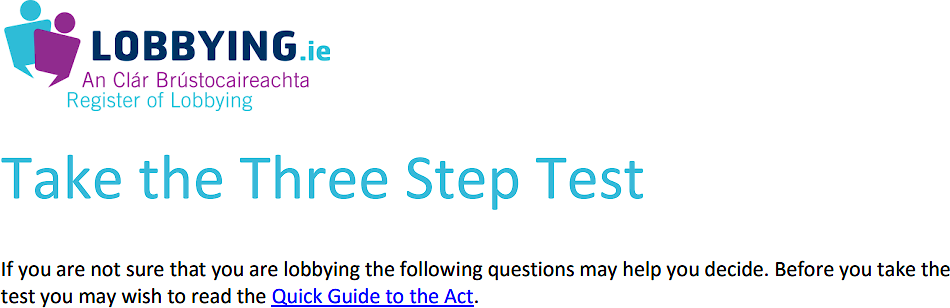

A step-by-step questionnaire on whether to register as a lobbyist or whether a request for a meeting constitutes lobbying. While definitions in the Lobbying Act should be robust, comprehensive and sufficiently explicit to avoid misinterpretation and to prevent loopholes (OECD, 2010[1]), some individuals or interest groups may have doubts on whether their activities qualify as lobbying under the Act. A short online questionnaire can help remove any doubt. For example, the Irish lobbying portal www.lobbying.ie includes a simple Three-Step Test – “Are you one of the following?”, “Are you communicating about a relevant matter?”, “Are you communicating either directly or indirectly with a Designated Public Official?” – to allow potential registrants to determine whether they are or will be carrying out lobbying activities and are required to register. Once they decide to register, all new registrations are reviewed by the Commission for Standards in Public Life to ensure that the person is indeed required to register and that they have done so correctly (Irish Standards in Public Office Commission, 2016[4]). The French portal also includes a similar online test (HATVP, n.d.[5]), with questions also available in English (HATVP, n.d.[6]) (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Step-by-step questionnaire on whether to register as a lobbyist in Ireland (top) and France (bottom)

Technical guidelines on managing accounts. When registering, it is possible that lobbyists and public officials may at first struggle on how to set up an account, how to authenticate themselves and manage their passwords. It may therefore be useful to provide technical guidelines to support them in the first steps of their registration. For example, the Irish lobbying portal provides guidelines on “How to Manage your Account” (https://www.lobbying.ie/help-resources/information-for-lobbyists/new-user-how-to-section/how-to-manage-your-account/), which is part of a “New User - How to section”.

Regular email correspondence and automatic reminders sent to lobbyists and public officials to improve compliance with reporting requirements. Sending reminders to lobbyists and public officials about mandatory reporting obligations can help mitigate the risk of non-compliance (Box 3.1). Newly registered lobbyists and public officials can also be sent a letter or email highlighting their reporting obligations and deadlines, as well as best practices for account administration and details of enforcement provisions in the event of non-compliance, as is the case currently in Ireland (Irish Standards in Public Office Commission, 2022[7]).

Box 3.1. Automatic alerts to raise awareness of disclosure deadlines

Australia

Registered organisations and lobbyists receive reminders about mandatory reporting obligations in biannual e-mails. Registered lobbyists are reminded that they must advise of any changes to their registration details within 10 business days of the change, and confirm their details within 10 business days beginning 1 February and 1 July each year.

France

Lobbyists receive an e-mail 15 days before the deadline for submitting annual activity reports.

Germany

If no updates are received for more than a year, lobbyists receive an electronic notification requesting them to update the entry. If the information is not updated in three weeks, their file is marked “not updated”.

Ireland

Registered lobbyists receive automatic alerts at the end of each of the three relevant periods, as well as deadline reminder e-mails. Return deadlines are also displayed on the main webpage of the Register of Lobbying.

United States

The Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives provides an electronic notification service for all registered lobbyists. The service gives e-mail notice of future filing deadlines or relevant information on disclosure filing procedures. Reminders on filing deadlines are also displayed on the Lobbying Disclosure website of the House of Representatives.

Source: (OECD, 2021[2])

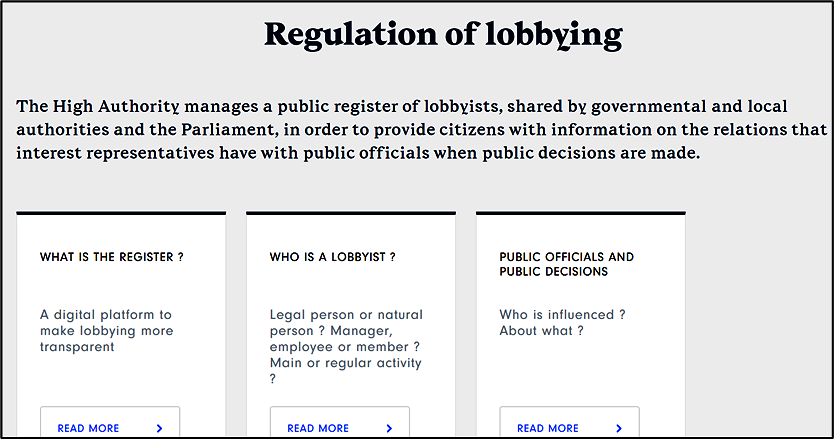

Online guidelines, videos and handbooks clarifying certain aspects of the law, including definitions and what to register. For example, the HATVP published a detailed handbook entitled “Register of interest representatives: Guidelines”, which clarifies the provisions of the law, available both in English and in French (HATVP, 2019[8]). The guidelines are updated on a regular basis. The HATVP lobbying web portal also includes a downloadable “Presentation kit”, which includes explanatory videos, an awareness-raising brochure and posters, as well as the guidelines, practical sheets and a video tutorial on the use of the registration portal. All guidance is available on a one-stop-shop dashboard (https://www.hatvp.fr/espacedeclarant/representation-dinterets/) (Figure 3.4). Similarly, the Irish lobbying portal www.lobbying.ie includes a series of webpages with guidelines for lobbyists, including targeted guidelines for specific interest groups (e.g., “Top ten things Charities need to know about Lobbying”), as well as a document “Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015: Guidance for people carrying on lobbying activities”, updated on a regular basis (Irish Standards in Public Office Commission, 2019[9]).

Figure 3.4. One-stop-shop Lobbying dashboard with online guidelines in France

Guidelines for lobbyists on how to track and monitor internally their lobbying activities. Such guidelines, in the form of monitoring guidance, can help promote compliance and registration. The example of France is provided in (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. “How to track your lobbying activities” tool developed by the HATVP in France

In France, lobbyists are required to disclose to the HATVP details of the activities carried out over the year within three months of the close of their accounting period. This annual declaration takes the form of a consolidated report by subject and declared in the form of returns on the disclosure platform.

1. Designate a “referent” / “administrator” responsible for consolidating, harmonising and declaring the lobbying activity returns in the portal.

2. Identify all persons likely to be qualified as “persons responsible for interest representation activities” (i.e., lobbying).

Identify a priori the persons likely to fall within the scope, on the basis of job titles and the tasks generally carried out, ask all identified persons to trace their communications with public officials and register them in the registration portal.

3. Implement an internal reporting tool to consolidate all the information that should be included in the annual disclosure of lobbying activities, in particular:

|

Date |

Indicate the date or period in which the interest representation activity was carried out |

|

Action carried out by |

Indicate the name of the person in charge of interest representation activities who initiated the action |

|

Object |

Indicate the objective of the interest representation activity, preferably by indicating the title of the public decision concerned and using a verb (e.g., “PACTE law: increase the tax on ...”) |

|

Area(s) of intervention |

Choose one or more areas of intervention from the 117 proposals (several choices possible, up to a maximum of 5 choices) |

|

Name of public official(s) targeted |

Indicate the name of the public official(s) targeted |

|

Category of public official(s) targeted |

Choose the type of public official(s) you want from the list (several choices possible) |

|

Category of public official(s) targeted: Member of the Government or ministerial cabinet |

If you have selected “A member of the Government or Cabinet”, choose the relevant ministry from the list |

|

Category of public official(s) applied for: Head of independent administrative authority or independent administrative authority |

If you have selected “A head of an independent administrative authority or an independent administrative authority (director or secretary general, or their deputy, or member of the college or of a sanctions committee)”, choose the authority concerned from the list |

|

Type of interest representation actions |

Choose the type of interest representation activity carried out from the list (several choices possible) |

|

Time spent |

Indicate the time spent in increments of 0.25 of a day worked; 0.5 corresponding to a half day and 1 corresponding to a full day |

|

Costs incurred |

Indicate all costs related to the representation work (commissioning a study, invitation to lunch, etc.). |

|

Annexes |

Attach all necessary supporting documents: cross-reference to diary, working documents, email, expense report, etc. |

|

Comments (optional) |

Observations |

Guidelines on how to register initial information and submit regular returns / activity reports. In addition to guidelines on clarifying definitions and creating accounts, lobbyists and public officials also need detailed guidelines on how to register in the portal and submit the information requested. For example, the Irish lobbying portal includes a “New User – How to section” with step-by-step guidance on “How to register as a lobbyist” and “How to submit a return”, including a “Sample Return Form”.

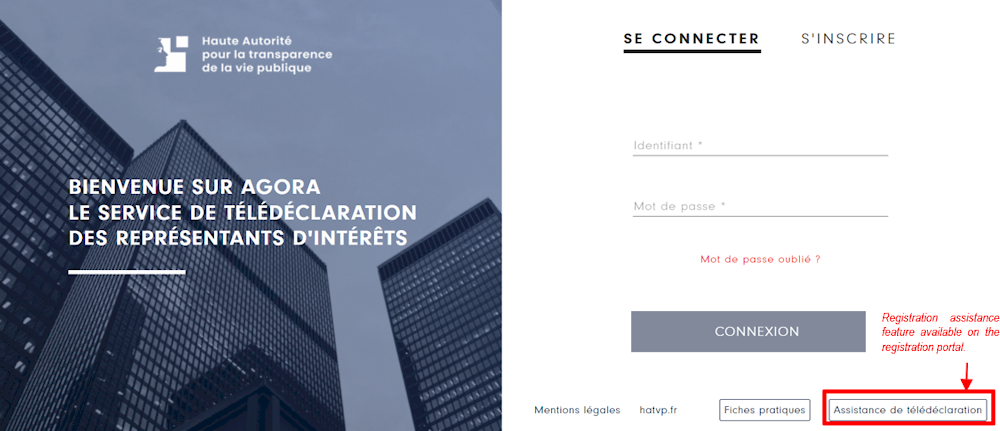

Live help tools such as pop-ups, instructions on how to fill a section, calling a specific hotline or calling / e-mailing a dedicated contact. For example, the HATVP has a dedicated hotline that lobbyists and public officials can reach when registering information, available Monday to Friday from 9:00 to 12:30 and from 14:00 to 17:00. A dedicated help function called “Registration assistance” is available directly on the registration portal (Figure 3.5). Similarly, the Quebec platform includes an “intelligent” chatbot where citizens and lobbyists can ask questions or raise doubts (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.5. Dedicated lobbying hotline to assist lobbying registration in France

Figure 3.6. Lobbying chatbot available on Quebec’s “Carrefour Lobby Quebec” platform

Mandatory induction trainings on the Lobbying Act and the registration process. For example, the New York State Lobbying Act provides for a continuing education regime for all registered lobbyists (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Trainings for lobbyists in the State of New York

The New York State Commission on Ethics and Lobbying in Government (COELIG), which administers the Lobbying Act, provides a mandatory online training course for individuals registered as lobbyists. Subject matters include information provided in the Lobbying Act, relevant regulations and advisory opinions, as well as reporting obligations and ethical standards. The training also includes best practices for meeting the various statutory requirements.

Each person registered as a lobbyist must complete this training course within 60 days of initial registration and at least once in any three-year period during which they are registered as a lobbyist.

Source: New York State Commission on Ethics and Lobbying in Government, “Information on the Mandated Ethics Training Requirement for Lobbyists and Clients”, https://ethics.ny.gov/information-mandated-ethics-training-requirement-lobbyists-and-clients

3.4.2. The registration portals could include clear and easy-to-fill sections, connected to relevant databases so as to facilitate registration and ease the burden of compliance for lobbyists and public officials

When designing registration portals, particular attention should be given to innovative solutions that could help ease the burden of compliance, for example connecting certain sections to relevant databases and enabling lobbyists and public officials to choose from a drop-down menu. For example, if a lobbyist intends to lobby on a specific bill, he or she would be able to choose the name of the specific bill from a drop-down menu connected to the database of legislative bills of the Parliament. This system is for example in place in Quebec (Canada), and also avoids the caveat of having a same bill being referenced or formulated in different ways by lobbyists.

The following two tables contain examples of the specific sections that could be included in the initial registration form for lobbyists and managers of private interests (Table 3.4) and the form to request a meeting/hearing (Table 3.5), including the type of disclosures and interoperability with relevant databases. The proposals are based on SEGPRES’s existing form to request an audience (Formulario Solicitud Audiencia Ley No. 20.730), as well as international best practices from Canada, Ireland and France. In particular, the registration forms for lobbyists could require lobbyists to state any type of existing or past relationship with decision makers or their advisors, so as to clarify any potential conflict of interest.

Table 3.4. Proposals for sections to be included in the initial registration for active subjects (pre-requisite to conduct lobbying activities and request meetings with public officials)

|

Section |

Type of disclosure |

Interoperability with relevant databases |

|---|---|---|

|

Type of entity |

Drop-down menu (e.g., “law firm”, “self-employed lobbyist”, “company”, “trade and business association”, “non-governmental organisation”, “think tank or research institution”, “organisation representing churches and communities”, “other”) |

/ |

|

Name of the legal entity or name of the self-employed lobbyist |

Search bar based on company register or other directories of legal entities |

|

|

Parent or subsidiary company benefiting from the lobbying activities |

Search bar based on company register or other directories of legal entities |

|

|

Top executives and board members |

Name and Title |

/ |

|

Administrator(s) / operational contact(s) (designated to administer the collective space of the company/organisation) |

Name and title |

/ |

|

Editors (with authorisations and responsibilities to draft lobbying disclosures) |

Name and title |

/ |

|

Whether the individuals listed above were former passive subjects |

Yes / No (if yes, name of the institutional body and period of service) |

|

|

Clients, if applicable |

Search bar based on company register or other directories of legal entities |

|

|

Sector of activity |

List of sectors in drop down menu (with the possibility to select “other” and specify details) |

/ |

|

Membership and/or contributions to professional organisations, lobbying associations, coalitions, chambers of commerce, etc. |

Search bar based on company register or other directories of legal entities |

|

|

Financial contributions to other interest groups |

Search bar based on company register or other directories of legal entities Amount of the financial contributions |

|

|

Public and private funding received, if any |

Search bar based on public authorities covered by the Act Amount of the contributions received |

|

Source: author’s contribution, based on (OECD, 2021[2]) and (OECD, 2023[10])

Table 3.5. Proposals to strengthen SEPGRES’s existing form to request meetings and hearings with passive subjects for lobbyists / managers of private interests

|

Section to be filled |

Type of disclosure |

Interoperability with relevant databases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

WHO carries out the lobbying and ON BEHALF of WHOM? |

Information on the entity |

Pre-filled, based on information provided in the initial registration |

Information from initial registration |

|

Name of the lobbyists who will attend the meeting |

Select from list of pre-registered individuals or add names of lobbyists (i.e., those not registered in the initial registration) |

Information from initial registration |

|

|

Whether these lobbyists were previously designated public officials |

Yes/No (pre-filled for those registered in the initial registration or to fill for new lobbyists) |

Information from initial registration |

|

|

Name of client on behalf of whom the activities are conducted (if applicable) |

Select from disclosed clients in initial registration |

Information from initial registration |

|

|

WHO are the passive subjects you want to meet for lobbying purposes? |

Institutions targeted |

Search bar and drop-down menu |

List of public institutions covered by the Act |

|

Type of public official targeted (general nature of duties) |

Search bar and drop-down menu (based on previous choice) |

/ |

|

|

Name of public official targeted |

Search bar and drop-down menu (based on previous choice) |

Lists of passive subjects |

|

|

WHAT matter(s) do you want to lobby about during the meeting? |

Select the relevant public policy area |

Search bar or “other” |

/ |

|

Category of public decision(s) targeted (relevant matter) |

Drop-down menu (e.g., “public policy, action or programme”, “law or other instrument having the force of law”, “grant, loan or other forms of financial support, contract or other agreement involving public funds, land or other resources”, “permits and the zoning of land”, “appointments of key government positions”, “other policy or orientation”) |

/ |

|

|

Name or description of the decision(s) targeted |

Search bar or “Other” (with open box) |

Databases of laws, draft bills, regulations |

|

|

Objective pursued / intended results, including what specific issue/legislation/programme was it about and in what direction (e.g., adoption, modification, removal)? |

Open box (500 characters) |

/ |

|

|

Documents submitted to public officials with the request (if any), e.g., commissioned research or policy briefs |

Attachments |

/ |

Source: author’s contribution, based on SEGPRES’s existing registration form (Formulario Solicitud Audiencia Ley No. 20.730), (OECD, 2021[2]) and (OECD, 2023[10])

The sections in the form to disclose subsequent information on lobbying activities – on a quarterly or semestral basis – would be similar to the ones specified in Table 3.5 on who lobbied, who was the target, and what matters were lobbied about. These disclosures could take the form of “activity reports” filed for each objective pursued, and would specify all lobbying activities undertaken (for example all activities undertaken to “modify article X of Bill Y in direction Z”) and the type of lobbying activities undertaken (e.g., written communications, commissioning of research, meetings with public officials, social media campaigns, etc.) for that specific objective. To that end, an additional section on “HOW was the lobbying carried out?” would include a drop-down menu with the type of communication tool used (including for example written communication, telephone, meeting, grassroots lobbying / mass communications, other) and an open box to describe the communications used (e.g., “5 written communications by email with Parliamentary X”, “social media campaign advocating for a change in law Y”). For example, where social media is chosen as the activity type, lobbyists could indicate if it was via twitter/Facebook/etc. as well as an estimate of the volume of posts. Lobbyists would also specify policy and position papers, amendments, opinion polls and surveys, open letters and other communication or information material that were sent to passive subjects in writing, or presented to them during a meeting.

Similar sections could be proposed for public officials when disclosing their lobbying meetings and communications with lobbyists, as indicated in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6. Proposals for sections to be included in the registration portal for public officials

|

Category |

Section |

Type of disclosure |

Interoperability with relevant databases |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WHO is disclosing |

Name of the passive subject |

Pre-filled based on personal account |

/ |

|

Institutional body |

Pre-filled based on personal account |

/ |

|

|

WHO carried out the lobbying activity and ON BEHALF of WHOM? |

Name of the business / organisation conducting lobbying activities |

Search bar based on the Register of Lobbyists If the search does not yield any results, the name can be registered manually |

Register of Lobbyists |

|

Name of natural person lobbying |

Search bar based on Register of Lobbyists If the search does not yield any results, the name can be registered manually |

Register of Lobbyists |

|

|

Clients, if applicable |

Search bar based on Register of Lobbyists If the search does not yield any results, the name can be registered manually |

Register of Lobbyists |

|

|

Other passive subjects present in the meeting, if applicable |

Search bar based on list of passive subjects |

List of passive subjects |

|

|

WHAT matter(s) were you lobbied about? |

Relevant public policy area |

Pre-filled based on institutional webpage |

/ |

|

Category of public decision(s) targeted (relevant matter) |

Drop-down menu (e.g., “public policy, action or programme”, “law or other instrument having the force of law”, “grant, loan or other forms of financial support, contract or other agreement involving public funds, land or other resources”, “permits and the zoning of land”, “appointments of key government positions”, “other policy or orientation”) |

/ |

|

|

Name or description of the decision(s) targeted |

Drop down menu or “Other” (with open box) |

Databases of laws, draft bills, regulations |

|

|

Subject matter (brief summary of topics discussed and the objective pursued) |

Open box (500 characters) |

/ |

|

|

Any decisions taken or commitments made |

Open box (500 characters) |

/ |

|

|

HOW was the lobbying carried out? |

Type of communication |

Drop down menu (e.g., meeting, email correspondence) |

/ |

|

Date |

Date picker (a date range could be selected if for example the communication is an email correspondence spanning over several days) |

/ |

|

|

Location (for meetings) |

Open box |

/ |

Source: author’s contribution, based on (OECD, 2021[2]), (OECD, 2023[10]) and the Lobbying Act

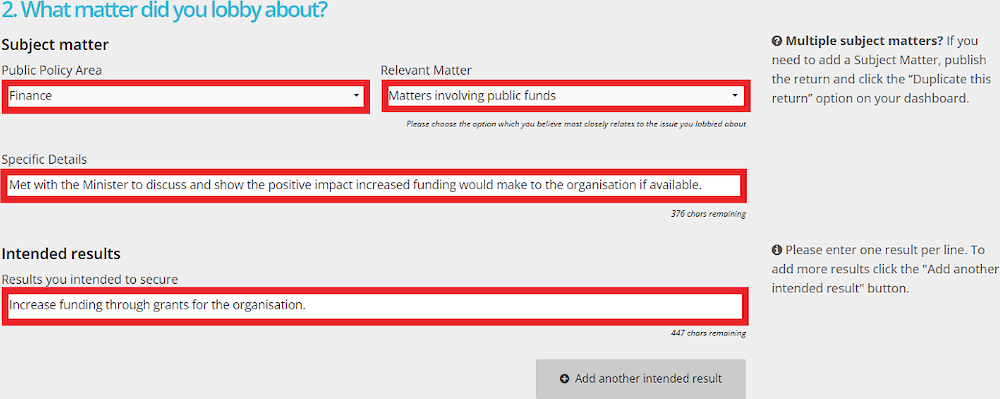

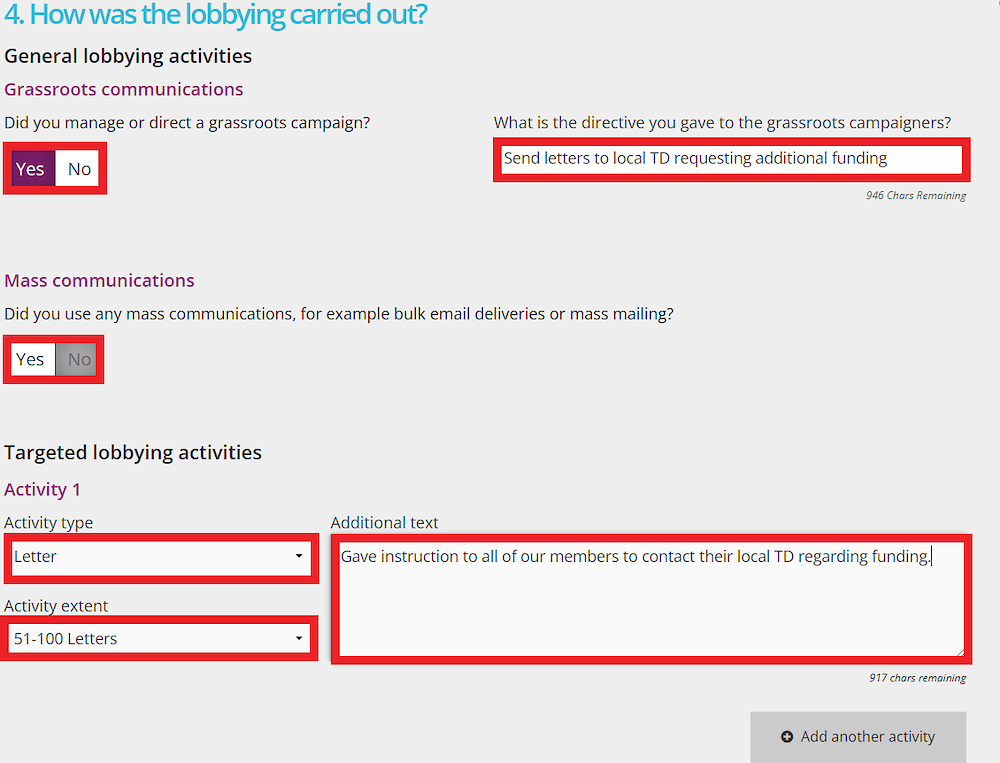

As illustrated in the tables above, the sections should be clear and enable lobbyists to file information on the specific purpose of lobbying activities (“WHAT”), how lobbying activities were carried (“HOW”), who carried the lobbying activities and who were the targets of the lobbying activities (“WHO”). The Registration portals should also include a possibility to save a draft and return later. Good practice examples of clear categorisation and visual identity in Ireland are provided in Figure 3.7.

Figure 3.7. Selected sections to be filled by lobbyists in the Irish registration portal

Source: Standards in Public Office Commission, Guidance on how to submit a return, https://www.lobbying.ie/help-resources/information-for-lobbyists/new-user-how-to-section/how-to-submit-a-return#:~:text=Submitting%20a%20Return,return%20of%20lobbying%20activities%E2%80%9D%20screen.

3.4.3. The registration portals could provide guidance on filling sections with open text and use data analytics tools to enhance the quality of information disclosed in these fields

The quality of information disclosed in boxes with open text may vary and lobbyists may not always understand what is expected of them when disclosing information in these fields. For example, open boxes where lobbyists must explain the objective pursued and the intended results should in theory include words such as “modify”, “propose” “prevent the adoption of”, “influence the preparation of”, “push for the enactment of”, “obtain the grant of” / “obtain financial aid”, “prohibit the practice of”, “promote the use of”, but this might not always be the case in practice. Experience from other countries has found that the section describing the objective pursued by lobbying activities was often used to report on general events, activities or dates of specific meetings (e.g., “meeting with a senator to discuss 5G technology”, “defending my company’s interests”, “discussion on the COVID-19 crisis”). Chile faces similar challenges. The Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency noted, for example, that the information disclosed in open boxes that refer to the topics that are to be covered in meetings and hearings (“materias que desea abordar en la Audiencia”) are usually low in quality, which makes it difficult to understand the real reason and purpose of the meeting or hearing.

To enhance the quality of information declared in activity reports, practical guidance explaining how sections on lobbying activities should be completed could be provided for both lobbyists and public officials who have to report information. Good practice from Ireland (Box 3.4) and France (Table 3.7) can serve as examples.

Box 3.4. Guidance provided by the Standards in Public Office Commission in Ireland on how to fill a return

Intended Results:

In this text box, insert sufficient detail on the results you were seeking to secure through your lobbying activity. The intended result should be meaningful, should relate directly to the relevant matter you have cited above, and should identify what it is you are actually seeking. Is it more funding? A regulatory change? It is not sufficient to say that you are seeking “to raise matters of interest to our organisation”. To be a “relevant matter” that must be reported, you must be communicating about:

the development, initiation or modification of any public policy, programme or legislation

the award of any public funding (grants, bursaries, contracts, etc.), or

zoning or development.

Examples:

To ensure greater fines/penalties for persons convicted of illegal dumping.

To increase the maximum allowable speed at which passenger vehicles may operate on Irish motorway.

To improve efficiency of border security processes when travelling between European countries.

To demonstrate the benefits of our community program in order to seek continued/additional funding.

To rezone a tract of land adjacent to my business from residential to commercial.

Source: Standards in Public Office Commission, https://www.lobbying.ie/media/6044/sample-return-form-march-2016.pdf

Table 3.7. Guidance provided by the HATVP on filling the open box “objective pursued” in France

|

1. The purpose should be understood as the “objective sought” and not as the “topic addressed” or “subject matter”. The description of the purpose should as far as possible answer the following question: what was the purpose of the interest representation / lobbying actions carried out? |

|

|---|---|

|

Do’s |

Don’ts |

“Lowering the contribution rate by...” “Extend the application of such provision to..” “Postpone the entry into force of...”

“Reform of vocational training: increasing the ceiling of the personal training account for training account for people without qualifications”. “Social Security Financing Bill 2018: ask for the tabling of an amendment in favour of extending the length of paternity leave and better remuneration”. “Modify the procedures for obtaining AOCs, PDO and PGI in the wine sector to take into account the specificities of the terroir”. “Obtaining the classification of a lake as a protected site”. |

“Promotion and defence of the interests of the sectors ...” “Protection of the environment” “Consumer protection” “Reflection on new digital uses”

“Monitoring, legislative follow-up, organisation of meetings” “Sending a letter” |

|

2. Each object, understood as an “objective”, should be the subject of an activity sheet The object is the entry point for declaring an interest representation activity. Each object should therefore give rise to a separate activity sheet. For example, if an interest representative enters into communication with a public official in order to influence a broad text or to discuss a wide range of subjects, this meeting should be split up according to the different objectives pursued. |

|

|

Do’s |

Don’ts |

|

“Financing Bill: lowering the reimbursement threshold...” “Finance Bill: get recognition for ...” “Finance Bill: raise awareness of the need for ...” |

“PLF: three amendments tabled” |

|

3. Indicate in the subject line the public decision targeted By providing information on the public decision targeted by interest representation activities, it enables to contextualise the interest representation action and make it more intelligible, particularly when it is a text/bill known to the general public. The exact title of the decision, text or bill is not expected, but it may be relevant to indicate its common name or its general theme (for example, “the bill for the freedom to choose one's professional future” can be reworded as “reform of vocational training” or “professional future law”; “training reform” or “professional future law”). |

|

|

Do’s |

Don’ts |

|

“Protection of business secrecy: review the obligations ...” “New rail pact: simplify the criteria for obtaining ...” “Immigration law: make a case for ...” |

Declare only the public decision targeted without specifying the objective pursued: “Transposition of the MiFID II Directive” “Law for a Digital Republic” “Constitutional reform”. |

|

4. When it seems difficult to formulate a purpose that clearly describes the objective, use the “observations” box to describe this action Sometimes it can be complicated to clearly describe the objective of an interest representation activity. In this case, the optional field "observations" can be used to provide more information. |

|

Source: High Authority for Transparency in public life, Guidance note “How to fill the ‘object’ section of an activity sheet?”, https://www.hatvp.fr/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/fiche-pratique-objet-sept-18.pdf

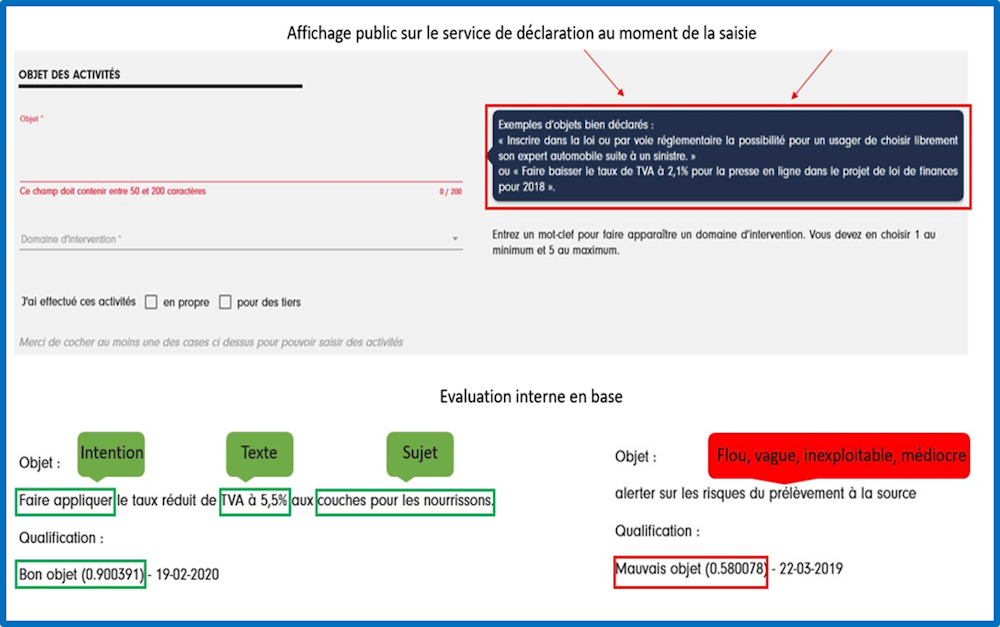

Second, using data analytics to strengthen the quality of the input has also proven useful in other OECD countries. For example, the HATVP established an algorithm based on artificial intelligence to detect potential defects upon validation of the activity report, including incomplete or misleading declarations. Concretely, when completing the “objective pursued” section of an activity report, lobbyists are nudged to provide specific details, including the subject on which the lobbying action bore, the expected results – using at least on positioned verb (“request”, “promote”, “oppose”, “reduce”) – and the public decision(s) targeted by the activities concerned (Figure 3.8). If the return they submit does not meet the established criteria of the algorithm, lobbyists are notified through a pop-up window indicating that that the information entered does not meet the established criteria. It also provides guidance and good practice examples. Lobbyists then have the possibility to modify the information disclosed in the section.

Figure 3.8. Using data analytics to improve the quality of lobbying disclosures in France

Public display on the dedicated disclosure service at the time of entry

Note: The screen shot shows examples of good responses that would be accepted by the system (for example: “include in the law or by regulation the possibility for a user to freely choose his or her car expert following an accident”, “lowering the VAT rate to 2.1% for the online press in the 2018 Finance Bill”, “apply the reduced VAT rate of 5.5% to nappies for infants”) and vague responses that would not be accepted by the system” (e.g. “alerting to the risks of the withholding tax”).

Source: Information provided by the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life

3.5. Centralising lobbying information in a unique and intuitive online Lobbying Transparency Portal

3.5.1. Information from all lobbying registers could be combined in a unique Lobbying Transparency Portal, with information available in an open data format