This chapter presents the analytical framework for a territorial approach to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), stressing the potential of the SDGs as a tool for implementing a new local and regional development paradigm. It argues that the 2030 Agenda should not be considered as an agenda in addition to all the others, but as a framework to shape, improve and implement regions’ and cities’ visions, strategies and plans. It analyses how cities and regions are using the SDGs to develop new plans and strategies or adapt and assess existing ones. The chapter also includes highlights from an OECD-Committee of the Regions survey, analysing the level of awareness, actions and tools, sectoral priorities and main challenges of cities and regions addressing the SDGs. The chapter also explains the need for granular data to measure progress on the SDGs, presenting the experiences of the nine pilot cities and regions of the OECD programme A Territorial Approach to the SDGs.

A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals

Chapter 1. A territorial approach to the Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

A territorial approach to the SDGs: The analytical framework

Why a territorial approach to the SDGs

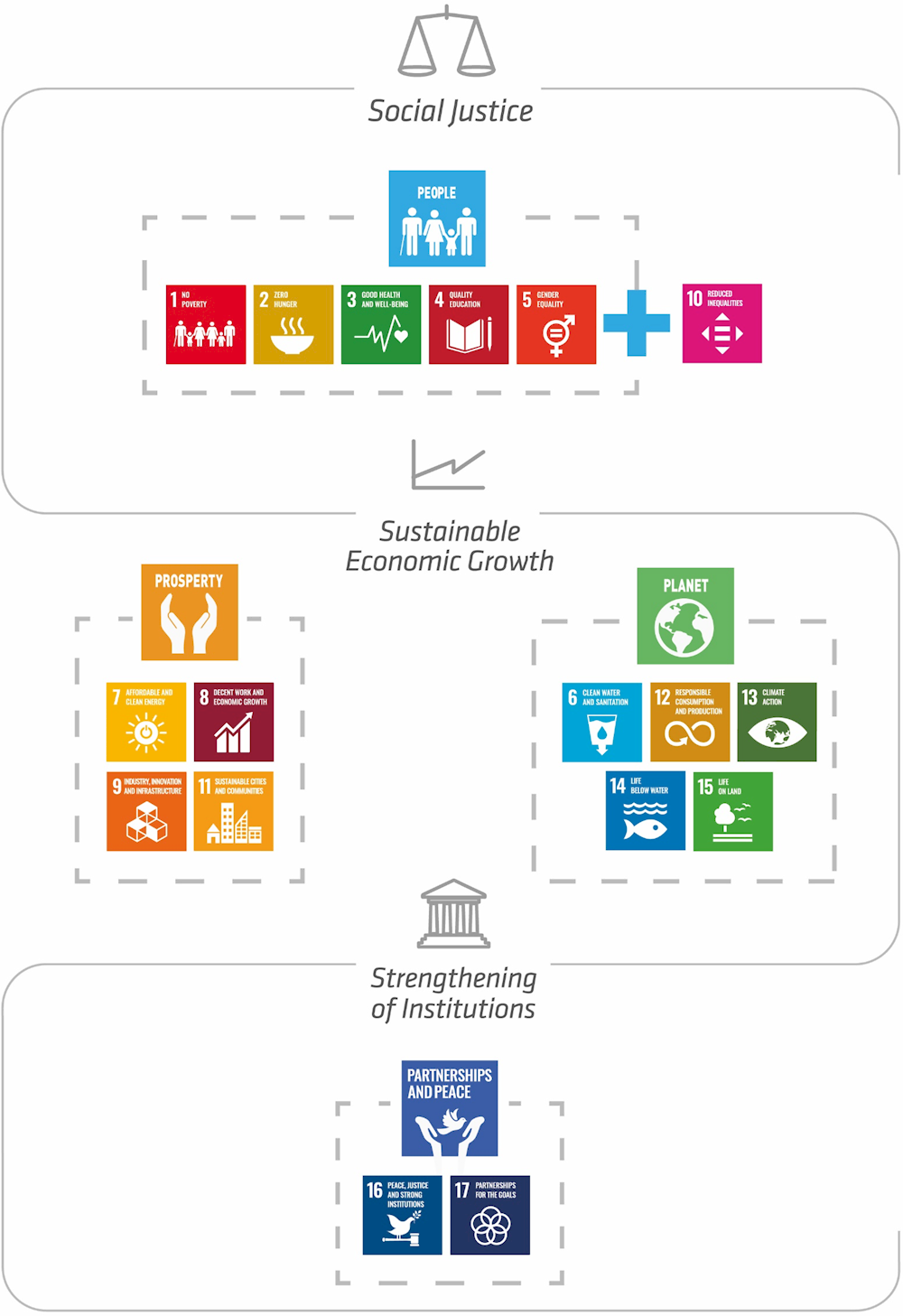

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, set the global agenda for the next 15 years to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all. The 17 SDGs and related 169 aspirational global targets are action-oriented, global in nature and universally applicable (Figure 1.1). The SDGs aim to reach environmental sustainability, social inclusion and economic development in both OECD and non-OECD countries. The SDGs are included in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda, in addition to the 17 SDGs, includes: i) a political declaration; ii) the means of implementation; and iii) a framework for follow-up and review of the agenda.

The 17 SDGs are very comprehensive in their scope and cover all policy domains that are critical for sustainable growth and development. They are also strongly interconnected (meaning that progress in one area generates positive spill-overs in other domains) and require both coherence in policy design and implementation, and multi-stakeholder engagement to reach standards in shared responsibilities across multiple actors. The implementation of SDGs should, therefore, be considered in a systemic way and rely on a whole-of-society approach for citizens to fully reap expected benefits.

Figure 1.1. The Global Goals for Sustainable Development (2015-30)

Source: UN (n.d.), About the Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations, www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals.

The universal nature of the 2030 Agenda is one of its key innovative elements compared to previous global frameworks. The SDGs follow the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which aimed at eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, promoting gender equality and reducing child mortality over 2000-15. The key difference between the SDGs and the MDGs is that the former are universal and apply both to developed and developing countries, while the latter were an agenda for developing countries.

Although the 2030 Agenda was not designed specifically for or by them, cities and regions play a crucial role to achieve the SDGs. The OECD estimates that at least 100 of the 169 targets underlying the 17 SDGs will not be reached without proper engagement and co‑ordination with local and regional governments (see Chapter 2). Regardless of the level of decentralisation across countries, cities and regions have core responsibilities in policies that are central to sustainable development and people’s well‑being. They range from water services to housing, transport, infrastructure, land use, drinking water and sanitation, energy efficiency and climate change, amongst others. They also discharge a significant share of public investment, which is critical to channel the required funding to meet the SDGs and targets. Indeed, subnational governments are responsible for almost 60% of total public investment in the OECD region (OECD/UCLG, 2016) and for almost 40% worldwide; and more specifically they are responsible for 64% and 55% of environment and climate-related public investment and spending respectively (OECD, 2019b).

Although the SDGs provide a global framework to drive better policies for better lives, the opportunities and challenges for sustainable development vary significantly across and within countries. For example, regarding SDG 13 on Climate Action, some cities and regions are more vulnerable to climate change impacts than others. The global warming at 1.5°C may expose 350 million more people to deadly heat by 2050 (IPCC, 2018), exacerbated by local heat island effects. In Europe, 70% of the largest cities have areas that are less than 10 meters above sea level (OECD, 2010), thus exposed to higher risks of flooding. Cities are responsible for almost two-thirds of global energy demand and over 70% of energy-related CO2 emissions (IEA, 2016), produce up to 80% of greenhouse gas emissions and generate 50% of global waste (UNEP, 2017). But cities are also part of the solution. For example, while transitioning from linear to circular economy, cities contribute to keeping the value of resources at its highest level, while decreasing pollution and increasing the share of recyclable materials. The varying nature of challenges related to sustainable development within countries calls for place-based solutions that are tailored to territorial specificities, needs and capacities now and in the future.

Acknowledging that the SDGs provide unique opportunities to strengthen multi-level governance in countries, more and more national governments use them as a framework to promote better policy co‑operation across levels of government. The SDGs framework provides a common foundation and language to leverage the opportunities to engage cities and regions in monitoring and data collection in many countries, aligning priorities and rethinking sustainable development from the ground up. The SDGs can help align priorities in areas such as climate change, social inclusion, health, education, transport, infrastructure and sustainable mobility, energy, business development, among others. In practice, this means ensuring that decisions taken across levels of government on public policies do not work against each other, can be tailored to specific needs in places, and ultimately contribute to drive opportunities for all and ensure no-one is left behind.

Advancing and implementing the OECD New Regional Development Paradigm for Cities and Regions through the SDGs

The SDGs represent a key tool to advance and implement a new local and regional development paradigm to promote sustainability in cities and regions (Table 1.1). Over the last three decades, the OECD has argued that the combination of factors leading to poor socioeconomic and environmental performance is usually context-specific and needs to be tackled through place-based policies (OECD, 2019). This is why regional development policy has a critical role to play in addressing the root causes of persistent territorial disparities.

Place-based policies incorporate a set of co-ordinated actions specifically designed for a particular city or region. Place-based policies stress the need to shift from a sectoral to a multi-sectoral approach, from one-size-fits-all to context-specific measures and interventions, from a top-down to a bottom-up approach to policymaking and implementation. They are based on the idea of policy co‑ordination across sectors and multi-level governance, whereby all levels of government, as well as non-state actors, should play a role in the policy process. They consider and analyse functional territories, in addition to administrative areas. They build on the endogenous development potential of each territory and use a wide range of instruments and actions, including targeted investment in human capital, infrastructure investments, support for business development and research and innovation, among others (OECD, 2019).

The SDGs can help to both advance conceptually the shift towards a new regional development paradigm and, in particular, provide a framework to implement it because:

The 2030 Agenda provides a long-term vision for strategies, plans and policies with a clear and common milestone in 2030, while acknowledging that targeted action is needed in different places since their exposure to challenges and risk vary widely within countries, and so does their capacity to cope with them.

The 17 interconnected SDGs cover the social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development in a balanced way and therefore allow policymakers to better address them concomitantly, building on the synergies and interlinkages, and taking into account the positive and negative impacts of such linkages.

The interconnected SDGs framework allows the promotion of policy complementarities and the management of trade-offs across goals in addition to cities and regions using the SDGs to set their priorities.

The SDGs allow to better implement the concept of functional territories. They represent a common framework that neighbouring municipalities can use to strengthen collaborations and to co‑ordinate actions and can, therefore, provide for a common language and narrative to support territorial reforms.

The SDGs can be used as a powerful tool to promote multi-level governance, partnerships with all stakeholders, including the private sector – extremely active on the SDGs –, and to engage civil society and less traditional stakeholders in the policymaking processes, strengthening accountability.

Table 1.1. Implementing the new OECD Regional Development Paradigm through the SDGs

|

Traditional approach |

OECD New Regional Development Paradigm (2019) |

New SDGs Development Paradigm for Cities and Regions |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Problem recognition |

Regional disparities in income, infrastructure stock and employment |

Low productivity (levels and growth); underused regional potential; lack of regional competitiveness; inter-regional and inter-personal inequality |

Lack of an integrated approach to sustainable development, sectoral bias still persists |

|

Objectives |

Equity through balanced regional development |

Increasing productivity growth; delivering high‑quality of life and well-being to people across economic, social and environmental dimensions |

Integrating competitiveness, equity and environmental dimension to promote people’s well-being following the five “Ps” of the 2030 Agenda: people, prosperity, planet, peace and partnerships |

|

General policy framework |

Compensating temporally for location disadvantages of lagging regions, responding to shocks (e.g. industrial decline) |

Tapping underutilised regional potential through regional programming; building on existing strengths; developing regional innovation systems |

Tapping underutilised regional potentials through regional programming; building on existing strengths to rethink strategies from the group up; developing regional innovation to achieve the SDGs |

|

Theme coverage |

Sectoral approach |

Integrated development projects for economic growth |

Integrated approach using the SDGs to identify priorities while maximising synergies and managing trade-off across sectors |

|

Spatial orientation |

Targeted at lagging regions |

All-regions focus with policies adapted to each region |

All-regions focus with policies adapted to each region |

|

Unit for policy intervention |

Administrative areas |

Both administrative and functional areas |

Combining administrative and functional areas |

|

Time dimension |

Short term |

Long term |

Long term, with 2030 as a key milestone |

|

Approach |

One-size-fits-all |

Place-based approach |

Place-based approach within a global common framework |

|

Data/Indicators |

Focus on gross domestic product (GDP), mainly economic indicators |

Well-being indicators |

SDGs indicator framework |

|

Focus |

Exogenous investments and transfers |

Endogenous development based on local assets and knowledge |

Combining endogenous and exogenous focus – SDGs to attract exogenous investments and value local assets |

|

Instruments |

Subsidies and state aid (often to individual firms) |

Broad range of instruments: targeted investment in human capital; infrastructure investments; support for business development; research and innovation support; co-ordination between non-governmental actors |

Broad range of instruments: targeted investment in human capital; infrastructure investments; support for business development and research and innovation for SDGs challenges; public procurement and de-risking private investments to support the engagement of private sector in SDGs |

|

Governance |

Mainly central government |

Different levels of governments, various stakeholders (public, private, non-governmental organisations [NGOs]) |

SDGs as a key framework to promote multi-level governance and engage all territorial stakeholders |

|

Role of the private sector |

Disconnected from the public sector |

Public-private partnerships |

SDGs as a key tool to promote public-private collaborations, with private sector extremely active on SDGs beyond Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) |

|

Role of the civil society |

Civil society as an untapped potential |

Civil society started being engaged in the policymaking process |

Civil society as a key actor to achieve the SDGs, in particular students/youth; proactive role of citizens |

Source: Revised and adapted from OECD (2019a), “OECD Regional Outlook 2019: Leveraging Megatrends for Cities and Rural Areas”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264312838-en.

SDGs as an enabler to fit for the future

The SDGs provide a forward-looking vision for governments to consider, anticipate and respond to some global changes and trends that impact and shape the policy environment. Four critical megatrends influencing the achievement of the SDGs in cities and regions are herein identified: i) demographic changes, in particular urbanisation, ageing and migration; ii) climate change and the need to transition to low-carbon economy; iii) technological changes, such as digitalisation and the emergence of artificial intelligence; and iv) the geography of discontent. The impact of these four megatrends on people and societies is very much context-specific and therefore requires place-based policies to effectively respond, minimise their potential negative impact on regional disparities and capture the opportunities related to those trends locally.

Demography

Urbanisation continues to grow all over the world, with cities accounting for over 80% of global GDP today and projected to house 70% of the global population by 2050 (UN‑Habitat, 2016). In OECD countries, the urban population has grown by 12% since 2000, with the largest cities experiencing growth that is even more pronounced. Between 2006 and 2016, 81% of young people (age 15-29) who moved within the same country settled in an urban or intermediate region (OECD, 2019a). This makes cities hotspots for inequalities and environmental stresses, with negative externalities on surrounding areas. Income inequality – which has been rising in the last decades – is higher, on average, in cities than in their respective countries. The health implications of inequalities in cities are also striking: while the richest 40% of urban dwellers are likely to reach the age of 70 or more, the poorest struggle to reach 55 years (UN-Habitat, 2015).

The SDGs can help to design and implement a more balanced and sustainable urban development model. The integrated framework of the SDGs allows analysing the key drivers of urban development in a holistic way and managing possible trade-offs among them. For example, combining urban development with sustainable transport and mobility is often one of the main challenges for cities. Energy-efficient building standards, provision of clean and affordable energy (SDG 7) and low-carbon means of transport are key to meet the required CO2 emission standards (SDG 13) while at the same time developing the city sustainably (SDG 11). Moreover, education (SDG 4) is central to keep the employment rate high (SDG 8) in a labour market characterised by high-skilled jobs. Cities can use the SDGs to analyse and address interlinked challenges.

An ageing population is another megatrend challenging many OECD countries. The number of people aged 65 or older per 100 people of working age has increased by close to 25% between 2000 and 2015 and is expected to increase by another 25% by 2050. Ageing will have a very concrete impact on policies that should strive to leave no-one behind, for instance pensions systems and the provision of public services, in particular in rural areas that are mostly affected by this megatrend and by the outflows of young people. Cities and regions should, therefore, provide the necessary infrastructures and services to support the ageing populations as well as to develop strategies to build age-friendly communities (OECD, 2019a).

The SDGs can help to identify new opportunities, both for the elderly population and for youth, and to promote social cohesion through intergenerational solidarity. For example, the city of Kitakyushu is using its strong environmental SDGs to create opportunities in the economic and social SDGs. Some economic sectors connected to the environmental dimension, such as eco-industry offshore wind power generation, eco-tourism, or culture could offer additional job opportunities both to youth (preventing further population decline) and the elderly population, promoting social cohesion through intergenerational solidarity.

Migration, both domestic and international, is the third demographic megatrend with a strong impact on the sustainable development of cities and regions. Domestically, rural-urban migration is increasing, both in OECD and particular in non-OECD countries, and is contributing to global urbanisation and the decline of population in rural areas. International migration is a key driver of demographic change. International migrants are mainly concentrating in large cities because they tend to offer the most favourable labour market opportunities. Cities and regions should implement adequate place-based integration policies to fully seize the potential and benefits of migration while ensuring local integration of migrants across places and involving various stakeholders and different levels of government.

The SDGs can help to better analyse the causes of migration and identify possible opportunities for migrants in urban areas. The SDGs provide a framework to better analyse the interconnected causes of rural-urban migration and provide multi-sectoral policy responses. Regarding international migration, cities can use the SDGs as a tool to promote city-to-city co‑operation (in OECD and in developing countries) and co-design measures to address both the root causes of migration in developing countries and the solutions for migrants’ integration in OECD cities.

Climate change

Climate change is one of the most pressing megatrends with impacts, challenges and opportunities varying significantly across territories within and across OECD countries. Some cities and regions are more vulnerable to climate change impacts than others. The global warming at 1.5°C may expose 350 million more people to deadly heat by 2050 (IPCC, 2018), exacerbated by local heat island effects. In Europe, 70% of the largest cities have areas that are less than 10 meters above sea level (OECD, 2010), thus exposed to higher risks of flooding. Moreover, cities concentrate almost two-thirds of global energy demand (IEA, 2016), produce up to 80% of greenhouse gas emissions and generate 50% of global waste (UNEP, 2017). Nevertheless, cities are also part of the solution. Subnational governments are responsible for 57% of all public investment and 64% of all climate-related public investments. Moreover, while transitioning from linear to circular economy, cities contribute to keeping the value of resources at its highest level, while decreasing pollution and increasing the share of recyclable materials.

The SDGs can help to prioritise climate goals and address them in conjunction with the social and economic pillars of sustainable development rather than in isolation. When cities and regions prioritise social or economic goals, the SDGs can help to still consider the effect on the environment and avoid overlooking climate objectives. Looking at the policy complementarities among climate and social/economic goals is key. For example, climate mitigation policies (e.g. reducing CO2 emissions from private cars) can generate important local co-benefits, such as improvements in air quality (SDG 11) and avoided health cost (SDG 3). However, climate policies may also negatively affect other policy goals such as social inclusion (SDG 10). While some climate-related investments (e.g. retrofitting buildings) can generate positive impacts for low-income and vulnerable populations (e.g. lower energy bills, improved housing quality), other instruments such as carbon taxes or congestion charges may affect them disproportionately. This is why by conceiving climate and inclusion policies in tandem at a very local scale, governments can reap the benefits of policy complementarities (OECD, 2019a).

Digitalisation and the future of work

The impact, benefits and risks of digitalisation are strongly context-specific. In terms of benefits, digitalisation will reduce the costs of trading goods, ideas as well as the physical interactions for firms and people. Digital technologies will also improve access to services both for companies and workers, changing the geography of labour as the benefit of proximity might be reduced for some jobs. At the same time, digitalisation might strongly impact local labour markets and generate high rates of unemployment, if adequate place-based policies to adapt to the new technologies are not in place. Across the OECD, 14% of jobs are at high risk of automation, with more than 70% of tasks performed by workers expected to be replaceable within the coming decades. Across OECD regions, it varies from 4% to 40%. The gap between the region with the highest and lowest risk can be as wide as 12 percentage points within countries (OECD, 2019a).

The SDGs can help to link the potential benefits and risks of digitalisation to inclusive growth and well-being, connecting smart and sustainable cities. The core idea is to provide digital solutions that help advance urban sustainable development. For instance, there is great potential to use advanced technologies to measure at a granular level (e.g. use of mobile operators or other technology to measure the quality of air and water) to better estimate some SDGs indicators. Similarly, there is a large push from the local governments to digitalise many services related to health, education or environmental participation, which can have an impact on achieving some of the SDGs.

Geography of discontent

The emergence of the so-called “geography of discontent” is another factor that can make the SDGs a valuable tool for more inclusive and people-centred policymaking. High unemployment, low wage growth and other symptoms of poor socioeconomic performance have led to growing public discontent with the political and economic status quo. In parallel and since the 2008 global financial crisis, there has been a growing mistrust from citizens about the capacity of their governments to ensure well-being now and in the future. This has generated a pattern in which the degree of discontent reflects the economic performance of a region relative to others in the country. With unchanged policies, unfolding megatrends such as automation will further increase the spatial divides that create this pattern of discontent and likely increase tension while undermining social cohesion (OECD, 2019a).

Local and regional policies have a key role to play and the SDGs can help to better address some of the underlying causes of the discontent, in particular regional disparities. The geography of discontent is a symptom of an underlying policy failure. Too many regions struggle because public policy has not responded adequately to their problems. A focus on aggregate performance at the national level has obscured that struggling regions require distinct solutions. Only if policymakers address this fundamental issue will they be able to deal with the cause behind the geography of discontent (OECD, 2019a).

The SDGs provide a unique opportunity to rethink drastically the design and implementation of public policies, in a shared responsibility across levels of government and stakeholders to foster greater accountability, equity, inclusion and cohesion now and in the future. The SDGs are also a powerful tool to engage citizens in the policymaking process. This will contribute to addressing some of the root causes of the geography of discontent in a place-based manner.

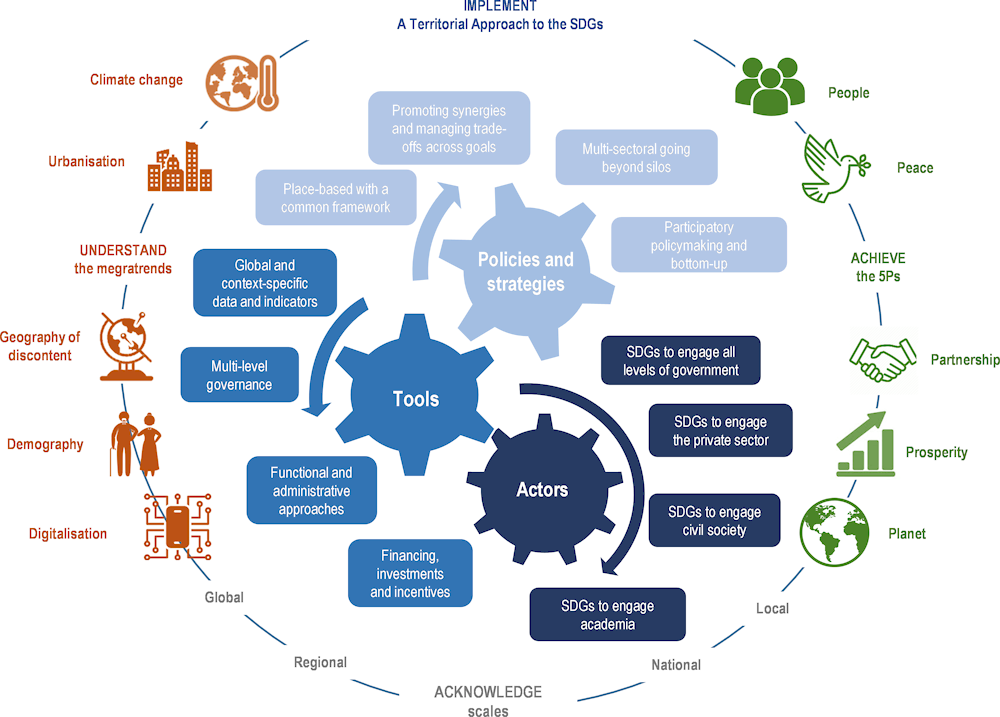

The analytical framework: Key dimensions for the implementation of a territorial approach to the SDGs

Policies and strategies through the SDGs

Regional policy aims to effectively address the diversity of economic, social, demographic, institutional and geographic conditions across cities and regions. It also ensures that a wide range of sectoral policies, from transport and education to innovation and health, are co‑ordinated with each other and meet the specific needs of different regions across a country – from remote rural areas to the largest cities. Regional policy targets specific territories and provides the tools that traditional structural policies often lack in order to address the region-specific factors that cause economic and social stagnation (OECD, 2019a).

Cities and regions can use the SDGs as a means to shift from a sectoral to a multi-sectoral approach, both in the design and particularly in the implementation of their strategies and policies. The importance of a multi-sectoral approach and the need to go beyond silos is well recognised in local and regional development policies. On paper, various strategies, plans and policies are designed in a holistic way, but when it comes to the implementation, a sectoral approach often still prevails. The framework provided by the SDGs can help to bring various departments of a local administration together and strengthen the collaboration in implementing the strategies and policies. This is particularly true when it comes to sustainable development, which is a shared responsibility across levels of government, citizens, civil society and the private sector.

The SDGs represent a powerful tool to promote the issues of sustainability in a holistic way. The 2030 Agenda is based on the concept of policy coherence and it promotes synergies between the environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainable development. The SDGs universal, indivisible and interlinked framework can help regions, cities and national governments to address social and economic goals while pursuing the environmental and climate objectives (or vice versa, pursuing environmental goals that do not undermine growth and social cohesion), including through the engagement of a wide range of stakeholders in the policy responses.

Policy debates have tended to focus on the trade-offs among SDGs, often overlooking potential synergies. There is a growing awareness of the need to pursue the three pillars of sustainable development in a more balanced and complementary way. Such a system entails that every policy is reinforced through other policies. When it comes to addressing concerns of environmental sustainability and equity alongside growth objectives rather than as subsidiary goals, a differentiated approach taking into account the specific conditions in each city and region can help us understand trade-offs or potential complementarities among the three objectives (OECD, 2011).

Place-based policies are well equipped to promote synergies across the SDGs at the scale where they are most relevant and evident, in particular places, as opposed to policies that are “spatially blind”. It is at the territorial level that it is most effective to implement a multi-sectoral approach based on the context-specific priorities, needs, challenges and opportunities. Various cities and regions are identifying their priorities, sometimes at goal level, sometimes at the target level. Although they are prioritising some SDGs, subnational governments recognise the importance of interlinkages among goals and are therefore developing approaches and methodologies to identify and measure those synergies in a more systematic way.

Figure 1.2. Analytical Framework for a Territorial Approach to the SDGs

Key actors to implement a territorial approach to the SDGs

A participatory policymaking and bottom-up process is one of the core elements of a territorial approach to the SDGs. Shifting from a top-down and hierarchical to a bottom-up and participatory approach to policymaking and implementation is key for the achievement of the SDGs. The 2030 Agenda requires a more transparent and inclusive model that involves public as well as non-state actors (private sector, not-for-profit organisations, academia, citizens, etc.) to co-design and jointly implement local development strategies and policies.

Being a shared responsibility, the SDGs provide cities and regions with a tool to effectively engage in multi-stakeholder dialogue with actors from the private sector, civil society, as well as schools and academia:

Businesses that go beyond corporate social responsibility and invest seriously in sustainable development have an essential role to play in achieving the 2030 Agenda. Current levels of public investment will not be sufficient to catalyse the USD 6.3 trillion required to meet the 2030 Agenda infrastructure needs, and innovative financing sources will be instrumental. The perspective of the private sector and investors is often absent in the process of defining sustainable city development plans and strategies. This leads to a mismatch in priorities, barriers to implementation and missed opportunities to create shared value and impact. Including the private-sector perspective early on in the development process will help to bridge existing gaps between the public sector and private solution providers and investors. The SDGs can be a tool to bridge the gap between the public and private sectors and align priorities for effective implementation.

Civil society, citizens and in particular youth are key agents for change towards sustainability. The civil society organisations have an important role to play both as a driver to achieve progress towards the SDGs and by holding governments at all levels accountable for their commitments towards the 2030 Agenda. Civil society is also a key player in traditional policymaking processes, including in formal consultations. Informed citizens can also change their daily habits in view of sustainability. Behavioural change of citizens is often a key component for achieving the intended policy outcomes, for example in sectors such as transport and mobility, water and waste management, sustainable consumption and production. Youth, including through youth councils, are also more and more engaged with the 2030 Agenda with an increasing number of schools introducing the SDGs into the curricula.

Universities are also more and more active on the SDGs. The role of universities is particularly relevant when it comes to collaborating with the governments and community, including at the local level. Universities can support governments at all levels by generating and disseminating the knowledge required to address the SDGs, by co-designing policies and strategies, by monitoring and evaluating policies and progress, by educating, training and providing the necessary skills to students (future leaders) on sustainable development integrating the SDGs into curricula (El-Jardali et al., 2018). Lately, several networks and initiatives of universities addressing the 2030 Agenda are emerging, such as the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Higher Education Sustainability Initiative and Principles of Responsible Management Education initiative. The Australia, New Zealand & Pacific Network of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) has also produced a guide on how universities can contribute to the SDGs.

Tools for the implementation of a territorial approach to the SDGs

The effective implementation of a territorial approach to the SDGs implies the combined use of a variety of tools. These span from a solid multi-level governance system, to global and context-specific data for evidence-based policies and actions, from combining functional and administrative approaches to address territorial challenges and opportunities beyond borders to soft and hard investment and incentives, in particular for the private sector.

Multi-level governance represents a key tool to promote vertical – across levels of government – and horizontal co‑ordination – both within the government and between the government and the other key stakeholders, such as the private sector, civil society and academia. National governments can use the SDGs as a framework to promote policy coherence across levels of government, align priorities and rethink sustainable development through a bottom-up approach.

Cities and regions can use a range of soft and hard instruments and investments to promote the implementation of the SDGs locally. These span from targeted investments in human capital to adapt the human resources to the SDGs challenges, to infrastructure investments for more sustainable and smart cities (e.g. improving transport and mobility, housing, energy efficiency), to support for business development and research and innovation for SDGs challenges. In addition, the public sector can use some tools to incentivise the private sector to move towards the SDGs, such as sustainable public procurement, de-risking private investments to experiment innovative products/solutions for the SDGs, establishing a platform to co‑ordinate small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) working on the SDGs and raising awareness among citizens to strengthen the demand for sustainable production and consumption.

A territorial approach to the SDGs implies looking beyond administrative boundaries and focusing on functional areas to make the most of the interlinkages between core cities and their surrounding commuting zones, and between rural and urban areas. Promoting sustainable development requires analysing challenges and identifying policy solutions both at an administrative and at a functional scale. Effective policies and strategies to achieve the SDGs should be co-ordinated across administrative boundaries to cover the entire functional area (OECD, 2019). For example, a functional approach allows for better analysis and provision of policy solutions to issues such as transport, waste management, climate change adaptation and the dynamics of the labour market that goes beyond the administrative boundaries of a city.

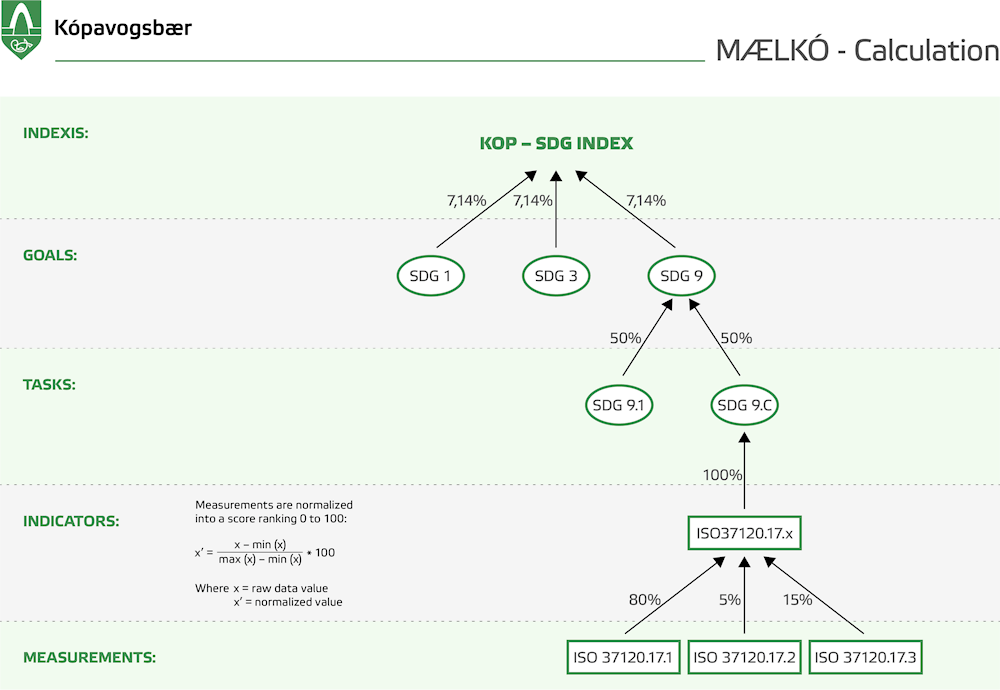

Measuring SDGs progress is a key priority to allow cities, regions and national governments to identify the main gaps and possible policy solutions to achieve the targets by 2030. The SDGs indicator framework offers a window of opportunity to strengthen national and subnational statistical systems, which can, in turn, serve as a tool for dialogue and action for better policies. Two key messages for measuring progress on the SDGs are:

The need to combine and integrate a global indicator framework with context-specific data. This will help cities and regions to measure where they stand vis-a-vis their peers across and within countries and their distance to targets, the latter better describing the local conditions and adding more detailed information that is not captured in the global framework.

The importance of measuring progress both at the functional and administrative levels. The functional approach (e.g. functional urban areas, defined according to where people work and live) is extremely useful to measure outcomes in policy domains that are place-sensitive, span across administrative boundaries and require understanding the economic dynamics of the contiguous territories. At the same time, it is important to measure SDGs progress within administrative (politically-defined) boundaries, including for data availability and consistency with local official statistics.

Making the most of the transformative nature of Agenda 2030

The 2030 Agenda calls for transformation to achieve the global targets set by the SDGs. Concretely, the 2030 Agenda states: “We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world onto a sustainable and resilient path” (p. 5, UN, 2015). Thus, the agenda urges to find new development models that help to advance the social, economic and environmental agenda and manage trade-offs among them.

New analytical frameworks to embrace the transformative element of the 2030 Agenda are flourishing at the international level. The international research community is producing evidence to help governments rethink their current approaches to public policies:

Six SDG transformations: Sachs et al. (2019) claim that the six transformations provide an integrated and holistic framework for action that reduces the complexity, yet encompasses the 17 SDGs, their 169 targets and the Paris Agreement. In particular, they identify six SDGs transformations as building-blocks: i) education, gender and inequality; ii) health, well-being and demography; iii) energy decarbonisation and sustainable industry; iv) sustainable food, land, water and oceans; v) sustainable cities and communities; and vi) digital revolution for sustainable development. Each transformation identifies priority investments and regulatory challenges, calling for actions by well-defined parts of government working with business and civil society.

Planetary boundaries: This framework aims to define the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate in the world. Steffen et al. (2015) call for a new development paradigm that integrates the continued development of human societies and the maintenance of the Earth system in a resilient and accommodating state. Since its introduction, the framework has been subject to scientific scrutiny and has attracted considerable interest and discussions within the policy, governance and business sectors as an approach to inform efforts toward global sustainability, in particular in Nordic countries.

However, governments and other organisations are still struggling to fully embrace the transformative element of the agenda. At the national, regional and local levels, a number of governments are mainstreaming the SDGs into their strategies, policies and plans. Although of great value, these initiatives should be coupled with commitments to change existing practices and models, economic, social and environmental, to ensure long-term sustainability. It should also come with approaches to manage trade-offs across sectoral policies, in an attempt to address the 17 SDGs holistically. Private companies are also tempted to map their areas of work and previous corporate social responsibility plans against the SDGs, using it as a marketing tool. However, with respect to the private sector, the transformative element of the agenda calls for redesigning business models, strategies and practices to be fit for the future.

Transformations are long-term complex processes that cannot be bound exclusively to actions taken by governments. While governments at all levels do have a role to create a conducive environment for transformations through conducive legal, regulatory and incentive frameworks, they also need to work with stakeholders at large. The transformative element of the 2030 Agenda can reshape policies to make the most of new opportunities, such as the transition towards a low-carbon economy or new trends in globalisation. Decarbonisation policy poses perhaps one of the most urgent public policy challenges. Environmental policy aimed at improving the impacts of specific products and production activities – through regulatory measures such as energy efficiency and pollution standards and protection of natural areas. These have not been enough to achieve environmental sustainability (especially on greenhouse gas emissions) (OECD/IIASA, 2019). The 2030 Agenda provides an opportunity to reconsider how legal and economic frameworks can be reformulated to drive investments and production into more sustainable and resilient forms, and foster technological developments that trigger such a transition. Similarly, the adoption of international sustainable development objectives (2030 Agenda, Paris Agreement) has opened the debate on the need to rethink trade agreements beyond the sole objective to increase trade to ensure they contribute to the implementation of the international agendas (Hege, 2019).

Key highlights on the contribution of cities and regions to sustainable development: An OECD-CoR survey

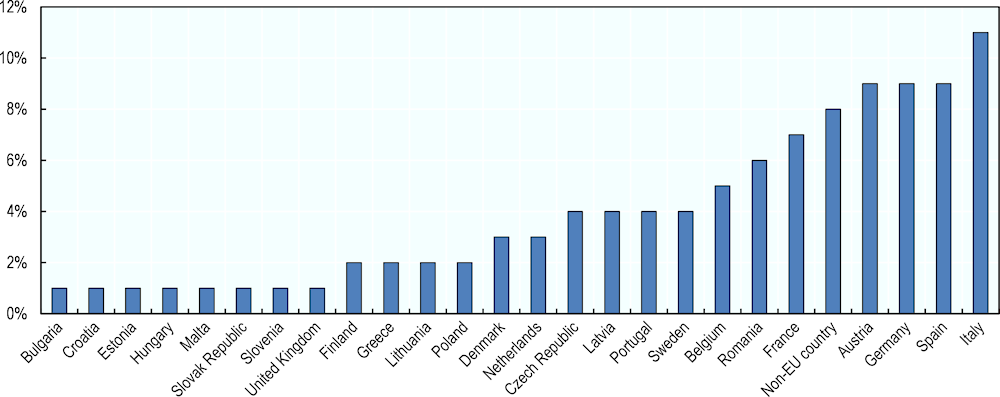

The OECD and the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) conducted a survey on “The key contribution of cities and regions to sustainable development” across cities and regions in European countries (Box 1.1). The survey addressed representatives of local and regional governments as well as other stakeholders at the local and regional levels (400 respondents) to collect examples and evidence about their work on sustainable development and in particular their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Box 1.1. Respondents to the OECD-CoR survey and key findings

From 13 December 2018 to 1 March 2019, the survey gathered answers from 400 respondents from across Europe, 90% of which from European Union (EU) member states and the rest from Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey. A very small number of answers came from non-EU and non-OECD countries.

Many responses were received from municipalities (39%), with 18% of the total sample specifically from small municipalities (under 50 000 inhabitants), 15% from medium-sized cities (50 000 to 500 000 inhabitants) and a further 6% representing large cities (more than 500 000 inhabitants). Significant shares of respondents also represent regions (17%), intermediary entities such as counties or provinces (9%) or other local and regional bodies (10%). The remaining 26% of respondents represent diverse categories of stakeholders such as academia and research or associations, NGOs or public bodies, with a few answers from the private sector and individuals responding in their personal capacity.

The distribution of respondents among countries and levels of government is unbalanced and the respondents do not form a statistically representative sample. The aim of this survey was rather to offer a useful snapshot of the views expressed by diverse local and regional stakeholders regarding the SDGs and their implementation.

Figure 1.3. Country coverage of respondents to the OECD-CoR survey

Key findings of the survey include:

59% of respondents are familiar with the SDGs and currently working to implement them. Among respondents representing cities and regions, this share rises to approximately 79% and 63% respectively. In large or medium-sized cities (more than 50 000 inhabitants), the share is 84% and in small cities (less than 50 000 inhabitants), 37%.

58% of the respondents currently working to implement the SDGs have also defined indicators to measure progress on the goals, with local indicators much more commonly used than those of the EU or the UN.

The most common challenges in implementing the SDGs – highlighted by half of respondents – are the “lack of awareness, support, capacities or trained staff” and “difficulty to prioritise the SDGs over other agendas”.

More than 90% of respondents are in favour of an EU overarching long-term strategy to mainstream the SDGs within all policies and ensure efficient co-ordination across policy areas.

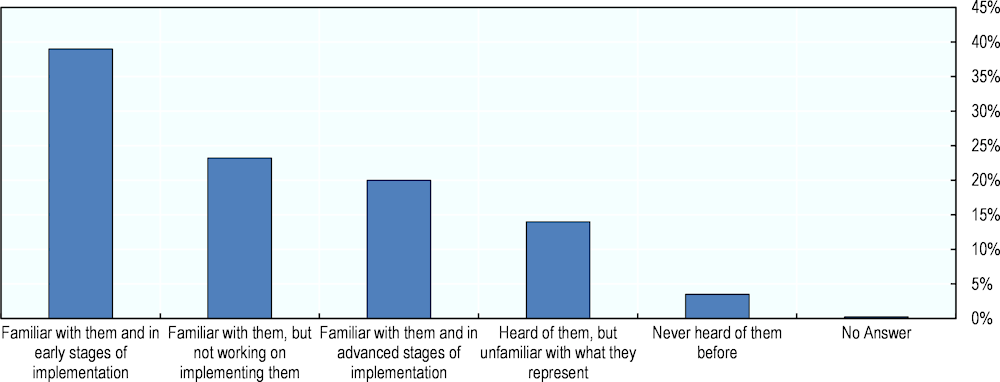

Level of awareness of the SDGs

Overall, respondents to the survey showed a relatively high degree of awareness on the SDGs. Only 18% of respondents were either unaware of or unfamiliar with them. Furthermore, a significant majority (59%) are actually in the process of implementing the SDGs, whether in early or advanced stages (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Level of awareness of the SDGs among cities, regions and stakeholders

Source: OECD/CoR (2019), Survey Results Note - The Key Contribution of Regions and Cities to Sustainable Development, https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf.

The majority of small municipalities have not yet started implementing the SDGs. The 59% share of respondents who are in the process of implementing the SDGs is an overall average that hides some marked differences, in particular according to the category of subnational authority represented. Interestingly, the share of respondents “implementing” the SDGs is distinctly higher than the average for large cities (87%), medium cities (83%) and regions (78%), while it is much lower for smaller municipalities (37%), which would suggest that larger entities are better equipped to work on SDGs implementation.

Policies and actions to implement the SDGs

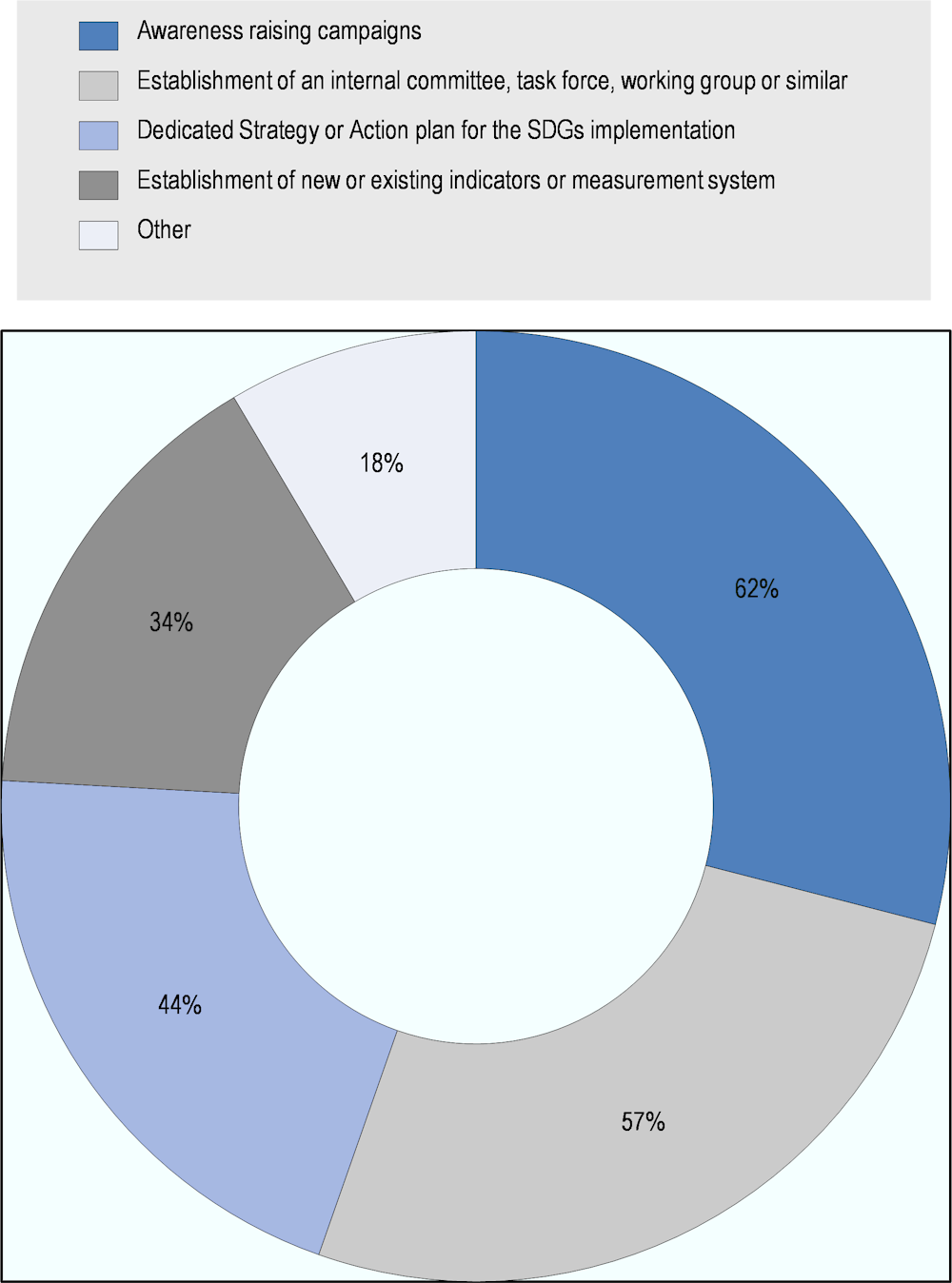

The most common actions put in place to implement the SDGs are awareness-raising campaigns and establishing a dedicated body, selected by 62% and 57% of the respondents respectively (Figure 1.5). Having a dedicated strategy/action plan and establishing indicators are two of the key elements of a relatively advanced stage of implementation of the SDGs and these were selected by 44% and 34% of respondents taking action respectively. Among the “other” actions and policies, many respondents mentioned the integration of the SDGs in the organisations’ plans and strategy, or intentions to do so in the future.

Figure 1.5. Policies and actions for the implementation of the SDGs at the subnational level

Source: OECD/CoR (2019), Survey Results Note - The Key Contribution of Regions and Cities to Sustainable Development, https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf.

Sectoral priorities at the subnational level

Most cities and regions work with the SDGs because they consider them a valuable tool to strengthen regional and local development. Among respondents who are implementing the SDGs, 71% stated the reason is that they “See the SDGs as a transformative agenda” and 66% that they “See the value of the SDGs as a local development planning and budgeting tool”.

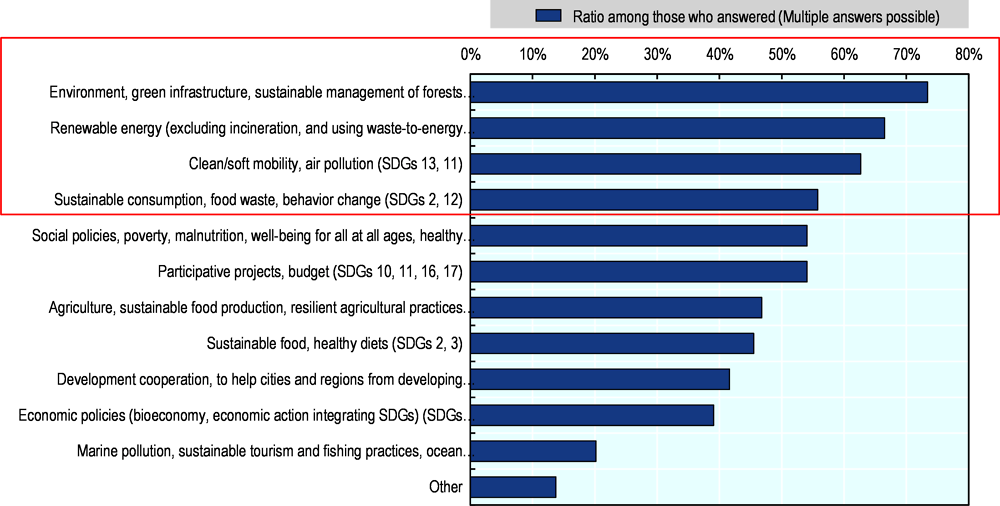

However, from the sample and geographical scope (Europe), a strong emphasis is put on environmental sectors when prioritising actions to implement the SDGs. The most common topic or dimension of the SDGs tackled by respondents is the environment (73%), closely followed by energy (67%) and mobility (63%), with sustainable consumption, social policies and participative projects also scoring high (more than 50% of respondents). The diversity of sectors receiving high scores and the fact that respondents who answered this question selected on average five to six sectors each suggest that the cross-sectoral and multi-faceted nature of sustainability and of the SDGs in particular is well taken into account (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Sectoral priorities in the implementation of the SDGs at the subnational level

Source: OECD/CoR (2019), Survey Results Note - The Key Contribution of Cities and regions to Sustainable Development, https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf.

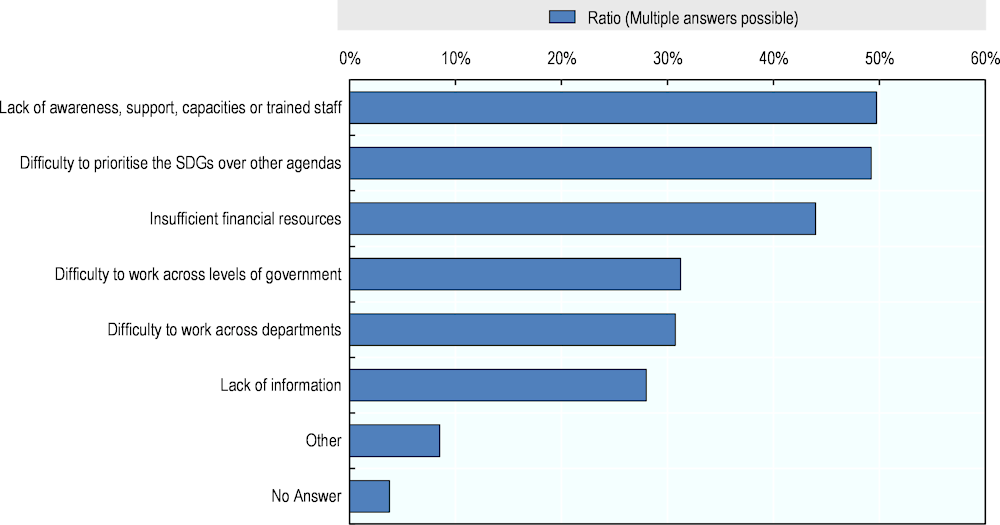

Challenges to implementing the SDGs at the local and regional levels

Key challenges to SDG implementation conveyed by the survey respondents include the “Lack of awareness, support, capacities or trained staff” (50%) and "Difficulty to prioritise the SDGs over other agendas" (49%) (Figure 1.7). Interestingly, the share of respondents citing “Insufficient financial resources” as a challenge is not significantly different among respondents from small municipalities compared to the broader sample. The challenges specified by respondents who selected “Other” include the lack of high-level commitment and follow-up, difficulties in communicating the SDGs, the lack of harmonised data at different levels and the difficulty in defining an appropriate indicator framework. The two latter are particularly relevant to understand the current situation and monitor progress, and thus key to start working on SDGs. For instance, in the region of Flanders, VVSG (Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities) has noted that while they estimate to reach around 65% of all municipalities with their indicator framework, the remaining challenge will be reaching those that are less prone to work with sustainability in the first place.

A total of 49% of respondents mentioned the “Difficulty to prioritise the SDGs over other agendas” as a key challenge, which testifies of the room for improving the understanding of SDGs as a framework to improve strategies, policies and their implementation rather than an additional agenda.

Figure 1.7. Main challenges in implementing the SDGs at the local and regional levels

Source: OECD/CoR (2019), Survey Results Note - The Key Contribution of Regions and Cities to Sustainable Development, https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf.

SDGs indicators at the local and regional levels

Tracking and measuring the progress of cities and regions against the SDGs is an emerging priority for subnational governments. Around 70% of respondents track progress towards the SDGs. Almost 58% of respondents currently implementing the SDGs use indicators to monitor progress. Among all respondents who use indicators, most use local indicators (26%) or national indicators (19%). Fewer than 15% of respondents use EU- or UN-level indicators.

Overall, 40% of all respondents do not use any indicators. It is interesting to note that EU and UN indicators are roughly only half as commonly used as local indicators, which could suggest that they do not necessarily lend themselves to local and regional realities and constraints. In addition, the necessary data is not always available at the NUTS2 level (territorial level corresponding to basic regions of EU countries for the application of regional policies) for the EU indicators for example.

Multi-level and multi-stakeholder co‑operation in implementing the SDGs

Respondents who are implementing the SDGs reported local-regional co‑operation in that regard (60%). This highlights a high degree of co‑operation between the different subnational levels, while answers related to co‑operation with the national level were much less common among respondents (only 23% have joint projects with the national level to implement the SDGs).

In terms of stakeholder engagement and co‑operation, 39% of the respondents highlighted that they mainly co‑operate or have a dialogue with civil society or NGOs, followed by universities and by citizens (both 31%). Moreover, 28% of respondents stated that they already collaborate with the private sector, while 26% signalled that they are planning to.

As stressed by SDG 17, partnerships are fundamental to achieve the SDGs, but this opportunity is not fully exploited yet by subnational governments. Around 60% of all respondents answered “No” to the question “Have you established any formal partnerships (e.g. memorandum of understanding [MoU], purchasing power parity [PPP]) with other public, civil society and/or private sector actors to support the achievement of the SDGs?”. Only 25% of the respondents selected “Yes, within my own region or city” with a further 9% each stating “Yes, with another region or city in their own country”, or “With a city or region in an EU or OECD country” (7%), suggesting that very few subnational governments tackle the “external” function of the SDGs to drive international co‑operation (north-south, north-north or south-south).

Cities’ and regions’ expectations from the EU on SDGs

The survey also analysed what respondents expect from the EU on the SDGs.1 Overall, respondents appear to be clearly in favour of ambitious action at the EU level in relation to the SDGs, including an EU overarching strategy ensuring policy coherence, mainstreaming the SDGs and financial support for sustainable projects. Specifically, between 85% and 95% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with all of the following statements:

The EU should have an overarching long-term strategy to mainstream the SDGs within all policies and ensure efficient co‑ordination across policy areas.

A framework for policy coherence will be one of the essential objectives and aspects of an EU strategy on the SDGs.

All of the EU institutions should break silo-thinking and mainstream the SDGs internally across all structures, and ensure policy coherence.

The EU should have a financial mechanism dedicated to finance sustainable projects.

The EU – through the European Commission – should strongly promote sustainable public spending and finance more sustainability-proof projects.

A large share of the respondents (66%) are in support of fiscal reforms, possibly including an EU tax to enhance sustainability at all levels. Regarding the possibility that the European Semester will be used to plan monitor and evaluate SDGs implementation in the EU, respondents were predominantly supportive (72% agree or strongly agree). Similar results were obtained regarding the possibility of using the “Better Regulation Agenda” to mainstream the SDGs within all EU policies.

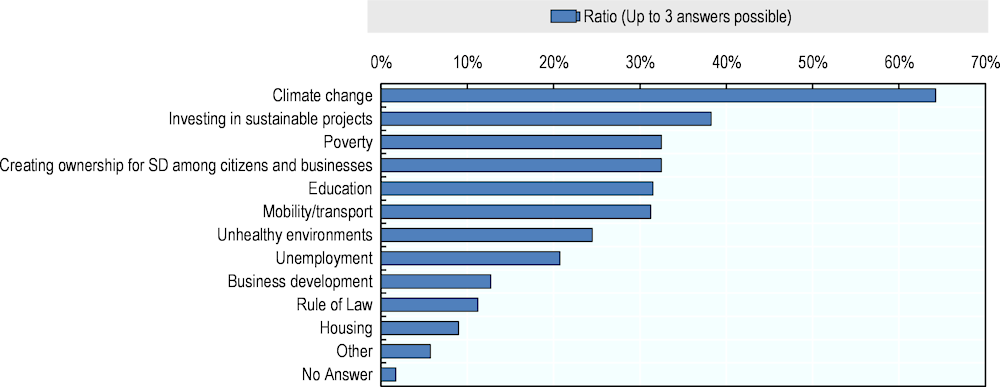

Climate change emerged as the priority the EU should focus on, selected by almost two‑thirds of respondents (who could select up to three answers). Investing in sustainable projects, poverty, creating ownership for sustainable development, education and mobility also scored high in this question (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Priorities the EU should focus on when addressing the SDGs according to local and regional stakeholders

Source: OECD/CoR (2019), Survey Results Note - The Key Contribution of Regions and Cities to Sustainable Development, https://cor.europa.eu/en/events/Documents/ECON/CoR-OECD-SDGs-Survey-Results-Note.pdf.

How cities and regions fit in the global UN process

United Nations member states review the progress achieved on the implementation of the SDGs through the preparation of Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs). Respondents were asked whether their organisation has contributed to their national government’s VNR and 21% of respondents stated that they have, either upon invitation by the national government or upon their own initiative. The share of respondents answering yes to this question is much higher among respondents representing regions (38%) and intermediary bodies (29%) than for respondents as a whole, and much lower for small municipalities (11%).

It is worth noting that the overall figure for involvement in the VNRs is significantly lower than the share of respondents that are implementing the SDGs (59%). This suggests that many of the subnational governments actively “localising” the SDGs are not involved in SDGs reporting at the national level, at least in the framework of the VNRs. The annual survey by United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) and the Global Taskforce of Cities and Local Governments (GTF) highlights that only 18 out of 47 countries reviewed (38%) formally engaged local and regional governments in the preparation of their VNRs in 2019.

As a parallel process, a handful of cities and regions are preparing Voluntary Local Reviews to assess their progress on the SDGs: this is the case of Buenos Aires in Argentina, Helsinki in Finland, Kitakyushu, Toyama and Shimokawa in Japan, Cascais in Portugal, Bristol in the United Kingdom and New York City and Los Angeles in the United States.

Mainstreaming SDGs in the design and implementation of local and regional development visions, strategies and policies

Cities and regions are increasingly using the SDGs to design, shape and implement their development strategies, policies and plans. The SDGs represent a comprehensive framework to drive integrated policies, mitigate fragmentation and silos, promote synergies and policy complementarities, and manage trade-offs across policy sectors. The SDGs are also a powerful tool and vehicle to engage all actors in the policymaking process, both within local and regional administrations and across non-governmental territorial stakeholders. They also provide a framework for local and regional leaders to better communicate and engage with citizens, and to enhance accountability through more ambitious policies and better monitoring of terms of sustainable development outcomes.

Overall, cities and regions use the SDGs to rethink local and development strategies in three main ways depending on their policy cycle, leadership, resources and goals:

Some use the SDG framework as a “checklist” or “health check” to assess the extent to which their programmes cover the span of sustainable development outcomes, to identify gaps to fill or areas where policies need to be upscaled.

Some revise and adapt existing strategies and plans against the SDGs to enhance more holistic, comprehensive, cross-sectoral and integrated actions that can drive sustainable development.

Others develop new plans and strategies from scratch, based on SDGs as a guiding framework as a means to build greater consensus and a shared vision for the future.

Assessing cities’ and regions’ programmes against the SDGs

Some cities and regions use the SDG framework as a “checklist” or “health check” to assess the extent to which their programmes cover the span of sustainable development outcomes, to identify gaps to fill or areas where policies need to be upscaled. For example, the city of Moscow (Russian Federationn Federation) has mapped all relevant initiatives and responsible departments for each SDG (Table 1.2). The core objective is to identify strong areas in terms of local action and others where more focus should be placed in the short, medium and long term. A next foreseen step is to use SDGs as an engine and opportunity to further improve policy outcomes in the city with three main strategies for the coming decade:

The 2010-35 Master Plan aims to respond to the most complex challenge for the city of Moscow, which is to promote a “balanced urban development”. The latter relates to promoting an integrated approach to urban planning, which should seek a balance between access to green areas, efficient transportation and quality housing. The key objective is to make Moscow a liveable city for everyone. Local departments within the city administration seem to be co‑ordinating well when it relates to specific programmes, such as for the urban regeneration programme, Moscow electronic school or the Magistral Route Network. Moscow’s metropolitan area (delineated using an economic-boundaries approach) encompasses around 20 million inhabitants, which requires co‑ordination across municipalities to pool resources and capacities at the right scale for housing and transport amongst others. The SDGs could be used to think beyond administrative boundaries (i.e. those of the city of Moscow) to also enhance a metropolitan approach with neighbouring municipalities.

The Investment Strategy 2025 has the long-term objective to create a favourable investment climate in the city of Moscow. The Investment Strategy is the main guideline document for investment policy in Moscow. There is room for the local government to connect with umbrella organisations, such as chambers of industry and commerce, and to actively engage local businesses in mainstreaming sustainability as a standard for their core business (e.g. sustainable supply chains, renewable energy). The strategy, therefore, provides a key tool to enhance private-sector collaboration in achieving the SDGs and for the public sector to encourage innovative “SDGs Solutions” by de-risking private investments, for example, through special economic zones and techno parks, or introducing awards for sustainability solutions.

The Smart City 2030 strategy of the city of Moscow contains six main directions aligned to the SDGs, namely human and social capital, urban environment, urban economy, digital government, security and ecology, and digital mobility. The core idea is to provide digital solutions that help advance urban sustainable development, in particular to boost local living standards and to ensure more cost-effective management and service-provision processes. For instance, the use of advanced technologies can help to measure some SDGs indicators at a granular level (e.g. use of mobile operators to define Agglomeration of Moscow or technology to measure the quality of air and water). Similarly, the digitalisation of services related to health, education or environmental participation can help to achieve some SDGs.

Table 1.2. Mapping of SDG-related projects and responsible authorities in Moscow, Russian Federation

|

SDG |

Projects and initiatives of the city |

Executive agency |

|---|---|---|

|

SDG 1 |

Socioeconomic Development of the city of Moscow |

Department of Economic Policy and Development of Moscow |

|

SDG 2 |

Eradication of Food Insecurity in the city of Moscow |

Department of Trade and Services in Moscow |

|

SDG 3 |

The Development of Preventative Measures in Moscow Medicine Healthy Moscow Moscow Longevity |

Moscow Healthcare Department |

|

SDG 4 |

Equal Access to the Education System in the city of Moscow |

Department of Education and Science of Moscow |

|

SDG 5 |

The Availability of Pre-school Education in the city of Moscow The Elimination of Gender Inequality and Access to Vocational Training for Vulnerable Populations, Including People with Disabilities The Integration of Different Levels of Education to Achieve High Educational Results Champions’ Circles About the School Day in the Technopark |

|

|

SDG 6 |

The Rational Use of Resources and Maintaining the Purity of Water Bodies Environmental Education Activities The Formation of a Sustainable System for the Development of Housing and Communal Services |

Department of Housing and Communal Services of the city of Moscow Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection of Moscow |

|

SDG 7 |

Electric Buses and Charging Stations for Them The Development of Infrastructure for Electric Transport in the city of Moscow The Formation of Transport Hubs in the city of Moscow |

Department of Transport and Development of Road Transport Infrastructure of Moscow |

|

SDG 8 and 9 |

The Innovation Cluster in the city of Moscow The INVESTMOSCOW.RU Portal The Session of Moscow’s Manufacturers Moscow Technology Parks The Innovation Cluster in the city of Moscow The Investment Policy in the city of Moscow |

Department of Entrepreneurship and Innovative Development of Moscow Moscow Department for Economic Policy Development |

|

SDG 10 |

Issues of Urban (Social) Inequality |

Moscow Department of Labor and Social Protection |

|

SDG 11 |

Targeted Investment Program Moscow Urban Renovation Program |

Moscow Urban Planning Policy Department Department of Transport and Development of Road and Transport Infrastructure of Moscow |

|

SDG 12 |

Tourism Development in the city of Moscow Environmental Education Events Sustainable Housing and Communal Service |

Moscow Committee for Tourism Department of Housing and Communal Services of the City of Moscow Moscow Department for Environmental Management and Protection |

|

SDG 13 |

Environmental Education Events Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change |

Moscow Department for Environmental Management and Protection |

|

SDG 14 |

- |

|

|

SDG 15 |

Biological Diversity Conservation Environmental Education Events Monitoring System for the State of Soil, Air and Water Bodies |

Moscow Department for Environmental Management and Protection |

|

SDG 16 |

Preventing Emergencies in the city of Moscow |

Department of Civil Defense, Emergency Situations and Fire Safety of Moscow Department of Regional Security and Anti-corruption Activities of Moscow |

|

SDG 17 |

Governmental Services Portal Mos.ru |

Department of Information Technology of Moscow |

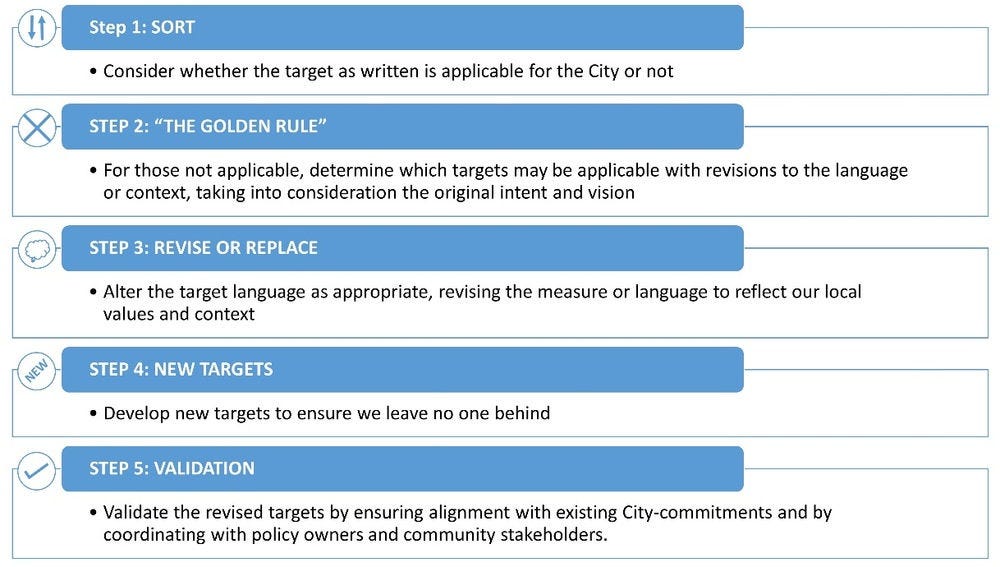

Adapting local and regional development strategies and plans to the SDGs

Some cities or regions revisit or adapt existing strategies and plans against the SDGs to enhance more holistic, comprehensive, cross-sectoral and integrated actions that can drive sustainable development. For example, in Belgium, regional governments have important competencies for regional development. In this sense, sustainable development strategies have been in place since 2006 in the region of Flanders and updated every five years. A decree from 2008 framed sustainable development as an inclusive, participative and co‑ordinated process. The second Flemish Strategy for Sustainable Development (2011) placed a strong emphasis on innovation and introduced a transition approach to achieving a long-term vision for Flanders.

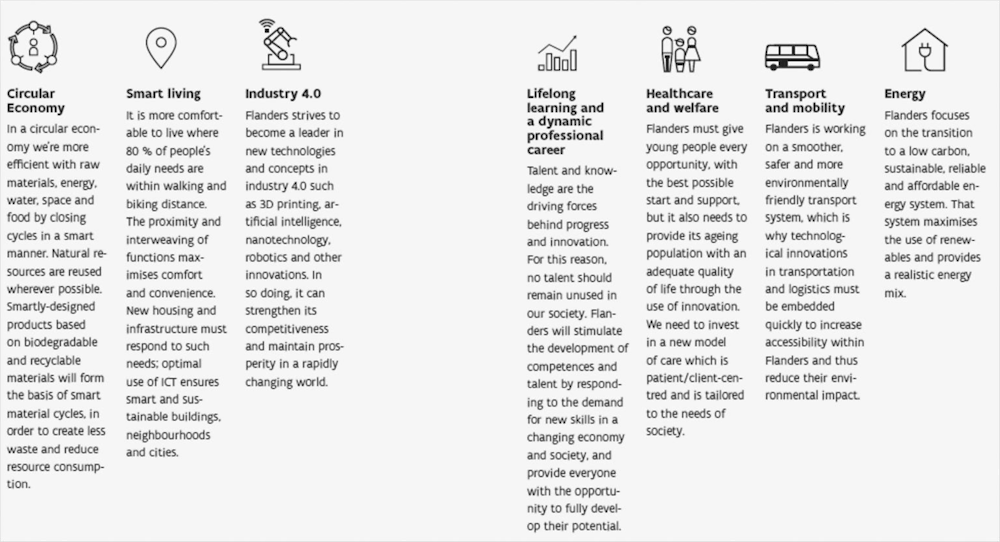

Vision 2050 is the main strategic framework of the Flemish administration with seven priority transitions towards which the region strives (Figure 1.9). To achieve this vision, a new governance model was put in place based on transition management principles such as system innovation, taking a long-term perspective, involving stakeholders through partnerships, engaging in co-creation and learning from experiments. As a next step, Flanders has translated the 2030 Agenda to place-based needs and realities within the “Focus 2030: Flanders’ Goals for 2030” (Flanders, 2019). This strategic document is guiding the implementation of the SDGs by the Flemish government by identifying 50 goals relevant to Flanders to achieve the 2030 Agenda. While not providing a one-to-one fit with the SDGs, the goals in Focus 2030 are mapped to the SDG framework. In addition, objectives related to sustainable development have been updated or redefined to better fit with the SDGs framework. The SDGs are seen as an indivisible whole with equal importance, as prescribed by the 2030 Agenda. Both Vision 2050 and Focus 2030 are umbrella strategies bringing together other plans, concepts and policies.

Figure 1.9. Key priorities of Vision 2050 in Flanders, Belgium

Source: Flanders (2016), Vision 2050, https://www.vlaanderen.be/en/publications/detail/vision-2050-a-long-term-strategy-for-flanders.

Another example is the province of Córdoba, Argentina, which is using the 2030 Agenda for improving the effectiveness and impact of its governmental actions. The Memoria de Gestion Gubernamental (Province of Córdoba, 2017; 2018) aligned the three axes of governmental action to the SDGs (Figure 1.10) and paved the way for localised SDGs indicators. The provincial government considers sustainability as a key principle guiding the actions of the government, which aim to build a “sustainable state” enabling all the inhabitants of the province to enjoy a better quality of life.

The provincial government policy agenda has a strong focus on social inclusion and well‑being. Because of Argentina’s federal structure, Córdoba province is responsible for many of the policies that have a direct impact on people’s lives such as education, housing, health, access to services or the environment. In view of the volume of resources devoted to fulfilling its well-being responsibilities and the growing demand for information, the provincial government has developed a framework of well-being indicators. The 2030 Agenda represents an opportunity to continue and expand the work on well-being and related indicators as well as to drive the social inclusion agenda in the province. In particular, SDGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 10 relating to poverty, food security, education, health, gender and inequalities have received primary attention. At the same time, to make the most of the interconnected and holistic framework of the 2030 Agenda, the province has developed a matrix to identify and measure the synergies and the trade‑offs among those SDGs driving social inclusion and the other SDGs.

Figure 1.10. Three axes of governmental action in the province of Córdoba, Argentina

Source: Province of Córdoba (2017), Memoria de Gestion Gubernamental (2017), https://datosgestionabierta.cba.gov.ar/dataset/memoria-de-gestion-gubernamental-2017.

The state of Paraná, Brazil, is making important efforts to mainstream the SDGs in its budgetary planning. Paraná is aligning its multiannual plan (PPA) for 2020-23 and other tools for planning and budgeting with the SDGs. The Audit Court of the state of Paraná, Brazil, as a partner supporting the Social and Economic Development Council of Paraná (Conselho Estadual de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social, CEDES), is leading this work by analysing the 2016-19 PPA and the 2017 Annual Budget Law (LOA 2017) and extracting lessons for the development of the PPA 2020-23. In particular, the court has developed a model to: i) examine the link between ongoing public policies and the SDGs’ targets; ii) evaluate budget expenditures related to the implementation of SDGs; iii) generate evidence to improve decision-making processes related to the SDGs; and iv) analyse the official indicators related to the budget-planning instruments (LOA and PPA). The work done by the Audit Court revealed the preponderance of process indicators over outcome indicators (Figure 1.11). From a scan of 202 initiatives, the Audit Court has concluded that only six were not linked to the SDGs and that only 21 contribute indirectly. The next step is to ensure that policies designed in the framework of the Multiannual Plan (PPA) 2020-23 are aligned with the SDGs. There is also an ambition to trickle down this methodology to the municipality level and follow up on the recommendations stemming from the analysis.

Figure 1.11. Audit Court initiatives to mainstream the SDGs into the budgetary planning process in Paraná, Brazil

In parallel, Paraná is also strengthening its financial support to municipalities to help them advance the implementation of the SDGs. For instance, cities can access specific funding for institutional strengthening programmes and investments in urban infrastructure. The state is also working to identify local, national and international partners that can expand funding base to support municipalities in their localisation effort.

Developing new local and regional development plans and strategies through the SDGs

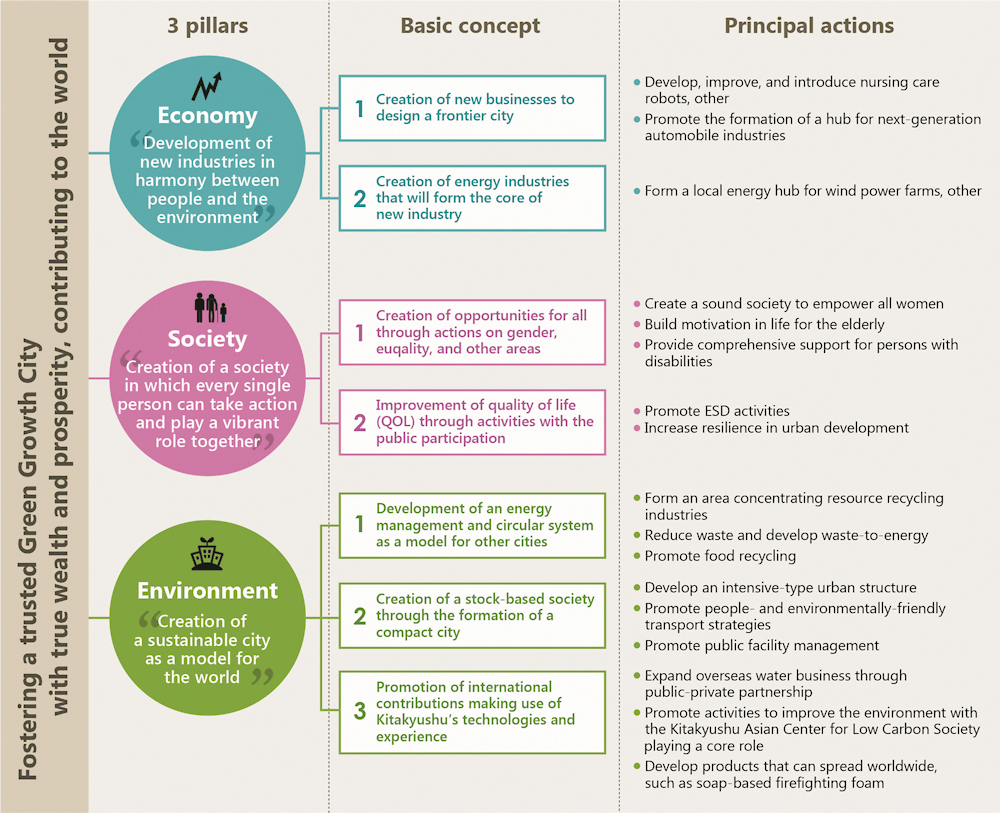

Some cities and regions develop new plans and strategies from scratch, based on the SDGs as a guiding framework, as a means to build greater consensus and a shared vision for the future. For example, the city of Kitakyushu is incorporating the SDGs into its various development plans, including establishing indicators relevant for the SDGs in their monitoring. Under the Kitakyushu City Plan for the SDGs Future City (City of Kitakyushu, 2018), 22 indicators were established in collaboration with the national government.

Kitakyushu’s primary motivation to formulate this plan has been to turn the experience of overcoming high levels of pollution in the 1960s into a strength. This was achieved by applying the concept of green growth and developing an economy based on recycling and green industries, and sustainable and renewable energy. Collaboration between the local government, the industries and civil society – in particular women’s associations – was key to overcoming the issue of pollution in the 1970s. These citizens’ initiatives constitute good practices promoted by the city of Kitakyushu to face current challenges, like the need to engage the elderly population in social activities and secure appealing jobs for young people to prevent further population decline.

Building on Kitakyushu’s long-term commitment to sustainability, the vision “Fostering a trusted Green Growth City with true wealth and prosperity, contributing to the world”, was developed within the SDGs framework of the Future City programme launched by the Cabinet Office of the Japanese Government. The programme focuses on three pillars – economy, society and environment – and 17 specific measures to implement it (Figure 1.12). Kitakyushu has identified 8 SDGs that represent the main strengths of the city, mainly linked to the environmental dimension (SDGs 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 and 17), and has formulated its SDGs Future Plan.

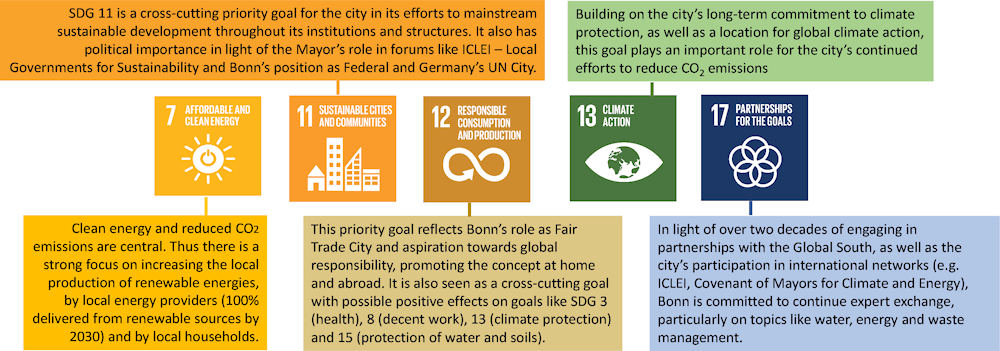

Another example can be found in the city of Bonn, Germany, with a long-term commitment to sustainable development. This can be seen – inter alia – through its engagement in Local Agenda 21 since 1997, certification as Fair Trade Town since 2010, the establishment of a co‑ordination unit on climate and as a signatory of the resolution by municipalities to support the 2030 Agenda in February 2016. Bonn’s first sustainability strategy, developed in the context of the 2030 Agenda, was officially adopted by the city council in February 2019.

The city of Bonn has gone through a comprehensive process to localise the SDGs through its new sustainability strategy. The 2030 Agenda is seen as an opportunity to bring together the city’s global responsibility agenda with actions promoting sustainable development within the city itself. As such, the sustainability strategy was designed to respond to key challenges and strengths of the city, for which some SDGs were identified as particularly relevant (Figure 1.13). For example, clean air and reduced CO2 emissions are high on the political agenda in Bonn. As several other German cities, Bonn is struggling to reduce NO2 levels to comply with European norms. This is particularly challenging in light of Bonn’s growing population and persistently high rates of individual motorised vehicle traffic in the city, due to – among other things – high commuting flows. Mobility is thus a hot topic in the public debate. Increasing rental and housing prices, with implications on housing affordability, and keeping green spaces intact (50% of the city’s surface are protected green areas) are other challenges dealt with by the city.

Figure 1.12. Vision and action for the SDGs Future City Plan in Kitakyushu, Japan

Source: City of Kitakyushu and Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (2018), Kitakyushu City the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018 - Fostering a Trusted Green Growth City with True Wealth and Prosperity, Contributing to the World, https://iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/policyreport/en/6569/Kitakyushu_SDGreport_EN_201810.pdf.

Bonn’s sustainability strategy is developed with the support of Service Agency Communities in One World of Engagement Global on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). In this process, Bonn is 1 of 15 pilot cities, municipalities and administrative districts in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) that participated in the pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipality in NRW”. The objective is to develop a common strategy that integrates both the local and global perspectives on sustainable development. The Service Agency is currently implementing this same project in eight more states (Länder) in Germany.

Figure 1.13. Key SDGs for the city of Bonn, Germany

Source: OECD elaboration based on the OECD SDGs Questionnaire completed by the local team of the city of Bonn (Germany).

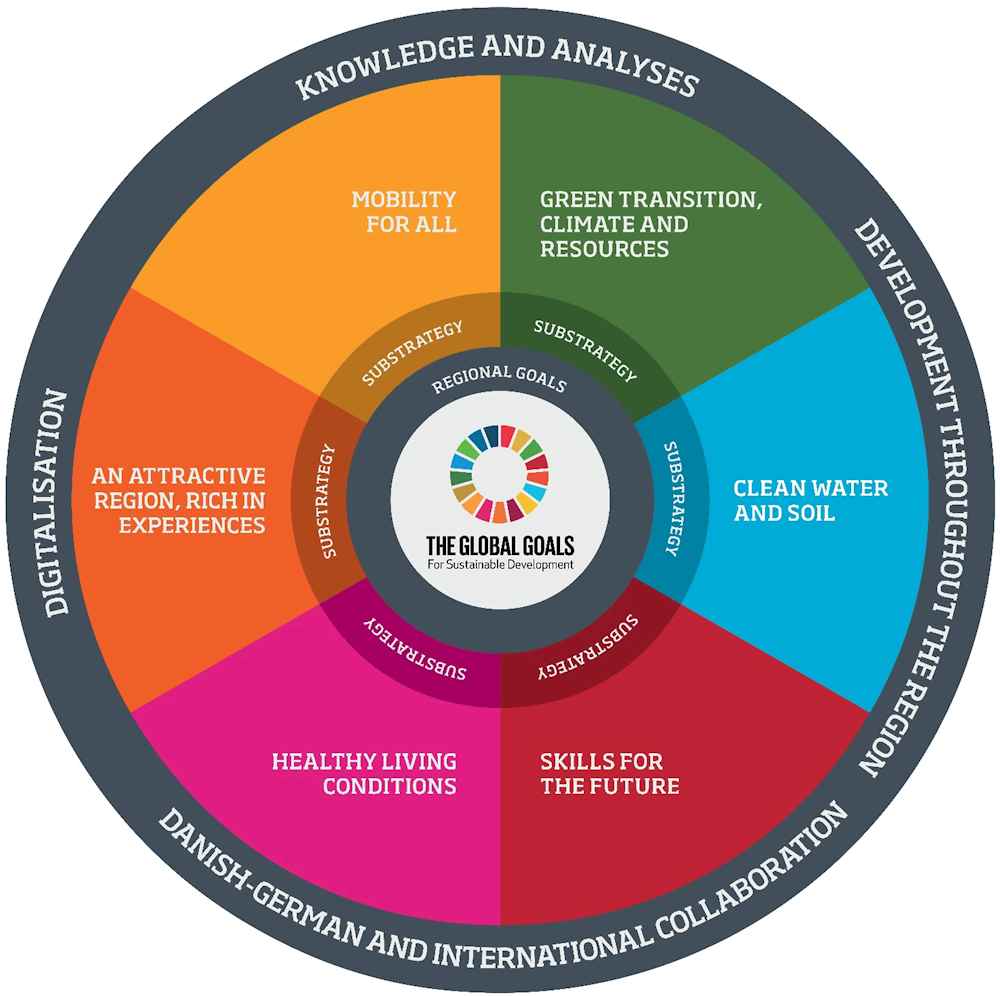

Denmark is another country where subnational governments have used the SDGs as a driver to implement better policies. For instance, the concepts of quality of life, well-being and sustainability have long been part of the regional narrative in Southern Denmark. The region’s particular areas of strengths include renewable energies and energy efficiency, with over 40% of employment in the Danish offshore wind energy sector located in Southern Denmark. Moreover, competencies in health and welfare innovation, including automation, intelligent aids, information technology (IT) and telemedicine add to the region’s strategic advantages, as well as the fact that Southern Denmark is the largest Danish tourism region. Although the SDGs are not formally included in the current Regional Development and Growth Strategy (2016-19) “The Good Life” (Det Gode Liv), the six priority areas and the policy themes covered are all directly or indirectly linked to the SDGs framework.

Moving forward, the region of Southern Denmark has been incorporating the SDGs in the new regional development strategy (2020-23). The overall concept of well-being and quality of life, the six strategy tracks, the specific regional goals and as well as the action of the region are linked to specific SDGs and are designed to contribute to their achievement. In particular, the region has decided to focus on 11 goals that are mostly relevant for its work: SDG 3 on health, SDG 4 on education, SDG 5 on gender, SDG 6 on water, SDG 7 on clean energy, SDG 9 on industry and infrastructure, SDG 10 on inequalities, SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities, SDG 12 on sustainable consumption, SDG 13 on climate and SDG 14 on life below water.

The regional government has developed a participatory process to engage local stakeholders in the new regional development strategy based on the SDGs (Figure 1.14). This includes: i) a public consultation process with local municipalities, education institutions, museums and other interested parties between 9 October 2019 and 17 January 2020; ii) a public “consultation conference” on 27 November 2019 in Vejle; iii) ad hoc consultations with local municipalities; iv) a dedicated consultation process with the partners on the German side of the Danish-German border; and v) a “kick-off conference” in May 2020.

Figure 1.14. Linking the regional development strategy 2020-23 and SDGs in Southern Denmark, Denmark