Annex A provides some basic information on the role and capacity of the banking sector in Georgia to support the economic development of the country. It also looks at the main trends in the banking sector, particularly since the last financial crisis. The annex introduces major reforms that the government of Georgia could consider. These reforms would aim to create an effective and competitive banking system that can also offer higher volumes of green lending.

Access to Green Finance for SMEs in Georgia

Annex A. Georgia’s banking sector

Market structure and concentration

There is a high degree of concentration in the Georgian banking sector. The top three banks account for 79% of assets with the top two, TBC Bank and Bank of Georgia (BoG), accounting for 74% of assets.

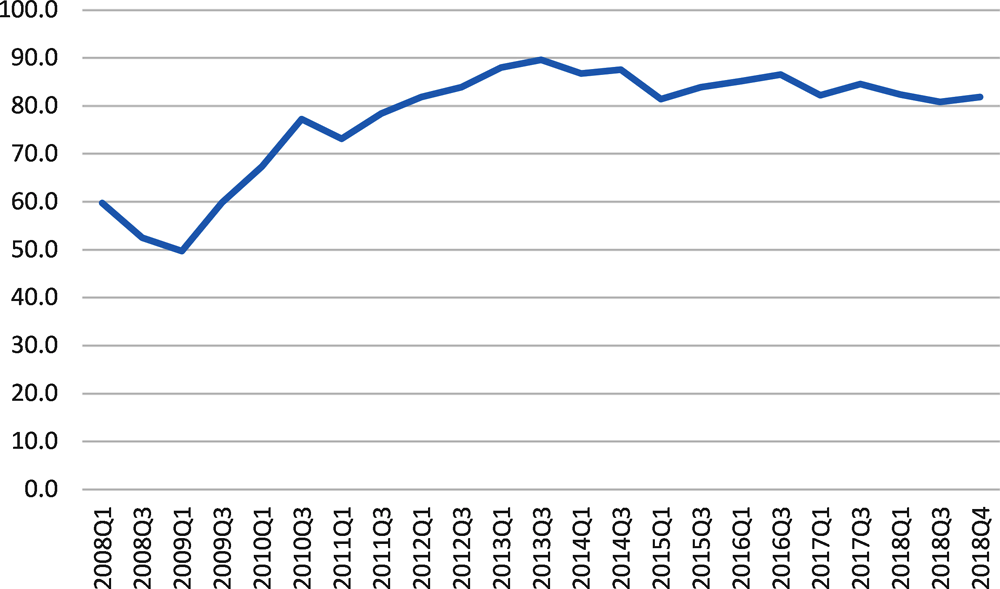

The Georgian financial sector is almost entirely dependent on banks (90%+). Capital markets remain underdeveloped, potentially due to structural issues. The equity market is highly illiquid. Sovereign bonds are liquid, but private bond issuance is limited.

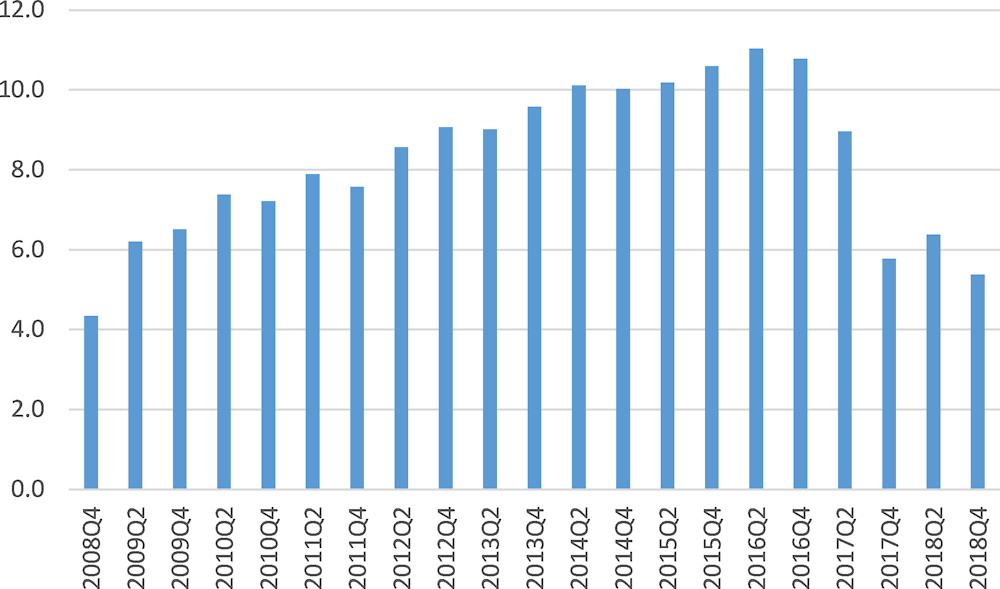

Figure A A.1. Non-banking financial assets as a share of total assets, 2008-18

In 2017, the International Finance Corporation supported the BoG in its first local currency Eurobond issuance. It invested about USD 45 million helping to attract about USD 250 million from about 20 international investors. This three-year bond was the first in the past decade from a country in the European Union’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) region other than the Russian Federation. It supported local-currency lending and de-dollarisation efforts. The issuance allowed the bank to boost long-term local-currency financing to more retail borrowers, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This aims to help them avoid risks related to borrowing in foreign currency (Agenda.GE, 2017[2]).

However, policy makers need to take certain precautions. For example, they must ensure open entry to the market and competition. They must also ensure that sufficiently strong safeguards are in place to prevent collusion or market dominance. Finally, they must ensure that the two institutions, Bank of Georgia (BoG) and TBC Bank, do not become “too big to fail”.

Georgia has a relatively weak legislative framework for corporate governance. The new Corporate Governance Code, recently adopted by the National Bank of Georgia, is expected to address some of the governance challenges facing Georgian banks. Given that TBC Bank and BoG are both listed on the London Stock Exchange through ultimate parent companies, they have a much higher level of governance and transparency than many other banks. They can also attract a much wider investor base. However, this comes at the expense of liquidity in the Georgian securities market as key securities are not listed domestically.

Over 2015‑17, there was some consolidation in the Georgian banking market. The number of active banks fell from 21 to 16. Six small banks were no longer active or acquired by TBC Bank/BoG. One microfinance organisation received a banking licence.

The consolidation has been driven by two factors. The National Bank of Georgia (NBG) has introduced stricter regulation and supervision. For example, in 2018 as a result of transitioning to the Basel III framework the NBG introduced increased minimum capital requirements. Market competition (economies of scale and efficiency) is another factor influencing consolidation.

Table A A.1. Consolidation in the Georgian banking market

|

Timing |

Consolidation event |

|---|---|

|

January 2015 |

Merger of TBC and Bank Constanta |

|

May 2015 |

Merger of BoG and Privatbank |

|

2016 |

Progress Bank cancelled its banking licence to become a non-bank institution |

|

September 2016 |

NBG revoked licence of Caucasus Development Bank; bankruptcy of mother company in Azerbaijan |

|

November 2016 |

Closure of Capital Bank due to breach of NBG regulations (money laundering) |

|

March 2017 |

Banking licence for Credo (microfinance) |

|

May 2017 |

Merger of TBC and Bank Republic |

Source: (GET Georgia, 2018[3]).

There is also a high level of foreign capital (15 of 16 banks), with 80% of assets under foreign ownership (through portfolio rather than strategic investors). Georgia is unusual among countries in the region in that it has no state-owned banks. International experience suggests that even highly concentrated banking systems can be efficient and provide access to credit for SMEs.

Trends in the banking sector

There has been strong progress in developing financial intermediation.

Sector performance

In terms of capital, overall Georgian banks are well capitalised. All banks comfortably meet the minimum capital adequacy ratio of 10.5%. Since transition to Basel III in 2018, requirements have changed and they are now different for each bank. The National Bank uses demanding risk weights for foreign currency loans. BoG and TBC Bank have additional buffers. These currency buffers should be maintained given external risks and other vulnerabilities.

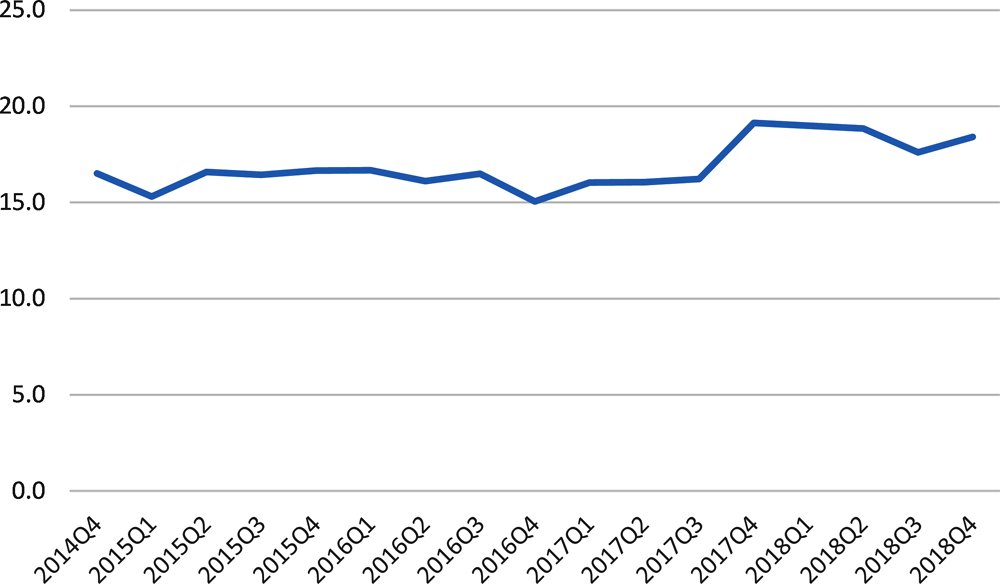

Figure A A.2. Regulatory capital adequacy ratio for Georgian banks (Basel III), percentage, 2014-18

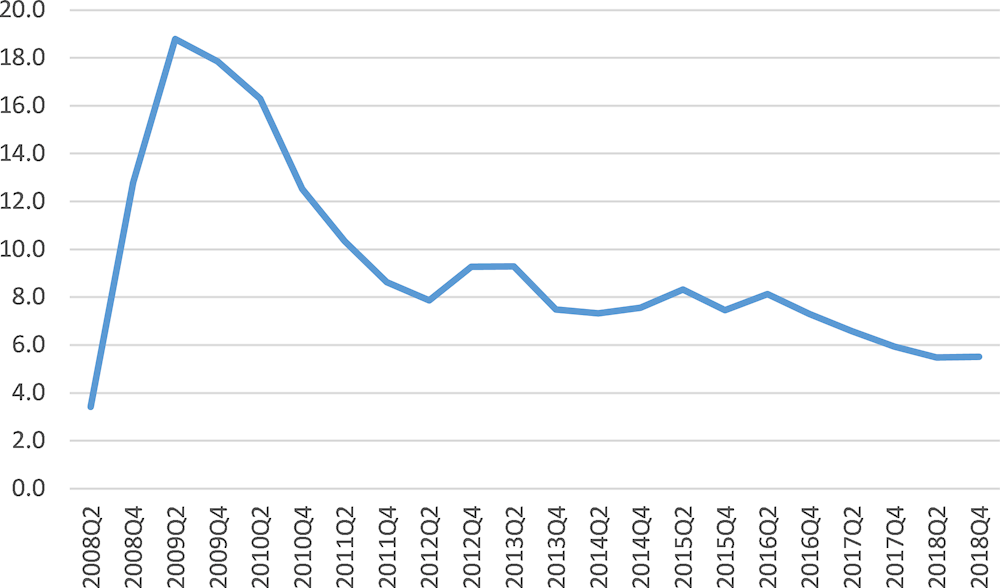

In terms of asset quality, there has been a long-term decline in the levels of non-performing loans (NPLs) (based on the NBG definition). NPLs declined from 9.5% in early 2013 to 5.5% by the end of 2018. Banks generally employ strong provisioning policies, with active efforts to restructure companies in debt, supported by a new bankruptcy law. There was no major increase in NPLs following depreciation of the Georgian Lari (GEL) in 2015. Due to the rapid growth in retail credit and foreign exchange borrowing, NPLs may increase. However, the National Bank employs strong oversight.

Figure A A.3. Non-performing loans for Georgian banks, share, 2008-18

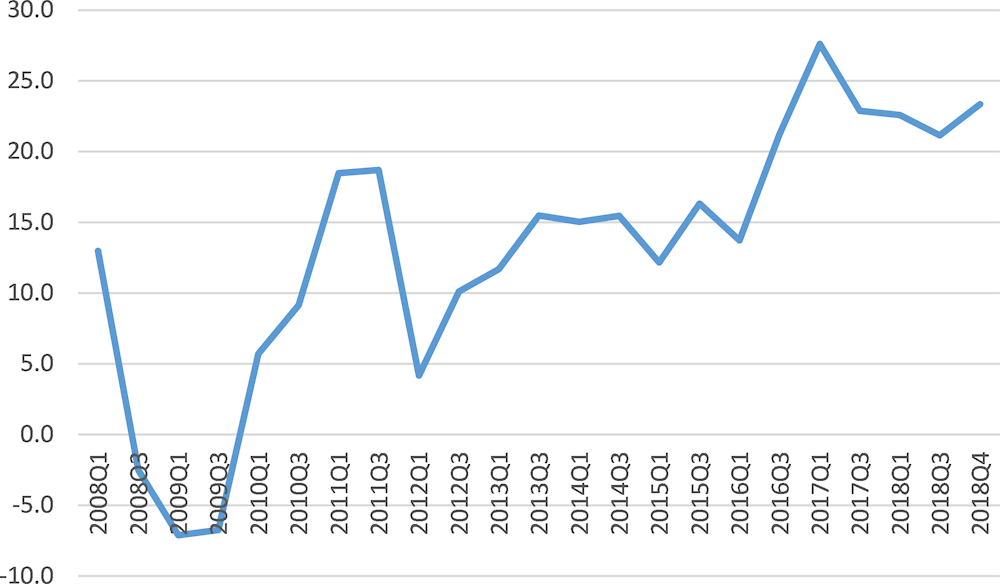

Profitability across the sector turned negative during the financial crisis, but soon recovered. Return on equity (RoE) in the banking sector is high in Georgia (23.3% in 2018), and much higher than in other banks in the region. A high RoE supports stability in the banking sector, and can be partly explained by good banking efficiency and low impairment charges (e.g. NPLs and default rates).

Figure A A.4. Return on equity of Georgian Banks, 2008-18, share

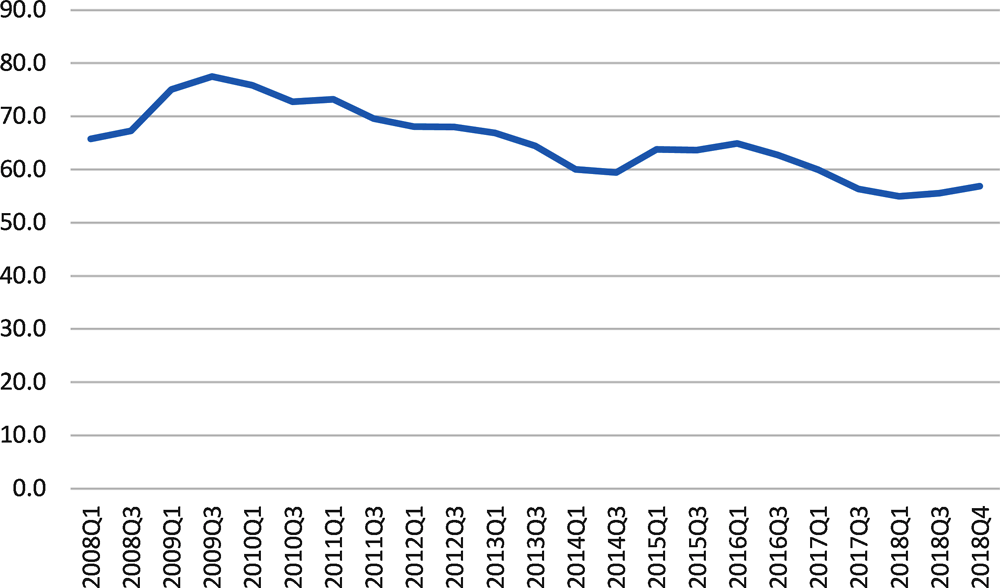

Georgia’s banks enjoy stable funding with increasing deposits since 2014 despite regional tensions and depreciation of the Georgian Lari. There is limited wholesale funding (partly from IFIs). There is a high share of liquid assets, with deposit-to-loan ratios of about 100% at all key banks. There is a high degree of trust among depositors in the banks and the supervisor, and the absence of a deposit insurance scheme has not to date been a problem. Banks generally use conservative funding models. Approximately 38% of deposits are in local currency, with 62% in foreign currency.

Figure A A.5. Georgian banks customer deposits to overall loans, share, 2008-18

Dollarisation can create risks for banking solvency and financial stability. It can also constrain macro policy (creating a fear of floating currency). On the one hand, lack of a credible monetary regime and high variability in foreign exchange and inflation are key drivers of dollarisation. On the other, inflation targeting and credibility can reduce it. There was a significant decline in loan dollarisation in 2017, helped by the prohibition of foreign currency loans under GEL 100 000. Deposit dollarisation has also been reduced. However, foreign currency is still regarded as a stronger store of value.

Figure A A.6. Share of foreign currency-denominated loans issued by Georgian banks, 2008-18

Ongoing reform

Dollarisation remains the key vulnerability of Georgia’s financial system. The preconditions for addressing this are in place. Higher capital requirements for loans denominated in foreign currencies will act as a buffer and reduce risks. The introduction of inflation-indexed bonds would also support this, as well as the development of local-currency long-term debt instruments. There have also been concerns about the close relationship between the banking sector and other areas of the economy. Commercial banking groups have historically had interests across a range of other sectors, including construction, healthcare, tourism, education and winemaking. There have been concerns that banks provide preferable treatment to connected companies. This distorts the market and reduces availability of credit to other businesses (Khundadze, 2017[4]). The National Bank of Georgia and the government introduced regulations to address cross ownership in 2014. However, concerns remain, and the situation requires ongoing monitoring.

Georgia has rather underdeveloped bond and equity markets. Larger companies lack long-dated local-currency debt instruments and risk-oriented capital. Central Europe has demonstrated that both markets can become liquid, even in a small economy. The emergence of Georgia’s pension funds and the growing interest of foreign institutional investors would be supportive. Regulatory priorities are to increase concentration of liquidity, enhance transparency at issuance and listing of companies which will help contain self-dealing and/or insider dealing.

Under its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the European Union (EU), Georgia has committed to adopt the entire EU financial framework as it evolves. This is in the country’s own interest, as it imports a credible legal regime that is well-recognised internationally. But EU rules need to be adapted to the local context. The deposit insurance fund is a good illustration of reflecting much smaller local thresholds. As in all emerging markets, a framework for orderly bank resolution is essential. However, mobilising a potential “bail-in” will depend on establishing credible domestic supervision. Many capital market instruments are not yet developed. Present EU rules could overburden the supervisor unnecessarily and discourage further market development.

References

[2] Agenda.GE (2017), “International finance corporation invests in Bank of Georgia landmark eurobond”, G.E. Agenda, 2 June, http://agenda.ge/en/news/2017/1099.

[3] GET Georgia (2018), “Banking sector monitoring Georgia 2018”, Policy Study Series, No. PS/01, German Economic Team Georgia/Berlin Economics, Tibilisi/Berlin, https://www.get-georgia.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/PS_01_2018_en.pdf.

[4] Khundadze, T. (2017), “The two faces of Georgia’s banking sector”, OC Media, 31 March, http://oc-media.org/the-two-faces-of-georgias-banking-sector/.

[1] NBG (2019), Financial Soundness Indicators, National Bank of Georgia, webpage (accessed 23 October 2019), https://www.nbg.gov.ge/index.php?m=304.