This chapter compares the share of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) in Australia with that in other OECD countries and describes their characteristics. It explains why understanding NEET trends and characteristics among older teens and young people in their early twenties is important for designing policies and programmes intervening preventatively among adolescents in their mid-teens, which is the focus of the report. Apart from 2020, the NEET rate in Australia has generally been below the OECD average in the recent past. As in many other countries, young people with lower educational attainments or health issues and those with a First Nations peoples’ background are over-represented among the NEET population.

Adolescent Education and Pre-Employment Interventions in Australia

1. The NEET population in Australia and levers for prevention

Abstract

Young people’s disengagement from employment, education or training has major costs for individuals but also for society as a whole. When young people are not in employment, education or training (NEET), they fail to acquire valuable skills, thus facing a higher likelihood of being unemployed as adults and having a lower lifetime income. They are also more likely to suffer from poorer physical and mental health and to be less socially integrated within their communities. Finally, individuals who are long-term NEET are more likely to require social assistance and to contribute fewer taxes over their lifetime.

Some young people become NEET because of transitory conditions, such as economy-wide or industry or region-specific economic downturns. A stark example is the upswing in the share of young people who are NEET across the OECD following the global financial crisis (OECD, 2016[1]) or more recently, during the economic crisis as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic (OECD, 2021[2]). In these cases, proactive measures are required to support individuals who are NEET during the downturn and to hasten their return to the labour market. However, such measures, which in Australia include the Transition to Work services and ParentsNext support, are directly targeted at young school leavers and NEET youth and thus mainly concern older teenagers and young adults (i.e. 15‑24 year‑olds), whom are outside the scope of this report. For other young people, their NEET status is the result of their lack of engagement with education, employment and training, often stemming from negative experiences or socio‑economic conditions during their childhood or teenage years. In such cases, preventive measures are needed to lower the risk of becoming NEET (OECD, 2016[1]).

In acknowledgement of the potential importance of preventive measures for reducing NEET risks among young people, the‑then Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment1 has tasked the OECD with preparing a report on good international practices in education and pre‑employment preparation interventions targeting the age group of 12‑16 year‑olds. Since much of the international comparative literature so far has focused on prevention and activation measures in older youth age groups, the report could also be of interest to actors beyond Australia.

The structure of the report is as follows: This chapter presents an overview of the prevalence and characteristics of individuals who are NEET in Australia and their specificities in comparison with other OECD countries, to ensure that the recommendations in the rest of the report are relevant in the Australian context. The following chapters explore the preventive policies and interventions already in place in Australia and presents a summary of key aspects of different interventions in three policy areas: education interventions (Chapter 2), pre‑employment interventions (Chapter 3) and interventions within vocational education and training (Chapter 4). Wherever possible, the chapters also present evidence from the existing literature on the impact of the interventions on the likelihood of entering the NEET status. Finally, Chapter 5 discusses in broad terms how a strengthened monitoring and evaluation system could support preventive policies and interventions over time.

As the report refers to various age groups among young people, the terminology used is generally as follows: “Young people” generally refers to the population of older teenagers and young adults aged 15‑29. “Adolescents” or “mid-teens” generally refers to the population of 12‑16 year‑olds; “late teens” to 15‑19 year‑olds and “early twenties” to 20‑24 year‑olds.

1.1. Recent trends in NEET rates and educational attainment

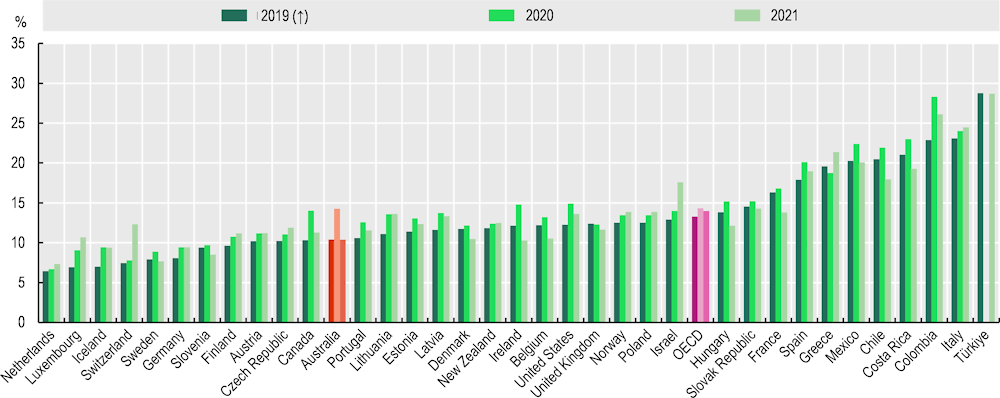

Australia’s NEET rate is generally lower than the rate observed on average for other countries in the OECD, but several countries including Nordic ones show that the rate can be brought further down. In 2021, the NEET rate in Australia stood at 10.4% among 15‑29 year‑olds, below the OECD average of 13.9% (Figure 1.1). The impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the required lockdowns was stronger in Australia than in most OECD countries. This led to a 2020 NEET rate slightly above the OECD average, but the rate quickly reverted to the pre‑pandemic situation. This trend is a reflection of developments in the overall unemployment rate during the pandemic: in Australia, the unemployment rate of 15‑64 year‑olds initially increased more than in many European countries, though to a lesser extent than for example in Canada and the United States. A contributing factor to this difference was that many other countries already had long-established and broad-ranging job retention schemes, including short-term work programmes. These short-term work programmes subsidised hours that employees did not actually work, for example because a business was closed or faced drastically reduced demand during lockdowns. By allowing employers to maintain contracts without bearing the entire financial brunt, employers were less likely to lay off workers. In contrast, prior to the pandemic, the Australian wage subsidy programme focused on supporting individuals receiving income support; and the lump-sum wage subsidy introduced during the pandemic took the role of a minimum salary (OECD, 2021[3]).

Figure 1.1. With the exception of the pandemic year 2020, the overall NEET rate in Australia was below the OECD average

Note: Sorted in ascending order (↑) by the 2019 NEET rate. The unweighted OECD average excludes Japan and Korea. The NEET rates generally refer to the yearly average, but refer to the second quarter for those countries where the statistics are taken from the Education at a Glance database (Australia, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Türkiye).

Source: Own calculations based on labour force surveys and (OECD, 2022[4]), Education at a Glance 2022 database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EAG_TRANS.

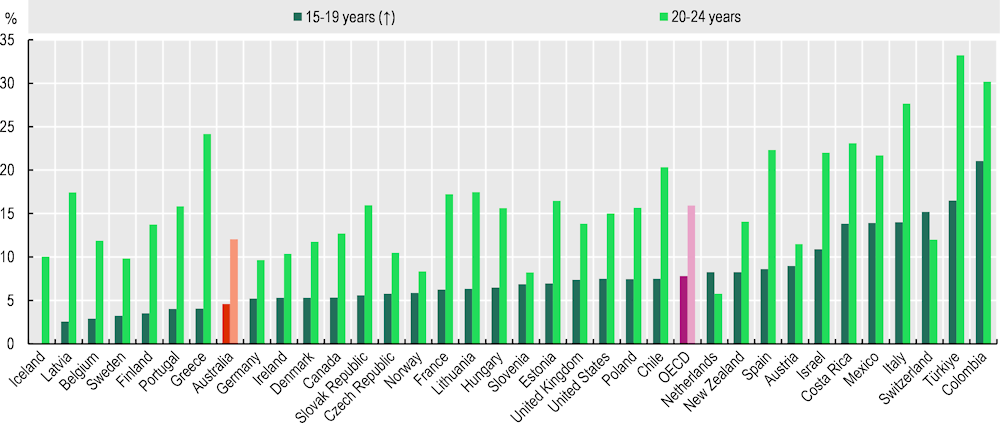

The rate of young people who are NEET among 15‑19 year‑olds is typically lower than the rate among 20‑24 year‑olds as most young people are still in secondary education. In Australia in 2021, the rates of young people who are NEET among 15‑19 and 20‑24 year‑olds stood at 4.6% and 12.1% respectively, compared with OECD averages of 8.5% and 17.1% respectively (Figure 1.2). Differences in the rates of young people who are NEET across countries among 15‑19 year‑olds reflect, to a large extent, the degree to which legal and systemic factors in countries mandate and encourage young people to stay within upper secondary and transition to post-secondary education, although some older teenagers can also transition to the labour market. For the 20‑24 age group, the rate of young people who are NEET is determined both by a system’s ability to guide young people who entered post-secondary education towards graduation and by its ability to ensure that those who graduate or otherwise leave educational programmes can establish themselves in the labour market.

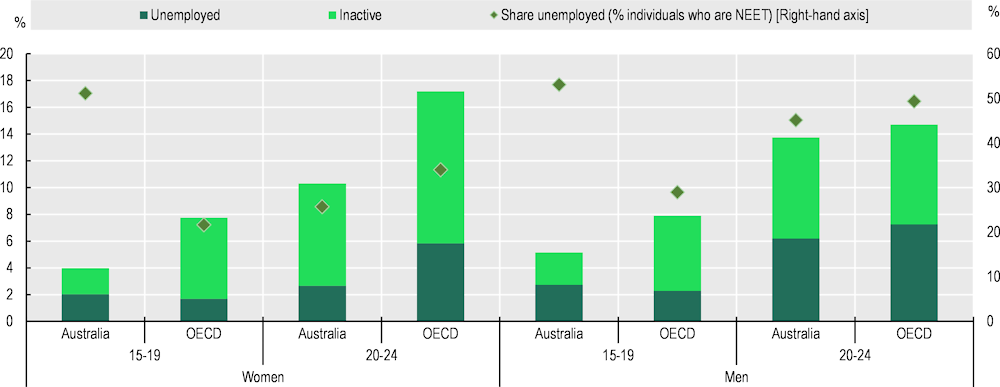

Among teenagers who are NEET, a higher proportion are unemployed (i.e. actively looking for a job) rather than inactive (i.e. not actively looking for a job) in Australia compared to the OECD average; but the opposite is true among young people in their early twenties. In 2021, 51.1% of female and 53.1% of male 15 to19‑year‑old individuals who were NEET were available and actively looking for work, compared to the respective 22.2% and 28.2% OECD averages. In contrast, the share of unemployed individuals in Australia among 20‑24 year‑olds who are NEET is lower than the OECD average with 25.7% of young women and 45.1% of young men in Australia who are NEET compared to 34.1% and 49.5%, respectively in the OECD (Figure 1.3). Depending on the circumstances, it may be easier to activate unemployed rather than inactive young people, especially those who sought out the support of the public employment service. However, prior analyses show that in many countries, a significant proportion of young jobseekers are not actually registered with the public employment service, the agency or office providing job seekers with labour market information and job brokerage as well as, depending on the country, administering unemployment benefits and active labour market programmes (OECD, 2021[5]). A certain share of inactive individuals, though by no means all, may also be completely unavailable for the labour market, be it because of illnesses or family obligations.

Figure 1.2. Both older teenagers and young adults less likely to be NEET in Australia than on average across the OECD

Note: Sorted in ascending order (↑) by the NEET rate of 15‑19 year‑olds. The unweighted OECD average excludes Japan and Korea. The NEET rates generally refer to the yearly average but refer to the second quarter for those countries where the statistics are taken from the Education at a Glance database (Australia, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Türkiye).

Source: Own calculations based on labour force surveys and (OECD, 2022[4]), Education at a Glance 2022 database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EAG_TRANS.

Figure 1.3. The share of unemployed individuals among 15‑19 year‑olds who are NEET is higher in Australia than across the OECD

Note: The unweighted OECD average excludes Japan and Korea.

Source: Own calculations based on labour force surveys and (OECD, 2022[4]), Education at a Glance 2022 database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EAG_TRANS.

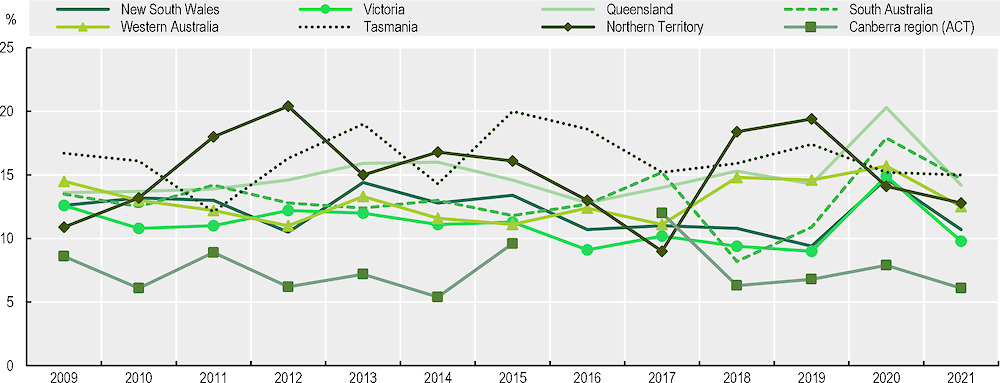

The NEET rate in Australia varies quite strongly across different States and Territories. Looking only at the population of 18‑24 year‑olds over the 2009 to 2021 period, the NEET rate in the territory with the highest rate is around three times higher than the territory with the lowest rates. For example, this occurred in 2012, 2014 and 2018‑19 (Figure 1.4). NEET rates do not always fall and rise in tandem across Australia – for example, between 2017 and 2018, the rate basically doubled in the Northern Territory while it halved in the Australian Capital Territory (Canberra). The one constant, aside from the outlier year 2017, is that the NEET rate in Canberra is generally lower than in any other state or territory.

Figure 1.4. The rate of young people who are NEET is almost consistently the lowest in Canberra

Source: OECD (2020), “Early leavers from education and NEET”, OECD Regional Education Database, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=90228.

1.2. NEET characteristics in Australia and across OECD countries

The characteristics of young people who are not in education, employment or training differ from that of the youth population overall. As this section will show, the share of young people who are NEET differ between young male and female adults; university graduates and early school leavers; First Nations peoples and others; and along a variety of other characteristics.

Teenage girls are less likely than boys to be NEET in Australia, but this difference has historically reversed in their early twenties with young women being more likely than boys to be NEET. In 2021, in the age group of 15‑19 year‑olds, the rate of young people who were NEET was lower for girls than for boys in Australia (3.9% versus 5.1%), while across the OECD they were almost identical (8.8% and 8.7%, respectively) (Figure 1.3). In 2021, for youth aged 20 to 24, in contrast, the rate of young people who were NEET was more elevated for young women than young men across OECD countries (17.3% for women and 14.7% for men), but not in Australia (10.3% and 13.7%, respectively). However, prior to 2019, the rate of 20 to 24‑year‑old women who were NEET was usually higher than that of their male peers. This difference was driven largely by a higher share of young women who were inactive. Caretaking responsibilities are an important factor in shaping the differences in the evolution of NEET prevalence among young men and women. According to OECD estimates based on the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, the NEET rate among teenagers and young people in their early and late twenties is lower among childless women than their male peers in the same age group. Moreover, on average from 2017 to 2021, less than half a percent of 15‑19 year-old girls and women who were either in education or employed had a child, while 8.5% of NEET girls and women in the same age group were mothers. These figures were in line with those estimated for the other 26 OECD countries with available data. Teenage motherhood is slightly more common among Australian- than among overseas-born women, but four times as common among First Nations peoples than other women (AIHW, 2015[6]). In the 20‑24 age group, the prevalence of motherhood among young women who are not NEET and who are NEET equals 4.3% and 30.3% in Australia, and 4.6% and 33.6% across OECD countries.

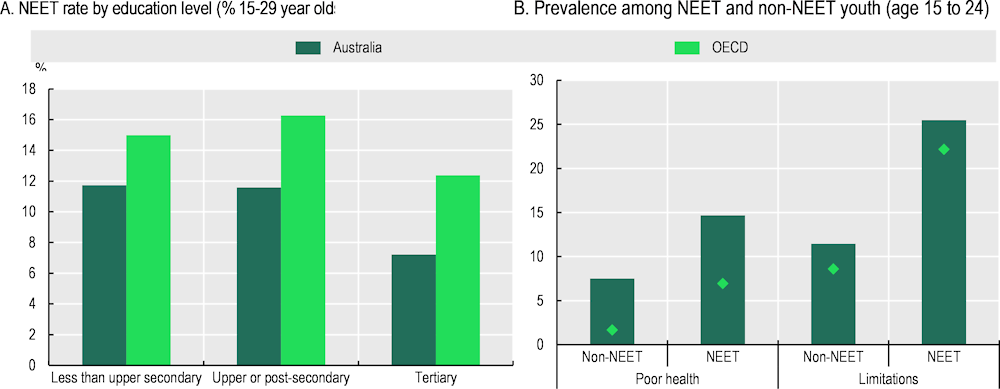

Participation in higher education is strongly associated with a lower likelihood of experiencing NEET status in Australia. In 2021, the NEET rate for 15‑29 year‑olds who graduated from university was 7.2%, compared to 11.7% for those who did not graduate from upper secondary school (Figure 1.5, Panel A). In contrast, on average across OECD countries, the university graduate NEET rate of 12.4% was much closer to the rate for those who did not complete upper secondary school (15.0%) (Department of Education, 2022[7]).

Figure 1.5. The share of university educated young people who are NEET is particularly low in Australia

Notes: Panel A: The reference year is 2021. The NEET rates generally refer to the yearly average, but refer to the second quarter for those countries where the statistics are taken from the Education at a Glance database (Australia, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Türkiye). The unweighted OECD average excludes Japan and Korea.

Panel B: The reference year is 2021 for Australia and the latest available year for the different OECD countries. Calculations based on household survey data, excluding Canada, Costa Rica, Colombia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand and Israel.

The indicator for “Limitations” refers to the share of individuals who report that their health limits their daily activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling or playing golf.

“Poor health” refers to the share of individuals who rate their general health as very bad or bad, or equivalently the two worst outcomes on a five‑point scale.

Source: National household and labour force survey data and (OECD, 2022[4]), Education at a Glance 2022, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

First Nations youth face a higher risk of experiencing NEET status. This increased risk arises because First Nations teenagers and young adults are more likely to experience factors that are associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing a NEET status such as living in remote areas, living in poverty, suffering from poor mental health, and not achieving minimum educational achievement standards. At the same time, First Nations young people may also experience sources of disadvantage associated with how others perceive their identity, such as social and cultural exclusion and discrimination, as well as the accumulation of multiple sources of disadvantage (National Indigenous Australians Agency, 2022[8]; AIHW, 2018[9]).

In 2020, the NEET rate among First Nations youth was nearly two times as elevated as among young people who did not identify as First Nations peoples. According to earlier analyses, First Nations individuals made up around 3% of the youth population, but 10% of young people who are NEET (OECD, 2016[10]). The persistence in the NEET status is very high for First Nations young people: According to analyses based on the linked Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset, two‑thirds of First Nations young people aged 15‑24 who were NEET in 2011 remained so by 2016 (Dinku, 2021[11]). The employment gap between First Nations youth and other young people widens with age; and young First Nations women are at a particular disadvantage in terms of their employment rates (Venn, 2018[12]). First Nations youth are also under-represented among tertiary students and even more so among graduates: The Australian Government Department of Education’s (2022[7]) higher education statistics shows that they make up 1.4% of all students at university in 2020, with First Nations students completing 0.8% of total awarded courses in 2020.

In many of the countries with available data, Indigenous individuals and ethnic minorities are more likely to be NEET. For example, in Canada in 2018/19, among young people living off-reserve, the rate of 15‑19 year‑old Aboriginals (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) who were NEET was 5 percentage points higher than among their non-Aboriginal peers. Among 20‑24 and 25‑29 year‑olds it was 10 percentage points higher (Brunet, 2019[13]). In the younger age group, the difference was due to lower school enrolment while in the older age group, lower employment was a main factor. In many European countries with substantial Roma populations and reliable data, the rate of Roma young people who are NEET tends to be higher than it is among the general population of young people. In Hungary, for instance, the rate of 18‑24 year‑olds from Roma communities who were NEET was 38% in both 2011 and 2016, whereas the rate among non-Roma communities for the same age group decreased from 13% to 9% percent (Scharle, 2020[14]).

In 2020, Australia was one of the few countries in which foreign-born young people were at a lower risk of being NEET than native‑born young people.2 That year, the NEET rates for overseas- and Australian-born individuals aged 15 to 29 were 8% and 12%, respectively. In contrast, across the OECD (excluding Korea, Japan and Türkiye), the corresponding average rates were 18.8% and 13.2%. Other countries in which relatively fewer foreign- than native‑born young people are NEET include Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand and the Slovak Republic (based on own calculations and Education at a Glance 2021 (OECD, 2021[15])).3

Young people who are NEET are more likely to report limitations in their daily activities or poor health in both Australia and across the OECD. Pooling data for Australia from 2016 to 2020, the shares of 15‑19 and 20‑24 year‑olds who reported poor health or limitations in activities were around two to three times as elevated among NEET as among non-NEET youth (Figure 1.5, Panel B). The degree of limitations also plays a role, as young people with more severe rather than moderate limitations are more likely to be NEET (OECD, 2016[10]). Young people who struggle with mental health disorders are likewise known to be at a higher risk of becoming NEET, as are young people with special education needs (Brussino, 2020[16]).

Young people who are NEET are also more likely to live with (a) parent(s) who did not complete upper secondary education or who were not employed at the time of the survey. The differences in particular for parental education are remarkably similar between Australia and the OECD on average: In both the 15-19 and 20-24 year‑old categories, among young people still living with at least one of their parents, around 25% of NEET and 7‑9% (in Australia) and 11‑12% (OECD average) of non-NEET youth had parents whose highest education level was less than upper secondary school. For the group of young people still living with at least one parent, the share of those whose parent(s) are not working for pay is three times more elevated among individuals who are NEET than among those who are not.

Across the OECD as well as in Australia, other marginalised groups are also likely to experience more frequent periods of not being in education, training or employment, but reliable statistics may be difficult to find. These groups can include refugees, individuals who are currently or have in the past been in the child protection or out-of-home care system, who have been in contact with the justice system, who have substance abuse issues or who have been or continue to experience insecure housing or homelessness, or domestic violence. In a sample of young people aged 15-25 who first accessed services at one of the headspace centres (centres providing integrated mental health, substance abuse prevention and employment services to teenagers and young adults), Indigenous youth, young people experiencing homelessness and having substance use disorders had higher odds of being NEET rather than in education or working full-time as otherwise similar young people who did not share these characteristics (Holloway et al., 2018[17]).

1.3. The implications of NEET characteristics for potential preventive interventions

The reasons why a young person is NEET are often manifold and may be related to more than one factor. Some of the factors are related to the background of the young person, such as their socio‑economic background, the level of engagement of their parents, whether they live in an urban or a rural area, how remote the location is from major urban centres, whether they have special education needs (i.e. learning disabilities, physical impairments or mental health disorders), etc. Others are related to their behaviour (which in turn can be influenced by their social environment), such as whether they engaged in truancy from a young age. Yet others are related to their environment, such as the quality of schools, the affordability of further education, and current local economic conditions.

Some of the factors that can either raise or lower the risk of a young person becoming NEET, especially during their teen years and early twenties, can potentially be addressed through policy interventions aimed at children and teenagers of (lower) secondary school age. Accordingly, the following chapter will focus on educational interventions (which can, among other things, increase the chances that a student successfully completes upper secondary school), pre‑employment interventions (which can improve the match between the chosen educational and training trajectories and boost motivation to perform), and interventions within vocational education and training (which can ease the school-to-work transition). Preventive interventions that lower the risk of a young person experiencing for example homelessness, substance abuse disorders and deteriorating mental health, could also have a beneficial impact on school and labour force participation. However, they generally fall outside the scope of this report, but would ideally be part of a comprehensive NEET prevention policy.

Other characteristics associated with being NEET can point towards high-risk groups that may need further targeted support. For example, the profile of boys and girls who are NEET differ, suggesting that some interventions may have to be adjusted to their specific needs. Young First Nations peoples, young people with physical impairments, learning disabilities or mental health disorders, and young people living in rural and remote areas or growing up in poverty, face structural disadvantages. These disadvantages can include attending schools with fewer means, struggling with hunger, or facing discrimination that can make it more difficult for them to thrive at school and to transition into the labour market, again suggesting that policy makers need to keep these factors in mind when designing preventative interventions. Different student characteristics can also intersect with one another to give rise to more diverse student needs and risks factors (Box 1.1). These intersections can be taken into account to better target the needs that students may have and prevent the risk that young people will enter the NEET status, though doing so is fraught with difficulties.

That being said, policy makers also need to be clear-eyed about the limits of pre‑employment and education policies and interventions targeted at teenagers in their early to mid-teens in preventing later NEET spells. On the one hand, the labour market conditions young people encounter once they leave education can make it difficult for even the best-prepared person to find employment; and changing life circumstances such as newly emerging physical and mental health issues can lead to additional struggles. Labour market and social policies, the availability of early childhood education and care programmes for young parents, and access to (mental) health services all have an important role to play in addressing obstacles that could not be eliminated through preventive policies. In addition, overall economic and labour market policies can help maintain a favourable economic environment for hiring; and educational and financial aid policies can ensure that financial considerations do not keep otherwise interested and qualified young people from accessing higher education to the extent that they would wish to.

On the other hand, by the time that young teenagers reach lower secondary school, they have already been shaped by their earlier childhood experiences. Some unfortunately already carry a severe burden of disadvantage whose impacts targeted education policies can help lighten, but likely not eliminate entirely. Certain individual characteristics that influence academic and employment achievement, such as resilience, persistence, and a growth mindset, can be influenced by interventions up to a certain degree but are somewhat “hard-wired” based on genetic factors and (early) childhood experiences.

Box 1.1. Adopting an intersectionality lens in the design of preventative NEET policies

The term intersectionality has gained attention in research on social stratification because of Crenshaw’s landmark study of the unique disadvantage experienced by African-American women (Crenshaw, 1991[18]). The term considers the fact that individuals’ identities and experiences at school, work and society more widely are determined by a wide set of characteristics that interact with each other.

An intersectional approach to the analysis of why some individuals are at a higher risk of becoming NEET and how this risk can be reduced recognises that many individual and contextual factors shape outcomes and that such factors do not operate in isolation but depend on individuals’ exposure to other risk and protective factors (Hancock, 2007[19]; Bowleg, 2008[20]). The adoption of an intersectional approach requires policy makers to develop and implement interventions that recognise the wide heterogeneity of individual experiences and are flexible and adaptable enough to address specific forms of marginalisation and disadvantage (Christoffersen, 2021[21]).

Dimensions typically considered in intersectional approaches include sex and gender identity, age, religiosity, socio‑economic status, ethnic minority/Indigenous status, migration background, neurodiversity and health status. The adoption of an intersectionality approach further recognises the role played by the interaction of individuals with macro environments (Hankivsky et al., 2014[22]). For instance, while individual experiences of discrimination are often symptoms of non-mutually exclusive macro-level systems and structures of power, such as sexism and racism (Hill Collins and Bilge, 2016[23]).

Researchers and policy makers can find it challenging to apply the concept of intersectionality in their analysis and policy design, but without doing so, they are unlikely to be able to adequately identify and address individual needs (Hankivsky and Cormier, 2011[24]). Addressing the diverse needs of students’ intersecting identities ultimately happens in individual classrooms by teachers and other school staff. Stakeholders in the education sector therefore need adequate resources and support to implement school-level interventions. Furthermore, attracting a diverse teaching force can have positive effects on student learning outcomes, and reduce absences, suspensions and dropouts (Brussino, 2021[25]). The representation of diversity among education professionals can help students identify congruent role models.

The adoption of an intersectionality lens to policy design and implementation can also improve the efficacy of policy outcomes. Policy approaches focused on single dimensions of diversity or taking an “additive” perspective can lead to marginalised groups competing with one another for limited amounts of available resources (Hankivsky and Cormier, 2011[24]). An intersectional approach can not only prevent “targeted” interventions that disproportionately benefit small groups but can also enable the development of more efficient and responsive policies. It also encourages considerations of micro- and macro-level influences that shape individuals’ experiences (Bowleg, 2012[26]). Including socio-structural factors in an analysis can transform research to explicitly consider the role of systemic factors for individual outcomes. Such a focus on structural factors can also encourage interventions on a structural level, rather than just addressing issues on the individual or group level.

Finally, an intersectional perspective can incentivise the development of cost-efficient policies and interventions well-targeted at the populations with the highest needs (Bowleg, 2012[26]; Hancock, 2007[19]). Focusing on a single dimension of diversity ignores heterogeneity and may thus fail to address all members of the targeted group. An intersectional lens can help examine whether policies are having their intended effect and are reaching the full population of interest, encouraging policy success.

A challenge to the adoption of an intersectionality lens to evidence‑based policy making is lack of adequate data and the inherent difficulty in effectively interpreting the multiplication of risk that arises from the intersection of several dimensions. Identifying the multiplicative rather than the cumulative nature of disadvantage and the heterogeneity of risk across several dimensions requires having data with information on all dimensions and large samples for very specific groups of young people. One possibility is to rely on administrative data across several policy domains and complement these with social survey containing information not typically collected in administrative sources, such as data on their perceptions, attitudes and aspirations. Crucially, the development and use of such data for policy making should be accompanied by robust data privacy infrastructures and ethical reviews. Not only certain dimensions that characterise individual experiences may be sensitive, but the very nature of intersectional research poses unique ethical challenges since it might lead to increased identifiability of individuals and the possible stigmatisation of specific population groups.

1.4. Reducing the shorter- and longer-term risks of becoming NEET

Lowering the chances that young people will become NEET through educational, training, and pre‑employment interventions requires a collaborative approach across different policy areas and actors, including between educational and employment stakeholders and the local community. Preventive strategies can target either all students or specific groups who are at a higher risk of becoming NEET, such as students from disadvantaged backgrounds, students in remote geographic areas, students belonging to First Nations communities, and students with special education needs.

The remainder of this report presents educational, pre‑employment, and vocational education policies and interventions intended to improve educational attainment and later labour market outcomes in place across OECD countries. For each of these areas, the upcoming chapters briefly list selected existing policies in Australia. An attempt was made to cover most applicable national-level policies, while any discussed state or local-level policies and interventions are included for illustrative purposes and do not necessarily offer a comprehensive overview of all relevant policies and interventions in Australia. This overview is followed by a more in-depth discussion of interventions across the OECD. Whenever possible, it discusses the strengths of the evidence on (a) how impactful the intervention is in reducing the shorter- and longer-term risk of young people becoming NEET; and (b) for which group the risk reduction typically occurs. Each chapter concludes with a set of key policy lessons.

References

[9] AIHW (2018), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra.

[6] AIHW (2015), National Youth Information Framework (NYIF) indicators: Teenage mothers, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/national-youth-information-framework-nyif-indicato/contents/factors-influencing-health/teenage-mothers (accessed on 17 November 2022).

[26] Bowleg, L. (2012), “The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health”, American journal of public health, Vol. 102/7, pp. 1267-1273, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750.

[20] Bowleg, L. (2008), “When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research”, Sex Roles, Vol. 59/5-6, pp. 312-325, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z.

[13] Brunet, S. (2019), The transition from school to work: the NEET (not in employment, education or training) indicator for 20- to 24-year- olds in Canada, Statistics Canada.

[25] Brussino, O. (2021), “Building capacity for inclusive teaching: Policies and practices to prepare all teachers for diversity and inclusion”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 256, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/57fe6a38-en.

[16] Brussino, O. (2020), Mapping policy approaches and practices for the inclusion of students with special education needs, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[21] Christoffersen, A. (2021), “The politics of intersectional practice: competing concepts of intersectionality”, Policy & Politics, Vol. 49/4, pp. 573-593, https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321x16194316141034.

[18] Crenshaw, K. (1991), “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color”, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 43/6, p. 1241, https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

[7] Department of Education (2022), Higher Education Student Data, https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data (accessed on 11 January 2023).

[11] Dinku, Y. (2021), “A longitudinal analysis of economic inactivity among Indigenous youth”, Australian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 24/1, pp. 26-44.

[19] Hancock, A. (2007), “When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm”, Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 5/01, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592707070065.

[24] Hankivsky, O. and R. Cormier (2011), “Intersectionality and Public Policy: Some Lessons from Existing Models”, Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 64/1, pp. 217-229, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912910376385.

[22] Hankivsky, O. et al. (2014), “An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity”, International Journal for Equity in Health, Vol. 13/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x.

[23] Hill Collins, P. and S. Bilge (2016), Intersectionality, Polity Press.

[17] Holloway, E. et al. (2018), “Non-participation in education, employment, and training among young people accessing youth mental health services: demographic and clinical correlates”, Advances in Mental Health, Vol. 16/1, pp. 19-32, https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2017.1342553.

[8] National Indigenous Australians Agency (2022), “Table D1.18.3: Persons (18 and over) reporting high/very high levels of psychological distress, by Indigenous status, remoteness, age, sex and jurisdiction, 2017–18 and 2018–19”, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-18-social-emotional-wellbeing#findings (accessed on 17 November 2022).

[4] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

[15] OECD (2021), Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en.

[5] OECD (2021), Investing in Youth: Slovenia, Investing in Youth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c3df2833-en.

[3] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[2] OECD (2021), “What have countries done to support young people in the COVID-19 crisis?”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac9f056c-en.

[10] OECD (2016), Investing in Youth: Australia, Investing in Youth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257498-en.

[1] OECD (2016), Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en.

[14] Scharle, Á. (2020), “Schooling and Employment of Roma Youth: Changes Between 2011 and 2016”, in The Hungarian Labour Market 2019, Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies.

[12] Venn, D. (2018), “Indigenous youth employment and the school-to-work transition”, CAEPR 2016 Census Paper, No. 6, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences.

Notes

← 1. Since the start of the project, the Department of Education, Skills and Employment has been superseded by the Department of Education and the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations.

← 2. Identifying the underlying reasons for the difference in NEET rates would require further analysis.

← 3. “Native‑born” and “foreign-born” is standard OECD terminology and is retained here to enable comparability across countries and ensure consistency across publications.