After a brief history of green budgeting, this chapter describes existing green budgeting frameworks and green budgeting tools that are commonly used at the subnational level. Such tools including green budgeting tagging, environmental tax reforms, climate and environmental impact assessments and green budget statements. A diversity of green budgeting practices has emerged in the past two decades at both national and subnational levels. Concurrently, international organisations working on the topic, including the OECD, have introduced frameworks to support governments in implementing green budgeting.

Aligning Regional and Local Budgets with Green Objectives

2. A primer on green budgeting: International, national and subnational perspectives

Abstract

Green budgeting involves a systematic approach to assess the overall coherence of the budget relative to a country, region, or municipality’s climate and environmental agenda and to mainstream environmental and climate action across all policy areas and within the budget process (EC/OECD/IMF, 2021[1]).

It is essential that a green budgeting practice is adapted to the competences of the level of government implementing it and to their green objectives. Given this need to adapt green budgeting to national and local contexts, a diversity of practices has emerged in the past two decades at both national and subnational levels. Concurrently, international organisations working on the topic have introduced frameworks to support governments in implementing green budgeting, and several fora have been established to allow for collaboration and sharing of knowledge and best practices. After a brief history of green budgeting, this chapter describes existing green budgeting frameworks and commonly used green budgeting tools, especially at the subnational level.

A brief history of green budgeting

The term “green budgeting” first emerged in 1987 from the Brundtland Commission’s report, which recommended that “the major central economic and sectoral agencies of governments should now be made directly responsible and fully accountable for ensuring that their policies, programmes, and budgets support development that is ecologically as well as economically sustainable” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987[2]). This report was followed by the experimental integration of environmental considerations into public financial management in the late 1980s in countries such as Norway, which introduced an Environmental Profile of the State Budget in 1989, and France, which around the same time introduced a compulsory report on environmental protection expenditure (jaune budgétaire) to be appended to the annual finance law (Gonguet et al., 2021[3]). Italy was also a frontrunner in this area; in 1999, the Parliament instructed the national government to highlight all environment-related resource allocations in the annual budget to produce an “environmental budget (ecoBilancio)” alongside the draft budget. The practice has continued ever since with the latest ecoBilancio released in 2022 (MEF, 2022[4]).

In parallel, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a handful of subnational governments in Europe began experimenting with linking environmental considerations to their budgetary processes using methodologies such as the ecoBudget (Box 2.1) and the City and Local Environmental Accounting and Reporting (CLEAR) method (Chapter 3). These initiatives focused on developing local environmental targets and identifying indicators to track the progress towards meeting said targets, which is a pre-requisite step for undertaking a more comprehensive green budgeting approach.

Box 2.1. The ecoBudget methodology

An ecoBudget is an environmental management system for local natural resource management. It was developed by the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) for and with local authorities, in the context of the Aalborg Charter that pledged that signatories will “seek to establish new environmental budgeting systems which allow for the management of our natural resources as economically as our artificial resource, 'money'” (Aalborg Charter (ICLEI, 1994[5]), Part 1.14).

Through the use of physical, quantitative indicators to express the state of natural resources (air quality, water quality, etc), an ecoBudget can present local environmental targets and enable the monitoring of the state of the (local) environment in relation to these targets. In essence, it budgets natural resources in a very similar way to financial resources, following similar principles of efficiency, transparency, and monitoring and evaluation and following a similar cycle of development and reporting as would be used for a financial budget. Environmental resources are not monetised as part of an ecoBudget nor is it directly linked to a local government’s financial budget; however, it is possible to make this link by integrating the indicators and targets developed in the ecoBudget into the financial budget.

The ecoBudget methodology was developed in 1996 in Germany by four municipalities – Dresden, Nordhausen, Bielefeld, and Heidelberg – in co‑operation with ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability. In 2003, ecoBudget was expanded across Europe as part of the European Union (EU)’s LIFE programme. Six cities took part in piloting the methodology outside of Germany: Växjö (Sweden), Amaroussion (Greece), Bologna (Italy), Ferrara (Italy), Kalithea (Greece) and Lewes (United Kingdom).

Växjö’s ecoBudget

In recent decades, the municipality of Växjö has emerged as a climate leader, in part due to its pioneering implementation of the ecoBudget environmental management system beginning in 2003. In Växjö, the ecoBudget is used to track and measure progress towards the long-term targets of the municipality’s Environmental Programme. To achieve this, environmental resource use objectives and a corresponding set of indicators are incorporated into draft budget programmes during the financial budget preparation phase and the entire budget is voted on by the city council. Each municipal department is then responsible for achieving the objectives relevant to them and for incorporating the budget indicators into their action plans. Symbols such as smileys and arrows were developed to monitor the progress of the ecoBudget; a practice that has since been used in measuring progress towards other municipal sustainability, democracy, equity and health targets. Every six months, progress reports based on the assessment of the indicators are presented to the city council, allowing for adjustments to be made in case certain objectives are not on track to being met.

Source: Energy Cities (2019[6]), Climate-mainstreaming Municipal Budgets, Energy Cities, https://energy-cities.eu/publication/climate-mainstreaming-municipal-budgets/ (accessed on 29 January 2021); ICLEI-Europe (2004[7]), The ecoBudget Guide, https://webcentre.ecobudget.org/fileadmin/user_uploads/ecoBUDGET_Manual_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022); LIFE (2004[8]), LIFE European ecoBudget Pilot Project for Local Authorities Steering to Local Sustainability, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/index.cfm?fuseaction=search.dspPage&n_proj_id=1850; ICLEI (1994[5]), Charter of European Cities & Towns Towards Sustainability, https://sustainablecities.eu/fileadmin/repository/Aalborg_Charter/Aalborg_Charter_English.pdf.

Green budgeting remained relatively unexplored until the early 2010s, when several national and subnational practices emerged, primarily in developing countries in the Asia-Pacific region, funded by developing institutions. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank in particular, have played a key role in advancing this area of work through the funding and implementation of climate budget tagging exercises in countries such as Bangladesh and Nepal. Climate budgeting, a type of green budgeting focused on climate change adaptation and mitigation, continues to develop in the Asia- Pacific region with national and subnational exercises found in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Pakistan.

In 2017, the OECD launched the Paris Collaborative on Green Budgeting (PCGB) at the One Planet Summit in collaboration with the governments of France and Mexico. The PCGB develops concrete and practical guidance to help governments at all levels embed their climate and environmental goals within their budget frameworks. It also identifies research priorities and gaps to advance the analytical and methodological groundwork for green budgeting, in addition to supporting peer-learning and the exchange of data and best practices. The work of the PCGB serves as a crucial step in achieving a central objective of the Paris Agreement on climate change as well as of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals – aligning national policy frameworks and financial flows on a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and environmentally sustainable development (OECD, 2020[9]).

In 2019, the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action was launched to foster collective engagement for a transition toward low-carbon and resilient development. Since its founding, finance ministers from over 60 countries have endorsed a set of six non-binding principles, the Helsinki Principles, which “promote national climate action, especially through fiscal policy and the use of public finance.” Among these, Principle 4 focuses on “taking climate change into account in macroeconomic policy, fiscal planning, budgeting, public investment management, and procurement practices” (Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action, 2019[10]). Green budgeting is thus an important area of work for the Coalition as it directly relates to Principle 4.

More recently, the post-COVID recovery has generated considerable additional interest in green budgeting as a tool to mainstream environment and climate action into recovery and stimulus packages (OECD, 2020[11]). An OECD survey from mid-2020 showed that 20 OECD countries had actively integrated green perspectives into their stimulus measures at that point in time (OECD, 2021[12]). In the EU, member states were encouraged to make use of green budgeting tools in developing their Recovery and Resilience Plans in order to meet the EU requirement that a minimum of 37% of funds for each plan be dedicated to climate action (Box 2.2). Moreover, the European Commission is actively promoting capacity building among member states to implement green budgeting through a technical training programme offered through its Technical Support Instrument. This programme is helping the EU to deliver on its Green Deal, which includes an explicit mention of fostering green budgeting practices within the EU (EC/OECD/IMF, 2021[1]).

Box 2.2. Green budgeting and the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plans

In December 2020, the European Council and the Parliament reached a provisional agreement on a EUR 672.5 billion Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). The aim of the RRF is to help member states to address the economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic while also ensuring that their economies undertake the green and digital transitions to become more sustainable and resilient. To receive support from the RRF, member states must prepare national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) detailing their reform and investment agendas until 2026. A minimum of 37% of each RRP’s envelope must support the transition to a carbon-neutral economy and member states must prove that the reforms and investments do no significant harm to other environmental goals. In order to determine that this conditionality is met, member states are invited to use green budgeting tagging to tag the green content of the proposed reforms or investments following the existing climate tracking methodology already applied to cohesion policy funds. Member states will have to apply a weight to each measure to determine whether it fully contributes (100%), partially contributes (40%) or has no impact (0%) to green objectives.

Source: EC/OECD/IMF (2021[1]), Green Budgeting: Towards Common Principles, European Commission/OECD/International Monetary Fund.

Existing green budgeting frameworks

With the interest in green budgeting continuing to grow globally, international institutions including the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the OECD have developed green budgeting frameworks to support all levels of government in developing and implementing their own practices. The OECD started to develop a green budgeting framework in 2020, which has served as inspiration for other complementary frameworks such as the European Commission’s and the IMF’s (Box 2.3).

The OECD’s Framework for Green Budgeting

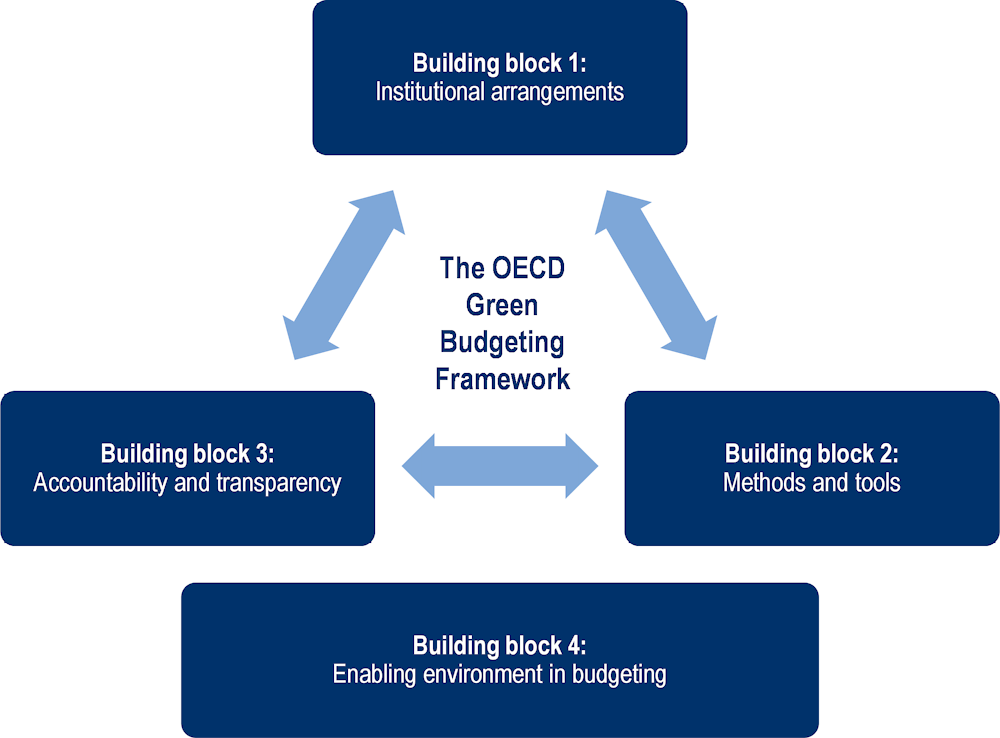

The OECD’s Framework for Green Budgeting was developed based on existing national practices and consultation with PCGB members (OECD, 2020[13]). The framework identifies four building blocks to help ensure green budgeting approaches are linked to the broader pubic financial management process and so that efforts are sustained and remain effective over time (Figure 2.1). The four building blocks are:

1. Institutional arrangements: As the first step in green budgeting, governments could set out their national plans and strategies on climate change (both for mitigation and adaptation) and the environment. Such plans and strategies help orient fiscal planning, guide public policy, investment and other decisions on revenue and expenditure to support green priorities. The strategic framework can include the scope of general government activity and budgetary items.

2. Methods and tools: Green budgeting tools can contribute to informed and evidence-based decision-making and budget preparation, and strengthen monitoring, reporting and accountability. Such tools sit within a country’s existing annual and multiannual budgetary processes.

3. Accountability and transparency: to help to embed green budgeting and assure its credibility. This can be achieved through reporting information to facilitate impartial scrutiny of the information by parliament and other oversight bodies such as independent fiscal institutions.

4. Enabling environment in budgeting: An enabling environment for green budgeting requires a strong institutional design where roles and responsibilities are clearly defined along with the timeline for actions and required deliverables and a well-designed legislative framework.

Figure 2.1. The OECD Green Budgeting Framework

Source: OECD (2020[13]), Paris Collaborative on Green Budgeting: OECD Green Budgeting Framework, http://www.oecd.org/environment/green-budgeting/.

The European Commission’s Green Budgeting Reference Framework

In January 2022, the European Commission (EC) released its Green Budgeting Reference Framework which has a two-fold purpose: to provide a toolkit for member states looking to start green budgeting or upgrade their existing practices and to serve as a reference for the EC to monitor member states’ green budgeting practices (EC, 2022[14]). The latter fulfils a commitment outlined in the Green Deal communication that the EC “will work with Member States to screen and benchmark green budgeting practices” (EC, 2019[15]). The EU framework and the OECD Green Budgeting Framework are complementary, with the latter providing the overarching structure for green budgeting and budgetary policy making within which the former, more operational framework can be applied.

The Green Budgeting Reference Framework encompasses five elements considered key for implementing green budgeting at a national level (EC, 2022[14]). The five elements are:

1. The coverage of environmental and climate objectives, of budgetary items and of public sector entities.

2. The methodology used to assess consistency of budgetary policies with green goals.

3. The deliverables, set out in a national legal provision or administrative document on green budgeting.

4. The governance structure, clearing setting out the role and responsibilities for each stakeholder.

5. And the transparency and accountability of the process and methodology.

Furthermore, depending on the ambition and comprehensiveness of a member state’s green budgeting practice with regard to these five elements, the framework classifies the practice into one of three levels: essential, developed, and advanced. Although the framework was developed at the country level, subnational governments can also use it to develop and align their own green budgeting practices, taking into account their individual budgetary contexts and capacity constraints.

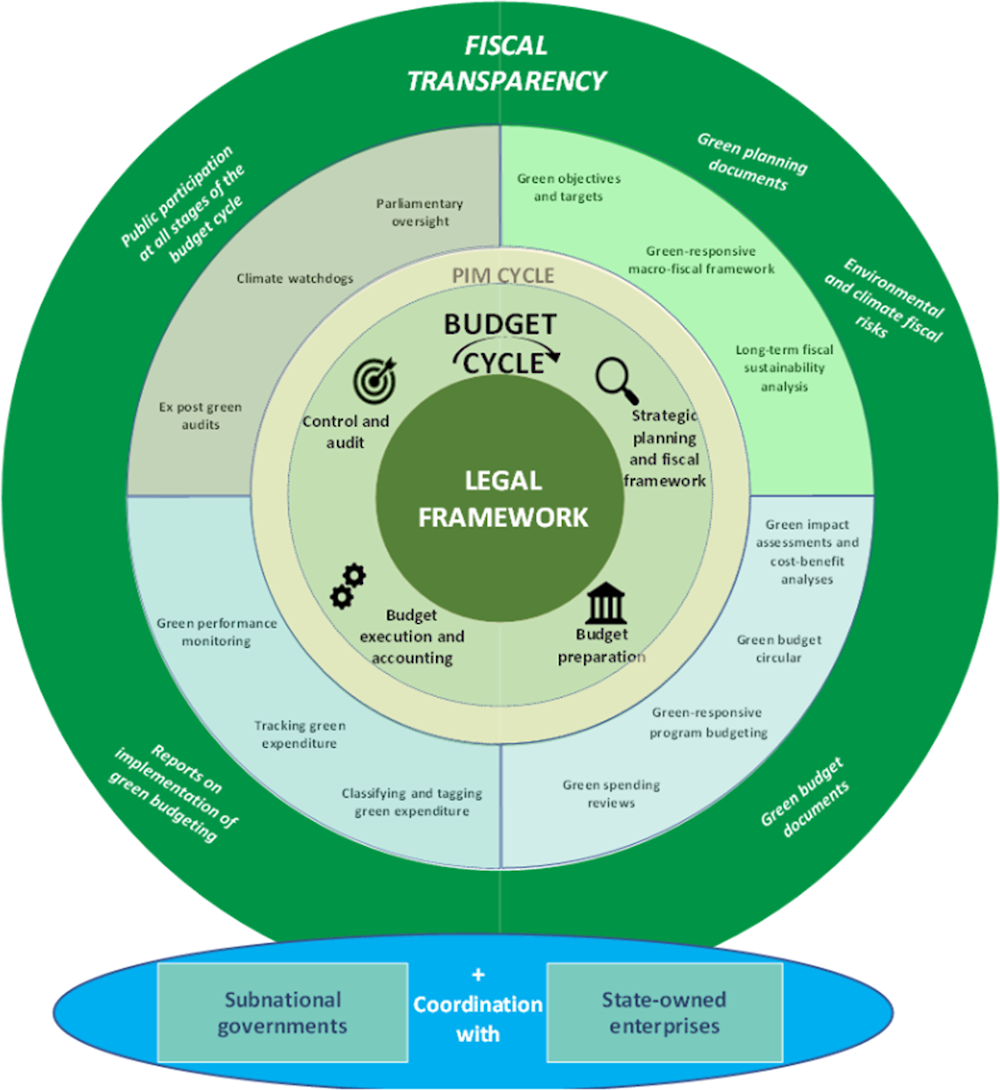

Box 2.3. The IMF’s Green Public Financial Management Framework

In addition to the OECD and EC’s green budgeting frameworks, the IMF has integrated green budgeting into its broader framework on green public financial management. The framework combines green budgeting with fiscal transparency, external oversight, and co‑ordination with state-owned enterprises and subnational governments in order to provide a comprehensive picture of the various points of entry for integrating climate and environmental considerations within the budget cycle and broader fiscal policy-making (Figure 2.2). The framework explicitly acknowledges that national governments should co‑ordinate with subnational governments in developing and adopting green PFM practices and that central governments have a responsibility in enabling green PFM reforms to trickle down to subnational levels.

Figure 2.2. A visual representation of the IMF’s Green PFM Framework

Source: Gonguet, F. et al. (2021[3]), Climate-Sensitive Management of Public Finances - “Green PFM”, International Monetary Fund.

Green budgeting tools commonly used by national and subnational governments

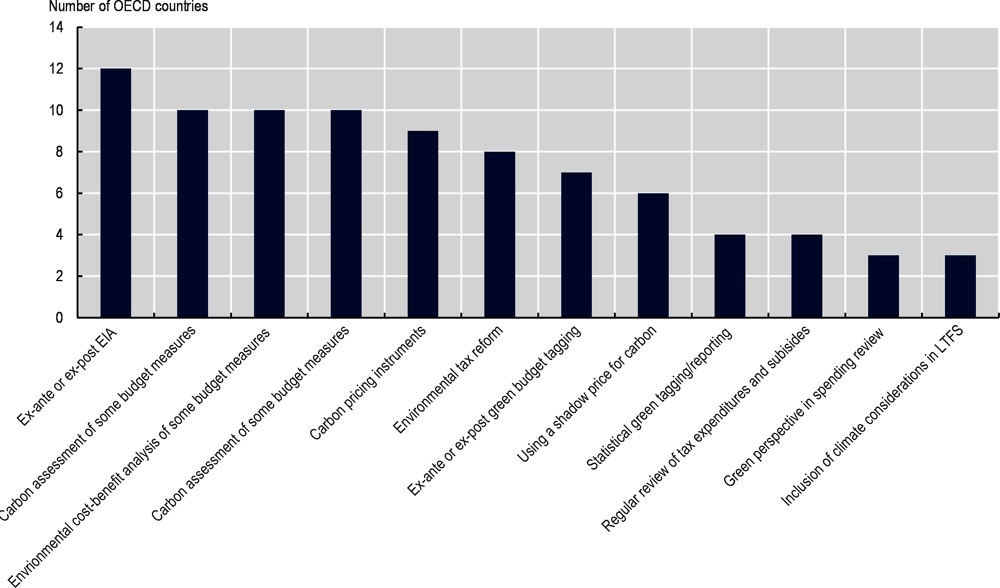

Policymakers have a variety of green budgeting tools at their disposal to be used throughout the budget process. Examples of green budgeting tools include green budget tagging, environmental impact assessments, green budget statements, ecosystem services pricing (including carbon pricing), incorporating a green perspective into spending reviews, and adding a green perspective to performance setting (OECD, 2020[9]; forthcoming[16]). Figure 2.3 provides information on the relative usage of some green budgeting tools among OECD countries, based on a survey carried out at the central government level in 2020. The list of tools included in the graph is not exhaustive but showcases the wide variety of green budgeting tools that exist.

Figure 2.3. A non-exhaustive inventory of green budgeting tools

Note: The data represents usage of tools in relation to the budget process. EIA=Environmental Impact Assessment; LTFS=Long-term Fiscal Strategy.

Source: OECD (2021[12]), Green Budgeting in OECD Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/acf5d047-en; OECD/EC (2020[17]), Joint Survey on Emerging Green Budgeting Practices.

The review of existing practices outlined in Chapter 3 of this report, found that subnational governments in the OECD and EU use many of the same green budgeting tools as national governments. In particular, the review identified that the main green budgeting tools used by subnational governments are green budget tagging, environmental tax reform, environmental and climate impact assessments, and green budget statements. Each of these tools is explored in more detail below. Additional tools are described in Box 2.6.

Green Budget Tagging

Green budget tagging is the act of classifying budget expenditures according to their impact (be it positive or negative) on the environment and climate (OECD, 2021[18]). Within the OECD Green Budgeting Framework, green budget tagging falls under Building Block 2: Budgeting tools for evidence generation and policy coherence.

Green budget tagging can be carried out ex-ante (during the budget formation stage) and ex-post (during the budget execution phase or on closed accounts), with the tool reaching its full potential to generate evidence and facilitate policy coherence when it is done both ex ante and ex post (OECD, 2021[19]; Gonguet et al., 2021[3]). Some green budgeting exercises tag positive expenditures only; such is the case in Ireland at the national level. Tags are applied to climate positive expenditure at the budget programme level and no distinction is made between climate mitigation and climate adaptation expenditure. The Irish Government plans to expand the exercise to tag climate harmful expenditure as well (Cremins and Kevany, 2018[20]). Tagging both positive and harmful expenditures provides the most comprehensive understanding of the budget’s climate and environmental impact and allows for tracking changes in harmful expenditures relative to positive ones over time. France began green budget tagging in 2019 to enhance transparency and improve evidence-based decision-making. The Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Ecological and Inclusive Transition work jointly to tag positive and negative expenditures across the entire central government budget on a graded scale (ranging from very favourable to unfavourable) for six environmental and climate axes, including climate mitigation, climate adaptation, and biodiversity (Ministère des finances, 2021[21]). France applied this same methodology to its economic recovery package, “Plan de Relance” (see Box 2.2 for more details). Recently, the EC drafted their own list of green and brown budgetary items to provide guidance to member states in developing their own green budget tagging methodologies (Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. EU List of green and brown budgetary items

To support member states in developing their own green budgeting practices, the EC drafted two lists of budgetary items whose net environmental impact could be considered broadly as ‘green’ or ‘brown’ as part of a green budget tagging exercise. These lists are not meant to be comprehensive but rather to provide some key examples of such measures to guide practitioners.

The structure of the lists loosely aligns with the Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) system. This ensures a large coverage of government functions and provides adaptability to the member states’ different budgetary structures. The lists report selected budgetary measures including expenditure, tax expenditure, and revenues. Measures are grouped within ‘sectors’ (i.e. broad functions of the government), ‘categories’, and then ‘subcategories.’ For example, the sector ‘transport’ contains the category ‘transport infrastructure’, with one subcategory being ‘sustainable and low carbon railways’. As an example of brown expenditure, the list includes the sector ‘mining, manufacturing, and construction” within which the category ‘mining’ contains a sub-category ‘unsustainable mining’ which includes measures such as a subsidy for mineral oil in the offshore petroleum sector.

The lists have been compiled drawing on information from specific member states’ budgets and environmental subsidies reports, the EU budget and various OECD and EU datasets. They have been discussed with experts and statistical representatives from member states. These lists will be uploaded on the green budgeting platform of the EC and will be updated on a yearly basis taking into account further developments, including in the environmental accounts and statistics.

Source: Gonguet, F. et al. (2021[3]), Climate-Sensitive Management of Public Finances - “Green PFM”, International Monetary Fund.

Several Asia-Pacific countries, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and the Philippines, were early adopters of budget tagging focusing on climate change adaptation and mitigation objectives (OECD, 2021[18]). In India and the Philippines climate budget tagging has also developed at the subnational level (Box 2.5). In the case of Indonesia and the Philippines, these subnational practices following the implementation of a green budgeting practice at the national level; however, in India, subnational green budgeting as emerged on its own with a national green budgeting practice in place. South Africa has also recently carried out 11 pilot climate budget tagging practice at the national, provincial and municipal levels in order to develop an operational methodology adapted to the country’s context (National Treasury, 2021[22]). The project is led by the National Treasury and has been supported by the World Bank.

Box 2.5. Subnational green budgeting practices in India, Indonesia, and the Philippines

Odisha, India

The state of Odisha, on the east coast of India, developed its own climate budget tagging methodology in 2020 and recently applied it ex-ante to the 2021-22 state budget. The investment budget of 11 departments deemed to be climate-related (agriculture, energy, forestry and environment, rural development, etc.) are tagged manually during the budget preparation phase. Tagging is centralised in the Finance Department rather than in the respective line ministries.

The methodology is unique in that it calculates both the climate change relevancy and the climate change sensitivity of expenditures using a benefits-based approach. The Climate Change Relevancy Share helps departments to identify priority expenditure programs to be considered during climate-related planning. The Climate Change Sensitivity Share is calculated to help departments identify components within expenditure programs that need to be climate-proofed via technical or financial intervention. The results of these calculations form a matrix that provide decision makers with valuable information on key follow-up areas and actions.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, the Ministry of Finance, with support from UNDP, conducted a pilot project in 2020 to implement climate budget tagging in three Indonesian provinces: Gorontalo, Riau, and West Java. The project used the same climate budget tagging methodology that has been used at the national government level since 2014. There are two steps to the subnational tagging methodology. The first step identifies expenditure items, at the output level, that have a climate adaptation or mitigation impact. The output level was chosen as it has the appropriate amount of information on the expenditure item to identify performance indicators and the amount of funds allocated. This step is done in collaboration between the Ministry of Finance and line ministries, with the line ministries providing technical input on the mitigation or adaptation impact of an output. The second step involves identifying the amount of funds allocated to each output. The entire process takes place during the budget preparation phase

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Climate Change Act of 2009 and the National Climate Change Action Plan both stipulated the need for the central government to develop a climate-responsive budget. To do so, the central government adopted climate budget tagging to prioritize and assign codes to climate change programs, activities, and projects in the annual budgets of national government agencies.

As of 2015, subnational governments are also required to tag climate programs, activities, and projects during the preparation of their annual investment programmes. The central government, through the Department of Budget Management, the Climate Change Commission, and the Department of Interior and Local Government, developed a Climate Change Typology for Local Government. This typology is a list of climate change adaptation and mitigation activities derived from the National Climate Change Action Plan, and grouped according to the strategic priorities of the plan. When preparing their annual investment programmes, subnational governments use the typology to determine whether the objectives and outcomes of their planned programs or projects are climate change adaptation or mitigation related. If at least one objective is an adaptation or mitigation measure, the subnational government considers the entire program or project budget as a climate change expenditure. If only specific components are adaptation or mitigation measures, then only the budgets for those specific components are considered as climate change expenditures.

Source: Government of Odisha (2021[23]), Climate Budget 2021-22, Government of Odisha; (Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, 2020[24]), The Contribution of Subnational Governments in the Implementation of NDC in Indonesia, http://www.id.undp.org. Government of the Philippines (2021[25]), Climate Change Expenditure Tagging for Local Government, https://climate.gov.ph/files/CCET%20LGU%20Final.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

Environmental tax reform

Environmental tax reform (ETR) refers to “bringing about a ‘tax shift’ in which a progressive increase in the revenues generated through environmentally related taxes provides a rationale for reducing taxes derived from other sources, such as income, profits and employment, the taxation of which is less desirable” (OECD, 2017[26]). Among OECD and EU countries, ETR is the main revenue related green budgeting tool used and can complement the use of green budget tagging when a tagging practice also assesses the green impacts of budgetary revenue sources.

Environmental taxation has emerged in recent decades as an important tool that national and subnational governments alike can use to combat climate change. Environmentally related taxes refer to any “compulsory, unrequited payments to general government levied on tax-bases deemed to be of particular environmental relevance” (OECD, 2004[27]). Environmental taxation has emerged in recent decades as an important tool that national and subnational governments alike can use to combat climate change. Carbon taxes, perhaps the most well-known of environmental taxes, are just one of a variety of existing environmentally related taxes which also include energy taxes, transport taxes, and pollution taxes, among others.

Tracking and comparing subnational green revenues, however, requires accounting for varying degrees of subnational revenue autonomy between countries. The ultimate goal of green budgeting exercises is to incorporate the evidence gathered into budgetary decision-making processes; however, subnational governments with limited revenue autonomy may be constrained in their ability to act on the results of a revenue analysis.

Climate and environmental impact assessments

Impact assessments are a key component of Building Block 2 of the OECD Framework for Green Budgeting, directly contributing to evidence gathering about the environmental and climate impact of budgetary policies (OECD, 2021[12]). Impact assessments are most commonly carried out ex-ante on proposed budget items to allow for comparison with alternative programmes or policies and to improve alignment with existing policy goals. It is also possible to conduct them ex-post. Impact assessments can be applied to individual budget programmes, measures, or even to the entire budget itself, and can vary with regards to the scope from purely carbon dioxide emissions to biodiversity impacts as well. Carbon impact assessments of individual policies or of the budget as a whole are rare among OECD members but the few existing cases in Scotland and Norway provide a starting point for future endeavours in this area.

Green Budget Statements

A green budget statement is a comprehensive report on the ex-ante environmental or climate impact of a draft budget (OECD, 2021[12]). Published alongside, or contained within, the draft budget, a green budget statement consolidates the information collected from other green budget tools such as environmental impact assessments, green budget tagging, and environmental fiscal reform. This tool falls under Building Block 3: Accountability and Transparency of the OECD Green Budgeting Framework.

Box 2.6. Examples of additional green budgeting tools

Performance frameworks: Performance frameworks enhance the effectiveness of public policy by linking inputs to results. Performance budgeting supports green budgeting through the inclusion of performance measures that refer to relevant climate and environmental considerations.

Carbon costing and measurement tools: Carbon tools include carbon assessment of budget measures, carbon-pricing instruments including fuel and carbon taxation, emissions trading systems and the use of a shadow price of carbon to evaluate public policies and investment.

Environmental cost-benefit analysis: An analysis of the cost and benefits of a budget proposal that takes into account the environmental consequences that affect the natural environment.

Green spending reviews: Green spending reviews consider the extent to which ministries and governmental agencies can transition to net-zero emissions and environmentally sustainable operations.

Source: EC/OECD/IMF (2021[1]), Green Budgeting: Towards Common Principles, European Commission/OECD/International Monetary Fund.

References

[10] Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action (2019), Helsinki Principles, https://www.financeministersforclimate.org/sites/cape/files/inline-files/FM%20Coalition%20-%20Principles%20final.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2022).

[20] Cremins, A. and L. Kevany (2018), An Introduction to the Implementation of Green Budgeting in Ireland, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform.

[14] EC (2022), European Commission Green Budgeting Reference Framework, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/european_commission_green_budgeting_reference_framework.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

[15] EC (2019), The European Green Deal COM(2019)640, European Commission, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

[1] EC/OECD/IMF (2021), Green Budgeting: Towards Common Principles, European Commission/OECD/International Monetary Fund.

[6] Energy Cities (2019), Climate-mainstreaming Municipal Budgets, Energy Cities, https://energy-cities.eu/publication/climate-mainstreaming-municipal-budgets/ (accessed on 29 January 2021).

[3] Gonguet, F. et al. (2021), Climate-Sensitive Management of Public Finances - “Green PFM”, International Monetary Fund.

[23] Government of Odisha (2021), Climate Budget 2021-22, Government of Odisha.

[25] Government of the Philippines (2021), Climate Change Expenditure Tagging for Local Government, https://climate.gov.ph/files/CCET%20LGU%20Final.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

[5] ICLEI (1994), Charter of European Cities & Towns Towards Sustainability, Local Governments for Sustainability, https://sustainablecities.eu/fileadmin/repository/Aalborg_Charter/Aalborg_Charter_English.pdf.

[7] ICLEI-Europe (2004), The ecoBudget Guide, https://webcentre.ecobudget.org/fileadmin/user_uploads/ecoBUDGET_Manual_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

[8] LIFE (2004), LIFE European ecoBudget Pilot Project for Local Authorities Steering to Local Sustainability, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/index.cfm?fuseaction=search.dspPage&n_proj_id=1850.

[4] MEF (2022), Ecobilancio 2022, Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze, https://www.rgs.mef.gov.it/VERSIONE-I/attivita_istituzionali/formazione_e_gestione_del_bilancio/bilancio_di_previsione/ecobilancio/.

[21] Ministère des finances (2021), Rapport sur l’impact environnmental du budget de l’État, https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/2021/Rapport_impact_environnemental_budget_Etat_2022.pdf?v=1633948985 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

[24] Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia (2020), The Contribution of Subnational Governments in the Implementation of NDC in Indonesia, http://www.id.undp.org.

[22] National Treasury (2021), Climate Budget Tagging in South Africa, https://www.cabri-sbo.org/uploads/files/Documents/Session-4-South-Africa.pptx (accessed on 7 June 2022).

[19] OECD (2021), Green Budget Tagging: Introductory Guidance & Principles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fe7bfcc4-en.

[18] OECD (2021), Green Budget Tagging: Introductory Guidance & Principles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fe7bfcc4-en.

[12] OECD (2021), Green Budgeting in OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acf5d047-en.

[11] OECD (2020), “Green budgeting and tax policy tools to support a green recovery”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bd02ea23-en.

[9] OECD (2020), Inventory of Building Blocks and Country Practices for Green Budgeting: The OECD Framework for Green Budgeting, OECD, Paris.

[13] OECD (2020), Paris Collaborative on Green Budgeting: OECD Green Budgeting Framework, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/environment/green-budgeting/.

[26] OECD (2017), Environmental Fiscal Reform: Progress, Prospects and Pitfalls, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-and-environment.htm.

[27] OECD (2004), Environmentally Related Taxes, OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6270 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

[16] OECD (forthcoming), Green Budgeting Composite Indicator, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[17] OECD/EC (2020), Joint Survey on Emerging Green Budgeting Practices.

[2] World Commission on Environment and Development (1987), Our Common Future Towards Sustainable Development, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).