This chapter outlines the context of the Finnish government system and its major administrative reforms that have contributed to its image of one of the best governance systems in the world. Throughout years of discussion and advancements of the governance system anticipation and systems approaches to tackle complex issues have been outlined as areas where the governance system has the most to improve.

Anticipatory Innovation Governance Model in Finland

4. Finland – a country where governance matters

Abstract

Finland – a relatively small country with a population of 5.5 million with one of the most sparsely populated territories in Europe (next to Iceland and Norway) – is internationally recognised for its achievement in public sector reform and for its focus on constant enhancement of its public governance (European Commission, 2020[1]; Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020[2]). Historically, the Finnish administration and government has gone through the traditional paradigms from classical public administration, to New Public Management (NPM) to a move towards a more participatory, new public governance approach (Lähteenmäki-Smith et al., 2021[3]). The country is known for high respect for the rule of law, high levels of administrative ethics (Salminen and Ikola‐Norrbacka, 2010[4]; Transparency International, 2020[5]) and high trust in government (OECD, 2021[6]). While Finnish society and public governance are known for leading the way in numerous international comparisons, successive governments in Finland have focused on the challenges they face in steering strategy setting and implementation effectively. One of the areas where the Finnish government considers that it needs to improve is connected to anticipation and systems approaches to complex problems (Anttila et al., 2018[7]).

In previous public governance reviews, the OECD (2010[8]; 2015[9]) noted that the government had lost some of its strategic agility and that governance was too fragmented between silos, lacking adequate co-operation models between ministries (Määttä, 2011[10]). The 2010 OECD review also highlighted the need to show more attention to strategic foresight and its role in policy making as the function was not integrated with the traditional policy making system. Since then and especially in recent years, the government has invested heavily in renewing its strategic foresight system (discussed in more detail in the following chapter). The 2015 joint public governance review with Estonia shed light on the need to institutionalise whole-of-government approaches and increase resource flexibility (OECD, 2015[9]). For example, the Prime Minister’s Office often shares the whole-of-government leadership role with the Ministry of Finance, whose minister is usually a leading figure in a different party to the Prime Minister in the coalition government. This can sometimes lead to fragmented strategic decision making (OECD, 2015[9]). Based on these insights, successive governments have kept focusing on improving the public governance system in particular introducing mechanisms to increase government agility and capacity to steer the system towards an effective implementation of the government strategy. Taking these and additional insights from the reviews into account, the government has launched several systematic projects and programmes to examine the role of different functions in government over the last decade (see Box 4.1 below). This has also led the Finnish government to look at ways to anticipate better, learn continuously and integrate evidence-informed approaches into its government. The current Government Programme has recognised the need for systemic change within Finnish society1 which can only be achieved through a rethinking of how government functions and interact with other institutional actors in the system. Among others, the Government Programme explicitly pledges:

“for continuous learning in government amid constant changes, we do not imagine we know in advance what will work and what will not. Instead, we will seek out information and conduct experiments so that we can act in ways that will benefit our citizens.”

“for long-term policy-making. We commit to taking account of long-term objectives and to engaging in systematic parliamentary co‑operation between the Government and Parliament. We can reach our long-term objectives by introducing new practices for co‑operation between Parliament and the Government.”

“for knowledge-based policy-making. Legislative preparation of a high quality is a key condition for the credibility and legitimacy of policy-making. We commit to knowledge-based policy-making and systematic impact assessment in all legislative preparation. We will engage in deeper co‑operation with the scientific community.”

Box 4.1. Recent public governance reform projects in the Government of Finland

KOKKA Project for Monitoring the Government Programme (2010-2011)

The project was launched to reform the centre of government steering functions to improve the translation, implementation and monitoring of the Government Programme. The recommendations of the project draw attention to government silos, resource allocation rigidity and the need for evidence- informed decision making.

Governments for the Future (2012-2014)

The project was launched by the Ministry of Finance and the Prime Minister’s Office in partnership with Sitra (the fund for innovation operating directly under the Finnish Parliament) to discover new ways to execute significant state administration reforms. In particular the work concentrated on the need to increase the use of systems approaches in the Government of Finland.

OHRA project (2014-2015)

The project was based on a steering framework that was tasked to prepare recommendations for the next parliamentary term after the elections in the first quarter of 2015, in order to improve the impact and effectiveness of government actions. The OHRA activities identified the horizontal nature of many new policy problems, the lack of an evidence base in policy making, and the gap in the feedback loop within the policy-making system from policy implementation to policy design. Finland was seen as a “legalistic society” where regulation was used as the main vehicle of change. The final report among other recommendations proposed that a major part of the research funding supporting government decision making (the so-called TEAS function) should be allocated to the needs of the Government Action Plan.

Experimental Finland project (2016-2019)

Experimental Finland project (2016-2019). The project designed by the Prime Minister’s Office involved a dedicated Experimental Finland Team in the organisation engaged with three types of experiments: strategic experiments (policy trials), pilot pools/partnerships (regionally relevant or sector-specific experiments) and grassroots-level experiments (municipalities, regions, academics, charities, etc.). The results of the project are covered in more detail in Chapter 3 of this report.

Pakuri project (2019)

The one-year project of the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Finance, and supported by a parliamentary group, was put together to provide recommendations for the Government. The goal was to improve the co‑ordination of policy making and resource processes, make the co‑ordination and implementation of government policy more effective, strengthen the joint government communications and ensure policy preparation that extends across parliamentary terms.

Governance is also one of the strategic themes within the Programme with some key operational action points including:

Management of the strategic Government Programme, with among others, includes the creation of parliamentary committees that were appointed to carry out the preparations of long-term reforms extending across parliamentary terms. These were supported by strategic ministerial working groups, and by strategic agreements with the ministries under the leadership of the Prime Minister's Office.2

The creation of strategic ministerial working groups for the duration of a parliamentary term to support the Government Session Unit of the Prime Minister's Office to draw up a description of the current situation, assign specific tasks, perform impact assessments and develop indicators suitable for monitoring the measures contained in the programme.3

Commitment to become the best public administration in the world. For this the Government has prepared the public governance strategy4 which will guide and strengthen the renewal of public governance as a whole from 2020 to 2030. The strategy seeks to strengthen the presence of public administration in the daily life of the Finnish people across the country. As part of its strategy work, the Government will improve risk management in public administration and reinforce the public administration’s ability to respond to crises that occur in normal conditions. The strategy pledges to: “make systematic foresight and future thinking a key part of management and also of policy preparation and decision making processes.” 5

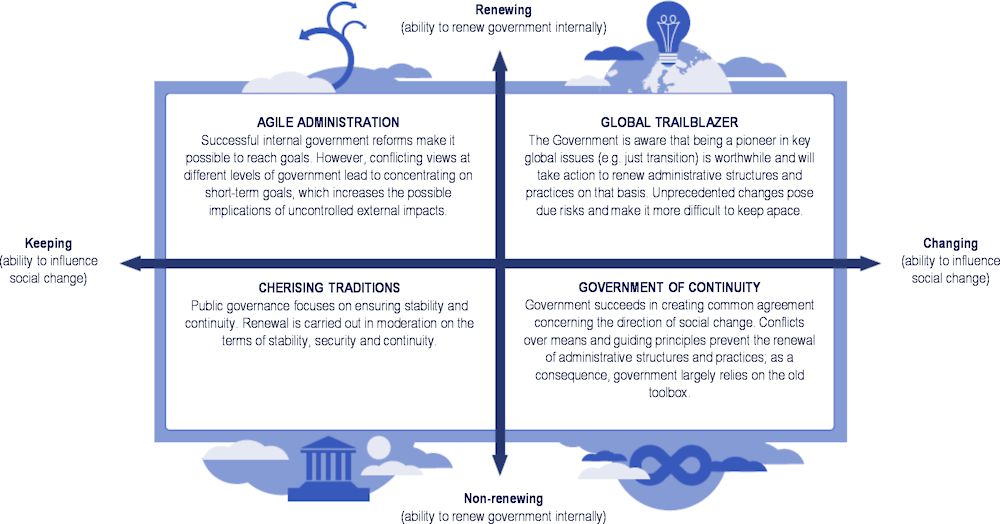

These elements fit into a central governance steering system where the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Finance act as the main cross-government steering bodies. Known for coalition governments, the Prime Minister tends to take the overall lead for whole-of-government activities and cross-cutting topics; while the Minister of Finance tends to lead through fiscal planning, public service development, and digitalisation. Looking ahead for the next decade (Figure 4.1) the Finnish government aims to identify areas where government can be renewed to reach ambitious goals while maintaining the values of stability and continuity in policy making. The recent Steering20206 work revealed that the major elements for an anticipatory approach in the Finnish governance system already exist, but they are rarely put into practice in concrete day-to-day work and implementation (Lähteenmäki-Smith, 2020[13]; Lähteenmäki-Smith et al., 2021[3]).

Figure 4.1. Future scenarios of the capabilities of public governance for change in 2030

An example of how elements of an anticipatory government function have started to be introduced in the public governance system in Finland is the growing interest in a ‘phenomenon-based’ approach to policy making (Sitra (2018[15]); see Box 4.2). Phenomenon-based policy making means addressing phenomena (e.g. climate change, social disintegration, urbanisation, and immigration) for which no single part of the system holds full responsibility for and which require the collaborative interaction of different parts of a system. This often requires establishing cross-ministerial policy networks and the ability of government to aggregate financial and human resources from across individual entities to cross-administrative objectives to achieve higher impact. The main idea is that societal problems (e.g. climate change, social disintegration, urbanisation, and immigration) tend to get lost in government silos and ‘projectification’ of government action (Hodgson et al., 2019[16]), meaning that the money in government is divided into small projects that do not sufficiently follow cross-administrative objectives and needs and their combined impact remains unclear. Actors across the government have drawn attention to this issue, in particular, the Committee of the Future in the Parliament and also the National Audit Office (Eduskunta, 2018[17]; Varis, 2020[18]). This has led to pilot research in phenomenon-based budgeting connected to child budgeting and the adjustment of the Government’s rules of procedure, requiring Permanent Secretaries to be responsible for cross-sector co‑ordination (200/2018, Government Rules of Procedure). A working group in the Ministry of Finance addressed phenomenon-based budgeting in 2018–2019 and also presented the findings to the Parliament of Finland. Yet, it is still unclear if new models around phenomenon-based policy making and budgeting will only describe government action towards phenomena or steer the budget allocation and use of appropriations (Varis, 2020[18]). A phenomenon-based approach to policy making could also be used as a lead-in to mission-oriented innovation and policy approaches (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. From phenomenon-based policy making to missions

What are phenomena?

Societal problems, such as climate change, social inequality, urbanisation, future of work etc., that are complex and interdependent that need to be examined in a comprehensive and systemic manner.

How does phenomenon-based policy making challenge the public sector?

Current public administration structures do not correspond with 21st Century phenomena. Hence, a single administrative branch cannot deal with these issues. Furthermore, existing silos in government with their corresponding responsibilities and budget structures may actually impede a cross-administrative, comprehensive approach to phenomenon-based strategic policy making and implementation of reforms.

Could phenomenon-based policy making be linked to mission-oriented innovation?

The European Commission has been supporting a mission-driven approach to upcoming and evolving socio-technical challenges connected to the European Green Deal, Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan as well as the Sustainable Development Goals. While phenomenon-based policy making seeks to understand cross-cutting societal challenges, a mission-driven approach sets out to develop bold, inspirational and widely relevant missions for society that can be clearly framed, targeted and measured in concrete timeframes. Hence, a phenomenon-based understanding of systemic issues could be used as an antecedent approach to setting missions.

Source: OECD; (Sitra, 2018[15]; European Commission, n.d.[19])

With the afore-described ambitious agenda to upgrade public administration to 21st century challenges and lead the way in governance in the world, the Government of Finland turned to the European Commission to support the building of a model that would incorporate anticipation into the broader public governance system. Taking into account all of the developments described above, the OECD has undertaken an initial assessment of the system and how it deals with uncertainty and complexity.

References

[7] Anttila, J. et al. (2018), Pitkän aikavälin politiikalla läpi murroksen – tahtotiloja työn tulevaisuudesta, Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja 34/2018, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/160723/34-2018-Tulevaisuusselonteon%20taustaselvitys%20Pitkan%20aikavalin%20politiikalla%20lapi%20murroksen%20taitettu%20270318.pdf.

[2] Economist Intelligence Unit (2020), Democracy Index, https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/ (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[17] Eduskunta (2018), tulevaisuuspolitiikka – mitä se on, ja mikä on tulevaisuusvaliokunnan rooli?, Tulevaisuusvaliokunnan 25-vuotisjuhlakokous 16.11.2018 Eduskunnan tulevaisuusvaliokunnan julkaisu 9/2018, https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/naineduskuntatoimii/julkaisut/Documents/NETTI_TUVJ_9_2018_Tulevaisuuspolitiikka.pdf.

[1] European Commission (2020), Report on the long-term sustainability of public finances in Switzerland, Publications Office of the European Union, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/33470 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

[19] European Commission (n.d.), “EU Missions in Horizon Europe”, https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe_en (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[14] Government of Finland (2020), Strategy for Public Governance Renewal, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162573/Public_governance_strategy_2020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[20] Government of Finland (2019), Government Action Plan Inclusive and competent Finland – a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society, Publications of the Finnish Government 2019:29, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/161935/VN_2019_33.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[21] Government of Finland (2019), Research and foresight information will be used more effectively to underpin the Government’s strategic policy-making, Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government.

[22] Government of Finland (2019), Strategic ministerial group draws up a description of the current situation, a specified assignment, impact assessments and indicators, Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government.

[16] Hodgson, D. et al. (eds.) (2019), The Projectification of the Public Sector, Routledge, New York : Routledge, 2019. | Series: Routledge critical studies in public management, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315098586.

[13] Lähteenmäki-Smith, K. (2020), “Encouraging the state steering system to adopt greater systems-based thinking”, Perspectives into topical issues in society and ways to support political decision making, No. 20/2020, Policy brief.

[3] Lähteenmäki-Smith, K. et al. (2021), Government steering beyond 2020 From Regulatory and Resource Management to Systems navigation.

[4] Lawton, A. (ed.) (2010), “Trust, good governance and unethical actions in Finnish public administration”, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 23/7, pp. 647-668, https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011078905.

[10] Määttä, S. (2011), () ‘Mission Possible. Agility and Effectiveness in State Governance, Sitra Studies 57, https://www.sitra.fi/app/uploads/2011/08/Selvityksia57.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[6] OECD (2021), Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Finland, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/52600c9e-en.

[11] OECD (2017), Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges: Working with Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279865-en.

[9] OECD (2015), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Estonia and Finland: Fostering Strategic Capacity across Governments and Digital Services across Borders, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264229334-en.

[8] OECD (2010), Finland: Working Together to Sustain Success, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086081-en.

[12] Prime Minister’s Office (2011), “Management of Government Policies in the 2010s: Tools for More Effective Strategic Work”, http://vnk.fi/en/frontpage.

[15] Sitra (2018), Phenomenon-based public administration, Discussion paper on reforming the government’s operating practices, https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/phenomenonbased-public-administration/.

[5] Transparency International (2020), Corruption Perception Index 2020, https://www.transparency.org (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[18] Varis, T. (2020), Development of phenomenon-based budgeting requires a shared understanding and commitment from the public administration, https://www.vtv.fi/en/publications/development-of-phenomenon-based-budgeting-requires-a-shared-understanding-and-commitment-from-the-public-administration/.

Notes

← 1. The Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin's Government "Inclusive and competent Finland – a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society" was submitted to Parliament in the form of a Government statement on 10 December 2019. After the resignation of the Prime Minister Antti Rinne’s Government on 10 December 2019, the Prime Minister Marin’s Government has adopted the same programme 'Inclusive and competent Finland – a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society' as its Government Programme (Government of Finland, 2019[20]).

← 2. See further (Government of Finland, 2019[21])

← 3. See further (Government of Finland, 2019[22])

← 4. See further (Government of Finland, 2020[14])

← 6. Government of Finland has a tradition to support research in core governance areas through the research and assessment activities (VN TEAS). Previous studies have included deep-dives into experimentation, innovation and other issues. The recent Steering2020–project was undertaken below the same framework with the aim to provide an overall picture of the development and current state of governance, in its societal context, in Finland.